Advancing Youth Engagement in Agriculture: A Cross-National Comparative Policy Analysis and Framework for Sustainable Rural Development

Received: 25 November 2025 Revised: 15 December 2025 Accepted: 13 January 2026 Published: 19 January 2026

© 2026 The authors. This is an open access article under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

1. Introduction

Globally, the future of food security rests in the hands of a generation that is increasingly moving away from agriculture. While young people are often regarded as key drivers of innovation and sustainability in this sector, their participation—especially in rural areas—is hindered by numerous systemic barriers. The United Nations (UN) secretariat uses the terms “youth” and “young people” interchangeably. Although “youth” typically refers to the transitional phase between childhood and adulthood characterised by growing independence, Galstyan [1] emphasises that youth may also be conceptualised as a distinct social status encompassing specific roles, rituals and relationships. Consequently, definitions of youth by age vary among local and international organisations: the UN Secretariat defines youth as individuals aged 15 to 24, the UN-Habitat extends this range to 15 to 32, while the African Union Youth Charter sets it between 15 and 35 years [2].

In rural communities, agriculture is the primary driver of economic growth, with activities such as farming, livestock rearing, forestry, and fishing forming the foundation of their economies, providing the main source of livelihood for their inhabitants. Small family farms often characterise rural agriculture, though average landholdings differ between developing and developed countries. According to the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) of the United Nations, family farming is the predominant form of food and agricultural production globally, accounting for over 80% of total food value in both developing and developed nations [3]. While any economic activity in rural areas can contribute to rural development, the European Commission [4] underscores the importance of agriculture, supporting rural development through on-farm and off-farm activities. In regions reliant on agriculture, the broader rural economy—including healthcare, infrastructure and education—depends heavily on the sector’s profitability, explaining why agricultural development is central to most rural development initiatives.

A critical challenge for rural growth worldwide is rural-urban migration, particularly among youth, which is leading to the ageing of rural populations. The predominance of older farmers negatively affects productivity, as labour is the most immediate and essential factor for agricultural progress [5]. Moreover, older farmers face higher risks of farm-related injuries and fatalities [6]; for example, a study in North Carolina found that farmers aged 65 and older were three times more likely to die in tractor-related accidents compared to younger farmers [7]. Youth migration from rural areas not only reduces agricultural productivity but also exacerbates urban congestion, strains metropolitan infrastructure [8], and contributes to the expansion of informal settlements (slums) [9]. In many developing countries, this migration fuels youth unemployment, leading some young people to resort to criminal activities for survival [8,9,10]. Thus, promoting youth participation in agriculture, especially in rural areas, presents a viable strategy to address youth unemployment, rural demographic imbalances and urban population challenges.

This study explores youth participation in agriculture across four countries by examining their respective policy environments and identifying the barriers that young people encounter in the agricultural sector. The findings aim to illuminate the conditions faced by youth across varying national contexts in their entry into and retention in agriculture. Through a comparative case study analysis, this research will assess the degree to which youth are prioritised within agricultural and rural development agendas, thereby contributing to the broader discourse on sustainable development.

2. Materials and Methods

This study used an integrative literature review method to build a comprehensive understanding of youth participation in agriculture in Uganda, Cameroon, Nigeria and Italy. Insights from this review informed the development of a transferable conceptual framework used to guide the case study analysis. To structure this section effectively, we divided it into two distinct parts. In the initial section, we developed the conceptual framework, specifying and defining the core pillars affecting youth engagement in agriculture. In the subsequent section, our emphasis shifts to the case study analysis, highlighting the rationale for country selection and the cross-case analytical approach.

2.1. Conceptual Framework

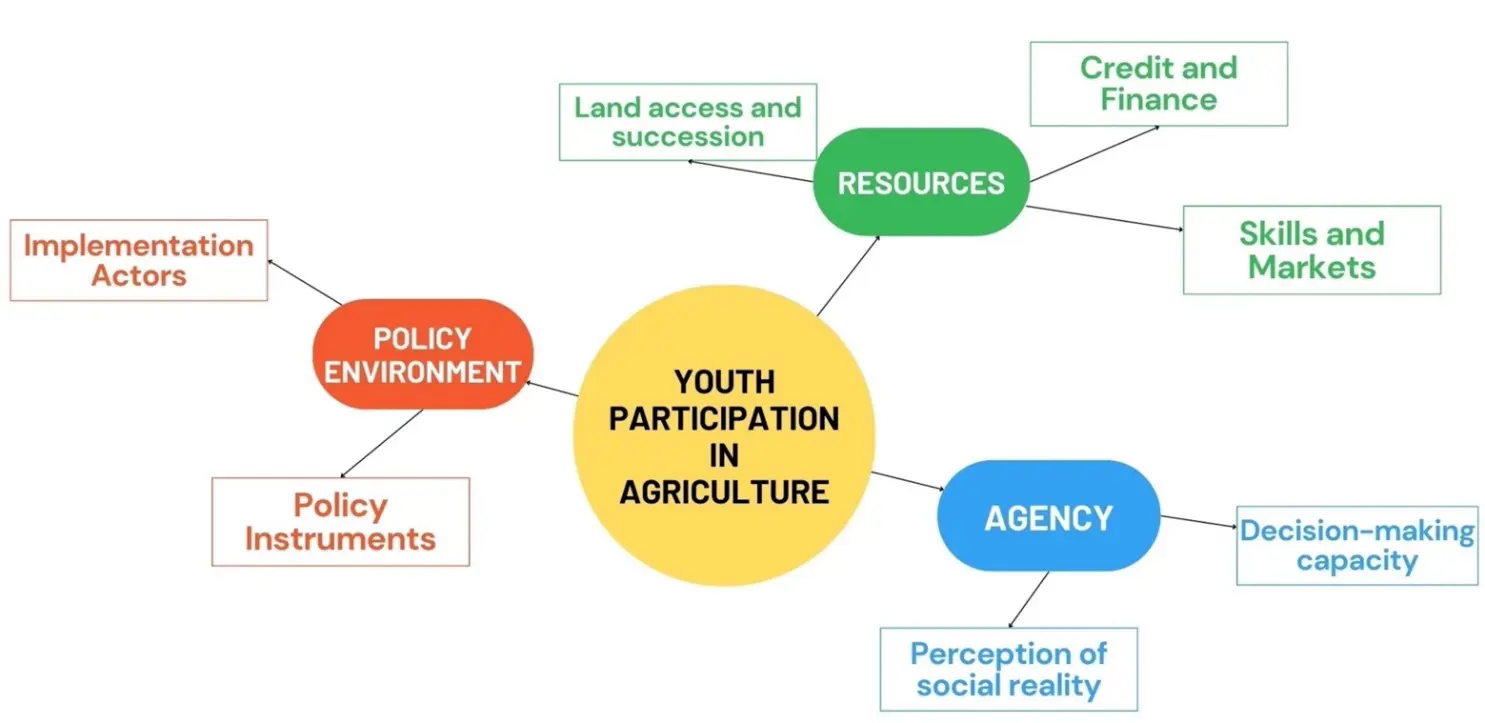

To better understand the dynamics facing young people regarding agricultural participation, the authors designed a conceptual framework specifically for this study, as shown in Figure 1. The integrated framework identifies three principal pillars of youth inclusion in agriculture: resources, policy environment and agency.

Figure 1. Integrated conceptual framework on youth participation in agriculture. Source: Developed by the authors (2025).

The resources pillar is further subdivided into land access and succession, credit and finance and skills and markets. Agriculture functions as a system of inputs, processes and outputs; thus, its efficiency largely depends on the quality and availability of inputs, which range from natural to technological and socio-economic. Land is the fundamental and irreplaceable resource for agriculture, especially in rural contexts. Credit and finance determine the intensity of input use, thereby impacting productivity through mechanisation, irrigation, fertilisation, and improved seed varieties. On the other hand, skills encompass the knowledge and expertise of agricultural workers, which are essential in informed decision-making throughout agricultural activities. Markets are vital to agriculture as they improve farmers’ incomes and drive economic growth.

Within this integrated framework, the policy environment pillar is elaborated to include implementation actors and policy instruments. Policy instruments are means of public intervention, including strategies, programmes, and legislation developed by public authorities and implemented to improve specific territorial situations [11]. Implementation actors refer to individuals or groups directly or indirectly affiliated with or affected by the policy process at any stage. These actors may include governments, Non-Governmental Organisations (NGOs), the private sector, civil society organisations, local communities, and individuals. Their role is to influence policy outcomes through either direct or indirect action.

