Enhanced High-Temperature Oxidation Resistance of Refractory High-Entropy Alloys Al-Cr-Mo-Ta-Ti by Aluminizing Using Pack Cementation

Received: 20 December 2025 Revised: 07 January 2026 Accepted: 21 January 2026 Published: 28 January 2026

© 2026 The authors. This is an open access article under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

1. Introduction

Refractory high-entropy alloys (RHEAs) are considered promising structural materials for high-temperature applications due to their high solidus temperature and high mechanical strength. In order to overcome their shortcomings of high density, insufficient oxidation resistance, and low room temperature ductility, elements like Al, Cr, Ti, and others are added in alloy development [1,2]. Among the vast number of RHEA systems, equimolar AlCrMoTaTi and its non-equimolar derivatives showed high oxidation resistance in the range of Ni-based superalloys at temperatures exceeding 1000 °C. The cause of this is the formation of multi-layered oxide scales of titania (TiO2), alumina (Al2O3), chromia (Cr2O3), and chromium tantalate (CrTaO4). Despite this, internal corrosion due to the formation of titanium nitride (TiN) can be observed [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11]. Alloying RHEAs with elements that form protective oxide scales is typically accompanied by the formation of intermetallic phases in bulk RHEAs, which can have detrimental effects on their low-temperature ductility. Hence, surface coatings are an alternative to provide elemental reservoirs of oxide formers near the component surface while not affecting bulk properties in any negative manner.

Diffusion coatings are well-established for high-temperature structural materials such as Ni-based superalloys. Chemical vapor deposition (CVD) of oxide forming elements, such as Al, Cr, and/or Si, on component surfaces forms diffusion coatings. At elevated coating temperatures, interdiffusion between deposited elements and the substrate material is facilitated. The process of pack cementation utilizes powder mixtures for in situ CVD coating of components with complex shapes. Typically, elemental powders are used as solid diffusion sources, metal salts as process activators, and alumina works as an inert filler powder [12]. Components to be coated are embedded in the powder mixture, sealed in gas-tight batch containers, and heat-treated at temperatures in the range of 800–1000 °C for thermal activation of diffusion processes both in gas phase for deposition as well as in solid state for coating formation.

Aluminizing by pack cementation showed improved oxidation resistance of pure refractory metals in studies by Ulrich et al. [13] at high temperatures of 1300 °C. Furthermore, Beck et al. [14] successfully suppressed the pesting effect at moderate temperatures of 700–900 °C, which uncoated refractory metals are prone to. Inhibition of the pesting effect by aluminizing was also proven for the RHEA Hf0.5Nb0.5Ta0.5Ti1.5Zr by Sheikh et al. [15]. Additionally, their work showed a reduction of O-induced embrittlement of Al0.5Cr0.25Nb0.5Ta0.5Ti1.5 under oxidation conditions at 800 °C. For higher temperatures of around 1000 °C, several studies found facilitated formation of protective alumina scales and enhanced oxidation resistance by aluminizing via pack cementation for the RHEAs Al0.5Cr0.25Nb0.5Ta0.5Ti1.5 [16], CrMoNbTaW [17], and HfNbTaTiZr [18] as well as for the refractory medium-entropy alloys (RMEAs) NbTaVW [19] and Mo0.3Nb1.3TiZr [20]. Some of the authors applied two-step pack cementation processes.

In our previous work [21], two new non-equimolar RHEAs in the system Al-Cr-Mo-Ta-Ti with promising combinations of density (6.7–8.6 g/cm3), solidus temperature (1499–1886 °C), and oxidation resistance (1.0–1.6 mg/cm2 after 48 h at 1000 °C in air) were introduced. Al-rich Al3CrMoTaTi facilitated the formation of protective alumina scale at 1000 °C, whereas Ti-rich AlCrMoTaTi3 was prone to internal corrosion by TiN formation. In this study, diffusion coatings are developed by aluminizing using pack cementation. The three RHEAs AlCrMoTaTi, Al3CrMoTaTi, and AlCrMoTaTi3 were chosen for their promising high-temperature properties and different concentrations of Al, affecting the aluminizing process. The resulting coatings are investigated in terms of thickness, microstructure, and phase formation. Their effectiveness in improving oxidation resistance is analysed by isothermal oxidation testing at 1000 °C in air and compared with the uncoated condition. Here, the formation of oxide scales and internal corrosion by TiN formation are under investigation.

2. Materials and Methods

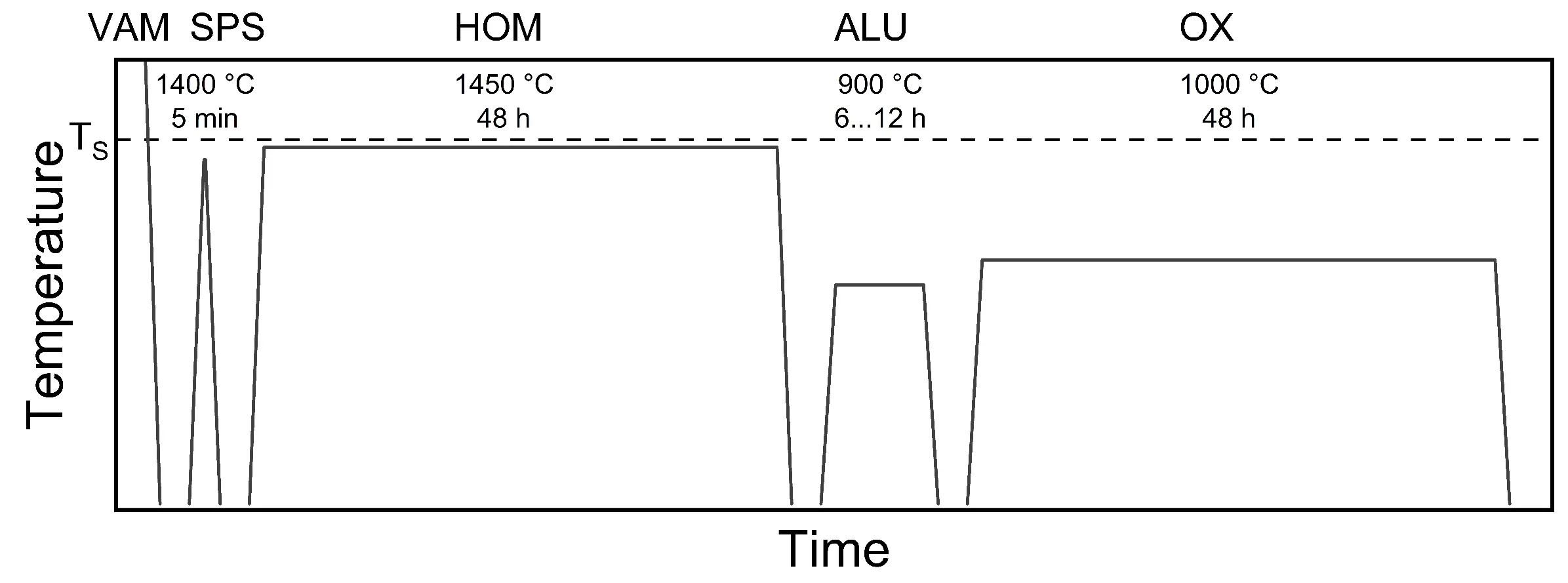

For the synthesis of bulk RHEA specimens, a combined melting metallurgical and powder metallurgical approach was chosen. Figure 1 provides an overview of the temperature-time regimes for all processing steps, as described in detail in the following sections.

Figure 1. Schematic temperature-time regime of the synthesis and processing route: solidus temperature (TS), vacuum arc melting (VAM), field-assisted sintering technology/spark plasma sintering (FAST/SPS), homogenization heat treatment (HOM), aluminizing (ALU), and oxidation testing (OX).

2.1. Synthesis and Processing Route

RHEAs were vacuum arc-melted (VAM) from high-purity bulk metals Al (99.99%), Cr (99.995%), Mo (99.9%), Ta (99.9%), and Ti (99.995%, by weight and metals basis respectively) in a water-cooled Cu mold under 0.6 bar Ar atmosphere. Utilizing Ti as a getter material before initial melting ensured minimal residual oxygen. Melt buttons of 30–55 g were flipped and re-melted five times to ensure macroscopic chemical homogeneity. Nominal compositions of the three RHEAs under investigation are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Nominal compositions of the three RHEAs investigated in at.% and wt.%, respectively.

|

RHEA |

Abbr. |

Al |

Cr |

Mo |

Ta |

Ti |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

AlCrMoTaTi |

C0 |

20.0/6.7 |

20.0/12.9 |

20.0/23.7 |

20.0/44.8 |

20.0/11.9 |

|

Al3CrMoTaTi |

C-Al3 |

42.8/17.7 |

14.3/11.3 |

14.3/21.0 |

14.3/39.5 |

14.3/10.5 |

|

AlCrMoTaTi3 |

C-Ti3 |

14.3/5.4 |

14.3/10.4 |

14.3/19.2 |

14.3/36.2 |

42.8/28.8 |

Produced melt buttons were crushed and milled to powder, utilizing brittle mechanical behavior in the as-cast condition. Milling was performed in a vibrating disc mill for 20 s in ambient air. RHEA powders were consolidated to discs of 20 mm diameter and 2.2 mm height via field-assisted sintering technology/spark plasma sintering (FAST/SPS). Graphite tools allowed for 50 MPa and 1400 °C for 5 min under 5 × 10−2 mbar vacuum. Heating rates of 100 K/min were applied from room temperature to 1300 °C and 10 K/min from 1300 °C to 1400 °C, respectively. Sandblasting and grinding with diamond abrasive discs removed residual graphite foils after FAST/SPS. Subsequently, a homogenization heat treatment at 1450 °C for 48 h in Ar atmosphere with a heating rate of 10 K/min was conducted. Elemental analyses by He carrier hot gas extraction and infrared absorption exhibited low concentrations of non-metallic contaminants: O < 600 ppm, N < 80 ppm, and C < 150 ppm by mass, respectively. The homogenized disc specimens were cut into quarters and ground with alumina abrasive paper to an identical surface finish of grit 1000. More detailed information on the processing route can be found in our previous work [22].

2.2. Aluminizing by Pack Cementation

The pack cementation process was used for aluminizing to form Al-rich diffusion coatings on bulk RHEA substrates. To remove possible contaminations from the surfaces of as-prepared RHEAs, the specimens were ultrasonically cleaned in isopropanol at 40 °C for 15 min prior to pack cementation. A powder mixture of 10 wt.% pure Al powder as a diffusion source, 2 wt.% AlCl3 activator, and 88 wt.% inert Al2O3 filler embedded the specimens to be coated in covered alumina crucibles. For high reproducibility of the coating process, an identical ratio of specimen surface to powder mixture volume was applied by coating the same number of specimens in each coating batch, respectively. After sealing the alumina crucibles with high-temperature refractory clay, they were heat-treated in a tube furnace with Ar flow. Prior to aluminizing experiments, the tube furnace’s hot zone was carefully determined by a thermocouple type K and an electronic thermometer. Aluminizing was performed at 900 °C for 6, 7, 9, or 12 h with a heating rate of 5 K/min, respectively. This optimization aimed at finding aluminizing durations for coating thicknesses of around 50–80 µm. The dynamic equilibrium of chemical reactions during aluminizing of specimen surfaces can be summarized as follows:

