Toluene or Formaldehyde Removal by Photocatalysis and Adsorption Using Hybrid Optical Fiber Textiles Containing Activated Carbon and/or TiO2

Received: 15 July 2025 Revised: 06 August 2025 Accepted: 05 December 2025 Published: 16 December 2025

© 2025 The authors. This is an open access article under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

1. Introduction

Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs) are harmful chemical compounds that are emitted by various sources, such as vehicles, industrial plants, and chemical processes. These substances pose a significant risk to both human health and the environment [1]. When VOCs are released into the air, they can contribute to a range of health problems, including respiratory issues, eye irritation, headaches, and even long-term diseases such as cancer. Moreover, VOCs are major contributors to air pollution and can also lead to the formation of ground-level ozone, which is a key component of smog.

To mitigate these risks, several treatment processes have been developed to remove or neutralize VOCs [2]. However, each of these methods comes with its own set of challenges, particularly in terms of energy consumption and efficiency with incineration and catalytic treatment, both of which are the most common methods used for VOC treatment. On the other hand, adsorption is a non-destructive treatment method that uses solid materials (adsorbents) to capture VOCs from the air. This technique is more energy-efficient than incineration and catalytic methods, as it does not require high temperatures. However, one of the main drawbacks of adsorption is the need for regular reconditioning or regeneration of the adsorbent materials. This often involves additional processes, such as heating or using solvents, which can still be costly and energy-consuming.

In the early 1970s, the first publication appeared on air treatment, showing the partial oxidation of paraffins [3] since many publications deal with this process [4]. This method relies on the use of a photocatalyst, typically a semiconductor material, that can absorb light (usually UV light) to generate electron-hole pairs. These pairs initiate reactions that degrade VOCs into harmless substances, such as carbon dioxide and water. The key advantages of photocatalysis include its relatively low energy consumption, as it can operate under ambient conditions and atmospheric pressure, and its ability to remove a wide range of VOCs. Titanium dioxide (TiO2) is one of the most commonly used photocatalysts due to its stability and excellent photocatalytic activity under UV light. However, its slow reaction kinetics compared to more traditional methods limit its practical application, particularly in large-scale industrial settings where rapid treatment of high volumes of VOCs is required.

To address the limitations of standalone photocatalysis for volatile organic compounds (VOCs) removal, recent research has focused on hybrid systems combining adsorption and photocatalysis. In these systems, VOCs are first captured and concentrated by an adsorbent, then subsequently degraded by a photocatalyst such as TiO2. This approach has been widely studied [5], who provide a comprehensive review of TiO2-supported porous materials and highlights the potential of such systems for efficient photocatalyst regeneration. The authors conclude that the use of porous supports enhances the practical application of TiO2-based systems for pollutant degradation.

Building on this, Zou et al. [6] critically reviewed carbon-based nanocomposites for integrated VOC removal, emphasizing that hybrid material performance is highly dependent on the structure and carbon content. They also pointed out challenges related to VOC diffusion, light absorption, and the difficulty in identifying the rate-limiting steps. Importantly, the literature often fails to distinguish between two main applications of these hybrid systems: (i) adsorbent regeneration in static conditions and (ii) continuous VOC removal in dynamic flow systems—though both show distinct behaviors and conclusions.

In static mode, hybrid materials often enhance VOC mineralization, yet complete regeneration of the adsorbent is rarely achieved. For instance, Sampath et al. [7] demonstrated improved mineralization of pyridine using TiO2/zeolite composites under UV-A light. Similar findings were reported by Chen et al. [8] for hydrogen production from ethanol and by Yoneyama et al. [9] for propionaldehyde degradation, all suggesting that the local concentration of VOCs near TiO2 is increased via adsorption, enhancing photocatalysis.

However, complete regeneration remains problematic. Monneyron et al. [10] showed limited regeneration of TiO2/mordenite composites under UV-A, where a small fraction of adsorbed pollutants was released due to UV lamp heating. Thevenet et al. [11] found that only the non-adsorbed fraction of C2H2 was mineralized by TiO2/AC composites. More recently, T. Kim et al. [12] observed higher regeneration under UV-C compared to UV-A, consistent with findings by using TiO2/zeolite for formaldehyde and toluene. To improve aldehyde adsorption, S. Kim et al. [13] modified AC with polyethyleneimine (PEI) and MgO but noted that UV-based regeneration of TiO2/modified AC was less efficient.

In a large-scale dynamic setup (2.38 m3 chamber, 5.1 m3/min airflow), Ao and Lee [14] reported enhanced removal of NO and toluene using a system where TiO2 was physically separated from the AC filter. The synergy, attributed to the transfer of adsorbed VOCs to TiO2, thanks to the high flow used, also led to decreased NO2 formation due to AC adsorption.

In dynamic mode, photocatalytic efficiency and synergetic effects appear highly dependent on the UV source. Most studies have employed vacuum UV (V-UV, e.g., 185 nm) [10,15,16,17]. These works attribute improved performance to ozone formation under V-UV, which then generates reactive species such as O(1D) and •OH on the catalyst surface. Monneyron et al. [10] also found that TiO2/adsorbent composites did not alter the adsorption properties significantly and that the synergy was mainly due to V-UV-induced O3.

Liu et al. [15] highlighted the superior activity of TiO2/activated carbon fiber (ACF) composites under 185 nm irradiation, attributing enhanced formaldehyde degradation to increased hydroxyl radical generation via surface hydroxyls and improved electron transfer through Ti–C bonding. However, under UV-A (~308 nm), hybrid materials often show lower photocatalytic performance [17].

Other dynamic studies confirm the complexity of hybrid system behavior. Derakhshan-Nejad et al. [18] demonstrated that TiO2/ZSM-5 under UV improves ethylbenzene breakthrough time and reduces VOC release, though the isolated photocatalytic contribution was not assessed. Gauthier et al. [19] showed that under dynamic conditions, the use of adsorbents (AC or zeolite) did not enhance overall degradation of ethyl hexanoate, possibly due to insufficient desorption of VOCs from the adsorbent surface, in agreement with the work of Ao and lee [14].