The third and final pillar, agency, is a concept defined as the capacity of individuals to act independently and make choices that shape their lives and the social structures around them [12]. In this framework, we categorise agency as young people’s perceptions of social realities and their decision-making capacity.

2.2. Case Study Analysis

To analyse the context of youth participation in agriculture and rural development in Uganda, Cameroon, Nigeria and Italy, this study employed a cross-case analytical approach. The core pillars of the previously described conceptual framework (Figure 1) were systematically identified within each country context and subjected to comparative analysis. Particular emphasis was placed on the policy environment pillar and its intersection with the resources and agency pillars, enabling an in-depth examination of how policy dynamics influence youth engagement in agriculture. The analysis covered policy developments and their practical implications over the preceding ten-year period for each case study.

Case Selection Rationale

Uganda, Cameroon, Italy and Nigeria represent contrasting agrarian systems, governance capacities and policy environments, while sharing a strong reliance on family farming and a common policy concern with youth engagement in agriculture. Italy represents a high-income context characterised by institutionalised agricultural and rural development policies supported by the European Union. Uganda, Cameroon and Nigeria represent East, Central and West Africa, respectively, with differing youth demographics, land tenure arrangements and policy instruments targeted at prospective young farmers. These sub-Saharan African countries reflect diverse lower-income contexts, with Nigeria representing a large lower-middle-income country characterised by scale and federal governance. Uganda and Cameroon represent low- and lower-middle-income settings, respectively, dominated by smallholder and subsistence agriculture, where youth-focused interventions are often donor-driven. This variation enables the analysis to identify both common structural constraints and context-specific mechanisms shaping youth participation in agriculture.

3. Results

In this section, we present results from the four selected countries: Uganda, Cameroon, Italy, and Nigeria. For each case, we examine the current context of youth participation in agriculture, the key issues in agriculture and rural development, the prevailing policy environment and gaps in local-level implementation.

3.1. Case Study: Uganda

3.1.1. Introduction

With over three-quarters of its citizens under 35, Uganda has the second-youngest population in the world. Moreover, according to the United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF) [13], Uganda’s youthful population is projected to double in the next 25 years. Agriculture remains the dominant livelihood, employing roughly two-thirds of the total labour force, making the sector’s performance critical to Uganda’s rural development agenda. The World Bank (2023) reported accelerated economic growth in Uganda, with per capita income rising to approximately US$930 in the financial year 2021/2022, edging the country closer to the low-middle-income status threshold [14]. Despite this, Uganda is still facing challenges in bridging the gap between economic growth and addressing the high unemployment rate, especially among youth. According to the 2024 census, approximately 16.1% of youths under the age of 35 were unemployed [15].

In Uganda, a significant number of youths engage in agriculture, but most of their work remains informal, low-yielding and poorly paid, emphasising vulnerable working conditions [16,17]. The average age of Ugandan farmers is 54 years old [18], emphasising the need for young people to engage more with the sector. Although approximately 72% of Uganda’s land is arable, only 35% is cultivated, underscoring the agricultural sector’s potentialo generate meaningful employment [17]. The commercialisation of agriculture in Uganda faces several obstacles, including limited access to technologies, land tenure issues, underdeveloped transport infrastructure, and insufficient knowledge of value addition.

For young people, structural constraints such as limited access to land, credit, and modern inputs hamper their efforts. A key barrier to Ugandan youth participation in agriculture is their mindset, with many youths viewing farming as a last resort and migrating to towns in search of employment opportunities. Despite high levels of education among Ugandan youth—over 54% attending secondary school and 12% pursuing post-secondary education [19], 15.2% of graduates remain unemployed [20]. Other barriers, such as customary land tenure and gendered inheritance patterns, restrict ownership rights for both young women and men [21]. Despite these barriers, Uganda’s youth demographic potential could drive agricultural and national transformation if supported by coherent, youth-responsive policies and rural institutions.

3.1.2. Key Issues in Agriculture and Rural Development

-

-

Low productivity and vulnerability: Many young farmers operate on small family plots with rudimentary technology, resulting in low yields and limited incomes. According to the Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS), the average farm size in Uganda is 1.3 hectares, with over 67% of households having less than one hectare, emphasising a strong reliance on subsistence farming [22].

-

-

Access to resources: Land and finance are the principal bottlenecks. Only about 18% of rural youth report owning or controlling land, and few have access to formal credit due to a lack of collateral [21,22]

-

-

Skills and innovation gap: Training systems rarely emphasise agribusiness management or value addition. There are weak linkages between technical schools and the agricultural value chains.

-

-

Market infrastructure: Poor rural roads, limited storage and weak aggregation centres reduce farm-gate prices and discourage youth participation.

-

-

Policy fragmentation: Youth-related agricultural programs are numerous but poorly coordinated across ministries, causing duplication and inefficiency [23].

3.1.3. Policy Landscape and Key Actors

Uganda’s policy framework explicitly recognises the need to involve youth in agriculture. Some of the policies include:

-

-

National Agriculture Policy (2013): Sets the national goals for productivity and commercialisation, identifying youth as key stakeholders [16].

-

-

National Strategy for Youth Employment in Agriculture (NSYEA, 2017/2019): Provides a roadmap for youth integration through improved access to land, finances, skills and technology [23].

-

-

National Youth Policy (2001, revised 2016) and National Youth Action Plan (2015–2020): Aims to mainstream youth participation across all sectors [21].

-

-

Youth Livelihood Programme (YLP, 2014–present): Provides revolving funds to youth groups for small enterprises, with nearly half of these beinggricultural [24].

-

-

Parish Development Model (PDM, 2021): Seeks to channel multi-sectoral development support, including agricultural inputs and financial services, directly to parishes, with youth and women as priority beneficiaries [25].

Nationally, the Ministry of Agriculture, Animal Industry and Fisheries (MAAIF) oversees agriculture and implements NSYEA. At the same time, the Ministry of Gender, Labour and Social Development (MGLSD) manages youth-specific social and enterprise programmes, such as the YLP. Local governments are responsible for the extension and the on-ground rollout of the Parish Development Model (PDM) and other youth programmes. Additionally, youth organisations and the National Youth Council (NYC) mobilise participation and continue to advocate for youth inclusion in decision-making processes.

Development partners, such as the FAO, the World Bank, the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD), and the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), provide technical and financial support for youth participation in agriculture. Additionally, NGOs and private actors, such as agribusiness incubators, deliver capacity building, mentorship and market linkages [26,27].

3.1.4. Local Implementation and Gaps

At the local levels, programs such as the Youth Livelihood Programme and the Parish Development Model have expanded access to credit and enterprise support but continue to face persistent challenges. Targeting and inclusion remain problematic; for example, group-based funding models often exclude landless or female youth [24]. Moreover, financial sustainability is uncertain as revolving funds experience low repayment rates, and capacity constraints within local governments impede monitoring and technical support. Furthermore, coordination gaps among the MAAIF, MGLSD, and district administrations result in overlapping initiatives and inconsistent coverage [23].

These weaknesses produce a gap between strategic ambition and on-ground impact. Ugandan youth continue to cite a lack of land, capital and markets as reasons for their disengagement in agriculture [22,28]. Nonetheless, evidence from donor-supported youth cooperatives and agribusiness incubators shows that where local partnerships are strong, youth retention in family farming and agribusiness improves [29].

3.2. Case Study: Cameroon

3.2.1. Introduction

Agriculture is the engine of Cameroon’s growth and one of the most effective ways to alleviate hunger and poverty. Cameroon has a predominantly young population, with many youths entering the labour market annually. However, youth unemployment and underemployment remain high among young people aged 15 to 34 (8.9%), especially in rural areas [30]. Agriculture presents a viable pathway for youth employment, yet participation is limited due to structural and socio-economic barriers [31].

The agricultural sector employs approximately 43.4% of Cameroon’s workforce and contributes 17.4% of its Gross Domestic Product (GDP), 30% of its export revenue, and 23% of its added value [32]. It also plays a critical role in creating wealth for the 2 million households involved, especially in the country’s rural areas. The sector holds immense potential. Despite its importance, agriculture in Cameroon faces challenges that hinder youth participation and long-term sustainability [33].

Cameroon’s agricultural sector is diverse, producing both export and domestic commodities such as cocoa, coffee, cotton, bananas, palm oil, tobacco, tea, pineapple, corn, millet, sorghum, yams, potatoes, beans and rice. It has been determined that the livestock sector has been developed throughout the country and plays an especially important role in the northern region of the country [33]. Despite this diversity, agriculture remains largely underdeveloped, dominated by subsistence farming with low yields per hectare, limited adoption of modern technologies, and high vulnerability to climate and weather risks. Additionally, studies indicate that the mean age of farmers is approximately 44 years, with ages ranging from 18 to 76 years [34]. Despite Cameroon having relatively younger farmers than many other nations, the country still faces challenges in ensuring sufficient youth engagement for long-term agricultural sustainability. These limitations reduce the sector’s attractiveness and productivity, especially for young people seeking viable livelihoods.

