Bioaccessibility Evaluation by In Vitro Digestion of Microencapsulated Extracts of Habanero Pepper Leaves Obtained Through an Optimized Spray-Drying Process

Received: 30 October 2025 Revised: 11 December 2025 Accepted: 04 January 2026 Published: 08 January 2026

© 2026 The authors. This is an open access article under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

1. Introduction

The Habanero pepper (Capsicum chinense Jacq.) is globally recognized for its distinctive organoleptic profile, intense pungency, and richness in bioactive compounds. However, other parts of the plant, as leaves, contain valuable biomolecules including phenolic acids, flavonoids, vitamins, and carotenoids [1,2]. These compounds are influenced by the pedoclimatic conditions of the Yucatán Peninsula, where the C. chinense “Mayapán” and “Jaguar” varieties received Designation of Origin status in 2010 due to their unique phytochemical and agronomic characteristics [3]. On the other hand, the region’s expanding production, driven by food, nutraceutical, and pharmaceutical industries, has generated significant agro-industrial residues. Around 80% of the non-industrialized biomass, such as leaves and stems, is discarded or burned after fruit harvesting, despite constituting an underutilized source of phenolic compounds with notable antioxidant and anti-inflammatory potential [4,5].

Among these by-products, habanero pepper leaves have attracted increasing attention for their phenolic composition and Ax, largely attributed to compounds such as quercetin, caffeic acid, and rutin [4]. However, conventional extraction techniques using ethanol or methanol often compromise compound stability and generate solvent waste, limiting scalability and sustainability. NADES have gained attention as sustainable solvent systems due to their ability to effectively dissolve diverse phenolic compounds. This capacity is attributed to the formation of extensive hydrogen-bonding interactions between hydrogen bond donors (HBDs) and hydrogen bond acceptors (HBAs), which enhance solvation efficiency while maintaining an environmentally friendly profile [6,7]. These NADES, typically composed of biodegradable primary metabolites such as choline chloride, sugars, and organic acids, have demonstrated high selectivity, low toxicity, and compliance with the principles of green chemistry [8]. Recent studies have shown that the combination of NADES and ultrasound-assisted extraction (UAE) enhances mass transfer and disrupts cell walls, achieving higher extraction yields of phenolic compounds from plant residues compared to conventional solvents [9,10].

While numerous studies have optimized NADES composition for extraction efficiency, limited information exists regarding the stability and the in vitro digestibility of NADES-derived extracts when formulated as microencapsulated powders. Polyphenols, although biologically active, are susceptible to oxidation and degradation during processing and gastrointestinal transit [11]. Therefore, encapsulation technologies, particularly spray drying, have gained prominence for improving the stability, handling, and controlled release of plant-derived antioxidants [12,13]. Encapsulation with carbohydrate matrices such as maltodextrin, modified starch, or galactomannans (e.g., Guar gum) forms protective amorphous films that reduce oxygen permeability and enhance the resistance of bioactives under gastric and intestinal conditions [14,15].

The assessment of in vitro bioaccessibility, defined as the fraction of a compound released from the food matrix and available for absorption, has become a key indicator of the functional potential of microencapsulated extracts (Barba et al., 2023). Studies on grape pomace, oregano, and Astrocaryum vulgare extracts have reported significant differences in phenolic release and antioxidant recovery depending on the wall material composition and digestion conditions [11,16]. However, the behavior of NADES-derived phenolic extracts from C. chinense leaves during simulated digestion remains unexplored, particularly regarding the release kinetics and antioxidant response throughout gastric and intestinal phases.

Accordingly, this study proposes an integrative approach combining green extraction using NADES with spray-drying microencapsulation to evaluate the in vitro bioaccessibility of phenolic compounds from C. chinense leaf extracts. The research aims to quantify the changes in TPC and Ax during simulated gastrointestinal digestion of the microencapsulated habanero pepper leaf extract.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals, Reagents, and Plant Material

All reagents, including sodium carbonate (Na2CO3), 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH), Folin–Ciocalteu reagent, methanol, choline chloride, glucose, and guar gum, were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich® (St. Louis, MO, USA). Maltodextrin (DE 17–20; Maltrin® M200) was supplied by Maltrin® (Mexico City, Mexico). Plant material consisted of leaves from the Jaguar cultivar of habanero pepper (Capsicum chinense Jacq.).

The crop was grown under greenhouse conditions in black soil, locally known as Boox Lu’um according to the Mayan soil classification system, in the Chablekal community, Yucatán, Mexico (21°06′02.3″ N, 89°33′40.5″ W). Leaf samples were collected during the initial fruiting stage, corresponding to 120 days after transplantation.

2.2. Polyphenol Extraction from Habanero Pepper Leaves and Its Microencapsulation

Habanero pepper leaves were dried in a stainless-steel tray dryer (HS60-AID model, Tlaquepaque, México) at 44 °C for 48 h until a residual moisture content below 5% was achieved. The dried material was subsequently milled and sieved to a particle size of 500 µm, and then stored in airtight, foil-lined bags until use. Polyphenol-rich leaf extracts (PLRE) were obtained using a NADES composed of choline chloride and glucose (1:0.8 mol/mol) with 68% (w/w) added water. This NADES composition and the extraction conditions corresponded to the optimal parameters previously established for choline chloride–based systems (Avilés-Betanzos et al., 2023) [17].

For extraction, 1 g of dried leaf powder was mixed with 10 mL of NADES, vortex-mixed, and subjected to ultrasound-assisted extraction using a sonotrode (CV 505 model, Newtown, CT, USA) for 5 min at 30% amplitude. The resulting extract was centrifuged at 3700× g for 30 min at 4 °C and subsequently filtered through a 0.2 µm membrane prior to analysis [18].

The obtained PLRE was microencapsulated using a novel spray-drying-based approach. A feed solution containing PLRE (1.25%, v/v), maltodextrin (1.87%, m/v), guar gum (0.15–0.41%, m/v), and modified starch (1.27–1.72%, m/v) was prepared and introduced into a spray dryer (MOBILE MINOR™ GEA®, Model MM Standard, Düsseldorf, Germany) at a flow rate of 10 mL/min using a peristaltic pump (WATSON MARLOW®, Model 520S, Düsseldorf, Germany). Atomization was carried out using compressed air at a pressure of 3.5 bar, corresponding to a rotary atomizer speed of 22,000 rpm, with a constant hot air flow of 80 kg/h. The resulting microcapsules were collected in 1 L specialized GEA® bottles, stored at ambient temperature (30 °C), and protected from light using aluminum foil until further analysis [18].

The conditions used for the microencapsulation process were obtained from an optimization study previously reported by [19], in which a 22 central composite design (CCD) with four central points and four axial points was employed, applying the Response Surface Methodology (RSM). The independent variables evaluated were the inlet temperature (°C), 80 °C (Low level), 90 °C (Central point), 100 °C (High level), 76 °C (low level axial point), 104 °C (high level axial point), the Guar gum concentration (%), 5% (Low level), 7.5% (Central point), 10% (High level), 4% (Low level axial point) and 11% (High level axial point).

2.3. Raman Spectroscopic Analysis of Microencapsulated Habanero Pepper Leaf Extracts

The structural features of the microcapsules, including the individual wall materials and the habanero pepper leaf extract, were examined using Raman spectroscopy. Spectral acquisition was performed using a Renishaw InVia Reflex Raman spectrometer (Wotton-under-Edge, Gloucestershire, UK), covering a wavenumber range from 3200 to 200 cm−1. A 633 nm laser served as the excitation source and was operated at 50% of its maximum output power, in combination with a 50× objective lens and an exposure time of 10 ms. Raman spectra were collected for each encapsulating agent and for selected microencapsulated powders corresponding to the highest and lowest TPC observed during the spray-drying optimization stage [20].

2.4. In Vitro Digestion of the Habanero Pepper Extract Microencapsulated

The in vitro digestion procedure was carried out according to the method reported by [21], with slight modifications. The simulation of the gastric and intestinal digestion was performed as follows:

(a) Gastric phase: The pH was first adjusted and stabilized to 2–2.5 using HCl (5 M), and the temperature of the distilled water was maintained at 37 °C. Subsequently, in vitro digestion was carried out for both the microencapsulated and non-microencapsulated extracts (NADES-68), using 1 g of the microencapsulated habanero pepper leaf extract and 10 g of the non-microencapsulated habanero pepper leaf extract. Was added and kept under constant agitation (150 rpm) for 5 min, to proceed with the addition of pepsin (0.33 mg). The mixture was kept under continuous stirring for 2 h, and (b) Intestinal phase: The pH was adjusted and stabilized to 5–5.5 using NaOH (3 M). Then, pancreatin (0.19 g, CREON®, North Chicago, IL, USA), lipase (1 mg), and bile salts (1 g, Difco®, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) were added, and the mixture was incubated for 4 h at 37 °C under constant agitation (150 rpm). Samples (in triplicate) were collected at the end of each digestion phase for all powder formulations (14 treatments).

The bioaccessibility of total polyphenols during in vitro digestion was determined according to the method reported by [22], using Equation (1) to calculate the bioaccessibility index during the gastric phase (%BIG) and Equation (2) for the bioaccessibility index during the intestinal phase (%BII):

where $${\mathrm{T}\mathrm{P}\mathrm{C}}_{bf}$$ represents the total polyphenol content before the digestion process, while $${\mathrm{T}\mathrm{P}\mathrm{C}}_{Ga}$$ and $${\mathrm{T}\mathrm{P}\mathrm{C}}_{In}$$ correspond to the total polyphenol content at the end of the in vitro digestion during the gastric and intestinal phases, respectively. An increase in bioaccessibility was represented as a positive percentage, whereas a loss in bioaccessibility was represented as a negative percentage.

2.5. Determination of Total Polyphenol Content in Microencapsulated and In Vitro Digested Microencapsulated Extracts of Habanero Pepper Leaves

TPC was quantified according to the methodology reported by [23], with minor adaptations. For sample preparation, 0.5 g of the microencapsulated powder was suspended in 2.5 mL of distilled water and centrifuged at 3700× g for 20 min at 4 °C. The resulting supernatant was subsequently collected and filtered through a 0.22 µm nylon membrane prior to analysis. From the obtained extract, 25 µL were taken and added to 3025 µL of distilled water along with 250 µL of Folin–Ciocalteu reagent, allowing the mixture to stand for 5 min. Subsequently, 750 µL of sodium carbonate solution was added, followed by 950 µL of distilled water. The mixture was then incubated for 30 min. The absorbance was measured at 765 nm using a UV–Vis spectrophotometer (JENWAY® model 6715, Ultraviolet–visible light, Vernon Hills, IL, USA). The resulting absorbance was used to calculate the TPC, expressed as milligrams of gallic acid equivalents (mg GAE) per 100 g of powder.

