Porous Carbon-Based Adsorbents for CO2 Sequestration from Flue Gases: Tuning Porosity, Surface Chemistry, and Metal Impregnation for Sustainable Capture

Received: 05 December 2025 Revised: 07 January 2026 Accepted: 13 January 2026 Published: 20 January 2026

© 2026 The authors. This is an open access article under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

1. Introduction

The issue of global warming is now widely understood to stem from the persistent release of large quantities of greenhouse gases (GHGs) by human activities, including carbon dioxide (CO2), chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), methane (CH4), and nitrous oxide (N2O) [1,2]. Among all the GHGs, CO2 contributes dominantly to global warming [3]. Since the industrial revolution, the atmospheric CO2 concentration has risen dramatically from approximately 280 ppm to over 415 ppm, largely due to fossil fuel combustion and industrial processes [4]. Projections indicate it may reach about 450 ppm by 2035, with energy-related emissions rising to 43.2 billion metric tons, potentially leading to a 2 °C increase in global mean temperature [5]. This trajectory risks severe environmental and economic consequences, including disruptions to ocean chemistry [6]. Therefore, global efforts to mitigate CO2 emissions are critical, with targets aiming for significant reductions after 2030 and net-zero emissions between 2050 and 2060 [7].

More than 80% of the existing CO2 in the atmosphere results from power plants, industrial facilities and transportation [8]. Thus, capturing CO2 before its release into the atmosphere represents a crucial strategy for achieving decarbonization goals. To this end, various methods have been developed to capture CO2, which can be classified into three categories, including pre-combustion, post-combustion and oxy-fuel combustion [9,10]. Among these, post-combustion capture—which separates CO2 from flue gases after fuel combustion—is particularly amenable to integration with existing infrastructure, making it a widely adopted near-term solution [11,12,13].

To date, many technologies have been developed for CO2 capture and sequestration, including absorption, adsorption, membrane separation, micro-algal bio-fixation, and cryogenic fractionation [14,15]. As summarized in Table 1, each method presents distinct trade-offs in cost, selectivity, maturity, and environmental impact. Chemical absorption, for instance, is a mature technology but suffers from high energy penalties for solvent regeneration, equipment corrosion, and environmental concerns [16,17,18,19]. Membrane and cryogenic processes often face challenges related to cost, energy intensity, or effectiveness at low CO2 concentrations [20,21]. In this context, adsorption has gained considerable attention as a promising solid-phase capture technology. It operates based on the adhesion of CO2 molecules onto a solid adsorbent surface via physical or chemical interactions, offering advantages such as lower energy consumption, reduced corrosiveness, and easier regeneration [22,23,24].

Table 1. A comparison of post-combustion CO2 capture methods based on some key indexes.

|

Key Indexes |

Capital/Operational Cost |

Selectivity |

Recovery |

Reliability |

Maturity |

Environ. Friendliness |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Absorption |

High/high |

Low-moderate |

High (>90%) |

Low (corrosion, solvent losses) |

High |

No (absorbent emission) |

|

Adsorption |

Moderate/moderate |

High (specified adsorbent) |

High (>90%) |

High |

Moderate |

Very environmental- friendly |

|

Membrane |

High/moderate |

High |

Low-high (depending on the used membrane) |

Moderate |

Low |

Relying on the type of membranes |

|

Cryogenic |

High/high |

Low |

Low |

High |

Low |

Moderate |

|

Bio-fixation |

Low/high |

High |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Environmental-friendly |

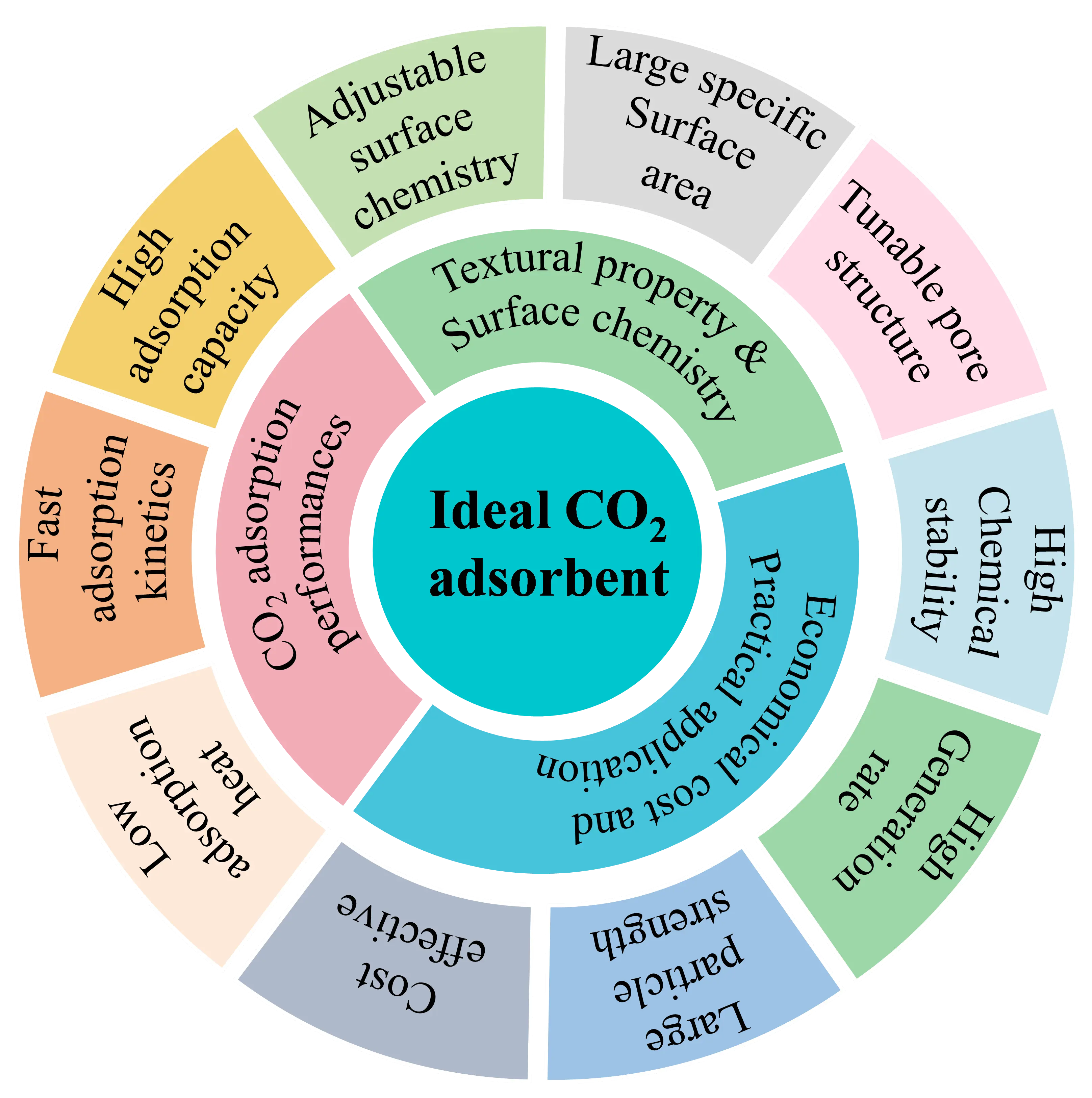

The performance of adsorbents is largely governed by their textural properties (e.g., surface area, pore volume, pore size) and surface chemistry [25]. Consequently, porous materials with high surface areas and tunable pore structures are intensively investigated. Various adsorbents, including metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) [26], zeolites [27], oxide-based adsorbents [20], porous organic polymers (POPs) [28], porous polymer foams [29], and porous carbons derived from various precursors [8,16,30,31]. Numerous studies have been conducted primarily on the development of highly efficient adsorbents in terms of the adsorption capacity, energy efficiency/consumption, CO2 recovery, operating conditions and costs.

Among these solid adsorbents, porous carbons attracted the most attention as the adsorbents for CO2 capture [29], because they possess tunable pore structure and adjustable surface chemistry features that are suitable for CO2 adsorption at both low and high pressures [32]. Usually, the adsorption of CO2 by porous materials is mainly determined by the inherent properties of adsorbents, including the specific surface area (SSA), pore volume and size, and surface functional groups. Among these factors, the pore size is the key factor. It is recognized that porous materials rich in micropores or micro-mesopores are suitable for capturing CO2 at either low- or high-pressures [33,34], respectively. Of course, the adsorption performance will be affected by the operating conditions. Compared with other adsorbents, porous carbons (mainly embodied as activated carbons) possess almost all the desired characteristics of an ideal CO2 adsorbent, as illustrated in Figure 1. Furthermore, porous carbons have excellent water resistance, ensuring them a stable CO2 adsorption performance under high humidity flue gas conditions, so that they can meet the requirements of practical applications. Accordingly, porous carbons become the most popular and effective CO2 adsorbent [35].

A few reviews have been published focusing on the utilization of porous carbons for CO2 removal. These reviews provide a comprehensive overview of the existing porous carbons employed in CO2 capture, including the preparation of porous carbon materials, the summaries of adsorption performance and the effects of operating condition factors [10,28,29]. These reviews are mostly biased towards the narrative and conclusive; none of them focus on the strategies for enhancing the adsorption capability of CO2 capture in detail. For the researchers, understanding and mastering the strategies of how the modified porous carbons can enhance the CO2 adsorption performance will be beneficial to the development of effective porous carbons for CO2 capture. It is believed that a comprehensive and up-to-date review summarizing the recent strategies for enhancing the CO2 adsorption performance of porous carbons is necessary, which can not only serve as a useful starting point for getting into one of the most important fields, but also facilitate the intensive research on the rational and efficient design and development of more effective porous carbons for CO2 adsorption. Therefore, the present review aims to provide an overview of efforts to develop effective porous carbons for CO2 adsorption via various strategies. While significant progress has been made in enhancing the gravimetric adsorption capacity of powdered carbons under ideal conditions, their transition to industrial-scale post-combustion capture requires addressing broader challenges, including the evaluation under real flue gas environments, the formation of robust pellets, and the integration with scalable adsorption processes like fixed-bed or circulating fluidized-bed systems [36]. This review starts with a brief introduction to CO2 capture by adsorption. The second and third parts summarize the adsorption mechanism of CO2 combined with the impacts of operation conditions on the CO2 adsorption performance onto porous carbons. In the third section, the strategies to modify porous carbons for enhancing the CO2 adsorption performance were thoroughly reviewed. The limitations, challenges and future prospects in the applications of porous carbons for CO2 adsorption are addressed in the final section.

2. Mechanism of CO2 Adsorption by Porous Carbons

The exceptional CO2 adsorption performance of porous carbon materials (especially activated carbon) fundamentally stems from their unique disordered nanostructure. CO2, possessing a strong quadrupole moment but no dipole moment, interacts with the carbon surface through polar bonds at both ends of its linear structure [29]. As a classic representative of non-graphitized (or “hard”) carbon materials, activated carbon maintains a highly cross-linked microporous framework structure even under extreme temperatures (>2000 °C), thereby resisting graphitization. Modern structural studies utilizing advanced techniques, such as aberration-corrected transmission electron microscopy, reveal that this stability and its derived pore architecture originate from defect-rich sp2 carbon networks. Contemporary models propose that its structure is not merely a simple stacking of minuscule graphene monolayers, but also incorporates non-hexagonal carbon rings (such as pentagons and heptagons) embedded within the matrix. These topological defects introduce persistent curvature, forming a complex three-dimensional network composed of ultramicropores (often slit-like) and defect sites [37]. It is precisely this intricate nanostructure—characterized by high specific surface area, tunable pore geometry, and chemically active defect sites—that underpins the physical and chemical adsorption mechanisms of CO2 on porous carbon materials. The specific mechanisms have been thoroughly elucidated in relevant studies.

