Demethylation of Lignin from Rice-Straw Biorefinery: An Integrated Chemical and Biochemical Approach

Received: 16 October 2025 Revised: 20 November 2025 Accepted: 03 December 2025 Published: 09 December 2025

© 2025 The authors. This is an open access article under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

1. Introduction

Lignin is the most abundant aromatic phenolic biopolymer on Earth and a major structural constituent of plant cell walls, alongside cellulose and hemicellulose. Lignin is considered an amorphous polymeric phenol, with phenylpropanoid monomers interconnected through β–O–4, α–O–4, and C–C linkages [1,2,3]. Lignin provides structural integrity and protection to the plant cell wall.

As lignin is the most abundant natural polyphenolic bio-based material, it offers potential applications in various biochemical and materials industrial segments and as a renewable feedstock for the production of aromatic compounds [4]. However, high recalcitrance, low solubility in acids, non-polar solvents, and water, and other factors like higher molecular weight, low reactivity, and physical and chemical heterogeneity, pose significant challenges in the conversion of lignin to value-added products. Due to the aforementioned reasons, lignin is still burned for heat and energy despite its potential applications [4,5]. Therefore, increasing both the chemical and biological activity of lignin has been the subject of numerous studies in recent years. Demethylation of lignin is an approach where the reactivity of lignin can be enhanced to a greater extent. Demethylation of lignin enhances lignin’s reactivity and expands the scope of lignin’s applications towards the production of high-value chemicals and bio-based materials [4]. Methoxy groups in lignin often restrict its chemical reactivity and hinder efficient conversion into useful products. The partial or complete removal of the methoxy group increases the availability of hydroxyl groups, improving solubility and compatibility with catalytic or microbial upgrading processes. As a result, demethylated lignin can be more effectively transformed into phenolic compounds, biofuels, and platform chemicals, supporting the sustainable use of lignin in green chemistry and bio-refinery applications [4].

Chemical approaches to demethylation, particularly using hydrogen iodide (HI), have shown high efficiency in cleaving C–O bonds in lignin methoxy groups [3]. However, such methods often require harsh conditions and raise environmental concerns, highlighting the need for greener alternatives. Microbial demethylation can be considered an attractive green bio-based strategy as it provides lignin-degrading microorganisms capable of selectively modifying lignin under milder conditions. Bacteria such as Pseudomonas putida and Pseudomonas fluorescens, and fungi such as Trametes versicolor, produce enzymes (laccases, peroxidases, demethylases) that contribute to lignin modification [3]; however, their application in demethylation is limited. Particularly, there are very few studies on real substrates like biorefinery rice straw residue, which is rich in lignin [6].

Many feedstocks and approaches have been explored in recent decades to extend the utility of lignin beyond its use in power generation for operating boilers. Rice straw, being an abundant agri-based lignocellulosic material, offers great promise as a renewable feedstock to produce biofuels, chemicals, and materials. The efficient use of the rice straw lignin fraction remains a bottleneck in biomass valorization processes. Towards that end, various efforts have been made in recent years to produce biofuels from rice straw waste in South Asian countries. To make bioethanol commercially viable, the lignin component, more specifically the lignin residue obtained from second-generation bioethanol refineries, needs to be valorized effectively [7].

In typical industrial practices, 98% of lignin is burnt as fuel in the recovery boiler [8]. Therefore, there is scope and opportunity to add value to this type of biorefinery lignin emanating from second-generation cellulosic ethanol facilities. Unlike other technical lignins, such as Kraft lignin and lignosulfonates, rice straw-based lignin obtained from the cellulosic ethanol industry has not been explored in detail. Most studies on lignin have focused on Kraft lignin or Soda lignin from wood-based residues. Technical lignins derived from biorefinery operations are still comparatively underexplored, even though their structure, solubility, and reactivity differ from Kraft lignin. Furthermore, very few studies on lignin deconstruction have been reported in alkaline conditions, where microorganisms and ligninolytic enzymes struggle to function [9,10]. Addressing the above-mentioned constraints could open pathways for more efficient and integrated lignin upgrading strategies. Table 1 provides an overview of key studies focusing on lignin demethylation with regard to feedstock type and process conditions.

The present study investigates various chemical and microbial methods for demethylating lignin sourced from a rice straw-based biorefinery. The effectiveness of these methods was assessed in terms of structural modifications, functional group transformations, and morphological changes. Initially, lignin was subjected to microbial and chemical treatments separately to evaluate their individual efficacy. Subsequently, an integrated approach was applied, combining chemical demethylation with prior microbial treatment. Infrared (IR) spectroscopy and thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) were used to characterize structural changes, while total phenolic content and ABTS radical-scavenging assays confirmed demethylation. Interpretation of the IR spectra was supported by comparison with characteristic lignin functional group assignments described in earlier studies [11,12,13,14]. Scanning electron microscopy coupled with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (SEM-EDX) provided insights into morphological alterations associated with lignin changes.

Table 1. State-of-the-art studies emphasizing the demethylation of lignin.

|

Lignin Feedstock Type |

Method of Demethylation |

Treatment Conditions |

Major Findings |

Reference |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Lignin-derived aromatic compounds |

Acidic concentrated LiBr (ACLB) O-demethylation |

ACLB with 1.5 M HCl, 110 °C, 2 h |

Efficient O-demethylation of lignin-derived aromatics, improving downstream reactivity; reported procedure at moderate temperature of 110 °C |

Wang Y., Chen M., Yang Y., Ralph J., Pan X.—RSC Adv. (2023) [4] |

|

|

Alkali lignin |

Halogen-acid chemical demethylation (HBr and HI) |

Reaction with HBr or HI, 130 °C, 12 h |

Demethylation and improved reactivity of alkali lignin for phenolic resin synthesis. Application of demethylated lignin in phenolic resins. |

Wang H., Eberhardt T.L., Wang C., Gao S., Pan H.—Polymers (2019) [6] |

|

|

Lignin sourced from Phragmites australis, isolated by formosolv fractionation |

Sequential two-step formosolv fractionation |

88% formic acid delignification followed by 70% aqueous formic acid fractionation; isolation of several lignin fractions |

Fractionation produced lignin fractions with differing structural properties and antioxidant activities; this shows formosolv treatment is effective for recovering functional lignin fractions. |

Duan X., Wang X., Chen J., Liu G., Liu Y.—RSC Adv. (2022) [14] |

|

|

Lignin-rich rice straw residue (RSSC) |

Chemical and biochemical treatments to enhance phenolic content & antioxidant properties |

Alkaline extraction(NaoH + MgO, 120 °C, 2 h) and bacterial treatment on extracted lignin (30 °C for 144 H) |

Reported enhancement of phenolic content and antioxidant properties after selected chemical and biochemical treatments of rice-straw lignin-rich residue. |

Vaidya K., Ahmed F., Padmanabhan S.—Cellulose Chem. Technol. (2024) [15] |

|

|

Agricultural crop-based lignin |

Atmospheric-pressure chemical demethylation |

Several demethylation reagents were tested at atmospheric pressure, reactions at mild–moderate temperatures; FT-IR and NMR characterization |

Demonstrated demethylation at atmospheric pressure characterized structural changes, and applied demethylated lignin in fast-curing biobased phenolic resins. |

Li J., Wang W., Zhang S., Gao Q., Zhang W., Li J.—RSC Adv. (2016) [16] |

|

|

Alkaline lignin |

Microbial biodegradation by Bacillus ligniniphilus L1 |

Bacterial incubations using alkaline lignin as the sole carbon source under mesophilic conditions |

