3D-Printed Continuous Fiber Composites: An Overview of Materials, Systems and Processes

Received: 10 October 2025 Revised: 05 November 2025 Accepted: 24 November 2025 Published: 16 December 2025

© 2025 The authors. This is an open access article under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

1. Introduction

3D printing is transforming the manufacturing of structural composite materials, enabling the creation of complex and customized components with improved efficiency and performance. One of the most promising advancements in this field is the use of commingled technology, which combines thermoplastic matrices and continuous reinforcement fibers within a single tow [1]. When processed through additive manufacturing (AM) techniques, these composites offer several advantages, including enhanced design flexibility, reduced material waste, and the ability to tailor performance characteristics, making them well-suited for a broad range of industrial applications.

This paper examines the technological foundations of the materials, systems, and processes involved in producing 3D-printed thermoplastic composites reinforced with continuous fibers [1,2,3,4]. It highlights recent developments in material formulations, printing technologies, and process optimization, aiming to provide a comprehensive overview of the current state of the art and future directions in this innovative manufacturing approach. Special attention is given to the structural performance of these composites and the role of AM technologies in optimizing production workflows and enabling next-generation composite structures.

The main objective of this work is to investigate the technological foundations of materials, systems, and processes used in the production of 3D-printed thermoplastic composites reinforced with continuous fibers, with a focus on their potential applications in structural components. The paper highlights the performance characteristics of these composites and emphasizes the advantages of additive manufacturing technologies within the production chain.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Thermoplastic Composite Materials

Polymer matrix composites are typically classified by the type of polymer used: thermoplastic or thermosetting. Thermoplastic polymers are characterized by their ability to soften and melt upon heating and solidify upon cooling, a process that is entirely physical and reversible [5]. This behavior allows thermoplastics to be reshaped and reprocessed multiple times without significant degradation in their chemical structure, making them especially suitable for recycling and thermoforming applications.

Thermoplastics are generally amorphous or semi-crystalline in structure. In amorphous thermoplastics, the polymer chains are arranged in a highly disordered fashion, resulting in high entropy and low structural organization [6]. Even in semi-crystalline thermoplastics, the material consists of both ordered (crystalline) and disordered (amorphous) regions, with the amorphous phase dominating the overall behavior. This molecular arrangement influences key material properties, including the glass transition temperature, mechanical strength, and chemical resistance. Due to these characteristics, thermoplastic-based composites are gaining increasing interest in advanced manufacturing applications, including 3D printing, where rapid heating and cooling cycles and re-processability are critical advantages.

The amorphous structure of a thermoplastic polymer consists of a disordered arrangement of long, entangled molecular chains. This disordered configuration allows the chains to slide past one another when mechanical stress is applied, giving the material its characteristic high elongation and flexibility [7]. As the degree of molecular order increases through the formation of crystalline regions, the polymer transitions into a semi-crystalline state. In this structure, the crystalline domains act as reinforcing regions, enhancing the material’s thermomechanical properties, such as stiffness, strength, and thermal resistance.

The overall versatility of thermoplastic composites stems from the interplay between these two phases: the amorphous regions, which provide toughness and ductility, and the crystalline regions, which contribute to mechanical stability and thermal performance [8]. This balance enables fine-tuning of material properties to meet specific application requirements, particularly in advanced manufacturing processes such as additive manufacturing, where both flexibility during deposition and structural performance in the final product are critical.

The use of a thermoplastic polymer matrix combined with reinforcing fibers defines a thermoplastic composite material. The approaches and methods used to fabricate these composites pose challenges for both research and development, as well as the industrial sector. These challenges arise due to factors such as high processing temperatures, the high viscosity of the molten matrix, difficulty in fiber impregnation due to poor wettability, and, in many cases, weak adhesion at the fiber/matrix interface [9]. Therefore, these challenges are considered a common complication during the processing of thermoplastic composites.