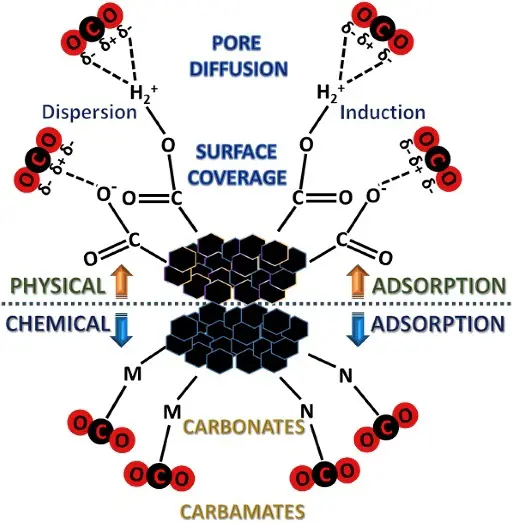

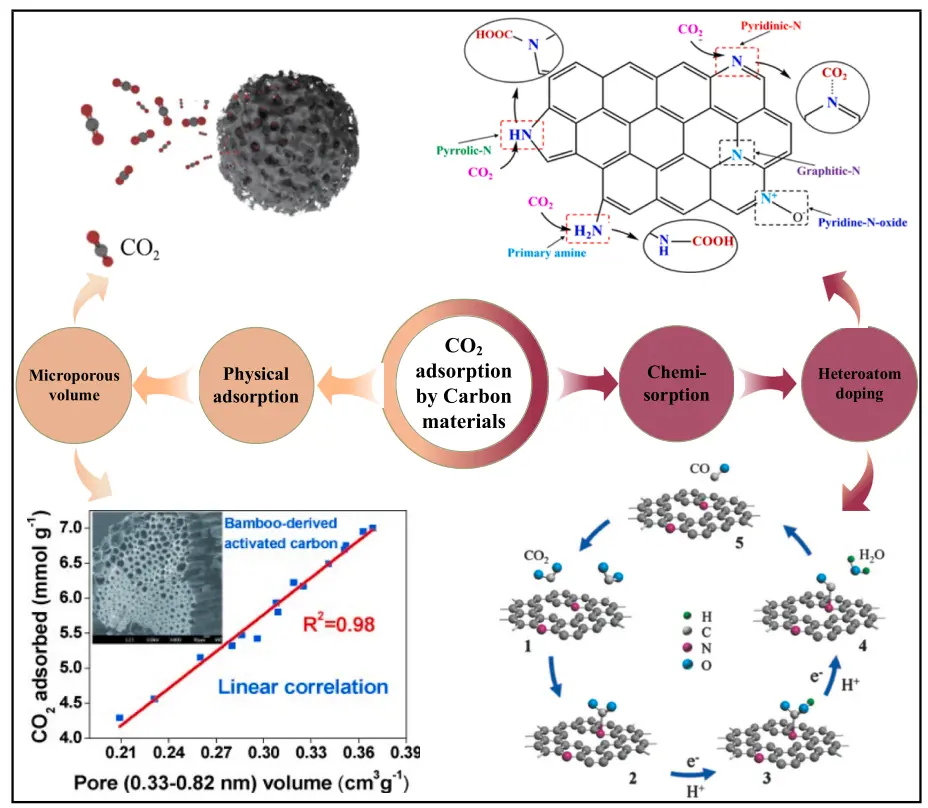

2.1. Physical Adsorption

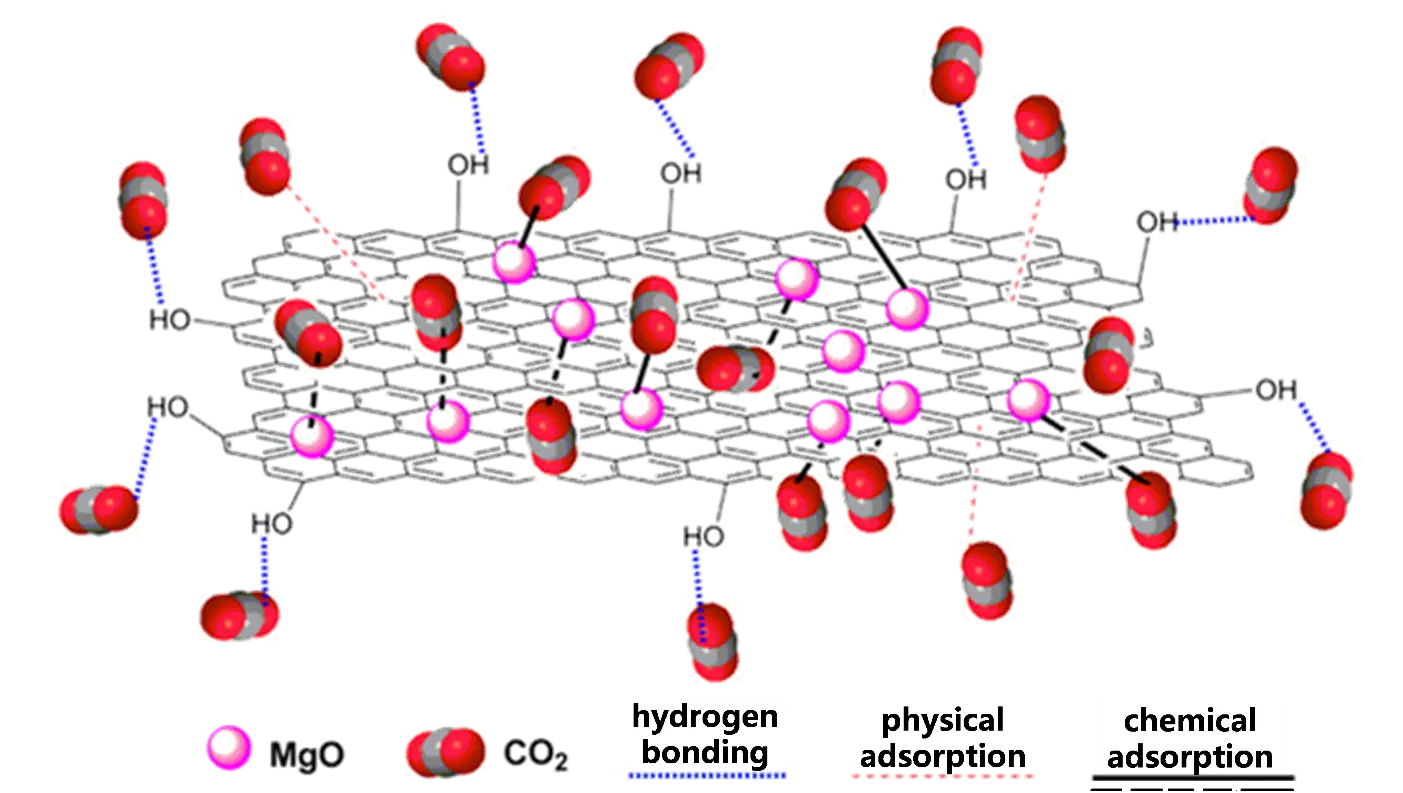

The adsorption mechanism of CO2 onto pristine porous carbon is illustrated in Figure 2. CO2 capture by porous carbon is primarily controlled by physical adsorption or physisorption. In the mechanism of physical adsorption, the CO2 molecules being adsorbed onto the surface of carbon sorbent mainly depends on the van der Waal’s attraction between the CO2 molecule and adsorbent surface, pole-ion and pole-pole interactions between the quadruple of CO2 and the ionic, and the polar sites of the solid adsorbent surface [33], which is verified from the reversible nature of the adsorption process. This adsorption process has a low heat ranging from −25 to −40 kJ/mole on carbon, which is comparable to the sublimation heat [34]. Even though the physisorption of the CO2 molecule on the carbon surface could be temperature-dependent as it approaches equilibrium, namely, lower temperature is beneficial to more CO2 being adsorbed, no activation energy is required for the occurrence of adsorption [38]. This is because of the linear shape and polar bonds on either end of CO2, which can readily interact with the active sites on the carbon surface. In addition, both dispersion and induction contribute to the attraction of CO2 to the carbon surface, correlating with the surface property [39]. Physisorption is recognized as an exothermic reaction with low enthalpy, owing to the weak Van der Waals attraction forces, and it is strongly dependent on the textural properties of the carbon material, such as specific surface area and micropore volume [40], while it is linked with adsorption energy. Beyond the classical Van der Waals forces, the intrinsic molecular properties of CO2 play a pivotal role in physisorption within carbon frameworks. CO2 possesses a significant quadrupole moment, which induces strong electrostatic interactions with the local electric fields generated by surface functional groups or structural defects. In ultramicropores (<0.8 nm), the overlapping potential walls from opposing pore surfaces significantly amplify these quadrupole-field interactions. This explains the enhanced CO2 uptake at low partial pressures, as the energetic affinity of the pore system is dictated not only by pore volume but also by the electrostatic environment of the carbon matrix.

The adsorption performance of physisorption predominantly depends on the textural properties of carbon, facilitated by the intermolecular forces between activated carbon and CO2. Porous carbon with a well-developed pore structure is crucial for CO2 adsorption, and the primary texture parameters include specific surface area, pore volume, pore size, and its distribution, which determine the adsorption capacity of CO2. Recent studies further emphasize the importance of hierarchical porous architectures derived from biomass waste for high-performance CO2 capture [41]. Dai et al. [42] prepared rice husk derived porous carbon using KOH activation, having a specific surface area of 1496 m2/g, total pore and micropore volume of 0.786 cm3/g and 0.447 cm3/g. This porous carbon exhibited CO2 adsorption capacity of 5.83 mmol/g at 273 K and 1 bar and good CO2/N2 selectivity of 9.5. Deng et al. [43] fabricated bamboo derived porous carbon by KOH corrosion activation, which was rich in a lot of ordered micropores. The study disclosed that a perfect linear relationship existed between the pore size and CO2 adsorption capacity, and the narrow micropores with a diameter of 0.55 nm were identified as the primary pores for CO2 adsorption, exhibiting an adsorption capacity of 7.0 mmol/g. Silvestre-Albero et al. [44] investigated CO2 adsorption onto carbon molecular sieves, and confirmed that CO2 adsorption is not only related to the specific surface area, but is also strongly correlated with the micropore volume. Particularly, the developed, uniform and narrow micropores are the key to CO2 adsorption. The significance of micropores of carbon materials in CO2 adsorption was also validated by other studies [45,46,47,48].

Besides the textural properties, the chemical nature of carbon materials also plays a key role in CO2 adsorption. The chemical nature can be defined by the heteroatoms present in their matrix, such as nitrogen, hydrogen, oxygen, phosphorus, and sulfur. These heteroatoms can originate either from the inherent compositions of the carbon precursor or the activation process introduced by the activating agent [50]. Specifically, the adsorption capacity and selectivity towards CO2 depend on the surface functional groups formed by these heteroatoms and the delocalized electrons of the carbon structure. Detailed experimental and DFT studies have shown that the CO2 adsorption capacity of N-doped carbons is governed by a threshold effect: at high nitrogen content, pyridinic-N (N-6) enhances localized polarity, whereas at low doping levels, pyrrolic-N (N-5) improves adsorption through conjugation effects [51]. Furthermore, studies combining experimental data with DFT calculations have recently unveiled the critical role of specific topological defects; for example, pentagonal topological defects were shown to work synergistically with N/O co-doping to enhance CO2 adsorption by regulating the electronic distribution and promoting electron transfer on the biochar surface [52]. Among these heteroatoms, nitrogen (N) is the most popular heteroatom that is incorporated into the carbon matrix to improve the adsorption capacity and selectivity of CO2 adsorption [29,53]. Recent DFT studies on Fe-N co-doped biochar have further demonstrated that the synergy between Fe and N generates Fe-N active sites, which enhance surface alkalinity and significantly boost CO2 capture [54]. The introduction of nitrogenous groups like amide, nitrile, amines and others can increase the physisorption of CO2 on carbon surface [29,48], due to the strong interaction between the acidic CO2 and basic nitrogenous surface functional groups. The basic character of carbon is closely related to the resonation of π electrons present in carbon aromatic rings, which attract protons and nitrogen-containing groups. On the contrary, the acidic character of carbon is tightly linked with the presence of oxygen-containing groups, and the acidity will be greater when the oxygen concentration on the carbon surface increases.

2.2. Chemical Adsorption

In chemical adsorption of chemisorption, an acidic CO2 molecule is attached to the active site on the carbon surface via covalent bonding. The chemisorption of CO2 onto adsorbents can be evaluated by characterizing the used carbon after adsorption and by identifying the heat of adsorption. During the adsorption process, the CO2 gas undergoes a covalent chemical reaction to connect with the specific active sites on carbon, with a substantially high adsorption heat that is almost equal to the heat of reaction [34]. Compared with physisorption, chemisorption has a much higher heat of adsorption, ranging from 40–400 kJ/mol [55], owing to its strong chemical bond. Moreover, CO2 is adsorbed on the carbon surface and chemically bonded to form carbonates. Generally, CO2 chemisorption is irreversible. The formed carbonates usually include bicarbonate, bidentate carbonate, and monodentate carbonate, which correspond to weak, medium, and strong adsorption basic sites [47].

