Synthetic Biology-Inspired Biocontainment Strategies of Therapeutic Genetically Engineered Bacteria

Received: 22 November 2025 Revised: 24 December 2025 Accepted: 05 January 2026 Published: 08 January 2026

© 2026 The authors. This is an open access article under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

1. Introduction

With the rapid advances of synthetic biology, the repertoire of artificially designed genetic components and genetically engineered bacteria has expanded substantially. These engineered bacteria have shown considerable promise in the diagnosis and treatment of various diseases, including gastrointestinal disorders and cancers [1,2,3,4,5,6,7]. Nevertheless, the unintentional release of such engineered constructs or microorganisms into the environment poses potential biosafety concerns [8,9,10,11,12]. A notable example is the use of antibiotic resistance genes as selectable markers in synthetic biology. Antibiotic resistance genes can be horizontally transferred to pathogenic microbes, facilitating the emergence of drug-resistant strains and complicating antimicrobial therapy [13]. Consequently, robust biosafety containment strategies are essential, particularly for engineered bacteria intended for clinical diagnostics and therapeutic applications [14,15,16].

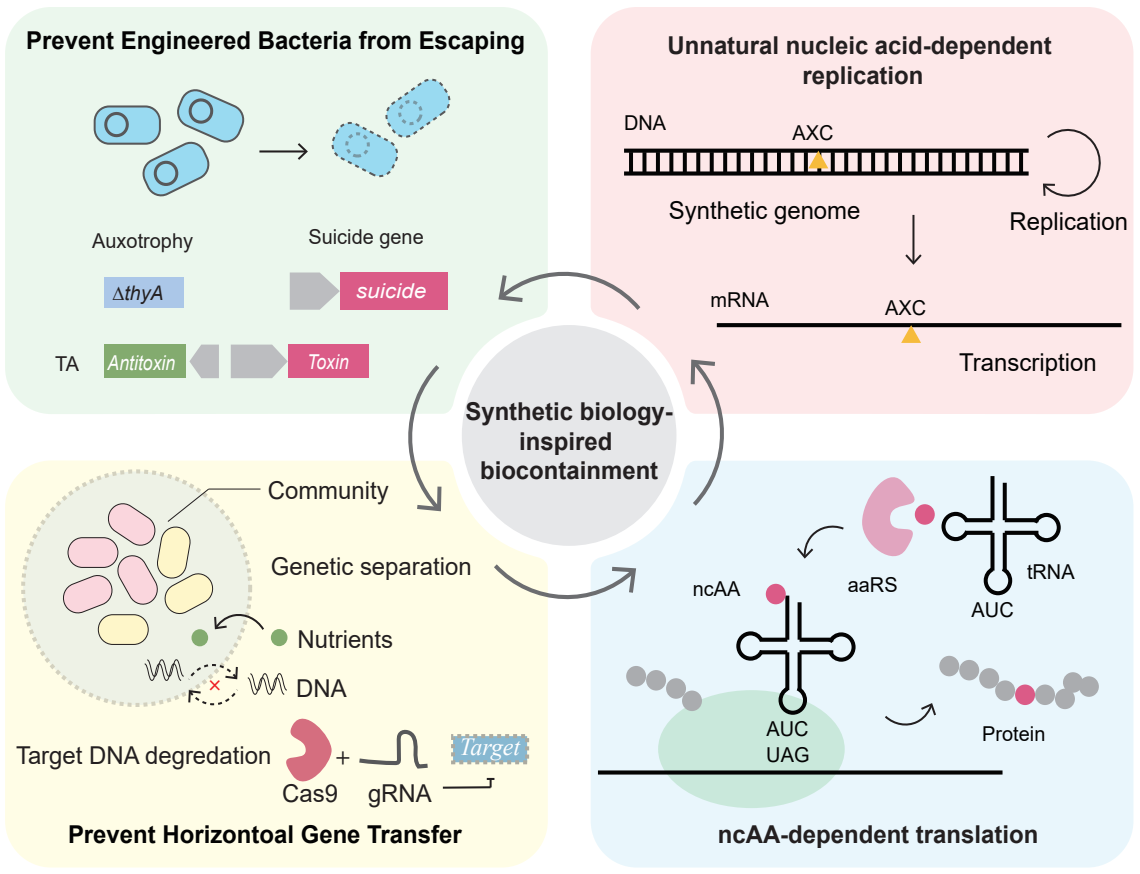

Biosafety containment in synthetic biology encompasses two principal dimensions [17]. The first is preventing the environmental dissemination of engineered bacteria, typically through mechanisms that inhibit or eradicate cells escaping from designated settings. Current guidelines from the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) recommend that the escape frequency of engineered microorganisms remain below 10−8 [18]. However, the rapid expansion in the number and diversity of engineered strains has intensified the need for even more stringent biocontainment thresholds. The second dimension involves minimizing the release of engineered genetic elements and subsequent uptake by environmental microorganisms [19,20]. Therefore, integrating biocontainment mechanisms directly into the genetic design of engineered bacteria based on synthetic biology principles has emerged as a foundational strategy to mitigate biosafety risks. This review outlines current biosafety containment strategies in synthetic biology, especially focusing on biosafety controls of genetically engineered bacteria developed for therapeutic applications. Then we discuss recent advances in orthogonal biocontainment systems, reducing the compromising risk via cross-talking with environmental microbes.

2. Preventing Genetically Engineered Bacteria from Escaping

Although most engineered bacteria have been designed based on lab model microbes, for example, Escherichia coli, and some strains are susceptible to growth conditions, the escape of the therapeutic bacteria from unintended sites could lead to adverse effects. To restrict the unintended spread of engineered bacteria, a central strategy involves controlling cellular survival by regulating the expression of essential genes or conditionally activating toxin genes. Some of these strategies are easily designed and have been well studied in the bacteria therapy.

2.1. Auxotrophy

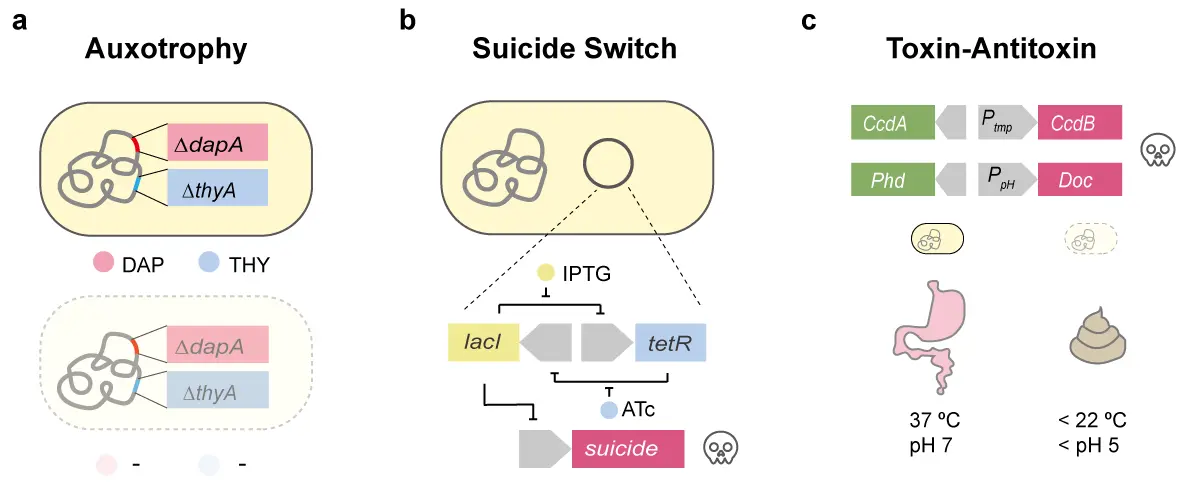

Auxotrophy-based containment relies on the targeted disruption of essential genes, rendering engineered bacteria incapable of synthesizing critical metabolites such as nucleotides or amino acids. As a result, these strains can proliferate only when the missing metabolites are externally provided. In addition to deleting biosynthetic enzymes, inactivation of the corresponding transporter proteins can likewise induce auxotrophy, thereby forcing bacteria to depend on exogenous metabolic precursors for survival [21]. Because of its conceptual simplicity and ease of implementation, auxotrophy has been widely used as a biosafety containment strategy [22,23,24,25,26,27]. However, in complex environments containing diverse nutrients, engineered bacteria may circumvent auxotrophic constraints. Within the human body, a metabolically rich environment shaped by host tissues and the gut microbiota, auxotrophic strains may acquire essential metabolites directly from surrounding cells or restore metabolic capacity through horizontal gene transfer (HGT) from coexisting microorganisms. Importantly, many auxotrophic phenotypes are reliably expressed only under nutrient-limited conditions [21], as illustrated by NADPH-auxotrophic E. coli in mineral salts medium [28]. Consequently, careful selection and context-specific design of auxotrophic strategies are essential to ensure robust biocontainment of engineered bacteria.