|

```latex2\mathrm{ }\mathrm{A}\mathrm{l}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{l}}_{3\left(\mathrm{g}\right)}⇄2\mathrm{ }{\mathrm{A}\mathrm{l}}_{\left(l\right)}+3\mathrm{ }{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{l}}_{2\left(\mathrm{g}\right)}``` |

(1) |

Al released from decomposed AlCl3 adsorbs to the specimen surface, and solid-state interdiffusion of deposited Al and all substrate elements (Al, Cr, Mo, Ta and Ti) occurs at the aluminizing temperature of 900 °C. After the respective aluminizing duration, the tube furnace was turned off and cooled down to room temperature. Subsequently, the coated specimens were removed from the sealed alumina crucibles and ultrasonically cleaned identically to the first cleaning step before pack cementation. No subsequent diffusion heat treatment was applied.

2.3. Oxidation Testing

The specimens of all three RHEAs for oxidation testing were aluminized at 900 °C for 6 h. Before oxidation testing, the specimens in the uncoated and coated conditions were ultrasonically cleaned as described in the previous section. Oxidation testing was performed in quartz crucibles in an open tube furnace in ambient air. The hot zone of the tube furnace was carefully measured prior to oxidation experiments, using a thermocouple type K and an electronic thermometer. The furnace was heated with 5 K/min to 1000 °C and held isothermally for 48 h. Subsequently, the tube furnace was turned off and cooled down to room temperature, and the specimens were withdrawn from the oxidation test rig.

2.4. Characterization and Analyses

Weighing by scale with readability of 0.01 mg allowed for ex situ gravimetry of both the aluminizing process and oxidation testing, i.e., quantifying the weight gain by Al uptake and O/N uptake. The specimens for the aluminizing process and for oxidation testing were weighed and geometrically measured beforehand, and then weighed after each experiment, respectively. This method does not quantify possible evaporation of volatile refractory oxides, e.g., MoO3, during the early stage of oxidation before establishing quasi-stationary oxidation conditions. In the RHEA system Al-Cr-Mo-Ta-Ti, results of Schellert et al. [7] proved neglectable evaporation of MoO3 for the equimolar composition.

Metallographic cross sections of specimens were prepared using diamond grinding discs down to grit 1200, subsequent polishing with diamond suspension down to 3 µm particle size, and final chemical polishing with 0.25 µm alkaline colloidal silica suspension.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was performed using a field emission gun, back-scattered electron detector (SEM-BSE), and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS).

Surfaces of bulk samples in different conditions were analyzed by X-ray diffraction analysis (XRD) using Cu-Kα radiation. Diffraction angles 2θ of 15–115° with 0.02° angular resolution and PDF-4+ database (version 4.2302) were utilized.

Experimental investigations were supplemented by CALPHAD simulations using Thermo-Calc software (version 2025b) with TCHEA5 database for high-entropy alloys.

3. Results

3.1. Aluminizing by Pack Cementation

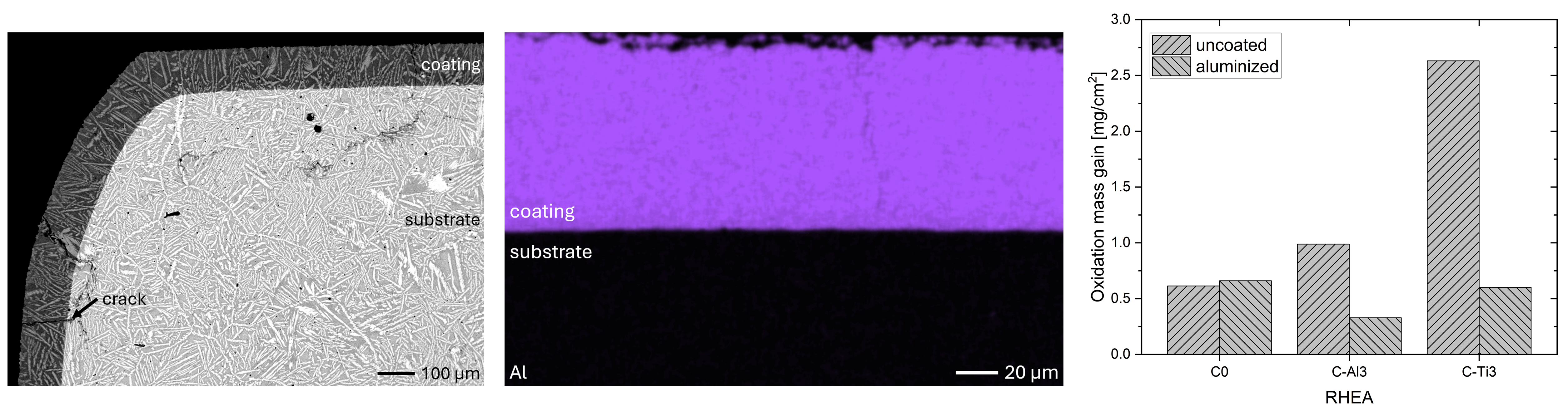

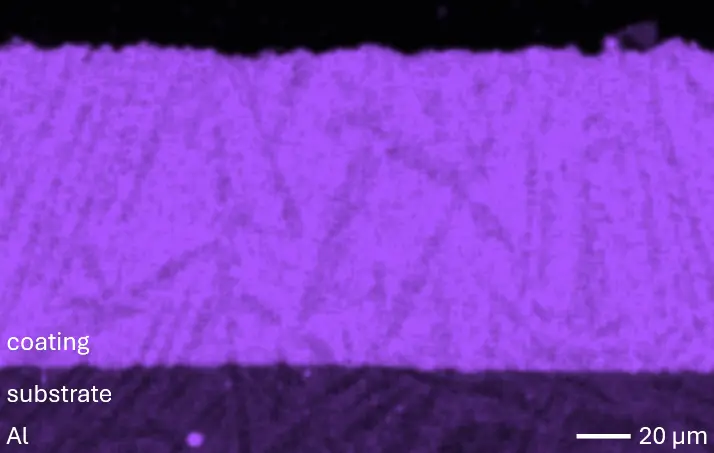

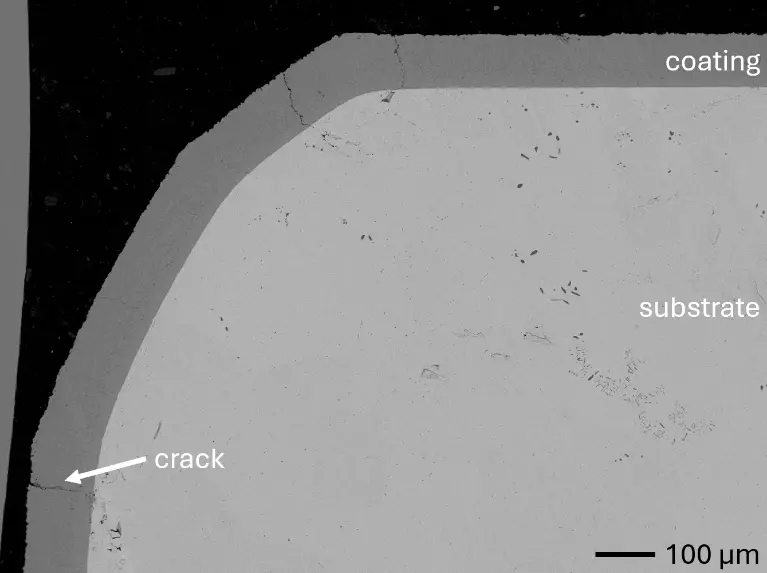

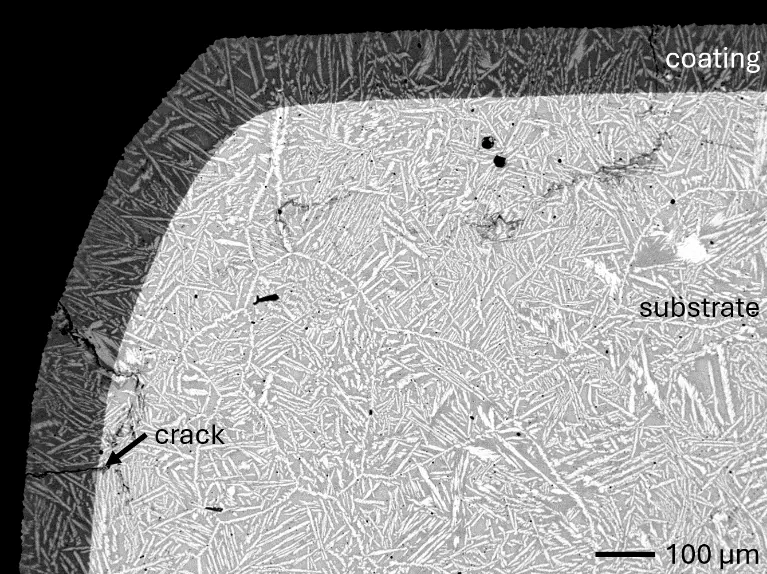

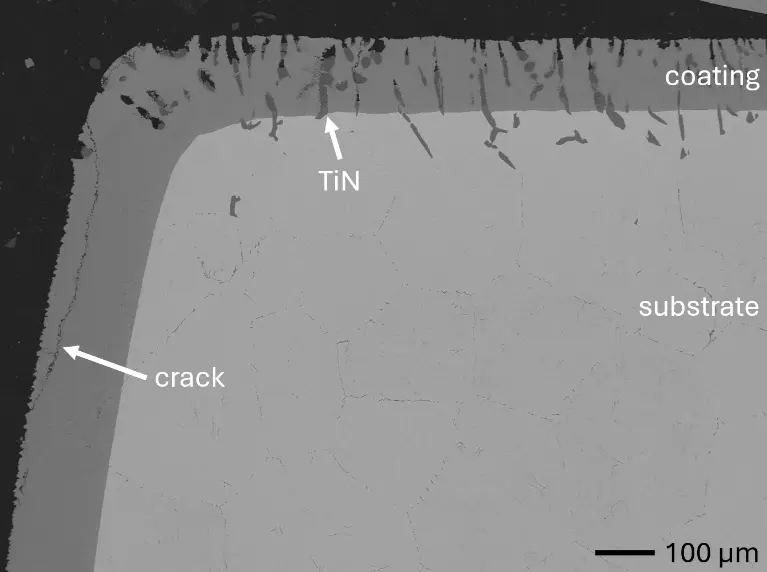

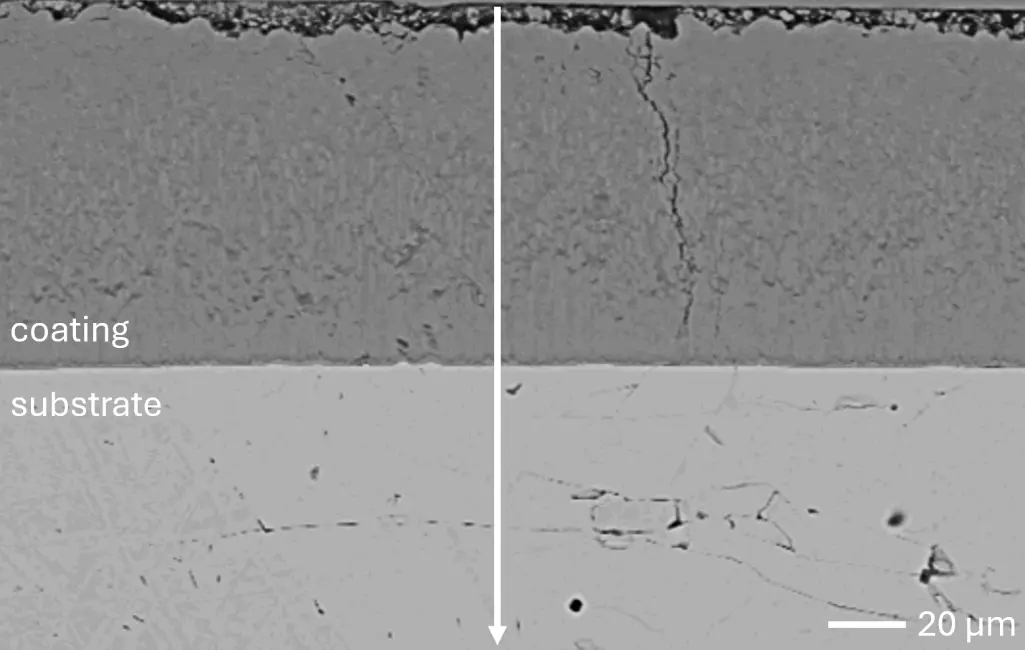

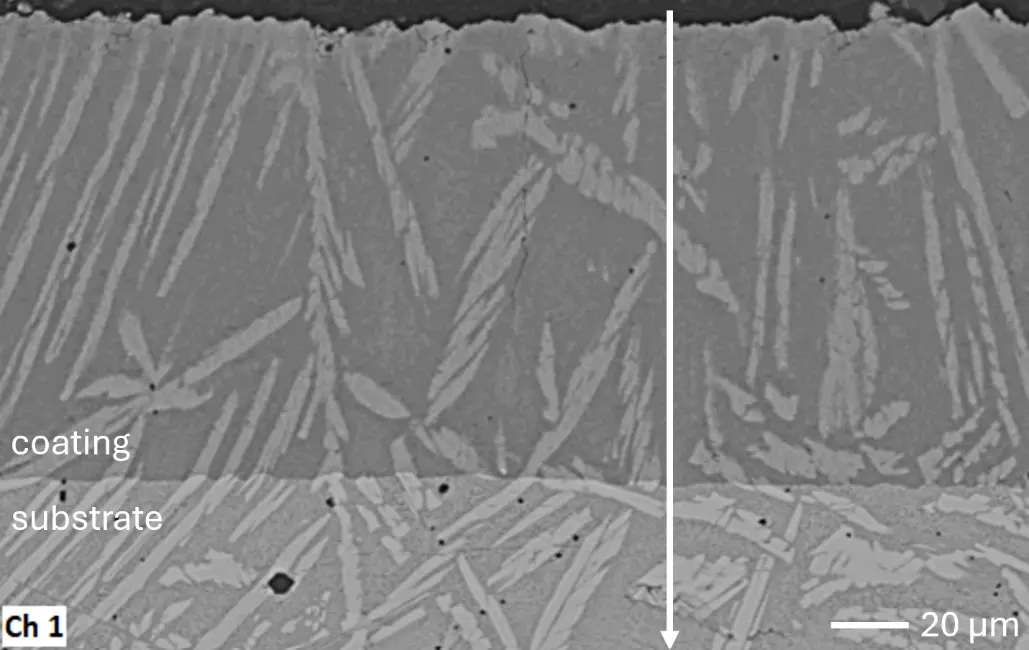

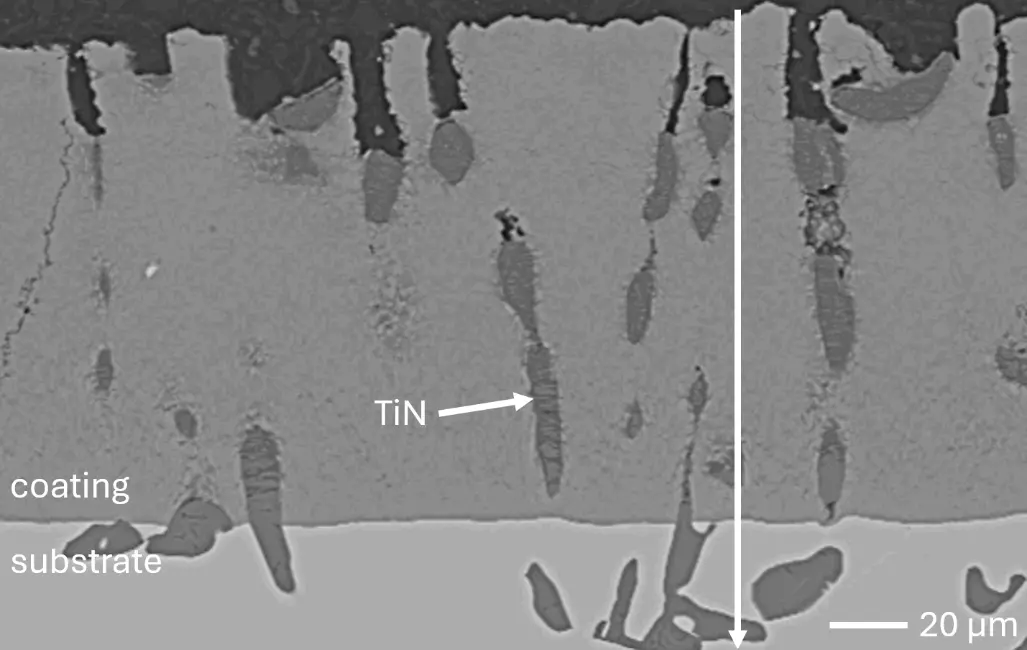

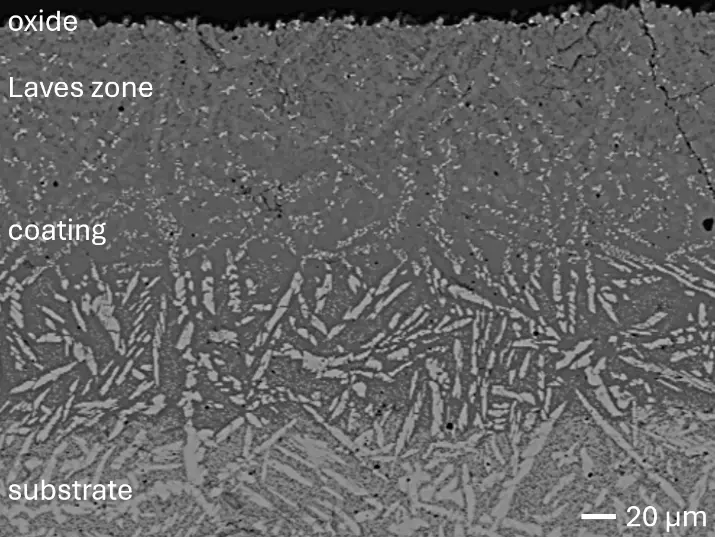

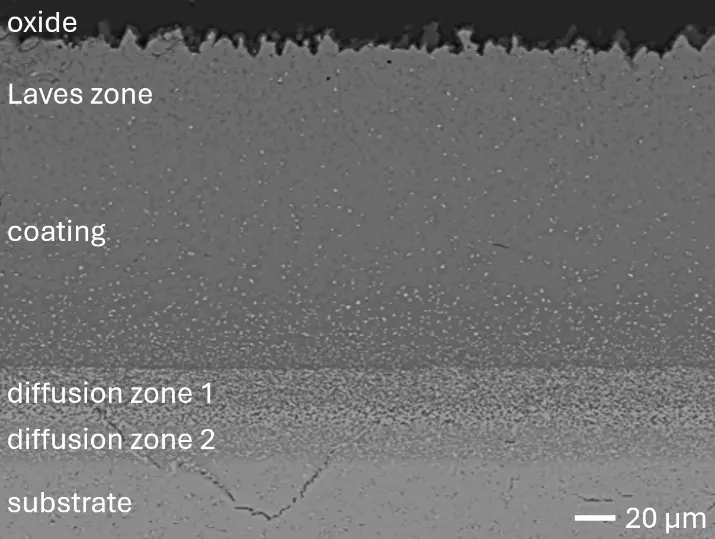

In this work, aluminizing diffusion coatings by pack cementation for enhanced oxidation resistance are developed with thicknesses in the range of approximately 50–80 µm. On one hand, this provides sufficient Al reservoir for forming protective alumina scales at the coating surface. On the other hand, it minimizes thermal stresses between the substrate and diffusion coating during thermal cycling in high-temperature applications. For this reason, aluminizing durations were varied between 6, 7, 9, and 12 h, and the resulting coating thicknesses were analyzed, respectively. Figure 2 compares overview cross sections of coatings on the different RHEA substrates after 7 h of aluminizing at 900 °C. All RHEAs formed compact diffusion coatings of around 100 µm thickness. Coatings showed good adhesion and formed conformally to non-planar substrate surfaces with only a few cracks perpendicular to the surface, most likely caused by metallographic preparation. Each coating is characterized by an apparent single-layered structure and a planar diffusion front. No delamination and no pores were detectable in the coatings or near coating/substrate interfaces of all specimens under investigation. The dark grey elongated structures on the top surface of C-Ti3 are TiN from the homogenization heat treatment, which were not completely removed by grinding prior to the aluminizing process.

