Porous Framework Materials for C1 Biotransformation

Received: 30 November 2025 Revised: 19 December 2025 Accepted: 24 December 2025 Published: 29 December 2025

© 2025 The authors. This is an open access article under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

1. Introduction

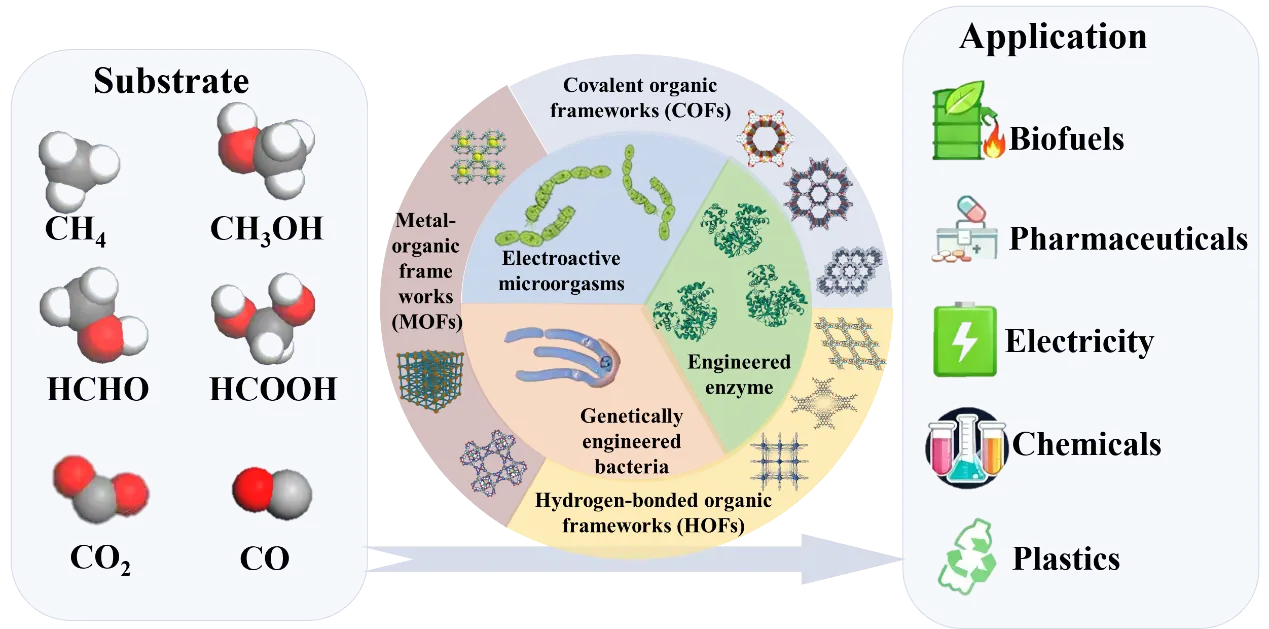

In response to the escalating challenges of global climate change and environmental degradation, sustainable development has emerged as a pivotal focus of global research and innovation [1,2]. Within this context, biomanufacturing presents a sustainable pathway for producing fuels and chemicals [3]. Unlike first-generation biorefining, which relies on food crops, or second-generation processes that utilize lignocellulosic biomass, third-generation biorefining leverages C1 building blocks [4], such as CO2, CO, methane, methanol, and formic acid, in conjunction with clean energy sources like solar and electrical power [5]. These abundant, low-cost C1 represent promising carbon feedstocks for advanced bio-manufacturing [6].

The rapid advancement of synthetic biology has positioned the biological utilization of C1 compounds as a pivotal area of contemporary research [7]. Current approaches for C1 bioconversion primarily rely on two pathways: enzymatic catalysis and whole-cell microbial catalysis [8]. Key enzymes involved, such as formate dehydrogenase (FDH), carbonic anhydrase (CA), and CO dehydrogenase, are renowned for their mild reaction conditions, exceptional regioselectivity, and chemoselectivity compared to synthetic catalysts [9]. Furthermore, a diverse range of native microorganisms, including microalgae, photosynthetic bacteria, acetogens, methanotrophs, and Pichia pastoris, possess a natural capacity to assimilate C1 compounds and convert them into higher-value fuels and chemicals like formic acid, methane, and methanol [1]. However, the efficiency of these biological systems is significantly hampered by several formidable challenges, including the low aqueous solubility of gaseous substrates, the inherent instability of enzymes, the dependency on costly cofactors, low microbial conversion rates, and unsatisfactory selectivity toward multi-carbon products. Addressing these limitations is thus critical for advancing the field [2].

Porous framework materials, including metal-organic frameworks (MOFs), covalent organic frameworks (COFs), and hydrogen-bonded organic frameworks (HOFs), possess exceptional properties [10] such as high porosity, large specific surface area, tunable pore structures, and customizable functionality [11]. These attributes make them highly promising for applications in biotransformation. The immobilization of enzymes or microbial cells within these frameworks can significantly enhance their stability and catalytic efficiency. Furthermore, the frameworks can adsorb and concentrate C1 substrates. Some of these materials also exhibit intrinsic catalytic, optical, or electronic properties [12]. The integration of framework materials with biocatalysis thus enables simultaneous C1 capture and conversion. When combined with photo- or electro-catalytic techniques, this synergy can further elevate carbon conversion efficiency while preserving the mild conditions, high efficiency, and superior product selectivity inherent to biological systems, positioning this integrated approach as a leading research frontier in C1 utilization.

This review provides a comprehensive overview of recent advances in applying porous framework materials to C1 biotransformation (Figure 1). It systematically examines their multifunctional roles that extend beyond serving as mere immobilization carriers for enzymes and microbial cells. These include: (i) enhancing local substrate concentration and mass transfer efficiency; (ii) enabling photocatalytic and electrocatalytic energy conversion for in-situ cofactor regeneration; (iii) regulating microbial metabolic pathways to optimize carbon flux; and (iv) serving as artificial enzyme mimics for biomimetic catalysis. Furthermore, the review delves into the prevailing challenges and future opportunities, aiming to offer valuable insights for developing highly efficient and integrated C1 biotransformation systems.

Figure 1. Integrated system for C1 biotransformation combining porous framework materials and biocatalysts.

2. Porous Framework Materials: Tailored Architectures for C1 Bioconversion

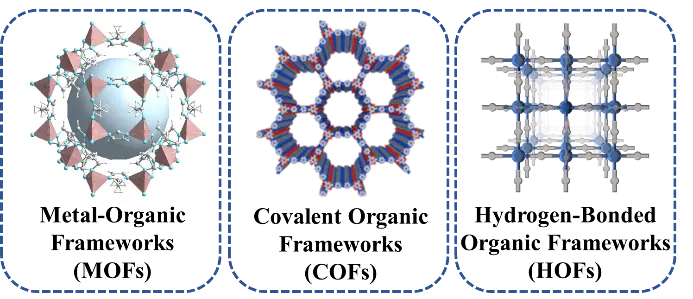

Porous crystalline frameworks [13] (Figure 2), including Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) [14,15], Covalent Organic Frameworks (COFs) [16], Hydrogen-Bonded Organic Frameworks (HOFs) [17], represent a class of advanced materials engineered from molecular building blocks via coordination [18,19], covalent [20], or hydrogen bonds [21,22].

While their fundamental characteristics (high specific surface area [23], tunable porosity [24], and modular design [20]) are well-established, it is the precise integration of these attributes that unlocks their transformative potential in C1 biotransformation [25]. Beyond serving as generic high-surface-area supports [26], their significance lies in the ability to create customized microenvironments that directly address the core challenges of C1 biocatalysis [27]. Their designability allows for: (1) pore engineering to match enzyme dimensions and facilitate substrate/product diffusion; (2) incorporation of functional sites for substrate enrichment (e.g., CO2 adsorption) [28]; and (3) integration of photo/electro-active components for energy input. This strategic functionalization moves their role from passive carriers to active participants in the conversion process.

Therefore, porous materials are key enabling components for achieving efficient, stable, and economical C1 bioconversion processes [29]. By integrating multiple functions, including immobilization, substrate enrichment, electron transfer, and multi-step catalysis, they provide a robust technological platform for converting greenhouse gases into high-value fuels and chemicals. As such, porous materials constitute a critical foundation for advancing the industrialization of biomanufacturing and carbon recycling [30].

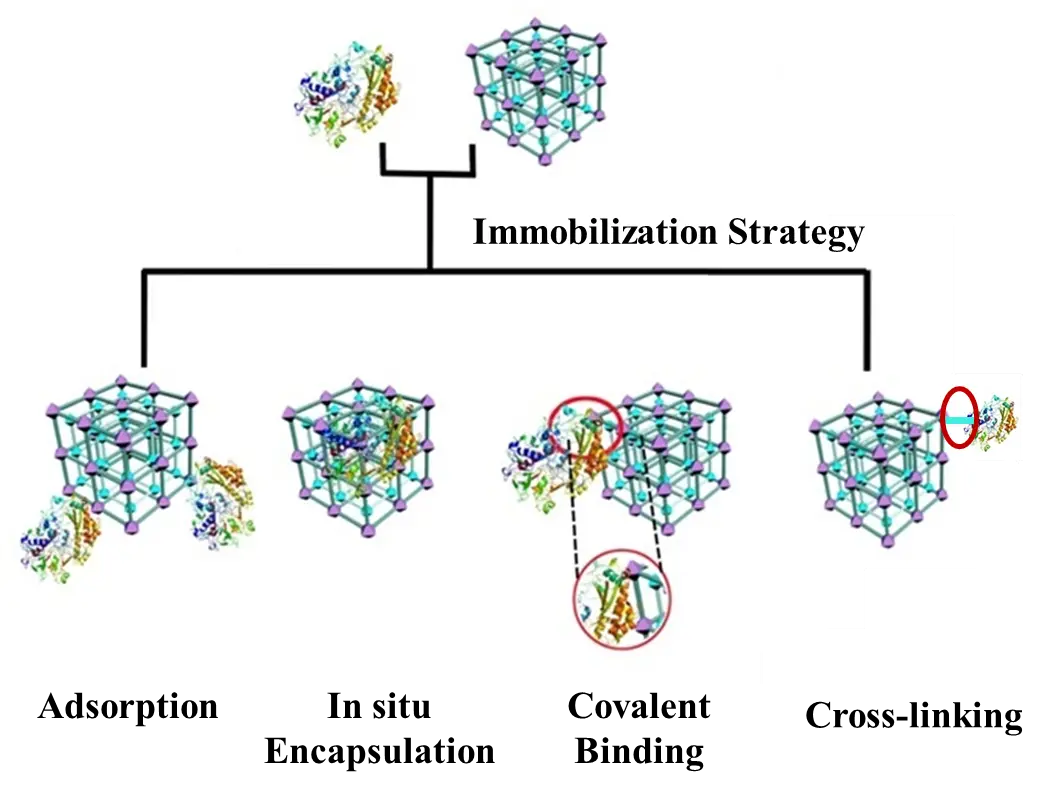

3. Strategies and Synergistic Mechanisms for Constructing Biocatalysts

Enzymes, as biological catalysts, are renowned for their high efficiency, specificity, and ability to operate under mild conditions. However, their practical application is often limited by a high susceptibility to deactivation under harsh conditions such as extreme pH, organic solvents, and elevated temperatures [31]. Furthermore, industrial-scale use of enzymes faces additional hurdles, including complex purification processes, high costs, and inadequate stability for repeated use [32]. To address these limitations, enzyme immobilization techniques have been developed (Figure 3) [33]. This approach involves immobilizing enzymes to solid supports via physical or chemical methods, which enhances their stability, facilitates recovery and reuse, and can even improve catalytic performance, thereby significantly expanding their practical utility [33,34].