Demonstrated bacterial degradation/biotransformation of alkaline lignin; GC–MS identified multiple aromatic degradation products. |

Zhu D., Zhang P., Xie C., Sun J., Qian W.-J., Yang B.—Biotechnol. Biofuels (2017) [17] |

|

|

Various technical and model lignins |

Comprehensive review: O-demethylation (ODM) strategies |

Reviews catalytic and non-catalytic ODM, enzymatic routes, and mechanistic insights across many systems |

Broad, up-to-date synthesis of ODM advances, recommended routes, and mechanistic considerations useful for benchmarking methods and selecting promising approaches. |

Wu X., Smet E., Brandi F., Raikwar D., Zhang Z., Maes B.U.W., Sels B.F.—Angew. Chem. (2024) (review) [18] |

|

|

Technical lignin |

Mild chemical demethylation using NaOH/urea and preparation of adhesives |

NaOH/urea based demethylation under mild temperatures; product isolation and formulation into adhesives |

Reported successful demethylation under comparatively mild conditions; prepared green adhesives with reduced formaldehyde emissions and evaluated health-risk related VOCs. |

Chen Y., Shen J., Wang W., Lin L., Lv R., Zhang S., Ma J.—Int. J. Biol. Macromol. (2023) [19] |

|

|

Waste alkali lignin from an industrial stream |

Chemical demethylation to enhance adsorption |

Demethylation protocol optimized for adsorption application; characterization of surface functionality and adsorption tests |

Demethylated lignin used as a low-cost sorbent for ammonia removal or recovery |

Li JF., Li ZM., Xu JB., Guo CY., Fang GW., Zhou Y., Sun MS., Tao DJ.—Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. (2024) [20] |

|

|

Guaiacyl/syringyl dehydrogenation polymers |

Chemical demethylation using iodocyclohexane (ICH) |

ICH chemical demethylation on DHP model polymers; standard organic reaction conditions reported in the paper |

ICH demethylation increased tannin-like properties (protein-precipitation behaviour) and phenolic content in model DHPs; this demonstrates tuning functional properties via chemical demethylation. |

Kobayashi T., Tobimatsu Y., Kamitakahara H., et al.—J. Wood Sci. (2022) [21] |

|

|

Model lignin compounds |

Solid-acid catalysed demethylation in a halogen-free aqueous system |

Solid acidic catalysts in aqueous, halogen-free media; reaction conditions tailored for model compounds |

Showed conversion of model lignin monomers to polyphenolic products via solid-acid demethylation. |

Zheng Y., Wu K., Zhu Y., et al.—React. Kinet. Mech. Catal. (2023) [22] |

|

|

Biomass-derived aromatic ether polymers |

Various demethylation strategies covered |

Summarizes diverse selective chemical and catalytic procedures, conditions, and selectivity control strategies |

Presents an overview and comparative discussion on selective demethylation reactions and how to control the formation of phenol/catechol motifs. |

Harth F.M., Hočevar B., Ročnik Kozmelj T., et al.—Green Chem. (2023) [23] |

|

|

Dehydrogenation polymer (G-DHP) model lignins |

Chemical demethylation (HI, ICH) |

HI, HBr, and ICH (Iodocyclohexane) as demethylation agents. Reactions proceeded under reflux over multiple retention times. |

Demonstrated effective demethylation of synthetic guaiacyl lignins and development of tannin-like properties; analytical evidence for increased phenolic (–OH) after treatment. |

Sawamura K., Tobimatsu Y., Kamitakahara H., Takano T.—ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. (2017) [24] |

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Materials and Reagents

Rice straw lignin rich residue (RSSC) was generated at the pilot plant of Praj Matrix (capacity of 1 tonne/day), Pune, India, using the proprietary method (https://praj.net/businesslines/advanced-bioethanol/enfinity/, accessed on 29 January 2025) [25]. Magnesium oxide (≥99.0 w/w % purity), hydrogen peroxide solution (35 w/v % purity), hydrogen iodide (57% w/v), and sodium hydroxide pellets (≥98.0 w/w % purity) were purchased from Fisher Scientific, Mumbai, India. Sulfuric acid (≥93 w/v % purity) and dimethyl formamide (DMF) were purchased from LobaChemi, Kolkata, India. Luria Bertani broth, Yeast extract powder, and pure peptone powder were purchased from HiMedia, Pune, India. Gallic acid (AR graded) was purchased from Sigma Aldrich, Mumbai, India.

2.2. Extraction and Purification of Lignin from Rice Straw Lignin Rich Residue

Extraction and purification of lignin from rice straw residue were conducted as described in Vaidya et al., 2024 [15]. Rice straw lignin was mixed in water (10% w/v) and then treated with MgO (4% w/v) and NaOH (6% w/v). This mixture was then heated at 120 °C for 1 h. After the reaction, when the mixture was cooled to room temperature, it was centrifuged at 4500 RPM for 1 h using a felt-filter bag with a pore size of 5 microns. The resulting filtrate was dried as purified lignin powder and used for subsequent experiments.

2.3. Chemical Approaches to Demethylation of Lignin

Chemical demethylation of lignin was conducted with some modifications in the protocol described in the work of Wang H et al. [6]. 5 g of purified, dried lignin extracted from rice straw were used for the chemical demethylation process. The lignin was dissolved in 25 g of dimethyl formamide (DMF) in a 250-mL round-bottom flask. To the lignin-DMF solution, 25 g of 57% (w/v) hydrogen iodide (HI) was added carefully while stirring the mixture. The reaction mixture was heated to 130 °C and maintained at this temperature for 5 h under reflux conditions with continuous stirring to ensure homogeneity and facilitate demethylation.

After completion of the reaction, the mixture was allowed to cool to room temperature. The cooled reaction mixture was then filtered using cellulose filter paper to remove any insoluble residues. To the resulting liquid filtrate, 125 mL of double-distilled water was added slowly to precipitate the demethylated lignin. The precipitated lignin was collected by filtration using 5-micron filter paper identical to the first filtration step and washed with additional double-distilled water to remove any residual HI and DMF. The solid precipitate collected on the filter paper contained the demethylated lignin. The recovered lignin was subsequently dried in a hot-air oven overnight at 65 °C to ensure complete removal of moisture. The dried demethylated lignin was weighed and stored in a desiccator for further analysis and characterization.

To evaluate the influence of solvents on lignin demethylation, along with an attempt to incorporate green solvents into the reaction, additional experiments, as suggested by Wang et al. were conducted with several modifications [3]. In a separate batch, the lignin was dissolved in 25 g choline acetate instead of DMF, and the subsequent HI treatment was performed under identical conditions of 130 °C for 5 h under reflux. After the reaction mixture was cooled to room temperature, the lignin obtained from the modified protocols was recovered, purified, and dried using the same filtration and drying steps as in the original method. The dried, demethylated lignin obtained through this method was also characterized and compared with demethylated lignin where DMF was used as a solvent.