For the determination of TPC in digested microencapsulated samples, the aliquots collected at the end of each digestion phase were centrifuged and filtered. Subsequently, 25 µL of each digested sample was taken, and the procedure described above was followed to obtain the absorbance at 765 nm.

Prior to experiment sample analysis, a calibration curve was prepared using gallic acid solutions ranging from 5 to 100 µg/mL. The calibration curve is shown in Figure S1, exhibiting an R2 value of 0.9986.

2.6. Evaluation of the Antioxidant Capacity of Microencapsulated Habanero Pepper Leaf Extracts Before and After In Vitro Digestion

The antioxidant capacity (Ax) of the microencapsulated, before and after in vitro digestion, was determined following the procedure described by [24]. For the determination of the Ax of the microencapsulated powders, 100 µL of the extract obtained after the extraction process (Section 2.5) was mixed with 3.9 mL of DPPH solution, previously adjusted to an absorbance of 0.700 ± 0.002 at a wavelength of 515 nm using a UV–Vis spectrophotometer.

The Ax of the digested microencapsulated samples was evaluated by combining 100 µL of each digestion fraction (gastric and intestinal) with the adjusted DPPH solution (DPPHad), following the procedure described above. Absorbance readings (SPabs) obtained for the habanero pepper leaf extract microcapsules, both prior to and after in vitro gastrointestinal digestion, were subsequently used to determine the percentage of radical scavenging activity according to Equation (3).

2.7. Response Surface Methodology Applied to the Bioaccessibility of Total Microencapsulated Polyphenol Content During In Vitro Digestion

The optimization of the bioaccessibility of TPC during in vitro digestion was carried out using a Response Surface Methodology (RSM) based on a 22 central composite design (CCD) with four central points and four axial (Table 1). The independent variables evaluated were those previously described in Section 2.2, while the response variable corresponded to the intestinal phase bioaccessibility of total polyphenols (%BII).

Each experimental run was conducted under the same spray-drying conditions previously described (Section 2.2), using the optimized choline chloride–glucose NADES extract of C. chinense leaves as feed solution. The experimental matrix included 12 experiments coded according to Statgraphics Centurion XVII.II (Statgraphics Technologies Inc., Warrenton, VA, USA).

The quadratic polynomial model used to describe the relationship between independent and dependent variables was:

| ```latexY={\beta }_{0}+{\beta }_{1}{X}_{1}+{\beta }_{2}{X}_{2}+{\beta }_{11}{X}_{1}^{2}+{\beta }_{22}{X}_{2}^{2}+{\beta }_{12}{X}_{1}{X}_{2}``` |

where $$Y$$ represents the bioaccessibility response (%BII), $${X}_{1}$$ the inlet temperature, $${X}_{2}$$ the Guar gum concentration, and the coefficients $${\beta }_{0},{\beta }_{1},{\beta }_{2},{\beta }_{11},{\beta }_{22},{\beta }_{12}$$ correspond to the intercept, linear, quadratic, and interaction effects, respectively.

2.8. Statistical Analysis

All microencapsulated samples were analyzed in triplicate both prior to and following in vitro gastrointestinal digestion to assess TPC and antioxidant activity Ax, by the DPPH method. The experimental results are expressed as mean values accompanied by their corresponding standard deviations. Inferential statistical analyses, including analysis of variance (ANOVA), multiple comparison procedures, and response surface methodology (RSM), were conducted using Statgraphics Centurion XVII.II X64 software, Version 16.1.03 (Statgraphics Technologies Inc., Warrenton, VA, USA).

Table 1. Central composite experimental design for optimizing microencapsulation conditions to obtain a microencapsulated product with high intestinal bioaccessibility of its total polyphenol content.

|

# Exp |

Encoded Values |

Real Values |

Bioaccessibility (%) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

X1 |

X2 |

GG (%) |

IT (°C) |

||

|

1 |

−1 |

−1 |

5 |

80 |

Y1,1 |

|

2 |

1 |

−1 |

10 |

80 |

Y1,2 |

|

3 |

−1 |

1 |

5 |

100 |

Y1,3 |

|

4 |

1 |

1 |

10 |

100 |

Y1,4 |

|

5 |

0 |

0 |

7.5 |

90 |

Y1,5 |

|

6 |

0 |

0 |

7.5 |

90 |

Y1,6 |

|

7 |

0 |

0 |

7.5 |

90 |

Y1,7 |

|

8 |

0 |

0 |

7.5 |

90 |

Y1,8 |

|

9 |

−$$\sqrt{2}$$ |

0 |

4 |

90 |

Y1,9 |

|

10 |

```latex\sqrt{2}``` |

0 |

11 |

90 |

Y1,10 |

|

11 |

0 |

−$$\sqrt{2}$$ |

7.5 |

76 |

Y1,11 |

|

12 |

0 |

```latex\sqrt{2}``` |

7.5 |

104 |

Y1,12 |

Note: Exp = Experiment; GG = Guar gum; IT = Inlet Temperature.

3. Results

3.1. Raman Spectroscopy of Habanero Pepper Extract Microencapsulated Before In Vitro Digestion

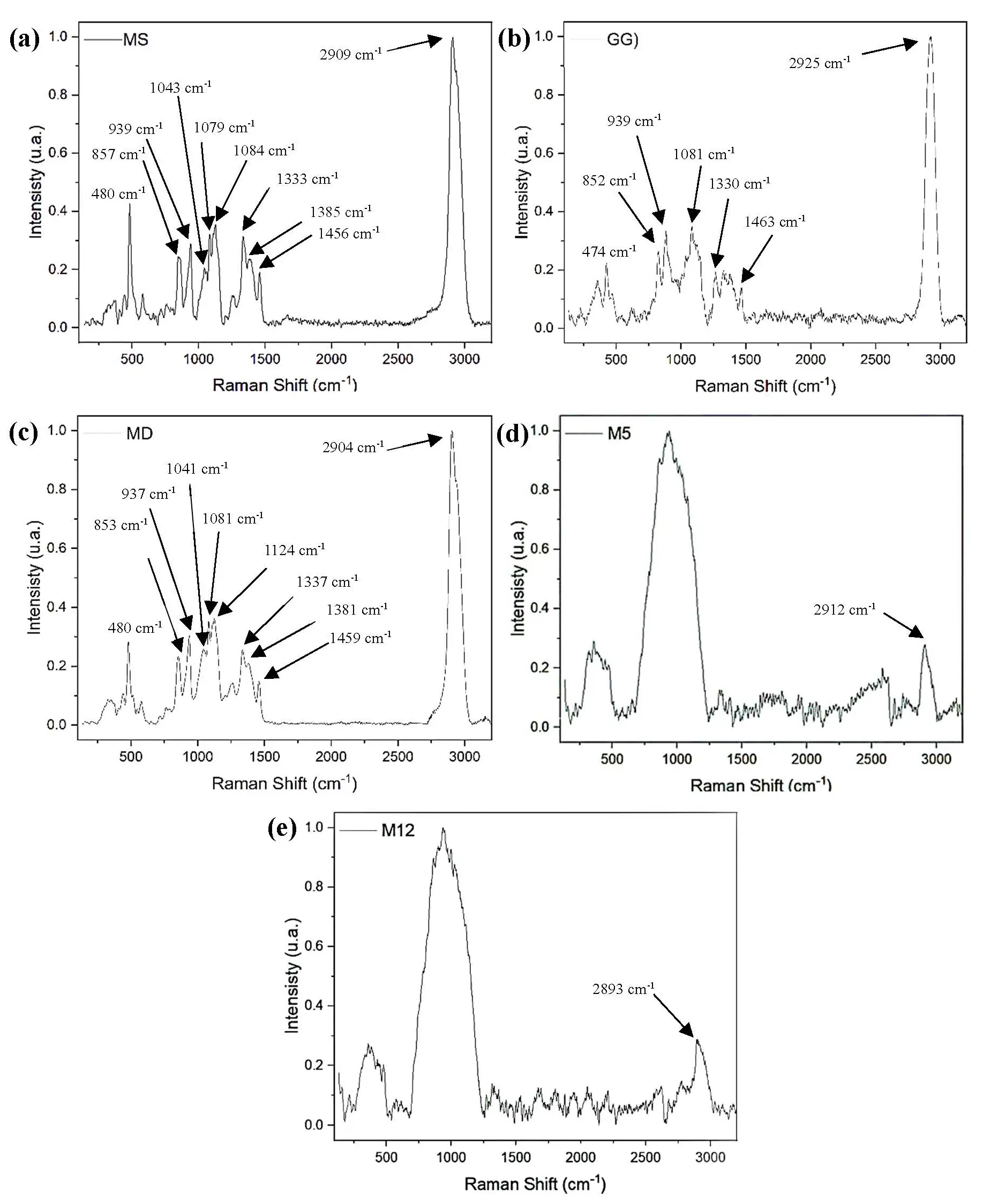

In the spectrum of modified starch (Figure 1a) and maltodextrin (Figure 1c), a peak at 480 cm−1 was observed, corresponding to cyclic structures and α-glucose rings associated with C–O–C and C–C–O linkages, respectively. Vibrations related to β-glycosidic bonds were also detected in modified starch (857 and 939 cm−1) and maltodextrin (853 and 937 cm−1) [25]. The region between 1000 and 1200 cm−1 was assigned to glycosidic linkages associated with deformation and stretching of CO, CC, and C–O–C bonds in the glucose backbone. In the starch sample (Figure 1a), peaks were observed at 1043, 1079, and 1084 cm−1, whereas for maltodextrin (Figure 1c), the corresponding peaks appeared at 1041, 1081, and 1124 cm−1. A band at 1333 cm−1 was attributed to CH2 and C–OH deformations.

Additionally, peaks at 1381 cm−1 in maltodextrin and 1385 cm−1 in modified starch were assigned to CH and COH bond vibrations [26]. A CH2 deformation band was also observed at 1456 cm−1 for starch and 1459 cm−1 for maltodextrin, characteristic of complex carbohydrates. Finally, a peak at 2909 cm−1 in modified starch was associated with the stretching of C–H bonds in methyl (CH3) and methylene (CH2) groups of glucose [27]. This peak was likewise present in the maltodextrin spectrum (2904 cm−1, Figure 1c) and with lower intensity in the microencapsulates M5 or experiment 5 (2912 cm−1, Figure 1d) and M12 or experiment 12 (2893 cm−1, Figure 1e). Also, the microencapsulated samples (M5, M12) showed a very intense and broad band between 800 and 1200 cm−1, attributed to C–O and C–O–C vibrations of glycosidic linkages in the polysaccharide matrix. The broadening of this region compared with the individual encapsulating agents indicates the overlapping contributions of Guar gum, maltodextrin, and modified starch, as well as their interaction with the extract, a phenomenon reported in microencapsulated systems where the stabilizing agent bands dominate over those of the bioactive core [28,29].

