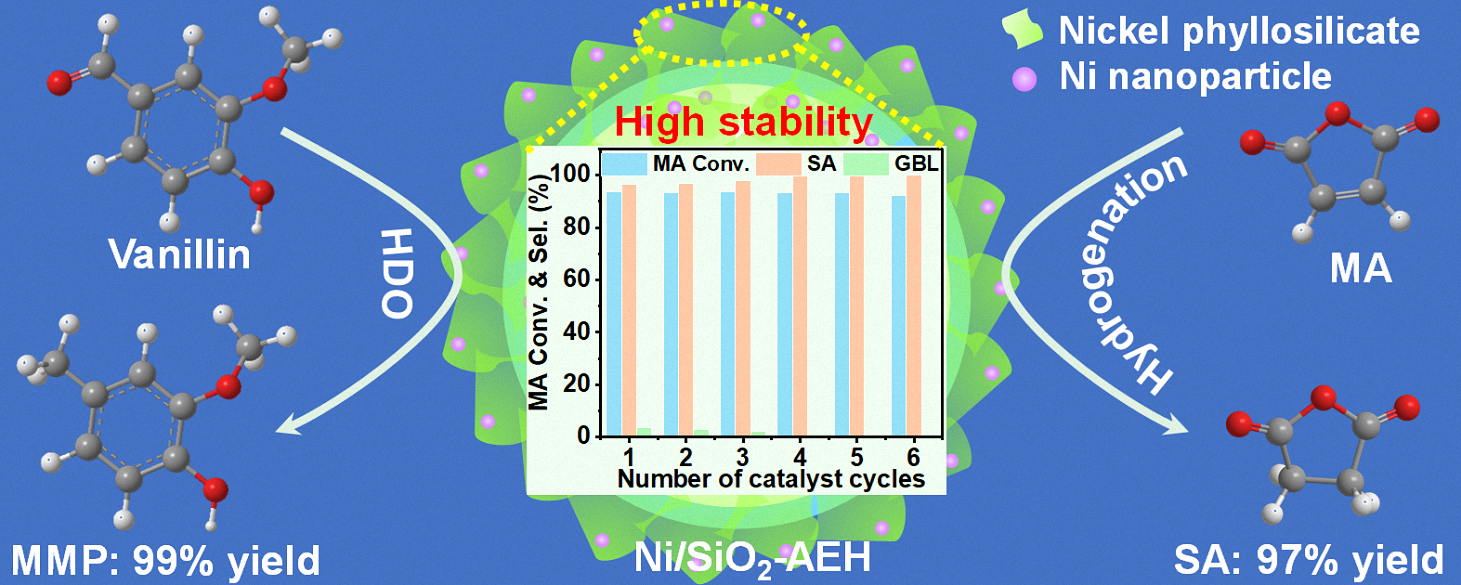

Enhanced Stability of Nickel Phyllosilicate Anchored Ni/SiO2 Catalyst for Liquid-Phase Hydrogenation and Hydrodeoxygenation

Received: 18 November 2025 Revised: 08 December 2025 Accepted: 19 January 2026 Published: 26 January 2026

© 2026 The authors. This is an open access article under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

1. Introduction

Heterogeneous transition metal-based catalysts are of vital importance in the hydrogenation of unsaturated bonds (such as C=C, C=O, C≡N), offering a wide range of industrial applications [1,2,3]. Relative to the restriction of precious metal reserves and price, non-precious metal catalysts possess incomparable features, such as low cost, earth-abundant reserves, and outstanding selectivity, promising for extensive applications in the fields of CO2 hydrogenation, selective hydrogenation of α,β-unsaturated aldehydes or alkynes [4,5,6,7,8,9]. However, the primary challenges facing the industrialization of supported non-noble metal catalysts lie in their relatively low intrinsic activity and poor stability (e.g., sintering, carbon deposition, and metal leaching) [5,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19]. Strategies are proposed to improve the stability of supported non-noble catalysts via optimizing active components, constructing overlayers on the metal catalyst surface, and strengthening the metal-support interactions [20,21,22,23,24,25]. Ordinarily, supports with strong metal anchoring sites (such as N, O, P, S) are attractive for stabilizing metal NPs through strong metal-support interaction (SMSI), thereby inhibiting their leaching [23,26,27]. Mesoporous silicate materials with high thermal stability are regarded as attractive precursors for dispersing and stabilizing metal nanoparticles (NPs) via the formation of strong surface Si–O–M bonds [20,28,29]. The lamellar structure of phyllosilicates exposes abundant metal-SiO2 interfaces, which act as the catalytic active sites in some hydrogenation and hydrodeoxygenation (HDO) reactions [30,31,32]. For example, Zhao et al. prepared a synergistic catalyst containing Ni0 and Lewis acid sites (Ni2+) on nickel phyllosilicate by controlling the reduction temperature, achieving 97% yield of cyclohexane from phenol HDO at a low temperature of 190 °C [32]. Furthermore, the adjustable active components and rich porosity of silicates also improve the catalytic performance in myriad reactions, such as the high-temperature hydrogenation of dimethyl oxalate, hydrogenolysis of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural, deoxygenation of triglycerides, and methane CO2 reforming reactions [33,34,35,36]. To construct strong metal-SiO2 interactions, various synthesis methods have been developed, such as deposition-precipitation, hydrothermal and ammonia evaporation methods [37,38,39]. However, most of these synthesis methods cannot make the surface metal atoms in nanoparticles fully bond with SiO2 support, resulting in the leaching or aggregation of unstable metal species [10,40]. Therefore, the preparation of metal NPs-inlaid phyllosilicate catalyst with highly dispersed and stable NPs is essential to improve activity and long-term durability.

The selective hydrogenation of maleic anhydride (MA) and the hydrodeoxygenation (HDO) of vanillin are two important and typical liquid-phase reactions [41,42,43,44,45]. On the one hand, the high value-added hydrogenation products of MA are overarching C4 materials in chemical production, such as succinic anhydride (SA), γ-butyrolactone (GBL), 1,4-butanediol (BDO) and tetrahydrofuran (THF), which are extensively utilized in the production of rubber resin, machinery, military equipment, pesticide, textiles, and batteries [42]. Currently, relative harsh reaction conditions (100~240 °C, 0.2~5 MPa H2) are still needed for the hydrogenation of MA, and the main products are SA and GBL when non-noble metals (Cu, Co, Ni) are used as catalysts [41,42]. Among which, nickel-based catalysts display exceptional low-temperature hydrogenation activity, such as the reported reducible metal oxide (CeO2, TiO2, ZrO2) and irreducible metal oxide (Beta, Al2O3, SiO2, SiO2-Al2O3) supported Ni catalysts [42,46,47,48]. Their practical application is hampered by high Ni loadings, large particle sizes, and deactivation at 170–220 °C. On the other hand, the HDO of lignin-derived vanillin into 2-methoxy-4-methylphenol (MMP) is a pivotal route for synthesizing fragrances or pharmaceutical intermediates [44,45]. The burgeoning non-precious metal catalysts have been widely investigated to achieve incredible catalytic conversion at low costs [49,50]. Nevertheless, high temperature (100~200 °C) and hydrogen pressure (1~4 MPa H2) are need [50,51,52,53]. Concurrently, the reaction process is also accompanied by catalyst agglomeration, leaching, or carbon deposition phenomena, resulting in rapid deactivation of the catalyst. Therefore, it is imperative and challenging to develop a highly efficient and durable catalyst for fast and continuous reduction of unsaturated bonds under mild conditions.

Here, we adopt a simple ammonia evaporation-hydrothermal (AEH) approach to synthesize Ni NPs inlaid phyllosilicate catalysts with a porous, hollow structure and highly dispersed Ni NPs (3.3 nm). The hydrothermal process not only enhances the interactions of Ni-SiO2 but also effectively removes the unstable Ni species, which reduces the leaching of metals and prevents the contamination of products by the leaching metal. The selective hydrogenation of MA and HDO of vanillin is used as a probe reaction to evaluate the catalytic activity and the stability of Ni catalysts under the anchoring effect of nickel phyllosilicate (NiPS). The Ni/SiO2-AEH catalyst, with greater phyllosilicate protection, shows higher catalytic activity with 97% yield of SA at 80 °C and 99% yield of MMP at 110 °C. Moreover, the stability of Ni/SiO2-AEH is significantly improved compared to Ni/SiO2-AE with less phyllosilicates, confirming the stabilizing role of phyllosilicates via strong Ni–O–Si bonds.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

All of the chemicals and reagents were purchased without any treatment. Nickel(II) nitrate hexahydrate (Ni(NO3)2·6H2O, ≥98%), ethanol absolute (C2H6O, ≥99.7%), 1,4-dioxane (C4H8O2, ≥99.5%) were purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co. Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Copper(II) nitrate trihydrate (Cu(NO3)2·3H2O, 99%), m-cresol (C7H8O, 99%), vanillin (C8H8O3, 99%), ammonia aqueous solution (NH3·H2O, 25~28%), tetraethyl orthosilicate (C8H20O4Si, 98%), maleic anhydride (C4H2O3, >99%), hexadecyl trimethyl ammonium bromide (C19H42BrN, 99%) were purchased from Shanghai Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China).

2.2. Catalyst Preparation

2.2.1. Synthesis of Ni(OH)2/SiO2-AE or Ni(OH)2/SiO2-AEH Catalysts

Briefly, 0.25 g hexadecyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) was dissolved in a 150 mL beaker containing a mixture of Millipore-purified water (18 mΩ·cm, 30 mL), ethanol (10 mL), and NH3·H2O (2 mL). The mixed solution was stirred at 35 °C for 30 min to obtain a uniform solution. Then, tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS, 1.34 mL) and ethanol (5 mL) mixed solution was added dropwise at a rate of 0.4 mL/min. After stirring for 12 h, the suspension was transferred into a 100 mL beaker containing 20 mL ammonia solution, and 5.5 mL Ni(NO3)2 (0.125 M) solution drop by drop to form a light-green suspension. The mixture was stirred at 35 °C for 12 h and then heated up to 80 °C to evaporate ammonia until the pH value dropped to 7~8. The light-green precipitates were centrifuged, first washed 4 times with ethanol to remove the remaining surfactant CTAB, and then washed twice with water to remove surplus ethanol. Finally, the precipitate was dried at 70 °C in an oven overnight (denoted as Ni(OH)2/SiO2-AE) or transferred into a 100 mL Teflon-lined stainless steel autoclave containing 60 mL water for hydrothermal treatment at 200 °C for 12 h to obtain a hollow material (denoted as Ni(OH)2/SiO2-AEH).

