Antiviral Pharmaceuticals as Emerging Environmental Contaminants: Occurrence, Ecotoxicological Risks, and Photocatalytic Remediation Pathways

Received: 01 September 2025 Revised: 22 October 2025 Accepted: 11 December 2025 Published: 24 December 2025

© 2025 The authors. This is an open access article under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

1. Introduction

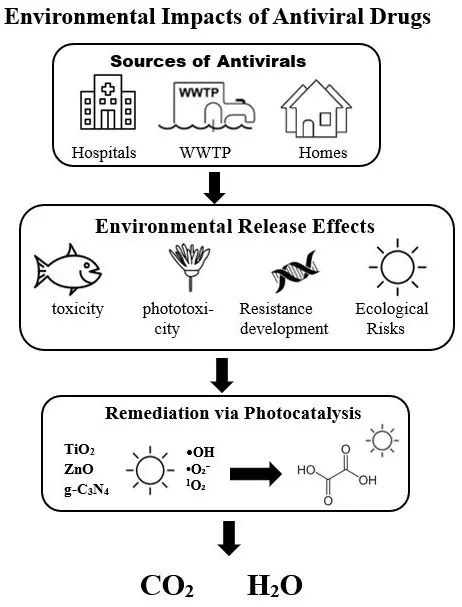

Pharmaceuticals are increasingly recognized as a major class of emerging contaminants due to their continuous release into the environment and their potential adverse impacts on ecosystems and human health [1,2,3,4,5]. While antibiotics and other therapeutic classes such as analgesics and hormones have been extensively studied, antiviral pharmaceuticals remain comparatively neglected, despite their unprecedented global consumption during and after the COVID-19 pandemic [6,7,8,9,10]. Compounds such as favipiravir, remdesivir, molnupiravir, and oseltamivir carboxylate have been frequently detected in hospital effluents, municipal wastewater, and surface waters worldwide [11,12,13,14,15]. Recent monitoring campaigns have even reported antiviral residues in treated wastewater at concentrations reaching the μg/L level, raising significant concerns regarding persistence, bioactivity, and ecological risks [16,17].

Unlike conventional pollutants, antivirals are specifically designed to be biologically active at low concentrations. Their high polarity, structural persistence, and poor biodegradability contribute to incomplete removal in conventional wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs), enabling their continuous discharge into aquatic environments [18,19,20]. This persistence has been linked to ecotoxicological risks, including oxidative stress in algae, impaired reproduction in aquatic invertebrates, developmental toxicity in fish embryos, and disruption of microbial communities [6,21,22]. More critically, residual antivirals may act as selective agents, potentially driving both antiviral and antimicrobial resistance in viral reservoirs and microbial populations, a ‘silent risk’ that has been increasingly emphasized as an overlooked consequence of pandemic-driven antiviral use [23,24,25,26,27].

To mitigate these risks, researchers have investigated a variety of remediation technologies. Conventional approaches such as adsorption, chlorination, and ozonation often achieve partial removal but generate potentially toxic transformation products [28,29,30,31]. In contrast, advanced oxidation processes (AOPs)—particularly semiconductor photocatalysis—have emerged as highly effective strategies for degrading persistent pharmaceuticals [32,33,34,35,36]. As a review article, this work provides a comprehensive synthesis of the occurrence, ecotoxicological risks, and photocatalytic remediation of antiviral pharmaceuticals, integrating environmental monitoring with mechanistic insights and computational modeling. Photocatalytic systems based on TiO2, ZnO, and g-C3N4 have demonstrated significant activity under UV and visible light, while modifications such as metal doping, heterojunction engineering, and carbon-based nanocomposites have further enhanced charge separation efficiency and solar-light responsiveness [17,35,36,37,38,39]. Recent experimental evidence has confirmed efficient photocatalytic degradation of antivirals such as favipiravir, remdesivir, and lopinavir under simulated solar irradiation [40,41,42,43,44].

Despite these advances, comprehensive reviews focusing specifically on antiviral pharmaceuticals as emerging contaminants remain scarce. Most existing reviews have broadly considered pharmaceuticals as a single category, thereby overlooking the unique structural features, persistence, and ecotoxicological risks of antivirals [9,10,20,45,46]. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first dedicated review that systematically evaluates antiviral pharmaceuticals as environmental contaminants. By focusing exclusively on antivirals, this work critically synthesizes their occurrence, ecological risks, and photocatalytic remediation pathways, while placing special emphasis on mechanistic insights supported by density functional theory (DFT), molecular modeling, and machine learning [9,47,48,49].

2. Occurrence and Fate of Antiviral Drugs

Antiviral pharmaceuticals have been increasingly detected in hospital effluents, wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs), and surface waters, particularly since the COVID-19 pandemic [13,14,15,50]. Reported concentrations typically range from ng/L to μg/L, with some studies documenting exceptionally high levels, such as efavirenz up to 34,000 ng/L in municipal effluents [10,16]. The widespread occurrence of these drugs reflects both incomplete human metabolism and insufficient removal during conventional wastewater treatment [18,20,51].

These compounds are often characterized by high polarity and limited biodegradability, which enhances their persistence and mobility in aquatic environments [9,10,52]. Transformation products (TPs) formed during treatment processes—including chlorination, ozonation, and biological degradation—may be equally or even more toxic than the parent compounds [30,31,53,54,55]. Seasonal variations, influenced by infection waves and prescription patterns, further contribute to fluctuating concentrations, with higher loads typically observed during winter flu seasons and pandemic surges [20,45,56].

Geographical variability has also been reported, with elevated concentrations documented in densely populated regions and in countries with extensive antiviral prescription policies [13,14,15,57]. Studies in Europe, Asia, and North America have highlighted the ubiquitous presence of oseltamivir, favipiravir, and remdesivir in surface waters and effluents [9,14,15,58]. Moreover, recent monitoring programs have revealed that treated wastewater remains a significant pathway for the release of antivirals into rivers, lakes, and even coastal waters [16,18,20,55].

The environmental persistence of antivirals is further compounded by their resistance to biodegradation in activated sludge and membrane bioreactors [10,59,60]. Sorption onto sludge is generally low because of their hydrophilicity and ionizable functional groups, increasing their potential for long-range transport in aquatic systems [26,52]. On a regional scale, longitudinal monitoring campaigns in municipal effluents, surface waters, and, in some cases, groundwater have revealed pronounced spatial and temporal heterogeneity in antiviral loads, with winter- and pandemic-driven peaks superimposed on background contamination levels [2,9,13,15,20,29,34,45,50,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68]. Complementary studies reporting antivirals in rivers, lakes, reservoirs, and estuarine or coastal receiving waters further indicate that treated wastewater and combined sewer overflows remain important pathways for downstream dissemination beyond the immediate vicinity of WWTP outfalls [69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81]. Taken together, this body of evidence highlights the need for coordinated, multi-matrix monitoring strategies that explicitly resolve spatial, seasonal, and hydrological variability, rather than relying solely on short-term or single-site sampling campaigns.

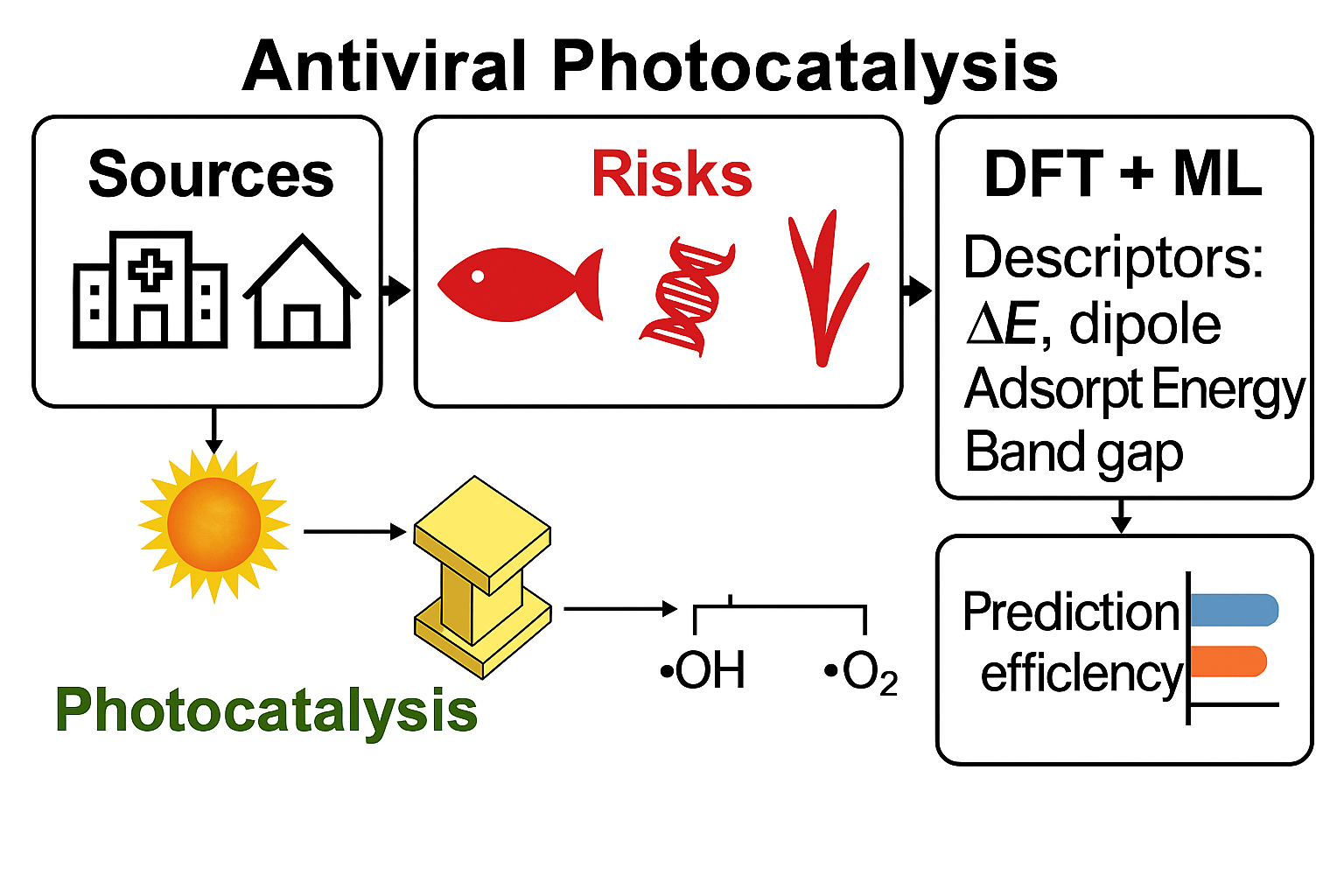

As illustrated in Figure 1, the overall sources, environmental release pathways, and associated ecotoxicological and resistance-related risks of antiviral pharmaceuticals are summarized schematically, together with potential photocatalytic remediation strategies. Representative reported concentrations of selected antiviral drugs in different water matrices worldwide are compiled in Table 1, underscoring the dual threat of direct ecological harm and indirect public health implications. This dual dimension reinforces the need to expand ecotoxicological testing beyond a limited set of standard model organisms and to systematically investigate how chronic, low-level antiviral exposure might contribute to resistance evolution in environmental viral reservoirs and host-associated microbiomes. These potential pathways—linking emission, transport, exposure, and selection—are schematically integrated in Figure 1 which synthesizes mechanistic and monitoring evidence from recent studies [9,10,26,46,79,80,81].