Figure 1. Raman spectra of (a) Modified starch (MS); (b) Guar gum (GG); (c) Maltodextrin (MD); (d) Microencapsulate 5 (M5, 7.5% Guar gum, 104 °C); (e) Microencapsulate 12 (M12, 7.5% Guar gum, 76 °C).

3.2. Changes in Total Polyphenol Content and Antioxidant Capacity During Simulated Digestion

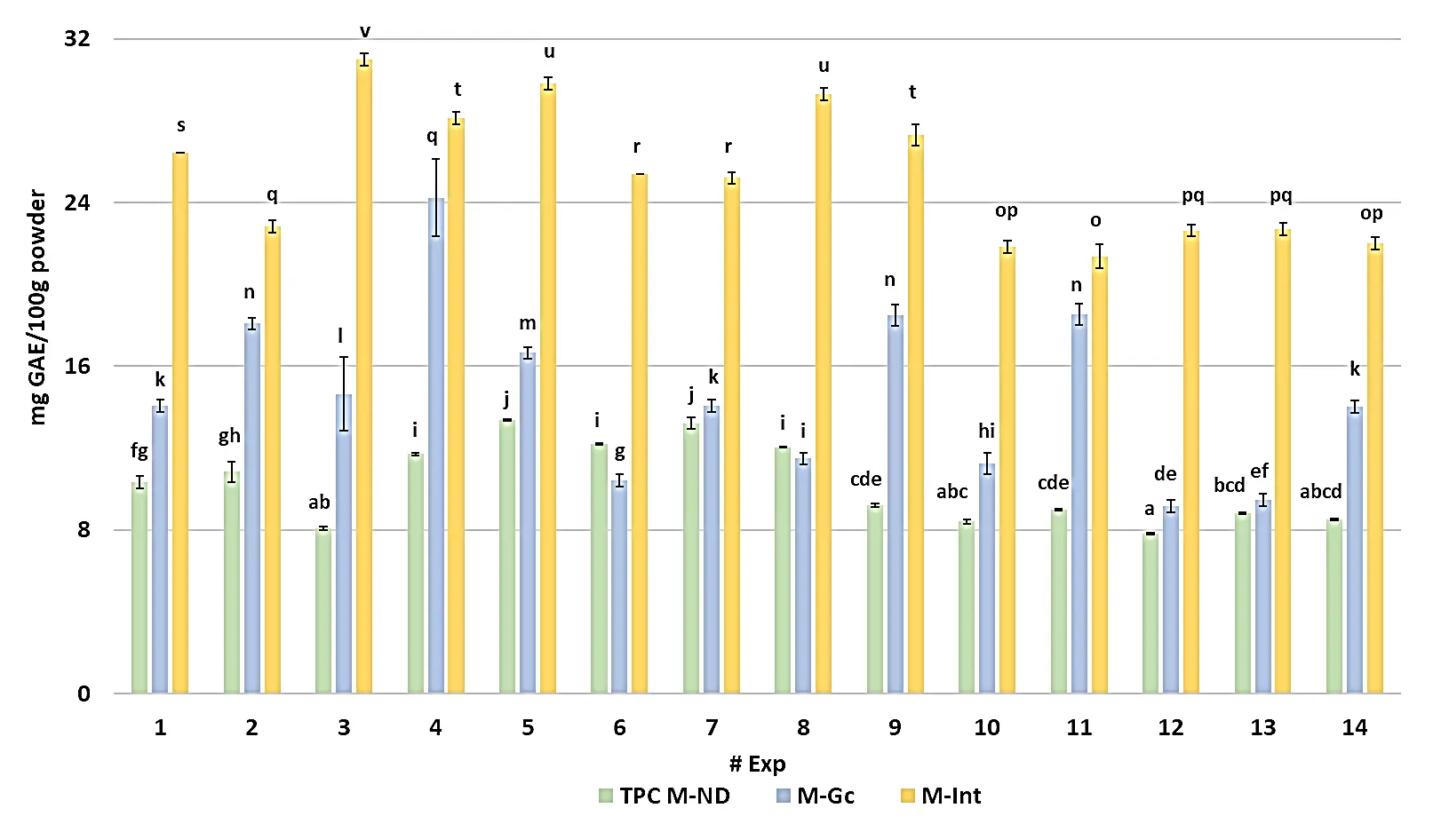

TPC of the microencapsulated C. chinense leaf extracts before digestion (M-BD) varied between 7.80 ± 0.04 mg GAE/100 g powder in experiment 12 (7.5% GG, 104 °C) and 13.37 ± 0.04 mg GAE/100 g powder in experiment 5 (7.5% GG, 90 °C). In contrast, the reduced TPC detected in high-temperature or low-polymer formulations (e.g., experiment 12, 104 °C, 7.5% GG; experiment 13, 104 °C, 8.1% GG) suggests that excessive heat or weak polymer networks promoted the partial oxidation of phenolic compounds during spray drying. The TPC values observed in experiments 5–7 (13.2–13.4 mg GAE/100 g powder) were statistically different (p < 0.05) from the lowest values found in experiments 12, 13, and 10, indicating that the mid-range drying temperature (≈90 °C) and balanced Guar-gum ratio favored phenolic retention (Figure 2; Table S1).

During the gastric phase (M-Gc), TPC values displayed wide variability, from 9.17 ± 0.30 mg GAE/100 g powder in experiment 12 to 24.24 ± 1.87 mg GAE/100 g powder in experiment 4 (10% GG, 100 °C). The formulations showing the most pronounced release, experiments 3, 4, and 9, differed significantly from the rest (p < 0.05) and suggest that the acidic pH ≈ 2.5 and pepsin exposure enhanced the solubilization of bound phenolics through partial disintegration of the encapsulating walls. This phenomenon was especially evident in experiment 4, whose matrix (1.27% modified starch + 0.41% GG) likely promoted intermolecular rearrangements between amylose and galactomannans, facilitating controlled release. Conversely, experiments 12–14 (7.8–8.1% GG, 89–104 °C) retained significantly lower TPCs (superscripts a–d), suggesting that high thermal input and maltodextrin-dominant matrices produced more resistant encapsulation structures that restricted diffusion under gastric stress.

A marked increase in polyphenol concentration occurred during the intestinal phase (M-Int), where TPC values ranged between 21.37 ± 0.60 mg GAE/100 g powder (experiment 11; 7.5% GG, 76 °C) and 31.00 ± 0.30 mg GAE/100 g powder (experiment 3; 5% GG, 100 °C). Experiments 3–5 (superscripts t–v) showed the highest TPCs (p < 0.05), indicating that moderate-to-high Guar-gum levels combined with controlled drying temperatures enhanced the liberation of phenolics under simulated intestinal conditions. The transition from the gastric to the intestinal phase resulted in a significant increase due to the action of digestive enzymes and bile salts at near-neutral pH, which disrupted the polysaccharide-based encapsulating wall and enabled the release of entrapped phenolic compounds. Particularly, experiment 3, which rose from 14.65 ± 1.80 mg GAE/100 g powder (M-Gc) to 31.00 ± 0.30 mg GAE/100 g powder (M-Int), a 112% relative increase, demonstrated a sustained-release profile consistent with gradual matrix erosion rather than abrupt diffusion.

Figure 2. Total polyphenol content of the microencapsulated habanero pepper leaf extract during in vitro digestion. GAE = Gallic acid equivalent; Exp = Number of experiment; M-ND = Microencapsulated before digestion; M-Gc = Microencapsulated during gastric phase; M-Int = Microencapsulated during intestinal phase; Different letters indicate significant differences (LSD, p < 0.05).