Auxotrophic designs intended for diagnostic or therapeutic engineered bacteria should preferentially target metabolites that are essential for prokaryotic survival but absent or scarce in mammalian systems. There are two commonly employed auxotrophy strategies (Figure 1a). Diaminopimelic acid (DAP) is a critical precursor produced by the dapA gene (4-hydroxy-tetrahydrodipicolinate synthase) in bacterial cell wall synthesis. Engineered strains lacking dapA cannot maintain proper cell wall integrity and therefore fail to survive [29,30]. DAP auxotrophy is commonly used in bacteria therapy because mammalian cells lack cell walls and do not synthesize DAP. Deoxythymidine (THY) generated via the thyA gene (thymidylate synthase) is required for dTTP biosynthesis and DNA replication. thyA-deficient strains become dependent on exogenous THY, which is present only at extremely low levels in mammalian tissues [31]. A notable example of this approach is SYNB1891, an engineered E. coli–based immunotherapeutic strain developed by Synlogic. Designed to activate antigen-presenting cells through secretion of STING agonists, SYNB1891 incorporates dual knockouts of dapA and thyA, thereby preventing its proliferation in mice [32]. The strain has progressed to Phase I clinical evaluation [33]. Although auxotrophy is validated in well-defined bacterial metabolic pathways, incomplete annotation of metabolic networks in different chassis organisms [34] raises the possibility of metabolic compensation via unknown or alternative pathways. As such, rigorous experimental validation is essential when developing novel auxotrophic containment systems.

Figure 1. Biocontainment strategies prevent genetically engineered bacteria from escaping. (a) Autotrophy by gene knockout of dapA (4-hydroxy-tetrahydrodipicolinate synthase) or thyA (thymidylate synthase) [30,31]. DAP, diaminopimelic acid. THY, deoxythymidine. (b) Suicide switch based on transcriptional regulation [35]. LacI, lactose operon repressor. TetR, tetracycline repressor. IPTG, isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside. ATc, anhydrotetracycline. (c) The toxin-antitoxin system activates toxin expression to kill engineered bacteria in response to temperature or pH [36]. CcdB and Doc are toxins. CcdA and Phd are antitoxins. Ptmp, temperature-responsive promoter. PpH, pH-responsive promoter.

2.2. Suicide Switches

Suicide gene–based regulatory switches enable the targeted elimination of engineered bacteria through inducible expression of toxic genes [37,38,39]. Compared with antibiotic-based control strategies, these systems offer notable advantages: they have no risk of disseminating antibiotic resistance genes and can achieve more rapid bacterial killing through protein-level regulatory mechanisms [40]. Such switches can be designed to activate suicide gene expression in response to defined chemical or environmental signals [41]. When stimuli such as temperature, pH, or specific metabolites are used as inducers, they enable the construction of environmentally responsive containment circuits. For example, the Deadman switch operates as a toggle system in which anhydrotetracycline (ATc) modulates the mutually repressive transcription factors TetR (tetracycline repressor) and LacI (lactose operon repressor), with LacI suppressing toxin expression (Figure 1b). Continuous ATc exposure is required to maintain bacterial viability, ATc removal initiates suicide gene activation. The system’s efficacy can be further enhanced by supplementing IPTG (isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside), which directly induces toxin expression and improves killing efficiency [35]. More sophisticated designs integrate multi-layer regulatory logic, enabling simultaneous control by multiple inducers and further reducing the escape probability. The Passcode switch employs a LacI–GalR fusion protein together with additional regulators to create a circuit controlled by three inducers, permitting survival only under a specific input combination. Despite their potential, suicide gene switches frequently exhibit basal leakage. The expression of low-level toxins, even in the absence of inducers, can impair bacterial fitness. Over time, mutants that silence or disable the switch may accumulate and outcompete functional strains, ultimately compromising containment. Reducing mutation rates in engineered bacteria therefore represents a key strategy to improve the long-term stability and reliability of suicide switch systems.

2.3. Toxin-Antitoxin Systems

Toxin–antitoxin (TA) systems provide an effective strategy to mitigate the fitness costs often associated with suicide gene–based biocontainment circuits [42,43]. TA modules consist of a toxin, typically a small fast-acting protein, and a cognate antitoxin that may be either a protein or a noncoding RNA neutralizing toxin activity [44]. By maintaining low-level antitoxin expression to counteract basal toxin leakage in the absence of induction, TA systems can alleviate the detrimental effects of background toxicity, thereby preserving the functionality and stability of suicide gene switches. Among the best-characterized TA systems is the CcdB–CcdA pair. The CcdB toxin targets DNA gyrase, inducing double-stranded DNA breaks and cell death, whereas the CcdA antitoxin neutralizes CcdB through direct binding. In one application, a temperature-sensitive promoter governs expression of the CcdB–CcdA module in engineered strains designed for intestinal disease treatment. At the physiological temperature of 37 °C, CcdB expression is repressed to permit bacterial growth [45]. Upon excretion, exposure to ambient temperatures below 22 °C induces CcdB activation and triggers rapid bacterial killing (Figure 1c). The biocontainment robustness can be further enhanced by integrating multiple orthogonal TA modules. For example, combining the CcdB–CcdA system with the pH-responsive Doc–Phd pair has been shown to reduce escape frequencies to as low as 10−11 [36]. Doc toxin inhibits translation by phosphorylating the elongation factor EF-Tu, thereby preventing its interaction with tRNA, while the Phd antitoxin counteracts this effect. Reliable operation of TA-based biocontainment requires tightly regulated expression to maintain a precise balance between toxin and antitoxin expression levels. Perturbations in this balance may compromise biocontainment performance. Accordingly, the application of quantitative synthetic biology principles to TA circuit design offers a promising route to improving regulatory precision and long-term stability.

3. Limiting Horizontal Gene Transfer from Genetically Engineered Bacteria

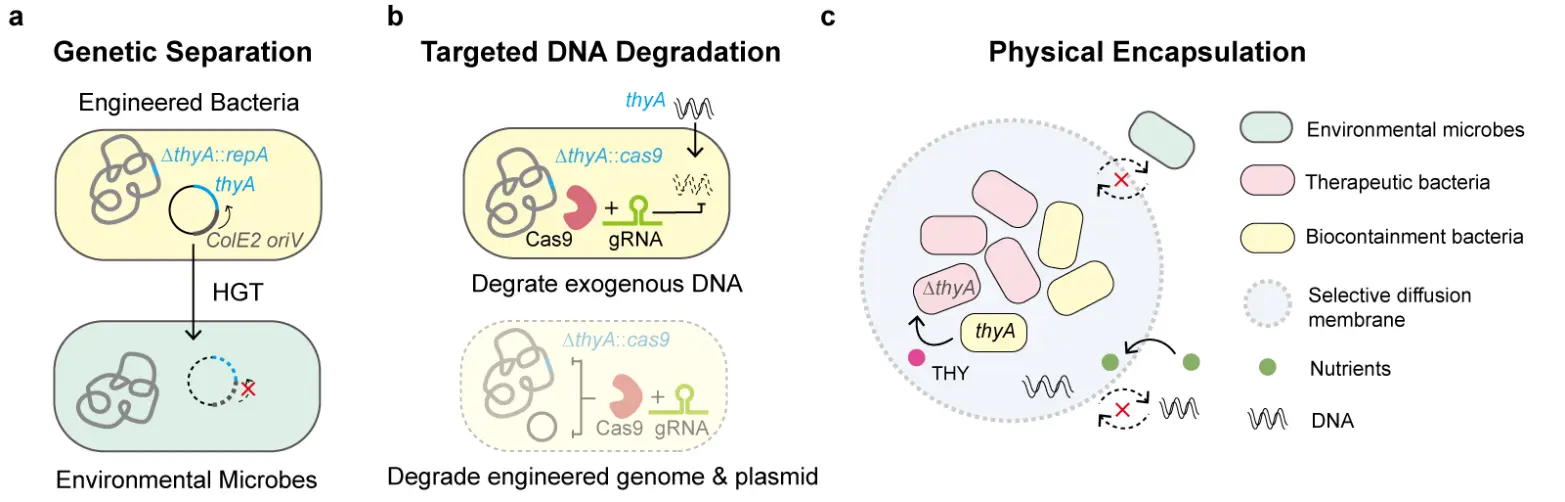

Engineered bacteria can exchange genetic material with environmental microorganisms through HGT [46]. Such transfer events may disseminate engineered genetic elements, including antibiotic resistance genes, into natural microbial communities, potentially altering their composition and functional characteristics. Preventing and monitoring the dissemination of genetic components from engineered bacteria to environmental microorganisms remains a significant challenge. To reduce the risk of horizontal gene transfer, several strategies have been developed that employ genetic separation, target gene degradation, or physical encapsulation to limit the exposure of engineered genetic material to surrounding microbial communities.