Figure 1. Conceptual pathway showing sources, environmental release effects, and photocatalytic remediation of antiviral drugs, culminating in mineralization to CO2 and H2O (This work).

Table 1. Reported concentrations of representative antiviral drugs in various aquatic matrices (wastewater influents and effluents, surface waters, and groundwater), highlighting spatial and temporal variations across global monitoring studies.

|

Antiviral Drug |

Water Matrix |

Reported Concentration Range |

Location/References |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Favipiravir |

Hospital effluents, WWTP influent |

120–950 ng/L |

|

|

Remdesivir |

Municipal wastewater, surface water |

40–320 ng/L |

|

|

Molnupiravir |

WWTP effluent, river water |

15–180 ng/L |

|

|

Oseltamivir carboxylate |

Surface waters, treated effluents |

80–1100 ng/L |

|

|

Efavirenz |

Municipal wastewater effluent |

up to 34,000 ng/L |

South Africa [9] |

3. Ecotoxicological Risks and Resistance Concerns

Emerging experimental evidence highlights the ecotoxicological risks posed by antiviral pharmaceuticals in aquatic ecosystems. Laboratory studies have reported oxidative stress responses in primary producers, impaired reproduction and survival in cladocerans such as Daphnia magna, and developmental toxicity in fish embryos when exposed to environmentally relevant concentrations of selected antivirals, covering ng/L–µg/L levels [53,54,56,67,68]. Although the strong polarity of most antivirals limits their classical bioaccumulation potential, their continuous discharge into surface waters ensures chronic low-level exposure, raising concerns about subtle but persistent alterations in community structure and ecosystem functioning over extended timescales [57,58,69].

Transformation products (TPs) generated during disinfection and advanced oxidation processes may further amplify these risks, as several studies have shown that specific TPs exhibit toxicity comparable to, or even higher than, that of their parent drugs towards algae, invertebrates, and fish early-life stages [26,31,55,59,79]. Under realistic exposure scenarios, such mixtures of parent compounds and TPs can simultaneously affect multiple trophic levels, from primary producers to invertebrate grazers and higher consumers, thereby perturbing food web interactions and energy transfer in receiving waters [59,62,63,64]. These findings underscore the need to consider both parent antivirals and their transformation products in hazard characterization and environmental risk assessment frameworks.

Beyond direct toxicity, a critical concern is the potential of antiviral residues to act as selective agents for resistance development in environmental compartments. While antimicrobial resistance has been extensively investigated in the context of antibiotics, antiviral resistance driven by chronic exposure to sub-inhibitory concentrations in aquatic systems remains comparatively underexplored [26,74,75]. Conceptually, persistent lw-level contamination can maintain prolonged contact between circulating antiviral residues, environmental viral reservoirs, and host-associated microbiota, creating conditions that may favor the selection and spread of resistant variants. Recent experimental and modelling studies have begun to address this gap, suggesting that exposure of animal reservoirs and viral hosts to sub-lethal antiviral concentrations could contribute to the emergence and amplification of resistant viral strains, with significant implications for preparedness in future pandemics [23,27,63,64,76,77,78].

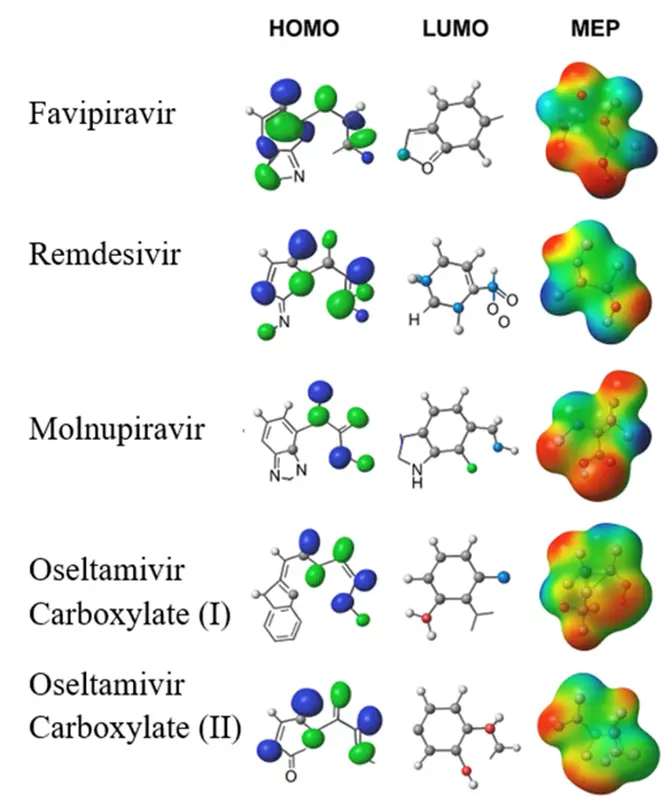

To gain deeper insights into the electronic properties and reactivity patterns of the selected antiviral drugs, frontier molecular orbitals (HOMO–LUMO) and molecular electrostatic potential (MEP) surfaces were computed at the DFT/B3LYP/6-31G(d,p) level of theory. The HOMO distributions highlight the electron-donating regions, while the LUMO maps indicate the potential electron-accepting sites, thereby elucidating the main reactive centers of the molecules. In parallel, MEP surfaces provide a visualization of the molecular charge distribution, with red regions corresponding to electron-rich (nucleophilic) sites and blue regions denoting electron-deficient (electrophilic) domains. Such electronic descriptors have been widely employed in previous DFT-based studies on pharmaceuticals and related environmental contaminants to rationalize sorption, degradation, and interaction tendencies with biomolecular targets and solid surfaces [70,71,72,73,82,83,84,85]. In the present work, they provide a complementary mechanistic basis for interpreting the observed photocatalytic degradation behavior and potential ecotoxicological interactions of favipiravir, remdesivir, molnupiravir, and oseltamivir carboxylate, whose HOMO, LUMO, and MEP maps are visualized in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO), lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO), and molecular electrostatic potential (MEP) maps of representative antiviral drugs (favipiravir, remdesivir, molnupiravir, and oseltamivir carboxylate I–II) computed at the B3LYP/6-31G(d,p) level. Color scale: red = electron-rich, blue = electron-poor. Adapted from [85,86,87,88,89] with modifications; see Section 3 for computational details.

Two structural variants of oseltamivir carboxylate (designated as I and II) were included in the DFT analysis to reflect potential transformation products and tautomeric forms reported under environmental and oxidative conditions. Oseltamivir carboxylate is the active metabolite of oseltamivir, but in aquatic environments it can undergo further hydroxylation, bond cleavage, or tautomerization, leading to the formation of distinct species that differ in stability and electronic distribution [52,55,90,91]. The HOMO–LUMO and MEP maps (Figure 3) clearly show differences in frontier orbital localization and charge density between forms I and II, indicating possible variations in their susceptibility to reactive oxygen species (ROS) attack and photocatalytic degradation efficiency. Considering multiple structural variants thus provides a more realistic representation of the environmental transformation pathways of oseltamivir carboxylate and their ecotoxicological relevance [81].

Figure 3. Representative microstructures and performance features of antiviral photocatalyst families: (a) SEM/TEM nanostructure; (b) photocatalytic removal under UV/visible light; (c) XRD pattern; (d) cycling stability; (e) UV–vis spectra; (f) kinetic comparison; (g) band alignment; (h) surface mechanism on a carbon-rich support; (i) defect/dopant states extending light absorption. Panels were compiled and redrawn from representative literature on TiO2, ZnO, g-C3N4, and related hybrids [35,36,92,93]; experimental parameters are provided in the text. Error bars represent standard deviations from triplicate runs.

4. Conventional Treatment Approaches

Activated sludge (or membrane bioreactors), filtration, and final disinfection generally achieve limited removal of antiviral pharmaceuticals due to their polarity, persistence, and low sorption to sludge [34,60,94,95]. Reported overall removal efficiencies frequently remain below ~50%, with several antivirals passing essentially unchanged to receiving waters [29,66,96,97,98].

Adsorption (PAC/GAC). Powdered and granular activated carbon can partially remove selected antivirals; however, performance is highly compound-dependent and weakened by hydrophilicity (low Kow), competition from natural organic matter, and shortened breakthrough times [99,100,101,102]. Regeneration and disposal of spent carbon introduce additional operational and environmental burdens [29,66,103].

Coagulation–flocculation. Conventional coagulants (e.g., alum, Fe salts) show poor affinity for most antivirals because charge neutralization and sweep flocculation target colloids rather than dissolved, polar micropollutants; removals are typically marginal [104,105].

Biological processes (CAS/MBR). Given the poor biodegradability of many antivirals and their limited sorption to activated sludge, removals in conventional activated sludge (CAS) and even in membrane bioreactors (MBR) are often low or erratic [106,107,108,109]. Apparent ‘negative removal’ can occur when conjugated metabolites are deconjugated back to the parent compound during treatment [65,110,111,112,113].

