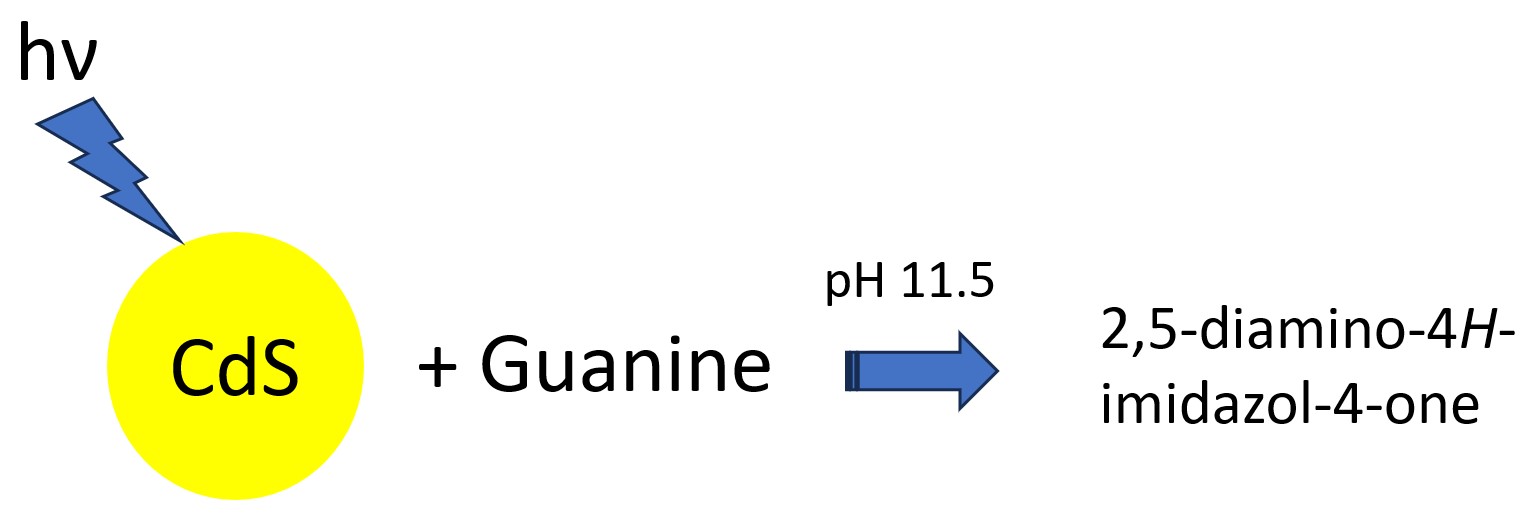

Photocatalytic Transformation of Guanine Using Colloidal CdS Nanoparticles

Received: 12 December 2025 Revised: 16 January 2026 Accepted: 26 January 2026 Published: 30 January 2026

© 2026 The authors. This is an open access article under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

1. Introduction

Cellular DNA is continuously oxidized by a variety of chemical and physical processes. The subsequent DNA damage can augment the risk of developing cancer and different ailments [1]. Among the nitrogenous bases, guanine is highly sensitive to oxidation owing to its small redox potential. It is therefore considered the most important target in DNA [2,3,4]. To comprehend the DNA damage in vivo and its biological implications, a great effort has been made to study the chemical changes of guanine under various oxidative circumstances [5]. The main oxidation product of guanine was 8-oxo-7,8-dihydroguanine (8-oxoG), which was produced under different oxidative circumstances. 8-oxoG has often been used as a biomarker in the analysis of DNA damage [6]. Consequently, the recognition of the oxidation products and comprehension of the destruction mechanism of guanine under certain oxidative circumstances can offer key insights on the DNA damage [7]. Besides 8-oxoG, imidazolone and its hydrolysis product, oxazolone, were also obtained as the oxidation products of guanine, which are mainly generated by one-electron oxidants [8,9,10] and hydroxyl radicals [11] in an oxygen rich environment. However, singlet oxygen promotes the generation of a spiroiminodihydantoin derivative [12,13]. Free radicals, particularly reactive oxygen species (ROS), are the primary agents responsible for the endogenous guanine damage [14]. The ROS comprise oxygen-derived free radical species, such as superoxide (O2−) and the hydroxyl radical (OH·), as well as oxidizing agents like hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) [15].