Chemical adsorption of CO2 by porous carbon is generally accomplished through doping various heteroatoms onto porous carbons. The most frequently adopted methods include doping nitrogen, comprising urea, melamine, p-Phenylenediamine, polyethyleneimine, polyaniline, etc. Nitrogen-containing functional groups can lead to chemisorption via the formation of a zwitterion or a carbamate, and the hydration of CO2 to form bicarbonate [38]. Tan et al. [39] investigated the adsorption of CO2 on nitrogen-doped porous carbon prepared from licorice residue and urea, revealing a synergistic effect between the nitrogen content and the activated carbon’s structure on CO2 adsorption performance. They found that nitrogen content contributed remarkably to CO2 adsorption, attributed to the acid-base reaction between CO2 and doped nitrogen atoms. CO2 is recognized as a weak Lewis acidic gas that can react with doped nitrogen-containing groups that act as Lewis bases due to their negatively charged and electron-donating behavior [42]. The chemical interaction between N-containing functional groups and CO2 involves more than simple acid-base neutralization. For amine-functionalized or N-doped carbons, the reaction typically follows a zwitterion mechanism. In the absence of moisture, a CO2 molecule undergoes nucleophilic attack by the lone pair of electrons on the nitrogen atom to form a zwitterion intermediate, which subsequently undergoes proton transfer to form a stable carbamate: 2RNH2 + CO2 ↔ RNHCOO− + RNH3+. Under humid conditions, the mechanism shifts towards a bicarbonate pathway, where water acts as a proton mediator, theoretically doubling the stoichiometric capture capacity per nitrogen site: RNH2 + CO2 + H2O ↔ RNH3+ + HCO3−. In addition, Wang et al. [44] examined the adsorption performance of CO2 on a series of nitrogen-doped porous carbon, and an enhanced CO2 adsorption capacity was observed. The nitrogen species, such as pyridine-N, pyrrole-/pyridine-N, graphitic-N, pyridine-N-oxide and primary/secondary amines, can react with CO2, forming graphitic-N, carboxyl groups and heterocyclic structures (pyrrolic-N), thus facilitating the CO2 adsorption. This is corroborated by a recent study on N, S co-doped porous carbon derived from coconut shell, where the presence of pyridinic-N and pyrrolic-N significantly contributed to a high CO2 uptake of 4.38 mmol/g at 25 °C, demonstrating the critical role of these N-functionalities in enhancing surface basicity and Lewis acid-base interactions with CO2 [56]. In addition to nitrogen, other atoms, for example, oxygen, sulfur, boron, phosphorus, etc., can be doped and facilitate the chemical adsorption of CO2 on heteroatom-doped porous carbon materials.

Apart from heteroatom doping, metal impregnation on carbon has been demonstrated to have excellent stability and prominent adsorption enhancement, especially via chemisorption. Numerous studies have clearly proved that the impregnation of metal ion into biomass derived porous carbon can integrate their multiple advantages effectively, leading to a much-enhanced CO2 adsorption performance [45,46,47]. The presence of metal ions will result in the formation of bidentate and monodentate carbonates owing to the bonding between CO2 and metal ions (Mg2+) and/or O2− [48]. In addition, the strength of basic sites of carbons is proportional to the amount of coordinated electronegative metal ions, which can be boosted by employing metal-impregnated carbon with a high specific surface area, providing more space for O2− sites [50]. More importantly, the impregnation of metal ions can greatly improve the adsorption capacity of CO2 under humidity. Generally speaking, the presence of H2O will significantly inhibit the adsorption of CO2 onto carbon [57]. While for metal-impregnated carbons, for example, MgO-based and Mg(OH)2-based carbons are capable of generating MgCO3 in the presence of H2O [58], thereby improving the CO2 adsorption capacity. The water vapor will serve as a channel for enhanced chemisorption interactions between MgO and CO2, producing CO32− and H+ ions when water surrounds MgO. Besides magnesium ions, other metal ions can be impregnated into carbon to enhance the chemisorption of CO2 onto carbon, which will be discussed in detail later.

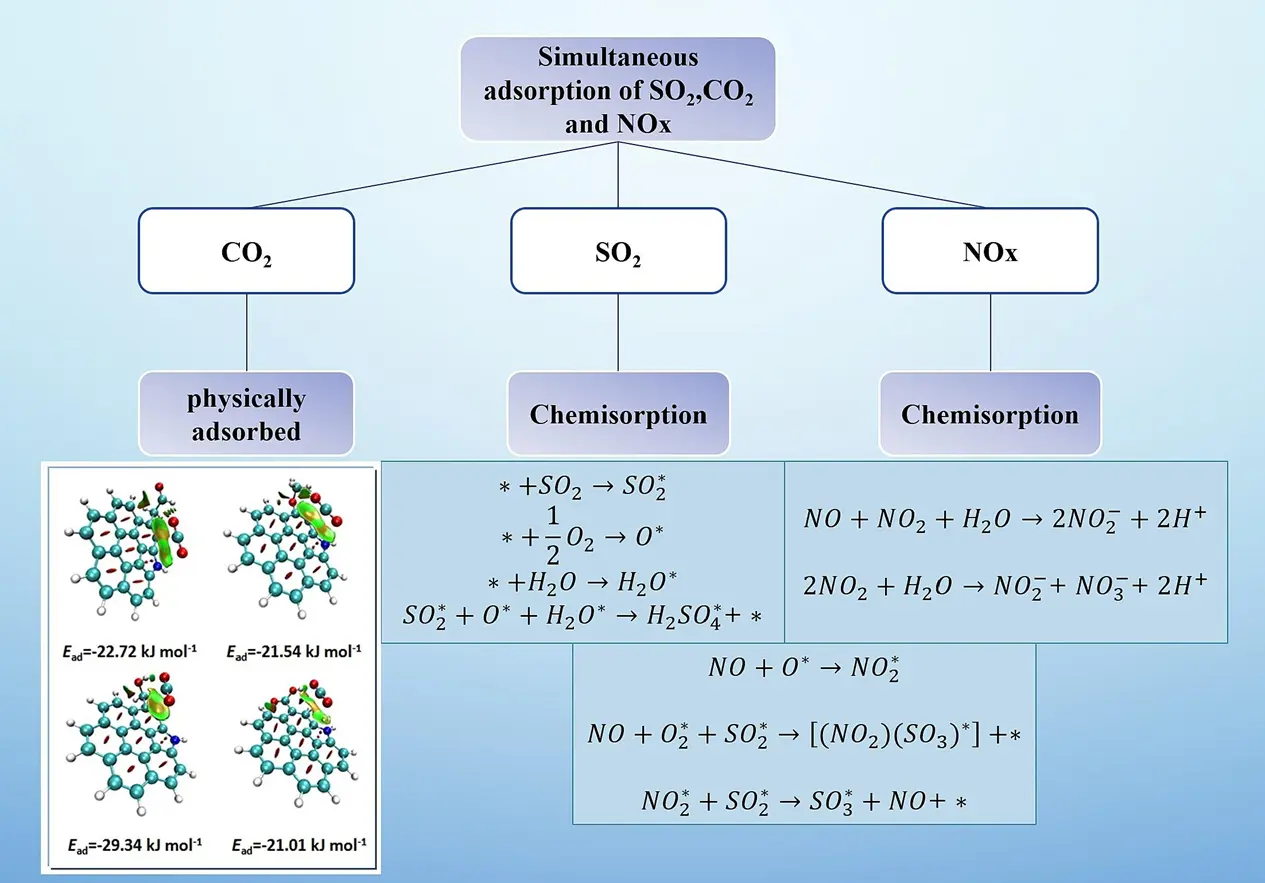

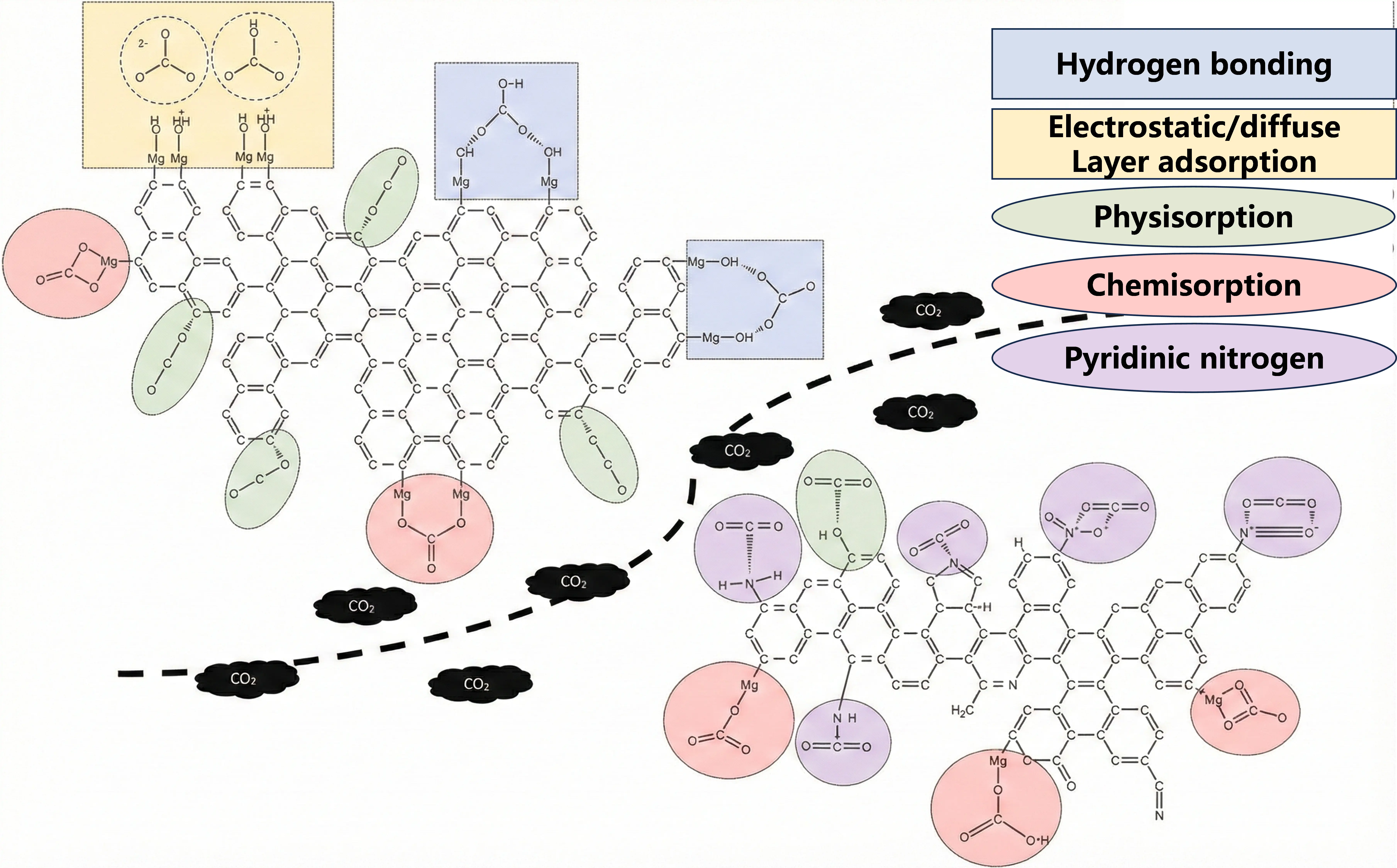

The adsorption mechanism of CO2 onto carbon materials can be summarized in Figure 3, involving both the physical adsorption promoted by the porous structures and chemisorption induced by doping heteroatoms or impregnating metal ions. Carbon materials will continue to undergo extensive investigation in CO2 adsorption; some challenges, including low adsorption efficiency, high operation expenses and weak moisture/impurities tolerance, should be addressed. Hence, elucidating the adsorption mechanism is very crucial to the theoretical exploration and industrial applicability of carbon materials for CO2 capture.

3. Impacts of Operation Conditions on CO2 Adsorption

The CO2 capture in actual applications is carried out in various kinds of complicated conditions, and the operating parameters will inevitably influence both the capacity/extent and rate of CO2 adsorption. The typical operating parameters include temperature, partial pressure of CO2, water vapor, and impure gases (NOx, SOx, H2S, etc.). It is necessary to review and clarify the impacts of CO2 adsorption on porous carbons, for developing appropriate adsorbents that can effectively work under these conditions and still have high adsorption capacity.

3.1. Adsorption Temperature

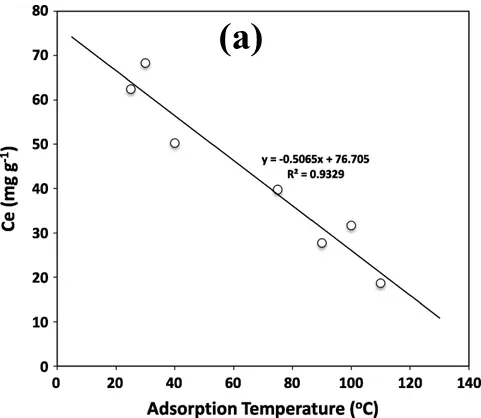

The adsorption temperature exercises an important influence over the adsorption performance from both physical and chemical adsorption [59,60]. The variation of temperature itself possesses a propensity for either negative and positive (sometimes conflicting) effects on individual aspects of CO2 adsorption. On one hand, adsorption is exothermic, so it is predicted that the CO2 adsorption capability increases as the adsorption temperature decreases [61]. On the other hand, CO2 molecules have high kinetic energy at high temperatures, so they can move faster, resulting in less adsorption time on the adsorbent surface, which leads to reduced adsorption capacity. Although the increased energy enables a greater diffusion rate of gaseous molecules, the possibility of CO2 being adsorbed or retained on the carbon surface by fixed energy adsorption sites is decreased. As shown in Figure 4a, the CO2 adsorption capability of sugarcane bagasse derived carbon decreased linearly (R2 = 0.93) with the increase of temperature, which confirms a strong negative correlation between CO2 adsorption capacity and adsorption temperature.

