Text Mining Approaches for Protein Function Annotation: Challenges and Opportunities

Received: 03 October 2025 Revised: 24 November 2025 Accepted: 11 December 2025 Published: 22 December 2025

© 2025 The authors. This is an open access article under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

1. Introduction

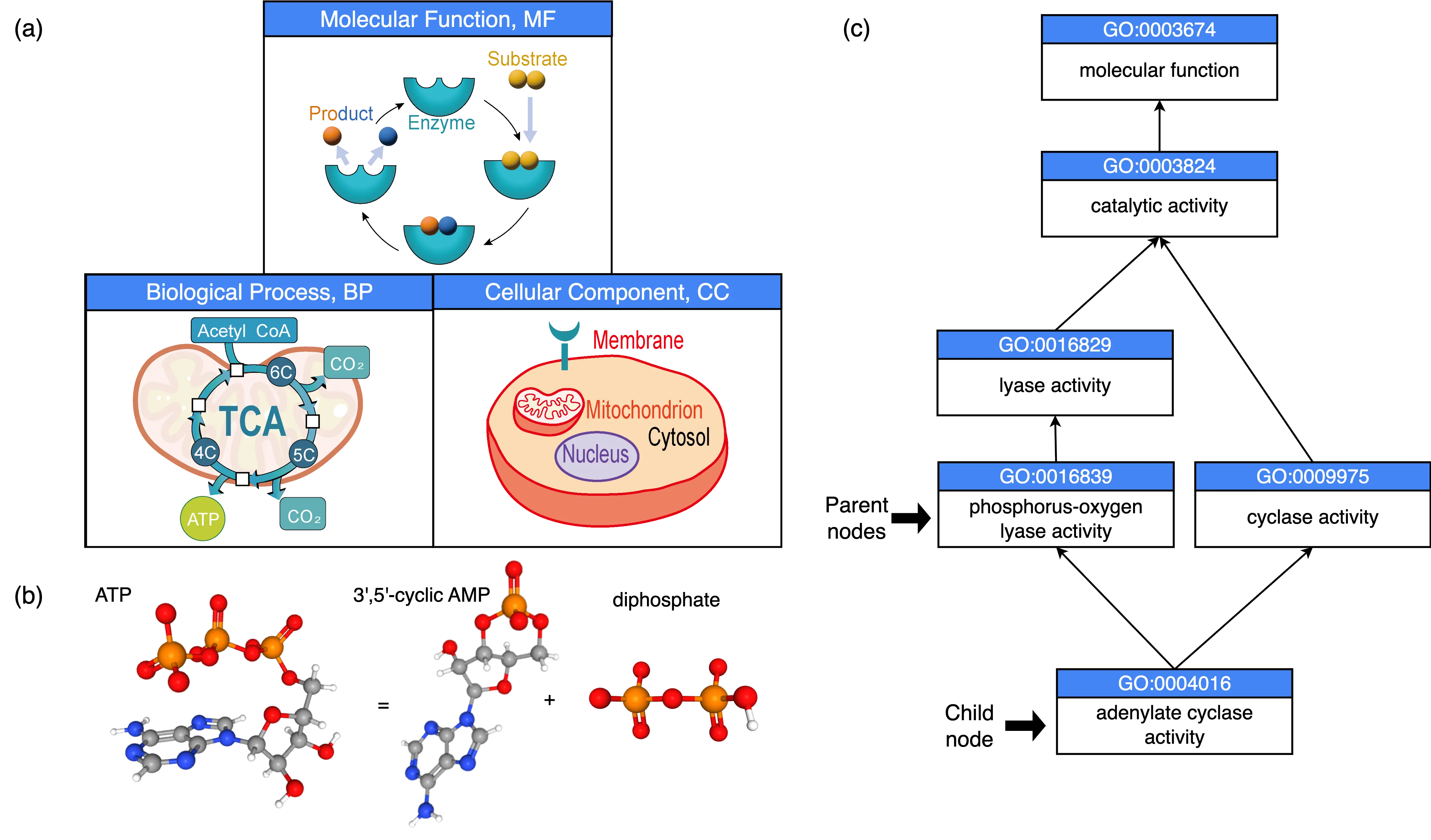

As the direct executors of biological functions, proteins are responsible for catalysis, regulation, transport, and recognition. Understanding protein function is essential for the success of quantitative synthetic biology. To standardize the description of protein functions, several classification systems have been established, including the Gene Ontology (GO) [1], the Enzyme Commission (EC) numbering system [2], and the Human Phenotype Ontology (HPO) [3]. Among these, GO is the most widely used and comprehensive framework (Figure 1a), encompassing three aspects: Biological Process (BP), Cellular Component (CC), and Molecular Function (MF). BP describes biological pathways or developmental events; CC characterizes subcellular localization or molecular complex formation; MF defines molecular events in which proteins participate, such as enzymatic reactions, many of which correspond to EC numbers. GO terms are structured as a directed acyclic graph (DAG), where nodes represent GO terms and edges denote hierarchical relationships. For example, the term adenylate cyclase activity (GO:0004016, EC 4.6.1.1) refers to the enzymatic reaction that catalyzes the conversion of an ATP into a cyclic AMP molecule (Figure 1b). In the DAG, this GO term has five parent nodes (Figure 1c), two of which are direct parent nodes.

Figure 1. Illustration of Gene Ontology (GO). (a) Three aspects of GO: Molecular Function (MF), Biological Process (BP), and Cellular Component (CC). (b) The chemical reaction is catalyzed by the adenylate cyclase. (c) The directed acyclic graph (DAG) consists of the GO term for adenylate cyclase activity and its parent GO terms. The two direct parent nodes of the adenylate cyclase activity node is indicated by arrows.

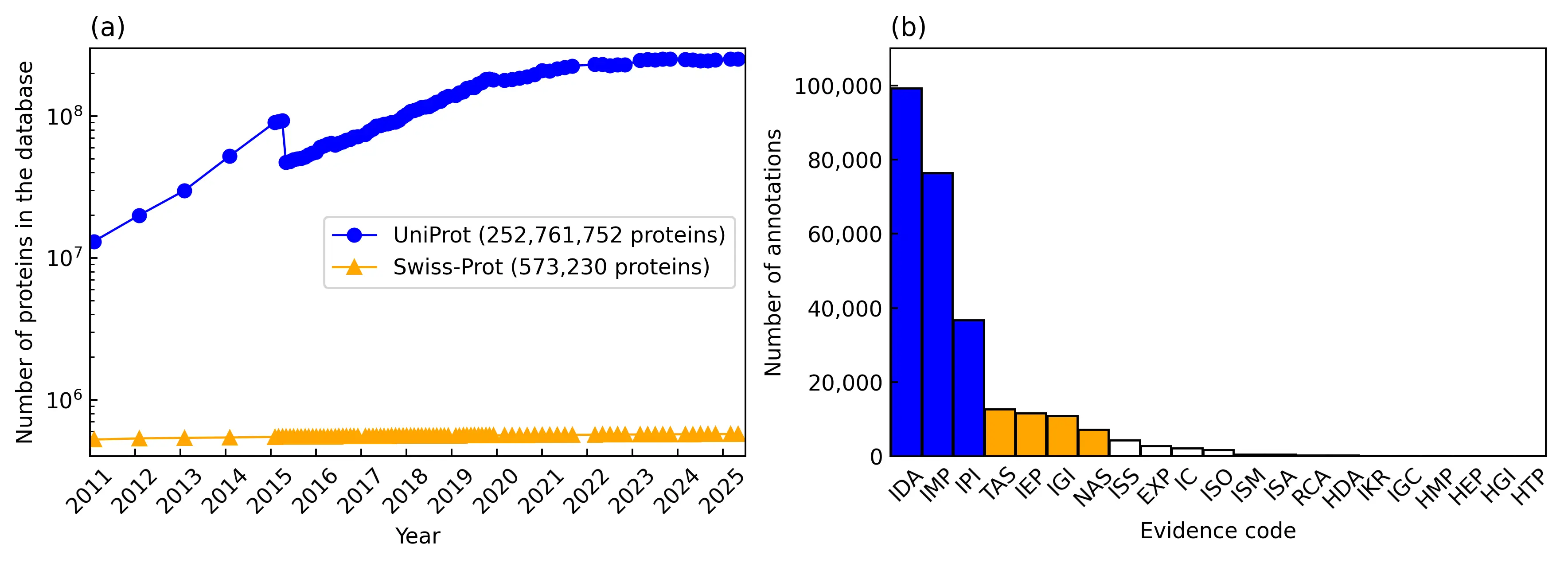

The UniProt database [4] provides functional and literature annotations for proteins. Curators first extract functional information from sources such as PubMed, record it in free-text format, and assign corresponding GO annotations [5]. However, manual annotation is both labor-intensive and time-consuming, leading to substantial delays in updating functional information from the literature. For example, a 1999 study reporting that RasGap regulates the enzymatic activity of Ras [6] has yet to be reflected in UniProt functional annotations. As of the end of 2024, UniProt contained annotations for 444,251 publications, of which only 40.8% (181,306) include free-text descriptions, and 40.5% (180,156) are linked to GO annotations. Meanwhile, UniProt has accumulated approximately 250 million protein sequences, but only about 570,000 entries have been manually annotated (Figure 2). The issue of unannotated proteins is a significant issue even for some model organisms. For example, although Mycoplasma mycoides is a model organism in synthetic biology, the biological functions for approximately one-third of its essential genes are unknown [7]. This issue is even more problematic for proteins from non-model organisms, where homology-based function transfer fails. For instance, we examined a trigger-factor protein (TIG_HELPY) from a non-model species whose sequence identity to characterized proteins is below 30%. Standard homology-based transfer provides no reliable functional assignment, yet its experimentally supported molecular function—peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase activity—is documented in the literature. This example illustrates that even when homology signals are weak, relevant functional information may still exist in the literature, underscoring the importance of extracting and prioritizing informative publications.