3.1. Genetic Separation

Genetic separation is routinely applied in viral vector packaging, wherein the viral genome is partitioned to divide the structural and replication genes into distinct vectors, allowing viral assembly only when all components are present [47]. In contrast, segmenting the bacterial genome remains technically challenging since bacterial genomes are several orders of magnitude larger than viral genomes. Current strategies largely focus on partitioning specific genetic elements or selected genes within the genome to establish mutual dependency among the engineered components.

Geneguard is a plasmid-engineered bacterial mutual dependency system (Figure 2a) designed to prevent horizontal transfer of plasmids to environmental microorganisms [48]. In this system, the thyA gene is deleted from the engineered bacterial genome, while the plasmid carries a functional thyA to complement this deletion. Concurrently, the plasmid replication initiation gene repA, essential for the ColE2 plasmid origin of replication, is removed from the plasmid and integrated into the host chromosome. As a result, plasmid replication is confined to the engineered host, since any plasmid transferred to environmental microbes cannot replicate in the absence of repA. Although Geneguard provides effective biocontainment in E. coli, its applicability to other bacterial species requires further validation.

Engineered bacteria often harbor complex genetic constructs, which can impose substantial metabolic burdens and reduce genetic stability, potentially leading to the loss of functional or biocontainment elements. Distributing these functional and biocontainment components across multiple host strains to form bacterial consortia [49,50,51] can mitigate metabolic load on individual strains and enhance the stability of genetic elements [52,53]. To further improve biosafety, strains within the community can be engineered as auxotrophic mutants that rely on metabolite exchange. This interdependence ensures that, even if one strain escapes into the environment, it cannot replicate autonomously. Community design also enables strategic selection of chassis organisms according to functional requirements. For example, biocontainment elements can be incorporated into hosts with low mutation rates, whereas therapeutic genes can be expressed in auxotrophic hosts optimized for high production. This division of labor enhances both the functional performance and biosafety stability of therapeutic bacterial communities [54,55,56,57]. Bacterial population dynamics can be further regulated through quorum-sensing (QS) circuits, which enable coordinated behaviors at the community level [58]. For instance, the PluxI promoter can control antibiotic resistance gene expression in response to the autoinducer AHL. At high AHL concentrations, resistance is induced to maintain population density, whereas at low AHL levels, resistance is suppressed, leading to substantial bacterial death [59].

Figure 2. Biocontainment strategies mitigating horizontal gene transfer from genetically engineered bacteria. (a) Essential gene thyA or plasmid replication initiator repA is separately placed in a plasmid or the genome to prevent engineered plasmid horizontal gene transfer (HGT) from host bacteria to environmental microbes [48]. ColE2 oriV, ColE2 replication origin. (b) With the specificity of gene editing, CRISPR associated nuclease Cas9/gRNA (guide RNA) degrades exogenous DNA or engineered genome for biocontainment [60]. (c) Encapsulation of engineered bacteria provides physical barrier to insulate and protect therapeutic microbes [61]. Solid arrows indicate allowable transfer, while dashed arrows indicate unallowable transfer.

3.2. DNA Degradation

DNA degradation serves a dual function in biocontainment by inducing lethal double-strand breaks in the bacterial genome and selectively degrading plasmids to limit environmental dissemination of engineered genes. Clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)-based biocontainment systems have been widely adapted for this purpose. Biosafety platforms employing Cas (CRISPR-associated protein) nucleases such as Cas3 [62], Cas9 [63,64,65,66], and Cas12 [67,68] have achieved escape frequencies below 10−8. For instance, a tetracycline and temperature regulated Cas9 switch can target the bacterial genome for cleavage, resulting in the complete clearance of engineered bacteria from the mouse gastrointestinal tract (Figure 2b). Auxotrophic strains are at risk of acquiring missing essential genes from environmental microbes, leading to compromising biocontainment. To preserve the reliability of the auxotrophic safeguard, a thyA-targeting Cas9 system was introduced into a thyA-knockout auxotrophic strain, ensuring that any incoming exogenous thyA sequences are rapidly degraded [60]. Nevertheless, HGT may introduce alternative genes that bypass the auxotrophic dependency, and sequence variation in homologous genes (e.g., thyA) across environmental bacteria presents an additional challenge. Incorporating multiple guide RNAs (gRNAs) to target a broader range of potential exogenous sequences can mitigate this limitation and enhance the robustness of the containment system.

In addition to Cas proteins, other nucleases have been employed to achieve DNA degradation for biosafety purposes. Recently, Foo et al. engineered a temperature-sensitive intein-DNA endonuclease fusion protein to control the biocontainment of bacteria used in intestinal disease therapies [69]. In this system, the intein remains inactive at 37 °C, and its insertion disrupts proper folding of the endonuclease, allowing the engineered bacteria to survive and perform their therapeutic function within the mouse host. Upon excretion, exposure to lower ambient temperatures triggers intein splicing, restoring endonuclease activity, and promoting bacterial death. Notably, because this endonuclease lacks sequence specificity, it is unsuitable for applications requiring targeted gene degradation.

3.3. Phisical Encapsulation

Physical encapsulation is a key strategy for enhancing the biosafety of engineered bacteria. This approach employs polymeric materials, such as hydrogels, to insulate bacterial cells, establishing a stable physical barrier between the engineered organisms and the external environment (Figure 2c). The semi-permeable membranes formed by these polymers permit the selective diffusion of small molecules, such as nutrients, while restricting the passage of larger biomolecules (e.g., DNA) and bacteria. This confinement not only retains the engineered bacteria and their genetic elements within the material but also mitigates interference from environmental factors, including host immune responses, competing microorganisms, pH fluctuations, and ionic conditions [61,70,71]. Physical encapsulation holds significant promise for medical applications of diagnostic and therapeutic bacteria. Encapsulated bacteria can be localized at specific body sites to detect disease biomarkers or signaling molecules and perform site-specific diagnostic or therapeutic functions. For example, Gelatin methacrylate (GelMA)-based noncontact microbiota transplantation system (NMTS) microcapsules have been used to encapsulate engineered bacteria, protecting them from gastric acidity and bile salts in the gastrointestinal tract. This strategy prevents bacterial leakage and associated infections while preserving their anti-pathogenic activity [72]. Similarly, bacteria encapsulated in alginate and subsequently coated with biocompatible layers of hyaluronic acid (HA) and epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) demonstrated enhanced intestinal colonization and sustained heme-responsive therapeutic protein secretion for monitoring and treating inflammatory bowel disease [73]. Encapsulation also facilitates integration of engineered bacteria with electronic components in personalized diagnostic devices. For instance, a microelectronic capsule containing engineered bacteria can be deployed in the gastrointestinal tract, where bacterial production of fluorescent proteins in response to inflammatory molecules is converted by integrated electronics into electrical signals, enabling real-time monitoring of intestinal inflammation [74]. Despite these advances, clinical translation of encapsulation strategies requires further validation of material stability and biocompatibility. Maintaining long-term bacterial viability and functionality, particularly for chronic disease applications, remains a major challenge. Furthermore, implantation of relatively large devices may require surgical procedures, imposing additional burdens on patients. The development of advanced biocompatible materials is expected to minimize immune rejection and inflammatory advert effects, facilitating broader clinical application.

4. Enhance the Orthogonality of Biocontainment Systems

A critical challenge in the development of biocontainment strategies is the potential failure of containment systems due to the horizontal acquisition of genetic fragments, spontaneous mutations, or the uptake of environmental metabolites. Enhancing the orthogonality of these systems is therefore essential to prevent functional interference between engineered bacteria and environmental microorganisms via metabolite exchange or genetic transfer.

4.1. Unnatural Nucleic Acids

The natural genetic code is composed of four canonical nucleotides, A, G, C, and T (or U in RNA), which encode and transmit genetic information via replication and transcription. Recently, non-canonical nucleotides have been developed to expand the genetic code and have been applied to biocontainment. For example, in thyA-knockout E. coli, which requires exogenous THY for dTTP synthesis and genome replication, gradual substitution of THY with 5-chlorouracil (Cl-U) in the medium leads to the evolution of a strain that depends exclusively on Cl-U for DNA replication. In this engineered auxotroph, approximately 90% of thymine residues in the genome were replaced by Cl-U. Because Cl-U is not naturally metabolized and must be supplied externally, this dependency provides a robust biocontainment strategy [75].