Additionally, the processing difficulties include the complex control of the polymer’s thermal and dimensional stability, which can vary depending on the size and shape of the component being manufactured. Therefore, the appropriate processing method must take into account the characteristics and properties of the raw materials, along with a detailed analysis of the specific thermoplastic composite component to be produced [10].

Thermoplastic composite systems may face challenges with inadequate adhesion to reinforcing fibers, leading to issues with permeability, particularly the difficulty of molten material penetrating the fibers. This is partly due to the fact that molten thermoplastic resins have significantly higher viscosity compared to thermosetting resins, making it harder for the material to flow and properly wet the reinforcing fibers [11]. Therefore, these resins need to be processed at higher temperatures to lower their viscosity, while ensuring that the thermal degradation limits of the polymer are not exceeded [12]. Problems associated with the high viscosity of the polymer melt during pressure consolidation include misalignment of the reinforcing fibers and the formation of voids within the laminate. These issues can negatively impact the overall mechanical performance and structural integrity of the composite material [13].

Permeability refers to a material’s ability to allow the passage of a viscous fluid through its structure. This property is particularly critical in the processing of thermoplastic composites, where the molten polymer must effectively flow through the reinforcing fibers to achieve complete impregnation and proper consolidation of the composite. Luo et al. (2001) [14] define permeability as a measure of the resistance to resin flow through a fiber preform. As such, both permeability and porosity are inherent properties of the reinforcement architecture, whether it be fabric or tow.

The arrangement of the fibers plays a key role in determining permeability. Important influencing factors include the spacing between weft and warp yarns, the distance between individual filaments, and the intrinsic porosity of the fibers themselves. These characteristics collectively determine how easily a viscous matrix material can penetrate the reinforcement, directly impacting both the processing efficiency and final performance of the composite [15,16].

In addition, permeability and impregnation time are influenced by the fiber volume fraction and the direction of resin flow. Since fiber preforms are typically anisotropic, they exhibit direction-dependent permeability, meaning that resin may flow more readily in one direction than another depending on fiber orientation. This anisotropy must be carefully considered during processing to ensure uniform impregnation and to achieve the desired mechanical and structural properties in the final part. Effective control of flow direction and fiber alignment is essential for ensuring homogeneous matrix distribution and maximizing the composite’s overall performance [17].

The characterization and quantification of permeability in reinforcing fibers have become a major focus of recent research efforts. Accordingly, this study also aims to deepen understanding of matrix flow behavior through various fiber architectures, being an essential step toward optimizing manufacturing processes and improving the quality and functionality of thermoplastic composite materials.

The permeability coefficient, denoted as K and often referred to as the proportionality factor, quantifies how easily a fluid can flow through a fibrous reinforcement. A higher permeability coefficient indicates lower resistance to flow, allowing the resin to infiltrate the reinforcement more efficiently. This promotes better impregnation and a more uniform distribution of the matrix material within the fiber architecture, which is essential for achieving optimal composite performance [18].

A collaborative study involving research institutions and industry partners [19,20] conducted a significant reference work on permeability by comparing in-plane permeability data for two types of carbon fiber reinforcements. The results showed that the permeability coefficient (K) varied depending on the analysis method used, underscoring the strong influence of testing techniques on permeability measurements. This variation highlights that the choice of evaluation method can significantly affect the interpretation of permeability values in reinforcing fibers, emphasizing the need for standardized testing procedures to ensure consistent and reliable data.

Amico et al. (2001) [21] investigated the relationship between permeability and capillary pressure during resin infiltration in fabric assemblies used as reinforcements in composite materials. Their study demonstrated that pre-wetted fabrics exhibited higher permeability compared to dry fabrics, indicating a direct correlation between the reinforcement’s permeability and its capillarity (wettability). This finding highlights the significant influence of fiber surface conditions on the ease of fluid infiltration, underscoring the importance of wettability in optimizing composite manufacturing processes.