Youth in Cameroon subsist on less than US $2 per day, with high rates of underemployment and vulnerable employment. There is also discouragement, especially among rural youth and young women, and the incidence of decent work deficits and poverty is particularly high among young rural women. Many agriculture graduates prefer off-farm roles (e.g., consultancy, marketing, teaching), leading to competition and limited job availability [35]. This high concentration of graduates in the tertiary sub-sector has led to heavy competition for the often-few jobs available, thus increasing the rates of youth underemployment and unemployment [36].

In addition, agriculture in its current form appears unattractive to young people that they are turning away from agricultural or rural futures [37,38,39]. This unattractiveness results from a growing divide between their economic, social, and lifestyle aspirations and the opportunities that agriculture offers [40]. Particularly for rural youth, their dream of a “good life” often lies far away from the rural areas.

A key impediment to youth involvement in agriculture has therefore been chronic government neglect of small-scale agriculture and rural infrastructure [38]. Sparse job opportunities, very low and unpredictable remuneration, and harsh working conditions; it is indeed not surprising that youth rarely mention farming as a “good job” [41].

Cameroon has significant agricultural potential, with 15% of its estimated 475,000 km2 of surface area being arable land. Moreover, the five agro-ecological zones (Sudanese-Sahelian, High Guinea Savannah, West highlands, Mono modal damp forests, and Bimodal wet forest) and fertile soils provide the country with a huge potential for food sovereignty [42]. As a result, agriculture can counteract an ageing farming population and contribute to food security and sustainability.

3.2.2. Key Issues in Agriculture and Rural Development

-

-

Agriculture remains subsistence-based with low productivity. It is characterised by low yields, limited adoption of modern technologies, and high vulnerability to climate and weather risks [36]. Farm sizes in Cameroon range from 0.5 to 2 hectares, with approximately 80% of the population engaged in smallholder family farms [43].

-

-

Farming is perceived as a low-status, labour-intensive occupation with poor remuneration and limited career prospects. This perception is reinforced by societal norms and educational experiences that associate agriculture with punishment and drudgery [40].

-

-

Young people face significant barriers to accessing land, insurance, and agricultural inputs. Land tenure systems are restrictive, particularly for women, and financial institutions are hesitant to support youth due to a lack of collateral and financial literacy [44].

-

-

Skills mismatches between education and job market demands, limited access to credit and resources for starting businesses, and a lack of investment in infrastructure, particularly in rural areas, limit entrepreneurship [30].

-

-

The agricultural sector suffers from poor market access, weak pricing mechanisms, and underdeveloped marketing channels. Post-harvest losses and limited transformation capacity further reduce profitability, discouraging youth participation [31].

-

-

Bureaucratic hurdles, such as lengthy business registration processes and poor rural infrastructure (e.g., distant hospitals and markets), make agricultural entrepreneurship difficult. Youth often work in informal, unstable conditions with little or no pay [45].

-

-

Considering the peculiarities of the development of agricultural production in rural households, it is characterized by small size of land plots, the prevalence of informal economic relations; use of manual labour of family members or as contributing family workers without pay; natural exchange, due to the underdevelopment of market infrastructure, increased access to borrowed financing sources; low level of involvement of commodity producers in value added chains [42].

-

-

In Cameroon, agricultural growth relies more on expanding farmland than on improving productivity, and is hindered by limited access to modern inputs, weak infrastructure, insufficient policy support and socio-political unrest, which has disrupted agricultural value chains and rural livelihoods [30].

-

-

The small-scale agriculture sector is experiencing significant negative impacts from climate change. Greater variability of precipitation and increased intensity of extreme weather events (e.g., drought or flood events) result in unpredictable growing conditions that can significantly impact yields and farm productivity [46].

3.2.3. Policy Landscape and Key Actors

There are several public policies in favour of rural youth employment that are being supported by the country’s ministerial departments, such as:

-

-

PEA-Jeunes (Program de Promotion de l’Entrepreneuriat Agropastoral des Jeunes): Promotes renovation and development of vocational training in the agriculture, livestock and fisheries sectors [31].

-

-

PAIJA (Program d’Appui à l’Installation des Jeunes Agriculteurs): This program offers a specific funding mechanism for employment and self-employment support for young entrepreneurs [47].

-

-

PAJER-U: The program offers intensive market gardening crop cultivation activities and providesntensive livestock farming training to youths (pig rearing and poultry) [31].

-

-

FONIJ (National Youth Integration Fund): The program provides support for the renovation and development of vocational training in the agriculture, livestock, and fisheries sectors [31].

-

-

Tree Year Special Youth Plan (TYSYP): Initiated by the President of the Republic of Cameroon, TYSYP aims to curb youth unemployment and boost rural development, map youth aspirations, strengthen program coherence, and develop local support structures such asMPJ (Multifunctional Youth Promotion Centres) [30].

The actions of these structures include financial, technical and material support for young people who wish to establish their own businesses [48].

The Ministry of Youth Affairs and Civic Education (MINJEC), through the TYSYP, aims to facilitate and accelerate the socio-economic integration of young people through productive entrepreneurship. The plan targets young people aged 15 to 35, helping them establish their own businesses or become established in the community through the second-generation Pioneer Villages and Economic Clusters of Cameroon (VPC-Cam) [30]. The Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development (MINADER) implemented a modernisation strategy focused on four pillars:

-

-

Mechanisation: The ministry acquired 1000 tractors (funded by the African Development Bank) and established 200 community mechanisation workshops (2021–2024).

-

-

Input Access: Improved access to fertilisers and pesticides for professional organisations, distributed 1700 tons of certified rice seeds in 2023, increased subsidies for inputs from 20% to 50% and offered low-interest loans (up to 15%) for machinery and processing equipment.

-

-

Seed Quality: The Ministry collaborated with the Ministry of Scientific Research to promote high-yielding varieties such as NERICA rice and hybrid maize.

-

-

launched the National Strategy for Innovative Development of the Rice Industry: focused on expanding irrigated land, restoring infrastructure, training producers, and modernising processing and marketing [49].

Informal Policy Structures and Community-Level Initiatives, such as the National Development Strategy 2020–2030 (NDS30), which aims to promote structural transformation of the Cameroonian economy and endogenous, inclusive development [50]. Also, the International Finance Corporation (IFC) organises a Private Sector Day that highlights strategies to boost private sector development, focusing on IFC’s investment and advisory services projects in Cameroon [51]. Additionally, the World Bank Group (WBG) Country Partnership Framework (CPF) for the financial year 2025 to 2029, focuses on supporting the country’s Vision 2035 [45]. Farmer Cooperatives and Youth Associations also play a crucial role. Furthermore, Green Innovation Centres (GICs) have been created as part of the “One World, No Famine” Initiative, an important instrument for sustainable agriculture in Cameroon. The purpose of these centres is to promote innovation in agriculture, to increase the safety of agricultural products and food, and to develop sustainable value-added chains in the country’s agricultural sector. An important role is assigned to the National Agricultural Advisory Council to increase the production of scientific and information support for managerial decisions of farmers and to expand scientific research in the field of agriculture.

3.2.4. Local Implementation and Gaps

Programs like TYSYP show limited impact on women’s employment, indicating a need for gender-sensitive approaches [30]. However, youths still face difficulties in accessing land, inputs, and credit at the local level. There is also weak coordination among stakeholders and a lack of performance monitoring, which hinders effective delivery [52]. Informal institutions and cultural attitudes affect youth motivation and participation, requiring targeted sensitisation and education [53]. Also, policymakers should increase public spending on agriculture, particularly in underfunded areas such as R&D and extension services, to boost productivity and drive technological adoption. Strengthening extension services is especially important in regions with significant information gaps that hinder the uptake of modern agricultural inputs. Ultimately, coordination challenges across multiple agencies and stakeholders lead to fragmented efforts and inefficiencies. Encouraging collaboration, establishing clear communication channels, and defining roles and responsibilities can improve coordination efforts [50].

Public policies are central to addressing critical issues such as infrastructure development, education, healthcare, poverty alleviation, and economic diversification. When effectively formulated and implemented, these policies can accelerate the country’s development and improve its citizens’ standard of living. However, systemic challenges such as access to land, gender disparities, and weak local implementation can be addressed to unlock the sector’s potential fully. Strengthening policy coordination, investing in youth-led agribusiness, and promoting inclusive rural development are essential for sustainable agricultural transformation.