|

|

|

| (a) | (b) | (c) |

Figure 2. Overview SEM-BSE cross sections of RHEAs in the aluminized condition after 7 h at 900 °C: (a) C0; (b) C-Al3 with eutectoid-like bulk microstructure; (c) C-Ti3.

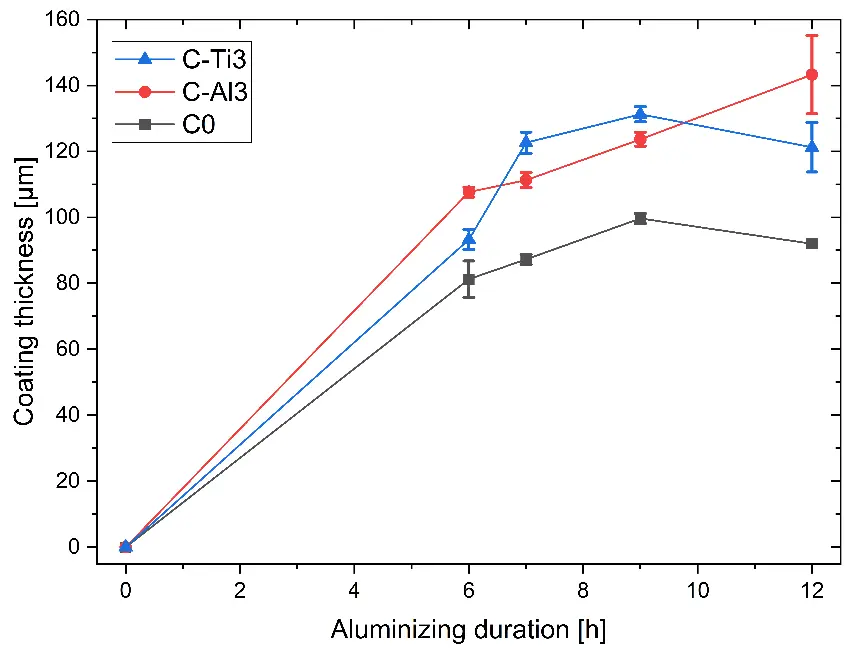

Findings on the effect of aluminizing duration on coating thickness are summarized in Figure 3. For all RHEAs, the coating thickness increases with increasing duration up to 9 h, followed by a plateau. Since the pack cementation process is diffusion driven, the diffusion length of Al from the coating surface through the formed coating to the coating/substrate interface increases over time. It is worth mentioning that even after the shortest aluminizing duration investigated of 6 h, coating thicknesses of C-Al3 and C-Ti3 are higher than the targeted range of approximately 50–80 µm, only C0 is in this thickness range. Hence, aluminizing durations for all three RHEAs can be further decreased for optimized coating thicknesses.

Figure 3. Effect of aluminizing duration on coating thickness for pack cementation at 900 °C (lines interconnecting data points are visual guidelines only).

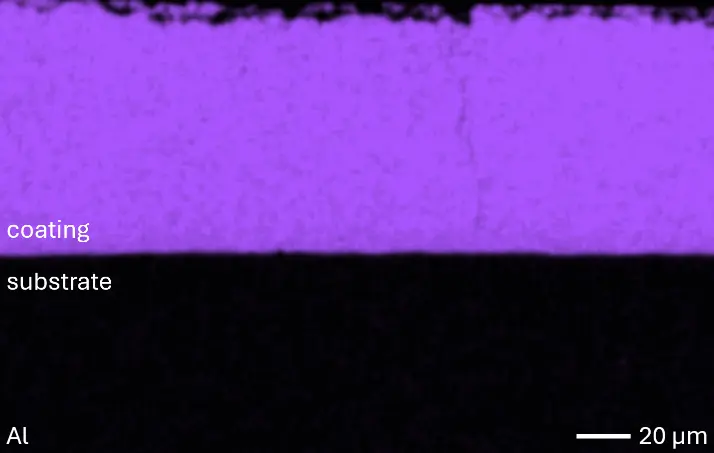

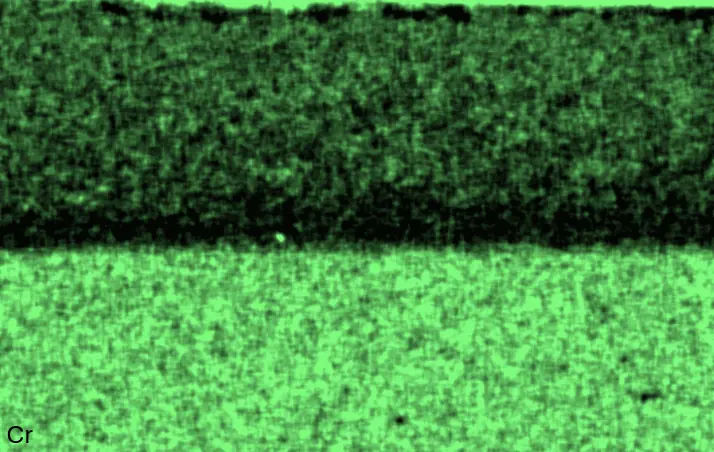

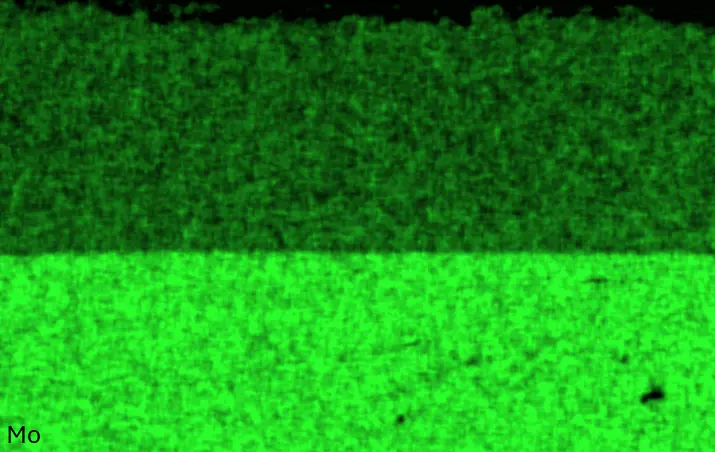

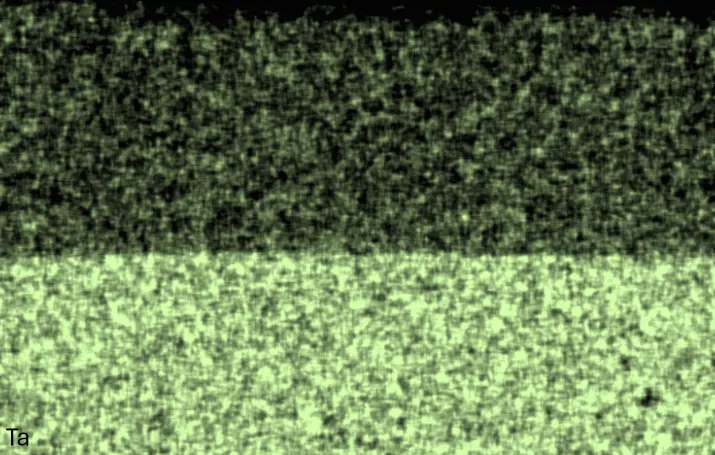

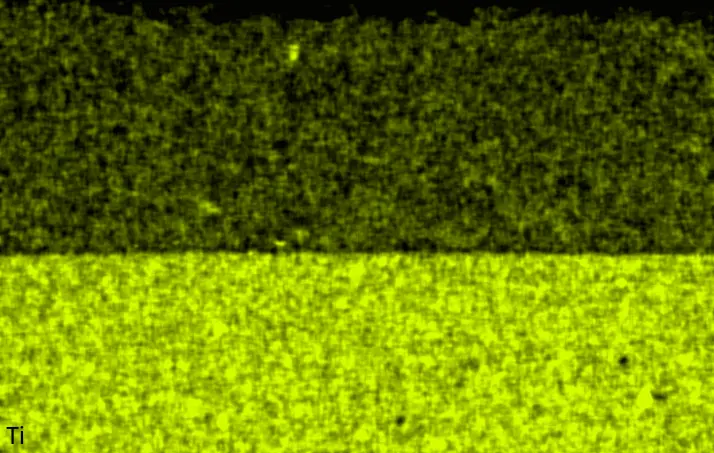

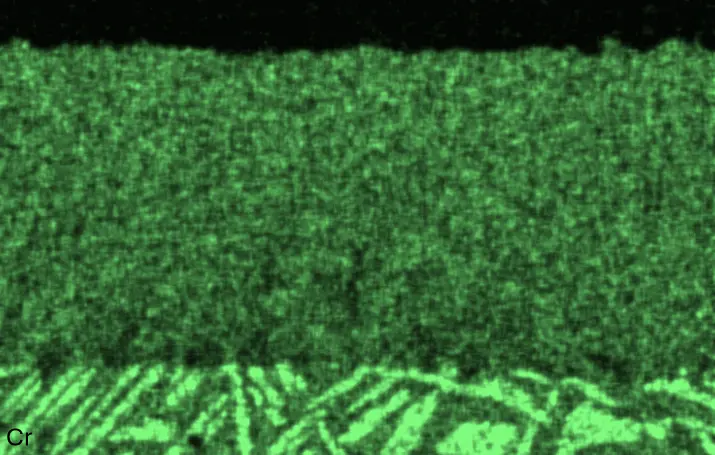

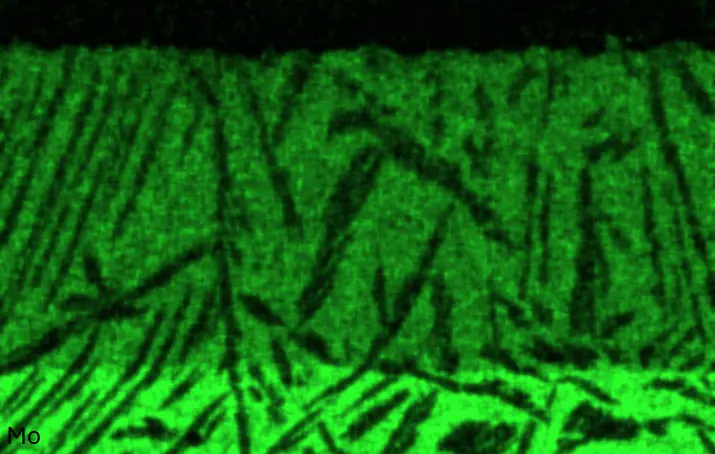

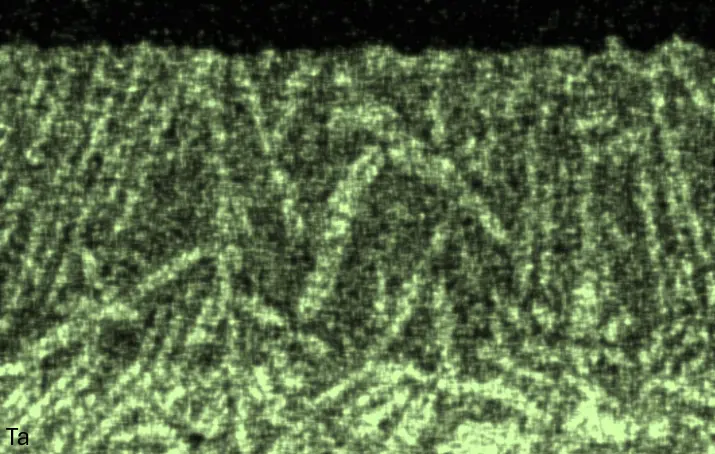

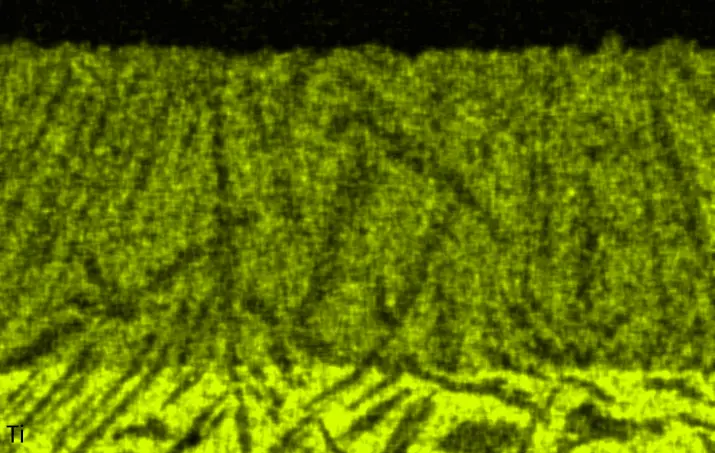

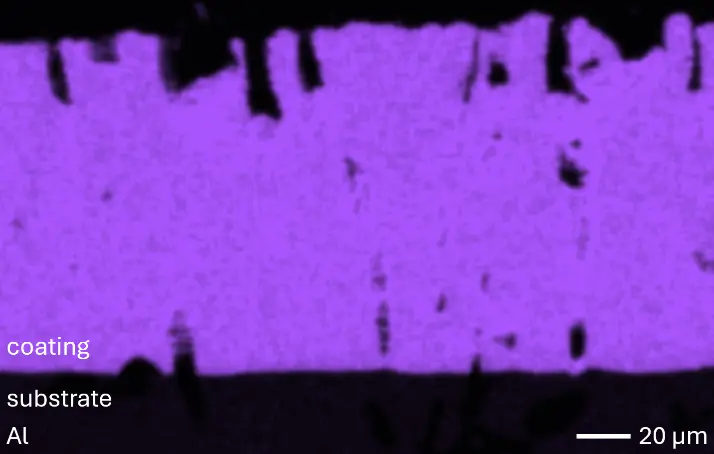

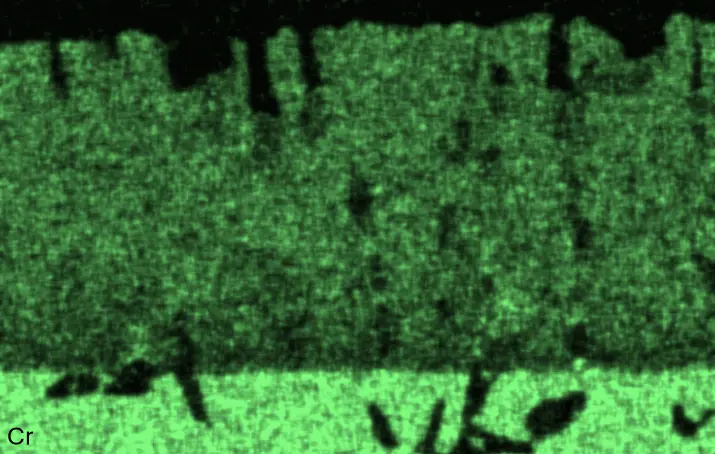

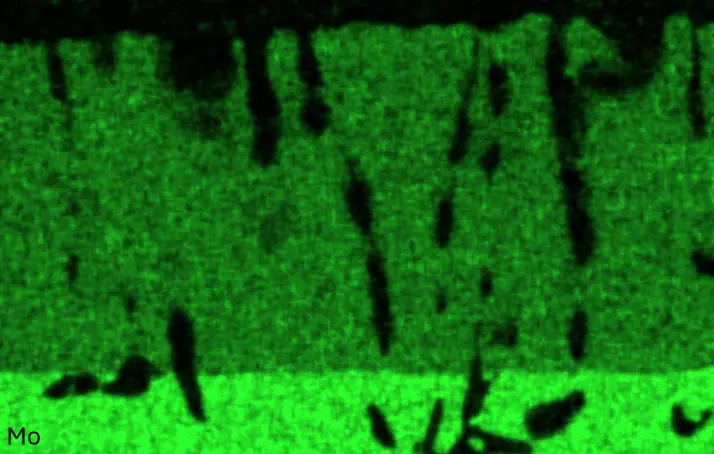

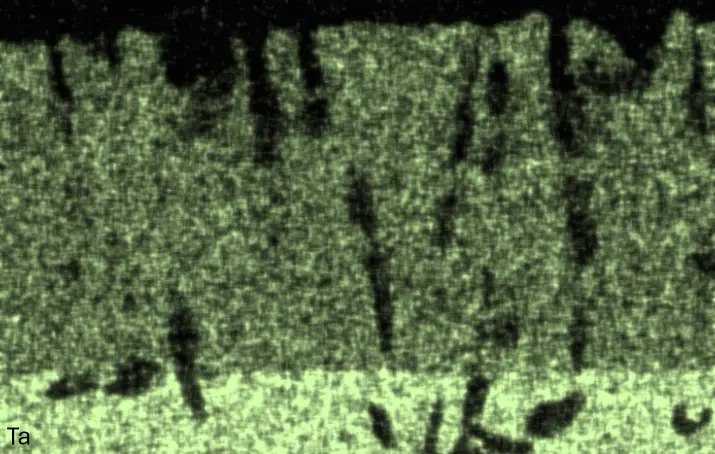

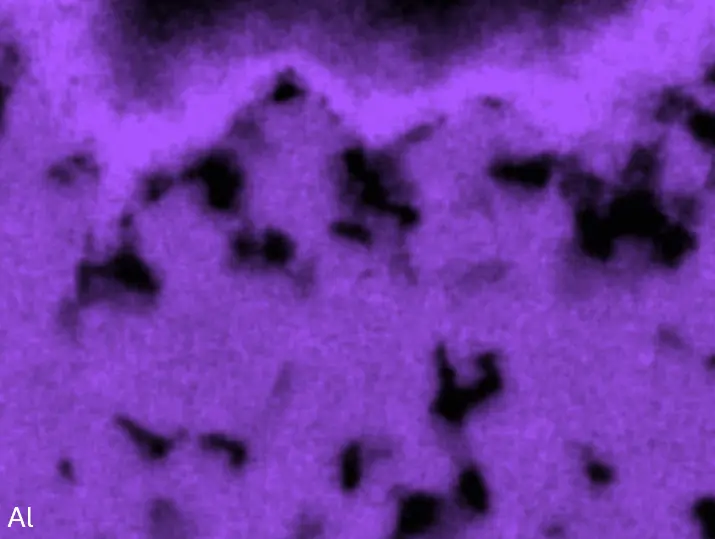

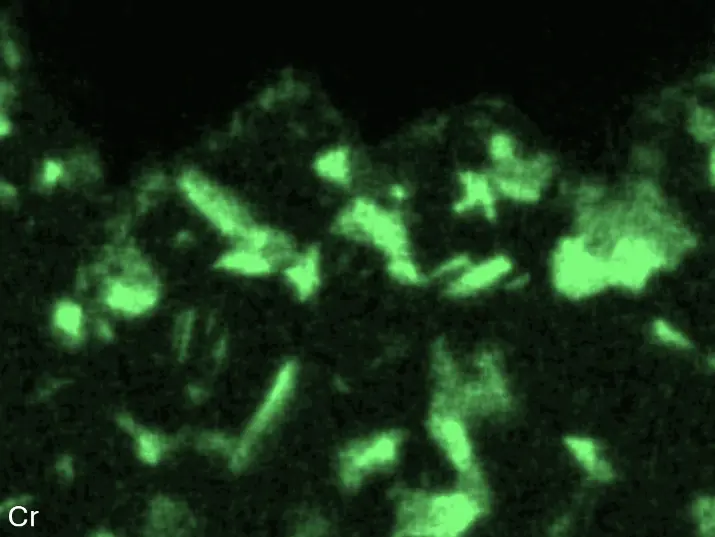

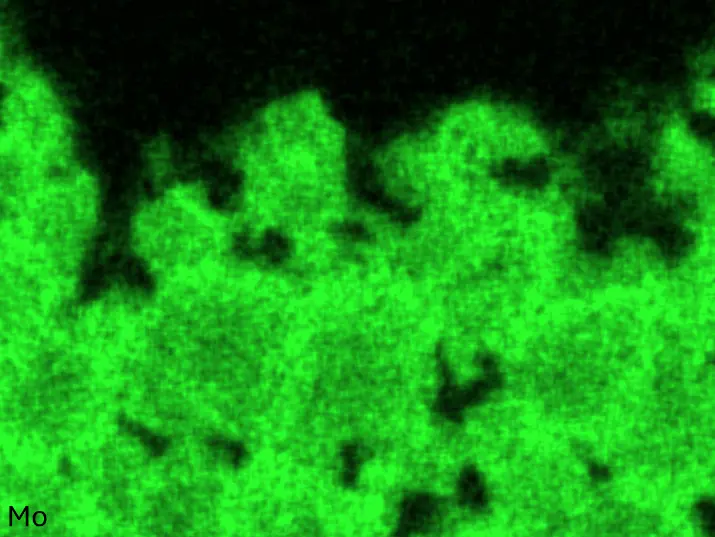

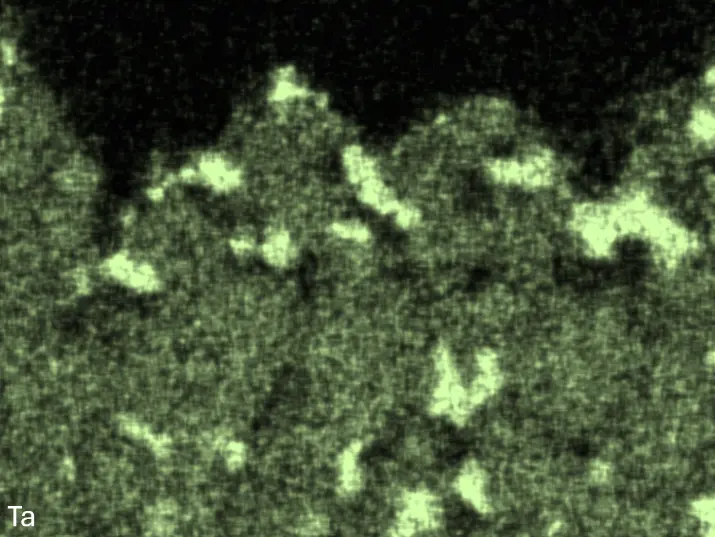

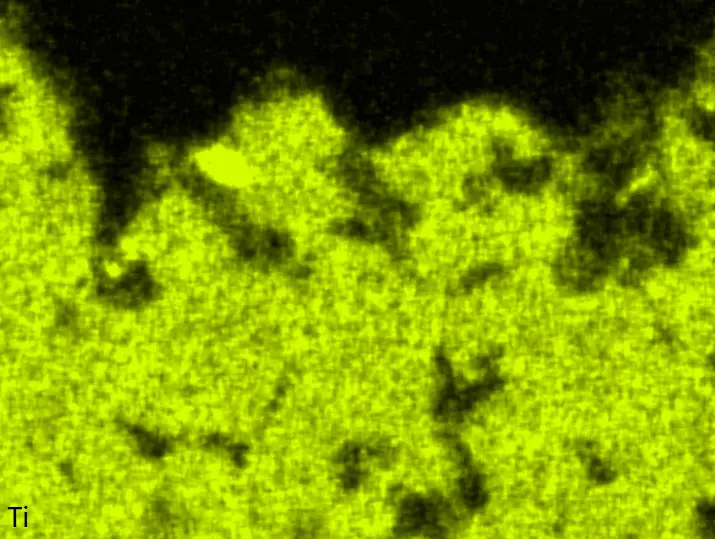

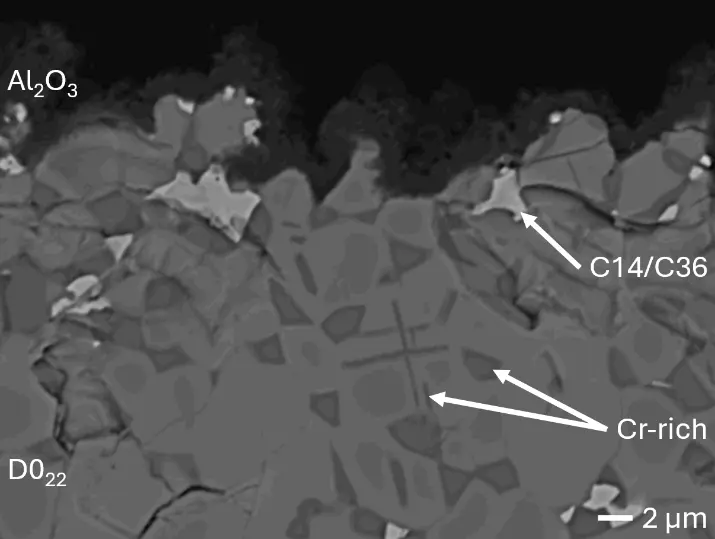

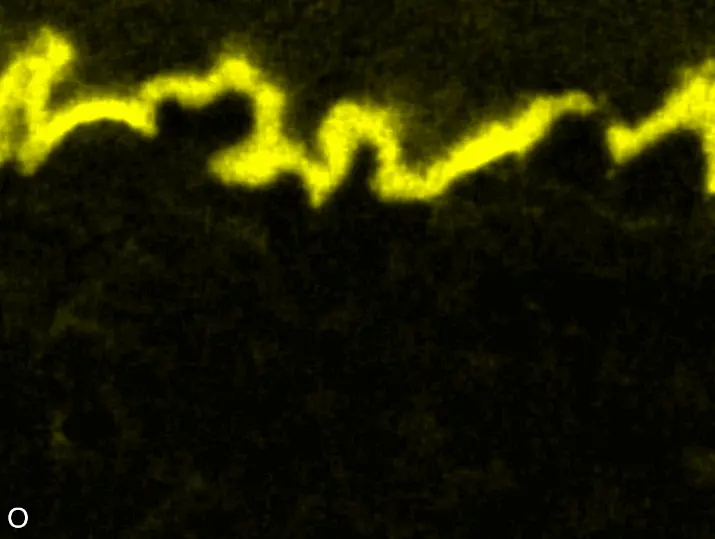

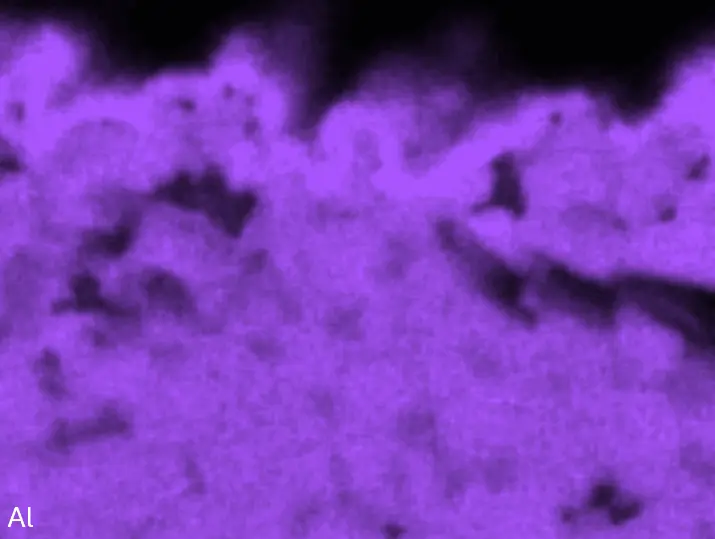

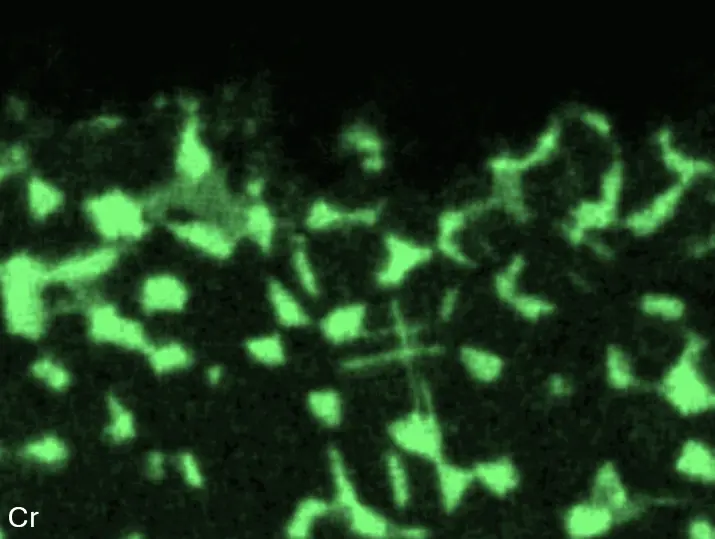

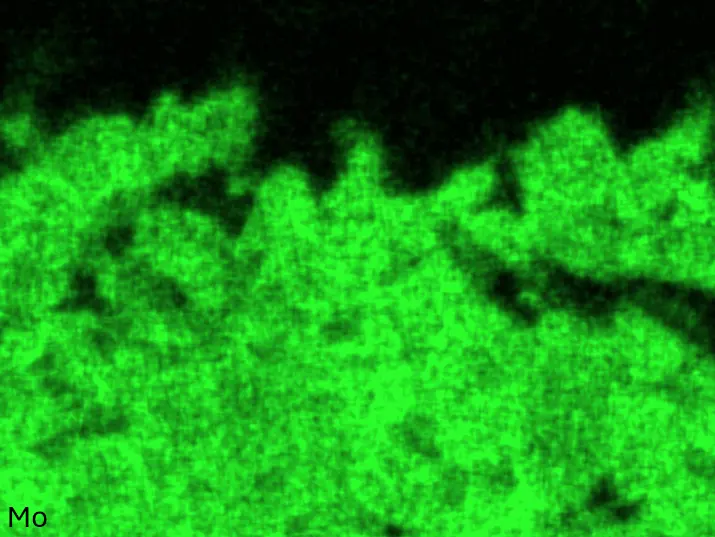

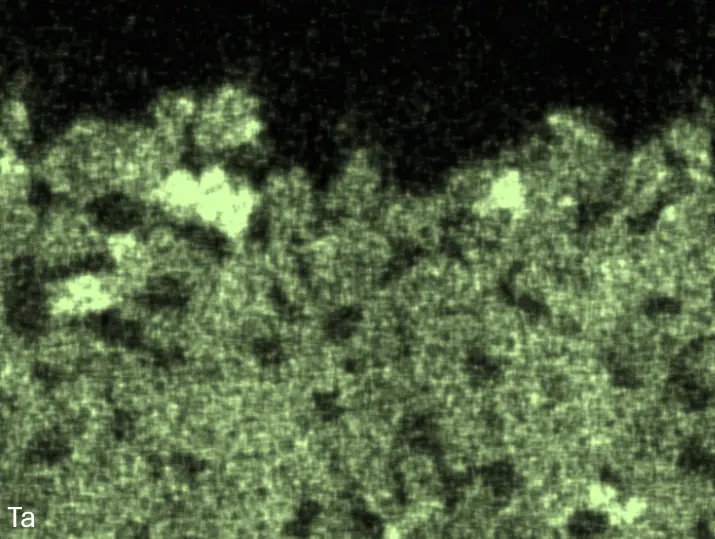

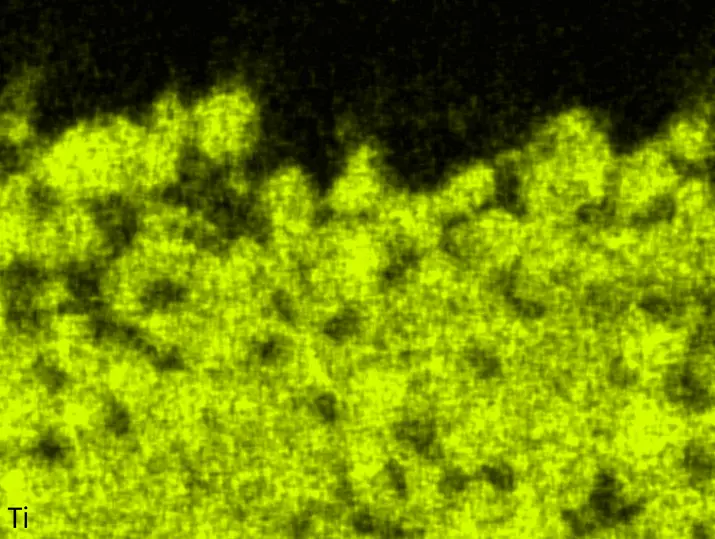

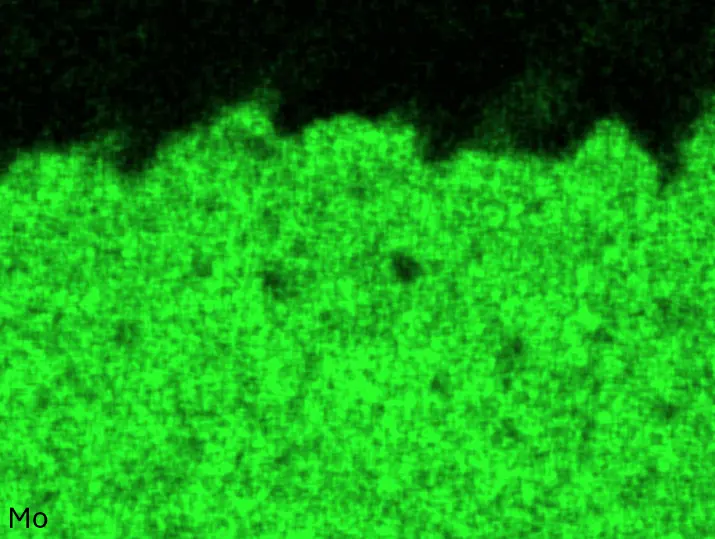

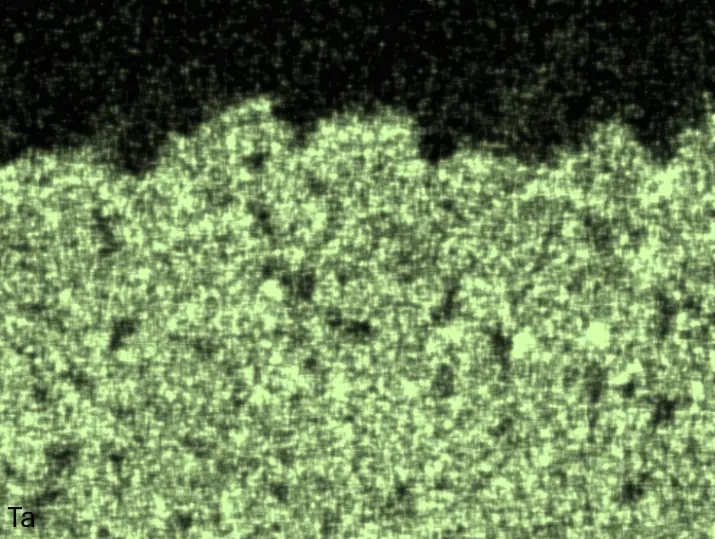

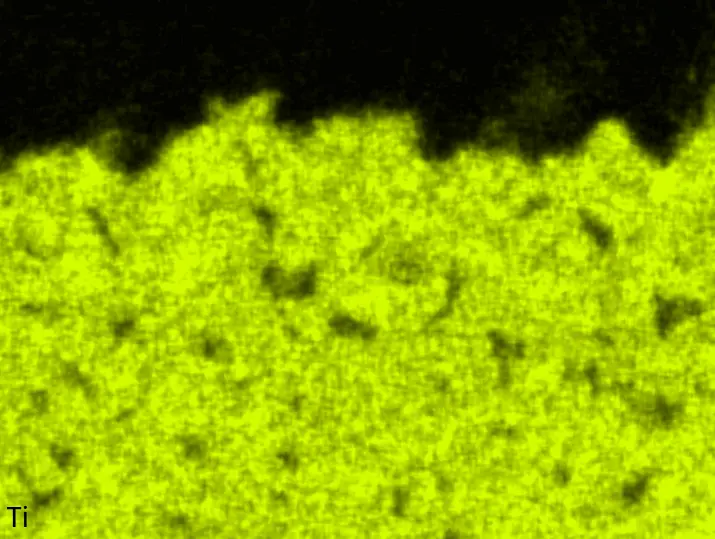

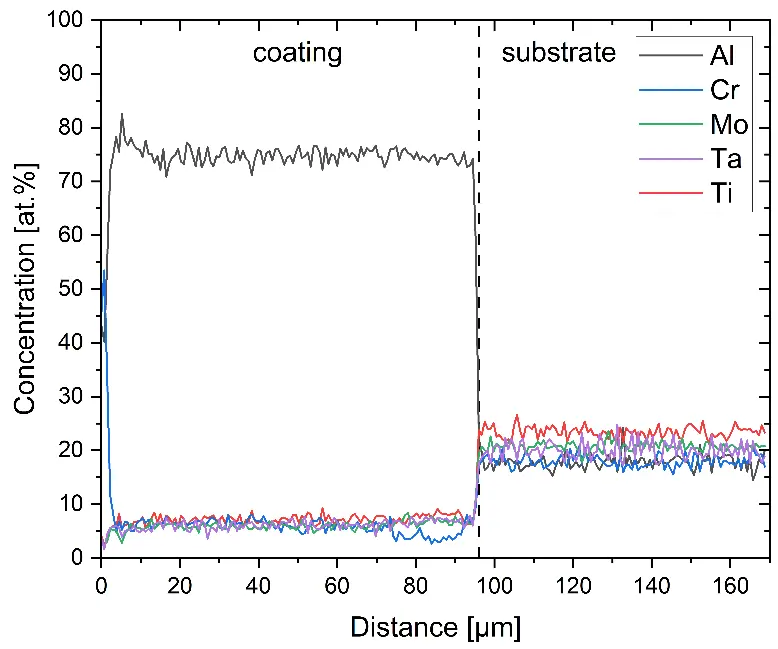

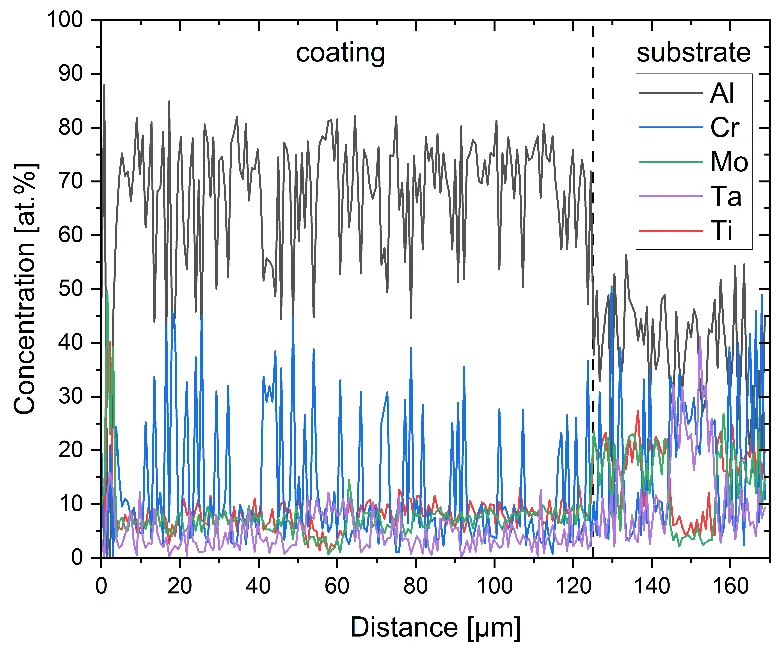

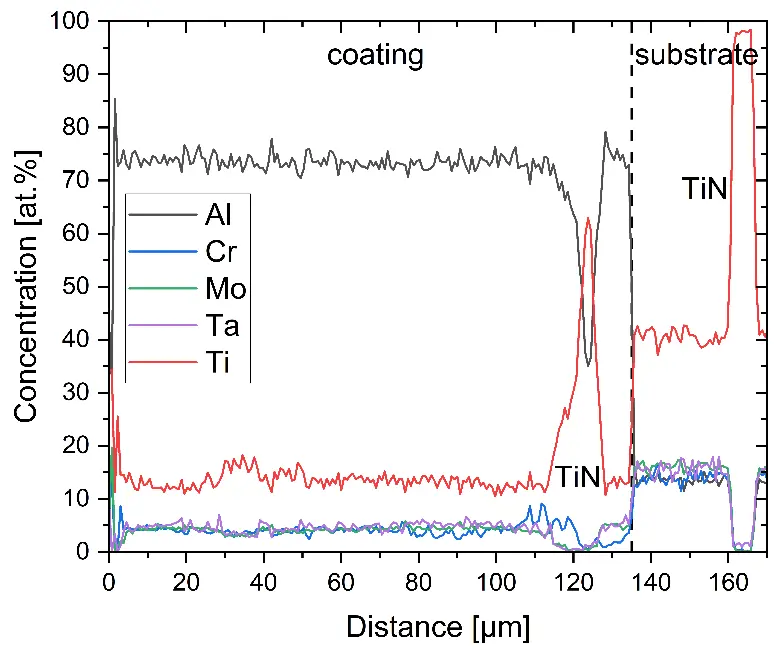

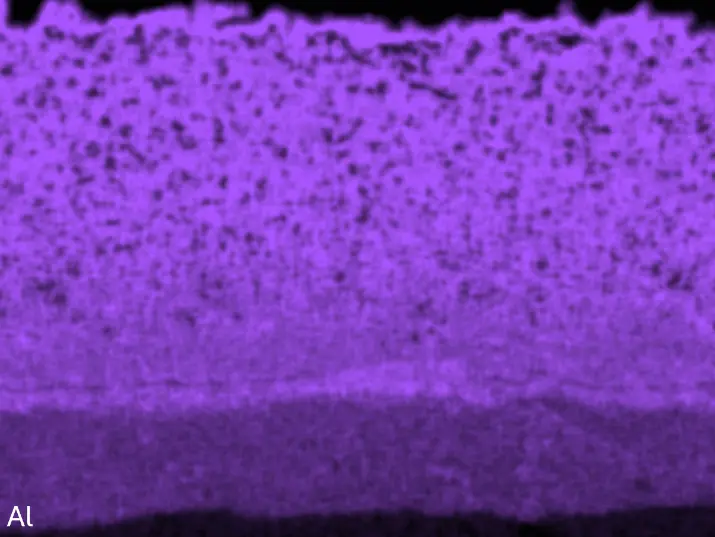

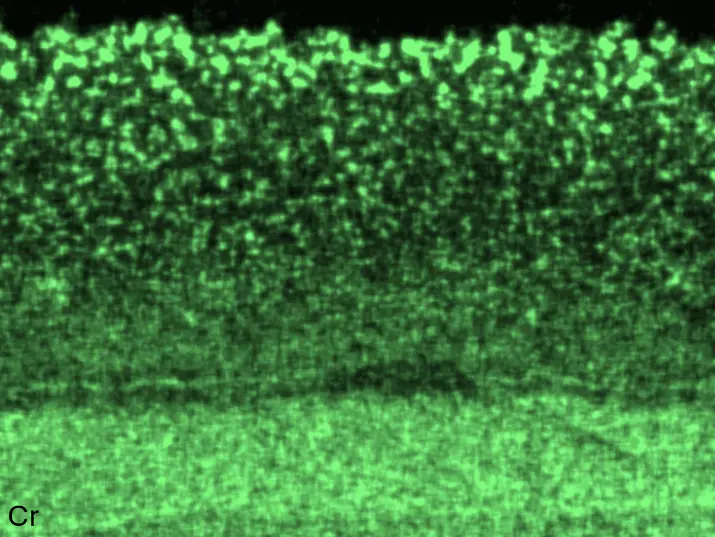

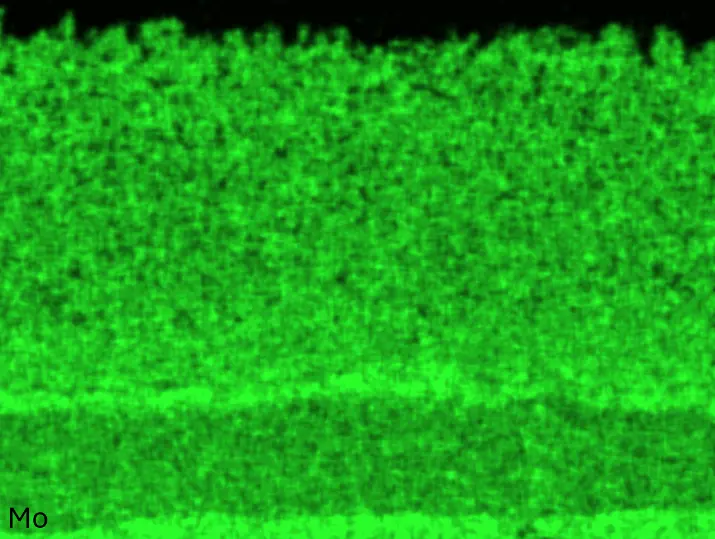

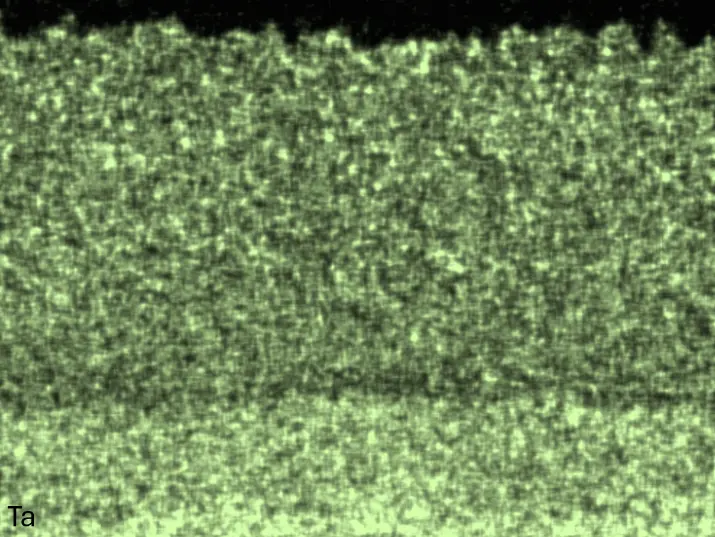

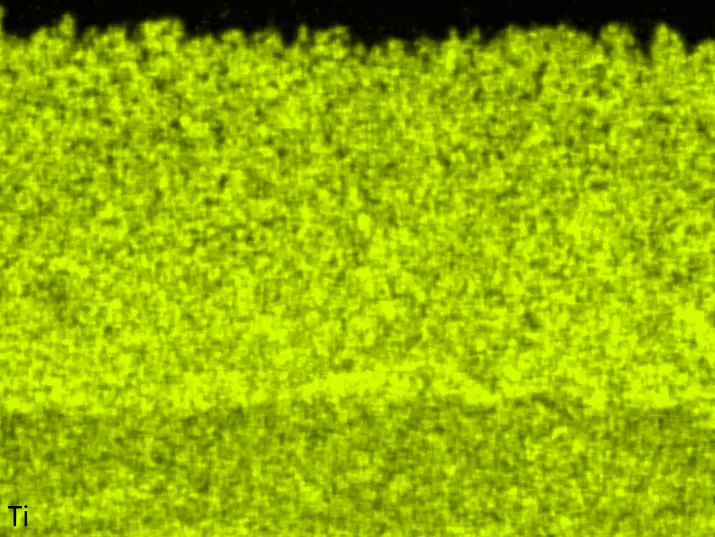

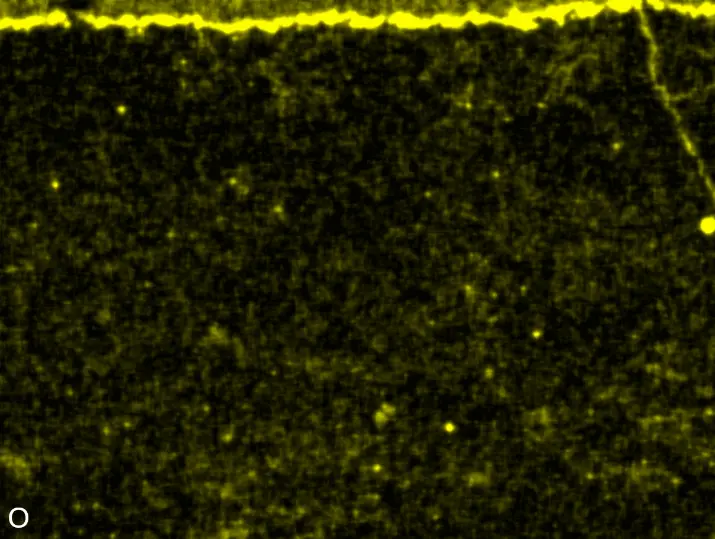

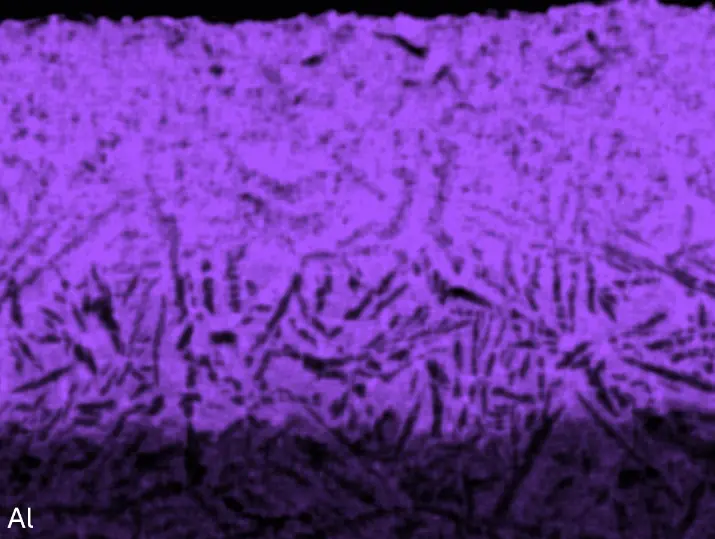

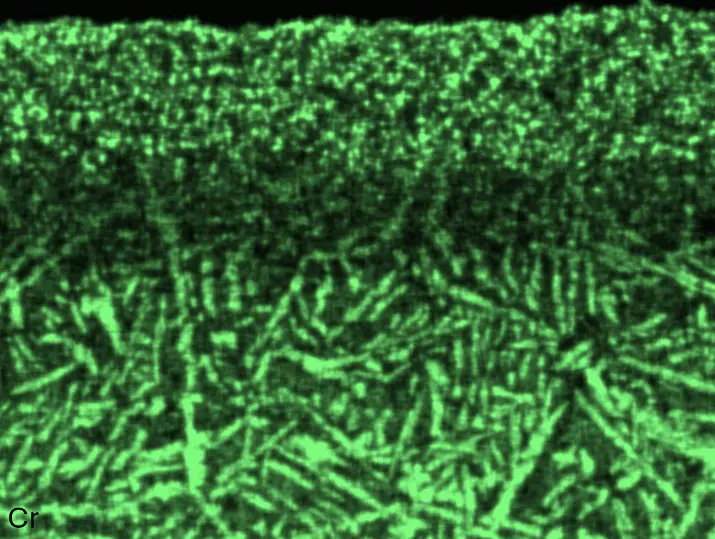

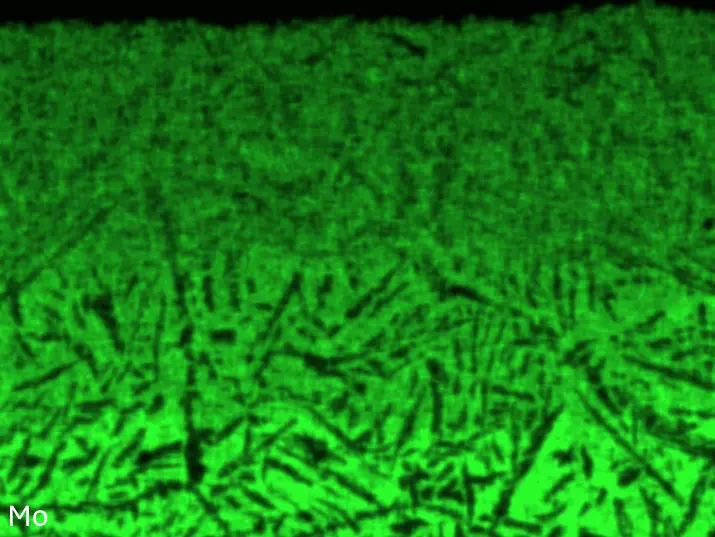

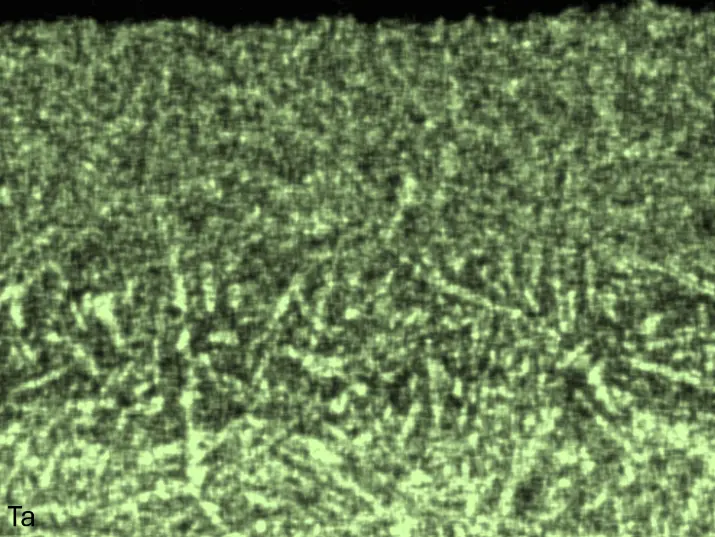

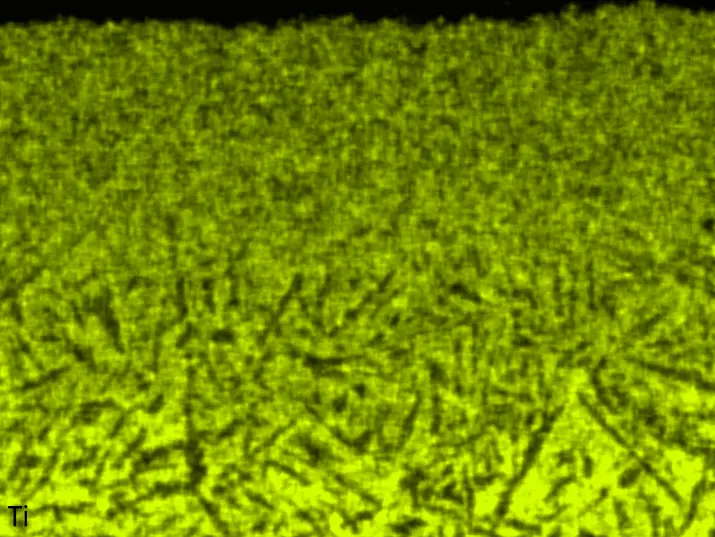

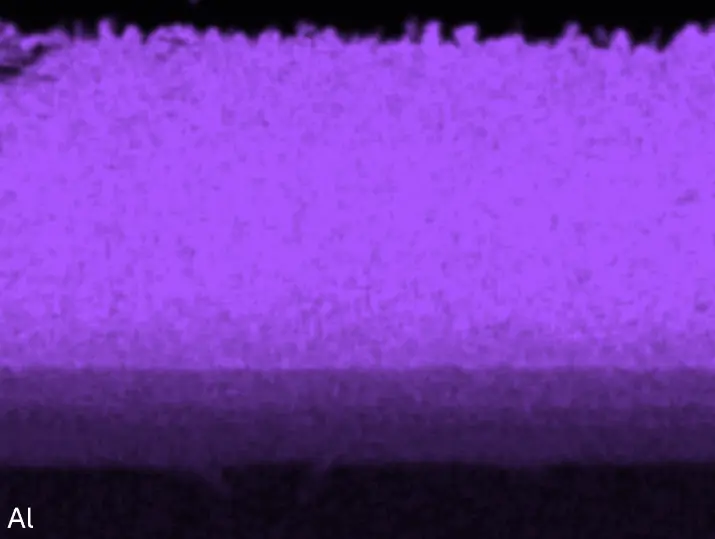

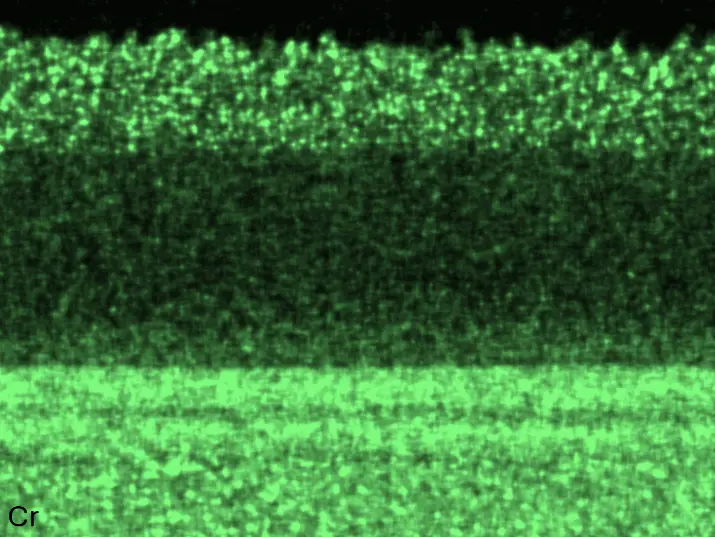

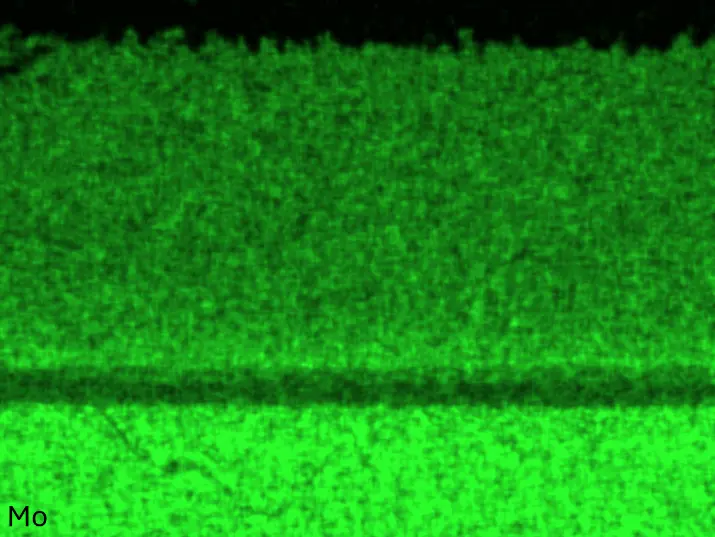

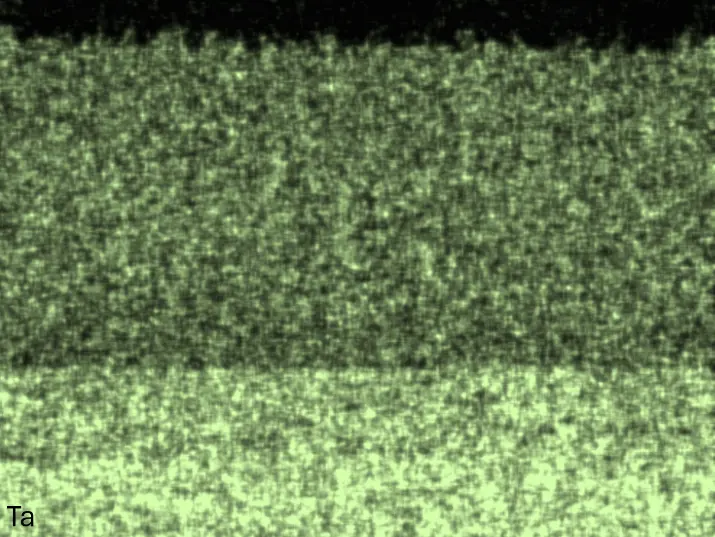

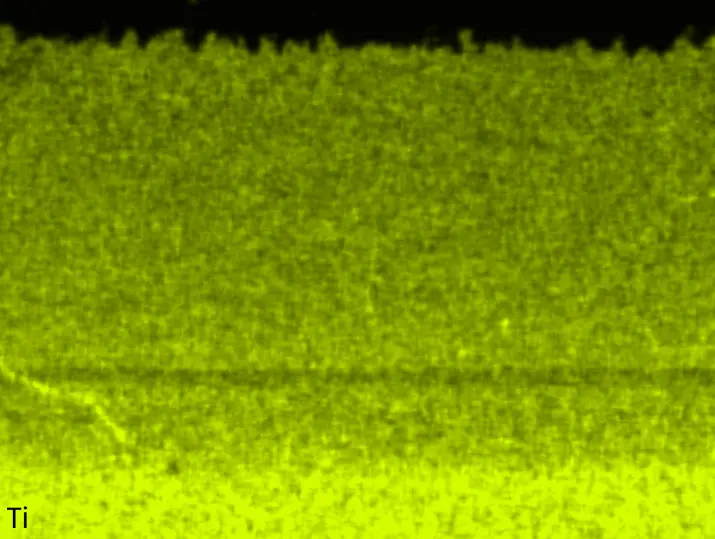

Figure 4 compares more detailed micrographs of coating cross sections and corresponding EDS elemental line scans. The dark grey elongated structures on the top surface of C-Ti3 are TiN from the homogenization heat treatment, which were not removed completely by grinding prior to the aluminizing process. The coatings of C0 and C-Ti3 appear single-layered and single-phased, judging by SEM-BSE contrast. For C-Al3, the eutectoid-like Cr-Ta-rich Laves phase lamellae of the bulk material are retained in the coating. This results in higher scattering of Al, Cr, and Ta concentrations in the EDS elemental line scan. All three RHEAs show Al concentrations of around 75 at.% in the coatings (Table 2), suggesting the formation of Al3(Cr,Mo,Ta,Ti) aluminide phase analogous to Al3Ti with D022 structure (Pearson symbol tI8, space group number 139) in the binary Al-Ti system [23]. For C0 and C-Al3, elements Cr, Mo, Ta, and Ti seem to be in equimolar composition in the coatings, whereas for C-Ti3, the Ti concentration is higher than Cr, Mo, and Ta. Planar diffusion fronts of the coatings indicated by SEM-BSE are confirmed by EDS elemental line scans (Figure 4b) and EDS elemental mappings (Figure 5). The line scans show steep elemental gradients at coating/substrate interfaces for all three RHEAs.

Table 2. Mean EDS compositions of the aluminizing coatings after 900 °C for 7 h in at.%.

|

RHEA |

Abbr. |

Al |

Cr |

Mo |

Ta |

Ti |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

AlCrMoTaTi |

C0 |

75 ± 1 |

6 ± 1 |

6 ± 1 |

6 ± 1 |

7 ± 1 |

|

Al3CrMoTaTi |

C-Al3 |

69 ± 11 |