The recent use of thermoplastic matrices in long-fiber composites has significantly enhanced several crucial final characteristics of these materials. The primary benefits include improved toughness, greater damage tolerance, and enhanced durability of the composite components. These improvements make thermoplastic composites more effective and reliable for a variety of high-performance applications. The possibility of reprocessing, recycling, and a significant reduction in processing time, when compared to techniques used in composites with a thermoset matrix, are also key advantages of thermoplastic composites. These benefits not only contribute to cost efficiency but also align with growing environmental concerns by promoting sustainability and reducing waste in manufacturing processes [22].

Other advantages of thermoplastic composites include eliminating styrene emissions, leading to cleaner, healthier working and manufacturing environments. Additionally, thermoplastic composites exhibit significantly higher corrosion resistance compared to thermoset composites. Recent developments in high-performance thermoplastic polymers and composites have further expanded their potential for demanding applications, providing enhanced properties such as increased strength, durability, and versatility in harsh environments [23].

2.2. Additive Manufacturing Technologies

The benefits of thermoplastic composites are a strong attraction for several industrial sectors due to their versatility. However, thermoplastic matrices present technological and scientific challenges, particularly related to the high processing temperatures and pressures required for manufacturing. These challenges can complicate the production process, requiring precise control to achieve optimal material properties and ensure efficient processing [24]. Even in the molten state, thermoplastic matrices have a significantly higher viscosity than thermosetting matrices, making the impregnation of reinforcing fibers and the consolidation of these composites more difficult and complex. As a result, the successful application of thermoplastic matrix composites remains highly reliant on the development of new transformation processes, the adaptation of existing equipment, and adjustments to production parameters to meet the specific requirements of their processing. Additionally, a complication associated with thermoplastics is their high molecular weight, which leads to a high glass transition temperature (Tg) and, consequently, high melting temperatures. This necessitates higher processing temperatures compared to thermosetting composites, further complicating their manufacturing.

Increasing the processing temperature to reduce the viscosity of the melt is a practical way to improve the quality of the impregnation. However, this increase in temperature can cause thermal degradation of the polymer matrix. Another possible solution to increase the wettability of the reinforcement fibers by the polymer resin is through dissolution of the polymer. If the polymer resin is diluted to reduce its viscosity and facilitate impregnation of the fibers, it would cause another problem, which is the subsequent removal of the solvent. This would bring an additional cost to the process and problems associated with the removal method. In addition, thermoplastic composites are not soluble in any solvent, and, probably, the use of solvents would also cause changes in the properties of the reinforcement fibers [25].

On the basis of the previous considerations, it is evident that the approaches and methods used to manufacture these composites pose significant challenges for both research and development and the industrial sectors. These challenges include the need for high processing temperatures, the high viscosity of the matrix in its molten state, difficulties in impregnating the fibers due to poor wettability, and, in many cases, insufficient adhesion at the fiber/matrix interface. Addressing these issues is crucial for optimizing the performance and manufacturing efficiency of thermoplastic composites [9].

The difficulty in processing these materials also includes the challenge of controlling the thermal and dimensional stability of the polymer, which can vary depending on the size and shape of the component being produced. Therefore, the appropriate processing method must consider both the characteristics and properties of the raw material and a thorough understanding of the thermoplastic composite component to be manufactured. This ensures optimal processing conditions and the desired quality of the final product [10]. Consequently, AM techniques also presents the same challenges related to the processing of thermoplastics. The success of additive manufacturing with commingled thermoplastics depends on controlling processing conditions, material properties, and the ability to achieve efficient fiber impregnation and adhesion.

Several aviation companies, major material suppliers, and government agencies have invested in the research and development of 3D-printed composite materials. This collaborative effort was driven by the potential benefits of thermoplastic composites, such as versatility, reduced weight and waste, improved processing efficiency, and enhanced performance for structural components, making them highly attractive, especially for the aerospace and automotive industries [26].

Recent developments in the synthesis of new polymers not only address issues related to processing and applicability, but also sustainability [27]. As an example, Luo et al. (2024) [28] summarized recent advances in the design, synthesis, and properties of recyclable bio-based polymers for 3D-printing. However, issues such as porosity, poor fiber/matrix adhesion, and high viscosity remain and need to be addressed in the design of new technologies for 3D-printing composites. analyzing the involved parameters that most influence the process and material performance.