In light of the existing literature, this study has the final objective to develop a new textile associating optical fiber, heating wire, AC, and TiO2. We begin by comparing the adsorption capacities of various commercial activated carbon (AC) materials for toluene and formaldehyde. These results are then benchmarked against a custom-prepared AC deposited on optical fiber textiles. Subsequently, our work focuses more deeply on the adsorption capacity of optical fiber textiles coated with AC, particularly for toluene. We specifically investigate the influence of AC loading and the presence of TiO2 on adsorption performance.

In the second phase of the study, we investigate the photocatalytic properties, focusing particularly on the quantum efficiency of TiO2-coated optical fiber textiles for the degradation of toluene and formaldehyde, and assessing the influence of activated carbon (AC) incorporation on this efficiency. We also analyze the role of light on photocatalytic degradation and breakthrough time of AC/TiO2 materials under various coupling configurations, including: (i) physically separated AC and photocatalyst, (ii) photocatalyst deposited on AC-coated optical fiber textiles, and (iii) partial deposition of photocatalyst on AC.

Finally, we explore strategies to enhance AC desorption by implementing a heated filter and evaluate the photocatalytic performance of a thermally activated photocatalytic optical filter.

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Pollutants

Two volatile organic compounds, formaldehyde (99%) and toluene (99%), were supplied by Sigma Aldrich (Saint Quentin Fallavier, France) and used without further purification.

2.2. Materials

2.2.1. Adsorbent (Activated Carbon)

Five types of activated carbon (AC) have been used, three AC under textile form by Actitex (Saint Jean de Braye, France): JSR-14714 Actitex (FC1201), thickness: 1 mm; a non-woven filter materials supplied by Ahlstrom (Helsinki, Finland): Ahlstrom AC, 350 g/m2, S = 800 m2/g; and Dolder foam (thickness 5.5 mm, porous volume: 0.31 m3/g) from Dolder firm (Basel, Switzerland), a powder named AC Aquasorb (1050 m2/g) from Jacobi Carbons Group (Kalmar, Sweden) and granule SKL (Bombay, India): S = 716 m2/g and porous volume: 0.28 m3/g.

2.2.2. Photocatalyst

Three industrial photocatalytic materials were used, composed of non-woven filter materials one is supplied by the manufacturer Maire ATN (Lyon, France) which contain 280 g/m2 of AC and 30 g/m2 of TiO2 PC500 named Maire CA + TiO2, and the two other materials supplied by the manufacturer Ahlstrom Corp (Helsinki, Finland), one made of cellulose and polyester containing only TiO2 P25 photocatalyst, the other containing AC (350 g/m2) and TiO2 P25 (8.8 g/m2). Eurocarb (Reading, UK) supplies activated charcoal used in all these materials and has a surface area of 800 m2/g. AC was present between two layers of non-woven fibres made of cellulose and polyester.

PC500 Titania supplied by Cristal Global (Jeddah, Saudi Arabia) is anatase phase with a specific surface area of about 350 m2·g−1.

2.2.3. Textile Support

A polymer textile (polyester) composed of optical fibers from Brochier technologies (Villeurbanne, France) has also been employed as support [20]. This support was first protected by a coating of silica and then by TiO2 P25 (80% anatase and 20% rutile) as previously described [21,22]. In some cases, this support has been coated by AC Aquasorb with or without TiO2 P25.

TiO2 P25 supplied by Evonik (Essen, Germany) is composed of 80% anatase phase and 20% rutile phase with a specific surface area of about 50 m2·g−1.

A new configuration of textile was developed in order to obtain a luminous, heating, adsorbing, and photocatalytic textile. This innovative textile combines stainless-steel heating yarn and optical fibers woven with polyester yarn. The textile was firstly coated by TiO2 as previously described [21,22] and then AC was deposited as described below.

The AC impregnation was carried out by roller: A solution containing the AC Aquasorb powder is rolled onto the textile to obtain the desired quantity. Then the impregnated textile is placed in an oven at 70 °C for 10 min to dry it. When it comes out of the oven, the excess AC is removed by lightly tapping the fabric.

2.3. Experimental Devices and Protocols

Main experiments were conducted in continuous through flow mode using an annular flow-through reactor, made of stainless steel and equipped with an optical Pyrex glass window of 17 cm2, and a PLL UV lamp center at 365 nm (Figure S1a). In the last part of our study, a new type of reactor has been used, allowing to work with luminous and heating textiles. In this setup, two luminous and heating textiles, each measuring 300 mm in length and 100 mm in width, were installed inside a rectangular reactor with a height of 30 mm. The textiles were positioned at approximately equal intervals along the axial flow direction (Figure S1b).

Gaseous formaldehyde is generated with a PUL 100 permeation system (Fives Pillard, Marseille, France), by heating porous tubes filled with solid paraformaldehyde (95%, Sigma Aldrich, Saint. Quentin Fallavier, France) and driven by a dry air flow. Gaseous toluene is produced in a double dilution VOCs generator (Bronkhorst, Ruurlo, The Netherlands) where liquid toluene (99.5% Sigma Aldrich, Saint Quentin Fallavier, France) is nebulized by a µFlow liquid mass flow controller (Bronkhorst, Ruurlo, The Netherlands) and driven by dry air flow. Additional dry and/or humid air flows are adjusted to achieve the desired final flow and hygrometry conditions. A schematic of the experimental setup is shown in Figure S2.

Pollutant concentrations were first equilibrated and homogenized externally (Step 1). The pollutant was then introduced into the reactor and kept in the dark until a steady-state concentration was achieved (Step 2). After this stabilization, UV irradiation was applied and maintained until the pollutant concentration reached a new equilibrium (Step 3). Toluene and formaldehyde were analyzed with a PerkinElmer (Waltham, MA, USA) Clarus 580 at 100 °C using two columns installed in parallel, the Rtx-5 column and RT-QBond. The detector for the VOCs was a pulsed discharge Helium ionization detector (PDHID) with 2% Ar in He.

2.4. Characterization of Materials

-The quantification of Ti is obtained with a sample of 1 cm2 dissolved in HF solution and analyzed with an ICP-AES “Activa” from Jobin Yvon (Longjumeau, France).

The quantification of AC deposited on the optical fiber textile was made by weighing the materials before and after deposition of AC.

-BET and porosity measurement were performed using 3 Flex de Micromeritics (Norcross, GA, USA) apparatus after degassing on a SmartVacPrep Micromeritics apparatus for 5 h at 80 °C.

-Optical microscopy analysis was made by using Olympus (Tokyo, Japan) microscope.