3.2. Adsorption Pressure

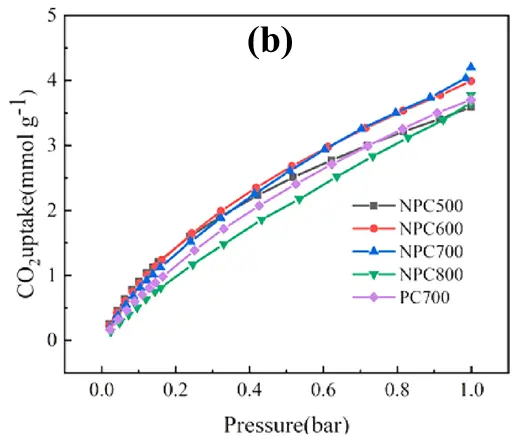

There is a considerable demand for more studies on the adsorption capacities of carbon materials at higher pressures. Numerous researches have proved that the operating pressure plays a significant effect, and CO2 adsorption capacity increases with the elevation of CO2 pressure [63,64,65]. As shown in Figure 4b, the porous carbon and nitrogen-doped porous carbon all exhibited enhanced CO2 adsorption capacity with the elevation of pressure ranging from 0 to 1.0 bar, and the maximal CO2 adsorption capacities of 3.59–4.20 mmol/g were obtained at 25 °C and 1.0 bar [62]. When a gas molecule is adsorbed onto a solid surface, the global volume of the adsorbent will decrease. According to Le Chatelier’s principle, the equilibrium state will shift toward a new state when a stress (for example, a change in pressure) is applied on a system, and the new state will counteract the applied stress. To counter the increase in pressure, the number of gas molecules in the system tends to be reduced, thereby the adsorption capacity of CO2 on the adsorbent will increase [66,67].

Furthermore, the investigation on the adsorption capacity at varied pressures can gain insights into the role of each materials property of porous carbons on CO2 capture capacity. The previous studies demonstrated that CO2 capture capacity at low pressure of 0.1–0.2 bar was more correlated with the practical post-combustion application [47,55], which was consistent with the partial pressure of CO2 in flue gas. In fact, the CO2 capacity on porous carbon is determined synergistically by the adsorbent properties (such as textural properties and chemical compositions) and the operating conditions, while their impacts are not independent. To determine the underlying dependent relationships between CO2 adsorption capacity and adsorbent properties and operating conditions, machine learning (ML) methods were recently adopted, which can identify complex nonlinear relationships among multiple influencing factors and interdependent variables. Shang et al. [59] developed robust ML models to predict the CO2 adsorption capacity of porous carbon based on the adsorbent properties and adsorption conditions. They found that pressure played a dominant role in determining CO2 adsorption capacity at low pressure (0–0.2 bar), while the relative contribution of pressure declined with increasing pressure. In addition, the textural properties are more vital to CO2 adsorption than chemical composition across different pressure and temperature ranges; the relative importance of ultra-micropores increased with increasing pressure.

3.3. Water Vapor

In actual CO2 capture, water is one of the most frequent impurities in the gas stream, especially, water vapor is ubiquitous in the flue gas and in lots of other CO2-rich industrial gases. H2O is usually the third most abundant component in flue gases after N2 and CO2, followed by O2. The water content in flue gases is 6–18% depending on the origin [60], while it is typically 6–7% in biogas [61]. H2O can be strongly adsorbed by many inorganic adsorbents, for it is a polar molecule, so the presence of H2O in the mixture can cause some problems for adsorbents. For example, competitive adsorption will occur between CO2 and H2O, and the adsorption capacity for CO2 will be weakened for the adsorbents that have a higher affinity toward water molecules than CO2 molecules [68,69]. For this reason, a dehumidifying unit was proposed for H2O removal from the feed gas prior to entering the capture unit, such as inserting a layer of a moisture adsorbent material (e.g., alumina, alumina-zeolite) [70,71]. Nevertheless, the dehumidification units will increase the overall capital and operating costs [72,73]. Although carbon adsorbents are hydrophobic, showing fewer issues with water vapor, it is still required to study the humidity effect on carbon adsorbents for CO2 adsorption, given the ubiquitous nature of water in gas streams.

Porous carbons generally exhibit type-I adsorption isotherm for CO2, indicative of their high affinity toward CO2 at low partial pressures [74]. Moreover, they often show low affinity toward water vapor at low relative humidity (RH) with low adsorption capacity, while the water uptake increases dramatically at higher RH levels, which is reflected as the “S”-shape adsorptions corresponding to type-V isotherm [75,76]. It is recognized that water adsorbs first over surface functional groups due to its strong affinity for water, then on top of the chemisorbed water molecules via hydrogen bonding, based on the model proposed by Do and Do [77]. Eventually, water clusters will form on the surface of porous carbons and move into their micropores, as established earlier based on experimental and theoretical results [78,79,80]. Subsequently, the generated water clusters contributed to micropore filling within the adsorbent, potentially occupying the micropores completely, leading to competitive adsorption between the water and the target gas (CO2).

Most investigations on carbon-based adsorbents carried out under subatmospheric pressures reported negative impacts of humidity on CO2 uptake, as a result of the competitive adsorption with water. Duran et al. employed one commercial carbon (Norit R) and two biomass-derived porous carbons for CO2 adsorption from a flue gas stream, and single-component adsorption isotherms of N2, CO2 and H2O were measured to evaluate the selectivity of CO2 to water and nitrogen at 30–70 °C [81]. They found that water was adsorbed preferentially on all the carbon samples compared with CO2, especially at the lowest temperature. When 2 vol% H2O/N2 and 2 vol% H2O/8 vol% CO2/N2 gas mixtures corresponding to 48 and 16% RH at 30 and 50 °C was used, water uptake was hardly affected by CO2. On the contrary, the presence of water reduced CO2 uptake remarkably at the highest RH, and the prehydration of the adsorbents at 30 °C reduced CO2 uptake by as much as 46%. For the biomass-derived porous carbons, their surface functionality is a determining factor for water adsorption in terms of hydrophobicity and hydrophilicity. How the surface hydrophobicity of biochar varies with the feedstock and preparing conditions is controversial based on the reported studies. Some proposed that the hydrophobicity changed with the activation method [82] and the increase of production temperature [83,84,85]. The details are discussed as follows.

Younas et al. [82] investigated the influence of activation method on the competitive adsorption of water vapor and CO2 onto a palm shell derived porous carbon, and both physical activation and chemical activation using 20–50 wt% NaOH solutions were used to prepare porous carbons. They found that the presence of water vapor (20% RH) can reduce CO2 uptake, and the negative effect of humidity was more severe for physically than chemically activated porous carbons, with 45% and 13% declines, respectively. Gray et al. [83] inspected the influences of porosity and hydrophobicity of biochar on water uptake. The biochar was produced from two feedstocks (hazelnut shells and Douglas fir chips) at three production temperatures (370, 500 and 620 °C). The production temperature changed the surface hydrophobicity, and the hydrophobicity decreased with an increase in the production temperature, which can be ascribed to the volatilization and loss of the aliphatic functionality at higher production temperatures. Contrary to the studies by Gray et al., some other works reported opposite results, where the hydrophobicity increased with increasing production temperature. These studies assessed hydrophobicity by measuring atomic ratios such as O/C, H/C and (O+N)/C [86,87] raising the pyrolysis temperature would result in the reduction of both ratios [88], leading to a subsequent increase in hydrophobicity due to the loss of the polar functional groups.

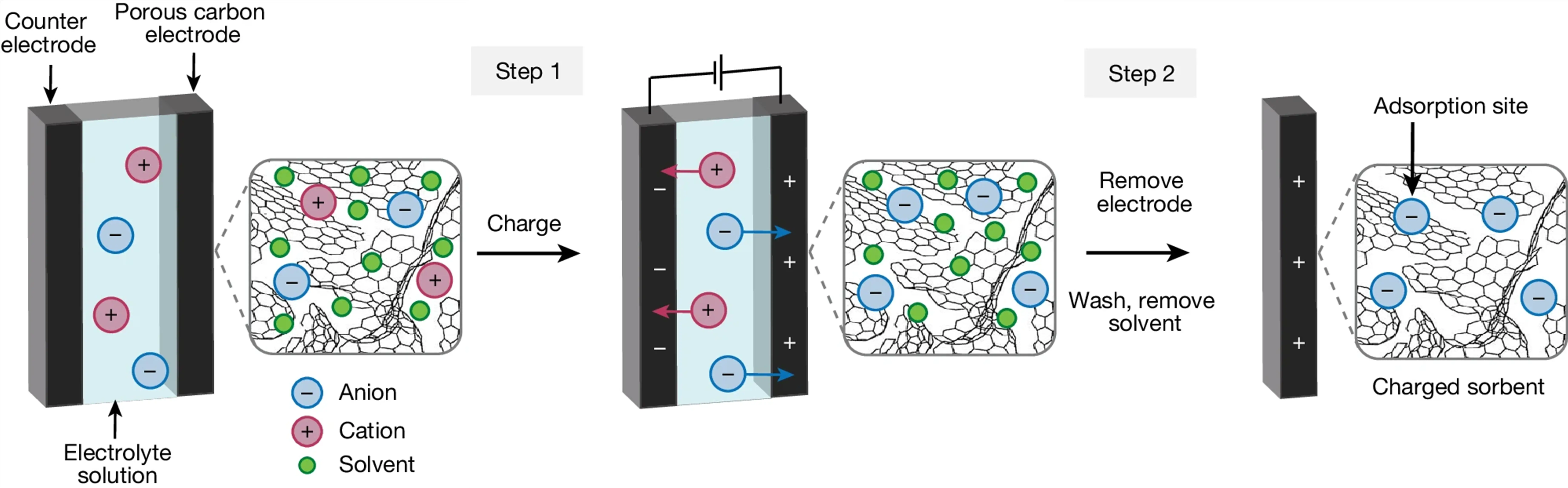

At high pressure, there is an extensive consensus regarding the beneficial effect of water on CO2 adsorption onto carbon adsorbent. Zhou et al. [89] measured CO2 adsorption isotherms of coconut shell derived microporous carbon at 275 K up to 40 bar over prehydrated adsorbents. The moisture content Rw, was defined as the ratio of adsorbed water to carbon. Figure 5a revealed that the moisturized samples had lower CO2 uptake than the dry carbon at low pressure, and their CO2 uptake increased significantly at 15 (20 bar), while the CO2 uptake on dry carbon was almost stable over 15 bar. This was ascribed to the enhanced solubility of CO2 in water at high pressure, resulting in the formation of CO2 hydrate. Figure 5b demonstrates that the inflection point occurs at higher pressure as temperature increases, and the point values are comparable to the pressure required for the formation of CO2 hydrate in pure water. Unlike that on the exclusively microporous carbons, the CO2 adsorption isotherms over micro-/mesoporous carbons showed similar transitions in the presence of water, but no plateau was observed with the formation of CO2 hydrate [29].

Figure 5. CO2 adsorption isotherms on a microporous carbon (a) with different moisture contents at 275 K. 1: Rw = 0, 2: Rw = 1.74, 3: Rw = 1.32 and 4: Rw = 1.65; (b) different temperatures under Rw = 1.31. 1: 281 K; 2: 279 K; 3: 277 K; 4: 275 K (adsorption); 5: 275 K (desorption). [Reproduced with permission from ref. [89]. Copyright 2007 Elsevier].

3.4. NOx, SOx, H2S, CH4

Numerous studies available have focused on the adsorption of pure CO2 on carbon adsorbents [90,91,92], while CO2 is hardly produced as a pure component. In addition to the mentioned water vapor, there are other gas impurities, including NOx, SOx, H2S and CH4, which also can influence the adsorption efficiency of CO2 onto carbon adsorbents [93]. Usually, NOx and SOx in the gas stream will react with or be adsorbed on the adsorption sites, forming complexes with adsorbed compounds, leading to a decrease in the number of sites available for the adsorption of the CO2 molecule. Accordingly, clarifying the impacts of these impurities on CO2 adsorption is essential to determine the feasibility of an effective adsorbent [94].

NOx is a byproduct produced during fuel combustion, which can be adsorbed by porous carbons via primarily chemical process, depending on the presence of oxygen in the flue gas instead of the structural properties of the adsorbents. Zhang et al. [95] investigated the NO adsorption onto different porous carbons with various pore structures and surface functional groups. They found that virtually no NO can be removed in the absence of oxygen, while a large amount of NO was removed rapidly through adsorption and oxidation facilitated by porous carbons that acted as both adsorbent and catalyst. The NOx removal can be enhanced on the metal-loaded and heteroatom- doped porous carbons. Chen et al. [96] studied NO adsorption on ordered mesoporous carbon (OMC) and cerium loaded OMC, finding that oxygen played the key role in NO adsorption, and physical adsorption was the main mechanism of NO removal without oxygen. Additionally, the OMC displayed twice the NO adsorption capacity as the disordered porous carbon, and the introduction of cerium into the OMC enhanced the NO adsorption.