12 ± 12 |

7 ± 2 |

4 ± 3 |

8 ± 2 |

|

AlCrMoTaTi3 |

C-Ti3 |

73 ± 1 |

4 ± 1 |

4 ± 1 |

5 ± 1 |

14 ± 2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| (a) | (b) |

Figure 4. Comparison of resulting coatings after aluminizing RHEAs C0 (top), C-Al3 (middle), and C-Ti3 (bottom) at 900 °C for 7 h: (a) SEM-BSE cross sections; (b) EDS elemental line scans along the vertical arrows in (a), respectively. The vertical dashed lines in (b) indicate the coating/substrate interfaces.

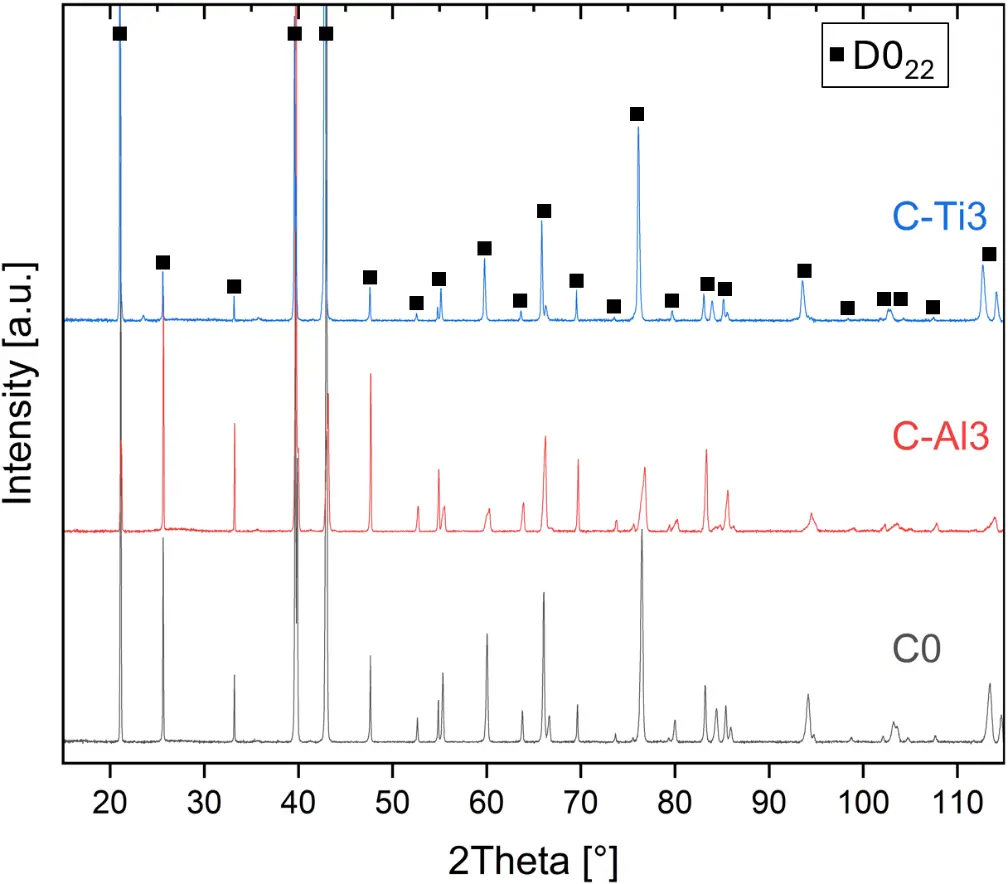

XRD diffraction patterns of all RHEAs in the aluminized condition confirm the same formed phase with D022 structure (prototype Al3Ti, Pearson symbol tI8, space group number 139) (Figure 6a). At higher diffraction angles, peak splitting is detectable, suggesting the presence of two D022 phases with a low lattice parameter mismatch. Prior to aluminizing, the RHEAs exhibited different phases in as-homogenized condition: C0 forms bcc solid solution (prototype W, Pearson symbol cI2, space group number 229) and ordered B2 phase (prototype CsCl, Pearson symbol cP2, space group number 221), C-Al3 forms C14/C36 hexagonal Laves phase (prototype MgZn2/MgNi2, Pearson symbol hP12/hP24, space group 194) and bcc solid solution, and C-Ti3 forms single-phased bcc solid solution. Hence, the Al concentration in the Al-Cr-Mo-Ta-Ti system significantly affects phase formation. As Al concentration increases, the following crystal structures appear to be stabilized: bcc, B2, C14/C36, and D022. This effect should be subject to future investigations.

|

|

| (a) | (b) |

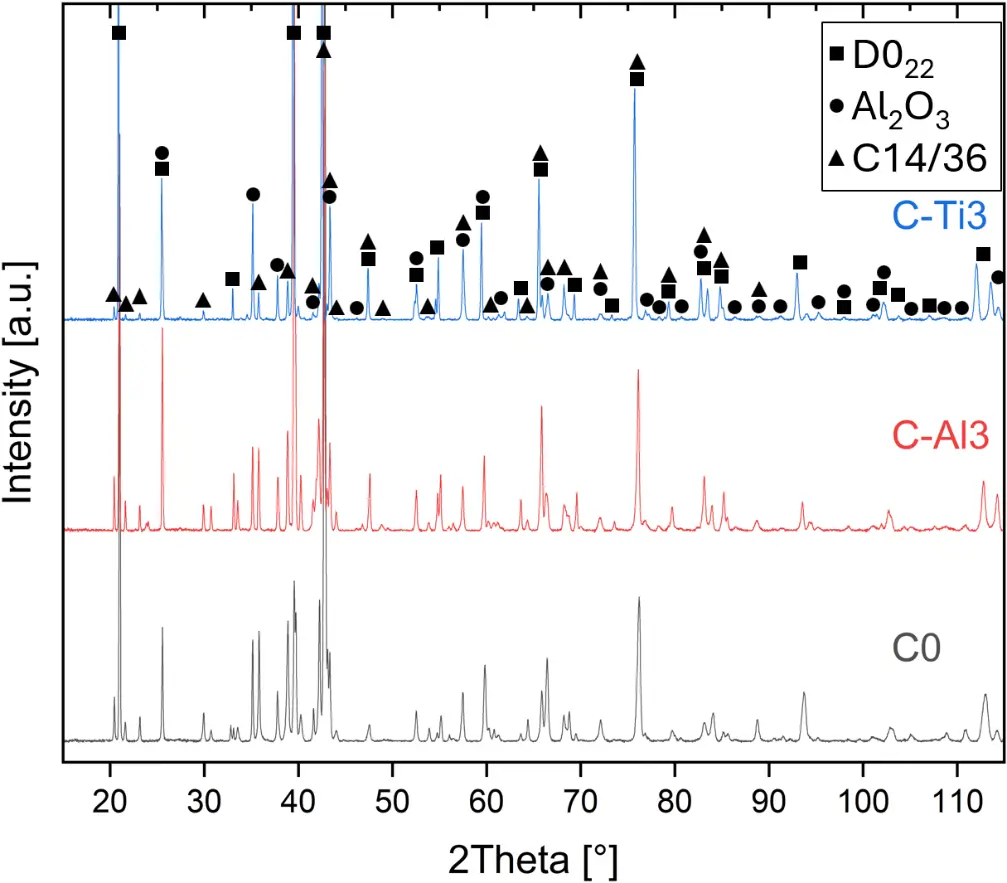

Figure 6. XRD diffraction patterns of different material conditions: (a) aluminized at 900 °C for 6 h; (b) oxidized at 1000 °C for 48 h after aluminizing.

The microstructure of aluminized C-Al3 (Figure 4a and Figure 5b) shows Cr-Ta-rich Laves phase lamellae, which are not detectable in the diffraction pattern, indicating too low volume fraction in the surface-near analyzed specimen volume. Thermo-Calc simulations were conducted for a chemical composition of the aluminizing coating as analyzed by EDS elemental line scans (Table 2): 76 at.% Al and 6 at.% Cr, Mo, Ta, and Ti, respectively. The simulations predict three stable phases at 900 °C aluminizing temperature: 90 vol.% of two different Al3(Cr,Mo,Ta,Ti) phases with D022 structure—one being Mo-rich and the other Ta-rich—and 10 vol.% monoclinic Al11Cr2. Although no monoclinic Al11Cr2 is detectable in the measured XRD diffraction patterns, the predicted presence of two similar phases with D022 structure is in line with observed peak splitting caused by low lattice parameter mismatch. These findings clearly show the formation of D022 Al3(Cr,Mo,Ta,Ti) aluminide phase—analogous to Al3Ti in the binary Al-Ti system—during aluminizing of the substrate RHEAs C0, C-Al3, and C-Ti3 despite their significant differences in chemical compositions.

3.2. Oxidation Testing

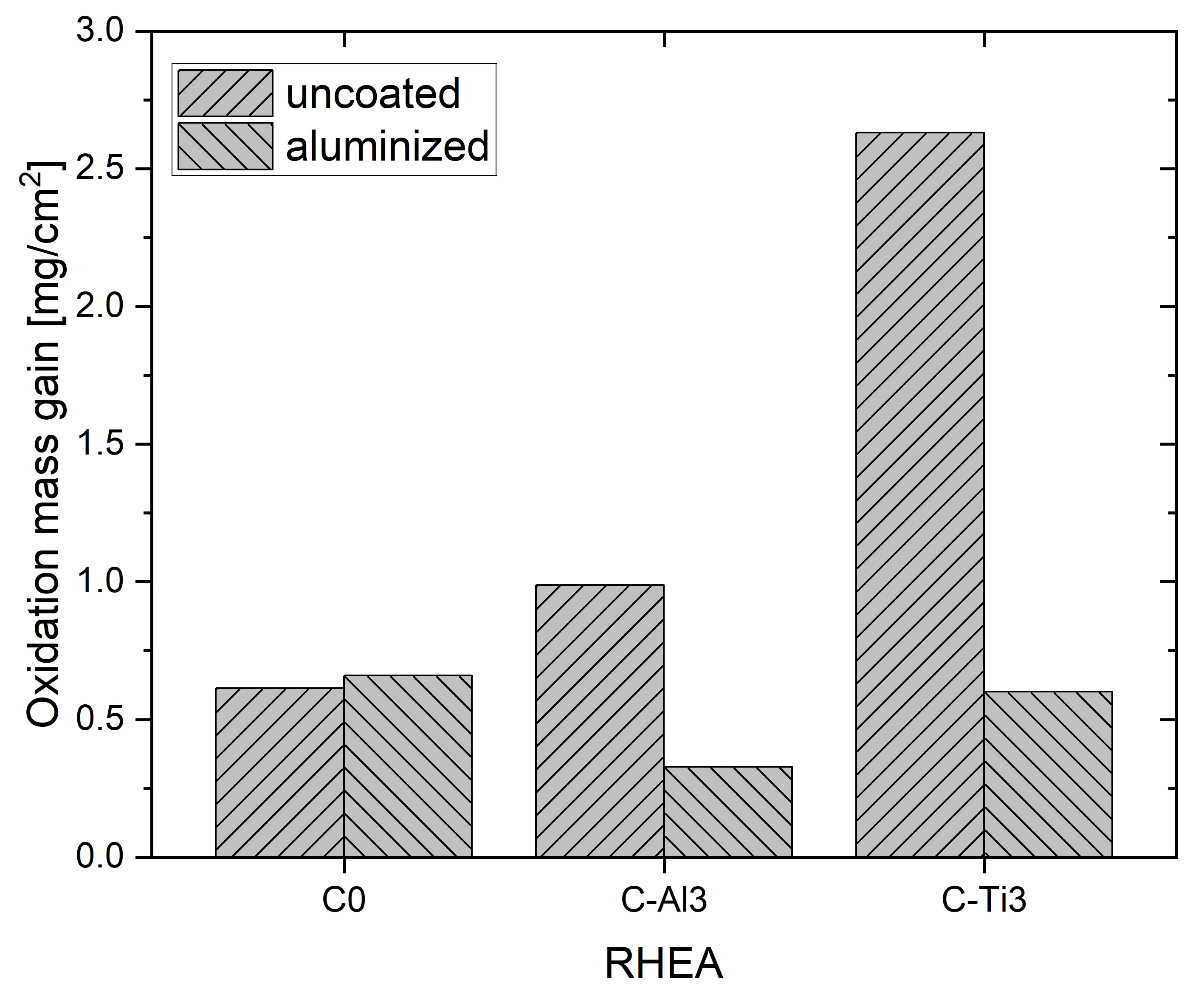

Isothermal oxidation testing at 1000 °C for 48 h in ambient air resulted in positive mass gains, as shown in Figure 7. For C0, mass gains in the uncoated and aluminized conditions are similar, with 0.5 and 0.6 mg/cm2, respectively. In contrast, C-Al3 and C-Ti3 show significantly lower mass gains after aluminizing: a decrease from 1.0 to 0.3 mg/cm2 for C-Al3 and from 2.6 down to 0.6 mg/cm2 for C-Ti3. These findings suggest significantly improved oxidation resistance of C-Al3 and C-Ti3 due to aluminizing by pack cementation. In comparison, oxidation of binary Al3Ti at 1000 °C in pure O2 gas flow was found to follow parabolic kinetics, resulting in approximately 0.5 mg/cm2 mass gain after 48 h [24]. For 100 h at 900 °C in air, oxidation mass gain of around 1.0 mg/cm2 was measured [25]. Chen et al. [26] modified Al3Ti with low additions of Mn, Fe, or Ni, changing the D022 phase structure to L12 (prototype Cu3Au, Pearson symbol cP4, space group number 221). They observed oxidation mass gains of 1.42, 0.30, and 0.30 mg/cm2 after 60 h at 1000 °C in air, respectively. Similarly, Lee et al. [27] added Cr to Al3Ti and found enhanced oxidation resistances of 0.1–0.2 mg/cm2 after 48 h at 1000 °C in air. Hence, our findings for aluminized RHEAs are in good agreement with the oxidation behavior of binary and ternary Al3Ti intermetallic compounds. Furthermore, oxidation mass gains of typical Ni-based superalloys under these isothermal conditions are in the range of 0.2–2.0 mg/cm2 [28,29,30], highlighting the effectiveness of applied aluminizing coatings for RHEAs in the system Al-Cr-Mo-Ta-Ti.