3.1. Enzyme Immobilization Strategies

3.1.1. In-Situ Encapsulation

The in-situ synthesis method involves the incorporation of enzymes into the growing lattice of framework materials during their synthesis [35]. This approach typically results in higher enzyme loading capacity, more uniform enzyme distribution, and stronger enzyme-carrier interactions [36]. Consequently, it significantly enhances enzyme stability and can create a protective microenvironment that optimizes catalytic performance [37]. Zhang et al. [38] co-immobilized four enzymes, formate dehydrogenase (PaFDH), formaldehyde dehydrogenase (BmFADH), glycolaldehyde synthase (PpGALS), and alcohol dehydrogenase (GoADH), using a hydrogen-bonded organic framework (HOF) under mild aqueous conditions. By leveraging its large pore size, hydrogen bonding, and π–π stacking interactions, the HOF achieved a high co-immobilization loading (0.99 g/g) while preserving enzyme activity and mass transfer efficiency. When integrated into an electrocatalytic system, this platform directly converted CO2 to ethylene glycol (EG), yielding 0.15 mM of EG in 6 h with an average conversion rate of 7.15 × 10−7 mmol CO2 min−1·mg−1 enzyme.

3.1.2. Adsorption

This approach falls under adsorption methods, which rely on non-covalent interactions such as hydrogen bonding, electrostatic attraction, and hydrophobic interactions, or on confining enzyme molecules within the pores of a carrier material for immobilization. The key advantages of this method include simple operation, mild conditions, and well-preserved enzyme activity [39]. However, its main limitations lie in the weak interactions between the enzyme and the carrier, which may lead to enzyme leakage during reaction and thus compromise operational stability. Additionally, when enzymes are immobilized within narrow pores, the diffusion of substrates and products might be restricted, potentially reducing the reaction rate [40]. Shi et al. [41] prepared a Filler-CA@Lys-HOF-1 (FCLH) catalyst by chemically adsorbing CA onto a filler surface, followed by coating with Lys-HOF-1. The FCLH catalyst demonstrated excellent acid tolerance and salinity resistance, maintaining approximately 80.2% of its activity after 9 h of operation in simulated seawater. After 10 reaction cycles, the catalyst retained 85.4% of its initial catalytic activity. This study holds significant implications for carbon dioxide capture and conversion on offshore platforms.

3.1.3. Covalent Binding and Cross-Linking

Both the covalent binding method [42] and the cross-linking method [43] involve forming strong chemical bonds with enzyme molecules. While they significantly enhance the stability and anti-desorption performance of the immobilized enzymes, they also share common drawbacks. Covalent binding relies on direct reactions between amino acid residues on the enzyme surface and functional groups on the carrier material, whereas cross-linking utilizes cross-linkers to connect multiple enzyme molecules or enzymes with the framework material. The primary disadvantage of both methods lies in their chemical modification processes, which can alter the enzyme’s native conformation and active site, potentially leading to significant activity loss or reduction. Furthermore, these methods generally involve complex procedures, and the cross-linking process, in particular, is difficult to control precisely [44].

3.2. Substrate Enrichment and Mass Transfer Enhancement

By immobilizing enzymes within framework materials, their recyclability and stability are enhanced, thereby improving their industrial properties. These functional materials feature editable structures and offer capabilities such as substrate enrichment.

Jiang et al. [45] converted microporous UiO-66-NH2 MOF into a hierarchical porous structure (denoted as HP-UiO-66-NH2) containing both micropores and mesopores. This hierarchical porosity facilitated enhanced CO2 enrichment and the immobilization of FDH. Notably, when integrated with an electrocatalytic NADH regeneration system, the catalytic system achieved a formate production of 1.826 mM within 3 h to 5.57 times higher than the free enzyme system, yielding a generation rate of 6086.7 µmol·gcat−1·h−1. Moreover, the activity of FDH in the CO2 to formate cascade reaction is positively influenced by the concentration of its substrate, HCO3− [46]. In a study by Razmjou et al. [47], CA and FDH were co-immobilized on a PDA/PEI-modified ZIF-8 to leverage this cascade for CO2 reduction.

This strategy proved effective, as the ZIF-8 carrier not only immobilized the enzymes but also may have contributed to CO2 hydration, as the imidazole groups in ZIF-8 can react with CO2 to form bicarbonate [46]. The immobilization platform significantly elevated the local HCO3− concentration, resulting in a 73% enhancement in formate yield. Building upon the immobilization of single enzymes, the application of MOFs has been extended to constructing complex bio-hybrid systems with whole microorganisms, such as microalgae, for enhanced photosynthetic CO2 fixation. These systems leverage the synergistic interplay between the tunable properties of MOFs and the innate metabolic machinery of the cells. One prominent strategy involves using MOFs as extracellular CO2 concentrators. For instance, Li et al. [48] assembled NH2-MIL-101(Fe) on Chlorella pyrenoidosa, where the MOF worked in concert with CA to hydrate CO2 into HCO3−. This process augmented the algae’s native CO2-concentrating mechanism (CCM), significantly boosting Rubisco expression and photosynthetic efficiency. Similarly, Hung et al. [49] engineered a hydrophilic Zn/Fe-MOF that was homogeneously dispersed in a Chlamydomonas culture. Its hierarchical pores and metal sites enhanced CO2 enrichment and delivery, working with surface-localized CA to elevate substrate availability for RuBisCo and achieve a high CO2 fixation efficiency of 21.6%. Beyond CO2 delivery, MOFs also address critical byproduct inhibition in integrated systems. In a study by Huang et al. [45], an integrated microbial fuel cell (MFC) and photobioreactor (PBR) system faced inhibited algal growth due to oxygen accumulation from photosynthesis. To counter this, a sulfide-treated cobalt-based MOF was synthesized as an efficient oxygen reduction reaction (ORR) catalyst. Its 3D porous structure facilitated electron transport, successfully scavenging dissolved oxygen. This application not only enhanced the MFC’s power density by 59.5% but also improved the algal CO2 fixation rate to a maximum of 20.7%, showcasing MOFs’ versatility in stabilizing complex bio-hybrid systems.

HOFs have also emerged as promising platforms for enzyme immobilization. A notable example is the work by Zhang et al. [50], who constructed a multi-enzyme cascade for converting CO2 to dihydroxyacetone (DHA). This cascade, termed the FFFP pathway, comprises FDH, formaldehyde dehydrogenase (FaldDH), formolase (FLS), and phosphite dehydrogenase (PTDH), and was co-encapsulated within HOF-101. The spatial confinement of these enzymes in close proximity led to an elevated local concentration of intermediates and improved mass transfer efficiency. As a result, the FFFP@HOF-101 system yielded a 1.8-fold increase in DHA production compared to the free enzyme cascade. The large specific surface area and rich porosity of HOFs provide abundant binding sites for enzymes and facilitate the diffusion and adsorption of CO2 molecules. This is particularly beneficial for enzymes like CA, which are prone to deactivation in seawater. Embedding CA within HOFs not only enhances its stability and activity but also bolsters CO2 capture capacity, thereby improving the overall catalytic conversion efficiency.

3.3. Energy Conversion and Cofactor Regeneration

The utility of porous framework materials extends beyond high surface area to their easily tunable functionality. This property is vital for bioconversion processes of C1 compounds that depend on redox enzymes (e.g., FDH) and expensive cofactors like NADH and NADPH, which provide essential hydride ions and electrons. Given that the oxidized cofactors inhibit the reaction and are costly to replenish, their regeneration is paramount for a cost-effective and efficient process [51]. Mere single-enzyme immobilization improves stability and reusability but fails to solve the cofactor consumption problem. A combined strategy of co-immobilizing enzymes with a regeneration system yields synergy: immobilized enzymes ensure operational stability, while in-situ cofactor regeneration guarantees reaction continuity, leading to a dramatic increase in overall catalytic efficiency.

