Investigating the Interplay of Springshed Phenomenon and Its Crucial Role in Fostering Sustainable Practices and Community Resilience: Reflection from the Indian Himalayan Regions

Received: 02 December 2025 Revised: 16 December 2025 Accepted: 20 January 2026 Published: 26 January 2026

© 2026 The authors. This is an open access article under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

1. Introduction

Water scarcity has emerged as a critical socio-environmental challenge in the Indian Himalayan regions, directly affecting nearly 50 million people, of whom approximately 60% depend primarily on spring water for drinking, domestic, and livelihood-related activities [1]. Springs represent the most reliable decentralized water sources in these mountainous terrains, where steep slopes, fragile geology, and pronounced climatic variability highly constrain surface water availability. According to NITI Aayog [2], the Indian Himalayan belt hosts about 21,237 springs distributed across diverse physiographic settings, forming complex hydro-ecological systems intricately linked with local land use, vegetation cover, lithology, and subsurface flow regimes [3].

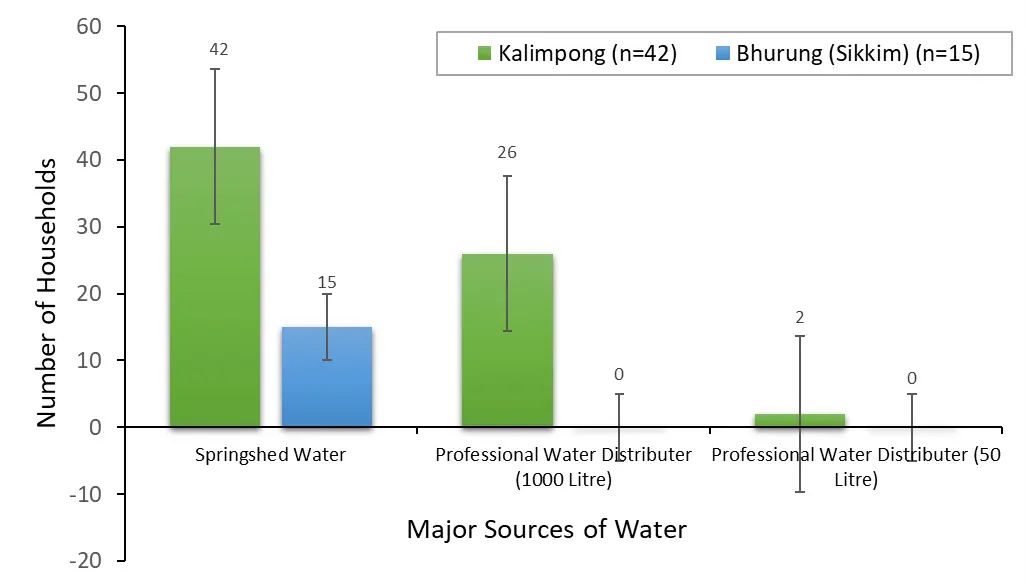

From a hydrogeological perspective, springs are surface manifestations of groundwater systems governed by recharge–storage–discharge dynamics within discrete springsheds. These systems exhibit strong sensitivity to climatic drivers, including temperature, precipitation patterns, and evapotranspiration, which collectively influence groundwater recharge efficiency, baseflow persistence, and seasonal discharge variability. In recent decades, increasing rainfall variability, climate change, population growth, unplanned urban expansion, and unsustainable land-use practices have disrupted these delicate balances, leading to declining spring discharge, reduced seasonal storage, and, in many cases, complete spring drying [4]. Such perturbations are further intensified in densely populated springsheds, where per capita water demand places disproportionate pressure on limited subsurface storage, accelerating aquifer stress and compromising long-term water security [5]. Figure 1 conceptualizes Himalayan springsheds as coupled hydro-ecological–social systems, illustrating recharge–discharge dynamics, land–water interactions, and community governance pathways that collectively enhance water security, ecosystem integrity, climate resilience, and sustainable livelihoods in the Indian Himalayan region.

Quantitatively, springshed systems can be conceptualized as coupled socio-hydrological units characterized by measurable indicators such as long-term discharge persistence, groundwater recharge rates, seasonal flow variability, and storage–release behavior [6]. Metrics such as long-term persistence indices (e.g., Hurst parameters), variability coefficients of spring discharge, and recharge–discharge lag times offer a formal framework to interpret springs as dynamic systems rather than static water points. Embedding such hydrogeological metrics within springshed studies enables a more rigorous linkage between physical groundwater processes and observed socio-environmental outcomes, thereby strengthening the scientific basis for springshed-based water management and resilience planning [7].

The springshed phenomenon is particularly significant in regions such as Kalimpong and Sikkim, where spring-fed water systems support more than 15% of India’s population [8]. In Sikkim alone, nearly 94.2% of villages rely predominantly on springs as their principal water source [9]. Beyond fulfilling domestic water needs, springs play a crucial ecological role by sustaining baseflows in streams and rivers, thereby supporting downstream aquatic ecosystems and maintaining hydrological continuity during dry seasons. However, the progressive decline of springs and depletion of shallow aquifers have severely tested the adaptive capacity and resilience of Himalayan communities, highlighting the urgent necessity for integrated, scientifically grounded, and socially inclusive water management strategies [10].

A growing body of literature has examined springshed-related issues across multiple dimensions, including policy development, management and governance, protection and rejuvenation strategies, conservation approaches, technological interventions, vulnerability and livelihood assessments, gender roles, and the involvement of non-governmental organizations [3,11,12,13,14,15]. While these studies have significantly advanced awareness and practice-oriented understanding of springshed management, most investigations remain either qualitatively descriptive or sectorally fragmented, with limited integration of quantitative hydrogeological indicators that capture long-term system behavior and feedbacks. Consequently, there remains a critical gap in linking springshed hydrodynamics with socio-economic dependency, water-use patterns, and community resilience through a unified analytical framework.

Addressing this gap, the present research advances a novel, integrative approach by explicitly conceptualizing springsheds as coupled socio-hydrogeological systems, wherein physical groundwater dynamics, water quality attributes, and patterns of human use jointly determine sustainability outcomes. Unlike previous studies that focus primarily on policy narratives or single-dimensional assessments, this study systematically combines in-situ hydro-environmental observations with socio-economic analysis, thereby contributing a more holistic and quantitative understanding of springshed functioning in the Indian Himalayan context.

Specifically, this research investigates the springshed phenomenon in Kalimpong (West Bengal) and Sikkim, focusing on its implications for sustainable development and community resilience. The primary objectives are to: (i) conduct in-situ assessments of the physical, environmental, and socio-economic characteristics of two distinct springsheds, such as Kalimpong I (Kalimpong) and Bhurung (Sikkim); (ii) compare and evaluate spring water quality across these springsheds; (iii) assess the utility, accessibility, and mobility of spring water for diverse domestic and livelihood activities; and (iv) identify key obstacles and vulnerabilities faced by residents in accessing and sustaining these water resources. Methodologically, the study adopts a mixed-methods framework integrating qualitative and quantitative approaches, including field-based hydrological surveys, environmental sample collection and water quality analysis, geographic information systems (GIS)-based physiographic mapping, household surveys, in-depth interviews, and focus group discussions. By triangulating hydrogeological indicators with socio-economic data, this research establishes explicit linkages between springshed dynamics, sustainable resource management, and community resilience. Through this integrative and quantitatively informed perspective, the study offers a distinct contribution by advancing springshed research beyond descriptive assessments toward a systems-based understanding that aligns hydrogeological theory with real-world sustainability and resilience challenges in the Indian Himalayan regions.

Figure 1. A conceptual framework illustrating springsheds as integrated hydrogeological–ecological–social systems driving water security, ecosystem sustainability, and community resilience across the Indian Himalayan region.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Selection of Study Area

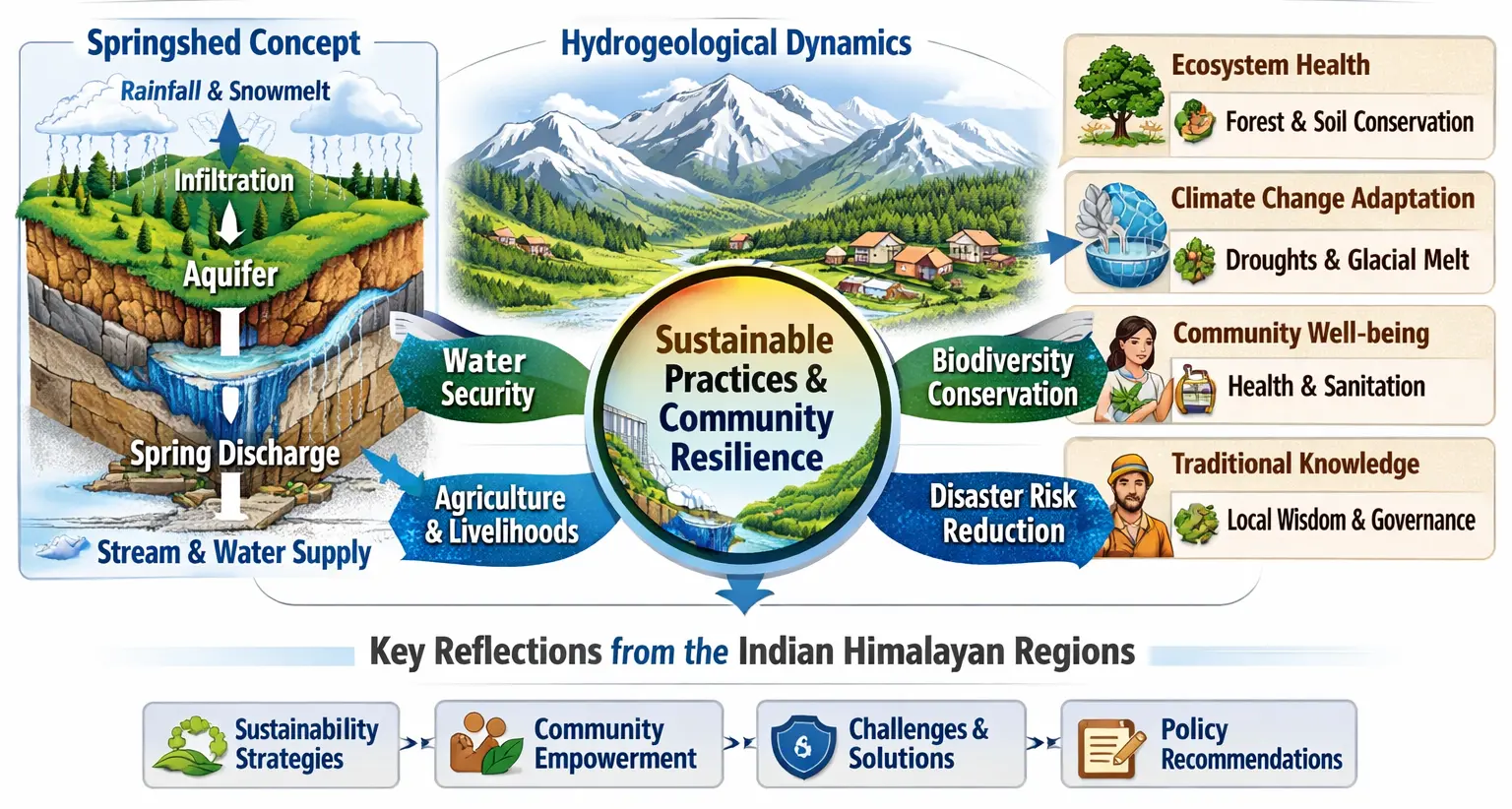

Himalayan regions are the source of numerous perennial rivers. Communities in this region largely depend on springs to meet their drinking, domestic, and agricultural water needs. The present study was carried out in two specific locations of the lower Himalayan region, namely, Kalimpong and Sikkim (Figure 2), which were purposively selected due to their large dependencies on springshed and spring water. Kalimpong district has an area of 1053.60 km2, with Kalimpong I block covering 360.46 km2 and Kalimpong municipality covering 9.16 km2 [16]. Bhurung is a village in the Pakyong area of Sikkim—it appears in the list of Gram Panchayat wards for the Central Pendam area of Pakyong district (1.6282 km2) [16].