The adsorption of SOx on carbon materials is principally dependent on physical adsorption facilitated by the porous structure and chemical adsorption by surface alkaline functional groups on carbon. Sun et al. [97] inspected the adsorption of SO2 on activated carbon and carbon nanotube, finding that SO2 was mainly adsorbed in the micropores, since the micropores contained strong potential energy fields enabling SO2 to be easily adsorbed onto carbon. A wide pore size distribution is not beneficial to the generation of adsorption potential energy fields, the SO2 adsorption will be reduced. Sethupathi et al. [98] examined the adsorption performances of CO2, H2S and CH4 by four different biomass derived porous carbons produced from perilla leaf, soybean stover, Korean oak and Japanese oak, and the adsorption tests were conducted in a continuous fixed bed. The porous carbons exhibited negligible adsorption of CH4 even without any of the other gases, which was attributed to the large pore size (>1 nm) allowing CH4 molecules to slip. All the carbons exhibited good adsorption performance for pure CO2 and H2S, while the adsorption capacities toward CO2 decreased by 90–95% when the gas mixture was employed. This was because of the competitive adsorption between CO2 and H2S, where H2S was preferred to be adsorbed. It can be concluded that the acidic gases such as H2S can inhibit CO2 adsorption on carbon surface.

Great progress has been achieved in dealing separately with the three common acidic gases found in flue gas, namely CO2, SO2 and NOx, while there is less research on simultaneously removing these three acidic gases through adsorption. On the other hand, it is crucial to understand the mutual influence among the three gases in the adsorption process to improve the adsorption capacity, especially for capturing CO2 in the presence of other acidic gases. Zhou et al. [63] investigated the co-adsorption behaviors of CO2, SO2 and NO that exist in flue gas onto porous carbon by experimental measurement and theoretical model fitting. They found that the Freundlich model was more accurate than the Langmuir model in predicting the adsorption amount, the adsorption affinity of porous carbons towards the three gases followed the order: SO2 > CO2 > NO, and the sequence of required work was as follows: CO2 > NO > SO2. These findings provide some theoretical foundation for removing CO2 by adsorption onto carbon adsorbent in the presence of other acidic gases.

Yi et al. [64,65] examined the simultaneous adsorption of CO2, SO2 and NO on metal-loaded porous carbons. It was found that the Cu-loaded carbon showed better adsorption performance than those porous carbons loaded with other metals such as Ca, Mg and Zn, and the adsorption capacities were 0.367, 0.357 and 0.090 mmol/g for CO2, SO2 and NO, respectively. Furthermore, they found that high temperature impacted negatively the adsorption of these gases and low temperature favored their adsorption on porous carbon. The adsorption capacity of SO2 and NO can be improved in the presence of oxygen, and the oxidation of them into SO3 and NO2 would be promoted by oxygen. Moderate amounts of water vapor can enhance the adsorption capacity of SO2, while reducing the adsorption of CO2 and NO owing to their low solubility in water. Finally, the adsorption mechanisms of CO2, SO2 and NO are illustrated in Figure 6. The acidic gases, including CO2, SO2 and NO, can be adsorbed simultaneously over carbon materials. However, the main adsorption mechanism toward them varied to some extent. Among them, CO2 is primarily adsorbed by physical adsorption, while SO2 and NO are adsorbed mainly by chemical adsorption. Up to now, limited research has been conducted on the simultaneous adsorption of them. Therefore, overcoming the mutual influence of these gases during the adsorption process remains both necessary and challenging. Initial insights into such complex interactions come from studies on binary gas mixtures relevant to flue gas compositions. For instance, research on the co-adsorption of CO2 and acetone (a model VOC) on N-doped biochar revealed an initial competitive adsorption followed by a synergistic phase where acetone enhanced CO2 uptake, likely through dissolution and capillary condensation effects, while CO2 itself inhibited acetone adsorption [99]. It is expected to achieve satisfactory removal results by selecting suitable loading and doping functional groups on carbon materials.

4. Strategies for Enhancing CO2 Adsorption on Porous Carbons

4.1. Tuning Porosity

The textural properties of porous carbon adsorbents are the dominant factors that determine their adsorption performance towards CO2 capture. The pores in porous carbons can be classified into micropore (pore size/width (d) < 2 nm), macropore (d > 50 nm) and mesopore (2 nm < d < 50 nm), relying on the size of the pore. It is generally recognized that the adsorption of small molecules like CO2 is principally dependent on the micropore filling mechanism, and the CO2 adsorption capability of porous carbon is mainly correlated with the narrow microporous structure [102,103]. Previous studies have verified that micropores with a size less than 1 nm, especially ultra-micropores (d < 0.8 nm), are much more beneficial to CO2 uptake at ambient pressure [104,105], and they can improve the selectivity of CO2 to N2 [106]. As an ideal adsorbent, additional properties besides the adsorption capacity, i.e., good regeneration ability, rapid adsorption kinetics, stability, etc., are key to the adsorbents in practical applications [107,108]. Although the mesopore and macropore in porous carbons contribute a little to the adsorption capacity of CO2, they supply channels for rapid diffusion of CO2 and are beneficial to the desorption; then the porous carbon materials in the absence of mesopores usually have poor regeneration ability [109]. In this regard, continuous efforts have been devoted to tuning the pore structure of carbon adsorbents with appropriate hierarchical pore size and pore size distribution for improving their CO2 adsorption performance.

How to fabricate porous carbon with a suitable pore structure has been the focus of research in the CO2 adsorption by porous adsorbents. The fabrication of porous carbon generally requires two steps: carbonization, in which the raw materials are graphitized and activation for tuning the porosity. The overall number of pores, the shape and size of pores, as well as the pore size distribution, determine the adsorption capacity, as well as the adsorption rate. The carbon materials by merely carbonizing the raw materials usually have little pores, which are averse to CO2 adsorption. Some carbonized products have higher porosity, but their pore size distributions are not ideal, in which the pore diameter/width is bigger than the pore size required for CO2 separation with poor selectivity, on account of the heterogeneous composition and structure of the carbon-containing raw materials. To render the as-fabricated porous carbons show better adsorption performance for CO2, it is vital to further tune the pore structure after carbonization by various activation methods. Activation control is commonly used to tune the pore size of porous carbon, which can make the pore structure much more developed by opening or expanding the pores.

Chemical activation by using KOH, K2CO3, ZnCl2, etc., as activating agents is one of the most effective pore creation and regulation methods. Beyond traditional chemical activators, innovative media such as molten salts have been employed to achieve uniform and deep micropore development. For instance, a one-step molten salt thermal treatment using a NaOH-Na2CO3 system was shown to effectively integrate carbonization and activation, producing N/O co-doped biochar with a high specific surface area (up to 3312.89 m2·g−1) and a well-developed microporous network, leading to a CO2 uptake of 6.02 mmol·g−1 at 273 K and 1 bar [110]. Deng et al. [111] fabricated porous carbons derived from peanut shells and sunflower seed shells using KOH as an activating agent, and the optimal porous carbons were achieved at a low KOH/C ratio of about 1.0. The porous carbons derived from the two precursors exhibited CO2 uptake of 1.54 and 1.46 mmol/g at 298 K and 0.15 bar. Though the peanut shell derived porous carbon had much lower surface area and micropore volume than the sunflower seed shell derived porous carbon, it showed higher CO2 uptake owing to its higher volume of micropores in the range of 0.33–0.44 nm. Moreover, the volume of micropores with a width of 0.33–0.44 nm had a linear relationship with the CO2 uptake, demonstrating that these micropores were responsible for CO2 adsorption. Many more studies reported that porous carbons with a pore size of 0.7–0.9 nm possess the maximal CO2 adsorption capacity rather than the larger pores (d > 1 nm) [43,112,113,114]. Recently, Liu et al. [115] further identified that the advantageous ultramicropores (0.6–0.8 nm) in N-doped biochar played a decisive role in CO2 uptake. The pore size in carbon can be roughly controlled by adjusting the carbonization temperature and activation process, while the design and synthesis of efficient porous carbon with a suitable micropore size requires more sophisticated means, which include choosing a proper precursor, performing an appropriate pre-treatment method and activation process.

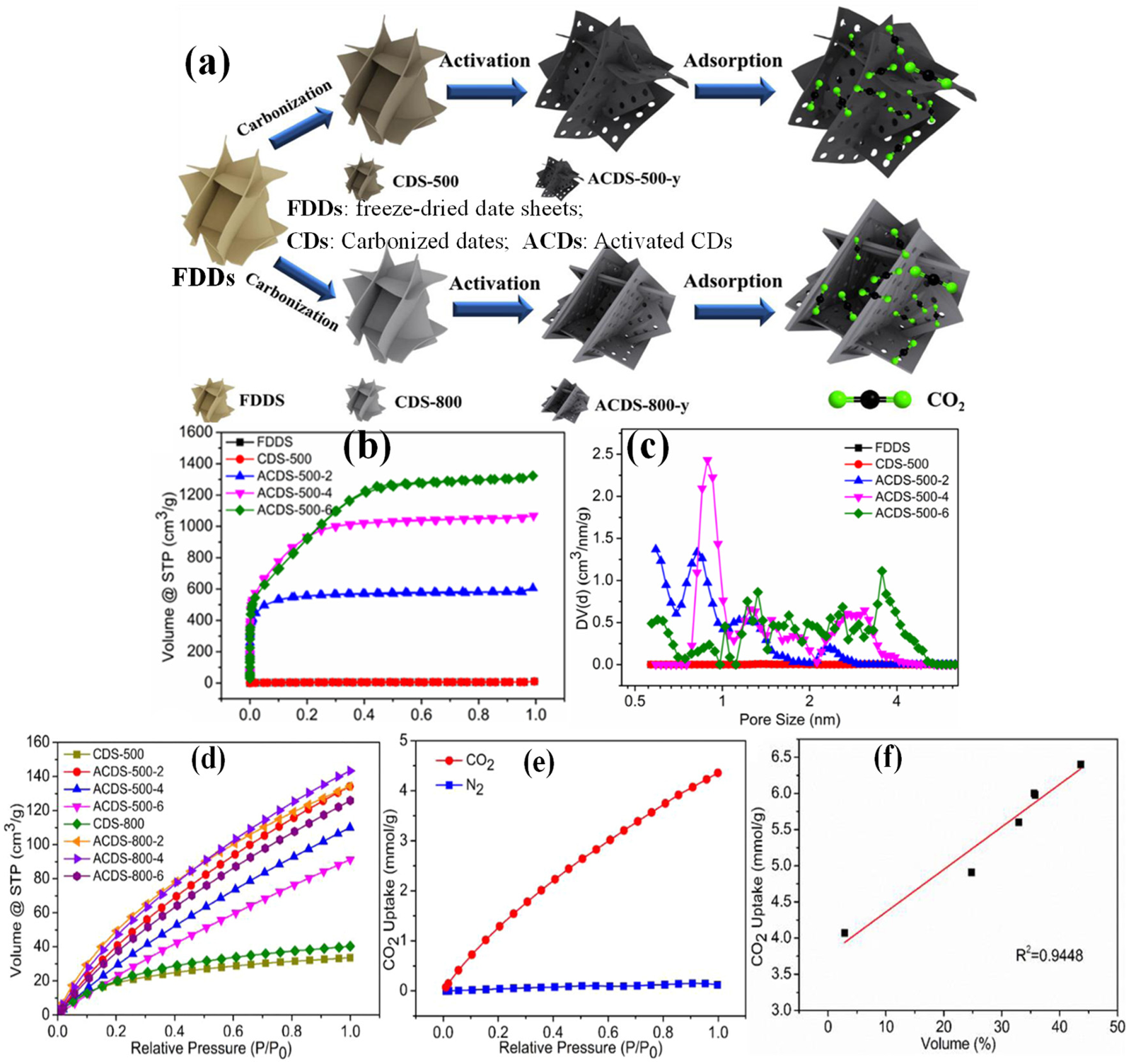

Tang et al. [116] prepared porous carbon by selecting date sheets as carbon sources, combined with controllable carbonization and subsequent KOH activation. Figure 7a shows the synthesis procedure. The date sheets have the natural internal open pores consisting of thin laminates, which can be tailored towards promoting the activation step. The fresh date was first pre-treated with washing, impurity removing and cutting into small sheets, and the reprocessed date sheets were freeze-dried overnight for 48 h and designated as FDDS (freeze-dried date sheets). The FDDS were carbonized at 500 and 800 °C obtaining CDS-500/800, and the CDS were activated by pyrolysis of the mixture of CDS/KOH with a certain ratio to achieve ACDS. Figure 7b,c display the N2 isotherms and corresponding PSD plots. These isotherms and PSDs demonstrated that the pore structure varied significantly with the mass ratio of KOH to CDS. All the samples have type-I isotherms with a high N2 uptake at a low relative pressure (P/P0 < 0.1) and a wide adsorption knee and plateau, indicative of the microporous structure. As the KOH/CDS increased from 2 to 6, the adsorption knee became wider, suggesting the production of more mesopores. This study disclosed that the temperature had less impact on the pore structure, as the temperature increased from 500 to 800 °C, the N2 isotherms, PSDs and the textural parameters did not change much, maybe due to the carbon source and freeze-dried pre-treatment. Figure 7d exhibits the CO2 adsorption isotherms over all the date derived carbon samples. It can be observed that the CO2 adsorption capacities of all activated samples are obviously higher than those of the mere carbonized samples without activation. The ACDS-500-2 has a CO2 adsorption capacity of 5.98 mmol/g, which is close to ACDS-800-2 and ACDS-800-4 with values of 6.0 and 6.4 mmol/g at 0 °C. Figure 7e shows the typical adsorption isotherms toward CO2 and N2 at 25 °C on ACDS-800-4, demonstrating the good selectivity (41.53) of ACDS-800-4. The relationship between the pore size and CO2 uptake in Figure 7f revealed that a good linear relationship existed as the pore size was in the range of 0.7–0.9 nm, and the pores with a size of 0.5–0.7 nm play a major role in CO2 adsorption. The adsorption of CO2 has the optimized energy [117], when the pore size is two or three times of a CO2 molecule (ca. 0.33 nm).