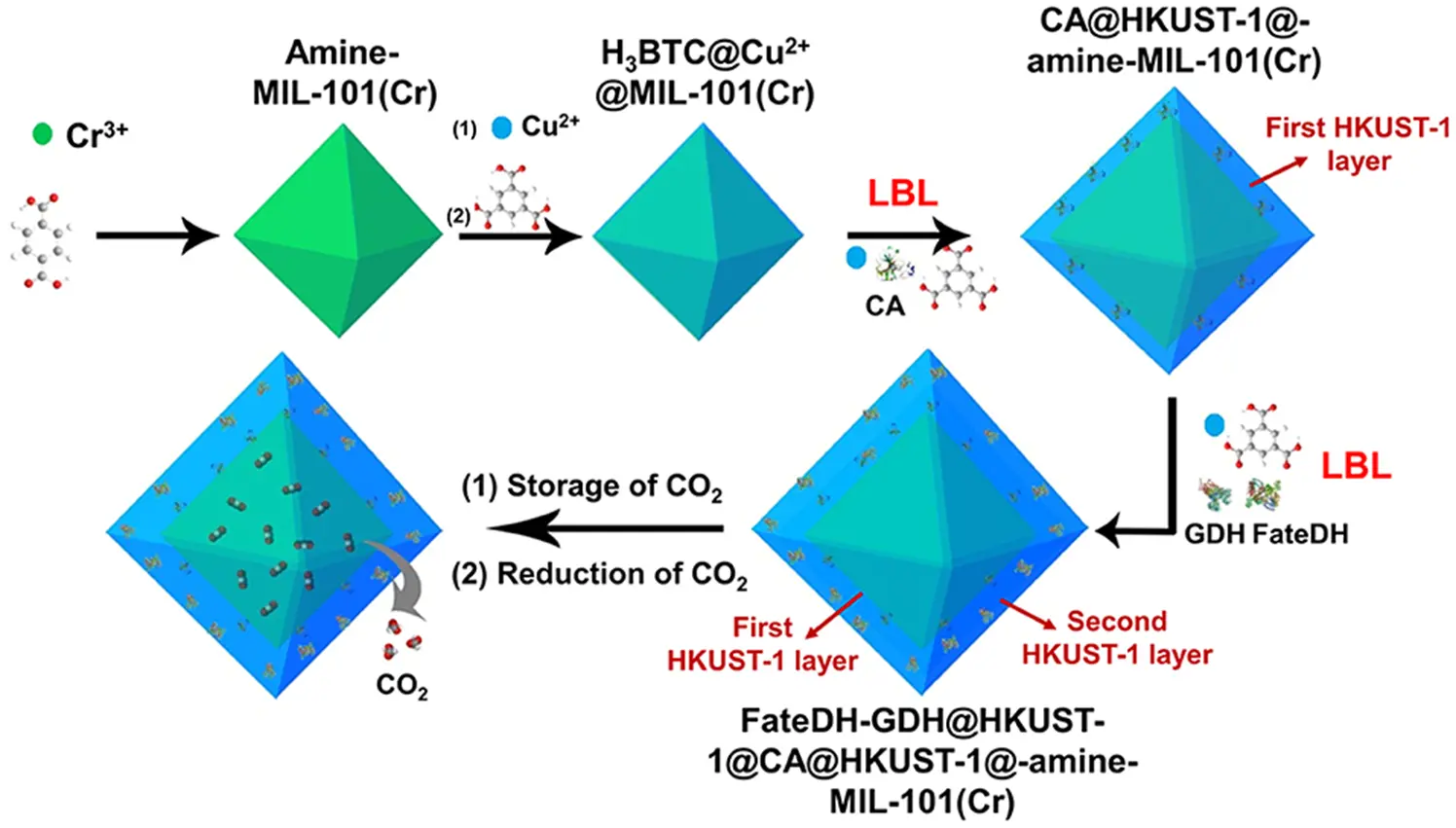

NAD(P)H cofactor is very expensive. Glucose dehydrogenase (GDH) belongs to the family of oxidoreductases. With NAD(P)+ as a coenzyme, GDH catalyzes the oxidation of D-glucose to D-glucose-δ-lactone, which spontaneously hydrolyzes to gluconic acid. Because this reaction is accompanied by formation, GDH is used much as a NAD(P)H recycling system [52]. Lv et al. [53] synthesized amine-functionalized MIL-101 (Cr) as the CO2 adsorption carrier and used it as the core to prepare two layers of HKUST-1, which were used to immobilize three enzymes for converting CO2 into formate (Figure 4). Among them, the CA enzyme was encapsulated in the inner layer of HKUST-1, hydrating the released CO2 to HCO3−. Then, the HCO3− directly migrated to the outer shell of HKUST-1 containing the FDH and was converted into formate. The GDH in the MOF outer layer was responsible for achieving the regeneration of the cofactor. Compared with free enzymes, the formate yield of the immobilized enzymes increased by 13.1 times, and the formate yield was 179.8%. The continuous immobilization of the enzymes also helped with the directional transport of the substrate, ultimately achieving a higher catalytic efficiency.

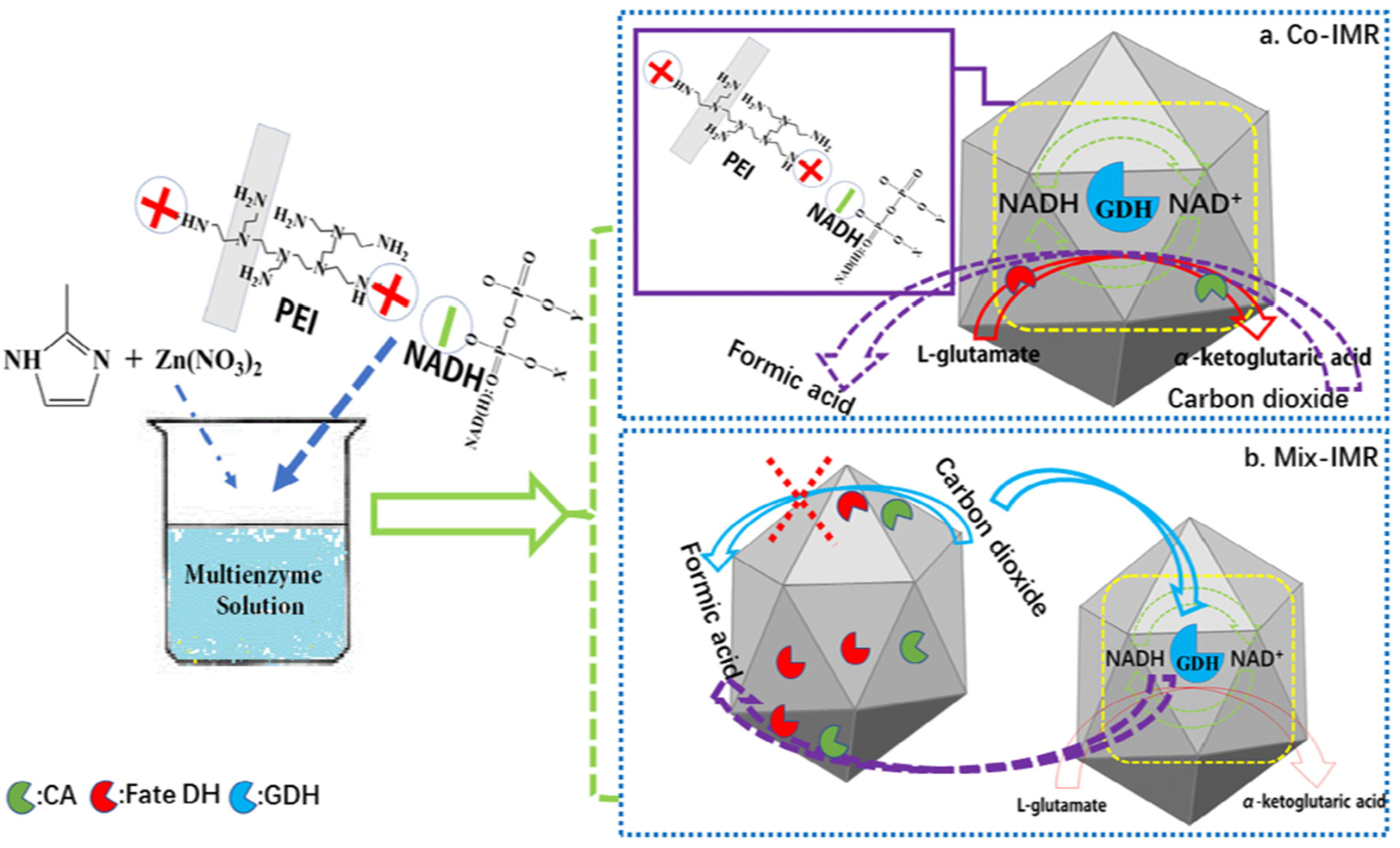

Cui et al. [54] proposed two immobilization strategies for multi-enzyme (including GDH) catalysis in ZIF-8 (Figure 5). One strategy (Co-IMR) is to construct a co-immobilized multi-enzyme reactor. In this reactor, the cofactor (NADH) is anchored in ZIF-8 through ion elements exchange between the positive charge of PEI and the negative charge of the cofactor, and is regenerated by embedding GDH in ZIF-8. CA in ZIF-8 accelerated the hydration of CO2, while FateDH converts CO2 into formate. Another strategy (Mix-IMR) is to co-embed CA and FateDH in ZIF-8 by the co-precipitation method, obtaining a biological catalyst (enzymes@ZIF-8), and embedding PEI, NADH, and GDH in another ZIF-8 to form a NADH regeneration system (NADH@ZIF-8). During the catalytic process, enzymes@ZIF-8 and NADH@ZIF-8 are mixed to achieve the conversion of CO2 to formate together. In terms of activity, the formate yield of Co-IMR is 5 times that of Mix-IMR. The reason for the difference may be that Co-IMR has a more optimized enzyme-cofactor co-immobilization structure design, reducing the mass transfer resistance, thereby improving the activity and stability.

Figure 4. Enzymatic CO2 conversion to formate with integrated NADH regeneration over HKUST-1@amine-MIL-101(Cr).

Figure 5. Two multi-enzyme immobilization strategies in ZIF-8 (Co-IMR and Mix-IMR) for converting CO2 to formate.

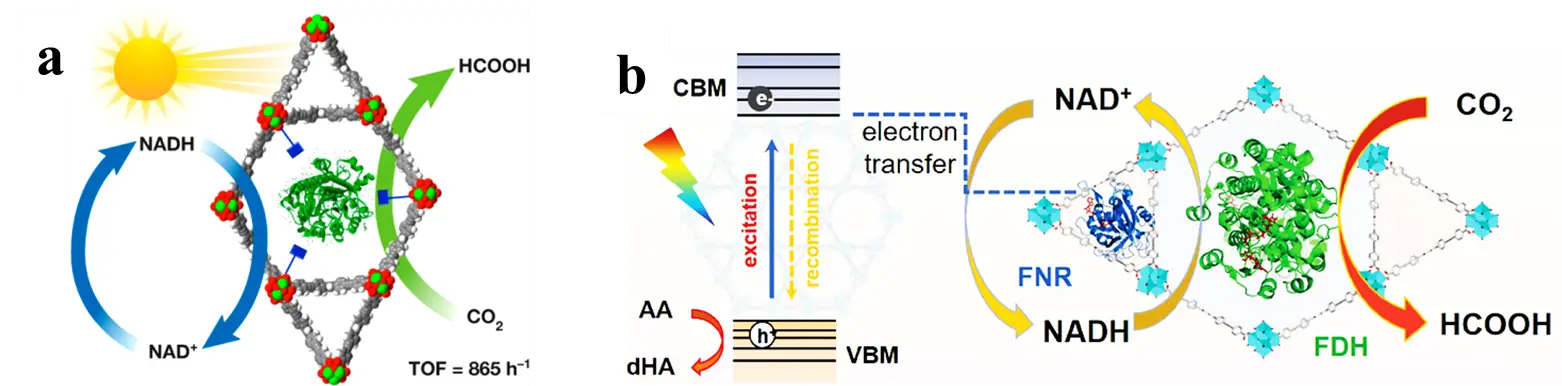

Farha and colleagues [29] immobilized both photosensitizers and enzymes within NU-1006. The mesoporous structure of the NU-1006 MOF not only provides sufficient surface area for the loading of enzymes, but its unique channel architecture also facilitates the rapid transfer of photogenerated electrons, thereby enhancing photocatalytic efficiency. The enzymes utilize these photogenerated electrons to catalyze the reduction of CO2, producing high-value formic acid (Figure 6a). Within 24 h, the immobilized enzyme system generated up to 144 mM of formic acid. Additionally, Rh-NU-1006 was able to convert 28% of the initial NAD+ after 2 h, which is approximately three times higher than that achieved by a physical mixture of the MOF and an electron mediator. Sun et al. [55] developed a multi-enzyme cascade system for cofactor-dependent photo-enzymatic CO2 conversion through a stepwise immobilization strategy that enables precise spatial organization of multiple enzymes within a Zr-MOF (Figure 6b). Upon photoexcitation, electrons are transferred from the framework to ferredoxin-NAD⁺ reductase (FNR), achieving efficient NADH regeneration with a conversion efficiency of 85%. The adjacent immobilized CbFDH then utilizes the regenerated NADH to reduce CO2 to formic acid. Within 12 h, the system produced 55 mM formic acid with a catalytic rate of 4580 μmol·g−1·h−1. This stepwise encapsulation strategy successfully localized CbFDH and FNR in distinct pore channels, which optimized enzyme loading distribution, prevented competitive binding between enzymes, and enhanced the transport efficiency of substrates and cofactors.