Surprisingly, mass gains in the uncoated condition for all three RHEAs in this study contradict our previous results [21]. In the previous work, homogenization heat treatment was conducted at 1300 °C for 48 h and led to incomplete homogenization. Subsequent oxidation at 1000 °C for 48 h in ambient air resulted in mass gains of 1.3, 1.0, and 1.6 mg/cm2 for C0, C-Al3, and C-Ti3, respectively. In contrast, the study at hand resulted in 0.5, 1.0, and 2.6 mg/cm2 (Figure 7) for identical oxidation conditions. Hence, oxidation mass gains in the previous study with incomplete homogenization were lower for C0, identical for C-Al3, and higher for C-Ti3 compared to the study on hand. Gorr et al. [3] investigated equimolar AlCrMoTaTi after vacuum arc melting and homogenization heat treatment at 1200 °C for 20 h and found 1.0 mg/cm2 oxidation mass gain. No bulk microstructure was reported, but both their homogenization temperature and duration were lower/shorter compared to the current work with 1450 °C for 48 h (complete homogenization, Figure 2) and compared to our previous work with 1300 °C for 48 h (incomplete homogenization). Hence, incomplete homogenization most likely occurred in Gorr’s investigation as in our previous study. In conclusion, completely homogenized AlCrMoTaTi showed the lowest oxidation mass gains of 0.5 mg/cm2 (current work) as opposed to incomplete homogenized conditions with 1.0 and 1.3 mg/cm2 (Gorr et al. [3] and previous study [21], respectively). Different degrees of homogenization of the bulk material may affect bulk material phase formation and/or diffusion coefficients of species in bulk material phases. Consequently, the degree of homogenization also affects oxidation resistance, since the formation of oxide scales is driven by the diffusion of different species between bulk material phases and oxide phases towards the bulk/oxide and oxide/atmosphere interfaces.

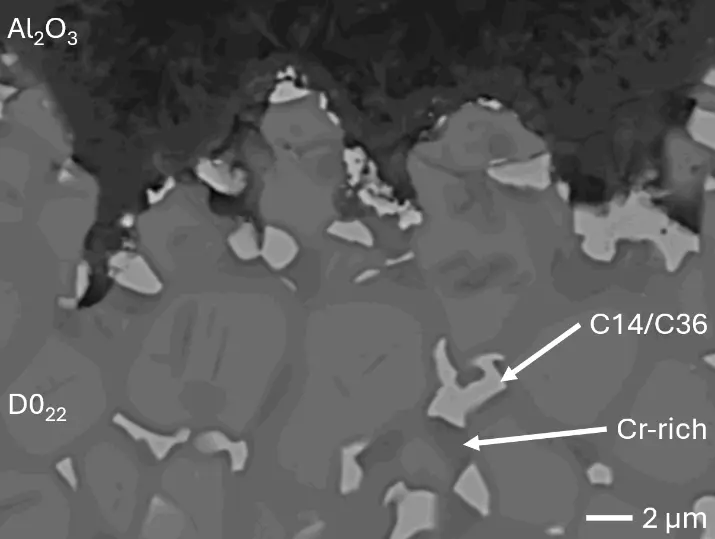

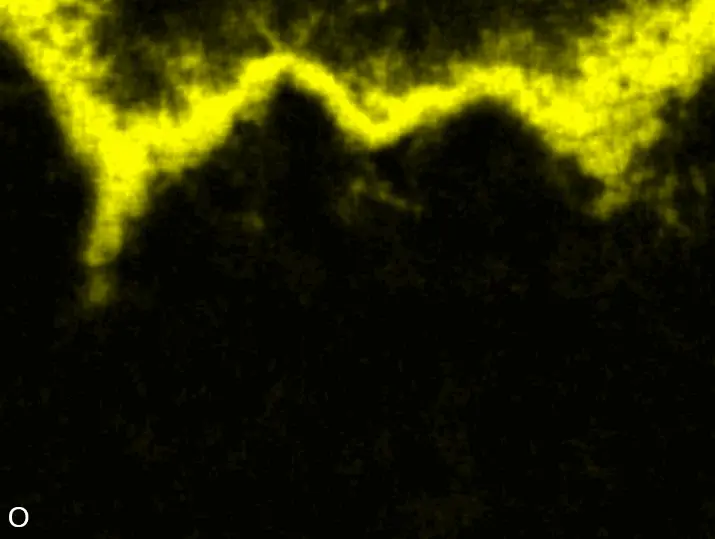

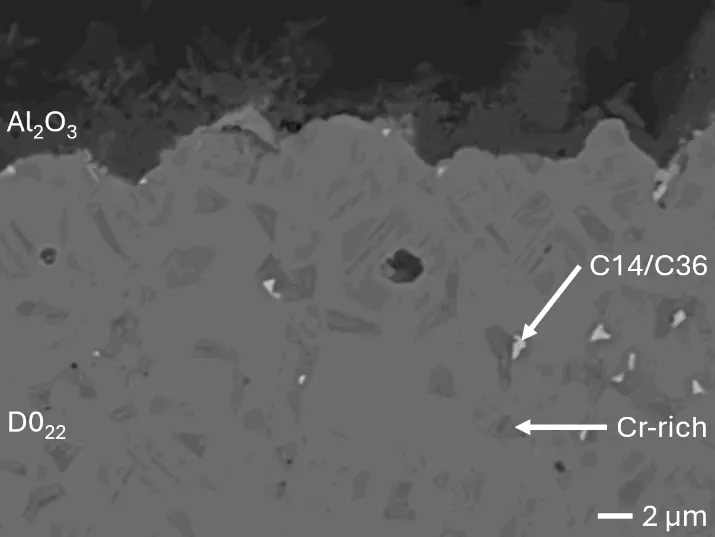

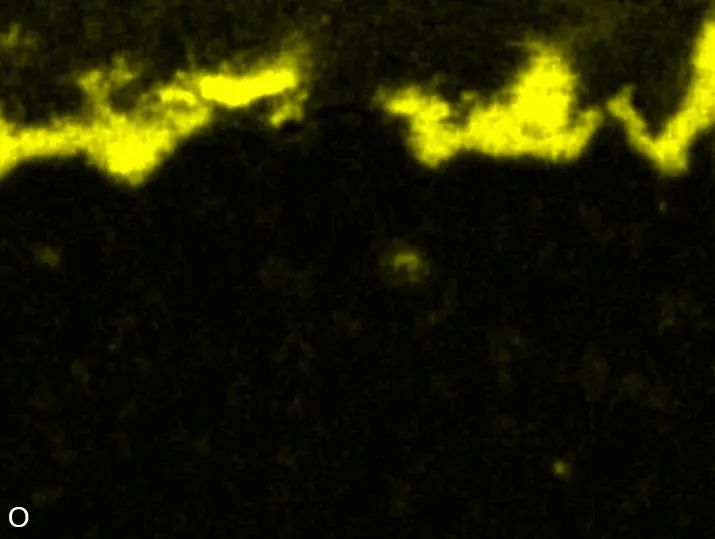

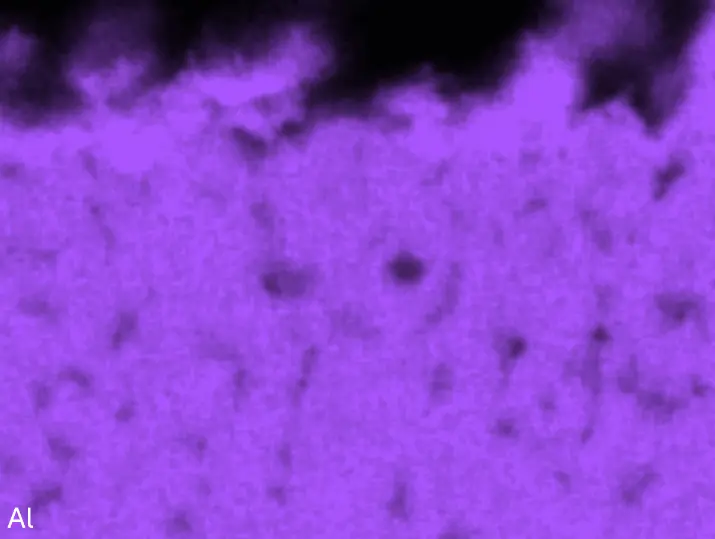

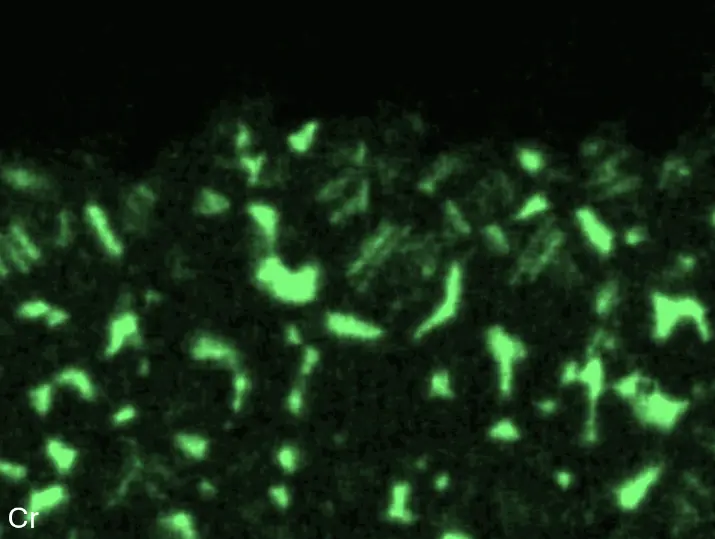

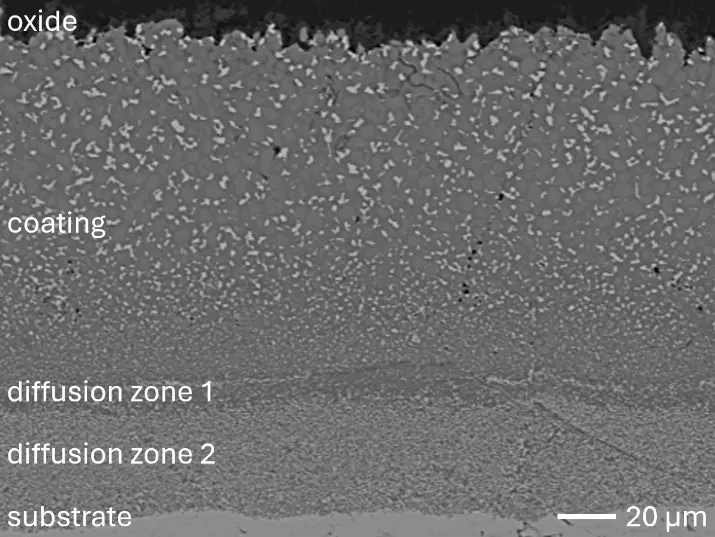

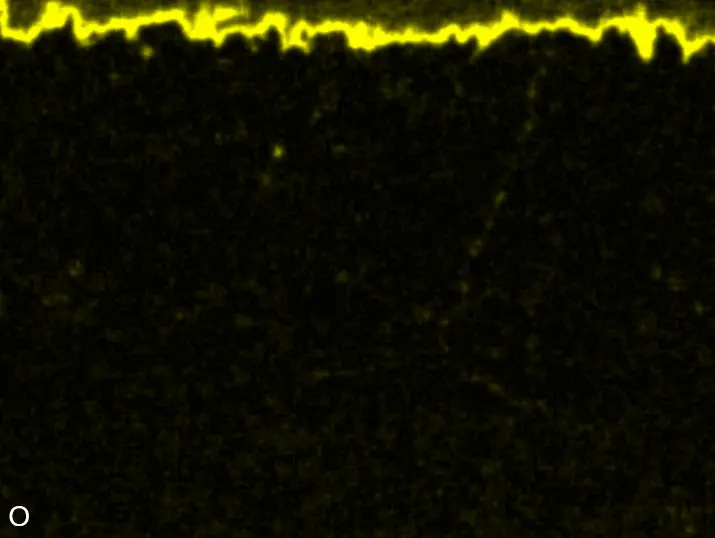

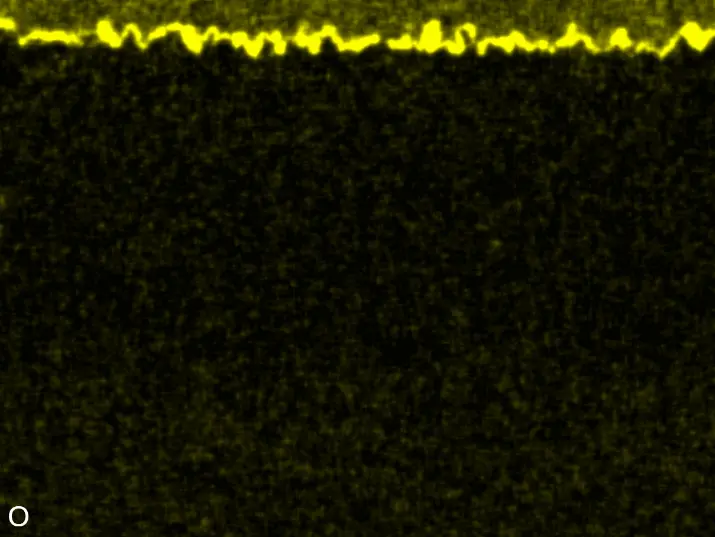

Figure 8 compares SEM-BSE micrographs and EDS elemental mappings of entire coatings in cross section after oxidation testing. For all three RHEAs, the coatings remained intact and compact, and a thin, single-layered alumina scale formed at the coating surface with a thickness of 1–2 µm (Figure 6b and Figure 9). This is in contrast with uncoated C0, C-Al3, and C-Ti3, all of which form multi-layered oxide scales under these oxidation conditions [3,4,6,7,21]. At the coating/substrate interface, inward diffusion of Al and outward diffusion of Cr, Mo, Ta, and Ti is detectable, caused by steep gradients in elemental concentrations (Figure 4b). In the coatings, 1–2 µm large light grey Cr-Ta-rich Laves phase particles were precipitated, and Cr-rich darker regions can be observed (Figure 9). These findings indicate that the initially single-phased D022 Al3(Cr,Mo,Ta,Ti) coating is not thermodynamically stable at the oxidation temperature of 1000 °C.

XRD analyses (Figure 6b) show that the same oxide phase of alumina (D51, α-Al2O3/corundum, Pearson symbol hR10, space group number 167) formed on all three aluminized RHEAs during oxidation for 48 h at 1000 °C in air. In addition to the peaks of the formed alumina scale, peaks of the coating underneath are clearly visible in the diffraction patterns after oxidation. Hence, the alumina scales are fully transmitted by X-rays, and all formed oxide phases are captured in the diffraction patterns. No further oxide phases are detectable, such as chromia, titania or CrTaO4 as observed for oxidized uncoated Al-Cr-Mo-Ta-Ti RHEAs [3,4,6,7,21]. The D022 structure of the Al3(Cr,Mo,Ta,Ti) coating is retained during oxidation, but the hexagonal Laves phase (C14/C36) is precipitated.

|

|

|

| (a) | (b) | (c) |

Figure 8. Cross sections of entire aluminizing coatings in the oxidized condition after 48 h at 1000 °C; (a) C0; (b) C-Al3; (c) C-Ti3.

4. Discussion

The aluminizing process by pack cementation is categorized into high-activity and low-activity processes. In this study, pure Al powder was used as a diffusion source. Hence, the thermodynamic activity of Al equals unity, and aluminizing is categorized as a high-activity process [12]. Due to the high chemical potential gradient of Al at the substrate surface, Al inward diffusion is the dominant mechanism for coating formation. Consequently, Al solid-state diffusion through the formed D022 Al3(Cr,Mo,Ta,Ti) layer to the coating/substrate interface is rate limiting. This results in the observed coating thickness curves (Figure 3) with plateaus for aluminizing durations exceeding 9 h at 900 °C. Secondly, the Cr-Ta-rich Laves phase lamellae in C-Al3 are retained in the coating during the aluminizing process, i.e., Al inward diffusion is dominant compared to diffusion of