The area is dotted with numerous natural springs, locally known as “Dharas”, which provide a continuous flow of fresh water. Kalimpong I and Bhurung (Sikkim) are roughly 43 km apart. The only water source available to the locals in these two areas is springshed water. Table 1 shows the locational information of these two places.

Figure 2. Location map of the study area at Kalimpong I and Bhurung; (a) India highlighting West Bengal state (in sky colour), (b) West Bengal (Sky clolour) and Sikkim (orange) states highlighting two study areas (location points), (c,d) The study sites Bhurung in Sikkim and Kalimpong I in West Bengal showing the location of springsheds, studied in this paper.

Table 1. General information on the study area sites at Kalimpong I (West Bengal) and Bhurung (Sikkim).

|

Dhara Name |

Latitude |

Longitude |

Altitude (mt.) |

Name of the Locality |

Name of GP/Municipality |

Block |

District |

State |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Common Dhara |

27.069205° N |

88.475693° E |

1059.42 |

Seed farm |

Dongra GP |

Kalimpong I |

Kalimpong |

West Bengal |

|

Bag Dhara |

27.067041° N |

88.475692° E |

1239.58 |

Bag Dhara |

Kalimpong Municipality |

Kalimpong I |

Kalimpong |

West Bengal |

|

Chisopani Dhara |

27.072724° N |

88.492838° E |

1017.56 |

Sindebong |

Sindebong GP |

Kalimpong I |

Kalimpong |

West Bengal |

|

Kholcha |

27.216927° N |

88.532327° E |

1147.19 |

Bhurung |

Central Pendam GPU |

Bhurung |

Pakyong |

Sikkim |

|

Paderi |

27.207326° N |

88.532327° E |

1159.23 |

Bhurung |

Central Pendam GPU |

Bhurung |

Pakyong |

Sikkim |

|

Devi |

27.207325° N |

88.532343° E |

1196.43 |

Bhurung |

Central Pendam GPU |

Bhurung |

Pakyong |

Sikkim |

2.2. Sampling for Questionnaire Survey

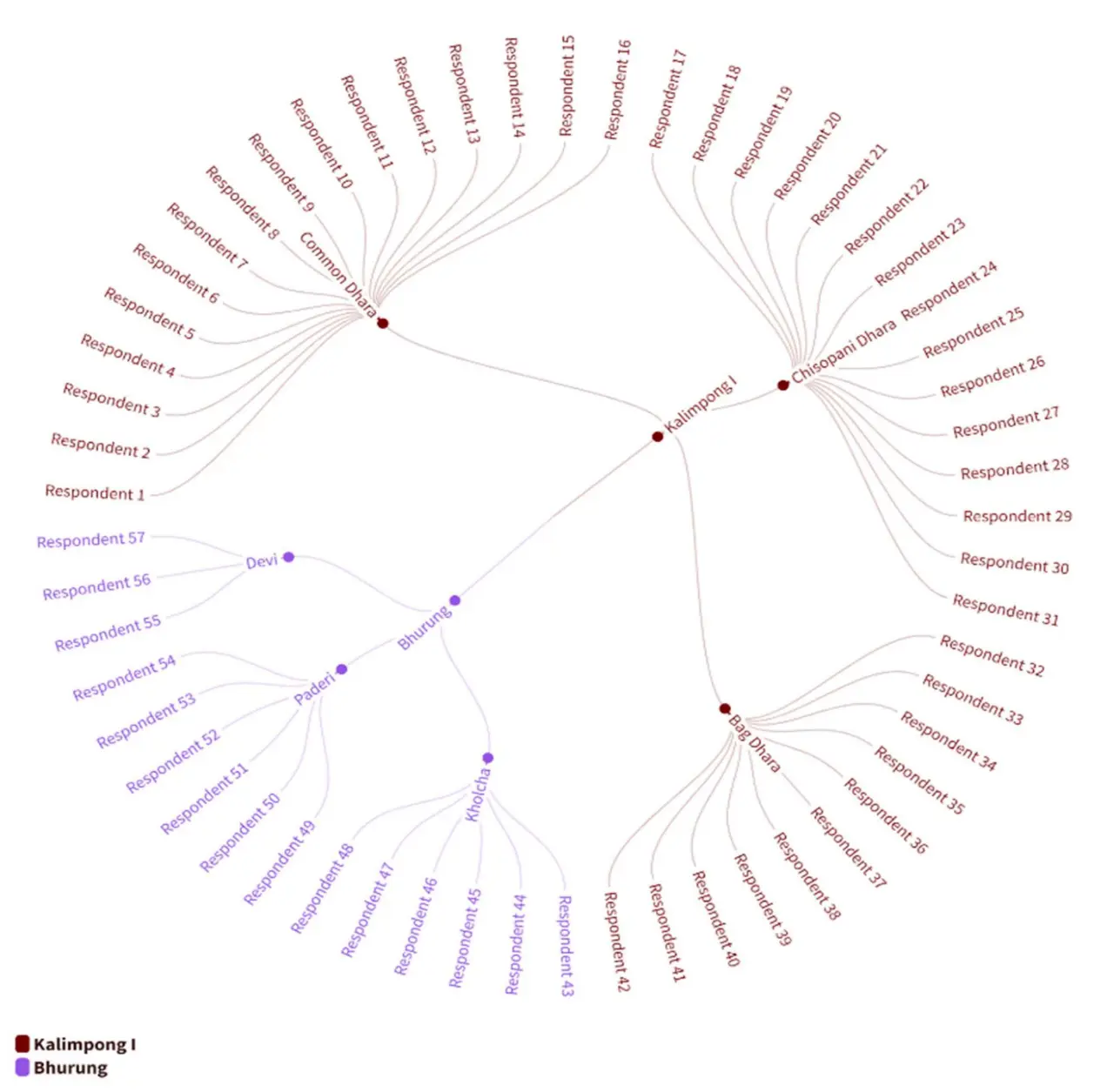

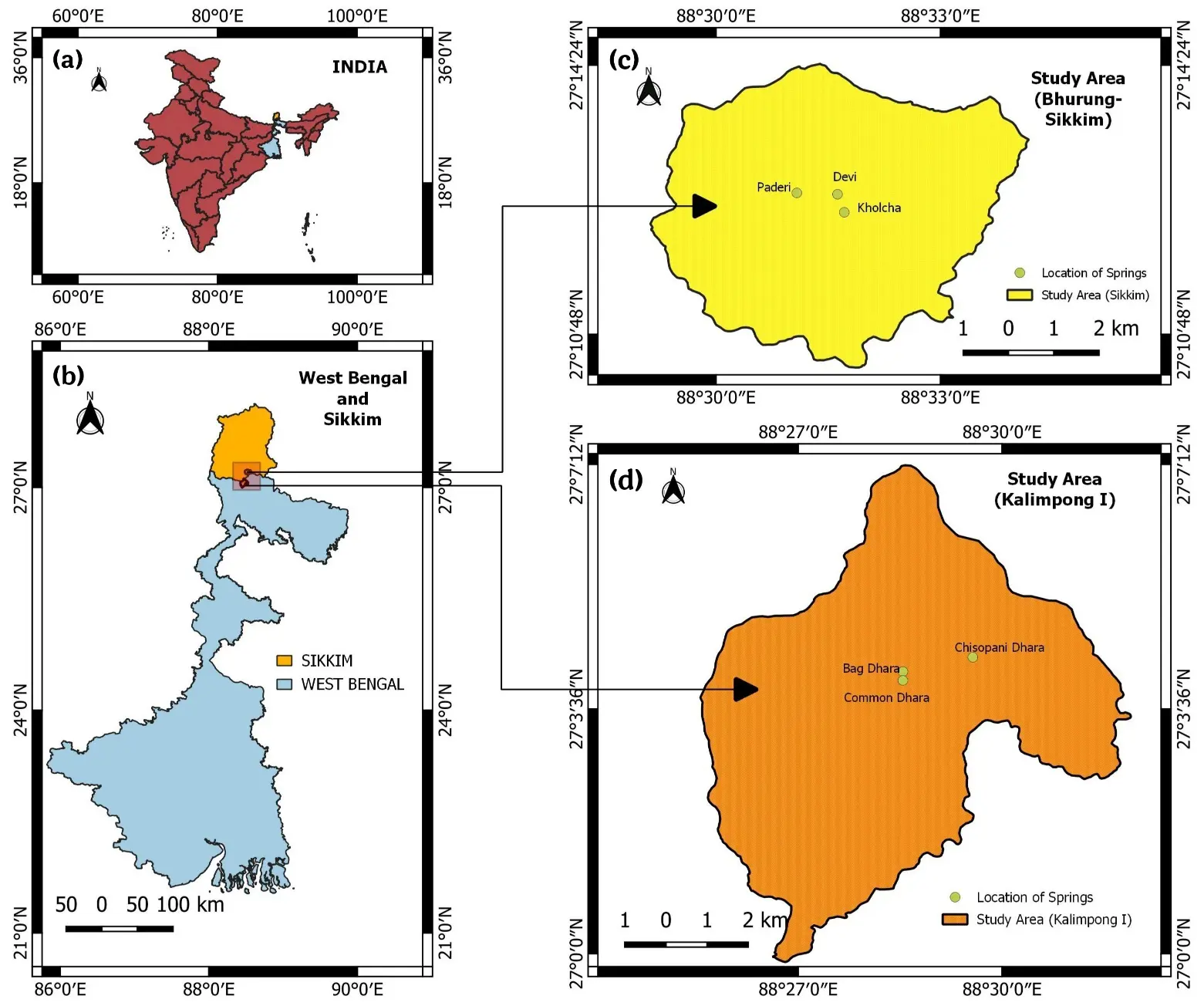

Kalimpong I represents an urban setting characterized by high population density and a compact settlement pattern, resulting in a relatively large number of households concentrated within a limited geographical area. In contrast, Bhurung is a rural village in the Pakyong region of Sikkim, marked by low population density and a dispersed settlement structure. For the present study, a total of 57 households were purposively selected for the questionnaire survey—42 from Kalimpong I and 15 from Bhurung (see Supplementary Table S1). Collectively, these households comprise 297 individuals who are entirely reliant on springshed-derived water for their domestic needs in the respective study areas (Figure 3).