2.4. Microbial Approaches to Demethylation of Lignin

Liquid lignin media was prepared by dissolving purified lignin powder in aqueous alkaline NaOH solution of pH 9.5 until a final lignin concentration of 10% (w/v) was achieved. The diluted lignin solution was dispensed into four different flasks of 500 mL volume and sterilized by autoclaving at 121 °C for 20 min. Microbe selection and microbial demethylation were conducted similarly as described in Vaidya et al. [15] with minor modifications. Pseudomonas putida, Pseudomonas fluorescens, and Trametes versicolor were used to inoculate 3 flasks, respectively. A fourth flask was kept as a sterile control without any microbial inoculation. Each flask was supplemented with yeast extract (2 g/L final concentration) to enrich the media and facilitate microbial growth and activity, while the pH was maintained at 9 for all samples except for the Trametes versicolor flask, which was kept at a pH of 5.5. The flasks were incubated at 30 °C under mechanical agitation of 150 rpm to ensure proper aeration and microbial growth. Samples were collected every 48 h up to a total incubation period of 144 h. At each sampling interval, aliquots were withdrawn. The aliquots were individually centrifuged at 7500 RPM for 20 min to separate biomass from the liquid media. This separated liquid for each stream was then acidified to a pH of 2.5 using concentrated (98% w/v) H2SO4 to precipitate lignin. The slurry was centrifuged; the residual solid was washed with excess water until the supernatant reached a pH of ~6.0 to 7.0. Finally, the solid was dried in a hot air oven at 65 °C overnight.

2.5. Integrated Approach to Demethylation of Lignin

Purified lignin was subjected to microbial treatment using Pseudomonas putida for 96 h under the same conditions as previously described for microbial demethylation in Section 2.4. Following the incubation period, the lignin-containing liquid medium was subjected to the same downstream processing steps as described in Section 2.4 of microbial demethylation.

Pseudomonas putida was chosen as the microbial agent due to its superior performance in terms of increment in total phenolic content and antioxidant activity of lignin compared to other microbial strains evaluated [15]. The dried lignin obtained from microbial treatment was then subjected to chemical demethylation in two separate solvent systems; one with dimethyl formamide (DMF) as a solvent and the other with choline acetate (CA). Each of the two batches was processed separately to evaluate the influence of solvent choice on the efficiency of integrated demethylation. The chemical demethylation steps, including reaction conditions, reflux duration, and purification, were identical to those described for HI chemical demethylation in Section 2.3.

2.6. Analytical Techniques

2.6.1. Total Phenolic Content (TPC) Analysis

Total phenolic content for lignin samples was determined using the Folin-Ciocalteu reagent method as performed by Rumpf et al. with minor changes [13]. Lignin samples of all batches from every time point (at 24 h intervals in case of microbial demethylation batches) were diluted with Milli-Q water in a ratio of 1:20 for chemical treatment batches and a ratio of 1:10 for microbially treated batches. 60 μL of the diluted samples were made up with Milli-Q water to 5 mL and treated with 300 μL Folin–Ciocalteu reagent. Following an incubation of 6 min, 900 μL sodium carbonate was added, followed by mild stirring and incubation at 20 °C for 90 min. Samples were subjected to UV-Vis spectrophotometry on a Labindia Instruments (Thane, India) UV 3200 double-beam spectrophotometer at 765 nm wavelength with Milli-Q water as a blank. All samples were taken in triplicate.

Gallic acid was used as a standard with known, gradually increasing concentration from 0 mg/mL (blank) to 1000 mg/mL. A standard curve was obtained for gallic acid in $$Y= Mx+C$$ format, where Y is the absorbance unit at 765 nm wavelength, and x is the concentration of gallic acid in mg/mL. Absorption values of subsequent lignin samples were substituted in the obtained standard curve equation to obtain concentration in gallic acid equivalent mg/mL or GAE mg/mL.

A separate comparison study was made by incubating a sterile 10% L2 lignin batch for 144 h under identical temperature, agitation, and pH conditions to the previous conventional batches. Every 24 h, the interval was sampled and again analyzed for TPC to quantify total phenolic content after treatment with Pseudomonas putida.

2.6.2. ABTS Radical Scavenging Antioxidant Assay

The ABTS•⁺ antioxidant assay for lignin samples before and after demethylation was performed according to Duan et al., with slight procedural modifications [14]. The ABTS radical cation (ABTS•⁺) was prepared by adding potassium persulfate to an aqueous 7 mM ABTS solution such that the final concentration of potassium persulfate was 2.45 mM. Following this, the mixture was incubated in the dark at room temperature for 16 h. After incubation, the stock solution for (ABTS•⁺) was ready. A small portion of the stock solution was diluted using Milli-Q purified water such that the final absorbance of the solution was around 0.700 ± 0.02 at 734 nm. This diluted (ABTS•⁺) solution was used as the working solution for the subsequent spectroscopic assay. Standards used for the assay were butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT) and gallic acid. Demethylated lignin samples were dissolved in water to prepare stock solutions at a concentration of 10 mg/mL. Serial dilutions were performed to obtain working concentrations ranging from 1.25 mg/mL to 5 mg/mL.

The antioxidant activity of lignin samples was evaluated by mixing 1 mL of the ABTS•⁺ working solution with 10 μL of the lignin sample or standard solution. The mixture was incubated at room temperature for 6 min, and the absorbance was measured at 734 nm using a Mettler-Toledo Easy-UV spectrophotometer. Water was used as a blank. The decolorization % for both standards and for each sample was calculated as

where ‘Ab’ is the absorbance of the blank and ‘As’ is the absorbance of the respective sample.

Standard curves for both BHT and gallic acid curves were created, where decolorization was plotted against the concentration in mg/mL. The linear equations for standard curves for both BHT and gallic acid were determined in $$Y= Mx+C$$ form, where x is the concentration of BHT or gallic acid for their respective curves in mg/ mL, Y is the decolorization (%) of the (ABTS•⁺) solution, M is the slope of the curve, and C is the intercept. Antioxidant activity of each sample was calculated by substituting its respective decolorization value in ‘Y’ of the respective standard’s linear equation and determining the value of ‘x’; being the antioxidant activity of the sample in µg/mg equivalents of BHT or gallic acid, respectively.

2.6.3. IR Analysis of Lignin

Each lignin sample, after undergoing chemical or microbial demethylation, was dried in a hot air oven at 65 °C overnight to eliminate residual moisture. Each lignin sample was finely ground using a mortar and pestle to ensure a uniform particle size separately. Approximately 5 mg of the finely powdered samples were used for the analysis. The powdered sample was then analysed using Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy on a Bruker Alpha II IR spectrometer equipped with an ATR (attenuated total reflectance) module. Spectra for each sample were recorded in the range of 4000 to 400 cm−1 at a resolution of 4 cm−1, with 32 scans averaged per sample to improve signal-to-noise ratio. Background spectra were collected prior to each sample run and automatically subtracted. The resulting spectra were used to identify the characteristic functional group vibrations, particularly the broad O–H stretch of aromatic phenolic groups (~3400 cm−1), and to compare the changes in peak intensities and positions before and after demethylation.

2.6.4. Thermogravometric Measurements

Thermal degradation properties of the lignin samples before and after demethylation were evaluated following the thermogravimetric analysis procedures described by Naron et al. [26]. Approximately 10 mg of each lignin sample, both untreated and demethylated, was dried in a hot air oven at 65 °C for 24 h to ensure thorough moisture removal. The dried samples were stored in desiccators until the time for analysis. Thermal properties of the lignin samples were analyzed using a TA Instruments (New Castle, DE, USA) Q500 Thermogravimetric Analyzer. Samples were heated from 30 °C to 1000 °C at a rate of 10 °C/min under a nitrogen atmosphere at a flow rate of 50 mL/min.