Disinfection and oxidation (chlorination/ozonation). While free chlorine and ozone may reduce parent-compound concentrations, they frequently generate transformation products (TPs)—including halogenated and partially oxidized moieties—that can exhibit equal or higher toxicity and greater persistence than the parents [36,114,115]. Consequently, the apparent disappearance of the parent antiviral does not necessarily equate to risk reduction [116].

Membrane separations (UF/NF/RO). Ultrafiltration provides negligible direct removal of truly dissolved antivirals, whereas nanofiltration and reverse osmosis achieve high rejections for many species [105]. However, concentrate (brine) management, energy demand, and fouling control remain key barriers to large-scale adoption in municipal settings [117].

Nature-based/tertiary polishing. Bank filtration, constructed wetlands, and sand filtration can attenuate some antivirals, but performance is variable and strongly influenced by hydraulics, redox, temperature, and background organic load; robust, consistent removal is uncommon without an advanced oxidation step [118].

Implication. Collectively, these constraints explain the recurrent detection of antivirals in WWTP effluents and surface waters, and they justify the pivot toward solar-driven advanced oxidation—notably heterogeneous photocatalysis—as a more sustainable route for antiviral abatement. The reported removal efficiencies of representative antiviral drugs in conventional wastewater treatment processes are summarized in Table 2 [108,109].

Table 2. Reported removal efficiencies of selected antiviral pharmaceuticals in conventional wastewater treatment processes (primary, secondary, and tertiary stages), highlighting variability across treatment technologies and operational conditions.

|

Antiviral Drug |

Treatment Process |

Reported Removal Efficiency (%) |

Notes/References |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Favipiravir |

Activated sludge |

<20% |

Poor biodegradability [22] |

|

Remdesivir |

Coagulation–flocculation |

25–40% |

Partial removal, significant residual [24] |

|

Molnupiravir |

Conventional WWTP |

~30% |

Detected in effluents [25] |

|

Oseltamivir carboxylate |

Activated sludge |

0–15% |

Highly persistent, passes unchanged [25] |

|

Mixed antivirals |

Chlorination |

40–60% |

Formation of toxic transformation products [28] |

|

Mixed antivirals |

Ozonation |

50–70% |

Higher removal but toxic by-products [28] |

Beyond these conventional and nature-based treatment options, several recent advances in wastewater treatment technologies reported in 2024–2025 are directly relevant to antiviral removal. Emerging hybrid systems that couple biological processes with advanced oxidation (e.g., photocatalysis, electro-oxidation, or peroxymonosulfate activation) have shown improved robustness toward polar, poorly biodegradable pharmaceuticals, while mitigating the formation of persistent transformation products. In parallel, next-generation membrane configurations and biofilm-based reactors with tailored hydrodynamics and surface functionalities have been developed to enhance retention of antiviral residues and to facilitate downstream AOP polishing. Recent studies [119,120,121] illustrate how integrated treatment trains can outperform stand-alone conventional units, particularly under variable loading conditions and complex water matrices. These developments underscore that future antiviral mitigation strategies will likely rely on rationally designed hybrid systems, in which advanced oxidation processes, including heterogeneous photocatalysis, are embedded as key polishing steps rather than isolated add-ons.

5. Advanced Photocatalytic Remediation

Photocatalytic degradation has emerged as one of the most promising advanced oxidation processes (AOPs) for the abatement of persistent antiviral drugs. Semiconductor-based photocatalysts, particularly TiO2, ZnO, and g-C3N4, as well as their modified composites, have demonstrated strong oxidative potential under UV and solar irradiation [35]. Modification strategies, including metal/non-metal doping, heterojunction construction, and hybridization with carbonaceous nanomaterials, have further expanded visible-light responsiveness and enhanced charge carrier separation [36].

Recent advances in photocatalyst design have accelerated rapidly in 2024–2025, driven by the emergence of engineered heterostructures, plasmon-enhanced systems, vacancy-rich oxides, and MOF-derived photocatalysts. As highlighted in the latest progress reports—including the 2025 article in Chinese Journal of Catalysis [30,31,46,74,75,76,77,78,79,109,115,116,122,123]—state-of-the-art materials increasingly rely on synergistic strategies that couple band-structure modulation with interfacial charge-migration engineering and selective surface-reaction pathways. These developments include S-scheme and Z-scheme architectures, plasmonic Ag/Au hybrids, dual-defect TiO2 and ZnO systems, and high-surface-area catalysts derived from metal–organic frameworks, all of which show enhanced visible-light harvesting and more efficient reactive-oxygen-species (ROS) generation. Incorporating these recent innovations strengthens the conceptual framework of this review and positions antiviral photocatalysis within the broader landscape of rapidly advancing materials-science research.

Beyond heterogeneous photocatalysis, recent years have seen rapid advancements in the broader family of advanced oxidation processes (AOPs) that are increasingly relevant for antiviral degradation. Sulfate-radical-based

AOPs, particularly those driven by peroxymonosulfate (PMS) and peroxydisulfate (PDS) activation, have demonstrated high reactivity toward persistent pharmaceutical structures due to the strong oxidative potential of SO4•− radicals. Hybrid systems that combine photocatalysis with PMS/PDS activation, electrochemical oxidation, or sonophotocatalysis have further expanded the operational window by enhancing radical generation and improving degradation selectivity. Recent studies [124,125] illustrate that integrated AOP configurations can outperform single-process treatments, especially under variable water chemistry, high background load, and complex organic matrices. Introducing these developments situates heterogeneous photocatalysis within the rapidly evolving AOP landscape and highlights the complementary role of multi-radical and multi-energy-input oxidation pathways in antiviral removal.

To provide a design-oriented map of antiviral photocatalysis, we categorize state-of-the-art materials into oxide semiconductors (TiO2, ZnO), polymeric carbon nitrides (g-C3N4), plasmonic hybrids (Ag, Au), vacancy-engineered/doped oxides, carbon-based heterostructures (rGO, CNT), MOF-derived/LDH frameworks, and emerging perovskites and Bi-based oxides. For each family, we briefly summarize electronic structure (band gap, band positions), prevalent microstructures (nanotubes, nanosheets, mesoporous spheres), and antiviral performance envelopes under UV/visible/solar flux, followed by key advantages/limitations relevant to real water matrices (scavengers, NOM, ions) and scale-up (stability, toxicity, cost). A compact comparison is given in Table 3.

Short sub-blocks (examples you can paste under subtitles):

-

-

Plasmonic Hybrids (Ag, Au):

Localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) extends visible-light harvesting and can boost hot-electron injection into adjacent semiconductors. Advantages: strong visible response, improved charge separation, broad spectral activation. Limitations: noble-metal cost, potential ion leaching (Ag+), and stability under chlorinated matrices. Typical microstructures: Ag/TiO2 core–shells, Au-decorated g-C3N4 sheets. Representative antiviral tests show accelerated inactivation via ROS amplification under λ > 420 nm.

-

-

Vacancy-Engineered/Doped Oxides:

Oxygen-vacancy–rich TiO2 or ZnO and anion/cation-doped variants tune band edges and create defect states that facilitate photoabsorption and charge mobility. Advantages: low cost, scalable, robust. Limitations: defect overpopulation can increase recombination; defect chemistry must be stabilized against aging. Microstructures: black TiO2 nanotubes, N-doped porous ZnO.

-

-

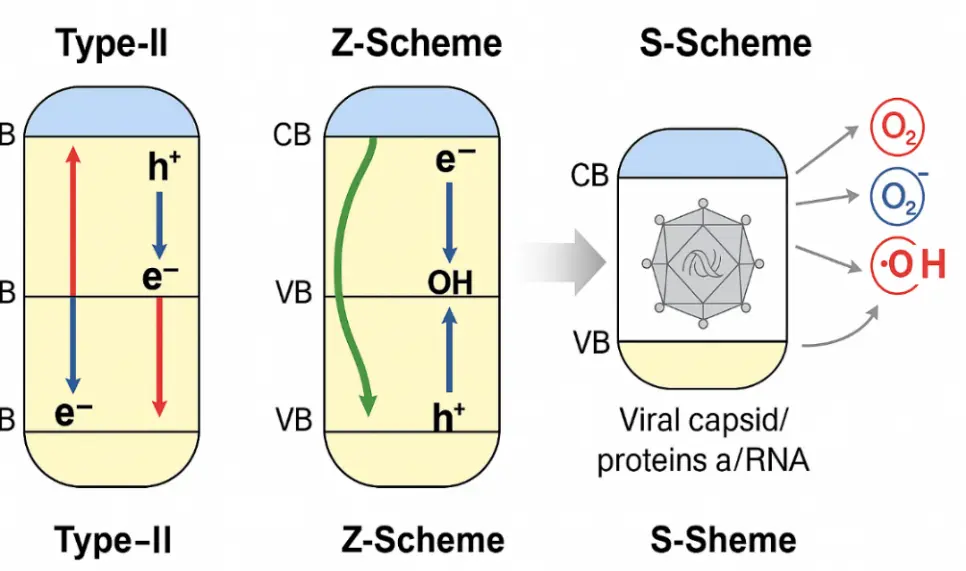

Heterojunctions (Type-II, Z-scheme, S-scheme):

Rational band alignment aids directional charge transfer; Z- and S-schemes preserve strong redox potentials. Advantages: superior e−/h+ separation, retained redox power. Limitations: interface engineering and reproducibility; interfacial resistance. Microstructures: TiO2/g-C3N4, BiVO4/g-C3N4, rGO-bridged Z-schemes.

-

-

Carbon-Based Hybrids (rGO, CNT):

Provide high conductivity/adsorptivity; facilitate π–π interactions with aromatic moieties in antivirals, enriching interfacial concentration. Advantages: charge shuttling, pollutant preconcentration. Limitations: aggregation, possible ecotoxicity if released, and the need for immobilization.

-

-

MOF-Derived & LDHs:

MOF-to-oxide/carbon conversions yield hierarchical porosity; LDHs offer tunable composition and basic sites. Advantages: large surface area, tailored active sites. Limitations: hydrolytic stability (some MOFs), synthesis cost; immobilization strategies recommended.

-

-

Perovskites & Bi-Based Oxides:

Visible-light-active systems with strong oxidation capacity. Advantages: solar activation, promising kinetics. Limitations: ion migration/lead content for some halide perovskites; durability in aqueous matrices must be verified. Representative microstructures and performance snapshots are shown in Figure 3.