-Permeability measurements were made by AIR PERMEABILITY TESTER 37/S-BRANCA IDEALAIR (Mercallo, Italy).

Test conditions of the Air permeability tester: Volume: 10 Lt, Test area: 10 cm2, Pressure: 100 Pa.

-The analysis of products formed on a photocatalytic optical fiber textile, obtained after a reaction with 4 ppm of toluene and UV irradiation, was performed by RMN liquid 1H using an Bruker (Billerica, MA, USA) AVANCE HD 400 spectrometer with a BBFO 5 mm z-gradient probe. The optical fiber textile was immersed in DMSO, and after stirring, the liquid was collected and placed in an NMR tube for 5 min. An initial analysis was performed immediately after filling the tube, but the spectral resolution was unsatisfactory due to the dispersion of solid particles in the liquid. After an overnight period, the solid settled at the bottom of the tube, and further analyses were conducted.

Toluene and formaldehyde were analyzed with a PerkinElmer Clarus 580 at 100 °C using two columns installed in parallel, the Rtx-5 column and RT-QBond. The detector for the VOCs was a pulsed discharge Helium ionization detector (PDHID) with 2% Ar in He.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Impact of Type of Materials on Toluene and Formaldehyde Adsorption

3.1.1. Toluene Adsorption

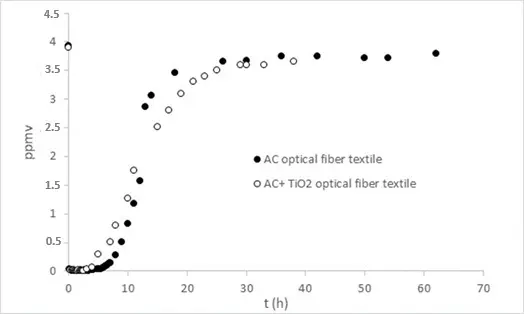

Figure 1 represents the adsorption of toluene as a function of time in the presence of different materials containing activated carbon. Two Ahlstrom papers where AC was present between two layers of non-woven fibers made of cellulose and polyester, and in one case TiO2 PC500 (18 g/m2) is also present. One Maire material similar to Ahlstrom paper but containing a little less AC and more TiO2 (30 g/m2), an AC textile (Actitex), and an AC foam (Dolder foam), some AC granule SKL, and an optical fiber textile where AC has been coated. In each case, a surface of about 17 cm2 was filled with materials. The amount of AC used is given in Table 1.

Table 1. Characteristic, amount of activated carbon materials used, and adsorption of toluene per gram of AC obtained under a flow of 500 mL/min of toluene and 50% HR in an annular flow-through reactor, equipped with an optical Pyrex glass window of 17 cm2, in the presence of different materials containing AC.

|

Materials |

SBET (AC) (m2/g) |

Amount AC (mg/cm2) |

Adsorbed Toluene/g (AC) (mg/g) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Optical Fiber Textile + AC 4.5 |

1050 |

4.5 ± 0.5 |

66 ± 4 |

|

Actitex |

955 Micropore volume: 0.25 cm3/g Micropore area: 620 m2/g External surface area: 335 m2/g |

4.8 ± 0.5 |

90 ± 4 |

|

Maire AC + TiO2 (PC500) |

527 Micropore volume: 0.16 cm3/g Micropore area: 409 m2/g External surface area: 118 m2/g |

28 ± 1 |

83 ± 4 |

|

Ahlstrom AC + TiO2 (P25) |

693 Micropore volume: 0.25 cm3/g Micropore area: 625.8 m2/g External surface area: 67 m2/g |

31 ± 1 |

52 ± 4 |

|

Ahlstrom AC |

750 Micropore volume: 0.269 cm3/g Micropore area: 674 m2/g External surface area: 77 m2/g |

35 ± 1 |

67 ± 4 |

|

Dolder Foam |

885 Micropore volume: 0.314989 cm3/g Micropore area: 778.9256 m2/g External surface area: 106 m2/g |

2800 ± 10 |

|

|

Granule SKL |

716 |

5000 ± 10 |

Figure 1. Adsorption of toluene in an annular flow-through reactor, equipped with an optical Pyrex glass window of 17 cm2, in the presence of different materials containing AC. Optical Fiber textile + AC 4.5 (full circle); Actitex (full square); Ahlstrom AC + TiO2 (Diamond); Ahlstrom (triangle); Maire AC + TiO2 (empty circle); Dolder Foam (empty square); granule SKL (empty triangle).

From Figure 1, it is observed that Dolder foam and SKL granule behave differently. After more than a hundred hours, only a small amount of toluene is released. This behavior is due to the important amount of activated carbon (AC) present in both materials, with the greater adsorption on SKL granule being attributed to the larger quantity used.