To address the lag in manual annotation, UniProt has incorporated function prediction algorithms as a complementary approach. Different annotation strategies correspond to specific GO evidence codes (https://geneontology.org/docs/guide-go-evidence-codes/, accessed on 28 September 2025, Table 1), which are categorized as low-throughput experimental evidence (EXP, IDA, IPI, IMP, IGI, IEP), high-throughput experimental evidence (HTP, HDA, HMP, HGI, HEP), computational analysis (ISS, ISO, ISA, ISM, IGC, RCA), and phylogenetic inference (IBA, IBD, IKR, IRD) [8], author statements (TAS, NAS), and curator statements (IC). A special evidence code, IEA, corresponds to fully automated computational predictions, accounting for 99.5% of annotations with an estimated error rate of ~5%. Phylogeny-based annotations represent 0.3% of annotations but have a much higher error rate of ~31%. By contrast, experimentally supported annotations have error rates close to zero, though they constitute only 0.2% of the total [9], with the remaining annotation types collectively accounting for 0.2%.

Table 1. Evidence codes used for Gene Ontology annotation.

|

Evidence Code |

Detailed Explanation |

|---|---|

|

Inferred from Experiment (EXP) |

Biological function validated by experiment |

|

Inferred from Direct Assay (IDA) |

Biological functions validated by biochemical or cell biological experiments |

|

Inferred from Physical Interaction (IPI) |

Experimentally validated protein–protein, protein–nucleic acid, or protein–small molecule ligand interactions |

|

Inferred from Mutant Phenotype (IMP) |

Biological function inferred from functional differences between two alleles of the same gene |

|

Inferred from Genetic Interaction (IGI) |

Biological function experimentally validated through sequence or expression alterations involving two or more genes |

|

Inferred from Expression Pattern (IEP) |

Biological process inferred from the spatial or temporal pattern of gene expression |

|

Inferred from High Throughput Experiment (HTP) |

Biological function validated by high-throughput experiments |

|

Inferred from High Throughput Direct Assay (HDA) |

Biological functions validated by high-throughput biochemical experiments or high-throughput cell biology experiments |

|

Inferred from High Throughput Mutant Phenotype (HMP) |

Biological function inferred from the functional differences between two alleles of a gene observed in high-throughput experiments |

|

Inferred from High Throughput Genetic Interaction (HGI) |

Biological function validated by high-throughput experiments involving sequence or expression changes in two or more genes |

|

Inferred from High Throughput Expression Pattern (HEP) |

Biological processes inferred from the spatial or temporal patterns of gene expression observed in high-throughput experiments |

|

Inferred from Sequence or Structural Similarity (ISS) |

Biological function predicted based on sequence analysis or structural similarity and manually reviewed |

|

Inferred from Sequence Orthology (ISO) |

Biological function predicted based on orthologous sequence relationships and manually reviewed |

|

Inferred from Sequence Alignment (ISA) |

Biological function predicted based on sequence alignment; both the functional prediction and the sequence alignment have been manually reviewed |

|

Inferred from the Sequence Model (ISM) |

Biological function predicted based on statistical models of protein families (e.g., Hidden Markov Models such as Pfam) and subsequently manually curated |

|

Inferred from Genomic Context (IGC) |

Biological function predicted based on neighboring genomic elements of the target gene and manually curated |

|

Inferred from Reviewed Computational Analysis (RCA) |

Biological functions predicted based on large-scale experimental data (e.g., yeast two-hybrid, mass spectrometry, gene chips) or by integrating multiple data types, and subsequently manually reviewed |

|

Inferred from the Biological aspect of an Ancestor (IBA) |

Biological function of a descendant gene is inferred from the function of its ancestral gene in the phylogenetic tree |

|

Inferred from the Biological aspect of Descendant (IBD) |

Biological function of an ancestral gene inferred from the functions of descendant genes in the phylogenetic tree |

|

Inferred from Key Residues (IKR) |

Loss of biological function inferred from the absence of critical amino acid residues |

|

Inferred from Rapid Divergence (IRD) |

Loss of biological function inferred from rapid evolutionary divergence between descendant and ancestral genes |

|

Traceable Author Statement (TAS) |

Biological function inferred from references cited within the introduction or discussion sections of review or experimental publications |

|

Non-traceable Author Statement (NAS) |

Biological function inferred from textual descriptions in the literature that lack explicit experimental evidence or supporting references |

|

Inferred by Curator (IC) |

Biological functions inferred from existing functional annotations of the protein; for example, a known function of a eukaryotic protein, “RNA polymerase II activity”, can suggest a functional annotation of “nucleus” |

|

Inferred from Electronic Annotation (IEA) |

Biological function predicted computationally without manual review |

Figure 2. Statistics of function annotations in UniProt. (a) Accumulation of protein entries in the UniProt and Swiss-Prot databases in the past 15 years. The drop in the number of UniProt proteins in 2015 is caused by the removal of redundant microbial proteins, i.e., if two almost identical proteins are from different strains or isolates of the same species, only one protein is kept. (b) Number of GO annotations for different evidence codes. Blue, orange, and white indicate annotation counts greater than 20,000, greater than 10,000, and less than 10,000, respectively.

2. Protein Function Prediction and the Critical Assessment of Function Annotation (CAFA)

2.1. Existing Protein Function Prediction Algorithms

Given the importance of protein function annotation—particularly Gene Ontology (GO) annotation—for life science research, and the scarcity of manual annotations, accurate and efficient protein function prediction algorithms are essential. Consequently, numerous methods have been developed (Table 2). Broadly, these algorithms can be categorized into two mainstream approaches: (i) template-based function prediction, which identifies homologous proteins in databases and transfers their annotations to the query protein; and (ii) de novo machine learning–based prediction, which derives protein functions directly from sequence and/or structural features, thereby reducing reliance on homologous templates. In addition, hybrid approaches have emerged that integrate both template-based and de novo strategies.

Early protein function prediction methods were predominantly template-based, relying on sequence similarity between the query protein and annotated proteins. For example, GOtcha [10], Blast2GO [11], and BAR+ [12] employed BLASTp [13] to search template databases and transfer functional annotations from matched sequences. Other methods, such as ConFunc [14], PFP [15], and GoFDR [16], followed a similar principle but replaced BLASTp with the more sensitive PSI-BLAST [13]. HFSP [17] adopted the faster MMseqs2 [18] for sequence similarity searches, while several methods [19,20,21] employed DIAMOND [22] as an alternative to BLASTp and PSI-BLAST to further improve computational efficiency. A recent benchmarking study [23] demonstrated that, with appropriate parameter settings, BLASTp-, DIAMOND-, and MMseqs2-based similarity search approaches achieve comparable prediction accuracy.

In addition to sequence similarity–based template searches, structure similarity–based approaches have also been widely adopted. For instance, the COFACTOR algorithm [24] and its successor MetaGO [25] employ the TM-align program [26] to align the three-dimensional structure of a query protein against templates in the BioLiP structural database [27]. Functional information derived from structural templates is then integrated with that obtained from sequence-based searches using BLASTp/PSI-BLAST and from the functions of interacting proteins, thereby generating final predictions. Similarly, ProFunc [28] applies the SSM [29] and Jess [30] programs to perform global and local structural template matching, respectively. More recently, StarFunc [31] combines Foldseek [32] for rapid structural template screening against the BioLiP [27] and AlphaFold [33] databases with TM-align for refined structural alignment. The functional information obtained from structural templates is further integrated with sequence templates, Pfam protein domain families [34], protein–protein interaction networks, and the InterLabelGO deep learning model [35], followed by random forest–based classification to yield the final prediction.

Beyond structural template searches, the three-dimensional structure of a query protein can also be leveraged to extract amino acid residue contact maps, which serve as input to deep learning models for de novo function prediction without relying on templates. Early structure-based deep learning methods for GO prediction, such as DeepFRI [36], as well as later approaches including Struct2Go [37] and TALE-cmap [38], adopted this strategy. More recently, the CLEAN-Contact algorithm [39] extended this idea to predict EC numbers.

In addition to sequence and structural information, other sources such as protein–protein interactions (PPIs), gene expression profiles, and protein domain families have been utilized for protein function prediction. For example, the MS-kNN algorithm [40] integrates sequence similarity, gene expression profiles, and PPI information within a k-nearest neighbor framework. The INGA algorithm [41] combines sequence similarity, PPI data, and Pfam [34] protein domain family information. GOLabeler [42] incorporates protein domain information from the InterPro database [43], frequencies of consecutive three-amino-acid fragments, and homologous sequences, which are integrated using gradient boosted decision trees (GBDT) [44] to generate final GO predictions. Its successors, NetGO [45] and NetGO2.0 [46], further incorporate PPI networks and text-mined data.

Beyond traditional machine learning methods such as random forests [31], k-nearest neighbors [40], and gradient boosted trees [42,44,46], deep learning models that rely solely on the query protein sequence have gained increasing attention. Early deep learning models for GO prediction, including DeepGO [47], DeepGOplus [19], and ProteInfer [48], convert the amino acid sequence (or three-residue-long fragments) into numerical features via one-hot encoding, which are then processed by convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and ultimately fed into fully connected layers to generate functional predictions. Similarly, early deep learning models for EC number prediction, such as ProteInfer [48] DeepEC [49], and ECPICK [50], adopt the same one-hot encoding plus the CNN paradigm. Recent generations of deep learning models, including GO predictors ATGO+ [51], DeepGO-SE [52], ProtBoost [53], DPFunc[54], and InterLabelGO [35], as well as EC predictors DeepECtransformer [55] and CLEAN [56], have moved away from one-hot encoding. Instead, they leverage protein language models (PLMs) based on Transformer architectures [57], such as ESM [58] and ProtT5 [59] to extract sequence representations. These PLM-derived features are then aggregated through mean pooling and processed by fully connected networks to produce final function predictions.