Table 3. Representative photocatalyst families for antiviral degradation: light-response window, key strengths, and typical limitations.

|

Category |

Light-Response/ |

Key Strengths |

Typical Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

|

TiO2 (anatase/rutile) |

~3.0–3.2 eV (UV) |

Chemically inert; non-toxic; abundant; mature know-how |

Mostly UV-active unless modified; e−/h+ recombination; immobilization/scale-up needs |

|

ZnO |

~3.2–3.3 eV (UV) |

High activity; simple synthesis; good electron mobility |

Photocorrosion in aqueous media; stability over recycling |

|

g-C3N4 (bulk/meso/nanosheets) |

~2.6–2.8 eV (visible) |

Metal-free; visible-light response; easy N-doping |

Fast charge recombination; modest surface area unless engineered |

|

Doped oxides (metal: Fe, Cu, Ag; non-metal: N, S, B) |

UV–visible (mid-gap states) |

Extended absorption; improved charge separation |

Dopant leaching/aging; reproducibility and batch variability |

|

Z-scheme/S-scheme heterojunctions (e.g., TiO2/g-C3N4, ZnO/C-materials) |

Broad UV–visible |

Vectorial charge transfer while preserving strong redox potentials |

Interface engineering complexity; composite scale-up |

|

Plasmonic hybrids (Au/TiO2, Ag/AgX, Ag/rGO/TiO2) |

Visible–NIR (LSPR) |

Hot-electron injection; enhanced sunlight harvesting |

Noble-metal cost; long-term stability (sintering/oxidation) |

|

Carbonaceous & biochar-based (rGO, CNTs, biochar/g-C3N4) |

Visible (π–π* tail) |

High conductivity; adsorption–activation synergy; low cost (biochar) |

Heterogeneity; active-site normalization and fouling |

|

MOF-derived/MXene-supported |

Tunable (structure-dependent) |

Very high surface area; designer interfaces/band alignment |

Hydrolytic stability (some MOFs); synthesis cost and scalability |

* LSPR: localized surface plasmon resonance; rGO: reduced graphene oxide; CNTs: carbon nanotubes; MXene: two-dimensional transition metal carbides/nitrides.

5.1. TiO2-Based Photocatalysts

To align TiO2, ZnO, and g-C3N4 systems with the design-oriented framework introduced at the beginning of Section 5, the discussion of each photocatalyst family is now embedded within broader structural and mechanistic principles. TiO2 is examined as a prototypical wide-band-gap oxide whose performance can be tuned through doping, defect engineering, and heterojunction coupling—strategies consistent with the conceptual map of charge-management and band-alignment. Similarly, ZnO is analyzed within the context of vacancy-rich oxides and S-scheme/Z-scheme interfaces that improve stability and suppress photocorrosion. g-C3N4, as a visible-light-active polymeric semiconductor, is discussed through the lens of morphology engineering, heterostructure formation, and carbon-based hybridization, all of which correspond to the catalyst-family categories outlined earlier. By embedding these subsections within the overarching design principles, TiO2-, ZnO-, and g-C3N4-based photocatalysts are no longer presented as isolated examples but as representative embodiments of the strategies that govern antiviral photocatalysis.

Beyond aqueous-phase kinetics, interfacial pathways on TiO2 can diverge markedly due to site-specific adsorption geometries, local hydration, and the identity of electron acceptors. For instance, catechol photodecay on Degussa P25 at the air–solid interface proceeds with water vapor acting as an electron acceptor, yielding kinetics and product distributions distinct from bulk suspensions [126]. Recognizing such interface-driven reactivity is essential for designing immobilized photocatalyst architectures and filter systems for water and air remediation.

Titanium dioxide (TiO2) remains the benchmark photocatalyst owing to its stability, non-toxicity, and oxidative power [114]. However, its wide band gap (~3.2 eV) restricts activity to UV light, which represents only ~5% of the solar spectrum [115]. Recent studies reported efficient degradation of favipiravir, lopinavir, and oseltamivir in UV/TiO2 systems, with hydroxyl radicals (•OH) identified as the dominant reactive species [44,127,128].

To overcome UV limitations, dye sensitization and noble-metal deposition (Ag, Au, Pt) have been used to enhance visible-light absorption and reduce electron–hole recombination [116]. Heterojunctions such as TiO2/g-C3N4 and TiO2/graphene have also shown improved carrier separation, resulting in higher antiviral degradation efficiencies under solar light [129,130].

5.2. ZnO-Based Photocatalysts

Zinc oxide (ZnO) exhibits a band gap similar to TiO2 but offers higher quantum efficiency under UV illumination [131]. Rapid photocatalytic degradation of remdesivir and oseltamivir in ZnO suspensions has been demonstrated [132,133,134]. However, ZnO is prone to photocorrosion, which reduces its stability and reusability [131,132].

Strategies to improve ZnO stability include surface coating, hybridization with carbon materials, and coupling with TiO2 or g-C3N4 to form heterojunctions [129,133]. These modifications have significantly improved visible-light utilization and long-term durability in antiviral removal [38].

5.3. g-C3N4 and Composites

Graphitic carbon nitride (g-C3N4) has emerged as a promising metal-free photocatalyst with a narrow band gap (~2.7 eV), enabling visible-light harvesting [42]. Morphology engineering (nanosheets, mesoporous structures) and coupling with conductive carbons (graphene, CNTs) have enhanced its activity [134].

Modified g-C3N4 composites achieved complete removal of favipiravir within 60 min under simulated solar light, with ROS such as •O2− and 1O2 confirmed as key oxidants [42,135]. Despite this promise, pristine g-C3N4 suffers from electron–hole recombination, which has driven recent focus on doping and heterojunctions [136,137].

5.4. Metal Doping and Heterojunction Engineering

Metal doping (e.g., Fe, Ag, Cu) has been used to introduce mid-gap states, enabling visible-light absorption and improving charge separation [136,138]. Heterojunction photocatalysts such as TiO2/g-C3N4, ZnO/graphene, and multi-junction composites have demonstrated higher degradation efficiencies against molnupiravir and favipiravir [130,139].

Z-scheme and S-scheme heterojunctions further facilitate vectorial charge transfer, suppressing recombination and enabling high solar-driven antiviral degradation [137,140]. These systems often outperform single-component catalysts by combining complementary band structures. The photocatalytic degradation efficiencies of representative antiviral drugs under different catalyst systems, along with the transformation by-products identified, are summarized in Table 4 [130,139].

A growing body of work demonstrates that composite photocatalysts—particularly engineered heterojunctions and multi-component oxide–carbon hybrids—offer superior antiviral degradation performance compared to single-component materials. Recent studies [141,142] highlight how S-scheme and dual-defect heterostructures optimize spatial charge separation while preserving high redox potentials, leading to substantially enhanced generation of •OH and •O2− radicals under solar irradiation. These composite architectures integrate complementary functionalities, including defect-rich TiO2 domains, plasmonically active Ag/Au nanoparticles, and conductive carbonaceous scaffolds that facilitate electron shuttling and pollutant pre-concentration. Collectively, these studies demonstrate that composite photocatalysts outperform their parent materials not only in degradation efficiency but also in stability, recyclability, and resistance to scavenger species present in real water matrices. Incorporating these insights into the review strengthens the mechanistic understanding of how structural integration governs photocatalytic antiviral removal.

Table 4. Summary of reported photocatalytic degradation efficiencies of representative antiviral drugs using different catalyst systems, highlighting variations in catalyst composition, light source, and operational conditions.

|

Antiviral Drug |

Photocatalyst System |

Light Source |

Removal Efficiency (%) |

By-Products Identified |

References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Favipiravir |

TiO2 (anatase) |

UV lamp |

80–95% (60–120 min) |

Hydroxylated intermediates |

[44] |

|

Favipiravir |

UV/H2O2 AOP |

UV lamp |

>95% (60 min) |

Low-molecular acids |

[110] |

|

Remdesivir |

ZnO nanoparticles |

UV lamp |

70–85% (90 min) |

Partial oxidation products |

|

|

Molnupiravir |

g-C3N4 nanosheets |

Simulated solar |

85–92% (120 min) |

Ring-opened derivatives |

|

|

Oseltamivir carboxylate |

Fe-doped g-C3N4 |

Visible/solar |

>95% (60 min) |

Cleavage of ester/amide bonds |

|

|

Mixed antivirals |

TiO2/g-C3N4 heterojunction |

Solar simulator |

90–98% (60–90 min) |

Hydroxylated intermediates |

|

|

Mixed antivirals |

Carbon–g-C3N4 composites |

Visible light |

85–95% (90 min) |

Minor organic acids |

5.5. Carbon-Based and Biochar-Derived Materials

Carbonaceous nanomaterials—including graphene, CNTs, and biochar—are increasingly integrated with semiconductors to enhance conductivity, pollutant adsorption, and ROS generation [92,143]. Biochar-derived composites in particular offer sustainability and low cost, making them attractive for real wastewater treatment [143].

Recent reports show that biochar/g-C3N4 and graphene–TiO2 hybrids achieved superior favipiravir and remdesivir removal under natural sunlight, demonstrating the potential of green, scalable materials in photocatalytic remediation The photocatalytic degradation pathway of favipiravir, involving ROS generation, intermediate products, and final mineralization to CO2 and H2O, is schematically illustrated in Figure 4 [42,43,44,93,127,129].

Figure 4. Proposed photocatalytic degradation pathway of favipiravir under solar (simulated) irradiation. The stepwise transformation sequence was constructed by integrating intermediates and mechanistic features reported in previous photocatalytic studies on favipiravir and structurally related antiviral compounds [42,43,44,93,127,129]. Arrows indicate reactive oxygen species (ROS)-mediated steps (•OH, O2•−, h+), including initial hydroxylation and oxidative attack on the heterocyclic ring, subsequent ring-opening and decarboxylation reactions, and the formation of low-molecular-weight carboxylic-acid intermediates en route to final mineralization to CO2 and H2O. ROS, reactive oxygen species.

