The Anti-Fibrotic Potential of GLP-1 and GIP Receptor Agonists in Chronic Inflammatory Disorders: Mechanisms and Therapeutic Horizons

Received: 04 December 2025 Revised: 29 December 2025 Accepted: 08 January 2026 Published: 12 January 2026

© 2026 The authors. This is an open access article under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

1. Introduction

Fibrotic diseases, such as metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), chronic kidney disease (CKD), heart failure, neoplasms, and pulmonary disease such as idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), are estimated to account for around 35% of global deaths [1]. Furthermore, fibrotic remodelling within the synovial joint in rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis [2,3] is considered a major driver of chronic pain and loss of mobility.

The fibrotic process is a dysregulated wound-healing response, driven by the persistent activation of fibroblasts (or myofibroblasts), which results in the deposition of excessive extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins such as collagen [4], a key feature of pathological tissue remodelling in fibrotic disorders [5,6,7,8]. These activated fibroblasts also drive chronic persistent inflammation via the secretion and expression of pro-angiogenic and pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines [9], which promote the recruitment of inflammatory immune cells [10].

Despite the profound impact of fibrosis, approved therapeutics that specifically target this pathology are limited. The anti-fibrotic drug pirfenidone [11] (which targets the key fibrotic cytokines TGF-β, TNF-α, and IL-6) and the tyrosine kinase inhibitor nintedanib [12] are both effective in targeting lung fibrosis, such as in IPF. However, these drugs are limited: They slow but do not reverse fibrosis, they are poorly tolerated, and it remains to be established whether they are translatable to other fibrotic inflammatory disorders, highlighting the clinical unmet need for alternative targeted anti-fibrotic strategies.

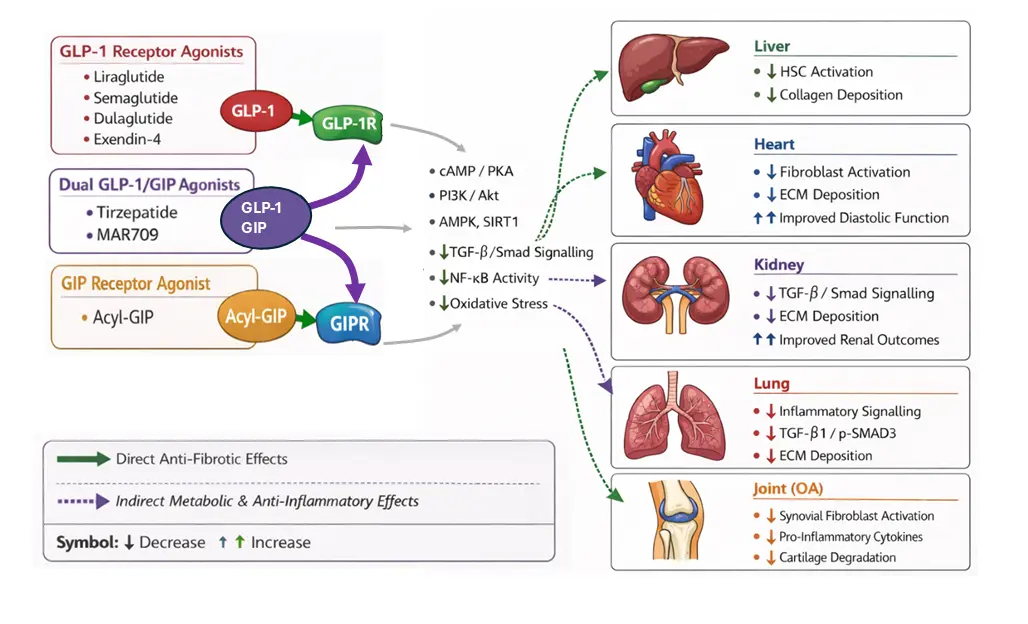

In seeking to identify existing drugs with anti-fibrotic potential that could be repurposed, incretin receptor agonists, namely the glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) receptor agonists, are emerging as candidates. The GLP-1 receptor agonists liraglutide and semaglutide are already well-established for their glucoregulatory and weight-loss effects in patients with type 2 diabetes (T2DM) and overweight/obesity [13,14,15]. However, emerging evidence suggests that their benefits extended beyond glycaemic control, with pleiotropic effects on multiple organ systems, including significant anti-fibrotic effects. Therefore, in this review we detail the direct and indirect molecular mechanisms by which incretin receptor agonists inhibit fibrotic signalling pathways, and critically appraise the evidence for their preclinical and clinical efficacy in fibrotic disorders across diverse tissues, including the liver, heart, kidney, lung, and joints (Table 1; Figure 1), ultimately culminating in an evaluation of their clinical potential for the treatment of fibrotic inflammatory disorders.

Table 1. Summary of preclinical and clinical evidence for the anti-fibrotic potential of incretin agonists across organ systems.

|

Disorder |

Preclinical Evidence |

Clinical Evidence |

|---|---|---|

|

Liver fibrosis |

In vivo: Thioacetamide-induced mouse model; semaglutide reduced α-SMA, oxidative stress, and collagen deposition; downregulated TGF-β/Smad, upregulated SIRT1 and p-AMPK. |

MASLD/MASH patients: LEAN study—liraglutide reduced fibrosis progression; Phase 3 semaglutide trial—increased resolution of steatohepatitis and reduced fibrosis. Tirzepatide and semaglutide improved liver steatosis/inflammation. |

|

Cardiovascular fibrosis |

In vitro: Isolated cardiomyocytes—GLP-1R agonists activated PI3K/Akt, AMPK, cAMP/PKA; reduced NOX4 oxidative stress. Primary cardiac fibroblasts—inhibited TGF-β signalling, COL1A1/COL3A1 expression. In vivo: Rodent diabetic or pressure-overload cardiomyopathy—dulaglutide reduced myocardial collagen (~35%) and improved diastolic function; obese HFpEF mouse—semaglutide decreased collagen; MI models—liraglutide reduced adverse remodelling. |

Large CVOTs (liraglutide, semaglutide, dulaglutide)—reduced CV events/mortality; SELECT trial—semaglutide reduced HF risk. Smaller T2DM/obesity cohorts—improved diastolic function, LV mass index, exercise capacity (liraglutide, semaglutide). Fibrosis is not directly measured. |

|

Renal fibrosis/CKD |

In vitro: Tubular epithelial cells—Exendin-4 reduced TGF-β-induced fibronectin/COL1A1 and miR-192; Mesangial cells—GLP-1R agonists suppressed NF-κB/TGF-β, reduced ECM, proliferation via AMPK. In vivo: UUO model—liraglutide suppressed TGF-β/Smad3/ERK1/2, reduced collagen; STZ diabetic rats—liraglutide or Exendin-4 reduced α-SMA, collagen I, fibronectin, glomerulosclerosis, oxidative stress. |

CKD/T2DM patients (LEADER, SUSTAIN-6, REWIND, FLOW)—liraglutide, semaglutide, and dulaglutide improved renal outcomes (macroalbuminuria, eGFR, composite endpoints), but fibrosis was not directly measured. |

|

Pulmonary fibrosis |

In vitro: Alveolar macrophages—GLP-1R agonists suppressed NLRP3/IL-1β via histone lactylation; airway/alveolar epithelial cells—reduced IL-33, TSLP; pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells—liraglutide/exendin-4 reduced PDGF-BB-induced proliferation/migration. In vivo: Bleomycin lung injury -semaglutide microparticles reduced α-SMA, Col1a1, TGF-β1, p-SMAD3; pulmonary hypertension rodent models—liraglutide/exendin-4 reduced vascular remodelling, inflammation, hypertrophy. GLP-1R knockout reduced injury, highlighting context-dependence. |

Meta-analyses in T2DM (77,000+ pts)—lower incidence of pulmonary fibrosis/ILD with GLP-1R agonists; no trials with fibrosis-specific endpoints. |

|

Joint fibrosis/Osteoarthritis |

In vitro: Rodent primary chondrocytes—liraglutide inhibited IL-1β/AGEs-induced TNF-α, IL-6, iNOS; Human SW1353—dulaglutide inhibited AGEs/NFkB cytokine expression; human primary articular chondrocytes—lixisenatide reduced TNF-α, IL-6, IL-7. In vivo: Murine MIA-induced OA—intra-articular liraglutide reduced synovitis and pain; Rat MIA & ACL-transection OA models—subcutaneous liraglutide reduced pro-inflammatory cytokines, cartilage degradation. Effects are partly independent of weight loss. |

Knee OA patients with obesity—semaglutide reduced pain (WOMAC); Chinese cohort with T2DM—GLP-1 agonists (liraglutide, semaglutide) reduced cartilage volume loss over 2 years. |

2. Molecular Mechanisms of Incretin Receptor Agonism in Fibrosis

The anti-fibrotic actions of incretin receptor agonists are likely mediated through a combination of direct receptor-mediated signalling and indirect systemic effects.