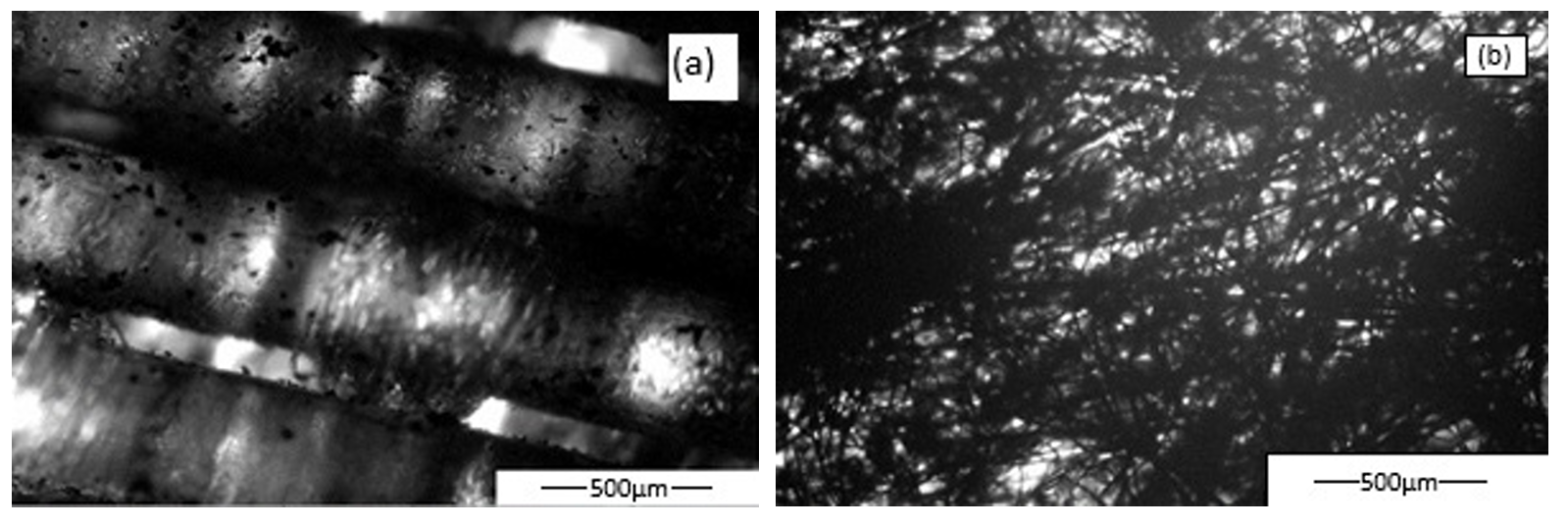

At a similar amount of AC and a similar surface area of AC, better toluene adsorption is found for Actitex material compared to AC coating on optical fiber textile. This behavior could be explained by a less homogeneous repartition of AC on optical fiber textile (Figure 2) compared to Actitex, which is a commercial AC filter for hoods.

Figure 2. Optical microscopy of (a) optical textile coated with AC and of (b) Actitex.

It is also noted that the presence of TiO2 alters the dynamics of toluene adsorption, reducing the breakthrough time and decreasing of about 20% the quantity of toluene adsorbed per gram of AC, probably due to some adsorption site being blocked by the TiO2 particles. It is also interesting to underline that the dynamic of toluene adsorption observed for Ahlstrom and Maire materials containing TiO2 is similar, showing the impact of TiO2 on AC adsorption Figure 2.

3.1.2. Formaldehyde Adsorption

Formaldehyde adsorption was first performed in the annular flow-through reactor, equipped with an optical Pyrex glass window of 17 cm2. However, the adsorption is very low, less than 1 mg HCHO per gram of Aquasorb AC, approximately 100 times less than toluene.

We therefore also determine the adsorption using another reactor, allowing us to work with a larger surface area of materials.

The results are presented in Table 2 and illustrated in Figure S2. They show that the three materials exhibit similar adsorption properties for HCHO, confirming that all three adsorb significantly less HCHO compared to toluene—approximately 100 times less. It will be interesting in the future to continue this work by working with TiO2/ACF as described in the bibliography [15]. Indeed, this material seems to be very efficient for formaldehyde adsorption.

Table 2. Amount of activated carbon materials used per cm2 of materials and formaldehyde adsorbed per gram of AC obtained under a flow of 1 L/min of HCHO, 50% HR in a tangential flow reactor, with 200 cm2 of different materials containing AC.

|

Materials |

HCHO Adsorbed/g AC (mg/g) |

|---|---|

|

Optical Fiber Textile + AC 2.6 |

0.6 ± 0.1 |

|

Maire AC + TiO2 |

0.5 ± 0.1 |

|

Actitex |

0.8 ± 0.1 |

The results are presented in Table 2 and illustrated in Figure S2. They show that the three materials exhibit similar adsorption properties for HCHO, confirming that all three adsorb significantly less HCHO compared to toluene—approximately 100 times less.

Accordingly, the following sections of the manuscript will mainly address the results concerning toluene and be dedicated to optical fiber textile.