5.6. Standardization of Photocatalytic Reporting Metrics

A persistent limitation across the photocatalysis literature is the inconsistent reporting of experimental parameters, which hinders reproducibility and prevents meaningful comparison between studies. To address this, standardized reporting practices must be adopted for antiviral degradation experiments. Essential parameters include:

- (1)

-

Light-source characterization, including spectral power distribution, irradiance (mW·cm−2), and, when possible, incident photon flux or actinometric calibration;

- (2)

-

Catalyst dosage normalized to surface area (m2·L−1) rather than mass alone, to enable comparison between materials with different morphologies;

- (3)

-

Reactor geometry and hydrodynamics, including optical path length, mixing conditions, and suspension opacity;

- (4)

-

Quantified ROS production and electron–hole recombination indicators; and

- (5)

-

Kinetic reporting using intrinsic metrics, such as apparent quantum yield (AQY), internal quantum efficiency (IQE), and initial reaction rates.

Failure to report these parameters leads to misleading degradation percentages that cannot be translated or compared across studies. Given the rapidly expanding field of antiviral photocatalysis, implementing such reporting standards is essential for establishing robust structure–performance relationships, validating computational predictions, and guiding photocatalyst design toward realistic environmental applications.

6. Mechanistic Insights and DFT/ML Modeling

Antiviral inactivation in photocatalysis proceeds through a synergy between interfacial adsorption, selective photoexcitation, charge-carrier separation, and reactive oxygen species (ROS) chemistry. To bridge materials, mechanisms, and performance, we (i) map band alignments for type-II, Z-scheme, and S-scheme systems; (ii) outline DFT adsorption motifs and qualitative ΔEads trends for representative antiviral pharmacophores on oxide and carbonaceous surfaces; and (iii) formalize an ML workflow that integrates molecular descriptors and DFT-derived features to prioritize catalyst–pollutant pairs. The combined view rationalizes why S-scheme and Z-scheme heterostructures often preserve stronger oxidative/reductive potentials, enabling faster viral capsid/protein/RNA damage under visible/solar excitation.

Semiconductor photocatalysis of antiviral drugs proceeds through photo-excited charge carriers that generate reactive oxygen species (ROS) and drive selective bond activation. Clarifying how molecular structure, adsorption geometry, and excited-state dynamics couple to ROS chemistry is essential for rational catalyst–pollutant design [48,144,145].

Figure 5. Band-alignment–dependent charge transfer and ROS pathways in heterojunction photocatalysts (type-II, Z-scheme, S-scheme) and their roles in antiviral inactivation. Adapted from representative literature on TiO2/ZnO/g-C3N4 heterojunctions [36,92,93]. Arrows indicate e−/h+ transfer and ROS generation.

6.1. Classification of Transformation Products (TPs) and Structure–Ecotoxicity Relationships

Transformation products (TPs) generated during the oxidation of antiviral pharmaceuticals display diverse structural motifs that significantly influence their environmental persistence and ecotoxicity. Based on experimentally reported degradation pathways for favipiravir, oseltamivir carboxylate, remdesivir, and related antivirals, the resulting TPs can be broadly classified into several mechanistic categories:

- (1)

- Hydroxylated derivatives.

Hydroxyl radical attack often adds hydroxyl groups to aromatic or heterocyclic rings. Although hydroxylation increases polarity, these intermediates may still bind strongly to biological macromolecules and sometimes exhibit comparable or even higher toxicity toward algae and invertebrates.

- (2)

- Dehalogenated and dealkylated fragments.

For halogenated antivirals such as favipiravir, loss of halogens or cleavage of alkyl side-chains can modify electron density distributions and yield intermediates with enhanced electrophilicity. While some dehalogenated products degrade more rapidly, others retain mutagenic or cytotoxic potential.

- (3)

- Ring-opened products.

Oxidative cleavage of aromatic or heterocyclic cores—common in photocatalytic, ozonation, and sulfate-radical AOPs—produces linear or partially fragmented structures rich in carbonyl groups. These species generally exhibit increased reactivity, higher solubility, and the potential to disrupt microbial metabolism due to enhanced redox activity.

- (4)

- Nitrosated, nitrated, or partially oxidized TPs.

Under nitrogen-rich wastewater conditions, reactive nitrogen species may form nitrosated or nitrated TPs, while ROS-driven processes generate aldehyde, carboxylate, or quinone-like fragments. Such products are often more electrophilic and can induce oxidative stress in aquatic organisms.

Collectively, these patterns show that increased polarity does not necessarily translate to reduced ecotoxicity. Instead, toxicity tends to correlate with the presence of electron-deficient groups (e.g., carbonyls, nitroso moieties), the ability to undergo redox cycling, and enhanced molecular reactivity. These insights underscore the necessity of TP-specific toxicity evaluation and highlight the value of computational tools—such as frontier orbital analysis, Fukui indices, and ML toxicity models—in predicting environmental risks associated with antiviral degradation products.

6.2. Mechanistic Pathways of Antiviral Degradation

Upon irradiation, photogenerated holes (h+) and electrons (e−) yield •OH, •O2−, and, in some systems, 1O2; scavenger tests and EPR commonly identify •OH/•O2− as dominant oxidants for nucleoside-like antivirals [43,128]. For hetero(aromatic) scaffolds (e.g., favipiravir, molnupiravir), early steps involve electrophilic •OH addition (ring hydroxylation) and subsequent C–N/C–O scission that destabilizes ribonucleoside motifs and opens rings [44,82]. LC-HRMS/MS mapping routinely detects hydroxylated intermediates, ribose deconstruction products, and carboxylates; several transformation products (TPs) exhibit non-negligible predicted toxicity, underscoring the need for pathway control rather than parent removal alone [104,105]. Band-edge-matched catalysts (e.g., TiO2/g-C3N4) favor stepwise oxidation while minimizing halogenated TPs under aerated, near-neutral conditions [83].

6.3. DFT Insights into Structure–Activity Relationships

Density functional theory (DFT) provides quantitative links between antiviral structure and photocatalytic reactivity. Smaller HOMO–LUMO gaps (ΔE) correlate with higher electronic polarizability and faster apparent pseudo-first-order rates under identical ROS fluxes [84,87]. Frontier orbital analysis and molecular electrostatic potential (MEP) maps locate electron-rich carbonyl/heteroaromatic sites that act as preferred attack loci for •OH/•O2− [85,86]. Global reactivity indices—chemical hardness (η), softness (S), electrophilicity (ω), and chemical potential (μ)—discriminate antivirals with similar ΔE but different substitution patterns [87,88,89]. Local descriptors (Fukui functions f−/f+, NBO charges, Wiberg bond indices) highlight scissile C–N and C–O bonds that control pathway branching and TP spectra [88,89].

Across catalyst families, computed adsorption energies (Eads) on representative facets (anatase (101), ZnO (10-10), g-C3N4 (001)) predict interfacial electron transfer propensity; moderately strong binding (|Eads| ≈ 0.5–1.0 eV) balances activation and desorption of benign products [48,144]. Recent advances integrate frontier orbital descriptors with DFT-derived adsorption energetics to rationalize antiviral degradation efficiencies across TiO2, ZnO, and g-C3N4 platforms [145,149].

6.4. Adsorption Geometry and Catalyst–Pollutant Interactions

Interfacial chemistry governs selectivity. On hydroxylated TiO2, antivirals adsorb via H-bonding to surface –OH and carbonyl/amide motifs; metal dopants (e.g., Cu+/Fe3+) introduce trap states that accelerate interfacial charge transfer and •OH genesis near the adsorption complex [39]. On g-C3N4 and carbon hybrids, π–π and n–π* interactions align frontier orbitals and promote •O2− formation through enhanced O2 activation at defect sites [48]. Heterojunctions (Z-/S-scheme) maintain strong redox potentials while spatially separating carriers, suppressing back-recombination and steering pathways away from persistent, partially oxidized TPs [150,151].

6.5. Excited-State Contributions: TD-DFT and SAC-CI

Time-dependent DFT (TD-DFT) captures vertical excitations and oscillator strengths of antivirals and surface-bound complexes, rationalizing photosensitized routes under visible light on narrow-gap catalysts [49,152]. Symmetry-Adapted Cluster–Configuration Interaction (SAC-CI) provides benchmark excited-state energies and transition assignments, supporting observed red-shifts (λmax) for molnupiravir relative to remdesivir on suitable heterojunctions [153]. Coupling excited-state maps with band positions (ECB/EVB) clarifies whether ligand-to-metal charge transfer or surface-complex pathways dominate under solar spectra. The calculated quantum descriptors (ΔE, dipole moment, and adsorption energy Eads) for representative antiviral drugs, and their correlation with experimental degradation efficiencies, are summarized in Table 5.

Table 5. Calculated quantum chemical descriptors (ΔE, dipole moment, and adsorption energy Eads) of representative antiviral drugs, and their correlation with experimentally reported photocatalytic degradation efficiencies.

|

Antiviral Drug |

ΔE (eV) |

Dipole Moment (D) |

Adsorption Energy Eads (eV) |

Experimental Degradation Efficiency (%) |

Notes/References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Favipiravir |

3.6 |

4.8 |

−1.9 |

>90% (Fe–g-C3N4, solar light) |

|

|

Remdesivir |

4.8 |

6.1 |

−1.1 |

~70% (ZnO, UV) |

|

|

Molnupiravir |

3.7 |

5.3 |

−1.7 |

~85% (g-C3N4, solar) |

High oscillator strength transitions [55] |

|

Oseltamivir carboxylate |

4.2 |

6.5 |

−1.5 |

>95% (Fe–doped g-C3N4, visible light) |

The calculated adsorption energies (Eads) reported in Table 5 show a clear qualitative correlation with experimentally observed degradation efficiencies. Antiviral molecules exhibiting stronger interfacial binding (Eads ≈ −1.5 to −2.0 eV), such as favipiravir and oseltamivir carboxylate, tend to undergo faster photocatalytic oxidation because their adsorption geometries promote efficient electron–hole transfer and ROS attack at the initial reaction coordinates. Conversely, antivirals with weaker adsorption (Eads ≈ −1.0 eV), such as remdesivir, generally display lower photocatalytic rates under comparable conditions. This agreement reinforces the mechanistic role of interfacial electron transfer and bond activation in governing antiviral degradation.