2.3. Data Collection

2.3.1. Primary Survey Data

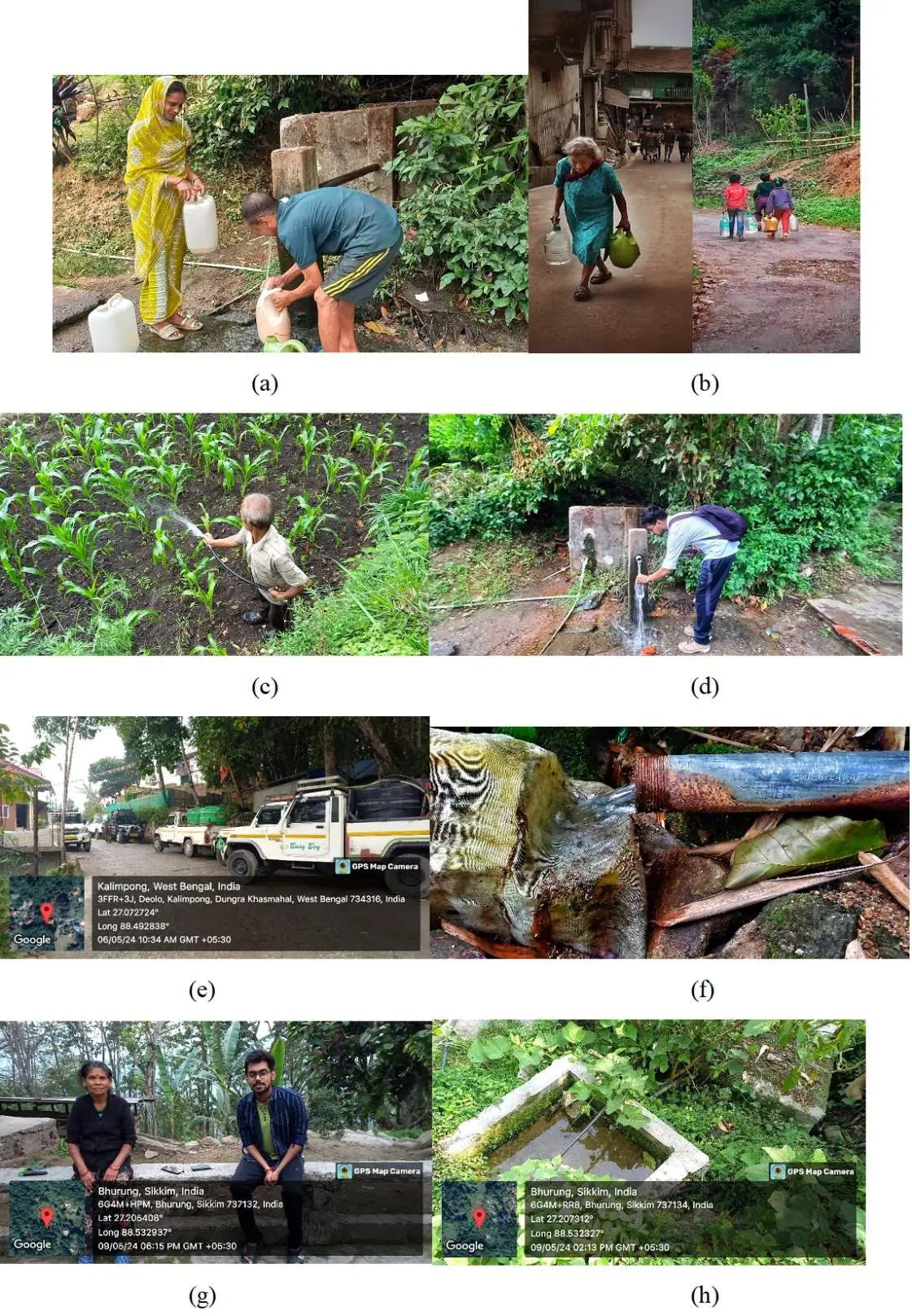

The study utilized a semi-structured interview schedule, divided into different blocks for collecting various types of primary data. The questionnaires were developed and stored in KoboToolbox. The data included identification blocks, family profiles, assets, water usage, commercial purposes, farming, non-agricultural labor, government/NGO intervention, and other aspects such as challenges, committee formation, requirements, and awareness campaigns. The data were collected separately for each domain, including information on identification, family profile, assets, water usage, commercial purposes, farming, and non-agricultural labor (Table S1). The interviews were conducted in the spring season, with a focus on the role of government and NGO intervention in the area. Figure 4 showcases some field photographs during the field sampling and data collection at Kalimpong and Bhuring.

Figure 4. (a) Collection of spring water by locals, (b) Bringing water from springs, (c) Usages of spring water in agriculture, (d) Collection of water samples for laboratory testing, (e) Water distribution in villages by local distributor, (f) Filtration of spring water by traditional method using a filtration cloth/sieve, (g) Interaction with respondent for perception survey, (h) Open and closed water reservoir for the collection and storage of spring water.

2.3.2. Data Basis and Climatic Context

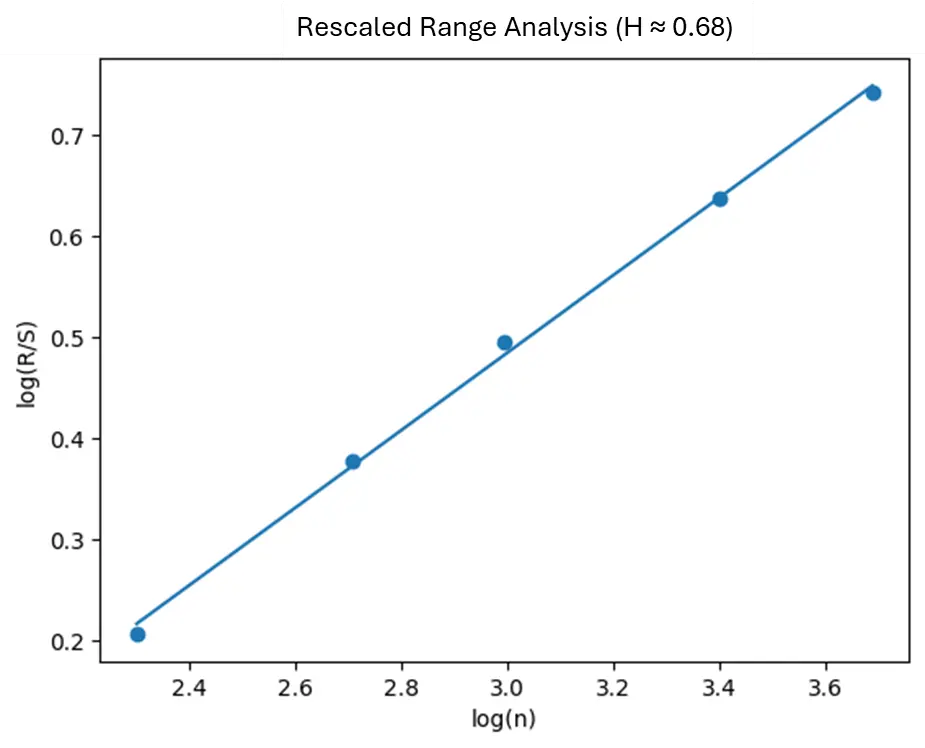

To quantify long-term memory in the climate system of the eastern Himalaya, the Hurst exponent (H) was estimated from long environmental time series representative of the Kalimpong–Sikkim region. Long-term climatic and hydrological time series were compiled from the ERA5 reanalysis (monthly temperature and precipitation at 0.25° resolution, 1990–2023) and India Meteorological Department (IMD) station-based rainfall records where available. Streamflow data were derived from regional Himalayan catchments draining the Teesta basin, supplemented by reanalysis-constrained reconstructions. Such datasets are appropriate for long-range dependence analysis because they integrate monsoon variability, orographic forcing, and regional land–atmosphere coupling.

2.4. Data Analysis

For a comprehensive understanding of the data analysis, we have presented the entire framework (Table 2) across three consecutive sections:

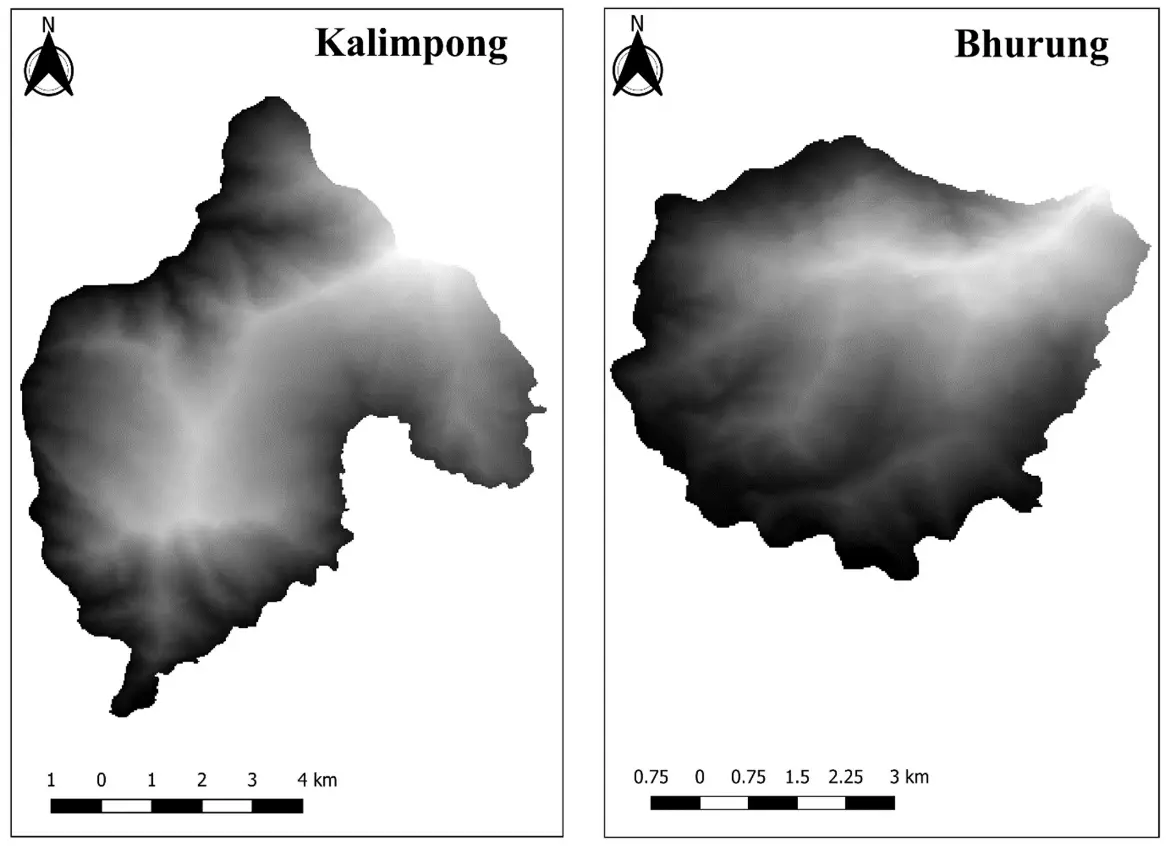

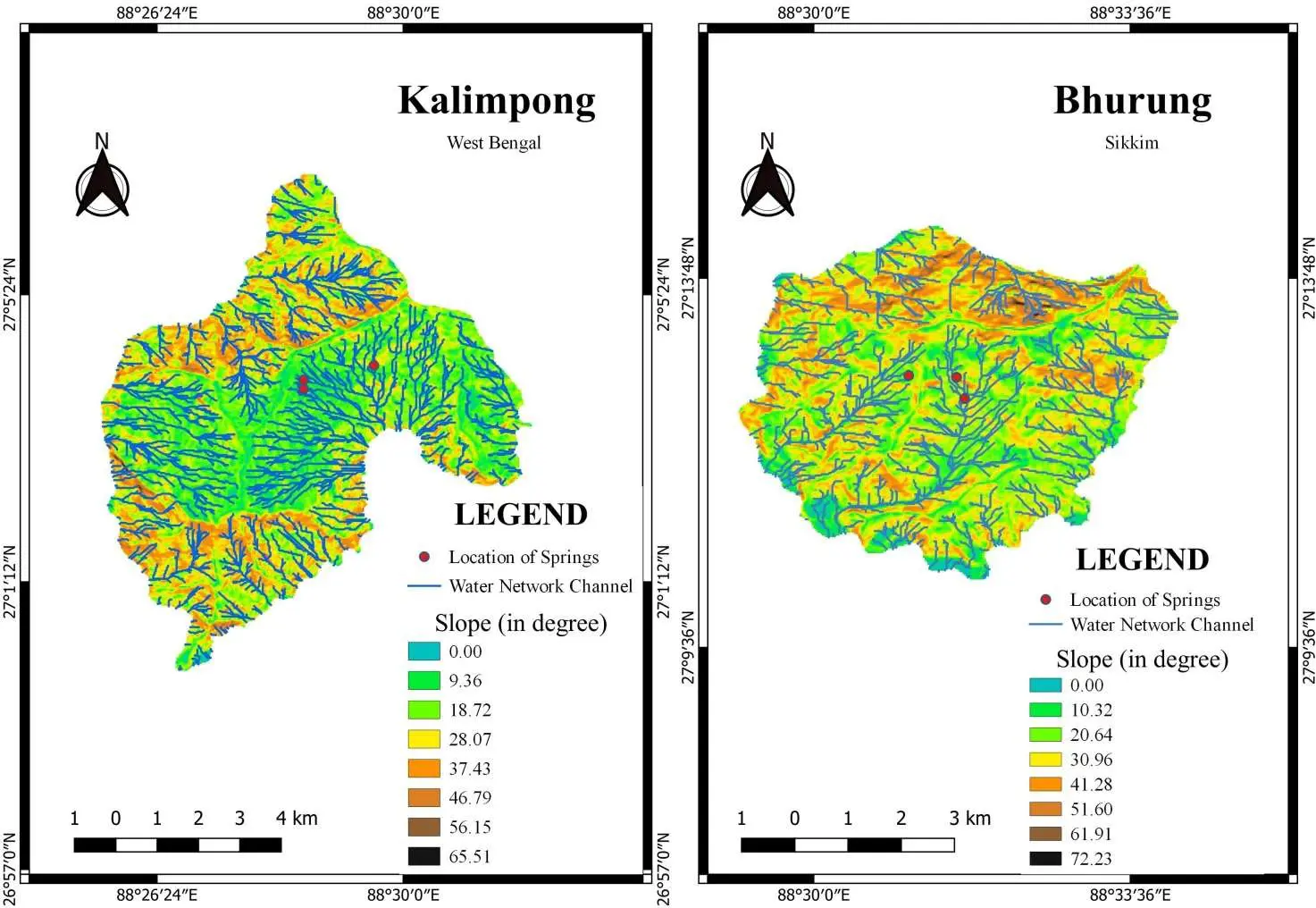

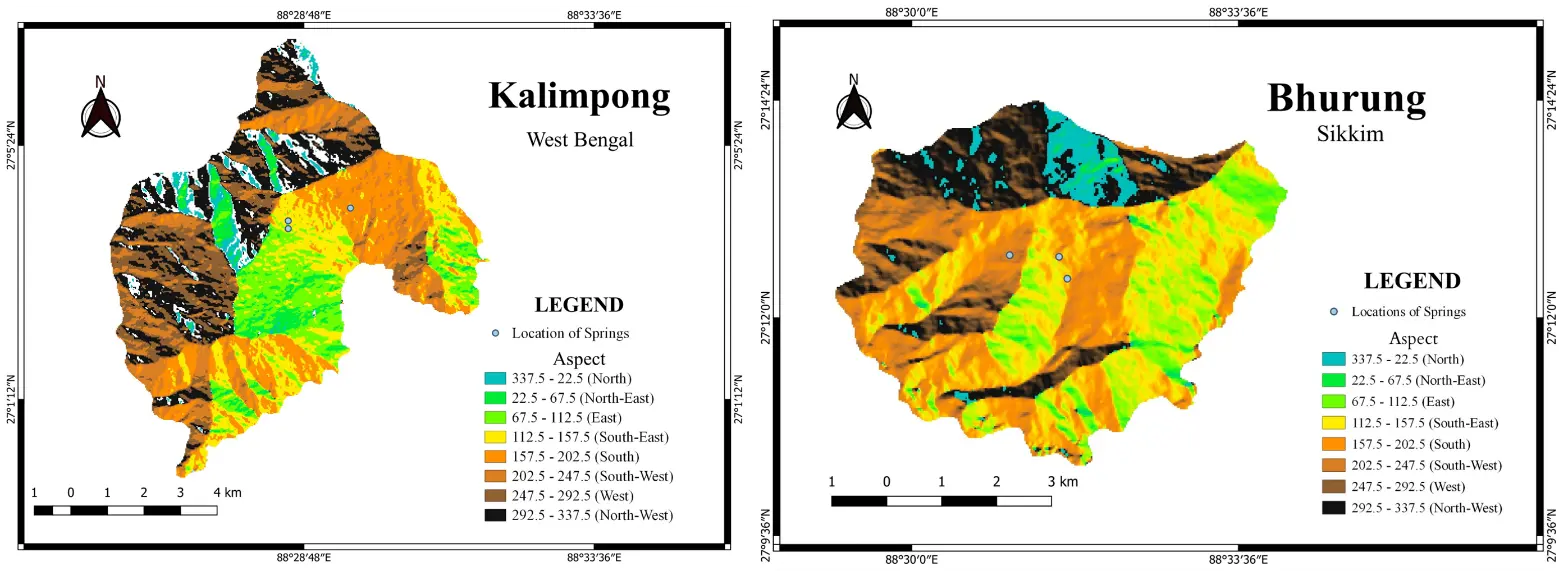

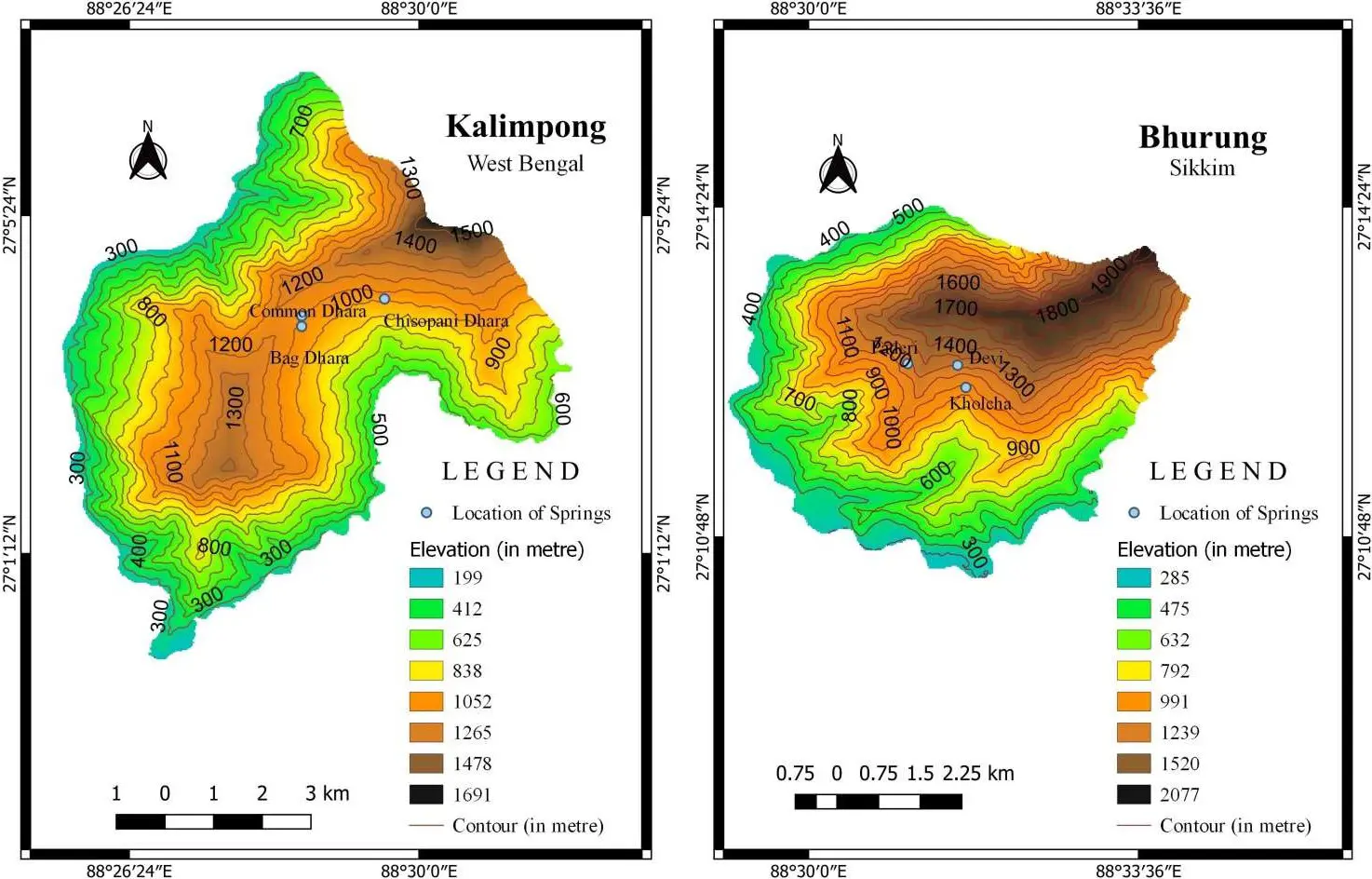

The first section highlights the physical aspects of the study area, which provide useful insights into the physiographic aspects of springshed locations at two different sites. For this, two Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM) Digital Elevation Model (DEM) satellite images with a spatial resolution of 90 m were downloaded from the USGS Earth Explorer website (https://earthexplorer.usgs.gov, accessed on 27 August 2024) and merged to create a single continuous DEM image. Furthermore, the merged DEM image was clipped by a mask layer (Figure 5) that delineates the area of interest (Kalimpong and Bhurung), and finally, clipped DEM images were used to analyze the study area’s elevation, contour, slope, aspect, and drainage network. All processing steps, including merging, clipping, and analysis, were performed using the QGIS (version 3.16) software platform, which provides robust DEM manipulation and spatial analysis tools.

The second section provides a brief overview of the environmental quality of the springshed water at two sites. It primarily deals with measuring water quality in the laboratory using total dissolved solids (TDS), pH, and electrical conductivity (EC) meters. We also discussed how rising temperatures and decreasing rainfall may have an adverse effect on spring water in these areas.

The third section focuses on the social aspects using specific tools that were used for the analysis, highlighting the detailed social composition of the people, their socio-demographic background, and the socio-economic aspect of the springshed. We used survey data for visualization in terms of tables and charts. During the survey, we used a case study technique to draw attention to the main challenges and issues that residents are facing in accessing spring water.

Table 2. Integrated physical, environmental, and social dimensions of springshed assessment, detailing data sources, extracted parameters, analytical rationale, and key limitations.

|

Aspects |

Data Source |

Parameters Extracted |

Rationale |

Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Physical |

SRTM DEM (90 m), GIS analysis (QGIS 3.16), field location data |

Elevation, slope, aspect, drainage pattern, spring altitude |

To understand the physiography, flow direction, and hydrological setting of springsheds |

SRTM spatial resolution limits micro-scale hydrogeological interpretation; subsurface processes are not directly captured |

|

Environmental |

Laboratory analysis of spring water samples |

pH, TDS, Electrical Conductivity (EC) |

To assess potability, environmental quality, and suitability for domestic use |

Snapshot measurements; seasonal and long-term variability not quantified |

|

Social |

Household surveys, semi-structured interviews, FGDs (Kobo Toolbox) |

Demography, water dependency, collection frequency, livelihood linkage, access challenges |

To evaluate community dependence, resilience, and socio-economic dimensions of springsheds |

Subjective responses; limited sample size; not fully generalizable |

Furthermore, monthly climatic data were aggregated to annual anomalies to minimize seasonality and to satisfy the assumptions of long-range dependence analysis. The H was estimated using classical rescaled range (R/S) analysis, which evaluates how variability in a time series scales with increasing temporal aggregation.