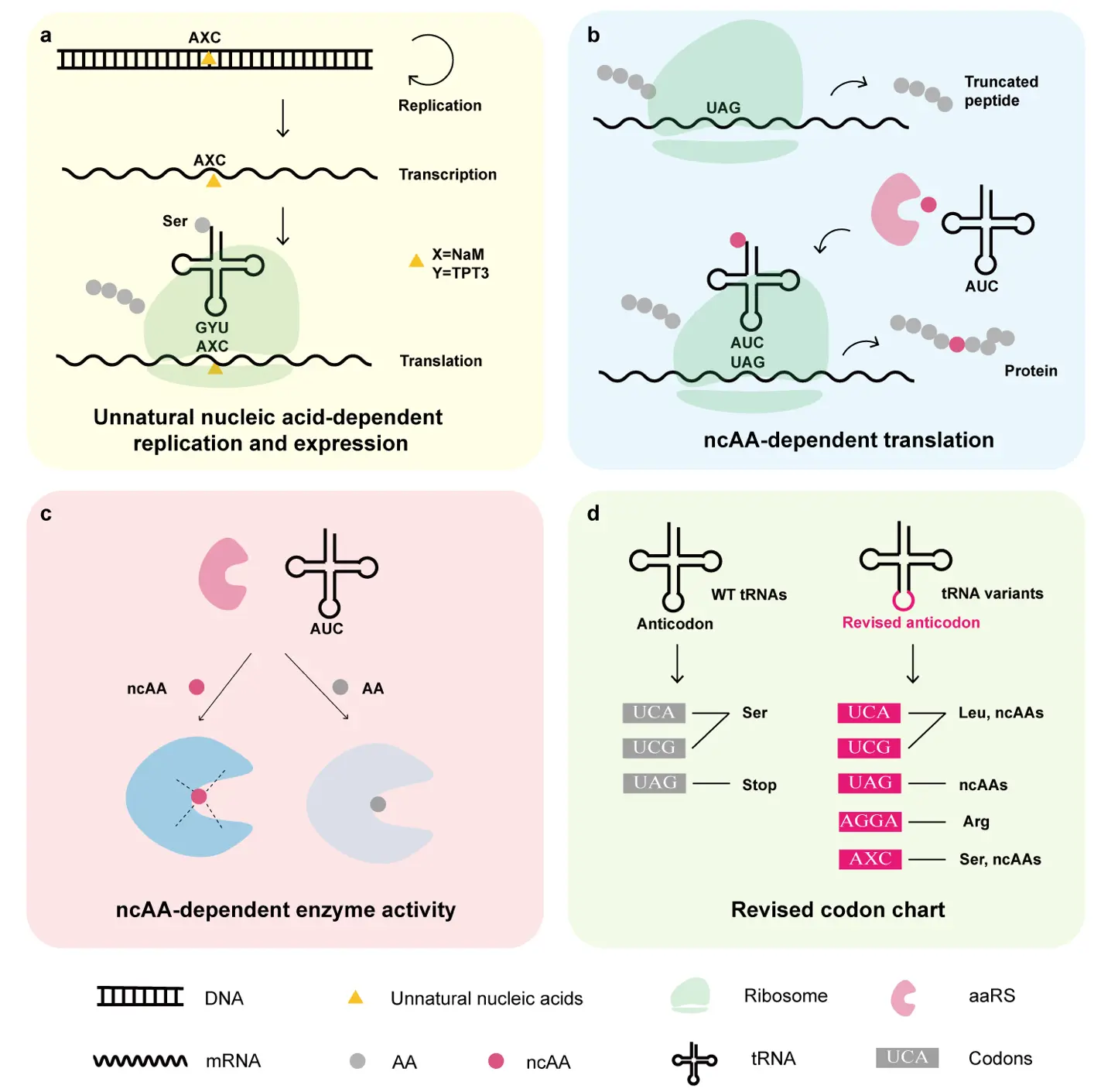

Natural nucleotides form base pairs through complementary hydrogen bonding, whereas unnatural nucleotides can utilize alternative pairing mechanisms. For example, the dNaM-dTPT3 pair interacts via hydrophobic forces. When plasmids containing dNaM–dTPT3 are introduced into E. coli, these unnatural nucleotides can be faithfully replicated in daughter plasmids [76] (Figure 3a). Because dNaM and dTPT3 cannot cross the bacterial membrane passively, the host E. coli must be engineered to genomically integrate the PtNTT2 transporter gene for active importing of these nucleotides. As a result, plasmids harboring dNaM-dTPT3 cannot replicate in wild-type bacteria lacking this specific transporter, providing an effective biocontainment mechanism. Plasmids containing dNaM-dTPT3 can also be transcribed into RNA, and ribosomes are capable of interpreting codons containing these unnatural nucleotides. For instance, incorporation of a mutant serT gene produces a tRNASer with a TPT3-containing anticodon (GYU, where Y = TPT3), which decodes the unnatural codon AXC (X = NaM) as serine [77]. However, both the number and positional context of unnatural nucleotides within codons influence their orthogonality. Not all sequences support correct codon-anticodon pairing. Several orthogonal codon-anticodon pairs, including AXC–GYU, GXC–GYC, and AGX–XCU, have been identified for use in protein translation. Additional unnatural base pairs, such as 5SICS–NaM, TPT3–CNMO, and TAT1–5FM, have also been developed to expand the genetic repertoire.

Figure 3. Synthetic replication, transcription, and translation systems enhance the orthogonality of the biocontainment strategy. (a) Unnatural nucleic acids are employed by DNA replication and RNA transcription [77]. (b) Noncanonical amino acids (ncAA) regulate essential gene translation by reading through the premature stop codons [78]. (c) The unique chemical structures of ncAAs confer an additional layer of biocontainment by modulating enzyme activity. (d) Genome-wide engineering reconstructs the codon chart and reduces cross-talking with environmental microbes [79]. AA, canonical amino acids. ncAA, noncanonical amino acids. aaRS, aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase.

4.2. Noncanonical Amino Acids

Proteins composed of 20 canonical amino acids are direct executors of biological functions. To expand amino acid diversity, multiple methods have been developed to incorporate structurally unique noncanonical amino acids (ncAAs) into proteins [78]. Among these, genetic code expansion enables the site-specific insertion of ncAAs into proteins in living cells using orthogonal tRNA/aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase (aaRS) pairs [80]. The orthogonal aaRS catalyzes the formation of ncAA-tRNA, which then pairs via its anticodon to a designated codon, typically a premature stop codon such as TAG in the mRNA, resulting in the incorporation of the ncAA at a specific site in the protein [81] (Figure 3b). This technology has been adapted to create synthetically engineered auxotrophic strains [82]. In bacteria equipped with an orthogonal tRNA/aaRS pair, introducing a premature stop codon into an essential gene prevents the synthesis of the full-length essential protein, leading to bacterial death [83,84]. Viability is restored only when the corresponding ncAA is supplied externally. Unlike conventional auxotrophy, which relies on gene knockout, these synthetic auxotrophies exhibit significantly lower escape frequencies, as ncAAs are generally unavailable in natural environments. Further reduction in escape rates can be achieved by incorporating premature stop codons into multiple essential genes simultaneously. This approach has been applied to various engineered bacteria, including the therapeutic strain E. coli Nissle 1917 [85,86]. In one study, systematic screening of 155 premature stop codons introduced into 22 essential genes of E. coli identified that simultaneously targeting murG, dnaA, and serS reduces the bacterial escape rate to below 10−11 [87].

Orthogonal tRNA/aaRS pairs do not exhibit absolute specificity for noncanonical amino acid incorporation. In the absence of the designated ncAA, the orthogonal synthetase may mischarge a structurally similar canonical amino acid at the target codon. Even low-level misincorporation can generate trace amounts of essential proteins, potentially compromising biocontainment. To overcome this limitation, protein structure prediction and directed evolution have been employed to engineer enzymes whose activity depends exclusively on the unique chemical structure of the ncAA, thereby preventing escape via incorporation of canonical amino acids (Figure 3c) [88,89]. For example, L-4,4′-biphenylalanine (bipA) has a substantially larger aromatic side chain than any natural amino acid. Incorporation of bipA into an enzyme active site, combined with complementary mutations in surrounding residues, renders enzymatic activity strictly dependent on bipA. Substitution with any natural amino acid abolishes the enzyme function [90]. Introducing bipA dependency into multiple essential proteins in E. coli has reduced the escape frequency to 10−12. In another approach, chorismate mutase (CM), a homodimeric enzyme in aromatic amino acid biosynthesis stabilized by a Tyr72-mediated salt bridge, was redesigned by replacing Tyr72 with a TAG codon. Using the orthogonal tRNA/aaRS system to incorporate benzoyl-L-phenylalanine (pBzF) at this site enables dimerization via π–π stacking of pBzF side chains, making bacterial viability strictly dependent on exogenous pBzF for active CM formation [91]. Similarly, the essential gene manA, encoding mannose-6-phosphate isomerase, requires His264 for zinc binding and catalytic activity. By remodeling the active site through mutagenesis and incorporating 3-methylhistidine (MeH) at the His264TAG position via the orthogonal system, ManA activity becomes dependent on MeH rather than histidine for zinc coordination and enzymatic function [92].