Figure 6. Photocatalytic regeneration of NADH and CO2 reduction in MOF-based enzyme composites: (a) FDH@Rh-NU-1006; (b) FDH/FNR@Zr-MOF.

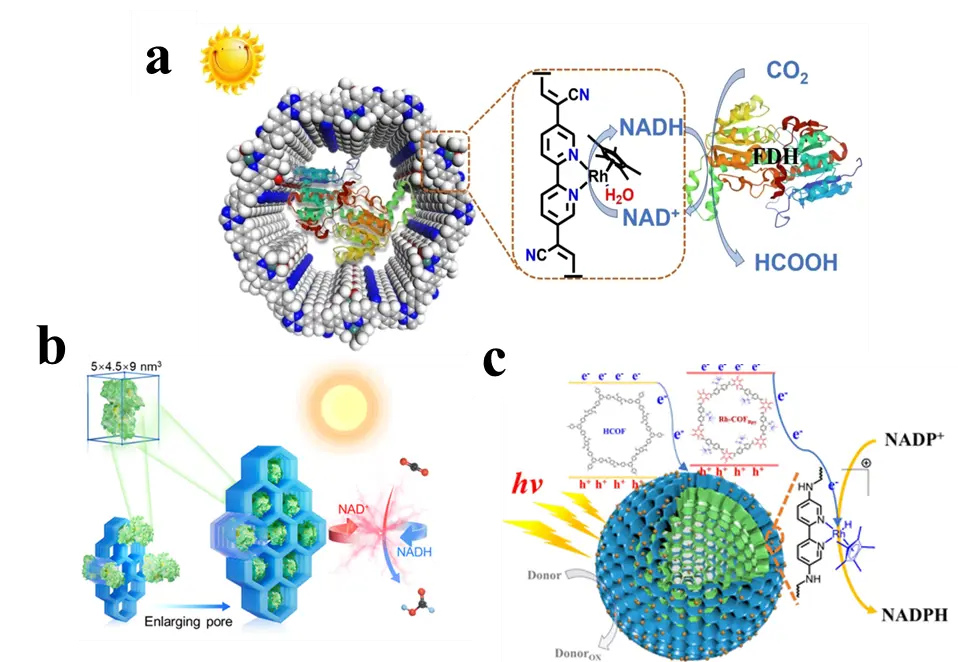

COFs, as promising semiconductor materials, exhibit excellent photoresponsivity [56]. Owing to features such as strong π–π interactions between adjacent layers and extensive conjugated systems within the layers, COFs generally possess broad absorption spectra and a strong ability to capture visible light. Chen et al. [57] reported the first integration of COF materials with photosensitizers(Cp*Rh(bpy)H2O) and biocatalysts for an artificial photosynthesis system. Using the mesoporous olefin-linked COF material NKCOF-113, they co-immobilized FDH and a rhodium-based electron mediator. This system captures sufficient visible light for efficient photoelectric conversion. The rhodium mediator Cp*Rh(bpy)H2O was coordinatively anchored to the COF skeleton, facilitating the transfer of photoexcited electrons for light-driven NADH regeneration. Meanwhile, FDH was embedded within the COF channels, forming an integrated photo-enzyme coupled system (Figure 7a). This synergistic photo-enzyme catalytic system achieved an apparent quantum yield of 9.17 ± 0.44% for NADH regeneration, enabling efficient and highly selective conversion of CO2 to formic acid. We have summarized the capabilities of several catalytic systems in converting CO2 into formic acid (Table 1). However, the dual role of COFs as both photocatalysts and enzyme carriers presents a conflict in structural preferences, posing challenges for their rational design. Luo et al. [58] investigated the synergistic matching of linkages and ligands in COFs to balance their photocatalytic activity and enzyme loading capacity (Figure 7b). They designed and synthesized four COFs combining two linkage types (imine and vinylene) with two ligands (phenyl and biphenyl), and used theoretical calculations to reveal how linkage-ligand matching influences exciton dissociation and charge migration in photocatalysis. Results showed that the optimal combination achieved an apparent quantum efficiency of 13.95% at 420 nm for photocatalytic cofactor regeneration, with a turnover frequency of 5.3 mmol·g−1·h−1. The constructed artificial photo-enzyme system exhibited highly efficient CO2 reduction performance, producing formic acid with a specific activity of 1.46 mmol·g−1·h−1 and good reusability. Jiang and colleagues [59] constructed a hollow core-shell Rh-COF@COF S-scheme heterojunction, which significantly enhanced the separation and transport of photogenerated charge carriers through its unique electron transfer pathway and built-in interfacial electric field. This system achieved highly efficient NADPH regeneration with a turnover frequency of 2.6 mmol·g−1·h−1. Furthermore, it successfully catalyzed the photoenzymatic reduction, yielding 92.5%, demonstrating its broad potential in photo-enzyme cascade synthesis. This study provides new design principles and experimental foundations for the application of COF-based heterojunctions in artificial photosynthetic systems (Figure 7c).

Table 1. Different porous framework materials as catalyst for HCOOH production.

|

Number |

Materials/Strategy |

Substrate/Enzyme |

HCOOH Yield (mM·h−1) |

References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1 |

Hierarchical pore HP-UiO-66-NH2 electrocatalytic NADH regeneration |

CO2/FDH |

0.609 |

[45] |

|

2 |

CA/FDH co-immobilized on PDA/PEI modified ZIF-8. |

CO2/CA |

0.0014 |

[46] |

|

3 |

MIL-101(Cr)/HKUST-1 core-shell structured tri-enzyme immobilization system |

CO2/CA, FDH, GDH |

0.833 |

[53] |

|

4 |

Co-immobilization of enzymes and NADH in ZIF-8. |

CO2/CA, FateDH, GDH |

~1.725 |

[54] |

|

5 |

Stepwise immobilization of two enzymes in a Zr-MOF |

CO2/CbFDH, FNR |

0.458 |

[55] |

|

6 |

FDH@Rh-NKCOF-113 |

CO2/FDH |

0.0036 |

[57] |

|

7 |

COF-V1/V2 with optimized linkage-ligand matching for photocatalysis |

CO2/FDH |

0.0144 |

[58] |

Figure 7. COF-based systems for photocatalytic cofactor regeneration and CO2 reduction: (a) FDH@Rh-NKCOF-113; (b) FDH@COFs (COF-V1 and COF-V2); (c) Rh-COFBpy@HCOF.

3.4. Regulation and Optimization of Metabolic Pathways

The study of microbial utilization of C1 compounds is currently still in its early stages. In nature, microorganisms capable of naturally utilizing C1 compounds primarily include microalgae, photosynthetic bacteria, acetogens, methanotrophs, and Pichia pastoris. Meanwhile, researchers are developing model industrial microorganisms such as Escherichia coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae to achieve efficient conversion of C1 compounds. However, current efforts remain largely focused on the establishment and optimization of C1 utilization pathways [4,60], with significant challenges persisting in catalytic efficiency, system stability, and industrial application. Porous framework materials demonstrate significant potential in regulating C1 bioconversion processes at the cellular and community levels, far beyond serving as mere enzyme carriers. By modulating interspecies electron transfer, microbial community structure, and even creating artificial catalytic pathways, porous framework materials can profoundly influence metabolic fluxes and enhance reaction performance.

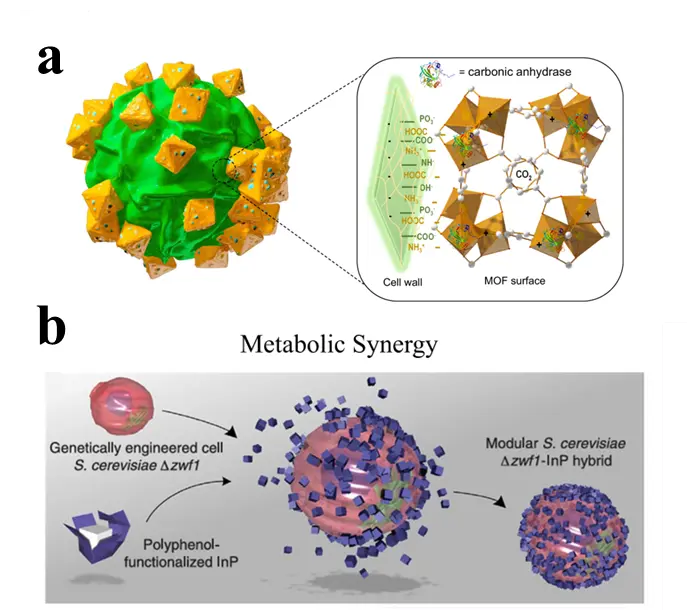

Microalgae demonstrate significant potential in biological CO2 fixation due to their short growth cycles, strong environmental adaptability, and photosynthetic carbon sequestration efficiency ten times higher than terrestrial plants. However, their practical application is limited by insufficient carbon source supply resulting from low CO2 solubility in water. To address this bottleneck, the use of nanomaterials to promote inorganic carbon conversion has emerged as an effective strategy. Hung et al. [49] developed Zn/Fe-MOF materials to construct a hybrid system for microalgae cultivation and CO2 fixation. This material integrates the rich microporous structure of Zn-MOF (providing high specific surface area) with the mesoporous characteristics of Fe-MOF (ensuring adsorption and desorption performance), while exhibiting hydrophilicity for uniform dispersion in microalgae solution. CO2 molecules are first concentrated and stored in MOF pores through physical adsorption at metal sites; subsequently, induced by CA on the surface of Scenedesmus obliquus, CO2 is desorbed and converted to HCO3−; the dissociated HCO3− is actively transported into the cytoplasm, where intracellular CA further converts it into high-concentration CO2 for utilization by RuBisCO in photosynthesis (Figure 8a). Experimental results show that adding 2.5 mg·L−1 of MOFs-3 (Zn/Fe molar ratio 10:1) significantly promotes inorganic carbon conversion, enhances biomass productivity and chlorophyll content, and increases the CO2 fixation efficiency of the system to 21.6%. Xu et al. [61] synthesized a series of ZIFs with different particle sizes and found that adding 0.01 mmol·L−1 of ZIF-8 nanoparticles significantly improved the CO2 mass transfer coefficient, increasing inorganic carbon concentration and biomass accumulation by 12.9% and 25.6%, respectively. Furthermore, to address the sensitivity of some CO2-fixing anaerobic bacteria to oxygen and reactive oxygen species (ROS). Yang et al. [62] utilized MOFs to encapsulate Moorella thermoacetica, providing cellular protection against oxidative stress damage. The results demonstrated that the ROS scavenging ability of MOFs reduced the mortality of strict anaerobic bacteria by fivefold under 21% O2 conditions and maintained their ability to continuously synthesize acetate through CO2 fixation under oxidative stress.