Table 2. Existing methods for protein function prediction.

|

Methods |

Source of Functional Prediction Information (Features) |

Machine Learning Model |

|---|---|---|

|

GOtcha, Blast2GO, BAR+ |

Homologous sequences obtained from BLASTp Search |

None |

|

ConFunc, PFP, GoFDR |

Homologous sequences obtained from PSI-BLAST Search |

None |

|

HFSP |

Homologous sequences obtained from MMseqs2 Search |

None |

|

ProFunc |

Homologous sequences obtained from BLASTp search; similar structures identified through SSM and Jess structural searches |

None |

|

COFACTOR |

Homologous sequences obtained from BLASTp and PSI-BLAST searches, similar structures identified by TM-align structural search, protein–protein interactions |

None |

|

MetaGO |

Homologous sequences obtained from BLASTp and PSI-BLAST searches, similar structures identified by TM-align structural search, protein–protein interactions |

Logistic Regression |

|

StarFunc |

Homologous sequences obtained from BLASTp search, structural analogs from Foldseek and TM-align, Pfam protein domain families, protein–protein interactions; target protein sequences (features extracted using the ESM protein language model) |

Logistic Regression, Fully Connected Neural Network (CNN), Random Forest |

|

DeepFRI, Struct2Go |

Residue contact maps derived from 3D structures, target protein sequences (one-hot encoding) |

Graph Convolutional Network (GCN) |

|

TALE-cmap |

Residue contact maps extracted from 3D structures, multiple sequence alignments (features extracted using the ESM-MSA protein language model) |

Transformer |

|

CLEAN-Contact |

Residue contact maps extracted from three-dimensional structures, target protein sequences (features extracted using the ESM protein language model) |

Convolutional Neural Network |

|

MS-kNN |

Homologous sequences, gene expression profiles, protein–protein interactions |

k-nearest neighbors (k-NN) |

|

INGA |

Homologous sequences obtained from BLASTp search, protein–protein interactions, Pfam protein domain families |

None |

|

GOLabeler |

Homologous sequences obtained from BLASTp search, InterPro protein domain families, target protein sequence features (frequency of consecutive tripeptides, sequence features extracted by ProFET) |

Logistic Regression, Gradient Boosted Trees |

|

NetGO |

Homologous sequences obtained from BLASTp, InterPro protein domain families; protein–protein interactions, target protein sequence features (trigram amino acid frequencies, sequence features extracted by ProFET) |

Logistic Regression, Gradient Boosted Trees |

|

NetGO2.0 |

Homologous sequences obtained from BLASTp, InterPro protein domain families, protein–protein interactions, target protein sequence (tri-peptide frequency, one-hot encoding), PubMed abstracts |

Logistic Regression, Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory (BiLSTM) networks, Gradient Boosting Trees |

|

DeepGO, DeepGOplus, ProteInfer, DeepEC, ECPICK |

Target protein sequence (one-hot encoding) |

Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) |

|

ATGO+ |

Homologous sequences obtained by BLASTp search, target protein sequence features extracted using ESM protein language model |

Fully Connected Neural Network |

|

ProtBoost |

Target protein sequence (features extracted by Prot-T5 protein language model) |

Logistic Regression, Graph Convolutional Network (GCN), Gradient Boosted Trees |

|

DPFunc |

Target protein sequence (features extracted by ESM protein language model), Domain properties obtained via InterProScan (one-hot encoding, embedded representations) |

Transformer, Graph Convolutional Network (GCN) |

|

InterLabelGO+ |

Homologous sequences obtained via DIAMOND search; target protein sequence features extracted by ESM protein language model |

Fully Connected Neural Network |

|

DeepGO-SE |

Target protein sequence (features extracted from ESM protein language model), protein–protein interactions |

Fully Connected Neural Network |

|

DeepECtransformer |

Homologous sequences obtained via DIAMOND search; target protein sequences (features extracted using ESM protein language model) |

Attention Network |

|

CLEAN |

Target protein sequence (features extracted by ESM protein language model) |

Fully Connected Neural Network |

In recent years, the development of both template-based function prediction algorithms and de novo machine learning–based methods has been greatly facilitated by major breakthroughs in artificial intelligence, exemplified by AlphaFold and ChatGPT. For instance, the StarFunc algorithm utilizes protein structures predicted by AlphaFold2 as templates for function prediction, while Struct2Go and CLEAN-Contact directly employ AlphaFold2-predicted structures as training data to build structure-based function prediction models. In addition, the development of large language models (LLMs), such as ChatGPT, has also spurred advances in protein language models within bioinformatics, making models like ESM mainstream tools for extracting protein sequence representations.

2.2. Critical Assessment of Function Annotation (CAFA)

Given the large number of protein function prediction algorithms developed in recent years, an objective and fair assessment of their predictive accuracy is essential. To this end, the international Critical Assessment of Function Annotation (CAFA) was established, led by the teams of Iddo Friedberg at Iowa State University and Predrag Radivojac at Indiana University [60]. From CAFA1 (2010–2011) to CAFA5 (2023–2024), the competition has been held approximately every three years. The number of participating teams has steadily increased, from 30 teams in CAFA1 to 1625 teams in CAFA5. CAFA has thus become the premier competition in protein function prediction, analogous to the Critical Assessment of Structure Prediction (CASP) in protein structure prediction.

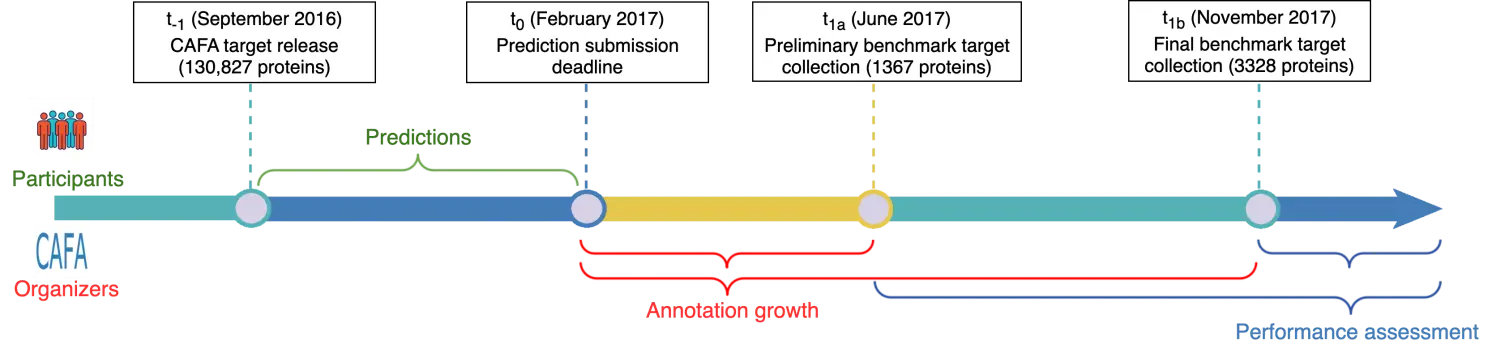

CAFA leverages the natural growth of functional annotations in the UniProt database. Taking CAFA3 (2016–2017) as an example [61] (Figure 3), the competition mechanism can be described as follows. During the preparation phase, organizers preselected 130,827 Swiss-Prot proteins from 23 model organisms and common microbes as CAFA3 target proteins, and publicly released this list on the competition start date (September 2016). Sixty-eight participating teams were required to predict GO terms for all 130,827 target proteins and submit their predictions to the organizers by the submission deadline (February 2017). Between the submission deadline and November 2017, UniProt Gene Ontology Annotation (UniProt GOA) added new experimentally supported GO annotations (evidence codes: EXP, IDA, IPI, IMP, IGI, IEP, HTP, HDA, HMP, HGI, HEP, TAS, IC) for 3328 of the target proteins. These 3328 proteins subsequently formed the benchmark test set used to evaluate the predictive accuracy of the submitted algorithms.

Figure 3. Timeline of CAFA3. A preliminary assessment for a subset of 1367 proteins with new annotations accumulated between t0 and t1a is performed to report results at the ISMB2017 conference. The final performance evaluation was performed on the full set of 3328 proteins with new annotations accumulated between t0 and t1b.

Among the protein function prediction algorithms mentioned above, BAR+ and MS-kNN ranked among the top performers in CAFA1 [60]; INGA and GoFDR were top-ranked in CAFA2 [62]; GOLabeler and COFACTOR achieved leading performance in CAFA3 [61]; NetGO2.0 ranked first in CAFA4; and GOCurator [63], PROTGOAT [64], StarFunc, and InterLabelGO were among the top performers in CAFA5.

2.3. Text Mining–Based Protein Function Prediction Algorithms

With the continued development of CAFA, the importance of text mining–based algorithms has become increasingly evident. These algorithms have also grown more sophisticated alongside advances in machine learning for natural language processing (NLP). For example, the top-ranked algorithm in CAFA1, Jones-UCL [65], employed a simple text mining approach: by counting word frequencies in Swiss-Prot description texts associated with proteins of different functions, a naïve Bayes model was constructed to predict GO terms. This early model did not use text from cited literature and relied solely on word frequencies, lacking contextual information, which imposed significant limitations.