Nevertheless, several cases exist where DFT predictions diverge from experimental observations. These discrepancies may arise from factors not fully captured in cluster or slab models, including (i) solvent structuring and hydrogen-bond networks at the catalyst–water interface, (ii) surface hydration layers that alter adsorption strength, (iii) competitive adsorption from natural organic matter or coexisting ions in real water matrices, and (iv) kinetic barriers associated with mass transfer or exciton dynamics rather than ground-state energetics. Such cases highlight that while DFT-derived Eads values provide valuable mechanistic insight, they should be interpreted as part of a broader multi-parameter framework that incorporates excited-state reactivity, ROS production efficiencies, and catalyst microstructure. Integrating DFT descriptors with ML models, as outlined in Section 6.5, helps overcome these limitations by learning complex nonlinear relationships between structural features and experimental performance.

6.6. Machine Learning (ML) Integration for Predictive Design

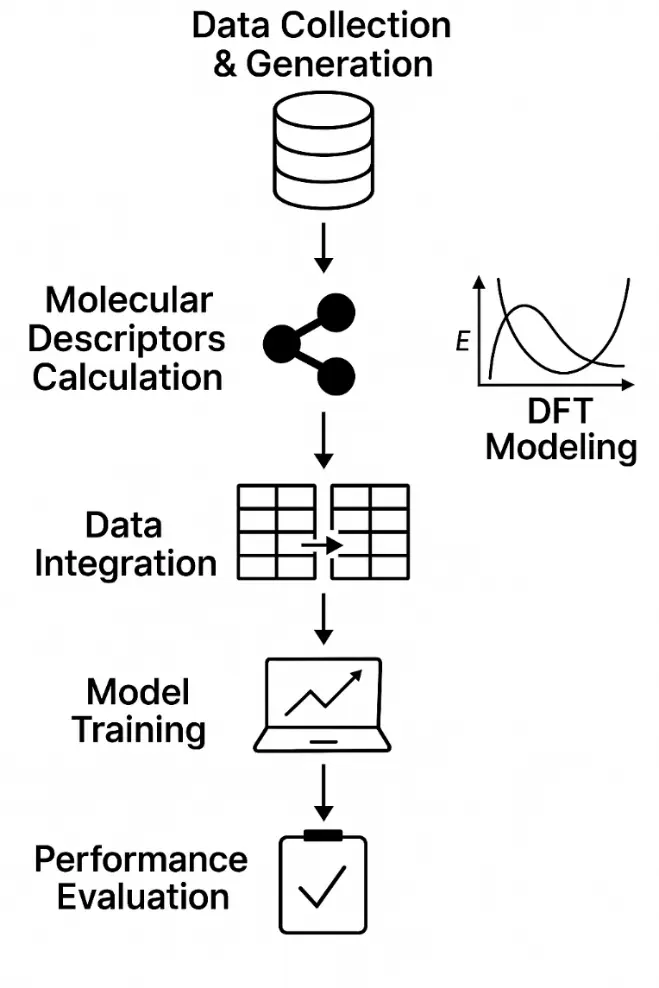

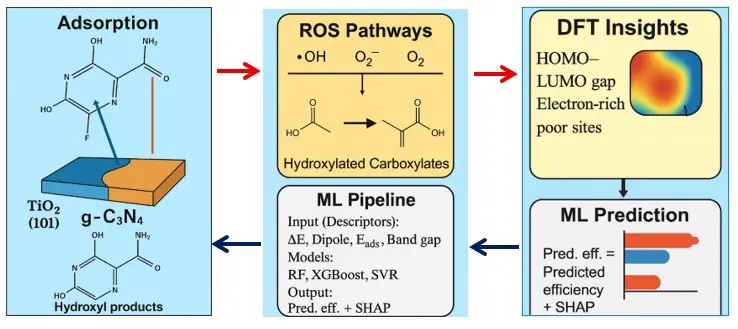

ML augments mechanistic understanding by learning quantitative relations between descriptors and performance. Curated datasets combining DFT descriptors of antivirals (ΔE, μ, η, ω, dipole moment, MEP/Fukui features), catalyst properties (band gap, ECB/EVB, specific surface area, zeta potential, defect/dopant class), and experimental outcomes (kapp, TOC removal, TP toxicity proxies) enable robust models (Random Forest, XGBoost, SVR) to predict catalyst–pollutant pairs and operating windows [154,155,156]. Rigorous workflows employ nested cross-validation and external blind tests; SHAP analyses consistently rank ΔE, Eads, and dipole moment among the most influential antiviral features, with band alignment and heterojunction type leading catalyst features [155]. Active-learning loops and Bayesian optimization further prioritize experimental candidates, reducing trial-and-error and focusing synthesis on high-value regions of descriptor space. This integration of DFT descriptors with machine learning models for predictive photocatalytic performance is schematically illustrated in Figure 7 [156,157,158].

Figure 7. Machine-learning (ML) workflow integrating density functional theory (DFT)–derived descriptors with predictive models (Random Forest, XGBoost, Support Vector Regression) to predict photocatalytic degradation performance of antiviral drugs. The pipeline includes data curation, descriptor generation, model training/validation, and feature-importance analysis. Adapted from representative DFT/ML studies [146,147,148]. Abbreviations: ML, DFT, CB, VB, ROS, EPR, PL, BET, DRS.

7. Research Gaps and Future Perspectives

To enable cross-study comparability and practical scale-up, we recommend routine quantification of both incident and absorbed photon flux under the exact optical geometry of each experiment, using validated chemical actinometry (e.g., ferrioxalate). Photocatalytic performance should be reported as apparent quantum yield (AQY; moles transformed per mole of incident photons) and, when feasible, as internal quantum efficiency (IQE; moles transformed per mole of absorbed photons). Building on the protocol-level guidance of Hoque and Guzman [159], authors should document the emission spectrum and irradiance of the light source, optical path, and reactor geometry, actinometer calibration and uncertainty, and the full AQY/IQE calculation steps. Complementing this procedural focus, the broader standardization perspective outlined by Guzman [160] advocates transparent definitions of performance metrics, clear reference standards, and instrument traceability, elements that are essential for harmonized antiviral photocatalysis reporting and truly reproducible, quantitative comparisons across studies [160].

Despite rapid advances in monitoring and remediation of antiviral pharmaceuticals, several critical knowledge gaps still impede robust risk assessment and practical deployment. These include (i) geographically and methodologically uneven environmental surveillance, (ii) incomplete structural confirmation and toxicity profiling of transformation products and mixtures, (iii) limited chronic and community-level ecotoxicology, (iv) poorly constrained environmental windows for resistance selection, (v) pilot-to-full-scale translation under realistic matrices with standardized photon management and durability assessments, and (vi) open, FAIR data linking DFT/ML descriptors to standardized kinetic and mineralization metrics. The following Sections 7.1–7.6 detail these priorities and propose an actionable agenda toward reproducible, scalable antiviral abatement.

7.1. Monitoring and Surveillance

Environmental monitoring of antivirals is still geographically uneven and methodologically heterogeneous. Harmonized protocols (targeted + suspect/non-target HRMS), reporting limits (LOD/LOQ), uncertainty budgets, and seasonal multi-year campaigns are needed to capture true spatiotemporal trends, particularly in under-represented regions [9,148,161].

7.2. Transformation Products (TPs) and Mixtures

Only a subset of antiviral TPs has been structurally confirmed. Non-target and effect-directed analyses should be coupled to pathway elucidation to identify persistent/biorecalcitrant or halogenated TPs, quantify their occurrence, and characterize mixture toxicity with co-occurring pharmaceuticals and disinfectants [31,116].

7.3. Ecotoxicology Beyond Model Organisms

Most studies focus on algae, Daphnia, and zebrafish embryos. There is a need for chronic, multigenerational tests, community-level assays (microbiomes, periphyton, biofilms), trophic-transfer assessments, and mesocosm/field validations under environmentally realistic mixtures and pulsed exposures [124,125].

7.4. Environmental Resistance Risks

Links between environmental concentrations and selective windows for antiviral resistance remain poorly resolved. Integrated surveillance (metagenomics/metaviromics), reservoir studies (sediments, wetlands, WWTP biofilms), and experimental evolution at sub-lethal levels are required to quantify risk and inform thresholds for management [162,163,164].

7.5. From Bench to Practice

Pilot- and full-scale demonstrations under real effluents are scarce. Key barriers include photon management (solar variability, photon flux reporting), catalyst durability (photocorrosion, fouling, leaching), immobilization/recovery, hydraulics/light penetration in reactors, and by-product control. Standardized reporting (actinometry, incident/absorbed photon flux, reactor geometry, optical path, mixing, catalyst characterization) should be mandated. Techno-economic analysis (TEA) and life-cycle assessment (LCA) are needed to benchmark photocatalysis against alternatives and to address brine/concentrate management when hybridized with membranes [165,166,167,168,169].

Reactor-level engineering considerations are central to the feasibility of photocatalytic antiviral removal at pilot and full scale. A primary challenge is light penetration through turbid wastewater matrices, where suspended solids and dissolved organic matter cause strong scattering and attenuation of UV/visible photons. As a result, the effective optical path length is often only a few millimeters, necessitating shallow-depth reactors, optimized lamp–reactor geometries, or immobilized thin-film catalysts to maintain uniform photon flux. In slurry systems, mass-transfer limitations can become rate-controlling when catalyst aggregates inhibit pollutant diffusion to active sites. Conversely, immobilized catalysts improve photon utilization but may suffer from reduced surface area and boundary-layer transport constraints. Balancing these trade-offs is essential for achieving high quantum efficiency under realistic conditions.

Transitioning from batch to continuous-flow operation introduces additional hydrodynamic and operational complexities. Flow-through photoreactors must ensure adequate mixing without excessive energy input, maintain homogeneous irradiance distribution, and avoid catalyst sedimentation or channeling. Tubular, annular, and flat-plate configurations each offer different compromises between volumetric throughput, pressure drop, and photon delivery. For large-scale applications, the specific energy consumption (kWh·m−3 treated) becomes a decisive metric; solar-assisted or low-pressure LED systems can significantly lower operational costs compared to traditional UV lamps, but require careful optical design to maximize photon capture efficiency.

Finally, practical deployment must consider catalyst recovery, long-term stability, fouling propensity, and integration into existing treatment trains. Hybrid systems—such as photocatalytic membrane reactors, packed-bed immobilized catalysts, or solar concentrator reactors—represent promising avenues for scale-up, but must be supported by rigorous techno-economic analysis and life-cycle assessment. Addressing these engineering challenges is essential for translating the promising laboratory performance of antiviral photocatalysis into sustainable, field-ready water treatment technologies.