2.1. Direct Anti-Fibrotic Mechanisms

In considering the direct anti-fibrotic mechanisms, it is important to note that the expression of incretin receptors is not confined to the pancreatic islets. In humans, immunohistochemistry using a monoclonal antibody showed that the GLP-1 receptor protein is expressed in the pancreas, in smooth muscle cells of the kidney, lung, and gastrointestinal (GI) tract, and in myocytes of the heart [16]. Furthermore, GLP-1 receptor mRNA and protein have been reported in the brains of adult rodents and macaques [17]. Expression of the GIP receptor appears to be more ubiquitous, with Protein Atlas (proteinatlas.org; accessed on 5 December 2025 [18]) indicating expression of both mRNA and protein across multiple tissue types including brain, liver, kidney, heart, pancreas and gastrointestinal tissues. Furthermore, Protein Atlas indicates that GLP-1 receptor protein (but not mRNA) is present in skeletal muscle, whilst conversely GLP-1 receptor mRNA (but not protein) is detected in adipose tissue. However, data on the expression of either receptor in fibroblasts across different organ systems has not been reported.

Signalling through GLP-1 and GIP receptors involves Gαs-coupled pathways, increasing intracellular cAMP, which, downstream, can modulate the expression and/or activity of several fibrosis effectors. For example, a key fibrotic effector pathway mediated by GLP-1 receptor agonists is AMPK signalling. AMPK activation suppresses key fibrotic signalling pathways, including TGF-β/Smad and NFκB, resulting in inhibition of fibroblast proliferation and reduced ECM protein production [19]. Several studies have demonstrated that the GLP-1 receptor agonists such as extendin-4 and liraglutide can activate AMPK signalling in multiple tissues and cell types, including cardiomyocyte hyperglycaemic [20] or cardiac hypertrophy models [21], in rat INS-1 pancreatic beta cells [22], and in L6 myotubes, resulting in the sensitisation of insulin-stimulated glucose uptake [23].

Notably, TGF-β is considered the master regulator of fibrosis, and its downstream signalling is transduced primarily through the phosphorylation and activation of receptor-associated Smads (R-Smads), Smad2 and Smad3. These activated Smads form a complex with Smad4, which translocates to the nucleus and promotes the expression of pro-fibrotic genes [24], such as Type I Collagen alpha 1 (COL1A1) and Fibronectin and Connective Tissue Growth Factor (CTGF). Importantly, GLP-1 receptor agonism has been demonstrated in several fibrotic models to lead to inhibition of TGF-β signalling. In rodent H9C2 cardiomyocytes, liraglutide inhibited TGF-β signalling and reduced collagen production [25]. In a rat model of diabetes-induced testicular dysfunction, liraglutide reduced testicular TGF-β and Smad2 mRNA expression levels [26], whilst in HUVECs, liraglutide attenuated high glucose and IL-1β-induced TGF-β signalling (via inhibition of Smad2 phosphorylation), leading to reduced endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EndMT) marker expression [27].

2.2. Indirect Anti-Fibrotic Mechanisms

Incretin agonists likely also exert anti-fibrotic activity by indirect mechanisms. Firstly, metabolically, both hyperglycaemia and hyperinsulinemia are potent pro-fibrotic stimuli. High glucose levels lead to the creation of advanced glycation end products (AGEs), which contribute to fibrotic tissue formation [28], and both AGEs and excess insulin can promote fibroblast proliferation and ECM production [29,30]. Thus, by improving glycaemic control and improving insulin resistance, incretin receptor agonists may reduce fibrosis indirectly.

Secondly, significant weight loss and the resultant change in the inflammatory phenotype of obese adipose tissue would reduce the release into the circulation of key pro-fibrotic pro-inflammatory cytokines/adipokines such as TNF-α, IL-6, leptin [31], visfatin and resistin, and increase levels of anti-fibrotic adipokines such as adiponectin [32]. For example, resistin-stimulated cardiac fibroblasts show increased expression of ECM proteins, including α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA), COL1A1, CTGF, and fibronectin [33]. Thus, incretin receptor agonist-induced weight loss would be expected to create a tissue environment that is less conducive to fibrosis [34].

3. Efficacy of Incretin Receptor Agonists in Tissue-Specific Fibrotic Inflammatory Disorders

3.1. Liver Fibrosis

Liver fibrosis, with activation of hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) driving ECM deposition and progressive pathological changes to the liver architecture, is a central determinant of morbidity and mortality in MASLD. Thus, therapeutic strategies that can slow, halt, or reverse fibrotic change are a major clinical priority. As such, liver fibrosis has been a major focus of incretin receptor agonist research.

Several clinical studies have shown that GLP-1 receptor agonists, including semaglutide and liraglutide, and the dual GIP/GLP-1 receptor agonist tirzepatide, reduce liver steatosis and inflammation in MASLD patients [35]. In the LEAN clinical study in MASLD patients, liraglutide was found to reduce the incidence of fibrosis progression compared to placebo [36]. Similarly, in an ongoing phase 3 trial in patients with Metabolic Dysfunction–Associated Steatohepatitis (MASH; a subset of MASLD), resolution of steatohepatitis and reduction in liver fibrosis were reported in a greater proportion of patients in the semaglutide group compared to the placebo group [37].

A growing number of preclinical studies suggest that incretin receptor agonists may modulate core pathways involved in hepatic fibrogenesis, though whether these effects are direct or secondary to metabolic improvements remains an area of active investigation. In vivo data from rodent fibrosis models support a potential anti-fibrotic action. For example, in a thioacetamide-induced mouse model, semaglutide reduced biochemical and histological markers of liver injury, attenuated α-SMA expression, decreased oxidative stress, and downregulated the canonical TGF-β/Smad signalling pathway while upregulating SIRT1 and phosphorylated AMPK. These changes were accompanied by a significant reduction in collagen deposition and overall fibrosis severity, suggesting that GLP-1 receptor agonism can modify established fibrogenic signalling cascades within the liver [38].

In contrast, cell-based studies in human hepatic stellate cells and hepatocytes provide a more nuanced picture. Using both immortalised and primary human cells, liraglutide, acyl-GIP, and a dual GLP-1/GIP receptor agonist (MAR709) failed to produce measurable effects on lipid accumulation, fibrogenic gene expression, or CREB phosphorylation at physiologically relevant concentrations. Importantly, these compounds did not prevent TGF-β-induced HSC activation or reduce expression of ECM genes, including α-SMA and COL1A1 [39]. Thus, these in vitro findings indicate that the beneficial effect of incretin receptor agonists on fibrosis progression in MASLD patients is likely to be mediated indirectly through improvements in body weight, inflammation, and insulin resistance, rather than through the direct action on hepatic parenchymal or non-parenchymal cells.

In summary, incretin receptor agonists demonstrate consistent anti-fibrotic effects in vivo, reducing hepatic stellate cell activation, oxidative stress, and collagen deposition in animal models, and improving fibrosis outcomes in clinical MASLD and MASH studies. However, evidence from human cell-based experiments suggests that these benefits are unlikely to result from direct actions on hepatocytes or HSCs, instead reflecting indirect metabolic and anti-inflammatory mechanisms. Together, these data highlight the therapeutic potential of incretin receptor agonism in slowing or reversing liver fibrosis, while emphasising the need for further mechanistic studies in human-relevant systems to delineate direct versus indirect effects fully.