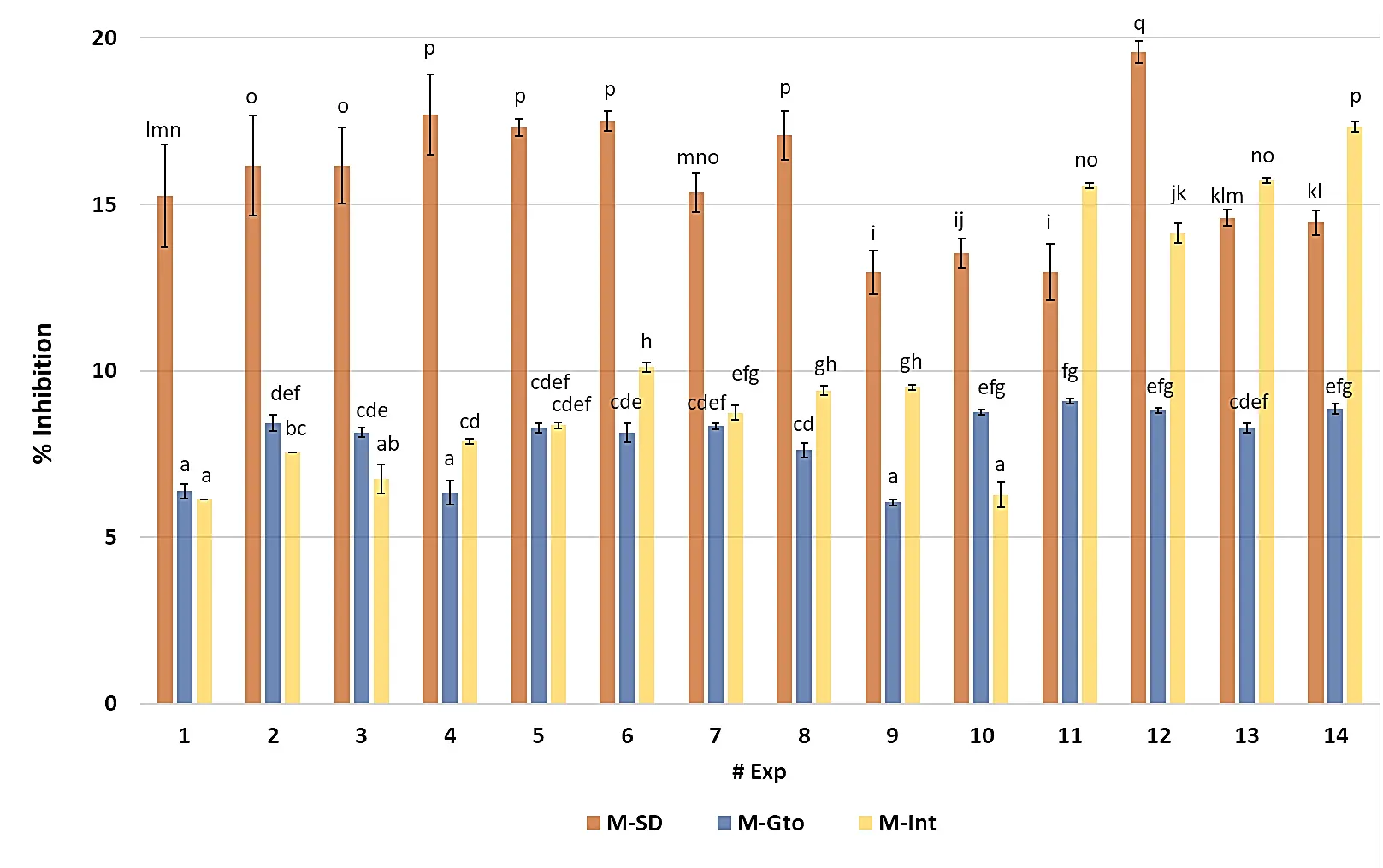

The antioxidant response of the microencapsulated C. chinense leaf extracts, expressed as the percentage of DPPH radical inhibition, revealed marked differences among treatments and digestion stages (Figure 3; Table S2). Before in vitro digestion (M-ND), inhibition values ranged from 12.96 ± 0.65% to 19.56 ± 0.33%, with the highest activity observed in experiment 12 (7.5% GG, 104 °C). This formulation exhibited significantly greater scavenging capacity than most others (p < 0.05), suggesting that the combination of moderate Guar-gum content and a high inlet temperature favored the stabilization of phenolic antioxidants during spray drying through rapid glass-film formation and enhanced polymer–phenolic bonding. Conversely, experiments 9 and 11, produced under milder drying conditions (≤90 °C) and lower GG content, showed the weakest performance, implying incomplete encapsulation and higher oxidative degradation, while experiments 4–6, maintain inhibition levels around 17%, and were statistically grouped with the best performers (p < 0.05), confirming that optimized thermal and compositional parameters minimized phenolic losses during drying.

When exposed to gastric conditions (M-Gto), the Ax decreased in all experiments, ranging from 6.05 ± 0.08% to 9.10 ± 0.08%. The drop is expected due to an acidic pH (≈2.5) and pepsin activity, which can modify or protonate phenolic hydroxyls, reducing their radical-scavenging potential. Nevertheless, experiments 10, 11, 12, and 14 (7.8% GG, 89.4 °C, optimal conditions for TCP or OpCTP) retained significantly higher inhibition values (8.7–9.1%), likely due to partial matrix erosion that released phenolics stable under low pH. In contrast, experiments 1, 4, and 9 demonstrated limited release during this phase.

Figure 3. Antioxidant capacity of the microencapsulated habanero pepper leaf extract during in vitro digestion. Exp = Number of experiment; M-SD = Microencapsulated before digestion; M-Gto = Microencapsulated during gastric phase; M-Int = Microencapsulated during intestinal phase; Different letters indicate significant differences (LSD, p < 0.05).

During the intestinal phase (M-Int), the Ax increased markedly across most treatments, ranging from 6.13 ± 0.00% to 17.34 ± 0.14%, reflecting the same trend observed for total polyphenols. The enzymatic mixture of pancreatin, lipase, and bile salts, acting under near-neutral conditions, facilitated the hydrolysis of polysaccharidic walls and the liberation of bound antioxidant species. The best responses were recorded for experiments 11–14, particularly experiment 14 (7.8% GG, 89.4 °C, OpCTP), which reached the maximum inhibition (17.34 ± 0.14%). These results indicate that matrices containing balanced Guar-gum concentrations (7–8%) and processed at moderate-to-high inlet temperatures promote a delayed yet efficient release of antioxidant molecules during the intestinal phase.

In Table S2, the antioxidant capacity results of the non-microencapsulated NADES-68 extract are presented. It can be observed that the inhibition percentage prior to digestion is considerably higher than that of the microencapsulated samples (p < 0.05); however, after undergoing the in vitro digestion process, the antioxidant capacity drops below 50%. Notably, during the gastric phase, the antioxidant capacity of the extract does not differ statistically (p > 0.05) from that of the microencapsulated extract obtained in experiment 12 (7.5% GG, 104 °C, OpCTP). Subsequently, it approaches the values obtained for the microencapsulated samples at the end of the intestinal phase (28.15 ± 0.70%).

3.3. Total Polyphenol Content Bioaccessibility During In Vitro Digestion

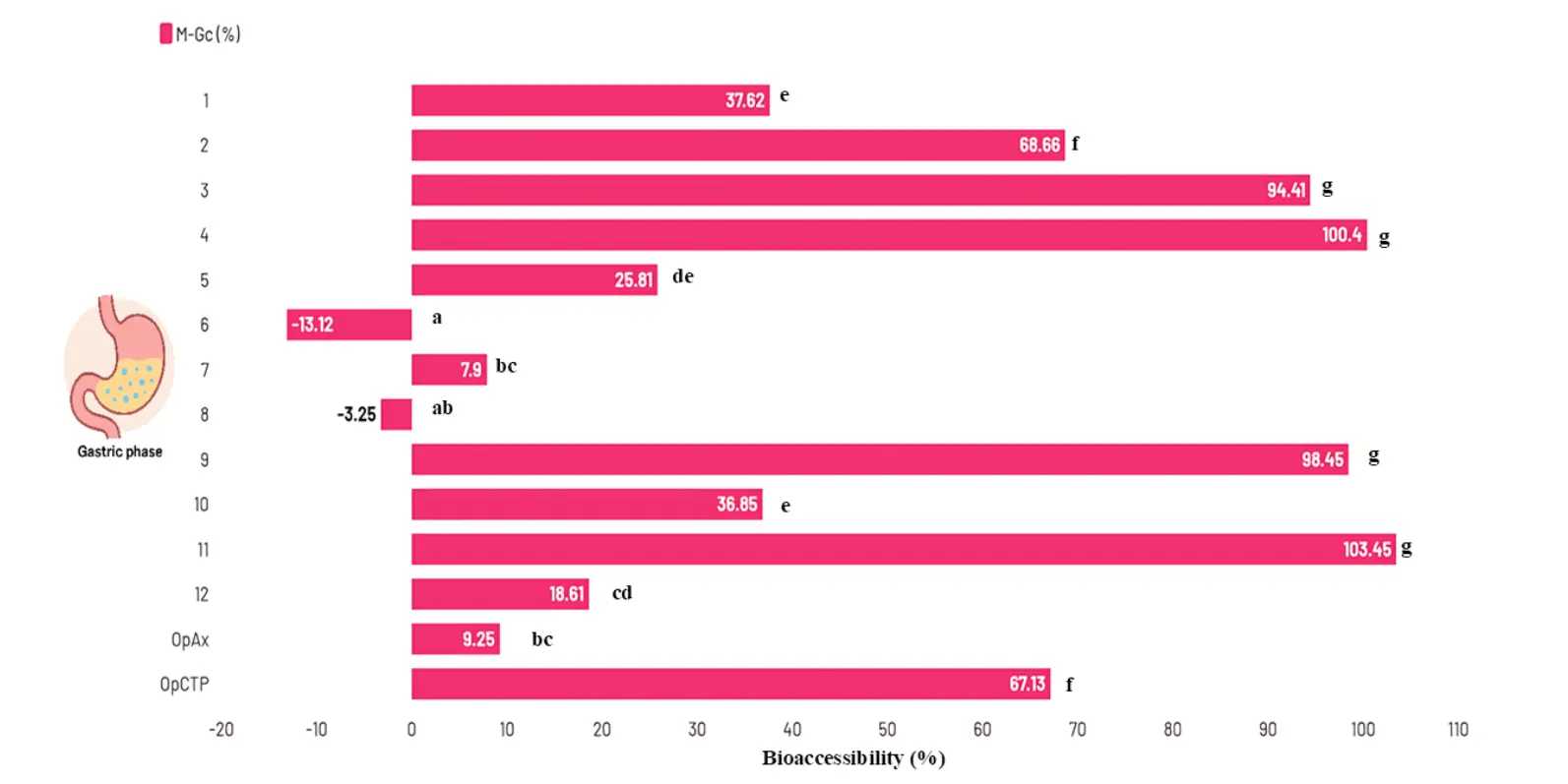

As shown in Figure 4 and Table S3, the bioaccessibility of TPC during the gastric phase (M-Gc) ranged from −13.12 ± 1.74% to 103.45 ± 5.46%. Experiment 11 (7.5% GG, 76 °C) exhibited the highest response, reaching a value of 103.45 ± 5.46%, and was followed by experiments 4 (10% GG, 100 °C) and 9 (4% GG, 90 °C). These treatments did not show significant differences among them and were classified within the same statistical group (p < 0.05). Conversely, experiment 6 (7.5% GG, 90 °C) showed the lowest bioaccessibility (–13.12 ± 1.74%), displaying a statistically significant difference (p < 0.05) when compared with all other experimental conditions. An additional observation of interest was that experiments 3 and 4, both dried at 100 °C, showed bioaccessibility values above 90%, suggesting that higher inlet temperatures favored the release of polyphenols during the gastric phase.

Figure 4. Bioaccessibility of total polyphenol content during the gastric phase of in vitro digestion. M-Gc = Microencapsulated during the gastric phase; OpAx = Optimal spraydryin conditions for high antioxidant capacity microencapsulated; OpCTP = Optimal spraydryin conditions for high total polyphenol content microencapsulated. Different letters on the bars indicate statistically significant differences (p < 0.05, LSD).