2.2.2. Synthesis of Ni/SiO2-AE or Ni/SiO2-AEH Catalysts

The obtained Ni(OH)2/SiO2-AE or Ni(OH)2/SiO2-AEH were calcined at 550 °C for 6 h with a heating rate of 2 °C/min, then reduced at 500 °C for 3 h in a flow of H2 (50 mL/min). The preparation processes for Cu/SiO2-AE or Cu/SiO2-AEH, NixCu10−x/SiO2-AE or NixCu10−x/SiO2-AEH (x = 8, 5, 2) were the same as Ni/SiO2-AE or Ni/SiO2-AEH with the exception of metal precursors or reduction temperatures. For instance, the Cu/SiO2-AE or Cu/SiO2-AEH catalysts were obtained by reducing CuO/SiO2-AE or CuO/SiO2-AEH at 250 °C for 3 h in a flow of H2. Other nickel-based catalysts shared the same reduction conditions as Ni/SiO2-AEH. The theoretical loadings of all the above catalysts were 10 wt%.

2.2.3. Synthesis of Ni/SiO2-IM and Cu/SiO2-IM Catalysts

A wet impregnation method was adopted in the synthesis. Typically, 550.6 mg Ni(NO3)2·6H2O was dissolved in 50 mL of deionized water in a 100 mL beaker. After stirring for 30 min, 1 g as-synthesized SiO2 was added to the mixture and heated up to 60 °C in an oil bath to evaporate water. The as-prepared powder was calcined at 550 °C for 6 h and reduced at 500 °C for 3 h with a heating rate of 5 °C/min in H2 atmosphere. Cu/SiO2-IM was synthesized using the same method, except that the metal precursor was replaced with Cu(NO3)2·3H2O and the reduction temperature was reduced to 250 °C.

2.3. Catalyst Characterization

Textual properties of the as-synthesized catalysts were determined by a N2-adsorption and desorption method using a Micromeritics ASAP 2020 HD88 (Micromeritics Instrument Corp., Norcross, GA, USA) system at 77 K. The specific surface areas were calculated by the conventional Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) method, and pore-size distributions were estimated by the density functional theory (DFT) model. The morphologies of materials were obtained from scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images using a Hitachi S-8000 microscope (Hitachi High-Tech Corp., Tokyo, Japan). Transmission electron microscope (TEM) images were recorded by a Hitachi HT-7700 microscope (Hitachi High-Tech Corp., Tokyo, Japan). High-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM), high-angle annular dark field scanning TEM (HAADF-STEM), and scanning transmission electron microscopy energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (STEM-EDX) were implemented on a FEI Tecnai G2 F20 S-TWIN instrument (FEI Company, Hillsboro, OR, USA) operated at 200 kV. The particle size of Ni was measured by JEOL JEM-1400 Plus (JEOL Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). X-ray power diffraction (XRD) patterns were carried out on an Ultima IV X-ray diffractometer (Rigaku Corp., Tokyo, Japan) equipped with Cu Kα radiation (1.54 Å). The scanning range of materials was from 2θ = 10° to 80° with a rate of 10°/min. The surface phyllosilicate structure of the catalyst was investigated by Fourier-transform infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopy on a Nicolet Nexus 470 spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), using the KBr disk method with a spectral range of 400–4000 cm−1. The X-ray photoelectron spectra (XPS) were collected by a Thermo ESCALAB 250XI (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) with an aluminum node (Al 1486.6 eV) X-ray source. The actual loading of metal was determined by inductively coupled plasma-atomic emission spectroscopy (ICP-AES) equipped with a PerkinElmer emission spectrometer (Optima 8000, PerkinElmer, Hopkinton, MA, USA). H2-TPR and H2-TPD were performed on the self-built temperature-programmed adsorption-desorption (Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China) apparatus equipped with a fixed bed reactor and thermal conductivity detector (TCD) at atmospheric pressure. For H2-TPR, 60 mg catalyst was loaded into a U-quartz tube reactor and pretreated in Ar gas (30 mL/min) at 200 °C for 1 h with a heating rate of 5 °C/min. After cooling to 30 °C, the catalyst was heated up to 800 °C at a heating rate of 5 °C/min in 10 vol% H2/Ar mixture with a flow rate of 30 mL/min. For H2-TPD, 80 mg reduced catalyst was pretreated in Ar gas (30 mL/min) at 380 °C for 30 min with a heating rate of 5 °C/min. Afterward, the sample was cooled to 50 °C and 10 vol% H2/Ar mixture (30 mL/min) was fed into the reactor until saturation, after purging with Ar gas for 30 min to remove the weakly physically adsorbed hydrogen. H2-TPD was performed with a heating rate of 5 °C/min to 800 °C. The dispersions of Cu or Ni were measured by N2O pulse titration. Typically, 80 mg unreduced catalyst was pretreated in He mixed gas (30 mL/min) at 380 °C for 30 min. After cooling to 90 °C (50 °C for Cu), 5 vol% N2O/N2 (30 mL/min) mixture was pulsed until the N2O peak reached saturation to ensure complete oxidation of the surface metallic metal. Then, the sample was cooled and followed by H2-TPR. The metal dispersion was calculated as follows:

2.4. Catalyst Evaluation

The hydrogenation of maleic anhydride (MA) was implemented in a high-pressure parallel batch reactor. Typically, MA (2.04 mmol), 1,4-dioxane (2 mL), and 10 mg catalyst were mixed in a batch reactor and purged with H2 four times to eliminate the air in the reactor. Then, the vessel was pressurized to 2 MPa at room temperature and heated up to 80 °C for 2.5 h. After cooling to room temperature, the reaction solution was centrifuged and analyzed with gas chromatography (GC) by using m-cresol as an internal standard. The spent catalyst was washed three times with ethanol and dried in a vacuum oven overnight. The experimental procedure for the hydrodeoxygenation of vanillin is identical to that described above, with the following specific conditions: 10 mg catalyst, 100 mg vanillin, and 2 mL 1,4-dioxane were pressurized with 2 MPa H2 at room temperature, followed by reaction at 110 °C for 2 h.

3. Results and Discussion

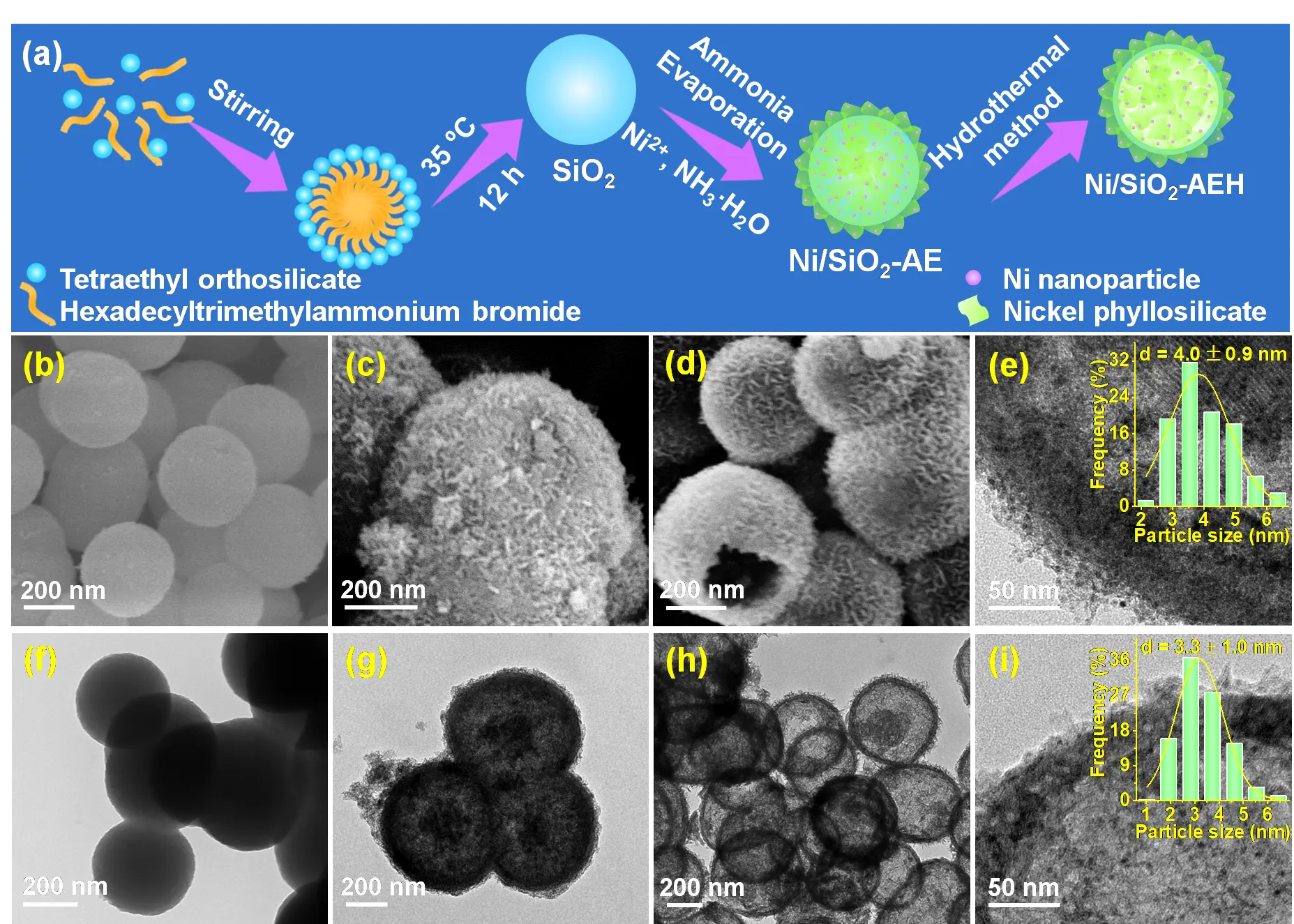

3.1. Synthesis and Characterization of Ni/SiO2-AEH

Ni/SiO2-AEH is synthesized by the following three steps, as schematically illustrated in Figure 1a. In step one, SiO2 is synthesized by Stöber method and has the morphology of a solid sphere with a smooth surface, as illustrated in Figure 1b,f [54]. In step two, Ni/SiO2-AE with uniformly distributed nickel phyllosilicate (NiPS) nanosheets on the SiO2 surface is synthesized via an ammonia evaporation process (Figure 1c,g). In step three, Ni/SiO2-AEH hollow sphere is obtained via a hydrothermal treatment of Ni/SiO2-AE. During the hydrothermal process, the internal mesoporous silicon with lower hydrothermal stability is hydrolyzed while the outer layered NiPS with higher hydrothermal stability is preserved, resulting in the formation of the hollow structure. The hollow structure with well-maintained lamellar NiPS is confirmed by SEM and TEM images, suggesting the retention of NiPS species during the hydrothermal process (Figure 1d,h). The BET surface areas of Ni/SiO2-IM and Ni/SiO2-AE are decreased from 1011 m2/g of as-synthesized SiO2 to 758.5 and 802 m2/g, respectively, since part of the pores are blocked by Ni NPs (Figure S1 and Table S1). Comparing to Ni/SiO2-AE, the BET surface area of Ni/SiO2-AEH (219.6 m2/g) is reduced by 4 times, and the mesopores at 2~4 nm dropped sharply, owing to the hydrolysis of internal unstable mesoporous silicon during the hydrothermal treatment (Figure S1). Furthermore, the mean sizes of Ni nanoparticles (NPs) in Ni/SiO2-AEH is slightly decreased from 4.0 nm in Ni/SiO2-AE to 3.3 nm, which is possibly caused by the partially leaching of Ni species weakly interacting with SiO2 (Figure 1e,i, and Table S2). The actual loading of Ni in Ni/SiO2-AE and Ni/SiO2-AEH is 9.1 and 8.9 wt%, respectively (Table S2). The decreased SiO2 support mass, accompanied by the nearly unchanged Ni loading, further confirms the leaching of some unstable Ni species during the formation of the hollow structure.