3.3. Case Study: Italy

3.3.1. Introduction

Italy has approximately 1.1 million farms, covering around 12.5 million hectares of the country’s agricultural area. With these numbers, it is no surprise that Italy’s agricultural sector and agri-food system are strong contributors to the country’s economy, accounting for around 2% and 15% of the GDP, respectively [54]. Moreover, the majority of Italian farms are small and family-owned, with an average land size of 11 hectares. Agriculture in Italy is characterised by a demographic imbalance, with a greater concentration of farm managers aged 60 or more and a relatively small share of managers under 45. This generation gap is framing the policy priority of “generational renewal” at the European Union, national and regional levels [55].

While agriculture no longer employs the majority of the workforce as in the past decades, rural and intermediate areas continue to rely on family farms for livelihoods and local economies. Approximately 53% of the Italian population resides in rural or intermediate areas, with the agriculture and forestry sectors being key economic drivers. However, Italy’s rural areas face challenges in terms of depopulation, basic services, infrastructure, and quality of life [54]. Regarding youth involvement, new patterns like interest in short supply chains, organic and niche products, agritourism and tech-enabled start-ups are attracting many young people to the sector. Despite these enablers, structural barriers, such as fragmented holdings, land costs, unequal regional development and climate risk, persist and determine who can successfully establish a farm business [54].

Italy’s policy response has therefore emphasised targeted support for “first installation” young farmers via the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) Young Farmer measures embedded in the CAP 2023–2027 architecture. The Italian CAP strategic plan aims at enhancing the competitiveness and sustainability of the country’s diversified agriculture and rural areas. It aims to bolster policies that favour young farmers, who are generally more open to innovation and digitalisation than older farmers. In fact, 1.03 billion euros have been set aside to help young farmers face new challenges and attract new young entrants into agriculture. This plan is a convergence of the former regional rural development programmes, with regions continuing to play a key role in implementing regional development initiatives [56]. Additionally, a national law was enacted in 2024 (Law No. 36/2024), further signalling the country’s will to promote youth entrepreneurship in agriculture through a national co-financing fund and complementary support measures [57]. Nevertheless, the implementation record shows uneven regional results and continuing constraints that undermine the transition from start-up grants to sustainable rural livelihoods.

3.3.2. Key Issues in Agriculture and Rural Development

-

-

Generational renewal and structural heterogeneity: Italy’s farming population is ageing, and many farms are family-run, often small and fragmented. This creates real urgency to enable generational succession while also modernising family farms to remain competitive [55,58].

-

-

Land access, affordability and succession: Land prices in productive areas and peri-urban zones are high in Italy, with fragmentation and inheritance practices complicating first-time access. Although land banks, lease markets and coordinated succession tools are present in some regions, they are inconsistent nationally [59].

-

-

Multilevel Policy Complexity: Because grants are implemented through regional schemes, eligibility conditions and viability criteria create administrative complexities for applicants, leading to uneven opportunities across territories [56].

-

-

Skills, innovation, and the digital divide: While innovation and short-chain models attract many young farmers, digital adoption and agritech use are uneven, with southern and mountainous regions showing lower digital readiness. Moreover, climate shocks and market volatility further amplify entry risks for young farmers [60,61].

3.3.3. Policy Landscape and Actors

The majority of Italian policies to promote youth participation in agriculture are currently being guided by EU legislation, such as:

-

-

CAP Young Farmer measures (CAP 2023–2027): Offers support for first installations and start-up aid. This is implemented via the CAP strategic plan and regional Rural Development Programmes (RDPs). For example, the SRE01 grant applications, which are a specific intervention within the CAP strategic plan called the “Insediamento dei giovani agricoltori” (settlement of young farmers), offer grants to young people either establishing or taking over an agricultural business.

-

-

Law No. 36/2024: National law encouraging the establishment and permanence of young people and generational turnover in the agricultural sector, in compliance with European Union legislation [57].

-

-

Regional Rural Development Programmes (RDPs): Italian regions operationalise SRE01 through region-specific calls for applications, specifying business plan requirements and award amounts.

-

-

Instituto di Servizi per il Mercato Agricolo Alimentare (ISMEA) and other national financing schemes: In 2024, ISMEA programs offered non-repayable contributions for innovations and guarantees to facilitate credit for young farmers. The “Fondo Innovazione” (Innovation Fund) supports technological innovation through grants for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and young farmers. Meanwhile, the ISMEA guarantee provides a credit guarantee for agricultural enterprises, with higher coverage for young farmers. The ISMEA “Generazione Terra” program, aimed at providing young farmers with access to land, opened applications in October 2024. Specifically, this program was addressed to young agricultural entrepreneurs under 41 years old who intend to expand the surface area of their business by purchasing land bordering or functionally useful to the surface area already owned by the agricultural business. It also targeted experienced young start-uppers under 41 years old who intended to buy land for agricultural use. Additionally, young people under 35 with no prior agricultural experience who intend to buy land for new agribusiness initiatives were also targeted by this program.

The Ministry of Agricultural, Food, and Forestry Policies [62] handles national policy coordination, CAP strategic plan negotiations, and national funding oversight. On the other hand, regions and autonomous provinces design and implement calls for applications and sometimes co-financing grants. Additionally, farmers’ unions and youth wings, such as Coldiretti Giovani Impresa, mobilise applicants, provide peer networks, and engage in lobbying. Incubators, NGOs, agritech start-ups and private sector partners provide training, mentorship, market linkages and sometimes co-investment.

3.3.4. Local Implementation and Gaps

In Italy, implementation is active but uneven across regions. Northern and some central regions tend to have better-funded calls, stronger administrative capacity, and more integrated value-chain linkages, while many southern and mountainous regions still struggle with limited land availability, weaker markets, and lower digital penetration. For example, the Lombardy region benefits from denser markets, better infrastructure, active agribusiness clusters, and higher administrative capacity, which together increase the likelihood that grant recipients convert start-ups into viable businesses. The region also has programs that facilitate leasing and matching between retiring farmers and young entrants, thus reducing land access barriers, carried out by ISMEA [63]. On the contrary, the Calabria region faces constraints typical of southern and mountainous regions. In particular, cultural factors around land succession, small-sized farms, and limited off-farm employment affect youth decisions to remain in agriculture.

There are common implementation gaps across regions, such as insufficient follow-on finance and business scaling support, with grants covering only start-up costs and not working capital. Also, because grant sizes vary regionally, there is unequal access to opportunities. Furthermore, land access mechanisms are incomplete, with land-leasing markets and succession facilitation existing in pockets but not systemically. For farmers, market and climate shocks require insurance and risk-management tools, which are not uniformly available or affordable.

3.4. Case Study: Nigeria

3.4.1. Introduction

Agriculture remains a cornerstone of Nigeria’s economy, contributing approximately 25% to the Gross Domestic Product (GDP). In Nigeria, about 70% of the youth-dominated labour force lives in rural areas, and only a very few work in the non-farm sector, including small and medium-scale enterprises that depend directly or indirectly on agriculture. While their employment status may be seasonal or casual, most rural youths earn very low incomes and wages while working under unfavourable and unsafe conditions. The sector generates substantial foreign exchange earnings, particularly from the export of crops like cocoa, oil palm, rubber, and sesame seeds [64]. With declining revenue from the oil sector, agriculture has become a critical avenue for economic diversification [65]. At the same time, Nigeria faces a pressing demographic challenge. Of its 200 million people, about 60% are youths, and 55.4% of them are either unemployed or underemployed [66]. Given that most agricultural activities occur in rural areas, youth engagement in this sector is central to addressing unemployment and poverty.

Efforts to reduce youth unemployment both domestically and globally emphasise engaging young people in agriculture. In Nigeria, the average age of household heads engaged in farming is approximately 53 years, with data suggesting that many young people in their early 30s participate in agriculture as a part-time occupation [67]. However, it remains unclear whether youths who work in agriculture as their main occupation are better off than those who only engage in it as a secondary activity [68]. Since the late 1980s, Nigeria has rolled out several initiatives to draw young people into farming and agro-processing. For example, in 1986, the Federal Government set up the National Directorate of Employment to deliver vocational training for youth, while the Fadama program, launched in 1992, aimed to boost food self-sufficiency, cut poverty, and create rural employment opportunities for young people. More recently, in 2016, the Anchor Borrowers’ Program under the Agricultural Transformation Agenda began supplying finance for agricultural participation [69,70].