Currently, with significant technological advances, thermoplastic polymers account for 80% of the entire commodity-type materials market. But thermoplastic composites still represent only 20% of the materials used in the current composites market. This disparity highlights the increasing use of thermoplastic polymers in various applications, while thermoplastic composites continue to face challenges in processing [29]. Challenges in the production of thermoplastic composites continue to drive research into new materials, processes, technologies, and products. Scientific and technological studies on commingled materials aim to overcome existing barriers, such as high viscosity, poor fiber impregnation, and complex processing requirements, with the goal of improving the performance, efficiency, and scalability of thermoplastic composites for a wider range of applications [30], particularly in 3D-printing.

The consolidation of a thermoplastic composite material is defined as the process of compacting the layers of the prepreg to unify the material, ultimately achieving a defined final shape. This process involves the application of heat and pressure to ensure proper impregnation of the fibers with the matrix, resulting in a strong, cohesive composite structure with the desired mechanical properties [31]. During the flattening process, volatiles are removed from the laminate, though voids may form due to trapped air, moisture, or solvents. The impregnation process involves the molten polymer being pressed through the reinforcing material in four key steps: percolation of the polymer through the reinforcement, flow of the molten polymer along the reinforcement plane, interlaminar shearing along the fiber direction, and interlaminar sliding of layers in different orientations [32,33].

The hot compression molding (HCM) process has garnered significant attention from the aerospace and automotive industries for the production of thermoplastic composites. This manufacturing method is designed for large-scale production, meeting the specific quality requirements of each sector while significantly reducing processing time. The advantages of the HCM process include precise positioning and orientation of the reinforcement fibers, control over the fiber/matrix volumetric content, and the ability to produce parts with a range of geometries, although typically not overly complex ones [32,34].

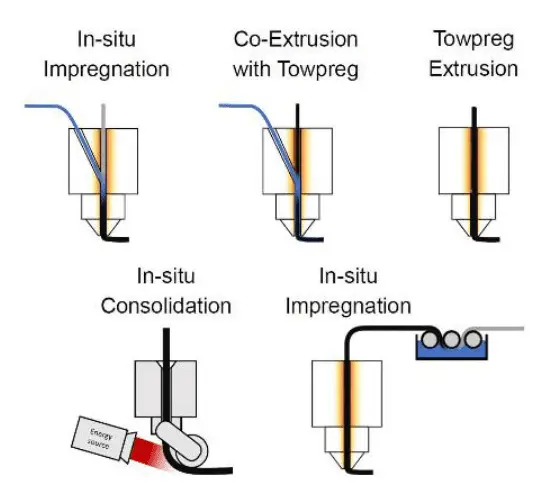

Additive Manufacturing with Continuous Fibers (AM-CFRP) produces high-performance products with complex 3D geometries. Vaneker et al. (2023) [35] evaluated the effects of feedstock, nozzle design, and print settings on 3D-printed commingled composites. The authors first identified the types of AM-CFRP processing, as illustrated in Figure 1. They concluded that current nozzle designs for thermoplastic composites have shape limitations and do not meet all the requirements for manufacturing high-permanence structural materials due to the high void content and low delamination resistance in the printed product. Also, AM technologies present significant challenges related to residual stresses and warping, which result from the repeated deposition of heated material onto cooler layers [36,37].

Figure 2 represents a basic nozzle design in which A is the nozzle diameter, B is the inflow channel diameter, C is the heated channel length, and D is the nozzle edge width. The study suggests that new concepts for nozzle design, including shaping, heating, and filament deposition, should be developed.

Compton et al. (2017) [36] observed that polymer thermal expansion in AM processes results in significant deformation and product warping. The authors measured the thermal expansion of composite parts during the 3D-printing process using infrared imaging and thermal modeling to predict temperature profiles and deposition parameters. The study aimed to minimize the likelihood of cracking during printing. By considering the Tg as a pass/fail threshold for processing, they found that increasing the build chamber temperature had the greatest impact on the dimensions of the 3D-printed parts. Additionally, for the range of material properties and deposition parameters examined, increasing the thermal conductivity of the feedstock material contributed to warping.