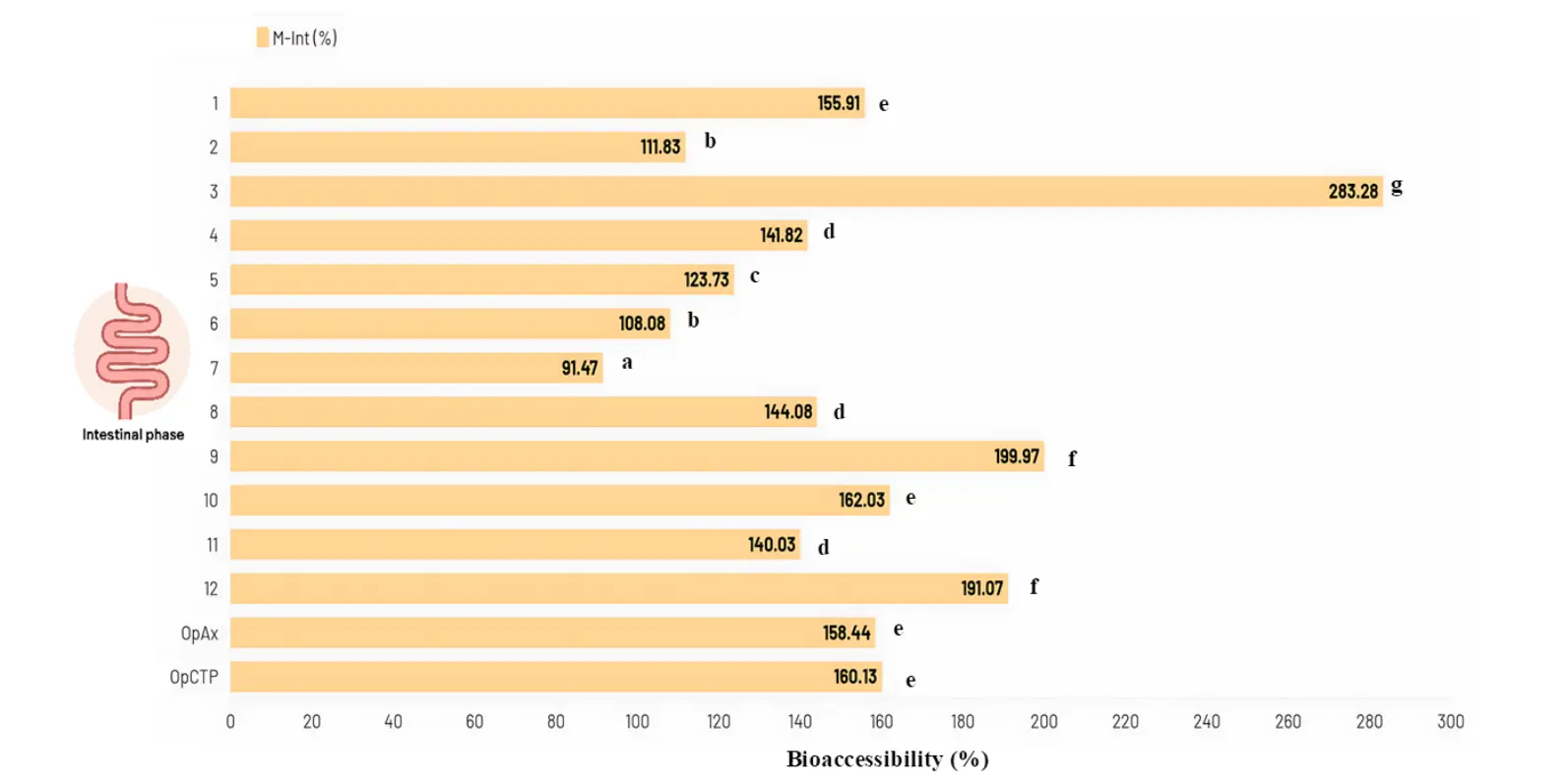

Among all formulations, experiment 3 (5% GG, 100 °C) achieved the greatest intestinal bioaccessibility, reaching 283.28 ± 3.22%, which was significantly higher than the remaining treatments (p < 0.05, group G). The lowest recovery of polyphenols was observed in experiment 7 (7.5% GG, 90 °C) with 91.47 ± 1.98% (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Bioaccessibility of total polyphenol content during the intestinal phase of in vitro digestion. M-Int = Microencapsulated during intestinal phase; OpAx = Optimal spraydryin conditions for high Ax microencapsulated; OpCTP = Optimal spraydryin conditions for high total polyphenol content microencapsulated. Different letters on the bars indicate statistically significant differences (p < 0.05, LSD).

Moderate bioaccessibility responses were observed in experiments 9 (4% GG, 90 °C) and 12 (7.5% GG, 104 °C), with both treatments yielding values above 190% and showing no statistically significant differences between them (p > 0.05). Overall, despite the dispersion among experimental conditions, the majority of the microencapsulated samples exhibited bioaccessibility values higher than 100%, indicating efficient release of phenolic compounds during the intestinal phase and a strong solubilization capacity following enzymatic digestion. Finally, the bioaccessibility results of the non-microencapsulated NADES-68 extract showed a substantial loss in both digestive phases. For example, gastric-phase bioaccessibility was −85.46 ± 0.31%, slightly lower than the intestinal phase, which reached −80.19 ± 0.63% (Table S3). These values support the decision to microencapsulate the extract using encapsulating agents that can protect phenolic compounds and preserve their bioactive properties.

3.4. Optimization of Polyphenol Bioaccessibility During In Vitro Digestion of Microencapsulated Habanero Pepper Leaf Extract

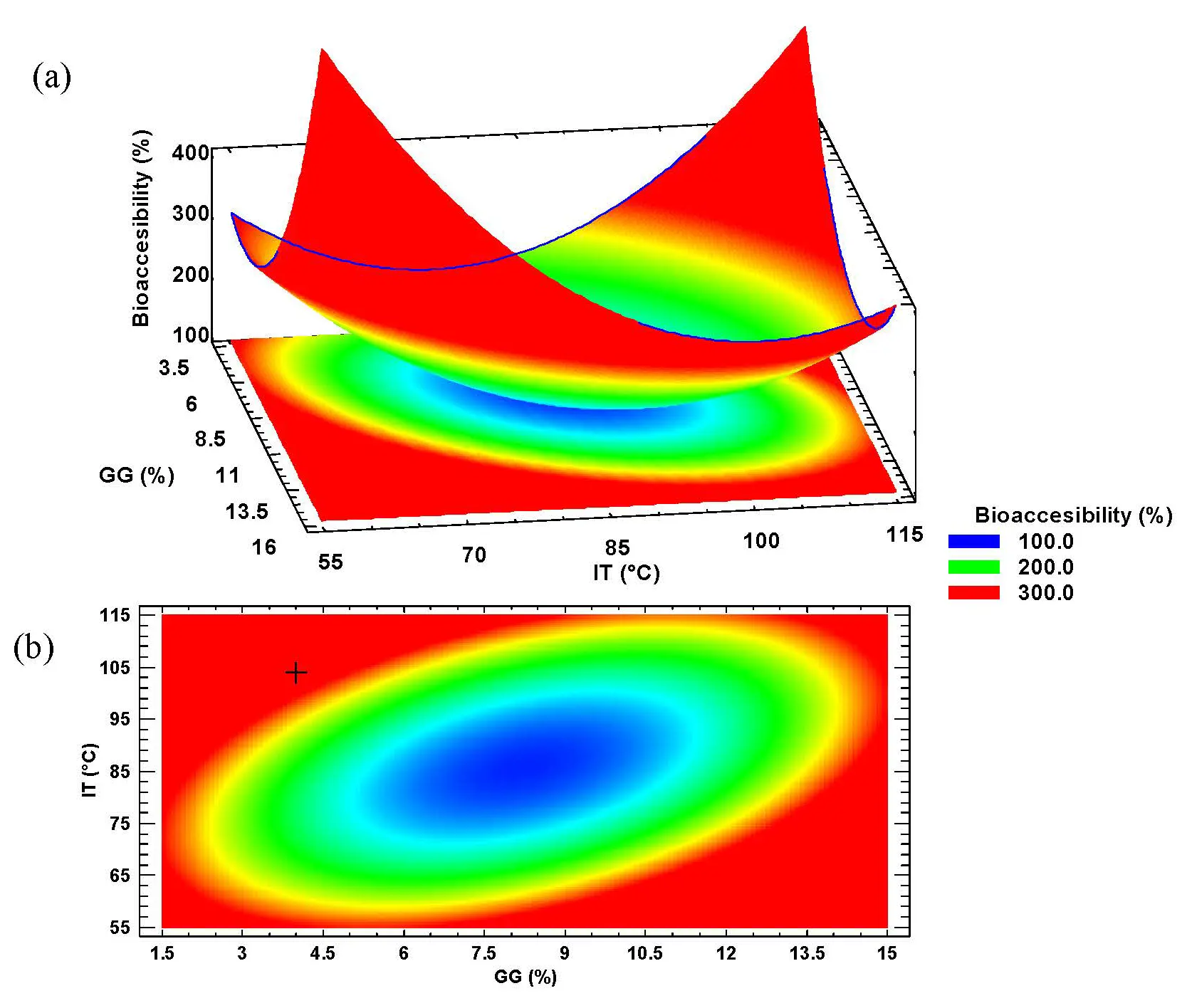

Analyzing all the intestinal phase bioaccessibility data obtained from the complete design for optimization (12 experiments) according to the response surface methodology, a canonical analysis was performed, showing a good fit to a second-order model (p < 0.0001, R2 = 83.74). The canonical analysis provided the optimal value and spray-drying conditions required to achieve the maximum bioaccessibility of the TPC from the microencapsulated habanero pepper leaf extracts (Table 2).

Table 2. Results of the canonical analysis of the bioaccessibility of the total polyphenol content from the microencapsulated habanero pepper leaf extract.

|

Variable Response |

Prediction Equation * |

Optimal Spray Drying Conditions |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

GG (%) |

IT (°C) |

Optimal Value ** (%) |

||

|

TPC |

TPCBi = 1569.03 − 2.20769X1 − 33.9713X2 − 0.973867X1X2 + 5.18682X12 + 0.245358X22 |

4 |

104 |

358.3 |

Note: TPC = Total polyphenol content; TPCBi = Total polyphenol content bioaccessibility; GG = Guar gum; IT = Inlet temperature; X1 = Guar gum; X2 = Inlet temperature; * Obtained by using the coefficients regression (Table S4); ** Predicted according to canonical analysis with the statistical software.

In Figure 6a, the characterization of the response surface for the intestinal phase bioaccessibility of TPC data is shown. The surface corresponds to a plateau of minimum values, where the red area indicates the intersection of the spray-drying conditions that result in the maximum bioaccessibility of the microencapsulated phenolic compounds, while the blue area (center of the surface) represents the region where minimal bioaccessibility is obtained.

Figure 6. Characterization of (a) Response surface and (b) Contour plot of the intestinal bioaccessibility of total polyphenol content from the microencapsulated habanero pepper leaf extract. GG = Guar gum; IT = Inlet temperature.

The contour plot (Figure 6b) displays, with the “+” symbol, the location of the optimal value predicted by the statistical software (the intersection of the optimal spray-drying conditions) according to the canonical analysis.

It was also observed that all the main factors, Guar gum percentage (A, p < 0.0001), inlet temperature (B, p < 0.0001), their interaction (A × B, p = 0.0006), and their quadratic effects (A2, p < 0.0001; B2, p < 0.0001), showed a significant effect on intestinal phase bioaccessibility of the microencapsulated phenolic compounds (Table S5).