3.2. Cardiovascular Fibrosis

Cardiovascular fibrosis is a hallmark of pathological cardiac remodelling and a key mediator of the progression from metabolic or ischemic injury to overt heart failure. Chronic stress signals, including hyperglycaemia, inflammation, neurohormonal activation, and mechanical overload, promote the activation of cardiac fibroblasts and the accumulation of extracellular matrix within the myocardium. This stiffening and structural distortion impair diastolic and eventually systolic function, making fibrosis a central determinant of adverse cardiovascular outcomes. As a result, interventions capable of attenuating or reversing fibrotic remodelling hold significant therapeutic promise in cardiometabolic disease.

Clinical studies of incretin receptor agonists provide evidence of cardiovascular benefit, but they do not directly demonstrate anti-fibrotic effects, as fibrosis has not been measured as a primary outcome in major trials. Large cardiovascular outcome trials with liraglutide [40], semaglutide [41], and dulaglutide [42] have shown reductions in adverse cardiovascular events and cardiovascular mortality, while the SELECT trial demonstrated a reduction in heart failure with semaglutide [43]. Despite these benefits, these trials assessed cardiovascular clinical endpoints rather than myocardial structure or ECM collagen deposition, and thus do not establish a fibrosis-mediated mechanism.

Smaller cohort mechanistic studies provide indirect evidence that is suggestive of favourable fibrotic cardiac remodelling. In a prospective study of T2DM patients, six months of liraglutide therapy improved diastolic function and reduced left ventricular mass index [44], while additional echocardiographic studies have reported improvements in global longitudinal strain and left ventricular mass with GLP-1 receptor agonists [45]. Similarly, in patients with obesity-related HFpEF (Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction), semaglutide produced substantial improvements in symptoms and exercise capacity [46]. These findings are consistent with reduced myocardial stiffness and remodelling, but remain surrogates rather than direct measurements of fibrosis. Moreover, liraglutide trials in patients with HFrEF provided no clinical benefit, underscoring that the efficacy of incretin receptor agonism does not uniformly extend across heart-failure phenotypes and that remodelling mechanisms may differ by disease context [47].

Preclinical in vivo models have demonstrated anti-fibrotic effects of incretin receptor agonism in the heart. In rodent models of diabetic or pressure-overload cardiomyopathy, dulaglutide reduced myocardial collagen content by approximately 35% and improved diastolic function [48]. Semaglutide similarly decreased collagen deposition and improved diastolic indices in an obese mouse model of HFpEF [49]. In experimental myocardial infarction, liraglutide activated cardioprotective signalling pathways and reduced adverse ventricular remodelling [50].

In vitro studies provide mechanistic support for the anti-fibrotic actions of incretin receptor agonists in the cardiovascular system. In isolated cardiomyocytes, GLP-1 receptor agonists activated PI3K/Akt, AMPK, and cAMP/PKA pathways while reducing NOX4-mediated oxidative stress, signalling cardioprotective effects by alleviating ER stress-induced apoptosis [51]. Similarly, in primary cardiac fibroblasts, GLP-1R agonism inhibited TGF-β signalling activity and expression of ECM proteins, including COL1A1 and COL3A1 [25]. Together, these cellular studies highlight multiple convergent mechanisms, namely anti-inflammatory, anti-oxidative, pro-survival, and TGF-β/Smad inhibitory, through which incretin receptor agonists may modulate cardiac fibrogenesis.

3.3. Renal Fibrosis and Chronic Kidney Disease

Renal fibrosis is a major driver of progressive kidney function loss in CKD. Chronic metabolic, inflammatory, and hemodynamic stresses lead to myofibroblast activation, ECM deposition, and distortion of glomerular and tubulointerstitial architecture. As fibrotic scarring accumulates, nephron function declines irreversibly, underscoring the importance of targeting fibrosis as a central pathway in developing therapeutics for CKD.

Clinical evidence supporting the renoprotective effects of incretin receptor agonists primarily derives from large cardiovascular outcome trials, where kidney outcomes were secondary endpoints. These studies consistently report favourable renal outcomes (e.g., eGFR, macroalbuminuria, or serum creatinine levels) with GLP-1 receptor agonists. For example, in LEADER, liraglutide reduced the composite renal endpoint, driven mainly by a lower incidence of new-onset macroalbuminuria [52]. Similar findings were observed with semaglutide in SUSTAIN-6 [53] and dulaglutide in REWIND [54] clinical trials, where reductions in nephropathy events were reported. However, none included a direct assessment of renal fibrosis. Similarly, the recent FLOW trial demonstrated that semaglutide significantly reduced the risk of major kidney outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes and CKD. However, these benefits were based on clinical endpoints and did not include direct measures of renal fibrosis, such as histology or fibrosis-specific biomarkers [55].

In contrast, preclinical in vivo studies provide more direct evidence that incretin receptor agonism attenuates renal fibrogenesis. In the unilateral ureteral obstruction model, liraglutide suppressed TGF-β expression and downstream Smad3 and ERK1/2 signalling, resulting in reduced tubulointerstitial collagen accumulation and improved histological fibrosis scores [56]. Similar anti-fibrotic effects of liraglutide have been reported in a streptozotocin (STZ)-induced diabetic model, where liraglutide reduced α-SMA, collagen I and fibronectin expression and altered the renal proteome consistent with decreased oxidative stress and attenuated ECM deposition [57]. In addition, Exendin-4 in STZ diabetic rats attenuated albuminuria and glomerulosclerosis by inhibiting the activation of NFκB and subsequent oxidative stress pathways [58]. Importantly, these effects were independent of the glucose lowering effect of the incretin receptor agonist.

Furthermore, across several cellular models, incretin receptor agonists have been reported to suppress pro-fibrotic signalling pathways, including TGF-β/Smad signalling, and NFκB activation, leading to reduced expression of ECM proteins. For example, in tubular epithelial cells exposed to high glucose, Exendin-4 reduced TGF-β-induced fibronectin and COL1A1 expression and decreased secretion of the microRNA miR192, which is implicated in kidney fibrosis, pro-fibrotic microRNA-192, a mediator implicated in renal fibrosis [59]. Similarly, in mesangial cells, GLP-1 receptor agonists have been shown to suppress either high-glucose-induced or AGEs-induced pro-fibrotic signalling pathways, including NF-κB activation and TGF-β1 expression, leading to reduced ECM deposition [60,61], and to suppress their proliferation via AMPK activation [62].

Collectively, while clinical trials of GLP-1 receptor agonists consistently demonstrate renoprotective effects, these studies have not directly assessed renal fibrosis. By contrast, preclinical in vivo and in vitro studies both indicate that incretin receptor agonism can attenuate fibrogenic signalling in models of kidney disorders, and thus the positive clinical trial data on kidney function outcome measures may, in part, be mediated by inhibition of fibrosis.

3.4. Pulmonary Fibrosis

Fibrosis of the lung disrupts alveolar architecture and impairs gas exchange, representing a central pathological feature of fibrotic interstitial lung diseases. Given the limited efficacy of current anti-fibrotic therapies and the substantial morbidity associated with progressive pulmonary fibrosis, identification of novel pathways capable of modulating fibroblast activation and ECM remodelling remains a major therapeutic priority. In this context, interest has emerged in incretin receptor agonists as potential modulators of pulmonary fibrotic pathways, although the supporting evidence remains preliminary.

Clinical data directly evaluating the impact of incretin receptor agonists on pulmonary fibrosis are limited. In a meta-analysis of large randomized controlled trials of GLP-1 receptor agonists in type 2 diabetes, the incidence of pulmonary fibrosis and interstitial lung disease events was lower in treated patients compared with controls, although absolute event rates were extremely low and differences did not reach statistical significance [63]. A larger meta-analysis encompassing over 77,000 participants similarly reported a reduced overall risk of respiratory diseases with GLP-1 receptor agonist treatment, but pulmonary fibrosis was not analysed as a discrete outcome, and no fibrotic endpoints were prospectively assessed [64]. Importantly, none of these studies incorporated imaging, physiological, or histopathological measures of lung fibrosis, precluding conclusions regarding anti-fibrotic clinical efficacy of GLP-1 agonists in pulmonary fibrosis.