3.2. Effect of Different Parameters on Toluene Adsorption Using Optical Fiber Textiles

3.2.1. Impact of the Amount of Aquasorb AC Coating on Optical Fiber Textiles

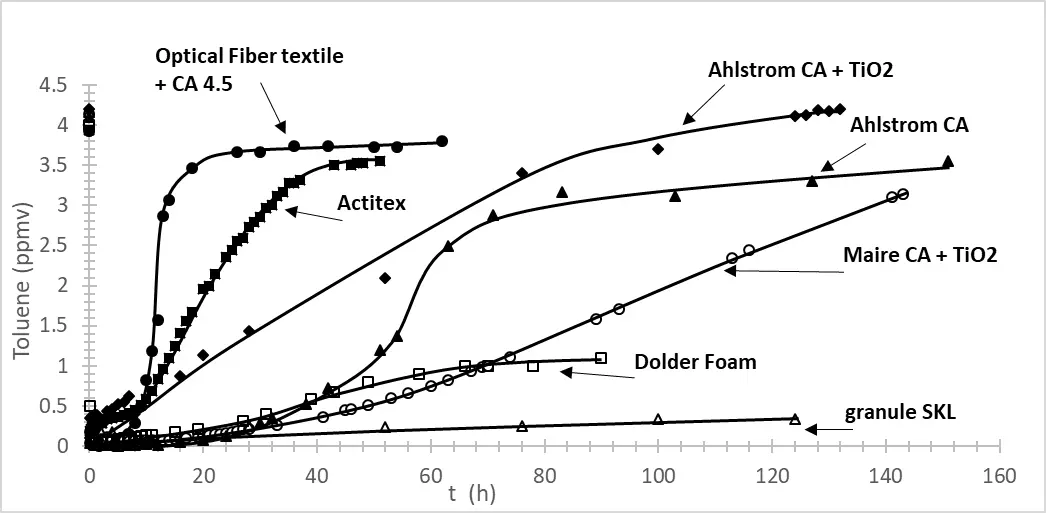

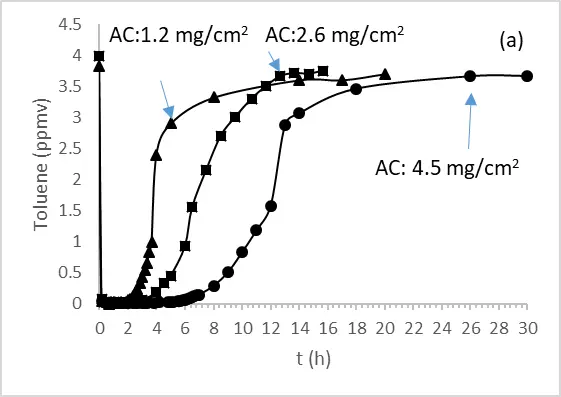

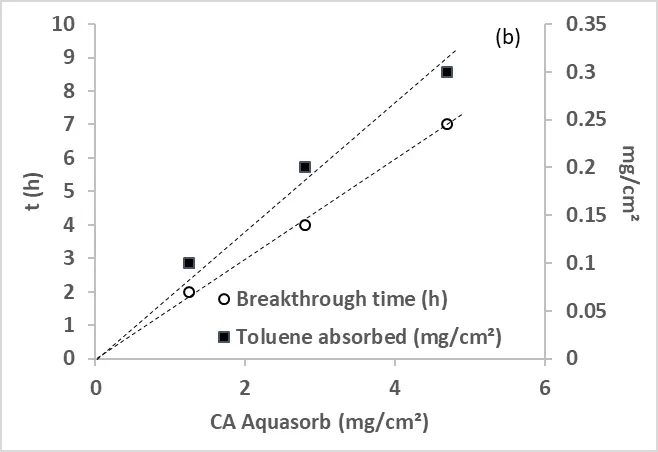

The adsorption of toluene has been performed in the presence of an optical fiber textile coated with different amounts of activated carbon using an annular flow-through reactor, equipped with an optical Pyrex glass window of 17 cm2 under a flow of 500 mL/min and 50% of humidity (Figure 3a).

|

|

Figure 3. (a) Adsorption of toluene on optical fiber textile coated with different amounts of Aquasorb AC in an annular flow-through reactor, equipped with an optical Pyrex glass window of 17 cm2. (500 mL/min, 50% HR), (b) toluene adsorbed per cm2 as a function of AC Aquasorb coated in mg/cm2.

From Figure 3a, we evaluated the breakthrough time and the amount of toluene adsorbed, showing that both parameters increase linearly with the amount of AC present on the optical fiber textile (Figure 3b).

3.2.2. Impact of the Presence of TiO2 on Aquasorb-Activated Carbon Coated on Optical Fiber Textiles

As previously observed with Ahlstrom AC materials, both with and without TiO2, the presence of TiO2 affects the dynamics of toluene adsorption, leading to a shorter breakthrough time and reduced adsorption capacity. However, due to the low amount of activated carbon, these changes are less pronounced compared to Ahlstrom materials (Figure 4).

3.3. Photocatalytic Properties

3.3.1. Impact of Irradiance on VOC Degradation in the Presence of Photocatalytic Optical Fiber Textile

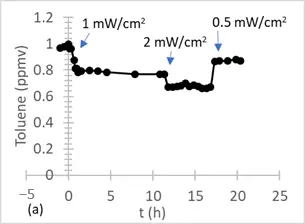

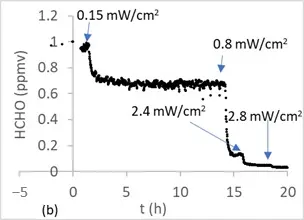

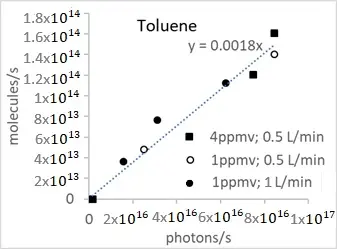

Degradation of toluene and formaldehyde was performed in continuous flow and 50% HR using optical fiber textiles containing TiO2 P25 under different levels of irradiance. For toluene, the impact of irradiance was also studied under two continuous flow rates (1 L/min and 0.5 L/min) and two initial concentrations (4 ppmv and 1 ppmv).

Figure 5 shows the degradation of 1 ppmv of toluene (a) and 1 ppmv of formaldehyde (b) under a flow of 1 L/min and 50% HR using 17 cm2 of optical fiber textile coated with TiO2 P25. Similar experiments were also performed using either 4 ppmv or 1 ppmv toluene at a flow rate of 1 L/min.

|

|

Figure 5. Photocatalytic degradation of 1 ppm of toluene (a) and 1 ppm of formaldehyde (b) under different irradiations in an annular flow-through reactor (1 L/min), equipped with an optical Pyrex glass window of 17 cm2, in the presence of optical fiber textile coated with TiO2 P25 (1.5 mg/cm2).

According to Figure 5, the disappearance rate of toluene and formaldehyde is represented as a function of irradiance values. Figure 6 shows clearly that the disappearance rate of both VOCs is directly proportional to irradiation, whatever the initial VOC concentration and the flow rate, until about 90% of degradation.

|

|

|

(a) |

(b) |

Figure 6. Disappearance rate of toluene (a) and formaldehyde (b) as a function of irradiance obtained in an annular flow-through reactor, equipped with an optical Pyrex glass window of 17 cm2, in the presence of an optical fiber textile coated with TiO2 P25 (1.5 mg/cm2).

From Figure 6, we obtain an energy efficiency defined as the number of molecules removed per second divided by the number of photons emitted per second, of about 0.18% and 1.3% for toluene and formaldehyde, respectively. Interestingly, the difference between the two values corresponds about to the difference in the number of carbon present in the two molecules, suggesting that the energy efficiency of disappearance will be proportional to the number of carbon present. This point needs to be verified using other VOC molecules.

When compared to the toluene degradation performance achieved with Alstrom paper containing 8.8 mg/cm2 of TiO2 P25, the photocatalytic optical fiber, incorporating 1.5 mg/cm2 of TiO2, exhibits a lower degradation which is likely due to the lower TiO2 P25 loading, as previous studies have shown that the efficiency is proportional to the TiO2 quantity up to approximately 2 to 3 mg/cm2, which has been established as the optimal loading density [23].

This hypothesis was verified by performing the photocatalytic degradation of toluene in the presence of 3 mg/cm2 of TiO2, using 4 ppm of toluene at a flow of 500 mL/min (Figure S4). In this case, 0.9 ppm was degraded, corresponding to a quantum yield of 0.0029, slightly less than double that obtained using 1.5 mg/cm2 of TiO2, indicating that 1.5 mg/cm2 of TiO2 was not sufficient to absorb all photons emitted in accordance with our previous publication [23]. This result also shows that the performance of this photocatalytic optical fiber textile is equivalent to that of the Ahlstrom paper tested.