Semiconductor photocatalysis is an extremely promising technology due to its low cost and ability to mineralize the organic pollutants [16]. Among the semiconductor photocatalysts, CdS has been frequently employed in various redox reactions due to its low band gap and excellent visible light response [17]. Its utility for the photocatalytic hydrogen production has been demonstrated recently [18,19]. In 2019, Warjri et al. reported the catechol oxidase mimicking behaviour of CdS nanoparticles for the oxidation of L-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine [20]. Nonetheless, the literature pertaining to the use of semiconductor photocatalysts for studying the oxidation of the DNA bases is extremely scarce [21,22,23]. In this paper, the visible light driven oxidation of guanine has been presented by employing CdS colloids as a photocatalyst.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals and Instrumentation

Sodium sulphide hydrate (Na2S·H2O, 58–62%) was obtained from Himedia Private Limited (Mumbai, India). Cadmium iodide (CdI2, 99.0%) and guanine (98%) were procured from Sigma Aldrich (Burlington, VT, USA). Sodium hexametaphosphate ((NaPO3)6, 94.3%) was obtained from Qualigens (Mumbai, India). The other reagents were of analytical grade. Distilled water was utilized for the synthesis of colloidal CdS and the preparation of the solutions.

The electronic spectra were obtained using a Cary 60 UV-visible spectrophotometer (Agilent Technologies, Penang, Malaysia). An immersion-type photoreactor (Heber Scientific, Chennai, India) fitted with a 150-Watt tungsten halogen lamp was employed as the irradiation source for the photocatalytic measurements. The intensity of the lamp was 6.4 mW·cm−2. The emission from the light source was in the 360–720 nm range. The transmission electron microscopy (TEM) analysis was performed on a Tecnai F2 G20 transmission electron microscope (Thermo Fischer Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) functioning at 200 kV. The X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of the CdS particles were measured on a X-ray diffractometer (MIS Rigaku Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). The infrared spectroscopy measurements were obtained on a Bruker Alpha-II FTIR spectrophotometer (Bruker Optics, Ettlingen, Germany).

2.2. Synthesis of the Colloidal CdS Nanoparticles

The colloidal solution of CdS was prepared by a minor modification of the protocol described by Spanhel and coworkers [24]. Typically, 300 mL of distilled water was transferred to a 500 mL 3-neck flask. Subsequently, 2.4 mL of a 0.1 M CdI2 solution was slowly injected under stirring. Thereafter, 2.4 mL of 0.1 M (NaPO3)6 solution was added to the flask. Finally, 2.4 mL of a 0.1 M Na2S solution was injected into the 3-neck flask. The emergence of yellow colour revealed the formation of the colloidal CdS particles.

2.3. Photocatalytic Reaction of Guanine

The photocatalytic measurements were performed by irradiating a reaction mixture bearing 100 mL of a 2 mM guanine solution and 100 mL of colloidal CdS. The reaction mixture pH was kept at 11.5 because guanine was soluble in water only under highly basic conditions. Before illumination, the reaction mixture was agitated for 20 min and placed in the dark for 60 min to attain equilibrium. The reaction mixture was stirred uninterruptedly during the irradiation to maintain homogeneity. The advancement of the photocatalytic process was observed by employing a UV-visible spectrophotometer. The electronic spectra were measured after precipitating and removing CdS from the reaction mixture. Potassium chloride (KCl) was used for precipitating CdS from the reaction mixture.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characterization of the Colloidal CdS Nanoparticles