Figure 1. (a) A schematic illustration for the preparation of Ni/SiO2-AEH. (b–d) SEM images of (b) SiO2, (c) Ni/SiO2-AE, and (d) Ni/SiO2-AEH; (f–h) the corresponding TEM images. (e,i) HRTEM images and corresponding Ni particle size distributions of (e) Ni/SiO2-AE and (i) Ni/SiO2-AEH.

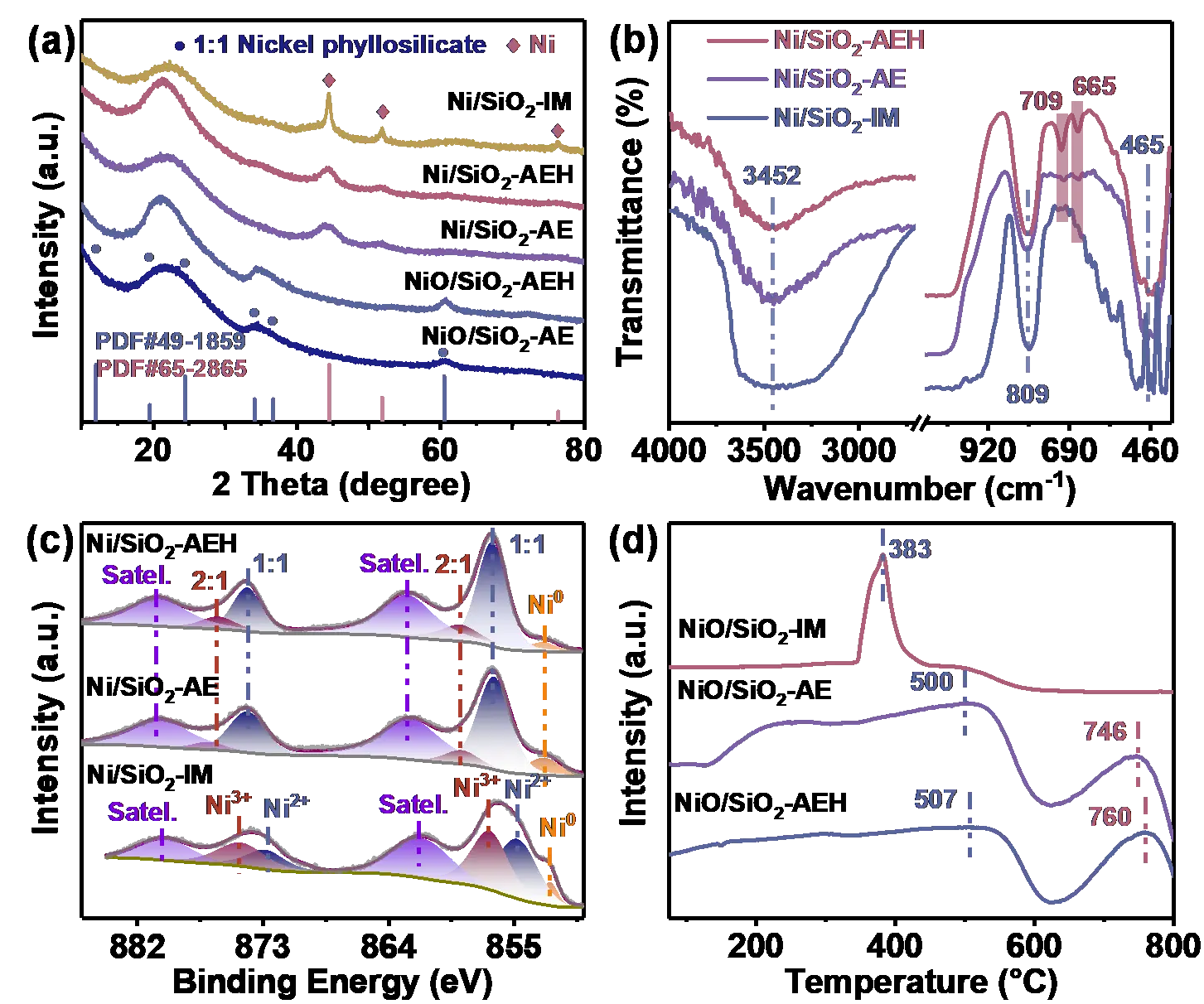

The XRD patterns of all samples show a broad reflection at 2θ = 21~22°, which is assigned to amorphous SiO2 (Figure 2a). The SiO2 diffraction peak in NiO/SiO2-AEH and Ni/SiO2-AEH is intensified and shifted to a lower 2θ value, which may be ascribed to the enhanced ordering of SiO2 by hydrothermal treatment. NiO/SiO2-AE and NiO/SiO2-AEH after calcination at 550 °C display weak and broad diffraction peaks at 34, 36.7, and 60.5°, which belonged to 1:1 NiPS (JCPDS no. 49-1859). The weak Ni characteristic diffraction peaks emerged in reduced Ni/SiO2-AE and Ni/SiO2-AEH indicate that part of NiPS is decomposed and reduced to metallic Ni. However, Ni/SiO2-IM prepared by the impregnation method appears three sharp Ni diffraction peaks at 2θ = 44.5, 51.8 and 76.4° (JCPDS no. 65-2865), suggesting the existence of large Ni NPs. This is consistent with the TEM images with a mean Ni particle size of 14.5 nm (Figure S2). FT-IR spectra are used to characterize the functional groups on the surface of catalysts (Figure 2b). The broad peak at 3452 cm−1 is assigned to the stretching mode of OH groups on the surface of SiO2 [55]. The peaks at 465 and 809 cm−1 are ascribed to the bending vibration of the Si–O–Si bond and stretching vibration of the Si–O bond, respectively [32,55]. Compared to Ni/SiO2-IM, the existence of NiPS in Ni/SiO2-AE and Ni/SiO2-AEH is embodied in two new bands at 665 and 709 cm−1 [35,37]. The chemical state of Ni in Ni/SiO2-AE, Ni/SiO2-AEH, and Ni/SiO2-IM is identified by XPS (Figure 2c). For Ni/SiO2-AE and Ni/SiO2-AEH, two main peaks at 856.6 and 874.1 eV are assigned to the 2p3/2 and 2p1/2 peaks of 1:1 NiPS (Ni3(Si2O5)(OH)4), respectively, and the corresponding satellite peaks are observed at 862.6 and 880.3 eV [35,37,56,57]. The satellite splitting △Esat. (Esatallite peak − E1:1 NiPS) is about 6 eV, which is lower than that of NiO (6.5–7.2 eV), corroborating the presence of a 1:1 NiPS structure [58]. Two weak peaks centered at 858.9 and 876.2 eV could be attributed to 2:1 NiPS (Ni3(Si2O5)2(OH)2). The energy difference between Ni 2p3/2 and Si 2p (△ENi-Si) is used as another indicator further to confirm the formation of 1:1 NiPS [56]. As shown in Table S3, the △ENi-Si values of Ni/SiO2-AE and Ni/SiO2-AEH are both about 753.1 eV, which is well consistent with the value of 1:1 NiPS. Additionally, the O 1s bonding energies at ~531.5 eV also supported the existence of 1:1 NiPS in Ni/SiO2-AE and Ni/SiO2-AEH. Note that the content of 1:1 NiPS in Ni/SiO2-AEH (20.3%) is higher than that of Ni/SiO2-AE (9.7%) and Ni/SiO2-IM (0), indicating that the hydrothermal process strengthens the Ni-SiO2 interaction. For Ni/SiO2-IM catalyst, peaks at 852.4, 854.8, 856.8, and 861.6 eV could be assigned to Ni0, Ni2+, Ni3+ and the satellite peak of Ni2+, respectively [31,59]. In stark contrast to Ni/SiO2-AE and Ni/SiO2-AEH, no NiPS species emerges in Ni/SiO2-IM, which is well matched with the O 1s results (Table S3). The H2-TPR profiles of Ni/SiO2-AE and Ni/SiO2-AEH display a broad reduction peak at 125~625 °C, corresponding to the reduction of NiO with different interaction with support (Figure 2d). Moreover, the higher reduction peak at ~760 °C belongs to the decomposition and reduction of NiPS. For Ni/SiO2-AEH, the content of Ni in low reduction temperature region with weakly interacts with SiO2 is less than that of Ni/SiO2-AE, as a result of the removal of most unstable Ni species in Ni/SiO2-AEH via hydrothermal treatment. A sharp peak at 383 °C is observed in Ni/SiO2-IM, which corresponds to the reduction of large NiO particles. The absence of the NiPS reduction peak further corroborates the lack of NiPS in Ni/SiO2-IM. H2-TPD results show that Ni/SiO2-AEH and Ni/SiO2-AE with small particles (4.0 and 3.3 nm) have stronger ability to activate and dissociate hydrogen than Ni/SiO2-IM with large Ni particles (14.5 nm), as evidenced by the higher H2 desorption intensity of Ni/SiO2-AE and Ni/SiO2-AEH at low-temperature region (65~200 °C) (Figure S3).

Figure 2. Physical characterization of Ni-based catalysts. (a) XRD patterns of NiO/SiO2-AE, NiO/SiO2-AEH, Ni/SiO2-AE, Ni/SiO2-AEH and Ni/SiO2-IM; (b) FT-IR spectra and (c) Ni 2p3/2 XPS spectrum of Ni/SiO2-IM, Ni/SiO2-AE and Ni/SiO2-AEH; (d) H2-TPR profiles of NiO/SiO2-IM, NiO/SiO2-AE and NiO/SiO2-AEH.