Beyond electrons as intermediates, specific microbial metabolites, notably bicarbonate ions (HCO3−) and NADPH, also serve as key intermediaries in CO2 fixation. Materials such as ZIF-8 facilitate CO2 adsorption and conversion into HCO3−, which is subsequently assimilated by microorganisms like A. platensis for carbon fixation [63]. Concurrently, in photocatalytic systems such as InP-S.cerevisiae, photogenerated electrons and holes drive NADPH regeneration, supplying essential reducing power for the conversion of CO2 into target organic compounds (Figure 8b).

Figure 8. Hybrid systems for enhanced CO2 fixation: (a) A Zn/Fe-MOF working synergistically with microalgae; (b) A bioinorganic hybrid where photogenerated electrons from InP nanoparticles drive NADPH regeneration in engineered S. cerevisiae.

Methane (CH4), a more potent greenhouse gas than CO2 [64], is present at relatively low atmospheric concentrations (~2.0 ppm). Once emitted, it becomes further diluted, posing significant challenges for enrichment and conversion. Methanotrophic bacteria utilize methane as their sole carbon and energy source through a unique metabolic pathway [65]. In aerobic methanotrophs, methane is first oxidized to methanol by methane monooxygenase (MMO), then to formaldehyde (HCHO) by methanol dehydrogenase (MDH), after which formaldehyde enters carbon assimilation routes. However, the efficiency of this methanotrophic pathway remains limited [66], constrained by the low solubility and mass transfer of both oxygen and methane in aqueous systems. In contrast, conventional industrial methods for methane oxidation often require high temperatures and pressures or costly oxidants, while biological fermentation and industrial methane to methanol processes demand strict reactor control and high methane concentrations, making them unsuitable for converting diluted methane under real environmental conditions [67].

Studies have shown that the addition of an appropriate amount of MOFs can significantly improve interspecies electron and hydrogen transfer efficiency by constructing proton-conducting networks, while also optimizing microbial community structure and reinforcing methanogenic metabolic pathways. In a study by Dai et al., the introduction of Zr-based MOF-808 at 0.5 g/L significantly improved anaerobic digestion performance, elevating total biogas production by 39.82% and raising methane content by 14.28% [68]. This improvement was attributed to two key factors: (i) the MOF-enhanced activity of essential enzymatic cofactors and hydrogenases (Figure 9a) [69], (ii) favorable restructuring of methanogenic microbial consortia. Mechanistic investigations revealed that protonation of the framework –OH groups under anaerobic conditions forms an extended hydrogen-bonded network within the MOF channels. This structure enables directional proton hopping, increasing H+ conductivity by 3.2-fold, which in turn enhances interspecies hydrogen transfer (IHT) efficiency and intensifies methanogenic energy metabolism, leading to significantly higher methane yields. In a complementary study, Liao et al. synthesized MOFs to evaluate their impact on CO2 biomethanation during anaerobic digestion [58]. The addition of MOFs at an optimal concentration of 1.0 g·L−1 substantially improved CO2 to methane conversion efficiency. This enhancement was associated with three synergistic effects: promoted direct interspecies electron transfer, an increased abundance of hydrogenotrophic methanogens, and reduced hydrogen competition among bacterial populations (Figure 9b) [70]. Furthermore, MOF supplementation increased the abundance of key methanogenesis-related enzymes, especially those involved in the hydrogenotrophic pathway-while simultaneously suppressing the activity of enzymes related to competing processes like nitrate reduction.

Beyond regulating natural microbial communities, framework materials can be integrated with biological components to create novel, artificial metabolic pathways that do not exist in nature. Strano et al. [71] developed a sustainable tandem methane oxidation system by coupling an iron-modified ZSM-5 (Fe-ZSM-5) zeolite catalyst with alcohol oxidase (AOX). In this system, methane is first oxidized to methanol over Fe-ZSM-5, which is subsequently converted by AOX into formaldehyde and hydrogen peroxide. The generated H2O2 further reacts with Fe-ZSM-5, promoting additional methane oxidation cycles. Under ambient temperature and pressure, the system achieves over 90% selectivity toward formaldehyde, comparable to the growth rates of many methanotrophic microorganisms.

Figure 9. MOF-assisted regulation of anaerobic digestion for enhanced methane production: (a) Enhancing interspecies hydrogen transfer and (b) Promoting direct interspecies electron transfer and microbial community restructuring.

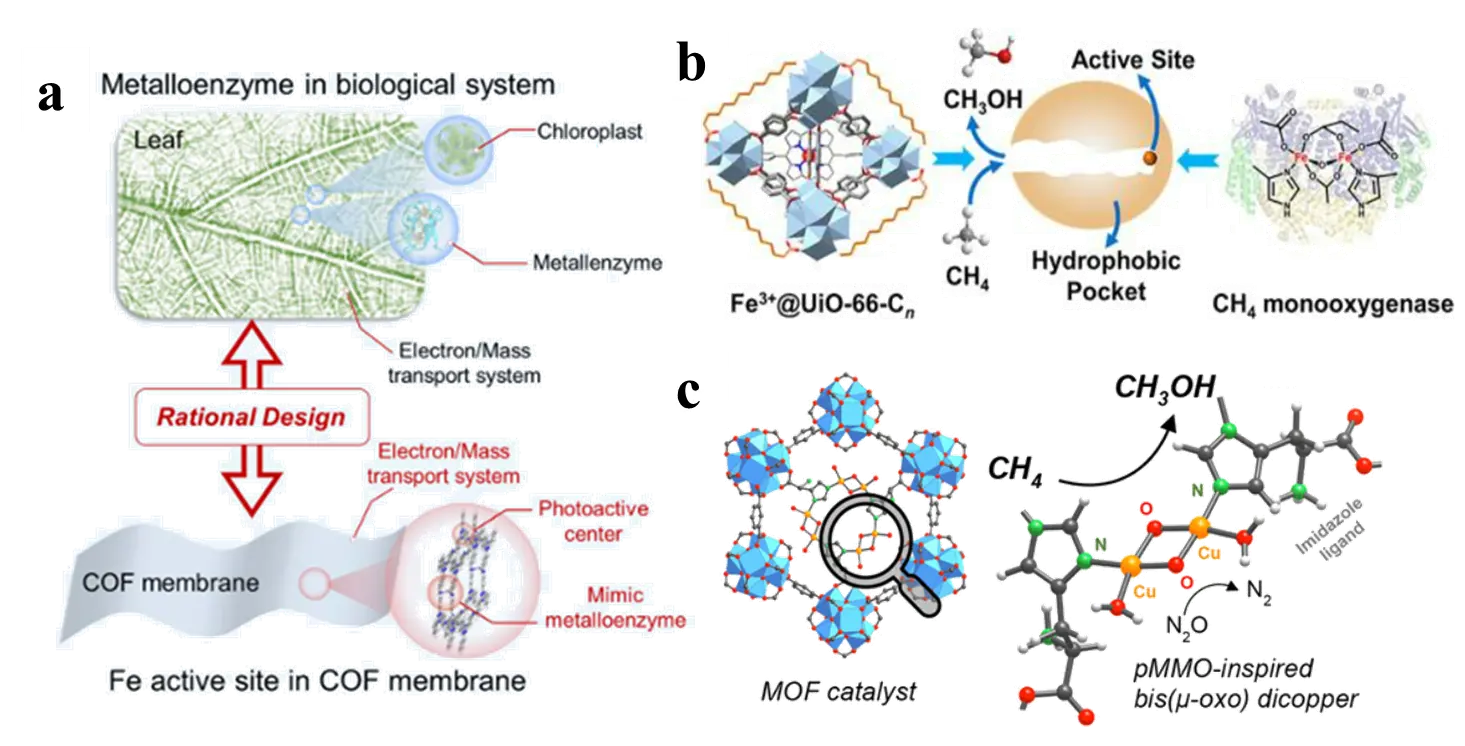

3.5. Artificial Enzyme Biomimetic Catalysis

Natural enzymes exhibit remarkable biocatalytic performance but are limited by their strict dependence on mild reaction conditions [72]. To address this, artificial enzymes, synthetic materials mimicking enzymatic activity, have been developed with enhanced stability and cost efficiency [73]. Porous framework materials such as MOFs, COFs, and HOFs are particularly promising due to their well-defined structures, high surface areas, and tunable porosity. These properties enable precise functionalization, providing abundant active sites while facilitating substrate and product diffusion, making them ideal platforms for emulating both the active sites and microenvironments of natural enzymes [73,74].

Gao et al. [74,75] successfully anchored atomically dispersed iron sites into the interlayer of a photoactive triazine-based COF (Fe-COF) membrane, creating a metalloenzyme-mimetic system (Figure 10a). This nitrogen-rich covalent organic framework membrane exhibited high CO2 photoreduction performance without the need for photosensitizers or sacrificial agents, achieving a mass-specific CO production rate of 3972 μg over 4 h with nearly 100% CO selectivity and excellent cycling stability. We summarized the capabilities of several catalytic systems in converting C1 (Table 2). The triazine-rich COF framework efficiently delivered more electrons to the iron catalytic centers, facilitating enhanced electron and mass transport. In another study, Sui et al. [76] immobilized iron porphyrin into UiO-66 and subsequently introduced saturated long-chain fatty acids to the Zr-oxo clusters via post-synthetic modification, developing Fe3+@UiO-66-Cn composites that mimic both the active site and the surrounding chemical microenvironment of soluble methane monooxygenase (sMMO, Figure 10b). As the alkyl chain length increased, the catalyst-methane interaction strengthened, CH4 adsorption enhanced, and the concentration of •OH radicals around Fe sites decreased. This suppression of methanol formation consequently improved methanol selectivity in the selective oxidation of methane. Similarly, inspired by the structure of particulate methane monooxygenase (pMMO), Baek et al. [77] grafted imidazole groups onto the MOF-808 framework and coordinated them with active copper-oxo complexes. The resulting catalyst demonstrated high selectivity toward methanol in methane oxidation under isothermal conditions at 150 °C (Figure 10c).

Figure 10. Porous framework materials as artificial enzyme mimics for C1 conversion: (a) A triazine-based Fe-COF for CO2 to CO photoreduction; (b) Fe3+@UiO-66-Cn for methane-to-methanol oxidation; (c) An imidazole-grafted MOF-808 for methane-to-methanol oxidation.