After the degradation of toluene, a yellow coloration appears on the optical fiber textiles, with the intensity of the yellow color increasing as the initial toluene concentration rises. The analysis by liquid NMR 1H of the extraction of the yellow coloration (Figure S5) shows the formation of carboxylic groups at 11.7 ppm and aldehyde groups observed between 10.1 and 9.9 ppm and peaks situated between 8.1 ppm and 7.8 ppm correspond to aromatic compounds such as benzaldehyde or benzoic acid, while peaks between 7.3 ppm and 7.5 ppm indicate the presence of unreacted toluene. Their formation is in accordance with the results already observed [24,25].

This result shows that at high initial concentrations of toluene, oxidation products are formed and remain adsorbed on the photocatalytic materials. However, it is important to note that these products disappear after UV treatment in air.

3.3.2. Impact of AC on Toluene Photocatalytic Degradation and Breakthrough Time

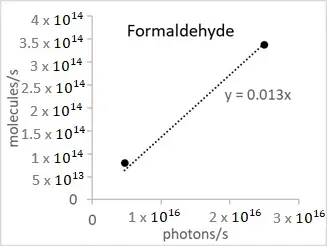

The impact of the presence of activated carbon (AC) has been evaluated on the photocatalytic elimination of toluene using three types of couplings involving activated carbon (AC) as the adsorbent and TiO2 as the photocatalyst.

-

-

The combination of two commercial materials, where an AC adsorbent support (Actitex) is paired with a photocatalytic support (Actitex coupled with Ahlstrom photocatalytic paper) (Figure 7a).

-

-

A commercial material containing AC, arranged in a sandwich between two cellulose layers, with small deposits of TiO2 dispersed on the surface (e.g., MAIRE AC + TiO2 media) (Figure 7b).

-

-

The hybrid AC/TiO2 optical fiber textile (Figure 7c).

When the AC adsorbent support and the TiO2 photocatalytic support are combined, the release time is significantly extended if irradiation starts simultaneously with adsorption, increasing from 3 h to about 12 h (Figure 7a). The removal of toluene appears to be slightly enhanced when compared to photocatalytic degradation using the photocatalytic support alone. However, this enhancement is minimal, and the inclusion of the adsorbent support results in reduced permeability (from 902 L/m2/s to 478 L/m2/s, thereby prolonging the contact time with the photocatalyst. The observed change in permeability is likely responsible for this improvement, as it leads to an increased contact duration between the toluene and the photocatalyst. The longer breakthrough time of toluene observed in the separated configuration can be explained by the fact that, from the moment irradiation begins, a portion of the toluene is directly degraded rather than being adsorbed. As a result, fewer adsorption sites become occupied, and more active sites remain available for capturing the incoming toluene, which delays breakthrough. Moreover, changes in permeability in this configuration also contribute to this extended breakthrough time.

Unlike the previous case, with the MAIRE textile (Figure 7b), where AC is sandwiched between two cellulose layers, with TiO2 partially deposited as small clusters on the surface, toluene is released more rapidly when the material is irradiated. This difference may be attributed to the direct contact between TiO2 and AC. Consequently, the intermediates formed are likely to have a greater impact on toluene adsorption by blocking AC sites situated below TiO2.

In the case of the optical fiber textile where both AC and TiO2 are deposited on the support (Figure 7c), initial irradiation appears only slightly to reduce breakthrough time, but impacts the adsorption kinetics, which takes a longer time to be completely released. This behavior could be attributed to only one part of TiO2 in direct contact with AC. So, in other words, this case represents a hybrid between the behaviors observed with the coupling of two independent materials and those where TiO2 is present as small clusters on AC support, thus in closer contact. Regarding photocatalytic efficiency, the presence of AC does not improve performance. It may even have a detrimental effect on the final toluene removal, likely due to the lower number of active sites available for the TiO2 absorption blocked by AC, but also due to the presence of intermediates adsorbed on AC near TiO2, which are in competition for degradation. In this case, the photocatalytic efficiency and the quantum efficiency were reduced from about 10%.

Figure 7. (a–c) Photocatalytic degradation of toluene in the presence of Ahlstrom paper TiO2 and Ahlstrom paper TiO2 on Actitex (a), in the presence of MAIRE AC + TiO2 materials with and without UV (b); in the presence of optical fiber textile TiO2, Optical fiber textile AC + TiO2 (c). Materials with AC and TiO2 were either initially irradiated or irradiated only after adsorption (lamp PLL 18 W, 2 mW/cm2).

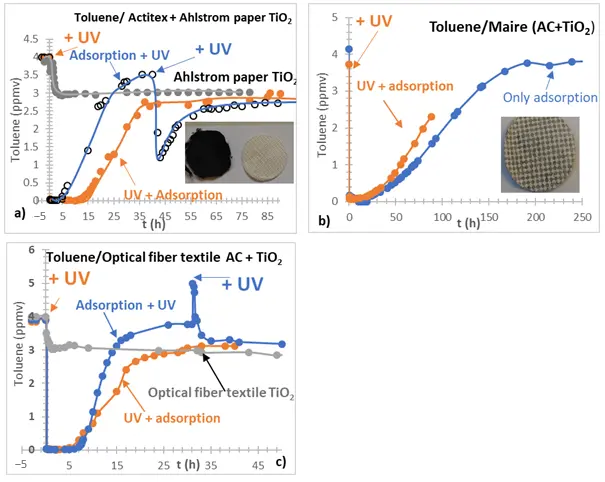

3.3.3. Investigation of Heating (Photocatalytic) Textile

The results described below indicate that a direct or intimate combination of an adsorbent with a photocatalyst does not enhance the degradation efficiency of volatile organic compounds (VOCs), nor does it prolong the desorption time. However, using two independent materials—an adsorbent and a photocatalyst—leads to a noticeable reduction in breakthrough time, although the overall degradation efficiency remains unchanged.

These findings are consistent with the study by Gauthier et al. [19] on the dynamic degradation of ethyl hexanoate. The authors suggest that the lack of synergy between adsorption and photocatalysis likely results from insufficient desorption of the VOC from the adsorbent surface toward the photocatalyst, thereby limiting the mass transfer necessary for photocatalytic degradation. A second reason could also be the low rate of photocatalytic degradation.

Based on the hypothesis of Gauthier et al. [19], a new hybrid material that integrates both heating wires (on the activated carbon side) and optical fibers (on the TiO2-coated side) was investigated. The aim is to promote thermal desorption and enhance photocatalytic activity through spatially controlled coupling of the two functions. In this case, a reactor was developed to be able to introduce a luminous heating textile (Figure S1b). In this reactor, two textiles were used. Each of them has an AC coating on the side where the heating wires are and TiO2 on the opposite side with optical fibers.