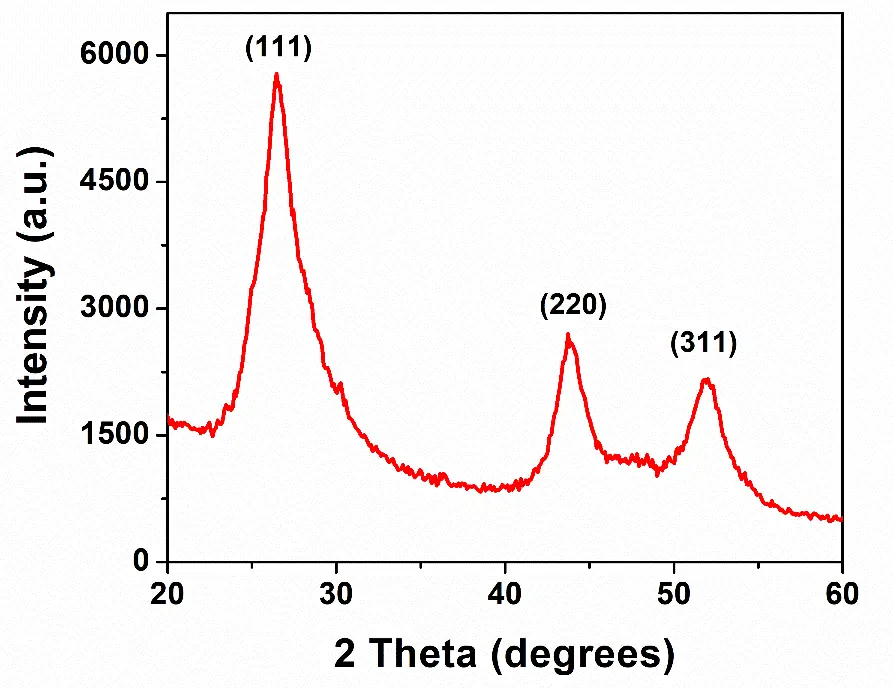

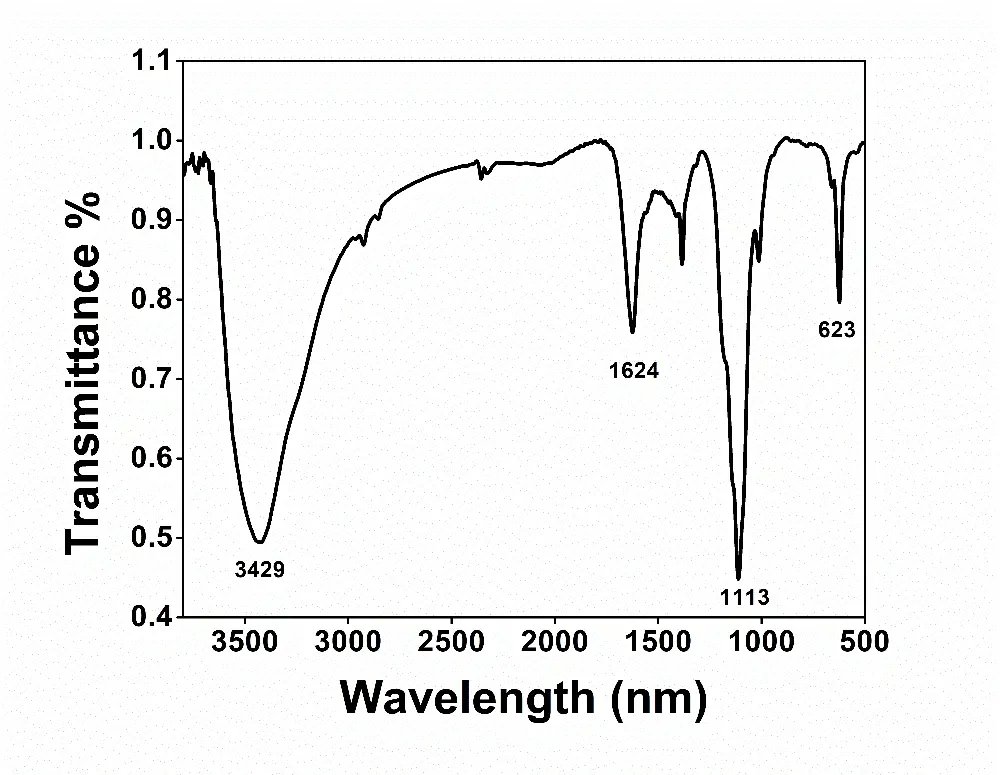

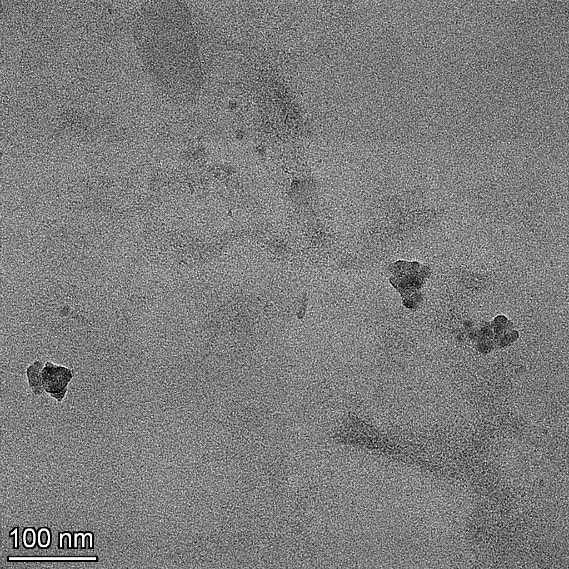

The XRD measurements were conducted to find the phase structure of the as-prepared CdS particles. The peaks seen at 2θ values of 26.5, 43.9, and 52.0 degrees were assigned to the (111), (220), and (311) crystallographic planes of cubic CdS as displayed in Figure 1. The diffraction pattern was in accordance with the reference pattern for the cubic CdS (JCPDS No. 10-454) [25]. The diameter and shape of the colloidal particles were obtained by performing the TEM measurements. As shown in Figure 2, the particles were irregular in shape and approximately 55 nm in diameter. The semiconductor was also characterized by using FTIR spectroscopy. The vibrational spectrum of the CdS nanoparticles is presented in Figure 3. The infrared bands observed at 1624 and 3429 cm−1 could be assigned to the bending and stretching vibrations of the -OH group, respectively. The -OH group vibrations were due to the water present in the sample. The sharp peak at 1113 cm−1 may be attributed to the sulphide compounds [26]. The Cd–S stretching frequency typically appears below 700 cm−1 [27]. The sharp peak observed at 623 cm−1 resulted from the stretching of the Cd–S bond in CdS.