Table 2. Different porous framework materials catalyst for other production.

|

Number |

Materials/Strategy |

Key Performance Enhancement |

References |

|---|---|---|---|

|

1 |

HOF in-situ encapsulated four Enzyme cascades |

Average conversion rate of ethylene glycol: 7.15 × 10−7 mmol CO2·min−1·mg−1. |

[38] |

|

2 |

Filler-CA@Lys-HOF-1 (FCLH) composite |

Retained 85.4% of the initial activity after 10 cycles of reuse |

[41] |

|

3 |

FFFP@HOF-101 multi-enzyme cascade |

DHA production was 1.8 times higher than that of the free enzyme system |

[50] |

|

4 |

MOF encapsulated Moorella thermoacetica |

Reduced bacterial mortality by 5-fold under 21% O2 |

[62] |

|

5 |

Fe-COF membrane mimicking metalloenzymes |

Near 100% CO selectivity |

[75] |

4. Rational Design and Selection Strategies of Porous Framework Materials

4.1. Selection Strategy of Porous Framework Materials

The rational design and selection of porous framework materials (MOFs [28], COFs [78], and HOFs [79]) constitute a multi-dimensional optimization process. At its core, it involves customized framework selection and structural design based on the primary objectives of the application (such as stability, mass transport efficiency, or electron transfer performance) and the characteristics of the target biocatalyst.

MOFs are suitable for applications requiring high chemical stability, well-defined metal active sites, or mechanical strength for biocatalysts, while also considering the biocatalyst’s tolerance to metal ions [80]. COFs, with their long-range ordered π-π stacking and chemically stable covalent linkages, exhibit advantages in photo(electro)-coupled systems. Compared to MOFs, their pore structures are often more amenable to functionalization and customization [81]. HOFs, on the other hand, are suitable for processes with high biocompatibility requirements due to their excellent biological compatibility and mild synthesis conditions [82].

In structural design, pore size matching is a crucial principle to achieve efficient encapsulation of biocatalysts and meet the mass transport needs of substrates and products. Larger enzymes or cells are better accommodated through surface immobilization or framework encapsulation strategies, while small molecular cofactors can be confined via precisely controlled pore sizes [83]. Furthermore, when constructing photo/electro-bio hybrid systems, it is essential to balance the trade-off between enzyme loading and photo/electrocatalytic efficiency through approaches such as spatial zoning design, sequential optimization, and the introduction of linker molecules [59]. Ultimately, through such systematic design strategies, synergistic enhancement can be realized, moving beyond simple immobilization to create integrated, multifunctional platforms for efficient and stable C1 bioconversion.

4.2. Common Characterization Methods for Immobilized Biocatalysts Based on Porous Framework Materials

The systematic characterization of hybrid systems comprising biocatalysts immobilized within porous frameworks is indispensable for establishing reliable structure-property relationships and benchmarking performance. A comprehensive evaluation typically follows a logical progression, as illustrated here using the example of FDH@NKCOF-113 [57]. First, the physicochemical properties of the porous framework after the immobilization process must be verified. Powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) analysis indicates that the crystalline structure of the material is preserved after enzyme immobilization, with no phase transformation observed; Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR) confirms that the main chemical bonds of the framework remain intact and may detect potential interactions between the enzyme and the carrier; low-temperature nitrogen adsorption tests reveal a reasonable decrease in specific surface area and pore volume after immobilization, while the shape of the adsorption isotherm remains similar to that of the original material, indicating that the porous structure is not compromised. Together, these characterizations verify the integrity and stability of the carrier structure during the biocatalysts immobilization process [37].

Subsequently, direct evidence for the successful incorporation and spatial distribution of the biocatalyst is required. Energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX or EDS) can map the distribution of characteristic elements (e.g., from an enzyme tag or a unique framework component) within the composite. Alternatively, confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) of fluorescently labeled enzymes (e.g., with FITC) provides visual confirmation of the biocatalyst’s location—whether dispersed within the pores or coated on the material’s surface.

Ultimately, the efficacy of the engineered system must be validated by its catalytic function. The composite (e.g., FDH@NKCOF-113) is applied in the conversion reaction of C1 substrates (e.g., CO2), followed by qualitative and quantitative analysis of the reaction products using techniques such as High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) or Ion Chromatography (IC). This provides conclusive proof that the substrate has been successfully converted into the target product (e.g., formic acid) and allows for the calculation of key performance metrics such as conversion rate and selectivity.

5. Conclusions and Outlook

The integration of porous framework materials with biocatalysts presents a powerful strategy to overcome the inherent limitations of biological C1 conversion systems. This review has highlighted how these materials transcend their traditional role as mere immobilization scaffolds, acting as multifunctional platforms to enhance every aspect of the biocatalytic process. Looking forward, the development of this field hinges on addressing several interconnected challenges and opportunities across different levels of system integration.

At the enzyme level, the immobilization of enzymes within porous frameworks has unequivocally proven to enhance stability and recyclability. Future research should extend beyond the current limited repertoire of immobilized enzymes for C1 conversion. For instance, the exploration of novel enzymes, such as iron nitrogenase [84], which demonstrates superior CO2 reduction efficiency compared to its molybdenum counterpart, could be coupled with advanced frameworks. The parallel focus must be on the rational design of next-generation frameworks with optimized pore sizes, enhanced biocompatibility, and superior stability, while reducing synthesis costs. This should be coupled with advanced immobilization strategies, such as oriented immobilization to minimize mass transfer resistance and maximize enzyme activity.

At the whole-cell and system l evel, the synergy between frameworks and microorganisms, whether native or engineered, opens avenues for transformative applications. Advances in synthetic biology enable the construction of efficient artificial catalytic systems; a prime example is engineering E. coli with the reductive glycine pathway to synthesize bioplastics such as PHB from CO2 or formate [85]. Framework materials can be strategically designed to create a supportive microenvironment for these engineered strains, for instance, by regulating metabolic fluxes, protecting cells from oxidative stress (as demonstrated with MOF-encapsulated Moorella thermoacetica [62]), and ensuring efficient substrate delivery. The critical challenge here is to achieve true synergy, which requires a deep understanding of the material-microbe interface and a systematic evaluation of the long-term stability and biocompatibility of these hybrid systems.

At the material functionality level, the intrinsic properties of MOFs, COFs, and HOFs, such as their catalytic, photoactive, and electronic behaviors, are as valuable as their porosity. The future lies in designing truly multifunctional frameworks that seamlessly integrate capabilities for substrate enrichment, in-situ cofactor regeneration, and biomimetic catalysis within a single structure. While MOFs have been widely explored to mimic metalloenzymes (e.g., for methane to methanol conversion [76]), COFs and HOFs show immense promise in non-metallic catalysis and light-responsive applications. A key consideration is the judicious management of mass and energy flows within these complex systems to prevent inefficiencies and unwanted side reactions.

Although porous framework materials hold significant potential for C1 bioconversion, their transition from laboratory proof-of-concept to industrial application is hindered by several practical hurdles. First, in terms of material synthesis and stability, the synthesis of high-performance porous framework materials often involves high costs, harsh conditions, and batch-to-batch variability, necessitating the development of green and scalable preparation processes [37]. Additionally, MOFs may pose risks of metal leaching during long-term operation in aqueous phases, which can compromise structural integrity and potentially poison biocatalysts [32]. Second, regarding the preservation of biological function, enzyme immobilization requires a balance between binding strength and activity retention. Furthermore, the microenvironment within the pores and mass transfer limitations can affect long-term enzyme stability and reaction efficiency, requiring optimization through pore engineering and structural design. Third, system integration and scale-up face multifaceted challenges. Real-world gas feeds (e.g., flue gas, biogas) contain impurities (SOx, NOx, H2S) that can foul or poison catalysts, demanding that materials possess anti-poisoning capabilities or integrate effectively with pre-treatment processes. For advanced photo-/electro-bio hybrid systems, scaling up introduces complex engineering conflicts, such as optimizing mass transfer against light penetration, ensuring efficient electron flux throughout the reactor, and harmonizing disparate operational conditions (e.g., pH, temperature) for the coupled catalytic modules.

In conclusion, the union of biocatalysis and porous framework materials has established a robust foundation for advancing C1 biotransformation. The core value of these materials lies in their ability to precisely control the reaction microenvironment, thereby addressing the classic bottlenecks of gas substrate solubility, biocatalyst instability, and cofactor dependency. As material synthesis becomes more cost-effective and scalable, and as our understanding of the biological-material interface deepens, these hybrid systems are poised to move from laboratory breakthroughs to transformative applications in carbon capture, green manufacturing, and sustainable energy cycles.

Statement of the Use of Generative AI and AI-Assisted Technologies in the Writing Process

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT (OpenAI) in order to improve the writing quality. After using this tool, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the published article.

Acknowledgements

We appreciate the Nankai University and Institute of Process Engineering, Chinese Academy of Sciences, for research support.

Authors Contributions

J.Y.: Conceptualization, Literature search and data analysis, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing, Visualization; X.L.: Conceptualization, Literature search and data analysis, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing, Visualization; S.Q. and Y.Y.: Literature search and data analysis, Writing—original draft; Y.C.: Writing—review & editing, Funding acquisition, Supervision.

Ethics Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Funding

We appreciate the financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (22578462, and 22371136), Haihe Laboratory of Synthetic Biology (22HHSWSS00008), and Autonomous Deployment Project of State Key Laboratory of Biopharmaceutical Preparation and Delivery (Grant No. 2024ZZ-03, 2024-SJK-01, and 2024-FX-A-04).

Declaration of Competing Interest

All the authors of this manuscript declare no conflicts of interest.