2.6.5. Morphological Measurements

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was used to analyze the surface morphology and the microstructural characteristics of lignin samples. To enhance surface conductivity and prevent charging during imaging, the mounted samples were sputter-coated with a thin layer of gold of approximately 10 nm using a Quorum Technologies Ltd. (Lewes, UK) Q150R ES sputter coater under an argon atmosphere. The surface features of the prepared lignin samples were examined using an FEI (Hillsboro, OR, USA) Quanta 200 3D Scanning Electron Microscope operated under high-vacuum mode. SEM imaging was conducted at an accelerating voltage of 10–20 kV, with the working distance adjusted between 8–12 mm to optimize image resolution and depth of field. Multiple magnifications were employed to capture both surface topology and finer microstructural details.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Chemical Approaches for Demethylation of Lignin

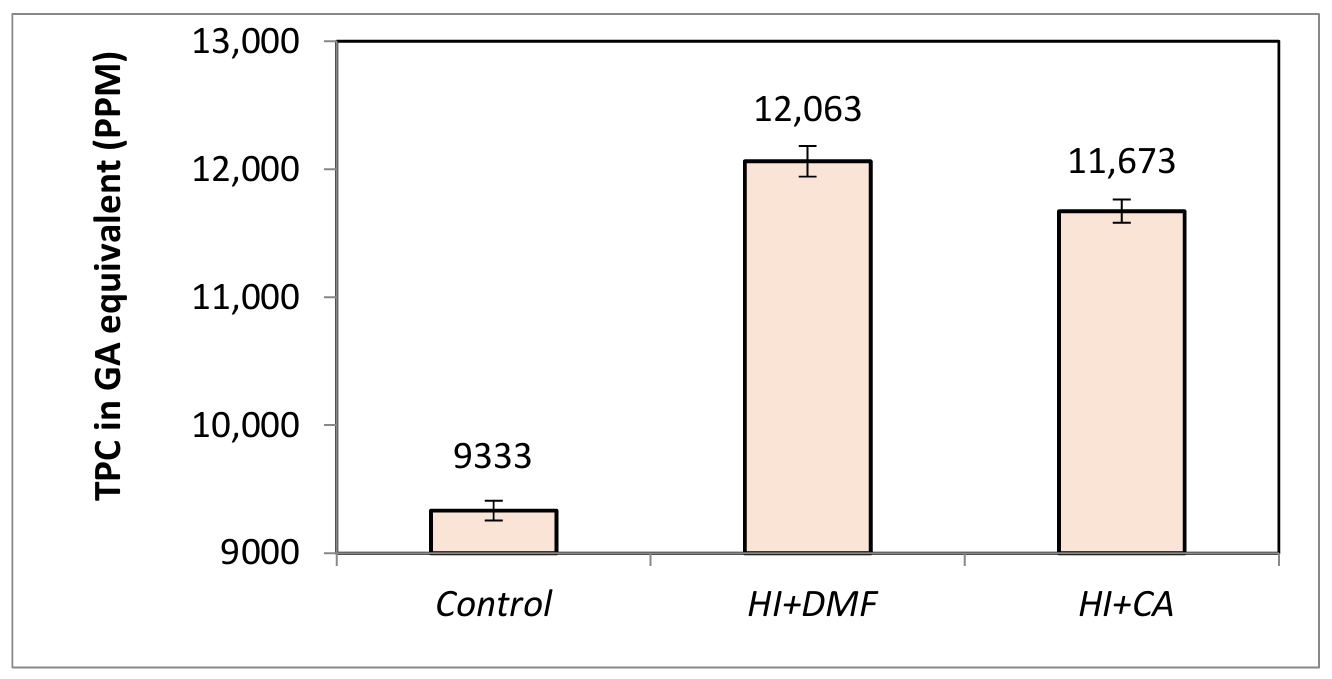

Total phenolic content analysis was conducted to evaluate the extent of demethylation, as the cleavage of methoxy groups during this process leads to the formation of any free phenolic hydroxyl groups. Chemical methods resulted in an increase in total phenolic content, indicating cleavage of methoxy groups and exposure of hydroxyl functionalities. Lignin treated with HI in DMF as a solvent showed an increase in total phenolics by about 29% whereas lignin treated with HI and choline acetate (CA) as a solvent increased the phenolic content by 25%. The chemical approaches employed here provide a more efficient means of modifying biorefinery rice-straw lignin’s structure, thereby enhancing the potential of lignin applications in polymer phenolic resins and other bio-based materials. Figure 1 shows the increase in total phenolic content in lignin samples following chemical demethylation treatement.

After demethylation, 2–3 fold increase in antioxidant activity was observed, showing a positive co-relation with total phenolic content as supported by Faustino et al [27]. In accordance with total phenolic content, the antioxidant activity showed the highest degree of increase in chemical methods of demethylation, particularly when DMF was used as a solvent. The increase in antioxidant activity was mirrored by a decrease in IC50 values of the lignin samples following demethylation treatment, which is the amount of substance required in milligrams to reduce absorbance of 1 mL of the ABTS+ working solution by 50%. The increase in antioxidant activity in BHT as well as gallic acid equivalents following chemical demethylation is shown in Figure 2. The IC50 values of all lignin samples before and after demethylation as shown in Supplementary Table S1.

Figure 2. Antioxidant activity of lignin before and after chemical demethylation treatment in Butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT) equivalents and gallic acid equivalents.

Atenuated total reflectance infrared spectroscopy (ATR-IR) was performed on the dried lignin obtained from each stream to analyze structural modifications in the lignin, particularly focusing on the demethylation of methoxy groups.

The IR spectrum of untreated lignin exhibits several characteristic peaks corresponding to its structural components. A prominent peak at 1064 cm−1 is attributed to C=O stretching. The absorption band observed between 1260–1270 cm−1 is associated with the guaiacyl units, while peaks in the 1330–1375 cm−1 range correspond to the syringyl units in lignin [13,14]. A low intensity peak at 2990 cm−1 is attributed to C–H stretching vibrations from CH, CH2, CH3, and OCH3 groups—both aliphatic and aromatic—the latter of which corresponds to methoxy groups within the lignin structure [13,14]. Additionally, the presence of peaks in the 1510–1598 cm−1 range is characteristic of aromatic skeletal vibrations (C=C) in lignin. Lastly, a broad absorption band of low intensity around 3400 cm−1 is assigned to the stretching vibrations of both aromatic and aliphatic hydroxyl (–OH) groups, indicative of phenolic structures within lignin [13,14]. For the chemically demethylated lignin samples, the –OH stretching region at approximately between 3270 cm−1 and 3400 cm−1 showed a pronounced increase, particularly in the batch where DMF was used as a solvent. Guaiacyl (1260–1270 cm−1) and syringyl (1330–1375 cm−1) groups showed a notable decrease after treatment, indicating towards demethylation of the lignin. The intense peak for untreated lignin at 1064 cm−1 was reduced and broadened over a larger area due to oxidation and formation of new functional groups. After demethylation for all chemical demethylation batches, a notable increase in the 1650–1700 cm−1 was observed, which may be due to carbonyl formation due to oxidation. The Infrared spectra of lignin samples before and after chemical demethylation is shown in Figure 3.