3.2. Catalytic Performance of Ni-Based Catalysts

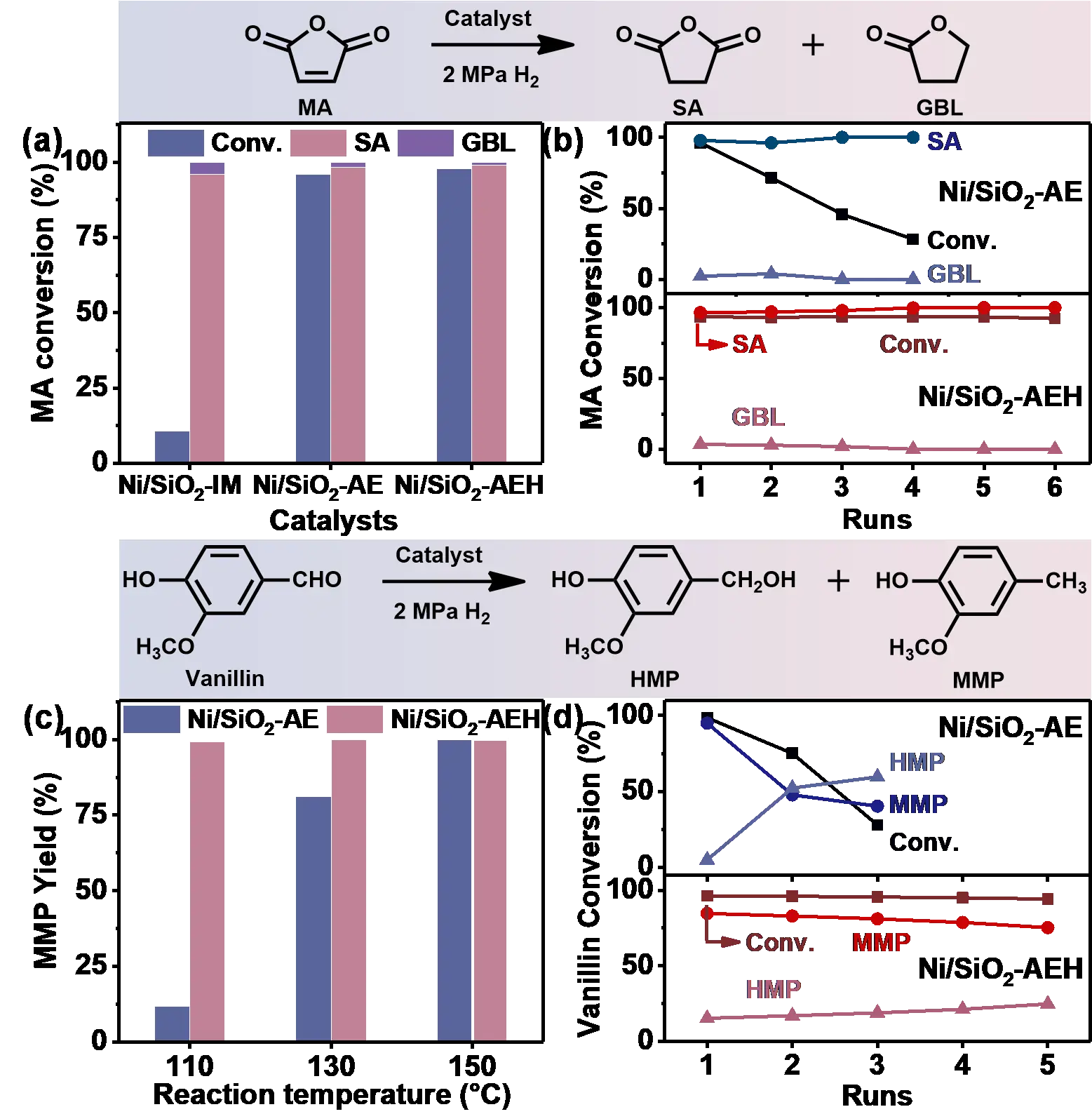

The hydrogenation of MA to SA and HDO of vanillin to MMP are used to assess the catalytic activity and stability of as-synthesized Ni/SiO2-IM, Ni/SiO2-AE, and Ni/SiO2-AEH catalysts (Figure 3). Ni/SiO2-AE and Ni/SiO2-AEH catalysts show superior catalytic activities for MA hydrogenation with >98% MA conversion and >99% SA selectivity, while a much lower conversion of MA is obtained over Ni/SiO2-IM (10.6%) catalyst (Figure 3a). This striking discrepancy in activity can be attributed to the dispersion of Ni NPs (Figure S2). Furthermore, the selectivity of deoxygenated products GBL increases from 0.4% to 45.9% as the reaction temperature rises from 80 to 190 °C, suggesting that higher temperature promotes deeper hydrogenation (Figure S4). Notably, the TOF value of Ni/SiO2-AEH in MA hydrogenation (52 h−1, 80 ℃) was 5.3, 3.1 and 1.6 times higher than that of the reported 31.5%Ni-PS-0.48 (9.8 h−1, 80 ℃) [41], 5%Ni/TiO2 (16.7 h−1, 100 ℃) [60] and 30%NiO2/SiO2 (32.2 h−1, 180 ℃) [61] catalysts, respectively, demonstrating the exceptional hydrogenation activity (Table S4). Although Ni/SiO2-AE shows similar hydrogenation activity to Ni/SiO2-AEH, the stability is much poorer, with only 28% MA conversion remaining after four runs (Figure 3b). On the contrary, Ni/SiO2-AEH exhibits an exceptional cyclic stability with no significant activity loss after six consecutive runs. This enhanced stability is explained by the presence of a greater NiPS species in Ni/SiO2-AEH, which anchor the Ni NPs through strong Ni–O–Si bonds and effectively restrict their growth (Table S3). Moreover, Ni/SiO2-AEH delivers salient catalytic performance for the HDO of vanillin, achieving 99.8% vanillin conversion and 99.2% MMP yield at a low temperature of 110 °C without the use of any noble metal (Figure 3c). These results surpass those of most reported non-noble metal–based catalysts, highlighting the effectiveness of the designed Ni/SiO2-AEH catalyst with NiPS species in promoting hydrodeoxygenation, particularly in the dehydroxylation step of vanillin conversion (Table S5). Vanillin is firstly hydrogenated to 4-(hydroxymethyl)-2-methoxyphenol (HMP) and then converted into the deoxygenated product MMP (Figure S5). The observed accumulation of HMP intermediates demonstrates that the hydrogenolysis of HMP is the rate-limiting step. The stability trend observed for Ni/SiO2-AEH and Ni/SiO2-AE in the HDO reaction aligns with that in MA hydrogenation, further verifying the outstanding stability of the Ni/SiO2-AEH catalyst (Figure 3d).

Figure 3. Catalytic performance for the conversion of MA and vanillin. (a,b) Reaction studies on MA hydrogenation: (a) catalytic evaluation of Ni/SiO2-IM, Ni/SiO2-AE, and Ni/SiO2-AEH catalysts. Reaction conditions: 200 mg MA, 10 mg catalyst, 2 mL dioxane, 80 °C, 2 MPa H2, 2.5 h; (b) recycling test of Ni/SiO2-AE and Ni/SiO2-AEH catalysts. (c,d) The HDO of vanillin over Ni/SiO2-AE and Ni/SiO2-AEH catalysts: (c) the effect of reaction temperature on catalytic activity. Reaction conditions: 10 mg catalyst, 100 mg vanillin, 2 mL dioxane, 2 MPa H2, 2 h; (d) recyclability of Ni/SiO2-AE and Ni/SiO2-AEH catalysts (8 mg catalyst,100 mg vanillin, 2 mL dioxane, 130 ℃, 2 MPa H2, 2 h).