Cr, Mo, Ta, and Ti, respectively. And thirdly, the Ti concentration in the coating of C-Ti3 RHEA is higher than the concentrations of Cr, Mo, and Ta, respectively. This is also the case for the Ti-rich substrate RHEA. Concentration ratios of Ti to Cr/Mo/Ta are 3.0 for the substrate composition and 2.8 for the aluminized coating, i.e., they are well comparable. Hence, the aluminizing coating was formed due to dominant Al inward diffusion into the substrate for all three RHEAs investigated in this study. This is in good agreement with the observation that no pores were detectable in coatings or near the interfaces coating/substrate of all specimens investigated. The formation of pores would require dominant outward diffusion of substrate elements with condensation of the countercurrent flux of vacancies, according to the Kirkendall mechanism [12].

The effect of aluminizing duration on the coating thicknesses (Figure 3) showed the slowest kinetics for C0 and comparable high kinetics for C-Al3 and C-Ti3. Equimolar C0 as reference RHEA in the Al-Cr-Mo-Ta-Ti system shows a medium initial Al concentration of 20 at.% and a homologous temperature of 0.59 at 900 °C aluminizing temperature (Table 3). In contrast, Al-rich C-Al3 exhibits a higher initial Al concentration of 42.8 at.% and a higher homologous temperature of 0.66; vice versa for Ti-rich C-Ti3 with 14.3 at.% and 0.54. Since diffusion coefficients of Al in Al-Cr-Mo-Ta-Ti RHEAs are not available in literature, homologous temperatures are used as rough indicators for diffusion. Hence, the Al gradient and relative activity at the substrate surface are highest for C-Ti3 and lowest for C-Al3, whereas Al inward diffusion is slowest in C-Ti3 and fastest in C-Al3. From resulting thickness curves—comparable for C-Al3 and C-Ti3, slower for C0—it can be concluded: (1) both a high Al gradient and increased Al diffusion facilitate the aluminizing coating process, and (2) in contrast, a medium Al gradient and medium Al diffusion at the same time result in slower aluminizing kinetics. With increasing thickness of the D022 Al3(Cr,Mo,Ta,Ti) coating, Al diffusion through this phase towards the coating/substrate interfaces becomes increasingly rate-controlling. Since all three RHEAs under investigation formed the same D022 phase, Al diffusion can be assumed to be equal for higher coating thicknesses.

During isothermal oxidation testing of the aluminized RHEAs, Laves phase particles of 1–2 µm diameter formed in the retained D022 coatings (Figure 6b and Figure 9). Laves phases as intermetallic compounds are known to show brittle mechanical behavior. Hence, they act embrittling on metallic materials when precipitated. This effect increases the risk of spallation during long-term service conditions at high temperatures, especially if the precipitated Laves phase has a higher molar volume compared to the initial coating phase. Mechanical stress would build up in the coating, resulting in crack initiation and growth. Thermal cycling during operation causes additional thermal stresses, further increasing the risk of spallation in operation. Consequently, the formation of Laves phase in the produced aluminizing coatings on RHEAs Al-Cr-Mo-Ta-Ti should be investigated in more detail, clarifying its effect on long-term coating stability and oxidation protection. Another possible critical failure mode of aluminizing coatings for oxidation protection is the depletion of the Al reservoir in the coating due to alumina scale formation. Long-term oxidation tests should be conducted to investigate the protectiveness even after several hundred hours. Thirdly, internal corrosion underneath formed oxide scales can be critical for long-term coating stability. While C0 and C-Ti3 are prone to internal formation of TiN in uncoated conditions, no indications for internal corrosion were observed after oxidation in aluminized conditions. Hence, the promoted formation of single-layered dense alumina scales suppresses inward diffusion of N and consequently TiN formation. In summary, the developed aluminizing process by pack cementation for the RHEAs C0, C-Al3, and C-Ti3 produced Al-rich diffusion coatings. While their long-term stability remains under investigation, enhanced oxidation protection compared to uncoated RHEAs has been proven.

Table 3. Comparison of the three RHEAs in properties relevant for the diffusion-driven aluminizing process: Al concentration, simulated solidus temperature and resulting homologous temperature at 900 °C.

|

RHEA |

Abbr. |

Al/at.% |

Ts/°C |

Thom(900 °C)/- |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

AlCrMoTaTi |

C0 |

20.0 |

1728 |

0.59 |

|

Al3CrMoTaTi |

C-Al3 |

42.8 |

1499 |

0.66 |

|

AlCrMoTaTi3 |

C-Ti3 |

14.3 |

1886 |

0.54 |

5. Conclusions