Thermogravimetric analysis was employed to evaluate the thermal stability and decomposition behavior of lignin by monitoring weight loss as a function of temperature. From the resulting thermograms, key parameters such as the onset decomposition temperature (To), maximum degradation temperature (Tm), and residual mass at 1000 °C were analyzed to assess the influence of demethylation on the thermal behavior and structural robustness of lignin. The thermal decomposition of untreated lignin, as observed by thermogravimetric analysis (TGA), commenced at around 277 °C. In contrast, lignin subjected to demethylation using hydrogen iodide and DMF as a solvent exhibited an earlier onset of degradation, beginning at 231 °C, while hydrogen iodide treatment with choline acetate as a solvent showed an onset of degradation of 247 °C. These results suggest alteration of the chemical structure of lignin in a manner that increased lignin’s thermal sensitivity due to increased hydroxyl functionalities and decreased methoxy groups [6,11,27]. This shift degradation may be attributed to the removal of methoxy groups, which reduces steric hindrance and weakens intermolecular interactions within the polymer matrix, thereby lowering the energy required for bond cleavage during thermal degradation. An explanation for the results obtained above may be due to chemical changes induced by different demethylation methods and their impact on lignin’s thermal behavior. The methoxy group (–OCH3) is bulkier compared to other units in a phenylpropanoid system. This contributes to higher steric hindrance, leading to constrained movement of the molecules and low reactivity of lignin. Therefore, replacement of the methoxy group with a hydroxyl group creates a higher degree of mobility. The enhanced thermal reactivity of demethylated lignin may have implications for its processing in thermochemical applications and bio-based material formulations.

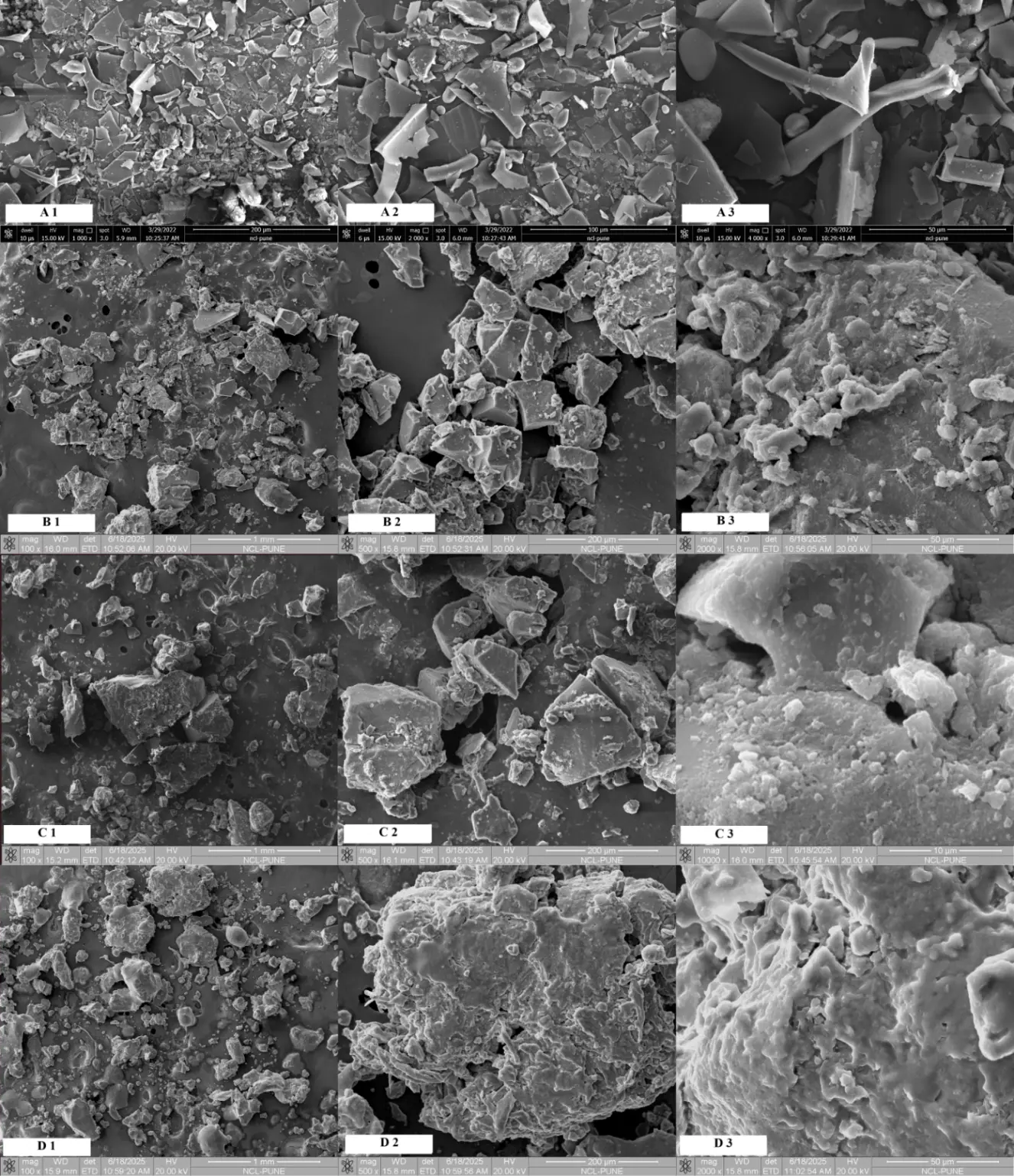

Morphological analysis of chemically treated lignin was done using Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM). Demethylated lignin treated with hydrogen iodide and DMF as solvent was dried in a vacuum oven to eliminate residual moisture and residual solvent before mounting onto aluminum SEM stubs using conductive carbon adhesive tape. The chemically demethylated lignin exhibits a more fragmented structure and noticeably angular surface with smooth texture. The overall morphology is sharp, flaky, polygonal, and compact, which indicates a rapid and uniform depolymerization facilitated by the strong nucleophilic action of HI in the polar aprotic medium DMF [9,20]. The average diameter of the particles was around 54 μm. Reduced particle size suggests deeper matrix penetration and more efficient cleavage of –OCH3 groups and ether linkages [9,20]. However, the lack of significant surface roughness may imply limited accessibility of internal pores compared to biologically treated lignin. Thermogravimetric profiles of untreated and chemically demethylated lignin are presented in Supplementary Figure S1 and Figure S2, respectively.

3.2. Microbial Approaches for Demethylation of Lignin

Microbial demethylation methods exhibited increases in phenolic content, as confirmed by both total phenolic content assays and IR spectra. Bacterial strains, including Pseudomonas putida (Pp) and Pseudomonas fluorescens (Pf), demonstrated effective demethylation under alkaline conditions, while the fungal strain Trametes versicolor (Tv) showed a similar but slightly lower efficacy at a neutral pH of 5.5. Pseudomonas putida, Pseudomonas fluorescens, and Trametes versicolor showed an increase in phenolic content by 27%, 18% and 19% respectively, after 144 h of treatment. This outcome may be attributed to the selective nature of microbial enzymes, which operate under milder conditions and may not fully access all lignin macromolecular sites. Lignolytic microbes have been identified as promising biocatalysts for lignin valorisation, though their performance is hindered by recalcitrance and structural diversity of native lignin substrates [28]. Microbial modification remains a promising strategy due to its environmentally benign nature and potential for selective functionalization. Increase in total phenolic content in lignin samples following microbial demethylation treatement is shown in Figure 4.

Supporting the increase in total phenolics, a proportional increase in antioxidant activity in lignin was observed following microbial demethylation. Pseudomonas putida showed the highest level of increase. The control flask with no microbial growth showed minimal change in antioxidant activity after 144 h, indicating the role of microbial activity in increasing lignin’s antioxidant activity. The increase in antioxidant activity in BHT as well as gallic acid equivalents following microbial demethylation is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5. Antioxidant activity of lignin before and after microbial demethylation treatment in Butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT) equivalents, gallic acid equivalents.