Figure 2. TEM photograph of the CdS nanoparticles. The scale bar has been displayed on the bottom left-hand corner.

3.2. CdS-Induced Photocatalytic Reaction of Guanine

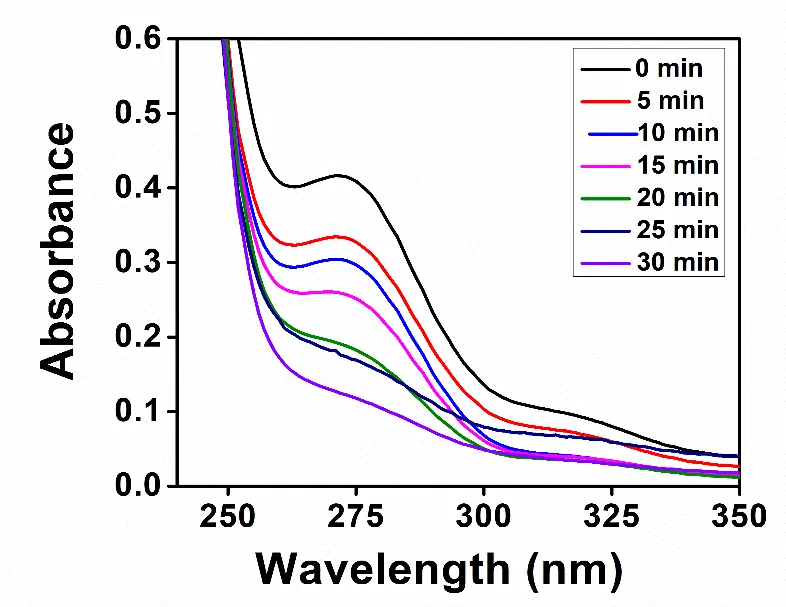

The reaction mixture bearing 1 mM guanine and the CdS nanoparticles at pH 11.5 was irradiated for different time intervals. The light source produced radiation in the 360–720 nm range. The advancement of the photocatalytic reaction was observed using a UV-visible spectrophotometer. The absorption band of guanine at 273 nm was diminished in intensity with an increase in the irradiation time, as displayed in Figure 4. It indicated that guanine was oxidized to one or more products of the photocatalytic reaction induced by CdS.

Figure 4. Electronic spectra of the reaction mixture bearing 1 mM guanine and the CdS nanoparticles at different illumination times, as indicated in the inset.

There was a negligible change in the absorption spectrum of guanine when the reaction was carried out under an inert atmosphere. It indicated that oxygen played an important role in the product formation. The irradiation of guanine in the absence of the CdS nanoparticles resulted in a negligible decline in the absorption band at 273 nm (Figure S1). Evidently, the oxidation of guanine was mainly driven by the semiconductor nanoparticles.