The first experimental phase focused on evaluating the impact of temperature and adsorbed quantity on the desorption of toluene. Our results show that desorption is negligible at 40 °C. It begins to occur at 50 °C and increases with temperature (Figure 8a). However, the amount of toluene desorbed is closely related to its initial concentration present on the adsorbent textile before heating. The higher the toluene concentration, the more desorption occurs. The second phase involved studying the effect of simultaneous UV irradiation during thermal desorption at 50 °C under an airflow. Using this textile configuration and a reactor operating primarily under a sweeping flow, the toluene concentration did not decrease; in fact, even a slight increase was observed under UV light (Figure 8b). This suggests that the operating mode does not facilitate effective photocatalytic degradation in this setup. Is it due to the type of flow or to the heating of the photocatalyst and the low photocatalytic rate?

Figure 8. (a,b) Impact amount of toluene adsorbed and of temperature on its desorption using a heating textile. (b) Amount of toluene adsorbed in presence and absence of UV irradiation.

These results lead us to consider a future configuration operating in a cross-flow mode, which could enhance interactions between desorbed VOCs and the photocatalytic surface, as well as a loop where a pulse of desorbed VOCs would have enough time to degrade the VOC. In the future, we propose working with a continuous flow reactor equipped with a heating AC filter and TiO2 materials, irradiated from the start, but heated in pulses before the breakthrough time is reached. These pulses would be directed into a loop, allowing VOCs to be treated in static mode, providing sufficient time for their complete decomposition. During the photocatalytic treatment, the continuous flow reactor would continue to operate. Periodically, pulses of desorbed VOCs would be introduced into the photocatalytic treatment loop. The development of advanced materials combining heated adsorbents with integrated optical fibers and a TiO2-based photocatalytic layer—either on the opposite side or separated by a filter (avoiding heating of TiO2)— will be tested in this new reactor currently under development.

4. Conclusions

The study examines the adsorption behavior of toluene and formaldehyde on optical fiber–based textiles impregnated with activated carbon, including configurations with and without TiO2. It also investigates how activated-carbon distribution and material permeability influence overall adsorption performance. The comparison of photocatalytic performance between optical fiber textiles coated with 1.5 mg/cm2 and 3 mg/cm2 of TiO2 indicates that the optimal loading is around 3 mg/cm2, consistent with our previous findings. Below this level, UV-A light is not fully absorbed, which is reflected in the measured quantum efficiencies for toluene degradation: 0.18% at 1.5 mg/cm2 and 0.29% at 3 mg/cm2 of TiO2.

Then the study highlights the significant impact of AC configuration and integration in photocatalytic systems on toluene removal efficiency. The effect varies depending on the coupling method. When AC is used as a separate filter in combination with TiO2, the toluene breakthrough time is extended when UV irradiation begins simultaneously with the adsorption process. Although only a modest improvement in degradation is observed, this may be attributed to changes in system permeability induced by the presence of AC materials. In contrast, when AC and TiO2 are co-deposited—either on optical fiber textiles or on adsorbent substrates containing TiO2 clusters—when UV irradiation starts from the beginning of adsorption, the breakthrough time is slightly reduced. This is likely due to the formation of oxidation products on the AC surface, which alters the adsorption kinetics. Moreover, in this configuration, a slight decrease (approximately 10%) in the toluene degradation rate is observed, likely due to the reduction of available photocatalytic active sites.

To enhance the desorption of adsorbed compounds and facilitate their transfer to photocatalytic materials, we tested a heated photocatalytic optical fiber filter. We found that VOC desorption was possible at a minimal temperature of 50 °C, and that desorption efficiency depended on the concentration of compounds on the adsorbent. However, the disappearance rate did not improve, possibly due to the use of a sweeping flow reactor and the low photocatalytic rate.

Based on these findings, we propose future research to explore two configurations involving a combination of heating adsorbent materials and photocatalysts. The first setup would involve adsorption and photocatalytic treatment without heating, using a through-flow system. The second configuration would introduce heating pulses before breakthrough time, where the process would operate in a static mode while the continuous flow would continue to be adsorbed and treated in the first section.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be found at: https://www.sciepublish.com/article/pii/799, Figure S1: (a) Annular reactor used in tangential mode (OUT 1) or in through mode (OUT 2). In our case, main of the experiments were done in through mode except those made with heat. (b) photo of the reactor used with luminous heating textiles and arrangement of these two textiles in the reactor; Figure S2: Scheme of the experimental setup; Figure S3: Formaldehyde adsorption using 100 cm × 200 cm of three materials Optical fiber textile + CA2.6, Actitex and Maire CA + TiO2; Figure S4: Photocatalytic degradation of toluene in presence de TiO2 (3 mg/cm2) coated on optical fiber textile under 4 ppm of toluene at 500 mW/L and 2 mW/cm2 of UV-A. Figure S5: NMR 1H of the extraction of the yellow coloration obtained after photocatalytic degradation of toluene on optical fiber textile coated with TiO2 P25.

Statement of the Use of Generative AI and AI-Assisted Technologies in the Writing Process

We thank OpenAI for using ChatGPT to improve the English in this manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We thanks C. Lorentz for RMN analysis.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: C.G., L.L., L.P.; Methodology: C.G., L.L., F.D.; Validation: C.G., L.P.; Formal Analysis: E.Z., C.G.; Investigation: E.Z., F.D., J.F.N.; Data Curation: E.Z., C.G.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation: C.G.; Writing—Review & Editing: C.G., L.L., L.P., F.D.; Visualization: E.Z., C.G.; Supervision: F.D., C.G., L.L., L.P.; Project Administration: C.B.; Funding Acquisition: C.B.