Figure 7. (a) Illustration of the syntheses of CDS-x, ACDS-500-y and ACDS-800-y from FDDS; (b) N2 adsorption/desorption isotherms and (c) pore size distributions (PSDs) plots of FDDS, CDS-500; (d) CO2 adsorption isotherms of all samples at 0 °C and 1 bar, (e) CO2 and N2 adsorption isotherms at 25 °C and (f) Correlations between the amount CO2 uptake and proportion of cumulative pore volume of pores with pore size of 0.7–0.9 nm of ACDS-800-4. [Reproduced with permission from ref. [116]. Copyright 2019, Elsevier].

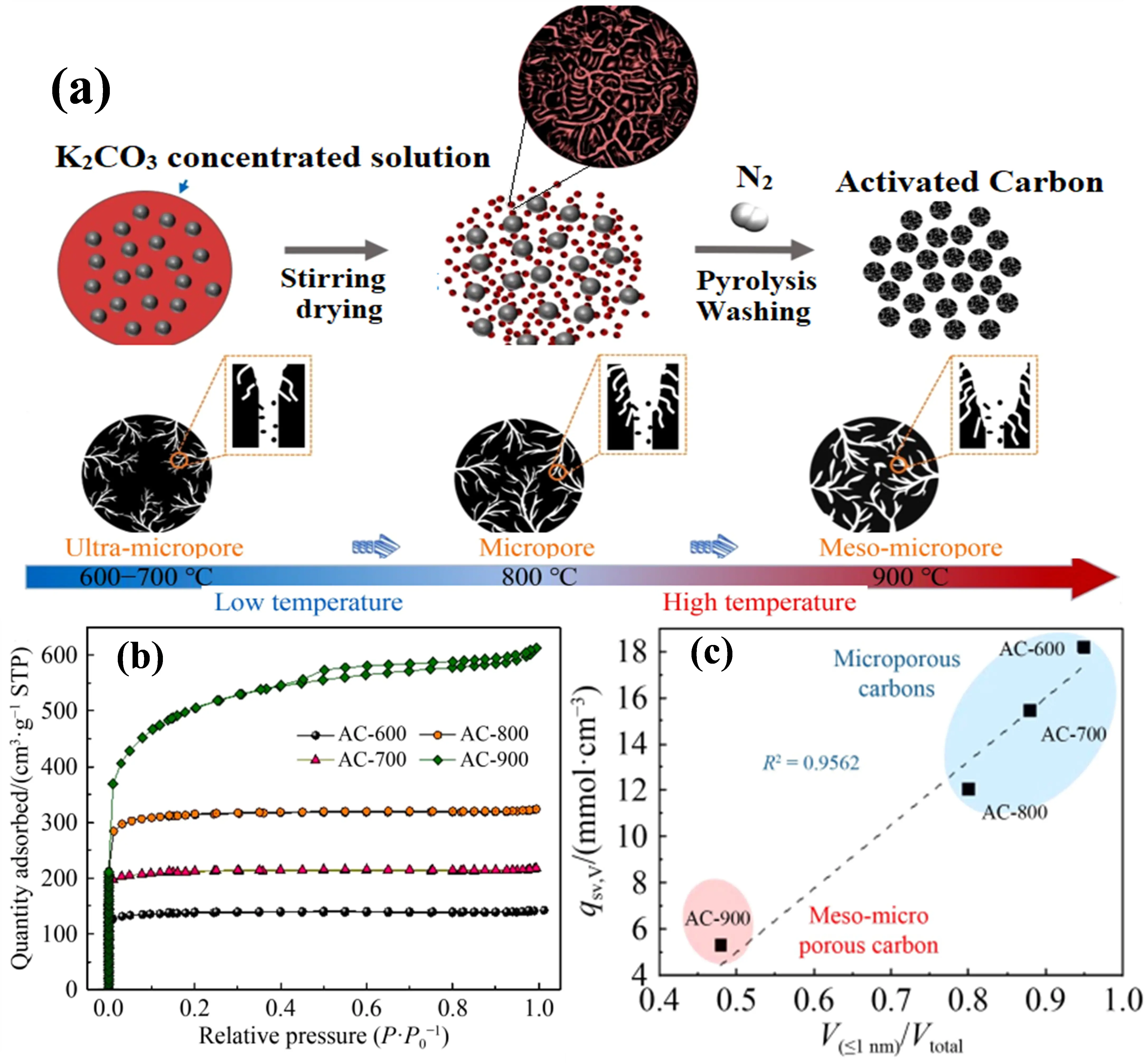

Up to now, most studies focused on enhancing the CO2 gravimetric adsorption performance onto porous carbons with low packing density, which can cause the insufficient utilization of pores rich in porous carbons. On the other hand, CO2 adsorption capability per volume of porous carbons can provide a relatively realistic indication of their performance, compared with the gravimetric performance. Additionally, the volumetric CO2 adsorption capability of porous carbon is an essential indicator for assessing the efficiency and scale of adsorption systems [118,119,120], whereas it is often overlooked in the field of CO2 capture by adsorption [102,121]. For the sake of obtaining porous carbons with high volumetric CO2 adsorption capacity, porosity regulation of carbon is a prerequisite because the pore configuration and size can influence remarkably the packing density of porous carbons [122]. In order to develop desirable porous carbon with high volumetric CO2 adsorption capacity, Qie et al. [123] employed a simple chemical activation using K2CO3 as the activating agent to prepare coal-derived porous carbons. Figure 8a displays the fabrication process of coal-derived porous carbons and the formation mechanism. By simply varying the pyrolysis temperature from 600 to 900 °C, the porosity in the coal-derived carbons can be controlled. As illustrated, the ultra-micropores obtained at 600–700 °C in the resulting porous carbons gradually grew into micropores and meso-micropores at 800 and 900 °C, respectively. Figure 8b,c shows the N2 adsorption-desorption isotherms and the correlation between the CO2 uptake and the PSDs. The obtained ACs were used as a CO2 adsorbent, revealing the importance of ultramicropores for CO2 uptake. The ultra-microporous carbon (AC-600) with a high packing density exhibited the highest volumetric capacity of 1.8 mmmol/cm3 at 0 °C. Their experimental results and molecular dynamic simulation disclosed that CO2 adsorption capacities increased linearly with the micropore volume, whereas the volumetric capacities were directly proportional to the ultra-micropore volume.

Figure 8. (a) Schematic illustration of the fabrication of coal based activated carbon (AC) by K2CO3 activation and the corresponding pore formation mechanism in the ACs; (b) N2 adsorption/desorption isotherms of the ACs prepared at different activation temperatures; (c) Correlations between the amount CO2 uptake per volume and V(d ≤ 1 nm)/Vtotal) of the ACs at 0 °C. [Reproduced with permission from ref. [123], Copyright 2022, Springer].

Chemical activation has advantages in preparing porous carbons, for example, the obtained porous carbons usually have a high specific surface area and abundant micropores, and the operating temperature is low (<900 °C) [124]. On the other hand, it has obvious shortcomings, which are the use of strong alkali or acid in the activation process, which will cause low carbon yield, corrosion to the instruments and environmental pollution. Apart from chemical activation, physical activation is often used to tune porosity in carbon materials. Physical activation has been well commercialized for the production of coal or biomass derived porous carbon. Specifically, in the physical activation process, oxidizing gases (i.e., H2O, CO2, O2, etc.) are often used as the activation agents to generate pores, in which small volatile molecules first release from the carbon matrix forming the initial pores at low-/medium temperature, then the gas activation agents gradually etch the carbon framework from the surface to inside to create desirable porosity. This process usually involves the reactions: C + H2O → H2 + CO (−131 kJ) or C + CO2 → 2CO (−170.5 kJ) at varied temperatures (ca. 700–1000 °C) [124,125]. Relatively, physical activation is environmentally friendly, while it wastes a lot of carbon. The main strategy of regulating the pore structure of carbon by physical activation is to adjust the reaction atmosphere [126], for example, choosing a proper activating agent and temperature, due to the diversity in molecular size, diffusivity and reactivity of the activation agents. Recently, microwave pyrolysis has been shown to be an efficient alternative for fabricating porous carbons with uniform pore structures and high specific surface areas, owing to its inward-to-outward heating mode, which reduces pore blockage and promotes pore development [127]. However, the porous carbons obtained by physical activation generally have low specific surface area (less than 1000 m2/g) and low pore volume (<0.5 cm3/g), because of the low reactivity between gaseous activation agents and carbon framework, so the adsorption performances are usually unsatisfactory.

In view of the weaknesses of a sole physical or chemical activation method, it is necessary to develop low-cost, facile and effective strategies for tuning porosity in carbon. Catalytic activation is a promising method, referring to the addition of metal compounds to a carbon source to increase the surface-active points. To tune the porosity of coal-derived carbons and reduce the dosage of activation agents, Sun et al. [128] proposed a green and efficient strategy for preparing porous carbons, namely, a trace K2CO3 induced catalytic CO2 activation system. In their strategy, a small amount of K2CO3 was added (less than 2% weight ratio of coal), which can prominently reduce the reaction barrier between the CO2 molecule and the coal framework, facilitating the pore formation of the coal-derived porous carbons. The resulting coal-based porous carbon using trace K2CO3 has short range ordered microcrystalline structure and developed pore structure with a high specific surface area of 1773 m2/g and pore volume of 1.11 cm3/g, even superior to the porous carbon using a large dosage of K2CO3 (K2CO3/C=3), and was three times more than those samples from solely CO2 activation. They found that the potassium-base component (mainly C–O–K structure) embedded in the coal matrix can act as a catalyst for intense erosion reaction between coal and CO2 molecule, which was generated during a CO2 atmosphere at high temperature and can enhance the pore formation in the resulting porous carbons. When used as a CO2 adsorbent, the trace-K2CO3 catalyzed porous carbon exhibited high CO2 adsorption capacity with value (4.36 mmol/g at 0 °C) and good adsorption-regeneration cycling stability.

4.2. Surface Modification

In addition to textural properties, the surface chemical structure of porous carbon has been verified to affect CO2 adsorption capability significantly [126,129,130,131,132]. The chemical property depends on the type and number of surface functional groups, which affect the interaction between CO2 and the porous carbon. As discussed above, the adsorption capacity toward CO2 will decrease with increasing temperature, but can be enhanced prominently by chemical modification. For example, when basic groups are introduced into the surface of porous carbon, the modified porous carbon will show stronger interaction with CO2 than the pure porous carbon, due to the introduced basic sites having intermediate affinity to CO2. Of course, the affinity is inadequate to induce chemical adsorption for CO2 [133]. The enhancement of the interaction between the adsorbent and CO2 molecules can be realized by various kinds of surface modification techniques. The modification techniques for porous carbon include physical, chemical or microbiological methods, which are very important because they can change the physical structural properties or surface chemical functional groups [134], so as to enhance the CO2-adsorbent interaction. The direction of these modifications is pore functionalization by introducing polar groups, for instance, nitro, hydroxy, amine, sulphonate, imine, etc. [129]. These surface functional groups (SFGs) can be introduced either prior to adsorbent synthesis by judicious selection of modification of the precursors, where CO2-philicmoieties will form during the synthesis procedure, or alternatively via post-synthesis modification when functional groups are introduced and attached to the surface of carbon.