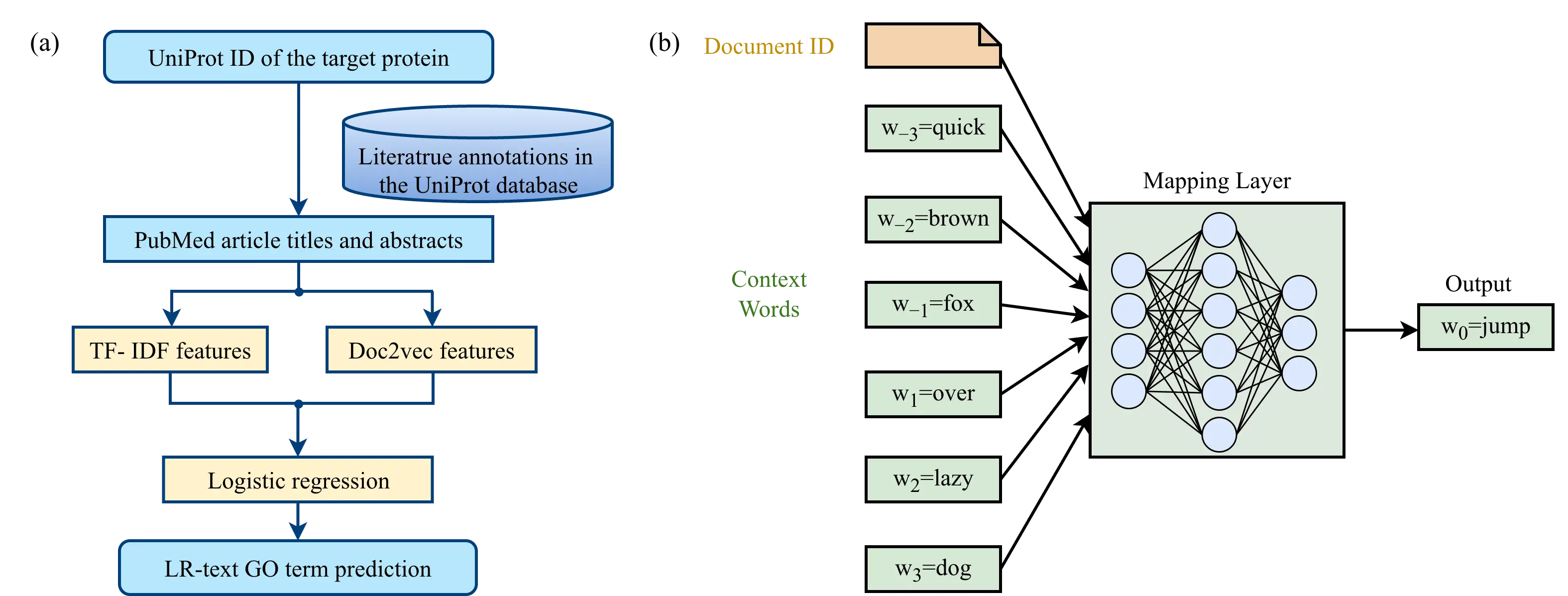

By contrast, text mining–based approaches in CAFA4 were substantially more advanced. For instance, the top-ranked algorithm NetGO2.0 [46], building upon its predecessors GOLabeler [42] and NetGO [45], introduced a new text mining–based prediction module, LR-Text (Figure 4a). This module was inspired by the earlier DeepText2GO approach [66] and operates as follows: the UniProt identifier of a query protein is used to retrieve associated PubMed IDs from the UniProt database. The corresponding titles and abstracts are then obtained from PubMed, and textual features are extracted using two methods. The first method is term frequency–inverse document frequency (TF-IDF), where for a term t in document d, the TF-IDF value is defined as:

Here, $${f}_{t, d}$$ denotes the frequency of term t in document d, N is the total number of documents in the corpus, and $${N}_{t}$$ is the number of documents containing term t. In addition to TF-IDF, NetGO2.0 also employs Doc2Vec [67] to extract textual features (Figure 4b). Doc2Vec is a neural network model that learns to represent each document as a fixed-length numerical vector, capturing the semantic meaning of the text. Conceptually, it can be thought of as assigning each document a “summary vector” that reflects the words and context in that document. During training, the model learns to predict a word in a document based on its surrounding words and the document identifier. Once trained, the model can transform any new document into a fixed-length vector, which can then be used as input features for downstream prediction tasks. When applied, providing the text of a PubMed document to the input layer allows the model to transform text of arbitrary length into fixed-length feature vectors at the mapping layer, enabling machine learning models to utilize textual information efficiently.

NetGO2.0 combines TF-IDF and Doc2Vec features into a unified text representation, which is then used to train a logistic regression model for GO prediction (Figure 4a). These GO predictions derived from text mining are further integrated with predictions obtained through five other approaches: BLASTp-based sequence similarity, three-residue fragment frequency, InterPro protein domain families, protein–protein interaction networks, and deep neural networks. A gradient boosted decision tree model is then applied to generate the final GO predictions.

Figure 4. Text mining-based protein GO term prediction in NetGO2.0. (a) LR-Text, the text mining model in NetGO2.0. (b) The architecture of Doc2Vec, which is used as one of the text feature generation methods in LR-Text. In this example, the Doc2Vec neural network model is trained to predict the masked word “jump” given its context in the sentence “The quick brown fox ___ over the lazy dog”. The word “the” is excluded from the input sentence as it does not have meaningful information.

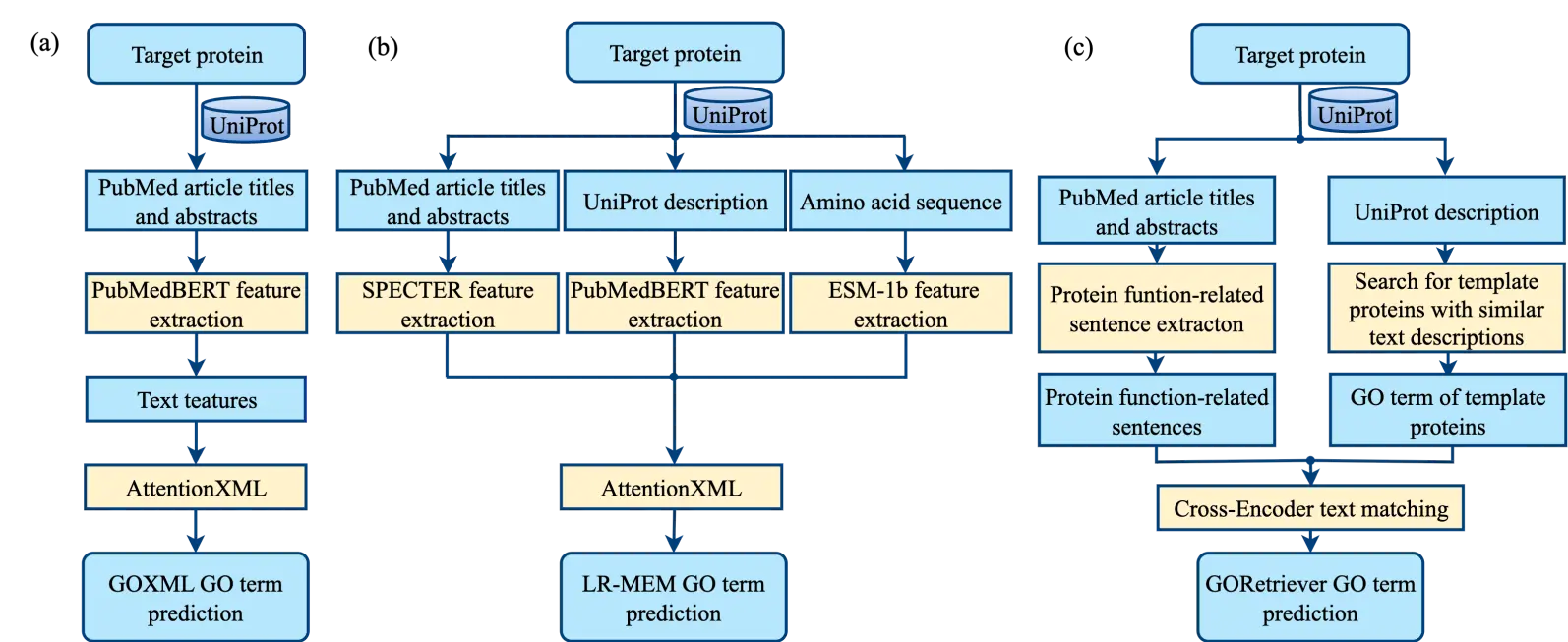

In CAFA5, the top-ranked and fourth-ranked methods, GOCurator [63] and PROTGOAT [64], also employed text mining approaches. Among them, PROTGOAT utilizes text mining in a relatively simple manner, relying solely on TF-IDF features derived from PubMed abstracts. In contrast, GOCurator represents a comprehensive integration of text mining strategies. It incorporates the LR-Text model from its predecessor NetGO2.0 and adds three additional text mining models: GOXML, LR-MEM, and GORetriever.

GOXML uses only the titles and abstracts of PubMed articles associated with the query protein as input and extracts textual features using the PubMedBERT large language model [68]. These features are then fed into the AttentionXML multi-label classification framework to predict multiple GO terms (Figure 5a) simultaneously.

LR-MEM integrates three types of features: PubMed titles and abstracts, the textual description of the query protein in UniProt, and the amino acid sequence. PubMed textual features are extracted using the document-level transformer model SPECTER [69]; UniProt textual descriptions are processed with PubMedBERT; and amino acid sequences are encoded using the ESM-1b protein language model [58]. The concatenated features are then input to a logistic regression model to generate final function predictions (Figure 5b). Both LR-Text, GOXML, and LR-MEM are template-free, de novo function prediction models.