Ethics Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Funding

This research was funded by the French ANR agency, grant number ANR-AAPG2022-CES04.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Wang D, Li X, Zhang X, Zhao W, Zhang W, Wu S, et al. Spatial distribution of health risks for residents located close to solvent-consuming industrial VOC emission sources. J. Environ. Sci. 2021, 107, 38–48. doi:10.1016/j.jes.2021.01.014. [Google Scholar]

- Sonne C, Xia C, Dadvand P, Targino AC, Lam SS. Indoor volatile and semi-volatile organic toxic compounds: Need for global action. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 62, 105344. doi:10.1016/j.jobe.2022.105344. [Google Scholar]

- Formenti M, Juillet F, Meriaudeau P, Teichner SJ. Heterogeneous photocatalysis for partial oxidation of paraffins. Chem. Technol. 1971, 1, 680–681. [Google Scholar]

- Boyjoo Y, Sun H, Liu J, Pareek VK, Wang S. A review on photocatalysis for air treatment: From catalyst development to reactor design. Chem. Eng. J. 2017, 310, 537–559. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2016.06.090. [Google Scholar]

- MiarAlipour S, Friedmann D, Scott J, Amal R. TiO2/porous adsorbents: Recent advances and novel applications. J. Hazard. Mater. 2018, 341, 404–423. doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2017.07.070. [Google Scholar]

- Zou W, Gao B, Ok YS, Dong L. Integrated adsorption and photocatalytic degradation of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) using carbon-based nanocomposites: A critical review. Chemosphere 2019, 218, 845–859. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.11.175. [Google Scholar]

- Sampath S, Uchida H, Yoneyama H. Photocatalytic Degradation of Gaseous Pyridine over Zeolite-Supported Titanium Dioxide. J. Catal. 1994, 149, 189–194. doi:10.1006/jcat.1994.1284. [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Matsumoto A, Nishimiya N, Tsutsumi K. Preparation and characterization of TiO2 incorporated Y-zeolite. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 1999, 157, 295–305. doi:10.1016/S0927-7757(99)00052-7. [Google Scholar]

- Yoneyama H, Torimoto T. Titanium dioxide/adsorbent hybrid photocatalysts for photodestruction of organic substances of dilute concentrations. Catal. Today 2000, 58, 133–140. doi:10.1016/S0920-5861(00)00248-0. [Google Scholar]

- Monneyron P, De La Guardia A, Manero MH, Oliveros E, Maurette MT, Benoit-Marquié F. Co-treatment of industrial air streams using A.O.P. and adsorption processes. Int. J. Photoenergy 2003, 5, 167–174. doi:10.1155/S1110662X03000291. [Google Scholar]

- Thevenet F, Guaïtella O, Herrmann JM, Rousseau A, Guillard C. Photocatalytic degradation of acetylene over various titanium dioxide-based photocatalysts. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2005, 61, 58–68. doi:10.1016/j.apcatb.2005.03.015. [Google Scholar]

- Kim T, Yoo K, Kim MG, Kim YH. Photo-Regeneration of Zeolite-Based Volatile Organic Compound Filters Enabled by TiO2 Photocatalyst. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 2959. doi:10.3390/nano12172959. [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, Kim S, Lee S. Activated carbon modified with polyethyleneimine and MgO: Better adsorption of aldehyde and production of regenerative VOC adsorbent using a photocatalyst. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2023, 631, 157565. doi:10.1016/j.apsusc.2023.157565. [Google Scholar]

- Ao CH, Lee SC. Indoor air purification by photocatalyst TiO2 immobilized on an activated carbon filter installed in an air cleaner. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2005, 60, 103–109. doi:10.1016/j.ces.2004.01.073. [Google Scholar]

- Liu RF, Li WB, Peng AY. A facile preparation of TiO2/ACF with C Ti bond and abundant hydroxyls and its enhanced photocatalytic activity for formaldehyde removal. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018, 427, 608–616. doi:10.1016/j.apsusc.2017.07.209. [Google Scholar]

- Shu Y, Xu Y, Huang H, Ji J, Liang S, Wu M, et al. Catalytic oxidation of VOCs over Mn/TiO2/activated carbon under 185 nm VUV irradiation. Chemosphere 2018, 208, 550–558. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.06.011. [Google Scholar]

- Biomorgi J, Haddou M, Oliveros E, Maurette MT, Benoit-Marquié F. Coupling of Adsorption on Zeolite and V-UV Irradiation for the Treatment of VOC Containing Air Streams: Effect of TiO2 on the VOC Degradation Efficiency. J. Adv. Oxid. Technol. 2010, 13, 107–115. doi:10.1515/jaots-2010-0114. [Google Scholar]

- Derakhshan-Nejad A, Rangkooy HA, Cheraghi M, Yengejeh RJ. Removal of ethyl benzene vapor pollutant from the air using TiO2 nanoparticles immobilized on the ZSM-5 zeolite under UVradiation in lab scale. J. Environ. Health Sci. Eng. 2020, 18, 201–209. doi:10.1007/s40201-020-00453-4. [Google Scholar]

- Gauthier E, Thivel PX, Delpech F, Roux JC, Ozil P. An Adsorption and Photocatalysis Study of Ethyl Hexanoate. Int. J. Chem. React. Eng. 2008, 6, 1–19. doi:10.2202/1542-6580.1641. [Google Scholar]

- Brochier C, Deflin E, Breting T. Complexe Éclairant. Complexe Éclairant Comportant une Source Lumineuse Présentant une Nappe de Fibres Optiques. WO 2008061789A1; FR2909159A1, 30 May 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Brochier C, Deflin E, Malhomme D. Nappe Textile Dépolluante. FR2910341B1, 6 February 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Indermühle C, Puzenat E, Simonet F, Peruchon L, Brochier C, Guillard C. Modelling of UV optical ageing of optical fibre fabric coated with TiO2. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2016, 182, 229–235. doi:10.1016/j.apcatb.2015.09.037. [Google Scholar]

- Indermühle C, Puzenat E, Dappozze F, Simonet F, Lamaa L, Peruchon L, et al. Photocatalytic activity of titania deposited on luminous textiles for water treatment. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2018, 361, 67–75. doi:10.1016/j.jphotochem.2018.04.047. [Google Scholar]

- Sleiman M, Conchon P, Ferronato C, Chovelon JM. Photocatalytic oxidation of toluene at indoor air levels (ppbv): Towards a better assessment of conversion, reaction intermediates and mineralization. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2009, 86, 159–165. doi:10.1016/j.apcatb.2008.08.003. [Google Scholar]

- Blount MC, Falconer JL. Steady-state surface species during toluene photocatalysis. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2002, 39, 39–50. doi:10.1016/S0926-3373(01)00152-7. [Google Scholar]