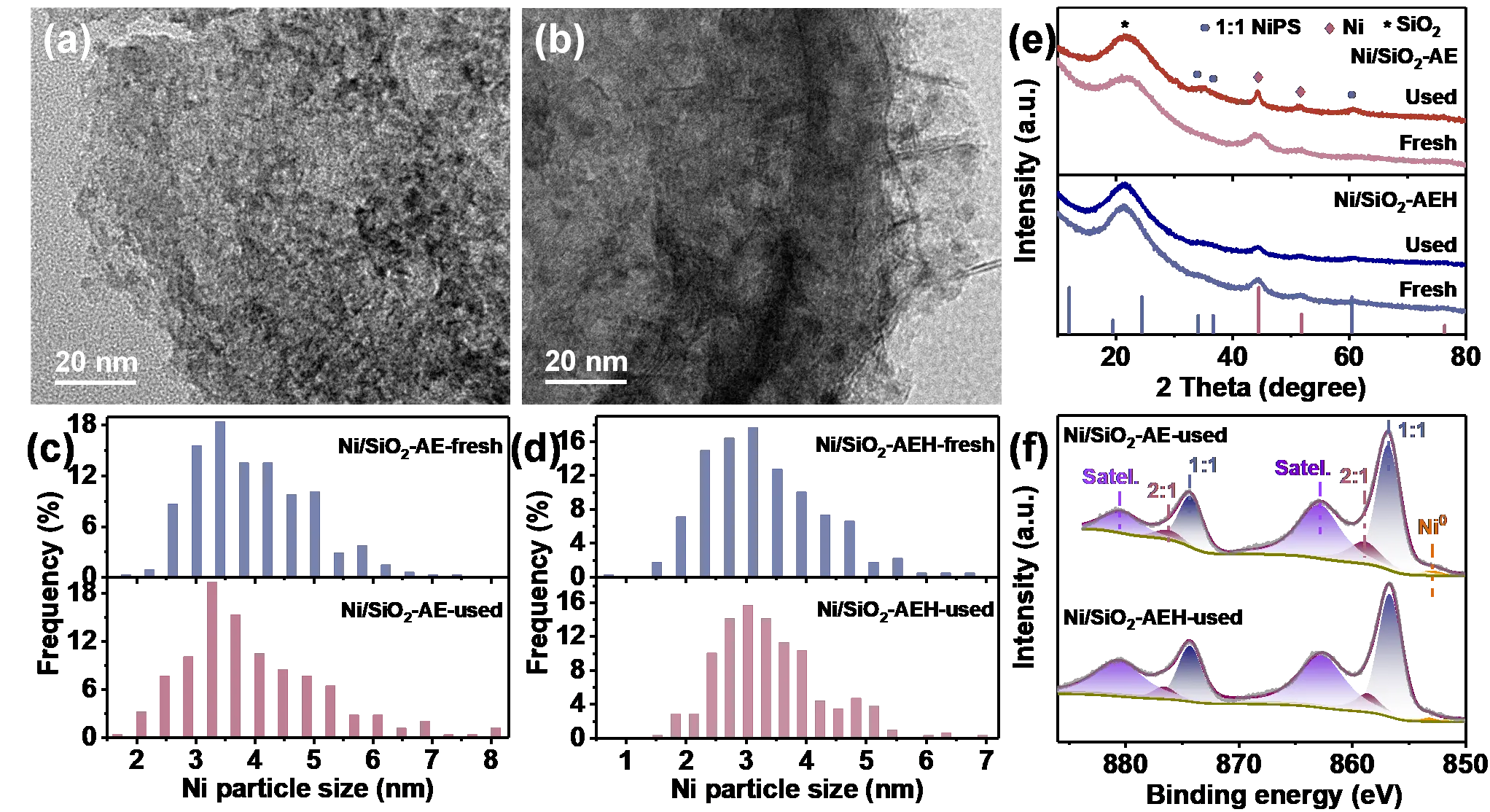

The morphologies and Ni particle size distributions of spent Ni/SiO2-AE and Ni/SiO2-AEH catalysts show no obvious changes in comparison with fresh catalysts (Figure S6 and Figure 4a–d). The XRD patterns and chemical states of Ni without distinguishable change before and after the reaction further confirm that Ni NPs are resistant to agglomeration under the anchoring effect of fibrous NiPS species (Figure 4e,f and Figure 2c). After eliminating deactivation of the Ni/SiO2-AE catalyst due to particle agglomeration, the Ni leaching after multiple cycles is also tested by ICP-OES. It is noteworthy that the leaching rate of Ni in Ni/SiO2-AE after four runs is 50.5%, approximately 23 times higher than that of Ni/SiO2-AEH after six runs (2.2%), which is the main reason for the drastic deactivation of Ni/SiO2-AE (Table S2). To further corroborate the anchoring effect of NiPS on Ni species, the Ni/SiO2-AEH catalyst is calcinated at 800 °C to remove the NiPS phase. Compared to Ni/SiO2-AEH calcinated at 550 °C, the particle size distribution of Ni in Ni/SiO2-AEH-800 is also maintained at 3.6 nm without significant growth (Figure S7a,b). After three reaction cycles, the conversion of MA decreases from 89.3% to 1.8% (Figure S8a). The weakening of the Ni signal in XRD patterns and TEM images verifies that most of the Ni species in Ni/SiO2-AEH-800 catalyst are leached (Figure S7c,d and Figure S8b). Inspired by the above results, the salient stability of Ni/SiO2-AEH is mainly attributed to the anchoring function of NiPS via strong Ni-SiO2 interactions, which prevents the leaching of Ni as well as restricts the migration to form large particles.

Figure 4. Characterization of spent Ni/SiO2-AE and Ni/SiO2-AEH catalysts. (a,b) HRTEM images of spent (a) Ni/SiO2-AE and (b) Ni/SiO2-AEH catalysts; (c,d) The corresponding Ni particle size distributions of fresh and used Ni-based catalysts; (e) XRD patterns and (f) XPS spectra of spent Ni/SiO2-AE and Ni/SiO2-AEH catalysts.

3.3. Catalytic Performance of NixCu10−x-Based Catalysts

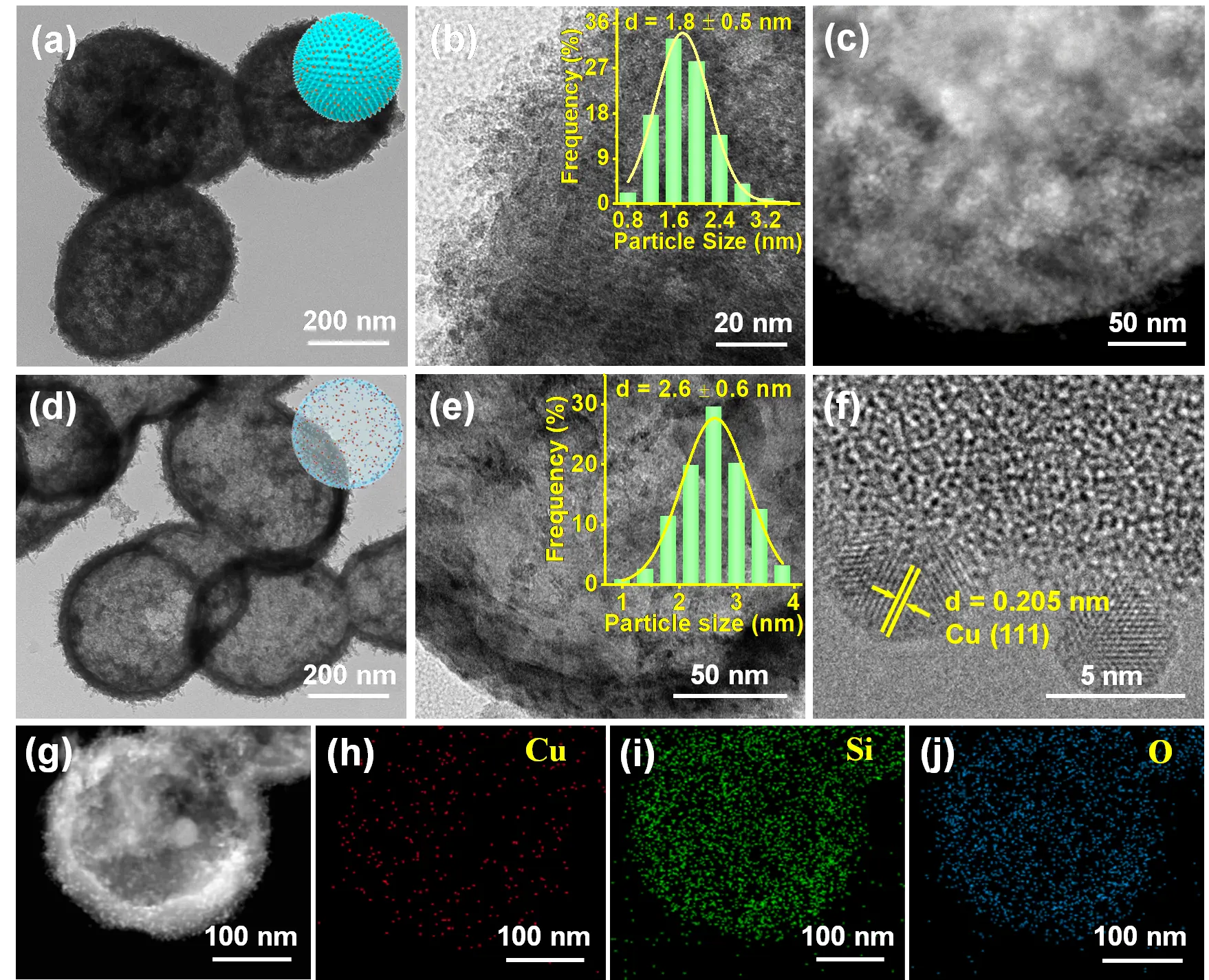

The ammonia evaporation-hydrothermal method can also be used to prepare Cu/SiO2-AE and Cu/SiO2-AEH catalysts with a copper phyllosilicate (CuPS) structure. TEM and HRTEM images show that Cu NPs and CuPS nanotubes are uniformly distributed on the surface of porous solid Cu/SiO2-AE and hollow Cu/SiO2-AEH catalysts, with average particle sizes of approximately 1.8 nm and 2.6 nm, respectively (Figure 5). After loading Ni NPs and undergoing hydrothermal treatment, the BET surface areas of Cu/SiO2-AEH decrease to 443.9 m2/g, while the pore size increases to 6.1 nm, indicating the formation of a hollow structure (Table S6). The sharp metallic Cu diffraction signals together with TEM images indicate the existence of large Cu particles (15.1 nm) in Cu/SiO2-IM (Figure S9). Small weak peaks at 2θ = 43.3 and 36.5° in Cu/SiO2-AE and Cu/SiO2-AEH are attributed to Cu and Cu2O, respectively, while no obvious CuPS (Cu2Si2O5(OH)2) peaks are detectable (Figure S10a). The δOH vibration peak at 670 cm−1 observed in Cu/SiO2-AE and Cu/SiO2-AEH catalysts is the characteristic peak of CuPS, suggesting the retention of CuPS structure (Figure S10b) [20]. H2-TPR profile of CuO/SiO2-AEH shows three prominent peaks at 244, 267, and 310 °C, belonging to the reduction of bulk CuO, small CuO, and CuPS, respectively (Figure S10c). In contrast, the CuO/SiO2-AE shows a strong CuO reduction peak at 242 °C but a tiny peak at a higher temperature (306 °C), suggesting that Cu is well distributed with a lower CuPS content. Combining the XRD and TEM results, the reduction peaks at 227 and 274 °C emerged in CuO/SiO2-IM belong to the reduction of bulk and small CuO particles, respectively. The Cu 2p XPS spectra of Cu/SiO2-AE and Cu/SiO2-AEH present two main peaks at the binding energy of 932.8 and 952.7 eV, which can be assigned to Cu0 or Cu+ (Figure S10d) [40,62].

Figure 5. Electron microscopic characterization of Cu/SiO2-AE and Cu/SiO2-AEH. (a) TEM, (b) HRTEM, and (c) HR-STEM images of Cu/SiO2-AE. (d) TEM and (e,f) HRTEM images of Cu/SiO2-AEH. (g–j) EDS mapping of Cu/SiO2-AEH. Insets in (a) and (d) are the spherical Cu/SiO₂-AE catalyst model and the hollow spherical Cu/SiO₂-AEH catalyst model, respectively, The histogram in (b) and (e) are the corresponding Cu particle size distributions.