4. Discussion

The Raman spectra of the microencapsulated experiments M5 and M12 exhibited markedly broader bands in the regions of 250–500 cm−1 and 750–1250 cm−1, corresponding to the vibrations of α- and β-glycosidic bonds, respectively. These spectral modifications likely reflect molecular interactions among the different encapsulating agents and the phenolic compounds present in the Habanero pepper leaf extract, which contains choline chloride and glucose as major constituents [29]. A notable decrease in band intensity was also observed in the 1250–1500 cm−1 region, associated with C–H stretching vibrations. This reduction may arise from restricted vibrational independence due to intermolecular forces and hydrogen bonding within the matrix, consistent with previous findings on polymer–polyphenol interactions [30,31].

In contrast, the Raman profile of Guar gum (GG) revealed peaks located at wavenumbers comparable to those found in maltodextrin and modified starch, though with noticeably lower intensities. Such differences are attributed to the distinct molecular configuration of GG relative to these polysaccharides. The band near 474 cm−1, typically assigned to α-glycosidic linkages, appeared weaker in GG since its structure is mainly composed of β-glycosidic bonds, which alter its vibrational behavior. Meanwhile, the region spanning 1000–1200 cm−1—characteristic of β-glycosidic vibrations—showed spectral similarity across all encapsulating agents, supporting the presence of a shared carbohydrate backbone [25,32].

Furthermore, attenuated peaks at 1330 cm−1 and 1463 cm−1 were detected, linked to CH2 and C–OH bond vibrations, respectively. These attenuations suggest a lower degree of branching in GG compared with maltodextrin and modified starch, which exhibit more complex, branched architectures. Finally, the peak near 2925 cm−1, characteristic of CH2 stretching, was present in all encapsulating materials and the microencapsulates, confirming the retention of carbohydrate functional groups after spray-drying [33].

The higher total polyphenol retention observed in experiments 5–7, formulated with 7.5% Guar gum (GG) and processed at ≈90 °C, is attributable to the balance between encapsulant glass transition behavior and phenolic stability. At this temperature range, the feed mixture remains above the critical glass transition (Tg) of the maltodextrin–gum system yet below the threshold for phenolic oxidation. Under these conditions, rapid surface vitrification occurs, forming an amorphous matrix that limits oxygen diffusion and light penetration, thereby preventing degradation of thermolabile polyphenols [34].

In contrast, the samples dried at 104 °C (e.g., M12, M13) were likely exposed to excessive thermal energy, which promoted early Maillard reactions and phenolic polymerization, resulting in a reduction in measurable TPC. This effect aligns with previous studies, which report that increased inlet temperatures intensify Maillard product formation and decrease phenolic quantification. For example, in camelina meal extracts, the TPC of the liquid extract (5.73 ± 0.26 mg GAE/mL) decreased to 2.30–2.86 mg GAE/mL after spray drying at 140–180 °C, associated by an increase in melanoidin absorbance (Abs 360 nm/Abs 420 nm), indicating temperature-dependent degradation and interference in Folin–Ciocalteu assays [35]. Similarly, in spray-dried honey, conventional drying at 180 °C retained only 41–59% of phenolics, compared with 80–91% when using dehumidified air at 75 °C, confirming that higher thermal loads lead to lower polyphenol recovery [36].

The chemical structure of Guar gum, composed of β-(1→4)-linked mannose and α-(1→6)-linked galactose residues, facilitates the formation of extensive hydrogen-bonding networks with the hydroxyl groups of polyphenolic compounds, thereby improving the stability of encapsulated bioactives through non-covalent interactions and the development of a cohesive and viscous matrix during atomization [32,37,38]. When combined with maltodextrin, the galactomannan chains of Guar gum act synergistically to enhance film formation and reduce matrix porosity, limiting volatilization and molecular coalescence of phenolics at the droplet interface. This synergistic effect has been correlated with higher encapsulation efficiencies, typically ranging between 78–90% in maltodextrin–gum systems, compared with <70% when maltodextrin is used alone [39,40,41].

In a similar way, ref [12] reported that the incorporation of gum arabic with maltodextrin in tamarillo (Solanum betaceum) microcapsules increased total polyphenol retention from 63.2 to 86.5%, while [42] observed a comparable improvement (from 68.4% to 88.9%) in Citrus medica extracts. Likewise, the encapsulation of Buddleja scordioides polyphenols under optimized spray-drying conditions (inlet temperature ≈ 100 °C, gum concentration 7–10%) achieved TPC values between 12.5 and 15.4 mg GAE/g dry powder, confirming that mixed carbohydrate matrices enhance phenolic retention and oxidative stability during atomization [13]. These findings support the hypothesis that the combination of maltodextrin and Guar gum generates an amorphous, low-porosity barrier capable of maintaining phenolic integrity, consistent with the high pre-digestion TPC observed in samples from experiments 5–7 of the present study.

With respect to Ax, the microencapsulated C. chinense leaf extracts demonstrated the interactive influence of wall material composition and spray-drying temperature on both the structural stability of the microcapsules and the release dynamics of phenolic compounds during simulated gastrointestinal digestion. The highest inhibition prior to digestion was obtained for experiment 12 (7.5% GG, 104 °C), followed by treatments produced between 90–100 °C with intermediate gum concentrations. Such performance indicates that the formation of a glassy and compact maltodextrin–Guar-gum matrix at high inlet temperatures efficiently restricted oxygen diffusion and phenolic oxidation, as previously observed in plum and tamarillo microcapsules, where elevated temperatures favored rapid surface solidification and antioxidant retention [12,14]. The structural densification likely enhanced hydrogen bonding between the hydroxyl groups of galactomannan and phenolic moieties, generating a stable amorphous network capable of entrapping radical-scavenging species [34,43]. Conversely, experiments processed at lower temperatures (≤90 °C) or with excessive polymer dilution exhibited lower inhibition values, suggesting incomplete film formation and increased exposure of phenolics to oxidative stress during atomization.

As digestion progressed, the gradual decrease in inhibition under gastric conditions can be attributed to the protonation of phenolic hydroxyls and partial degradation of labile compounds in the acidic medium. However, the microcapsules obtained with balanced gum levels (7–11%) maintained higher residual activity, indicating that the swelling and partial erosion of their walls facilitated the release of more acid-resistant phenolic species, a trend consistent with previous reports for oregano and berry polyphenols encapsulated in carbohydrate matrices [19]. The subsequent increase in inhibition during the intestinal phase reveals a clear relationship between matrix disintegration and antioxidant recovery: enzymatic hydrolysis of maltodextrin chains and solubilization of Guar gum exposed previously bound phenolics, restoring redox activity similarly to the delayed release observed in fruit-derived phenolic powders [11,14]. This behavior supports the concept that the controlled structural collapse of the wall material under neutral pH governs bioaccessibility rather than simple diffusion.

Overall, the antioxidant profile across digestion phases suggests that inlet temperatures near 100 °C and intermediate Guar gum concentrations optimize the dual role of the carrier system: protecting phenolics during drying and gastric transit, and facilitating effective release in the intestine. Similar temperature-dependent stabilization mechanisms have been reported for spray-dried pomegranate polyphenols, where moderate inlet temperatures (100–120 °C) favored rapid surface vitrification and higher retention of anthocyanins and total polyphenols [44,45]. These findings support that the maltodextrin–Guar gum system behaves as a dynamic barrier, initially protective, then responsive, facilitating controlled phenolic release and sustained Ax throughout digestion.

During digestion, these matrices undergo gradual disintegration, first limiting release in the acidic gastric phase and later promoting alkaline-driven swelling and enzymatic hydrolysis, which liberate bound phenolics and restore their redox activity [11]. Consequently, the increase in TPC and Ax observed in the intestinal phase reflects an improvement in phenolic bioaccessibility, where enzymatic cleavage of polysaccharidic bonds exposes previously trapped antioxidants.

The bioaccessibility of TPC during in vitro digestion showed pronounced variability, with gastric values ranging from −13.12 ± 1.74% to 103.45 ± 5.46% and intestinal values between 91.47 ± 1.98% and 283.28 ± 3.22%. These results demonstrate that the interaction between wall material composition and drying temperature critically governs polyphenol release under gastrointestinal conditions. In particular, the formulations dried at 100 °C and containing 5–10% Guar gum (GG) exhibited the highest gastric recovery (≈94–103%), consistent with efficient phenolic stabilization and subsequent pH-dependent release. Such trends align with those observed for plum (Prunus salicina) microcapsules produced using a maltodextrin:β-cyclodextrin: gum arabic ratio of 7:2:1 (w/w/w) at 110–150 °C, which retained up to 85% TPC and demonstrated controlled release during digestion [14].

Maltodextrin-based matrices processed at moderate inlet temperatures enhance polyphenol retention during spray drying. In pomegranate juice and extracts, maltodextrin at 100–120 °C improves anthocyanin and total polyphenol retention compared with protein carriers or higher temperatures, due to faster surface vitrification and reduced oxidative mobility [44,45]. Likewise, microencapsulation of olive by-product polyphenols with ~7% maltodextrin at 110 °C produced microcapsules with 50–78% intestinal bioaccessibility after in vitro digestion, demonstrating that moderate thermal regimes and carbohydrate matrices improve protection and controlled release of phenolics [46]. These findings support that, in our study, a vitreous matrix likely formed around 100 °C, acting as a semi-amorphous barrier that protected phenolics during atomization and gastric transit while promoting their solubilization, consistent with the high bioaccessibility observed in treatments 3, 4, and 11 [44,46]. Conversely, the negative gastric bioaccessibility observed in experiment 6 (−13.12 ± 1.74%) suggests potential oxidative degradation or incomplete desorption from a more cohesive wall structure. Lower thermal energy and excessive polymer crosslinking could hinder matrix swelling, delaying phenolic diffusion in acidic environments. This phenomenon has also been described in chokeberry anthocyanins encapsulated with inulin and Guar gum, where limited solubility reduced release in the gastric phase but improved intestinal liberation after enzymatic hydrolysis [47].

Finally, the pronounced increase in intestinal bioaccessibility (up to 283%) can be explained by the alkaline hydrolysis of glycosidic linkages and the enzymatic action of pancreatin and bile salts, which promote matrix erosion and phenolic release. Consistent patterns have been reported for spray-dried polyphenol microcapsules: in propolis microparticles, certain phenolics (e.g., p-coumaric acid) exhibited >100% recovery after in vitro digestion—indicative of enhanced solubilization and transformation in the intestinal phase [48].