Preclinical in vitro evidence for the efficacy of incretin receptor agonists is derived primarily from epithelial, immune, and vascular cellular models rather than from direct studies of lung fibroblasts. As such, the data suggest that incretin receptor agonists may modulate cellular pathways that initiate and amplify fibrotic remodelling in the lung. For example, in alveolar macrophages, GLP-1 receptor agonism suppressed activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome and reduced production of IL-1β [65], an effect in part mediated by the disruption of histone lactylation, a recognised regulator of pro-fibrotic gene expression [65]. In immortalised human airway epithelial cell lines (including bronchial epithelial cells) and human alveolar epithelial–like cells, GLP-1 receptor agonists reduced epithelial stress and inflammatory signalling, including downregulation of epithelial-derived cytokines, including IL-33 and thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP), both of which are implicated in epithelial–mesenchymal crosstalk and fibroblast recruitment in fibrotic lung disease [66,67,68]. Additionally, liraglutide and exendin-4 inhibited platelet-derived growth factor BB (PDGF-BB)-mediated proliferation and migration of pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells [69,70].

In vivo, studies directly modelling pulmonary fibrosis remain sparse and have shown converse results. In murine models of bleomycin-induced lung injury, genetic deletion of the GLP-1 receptor was associated with reduced inflammatory injury, and pharmacological GLP-1 receptor activation exacerbated pulmonary inflammation [71]. In contrast, multiple rodent pulmonary hypertension models demonstrate that GLP-1 receptor agonists, including exendin-4 and liraglutide, reduce vascular remodelling, inflammation, and ventricular hypertrophy via endothelial nitric oxide signalling and suppression of endothelin-1 pathways [68,69,72,73]. Furthermore, a recent study using a dual-sensitive, gelatin-coated chitosan microparticle formulation for pulmonary delivery of semaglutide significantly attenuated bleomycin-induced lung fibrosis in vivo, with reductions in inflammatory signalling (TLR4/NF-κB), fibrogenic mediators (TGF-β1, p-SMAD3), and markers of ECM deposition α-SMA and Col1a1 [74].

In summary, evidence supporting a therapeutic role for incretin receptor agonists in pulmonary fibrosis is promising but inconclusive. Clinical studies suggest a favourable respiratory safety profile and a possible reduction in fibrotic events, but lack fibrosis-specific endpoints. Preclinical data indicate modulation of inflammatory and pro-fibrotic signalling pathways relevant to lung fibrosis, yet direct demonstration of reduced fibroblast activation or collagen deposition in established pulmonary fibrosis models is currently lacking. Therefore, further targeted in vivo and human-relevant mechanistic studies are required to determine whether incretin receptor agonism can meaningfully modify fibrotic progression in pulmonary disease.

3.5. Osteoarthritis and Synovial Joint Fibrosis

The potential for incretin receptor agonists as therapeutics for disease modification and/or pain in OA is supported by epidemiology and by both clinical and preclinical studies, which suggest direct and indirect mechanisms of efficacy. Firstly, epidemiologically, obesity is an established risk factor for the development of OA; individuals with obesity are 3–5 times more likely to develop OA [75], and most OA patients undergoing total joint replacement surgery for end-stage OA have obesity or are overweight [76].

In clinical studies, once-weekly administration of the GLP-1 agonist semaglutide in knee OA patients with obesity reduced patient-reported pain scores (WOMAC) over 68 weeks compared with placebo. With both groups receiving counselling on physical activity and a reduced calorie diet [77]. Furthermore, a retrospective analysis of a Chinese cohort of knee OA patients with type 2 diabetes, those patients who had been prescribed a GLP-1 agonist (including liraglutide, semaglutide or other), exhibited reduced cartilage volume loss after 2 years, compared to those patients who had not been prescribed a GLP-1 agonist [78]. Given that both of these studies were in patients with OA of the knee (a load-bearing joint), it is likely that a significant proportion of the efficacy observed was due to the significant loss of body weight, reducing pathological joint loading. Indeed, diet-induced weight loss in knee or hip OA patients has previously been shown to slow disease progression, improve joint function, and reduce joint pain [79]. Furthermore, the reduction in adipose tissue mass likely reduced obesity-associated systemic inflammation by reducing the release of pro-inflammatory adipokines, which can drive cartilage degeneration [80] and abnormal subchondral bone remodelling [81].

However, emerging evidence suggests that incretin receptor agonists may also have direct effects on the activity of diseased synovial joint cells. Historically, OA was considered purely a “wear and tear” degenerative disease of the cartilage. However, in recent years, it has been increasingly recognised as a disease involving significant synovial inflammation (synovitis) [82,83]. In OA, the synovial joint lining tissue (synovium) undergoes a fibrotic transformation, with TGF-β a key regulator driving an influx of inflammatory immune cells and the activation of resident synovial fibroblasts. Latent and active forms of TGF-β are detected in OA synovial fluid [84], but are present at much lower levels, or are undetectable, in healthy non-arthritic synovial fluid [85]. Intra-articular injection of C57Bl/6 mice with an adenovirus vector overexpressing active TGF-β [86] or repeated in-articular injections of recombinant TGF-β induced hyperplasia of synovium with increases in inflammatory immune cells, including macrophages [87]. Interestingly, the activated fibroblast phenotype, which is more proliferative and pro-inflammatory, is particularly pronounced in OA patients with obesity [88,89,90], even in non-load bearing joints i.e., hands [91]. This inflammatory synovial fibroblast phenotype exacerbates cartilage degeneration, via the induction of matrix metalloproteases (MMPs) and aggrecanases (ADAMTS4/5), and sensitises the growth and activity of joint nociceptors [92,93,94]. Thus, synovial fibrosis is likely a central mediator of both progression in the loss of joint integrity, and patient’s perception of joint pain.

Critically, preclinical evidence supports direct benefits of incretin receptors in modulating OA synovial fibrosis. In vivo, in a murine monoiodoacetate (MIA)-induced model of OA, a single intra-articular injection of liraglutide reduced synovitis severity, whilst weekly intra-articular injections attenuated behaviour pain responses [95]. Importantly, no difference in weight was observed between the liraglutide and vehicle control groups. In a rat MIA model, Que et al. [96] found that sub-cutaneous administration of for 28 days liraglutide reduced pro-inflammatory cytokines in cartilage, whilst in a surgically induced (ACL transection) rat model of OA, subcutaneous Liraglutide reduced histological signs of cartilage degradation [97].

These findings are supported by in vitro studies using either murine or human cells. Predominantly, these studies have been conducted in chondrocyte cells rather than synovial fibroblasts. Nevertheless, the available data indicate that incretin receptor agonism exerts direct immunomodulatory effects, which would be expected to reduce synovial inflammation and fibrosis. In rodent primary chondrocytes, Liraglutide inhibited AGEs- or IL-1β-induced expression and release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including iNOS, TNF-α and IL-6 [95,98]. Similarly, in the human chondrocyte SW1353 cell line, dulaglutide inhibited AGEs-induced activation of NFkB and the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines [99], whilst in human knee OA primary articular chondrocytes, lixisenatide reduced mRNA ad protein expression of TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-7 [100].

Therefore, incretin receptor agonists likely exert a multimodal therapeutic effect in OA. Although substantial weight loss can reduce pathological joint loading and systemic inflammation, the direct pharmacological effects on synovial fibroblasts—attenuating their inflammatory signalling and fibrotic activation may offer an additional, disease-modifying and analgesic mechanism that targets the local synovial environment, driving pain and structural progression. Collectively, these findings provide a strong rationale for the therapeutic repurposing of incretin receptor agonists to address the unmet clinical need for treatments that modify disease and alleviate joint pain in OA patients.

4. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

The collective evidence positions incretin receptor agonists as a unique class of drugs with multi-organ anti-fibrotic potential, now extending to fibro-inflammatory diseases like osteoarthritis. Their ability to target both direct (TGF-β inhibition) and indirect (metabolic, inflammatory) drivers of fibrosis may provide a powerful, synergistic therapeutic approach. However, key knowledge gaps remain. The relative contributions of the direct effects of incretin receptor agonists on fibrosis versus the secondary effects of weight loss and systemic reductions in inflammation remain to be delineated. It is also unclear if specific incretin receptor agonists, for example selective GIP receptor and GLP-1 receptor agonists will possess different efficacies across tissue types.