In addition, structured initiatives such as the Youth-in-Agribusiness (YIA) program provide hands-on training and support for young entrepreneurs across crop and livestock production and agro-processing. YIA encompasses schemes such as the Fadama Youth Empowerment Programme and the Ogun Women and Youth Empowerment Scheme (OGW-YES), which play key roles in rural youth development [71]. Digital tools are also emerging as game changers, offering web-based services and platforms that improve access to information, markets, and financial products, thereby modernising agriculture and making it more appealing to younger generations. Given this, sustained policy efforts assume that agriculture can serve as a viable primary livelihood for young Nigerians, yet empirical evidence comparing welfare outcomes between full-time and part-time youth engagement remains limited.

3.4.2. Key Issues in Agriculture and Rural Development

-

-

Barriers to youth involvement in Agriculture include weak incentives, insufficient agricultural skills and training, restricted access to finance, and poor perceived prospects in farming. Moreover, most Nigerian farms are smallholders, with a national average farm size of 0.85 hectares [72], undercutting the sector’s capacity to deliver attractive incomes to young people.

-

-

According to Babu et al. [73], youth continue to face several constraints, including limited technical know-how and resources, when venturing into agriculture, which deters their performance. Additionally, while many youths live on family plots, barriers to independent land access limit entrepreneurial entry and success.

-

-

The sector also faces low productivity, inadequate infrastructure, and poor access to modern inputs. Decades of neglect and an emphasis on subsistence farming for food security have constrained the sector’s expansion and competitiveness [74,75].

-

-

Overall, issues such as inconsistent and poorly coordinated policies, fragmented and overlapping institutions, weak value-chain development, rapid population growth and urbanization, limited adoption of production, processing, and storage technologies, transboundary animal diseases, pervasive poverty, climate change, conflict and insecurity, persistent gender disparities and inadequate inclusion of youth and women, fragile agricultural cooperatives and a lack of regular, standardized, and comparable data and information, are a detriment to agriculture and rural development in Nigeria [76].

3.4.3. Policy Landscape and Actors

Nigeria’s agricultural policy landscape comprises formal government-led frameworks and informal structures. Agricultural policy is framed around increasing food output, raising productivity, fostering rural development, and strengthening food security. Key policies supporting youth participation include:

-

-

The Agricultural Promotion Policy (APP) 2016–2020 and renewed agendas: A broad strategy by the Federal Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development (FMARD) to transform Nigeria’s farming sector. Its goals were to shift from subsistence to commercial farming, boost production and self-sufficiency in key crops, strengthen value chains, attract private investment, and create jobs while improving food security.

-

-

The Anchor Borrowers’ Programme (ABP): It was launched in November 2015 by the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) and was designed to provide cheap loans to smallholder farmers to boost the production of key staple crops, thereby reducing Nigeria’s dependence on food imports and creating employment [77]. Though the ABP was not originally youth-targeted, it has indirect implications for youth inclusion if they are organised as out-growers.

-

-

The National Agricultural Technology and Innovation Policy (NATIP): Emphasises integrating women and youth across value chains in line with existing Gender and Youth Policies of the relevant ministries. Planned measures include targeted capacity building, development of 21st-century skills, support for gender- and youth-friendly innovations and enterprises, promotion of modern farming practices, and strengthened links to finance. By actively involving women and young people, the policy aims to create one million new jobs within selected value chains, thereby institutionalising their participation under the 2019 Gender Policy and youth empowerment efforts [76]. There are also state-level youth employment interventions targeting agribusiness [73].

-

-

The Nigeria Economic Sustainability Plan (NESP) 2020–2023: It was launched to soften COVID-19’s economic impact and speed recovery. It included major agriculture measures to boost production and create jobs, targeting large-scale production of rice, maize, cassava, and poultry. The plan also aimed to expand value chains, improve finance for smallholder farmers, and encourage youth participation in agriculture.

-

-

IITA Youth Agripreneurs (IYA): The International Institute of Tropical Agriculture (IITA) launched this initiative in 2012, empowering Nigerian and other African youths to engage in agribusiness through a unique capacity development model [78].

Nationally, the Federal Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development (FMARD) implements agricultural policies, promotes agribusiness and oversees the development of the sector. The Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN), through initiatives like the Agricultural Credit Guarantee Scheme Fund (ACGSF) and the Anchor Borrowers’ Program (ABP), provides financing to farmers and agribusinesses, especially smallholder farmers. The Federal Ministry of Youth Development (FMYD) and other ministries design and implement youth-focused training and mobilisation programs. International partners such as the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR), FAO, IFAD, African Development Bank, IITA and the World Bank provide technical assistance and funding to the nation. The private sector and farmers’ organisations also play a critical role in facilitating agribusiness and market access.

3.4.4. Local Implementation and Gaps

Although Nigeria has introduced several agricultural policies and programs to promote youth participation, their implementation at the local level remains uneven. Initiatives such as the Youth-in-Agribusiness (YIA) program and Fadama schemes have provided hands-on training and empowerment opportunities in rural areas. Although the Anchor Borrowers’ Programme (ABP) has extended credit to smallholder farmers through state-level structures and cooperatives, it does not prioritise young people. Youth inclusion often depends on local organisations, such as cooperatives and youth groups, rather than on built-in targeting.

Key gaps persist, especially in weak institutional capacity at the state and local levels, leading to fragmented coordination and duplication of efforts. There is also inadequate input from local stakeholders, which leads to a misalignment of policies with the realities faced by youth in rural areas, contributing to the ongoing underutilisation of agricultural programs such as the Youth Empowerment in Agriculture Program (YEAP) and others that promise potential but are not thoroughly integrated into local agricultural practices [79]. Moreover, systemic challenges, including corruption, bureaucratic inefficiencies, and poor infrastructure, complicate policy implementation. Also, the lack of coordination between different agricultural training programs and community-based initiatives often results in fragmented efforts that fail to build a cohesive support network for rural youth [64].

4. Discussion

This discussion synthesises the findings from the four country cases to examine the structural, institutional and socio-cultural factors that shape youth engagement in agriculture. By comparing Uganda, Cameroon, Italy and Nigeria, this discussion moves beyond isolated national experiences to uncover the deeper patterns and contrasts defining youth-in-agriculture transitions across diverse contexts.

Italy has a well-developed multilevel policy structure comprising the European Union, national, and regional levels, which can mobilise substantial resources for youth participation in agriculture. Implementation is tangible through the regional calls and grant awards. However, translating start-up grants into durable rural livelihoods requires integrated instruments, such as land access mechanisms, tiered financing that links grants to credit and guarantees, robust business advisory services and incubation, and local market development, including aggregation, processing, and distribution. Regional heterogeneity must be explicitly addressed in comparative frameworks; for example, what works in the Lombardy region may not transfer to Calabria without adjustments for market, infrastructure and local governance capacity.

Uganda’s experience demonstrates that youth-specific strategies must be integrated into broader rural development and agriculture agendas. The existence of multiple national frameworks shows strong policy intent, but fragmented implementation reduces effectiveness. The case study demonstrated that aligning youth programmes with value-chain development rather than isolated funding schemes, enhancing local institutional capacity and monitoring, and tackling structural barriers—particularly land tenure and market access—can make participation in agriculture not only more attractive but also sustainable for young people.

Cameroon’s case study highlights the classic tension between policy intent and institutional capacity in improving youth participation in agriculture. The country has made notable progress in recognising young people as strategic actors in rural transformation, with a growing ecosystem of training, agribusiness support projects, and incubation, but translating these initiatives into sustained employment and viable agricultural enterprises is an ongoing challenge. To bridge this gap, policies must move beyond training and start-up support toward integrated strategies that combine land tenure reform, affordable credit, market development and climate-resilient infrastructure. Strengthening institutional capacity and fostering inclusive value chains will be critical for translating policy intent into sustainable rural livelihoods.

Nigeria, on the other hand, demonstrates both the potential and the constraints of youth-in-agriculture policies in a large, diverse and institutionally complex agrarian system. It has an extensive set of national policies, bank-led finance facilities and donor programs that could support youth engagement in agriculture, but remains limited by structural barriers, uneven implementation, and gaps between training and viable market opportunities. Access to finance remains the most persistent challenge, even in countries with national credit systems. Young people often lack collateral and credit history and are therefore unable to sustain their agricultural participation long-term.

4.1. Cross-Case Analysis

The case studies of Uganda, Cameroon, Italy, and Nigeria reveal both shared and context-specific dynamics shaping youth participation in agriculture. Despite diverse economic structures, policy environments, and governance capacities, several common lessons emerge about how youth-oriented policies are designed, implemented, and experienced, especially at local levels.