The optimized conditions (4% Guar gum, 104 °C inlet temperature) and the predicted value (358.3% bioaccessibility) obtained from the response surface optimization suggest that a moderate thermal input and an adequate wall-material concentration favor the intestinal release of phenolic compounds rather than their mere retention. These optimized parameters are consistent with those reported for other spray-dried polyphenolic systems that achieved enhanced gastrointestinal bioaccessibility under controlled thermal loads.

For example, [49] optimized the spray-drying microencapsulation of polyphenols derived from cocoa pod husks using gum arabic (GA) at a 1:3 (w/w) ratio and an inlet temperature of 150 °C. Under these conditions, an intestinal bioaccessibility of 76.55 ± 5.10% was achieved, whereas the non-encapsulated extract exhibited a markedly lower value of only 6.41 ± 1.61%. Although the initial TPC of 90.48 mg GAE g−1 declined throughout the digestion process, a high proportion of the compounds remained bioaccessible due to the protective effect of the GA matrix. A similar reduction in bioaccessibility for non-encapsulated extracts was observed in the present study, reinforcing the importance of applying encapsulation strategies to safeguard bioactive compounds against the harsh conditions of the gastrointestinal environment. Although their process involves a higher drying temperature, the mechanism underlying the enhanced intestinal release parallels our findings: an appropriate biopolymer concentration combined with sufficient drying energy promotes the formation of a porous microstructure that facilitates rehydration and phenolic diffusion under intestinal conditions. In contrast, our lower inlet temperature (104 °C) demonstrates that excessive thermal exposure is unnecessary to achieve high release, supporting the principle that moderate drying preserves both molecular integrity and capsule porosity.

Similarly, [46] optimized the spray-drying of polyphenols recovered from red-wine lees using maltodextrin at 7% and 110 °C inlet temperature, obtaining total bioactive compound contents between 0.30 and 1.04 mg GAE 100 mg−1 dry weight and in-vitro polyphenol bioaccessibility ranging from 50% to 78% after simulated digestion. These conditions closely resemble our optimal parameters, reinforcing the notion that moderate inlet temperatures (100–110 °C) maximize bioaccessibility while minimizing phenolic degradation.

5. Conclusions

This study presents an innovative strategy for improving stability and modulating the release behavior of polyphenols derived from C. chinense leaves by combining NADES extraction with spray drying microencapsulation. The application of NADES enabled efficient and environmentally benign recovery of phenolic compounds, while also promoting specific molecular interactions with polysaccharide wall matrices. These interactions contributed to enhanced physicochemical functionality and overall performance of the resulting microencapsulated systems. The subsequent in vitro digestion demonstrated that the microcapsules effectively preserved and released bioactive compounds under simulated gastrointestinal conditions. The optimal formulation, achieved with 4% Guar gum (GG) and an inlet temperature (IT) of 104 °C, resulted in the highest total polyphenol bioaccessibility, reaching 358.3%. Overall, this study not only highlights the synergistic potential of NADES-assisted extraction and spray-drying encapsulation but also establishes a methodological framework for maximizing the bioaccessibility of plant-derived phenolics, contributing to the development of sustainable and functional ingredients from agro-industrial by-products.

Supplementary Materials

The supporting information associated with this article is available at https://www.sciepublish.com/article/pii/826: Figure S1: Calibration curve for the determination of total polyphenols in microencapsulated Capsicum chinense leaf extract experiments under in vitro digestion; Table S1: Total polyphenol content of microencapsulated Capsicum chinense extract experiments during in vitro digestion; Table S2: Antioxidant capacity of microencapsulated Capsicum chinense extract experiments during in vitro digestion; Table S3: Bioaccessibility results of total polyphenol content during in vitro digestion in the gastric and intestinal phases; Table S4: Regression Coefficients of the Response Surface for the Polyphenol Bioaccessibility during the Gastric Phase of Microencapsulated Habanero Pepper Leaf Extracts; Table S5: Results of the response surface ANOVA for the polyphenol bioaccessibility during the gastric phase of microencapsulated habanero pepper leaf extracts.

Author Contributions

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, I.M.R.-B.; Methodology, K.A.A.-B. and I.M.R.-B.; Software, M.O.R.-S.; Validation, K.A.A.-B., J.V.C.-R., M.O.R.-S. and I.M.R.-B.; Formal Analysis, K.A.A.-B. and J.V.C.-R.; Investigation, K.A.A.-B., J.V.C.-R. and I.M.R.-B.; Resources, I.M.R.-B.; Data Curation, K.A.A.-B.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, K.A.A.-B.; Writing—Review & Editing, I.M.R.-B., M.O.R.-S. and J.V.C.-R.; Visualization, I.M.R.-B. and M.O.R.-S.; Supervision, I.M.R.-B. and J.V.C.-R.; Project Administration, I.M.R.-B.; Funding Acquisition, I.M.R.-B.

Ethics Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Funding

Kevin Alejandro Avilés-Betanzos was supported by a SECIHTI scholarship (No. 661099).

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Alonso-Villegas R, González-Amaro RM, Figueroa-Hernández CY, Rodríguez-Buenfil IM. The Genus Capsicum: A Review of Bioactive Properties of Its Polyphenolic and Capsaicinoid Composition. Molecules 2023, 28, 4239. DOI:10.3390/molecules28104239 [Google Scholar]

- Herrera-Pool E, Patrón-Vázquez J, Ramos-Díaz A, Ayora-Talavera T, Pacheco N. Extraction and Identification of Phenolic Compounds in Roots and Leaves of Capsicum chinense by UPLC-PDA/MS. J. Bioeng. Biomed. Res. 2019, 3, 17–27. Available online: https://cmibq.org.mx/jbbr/images/doc/jbbr-vol-3-no-2/jbbr-vol-3-no-2-3.pdf?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- DOF. Declaratoria General de Protección de la Denominación de Origen Chile Habanero de la Península de Yucatán; Diario Oficial de la Federación: Mexico City, Mexico, 2010. Available online: https://dof.gob.mx/nota_to_doc.php%3Fcodnota%3D5063632 (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- Herrera-Pool E, Ramos-Díaz AL, Lizardi-Jiménez MA, Pech-Cohuo S, Ayora-Talavera T, Cuevas-Bernardino JC, et al. Effect of Solvent Polarity on the Ultrasound Assisted Extraction and Antioxidant capacity of Phenolic Compounds from Habanero Pepper Leaves (Capsicum chinense) and Its Identification by UPLC-PDA-ESI-MS/MS. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2021, 76, 105658. DOI:10.1016/j.ultsonch.2021.105658 [Google Scholar]

- Olguín-Rojas JA, Vázquez-León LA, Palma M, Fernández-Ponce MT, Casas L, Fernández Barbero G, et al. Re-Valorization of Red Habanero Chili Pepper (Capsicum chinense Jacq.) Waste by Recovery of Bioactive Compounds: Effects of Different Extraction Processes. Agronomy 2024, 14, 660. DOI:10.3390/agronomy14040660 [Google Scholar]

- Dai Y, van Spronsen J, Witkamp GJ, Verpoorte R, Choi YH. Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents as a New Extraction Medium for Bioactive Compounds. Anal. Chim. Acta 2013, 766, 61–68. DOI:10.1016/j.aca.2012.12.019 [Google Scholar]

- Ruesgas-Ramón M, Figueroa-Espinoza MC, Durand E. Application of Deep Eutectic Solvents (DES) for Phenolic Compounds Extraction: Overview, Challenges, and Opportunities. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2017, 65, 3591–3601. DOI:10.1021/acs.jafc.7b01054 [Google Scholar]

- Socas-Rodríguez B, Torres-Cornejo MV, Álvarez-Rivera G, Mendiola JA. Deep Eutectic Solvents for the Extraction of Bioactive Compounds from Natural Sources and Agricultural By-Products. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 4897. DOI:10.3390/app11114897 [Google Scholar]

- Pavlić B, Mrkonjić Ž, Teslić N, Kljakić AC, Pojić M, Mandić A, et al. Natural Deep Eutectic Solvent (NADES) Extraction Improves Polyphenol Yield and Antioxidant capacity of Wild Thyme (Thymus serpyllum L.) Extracts. Molecules 2022, 27, 1508. DOI:10.3390/molecules27051508 [Google Scholar]

- Duarte H, Gomes V, Aliaño-González MJ, Faleiro L, Romano A, Medronho B. Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction of Polyphenols from Maritime Pine Residues with Deep Eutectic Solvents. Foods 2022, 11, 3754. DOI:10.3390/foods11233754 [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira LMDMC, Pereira RR, Carvalho-Guimarães FBD, Remígio MSDN, Barbosa WLR, Ribeiro-Costa RM, et al. Microencapsulation by Spray Drying and Antioxidant capacity of Phenolic Compounds from Tucuma Coproduct (Astrocaryum vulgare Mart.) Almonds. Polymers 2022, 14, 2905. DOI:10.3390/polym14142905 [Google Scholar]

- Ramakrishnan Y, Adzahan NM, Yusof YA, Muhammad K, Jailani F. Effect of Wall Materials on the Spray Drying Efficiency, Powder Properties and Stability of Bioactive Compounds in Tamarillo (Solanum betaceum) Juice Microencapsulation. Powder Technol. 2018, 328, 406–414. DOI:10.1016/j.powtec.2017.12.018 [Google Scholar]

- Macías-Cortés E, Gallegos-Infante JA, Rocha-Guzmán NE, Moreno-Jiménez MR, Villanueva-Fierro I, Ochoa-Martínez LA, et al. Spray Drying Conditions of Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Polyphenols in Microcapsules of Ultrasound-Assisted Extract of Salvilla (Buddleja scordioides Kunth). ACS Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 2, 1574–1585. DOI:10.1021/acsfoodscitech.2c00212 [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Tang B, Chen J, Lai P. Microencapsulation of plum (Prunus salicina Lindl.) phenolics by spray drying and storage stability. Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 38, 530–536. DOI:10.1590/1678-457x.09817 [Google Scholar]

- Bińkowska W, Szpicer A, Stelmasiak A, Wojtasik-Kalinowska I, Półtorak A. Microencapsulation of Polyphenols and Their Application in Food Technology. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 11954. DOI:10.3390/app142411954 [Google Scholar]

- Bernal-Millán MJ, Gutiérrez-Grijalva EP, Contreras-Angulo L, Muy-Rangel MD, López-Martínez LX, Heredia JB, et al. Spray-Dried Microencapsulation of Oregano (Lippia graveolens) Polyphenols with Maltodextrin Enhances Their Stability during In Vitro Digestion. J. Chem. 2022, 2022, 8740141. DOI:10.1155/2022/8740141 [Google Scholar]