A critical challenge for future clinical studies will be the robust assessment of treatment effects on in situ fibrosis. Across organ systems, this will require incorporation of validated imaging modalities and circulating or tissue-based biomarkers of fibrogenesis and matrix turnover. In liver disease, non-invasive approaches such as transient elastography, magnetic resonance elastography (MRE), and serum fibrosis panels (e.g., ELF score, Pro-C3) can be readily applied in incretin-based trials. In cardiovascular disease, emerging cardiac MRI techniques, including T1 mapping and extracellular volume fraction, offer quantitative assessment of myocardial fibrosis, while circulating collagen turnover markers may provide complementary information. In chronic kidney disease, urinary and plasma biomarkers of fibrosis, together with functional MRI approaches, represent promising tools, although further validation is required. In pulmonary fibrosis, high-resolution CT combined with quantitative imaging analysis and circulating markers of epithelial injury and matrix remodelling may enable the detection of fibrotic change. In OA, contrast-enhanced MRI, ultrasound-based assessment of synovitis, and synovial fluid or serum biomarkers of fibrosis and inflammation could be leveraged to directly assess changes in synovial fibro-inflammatory pathology. Integration of such modalities into future trials will be essential to distinguish true anti-fibrotic effects from indirect improvements driven by weight loss or systemic metabolic changes.

Future research should focus on designing clinical trials that use fibrosis regression or synovitis reduction as primary endpoints in diseases like osteoarthritis, employing advanced imaging or histological techniques. Additional priorities include evaluating incretin receptor agonists in fibrotic diseases where diabetes is not a major comorbidity, such as idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis or in osteoarthritis; exploring combination therapies with other anti-fibrotic or specific disease-modifying drugs; and deepening mechanistic investigations to clarify direct mechanisms of incretin receptor signalling in fibroblasts and immune cells across different tissue types.

In conclusion, preclinical and emerging clinical evidence are changing the paradigm, viewing incretin receptor agonists solely as metabolic-based therapeutics for treating obesity and diabetes to recognising them as multifaceted agents with significant disease-modifying potential for inflammatory fibrotic disorders across different organ systems. By exerting direct effects that modulate key pro-fibrotic pathways and reduce drivers of inflammation, incretin receptor agonists offer a promising approach for treating a broad spectrum of fibrotic and fibro-inflammatory disorders.

Acknowledgements

The study of the literature was carried out at the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Birmingham Biomedical Research Centre (BRC).

Ethics Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Funding

S.W.J. has received funding from the Medical Research Council [MR/W026961/1] and Arthritis UK (21530, 21812), which contributed to the original research articles summarised in this review.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The author declares that he has no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Mutsaers HAM, Merrild C, Norregaard R, Plana-Ripoll O. The impact of fibrotic diseases on global mortality from 1990 to 2019. J. Transl. Med. 2023, 21, 818. DOI:10.1186/s12967-023-04690-7 [Google Scholar]

- Rim YA, Ju JH. The Role of Fibrosis in Osteoarthritis Progression. Life 2020, 11, 3. DOI:10.3390/life11010003 [Google Scholar]

- Damerau A, Rosenow E, Alkhoury D, Buttgereit F, Gaber T. Fibrotic pathways and fibroblast-like synoviocyte phenotypes in osteoarthritis. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1385006. DOI:10.3389/fimmu.2024.1385006 [Google Scholar]

- Dees C, Chakraborty D, Distler JHW. Cellular and molecular mechanisms in fibrosis. Exp. Dermatol. 2021, 30, 121–131. DOI:10.1111/exd.14193 [Google Scholar]

- Duarte S, Baber J, Fujii T, Coito AJ. Matrix metalloproteinases in liver injury, repair and fibrosis. Matrix Biol. 2015, 44–46, 147–156. DOI:10.1016/j.matbio.2015.01.004 [Google Scholar]

- Caligiuri A, Gentilini A, Pastore M, Gitto S, Marra F. Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms Underlying Liver Fibrosis Regression. Cells 2021, 10, 2759. DOI:10.3390/cells10102759 [Google Scholar]

- Kisseleva T, Brenner D. Molecular and cellular mechanisms of liver fibrosis and its regression. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 18, 151–166. DOI:10.1038/s41575-020-00372-7 [Google Scholar]

- Mo C, Yan M, Tang XX, Shichino S, Bagnato G. Editorial: Cellular and molecular mechanisms of lung regeneration, repair, and fibrosis. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2024, 11, 1346875. DOI:10.3389/fcell.2023.1346875 [Google Scholar]

- Smith RS, Smith TJ, Blieden TM, Phipps RP. Fibroblasts as sentinel cells. Synthesis of chemokines and regulation of inflammation. Am. J. Pathol. 1997, 151, 317–322. [Google Scholar]

- Buckley CD, Pilling D, Lord JM, Akbar AN, Scheel-Toellner D, Salmon M. Fibroblasts regulate the switch from acute resolving to chronic persistent inflammation. Trends Immunol. 2001, 22, 199–204. DOI:10.1016/S1471-4906(01)01863-4 [Google Scholar]

- Richeldi L, du Bois RM, Raghu G, Azuma A, Brown KK, Costabel U, et al. Efficacy and safety of nintedanib in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 370, 2071–2082. DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa1402584 [Google Scholar]

- Wollin L, Distler JHW, Redente EF, Riches DWH, Stowasser S, Schlenker-Herceg R, et al. Potential of nintedanib in treatment of progressive fibrosing interstitial lung diseases. Eur. Respir. J. 2019, 54, 1900161. DOI:10.1183/13993003.00161-2019 [Google Scholar]

- Garvey WT, Batterham RL, Bhatta M, Buscemi S, Christensen LN, Frias JP, et al. Two-year effects of semaglutide in adults with overweight or obesity: the STEP 5 trial. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 2083–2091. DOI:10.1038/s41591-022-02026-4 [Google Scholar]

- Verma S, Bhatta M, Davies M, Deanfield JE, Garvey WT, Jensen C, et al. Effects of once-weekly semaglutide 2.4 mg on C-reactive protein in adults with overweight or obesity (STEP 1, 2, and 3): Exploratory analyses of three randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trials. eClinicalMedicine 2023, 55, 101737. DOI:10.1016/j.eclinm.2022.101737 [Google Scholar]

- Foghsgaard S, Vedtofte L, Andersen ES, Bahne E, Andreasen C, Sorensen AL, et al. Liraglutide treatment for the prevention of glucose tolerance deterioration in women with prior gestational diabetes mellitus: A 52-week randomized controlled clinical trial. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2024, 26, 201–214. DOI:10.1111/dom.15306 [Google Scholar]

- Pyke C, Heller RS, Kirk RK, Orskov C, Reedtz-Runge S, Kaastrup P, et al. GLP-1 receptor localization in monkey and human tissue: Novel distribution revealed with extensively validated monoclonal antibody. Endocrinology 2014, 155, 1280–1290. DOI:10.1210/en.2013-1934 [Google Scholar]

- Heppner KM, Kirigiti M, Secher A, Paulsen SJ, Buckingham R, Pyke C, et al. Expression and distribution of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor mRNA, protein and binding in the male nonhuman primate (Macaca mulatta) brain. Endocrinology 2015, 156, 255–267. DOI:10.1210/en.2014-1675 [Google Scholar]

- Uhlen M, Fagerberg L, Hallstrom BM, Lindskog C, Oksvold P, Mardinoglu A, et al. Tissue-based map of the human proteome. Science 2015, 347, 1260419. DOI:10.1126/science.1260419 [Google Scholar]

- Salminen A. AMPK signaling inhibits the differentiation of myofibroblasts: Impact on age-related tissue fibrosis and degeneration. Biogerontology 2024, 25, 83–106. DOI:10.1007/s10522-023-10072-9 [Google Scholar]

- Wei H, Bu R, Yang Q, Jia J, Li T, Wang Q, et al. Exendin-4 Protects against Hyperglycemia-Induced Cardiomyocyte Pyroptosis via the AMPK-TXNIP Pathway. J. Diabetes Res. 2019, 2019, 8905917. DOI:10.1155/2019/8905917 [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y, He X, Chen Y, Huang Y, Wu L, He J. Exendin-4 attenuates cardiac hypertrophy via AMPK/mTOR signaling pathway activation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2015, 468, 394–399. DOI:10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.09.179 [Google Scholar]