4.1.1. Persistent Gaps between Policy Intent and Practical Implementation

All four countries demonstrate a disconnect between national ambitions for youth inclusion in agriculture and the realities of their delivery. Specifically, Uganda and Cameroon face coordination deficits and weak local-level implementation of otherwise supportive policy frameworks, while Nigeria’s large-scale programmes lack youth-specific targeting, such as the Anchor Borrowers’ Program. Despite having comparatively stronger institutions, Italy struggles with uneven implementation due to regional disparities and bureaucratic complexities. This indicates that policy efficacy depends less on formal commitments and more on the coherence and capabilities of the implementing bodies. To bridge this gap, researchers have recommended linking policymakers and implementers and engaging people and communities in policy formulation and implementation, thereby prioritising a bottom-up approach [80,81].

4.1.2. Access to Land and Finances

In all four countries, land and finance constitute the most significant structural obstacles, aligning with the conceptual framework constructed for this study (Figure 1). In Uganda, Nigeria, and Cameroon, land tenure systems and collateral requirements exclude many young entrants, and some formal credit schemes reject young first-time applicants without access to land. Italy presents a different configuration—high land prices and slow generational transfer—but the effect on youth inclusion in agriculture is similar. The evidence from all four cases suggests that single-intervention approaches, such as micro-grants and training, do not resolve structural constraints. Securing land tenure and easing access to land support long-term investments and increase productivity, which are essential for agricultural and rural transformation, especially in Africa [82,83]. As a result, effective youth participation in agriculture requires bundled mechanisms that jointly address land access, start-up capital and medium-term credit.

4.1.3. Importance of Market Integration

The evidence from all four countries demonstrates an appropriate investment in youth training, with notable initiatives in Uganda’s skilling programs, Nigeria’s agripreneur initiatives, Cameroon’s incubation hubs, and Italy’s professional agricultural training and rural development measures. Despite this strong commitment, outcomes vary depending on the degree of integration with value chains. The agribusiness hubs with market linkages in Nigeria and Cameroon perform better than the stand-alone training programs in Uganda, where young people remain unlinked to buyers and input systems. Italy shows stronger value-chain integration, allowing trained youths to enter the market more competitively. Linking sector participants to markets should be a critical point of any rural development strategy, as it contributes to poverty reduction and resilience in rural communities [84]. This result emphasises the importance of combining capacity building with processing infrastructure, digital platforms, contract farming and buyer networks, as training without market integration produces weak outcomes.

4.1.4. Rural Infrastructure

In all four countries, rural infrastructure, such as roads, electricity, telecommunication, storage, and irrigation, has a significant influence on whether agriculture is seen as a viable livelihood by young people. Poor infrastructure increases transaction costs and undermines enterprise survival, thereby reducing the competitiveness of agriculture relative to urban sectors. Improving rural infrastructure directly improves farm incomes and investment opportunities [85], hence providing a solution to the high rates of youth unemployment evident across all four cases. Even in Italy, as a developed country compared to the other three cases, infrastructure is comparatively strong but uneven between North and South, contributing to regional youth migration. Youth migration, especially from rural areas, undermines the economic and social sustainability of development processes [86,87,88]. Moreover, young people can act as information and technology (IT) bridges to older farmers’ groups, thus impacting community-wide productivity, which positively impacts the social dynamics within the local population and addresses the agriculture and generation problem [38,89]. Rural infrastructure is, therefore, not merely complementary but fundamental to making agriculture a viable economic pathway for young people. Investing in logistics, transport, and technology is crucial for youth entry and retention in the agricultural sector.

4.1.5. Governance Capacity

In the four cases, Uganda and Cameroon rely heavily on donor-funded interventions (IFAD, FAO, EU), which innovate but rarely scale sustainably. Nigeria relies more on state-led financing but faces governance inconsistencies, while Italy benefits from stable EU support and robust governance systems. This evidence highlights the importance of integrating youth initiatives into national budgets and institutional frameworks, with competent governance structures. Research shows that better governance positively impacts agricultural productivity [90,91,92], which would be essential for all the countries in this study, as agriculture is still a significant contributor to their Gross Domestic Products (GDPs).

4.1.6. Diverging Agricultural Transformation Strategies

In all four national contexts, family farming is central to the agricultural sector, but with diverging transition pathways. In Uganda and Cameroon, family farms dominate, but generational transfer is weak due to low profitability and land scarcity. In Nigeria, youth frequently depend on family plots, but aspire to transition into more commercial agribusiness. Agribusiness expansion directly impacts rural community livelihoods and is therefore crucial to rural development [93,94]. In Italy, family farming remains strong, supported by succession incentives and EU-backed rural development funds. Strengthening family farm succession, modernising smallholders and supporting gradual upgrading in terms of mechanisation, digital extension, and agro-processing are vital for sustained youth inclusion in agriculture.

4.1.7. Monitoring and Evaluation Gaps

Across all four cases, monitoring systems seem to be oriented towards outputs—such as youths trained or grants awarded—rather than system-wide, youth-focused impact analysis, which undermines evidence-based policy refinement. For sustainable youth-in-agriculture systems, longitudinal tracking, integrated data systems, and monitoring and evaluation frameworks should be aligned across ministries and local governments [95]. This would strengthen impact, accountability and inform efficient resource allocation.

4.1.8. Youth Mindset and Agency

Youth perceptions of agriculture—its economic potential, social value and alignment with personal aspirations—emerge as significant determinants of their participation in agriculture, across all four countries. The evidence from the African countries in this paper indicates that young people often perceive agriculture as low-status, low-income and incompatible with their modern aspirations, particularly among the educated. They seem to favour urban employment and non-farm entrepreneurship [96,97,98]. In contrast, Italy demonstrates how positive agricultural identities can be fostered through structured support systems, cooperatives and rural development programs that enhance the attractiveness of farming. EU-backed initiatives promoting sustainability and innovation help reframe agriculture as a viable entrepreneurial pathway for young people [99]. Across all contexts, however, the evidence suggests that structural and institutional realities shape the youth mindset and agency. Where agriculture is associated with subsistence and poor infrastructure, young people exercise agency through diversification, seasonal migration or exit from agriculture. Where the sector offers credible opportunities—through value-added production and agribusiness—youth agency manifests as entry, business creation and innovation. This pattern aligns with broader research showing that youth aspirations are dynamic and relational, influenced not only by economic conditions but also by identity, social norms and the perceived modernity of agricultural occupations [95,100]. Agency is therefore both constrained by structural factors and capable of transforming them when supportive institutions exist, making it a key aspect of youth inclusion in agriculture. This reinforces the accuracy of the conceptual framework developed by the authors in this study, as shown in Figure 1, which highlights agency as one of the three main pillars of youth participation in agriculture.

Collectively, the four cases indicate that youth engagement in agriculture is not only shaped by the interaction between structural access (land and finance), system-level integration (markets, skills, infrastructure and value chains), and institutional capacity (policy, coordination and monitoring), but also by the symbolic and aspirational dimensions of farming. Therefore, policies that overlook youth agency risk misalignment between program design and young people’s lived realities. Young people have the greatest potential to become agents of inclusive and sustainable rural development through their participation in agriculture. They can ensure the interconnection of traditional local knowledge with innovative ideas [3], thus boosting agricultural transformation, which is strongly aligned with rural transformation.

5. Conclusions

Youth engagement in agriculture is essential for sustainable rural development, yet structural barriers and fragmented policy environments hinder progress. The comparative analysis of Uganda, Cameroon, Italy, and Nigeria shows that while policy intentions are clear across all nations, implementation gaps—particularly in land access, finance, infrastructure, and institutional coordination—restrict impact. To bridge these gaps, governments should adopt integrated strategies that focus on land tenure reforms, youth-friendly financing and credit guarantees, digital innovation, gender-sensitive approaches, climate-smart practices, and inclusive value chains. At the same time, youth mindset and agency are not just peripheral factors but central determinants of whether young people view agriculture as a viable livelihood or choose to exit the sector. These aspirations are shaped by perceived modernity, profitability, and dignity associated with farming, and are reinforced—or undermined—by the quality of local institutions, policies and available opportunities. Consequently, the comparative evidence suggests that youth-in-agriculture policies must move beyond fragmented, project-based approaches towards system-level interventions that address structural inequalities while also enhancing youth agency and innovation within the sector. Incorporating these measures within broader rural development plans will make agriculture a viable and appealing option for young people, supporting resilient agri-food systems and generational renewal.