Engineered tRNA modifications in combination with synthetic genomics enable the reassignment of codon-amino acid relationships [79] (Figure 3d). For example, the fully recoded E. coli strain Syn61 was constructed with a genome containing only 61 codons. The serine codons TCA and TCG, along with the stop codon TAG, were liberated from their canonical assignments and reassigned to various ncAA [93]. Consequently, plasmids harboring these reassigned codons cannot produce functional proteins in environmental microorganisms that lack the corresponding orthogonal tRNA/aaRS pairs, limiting the horizontal transfer of bioactive genes. In another study, the anticodons of tRNALeu were mutated to generate tRNALeuUGA and tRNALeuCGA, which recognize the TCA and TCG codons, respectively. Introduction of these engineered tRNAs into Syn61 effectively reassigned these serine codons to leucine [94]. Further expansion of the genetic code has been achieved through tRNAs with quadruplet anticodons, enabling decoding of four-base codons. For instance, the native tRNAArgCCU was redesigned as tRNAArgUCCU. Essential genes, such as the replication initiation factor TrfA, were modified to include an AGGA quadruplet codon, making bacterial viability strictly dependent on tRNAArgUCCU, thereby providing a dual safeguard against both bacterial escape and functional gene transfer [95]. The integration of unnatural nucleotide-based replication systems with ncAA incorporation further enables translation at codons containing synthetic bases. In one example, the codon AXC (X = NaM) is introduced into a target gene, and an engineered E. coli strain equipped with an orthogonal tRNA/aaRS pair decodes it by a tRNA with the anticodon GYT (Y = TPT3), then inserts a ncAA at the specified site [77]. Collectively, these codon reassignment strategies not only reduce bacterial escape rates but also restrict the functional transfer of genetic material to natural microorganisms.

4.3. Synthetic Genome

Genetic mutations in engineered bacteria can compromise the functionality of synthetic biology components within biocontainment systems. Engineering of DNA replication, recombination, and repair can reduce mutation rates, thereby maintaining the integrity of the biocontainment system. For example, continuous culture of E. coli harboring a suicide gene switch for four days led to insertion mutations within the suicide gene. Deletion of the genomic insertion sequence elements SI1 and SI5 effectively suppressed these mutations, decreasing the escape frequency of the engineered bacteria by over three orders of magnitude [35].

Increasing the copy number of target genes can mitigate the functional consequences of mutations in synthetic biological components. Sequencing of escaped engineered bacteria has revealed mutations in genetic switches as a primary cause of biocontainment failure. Introducing multiple copies of regulatory genes reduces the likelihood of complete inactivation, as the probability that all copies of a multi-copy gene are simultaneously mutated is substantially lower than for a single-copy gene [96]. Moreover, integration of target genes into the host genome provides greater genetic stability than plasmid-based expression. Engineered bacteria with synthetically streamlined genomes may further reduce mutational uncertainty. Genome minimization achieved by removing non-essential genes enhances control over metabolic pathways and creates capacity for additional synthetic components. For instance, while the native genome of Mycoplasma mycoides spans 1079 kb, the synthesized JVCI-syn3.0 strain has a reduced genome of 531 kb [97]. Similarly, pangenome analysis of E. coli identified 243 essential genes out of 867, highlighting substantial potential for genomic reduction [98].

5. Conclusions and Perspective

The expanding application of synthetic biology has intensified biosafety concerns. Although rapidly advancing biocontainment strategies can effectively limit the dissemination and replication of engineered bacteria and genetic elements in the environment (Table 1), several challenges remain. Auxotrophic designs targeting specific essential genes are widely employed in therapeutic bacteria. Strategies incorporating ncAA or unnatural nucleic acids further reduce the risk of cross-feeding by environmental metabolites. However, the orthogonality of such systems requires improvement. Metabolomic profiling can inform the distribution and availability of metabolites in diverse environments, guiding the selection of feasible auxotrophic designs. Additionally, expanding the repertoire of tRNA/aaRS pairs from diverse species, coupled with protein structure prediction, is expected to yield orthogonal pairs with enhanced specificity. Environmentally responsive suicide gene switches can restrict bacterial escape, and toxin-antitoxin systems mitigate the fitness costs associated with basal expression of toxic genes. Nevertheless, the introduction of complex regulatory circuits imposes metabolic burdens. Advances in quantitative synthetic biology and artificial intelligence now enable rational design of sophisticated gene circuits and metabolic pathways, optimizing the expression of both functional and biocontainment genes [99]. Genetic separation allows the construction of host–plasmid mutual dependency systems or the distribution of functions across microbial communities, reducing HGT between engineered and environmental bacteria. To date, most biocontainment systems have been validated only in laboratory model strains. Future efforts should expand to include diverse host species, such as naturally occurring strains, to facilitate complex community-level behaviors. Genetic mutations in biocontainment elements remain a major cause of escape. Engineering DNA replication and repair pathways can reduce mutation rates, while a deeper understanding of genome function can inform the design of minimized, synthetic genomes with predictable genetic backgrounds. Cell-free systems offer a radical solution by eliminating the risk of bacterial escape entirely. Looking ahead, integrated multi-layered containment strategies represent a critical research frontier. For instance, combining orthogonal replication and translation machinery could establish fully synthetic systems based on engineered DNA, RNA, proteins, and metabolites, substantially reducing the leakage of viable bacteria or functional genetic elements. When coupled with physical containment approaches, such as polymer-based encapsulation [100,101,102], these strategies have the potential to enable safer and more effective diagnostic and therapeutic bacterial products. Finally, it is challenging to track the escaping events of genetically engineered bacteria or genetic components in a complex environment, particularly when the escaping rate of the biocontainment system is low. Next-generation sequencing is promising for detecting escaping events if the escaped DNA or RNA can be distinguished from unescaped microorganisms using specific barcoding technologies [103,104,105].

Table 1. Summary of different biocontainment strategies.

|

Biocontainment Strategies |

Summarizing |

|---|---|

|

Auxotrophy |

Most commonly used. Simple and easy to implement. Cross-talking with environmental metabolites. |

|

Suicide switch |

Rapid bacterial clearance. Without the risk of antibiotic resistance gene. Toxin leakage impairs fitness. |

|

Toxin-Antitoxin system |

Alleviate background toxicity. |

|

Genetic separation |

Reduce bacterial escaping and horizontal gene transfer. Further engineering on host genomes. |

|

DNA degradation |

Target DNA cleavage for biosafety control. |

|

Physical encapsulation |

Physical isolation of engineered bacteria and genetic components. Need further investigation for biocompatibility. |

|

Unnatural nucleic acids |

Orthogonal replication-transcription system. The number and context influence the orthogonality. |

|

Noncanonical amino acids |

An orthogonal translational system to reduce the escaping rate. |

|

Synthetic genome |

Synthetic genome to minimize genetic components and cross-talking. Need large-scale genome engineering. |

Statement of the Use of Generative AI and AI-Assisted Technologies in the Writing Process

During the preparation of this manuscript, the author(s) used ChatGPT (OpenAI GPT-4.1, 2025) in order to polish language. After using this tool/service, the author(s) reviewed and edited the content as needed and take(s) full responsibility for the content of the published article.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jingrui Zuo and Youzhi Cao from Soochow University for helpful suggestions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.G.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, M.G. and C.C.; Writing—Review & Editing, C.C. and M.G.

Ethics Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No data was used for the research described in the article.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

-

Gurbatri CR, Arpaia N, Danino T. Engineering bacteria as interactive cancer therapies. Science 2022, 378, 858–864. DOI:10.1126/science.add9667 [Google Scholar]

-

Kim K, Kang M, Cho BK. Systems and synthetic biology-driven engineering of live bacterial therapeutics. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2023, 11, 1267378. DOI:10.3389/fbioe.2023.1267378 [Google Scholar]

-

Raman V, Deshpande CP, Khanduja S, Howell LM, Van Dessel N, Forbes NS. Build-a-bug workshop: Using microbial-host interactions and synthetic biology tools to create cancer therapies. Cell Host Microbe 2023, 31, 1574–1592. DOI:10.1016/j.chom.2023.09.006 [Google Scholar]

-

Ciocan D, Elinav E. Engineering bacteria to modulate host metabolism. Acta Physiol. 2023, 238, e14001. DOI:10.1111/apha.14001 [Google Scholar]

-

Zhai L, Fu L, Wei W, Zheng D. Advances of Bacterial Biomaterials for Disease Therapy. ACS Synth. Biol. 2024, 13, 1400–1411. DOI:10.1021/acssynbio.4c00022 [Google Scholar]

-

Yan S, Gan Y, Xu H, Piao H. Bacterial carrier-mediated drug delivery systems: A promising strategy in cancer therapy. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2024, 12, 1526612. DOI:10.3389/fbioe.2024.1526612 [Google Scholar]

-

Dey S, Sankaran S. Engineered bacterial therapeutics with material solutions. Trends Biotechnol. 2024, 42, 1663–1676. DOI:10.1016/j.tibtech.2024.06.011 [Google Scholar]