3.2.1. Characterization of the Guanine Reaction Product

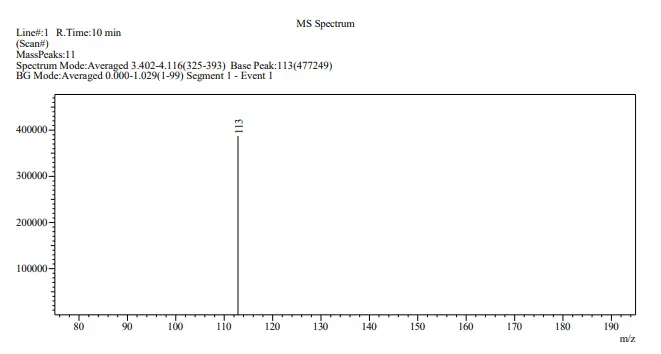

Various products of guanine oxidation have been reported by the earlier workers [10,28,29]. For example, Razskazovskiy and coworkers reported that 2,5-diaminoimidazolone was the major product when using one-electron oxidants, such as free radicals and triplet photosensitizers. Two other products were revealed as the dimers of guanine based on the mass-spectral measurements [28]. In the present work, LC-MS was employed to identify the products of the catalytic process induced by CdS. The LC-MS analysis was performed on a C18 reverse–phase column. The mobile phase flow rate was 1.0 mL·min−1. The LC-MS spectrum of the 30 min irradiated reaction mixture containing 1 mM guanine and the CdS nanoparticles has been presented in Figure 5. A peak at m/z value of 113 was obtained at a retention time of 10 min which matched with the (M + H) value for 2,5-diamino-4H-imidazol-4-one. Since only one peak was observed in the LC-MS spectrum displayed in Figure 5, it is suggested the formation of only one product of the photocatalytic reaction.

Figure 5. LC-MS spectrum of the 30 min irradiated reaction mixture comprising 1 mM guanine and the CdS nanoparticles at a retention time of 10 min.

3.2.2. Mechanism of the Guanine Product Formation

The electrons and holes generated by the photoexcitation of a semiconductor generally participate in the reduction or oxidation of the reactant molecules. To investigate which of the charge carriers facilitated the formation of the product, we carried out the photocatalytic reaction of guanine in the presence of 0.2 mM ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA) and 1 mM silver nitrate (AgNO3). It is pertinent to point out here that EDTA and AgNO3 are well-known hole and electron scavengers, respectively [30,31]. The electronic spectra of guanine containing of 0.2 mM EDTA and CdS at different illumination time intervals have been presented in Figure S2. It was evident from Figure S2 that the conversion of guanine to the product was suppressed in the presence of the hole scavenger. It indicated that the photogenerated holes played a key role in the photocatalytic reaction of guanine. The electronic spectra of guanine were also measured in the presence of AgNO3 and CdS at various illumination times (Figure S3). In contrast to the experiment with the hole scavenger, the photocatalytic reaction of guanine was not affected significantly. It indicated that the photogenerated electrons were not involved in the product formation.

Based on the above results, we propose the following reaction mechanism for the product formation. The excitation of CdS resulted in the production of the electron-hole (e−-h+) pair as displayed in Equation (1). The light-generated hole intercepted the OH− ions existing in the solution to form the hydroxyl radical (OH·) as shown in Equation (2).