Heteroatomic doping is a frequently used strategy to modify the surface chemical properties of pristine carbons. For most pristine porous carbons, their CO2 adsorption capacities are less than 3 mmol/g at atmospheric pressure [113], which is attributed to the limited active sites mainly derived from defects on the surface of adsorbents. Heteroatom doping usually involves the introduction of nonmetal element into the carbon matrix, and it is one of the most efficient ways to generate defects, in that the doped heteroatoms have similar atomic radius, orbit, electronegativity and charge density with carbon atoms that can change the electron and surface charges of the final materials [132,133,134]. Various kinds of heteroatoms have been successfully doped into porous carbons, for example, N, B, O, S, P, etc., obtaining higher CO2 adsorption capacity and selectivity compared with the unmodified counterpart [135]. The enhancement is primarily attributed to increased electrostatic interactions with acid-type gases, such as CO2.

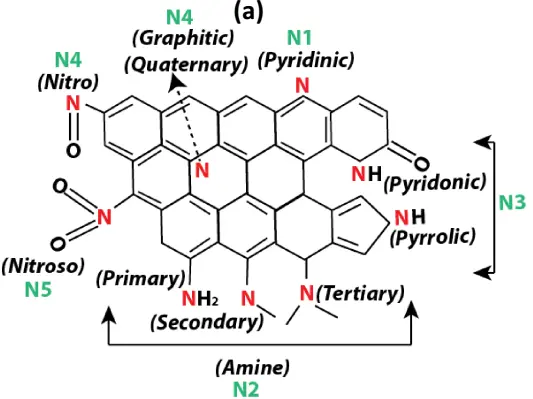

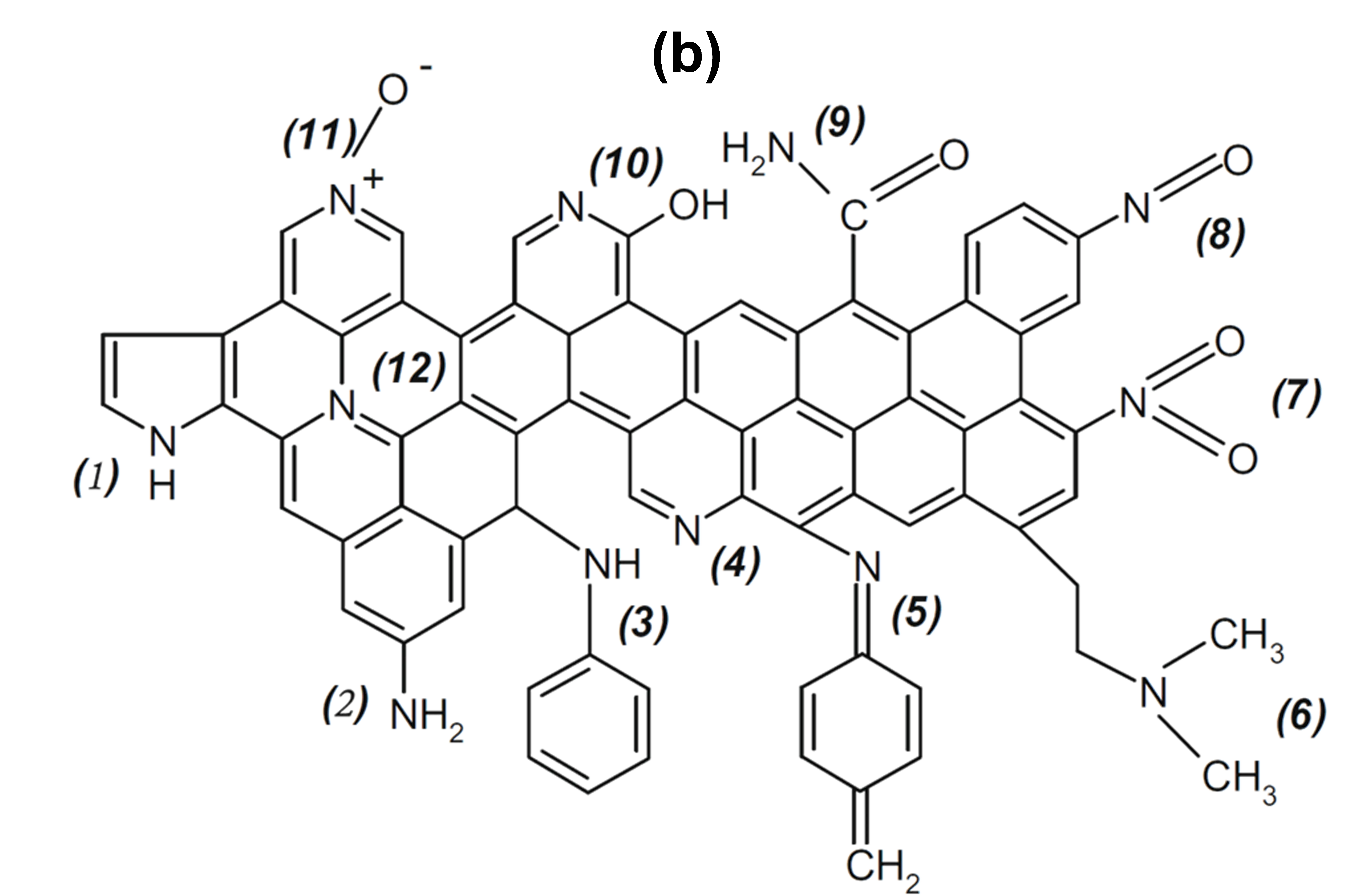

As an adjacent element to carbon, nitrogen bears several similar chemical properties and atomic size with carbon [136], and can generate relatively stable chemical bonds with carbon [137]. Due to such similarities, introducing nitrogen will theoretically the electron density of the carbon framework or increase the basicity, which will in turn anchor the electron deficient carbon of CO2 to the carbon pore surface via Lewis acid-base (N atom) interactions [138]. Therefore, nitrogen is the most investigated heteroatom doped in carbon materials [139], since nitrogen atoms can easily enter the carbon skeleton without causing a serious lattice mismatch. Nitrogen-doped carbons generally refer to the modified carbon matrix where few carbon atoms are replaced by nitrogen atoms, being enriched with diverse types of nitrogen bearing functionalities on their surface. The possible nitrogen species and nitrogen functionalities formed on carbon surface are illustrated in Figure 9. The typical nitrogen species on carbon surface include pyridinic, pyridonic, pyrrolic, graphitic or quaternary nitrogen, combined with amine, nitro, nitroso and amide type. The amine functionalities consist of all the primary, secondary and tertiary amine. Apart from quaternary nitrogen, the other types of N-functionalities formed at the edge site of the graphitic plane, creating more defects than the undoped carbon.

Generally speaking, doping nitrogen via post-synthesis (activation) method will decrease the specific surface area and pore volume, for the introduced N in the carbon skeleton can lead to blocking of the earlier developed pore structure, which is disadvantageous to the CO2 adsorption capacity. However, the introduction of N can result in a considerable decrease in the amount of surface acidic groups and an increase of surface basic groups due to the generated nitrogen functionalities. Specifically, nitrogen functionalities on the carbon surface provide a lone pair of electrons, so they can act as the attractive sites for the electron-deficient carbon atom of the CO2 molecule owing to the high electron-withdrawing properties of oxygen atoms [136]. Moreover, the basicity of nitrogen-doped carbon can strengthen the dipole-dipole interactions and hydrogen- bonding to the surface, leading to an increase in the selectivity over non-polar gases such as N2 and CH4 [137,138]. On the other hand, the polar nitrogen functional groups will improve the hydrophilicity of carbon, and the H2O molecules are usually trapped inside the narrow micropore of carbon on account of the enhancement in hydrogen bonding with H2O [131,139,140]. Thus, the nitrogen-doped porous carbons may be better suited to the adsorption removal of CO2 in the dry flue gas.

Figure 9. (a) Nitrogen species on doped carbon surface via NH3 activation (Reproduced from Ref. [131], with permission from Elsevier), (b) Various types of nitrogen functional groups on coal-derived nitrogen-doped carbon: (1) pyrrole, (2) primary amine, (3) secondary amine, (4) pyridine, (5) imine, (6) tertiary amine, (7) nitro, (8) nitroso, (9)amide, (10) pyridone, (11) pyridine-N-oxide, (12) quaternary nitrogen (Reproduced from Ref. [140], with permission from Elsevier).

Nazir et al. [141] fabricated N-doped porous carbons utilizing polyacrylonitrile (PAN) as carbon source and NaNH2 as both porogen and nitrogen supply during carbonization. The resulting optimized “PN-3” sample had satisfactory textural features with SSA of 2490 m2/g and pore volume of 2.06 cm3/g, together with nitrogen content of 6.4 at.%. The experimentally measured CO2 uptake for all the N-doped porous carbons ranged from 5.17 to 7.15 mmol/g at 273 K/1 bar, from 4.13 to 5.59 mmol/g at 283 K/1 bar. It also exhibited an excellent CO2/N2 selectivity (~102) based on the ideal adsorbed solution theory at 273 K, surpassing the performance of most undoped porous carbons. Additionally, the CO2 adsorption process was driven by physisorption, indicated by the relatively low isosteric adsorption heat of 39.10 kJ/mol and low activation energy of 5.05 kJ/mol. Wang et al. [142] synthesized nitrogen-doped porous carbons through carbonization of ZIF-8 and ZIF-61 assisted by KCl and NaCl, showing a highly microporous structure and high nitrogen content. Their results demonstrated that the cumulative pore volume in the pore size of 5–7 Å, pyrrolic-N content and COOH content played favorable influence on CO2 adsorption capacity. The evaluation by a multiple linear regression equation confirmed that the optimum pore structures (V5–7Å > 0.10 cm3/g) and pyrrolic-N were the dominant contributors to CO2 adsorption capacity. The highest CO2 adsorption capacity of 4.61 mmol/g at 298 K and 6.70 mmol/g at 273 K can be acquired with a high CO2/N2 selectivity of 39.5 under typical flue gas and cycling stability.

Besides PAN and ZIF, other precursors have been utilized to prepare nitrogen-doped carbon via in-situ method. Liu et al. [143] transformed oxytetracycline fermentation residue into an in-situ N-doped nanoporous carbon by low-temperature pyrolysis coupled with pyrolytic activation. They found that the mild activation conditions (600 °C, KOH/carbon = 2) resulting in micropore-rich porous carbon with high in-situ nitrogen content, and the doped nitrogen in the carbon skeleton with high oxygen enhanced electrostatic interactions facilitating the CO2 adsorption. The maximal adsorption capacity arrived at 4.38 and 6.40 mmol/g at 298 and 273 K and 1 bar, with high CO2/N2 selectivity (32/1) and favorable Qst (33 kJ/mol) as well as excellent reusability (decreased by 4% after 5 cycles). Wu et al. [144] produced nitrogen-doped porous carbons from bamboo shoot shells using urea as a nitrogen source, activated by potassium carbonate. Their results revealed that the as-produced N-doped porous carbon exhibited a fibrous structure and distinct worm-like microporous structure, and the largest specific surface area was 1985 m2/g with a nitrogen content of 1.98 at.%. The optimized sample demonstrated outstanding capacity of CO2 adsorption with values of 7.52 and 3.60 mmol/g at 273 and 298 K under 1 bar, and it also exhibited excellent cyclic stability and CO2/N2 selectivity. The thermodynamic calculations verified that the CO2 adsorption process on nitrogen-doped biochar was spontaneous and exothermic, indicative of its physical adsorption. Furthermore, Zhang et al. [145] utilized fir sawdust as a precursor, employing urea and thiourea as nitrogen and sulfur sources with a secondary activation strategy to yield micropore-rich carbon. The resulting material showed high selective CO2 capture with an uptake of 3.96 mmol/g at 298 K and 1 bar and a CO2/N2 selectivity of 47.

Like nitrogen, boron is an adjacent element to carbon with similar chemical properties and atomic size to carbon [141], so the spatial structure of B-doped carbon materials will not change significantly [142], while there are more active sites on the B-doped carbon surface with enhanced adsorption performance due to the uneven electron distribution on their surface [143]. By contrast, boron loses electrons while nitrogen gains electrons to form relatively stable chemical bonds with carbon (BC3), suggesting that the carbon atoms adjacent to boron show different electronegativity from those adjacent to nitrogen [146]. Li et al. [147] investigated the influence of boron-doped porous carbon on the CO2 adsorption performance. Their results demonstrated that the B atom played a beneficial role in the CO2 adsorption process, and the B-doped carbon with a B/C ratio of 0.05 exhibited the highest CO2 adsorption performance with 2.16 mmol/g at 303 K and 1 bar. Through in-depth analysis, it is found that boron presents some contradictions in the adsorption performance of B-doped carbons. On one side, boron doping can create useful active sites and the boron-doped carbon has some Lewis basicity, which is advantageous to the interaction with CO2 molecules having weak Lewis’s acidity. On the other hand, the oxygen affinity of boron means the boron-doped structure is easily oxidized, and the Lewis alkalinity of the oxidized structure is weakened that impair the CO2 adsorption performance. Thus, it requires further exploration of how to form stable boron-doped carbon for improving CO2 adsorption performance of B-doped carbon.