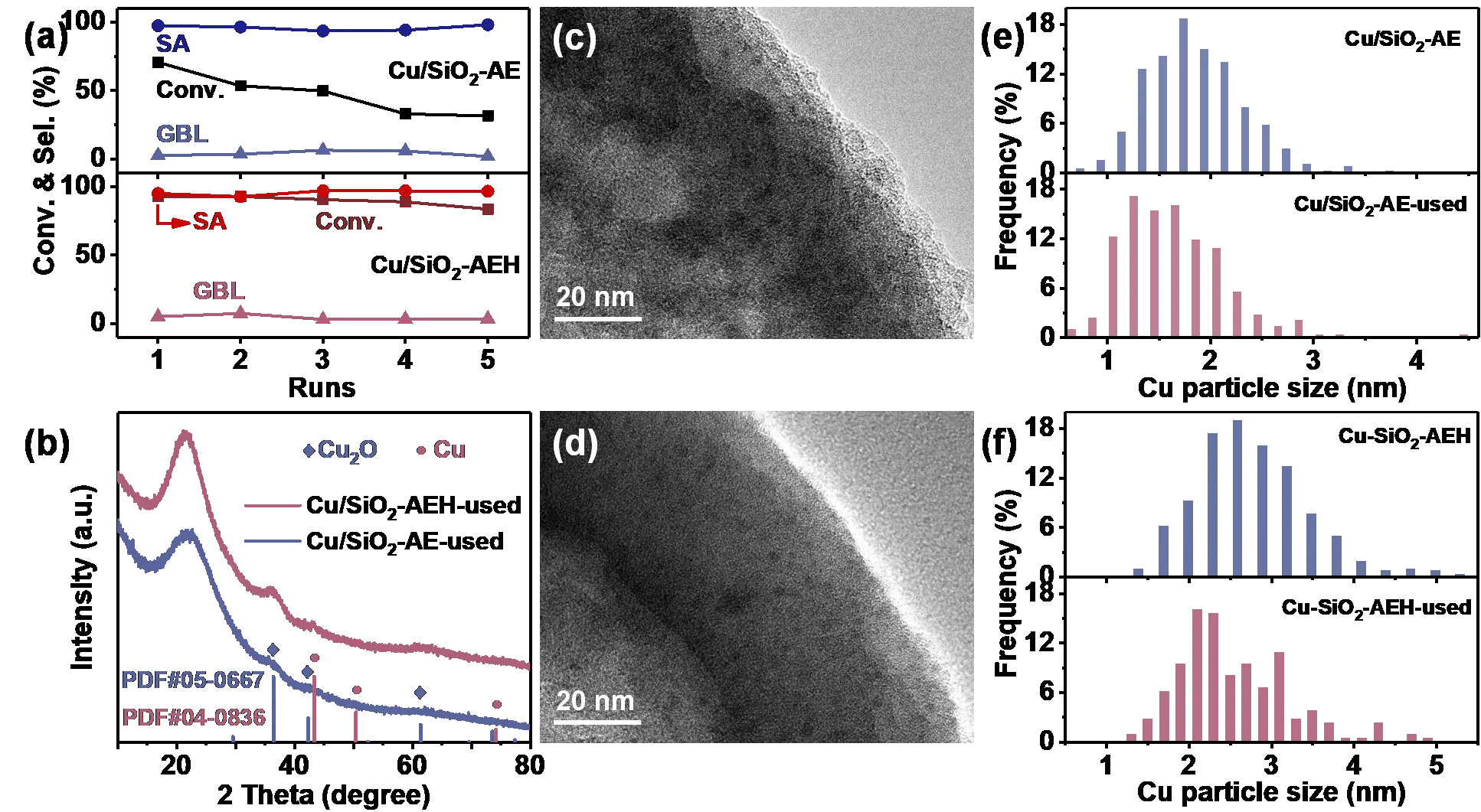

When these Cu-based catalysts are used in MA hydrogenation experiments, similar activity trends to Ni-based catalysts are obtained. The Cu/SiO2-AEH catalyst has excellent catalytic activity with a 96.5% yield of SA and enhanced stability with a slightly decrease in MA conversion (~9%) over five runs (Figure S11 and Figure 6a). The XRD patterns, HRTEM images, and ICP-AES results indicated that the leaching of Cu species is the key reason for the deactivation of Cu/SiO2-AE, underscoring the critical role of phyllosilicate structures in stabilizing the active metal (Figure 6b–f, Figure S12 and Figure S13, and Table S7).

Figure 6. Catalytic performance and characterization of Cu/SiO2-AEH and Cu/SiO2-AE catalysts. (a) Recycling test of Cu/SiO2-AEH and Cu/SiO2-AE catalysts. Reaction conditions: 20 mg catalyst, 100 mg MA, 2 mL dioxane, 150 °C, 2 MPa H2, 3 h; (b) XRD patterns of Cu/SiO2-AE and Cu/SiO2-AEH catalysts after five runs; (c,d) HRTEM images of spent Cu/SiO2-AE (c) and Cu/SiO2-AEH (d) catalysts; (e,f) The corresponding Cu particle size distributions of fresh and used Cu-based catalysts.

Moreover, we extend this preparation method to NiCu bimetallic catalysts. XRD patterns of NixCu10−x/SiO2-AE or NixCu10−x/SiO2-AEH (x = 0, 2, 5, 8, x represents the theoretical loading of Ni) in Figure S14 display weak peaks at 2θ = 44.4 or 43.3°, which belong to metallic Cu in lower Ni loading (x ≤ 5) and metallic Ni in higher Ni loading (x > 5), respectively. The evenly distributed lamellar phyllosilicate species is confirmed by TEM images (Figure S15). When used for the hydrogenation of MA, the conversion of MA increases with the increment of Ni loading over NixCu10−x/SiO2-AE and NixCu10−x/SiO2-AEH catalysts, even at elevated temperature to 200 °C, demonstrating a higher hydrogenation activity of Ni (Figure S16).

4. Conclusions

Ultrafine Ni nanoparticles anchored by NiPS on hollow spherical SiO2 is successfully prepared by ammonia evaporation-hydrothermal method. Compared to Ni/SiO2-AE, the Ni/SiO2-AEH catalyst, with more thermally stable NiPS species, exhibits remarkable hydrogenation and HDO activity, yielding 97% SA and 99% MMP at mild conditions, along with exceptional stability. Controlled experiments and characterization unveil that the deactivation of Ni/SiO2-AE is mainly caused by the leaching of Ni species. In contrast, the outstanding stability of Ni/SiO2-AEH can be attributed to the fact that NiPS suppresses the growth and leaching of Ni NPs via strong Si–O–Ni bonds. The synthetic strategy is also suitable for Cu-based or CuNi bimetallic catalysts with highly dispersed metal particles and phyllosilicates. This highly efficient and stable catalyst is expected to be widely applied in other catalytic fields, such as the hydrogenation of CO2 and biomass upgrading.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be found at: https://www.sciepublish.com/article/pii/852, Figure S1: Textural characterization of SiO2, Ni/SiO2-IM, Ni/SiO2-AE and Ni/SiO2-AEH. (a) Adsorption-desorption isotherms and (b) pore size distributions; Figure S2: Characterization of Ni/SiO2-IM. (a) TEM image and (b) partial enlarged picture. Inset in (b) is the corresponding particle size distribution; Figure S3: H2-TPD profiles of Ni/SiO2-IM, Ni/SiO2-AE and Ni/SiO2-AEH; Figure S4: Catalytic performance of Ni/SiO2-AEH versus reaction temperature (0.2 g MA, 10 mg Ni/SiO2-AEH, 2.5 MPa H2, 3 h); Figure S5: Time courses for the catalytic conversion of vanillin over Ni/SiO2-AEH catalyst. Reaction conditions: 15 mg catalyst,152 mg vanillin, 10 mL dioxane, 100 °C, 2 MPa H2; Figure S6: Morphology characterization of spent Ni/SiO2-AE and Ni/SiO2-AEH catalysts: (a) SEM and (c) TEM images of Ni/SiO2-AE after four runs; (b) SEM and (d) TEM images of Ni/SiO2-AEH after six runs; Figure S7: Characterization of fresh and spent Ni/SiO2-AEH-800 catalyst. (a) TEM image and (b) partial enlarged picture of fresh Ni/SiO2-AEH-800 catalyst; (c) TEM image and (d) partial enlarged picture of Ni/SiO2-AEH-800 catalyst after three runs. Inset in (b) is the corresponding particle size distribution; Figure S8: (a) Recycling test of the Ni/SiO2-AEH-800 catalyst. Reaction condition: 10 mg catalyst, 250 mg MA, 2 mL 1,4-dioxane, 80 °C, 2.5 MPa H2, 3 h. (b) XRD patterns of fresh and spent Ni/SiO2-AEH-800 catalysts; Figure S9: TEM images of Cu/SiO2-IM (a, b). Inset in (b) is the particle size distribution; Figure S10: Physical characterization of Cu-based catalysts. (a) XRD patterns of Cu/SiO2-IM, Cu/SiO2-AE and Cu/SiO2-AEH; (b) FT-IR spectra of Cu/SiO2-IM, Cu/SiO2-AE and Cu/SiO2-AEH catalysts; (c) H2-TPR profiles of CuO/SiO2-IM, CuO/SiO2-AE and CuO/SiO2-AEH and (d) Cu 2p photoelectron spectrum of Cu/SiO2-IM, Cu/SiO2-AE and Cu/SiO2-AEH catalysts; Figure S11: The hydrogenation performance of MA over Cu-based catalysts. (a) Catalytic evaluation of Cu/SiO2, Cu/SiO2-AE and Cu/SiO2-AEH catalysts; Reaction conditions: 20 mg cat., 100 mg MA, 2 mL dioxane, 150 °C, 3 MPa H2, 3 h. (b) Catalytic performance of Cu/SiO2-AEH versus reaction temperature; Figure S12: Electron microscopic characterization of Cu/SiO2-AEH after fifth run. (a) TEM image, (b) HRTEM-HAADF image and (c-e) corresponding HRTEM-STEM mapping of Cu, Si and O; Figure S13: Electron microscopic characterization of Cu/SiO2-AE after fifth run. (a) TEM image, (b) HRTEM-HAADF image and (c-e) corresponding HRTEM-STEM mapping of Cu, Si and O; Figure S14: XRD patterns of (a) Cu8Ni2/SiO2-AE, (b) Cu8Ni2/SiO2-AEH, (c) Cu5Ni5/SiO2-AE, (d) Cu5Ni5/SiO2-AEH, (e) Cu2Ni8/SiO2-AE and (f) Cu2Ni8/SiO2-AEH; Figure S15: TEM images of (a) Cu8Ni2/SiO2-AE; (b) Cu8Ni2/SiO2-AEH; (c). Cu5Ni5/SiO2-AE; (d) Cu5Ni5/SiO2-AEH; (e) Cu2Ni8/SiO2-AE and (f) Cu2Ni8/SiO2-AEH and corresponding enlarged images (a′-f′); Figure S16: Reaction studies on MA hydrogenolysis. (a) Catalytic evaluation of (a′) Cu8Ni2/SiO2-AEH, (b′) Cu5Ni5/SiO2-AEH, (c′) Cu2Ni8/SiO2- AEH, (d′) Ni/SiO2- AEH, (e′) Cu8Ni2/SiO2-AE, (f′) Cu5Ni5/SiO2-AE, (g′) Cu2Ni8/SiO2-AE and (h′) Ni/SiO2-AE. Reaction conditions: 10 mg cat., 200 mg MA, 2 mL dioxane, 80 °C, 2 MPa H2, 2.5 h. (b) Catalytic evaluation of (a′) Cu8Ni2/SiO2-AEH, (b′) Cu5Ni5/SiO2-AEH, (c′) Cu2Ni8/SiO2-AEH and (d′) Ni/SiO2-AEH. Reaction conditions: 10 mg cat., 200 mg MA, 2 ml dioxane, 200 °C, 2 MPa H2, 2.5 h; Table S1: BET surface areas and pore structure parameters of Ni-based catalysts; Table S2: Characterization of active metal Ni in as-synthesized catalysts; Table S3: O 1s binding energy and surface Ni oxides proportion of as-synthesized Ni based catalysts; Table S4: Comparison of the catalytic performance of different reported MA hydrogenation catalysts; Table S5: Comparison of the catalytic performance of different reported vanillin HDO catalysts; Table S6: BET surface areas and pore structure parameters of Cu-based samples; Table S7: Characterization of active metal Cu in obtained catalysts.