- Avilés-Betanzos KA, Cauich-Rodríguez JV, González-Ávila M, Scampicchio M, Morozova K, Ramírez-Sucre MO, et al. Natural Deep Eutectic Solvent Optimization to Obtain an Extract Rich in Polyphenols from Capsicum chinense Leaves Using an Ultrasonic Probe. Processes 2023, 11, 1729. DOI:10.3390/pr11061729 [Google Scholar]

- Chel-Guerrero LD, Oney-Montalvo JE, Rodríguez-Buenfil IM. Phytochemical Characterization of By-Products of Habanero Pepper Grown in Two Different Types of Soils from Yucatán, Mexico. Plants 2021, 10, 779. DOI:10.3390/plants10040779 [Google Scholar]

- Avilés-Betanzos KA, Cauich-Rodríguez JV, Ramírez-Sucre MO, Rodríguez-Buenfil IM. Optimization of Spray Drying Conditions for a Capsicum chinense Leaf Extract Rich in Polyphenols Obtained by Ultrasonic Probe/NADES. ChemEngineering 2024, 8, 131. DOI:10.3390/chemengineering8060131 [Google Scholar]

- Pech-Pisté R, Pérez-Aranda C, Balam A, Vargas-Coronado R, Cauich-Rodríguez JV, Avilés F. Piezoimpedance of Carbon Nanotube Yarns Coupled with Raman Spectroscopy and Its Implementation for Sensing Polymerization Kinetics. Carbon 2023, 213, 118246. DOI:10.1016/j.carbon.2023.118246 [Google Scholar]

- Torres-Martínez BM, Vargas-Sánchez RD, Torrescano-Urrutia GR, González-Ávila M, Rodríguez-Carpena JG, Huerta-Leidenz N, et al. Use of Pleurotus ostreatus to Enhance the Oxidative Stability of Pork Patties during Storage and In Vitro Gastrointestinal Digestion. Foods 2022, 11, 4075. DOI:10.3390/foods11244075 [Google Scholar]

- Aguilera-Chávez SL, Gallardo-Velázquez T, Meza-Márquez OG, Osorio-Revilla G. Spray Drying and Spout-Fluid Bed Drying Microencapsulation of Mexican Plum Fruit (Spondias purpurea L.) Extract and Its Effect on In Vitro Gastrointestinal Bioaccessibility. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 2213. DOI:10.3390/app12042213 [Google Scholar]

- Chel-Guerrero LD, Castañeda-Corral G, López-Castillo M, Scampicchio M, Morozova K, Oney-Montalvo JE, et al. In Vivo Anti-Inflammatory Effect, Antioxidant capacity, and Polyphenolic Content of Extracts from Capsicum chinense By-Products. Molecules 2022, 27, 1323. DOI:10.3390/molecules27041323 [Google Scholar]

- Avilés-Betanzos KA, Oney-Montalvo JE, Cauich-Rodríguez JV, González-Ávila M, Scampicchio M, Morozova K, et al. Antioxidant Capacity, Vitamin C and Polyphenol Profile Evaluation of a Capsicum chinense By-Product Extract Obtained by Ultrasound Using Eutectic Solvent. Plants 2022, 11, 2060. DOI:10.3390/plants11152060 [Google Scholar]

- Yuen SN, Choi SM, Phillips DL, Ma CY. Raman and FTIR Spectroscopic Study of Carboxymethylated Non-Starch Polysaccharides. Food Chem. 2009, 114, 1091–1098. DOI:10.1016/j.foodchem.2008.10.053 [Google Scholar]

- Mir SA, Bosco SJD, Bashir M, Shah MA, Mir MM. Physicochemical and Structural Properties of Starches Isolated from Corn Cultivars Grown in Indian Temperate Climate. Int. J. Food Prop. 2017, 20, 821–832. DOI:10.1080/10942912.2016.1184274 [Google Scholar]

- Kizil R, Irudayaraj J, Seetharaman K. Characterization of Irradiated Starches by Using FT-Raman and FTIR Spectroscopy. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 3912–3918. DOI:10.1021/jf011652p [Google Scholar]

- Różyło R, Szymańska-Chargot M, Zdunek A, Gawlik-Dziki U, Dziki D. Microencapsulated red powders from cornflower extract—Spectral (FT-IR and FT-Raman) and antioxidant characteristics. Molecules 2022, 27, 3094. DOI:10.3390/molecules27103094 [Google Scholar]

- Sakurai YCN, Pires IV, Ferreira NR, Moreira SGC, Silva LHMD, Rodrigues AMDC. Preparation and Characterization of Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents (NADESs): Application in the Extraction of Phenolic Compounds from Araza Pulp (Eugenia stipitata). Foods 2024, 13, 1983. DOI:10.3390/foods13131983 [Google Scholar]

- Milani A, del Zoppo M, Tommasini M, Zerbi G. The Effect of Intermolecular Dipole–Dipole Interaction on Raman Spectra of Polyconjugated Molecules: Density Functional Theory Simulations and Mathematical Models. J. Phys. Chem. B 2008, 112, 1619–1625. DOI:10.1021/jp075763o [Google Scholar]

- Monge Neto AÁ, Bergamasco RDC, de Moraes FF, Medina Neto A, Peralta RM, Khodarahmi R. Development of a Technique for Psyllium Husk Mucilage Purification with Simultaneous Microencapsulation of Curcumin. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0182948. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0182948 [Google Scholar]

- Mudgil D, Barak S, Khatkar BS. Guar Gum: Processing, Properties and Food Applications—A Review. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 51, 409–418. DOI:10.1007/s13197-011-0522-x [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed HB, Emam HE. Environmentally Exploitable Biocide/Fluorescent Metal Marker Carbon Quantum Dots. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 42916–42929. DOI:10.1039/d0ra06383e [Google Scholar]

- Buljeta I, Pichler A, Šimunović J, Kopjar M. Polysaccharides as carriers of polyphenols: Comparison of freeze-drying and spray-drying as encapsulation techniques. Molecules 2022, 27, 5069. DOI:10.3390/molecules27165069 [Google Scholar]

- Drozłowska E, Starowicz M, Śmietana N, Krupa-Kozak U, Łopusiewicz Ł. Spray-Drying Impact the Physicochemical Properties and Formation of Maillard Reaction Products Contributing to Antioxidant capacity of Camelina Press Cake Extract. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 919. DOI:10.3390/antiox12040919 [Google Scholar]

- Samborska K. Powdered honey—Drying methods and parameters, types of carriers and drying aids, physicochemical properties and storage stability. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 88, 133–142. DOI:10.1016/j.tifs.2019.03.019 [Google Scholar]

- Hu H, Wang H, Zhang Y, Kan B, Ding Y, Huang J. Characterization of Genes in Guar Gum Biosynthesis Based on Quantitative RNA-Sequencing in Guar Bean (Cyamopsis tetragonoloba). Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 10991. DOI:10.1038/s41598-019-47518-5 [Google Scholar]

- Xue H, Feng J, Tang Y, Wang X, Tang J, Cai X, et al. Research progress on the interaction of the polyphenol–protein–polysaccharide ternary systems. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2024, 11, 95. DOI:10.1186/s40538-024-00632-7 [Google Scholar]

- Karrar E, Mahdi AA, Sheth S, Mohamed Ahmed IA, Manzoor MF, Wei W, et al. Effect of maltodextrin combination with gum arabic and whey protein isolate on the microencapsulation of gurum seed oil using a spray-drying method. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 171, 208–216. DOI:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.12.045 [Google Scholar]

- Laureanti EJG, Paiva TS, de Matos Jorge LM, Jorge RMM. Microencapsulation of Bioactive Compound Extracts Using Maltodextrin and Gum Arabic by Spray and Freeze-Drying Techniques. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 253, 126969. DOI:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.126969 [Google Scholar]

- Čujić-Nikolić N, Stanisavljević N, Šavikin K, Kalaušević A, Nedović V, Bigović D, et al. Application of Gum Arabic in the Production of Spray-Dried Chokeberry Polyphenols, Microparticles Characterisation and In Vitro Digestion Method. Lek. Sirovine 2018, 38, 9–16. DOI:10.5937/leksir1838009C [Google Scholar]

- Mahdi AA, Mohammed JK, Al-Ansi W, Ghaleb ADS, Al-Maqtari QA, Ma M, et al. Microencapsulation of Fingered Citron Extract with Gum Arabic, Modified Starch, Whey Protein and Maltodextrin Using Spray Drying. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 152, 1125–1134. DOI:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.10.201 [Google Scholar]

- Navarro-Flores MJ, Ventura-Canseco LMC, Meza-Gordillo R, Ayora-Talavera TDR, Abud-Archila M. Spray drying encapsulation of a native plant extract rich in phenolic compounds with combinations of maltodextrin and non-conventional wall materials. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 57, 4111–4122. DOI:10.1007/s13197-020-04447-w [Google Scholar]

- Robert P, Gorena T, Romero N, Sepúlveda E, Chávez J, Sáenz C. Encapsulation of Polyphenols and Anthocyanins from Pomegranate (Punica granatum) by Spray Drying. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2010, 45, 1386–1394. DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2621.2010.02270.x [Google Scholar]

- Šavikin K, Živković J, Alimpić Aradski A, Živković J, Menković N, Stević T, et al. Effect of Type and Concentration of Carrier Material on the Encapsulation of Pomegranate Peel Using Spray Drying Method. Foods 2021, 10, 1968. DOI:10.3390/foods10091968 [Google Scholar]

- Ricci A, Arboleda Mejia JA, Versari A, Chiarello E, Bordoni A, Parpinello GP. Microencapsulation of Polyphenolic Compounds Recovered from Red Wine Lees: Process Optimization and Nutraceutical Study. Food Bioprod. Process. 2022, 132, 1–12. DOI:10.1016/J.FBP.2021.12.003 [Google Scholar]

- Pieczykolan E, Kurek MA. Use of Guar Gum, Gum Arabic, Pectin, Beta-Glucan and Inulin for Microencapsulation of Anthocyanins from Chokeberry. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 129, 665–671. DOI:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.02.073 [Google Scholar]

- Cea-Pavez I, Manteca-Bautista D, Morillo-Gomar A, Quirantes-Piné R, Quiles JL. Influence of the Encapsulating Agent on the Bioaccessibility of Phenolic Compounds from Microencapsulated Propolis Extract during In Vitro Gastrointestinal Digestion. Foods 2024, 13, 425. DOI:10.3390/foods13030425 [Google Scholar]

- González Morales AN, López-Giraldo LJ, Sogamoso González E, Moscote Chinchilla Y. Evaluation of the Efficiency of Encapsulation and Bioaccessibility of Polyphenol Microcapsules from Cocoa Pod Husks Using Different Techniques and Encapsulating Agents. Processes 2025, 13, 3094. DOI:10.3390/pr13103094 [Google Scholar]