Limitations and Future Research Avenues

This study relied primarily on secondary data and policy documents, which limits the ability to assess how policies are experienced by young people and implemented at the local level. Future research could complement this approach by incorporating primary data collection, including interviews with youth, policymakers, and local institutions to capture lived experiences and implementation dynamics. Moreover, farm-level socio-economic analysis, assessing characteristics such as farm size, farmer age distribution, gender dynamics and youth aspirations, can be carried out to validate policy recommendations. Additionally, the study accentuated formal policy environments; future work could more explicitly examine informal institutions, social norms and power relations—especially around land inheritance, gender, and intergenerational dynamics—that shape youth agency in agriculture. Finally, longitudinal research examining the impact of youth-focused policies on young people’s agricultural productivity and rural livelihoods over time in response to changing policies, markets and climatic conditions would provide stronger evidence for designing integrated, context-specific interventions.

Statement of the Use of Generative AI and AI-Assisted Technologies in the Writing Process

During the preparation of this manuscript, the author(s) used Perplexity AI in order to improve the academic tone and English grammar. After using this tool, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the published article.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.A.; Methodology, J.A., S.W.K. and K.E.W.; Formal Analysis, J.A.; Investigation, J.A., S.W.K. and K.E.W.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, J.A., S.W.K. and K.E.W.; Writing—Review & Editing, J.A. and S.W.K.

Ethics Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data is publicly available and cited with references.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

-

Galstyan M. Re-Conceptualising Youth: Theoretical Overview. J. Sociol. Bull. Yerevan Univ. 2022, 13, 22–27. DOI:10.46991/BYSU:F/2022.13.2.022 [Google Scholar]

-

UNDESA. Youth—Social Policy and Development Division. 2015. Available online: https://undesadspd.org/Youth.aspx (accessed on 19 September 2025).

-

FAO, IFAD. UNITED NATIONS DECADE OF FAMILY FARMING 2019–2028—Global Action Plan; FAO, IFAD: Rome, Italy, 2019.

-

European Commission. Agriculture’s Contribution to Rural Development. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Non-Trade Concerns in Agriculture, Ullensvang, Norway, 2–4 July 2000. [Google Scholar]

-

Shen D, Liang H, Shi W. Rural Population Aging, Capital Deepening, and Agricultural Labor Productivity. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8331. DOI:10.3390/SU15108331 [Google Scholar]

-

Mitchell J, Bradley D, Wilson J, Goins RT. The Aging Farm Population and Rural Aging Research. J. Agromed. 2008, 13, 95–109. DOI:10.1080/10599240802125383 [Google Scholar]

-

Bernhardt JH, Langley RL. Analysis of tractor-related deaths in North Carolina from 1979 to 1988. J. Rural. Health 1999, 15, 285–295. DOI:10.1111/J.1748-0361.1999.TB00750.X [Google Scholar]

-

Kakwagh VV. The Link between Rural-Urban Migration of Youth and Crime in Anyigba Town, Kogi State-Nigeria. Int. J. Rural. Dev. Environ. Health Res. (IJREH) 2019, 3, 86–91. DOI:10.22161/ijreh.3.3.2 [Google Scholar]

-

Chen X, Zhong H. Delinquency and Crime among Immigrant Youth—An Integrative Review of Theoretical Explanations. Laws 2013, 2, 210–232. DOI:10.3390/LAWS2030210 [Google Scholar]

-

Rakauskienė OG, Ranceva O. Youth Unemployment and Emigration Trends. Intellect. Econ. 2014, 8, 165–177. DOI:10.13165/IE-14-8-1-12 [Google Scholar]

-

Interreg Europe. Policy instruments|Interreg Europe. European Union. 2025. Available online: https://www.interregeurope.eu/help-centre/apply-for-funding/policy-instruments (accessed on 31 October 2025).

-

Hitlin S, Long C. Agency as a Sociological Variable: A Preliminary Model of Individuals, Situations, and the Life Course. Sociol. Compass 2009, 3, 137–160. DOI:10.1111/J.1751-9020.2008.00189.X

-

UNICEF. U-Report|UNICEF Uganda. 2024. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/uganda/what-we-do/u-report (accessed on 21 October 2025).

-

World Bank. Uganda Economic Update 21st Edition: Leveraging Sustainable Tourism to Support Growth & Diversification; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. DOI:10.1596/40750

-

Uganda Bureau of Statistics. NATIONAL POPULATION AND HOUSING CENSUS 2024 FINAL REPORT VOLUME 1 (MAIN) REPUBLIC OF UGANDA; UBOS: Kampala, Uganda, 2024. [Google Scholar]

-

MAAIF. NATIONAL AGRICULTURE POLICY; Ministry of Agriculture, Animal Industry and Fisheries: Kampala, Uganda, 2013. [Google Scholar]

-

Ose Y. Effectiveness and Duplicability of the Youth Inspiring Youth in Agriculture Initiative—Lessons Learned from Uganda; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar]

-

Tony T. How Uganda’s Tech-Savvy ‘Generation Z’ Is Transforming Its Agriculture. World Bank Blogs. 2020. Available online: https://blogs.worldbank.org/en/nasikiliza/how-ugandas-tech-savvy-generation-z-transforming-its-agriculture (accessed on 16 December 2025).

-

Stevenson S, Raymond M. Majority of Youth See Uganda Moving in Right Direction But Economic Outlook Is Mixed. Afrobarometer. 2025. Available online: https://www.afrobarometer.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/AD975-Youth-see-Uganda-moving-in-right-direction-but-economic-outlook-is-mixed-Afrobarometer-28april25.pdf (accessed on 21 October 2025).

-

Monitor. ICT, Business Graduates among the Most Unemployed, Survey Finds. 2024. Available online: https://www.monitor.co.ug/uganda/news/national/ict-business-graduates-among-the-most-unemployed-survey-finds-4856032 (accessed on 21 October 2025).

-

MGLSD. NATIONAL YOUTH ACTION PLAN Theme: “Unlocking Youth Potential for Sustainable Wealth Creation and Development”; Ministry of Gender, Labour and Social Development: Kampala, Uganda, 2016.

-

Uganda Bureau of Statistics [UBOS]. UGANDA BUREAU OF STATISTICS 2022 STATISTICAL ABSTRACT; UBOS: Kampala, Uganda, 2022. [Google Scholar]

-

MAAIF. NATIONAL STRATEGY FOR YOUTH EMPLOYMENT IN AGRICULTURE; MINISTRY OF AGRICULTURE, ANIMAL INDUSTRY & FISHERIES: Entebbe, Uganda, 2017. [Google Scholar]

-

MGLSD. Youth Livelihood Programme (YLP). 2020. Available online: https://mglsd.go.ug/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Brochure%20-%20End%20of%20YLP%20Phase%20One.pdf (accessed on 21 October 2025).

-

Ministry of ICT and National Guidance. Parish Development Model 2021. Available online: https://ict.go.ug/programs/parish-development-model (accessed on 23 October 2025).

-

Segawa A. The Challenges and Outcomes of Establishing a Successful Agribusiness Incubator: The CURAD Story. Agriculture for Development 2019. Available online: https://taa-international.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/Ag4Dev38_web_version.pdf.pagespeed.ce.Kx0Qr6k_GZ.pdf#page=19 (accessed on 23 October 2025).

-

FAO. Agribusiness Incubation and Acceleration Landscape in Africa; FAO: Rome, Italy; African Union: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2023. DOI:10.4060/CC5763EN

-

Kansiime MK, Aliamo C, Alokit C, Rware H, Murungi D, Kamulegeya P, et al. Pathways and business models for sustainable youth employment in agriculture: A review of research and practice in Africa. CABI Agric. Biosci. 2025, 6, 0045. DOI:10.1079/AB.2025.0045 [Google Scholar]

-

Namatovu R, Langevang T, Dawa S, Kyejjusa S. Youth Entrepreneurship Trends and Policies in Uganda: In Young Entrepreneurs in Sub-Saharan Africa; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2016. Available online: https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/oa-edit/10.4324/9781315730257-3/youth-entrepreneurship-trends-policies-uganda-rebecca-namatovu-thilde-langevang-samuel-dawa-sarah-kyejjusa (accessed on 23 October 2025).

-

Mouafo PT, Emmanuel ON, Yacoubou B, Danmou BN. Public policies and the future of agriculture in Cameroon: A case study of the “Tree Year Special Youth Plan”. Heliyon 2024, 10, e34803. DOI:10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e34803

-

Tchokonthe FA, Mimche H. Determinants and Impact of Youth Involvement in Agricultural Sector: Evidence from Young Farmers Beneficiaries of PEA-Youth and PCP AFOP Public Programs Living in Central and Littoral Regions of Cameroon. Int. J. Agric. Stud. 2023, 2, 21–44. DOI:10.58425/ijas.v2i1.130 [Google Scholar]

-

World Bank. Agriculture, Forestry, and Fishing, Value Added (% of GDP)—Cameroon. 2024. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NV.AGR.TOTL.ZS?locations=CM (accessed on 13 October 2025).