The final model, GORetriever, leverages template protein information in combination with text mining (Figure 5c). GORetriever first extracts functionally relevant sentences from the PubMed titles and abstracts associated with the query protein. In parallel, it searches for template proteins in the training data with similar textual descriptions using the BM25 algorithm, based on the UniProt textual description of the query protein, retrieving both their GO annotations and corresponding GO descriptions. The functionally relevant sentences from the query protein and the GO descriptions from the template proteins are then compared using a Cross-Encoder [70] text-matching framework to generate the final GORetriever predictions. Conceptually, a Cross-Encoder is a neural network model that evaluates the semantic similarity between two pieces of text. Unlike simpler methods that encode texts separately, the Cross-Encoder considers the two texts together, allowing it to capture detailed interactions and context between the query and template sentences. The similarity scores generated by the Cross-Encoder are then used to rank potential GO terms and produce the final predictions for the query protein.

Figure 5. Three text mining-based models for protein GO term prediction in GOcurator. (a) LR-MEM. (b) GOXML. (c) GORetriever.

In addition to GO prediction [71], text mining has been employed to predict other types of protein functions, such as protein–protein interaction sites [72], Human Phenotype Ontology (HPO) terms [73], metabolic reactions [74], and functional sites [75].

3. Challenges in Text Mining–Based Function Prediction

Although text mining has demonstrated substantial utility in protein function prediction, particularly for GO prediction, as evidenced in CAFA, there remain several areas for improvement. In terms of literature data processing, current methods exhibit at least three major limitations: they typically consider only titles and abstracts while ignoring full-text articles; they rely entirely on literature annotations curated by UniProt database curators; and they lack automated classification of document types.

3.1. Ignoring Full-Text Articles

A scientific publication investigating the biological function of a protein or a set of proteins typically contains several sections, including the Title, Abstract, Introduction, Methods, Results, and Discussion and Conclusion. The Introduction often summarizes previous knowledge about the function of the target protein, the Results section provides detailed experimental or computational findings, and the Discussion and Conclusion may offer an overview of the protein’s function as well as inferences about additional potential functions. Despite the wealth of functional information contained in these sections, current text mining–based protein function prediction algorithms, including DeepText2Go, GORetriever, and GOAnnotator, almost exclusively process titles and abstracts from the PubMed database.

In practice, obtaining the full text corresponding to PubMed abstracts is becoming increasingly feasible. With the growth of the Open Access (OA) movement, more authors, either due to funding agency requirements or by free will, have made full texts available in repositories such as PubMed Central and Europe PMC, as well as on preprint platforms like bioRxiv and arXiv. For example, PubMed Central currently hosts approximately 10.5 million full-text articles, representing about 28% of all PubMed entries. Among the 8935 PubMed articles incorporated into UniProt in 2024, 65% (5772 articles) have full-text versions available in PubMed Central, indicating that most PubMed papers will likely have accessible full text in the near future. Furthermore, since 2004, PubMed Central has employed Optical Character Recognition (OCR) technology to convert approximately 1.46 million scanned articles from image-only formats into plain text, facilitating their processing by text mining tools. Consequently, leveraging full-text articles represents a promising direction for future text mining–based protein function prediction algorithms.

However, several practical challenges continue to limit large-scale full-text mining. First, many publishers restrict automated retrieval of full texts through subscription requirements, institutional login, IP verification, or CAPTCHA-based human verification, making the construction of a comprehensive full-text corpus technically and legally difficult. Second, some papers are available only in “green” open access formats in preprint servers (e.g., bioRxiv, medRxiv, and ResearchSquare), third-party repositories (e.g., ResearchGate), or the authors’ personal website. Associating the green open-access full texts with the final peer-reviewed versions from the publishers is not always trivial, due to changes in manuscript titles and authorship. Third, many journals and preprint servers provide full texts only as PDFs rather than structured XML or HTML, and PDF parsing remains error-prone due to multi-column layouts, OCR artifacts, and disrupted textual flow, complicating accurate extraction of protein-related evidence.

To address these challenges, several strategies can be considered. First, large-scale text mining efforts could prioritize Open Access repositories (e.g., PubMed Central, Europe PMC) and preprint servers that allow automated access and have clear licensing. Second, collaborations with publishers or participation in text and data mining (TDM) agreements can provide legal access to subscription-based content for research purposes. Third, the use of institutional proxy services or APIs provided by publishers can help overcome IP-based access restrictions in a compliant manner. Fourth, web crawlers and text alignment tools can be developed to identify green open-access full texts. Finally, when PDFs are unavoidable, employing advanced PDF parsing tools combined with post-processing methods, such as error correction and semantic filtering, can improve the quality of extracted protein function information.

Compared with text mining of abstracts, one major challenge in mining full-text articles is the sparsity of relevant information. Specifically, abstracts are typically limited to a few hundred words and are highly condensed summaries of the research, making it relatively straightforward for text mining tools to identify descriptions of the target protein’s function. In contrast, full-text articles often extend to several thousand or even tens of thousands of words, with direct descriptions of protein function frequently obscured by large amounts of irrelevant information, such as reagent vendors and functional hypothesis that are proved to be incorrect.

To extract relevant information from full texts, large language model–based chatbots, such as ChatGPT and DeepSeek, can offer assistance. For example, using instructions such as: “Summarize the biological functions of the protein discussed in the following text and propose Gene Ontology terms for its functions”, combined with the full-text content of the article, these models can generate concise overviews of protein functions.

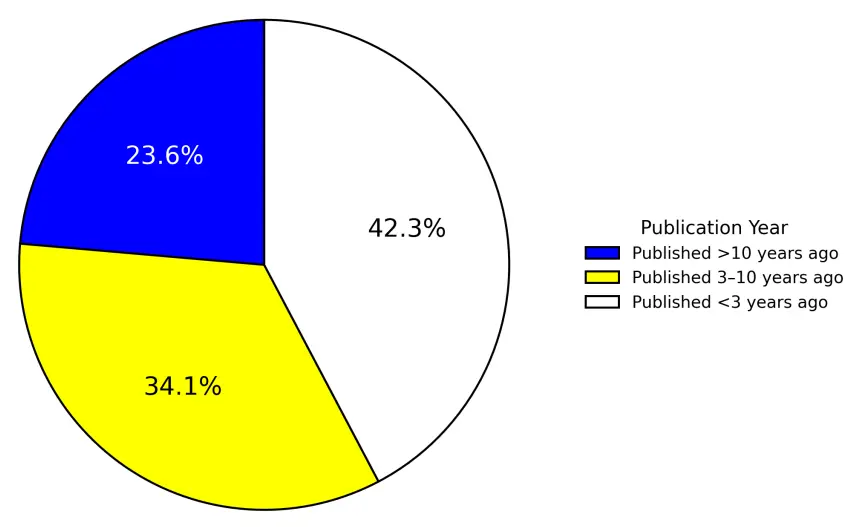

3.2. Reliance on UniProt Literature Annotations

Currently, nearly all text mining–based GO prediction algorithms source their textual data from PubMed articles annotated by the UniProt database for the target proteins. UniProt’s literature curation requires substantial human effort, and annotations are often not available immediately after a paper is published. For instance, by the end of 2024, UniProt had incorporated 444,251 articles, representing only about 1.2% of the entire PubMed database, including 8935 articles newly added in 2024. Among these newly added articles, 60% were published more than three years ago, and over a half were published more than ten years ago (Figure 6). These data indicate a clear lag in UniProt’s literature coverage. Consequently, text mining tools aiming to exploit published literature fully must be capable of precise indexing in PubMed and PubMed Central using keywords such as protein name, gene name, or species, rather than relying solely on UniProt’s literature annotations.

Identifying the proteins and species mentioned in an abstract or full text essentially corresponds to a Named Entity Recognition (NER) task in text mining, i.e., extracting entities with specific biological meaning from text (such as protein names, gene names, or species names). For example, in the sentence from a research article [76]: “As an endogenous inhibitor of neutrophil adhesion, EDIL3 plays a crucial role in inflammatory regulation”, the correct gene/protein entity recognition result would be: “As an endogenous inhibitor of neutrophil adhesion, [EDIL3] protein plays a crucial role in inflammatory regulation”.

A range of algorithms is available for protein and gene name recognition, including EXTRACT [77], PubTator [78], HunFlair [79], Saber [80], and OGER [81]. These tools can be effectively applied in text mining–based protein function annotation studies.

Figure 6. Year of publication for the 8935 PubMed citations newly added to UniProt in 2024. The 549 papers published in or before the year 1999 are not shown. Papers published more than ten years ago, published more than three years ago but less than ten years, and published less than three years ago are colored blue, yellow, and white, respectively.

3.3. Lack of Automated Classification Methods for Noisy Literature

Literature coverage is generally sparse because only a small fraction of proteins, primarily from model organisms, have been experimentally characterized. For example, among the 175,990 PubMed abstracts associated with at least one UniProt protein in UniProt-GOA version 224,132,906 (75.51%) are associated with 14 well-studied model organisms—such as Homo sapiens, Mus musculus, Drosophila melanogaster, Caenorhabditis elegans, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Escherichia coli, and Arabidopsis thaliana—among 3756 species collected by UniProt-GOA in total. This makes text mining-based function annotation less generalizable to poorly studied proteins and species compared to methods that rely on sequence and structure. Even when a publication exists for a protein, it may not always be informative for function inference.