-

Lee JW, Chan CTY, Slomovic S, Collins JJ. Next-generation biocontainment systems for engineered organisms. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2018, 14, 530–537. DOI:10.1038/s41589-018-0056-x [Google Scholar]

-

Asin-Garcia E, Kallergi A, Landeweerd L, Martins dos Santos VAP. Genetic Safeguards for Safety-by-design: So Close Yet So Far. Trends Biotechnol. 2020, 38, 1308–1312. DOI:10.1016/j.tibtech.2020.04.005 [Google Scholar]

-

Parker MT, Kunjapur AM. Deployment of Engineered Microbes: Contributions to the Bioeconomy and Considerations for Biosecurity. Health Secur. 2020, 18, 278–296. DOI:10.1089/hs.2020.0010 [Google Scholar]

-

Arnolds KL, Dahlin LR, Ding L, Wu C, Yu J, Xiong W, et al. Biotechnology for secure biocontainment designs in an emerging bioeconomy. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2021, 71, 25–31. DOI:10.1016/j.copbio.2021.05.004 [Google Scholar]

-

Ou Y, Guo S. Safety risks and ethical governance of biomedical applications of synthetic biology. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2023, 11, 1292029. DOI:10.3389/fbioe.2023.1292029 [Google Scholar]

-

Halawa EM, Fadel M, Al-Rabia MW, Behairy A, Nouh NA, Abdo M, et al. Antibiotic action and resistance: Updated review of mechanisms, spread, influencing factors, and alternative approaches for combating resistance. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 14, 1305294. DOI:10.3389/fphar.2023.1305294 [Google Scholar]

-

Angles AP, Valle-Pérez AU, Hauser C, Mahfouz MM. Microbial Biocontainment Systems for Clinical, Agricultural, and Industrial Applications. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 830200. DOI:10.3389/fbioe.2022.830200 [Google Scholar]

-

Huang Y, Lin X, Yu S, Chen R, Chen W. Intestinal Engineered Probiotics as Living Therapeutics: Chassis Selection, Colonization Enhancement, Gene Circuit Design, and Biocontainment. ACS Synth. Biol. 2022, 11, 3134–3153. DOI:10.1021/acssynbio.2c00314 [Google Scholar]

-

Arboleda-García A, Alarcon-Ruiz I, Boada-Acosta L, Boada Y, Vignoni A, Jantus-Lewintre E. Advancements in synthetic biology-based bacterial cancer therapy: A modular design approach. Crit. Rev. Oncol./Hematol. 2023, 190, 104088. DOI:10.1016/j.critrevonc.2023.104088 [Google Scholar]

-

Moe-Behrens GHG, Davis R, Haynes KA. Preparing synthetic biology for the world. Front. Microbiol. 2013, 4, 5. DOI:10.3389/fmicb.2013.00005 [Google Scholar]

-

Wilson DJ. NIH guidelines for research involving recombinant DNA molecules. Acc. Res. 1993, 3, 177–185. DOI:10.1080/08989629308573848 [Google Scholar]

-

Feng G, Huang H, Chen Y. Effects of emerging pollutants on the occurrence and transfer of antibiotic resistance genes: A review. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 420, 126602. DOI:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2021.126602 [Google Scholar]

-

Wang S, Li W, Xi B, Cao L, Huang C. Mechanisms and influencing factors of horizontal gene transfer in composting system: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 955, 177017. DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.177017 [Google Scholar]

-

Hirota R, Abe K, Katsuura Z-I, Noguchi R, Moribe S, Motomura K, et al. A Novel Biocontainment Strategy Makes Bacterial Growth and Survival Dependent on Phosphite. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 44748. DOI:10.1038/srep44748 [Google Scholar]

-

Agmon N, Tang Z, Yang K, Sutter B, Ikushima S, Cai Y, et al. Low escape-rate genome safeguards with minimal molecular perturbation of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, E1470–E1479. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1621250114 [Google Scholar]

-

Asin-Garcia E, Batianis C, Li Y, Fawcett JD, de Jong I, dos Santos VAPM. Phosphite synthetic auxotrophy as an effective biocontainment strategy for the industrial chassis Pseudomonas putida. Microb. Cell Factories 2022, 21, 156. DOI:10.1186/s12934-022-01883-5 [Google Scholar]

-

Sebesta J, Xiong W, Guarnieri MT, Yu J. Biocontainment of Genetically Engineered Algae. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 839446. DOI:10.3389/fpls.2022.839446 [Google Scholar]

-

Bongaerts N, Edoo Z, Abukar AA, Song X, Sosa-Carrillo S, Haggenmueller S, et al. Low-cost anti-mycobacterial drug discovery using engineered E. coli. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 3905. DOI:10.1038/s41467-022-31570-3 [Google Scholar]

-

Hedin KA, Kruse V, Vazquez-Uribe R, Sommer MOA. Biocontainment strategies for in vivo applications of Saccharomyces boulardii. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2023, 11, 1136095. DOI:10.3389/fbioe.2023.1136095 [Google Scholar]

-

Rueda-Mejia MP, Bühlmann A, Ortiz-Merino RA, Lutz S, Ahrens CH, Künzler M, et al. Pantothenate Auxotrophy in a Naturally Occurring Biocontrol Yeast. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2023, 89, e00884. DOI:10.1128/aem.00884-23 [Google Scholar]

-

Lindner SN, Ramirez LC, Krüsemann JL, Yishai O, Belkhelfa S, He H, et al. NADPH-Auxotrophic E. coli: A Sensor Strain for Testing In Vivo Regeneration of NADPH. ACS Synth. Biol. 2018, 7, 2742–2749. DOI:10.1021/acssynbio.8b00313 [Google Scholar]

-

Isabella VM, Ha BN, Castillo MJ, Lubkowicz DJ, Rowe SE, Millet YA, et al. Development of a synthetic live bacterial therapeutic for the human metabolic disease phenylketonuria. Nat. Biotechnol. 2018, 36, 857–864. DOI:10.1038/nbt.4222 [Google Scholar]

-

Nelson MT, Charbonneau MR, Coia HG, Castillo MJ, Holt C, Greenwood ES, et al. Characterization of an engineered live bacterial therapeutic for the treatment of phenylketonuria in a human gut-on-a-chip. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 2805. DOI:10.1038/s41467-021-23072-5 [Google Scholar]

-

Kurtz CB, Millet YA, Puurunen MK, Perreault M, Charbonneau MR, Isabella VM, et al. An engineered E. coli Nissle improves hyperammonemia and survival in mice and shows dose-dependent exposure in healthy humans. Sci. Transl. Med. 2019, 11, eaau7975. DOI:10.1126/scitranslmed.aau7975 [Google Scholar]

-

Leventhal DS, Sokolovska A, Li N, Plescia C, Kolodziej SA, Gallant CW, et al. Immunotherapy with engineered bacteria by targeting the STING pathway for anti-tumor immunity. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 2739. DOI:10.1038/s41467-020-16602-0 [Google Scholar]

-

Luke JJ, Piha-Paul SA, Medina T, Verschraegen CF, Varterasian M, Brennan AM, et al. Phase I Study of SYNB1891, an Engineered E. coli Nissle Strain Expressing STING Agonist, with and without Atezolizumab in Advanced Malignancies. Clin. Cancer Res. Off. J. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. 2023, 29, 2435. DOI:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-23-0118 [Google Scholar]

-

Ata Ö, Mattanovich D. Into the metabolic wild: Unveiling hidden pathways of microbial metabolism. Microb. Biotechnol. 2024, 17, e14548. DOI:10.1111/1751-7915.14548 [Google Scholar]

-

Chan CTY, Lee JW, Cameron DE, Bashor CJ, Collins JJ. “Deadman” and “Passcode” microbial kill switches for bacterial containment. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2015, 12, 82. DOI:10.1038/nchembio.1979 [Google Scholar]

-

Stirling F, Naydich A, Bramante J, Barocio R, Certo M, Wellington H, et al. Synthetic Cassettes for pH-Mediated Sensing, Counting, and Containment. Cell Rep. 2020, 30, 3139–3148.e4. DOI:10.1016/j.celrep.2020.02.033 [Google Scholar]

-

Jones BS, Lamb LS, Goldman F, Stasi AD. Improving the safety of cell therapy products by suicide gene transfer. Front. Pharmacol. 2014, 5, 254. DOI:10.3389/fphar.2014.00254 [Google Scholar]

-

Čelešnik H, Tanšek A, Tahirović A, Vižintin A, Mustar J, Vidmar V, et al. Biosafety of biotechnologically important microalgae: Intrinsic suicide switch implementation in cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Biol. Open 2016, 5, 519. DOI:10.1242/bio.017129 [Google Scholar]

-

Zhou Y, Sun T, Chen Z, Song X, Chen L, Zhang W. Development of a New Biocontainment Strategy in Model Cyanobacterium Synechococcus Strains. ACS Synth. Biol. 2019, 8, 2576–2584. DOI:10.1021/acssynbio.9b00282 [Google Scholar]