Acknowledgments

This project is supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Hubei Province, China (No. 2024AFB205). The authors would like to highly appreciate Yong Wang, Shanjun Mao and Xuefeng Li from Zhejiang University for providing experimental facilities, valuable suggestions, as well as their critical discussions throughout this research.

Author Contributions

Experimental designing, data collection and analysis, writing manuscript, H.N.; supervision, Z.D., C.C. and S.H.; formal analysis, H.N.; investigation, H.N. and Z.D.; editing, S.H.; conceptualization, H.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Ethics Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

Funding

This research was funded by the Natural Science Foundation of Hubei Province, China (No. 2024AFB205).

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

-

Jin Y, Wang P, Mao X, Liu S, Li L, Wang L, et al. A Top-Down Strategy to Realize Surface Reconstruction of Small-Sized Platinum-Based Nanoparticles for Selective Hydrogenation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 17430–17434. DOI:10.1002/anie.202106459 [Google Scholar]

-

Shi H, Su T, Qin Z, Ji H. Role of catalyst surface-active sites in the hydrogenation of α,β-unsaturated aldehyde. Front. Chem. Sci. Eng. 2024, 18, 64. DOI:10.1007/s11705-024-2423-3 [Google Scholar]

-

You P, Zhan S, Ruan P, Qin R, Mo S, Zhang Y, et al. Interfacial oxidized Pd species dominate catalytic hydrogenation of polar unsaturated bonds. Nano Res. 2023, 17, 228–234. DOI:10.1007/s12274-023-5538-9 [Google Scholar]

-

Fan R, Zhang Y, Hu Z, Chen C, Shi T, Zheng L, et al. Synergistic catalysis of cluster and atomic copper induced by copper-silica interface in transfer-hydrogenation. Nano Res. 2021, 14, 4601–4609. DOI:10.1007/s12274-021-3384-1 [Google Scholar]

-

Zhang T, Tian Z, Liu Q. Three-dimensional flower-like nickel phyllosilicates for CO2 methanation: Enhanced catalytic activity and high stability. Sustain. Energy Fuels 2020, 4, 3438–3449. DOI:10.1039/d0se00360c [Google Scholar]

-

Fu B, McCue AJ, Liu Y, Weng S, Song Y, He Y, et al. Highly Selective and Stable Isolated Non-Noble Metal Atom Catalysts for Selective Hydrogenation of Acetylene. ACS Catal. 2021, 12, 607–615. DOI:10.1021/acscatal.1c04758 [Google Scholar]

-

Zhou D, Zhang L, Liu X, Qi H, Liu Q, Yang J, et al. Tuning the coordination environment of single-atom catalyst M-N-C towards selective hydrogenation of functionalized nitroarenes. Nano Res. 2021, 15, 519–527. DOI:10.1007/s12274-021-3511-z [Google Scholar]

-

Liu Z, Wang J, Gao X, Bi Y, Guo C, Tong X. Selectivity-controllable hydrogen transfer reduction of α,β-unsaturated aldehydes over high-entropy catalysts. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2024, 14, 999–1007. DOI:10.1039/d3cy01664a [Google Scholar]

-

Zhou D, Zeng K, Wang L, Tang F. The d-p electron coupling over the unsaturated oxygen coordinated CuCo alloy surface for enhanced N-heteroarenes hydrogenation under mild conditions. J. Energy Chem. 2025, 106, 671–680. DOI:10.1016/j.jechem.2025.03.009 [Google Scholar]

-

Zhao Y, Kong L, Xu Y, Huang H, Yao Y, Zhang J, et al. Deactivation Mechanism of Cu/SiO2 Catalysts in the Synthesis of Ethylene Glycol via Methyl Glycolate Hydrogenation. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2020, 59, 12381–12388. DOI:10.1021/acs.iecr.0c01619 [Google Scholar]

-

Gupta SSR, Kantam ML. Selective hydrogenation of levulinic acid into γ-valerolactone over Cu/Ni hydrotalcite-derived catalyst. Catal. Today 2018, 309, 189–194. DOI:10.1016/j.cattod.2017.08.007 [Google Scholar]

-

Zhao J, He Y, Wang F, Zheng W, Huo C, Liu X, et al. Suppressing Metal Leaching in a Supported Co/SiO2 Catalyst with Effective Protectants in the Hydroformylation Reaction. ACS Catal. 2019, 10, 914–920. DOI:10.1021/acscatal.9b03228 [Google Scholar]

-

Vaschetti VM, Eimer GA, Cánepa AL, Casuscelli SG. Catalytic performance of V-MCM-41 nanocomposites in liquid phase limonene oxidation: Vanadium leaching mitigation. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2021, 311, 110678. DOI:10.1016/j.micromeso.2020.110678 [Google Scholar]

-

Zhang L, Mao J, Li S, Yin J, Sun X, Guo X, et al. Hydrogenation of levulinic acid into gamma-valerolactone over in situ reduced CuAg bimetallic catalyst: Strategy and mechanism of preventing Cu leaching. Appl. Catal. B 2018, 232, 1–10. DOI:10.1016/j.apcatb.2018.03.033 [Google Scholar]

-

van Haasterecht T, Ludding CCI, de Jong KP, Bitter JH. Toward stable nickel catalysts for aqueous phase reforming of biomass-derived feedstock under reducing and alkaline conditions. J. Catal. 2014, 319, 27–35. DOI:10.1016/j.jcat.2014.07.014 [Google Scholar]

-

Dutta S, Yu IKM, Tsang DCW, Ng YH, Ok YS, Sherwood J, et al. Green synthesis of gamma-valerolactone (GVL) through hydrogenation of biomass-derived levulinic acid using non-noble metal catalysts: A critical review. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 372, 992–1006. DOI:10.1016/j.cej.2019.04.199 [Google Scholar]

-

Gebresillase MN, Ho Hong D, Lee JH, Cho EB, Gil Seo J. Direct solvent-free selective hydrogenation of levulinic acid to valeric acid over multi-metal [NixCoyMnzAlw]-doped mesoporous silica catalysts. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 472, 144591. DOI:10.1016/j.cej.2023.144591 [Google Scholar]

-

Hu F, Zhang H, Fu F, Zhu Y, Huang Z, Gan T, et al. Construction of a stable NiCo@ZrO2/N-doped biomass carbon composite with layer-by-layer embedding structure and strong interactions for efficient catalytic hydrogenolysis of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 361, 131667. DOI:10.1016/j.seppur.2025.131667 [Google Scholar]

-

Wang X, Zhang C, Zhang Z, Gai Y, Li Q. Insights into the interfacial effects in Cu-Co/CeOx catalysts on hydrogenolysis of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural to biofuel 2,5-dimethylfuran. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2022, 615, 19–29. DOI:10.1016/j.jcis.2022.01.168 [Google Scholar]

-

Yue H, Zhao Y, Zhao S, Wang B, Ma X, Gong J. A copper-phyllosilicate core-sheath nanoreactor for carbon-oxygen hydrogenolysis reactions. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 2339. DOI:10.1038/ncomms3339 [Google Scholar]

-

Sasaki K, Naohara H, Choi Y, Cai Y, Chen WF, Liu P, et al. Highly stable Pt monolayer on PdAu nanoparticle electrocatalysts for the oxygen reduction reaction. Nat. Commun. 2012, 3, 1115. DOI:10.1038/ncomms2124 [Google Scholar]

-

Farmer JA, Campbell CT. Ceria maintains smaller metal catalyst particles by strong metal-support bonding. Science 2010, 329, 933–936. DOI:10.1126/science.1191778 [Google Scholar]

-

Yu J, Sun X, Tong X, Zhang J, Li J, Li S, et al. Ultra-high thermal stability of sputtering reconstructed Cu-based catalysts. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 7209. DOI:10.1038/s41467-021-27557-1 [Google Scholar]

-

Wang R, Liu H, Wang X, Li X, Gu X, Zheng Z. Plasmon-enhanced furfural hydrogenation catalyzed by stable carbon-coated copper nanoparticles driven from metal–organic frameworks. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2020, 10, 6483–6494. DOI:10.1039/d0cy01162b [Google Scholar]

-

Ren Y, Yang Y, Wei M. Recent Advances on Heterogeneous Non-noble Metal Catalysts toward Selective Hydrogenation Reactions. ACS Catal. 2023, 13, 8902–8924. DOI:10.1021/acscatal.3c01442 [Google Scholar]

-

Chen Z, Zeng X, Li X, Lv Z, Li J, Zhang Y. Strong Metal Phosphide-Phosphate Support Interaction for Enhanced Non-Noble Metal Catalysis. Adv. Mater. 2022, 34, e2106724. DOI:10.1002/adma.202106724 [Google Scholar]

-

van Deelen TW, Hernández Mejía C, de Jong KP. Control of metal-support interactions in heterogeneous catalysts to enhance activity and selectivity. Nat. Catal. 2019, 2, 955–970. DOI:10.1038/s41929-019-0364-x [Google Scholar]

-

Tang C, Liu Y, Xu C, Zhu J, Wei X, Zhou L, et al. Ultrafine Nickel-Nanoparticle-Enabled SiO2 Hierarchical Hollow Spheres for High-Performance Lithium Storage. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2018, 28, 1704561. DOI:10.1002/adfm.201704561 [Google Scholar]

-

Yu X, Williams CT. Recent advances in the applications of mesoporous silica in heterogeneous catalysis. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2022, 12, 5765–5794. DOI:10.1039/d2cy00001f [Google Scholar]

-

Shesterkina AA, Vikanova KV, Zhuravleva VS, Kustov AL, Davshan NA, Mishin IV, et al. A novel catalyst based on nickel phyllosilicate for the selective hydrogenation of unsaturated compounds. Mol. Catal. 2023, 547, 113341. DOI:10.1016/j.mcat.2023.113341 [Google Scholar]