- Li R, Sun X, Li P, Li W, Zhao L, Zhu L, et al. GLP-1-Induced AMPK Activation Inhibits PARP-1 and Promotes LXR-Mediated ABCA1 Expression to Protect Pancreatic beta-Cells Against Cholesterol-Induced Toxicity Through Cholesterol Efflux. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 646113. DOI:10.3389/fcell.2021.646113 [Google Scholar]

- Andreozzi F, Raciti GA, Nigro C, Mannino GC, Procopio T, Davalli AM, et al. The GLP-1 receptor agonists exenatide and liraglutide activate Glucose transport by an AMPK-dependent mechanism. J. Transl. Med. 2016, 14, 229. DOI:10.1186/s12967-016-0985-7 [Google Scholar]

- Derynck R, Zhang YE. Smad-dependent and Smad-independent pathways in TGF-beta family signalling. Nature 2003, 425, 577–584. DOI:10.1038/nature02006 [Google Scholar]

- Kuo CY, Tsou SH, Kornelius E, Chan KC, Chang KW, Li JC, et al. The protective effects of liraglutide in reducing lipid droplets accumulation and myocardial fibrosis in diabetic cardiomyopathy. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2025, 82, 39. DOI:10.1007/s00018-024-05558-9 [Google Scholar]

- Fathy MA, Alsemeh AE, Habib MA, Abdel-Nour HM, Hendawy DM, Eltaweel AM, et al. Liraglutide ameliorates diabetic-induced testicular dysfunction in male rats: role of GLP-1/Kiss1/GnRH and TGF-beta/Smad signaling pathways. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1224985. DOI:10.3389/fphar.2023.1224985 [Google Scholar]

- Tsai TH, Lee CH, Cheng CI, Fang YN, Chung SY, Chen SM, et al. Liraglutide Inhibits Endothelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition and Attenuates Neointima Formation after Endovascular Injury in Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetic Mice. Cells 2019, 8, 589. DOI:10.3390/cells8060589 [Google Scholar]

- Twarda-Clapa A, Olczak A, Bialkowska AM, Koziolkiewicz M. Advanced Glycation End-Products (AGEs): Formation, Chemistry, Classification, Receptors, and Diseases Related to AGEs. Cells 2022, 11, 1312. DOI:10.3390/cells11081312 [Google Scholar]

- Zhao LM, Zhang W, Wang LP, Li GR, Deng XL. Advanced glycation end products promote proliferation of cardiac fibroblasts by upregulation of KCa3.1 channels. Pflugers Arch. 2012, 464, 613–621. DOI:10.1007/s00424-012-1165-0 [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein RH, Poliks CF, Pilch PF, Smith BD, Fine A. Stimulation of collagen formation by insulin and insulin-like growth factor I in cultures of human lung fibroblasts. Endocrinology 1989, 124, 964–970. DOI:10.1210/endo-124-2-964 [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Li M, Liu L, Zhu D, Tian G. Telmisartan improves myocardial remodeling by inhibiting leptin autocrine activity and activating PPARgamma. Exp. Biol. Med. 2020, 245, 654–666. DOI:10.1177/1535370220908215 [Google Scholar]

- Park PH, Sanz-Garcia C, Nagy LE. Adiponectin as an anti-fibrotic and anti-inflammatory adipokine in the liver. Curr. Pathobiol. Rep. 2015, 3, 243–252. DOI:10.1007/s40139-015-0094-y [Google Scholar]

- Chemaly ER, Kang S, Zhang S, McCollum L, Chen J, Benard L, et al. Differential patterns of replacement and reactive fibrosis in pressure and volume overload are related to the propensity for ischaemia and involve resistin. J. Physiol. 2013, 591, 5337–5355. DOI:10.1113/jphysiol.2013.258731 [Google Scholar]

- Han X, Zhang Y, Zhang X, Ji H, Wang W, Qiao O, et al. Targeting adipokines: A new strategy for the treatment of myocardial fibrosis. Pharmacol. Res. 2022, 181, 106257. DOI:10.1016/j.phrs.2022.106257 [Google Scholar]

- Liu QK. Mechanisms of action and therapeutic applications of GLP-1 and dual GIP/GLP-1 receptor agonists. Front. Endocrinol. 2024, 15, 1431292. DOI:10.3389/fendo.2024.1431292 [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong MJ, Gaunt P, Aithal GP, Barton D, Hull D, Parker R, et al. Liraglutide safety and efficacy in patients with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (LEAN): A multicentre, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled phase 2 study. Lancet 2016, 387, 679–690. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00803-X [Google Scholar]

- Sanyal AJ, Newsome PN, Kliers I, Ostergaard LH, Long MT, Kjaer MS, et al. Phase 3 Trial of Semaglutide in Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatohepatitis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2025, 392, 2089–2099. DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa2413258 [Google Scholar]

- Hawary OA, Wadie W, El-Said YAM, Hassan OF. Repurposing of semaglutide by targeting SIRT1 and TGF-beta/Smad signaling in hepatic fibrosis. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Arch. Pharmacol. 2025. DOI:10.1007/s00210-025-04675-x [Google Scholar]

- da Silva Lima N, Cabaleiro A, Novoa E, Riobello C, Knerr PJ, He Y, et al. GLP-1 and GIP agonism has no direct actions in human hepatocytes or hepatic stellate cells. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2024, 81, 468. DOI:10.1007/s00018-024-05507-6 [Google Scholar]

- Marso SP, Daniels GH, Brown-Frandsen K, Kristensen P, Mann JF, Nauck MA, et al. Liraglutide and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Type 2 Diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 311–322. DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa1603827 [Google Scholar]

- Marso SP, Bain SC, Consoli A, Eliaschewitz FG, Jodar E, Leiter LA, et al. Semaglutide and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 1834–1844. DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa1607141 [Google Scholar]

- Gerstein HC, Colhoun HM, Dagenais GR, Diaz R, Lakshmanan M, Pais P, et al. Dulaglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes (REWIND): A double-blind, randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2019, 394, 121–130. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31149-3 [Google Scholar]

- Ryan DH, Lingvay I, Colhoun HM, Deanfield J, Emerson SS, Kahn SE, et al. Semaglutide Effects on Cardiovascular Outcomes in People With Overweight or Obesity (SELECT) rationale and design. Am. Heart J. 2020, 229, 61–69. DOI:10.1016/j.ahj.2020.07.008 [Google Scholar]

- Bizino MB, Jazet IM, Westenberg JJM, van Eyk HJ, Paiman EHM, Smit JWA, et al. Effect of liraglutide on cardiac function in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: Randomized placebo-controlled trial. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2019, 18, 55. DOI:10.1186/s12933-019-0857-6 [Google Scholar]

- Verma S, Mazer CD, Yan AT, Mason T, Garg V, Teoh H, et al. Effect of Empagliflozin on Left Ventricular Mass in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Coronary Artery Disease: The EMPA-HEART CardioLink-6 Randomized Clinical Trial. Circulation 2019, 140, 1693–1702. DOI:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.042375 [Google Scholar]

- Kosiborod MN, Abildstrom SZ, Borlaug BA, Butler J, Rasmussen S, Davies M, et al. Semaglutide in Patients with Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction and Obesity. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 389, 1069–1084. DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa2306963 [Google Scholar]

- Jorsal A, Kistorp C, Holmager P, Tougaard RS, Nielsen R, Hanselmann A, et al. Effect of liraglutide, a glucagon-like peptide-1 analogue, on left ventricular function in stable chronic heart failure patients with and without diabetes (LIVE)-a multicentre, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2017, 19, 69–77. DOI:10.1002/ejhf.657 [Google Scholar]

- Xie S, Zhang M, Shi W, Xing Y, Huang Y, Fang WX, et al. Long-Term Activation of Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor by Dulaglutide Prevents Diabetic Heart Failure and Metabolic Remodeling in Type 2 Diabetes. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2022, 11, e026728. DOI:10.1161/JAHA.122.026728 [Google Scholar]