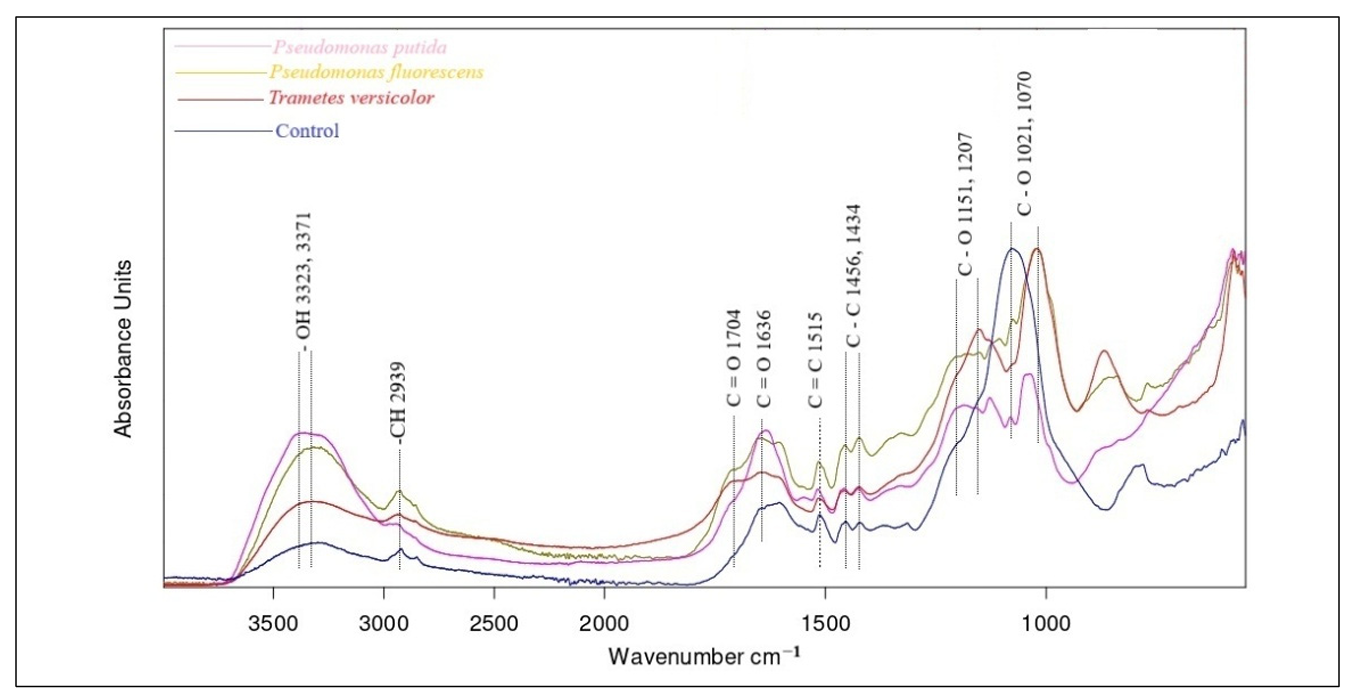

In the case of microbial demethylation, the changes in the IR spectrum showed similar trends. The broad hydroxyl (–OH) stretching band around 3400 cm−1 showed increased intensity in the microbial-treated samples, suggesting enhanced hydroxylation of the lignin polymer. This increase may be attributed to the cleavage of methoxy (–OCH3) groups, leading to the formation of more phenolic hydroxyl groups, and was observed with the highest increase in intensity for Pseudomonas putida, followed by Pseudomonas fluorescens and finally Trametes versicolor. The C=O stretching region (1650–1700 cm−1) displayed an increase in peak intensity, particularly in the Pseudomonas fluorescens-treated samples, suggesting the formation of conjugated carbonyls, quinones, or carboxyl groups. This is consistent with microbial oxidation mechanisms that introduce carbonyl functionalities during lignin depolymerization [2,29]. A noticeable reduction in intensity was observed in the C–O stretching peaks characteristic of guaiacyl (~1260 cm−1) and syringyl (~1330 cm−1) units, particularly in Pseudomonas putida and Trametes versicolor-treated lignin. This suggests demethylation and cleavage of ether bonds, leading to a decrease in methoxy (–OCH3) group content.

Furthermore, an increase in peak intensity near 1120 cm−1 (C–H deformation of syringyl units) was detected, particularly in Pseudomonas fluorescens-treated lignin, which may indicate selective modification of syringyl-type lignin structures [13,14]. Figure 6 shows the IR spectra of lignin samples before and after microbial demethylation.

Onset degradation for lignin treated with Pseudomonas putida and Pseudomonas fluorescens occurred at temperatures of 247 °C and 253 °C, respectively, while the same for lignin treated with Trametes versicolor occurred at a temperature of 259 °C.

The SEM micrograph for microbially treated lignin reveals a fractured and uneven surface morphology with square shaped flaky edges with an average diameter of approximately 102 μm. The lignin matrix appears extensively etched and disrupted, due to enzymatic depolymerization over the 144-h microbial treatment. The presence of pits, erosion zones, and a heterogeneous texture reflects the gradual cleavage of methoxy groups and partial ring-opening reactions mediated by microbial enzymes, as mentioned in the work of Tuor et al. [30]. Thermogravimetric profiles of untreated and microbially demethylated lignin are presented in Supplementary Figure S1, Figure S3 and Figure S4, respectively

3.3. Integrated Chemical and Microbial Approaches for Demethylation of Lignin

Integrated approaches to lignin demethylation with DMF used achieved a greater degree of demethylation than both chemical and microbial methods in isolation. Integrated demethylation with Pseudomonas putida for 96 h, followed by treatment with HI and DMF as solvent, resulted in a relative increase in total phenolic content by 43% while integrated demethylation under identical conditions and choline acetate used as solvent yielded an increase in total phenolics by 39%. These changes in total phenolic content in lignin after integrated demethylation approach is shown in Figure 7.

Integrated demethylation methods showed a similar pattern to chemical and microbial demethylation, in which antioxidant activity increased along with total phenolics as highlighted in Figure 8.

Figure 8. Antioxidant activity of lignin before and after integrated demethylation treatment in Butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT) equivalents, gallic acid equivalents.