Let the environmental time series be defined as Equation (1):

|

```latexX=\left\{x\left(t\right),\text{ }t=1,2,\dots ,N\right\}``` |

(1) |

where $$x\left(t\right)$$ represents annual or monthly climate anomalies, and $$N$$is the record length.

The mean of the series is computed as Equation (2):

|

$$\overline{x}=\frac{1}{N}\sum _{t=1}^{N}x\left(t\right)$$ |

(2) |

Mean-adjusted cumulative deviations are then calculated as Equation (3):

|

$$Y\left(i\right)=\sum _{t=1}^{i}\left[x\left(t\right)-\overline{x}\right],i=1,2,\dots ,n$$ |

(3) |

where $$n\,$$denotes the window length.

For each window size $$n$$, the range is defined as Equation (4):

|

```latexR\left(n\right)=\mathrm{m}\mathrm{a}\mathrm{x}\left(Y\right)-\mathrm{m}\mathrm{i}\mathrm{n}\left(Y\right)``` |

(4) |

and the standard deviation is Equation (5):

|

$$S(n)=\sqrt{\frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^n[x(i)-\bar{x}]^2}$$ |

(5) |

The rescaled range is then computed as Equation (6):

|

```latex\frac{R\left(n\right)}{S\left(n\right)}``` |

(6) |

This procedure is repeated for multiple window lengths (e.g., $$n=10, 15, 20, 30, 40\,$$years), ensuring sufficient data points within each segment.

Finally, the H was estimated from the slope of the linear regression between $$\mathrm{l}\mathrm{o}\mathrm{g}\left(R/S\right)$$and $$\mathrm{l}\mathrm{o}\mathrm{g}\left(n\right)$$, following Equation (7):

|

```latex\mathrm{l}\mathrm{o}\mathrm{g}\left(\frac{R\left(n\right)}{S\left(n\right)}\right)=C+H\mathrm{l}\mathrm{o}\mathrm{g}\left(n\right)``` |

(7) |

where $$H\,$$is the Hurst exponent, and $$C\,$$is a constant. Linear regression on the log–log transformed variables yields the slope $$H$$, which quantifies persistence or anti-persistence in the climate signal.

3. Results

The results section is divided into three sections, each focusing on one of the three key study dimensions: physical, environmental and social aspects, and analysis of H.

3.1. Physical Aspect

Understanding the physiographic features of springwater locations is crucial to gaining insights into relief variations and drainage characteristics [17]. In this study, the GIS tool was primarily used for mapping and visualizing the Kalimpong I and Bhurung area’s topography and drainage. Figure 6 shows the elevation differences within and between the study sites using a DEM map with superimposed contour lines. The DEM map of the Kalimpong I area spans elevations from 199 to 1691 m, and the Bhurung area spans elevations from 285 m to 2077 m. On this map, the color gradient represents different elevation levels, with bluish tones indicating the lowest elevations and blackish hues signifying the highest points. This visual distinction aids in quickly identifying the topographical highs and lows within the region. The contour lines at 100-m intervals are superimposed on this color gradient, which further enhances the map’s ability to convey elevation changes.

Prominently marked on this map are three significant spring water sources: Common Dhara (1059.42 mt.), Bag Dhara (1239.58 mt.), and Chisopani Dhara (1017.65 mt.). Each of these springs is situated at a distinct elevation, which is crucial for understanding their hydrological behavior and potential resource management. This elevation map of Bhurung (Sikkim) also highlights three significant spring water sources Kholcha (1147.19 mt.), Paderi (1159.23 mt.), and Devi (1196.43 mt.), each marked with their respective elevations. The Maximum elevation is recorded in the extreme Northeastern corner (Kalimpong) and Eastern part (Sikkim) of the study site, and the minimum elevation is recorded in the Western, Southwestern, and Southern parts of both study sites. The proximity in elevation between the springsheds suggests that these springs might share similar hydrological characteristics and catchment areas, impacting their flow patterns and availability.

Figure 6. The elevation map on SRTM-DEM imagery shows elevation differences within and between the sites (Kalimpong I and Bhurung).

Furthermore, slope and aspect maps (Figure 7 and Figure 8) are critical physiographic resources that depict the orientation of degrees (slope) and the direction or inclination of slopes (aspect), providing insights into the topographical characteristics of the springsheds. When combined with drainage network channels, these maps offer a comprehensive understanding of hydrological patterns and networks across the study sites (Figure 7). This is particularly important for the regions of the Indian Himalayas like Kalimpong I and Bhurung, where elevation and slope orientation significantly influence water flow and watershed development. In Kalimpong I, mostly the drainage networks flow in a south-westerly direction because of the location of the slope, which is primarily displayed on the aspect map (Figure 8). Common Dhara in Kalimpong I is a vital spring whose flow direction is influenced by the slope aspect. This spring, along with Bag Dhara and Chisopani Dhara, forms the primary water source in the Kalimpong I area. Bag Dhara and Chisopani Dhara further enrich the hydrological network, each contributing their water flows according to the aspect of the surrounding terrain. The orientation of slopes affects how water from these springs moves through the landscape, joining the network of streams and channels. The drainage networks in the Sikkim region flow in a southeasterly direction because of the location of the slope, which is mostly shown by aspect and slope maps. In the Bhurung area, Kholcha, Paderi, and Devi springs similarly contribute to the local hydrology. The aspect map reveals the directional flow of water from these springs, showing how they feed into larger channels and streams.

3.2. Environmental Aspects

Environmental testing of the quality of the springshed water indicates that at Kalimpong I, the spring water has a pH of 6.4, TDS of 175 ppm, and EC of 564.2 µs. Likewise, at Bhurung, the spring water has a pH of 6.65, a TDS level of 26 ppm, and an EC of 90.96 µs (Table 3).

Kalimpong: The pH of 6.4 falls below the BIS IS 10500:2012 acceptable range of 6.5–8.5, potentially indicating mil acidity that could affect taste, corrode infrastructure, or pose minor health risks with prolonged use [18]. TDS at 175 ppm remains well within the 500 mg/L acceptable limit (and far under 2000 mg/L permissible), signifying low mineral content suitable for drinking [19]. EC of 564.2 µS/cm corresponds appropriately to the TDS level (TDS ≈ 0.5 to 0.7 × EC), staying under 1000 µS/cm thresholds for good quality per CPCB guidelines [20], with no excess salts indicated. Treatment such as pH adjustment (e.g., via lime dosing) would bring it into full compliance.

Bhurung: The pH of 6.65 falls within the BIS IS 10500:2012 acceptable range of 6.5–8.5, avoiding health risks from acidity [18]. TDS at 26 ppm is well below the 500 mg/L limit (acceptable) and far under the 2000 mg/L permissible maximum, indicating excellent purity with minimal dissolved minerals [19]. EC of 90.96 µS/cm aligns with low TDS, confirming good conductivity and no excess salts, as values under 1000 µS/cm support potability per CPCB guidelines [20]. While TDS and EC are slightly higher in Kalimpong I springshed compared to Bhurung, both are within the limit for drinking purposes. Hence, the results suggest both the springsheds (Kalimpong I and Bhurung) serve good quality water for drinking purposes without any filtration, with Bhurung having the superior quality of water. Overall, the springshed water is safe for consumption and daily use, benefiting the community’s well-being. Perhaps regular monitoring and occasional treatment are necessary to maintain water safety and quality in Kalimpong-I.

Table 3. Water quality parameters of Kalimpong I and Bhurung.

|

Area |

EC (Electron Conductivity) |

TDS (ppm) |

pH |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Kalimpong I (WB) |

564.2 µs |

175.0 |

6.4 |

|

0.5642 mS |

|||

|

Bhurung (SK) |

90.96 µs |

26.0 |

6.65 |

|

0.09096 mS |

3.3. Social Aspects

The social and cultural dimensions of a place are intrinsically linked to the understanding of its population’s ethnic composition, a notion that is well-grounded in the theoretical framework of cultural ecology. This approach emphasizes the reciprocal relationship between a population and its natural environment, where the latter shapes the former’s cultural and social structures [21]. In the context of the present study, the multiethnic character of Kalimpong I and Bhurung reflects the region’s rich history and geographic position. The majority of the population in Kalimpong identifies as Gorkha or Nepali, with smaller groups such as Gurung, Sherpa, Bhutia, Rai, and Lepcha also represented [16]. Similarly, the ethnic composition of East Sikkim, where Bhurung is located, is dominated by Nepali-speaking communities, including Bahun, Chettri, Rai, Limbu, Gurung, Tamang, and Sherpa, alongside the indigenous Bhutia and Lepcha populations [16].

In social science research, it is critical to comprehend the socio-demographic backdrop since it offers a critical context for analyzing data and reaching valid findings. Age, sex, marital status, education, income, occupation, and family type are socio-demographic characteristics that impact people’s experiences, behaviors, and attitudes, which in turn affect study results. In the regions of Kalimpong I and Bhurung, the religious affiliations of the population are diverse, with Hindus comprising the majority at approximately 61%, followed by Christians at around 24%, and Buddhists at about 15% (Table 4). Despite these differences in religious background, a unifying factor among these communities is their reliance on spring water. This shared dependency highlights the importance of spring water as a vital resource for all residents, regardless of their religious affiliation. The necessity for effective management of spring water sources becomes evident, as it supports a diverse population and fosters a sense of unity and interdependence among different religious groups. Consequently, policymakers must ensure the equitable distribution of water resources to maintain access to clean and safe water for everyone in the region.

Table 4. Social aspects of the people of Kalimpong I (WB) and Bhurung (SK).

|

Variables |

Frequency Percent (%) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Kalimpong I |

Bhurung |

|||

|

Male |

Female |

Male |

Female |

|

|

Age (Years) |

||||

|

<30 |

35.4 |

47 |

54 |

57.6 |

|

30–60 |

60.9 |

51.2 |

43.2 |

42.4 |

|

>60 |

3.6 |

1.7 |

2.8 |

0 |

|

Education |

||||

|

Illiterate |

22.7 |

21.4 |

8.1 |

9 |

|

Upto Upper Primary |

47.3 |

46.1 |

35.2 |

30.2 |

|

Upto Higher Secondary |

23.6 |

26.5 |

45.9 |

42.4 |

|

Graduation and above |

6.4 |

6 |

10.8 |

18.1 |

|

Employment Status |

||||

|

Employed |

93.48 |

43.9 |

67.7 |

58 |

|

Unemployed |

6.52 |

56.1 |

32.3 |

42 |

Furthermore, all 42 households in Kalimpong I primarily depend on springsheds as their main source of water, while supplementary sources are used to meet additional domestic demands. For instance, 26 households (61.9%) receive springshed water through professional distribution systems, commonly supplied in 1000-L drums locally referred to as “PHE water”, which offer relatively higher storage capacity. In addition, only 2 households (4.76%) rely on professional small-scale water suppliers (Figure 9), highlighting the presence of multiple, though unevenly utilized, water access pathways within the area. In contrast, all households in Sikkim (n = 15) rely exclusively on springshed water (Figure 9), reflecting a more uniform dependence on this natural water source and limited access to alternative water supply options. The disparities in infrastructural development and water supply management between the two regions are reflected in their water dependency. Although Kalimpong I exhibits a more varied strategy for obtaining water, combining natural springs with additional sources such as PHE water and outside vendors, the respondents of Bhurung, Sikkim, are exclusively dependent on springshed water.

The data on the quantity and frequency of water collection from the Common Dhara and Bag Dhara in the Kalimpong I block provides insights into the water usage patterns of the households in these areas. The analysis of water collection patterns from the Common Dhara and Bagdhara at the Kalimpong I block reveals distinct preferences among the households. At the Common Dhara, which serves 16 households, water collection is distributed across various quantities. Households collecting 10 L, 15 L, and 20 L do so four times per day (Table 5), indicating that these moderate amounts are manageable and sufficient for daily needs, without overburdening the carriers. In contrast, those collecting 25 L make three trips per day, suggesting a preference for fewer trips with larger quantities, balancing effort and necessity. There is also a single household collecting more than 25 L in one trip, highlighting an approach that minimizes trips at the expense of carrying a larger load at once.