A single publication related to a target protein may report diverse types of studies, including low-throughput functional experiments, structural analyses, computational predictions, high-throughput experiments, reviews, or methodological developments. The contribution of each publication type to protein function prediction clearly varies. An experimental paper may describe only partial aspects of protein function, high-throughput studies may report hundreds of proteins with limited individual validation, and many papers mention proteins incidentally. For example, many publications on G protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) mention T4 lysozyme, whose fusion enables successful crystallography of GPCRs, without further functional insights on the lysozyme itself. Meanwhile, some papers focus on methodological innovations rather than the proteins themselves. For example, the UniProt database used to cite a single publication (PubMed: 21873635) [8] for all GO annotations with the IBA evidence code, leading to as many as 1,174,413 UniProt proteins referencing this paper until the citation was corrected in 2024. Such sparse and noisy coverage limits the amount of reliable information available for automated function prediction and poses challenges for text-mining approaches.

Overall, such sparse and noisy coverage limits the reliability of automated function prediction and poses challenges for text-mining approaches. One approach to partially mitigate the noisiness of literature is to develop an automated literature classification algorithm. Such an algorithm, which classifies scientific publications into basic types and automatically weights them according to their relevance, would be highly beneficial for downstream text mining applications.

3.4. Dilemmas in Benchmarking and Evaluation

The objective evaluation of text mining–based protein function prediction systems remains an enduring challenge that complicates fair comparisons and methodological progress. Unlike sequence-based or structure-based models, where ground truth can often be derived from experimentally validated annotations, text mining approaches rely heavily on human-curated databases such as UniProt or Gene Ontology Annotation as benchmarks. However, these databases are themselves incomplete and continuously evolving, meaning that the absence of a recorded annotation does not imply the absence of function. This structural bias leads to inflated false-negative rates and a systematic underestimation of a model’s true recall, particularly for newly discovered or poorly characterized proteins that are underrepresented in current databases. As a result, benchmarking outcomes may reflect the maturity of database curation rather than the intrinsic capability of a prediction algorithm.

Another source of complexity arises from the limitations of conventional performance metrics. Commonly used indicators, such as precision, recall, and F1-score, while statistically convenient, fail to capture the biological and scientific value of predictions. A metric capable of proposing a novel, mechanistically plausible function for a previously unannotated protein contributes more to biological discovery than one that merely reproduces well-established annotations. Yet this distinction is often obscured when predictions are aggregated into global metrics. Furthermore, since text-derived functional hypotheses may precede experimental validation, a metric’s innovative capacity may only be recognized retrospectively, underscoring the temporal and epistemic limitations of static benchmarking frameworks.

As the field moves toward multi-modal and integrative prediction paradigms, disentangling the specific contribution of text-based evidence from that of complementary modalities—such as sequence similarity, structural modeling, or protein–protein interaction networks—becomes increasingly difficult. Hybrid systems often achieve superior predictive accuracy, but this improvement may stem from synergistic effects rather than the text component alone. Thus, the future of benchmarking must evolve beyond static test sets and fixed metrics. It should incorporate dynamic evaluation schemes that consider temporal updates in biological databases, contextual weighting of evidence types, and the capacity to quantify both predictive accuracy and biological novelty. Only through such refined and adaptive evaluation frameworks can the true potential of text mining in protein function prediction be fairly assessed.

3.5. Multi-Modal Integration

While text mining has been widely used for automated protein function annotation, relying solely on literature-derived information poses significant limitations. Protein function is inherently multi-faceted, encompassing aspects such as molecular activity, cellular localization, involvement in biological processes, and interactions with other biomolecules. These aspects are often reported across diverse data types, including protein sequences, three-dimensional structures, post-translational modifications, protein-protein interaction networks, expression profiles, and phenotypic datasets. Text-based annotation methods, even when leveraging advanced natural language processing techniques, are inherently constrained to information explicitly described in the literature. As a result, they may miss functional signals present in experimental datasets that are not well documented in publications, especially for less-studied proteins or non-model organisms, or only documented as free-format supplementary that are usually not processed by text mining.

Integrating multi-modal data presents several challenges. First, different data types vary in scale, resolution, and reliability—for example, high-throughput experimental measurements may contain noise, while structural predictions may vary greatly in accuracy among different proteins. Second, the representation of these heterogeneous data sources must be harmonized for computational models, often requiring complex embedding strategies or graph-based frameworks. Third, combining modalities introduces the risk of conflicting evidence, which must be reconciled to avoid misleading predictions. Therefore, developing algorithms capable of effectively integrating textual, structural, sequence, and network-based evidence is critical for producing accurate and comprehensive protein function annotations. Addressing multi-modal integration will expand coverage, improve confidence in predictions, and enable the functional annotation of proteins for which literature evidence is sparse or ambiguous.

4. Conclusions and Outlook

The release of ChatGPT and AlphaFold2 marks the entry of life sciences into the era of artificial intelligence, and the field of protein function prediction is no exception. Text mining represents a key application of AI models in protein function prediction. From early statistical models based on Naïve Bayes, to classic neural networks leveraging Doc2Vec, and more recently to deep learning models built on the BERT architecture, text mining–based protein function prediction algorithms have evolved from simple to complex frameworks, fully exploiting advances in natural language processing. The recent CAFA5 challenge further highlights the dominant role of text mining in protein function prediction.

In the future, text mining algorithms for function prediction will increasingly leverage cutting-edge AI models, such as large language model–based chatbots, to better utilize full-text information, achieve more automated and comprehensive literature retrieval, and enable automated classification and weighting of different types of publications, thereby improving the accuracy of functional predictions. Moreover, advanced feature aggregation strategies, such as singular pooling [82]—which integrates singular values and eigenvectors to preserve semantic structure in textual embeddings better—may be explored to enhance the representation of protein-related information extracted from literature or template proteins, further improving downstream prediction performance. The development of such algorithms will also support the classification of publications in databases such as PubMed and facilitate the linking of scientific articles to corresponding proteins in UniProt, ensuring that manual functional annotation in UniProt can be completed efficiently and in a timely manner.

As technology advances, future text mining algorithms will go beyond literature retrieval, classification, and functional annotation, reaching the level of deeper semantic understanding. For example, by integrating knowledge graph techniques, algorithms could automatically construct multi-dimensional networks linking proteins with diseases, phenotypes, drug metabolism, and more, providing richer contextual information for protein function prediction. Additionally, multi-modal learning approaches will become increasingly important, enabling algorithms to integrate textual data with experimental data, such as next-generation sequencing and mass spectrometry, to comprehensively understand a protein’s functional mechanisms and its interactions with other proteins. These approaches will also allow functional inference for poorly characterized proteins by leveraging contextual information from homologous sequences, model organisms, and integrated datasets across species.

At the application level, these advanced text mining algorithms will greatly accelerate drug discovery and personalized medicine. By automatically analyzing the wealth of biological function descriptions and small molecule–protein interaction data in the literature, these algorithms can provide researchers with targeted drug screening suggestions and predict drug pharmacology, side effects, and efficacy. Furthermore, such algorithms can support the construction of dynamically updated protein function databases, providing researchers with real-time, precise protein function annotation services. They may also enable the identification of previously unrecognized functional relationships or signaling pathways, guiding experimental design and high-throughput screens.

Moreover, with the widespread adoption of AI technologies, future text mining algorithms will place greater emphasis on user-friendliness and interpretability. For instance, interactive visualization tools could allow researchers to directly inspect the evidence supporting algorithmic predictions, thereby enhancing understanding of the underlying mechanisms of protein function and the biochemical contexts required for these functions. This transparency will enhance trust in automated predictions and facilitate the integration of AI-assisted annotations into experimental workflows.

Looking further ahead, self-supervised learning and continual learning paradigms are likely to play an increasingly important role. Algorithms could continuously update their models as new publications and experimental data become available, reducing lag between scientific discovery and functional annotation. Cross-species knowledge transfer and multi-organism data integration will further enable the prediction of protein function for poorly studied species. Additionally, AI-driven hypothesis generation could suggest novel experiments, effectively creating a closed loop between computational predictions and laboratory validation, accelerating both fundamental biology and translational research.

In summary, with ongoing advances in artificial intelligence, text mining–based protein function prediction algorithms are poised to play an increasingly important role, not only driving the advancement of life science research but also bringing transformative breakthroughs for human health and disease treatment.

Statement of the Use of Generative AI and AI-Assisted Technologies in the Writing Process

During the preparation of this manuscript, the author(s) used ChatGPT in order to to ameliorate the grammar, syntax and organization of the main text. After using this tool/service, the author(s) reviewed and edited the content as needed and take(s) full responsibility for the content of the published article.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Xiaoqiong Wei for insightful discussions. With the editor’s permission, this review is partly based on a review written in Chinese by the author previously published in the Synthetic Biology Journal [83]. The current review is not a mere translation of the Chinese version of the review, but rather includes novel discussions on challenges in text mining–based function prediction; all figures have been redrawn to reflect new contents as well.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.Z.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, H.W.; Writing—Review & Editing, C.Z.; Visualization, H.W. and C.Z.; Supervision, C.Z.; Funding Acquisition, C.Z.

Ethics Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The source code to generate Figure 2 is available at https://github.com/kad-ecoli/uniprot_figure, accessed on 28 September 2025.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2025YFA0923600 to CZ).