-

Kuhaudomlap S, Mekasuwandumrong O, Praserthdam P, Lee KM, Jones CW, Panpranot J. Influence of Highly Stable Ni2+ Species in Ni Phyllosilicate Catalysts on Selective Hydrogenation of Furfural to Furfuryl Alcohol. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 249–261. DOI:10.1021/acsomega.2c03590 [Google Scholar]

-

Rehman Mu, Wang H, Han Q, Shen Y, Yang L, Lu X, et al. Phyllosilicate-derived Ni/SiO2 catalyst for liquid-phase hydrodeoxygenation of phenol: Synergy of Lewis acid sites and Ni0. Fuel 2024, 378, 132891. DOI:10.1016/j.fuel.2024.132891 [Google Scholar]

-

Xu C, Chen G, Zhao Y, Liu P, Duan X, Gu L, et al. Interfacing with silica boosts the catalysis of copper. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 3367. DOI:10.1038/s41467-018-05757-6 [Google Scholar]

-

Kong X, Zhu Y, Zheng H, Li X, Zhu Y, Li Y-W. Ni Nanoparticles Inlaid Nickel Phyllosilicate as a Metal–Acid Bifunctional Catalyst for Low-Temperature Hydrogenolysis Reactions. ACS Catal. 2015, 5, 5914–5920. DOI:10.1021/acscatal.5b01080 [Google Scholar]

-

Ye RP, Gong W, Sun Z, Sheng Q, Shi X, Wang T, et al. Enhanced stability of Ni/SiO2 catalyst for CO2 methanation: Derived from nickel phyllosilicate with strong metal-support interactions. Energy 2019, 188, 116059. DOI:10.1016/j.energy.2019.116059 [Google Scholar]

-

Praikaew W, Prameswari J, Ratchahat S, Chaiwat W, Sakdaronnarong C, Koo-amornpattana W, et al. Highly active and stable Ni–W/SiO2 catalyst derived from W incorporated on Ni phyllosilicate for deoxygenation of triglycerides into green biofuel range hydrocarbons. Energy Convers. Manage. 2025, 28, 101288. DOI:10.1016/j.ecmx.2025.101288 [Google Scholar]

-

Wang C, Hai X, Bai J, Shi Y, Jing L, Shi H, et al. Elucidating the atomic stacking structure of nickel phyllosilicate catalysts and their consequences on efficient hydrogenation of 1,4-butynediol to 1,4-butanediol. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 488, 150723. DOI:10.1016/j.cej.2024.150723 [Google Scholar]

-

Tsou YJ, To TD, Chiang YC, Lee JF, Kumar R, Chung PW, et al. Hydrophobic Copper Catalysts Derived from Copper Phyllosilicates in the Hydrogenation of Levulinic Acid to γ-Valerolactone. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 54851–54861. DOI:10.1021/acsami.0c17612 [Google Scholar]

-

Bian Z, Kawi S. Preparation, characterization and catalytic application of phyllosilicate: A review. Catal. Today 2020, 339, 3–23. DOI:10.1016/j.cattod.2018.12.030 [Google Scholar]

-

Ding J, Popa T, Tang J, Gasem KAM, Fan M, Zhong Q. Highly selective and stable Cu/SiO2 catalysts prepared with a green method for hydrogenation of diethyl oxalate into ethylene glycol. Appl. Catal. B 2017, 209, 530–542. DOI:10.1016/j.apcatb.2017.02.072 [Google Scholar]

-

Tan J, Xia X, Cui J, Yan W, Jiang Z, Zhao Y. Efficient Tuning of Surface Nickel Species of the Ni-Phyllosilicate Catalyst for the Hydrogenation of Maleic Anhydride. J. Phys. Chem. C 2019, 123, 9779–9787. DOI:10.1021/acs.jpcc.8b11972 [Google Scholar]

-

Zhao L, Zhao J, Wu T, Zhao M, Yan W, Zhang Y, et al. Synergistic Effect of Oxygen Vacancies and Ni Species on Tuning Selectivity of Ni/ZrO2 Catalyst for Hydrogenation of Maleic Anhydride into Succinic Anhydride and gamma-Butyrolacetone. Nanomaterials 2019, 9, 406–424. DOI:10.3390/nano9030406 [Google Scholar]

-

Lu X, Guo C, Zhang M, Leng L, Horton JH, Wu W, et al. Rational design of palladium single-atoms and clusters supported on silicoaluminophosphate-31 by a photochemical route for chemoselective hydrodeoxygenation of vanillin. Nano Res. 2021, 14, 4347–4355. DOI:10.1007/s12274-021-3857-2 [Google Scholar]

-

Ning H, Chen Y, Wang Z, Mao S, Chen Z, Gong Y, et al. Selective upgrading of biomass-derived benzylic ketones by (formic acid)–Pd/HPC–NH2 system with high efficiency under ambient conditions. Chem 2021, 7, 3069–3084. DOI:10.1016/j.chempr.2021.07.002 [Google Scholar]

-

Tian S, Wang Z, Gong W, Chen W, Feng Q, Xu Q, et al. Temperature-Controlled Selectivity of Hydrogenation and Hydrodeoxygenation in the Conversion of Biomass Molecule by the Ru1/mpg-C3N4 Catalyst. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 11161–11164. DOI:10.1021/jacs.8b06029 [Google Scholar]

-

Wang X, Liu Q, Chen S, Qian X, Huang Q, Liu X, et al. Engineered nickel phyllosilicate for selective 5-HMF C–O bond hydrogenation under benign conditions. Catal. Today 2024, 441, 114883. DOI:10.1016/j.cattod.2024.114883 [Google Scholar]

-

Liu M, Miao C, Fo Y, Wang W, Ning Y, Chu S, et al. Chelating-agent-free incorporation of isolated Ni single-atoms within BEA zeolite for enhanced biomass hydrogenation. Chin. J. Catal. 2025, 71, 308–318. DOI:10.1016/s1872-2067(24)60272-x [Google Scholar]

-

Zhang J, Mao D, Zhang H, Wu D. Tuning the Ni/TiO2 catalyst structure during preparation for the selective hydrogenation of furfural. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2024, 162, 105629. DOI:10.1016/j.jtice.2024.105629 [Google Scholar]

-

Li M, Deng J, Lan Y, Wang Y. Efficient Catalytic Hydrodeoxygenation of Aromatic Carbonyls over a Nitrogen-Doped Hierarchical Porous Carbon Supported Nickel Catalyst. ChemistrySelect 2017, 2, 8486–8492. DOI:10.1002/slct.201701950 [Google Scholar]

-

Zhang L, Shang N, Gao S, Wang J, Meng T, Du C, et al. Atomically Dispersed Co Catalyst for Efficient Hydrodeoxygenation of Lignin-Derived Species and Hydrogenation of Nitroaromatics. ACS Catal. 2020, 10, 8672–8682. DOI:10.1021/acscatal.0c00239 [Google Scholar]

-

Fan R, Chen C, Han M, Gong W, Zhang H, Zhang Y, et al. Highly Dispersed Copper Nanoparticles Supported on Activated Carbon as an Efficient Catalyst for Selective Reduction of Vanillin. Small 2018, 14, e1801953. DOI:10.1002/smll.201801953 [Google Scholar]

-

Nie R, Yang H, Zhang H, Yu X, Lu X, Zhou D, et al. Mild-temperature hydrodeoxygenation of vanillin over porous nitrogen-doped carbon black supported nickel nanoparticles. Green Chem. 2017, 19, 3126–3134. DOI:10.1039/c7gc00531h [Google Scholar]

-

Yue X, Zhang L, Sun L, Gao S, Gao W, Cheng X, et al. Highly efficient hydrodeoxygenation of lignin-derivatives over Ni-based catalyst. Appl. Catal. B 2021, 293, 120243. DOI:10.1016/j.apcatb.2021.120243 [Google Scholar]

-

Yao D, Wang Y, Li Y, Zhao Y, Lv J, Ma X. A High-Performance Nanoreactor for Carbon–Oxygen Bond Hydrogenation Reactions Achieved by the Morphology of Nanotube-Assembled Hollow Spheres. ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 1218–1226. DOI:10.1021/acscatal.7b03026 [Google Scholar]

-

Wang Q, Zhang Y, Jiang H, Hu T, Meng C. In Situ Generated Ni3Si2O5(OH)4 on Mesoporous Heteroatom-Enriched Carbon Derived from Natural Bamboo Leaves for High-Performance Supercapacitors. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2018, 1, 3396–3409. DOI:10.1021/acsaem.8b00556 [Google Scholar]

-

Li Z, Mo L, Kathiraser Y, Kawi S. Yolk–Satellite–Shell Structured Ni–Yolk@Ni@SiO2 Nanocomposite: Superb Catalyst toward Methane CO2 Reforming Reaction. ACS Catal. 2014, 4, 1526–1536. DOI:10.1021/cs401027p [Google Scholar]

-

Kermarec M, Carriat JY, Burattin P, Che M, Decarreau A. FTIR Identification of the Supported Phases Produced in the Preparation of Silica-Supported Nickel Catalysts. J. Phys. Chem. 1994, 98, 12008–12017. DOI:10.1021/j100097a029 [Google Scholar]

-

Lehmann T, Wolff T, Hamel C, Veit P, Garke B, Seidel-Morgenstern A. Physico-chemical characterization of Ni/MCM-41 synthesized by a template ion exchange approach. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2012, 151, 113–125. DOI:10.1016/j.micromeso.2011.11.006 [Google Scholar]

-

Zhang C, Luo J, Zhou Y, Jiang Q, Liang C. Metal oxide sub-nanoclusters decorated Ni catalyst for selective hydrogenation of adiponitrile to hexamethylenediamine. J. Catal. 2020, 381, 14–25. DOI:10.1016/j.jcat.2019.10.024 [Google Scholar]

-

Torres CC, Alderete JB, Mella C, Pawelec B. Maleic anhydride hydrogenation to succinic anhydride over mesoporous Ni/TiO2 catalysts: Effects of Ni loading and temperature. J. Mol. Catal. A Chem. 2016, 423, 441–448. DOI:10.1016/j.molcata.2016.07.037 [Google Scholar]

-

Gao CG, Zhao YX, Liu DS. Liquid phase hydrogenation of maleic anhydride over nickel catalyst supported on ZrO2–SiO2 composite aerogels. Catal. Lett. 2007, 118, 50–54. DOI:10.1007/s10562-007-9135-4 [Google Scholar]

-

Ma X, Huang G, Sun Z, Liu YY, Wang Y, Wang A. Nanocatalysts Derived from Copper Phyllosilicate for Selective Hydrogenation of Quinoline. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2023, 6, 14756–14766. DOI:10.1021/acsanm.3c02180 [Google Scholar]