The integrated method of demethylation of lignin produced comparable results but with a greater increase in phenolic associated peaks (3400 cm−1). The C–O stretching peaks characteristic of guaiacyl (~1260 cm−1) and syringyl (~1330 cm−1) units showed a notable reduction in intensity after treatment. This suggests extensive demethylation and cleavage of ether bonds, reducing the methoxy (–OCH3) content of lignin. The reduction was more pronounced in the HI+DMF-treated sample, reinforcing the effectiveness of DMF as a solvent for demethylation. Overall, the integrated approach demonstrated a synergistic effect, where Pseudomonas putida pre-treatment facilitated better chemical demethylation. Among the two solvents, DMF was more effective than choline acetate in modifying the lignin structure, as evidenced by greater hydroxylation, oxidation, and demethylation. The IR spectra of lignin samples before and after an integrated demethylation treatment is shown in Figure 9. The overall IR spectra features of the lignin samples, highlighting changes associated with chemical, microbial and integrated treatments are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2. IR results for lignin before and after demethylation.

|

Sample Name |

Peak Position (cm−1) |

Inference |

|---|---|---|

|

Extracted lignin (Non-demethylated) |

1064 |

Strong band associated with C=O stretching, typical of untreated lignin |

|

1260–1270 |

Peak visible, associated with guaiacyl units |

|

|

1330–1375 |

Peak visible, which reflects strongly the syringyl units |

|

|

1510–1598 |

Notable band associated with aromatic C=C stretching |

|

|

2990 |

Notable band linked with the methoxy group (C–H/C–OCH3 stretching) |

|

|

3400 |

Broad band related to phenolic or aliphatic –OH stretching |

|

|

Lignin treated with HI+DMF |

1107–1653 |

New peaks resulting from the splitting of the 1064 cm−1 peak. Indicative of C=O and C=C modifications |

|

1250 |

Increased intensity of the peak for the guaiacyl group |

|

|

1330–1375 2900 |

Decreased intensity for the syringyl group Reduced intensity indicated demethylation |

|

|

3400 |

Broad and more intense peak reflecting phenolic enrichment |

|

|

Pp 96 → HI+DMF |

1110–1640 |

Range of narrow peaks resulting from the splitting of peak 1064 cm−1 |

|

1250 |

Dominant peak in the 1110–1640 cm−1 range corresponding to the guaiacyl group |

|

|

1330–1375 |

Diminished intensity, corresponding to the syringyl group |

|

|

2900 |

Decreased intensity of the peak, relating to reduced methoxy group presence |

|

|

3400 |

Increased intensity, relating to the phenolic –OH group |

|

|

Pp 144 h (microbial) |

1330–1375 |

Suppressed peak relating to the syringyl group |

|

1510–1598 |

Enhanced peak intensity, relating to the C=C vibration |

|

|

1650 |

New brand present with moderate intensity, corresponding to conjugated C–O/OH groups |

|

|

2990 |

Increased band peak intensity relating to phenolic content |

|

|

3400 |

Broad peak with relatively unchanged intensity related to the methoxy group |

|

|

Pf 144 h (microbial) |

1021–1151 |

Peak splitting observed relating to the C–O stretching |

|

1250 |

Increased intensity relating to guaiacyl groups |

|

|

1330–1375 |

Largely unchanged peak intensity relating to the syringyl group |

|

|

1680–1740 |

Increased peak intensity for conjugated C=C group |

|

|

3400 |

Increased absorption as compared to extracted lignin |

The lignin sample that was demethylated with the integrated approach, where DMF was the solvent, started to degrade at 232 °C. Similarly, with choline acetate, the degradation starts at 245 °C. Thermogravimetric profiles of untreated and demethylated lignin using the integrated approach are presented in Supplementary Figure S1 and Figure S5, respectively.

In the case of the SEM image of the lignin particles treated with an integrated approach, they showed a very fluffy texture with high porosity and a globular shape, unlike the flaky and sharp-edged particles of lignin treated microbially or chemically in isolation. This suggests that the initial microbial treatment weakened the lignin network and exposed reactive sites, which the subsequent HI in DMF treatment exploited to achieve further fragmentation and demethylation, resulting in particles that showed significantly higher globular morphology with semi-porous, heterogeneous surfaces [30]. The average diameter of the particles was around 74 μm. Morphological assessment of demethylated lignin via scanning electron microscopy (SEM) reveals clear distinctions based on the treatment methodology employed. Lignin subjected to microbial demethylation using Pseudomonas putida exhibited a highly irregular, flaky surface indicative of enzymatic degradation and partial structural breakdown. In contrast, chemical demethylation using hydrogen iodide in DMF resulted in reduced particle size and a more compact, uniform surface, reflecting efficient chemical cleavage of methoxy and ether linkages. Notably, the lignin treated with the integrated approach involving sequential biological followed by chemical demethylation demonstrated distinct characteristics with highly fluffy and globular morphology with increased surface area, suggesting a synergistic interaction between the two processes. The SEM images of untreated lignin, chemically demethylated, microbially demethylated and lignin demethylated using the integrated approach are shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10. (A1–A3) SEM image for non-demethylated lignin; (B1–B3) SEM image for demethylated lignin treated with hydrogen iodide in dimethyl formamide (C1–C3) SEM image for demethylated lignin treated with Pseudomonas putida for 144 h; (D1–D3) SEM image for demethylated lignin treated with Pseudomonas putida for 96 h followed by hydrogen iodide in dimethyl formamide.

4. Conclusions

The present study demonstrates the distinct differences between chemical and microbial methods of lignin demethylation, as evidenced by IR, TGA, and total phenolic content analyses. The chemical demethylation approach, particularly in batches utilizing DMF as a solvent, resulted in a significant increase in the phenolic content of the lignin composition. This enhanced phenolic content correlated with a greater increase in reactivity, as observed in the TGA thermograms. Notable advantages of the chemical method include a comparatively low reaction time, requiring only 5 h for effective demethylation. Attempts to employ greener solvents, specifically choline acetate as a replacement for DMF, yielded comparatively less effective demethylation.

Additionally, microbial approaches are more environmentally sustainable compared to chemical methods. An integrated approach incorporating microbial and chemical demethylation was also explored to optimize the advantages of both methodologies. Pre-treatment of lignin with Pseudomonas putida for 96 h, followed by subsequent chemical demethylation after drying, resulted in a higher increase in phenolic content compared to individual chemical or microbial methods. Finally, the integrated approach adopted here can help in mitigating the limitations associated with either due to chemical or biological methods of demethylation.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be found at: https://www.sciepublish.com/article/pii/787, Figure S1: Thermogravimetric graph of purified lignin (non-demethylated); Figure S2: Thermogravimetric graph of chemically demethylated lignin using HI and (a) DMF as solvent (b) CA as solvent; Figure S3: Thermogravimetric graph of microbially demethylated with (a) Pseudomonas putida (b) Pseudomonas fluorescens; Figure S4: Thermogravimetric graph of microbially demethylated with Trametes versicolor; Figure S5. Thermogravimetric graph of lignin demethylated with the integrated approach, initially with Pseudomonas putida followed by HI with (a) DMF as solvent (b) CA as solvent; Table S1: IC50 values of lignin samples before and after demethylation.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Pranita Pawar and Pratiksha Japtap of Praj Matrix for their assistance with analytical equipment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.P., F.A. and K.V.; Methodology, K.V. and K.R.; Validation, K.V., F.A. and K.R.; Formal Analysis, K.V.; Investigation, K.V.; Resources, K.R.; Data Curation, K.V.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, K.V.; Writing—Review & Editing, S.P.; Visualization, S.P. and K.V.; Supervision, S.P.; Project Administration, S.P.; Funding Acquisition, S.P.