References

-

Li D, Kassymova M, Cai X, Zang SQ, Jiang HL. Photocatalytic CO2 reduction over metal-organic framework-based materials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2020, 412, 213262. doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2020.213262. [Google Scholar]

-

Liu K-G, Bigdeli F, Panjehpour A, Larimi A, Morsali A, Dhakshinamoorthy A, et al. Metal organic framework composites for reduction of CO2. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2023, 493, 215257. doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2023.215257. [Google Scholar]

-

Shi S, Wang Y, Qiao W, Wu L, Liu Z, Tan T. Challenges and opportunities in the third-generation biorefinery. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2023, 68, 2489–2503. doi:10.1360/TB-2022-1210. [Google Scholar]

-

Park W, Cha S, Hahn JS. Advancements in Biological Conversion of C1 Feedstocks: Sustainable Bioproduction and Environmental Solutions. ACS Synth. Biol. 2024, 13, 3788–3798. doi:10.1021/acssynbio.4c00519. [Google Scholar]

-

Wang K, Su C, Bi H, Zhang C, Cai D, Liu Y, et al. The transition from 2G to 3G-feedstocks enabled efficient production of fuels and chemicals. GEE 2024, 9, 1759–1770. doi:10.1016/j.gee.2023.11.004. [Google Scholar]

-

Lv X, Yu W, Zhang C, Ning P, Li J, Liu Y, et al. C1-based biomanufacturing: Advances, challenges and perspectives. Bioresour. Technol. 2023, 367, 128259. doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2022.128259. [Google Scholar]

-

Qiao Y, Ma W, Zhang S, Guo F, Liu K, Jiang Y, et al. Artificial multi-enzyme cascades and whole-cell transformation for bioconversion of C1 compounds: Advances, challenge and perspectives. Synth. Syst. Biotechnol. 2023, 8, 578–583. doi:10.1016/j.synbio.2023.08.008. [Google Scholar]

-

El-Zahab B, Donnelly D, Wang P. Particle-tethered NADH for production of methanol from CO2 catalyzed by co-immobilized enzymes. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2010, 99, 508–514. doi:10.1002/bit.21584. [Google Scholar]

-

Dumitru R, Palencia H, Schroeder SD, DeMontigny BA, Takacs JM, Rasche ME, et al. Targeting methanopterin biosynthesis to inhibit methanogenesis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2003, 69, 7236–7241. doi:10.1128/AEM.69.12.7236-7241.2003. [Google Scholar]

-

Wang KY, Zhang J, Hsu YC, Lin H, Han Z, Pang J, et al. Bioinspired Framework Catalysts: From Enzyme Immobilization to Biomimetic Catalysis. Chem. Rev. 2023, 123, 5347–5420. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.2c00879. [Google Scholar]

-

Chen L, Luque R, Li Y. Controllable design of tunable nanostructures inside metal-organic frameworks. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2017, 46, 4614–4630. doi:10.1039/C6CS00537C. [Google Scholar]

-

Ma L, Jiang F, Fan X, Wang L, He C, Zhou M, et al. Metal-Organic-Framework-Engineered Enzyme-Mimetic Catalysts. Adv. Mater. 2020, 32, e2003065. doi:10.1002/adma.202003065. [Google Scholar]

-

Wang D, Yao H, Ye J, Gao Y, Cong H, Yu B. Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs): Classification, Synthesis, Modification, and Biomedical Applications. Small 2024, 20, e2404350. doi:10.1002/smll.202404350. [Google Scholar]

-

An X, Yang D. 2D monolayer electrocatalysts for CO2 electroreduction. Nanoscale 2025, 17, 4212–4225. doi:10.1039/D4NR04109G. [Google Scholar]

-

Zhang L, Zheng Q, Zhang Z, Li H, Liu X, Sun J, et al. Application of Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) in Environmental Biosystems. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 2145. doi:10.3390/ijms24032145. [Google Scholar]

-

Beuerle F, Gole B. Covalent Organic Frameworks and Cage Compounds: Design and Applications of Polymeric and Discrete Organic Scaffolds. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 4850–4878. doi:10.1002/anie.201710190. [Google Scholar]

-

Hisaki I, Xin C, Takahashi K, Nakamura T. Designing Hydrogen-Bonded Organic Frameworks (HOFs) with Permanent Porosity. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 11160–11170. doi:10.1002/anie.201902147. [Google Scholar]

-

Xiao K, Shu B, Lv K, Chang PP, Wu Q, Wang LY, et al. Recent Progress of MIL MOF Materials in Degradation of Organic Pollutants by Fenton Reaction. Catalysts 2023, 13, 734. doi:10.3390/catal13040734. [Google Scholar]

-

Yu J, Fu H, Zhu H, Yang Y, Di Z, Zhou S, et al. Fabricating streptavidin-embedded metal-organic frameworks for noninvasive gene detection of Helicobacter pylori infection. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2025, 289, 117860. doi:10.1016/j.bios.2025.117860. [Google Scholar]

-

El-Kaderi HM, Hunt JR, Mendoza-Cortés JL, Côté AP, Taylor RE, O’Keeffe M, et al. Designed synthesis of 3D covalent organic frameworks. Science 2007, 316, 268–272. doi:10.1126/science.1139915. [Google Scholar]

-

Han YF, Yuan YX, Wang HB. Porous Hydrogen-Bonded Organic Frameworks. Molecules 2017, 22, 266. doi:10.3390/molecules22020266. [Google Scholar]

-

Liu Y, Chang G, Zheng F, Chen L, Yang Q, Ren Q, et al. Hybrid Hydrogen-Bonded Organic Frameworks: Structures and Functional Applications. Chemistry 2023, 29, e202202655. doi:10.1002/chem.202202655. [Google Scholar]

-

Horcajada P, Chalati T, Serre C, Gillet B, Sebrie C, Baati T, et al. Porous metal-organic-framework nanoscale carriers as a potential platform for drug delivery and imaging. Nat. Mater. 2010, 9, 172–178. doi:10.1038/nmat2608. [Google Scholar]

-

Yang XG, Zhang JR, Tian XK, Qin JH, Zhang XY, Ma LF. Enhanced Activity of Enzyme Immobilized on Hydrophobic ZIF-8 Modified by Ni2+ Ions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202216699. doi:10.1002/anie.202216699. [Google Scholar]

-

Zhang S, Du M, Shao P, Wang L, Ye J, Chen J, et al. Carbonic Anhydrase Enzyme-MOFs Composite with a Superior Catalytic Performance to Promote CO(2) Absorption into Tertiary Amine Solution. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 12708–12716. doi:10.1021/acs.est.8b04671. [Google Scholar]

-

Zhang Y, Wang H, Liu J, Hou J, Zhang Y. Enzyme-embedded metal–organic framework membranes on polymeric substrates for efficient CO2 capture. J. Mater. Chem. A 2017, 5, 19954–19962. doi:10.1039/C7TA03719H. [Google Scholar]

-

Tran QN, Lee HJ, Tran N. Covalent Organic Frameworks: From Structures to Applications. Polymers 2023, 15, 1279. doi:10.3390/polym15051279. [Google Scholar]

-

Zhou HC, Kitagawa S. Metal-organic frameworks (MOFs). Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 5415–5418. doi:10.1039/C4CS90059F. [Google Scholar]

-

Chen Y, Li P, Zhou J, Buru CT, Đorđević L, Li P, et al. Integration of Enzymes and Photosensitizers in a Hierarchical Mesoporous Metal-Organic Framework for Light-Driven CO(2) Reduction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 1768–1773. doi:10.1021/jacs.9b12828. [Google Scholar]

-

Shang Y, Ma L, Kang Z, Wu Y, Fan W, Wang R, et al. Integrated Monomer Synthesis and Framework Assembly: Achieving Isoreticular Modulation of Hydrogen-Bonded Organic Frameworks. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2025, 64, e202416966. doi:10.1002/anie.202416966. [Google Scholar]

-

Feng J, Huang QY, Zhang C, Ramakrishna S, Dong YB. Review of covalent organic frameworks for enzyme immobilization: Strategies, applications, and prospects. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 248, 125729. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.125729. [Google Scholar]

-

Brena B, González-Pombo P, Batista-Viera F. Immobilization of enzymes: A literature survey. Methods Mol. Biol. 2013, 1051, 15–31. doi:10.1007/978-1-62703-550-7_2. [Google Scholar]

-

Liese A, Hilterhaus L. Evaluation of immobilized enzymes for industrial applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 6236–6249. doi:10.1039/c3cs35511j. [Google Scholar]

-

Gama Cavalcante AL, Dari DN, Izaias da Silva Aires F, Carlos de Castro E, Moreira Dos Santos K, Sousa Dos Santos JC. Advancements in enzyme immobilization on magnetic nanomaterials: Toward sustainable industrial applications. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 17946–17988. doi:10.1039/D4RA02939A. [Google Scholar]

-

Zhu Q, Zheng Y, Zhang Z, Chen Y. Enzyme immobilization on covalent organic framework supports. Nat. Protocal 2023, 18, 3080–3125. doi:10.1038/s41596-023-00868-x. [Google Scholar]

-

Fan X, Zhai S, Xue S, Zhi L. Enzyme Immobilization using Covalent Organic Frameworks: From Synthetic Strategy to COFs Functional Role. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 40371–40390. doi:10.1021/acsami.4c06556. [Google Scholar]

-

Sicard C. In Situ Enzyme Immobilization by Covalent Organic Frameworks. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202213405. doi:10.1002/anie.202213405. [Google Scholar]

-

Luan L, Zhang Y, Ji X, Guo B, Song S, Huang Y, et al. Electro-Driven Multi-Enzymatic Cascade Conversion of CO2 to Ethylene Glycol in Nano-Reactor. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, e2407204. doi:10.1002/advs.202407204. [Google Scholar]

-

Silva Almeida C, Simão Neto F, da Silva Sousa P, da Silva Aires FI, de Matos Filho JR, Gama Cavalcante AL, et al. Enhancing Lipase Immobilization via Physical Adsorption: Advancements in Stability, Reusability, and Industrial Applications for Sustainable Biotechnological Processes. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 46698–46732. doi:10.1021/acsomega.4c07088. [Google Scholar]

-

Wang M, Mohanty SK, Mahendra S. Nanomaterial-Supported Enzymes for Water Purification and Monitoring in Point-of-Use Water Supply Systems. Acc. Chem. Res. 2019, 52, 876–885. doi:10.1021/acs.accounts.8b00613. [Google Scholar]

-

Zhang BY, Wu ZH, Chu ZY, Li K, Shi JF. Carbonic Anhydrase-Embedded Hydrogen-Bonded Organic Frameworks Coating for Facilitated Offshore CO2 Fixation. ChemBioChem 2023, 24, e202300114. doi:10.1002/cbic.202300114. [Google Scholar]

-

Wu E, Li Y, Huang Q, Yang Z, Wei A, Hu Q. Laccase immobilization on amino-functionalized magnetic metal organic framework for phenolic compound removal. Chemosphere 2019, 233, 327–335. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.05.150. [Google Scholar]

-

Schoevaart R, Wolbers MW, Golubovic M, Ottens M, Kieboom AP, van Rantwijk F, et al. Preparation, optimization, and structures of cross-linked enzyme aggregates (CLEAs). Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2004, 87, 754–762. doi:10.1002/bit.20184. [Google Scholar]

-

Jun SH, Yang J, Jeon H, Kim HS, Pack SP, Jin E, et al. Stabilized and Immobilized Carbonic Anhydrase on Electrospun Nanofibers for Enzymatic CO2 Conversion and Utilization in Expedited Microalgal Growth. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 1223–1231. doi:10.1021/acs.est.9b05284. [Google Scholar]

-

Yan L, Liu G, Liu J, Bai J, Li Y, Chen H, et al. Hierarchically porous metal organic framework immobilized formate dehydrogenase for enzyme electrocatalytic CO2 reduction. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 450, 138164. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2022.138164. [Google Scholar]

-

Chai M, Razmjou A, Chen V. Metal-organic-framework protected multi-enzyme thin-film for the cascade reduction of CO2 in a gas-liquid membrane contactor. J. Membr. Sci. 2021, 623, 118986. doi:10.1016/j.memsci.2020.118986. [Google Scholar]