For the first time, three different RHEAs in the system Al-Cr-Mo-Ta-Ti were successfully aluminizing coated by pack cementation: equimolar AlCrMoTaTi, Al-rich Al3CrMoTaTi, and Ti-rich AlCrMoTaTi3.

-

-

Compact, uniform, and adhesive Al-rich coatings were achieved with no delaminations and no pores detectable.

-

-

The aluminizing process can be further optimized by using shorter coating durations (e.g., 5 h) at 900 °C for thinner coatings (50–80 µm).

-

-

All three RHEAs formed single-layered D022 Al3(Cr,Mo,Ta,Ti) intermetallic compound coatings analogous to Al3Ti in the binary Al-Ti system.

-

-

Isothermal oxidation at 1000 °C for 48 h in ambient air resulted in the formation of compact, uniform, and adhesive single-layered alumina scales with 1–2 µm thickness. C14/C36 hexagonal Laves phase particles precipitated in the coatings with 1–2 µm size, and additional Cr-rich regions were found. While the uncoated condition is prone to internal corrosion due to TiN formation beneath the forming multi-layered oxide scales, no indications of internal corrosion were observed in the aluminized condition.

-

-

Hence, isothermal oxidation resistances of AlCrMoTaTi, Al3CrMoTaTi, and AlCrMoTaTi3 were enhanced by aluminizing coating to mass gains as low as binary Al3Ti intermetallic compounds and Ni-based superalloys.

-

-

Further in-depth investigations are necessary regarding long-term isothermal oxidation, cyclic oxidation behavior, and long-term microstructural stability of the aluminizing coatings at high temperatures.

Acknowledgments

This research project was supported by the European Union and the Free State of Saxony under EFRE which is gratefully acknowledged.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.H., U.G., T.D. and T.W.; Methodology, F.H., U.G. and T.D.; Validation, F.H., E.R. and T.D.; Formal Analysis, F.H.; Investigation, F.H., E.R. and W.P.; Resources, F.H., E.R., W.P. and T.D.; Data Curation, F.H.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, F.H.; Writing—Review & Editing, F.H., T.D. and U.G.; Visualization, F.H.; Supervision, T.D., U.G. and T.W.; Project Administration, F.H., T.D. and T.W.; Funding Acquisition, F.H., T.D. and T.W.

Ethics Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Funding

F.H. gratefully acknowledges financial support for this research project by KMM-VIN (European Virtual Institute on Knowledge-based Multifunctional Materials AISBL) with Prof. Appendino Research Fellowship 2024 (16th Call).

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Senkov ON, Wilks GB, Miracle DB, Chuang CP, Liaw PK. Refractory high-entropy alloys. Intermetallics 2010, 18, 1758–1765. DOI:10.1016/j.intermet.2010.05.014 [Google Scholar]

- Senkov ON, Miracle DB, Chaput KJ, Couzinie JP. Development and exploration of refractory high entropy alloys—A review. J. Mater. Res. 2018, 33, 3092–3128. DOI:10.1557/jmr.2018.153 [Google Scholar]

- Gorr B, Müller F, Azim M, Christ HJ, Müller T, Chen H, et al. High-Temperature Oxidation Behavior of Refractory High-Entropy Alloys. Oxid. Met. 2017, 88, 339–349. DOI:10.1007/s11085-016-9696-y [Google Scholar]

- Müller F, Gorr B, Christ HJ, Chen H, Kauffmann A, Heilmaier M. Effect of microalloying with silicon on high temperature oxidation resistance of novel refractory high-entropy alloy Ta-Mo-Cr-Ti-Al. Mater. High Temp. 2018, 35, 168–176. DOI:10.1080/09603409.2017.1389115 [Google Scholar]

- Müller F, Gorr B, Christ HJ, Müller J, Butz B, Chen H, et al. On the oxidation mechanism of refractory high entropy alloys. Corros. Sci. 2019, 159, 108161. DOI:10.1016/j.corsci.2019.108161 [Google Scholar]

- Schellert S, Gorr B, Christ HJ, Pritzel C, Laube S, Kauffmann A, et al. The Effect of Al on the Formation of a CrTaO4 Layer in Refractory High Entropy Alloys Ta-Mo-Cr-Ti-xAl. Oxid. Met. 2021, 96, 333–345. DOI:10.1007/s11085-021-10046-7 [Google Scholar]

- Schellert S, Gorr B, Laube S, Kauffmann A, Heilmaier M, Christ HJ. Oxidation mechanism of refractory high entropy alloys Ta-Mo-Cr-Ti-Al with varying Ta content. Corros. Sci. 2021, 192, 109861. DOI:10.1016/j.corsci.2021.109861 [Google Scholar]

- Schellert S, Weber M, Christ HJ, Wiktor C, Butz B, Galetz MC, et al. Formation of rutile (Cr,Ta,Ti)O2 oxides during oxidation of refractory high entropy alloys in Ta-Mo-Cr-Ti-Al system. Corros. Sci. 2023, 211, 110885. DOI:10.1016/j.corsci.2022.110885 [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Z, Peng X, Lü W, Yang S, Li H, Guo H, et al. Ultra-high temperature oxidation resistant refractory high entropy alloys fabricated by laser melting deposition: Al concentration regulation and oxidation mechanism. Corros. Sci. 2023, 224, 111537. DOI:10.1016/j.corsci.2023.111537 [Google Scholar]

- Lanoy F, White EMH, Schäfer B, Tang C, Schroer C, Gorr B, et al. Influence of the Cr to Ti Ratio on the High-Temperature Oxidation Behavior of TaMoCrTiAl Complex Concentrated Alloys in Nitrogen-Free Atmospheres. Mater. Corros. 2025, 1–11. DOI:10.1002/maco.70070 [Google Scholar]