7.6. Computational and Data Infrastructure

DFT and ML show promise but are limited by small, fragmented datasets. FAIR, open benchmarks that link antiviral descriptors (ΔE, dipole, Eads, Fukui/MEP) and catalyst features (band alignment, defect/dopant class, surface area, zeta potential) to standardized outcomes (kapp, mineralization, TP toxicity) are essential. Best practices include uncertainty quantification, external validation, SHAP-based interpretation, and active-learning loops to prioritize experiments [146,147,148,170].

8. Actionable Agenda and Future Perspectives

8.1. Actionable Agenda

- i.

-

Launch coordinated monitoring consortia with harmonized QA/QC;

- ii.

-

embed non-target/effect-directed TP screening in all treatment studies;

- iii.

-

expand chronic, community-level ecotoxicology and resistance-focused assays;

- iv.

-

standardize photocatalytic reporting and scale up via immobilized/solar reactors with TEA/LCA;

- v.

-

establish open DFT/ML benchmarks and prospective validation campaigns.

8.2. Future Perspectives

Looking ahead, several priority directions should be pursued to advance the understanding and remediation of antiviral pharmaceuticals as emerging contaminants. First, comprehensive and systematic monitoring programs are urgently needed—particularly in regions with high antiviral consumption—to generate robust, comparable datasets on environmental occurrence and seasonal variability [27,161].

Second, the development of green and sustainable photocatalysts—including biochar-derived composites, low-cost two-dimensional (2D) hybrids, and other environmentally friendly materials—will be critical for scaling laboratory advances to real-world applications, alongside standardized performance and reporting metrics [92,93].

In addition, integrating experimental investigations with computational approaches such as density functional theory (DFT), machine learning (ML), and high-throughput screening will accelerate the discovery of efficient catalyst–pollutant pairs and reduce reliance on trial-and-error experimentation [146,147,148].

Finally, interdisciplinary collaborations between environmental chemists, virologists, toxicologists, and materials scientists are essential to tackle the dual challenges of ecotoxicity and resistance, ensuring that treatment strategies are both scientifically robust and environmentally sustainable [162,163].

9. Conclusions

Antiviral pharmaceuticals have emerged as a distinct class of environmental contaminants, driven by their unprecedented use during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. Their frequent detection in aquatic systems—combined with persistence, polarity, and inherent biological activity—raises serious concerns about ecotoxicological effects and the potential emergence of resistance. Conventional wastewater treatments achieve only partial removal, underscoring the urgent need for advanced and sustainable remediation technologies.

Among available options, photocatalytic remediation using TiO2, ZnO, g-C3N4, and their modified composites has shown strong potential for solar-driven degradation of antiviral drugs. Recent advances in metal doping, heterojunction engineering, and carbon-based nanocomposites have further enhanced efficiency and selectivity, making these systems attractive for practical deployment. Importantly, mechanistic insights from DFT and SAC-CI provide molecular-level understanding of degradation pathways, while machine-learning models open powerful opportunities for predictive catalyst discovery and accelerated materials design.

To the best of our knowledge, this review is among the first comprehensive efforts dedicated exclusively to antiviral pharmaceuticals as emerging contaminants. By bridging environmental occurrence, ecotoxicological risks, and advanced remediation pathways—and by integrating experimental evidence with computational approaches—this work establishes a specialized foundation for future research and translation to practice. Ultimately, interdisciplinary collaboration will be critical to develop sustainable strategies that mitigate the environmental impacts of antiviral drugs and safeguard both ecosystem integrity and public health.

Statement of the Use of Generative AI and AI-Assisted Technologies in the Writing Process

During the preparation of this manuscript, generative AI tools (ChatGPT, OpenAI) were used solely for language polishing and improvement of readability. All scientific content, interpretations, and conclusions were critically reviewed and approved by the authors, who take full responsibility for the manuscript.

Acknowledgment

The authors acknowledge Al al-Bayt University, Mafraq—Jordan, for research support.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.A.A.-S. and L.A.-S.; literature survey and data curation, K.A.A.-S. and L.A.-S.; writing—original draft preparation, K.A.A.-S.; writing—review and editing, K.A.A.-S. and L.A.-S.; visualization, K.A.A.-S.; supervision, K.A.A.-S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Ethics Statement

This study did not involve human participants or animals. Therefore, ethical approval was not required.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable. No new data were generated or analyzed in this study.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

-

Aus der Beek T, Weber F-A, Bergmann A, Hickmann S, Ebert I, Hein A, et al. Pharmaceuticals in the environment—Global occurrences and perspectives. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2016, 35, 823–835. doi:10.1002/etc.3339. [Google Scholar]

-

Domínguez-García P, Fernández-Ruano L, Báguena J, Cuadros J, Gómez-Canela C. Assessing the pharmaceutical residues as hotspots of the main rivers of Catalonia, Spain. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 44080–44095. doi:10.1007/s11356-024-33967-7. [Google Scholar]

-

Aus der Beek T, Weber F-A, Bergmann A, Hickmann S, Ebert I, Hein A, et al. Pharmaceuticals in the Environment: Occurrence, Effects and Options for Action; German Federal Environment Agency (UBA): Dessau-Roßlau, Germany, 2016; Texte 23/2016. Available online: https://www.umweltbundesamt.de/publikationen/pharmaceuticals-in-the-environment-occurrence-effects (accessed on 9 October 2025). [Google Scholar]

-

Singer AC, Shaw H, Rhodes V, Hart A. Review of Antimicrobial Resistance in the Environment and Its Relevance to Environmental Regulators. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 1728. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2016.01728. [Google Scholar]

-

Sharma VK, Johnson N, Cizmas L, McDonald TJ, Kim H. A review of the influence of treatment strategies on antibiotic resistant bacteria and antibiotic resistance genes. Chemosphere 2016, 150, 702–714. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2015.12.084. [Google Scholar]

-

Efrain Merma Chacca D, Maldonado I, Vilca FZ. Environmental and ecotoxicological effects of drugs used for the treatment of COVID-19. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 940975. doi:10.3389/fenvs.2022.940975. [Google Scholar]

-

Bartels I, Jaeger M, Schmidt TC. Determination of anti-SARS-CoV-2 virustatic pharmaceuticals in the aquatic environment using high-performance liquid chromatography–high-resolution mass spectrometry. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2023, 415, 5365–5377. doi:10.1007/s00216-023-04811-7. [Google Scholar]

-

Danner MC, Robertson A, Behrends V, Reiss J. Antibiotic pollution in surface fresh waters: Occurrence and effects. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 664, 793–804. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.01.406. [Google Scholar]

-

Zhang Y, Yuan J, Ding Y, Liu B, Zhao L, Zhang S. Research progress on g-C3N4-based photocatalysts for organic pollutants degradation in wastewater: From exciton and carrier perspectives. Ceram. Int. 2021, 47, 31005–31030. doi:10.1016/j.ceramint.2021.08.063. [Google Scholar]

-

Zhang Z, He D, Zhao S, Qu J. Recent developments in semiconductor-based photocatalytic degradation of antiviral drug pollutants. Toxics 2023, 11, 692. doi:10.3390/toxics11080692. [Google Scholar]

-

Leyva-Díaz JC, Batlles-delaFuente A, Molina-Moreno V, Sánchez Molina J, Belmonte-Ureña LJ. Removal of pharmaceuticals from wastewater: Analysis of the past and present global research activities. Water 2021, 13, 2353. doi:10.3390/w13172353. [Google Scholar]

-

Dinata R, Baindara P, Mandal SM. Evolution of Antiviral Drug Resistance in SARS-CoV-2. Viruses 2025, 17, 722. doi:10.3390/v17050722. [Google Scholar]

-

Nannou C, Ofrydopoulou A, Evgenidou E, Heath D, Heath E, Lambropoulou D. Antiviral drugs in aquatic environment and wastewater treatment plants: A review on occurrence, fate, removal and ecotoxicity. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 699, 134322. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.134322. [Google Scholar]

-

Söderström H, Järhult JD, Olsen B, Lindberg RH, Tanaka H, Fick J. Detection of the Antiviral Drug Oseltamivir in Aquatic Environments. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e6064. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0006064. [Google Scholar]

-

Wang R, Luo J, Li C, Chen J, Zhu N. Antiviral drugs in wastewater are on the rise as emerging contaminants: A comprehensive review of spatiotemporal characteristics, removal technologies and environmental risks. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 457, 131694. doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2023.131694. [Google Scholar]

-

Abafe OA, Späth J, Fick J, Jansson S, Buckley C, Stark A, et al. LC-MS/MS determination of antiretroviral drugs in influents and effluents from wastewater treatment plants in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Chemosphere 2018, 200, 660–670. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.02.105. [Google Scholar]

-

Paíga P, Santos LHMLM, Ramos S, Jorge S, Silva JG, Delerue-Matos C. Presence of pharmaceuticals in the Lis river (Portugal): Sources, fate and seasonal variation. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 573, 164–177. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.08.089. [Google Scholar]

-

Verlicchi P, Al Aukidy M, Zambello E. Occurrence of pharmaceutical compounds in urban wastewater: Removal, mass load and environmental risk after a secondary treatment—A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2012, 429, 123–155. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2012.04.028. [Google Scholar]

-

Ahmed MB, Zhou JL, Ngo HH, Guo W. Adsorptive removal of antibiotics from water and wastewater: Progress and challenges. Sci. Total Environ. 2015, 532, 112–126. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2015.05.130. [Google Scholar]

-

Luo Y, Guo W, Ngo HH, Nghiem LD, Hai FI, Zhang J, et al. A review on the occurrence of micropollutants in the aquatic environment and their fate and removal during wastewater treatment. Sci. Total Environ. 2014, 473–474, 619–641. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2013.12.065. [Google Scholar]

-

Bartels I, Nahar N, Smollich E, Zimmermann S, Schmidt TC, Jaeger M, et al. Ecotoxicological data of selected antiviral drugs acting against SARS-CoV-2: Aliivibrio fischeri bioluminescence inhibition, Daphnia magna immobilization, and comparison with in silico predictions. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2025, 37, 154. doi:10.1186/s12302-025-01154-1. [Google Scholar]