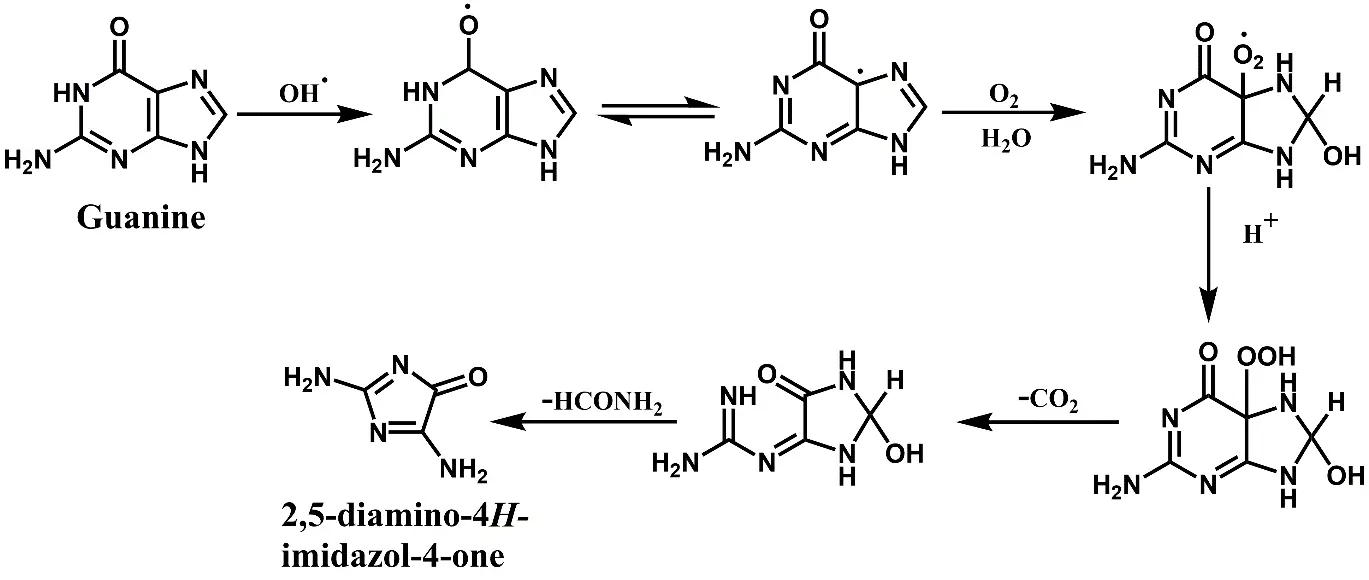

The OH· attacks the carbonyl group of guanine, forming a radical (Figure 6). The radical underwent a rearrangement and subsequently reacted with molecular oxygen and water to generate the peroxy radical. This radical was converted to a hydroperoxide in the presence of acidic impurities. Subsequently, there was an opening of the pyrimidine ring at the C5–C6 bond along with decarboxylation. This step was followed by the removal of a formamide molecule to give 2,5-diamino-4H-imidazol-4-one as the final product [32].

Figure 6. A plausible pathway for the product generation as a result of the CdS-induced photocatalytic reaction of guanine.

4. Conclusions

We have reported 2,5-diamino-4H-imidazol-4-one as the product of the CdS-induced photocatalytic reaction of guanine using LC-MS analysis. This product was observed when the pH of the solution was 11.5 or higher to allow the solubility of guanine. The photocatalytic reaction did not result in the product formation when the experiment was carried out under an inert atmosphere. The mechanistic studies revealed that the photogenerated holes participated in the photocatalytic reaction. The present study would be useful for investigating the effect of visible radiation on DNA damage.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be found at: https://www.sciepublish.com/article/pii/856, Figure S1: Electronic spectra of 1 mM guanine in the absence of the CdS nanoparticles at different illumination times as indicated in the inset; Figure S2: Electronic spectra of 1 mM guanine in the presence of CdS and 0.2 mM EDTA at various illumination times as displayed in the inset; Figure S3: Electronic spectra of 1 mM guanine in the presence of CdS and 1 mM AgNO3 at various illumination times as displayed in the inset.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Central Electrochemical Research Institute (CECRI), Karaikudi, India, for the TEM measurements. We would like to acknowledge the NIT, Meghalaya, India, for the XRD analysis. The Sophisticated Analytical Instrument Facility at the Mahatma Gandhi University, Kottayam, India, is acknowledged for the LC-MS measurements.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.R. and D.P.S.N.; Methodology, P.R.; Validation, P.R.; Formal Analysis, P.R.; Investigation, P.R.; Resources, D.P.S.N.; Data Curation, P.R.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, P.R.; Writing—Review & Editing, D.P.S.N.; Supervision, D.P.S.N.

Ethics Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is available upon request.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

-

Wang XX, Gu Y, Fang YF, Huang YP. Mechanism of oxidative damage to DNA by Fe-loaded MCM-41 irradiated with visible light. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2012, 57, 1504–1509. DOI:10.1007/s11434-012-5042-1 [Google Scholar]

-

Cadet J, Douki T, Ravanat J-L. Oxidatively generated damage to the guanine moiety of DNA: Mechanistic aspects and formation in cells. Acc. Chem. Res. 2008, 41, 1075–1083. DOI:10.1021/ar700245e [Google Scholar]

-

Bull GD, Thompson KC. The oxidation of guanine by photoionized 2-aminopurine. J. Photochem. Photobiol. 2021, 6, 100025. DOI:10.1016/j.jpap.2021.100025 [Google Scholar]