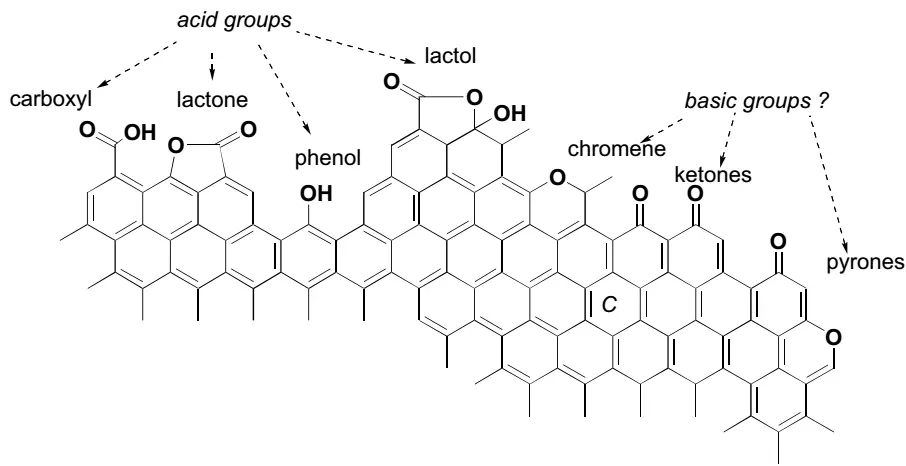

Oxygen is often doped into the carbon skeleton to improve the CO2 adsorption performance, because oxygen is the next most frequent element to carbon, and the oxygen-containing groups can contribute to determining the hydrophobicity/hydrophilicity and acidity/basicity of carbon adsorbents. Figure 10 shows the common oxygen-containing functional groups [146], which are traditionally divided into two categories according to their acidic or basic character. It is well-recognized that carboxyl groups, lactones, phenol and lactol groups account for the acidic character of carbon materials. While there are controversies on the basic groups, chromone, ketones and pyrones were proposed as the basic O-containing functionalities [147,148]. The pyrone-like groups at the edges of the carbon surface could be the most important basic functionalities. The pristine carbon is usually hydrophobic, so the degree of hydrophilicity is often decided by the amount of polar O-groups [130]. Unfortunately, the increase of hydrophilicity is not conducive to CO2 adsorption, since it enhances the adsorption of moisture in the flue gas, leading to the reduction of active adsorption sites toward CO2. Even so, the oxygen functionalities can improve the adsorption properties of carbon toward CO2. For example, an increase of 26% in CO2 uptake has been reported on the oxidized phenolic resin derived carbon compared with the unmodified carbon [149].

Generally, O-containing functionalities are produced from the oxidation of organic structures during various kinds of chemical/physical activation procedures [150]. Acidic groups are formed at relatively low temperatures under oxidization with HNO3, H2O2, H3PO4 or H2SO4 [151]. More strong surface basicity could be introduced by NaOH activation than H3PO4 at the same temperature of 850 °C. The basic groups can be more effectively introduced by activation with H3PO4 in the presence of steam than in an inert (N2) atmosphere [152], and extreme activation conditions were shown as detrimental to the formation of surface functional groups [153]. The surface O-containing groups of porous carbon have electron-rich properties, which can strengthen the interactions between the CO2 molecule and carbon surface owing to the introduction of various polar groups [154]. Bai et al. [155] modified activated carbon fibers (ACFs) by liquid oxidation with hydrofluoric acid to introduce O-containing functional groups. The liquid-oxidized ACF had 112% higher CO2 adsorption capacity than those observed onto the pristine ACFs. The enhancement was attributed to the synergistic effects of developed pores and the O-functionalities that guide CO2 into the micropores via the attractive forces exerted on the electrons in CO2 molecules. Then they concluded that the introduction of carboxylic and hydroxyl surface groups was effective in improving CO2 adsorption performance.

As for the enhancement of CO2 adsorption by oxygen-doped carbon, there are some different reports. Tiwari et al. [156] thought the high content of O-containing basic groups contributed to the highest CO2 adsorption capacity of the epoxy resin-derived carbons. Babu et al. [157] found aht the CO2 adsorption capacity increased with the oxygen concentration, and postulated that both –OH and –COOH groups facilitated the considerable improvements in CO2 adsorption capacity at ambient pressure. As mentioned above, nitrogen-containing groups can present Lewis basic character of carbon materials. Beyond that, the oxygen-containing groups also have a similar function. O-groups like ethers, alcohols and carbonyls comprise electron-donating oxygen atoms, which participate in the electrostatic interactions with the CO2 molecule [149,158], then improving the adsorption of polarizable species such as CO2 by Lewis acid-base interactions [159]. Among the basic oxygen functionalities, pyrone is often investigated, and pyrone-like structures are the combinations of non-neighboring carbonyl and ether-O at the edges of a graphene layer [146]. The basicity of pyrone originated from the stabilization of its protonated form via electronic π-conjugation throughout sp2 skeleton of the carbon basal plane [130,160]. –OH group is often reported as basic and affects the adsorption of CO2 due to its high electron density [161,162]. The interactions between –OH groups and the CO2 molecule mainly depended on the hydrogen-bonding and high electrostatic potential [163,164]. A linearity between CO2 adsorption capacity and the content of oxygen groups was observed at 298 K below 0.5 bar, while it was not found when the adsorption pressure was increased from 0.5 to 1 bar.

Sulfur is also frequently doped in carbon materials to improve their application performances. Compared with N, O and B atoms, sulfur is much larger in size so that it can protrude out of the graphene plane, resulting in the increased graphite layer spacing, the distortion and deformation and a large amount of strains and defects within the carbon skeleton [130,165]. These defects and strains can alter the original charge distribution, inducing charge localization, so that more active sites will be produced in the S-doped carbons that are conducive to CO2 adsorption [166]. Additionally, S-doping can increase the reactivity owing to the lone-pair electron donation of the sulfur atom [167]. Xia et al. [168] reported that the S-doped carbons exhibited higher CO2 uptake capacity than the S-free carbon, which was ascribed to the strong pole-pole interactions between the large quadrupole moment of CO2 molecules and polar S-groups associated with sites. Seem et al. [169] found a linear relationship between CO2 adsorption capacity and the quantity of oxidized-S in the S-doped porous carbons, and the S-doped microporous carbons were more effective than similarly prepared N-doped samples in CO2 adsorption. Density Function Theory (DFT) calculations revealed that the interaction of CO2 with sulfoxides and sulfones was stronger than those with N-moieties, according to the calculated binding energy.

Phosphorus is another heteroatom extensively doped in carbon materials. Phosphorus belongs to the nitrogen group and is also electronegative, having similar chemical property with nitrogen, doping phosphorus into carbon will alter the electron density of carbon structures, producing some active sites [170,171]. Different from nitrogen, phosphorus has a larger atomic size, thus the formation of the C–P bond will increase the spacing of the graphite layer, leading to further changes in density [172]. Up to now, there are few reports on phosphorus dope carbon materials applied in CO2 adsorption, so the corresponding enhanced adsorption mechanism is rarely reported and not clear. Zhou et al. [171] investigated the CO2 capture by several carbon phosphides with the assistance of an electric field, finding that the carbon phosphide acting as a CO2 adsorbent had good CO2 capture performance. However, a recent study on N and P co-doped porous biochar has successfully demonstrated enhanced CO2 capture performance under conventional conditions and provided a detailed synergistic mechanism analysis focusing on the tuning of nitrogen species and active sites [173]. Accordingly, it is necessary to conduct further investigations to understand how the atomic charge of phosphorus and the spatial structure of phosphorus doped carbon affect the CO2 adsorption.

4.3. Metal Impregnation

Another modification of porous carbon is metal modification, and numerous reports have clearly indicated that the impregnation of metal ions onto carbon can combine their respective multiple advantages, resulting in great-enhanced CO2 adsorption performance [174,175,176]. In fact, metal oxides are often employed as adsorbents independently for CO2 adsorption in industrial applications, due to their acid-base and redox properties. Unfortunately, there are some limitations for the usage of metal oxide alone in CO2 adsorption, for example, low surface area and poor stability. Impregnating metal oxide can increase the oxygen groups on the surface of porous carbons, serving as a metal oxide anchoring site, which facilitates the CO2 adsorption by tailoring the basic characteristics of porous carbons. Metal oxide impregnated porous carbon (MPC) has excellent mechanical features due to the size quantization effect, especially towards CO2 [177], and a great number of active sites for CO2 adsorption will be generated. Therefore, MPCs have been employed to improve CO2 adsorption ability; various kinds of metals, including sodium (Na), Calcium (Ca), magnesium (Mg), nickel (Ni), etc. have been introduced into porous carbons for improving CO2 adsorption capability of porous carbons [153,178].

MPC can effectively adsorb CO2 via physical and chemical sorption over a wide temperature from 473 K to 673 K, and low energy is required for CO2 regeneration [179]. Othman et al. [180] incorporated four different types of metal oxides into activated carbon nanofibers (ACNF), such as magnesium oxide (MgO), manganese dioxide (MnO2), zinc oxide (ZnO) and calcium oxide (CaO) by electrospinning and pyrolysis process. They observed the ACNF with MgO incorporation exhibited the largest surface area of 413 m2/g and the highest CO2 adsorption of 60 cm3/g at 298 K and 1 bar. Similarly, Lahijani et al. found that a Mg based MPC showed a higher CO2 adsorption potential (82.0 mg/g) than raw activated carbon (72.6 mg/g) [153]. In addition, cyclic CO2 capture experiments demonstrated that porous carbon containing basic metals had a higher capacity for CO2 adsorption because it can react with acidic CO2 molecules. MPC impregnated with Mg via Mg(NO3)2 salt yielded 3.1 mmol/g CO2 adsorption, while MPC with Mg-sugarcane via MgCl2 salt achieved CO2 adsorption capacity of 227–235 mg/g [176]. The plain TiO2 showed a comparably limited CO2 adsorption capacity verified by the isothermal experiments [181], and the highest CO2 adsorption capacity was only 3.1 mmol/g at 313 K, even up to 25 MPa. Likewise, Tungsten (VI) oxide (WO3), as an earth-abundant metal, has a low CO2 adsorption capacity of 0.3 mmol/g at 313 K that is lower than that of TiO2 [182]. Fortunately, impregnating TiO2 or WO3 into carbon can improve the CO2 adsorption affinity, as the doping procedures and composites of metal oxide-carbon increase the Lewis basicity, allowing their better adsorption of Lewis acidic CO2 [183]. Especially, the addition of an oxygen-rich surface functionality of porous carbon to the WO3 lattice can improve the CO2 adsorption, implying a better affinity toward CO2.

Table 2 summarizes the porous carbons modification with impregnation of various kinds of metal oxides, for example, MgO, NiO, CuO, etc. All these results have indicated that the impregnation of metal oxide onto porous carbon surely enhanced the CO2 adsorption capacity compared with the raw carbons. On the other hand, there are also some reports that the CO2 adsorption capacity was reduced as metal oxides were impregnated into porous carbons.

Table 2. Summary of CO2 adsorption performance of porous carbon impregnated with different metal oxides.

|

Adsorbent Materials |

SBET (m2/g) |

Adsorption Conditions |

CO2 Uptake (mmol/g) |

Change of Perf. (%) |

Refs. |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Carbon Precursor |

Metal Oxides |

Temp. (K) |

Pres. (bar) |

||||

|

Coconut shell |

MgO |

976 |

298 |

1 |

2.63 |

50.3 |

[184] |

|

Commercial Activated carbon |

NiO |

925 |

298 |

1 |

2.73 |

10.1 |

[185] |

|

MgO |

820 |

298 |

1 |

2.68 |

8.1 |

||

|

Activated carbon |

CuO |

1974 |

303 |

1 |

6.78 |

124.5 |

[186] |

|

Mesoporous carbon |

MgO |

298 |

353 |

1 |

5.45 |

- |

[187] |

|

Charcoal |

CaO |

63.6 |

298 |

1 |

15.1 |

- |

[188] |

|

Carbon nanofiber |

NiO |

331 |

298 |

1 |

2.40 |

- |

[189] |

|

Hickory chips |

FeOOH |

- |

298 |

1 |

3.64 |

much |

[190] |

|

Activated carbon |

Cu/Zn |

599 |

303 |

100 kPa |

2.25 |

48.0 |

[191] |

|

Walnut shell |

MgO |

292 |

298 |

1 |

1.86 |

12.9 |

[153] |

|

Carbon nanofiber |

MgO |

413 |

298 |

1 |

1.38 |

- |

[180] |

|

Activated carbon |

γ-Fe2O3 |

833 |

298 |

1 |

2.47 |

27.1 |

[192] |

|

Activated carbon |

CuO |

1277 |

303 |

100 kPa |

2.11 |

28.7 |

[193] |