- Tang C, Radi A, Dürrschnabel M, Jäntsch U, Klimenkov M, Kauffmann A, et al. Design of lightweight high temperature structural materials based on Ti–Mo–Ta–Cr–Al refractory compositionally complex alloys, Part II: High temperature oxidation behavior. J. Alloy. Metall. Syst. 2025, 12, 100217. DOI:10.1016/j.jalmes.2025.100217 [Google Scholar]

- Bianco R, Rapp RA. Pack cementation diffusion coatings. In Metallurgical and Ceramic Protective Coatings, 1st ed.; Stern KH, Ed.; Chapman & Hall: London, UK, 1996; pp. 236–260. DOI:10.1007/978-94-009-1501-5 [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich AS, Galetz MC. Protective Aluminide Coatings for Refractory Metals. Oxid. Met. 2016, 86, 511–535. DOI:10.1007/s11085-016-9650-z [Google Scholar]

- Beck K, Ulrich AS, Czerny AK, White EMH, Heilmaier M, Galetz MC. Aluminide diffusion coatings for improving the pesting behavior of refractory metals. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2024, 476, 130205. DOI:10.1016/j.surfcoat.2023.130205 [Google Scholar]

- Sheikh S, Gan L, Tsao TK, Murakami H, Shafeie S, Guo S. Aluminizing for enhanced oxidation resistance of ductile refractory high-entropy alloys. Intermetallics 2018, 103, 40–51. DOI:10.1016/j.intermet.2018.10.004 [Google Scholar]

- Sheikh S, Gan L, Montero X, Murakami H, Guo S. Forming protective alumina scale for ductile refractory high-entropy alloys via aluminizing. Intermetallics 2020, 123, 106838. DOI:10.1016/j.intermet.2020.106838 [Google Scholar]

- Choi WJ, Park CW, Song Y, Choi H, Byun J, Kim YD. Oxidation Behavior of Pack-Cemented Refractory High-Entropy Alloy. JOM 2020, 72, 4594–4603. DOI:10.1007/s11837-020-04439-3 [Google Scholar]

- Günen A, Döleker KM, Kanca E, Akhtar MA, Patel K, Mukherjee S. Oxidation resistance of aluminized refractory HfNbTaTiZr high entropy alloy. J. Alloys Compd. 2024, 999, 175100. DOI:10.1016/j.jallcom.2024.175100 [Google Scholar]

- Yang R, Yang H, Zhang M, Shi X, Qiao J. Refractory high-entropy aluminized coating with excellent oxidation resistance and lubricating property prepared by pack cementation method. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2023, 473, 129967. DOI:10.1016/j.surfcoat.2023.129967 [Google Scholar]

- Huang SW, Luo JT, Chang ZH, Shen TE, Liang JT, Hsu WL, et al. Dual coating layers to enhance oxidation resistance for refractory high-entropy alloys. Results Mater. 2024, 21, 100508. DOI:10.1016/j.rinma.2023.100508 [Google Scholar]

- Häslich F, Gaitzsch U, Weißgärber T. Oxidation Resistant Refractory High-Entropy Alloys in the System Al-Cr-Mo-Ta-Ti Processed by Powder Metallurgy. In Proceedings of the 21st Plansee Seminar 2025, 1st ed.; Wex KH, Kestler H, Czettl C, Eds.; Plansee Group Functions Austria GmbH: Reutte, Austria, 2025; pp. 79–89; Page 20 of the pdf File. Available online: https://www.plansee-seminar.com/?action=GetFile&id=231 (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Häslich F, Gaitzsch U, Weißgärber T. PM-Processing, Microstructure And High-Temperature Performance of Refractory High-Entropy Alloys Al-Cr-Mo-Ta-Ti. In Euro PM2025 Proceedings, 1st ed.; EPMA: Chantilly, France, 2025. DOI:10.59499/EP256766250 [Google Scholar]

- Nakayama Y, Mabuchi H. Formation of ternary L12 compounds in Al3Ti-base alloys. Intermetallics 1993, 1, 41–48. DOI:10.1016/0966-9795(93)90020-V [Google Scholar]

- Umakoshi Y, Yamaguchi M, Sakagami T, Yamane T. Oxidation resistance of intermetallic compounds Al3Ti and TiAl. J. Mater. Sci. 1989, 24, 1599–1603. DOI:10.1007/BF01105677 [Google Scholar]

- Shida Y, Anada H. Oxidation Behavior of Binary Ti–Al Alloys in High Temperature Air Environment. Mater. Trans. JIM 1993, 34, 236–242. DOI:10.2320/matertrans1989.34.236 [Google Scholar]

- Chen S, Zhang W, Zhang Y, Hu G, Li T, Shen J, et al. Oxidation behavior of Al3Ti-based L12-type intermetallic alloys. Scr. Metall. Et Mater. 1992, 27, 455–460. DOI:10.1016/0956-716X(92)90210-6 [Google Scholar]

- Lee DB, Kim SH, Niinobe K, Yang CW, Nakamura M. Effect of Cr on the high temperature oxidation of L12-type Al3Ti intermetallics. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2000, 290, 1–5. DOI:10.1016/S0921-5093(00)00956-4 [Google Scholar]

- Göbel M, Rahmel A, Schütze M. The isothermal-oxidation behavior of several nickel-base single-crystal superalloys with and without coatings. Oxid. Met. 1993, 39, 231–261. DOI:10.1007/BF00665614 [Google Scholar]

- Greene GA, Finfrock CC. Oxidation of Inconel 718 in Air at High Temperatures. Oxid. Met. 2001, 55, 505–521. DOI:10.1023/A:1010359815550 [Google Scholar]

- Lee DB. High-temperature Oxidation of Ni-based Inconel 713 Alloys at 800–1100 ℃ in Air. J. Kor. Inst. Surf. Eng. 2011, 44, 196–200. DOI:10.5695/JKISE.2011.44.5.196 [Google Scholar]