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

-

Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, Botstein D, Butler H, Cherry JM, et al. Gene ontology: Tool for the unification of biology. Nat. Genet. 2000, 25, 25–29. doi:10.1038/75556. [Google Scholar]

-

International Union of Biochemistry. Enzyme Nomenclature, 1978: Recommendations of the Nomenclature Committee of the International Union of Biochemistry on the Nomenclature and Classification of Enzymes; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

-

Talapova P, Gargano M, Matentzoglu N, Coleman B, Addo-Lartey E, Anagnostopoulos A, et al. The Human Phenotype Ontology in 2024: Phenotypes around the world. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, D1333–D1346. doi:10.1093/nar/gkad1005. [Google Scholar]

-

The UniProt Consortium. UniProt: The universal protein knowledgebase in 2025. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, D609–D617. doi:10.1093/nar/gkae1010. [Google Scholar]

-

Huntley RP, Sawford T, Mutowo-Meullenet P, Shypitsyna A, Bonilla C, Martin MJ, et al. The GOA database: Gene ontology annotation updates for 2015. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, D1057–D1063. doi:10.1093/nar/gku1113. [Google Scholar]

-

Feldmann P, Eicher EN, Leevers SJ, Hafen E, Hughes DA. Control of growth and differentiation by Drosophila RasGAP, a homolog of p120 ras–GTPase-activating protein. Mol. Cell Biol. 1999, 19, 1928–1937. doi:10.1128/MCB.19.3.1928. [Google Scholar]

-

Hutchison CA, III, Chuang R-Y, Noskov VN, Assad-Garcia N, Deerinck TJ, Ellisman MH, et al. Design and synthesis of a minimal bacterial genome. Science 2016, 351, aad6253. doi:10.1126/science.aad6253. [Google Scholar]

-

Gaudet P, Livstone MS, Lewis SE, Thomas PD. Phylogenetic-based propagation of functional annotations within the Gene Ontology consortium. Brief. Bioinform. 2011, 12, 449–462. doi:10.1093/bib/bbr042. [Google Scholar]

-

Wei X, Zhang C, Freddolino L, Zhang Y. Detecting Gene Ontology misannotations using taxon-specific rate ratio comparisons. Bioinformatics 2020, 36, 4383–4388. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btaa548. [Google Scholar]

-

Martin DM, Berriman M, Barton GJ. GOtcha: A new method for prediction of protein function assessed by the annotation of seven genomes. BMC Bioinform. 2004, 5, 178. doi:10.1186/1471-2105-5-178. [Google Scholar]

-

Conesa A, Götz S. Blast2GO: A comprehensive suite for functional analysis in plant genomics. Int. J. Plant Genom. 2008, 2008, 619832. doi:10.1155/2008/619832. [Google Scholar]

-

Piovesan D, Luigi Martelli P, Fariselli P, Zauli A, Rossi I, Casadio R. BAR-PLUS: The Bologna Annotation Resource Plus for functional and structural annotation of protein sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 39, W197–W202. doi:10.1093/nar/gkr292. [Google Scholar]

-

Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schäffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, et al. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: A new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997, 25, 3389–3402. doi:10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [Google Scholar]

-

Wass MN, Sternberg MJ. ConFunc—Functional annotation in the twilight zone. Bioinformatics 2008, 24, 798–806. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btn037. [Google Scholar]

-

Hawkins T, Chitale M, Luban S, Kihara D. PFP: Automated prediction of gene ontology functional annotations with confidence scores using protein sequence data. Proteins 2009, 74, 566–582. doi:10.1002/prot.22172. [Google Scholar]

-

Gong Q, Ning W, Tian W. GoFDR: A sequence alignment based method for predicting protein functions. Methods 2016, 93, 3–14. doi:10.1016/j.ymeth.2015.08.009. [Google Scholar]

-

Mahlich Y, Steinegger M, Rost B, Bromberg Y. HFSP: High speed homology-driven function annotation of proteins. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, i304–i312. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/bty262. [Google Scholar]

-

Steinegger M, Söding J. MMseqs2 enables sensitive protein sequence searching for the analysis of massive data sets. Nat. Biotechnol. 2017, 35, 1026–1028. doi:10.1038/nbt.3988. [Google Scholar]

-

Kulmanov M, Hoehndorf R. DeepGOPlus: Improved protein function prediction from sequence. Bioinformatics 2020, 36, 422–429. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btz595. [Google Scholar]

-

Kulmanov M, Hoehndorf R. DeepGOZero: Improving protein function prediction from sequence and zero-shot learning based on ontology axioms. Bioinformatics 2022, 38, i238–i245. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btac256. [Google Scholar]

-

Yuan Q, Xie J, Xie J, Zhao H, Yang Y. Fast and accurate protein function prediction from sequence through pretrained language model and homology-based label diffusion. Brief. Bioinform. 2023, 24, bbad117. doi:10.1093/bib/bbad117. [Google Scholar]

-

Buchfink B, Reuter K, Drost H-G. Sensitive protein alignments at tree-of-life scale using DIAMOND. Nature Methods 2021, 18, 366–368. doi:10.1038/s41592-021-01101-x. [Google Scholar]

-

Zhang C, Freddolino L. A large-scale assessment of sequence database search tools for homology-based protein function prediction. Brief. Bioinform. 2024, 25, bbae349. doi:10.1093/bib/bbae349. [Google Scholar]

-

Zhang C, Freddolino L, Zhang Y. COFACTOR: Improved protein function prediction by combining structure, sequence and protein–protein interaction information. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, W291–W299. doi:10.1093/nar/gkx366. [Google Scholar]

-

Zhang C, Zheng W, Freddolino L, Zhang Y. MetaGO: Predicting Gene Ontology of non-homologous proteins through low-resolution protein structure prediction and protein–protein network mapping. J. Mol. Biol. 2018, 430, 2256–2265. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2018.03.004. [Google Scholar]

-

Zhang Y, Skolnick J. TM-align: A protein structure alignment algorithm based on the TM-score. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005, 33, 2302–2309. doi:10.1093/nar/gki524. [Google Scholar]

-

Zhang C, Zhang X, Freddolino L, Zhang Y. BioLiP2: An updated structure database for biologically relevant ligand–protein interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, D404–D412. doi:10.1093/nar/gkad630. [Google Scholar]

-

Laskowski RA. The ProFunc function prediction server. In Protein Function Prediction: Methods and Protocols; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 75–95. [Google Scholar]

-

Krissinel E, Henrick K. Secondary-structure matching (SSM), a new tool for fast protein structure alignment in three dimensions. Biol. Crystallogr. 2004, 60, 2256–2268. doi:10.1107/S0907444904026460. [Google Scholar]

-

Barker JA, Thornton JM. An algorithm for constraint-based structural template matching: Application to 3D templates with statistical analysis. Bioinformatics 2003, 19, 1644–1649. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btg226. [Google Scholar]

-

Zhang C, Liu Q, Freddolino L. StarFunc: Fusing template-based and deep learning approaches for accurate protein function prediction. bioRxiv 2024. doi:10.1101/2024.05.15.594113. [Google Scholar]

-

Van Kempen M, Kim SS, Tumescheit C, Mirdita M, Lee J, Gilchrist CL, et al. Fast and accurate protein structure search with Foldseek. Nat. Biotechnol. 2024, 42, 243–246. doi:10.1038/s41587-023-01773-0. [Google Scholar]

-

Varadi M, Anyango S, Deshpande M, Nair S, Natassia C, Yordanova G, et al. AlphaFold Protein Structure Database: Massively expanding the structural coverage of protein-sequence space with high-accuracy models. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, D439–D444. doi:10.1093/nar/gkab1061. [Google Scholar]

-

Mistry J, Chuguransky S, Williams L, Qureshi M, Salazar GA, Sonnhammer EL, et al. Pfam: The protein families database in 2021. Nucleic Acids Res 2021, 49, D412–D419. doi:10.1093/nar/gkaa913. [Google Scholar]

-

Liu Q, Zhang C, Freddolino L. InterLabelGO+: Unraveling label correlations in protein function prediction. Bioinformatics 2024, 40, btae655. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btae655. [Google Scholar]

-

Gligorijević V, Renfrew PD, Kosciolek T, Leman JK, Berenberg D, Vatanen T, et al. Structure-based protein function prediction using graph convolutional networks. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 3168. doi:10.1038/s41467-021-23303-9. [Google Scholar]

-

Ma W, Zhang S, Li Z, Jiang M, Wang S, Lu W, et al. Enhancing protein function prediction performance by utilizing AlphaFold-predicted protein structures. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2022, 62, 4008–4017. doi:10.1021/acs.jcim.2c00885. [Google Scholar]

-

Qiu X-Y, Wu H, Shao J. TALE-cmap: Protein function prediction based on a TALE-based architecture and the structure information from contact map. Comput. Biol. Med. 2022, 149, 105938. doi:10.1016/j.compbiomed.2022.105938. [Google Scholar]

-

Yang Y, Jerger A, Feng S, Wang Z, Brasfield C, Cheung MS, et al. Improved enzyme functional annotation prediction using contrastive learning with structural inference. Commun. Biol. 2024, 7, 1690. doi:10.1038/s42003-024-07359-z. [Google Scholar]

-

Lan L, Djuric N, Guo Y, Vucetic S. MS-kNN: Protein function prediction by integrating multiple data sources. BMC Bioinform. 2013, 14, S8. doi:10.1186/1471-2105-14-S3-S8. [Google Scholar]

-

Piovesan D, Tosatto SC. INGA 2.0: Improving protein function prediction for the dark proteome. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, W373–W378. doi:10.1093/nar/gkz375. [Google Scholar]

-

You R, Zhang Z, Xiong Y, Sun F, Mamitsuka H, Zhu S. GOLabeler: Improving sequence-based large-scale protein function prediction by learning to rank. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, 2465–2473. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/bty130. [Google Scholar]

-

Blum M, Chang H-Y, Chuguransky S, Grego T, Kandasaamy S, Mitchell A, et al. The InterPro protein families and domains database: 20 years on. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, D344–D354. doi:10.1093/nar/gkaa977. [Google Scholar]