- Pan X, Yue L, Ban J, Ren L, Chen S. Effects of Semaglutide on Cardiac Protein Expression and Cardiac Function of Obese Mice. J. Inflamm. Res. 2022, 15, 6409–6425. DOI:10.2147/JIR.S391859 [Google Scholar]

- Noyan-Ashraf MH, Momen MA, Ban K, Sadi AM, Zhou YQ, Riazi AM, et al. GLP-1R agonist liraglutide activates cytoprotective pathways and improves outcomes after experimental myocardial infarction in mice. Diabetes 2009, 58, 975–983. DOI:10.2337/db08-1193 [Google Scholar]

- Guan G, Zhang J, Liu S, Huang W, Gong Y, Gu X. Glucagon-like peptide-1 attenuates endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced apoptosis in H9c2 cardiomyocytes during hypoxia/reoxygenation through the GLP-1R/PI3K/Akt pathways. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 2019, 392, 715–722. DOI:10.1007/s00210-019-01625-2 [Google Scholar]

- Mann JFE, Orsted DD, Brown-Frandsen K, Marso SP, Poulter NR, Rasmussen S, et al. Liraglutide and Renal Outcomes in Type 2 Diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 839–848. DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa1616011 [Google Scholar]

- Kaul S. Mitigating Cardiovascular Risk in Type 2 Diabetes with Antidiabetes Drugs: A Review of Principal Cardiovascular Outcome Results of EMPA-REG OUTCOME, LEADER, and SUSTAIN-6 Trials. Diabetes Care 2017, 40, 821–831. DOI:10.2337/dc17-0291 [Google Scholar]

- Gerstein HC, Colhoun HM, Dagenais GR, Diaz R, Lakshmanan M, Pais P, et al. Dulaglutide and renal outcomes in type 2 diabetes: An exploratory analysis of the REWIND randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2019, 394, 131–138. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31150-X [Google Scholar]

- Martinez Leon V, Hilburg R, Susztak K. Mechanisms of diabetic kidney disease and established and emerging treatments. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2026, 22, 21–35. DOI:10.1038/s41574-025-01171-3 [Google Scholar]

- Li YK, Ma DX, Wang ZM, Hu XF, Li SL, Tian HZ, et al. The glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) analog liraglutide attenuates renal fibrosis. Pharmacol. Res. 2018, 131, 102–111. DOI:10.1016/j.phrs.2018.03.004 [Google Scholar]

- Hendarto H, Inoguchi T, Maeda Y, Ikeda N, Zheng J, Takei R, et al. GLP-1 analog liraglutide protects against oxidative stress and albuminuria in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats via protein kinase A-mediated inhibition of renal NAD(P)H oxidases. Metabolism 2012, 61, 1422–1434. DOI:10.1016/j.metabol.2012.03.002 [Google Scholar]

- Kodera R, Shikata K, Kataoka HU, Takatsuka T, Miyamoto S, Sasaki M, et al. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist ameliorates renal injury through its anti-inflammatory action without lowering blood glucose level in a rat model of type 1 diabetes. Diabetologia 2011, 54, 965–978. DOI:10.1007/s00125-010-2028-x [Google Scholar]

- Jia Y, Zheng Z, Guan M, Zhang Q, Li Y, Wang L, et al. Exendin-4 ameliorates high glucose-induced fibrosis by inhibiting the secretion of miR-192 from injured renal tubular epithelial cells. Exp. Mol. Med. 2018, 50, 1–13. DOI:10.1038/s12276-018-0084-3 [Google Scholar]

- Chang JT, Liang YJ, Hsu CY, Chen CY, Chen PJ, Yang YF, et al. Glucagon-like peptide receptor agonists attenuate advanced glycation end products-induced inflammation in rat mesangial cells. BMC Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2017, 18, 67. DOI:10.1186/s40360-017-0172-3 [Google Scholar]

-

Li W, Cui M, Wei Y, Kong X, Tang L, Xu D. Inhibition of the expression of TGF-beta1 and CTGF in human mesangial cells by exendin-4, a glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist. Cell Physiol. Biochem. 2012, 30, 749–757. DOI:10.1159/000341454 [Google Scholar]

-

Xu WW, Guan MP, Zheng ZJ, Gao F, Zeng YM, Qin Y, et al. Exendin-4 alleviates high glucose-induced rat mesangial cell dysfunction through the AMPK pathway. Cell Physiol. Biochem. 2014, 33, 423–432. DOI:10.1159/000358623 [Google Scholar]

- Wei JP, Yang CL, Leng WH, Ding LL, Zhao GH. Use of GLP1RAs and occurrence of respiratory disorders: A meta-analysis of large randomized trials of GLP1RAs. Clin. Respir. J. 2021, 15, 847–850. DOI:10.1111/crj.13372 [Google Scholar]

- Yu M, Wang R, Pei L, Zhang X, Wei J, Wen Y, et al. The relationship between the use of GLP-1 receptor agonists and the incidence of respiratory illness: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2023, 15, 164. DOI:10.1186/s13098-023-01118-6 [Google Scholar]

- Liu C, Zhang Q, Zhou H, Jin L, Liu C, Yang M, et al. GLP-1R activation attenuates the progression of pulmonary fibrosis via disrupting NLRP3 inflammasome/PFKFB3-driven glycolysis interaction and histone lactylation. J. Transl. Med. 2024, 22, 954. DOI:10.1186/s12967-024-05753-z [Google Scholar]

- Kantreva K, Katsaounou P, Saltiki K, Trakada G, Ntali G, Stratigou T, et al. The possible effect of anti-diabetic agents GLP-1RA and SGLT-2i on the respiratory system function. Endocrine 2025, 87, 378–388. DOI:10.1007/s12020-024-04033-6 [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen DV, Linderholm A, Haczku A, Kenyon N. Glucagon-like peptide 1: A potential anti-inflammatory pathway in obesity-related asthma. Pharmacol. Ther. 2017, 180, 139–143. DOI:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2017.06.012 [Google Scholar]

- Wu AY, Peebles RS. The GLP-1 receptor in airway inflammation in asthma: A promising novel target? Expert. Rev. Clin. Immunol. 2021, 17, 1053–1057. DOI:10.1080/1744666X.2021.1971973 [Google Scholar]

- Lee MY, Tsai KB, Hsu JH, Shin SJ, Wu JR, Yeh JL. Liraglutide prevents and reverses monocrotaline-induced pulmonary arterial hypertension by suppressing ET-1 and enhancing eNOS/sGC/PKG pathways. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 31788. DOI:10.1038/srep31788 [Google Scholar]

- Wu YC, Wang WT, Lee SS, Kuo YR, Wang YC, Yen SJ, et al. Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonist Attenuates Autophagy to Ameliorate Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension through Drp1/NOX- and Atg-5/Atg-7/Beclin-1/LC3beta Pathways. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3435. DOI:10.3390/ijms20143435 [Google Scholar]

- Sato T, Shimizu T, Fujita H, Imai Y, Drucker DJ, Seino Y, et al. GLP-1 Receptor Signaling Differentially Modifies the Outcomes of Sterile vs Viral Pulmonary Inflammation in Male Mice. Endocrinology 2020, 161, bqaa201. DOI:10.1210/endocr/bqaa201 [Google Scholar]

- Roan JN, Hsu CH, Fang SY, Tsai HW, Luo CY, Huang CC, et al. Exendin-4 improves cardiovascular function and survival in flow-induced pulmonary hypertension. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2018, 155, 1661–1669.e4. DOI:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2017.10.085 [Google Scholar]

- Honda J, Kimura T, Sakai S, Maruyama H, Tajiri K, Murakoshi N, et al. The glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist liraglutide improves hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension in mice partly via normalization of reduced ET(B) receptor expression. Physiol. Res. 2018, 67 (Suppl. S1), S175–S184. DOI:10.33549/physiolres.933822 [Google Scholar]

- Hamad RS, Kira AY, Saber S, Alharbi MS, Alsaykhan H, Ahmed SS, et al. Dual-sensitive gelatin-coated chitosan microparticles for targeted semaglutide pulmonary delivery: A novel approach to enhancing anti-inflammatory and anti-fibrotic effects. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2025, 165, 115480. DOI:10.1016/j.intimp.2025.115480 [Google Scholar]