-

Chitchui Toumeni Armand Anaciet. Modern Trends in Agricultural Development in Cameroon and Ways to Ensure Its Sustainability. Ekonomìka ta upravlìnnâ APK, 21–28. 2019. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/336307525_MODERN_TRENDS_IN_AGRICULTURAL_DEVELOPMENT_IN_CAMEROON_AND_WAYS_TO_ENSURE_ITS_SUSTAINABILITY (accessed on 13 October 2025).

-

Nana AS, Falkenberg T, Rechenburg A, Adong A, Ayo A, Nbendah P, et al. Farming Practices and Disease Prevalence among Urban Lowland Farmers in Cameroon, Central Africa. Agriculture 2022, 12, 230. DOI:10.3390/AGRICULTURE12020230

-

Irwin S, Mader P, Flynn J. Emerging Issues Report Emerging Issues Report How Youth-Specific Is Africa’s Youth Employment Challenge? 2018. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5b4323f4ed915d39f09ff21d/How_youth- specific_is_Africas_youth_employment_challenge_FinalV2.pdf (accessed on 13 October 2025).

-

Mkong CJ, Abdoulaye T, Dontsop-Nguezet PM, Bamba Z, Manyong V, Shu G. Determinant of university students’ choices and preferences of agricultural sub-sector engagement in cameroon. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6564. DOI:10.3390/su13126564

-

Bezu S, Holden S. Are rural youth in ethiopia abandoning agriculture? World Dev. 2014, 64, 259–272. DOI:10.1016/j.worlddev.2014.06.013 [Google Scholar]

-

White B. Agriculture and the Generation Problem: Rural Youth, Employment and the Future of Farming. IDS Bull. 2012, 43, 9–19. DOI:10.1111/j.1759-5436.2012.00375.x [Google Scholar]

-

Gemma Ahaibwe SMMML. Youth Engagement in Agriculture in Uganda: Challenges and Prospects. 2013. Available online: https://ageconsearch.umn.edu/record/159673/?v=pdf (accessed on 19 September 2025).

-

Leavy J, Smith S. Future Farmers: Youth Aspirations, Expectations and Life Choices. 2010. Available online: https://d1wqt xts1xzle7.cloudfront.net/33069740/Leavy_and_Smith_2010_future_farmers-libre.pdf?1393954303=&response-content-disposition=inline%3B+filename%3DFuture_Farmers_Youth_Aspirations_Expecta.pdf&Expires=1768374616&Signature=as4NNMQst998O~2CJDAkHgc~Qnsa3IMGa8uX9LrJBqw9vqfIDITAQuxKJSmr4iF6~4lpHnU8Sf5999UCYxak~KneI~~SaRRKXJscMCR8s1Od9Lro9dEOb2OhVqaeZfPBIgiv6y3rTuDXY31jfu5lRqn7jFUiOMSoEmno0nGfMZVlMJLfw12k69TFOcoUB4m9o0ri9BryXQzhLt92GGO5uJJUC2fOkDNHSN5TS8Dj6gto3r3bjn-sR05nN9L~IuXHRF4Y5t6T3npX21AANhYvA5DZLkdaN5RdF7oKEocSu5aFc1kousKiba96jtU-RIUsb0G2-WGwwZqWpdiDkXum4A__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAJLOHF5GGSLRBV4ZA (accessed on 11 October 2025).

-

Amare M, Abay KA, Arndt C, Shiferaw B. Youth Migration Decisions in Sub-Saharan Africa: Satellite-Based Empirical Evidence from Nigeria. Popul. Dev. Rev. 2021, 47, 151–179. DOI:10.1111/padr.12383 [Google Scholar]

-

Ball A. The Future of Agriculture in Cameroon in the Age of Agricultural Biotechnology. 2016. Available online: https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection/2287/ (accessed on 13 October 2025).

-

Abia WA, Shum CE, Fomboh RN, Ntungwe EN, Ageh MT. Agriculture in Cameroon: Proposed Strategies to Sustain Productivity. Int. J. Res. Agric. Food Sci. 2016, 2, 1–3. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Richard-Fomboh/publication/319312288_Agriculture_in_Cameroon_Proposed_Strategies_to_Sustain_Productivity/links/59a39ace0f7e9b0fb8b041cd/Agriculture-in-Cameroon-Proposed-Strategies-to-Sustain-Productivity.pdf (accessed on 14 October 2025).

-

Nchanji E, Acheampong P, Ngoh SB, Nyamolo V, Cosmas L. Comparative analysis of youth transition in bean production systems in Ghana and Cameroon. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 154. DOI:10.1057/s41599-024-02620-6

-

World Bank Group. A focus on Youth, Women, and Employment Support Programs. 2025. Available online: https://thedocs.worldbank.org/en/doc/235ca6d24cc8d08112064fc153f9bf13-0310012025/original/Afghanistan-Policy-Note-Employment-April-2025.pdf (accessed on 21 November 2025).

-

Gibbon P, Riisgaard L. A new system of labour management in african large-scale agriculture? J. Agrar. Change 2014, 14, 94–128. DOI:10.1111/joac.12043

-

Fouepe GH, Folefack DP, Nguedia S, Wouapi HA. CONTRIBUTION A L’ANALYSE DES DISPOSITIFS D’APPUI A L’INSERTION PROFESSIONNELLE DES JEUNES DANS LE SECTEUR AGROPASTORAL AU CAMEROUN: LE CAS DU DEPARTEMENT DE LA MENOUA [Contribution to assessment of strategies for professional integration of youth in agro-pastoral sector in Cameroon: A case study of Menoua Division]. Int. J. Innov. Sci. Res. 2015, 16, 55–69. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Denis-Folefack/publication/277404117_CONTRIBUTION_ A_L'ANALYSE_DES_DISPOSITIFS_D'APPUI_A_L'INSERTION_PROFESSIONNELLE_DES_JEUNES_DANS_LE_SECTEUR_AGROPASTORAL_AU_CAMEROUN_LE_CAS_DU_DEPARTEMENT_DE_LA_MENOUA_Contribution_to_assessment_of_stra/links/5569ff3f08aefcb861d5f2f8/CONTRIBUTION-A-LANALYSE-DES-DISPOSITIFS-DAPPUI-A-LINSERTION-PROFESSIONNELLE-DES-JEUNES-DANS-LE-SECTEUR-AGROPASTORAL-AU-CAMEROUN-LE-CAS-DU-DEPARTEMENT-DE-LA-MENOUA-Contribution-to-assessment-of-strate.pdf (accessed on 13 October 2025).

-

Politiques publiques et emploi des jeunes: une étude empirique du cas Camerounais Par AVOM Désiré. 2019. Available online: https://aec.afdb.org/sites/default/files/papers/354-desire_avom-politiques_publiques_et_emploi_des_jeunes-_une_etude_empirique_du_cas_camerounais.pdf (accessed on 4 October 2025).

-

MINADER. The Minister of Agriculture and Rural Development Gabriel Mbairobe in August 2024 Launched the Emergency Development Food Crisis Response Project (PULCCA). 2024. Available online: https://www.minader.cm/index.php/2024/08/26/60-71-billion-project-launched-in-bamenda-north-west-region-of-cameroon/ (accessed on 14 October 2025).

-

Enjei LM, Che CV. The Impact of Public Policy to the Development Plan of Cameroon. Open J. Soc. Sci. 2025, 13, 334–355. Doi:10.4236/jss.2025.134020

-

International Finance Corporation (IFC). Country Private Sector Diagnostic: Creating Markets in Cameroon. 2022. Available online: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/099003102202314038/pdf/IDU-1304ea1f-5592-4e7d-92ca-0baab7f2be5c.pdf (accessed on 5 October 2025).

-

Ebong MN. COMMENTARY: CAMEROON’S RURAL SECTOR DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY AND NATIONAL AGRICULTURE INVESTMENT PLAN 2020–2030. 2025. Available online: https://ecooutlooknews.com/2025/08/12/commentary-cameroons-rural-sector-development-strategy-and-national-agriculture-investement-plan-2020-2030/ (accessed on 4 October 2025).

-

Ntu SL, Egwu BMJ, Tambi MD. Informal Institutional Characteristics and Youth Involvement in Agribusiness Entrepreneurship in Fako Division, Cameroon: A Structural Equation Modeling Approach. Int. J. Res. Innov. Soc. Sci. 2023, 7, 222–237. DOI:10.47772/ijriss.2023.7418

-

European Commission. At a Glance: Italy’s CAP Strategic Plan; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2025. [Google Scholar]

-