-

Chen T, Guestrin C. Xgboost: A Scalable Tree Boosting System. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 August 2016. [Google Scholar]

-

You R, Yao S, Xiong Y, Huang X, Sun F, Mamitsuka H, et al. NetGO: Improving large-scale protein function prediction with massive network information. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, W379–W387. doi:10.1093/nar/gkz388. [Google Scholar]

-

Yao S, You R, Wang S, Xiong Y, Huang X, Zhu S. NetGO 2.0: Improving large-scale protein function prediction with massive sequence, text, domain, family and network information. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, W469–W475. doi:10.1093/nar/gkab398. [Google Scholar]

-

Kulmanov M, Khan MA, Hoehndorf R. DeepGO: Predicting protein functions from sequence and interactions using a deep ontology-aware classifier. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, 660–668. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btx624. [Google Scholar]

-

Sanderson T, Bileschi ML, Belanger D, Colwell LJ. ProteInfer, deep neural networks for protein functional inference. Elife 2023, 12, e80942. doi:10.7554/eLife.80942. [Google Scholar]

-

Ryu JY, Kim HU, Lee SY. Deep learning enables high-quality and high-throughput prediction of enzyme commission numbers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 13996–14001. doi:10.1073/pnas.1821905116. [Google Scholar]

-

Han S-R, Park M, Kosaraju S, Lee J, Lee H, Lee JH, et al. Evidential deep learning for trustworthy prediction of enzyme commission number. Brief. Bioinform. 2024, 25, bbad401. doi:10.1093/bib/bbad401. [Google Scholar]

-

Zhu Y-H, Zhang C, Yu D-J, Zhang Y. Integrating unsupervised language model with triplet neural networks for protein gene ontology prediction. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2022, 18, e1010793. doi:10.1371/journal.pcbi.1010793. [Google Scholar]

-

Kulmanov M, Guzmán-Vega FJ, Roggli PD, Lane L, Arold ST, Hoehndorf R. Deepgo-se: Protein function prediction as approximate semantic entailment. bioRxiv 2023. doi:10.1101/2023.09.26.559473. [Google Scholar]

-

Chervov A, Vakhrushev A, Fironov S, Martignetti L. ProtBoost: Protein function prediction with Py-Boost and Graph Neural Networks—CAFA5 top2 solution. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2412.04529. [Google Scholar]

-

Wang W, Shuai Y, Zeng M, Fan W, Li M. DPFunc: Accurately predicting protein function via deep learning with domain-guided structure information. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 70. doi:10.1038/s41467-024-54816-8. [Google Scholar]

-

Kim GB, Kim JY, Lee JA, Norsigian CJ, Palsson BO, Lee SY. Functional annotation of enzyme-encoding genes using deep learning with transformer layers. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 7370. doi:10.1038/s41467-023-43216-z. [Google Scholar]

-

Yu T, Cui H, Li JC, Luo Y, Jiang G, Zhao H. Enzyme function prediction using contrastive learning. Science 2023, 379, 1358–1363. doi:10.1126/science.adf2465. [Google Scholar]

-

Vaswani A, Shazeer N, Parmar N, Uszkoreit J, Jones L, Gomez AN, et al. Attention is all you need. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 30. doi:10.48550/arXiv.1706.03762. [Google Scholar]

-

Lin Z, Akin H, Rao R, Hie B, Zhu Z, Lu W, et al. Evolutionary-scale prediction of atomic-level protein structure with a language model. Science 2023, 379, 1123–1130. doi:10.1126/science.ade2574. [Google Scholar]

-

Elnaggar A, Heinzinger M, Dallago C, Rehawi G, Wang Y, Jones L, et al. Prottrans: Toward understanding the language of life through self-supervised learning. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2021, 44, 7112–7127. doi:10.1109/TPAMI.2021.3095381. [Google Scholar]

-

Radivojac P, Clark WT, Oron TR, Schnoes AM, Wittkop T, Sokolov A, et al. A large-scale evaluation of computational protein function prediction. Nat. Methods 2013, 10, 221–227. doi:10.1038/nmeth.2340. [Google Scholar]

-

Zhou N, Jiang Y, Bergquist TR, Lee AJ, Kacsoh BZ, Crocker AW, et al. The CAFA challenge reports improved protein function prediction and new functional annotations for hundreds of genes through experimental screens. Genome Biol. 2019, 20, 244. doi:10.1186/s13059-019-1835-8. [Google Scholar]

-

Jiang Y, Oron TR, Clark WT, Bankapur AR, D’Andrea D, Lepore R, et al. An expanded evaluation of protein function prediction methods shows an improvement in accuracy. Genome Biol. 2016, 17, 184. doi:10.1186/s13059-016-1037-6. [Google Scholar]

-

Yan H, Wang S, Liu H, Mamitsuka H, Zhu S. GORetriever: Reranking protein-description-based GO candidates by literature-driven deep information retrieval for protein function annotation. Bioinformatics 2024, 40, ii53–ii61. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btae401. [Google Scholar]

-

Chua ZM, Rajesh A, Sinha S, Adams PD. PROTGOAT: Improved automated protein function predictions using Protein Language Models. bioRxiv 2024. doi:10.1101/2024.04.01.587572. [Google Scholar]

-

Cozzetto D, Buchan DW, Bryson K, Jones DT. Protein function prediction by massive integration of evolutionary analyses and multiple data sources. BMC Bioinform. 2013, 14, S1. doi:10.1186/1471-2105-14-S3-S1. [Google Scholar]

-

You R, Huang X, Zhu S. DeepText2GO: Improving large-scale protein function prediction with deep semantic text representation. Methods 2018, 145, 82–90. doi:10.1016/j.ymeth.2018.05.026. [Google Scholar]

-

Le Q, Mikolov T. Distributed Representations of Sentences and Documents. In Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on International Conference on Machine Learning, Beijing, China, 21–26 June 2014. [Google Scholar]

-

Gu Y, Tinn R, Cheng H, Lucas M, Usuyama N, Liu X, et al. Domain-specific language model pretraining for biomedical natural language processing. ACM Trans. Comput. Healthc. 2021, 3, 1–23. doi:10.1145/3458754. [Google Scholar]

-

Cohan A, Feldman S, Beltagy I, Downey D, Weld DS. Specter: Document-level representation learning using citation-informed transformers. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2004.07180. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2004.07180. [Google Scholar]

-

Reimers N, Gurevych I. Sentence-bert: Sentence embeddings using siamese bert-networks. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1908.10084. doi:10.48550/arXiv.1908.10084. [Google Scholar]

-

Wu J, Yin Q, Zhang C, Geng J, Wu H, Hu H, et al. Function Prediction for G Protein-Coupled Receptors through Text Mining and Induction Matrix Completion. ACS Omega 2019, 4, 3045–3054. doi:10.1021/acsomega.8b02454. [Google Scholar]

-

Badal VD, Kundrotas PJ, Vakser IA. Text mining for protein docking. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2015, 11, e1004630. doi:10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004630. [Google Scholar]

-

Kafkas Ş, Hoehndorf R. Ontology based text mining of gene-phenotype associations: Application to candidate gene prediction. Database 2019, 2019, baz019. doi:10.1093/database/baz019. [Google Scholar]

-

Czarnecki J, Nobeli I, Smith AM, Shepherd AJ. A text-mining system for extracting metabolic reactions from full-text articles. BMC Bioinform. 2012, 13, 172. doi:10.1186/1471-2105-13-172. [Google Scholar]

-

Verspoor KM, Cohn JD, Ravikumar KE, Wall ME. Text mining improves prediction of protein functional sites. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e32171. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0032171. [Google Scholar]

-

Wei X, Zou S, Xie Z, Wang Z, Huang N, Cen Z, et al. EDIL3 deficiency ameliorates adverse cardiac remodelling by neutrophil extracellular traps (NET)-mediated macrophage polarization. Cardiovasc. Res. 2022, 118, 2179–2195. doi:10.1093/cvr/cvab269. [Google Scholar]

-

Pafilis E, Buttigieg PL, Ferrell B, Pereira E, Schnetzer J, Arvanitidis C, et al. EXTRACT: Interactive extraction of environment metadata and term suggestion for metagenomic sample annotation. Database 2016, 2016, baw005. doi:10.1093/database/baw005. [Google Scholar]

-

Wei C-H, Kao H-Y, Lu Z. PubTator: A web-based text mining tool for assisting biocuration. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, W518–W522. doi:10.1093/nar/gkt441. [Google Scholar]

-

Weber L, Sänger M, Münchmeyer J, Habibi M, Leser U, Akbik A. HunFlair: An easy-to-use tool for state-of-the-art biomedical named entity recognition. Bioinformatics 2021, 37, 2792–2794. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btab042. [Google Scholar]

-

Giorgi JM, Bader GD. Towards reliable named entity recognition in the biomedical domain. Bioinformatics 2020, 36, 280–286. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btz504. [Google Scholar]

-

Furrer L, Jancso A, Colic N, Rinaldi F. OGER++: Hybrid multi-type entity recognition. J. Cheminform 2019, 11, 7. doi:10.1186/s13321-018-0326-3. [Google Scholar]

-

Zhu S, Cai J, Xiong R, Zheng L, Ma D. Singular pooling: A spectral pooling paradigm for second-trimester prenatal level II ultrasound standard fetal plane identification. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2025, 35, 12508–12523. doi:10.1109/TCSVT.2025.3588395. [Google Scholar]

-

Zhang C. Challenges and opportunities in text mining-based protein function annotation. Synth. Biol. J. 2025, 6, 603–606. doi:10.12211/2096-8280.2025-002. [Google Scholar]