Table 5. Frequency of collecting water per day from the Common Dhara and Bag Dhara.

|

Name of Dhara and Quantity of Water Collection (Litter) |

Frequency of Collecting Water Per Day |

|---|---|

|

Common Dhara (n = 16) |

|

|

10 |

4 |

|

15 |

4 |

|

20 |

4 |

|

25 |

3 |

|

>25 |

1 |

|

Bagdhara (n = 11) |

|

|

10 |

1 |

|

15 |

1 |

|

20 |

8 |

|

25 |

- |

|

>25 |

1 |

3.4. Analysis of H

The rescaled range analysis reveals a clear power-law relationship between $$R/S$$ and window size $$n$$, as evidenced by the approximately linear trend in the log–log plot. This confirms that the environmental time series from the Kalimpong–Sikkim region does not behave as uncorrelated white noise but exhibits scale-dependent memory. Using the representative rainfall example, the regression of $$\mathrm{l}\mathrm{o}\mathrm{g}\left(R/S\right)$$ against $$\mathrm{l}\mathrm{o}\mathrm{g}\left(n\right)$$ yields a positive slope corresponding to the H. Although individual numerical estimates depend on the exact dataset and aggregation scale, the observed scaling behaviour is consistent with persistent dynamics (H > 0.65) (Figure 10) commonly reported for monsoon-dominated mountain climates.

The estimated Hurst exponent for annual precipitation lies in the range 0.65–0.75, indicating statistically significant long-range dependence. This confirms that monsoon rainfall anomalies tend to persist over multi-year timescales rather than behaving as independent stochastic events. Furthermore, near-surface air temperature shows even stronger persistence, with H > 0.7. This reflects the combined influence of land–atmosphere feedbacks, snow–albedo effects at higher elevations, and the integration of large-scale warming trends into regional climate variability. Streamflow series display multi-scale persistence with H ≈ 0.60–0.70, lower than temperature but comparable to rainfall. This moderated memory reflects the combined effects of precipitation forcing, groundwater storage, cryospheric contributions, and basin-scale routing processes. Overall, the hierarchy of persistence follows:

|

```latex{H}_{\text{Temperature}}>{H}_{\text{Rainfall}}\gtrsim {H}_{\text{Streamflow}}``` |

Figure 10. Log–log rescaled range (R/S) analysis of an annual hydro-climatic time series representative of the Kalimpong–Sikkim region, showing the scaling relationship between window length $$n\,$$and the rescaled range $$R/S$$. The linear fit in log–log space is used to estimate the Hurst exponent $$H$$, which quantifies long-term persistence and memory in the climatic signal.

4. Discussions

4.1. Key Synthesis of the Results

Understanding the socio-cultural and socio-economic dynamics of a community concerning water collection from spring sheds is a complex and multifaceted phenomenon. Theoretical frameworks from the fields of human ecology, social geography, and community resilience provide important lenses through which to analyze these dynamics. The age-sex distribution of a population is a key factor in shaping the roles and responsibilities within a community’s water collection activities, as highlighted in previous studies on spring-dependent communities [22,23]. This work builds on these foundations, providing further empirical evidence on how the categorization of the population into young/dependent, working (15–59 years), and aged groups influences the division of labor and collaborative efforts around water collection. Similar to findings from research in other spring-dependent regions [24,25], this study demonstrates the central role of the working age group, particularly men, women, and children, in the day-to-day water collection from the springshed. The involvement of multiple generations not only ensures household water security but also serves to transmit cultural knowledge and a sense of shared responsibility for natural resource management—a key tenet of community resilience theory [26].

By examining the intricate web of age-group dynamics, gender roles, and intergenerational knowledge sharing, this work provides a more holistic understanding of how socio-cultural and socio-economic factors shape the relationship between communities and their springshed resources. This nuanced perspective contributes to the growing body of literature on the social dimensions of spring shed management and community-based approaches to sustainable water governance.

The marital status of individuals within a community offers valuable insights into their way of life and domestic obligations. In the area under study, the marriage rate is significantly higher than the unmarried rate. This prevalence of marriage suggests the presence of a well-structured domestic framework where shared responsibilities play a crucial role in ensuring survival, particularly in a challenging ecological setting. Similar findings have been reported in other spring-dependent communities, where the institution of marriage and the subsequent division of labor within households are central to the resilience of these systems [27,28]. Married couples must collaborate effectively to efficiently manage their daily tasks, including the critical task of water collection from the springshed. The need to divide labor, especially in the collection of water from the springshed, emphasizes the importance of this collaboration. Both men and women actively participate in fetching and managing water, ensuring that their households have an adequate supply. This shared responsibility is vital for survival and highlights a positive societal aspect where mutual support is fundamental. Moreover, the equal involvement of both genders in water collection demonstrates a certain level of gender equality within the community, a pattern that has been observed in other spring-dependent regions as well [22,29].

This collaboration extends beyond mere survival and encompasses the protection and preservation of natural resources, akin to the nurturing care provided by Mother Nature. Previous studies have noted how the joint stewardship of spring resources by men and women fosters a sense of communal ownership and responsibility for the sustainability of these critical water sources [24,30]. Therefore, the high rate of marriage is not merely a demographic statistic but also an indication of a balanced distribution of roles and responsibilities, emphasizing gender equality. It signifies a community where both genders work together harmoniously, making equal contributions to household and environmental sustainability. This finding aligns with the growing body of literature that highlights the importance of gender-inclusive approaches to spring shed management and community-based water governance [31].

Education has a profound impact on various aspects of life, both directly and indirectly. Although the connection between education and the spring shed may not be immediately apparent, the influence of education is evident in significant and indirect ways. Educated individuals within the community are more likely to comprehend and address issues pertaining to climate change, landform degradation, and environmental sustainability [32,33]. Their ability to recognize and articulate these concerns is a testament to their increasing awareness, which stems from their educational background. This awareness is crucial for the future well-being of the community, as it enables them to anticipate and adapt to the evolving environmental challenges [34,35]. As residents become more educated, they acquire the skills and knowledge necessary to devise innovative solutions that alleviate the challenges associated with reliance on the spring shed [22]. Education empowers them to explore alternative water sources, enhance water management practices, and advocate for policies that safeguard their natural resources [36,37]. Consequently, the socio-demographic background plays a pivotal role in shaping the community’s interaction with the spring shed [28,31]. Educated individuals are better equipped to navigate the obstacles posed by environmental changes and resource scarcity. They can utilize their knowledge to enhance their economic stability and improve their overall quality of life [24,38].

Furthermore, the community’s occupational landscape is a critical determinant of survival, as residents’ livelihoods are categorized into various primary sectors such as business, government service, agriculture, and water collection from the spring shed [31,37]. Those engaged in business and government service enjoy more stable and predictable incomes, ensuring a greater degree of financial security [36,39]. However, a significant portion of the population relies directly on the spring shed for their livelihood, highlighting the vital role of natural resources in their daily lives [39]. In Kalimpong I, many individuals earn their primary income by collecting water from the spring shed and delivering it to households. This occupation is essential as it provides a means of earning a living in an environment where alternative economic opportunities may be scarce [28,30,40]. The spring shed is not merely a source of water but a crucial economic resource that sustains numerous families [30,41]. This dependence on water collection emphasizes the direct link between natural resource availability and occupational survival within the community [41].

Results suggest that the community of Bhurung is heavily reliant on the spring shed as the primary source of water for their agricultural activities, which serves as the main driver of their local economy. The ready availability and ease of accessing this natural resource have a significant impact on agricultural output, directly influencing the lives and livelihoods of numerous individuals within the region. Farmers in the Bhurung area utilize the spring water to irrigate their crops, ensuring food security for their households and generating income through the sale of agricultural goods. This reliance on the spring shed extends beyond the individual water users, permeating the wider agricultural society and economy.

The intricate connection between the environment and the local economy is vividly exemplified in the Bhurung region, where the spring shed’s function in providing water for both direct consumption and agricultural purposes is crucial. This interdependence highlights how natural resources shape job trends and livelihoods, ultimately determining the economic stability and resilience of the population. The spring shed is a vital resource that affects all aspects of local life, from personal incomes to agricultural prosperity, thus significantly impacting the overall livelihood and well-being of the inhabitants. The community’s reliance on this natural resource emphasizes its significance in shaping the socio-economic fabric of the region.

The socio-economic and socio-cultural aspects of residents in any area are significantly influenced by the socio-demographic characteristics of the population. This specific analysis of the current springsheds in Kalimpong I and Bhurung area exemplifies this connection. The relationship between springshed water and socio-economic perspectives is intricate and intertwined with various socio-demographic elements. Different age groups and genders exhibit a strong sense of community, with individuals of all ages participating in water collection, highlighting the community’s interdependence. Marital status underscores shared responsibilities within households, promoting gender equality through equal involvement of men and women in water-related activities. Education, while indirectly linked, plays a vital role in raising awareness and encouraging proactive measures to tackle environmental challenges. The occupation of individuals is directly influenced by the springshed, particularly in agriculture and water delivery services. Family structure also impacts water collection dynamics, with larger families requiring more coordinated efforts. Ultimately, springshed water serves as a critical resource and a central element that shapes and reflects the socio-economic landscape of these communities, influencing their survival, resilience, and development.

The water systems in Kalimpong I and Bhurung (Sikkim) are under significant environmental threats that pose risks to their long-term sustainability. These threats include the impacts of climate change, such as rising temperatures and shifting weather patterns that disrupt the hydrological cycle. Additionally, melting glaciers and snowpacks, along with increased evaporation rates, are changing the regular flow of water in these areas. Erratic rainfall patterns, characterized by intense rainfall followed by prolonged droughts, also disrupt the natural recharge of groundwater systems that supply the springs, leading to water scarcity. Temperature fluctuations contribute to enhanced evaporation from soil and surface water bodies, further reducing water availability. Furthermore, deforestation caused by logging, agricultural expansion, and urban development diminishes the protective functions of forests, which are essential for groundwater recharge and soil erosion prevention. This results in increased surface runoff, sedimentation, and clogging of springs. Human interference, such as unregulated construction and agricultural practices, directly impacts the sustainability of the spring sheds, putting the reliability of spring water at risk. In conclusion, the springshed water systems in Kalimpong I and Bhurung are facing a range of environmental challenges, including climate change, erratic rainfall, temperature variations, reduced forest cover, and human interference. These combined factors threaten the long-term viability of these crucial water resources. It is imperative to implement effective management and conservation strategies to address these issues and ensure the sustainability of the spring sheds.

The findings from Hurst exponent analysis confirm that hydro-climatic variability in the eastern Himalaya is governed by long-range dependence, challenging assumptions of randomness commonly embedded in conventional risk and trend analyses. Results further indicate that the Kalimpong–Sikkim climate system is characterized by pronounced long-range dependence rather than stochastic randomness, revealing that past states exert a measurable influence on future variability across hydroclimatic variables. Such persistence implies that climatic anomalies, once established, tend to endure over extended periods, enhancing the potential predictability of the system while simultaneously elevating the risk of prolonged extremes such as sustained droughts, extended wet spells, or persistent temperature anomalies. In this context, the H analysis emerges as a robust quantitative diagnostic tool, offering critical insights into the intrinsic memory and resilience of the regional climate system and strengthening the scientific basis for climate hazard assessment, impact modeling, and the development of more informed adaptation and risk mitigation strategies.

4.2. Challenges

The distribution of rainfall in the Bhurung and Kalimpong I area may alter as a result of climate change, with certain places perhaps enduring longer droughts and others seeing more severe rains. Springshed recharging and water resource management are made more difficult by this unpredictability. Storms, floods, and droughts are occurring more frequently and with greater intensity, which increases the risk of abrupt water shortages or damage to the water infrastructure necessary for managing spring sheds. It is challenging to maintain a consistent water supply due to irregular rainfall patterns, which affects both dependent settlements and natural springs. Because rainfall patterns are unpredictable, managing water resources becomes difficult, making long-term water management policies more difficult to implement. Warmer weather causes more water to evaporate from open water bodies and soil, which lowers the volume of water that springs may produce. Temperature variations have the power to change 115 regional climates, which in turn can have an impact on soil and plant health and groundwater recharge rates. In the mid-hills and low-hills, the precipitation varies from 1000 mm annually in the subtropical agro-climatic zone to around 3500 mm in the temperate zone. The Sikkim Himalayan region is blessed with high rainfall (annual average, 3000 mm), but an overwhelmingly high proportion of it falls during the summer monsoon season. This rainfall deficit has had adverse effects on the drinking water supply, irrigation in the rabi season, the production of vegetables, oranges, and other fruit crops, and Sikkim’s economy in general [42].

Deforestation is due to the establishment of development projects such as the construction of dams, the construction of roads, and the establishment of railway links [43]. The tree cover that prevents soil erosion is lost due to deforestation. When there are no roots to hold the soil together, a large amount of soil is lost during rainfall, which lowers groundwater recharge. Water seeps into the ground through healthy woods. The land’s capacity to absorb water is decreased when forests are destroyed because of the compacted soil and loss of organic matter. The loss of topsoil that is rich in nutrients inhibits the establishment of plants, which exacerbates erosion and lessens the efficiency of the springshed regions.

Furthermore, the amount of water that is available to meet the demands of an expanding population for industrial, agricultural, and residential use is becoming scarce. The changes in the area of tea gardens, rice cultivation, other crop cultivation, and built-up areas are directly related to spring water resources in such regions. Land occupied by these four categories increased from 29.5% to 36.2% between 1930 and 2010 [44]. A greater population may cause springs to lose their water supply if there is an excessive amount of water taken out of them. Water resources are largely consumed by agriculture. Springs are under pressure as a result of the growing demand for food and the corresponding need for irrigation. Water supplies are already under stress from increased domestic and industrial use, which exacerbates shortages.

Additionally, challenges occur due to insufficient storage and management of springshed water in these regions. Local communities may distribute water using traditional methods, which, given the rising demand, may be unfair or inefficient. Building water storage tanks makes it easier to collect and store excess water, increasing water availability during dry spells. Water efficiency and conservation can be improved by putting technology like drip irrigation, rainwater collection, and water filtration systems into practice. It is urgent and important to improve the catchment areas of the existing water reservoirs and add new water reservoirs in some places to meet the growing water demand [45]. It is essential to educate local communities about the value of sustainable practices and water conservation. Involving local people in conservation initiatives promotes better water resource management and protection.

4.3. SWOT Analysis

A SWOT analysis was performed (Figure 11), aiming at improving the understanding of the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats associated with the management and conservation of springshed water at Kalimpong I and Bhurung. The sustainability of springshed water depends on various factors, including land use practices, climate patterns, and human activities. Effective management of springsheds is essential to ensure a reliable water supply, protect water quality, and preserve the ecological integrity of spring ecosystems.

The purpose of this SWOT analysis is to evaluate the internal and external factors that influence the management of springshed water. By identifying the strengths and weaknesses within the current system, as well as the opportunities and threats in the broader context, stakeholders can develop strategic plans to enhance springshed conservation efforts. This analysis will provide a comprehensive understanding of the challenges and potential solutions for maintaining sustainable springshed water resources. Here is a detailed examination.

4.3.1. Strengths

-

-

Natural Purity: Spring-shed water often has high natural purity, being filtered through underground rocks and sediments.

-

-

Mineral Content: It usually contains beneficial minerals such as calcium, magnesium, and potassium.

-

-

Sustainability: Springs can be a renewable water source if managed properly, supporting a long-term water supply.

-

-

Taste and Health Benefits: The natural filtration process often gives spring water a superior taste and potential health benefits compared to other sources.

-

-

Ecosystem Support: Springs support local ecosystems and biodiversity, providing a habitat for various plant and animal species.

4.3.2. Weaknesses

-

-

Vulnerability to Contamination: Springs can be susceptible to contamination from agricultural runoff, industrial pollutants, and other human activities.

-

-

Seasonal Variability: The flow and availability of spring water can vary with seasons, potentially leading to supply issues during dry periods.

-

-

Limited Quantity: The volume of water that can be sustainably extracted from a spring may be limited.

-

-

Infrastructure Costs: Developing the infrastructure to capture, store, and distribute spring water can be costly.

4.3.3. Opportunities

-

-

Eco-Friendly Branding: Marketing Spring water as a natural, eco-friendly product can appeal to environmentally conscious consumers.

-

-

Tourism and Recreation: Springs can be developed as tourist attractions, promoting local tourism and recreational activities.

-

-

Sustainable Practices: Implementing sustainable water management practices can enhance the long-term viability of spring water sources.

-

-

Health and Wellness Market: Positioning Spring water as part of a health and wellness lifestyle can tap into a growing market trend.

-

-