-

Hoffmann SA, Cai Y. Engineering stringent genetic biocontainment of yeast with a protein stability switch. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1060. DOI:10.1038/s41467-024-44988-8 [Google Scholar]

-

Varma S, Gulati KA, Sriramakrishnan J, Ganla RK, Raval R. Environment signal dependent biocontainment systems for engineered organisms: Leveraging triggered responses and combinatorial systems. Synth. Syst. Biotechnol. 2024, 10, 356. DOI:10.1016/j.synbio.2024.12.005 [Google Scholar]

-

Mu Z, Zou Z, Yang Y, Wang W, Xu Y, Huang J, et al. A genetically engineered Escherichia coli that senses and degrades tetracycline antibiotic residue. Synth. Syst. Biotechnol. 2018, 3, 196. DOI:10.1016/j.synbio.2018.05.001 [Google Scholar]

-

Halvorsen TM, Ricci DP, Park DM, Jiao Y, Yung MC. Comparison of Kill Switch Toxins in Plant-Beneficial Pseudomonas fluorescens Reveals Drivers of Lethality, Stability, and Escape. ACS Synth. Biol. 2022, 11, 3785–3796. DOI:10.1021/acssynbio.2c00386 [Google Scholar]

-

Jurėnas D, Fraikin N, Goormaghtigh F, Van Melderen L. Biology and evolution of bacterial toxin–antitoxin systems. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2022, 20, 335–350. DOI:10.1038/s41579-021-00661-1 [Google Scholar]

-

Ferry QRV, Lyutova R, Fulga TA. Rational design of inducible CRISPR guide RNAs for de novo assembly of transcriptional programs. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 14633. DOI:10.1038/ncomms14633 [Google Scholar]

-

Soucy SM, Huang J, Gogarten JP. Horizontal gene transfer: Building the web of life. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2015, 16, 472–482. DOI:10.1038/nrg3962 [Google Scholar]

-

Wolff JH, Mikkelsen JG. Delivering genes with human immunodeficiency virus-derived vehicles: Still state-of-the-art after 25 years. J. Biomed. Sci. 2022, 29, 79. DOI:10.1186/s12929-022-00865-4 [Google Scholar]

-

Wright O, Delmans M, Stan G-B, Ellis T. GeneGuard: A Modular Plasmid System Designed for Biosafety. ACS Synth. Biol. 2015, 4, 307–316. DOI:10.1021/sb500234s [Google Scholar]

-

Eng A, Borenstein E. Microbial Community Design:Methods, Applications, and Opportunities. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2019, 58, 117. DOI:10.1016/j.copbio.2019.03.002 [Google Scholar]

-

Ibrahim M, Raajaraam L, Raman K. Modelling microbial communities: Harnessing consortia for biotechnological applications. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2021, 19, 3892–3907. DOI:10.1016/j.csbj.2021.06.048 [Google Scholar]

-

Forti AM, Jones MA, Elbeyli DN, Butler ND, Kunjapur AM. Engineered orthogonal and obligate bacterial commensalism mediated by a non-standard amino acid. Nat. Microbiol. 2025, 10, 1404–1416. DOI:10.1038/s41564-025-01999-5 [Google Scholar]

-

Mimee M, Citorik RJ, Lu TK. Microbiome Therapeutics—Advances and Challenges. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2016, 105, 44. DOI:10.1016/j.addr.2016.04.032 [Google Scholar]

-

Ke J, Wang B, Yoshikuni Y. Microbiome Engineering: Synthetic Biology of Plant-Associated Microbiomes in Sustainable Agriculture. Trends Biotechnol. 2021, 39, 244–261. DOI:10.1016/j.tibtech.2020.07.008 [Google Scholar]

-

Rapp KM, Jenkins JP, Betenbaugh MJ. Partners for life: Building microbial consortia for the future. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2020, 66, 292–300. DOI:10.1016/j.copbio.2020.10.001 [Google Scholar]

-

Ozdemir T, Fedorec AJH, Danino T, Barnes CP. Synthetic Biology and Engineered Live Biotherapeutics: Toward Increasing System Complexity. Cell Syst. 2018, 7, 5–16. DOI:10.1016/j.cels.2018.06.008 [Google Scholar]

-

Dou J, Bennett MR. Synthetic biology and the gut microbiome. Biotechnol. J. 2017, 13, e1700159. DOI:10.1002/biot.201700159 [Google Scholar]

-

Nevot G, Santos-Moreno J, Campamà-Sanz N, Toloza L, Parra-Cid C, Jansen PAM, et al. Synthetically programmed antioxidant delivery by a domesticated skin commensal. Cell Syst. 2025, 14, 101169. DOI:10.1016/j.cels.2025.101169 [Google Scholar]

-

VanArsdale E, Navid A, Chu MJ, Halvorsen TM, Payne GF, Jiao Y, et al. Electrogenetic signaling and information propagation for controlling microbial consortia via programmed lysis. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2023, 120, 1366–1381. DOI:10.1002/bit.28337 [Google Scholar]

-

Huang S, Lee AJ, Tsoi R, Wu F, Zhang Y, Leong KW, et al. Coupling spatial segregation with synthetic circuits to control bacterial survival. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2016, 12, 859. DOI:10.15252/msb.20156567 [Google Scholar]

-

Hayashi N, Lai Y, Fuerte-Stone J, Mimee M, Lu TK. Cas9-assisted biological containment of a genetically engineered human commensal bacterium and genetic elements. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 2096. DOI:10.1038/s41467-024-45893-w [Google Scholar]

-

Che H, Wang Z, Li Y, Nie Y, Tian X. A Stable and Sensitive Engineering Bacterial Sensor via Physical Biocontainment and Two-Stage Signal Amplification. Anal. Chem. 2024, 96, 8807–8813. DOI:10.1021/acs.analchem.4c01341 [Google Scholar]

-

Caliando BJ, Voigt CA. Targeted DNA degradation using a CRISPR device stably carried in the host genome. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 6989. DOI:10.1038/ncomms7989 [Google Scholar]

-

Rottinghaus AG, Ferreiro A, Fishbein SRS, Dantas G, Moon TS. Genetically stable CRISPR-based kill switches for engineered microbes. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 672. DOI:10.1038/s41467-022-28163-5 [Google Scholar]

-

Asin-Garcia E, Martin-Pascual M, Garcia-Morales L, van Kranenburg R, Martins dos Santos VAP. ReScribe: An Unrestrained Tool Combining Multiplex Recombineering and Minimal-PAM ScCas9 for Genome Recoding Pseudomonas putida. ACS Synth. Biol. 2021, 10, 2672. DOI:10.1021/acssynbio.1c00297 [Google Scholar]

-

Hartig AM, Dai W, Zhang K, Kapoor K, Rottinghaus AG, Moon TS, et al. Influence of Environmental Conditions on the Escape Rates of Biocontained Genetically Engineered Microbes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 22657–22667. DOI:10.1021/acs.est.4c10893 [Google Scholar]

-

Asin-Garcia E, Martin-Pascual M, de Buck C, Allewijn M, Müller A, Martins dos Santos VAP. GenoMine: A CRISPR-Cas9-based kill switch for biocontainment of Pseudomonas putida. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2024, 12, 1426107. DOI:10.3389/fbioe.2024.1426107 [Google Scholar]

-

Pantoja Angles A, Ali Z, Mahfouz M. CS-Cells: A CRISPR-Cas12 DNA Device to Generate Chromosome-Shredded Cells for Efficient and Safe Molecular Biomanufacturing. ACS Synth. Biol. 2022, 11, 430–440. DOI:10.1021/acssynbio.1c00516 [Google Scholar]

-

Yang B, Wu C, Teng Y, Chou KJ, Guarnieri MT, Xiong W. Tailoring microbial fitness through computational steering and CRISPRi-driven robustness regulation. Cell Syst. 2024, 15, 1133–1147.e4. DOI:10.1016/j.cels.2024.11.012 [Google Scholar]

-

Foo GW, Leichthammer CD, Saita IM, Lukas ND, Batko IZ, Heinrichs DE, et al. Intein-based thermoregulated meganucleases for containment of genetic material. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, 2066. DOI:10.1093/nar/gkad1247 [Google Scholar]

-

Tang T-C, Tham E, Liu X, Yehl K, Rovner AJ, Yuk H, et al. Hydrogel-Based Biocontainment of Bacteria for Continuous Sensing and Computation. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2021, 17, 724. DOI:10.1038/s41589-021-00779-6 [Google Scholar]

-

Datta D, Weiss EL, Wangpraseurt D, Hild E, Chen S, Golden JW, et al. Phenotypically complex living materials containing engineered cyanobacteria. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 4742. DOI:10.1038/s41467-023-40265-2 [Google Scholar]