-

Chai M, Bazaz SR, Daiyan R, Razmjou A, Chen V. Biocatalytic micromixer coated with enzyme-MOF thin film for CO2 conversion to formic acid. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 426, 130856. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2021.130856. [Google Scholar]

-

Banerjee T, Gottschling K, Savasci G, Ochsenfeld C, Lotsch BV. H2 Evolution with Covalent Organic Framework Photocatalysts. ACS Energy Lett. 2018, 3, 400–409. doi:10.1021/acsenergylett.7b01123. [Google Scholar]

-

Yang YW, Li MJ, Hung TC. Enhancing CO2 dissolution and inorganic carbon conversion by metal-organic frameworks improves microalgal growth and carbon fixation efficiency. Bioresour Technol 2024, 407, 131113. doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2024.131113. [Google Scholar]

-

Pei R, Liu J, Jing C, Zhang M. A Multienzyme Cascade Pathway Immobilized in a Hydrogen-Bonded Organic Framework for the Conversion of CO2. Small 2024, 20, e2306117. doi:10.1002/smll.202306117. [Google Scholar]

-

Chong Z. Research Progress in Cofactor Regeneration Systems. Chin. J. Biotechnol. 2004, 20, 811–816. doi:10.3321/j.issn:1000-3061.2004.06.001 [Google Scholar]

-

Lee H, Lee YS, Reginald SS, Baek S, Lee EM, Choi IG, et al. Biosensing and electrochemical properties of flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD)-Dependent glucose dehydrogenase (GDH) fused to a gold binding peptide. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2020, 165, 112427. doi:10.1016/j.bios.2020.112427. [Google Scholar]

-

Li Y, Wen L, Tan T, Lv Y. Sequential Co-immobilization of Enzymes in Metal-Organic Frameworks for Efficient Biocatalytic Conversion of Adsorbed CO2 to Formate. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2019, 7, 394. doi:10.3389/fbioe.2019.00394. [Google Scholar]

-

Ren S, Wang Z, Bilal M, Feng Y, Jiang Y, Jia S, et al. Co-immobilization multienzyme nanoreactor with co-factor regeneration for conversion of CO2. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 155, 110–118. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.03.177. [Google Scholar]

-

Li Y, Wang J, Shi X, Yu X, Yu S, Liu J, et al. Spatiotemporal Encapsulation of Tandem Enzymes in Hierarchical Metal-Organic Frameworks for Cofactor-Dependent Photoenzymatic CO2 Conversion. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, e2410024. doi:10.1002/advs.202410024. [Google Scholar]

-

Liang Z, Shen R, Zhang P, Li Y, Li N, Li X. All-organic covalent organic frameworks/perylene diimide urea polymer S-scheme photocatalyst for boosted H2 generation. Chin. J. Catal. 2022, 43, 2581–2591. doi:10.1016/S1872-2067(22)64130-5. [Google Scholar]

-

Zhao Z, Zheng D, Guo J, Yu J, Zhang S, Zhang Z, et al. Engineering Olefin-Linked Covalent Organic Frameworks for Photoenzymatic Reduction of CO2. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202200261. doi:10.1002/anie.202200261. [Google Scholar]

-

Chen Q, Wang Y, Luo G. Photoenzymatic CO2 Reduction Dominated by Collaborative Matching of Linkage and Linker in Covalent Organic Frameworks. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024, 146, 586–598. doi:10.1021/jacs.3c10350. [Google Scholar]

-

Zhao H, Wang L, Liu G, Liu Y, Zhang S, Wang L, et al. Hollow Rh-COF@COF S-Scheme Heterojunction for Photocatalytic Nicotinamide Cofactor Regeneration. ACS Catal. 2023, 13, 6619–6629. doi:10.1021/acscatal.2c06332. [Google Scholar]

-

Zhu Z, Tian J, Geng P, Li M, Cao X. Chlamydomonas reinhardtii chloroplast factory construction for formate bioconversion. Bioresour. Technol. 2024, 401, 130757. doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2024.130757. [Google Scholar]

-

Xu J, Cheng J, Wang Y, Yang W, Park J-Y, Kim H, et al. Strengthening CO2 dissolution with zeolitic imidazolate framework-8 nanoparticles to improve microalgal growth in a horizontal tubular photobioreactor. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 405, 126062. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2020.126062. [Google Scholar]

-

Ji Z, Zhang H, Liu H, Yaghi OM, Yang P. Cytoprotective metal-organic frameworks for anaerobic bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 10582–10587. doi:10.1073/pnas.1808829115. [Google Scholar]

-

Cheng J, Zhu Y, Xu X, Zhang Z, Yang W. Enhanced biomass productivity of Arthrospira platensis using zeolitic imidazolate framework-8 as carbon dioxide adsorbents. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 294, 122118. doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2019.122118. [Google Scholar]

-

Tang X, Wilson SR, Solomon KR, Shao M, Madronich S. Changes in air quality and tropospheric composition due to depletion of stratospheric ozone and interactions with climate. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2011, 10, 280–291. doi:10.1039/c0pp90039g. [Google Scholar]

-

Conrado RJ, Gonzalez R. Chemistry. Envisioning the bioconversion of methane to liquid fuels. Science 2014, 343, 621–623. doi:10.1126/science.1246929. [Google Scholar]

-

Liao JC, Mi L, Pontrelli S, Luo S. Fuelling the future: Microbial engineering for the production of sustainable biofuels. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2016, 14, 288–304. doi:10.1038/nrmicro.2016.32. [Google Scholar]

-

Durán J, Rodríguez A, Fangueiro D, De Los Ríos A. In-situ soil greenhouse gas fluxes under different cryptogamic covers in maritime Antarctica. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 770, 144557. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.144557. [Google Scholar]

-

Luo J, Meyer AS, Mateiu RV, Pinelo M. Cascade catalysis in membranes with enzyme immobilization for multi-enzymatic conversion of CO2 to methanol. New Biotechnol. 2015, 32, 319–327. doi:10.1016/j.nbt.2015.02.006. [Google Scholar]

-

Chen S, Hua Y, Dai L, Dai X. High Proton Conductivity of MOF-808 Promotes Methane Production in Anaerobic Digestion. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 1419–1429. doi:10.1021/acssuschemeng.1c06418. [Google Scholar]

-

Dong Z, Ding Y, Chen F, Zhu X, Wang H, Cheng M, et al. Enhanced carbon dioxide biomethanation with hydrogen using anaerobic granular sludge and metal-organic frameworks: Microbial community response and energy metabolism analysis. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 362, 127822. doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2022.127822. [Google Scholar]

-

Lundberg DJ, Kim J, Tu YM. Concerted methane fixation at ambient temperature and pressure mediated by an alcohol oxidase and Fe-ZSM-5 catalytic couple. Nat. Catal. 2024, 7, 1359–1371. doi:10.1038/s41929-024-01251-z. [Google Scholar]

-

Hu G, Li Z, Ma D, Ye C, Zhang L, Gao C, et al. Light-driven CO2 sequestration in Escherichia coli to achieve theoretical yield of chemicals. Nat. Catal. 2021, 4, 395–406. doi:10.1038/s41929-021-00606-0. [Google Scholar]

-

Wu J, Wang X, Wang Q, Lou Z, Li S, Zhu Y, et al. Nanomaterials with enzyme-like characteristics (nanozymes): Next-generation artificial enzymes (II). Chem. Soc. Rev. 2019, 48, 1004–1076. doi:10.1039/C8CS00457A. [Google Scholar]

-

Gao R, Zhong N, Huang S, Li S, Chen G, Ouyang G. Multienzyme Biocatalytic Cascade Systems in Porous Organic Frameworks for Biosensing. Chemistry 2022, 28, e202200074. doi:10.1002/chem.202283461. [Google Scholar]

-

Gao S, Zhao X, Zhang Q, Guo L, Li Z, Wang H, et al. Mimic metalloenzymes with atomically dispersed Fe sites in covalent organic framework membranes for enhanced CO2 photoreduction. Chem. Sci. 2025, 16, 1222–1232. doi:10.1039/D4SC05999A. [Google Scholar]

-

Sui J, Gao ML, Qian B, Liu C, Pan Y, Meng Z, et al. Bioinspired microenvironment modulation of metal-organic framework-based catalysts for selective methane oxidation. Sci. Bull. 2023, 68, 1886–1893. doi:10.1016/j.scib.2023.07.031. [Google Scholar]

-

Baek J, Rung B, Pei X, Park M, Fakra SC, Liu YS, et al. Bioinspired Metal-Organic Framework Catalysts for Selective Methane Oxidation to Methanol. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 18208–18216. doi:10.1021/jacs.8b11525. [Google Scholar]

-

Côté AP, Benin AI, Ockwig NW, O’Keeffe M, Matzger AJ, Yaghi OM. Porous, crystalline, covalent organic frameworks. Science 2005, 310, 1166–1170. doi:10.1126/science.1120411. [Google Scholar]

-

Li Y, Wang X, Zhang H, He L, Huang J, Wei W, et al. A Microporous Hydrogen Bonded Organic Framework for Highly Selective Separation of Carbon Dioxide over Acetylene. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202311419. doi:10.1002/anie.202311419. [Google Scholar]

-

Yusuf VF, Malek NI, Kailasa SK. Review on Metal-Organic Framework Classification, Synthetic Approaches, and Influencing Factors: Applications in Energy, Drug Delivery, and Wastewater Treatment. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 44507–44531. doi:10.1021/acsomega.2c05310. [Google Scholar]

-

Bié J, Sepodes B, Fernandes PCB, Ribeiro MHL. Enzyme Immobilization and Co-Immobilization: Main Framework, Advances and Some Applications. Processes 2022, 10, 494. doi:10.3390/pr10030494. [Google Scholar]

-

Aggarwal S, Chakravarty A, Ikram S. A comprehensive review on incredible renewable carriers as promising platforms for enzyme immobilization & thereof strategies. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 167, 962–986. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.11.052. [Google Scholar]

-

Gong G, Yang B, Chen Y, Xia N, Xiong Y, Asamannaba DA, et al. COFs, MOFs, HOFs, SOFs and XOFs: Commonalities and differences. Chem. Commun. 2025, 61, 12885–12903. doi:10.1039/D5CC03788C. [Google Scholar]

-

Oehlmann NN, Schmidt FV, Herzog M, Goldman AL, Rebelein JG. The iron nitrogenase reduces carbon dioxide to formate and methane under physiological conditions: A route to feedstock chemicals. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, 7729. doi:10.1126/sciadv.ado7729. [Google Scholar]

-

Fedorova D, Ben-Nissan R, Milshtein E, Reyes C, Jona G, Dezorella N, et al. Demonstration of bioplastic production from CO2 and formate using the reductive glycine pathway in E. coli. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0327512. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0327512. [Google Scholar]