Ethics Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data provided in this study are included within the article and/or supporting materials.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

-

Boeriu CG, Bravo D, Gosselink RJA, van Dam JEG. Characterisation of structure-dependent functional properties of lignin with infrared spectroscopy. Ind. Crops Prod. 2004, 20, 205–218. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2004.04.022. [Google Scholar]

-

Crawford DL, Crawford RL. Microbial degradation of lignin. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 1980, 2, 11–22. doi:10.1016/0141-0229(80)90003-4. [Google Scholar]

-

Wenger J, Haas V, Stern T. Why can we make anything from lignin except money? Towards a broader economic perspective in lignin research. Curr. For. Rep. 2020, 6, 294–308. doi:10.1007/s40725-020-00126-3. [Google Scholar]

-

Wang Y, Chen M, Yang Y, Ralph J, Pan X. Efficient O-demethylation of lignin-derived aromatic compounds under moderate conditions. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 5925–5932. doi:10.1039/D3RA00245D. [Google Scholar]

-

Sethupathy S, Morales GM, Gao L, Wang H, Yang B, Jiang J, et al. Lignin valorization: Status, challenges and opportunities. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 347, 126696. doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2022.126696. [Google Scholar]

-

Wang H, Eberhardt TL, Wang C, Gao S, Pan H. Demethylation of alkali lignin with halogen acids and its application to phenolic resins. Polymers 2019, 11, 1771. doi:10.3390/polym11111771. [Google Scholar]

-

Rinaldi R, Jastrzebski R, Clough MT, Ralph J, Kennema M, Bruijnincx PCA, et al. Paving the Way for Lignin Valorisation: Recent Advances in Bioengineering, Biorefining and Catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 8164–8215. doi:10.1002/anie.201510351. [Google Scholar]

-

Ningthoujam R, Jangid P, Yadav VK, Sahoo DK, Patel A, Dhingra HK. Bioethanol production from alkali-pretreated rice straw: effects on fermentation yield, structural characterization, and ethanol analysis. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2023, 11, 1243856. doi:10.3389/fbioe.2023.1243856. [Google Scholar]

-

Xu Z, Li J, Li P, Cai C, Chen S, Ding B, et al. Efficient lignin biodegradation triggered by alkali-tolerant ligninolytic bacteria through improving lignin solubility in alkaline solution. J. Bioresour. Bioprod. 2023, 8, 461–477. doi:10.1016/j.jobab.2023.09.004. [Google Scholar]

-

Yunus RM, Zeglam T, Khan MMR, Jemaat Z, Othman MP. Recent methods of lignin demethylation: A mini review. AIP Conf. Proc. 2024, 3014, 070004. doi:10.1063/5.0201914. [Google Scholar]

-

Liu Y, Hu T, Wu Z, Zeng G, Huang D, Shen Y, et al. Study on biodegradation process of lignin by FTIR and DSC. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2014, 21, 14004–14013. doi:10.1007/s11356-014-3342-5. [Google Scholar]

-

Derkacheva O, Sukhov D. Investigation of lignins by FTIR spectroscopy. Macromol. Symp. 2008, 265, 61–68. doi:10.1002/masy.200850507. [Google Scholar]

-

Rumpf J, Burger R, Schulze M. Statistical evaluation of DPPH, ABTS, FRAP, and Folin–Ciocalteu assays to assess the antioxidant capacity of lignins. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 233, 123470. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.123470. [Google Scholar]

-

Duan X, Wang X, Chen J, Liu G, Liu Y. Structural properties and antioxidation activities of lignins isolated from sequential two-step formosolv fractionation. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 24242–24251. doi:10.1039/D2RA02085H. [Google Scholar]

-

Vaidya K, Ahmed F, Padmanabhan S. Enhancement of phenolic content and antioxidant properties through chemical and biochemical treatment of lignin-rich rice straw residue. Cellulose Chem. Technol. 2024, 58, 529–539. doi:10.35812/CelluloseChemTechnol.2024.58.49. [Google Scholar]

-

Li J, Wang W, Zhang S, Gao Q, Zhang W, Li J. Preparation and characterization of lignin demethylated at atmospheric pressure and its application in fast curing biobased phenolic resins. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 67435–67443. doi:10.1039/C6RA11966B. [Google Scholar]

-

Zhu D, Zhang P, Xie C, Sun J, Qian WJ, Yang B. Biodegradation of alkaline lignin by Bacillus ligniniphilus L1. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2017, 10, 44. doi:10.1186/s13068-017-0735-y. [Google Scholar]

-

Wu X, Smet E, Brandi F, Raikwar D, Zhang Z, Maes BUW, et al. Advancements and perspectives toward lignin valorization via O-demethylation. Angew. Chem. 2024, 63, e202317257. doi:10.1002/anie.202317257. [Google Scholar]

-

Chen Y, Shen J, Wang W, Lin L, Lv R, Zhang S, et al. Demethylation of lignin under mild conditions and preparation of green adhesives to reduce formaldehyde emissions and health risks. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 242, 124462. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.124462. [Google Scholar]

-

Li JF, Li ZM, Xu JB, Guo CY, Fang GW, Zhou Y, et al. Demethylation of waste alkali lignin for rapid and efficient ammonia adsorption. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2024, 63, 3282–3289. doi:10.1021/acs.iecr.3c04306. [Google Scholar]

-

Kobayashi T, Tobimatsu Y, Kamitakahara H, Takano T. Demethylation and tannin-like properties of guaiacyl/syringyl-type and syringyl-type dehydrogenation polymers using iodocyclohexane. J. Wood Sci. 2022, 68, 51. doi:10.1186/s10086-022-02059-w. [Google Scholar]

-

Zheng Y, Wu K, Zhu Y, Liu Y, Wang B, Lu H, et al. Demethylation of model lignin to polyphenols catalyzed by solid acid in halogen-free aqueous system. React. Kinet. Mech. Catal. 2023, 136, 1407–1421. doi:10.1007/s11144-023-02420-0. [Google Scholar]

-

Harth FM, Hočevar B, Ročnik Kozmelj T, Jasiukaitytė-Grojzdek E, Blüm J, Fiedel M, et al. Selective demethylation reactions of biomass-derived aromatic ether polymers for bio-based lignin chemicals. Green Chem. 2023, 25, 10117–10143. doi:10.1039/D3GC02867D. [Google Scholar]

-

Sawamura K, Tobimatsu Y, Kamitakahara H, Takano T. Lignin functionalization through chemical demethylation: Preparation and tannin-like properties of demethylated guaiacyl-type synthetic lignins. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2017, 5, 5424–5431. doi:10.1021/acssuschemeng.7b00748. [Google Scholar]

-

Pal SS, Pai PS, Deshmukh AP, Nalwade SU, Borage NA, Deshpande GB, et al. Method for the Production of Ethanol from Corn Fibres. EP3987044A1, 27 April 2022. Available online: https://patents.google.com/patent/EP3987044A1/en (accessed on 29 January 2025). [Google Scholar]

-

Naron DR, Collard FX, Tyhoda L, Görgens JF. Characterisation of lignins from different sources by appropriate analytical methods: Introducing thermogravimetric analysis-thermal desorption-gas chromatography–mass spectroscopy. Ind. Crops Prod. 2017, 101, 61–74. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2017.02.041. [Google Scholar]

-

Faustino H, Gil N, Baptista C, Duarte AP. Antioxidant activity of lignin phenolic compounds extracted from kraft and sulphite black liquors. Molecules 2010, 15, 9308–9322. doi:10.3390/molecules15129308. [Google Scholar]

-

Dey S, Basu R. Lignin valorisation using lignolytic microbes and enzymes: Challenges and opportunities. In Trends in Biotechnology of Polyextremophiles; Shah MP, Dey S, Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-55032-4_17. [Google Scholar]

-

Choi JH, Cho SM, Kim JC, Park SW, Cho YM, Koo B, et al. Thermal properties of ethanol organosolv lignin depending on its structure. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 1534–1546. doi:10.1021/acsomega.0c05234. [Google Scholar]

-

Tuor U, Winterhalter K, Fiechter A. Enzymes of white-rot fungi involved in lignin degradation and ecological determinants for wood decay. J. Biotechnol. 1995, 41, 1–17. doi:10.1016/0168-1656(95)00042-O. [Google Scholar]