Partnerships with Conservation Groups: Collaborating with environmental organizations can enhance the credibility and appeal of spring water products.

4.3.4. Threats

-

-

Environmental Degradation: Pollution, climate change, and over-extraction can degrade spring water quality and reduce availability.

-

-

Regulatory Changes: Stricter environmental regulations could impose new constraints on spring water extraction and usage.

-

-

Competition from Other Water Sources: Bottled water from other sources, such as purified or distilled water, can compete with spring water.

-

-

Economic Factors: Fluctuations in economic conditions can affect consumer spending on premium water products.

-

-

Water Rights Conflicts: Legal and regulatory disputes over water rights can pose challenges to accessing and utilizing spring water.

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

This study establishes that springsheds in the Indian Himalayan region operate not simply as biophysical water sources but as deeply integrated socio-ecological systems that sustain livelihoods, shape social organization, and underpin local resilience. By combining physiographic characterization, spring-water quality assessment, and socio-economic analysis, the research demonstrates how terrain, environmental conditions, and institutional arrangements interact to determine water availability, access, and vulnerability in Kalimpong I and Bhurung. The comparative analysis highlights a clear divergence between the two sites: Bhurung’s near-total reliance on springshed water heightens sensitivity to climatic variability despite comparatively better water quality, whereas Kalimpong I exhibits stronger adaptive capacity through a diversified water portfolio that integrates springs with Public Health Engineering supplies. These findings emphasize that resilience is governed not only by hydrochemical attributes but equally by source diversity, governance structures, and the equity of water distribution.

Beyond hydrological considerations, the study reveals the strong social embeddedness of springsheds in everyday life. Water collection and management practices organize gender roles, labor allocation, and livelihood strategies, while shared responsibilities across age and gender groups contribute to community cohesion and adaptive capacity. Community-led springshed management, therefore, emerges as a comprehensive sustainability pathway rather than a narrowly technical intervention. When reinforced by scientific inputs, traditional ecological knowledge supports soil stabilization, groundwater recharge, forest conservation, and biodiversity protection, underscoring a reciprocal relationship in which the ecological integrity of forested catchments is inseparable from the long-term sustainability of springsheds and the communities they support.

The incorporation of Hurst exponent analysis adds further rigor to these findings by placing local springshed dynamics within the wider hydro-climatic framework of the eastern Himalaya. The results demonstrate that regional hydro-climatic variability is dominated by strong long-range dependence rather than random fluctuations, implying that antecedent climatic conditions continue to shape future states. This inherent persistence suggests that once anomalies develop, they tend to persist over long timescales, improving predictability while concurrently elevating the likelihood of sustained extremes, including prolonged droughts or extended periods of excess rainfall. Within this framework, Hurst analysis emerges as a robust quantitative indicator of climate system persistence and resilience, underscoring the necessity of designing springshed governance and adaptation strategies that are attuned to the non-stochastic, memory-driven character of regional climate variability.

Overall, effective springshed management in Himalayan regions demands a multifaceted and collaborative approach that integrates livelihood security, social equity, environmental conservation, and an explicit recognition of long-term hydro-climatic persistence. Strengthening community-based governance, participatory decision-making, and adaptive management frameworks—grounded in both local knowledge and quantitative climate diagnostics—is essential under intensifying climatic and developmental pressures. The insights generated by this study are broadly transferable to other mountainous and spring-dependent regions worldwide, where localized water systems, shaped by coupled social, ecological, and climatic processes, remain central to human and ecosystem well-being.

Recommendations

Community-based governance: Establish locally representative water-user committees to manage springsheds, ensure equitable distribution, and institutionalize participatory decision-making. Build community capacity through training in sustainable water management, monitoring, and routine maintenance, supported by regular community-led inspections of springs and associated infrastructure.

Afforestation and soil conservation: Promote afforestation with native species such as the Dhokrey flower to enhance slope stability, soil moisture retention, and groundwater recharge. Encourage broader use of indigenous vegetation to strengthen catchment-scale soil and water conservation.

Infrastructure development: Develop and maintain rainwater harvesting and storage tanks to buffer seasonal scarcity. Construct small check dams and percolation structures to capture runoff and enhance recharge. Improve water distribution networks for equitable access and promote efficient irrigation technologies (e.g., drip and sprinkler systems) to optimize agricultural water use.

Awareness and capacity building: Conduct regular community meetings and educational programs on water conservation and springshed stewardship. Integrate water-sustainability concepts into school curricula and leverage local and social media to disseminate conservation messages. Organize community events, such as clean-up drives and tree-planting campaigns, to cultivate a shared conservation ethic.

Local-level water treatment: Improve drinking-water quality at spring outlets through low-cost filtration units, including simple pipeline filters. Encourage safe household practices such as boiling where necessary, while advocating for systemic recognition of spring-based water systems in local government water-security planning (Nowreen et al., 2023 [40]).

Collectively, these measures can substantially enhance springshed sustainability in Kalimpong and Bhurung and the other Himalayan foothills in these regions, securing reliable and high-quality water supplies while strengthening community resilience and ecological integrity.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be found at: https://www.sciepublish.com/article/pii/849, Table S1: Springshed-related village study segment: Questionnaire—household profile.

Statement of the Use of Generative AI and AI-Assisted Technologies in the Writing Process

The authors declare that they took the help of AI only to improve the clarity, wording, and phrasing of specific parts of the manuscript. No AI tools were involved in generating data, analyzing results, interpreting findings, or developing the study’s concepts.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Sw. Atmapriyananda, and the Narendrapur Campus, Swami Shivapurnananda of the Ramakrishna Mission Vivekananda Educational and Research Institute, for supporting this research. We also express our gratitude to Subrata Raha, Narayan Chandra Sahu, Lapka Tamang, Bishnu Chettri, Akashdeep Thapa, Sudipta Tripathi, Malini Roy Choudhury, Subhajit Banerjee, and Sreyashi Bhattacharyya for their invaluable support. We are also thankful to the people and the local government of Kalimpong I and Bhurung for their kind cooperation in the data collection of this research.

Author Contributions

S.T.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing—Original draft; S.D.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis and Interpretation, Visualization, Validation, Resources, Project administration, Supervision, Writing—Original draft, Writing—Review & editing; S.B.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing—Review & editing; S.M.: Formal analysis, Writing—Review & editing.

Ethics Statement

Ethical approval for this study was waived by the Institutional Research Ethics Committee of RKMVERI because the survey was anonymous, involved no sensitive topics, and carried no risk to participants.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available within the article or supplementary material [Table S1: Springshed-related village study segment: Questionnaire—household profile].

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

-

Patil S, Kulkarni H. Strategy Paper: A Guiding Note for Springshed Management in Uttarakhand; Advanced Centre for Water Resources Development and Management: Dehradun, India, 2019, pp. 112–120. DOI:10.13140/RG.2.2.26673.40800 [Google Scholar]

-

NITI Aayog. Report of Working Group I: Inventory and Revival of Springs in the Himalayas for Water Security. Department of Science & Technology, Government of India. 2018. Available online: https://dst.gov.in/sites/default/files/Final_NITI%20Report_Himalayan_Springs_23Aug2018.pdf (accessed on 20 August 2024).

-

Dass B, Sen S, Sharma A, Hussain S, Rana N, Sen D. Hydrological process monitoring for springshed management in the Indian Himalayan region: Field observatory and reference database. Curr. Sci. 2021, 120, 791–799. DOI:10.18520/cs/v120/i5/791-799 [Google Scholar]

-

Panwar S. Vulnerability of Himalayan springs to climate change and anthropogenic impact: a review. J. Mt. Sci. 2020, 17. 117-132. 10.1007/s11629-018-5308-4. [Google Scholar]

-

Wang N, Sun F, Koutsoyiannis D, Iliopoulou T, Wang T, Wang H, et al. How can changes in the human-flood distance mitigate flood fatalities and displacements? Geophys. Res. Lett. 2023, 50, e2023GL105064. DOI:10.1029/2023GL105064 [Google Scholar]

-

Daniel D, Anandhi A, Sen S. Conceptual Model for the Vulnerability Assessment of Springs in the Indian Himalayas. Climate 2021, 9, 121. DOI:10.3390/cli9080121 [Google Scholar]

-

Ministry of Jal Shakti. Springshed Management in the Mountainous Regions of India; Department of Water Resources, River Development and Ganga Rejuvenation; Ministry of Jal Shakti, Government of India: New Delhi, India, 2024. [Google Scholar]

-

NITI Aayog. Provision of Potable Drinking Water in Mountains through Participatory Springshed Management; Department of Drinking Water and Sanitation: New Delhi, India, 2020. [Google Scholar]

-

Tambe S, Kharel G, Arrawatia M, Kulkarni H, Mahamuni K, Ganeriwala A. Reviving Dying Springs: Climate Change Adaptation Experiments From the Sikkim Himalaya. Mt. Res. Dev. 2012, 32, 62–72. DOI:10.1659/MRD-JOURNAL-D-11-00079.1 [Google Scholar]

-

Kulkarni H, Pawar D. Hydrogeological Report on Ganesh Ghat Spring, Aundh; Advanced Center for Water Resources Development and Management (ACWADAM): Pune, India, 2021. [Google Scholar]

-

Bamola V, Ngullie A, Kumar R, Sharma A, Gautam A. Community-based spring shed development in response to drying springs in Nagaland. In Climate Change: Impact, Adaptation & Response in the Eastern Himalayas; Zothanzama J, Saitluanga BL, Lalnuntluanga, Lalzarzovi ST, Zonunsanga R, Eds.; Excel India Publishers: New Delhi, India, 2018; pp. 40–51. [Google Scholar]

-

Mahamuni K, Upasani D. Springs: A Common Source of a Common Resource; IASC-2011; Digital Library of The Commons, Indiana University: Bloomington, Indiana, 2011. [Google Scholar]

-

Rathod R, Kumar M, Mukherji A, Sikka A, Satapathy KK, Mishra A, et al. Resource Book on Springshed Management in the Indian Himalayan Region: Guidelines for Policy Makers and Development Practitioners; International Water Management Institute (IWMI): New Delhi, India; NITI Aayog, Government of India: New Delhi, India; Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC): New Delhi, India, 2021; 40p. DOI:10.5337/2021.230 [Google Scholar]

-

Prüss A. Review of epidemiological studies on health effects from exposure to recreational water. Int. J. Epidemiol. 1998, 27, 1–9. DOI:10.1093/ije/27.1.1 [Google Scholar]

-

Sen SM, Kansal A. Achieving water security in rural Indian Himalayas: A participatory account of challenges and potential solutions. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 245, 398–408. DOI:10.1016/j.jenvman.2019.05.132 [Google Scholar]

-

Chandramouli C, General R. Census of India; Office of the Registrar General and Census Commissioner: New Delhi, India, 2011. [Google Scholar]

-

Bagchi D, Kannaujiya S, Taloor AK, Sarkar T. A study on spring rejuvenation and springshed characterization in Mussoorie, Garhwal Himalaya using an integrated geospatial-geophysical approach. Remote Sens. Appl. Soc. Environ. 2021, 23, 100588. DOI:10.1016/j.rsase.2021.100588 [Google Scholar]

-

Bureau of Indian Standards (BIS). Indian Standard (IS: 10500, 2012) Drinking Water Specification (Reaffirmed 1993); Govt. of India: New Delhi, India, 2012. [Google Scholar]

-

Ministry of Drinking Water and Sanitation, Government of India. Uniform Drinking Water Quality Monitoring Protocol. February 2013. Available online: https://jaljeevanmission.gov.in/sites/default/files/guideline/UniformDrinkingWaterQualityMonitoringProtocol.pdf. (accessed on 20 August 2024).

-

Perfect Pollucon Services. CPCB Drinking Water Standards, Water Quality Standards & CPCB Guidelines. Available online: https://www.ppsthane.com/blog/cpcb-drinking-water-standards (accessed on 19 July 2025).

-

Saraswati B. (Ed.). The Cultural Dimension of Ecology [Culture and Development Series, No. 4]; Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts, D.K. Printworld: New Delhi, India, 1998; Volume xvii, 185p. [Google Scholar]

-

Pandit A, Pandey V, Batelaan O, Adhikari S. Depleting spring sources in the Himalayas: Environmental drivers or just perception? J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2024, 53, 101752. DOI:10.1016/j.ejrh.2024.101752 [Google Scholar]

-

Simanihuruk M, Sitorus H, Ismail R, Sitanggang T, Sihotang D. Community Resilience and Adaptive Strategies for Clean Water Scarcity in Salaon Toba Village, Lake Toba, Indonesia. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10335. DOI:10.3390/su172210335. [Google Scholar]

-

National Disaster Management Authority. National Disaster Management Guidelines: Community-Based Disaster Risk Reduction (CBDRR). Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India. 2024. Available online: https://ndma.gov.in/sites/default/files/PDF/Guidelines/CBDRR_Guidelines_Oct_2024.pdf (accessed on 19 July 2025).

-

Shaw R, Mallick F, Islam A. (Eds.). Disaster Risk Reduction Approaches in Bangladesh; Springer: Tokyo, Japan, 2013. DOI:10.1007/978-4-431-54252-0 [Google Scholar]

-

Berkes F, Ross H. Community resilience: Toward an integrated approach. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2013, 26, 5–20. DOI:10.1080/08941920.2012.736605 [Google Scholar]

-

Kulkarni H, Shah M, Vijay Shankar PS. Shaping the contours of groundwater governance. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2015, 4, 172–192. DOI:10.1016/j.ejrh.2014.11.004 [Google Scholar]

-

Srinivasan V, Lambin EF, Gorelick SM, Thompson BH, Rozelle S. The nature and causes of the global water crisis: Syndromes from a meta-analysis of coupled human-water studies. Water Resour. Res. 2012, 48. W10516. DOI:10.1029/2011WR011087 [Google Scholar]

-

Kulkarni H, Patil S. Competition and Conflict around Groundwater Resources in India; Forum for Policy Dialogue on Water Conflicts in India: Pune, India, 2017. [Google Scholar]

-

Tamang L, Chhetri A, Chhetri A. Sustaining local water sources: The need for sustainable water management in the Hill Towns of the Eastern Himalayas. In Water Management in South Asia: Socio-Economic, Infrastructural, Environmental and Institutional Aspects; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 123–131. [Google Scholar]

-

Ojha H, Neupane KR, Pandey CL, Singh V, Bajracharya R, Dahal N. Scarcity Amidst Plenty: Lower Himalayan Cities Struggling for Water Security. Water 2020, 12, 567. DOI:10.3390/w12020567 [Google Scholar]

-

Mili B, Katyaini S, Barua A. Enhancing adaptive capacity through education: A case study of rural mountain communities, Sikkim, eastern Himalaya India. In Climate Change Governance and Adaptation; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018, pp. 109–135. [Google Scholar]

-

Pant N, Hagare D, Maheshwari B, Rai SP, Sharma M, Dollin J, et al. Rejuvenation of the Springs in the Hindu Kush Himalayas Through Transdisciplinary Approaches—A Review. Water 2024, 16, 3675. DOI:10.3390/w16243675 [Google Scholar]

-

Rao N, Lawson ET, Raditloaneng WN, Solomon D, Angula MN. Gendered vulnerabilities to climate change: Insights from the semi-arid regions of Africa and Asia. Clim. Dev. 2019, 11, 14–26. DOI:10.1080/17565529.2017.1372266 [Google Scholar]

-

Maikhuri RK, Rawat LS, Negi VS, Faroouquee NA, Rao KS, Purohit VK, et al. Empowering Rural Women in Agro-Ecotechnologies for Livelihood Improvement and Natural Resource Management: A Case from Indian Central Himalaya: A Case from Indian Central Himalaya. Outlook Agric. 2011, 40, 229–236. DOI:10.5367/oa.2011.0052 [Google Scholar]

-

Menon A, Singh P, Shah E, Lélé S, Paranjape S, Joy KJ. Community-Based Natural Resource Management in the Central Himalayas: The Work of Doodha Toli Lok Vikas Sansthan; SAGE Publications India Pvt Ltd.: Gurgaon, India, 2007; pp. 196–241. DOI:10.4135/9788132101550.n6 [Google Scholar]

-

Huda M, Kumar R. Climate change and water resources of Himalayan region—review of impacts and implication. Arab. J. Geosci. 2021, 14, 1088. DOI:10.1007/s12517-021-07438-z [Google Scholar]

-

Berkes F, Colding J, Folke C. Rediscovery of traditional ecological knowledge as adaptive management. Ecol. Appl. 2000, 10, 1251–1262. DOI:10.1890/1051-0761(2000)010[1251:ROTEKA]2.0.CO;2 [Google Scholar]

-

Chinnasamy P, Prathapar SA. Methods to Investigate the Hydrology of the Himalayan Springs: A Review, IWMI Working Paper 169; International Water Management Institute (IWMI): Colombo, Sri Lanka, 2016; 28p. DOI:10.5337/2016.205 [Google Scholar]

-

Nowreen S, Misra AK, Zzaman RU, Sharma LP, Abdullah MS. Sustainability Challenges to Springshed Water Management in India and Bangladesh: A Bird’s Eye View. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5065. DOI:10.3390/su15065065 [Google Scholar]

-

Sharma G, Namchu C, Nyima K, Luitel M, Singh S, Goodrich CG. Water management systems of two towns in the Eastern Himalaya: Case studies of Singtam in Sikkim and Kalimpong in West Bengal states of India. Water Policy 2020, 22 (S1), 107–129. DOI:10.2166/wp.2019.229 [Google Scholar]

-

Rahman H, Karuppaiyan R, Senapati PC, Ngachan SV, Kumar A. An Analysis of Past Three Decade Weather Phenomenon in the Mid-Hills of Sikkim and Strategies for Mitigating Possible Impact of Climate Change on Agriculture. In Climate Change in Sikkim: Patterns, Impacts and Initiatives; Arrawatia ML, Tambe S, Eds.; Information and Public Relations Department, Government of Sikkim: Gangtok, India, 2012; pp. 19–48. Available online: http://www.sikkimforest.gov.in/climate-change-in-sikkim/climate%20change%20in%20sikkim%20-%20patterns%20impacts%20and%20initiatives.htm (accessed on 27 August 2024).

-

Rasool M, Johari GK. The process of development and landscape change in South Asia: An overview of transformation of Himalayan environment. Elem. Educ. Online 2023, 20, 3089–3103. Available online: https://ilkogretim-online.org/index.php/pub/article/view/2599 (accessed on 27 August 2024).

-

Prokop P, Płoskonka D. Natural and human impact on the land use and soil properties of the Sikkim Himalayas Piedmont in India. J. Environ. Manag. 2014, 138, 15–23. DOI:10.1016/j.jenvman.2014.01.034 [Google Scholar]

-

Ho LT, Goethals PLM. Opportunities and challenges for the sustainability of lakes and reservoirs in relation to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Water 2019, 11, 1462. DOI:10.3390/w11071462 [Google Scholar]