-

Steenken S, Jovanovic SV. How easily oxidizable is DNA? One-electron reduction potentials of adenosine and guanosine radicals in aqueous solution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997, 119, 617–618. DOI:10.1021/ja962255b [Google Scholar]

-

Duarte V, Gasparutto D, Jaquinod M, Cadet J. In vitro DNA synthesis opposite oxazolone and repair of this DNA damage using modified oligonucleotides. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000, 28, 1555–1563. DOI:10.1093/nar/28.7.1555 [Google Scholar]

-

Smirnova VS, Gudkov SV, Chernikov AV, Bruskov VI. The formation of 8-oxoguanine and its oxidative products in DNA in vitro at 37 degrees C. Biofizika 2005, 50, 243–252. [Google Scholar]

-

Kino K, Sugiyama H. Possible causes of G·C→C·G transversion mutation by guanine oxidation product, imidazolone. Chem. Biol. 2001, 8, 369–378. DOI:10.1016/S1074-5521(01)00019-9 [Google Scholar]

-

Gasparutto D, Ravanat J-L, Gerot O, Cadet J. Characterization and chemical stability of photooxidized oligonucleotides that contain 2,2-diamino-4-[(2-deoxy-β-D-erythro-pentofuranosyl) amino]-5(2H)-oxazolone. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998, 120, 10283–10286. DOI:10.1021/ja980674y [Google Scholar]

-

Kino K, Saito I, Sugiyama H. Product analysis of GG-specific photooxidation of DNA via electron transfer: 2-aminoimidazolone as a major guanine oxidation product. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998, 120, 7373–7374. DOI:10.1021/ja980763a [Google Scholar]

-

Kupan A, Saulière A, Broussy S, Seguy C, Pratviel G, Meunier B. Guanine oxidation by electron transfer: One-versus two-electron oxidation mechanism. ChemBioChem 2006, 7, 125–133. DOI:10.1002/cbic.200500284 [Google Scholar]

-

Jena NR, Mishra PC. Formation of ring-opened and rearranged products of guanine: Mechanisms and biological significance. Free Rad. Biol. Med. 2021, 53, 81–94. DOI:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.04.008 [Google Scholar]

-

Ravanat JL, Cadet J. Reaction of singlet oxygen with 2′-deoxyguanosine and DNA. Isolation and characterization of the main oxidation products. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 1995, 8, 379–388. DOI:10.1021/tx00045a009 [Google Scholar]

-

Niles JC, Wishnok JS, Tannenbaum SR. Spiroiminodihydantoin is the major product of the 8-oxo-7,8-dihydroguanosine reaction with peroxynitrite in the presence of thiols and guanosine photooxidation by methylene blue. Org. Lett. 2001, 3, 963–966. DOI:10.1021/ol006993n [Google Scholar]

-

Fleming AM, Burrows CJ. Chemistry of ROS-mediated oxidation to the guanine base in DNA and its biological consequences. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 2021, 98, 452–460. DOI:10.1080/09553002.2021.2003464 [Google Scholar]

-

Jomova K, Alomar SY, Alwasel SH, Nepovimoba E, Kuca K, Valko M. Several lines of antioxidant defense against oxidative stress: Antioxidant enzymes, nanomaterials with multiple enzyme-mimicking activities, and low-molecular-weight antioxidants. Arch. Toxicol. 2024, 98, 1323–1367. DOI:10.1007/s00204-024-03696-4 [Google Scholar]

-

Jabbar ZH, Ebrahim SE. Recent advances in nano-semiconductors photocatalysis for degrading organic contaminants and microbial disinfection in wastewater: A comprehensive review. Environ. Nanotechnol. Monit. Manag. 2022, 17, 100666. DOI:10.1016/j.enmm.2022.100666 [Google Scholar]

-

Cui S, Wang X, Lin Z, Ding M, Yang X. Cation exchange synthesis of hollow-structure cadmium sulfide for efficient visible-light driven photocatalytic hydrogen evolution. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 26757–26767. DOI:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2023.03.379 [Google Scholar]

-

Li B, Xiao Y, Qi Z, Chang S, Yu M, Xu Z, et al. Enhanced photocatalytic H2 production of CdS by the introduction of Cd vacancies. Chem. Commun. 2025, 61, 15630–15633. DOI:10.1039/D5CC03311J [Google Scholar]