-

Monjezi Z, Tarlani A, Esfahani H, Asghar A, Salemi A, Zadmard R, et al. Simultaneous photocatalytic degradation of remdesivir, favipiravir, and diclofenac from aqueous solutions using a quaternary plasmonic Ag/Ag-SG-TiO2-rGO photocatalyst: Synthesis, characterization, optimization, and toxicity assessment. J. Water Process Eng. 2024, 67, 106267. doi:10.1016/j.jwpe.2024.106267. [Google Scholar]

-

Wallace VJ, Sakowski EG, Preheim SP, Prasse C. Bacteria exposed to antiviral drugs develop antibiotic cross-resistance and unique resistance profiles. Commun. Biol. 2023, 6, 837. doi:10.1038/s42003-023-05177-3. [Google Scholar]

-

Li X, Wang S, Chen P, Xu B, Zhang X, Xu Y, et al. ZIF-derived non-bonding Co/Zn coordinated hollow carbon nitride for enhanced removal of antibiotic contaminants by peroxymonosulfate activation: Performance and mechanism. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2023, 325, 122401. doi:10.1016/j.apcatb.2023.122401. [Google Scholar]

-

Czech B, Krzyszczak A, Boguszewska-Czubara A, Opielak G, Jośko I, Hojamberdiev M. Revealing the toxicity of lopinavir- and ritonavir-containing water and wastewater treated by photo-induced processes to Danio rerio and Aliivibrio fischeri. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 824, 153967. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.153967. [Google Scholar]

-

Kumar M, Kuroda K, Dhangar K, Mazumder P, Sonne C, Rinklebe J, et al. Potential emergence of antiviral-resistant pandemic viruses via environmental drug exposure of animal reservoirs. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 8503–8505. doi:10.1021/acs.est.0c03105. [Google Scholar]

-

Löffler P, Escher BI, Baduel C, Virta MP, Lai FY. Antimicrobial Transformation Products in the Aquatic Environment: Global Occurrence, Ecotoxicological Risks, and Potential of Antibiotic Resistance. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 9474–9494. doi:10.1021/acs.est.2c09854. [Google Scholar]

-

Gogoi A, Mazumder P, Tyagi VK, Tushara Chaminda GG, An AK, Kumar M. Occurrence and fate of emerging contaminants in water environment: A review. Groundw. Sustain. Dev. 2018, 6, 169–180. doi:10.1016/j.gsd.2017.12.009. [Google Scholar]

-

Wols BA, Hofman-Caris CHM. Review of photochemical reaction constants of organic micropollutants required for UV advanced oxidation processes in water. Water Res. 2012, 46, 2815–2827. doi:10.1016/j.watres.2012.03.036. [Google Scholar]

-

Brienza M, Katsoyiannis IA. Sulfate radical technologies as tertiary treatment for the removal of emerging contaminants from wastewater. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1604. doi:10.3390/su9091604. [Google Scholar]

-

Fedorova G, Grabic R, Nyhlen J, Järhult JD, Söderström H. Fate of three anti-influenza drugs during ozonation of wastewater effluents—Degradation and formation of transformation products. Chemosphere 2016, 150, 723–730. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2015.12.051. [Google Scholar]

-

Kostich MS, Batt AL, Lazorchak JM. Concentrations of prioritized pharmaceuticals in effluents from 50 large wastewater treatment plants in the US and implications for risk estimation. Environ. Pollut. 2014, 184, 354–359. doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2013.09.013. [Google Scholar]

-

Rivera-Utrilla J, Sánchez-Polo M, Ferro-García MA, Prados-Joya G, Ocampo-Pérez R. Pharmaceuticals as emerging contaminants and their removal from water: A review. Chemosphere 2013, 93, 1268–1287. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2013.07.059. [Google Scholar]

-

Michael-Kordatou I, Michael C, Duan X, He X, Dionysiou DD, Fatta-Kassinos D. Dissolved effluent organic matter: Characteristics and potential implications in wastewater treatment and reuse applications. Water Res. 2015, 77, 213–248. doi:10.1016/j.watres.2015.03.011. [Google Scholar]

-

Chong MN, Jin B, Chow CWK, Saint C. Recent developments in photocatalytic water treatment technology: A review. Water Res. 2010, 44, 2997–3027. doi:10.1016/j.watres.2010.02.039. [Google Scholar]

-

Peláez M, Nolan NT, Pillai SC, Seery MK, Falaras P, Kontos AG, et al. A review on the visible light active titanium dioxide photocatalysts for environmental applications. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2012, 125, 331–349. doi:10.1016/j.apcatb.2012.05.036. [Google Scholar]

-

Singer AC, Nunn MA, Griffiths J, Dunstan H, Brown J. Potential risks associated with the proposed widespread use of Tamiflu: A review of oseltamivir excretion, environmental fate, and ecotoxicological effects. Environ. Health Perspect. 2007, 115, 102–106. doi:10.1289/ehp.9574. [Google Scholar]

-

Zhang JH, Hou YJ, Wang SJ, Zhu X, Zhu CY, Wang Z, et al. A facile method for scalable synthesis of ultrathin g-C3N4 nanosheets for efficient hydrogen production. J. Mater. Chem. A 2018, 6, 18252–18257. doi:10.1039/C8TA06726K. [Google Scholar]

-

Ong W-J, Tan L-L, Ng YH, Yong S-T, Chai S-P. Graphitic Carbon Nitride (g-C3N4)-Based Photocatalysts for Artificial Photosynthesis and Environmental Remediation: Are We a Step Closer To Achieving Sustainability? Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 7159–7329. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00075. [Google Scholar]

-

Sui Q, Huang J, Deng S, Yu G, Fan Q. Occurrence and removal of pharmaceuticals, caffeine and DEET in wastewater treatment plants of Beijing, China. Water Res. 2010, 44, 417–426. doi:10.1016/j.watres.2009.07.010. [Google Scholar]

-

Kuroda K, Li C, Dhangar K, Kumar M. Predicted occurrence, ecotoxicological risk and environmentally acquired resistance of antiviral drugs associated with COVID-19 in environmental waters. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 776, 145740. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.145740. [Google Scholar]

-

Biswas S, Pal A. A Brief Review on the Latest Developments on Pharmaceutical Compound Degradation Using g-C3N4-Based Composite Catalysts.. Catalysts 2023, 13, 925. doi:10.3390/catal13060925. [Google Scholar]

-

Eshghi F, Mehrabadi Z, Farsadrooh M, Hayati P, Javadian H, Karimi M, et al. Photocatalytic degradation of remdesivir nucleotide pro-drug using [Cu(1-methylimidazole)4(SCN)2] nanocomplex synthesized by sonochemical process: Theoretical, hirshfeld surface analysis, degradation kinetic, and thermodynamic studies. Environ. Res. 2023, 222, 115321. doi:10.1016/j.envres.2023.115321. [Google Scholar]

-

Mohammadi S, Moussavi G, Kiyanmehr K, Shekoohiyan S, Heidari M, Naddafi K, et al. Degradation of the antiviral remdesivir by a novel, continuous-flow, helical-baffle incorporating VUV/UVC photoreactor: Performance assessment and enhancement by inorganic peroxides. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2022, 298, 121665. doi:10.1016/j.seppur.2022.121665. [Google Scholar]

-

Eryildiz-Yesir B, Polat E, Altınbaş M, Gul BY, Koyuncu I. Long-term study on the fate and environmental risks of favipiravir in wastewater treatment plants and comparison with COVID-19 cases. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 949, 175014. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.175014. [Google Scholar]

-

Eryildiz-Yesir B, Yavuzturk Gul B, Koyuncu I. A sustainable approach for the removal and analytical determination methods of antiviral drugs from water/wastewater: A review. J. Water Process Eng. 2022, 49, 103036. doi:10.1016/j.jwpe.2022.103036. [Google Scholar]

-

Ternes TA, Joss A, Siegrist H. Peer reviewed: Scrutinizing pharmacuticals and personal care products in wastewater treatment. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2004, 38, 392A–399A. doi:10.1021/es040639t. [Google Scholar]

-

Kovačević M, Simić M, Živković S, Milović M, Tolić Stojadinović L, Relić D, et al. Uncovering metal-decorated TiO2 photocatalysts for ciprofloxacin degradation—A combined experimental and DFT study. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 11844. doi:10.3390/ijms252111844. [Google Scholar]

-

Butler KT, Davies DW, Cartwright H, Isayev O, Walsh A. Machine learning for molecular and materials science. Nature 2018, 559, 547–555. doi:10.1038/s41586-018-0337-2. [Google Scholar]

-

Almeida A, De Mello-Sampayo C, Lopes A, Carvalho da Silva R, Viana P, Meisel L. Predicted environmental risk assessment of antimicrobials with increased consumption in Portugal during the COVID-19 pandemic; The groundwork for the forthcoming water quality survey. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 652. doi:10.3390/antibiotics12040652. [Google Scholar]

-

Gwenzi W, Selvasembian R, Offiong NAO, Mahmoud AED, Sanganyado E, Mal J. COVID-19 drugs in aquatic systems: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2022, 20, 1275–1294. doi:10.1007/s10311-021-01356-y. [Google Scholar]

-

Azuma T, Ishiuchi H, Inoyama T, Teranishi Y, Yamaoka M, Sato T, et al. Detection of peramivir and laninamivir, new anti-influenza drugs, in sewage effluent and river waters in Japan. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0131412. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0131412. [Google Scholar]

-

Escher BI, Bramaz N, Lienert J, Neuwoehner J, Straub JO. Mixture toxicity of the antiviral drug Tamiflu® (oseltamivir ethylester) and its active metabolite oseltamivir acid. Aquat. Toxicol. 2010, 96, 194–202. doi:10.1016/j.aquatox.2009.10.020. [Google Scholar]

-

Mahaye N, Musee N. Effects of two antiretroviral drugs on the crustacean Daphnia magna in river water. Toxics 2022, 10, 423. doi:10.3390/toxics10080423. [Google Scholar]

-

Funke J, Prasse C, Ternes TA. Identification of transformation products of antiviral drugs formed during biological wastewater treatment and their occurrence in the urban water cycle. Water Res. 2016, 98, 75–83. doi:10.1016/j.watres.2016.03.045. [Google Scholar]

-