- Holliday KL, McWilliams DF, Maciewicz RA, Muir KR, Zhang W, Doherty M. Lifetime body mass index, other anthropometric measures of obesity and risk of knee or hip osteoarthritis in the GOAL case-control study. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2011, 19, 37–43. DOI:10.1016/j.joca.2010.10.014 [Google Scholar]

- Johnson CA, White CC, Kunkle BF, Eichinger JK, Friedman RJ. Effects of the Obesity Epidemic on Total Hip and Knee Arthroplasty Demographics. J. Arthroplasty 2021, 36, 3097–3100. DOI:10.1016/j.arth.2021.04.017 [Google Scholar]

- Bliddal H, Bays H, Czernichow S, Udden Hemmingsson J, Hjelmesaeth J, Hoffmann Morville T, et al. Once-Weekly Semaglutide in Persons with Obesity and Knee Osteoarthritis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 391, 1573–1583. DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa2403664 [Google Scholar]

- Zhu H, Zhou L, Wang Q, Cai Q, Yang F, Jin H, et al. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists as a disease-modifying therapy for knee osteoarthritis mediated by weight loss: Findings from the Shanghai Osteoarthritis Cohort. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2023, 82, 1218–1226. DOI:10.1136/ard-2023-223845 [Google Scholar]

- Cull M. Weight loss for obese patients as a treatment of hip and knee osteoarthritis: A scoping review. J. Metab. Health 2024, 7, 97. DOI:10.4102/jmh.v7i1.97 [Google Scholar]

- Philp AM, Butterworth S, Davis ET, Jones SW. eNAMPT Is Localised to Areas of Cartilage Damage in Patients with Hip Osteoarthritis and Promotes Cartilage Catabolism and Inflammation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6719. DOI:10.3390/ijms22136719 [Google Scholar]

- Philp AM, Collier RL, Grover LM, Davis ET, Jones SW. Resistin promotes the abnormal Type I collagen phenotype of subchondral bone in obese patients with end stage hip osteoarthritis. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 4042. DOI:10.1038/s41598-017-04119-4 [Google Scholar]

- Tonge DP, Pearson MJ, Jones SW. The hallmarks of osteoarthritis and the potential to develop personalised disease-modifying pharmacological therapeutics. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2014, 22, 609–621. DOI:10.1016/j.joca.2014.03.004 [Google Scholar]

- Philp AM, Davis ET, Jones SW. Developing anti-inflammatory therapeutics for patients with osteoarthritis. Rheumatology 2017, 56, 869–881. DOI:10.1093/rheumatology/kew278 [Google Scholar]

- Fava R, Olsen N, Keski-Oja J, Moses H, Pincus T. Active and latent forms of transforming growth factor beta activity in synovial effusions. J. Exp. Med. 1989, 169, 291–296. DOI:10.1084/jem.169.1.291 [Google Scholar]

- van der Kraan PM. Differential Role of Transforming Growth Factor-beta in an Osteoarthritic or a Healthy Joint. J. Bone Metab. 2018, 25, 65–72. DOI:10.11005/jbm.2018.25.2.65 [Google Scholar]

- Bakker AC, van de Loo FA, van Beuningen HM, Sime P, van Lent PL, van der Kraan PM, et al. Overexpression of active TGF-beta-1 in the murine knee joint: Evidence for synovial-layer-dependent chondro-osteophyte formation. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2001, 9, 128–136. DOI:10.1053/joca.2000.0368 [Google Scholar]

- van Beuningen HM, van der Kraan PM, Arntz OJ, van den Berg WB. Transforming growth factor-beta 1 stimulates articular chondrocyte proteoglycan synthesis and induces osteophyte formation in the murine knee joint. Lab. Investig. 1994, 71, 279–290. [Google Scholar]

- Pearson MJ, Herndler-Brandstetter D, Tariq MA, Nicholson TA, Philp AM, Smith HL, et al. IL-6 secretion in osteoarthritis patients is mediated by chondrocyte-synovial fibroblast cross-talk and is enhanced by obesity. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 3451. DOI:10.1038/s41598-017-03759-w [Google Scholar]

- Nanus DE, Wijesinghe SN, Pearson MJ, Hadjicharalambous MR, Rosser A, Davis ET, et al. Regulation of the Inflammatory Synovial Fibroblast Phenotype by Metastasis-Associated Lung Adenocarcinoma Transcript 1 Long Noncoding RNA in Obese Patients with Osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2020, 72, 609–619. DOI:10.1002/art.41158 [Google Scholar]

- Farah H, Wijesinghe SN, Nicholson T, Alnajjar F, Certo M, Alghamdi A, et al. Differential Metabotypes in Synovial Fibroblasts and Synovial Fluid in Hip Osteoarthritis Patients Support Inflammatory Responses. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 3266. DOI:10.3390/ijms23063266 [Google Scholar]

- Wijesinghe SN, Badoume A, Nanus DE, Sharma-Oates A, Farah H, Certo M, et al. Obesity defined molecular endotypes in the synovium of patients with osteoarthritis provides a rationale for therapeutic targeting of fibroblast subsets. Clin. Transl. Med. 2023, 13, e1232. DOI:10.1002/ctm2.1232 [Google Scholar]

- Pattison LA, Rickman RH, Hilton H, Dannawi M, Wijesinghe SN, Ladds G, et al. Activation of the proton-sensing GPCR, GPR65 on fibroblast-like synoviocytes contributes to inflammatory joint pain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2410653121. DOI:10.1073/pnas.2410653121 [Google Scholar]

- Wijesinghe SN, Ditchfield C, Flynn S, Agrawal J, Davis ET, Dajas-Bailador F, et al. Immunomodulation and fibroblast dynamics driving nociceptive joint pain within inflammatory synovium: Unravelling mechanisms for therapeutic advancements in osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2024, 32, 1358–1370. DOI:10.1016/j.joca.2024.06.011 [Google Scholar]

- Nanus DE, Badoume A, Wijesinghe SN, Halsey AM, Hurley P, Ahmed Z, et al. Synovial tissue from sites of joint pain in knee osteoarthritis patients exhibits a differential phenotype with distinct fibroblast subsets. eBioMedicine 2021, 72, 103618. DOI:10.1016/j.ebiom.2021.103618 [Google Scholar]

- Meurot C, Martin C, Sudre L, Breton J, Bougault C, Rattenbach R, et al. Liraglutide, a glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonist, exerts analgesic, anti-inflammatory and anti-degradative actions in osteoarthritis. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 1567. DOI:10.1038/s41598-022-05323-7 [Google Scholar]

- Que Q, Guo X, Zhan L, Chen S, Zhang Z, Ni X, et al. The GLP-1 agonist, liraglutide, ameliorates inflammation through the activation of the PKA/CREB pathway in a rat model of knee osteoarthritis. J. Inflamm. 2019, 16, 13. DOI:10.1186/s12950-019-0218-y [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Xie JJ, Shi KS, Gu YT, Wu CC, Xuan J, et al. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor regulates endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced apoptosis and the associated inflammatory response in chondrocytes and the progression of osteoarthritis in rat. Cell Death Dis. 2018, 9, 212. DOI:10.1038/s41419-017-0217-y [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Jiang J, Xu J, Chen J, Gu Y, Wu G. Liraglutide, a glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist, ameliorates inflammation and apoptosis via inhibition of receptor for advanced glycation end products signaling in AGEs induced chondrocytes. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2024, 25, 601. DOI:10.1186/s12891-024-07640-6 [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Chen J, Li B, Fang X. The protective effects of dulaglutide against advanced glycation end products (AGEs)-induced degradation of type II collagen and aggrecan in human SW1353 chondrocytes. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2020, 322, 108968. DOI:10.1016/j.cbi.2020.108968 [Google Scholar]

- Mei J, Sun J, Wu J, Zheng X. Liraglutide suppresses TNF-alpha-induced degradation of extracellular matrix in human chondrocytes: A therapeutic implication in osteoarthritis. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2019, 11, 4800–4808. [Google Scholar]