-

Wu F, Lin S, Luo H, Wang C, Liu J, Zhu X, et al. Noncontact microbiota transplantation by core-shell microgel-enabled nonleakage envelopment. Sci. Adv. 2025, 11, eadr7373. DOI:10.1126/sciadv.adr7373 [Google Scholar]

-

Zou Z-P, Cai Z, Zhang X-P, Zhang D, Xu C-Y, Zhou Y, et al. Delivery of Encapsulated Intelligent Engineered Probiotic for Inflammatory Bowel Disease Therapy. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2025, 14, 2403704. DOI:10.1002/adhm.202403704 [Google Scholar]

-

Inda-Webb ME, Jimenez M, Liu Q, Phan NV, Ahn J, Steiger C, et al. Sub-1.4 cm3 capsule for detecting labile inflammatory biomarkers in situ. Nature 2023, 620, 386–392. DOI:10.1038/s41586-023-06369-x [Google Scholar]

-

Marlière P, Patrouix J, Döring V, Herdewijn P, Tricot S, Cruveiller S, et al. Chemical Evolution of a Bacterium’s Genome. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 7109–7114. DOI:10.1002/anie.201100535 [Google Scholar]

-

Malyshev DA, Dhami K, Lavergne T, Chen T, Dai N, Foster JM, et al. A semi-synthetic organism with an expanded genetic alphabet. Nature 2014, 509, 385–388. DOI:10.1038/nature13314 [Google Scholar]

-

Zhang Y, Ptacin JL, Fischer EC, Aerni HR, Caffaro CE, San Jose K, et al. A semi-synthetic organism that stores and retrieves increased genetic information. Nature 2017, 551, 644–647. DOI:10.1038/nature24659 [Google Scholar]

-

Mukai T, Lajoie MJ, Englert M, Söll D. Rewriting the Genetic Code. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2017, 71, 557–577. DOI:10.1146/annurev-micro-090816-093247 [Google Scholar]

-

Lajoie MJ, Rovner AJ, Goodman DB, Aerni H-R, Haimovich AD, Kuznetsov G, et al. Genomically recoded organisms expand biological functions. Science 2013, 342, 357–360. DOI:10.1126/science.1241459 [Google Scholar]

-

Wang L, Brock A, Herberich B, Schultz PG. Expanding the Genetic Code of Escherichia coli. Science 2001, 292, 498–500. DOI:10.1126/science.1060077 [Google Scholar]

-

Kato Y. Translational Control using an Expanded Genetic Code. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 887. DOI:10.3390/ijms20040887 [Google Scholar]

-

Chang T, Ding W, Yan S, Wang Y, Zhang H, Zhang Y, et al. A robust yeast biocontainment system with two-layered regulation switch dependent on unnatural amino acid. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 6487. DOI:10.1038/s41467-023-42358-4 [Google Scholar]

-

Kato Y. An engineered bacterium auxotrophic for an unnatural amino acid: A novel biological containment system. PeerJ 2015, 3, e1247. DOI:10.7717/peerj.1247 [Google Scholar]

-

Kato Y. Extremely Low Leakage Expression Systems Using Dual Transcriptional-Translational Control for Toxic Protein Production. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 705. DOI:10.3390/ijms21030705 [Google Scholar]

-

Kuru E, Määttälä R-M, Noguera K, Stork DA, Narasimhan K, Rittichier J, et al. Release Factor Inhibiting Antimicrobial Peptides Improve Nonstandard Amino Acid Incorporation in Wild-type Bacterial Cells. ACS Chem. Biol. 2020, 15, 1852–1861. DOI:10.1021/acschembio.0c00055 [Google Scholar]

-

Gao X, Sun Y, Yang Y, Yang X, Liu Q, Guo X, et al. Directed evolution of hydroxylase XcP4H for enhanced 5-HTP production in engineered probiotics to treat depression. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 307, 142250. DOI:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2025.142250 [Google Scholar]

-

Rovner AJ, Haimovich AD, Katz SR, Li Z, Grome MW, Gassaway BM, et al. Recoded organisms engineered to depend on synthetic amino acids. Nature 2015, 518, 89–93. DOI:10.1038/nature14095 [Google Scholar]

-

Xuan W, Schultz PG. A Strategy for Creating Organisms Dependent on Noncanonical Amino Acids. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 9170–9173. DOI:10.1002/anie.201703553 [Google Scholar]

-

Tack DS, Ellefson JW, Thyer R, Wang B, Gollihar J, Forster MT, et al. Addicting diverse bacteria to a noncanonical amino acid. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2016, 12, 138–140. DOI:10.1038/nchembio.2002 [Google Scholar]

-

Mandell DJ, Lajoie MJ, Mee MT, Takeuchi R, Kuznetsov G, Norville JE, et al. Biocontainment of genetically modified organisms by synthetic protein design. Nature 2015, 518, 55–60. DOI:10.1038/nature14121 [Google Scholar]

-

Koh M, Nasertorabi F, Han GW, Stevens RC, Schultz PG. Generation of an Orthogonal Protein-Protein Interface with a Noncanonical Amino Acid. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 5728–5731. DOI:10.1021/jacs.7b02273 [Google Scholar]

-

Gan F, Liu R, Wang F, Schultz PG. Functional Replacement of Histidine in Proteins To Generate Noncanonical Amino Acid Dependent Organisms. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 3829–3832. DOI:10.1021/jacs.7b13452 [Google Scholar]

-

Fredens J, Wang K, de la Torre D, Funke LFH, Robertson WE, Christova Y, et al. Total synthesis of Escherichia coli with a recoded genome. Nature 2019, 569, 514. DOI:10.1038/s41586-019-1192-5 [Google Scholar]

-

Nyerges A, Vinke S, Flynn R, Owen SV, Rand EA, Budnik B, et al. A swapped genetic code prevents viral infections and gene transfer. Nature 2023, 615, 720–727. DOI:10.1038/s41586-023-05824-z [Google Scholar]

-

Choi Y-N, Kim D, Lee S, Shin YR, Lee JW. Quadruplet codon decoding-based versatile genetic biocontainment system. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, gkae1292. DOI:10.1093/nar/gkae1292 [Google Scholar]

-

Cai Y, Agmon N, Choi WJ, Ubide A, Stracquadanio G, Caravelli K, et al. Intrinsic biocontainment: Multiplex genome safeguards combine transcriptional and recombinational control of essential yeast genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 1803–1808. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1424704112 [Google Scholar]

-

Callaway E. ‘Minimal’ cell raises stakes in race to harness synthetic life. Nature 2016, 531, 557–558. DOI:10.1038/531557a [Google Scholar]

-

Yang Z-K, Luo H, Zhang Y, Wang B, Gao F. Pan-genomic analysis provides novel insights into the association of E. coli with human host and its minimal genome. Bioinformatics 2019, 35, 1987–1991. DOI:10.1093/bioinformatics/bty938 [Google Scholar]

-

Lawson CE, Martí JM, Radivojevic T, Jonnalagadda SVR, Gentz R, Hillson NJ, et al. Machine learning for metabolic engineering: A review. Metab. Eng. 2021, 63, 34–60. DOI:10.1016/j.ymben.2020.10.005 [Google Scholar]

-

Dianawati D, Mishra V, Shah NP. Survival of Microencapsulated Probiotic Bacteria after Processing and during Storage: A Review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2016, 56, 1685–1716. DOI:10.1080/10408398.2013.798779 [Google Scholar]

-

Nguyen T-T, Nguyen P-T, Pham M-N, Razafindralambo H, Hoang Q-K, Nguyen H-T. Synbiotics: A New Route of Self-production and Applications to Human and Animal Health. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2022, 14, 980–993. DOI:10.1007/s12602-022-09960-2 [Google Scholar]

-

Hassanisaadi M, Vatankhah M, Kennedy JF, Rabiei A, Saberi Riseh R. Advancements in xanthan gum: A macromolecule for encapsulating plant probiotic bacteria with enhanced properties. Carbohydr. Polym. 2025, 348, 122801. DOI:10.1016/j.carbpol.2024.122801 [Google Scholar]

-

de Lorenzo V, Krasnogor N, Schmidt M. For the sake of the Bioeconomy: Define what a Synthetic Biology Chassis is! New Biotechnol. 2021, 60, 44–51. DOI:10.1016/j.nbt.2020.08.004 [Google Scholar]

-

Wang F, Zhang W. Synthetic biology: Recent progress, biosafety and biosecurity concerns, and possible solutions. J. Biosaf. Biosecur. 2019, 1, 22–30. DOI:10.1016/j.jobb.2018.12.003 [Google Scholar]

-

Kalvapalle PB, Staubus A, Dysart MJ, Gambill L, Reyes Gamas K, Lu LC, et al. Information storage across a microbial community using universal RNA barcoding. Nat. Biotechnol. 2025, 1–8. DOI:10.1038/s41587-025-02593-0 [Google Scholar]