-

Qi Z, Chen J, Li Q, Wang N, Carabineiro SAC, Lv K. Increasing the photocatalytic hydrogen generation activity of CdS nanorods by introducing interfacial and polarization electric fields. Small 2023, 19, 2305518. DOI:10.1002/smll.202303318 [Google Scholar]

-

Warjri W, Saha D, Diamai S, Negi DPS. Catechol oxidase mimetic activity of cadmium sulfide nanoparticles for the oxidation of L-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine. Mater. Res. Express 2019, 6, 035020. DOI:10.1088/2053-1591/aaf523 [Google Scholar]

-

Dhananjeyan MR, Annapoorani R, Lakshmi S, Renganathan R. An investigation on TiO2-assisted photo-oxidation of thymine. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 1996, 96, 187–191. DOI:10.1016/1010-6030(95)04297-0 [Google Scholar]

-

Kumar A, Negi DPS. Photophysics and photocatalytic properties of Cd(OH)2-coated Q-CdS clusters in the presence of guanine and related compounds. J. Colloid Inter. Sci. 2001, 238, 310–317. DOI:10.1006/jcis.2001.7483 [Google Scholar]

-

Hou H, Wang X, Chen C, Johnson DM, Fang Y, Huang Y. Mechanism of photocatalytic oxidation of guanine by BiOBr under UV irradiation. Catal. Commun. 2014, 48, 65–68. DOI:10.1016/j.catcom.2014.01.023 [Google Scholar]

-

Spanhel L, Haase M, Weller H, Henglein A. Photochemistry of colloidal semiconductors. 20. Surface modification and stability of strong luminescing CdS particles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1987, 109, 5649–5655. DOI:10.1021/ja00253a015 [Google Scholar]

-

Saha D, Negi DPS. Particle size enlargement and 6-fold fluorescence enhancement of colloidal CdS quantum dots induced by selenious acid. Spectrochim. Acta A 2020, 225, 117486. DOI:10.1016/j.saa.2019.117486 [Google Scholar]

-

Pandian SRK, Deepak V, Kalishwaralal K, Gurunathan S. Biologically synthesized fluorescent CdS NPs encapsulated by PHB. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 2011, 48, 319–325. DOI:10.1016/j.enzmictec.2011.01.005 [Google Scholar]

-

Oliveira JFA, Milão TM, Araújo VD, Moreira ML, Longo E, Bernardi MIB. Influence of different solvents on the structural, optical and morphological properties of CdS nanoparticles. J. Alloys Compd. 2011, 509, 6880–6883. DOI:10.1016/j.jallcom.2011.03.171 [Google Scholar]

-

Razskazovskiy Y, Campbell EB, Cutright ZD, Thomas CS, Roginskaya M. One-electron oxidation of guanine derivatives: Detection of 2,5-diaminoimidazolone and novel guanine-guanine cross-links as major end products. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 2022, 196, 110099. DOI:10.1016/j.radphyschem.2022.110099 [Google Scholar]

-

Morikawa M, Kino K, Oyoshi T, Suzuki M, Kobayashi T, Miyazawa H. Analysis of guanine oxidation products in double-stranded DNA and proposed guanine oxidation pathways in single-stranded, double-stranded or quadruplex DNA. Biomolecules 2014, 4, 140–159. DOI:10.3390/biom4010140 [Google Scholar]

-

Park B, Park W-W, Choi JY, Choi W, Sung YM, Sul S, et al. Pt cocatalyst morphology on semiconductor nanorod photocatalysts enhances charge trapping and water reduction. Chem. Sci. 2023, 14, 7553–7558. DOI:10.1039/D3SC01429K [Google Scholar]

-

Taki MM, Mahdi RI, Al-Keisy A, Alsultan M, Al-Bahnam NJ, Majid WHA, et al. Solar-light-driven Ag9(SiO4)2NO3 for efficient photocatalytic bactericidal performance. J. Compos. Sci. 2022, 6, 108. DOI:10.3390/jcs6040108 [Google Scholar]

-

Cadet J, Berger M, Buchko GW, Joshi PC, Raoul S, Ravanat J-L. 2,2-diamino-4-[(3,5-di-O-acetyl-2-deoxy-β-D-erythro-pentofuranosyl)amino]-5-(2H)-oxazolone: A novel and predominant radical oxidation product of 3′,5′-di-O-acetyl-2′-deoxyguanosine. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994, 116, 7403–7404. DOI:10.1021/ja00095a052 [Google Scholar]