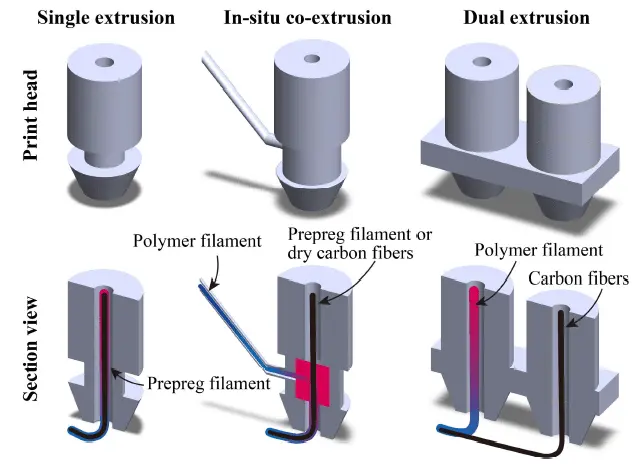

The study conducted by Cai and Chen (2024) [38] compared different print head types for Continuous Fiber Reinforced Thermoplastic Composites (CFRTPC) 3D-printing. The authors classified the fused filament fabrication (FFF) extrusion methods into three types. First, the single extrusion method produces CFRTPC with simplicity, versatility, high quality, and a good degree of impregnation. However, the limitations of this method include a low fiber volume fraction and low processing efficiency. In situ co-extrusion increases the fiber volume fraction and enhances the material’s flexibility. However, this method requires a complex internal configuration of the print head and typically results in CFRTPC with a lower degree of impregnation. Finally, dual extrusion offers high processing efficiency, but it still does not match the quality of the other methods. Different print heads are revealed in Figure 3.

Fused Deposition Modelling (FDM) is the most widely used AM technology due to its affordability and ease of use. This method involves melting and extruding polymeric material layer by layer to create objects, making it a possibility for both prototyping and production. Like other 3D-printing techniques, FDM allows for the creation of complex designs without the need for molds or cutting tools [39]. However, the mechanical performance of plastic parts produced by FDM is a major concern, particularly regarding their load-bearing capacity for fully functional applications, especially when using thermoplastic materials [40].

3D-printing is a groundbreaking technology based on FDM that constructs objects layer by layer, turning digital designs into physical items. Its key advantage is the ability to produce intricate shapes without requiring molds or cutting tools, setting it apart from traditional subtractive manufacturing methods [41]. He et al. (2020) [42] demonstrated that the production of continuous carbon fiber composites using the FDM method addresses the issue of low mechanical performance in raw or short-fiber reinforced polymer parts fabricated by the same process, thanks to the excellent specific strength and stiffness of continuous fibers. A key issue with 3D-printed polymers or fiber-reinforced polymers is the formation of microscopic voids between individual filaments and within the filaments during the FDM process. The authors identified and quantified the effects of voids on 3D-printed continuous fiber-reinforced carbon fiber/polyamide 6 (CF/PA6), demonstrating that the presence of voids directly and significantly impacts the structural integrity of the final product. Figure 4 presents a typical 3D-printer and the printer head used for thermoplastic polymers processing.

The experimental study conducted by Liao et al. (2023) [43] compared the volume fraction of 3D-printed materials under unidirectional (0°) and bidirectional (45°/−45° and 0°/90°) deposition conditions. The results showed that the void volume in the 0° direction (with connected voids being dominant) was significantly higher compared to those printed in the 45°/−45° and 0°/90° directions. This poses a challenge to the structural performance of 3D-printed materials, as voids can affect various aspects of the laminate, including its mechanical, thermal, and long-term durability properties.

Figure 4. Large scale 3D-printer developed at Federal University of Itajubá used for continuous fiber deposition.

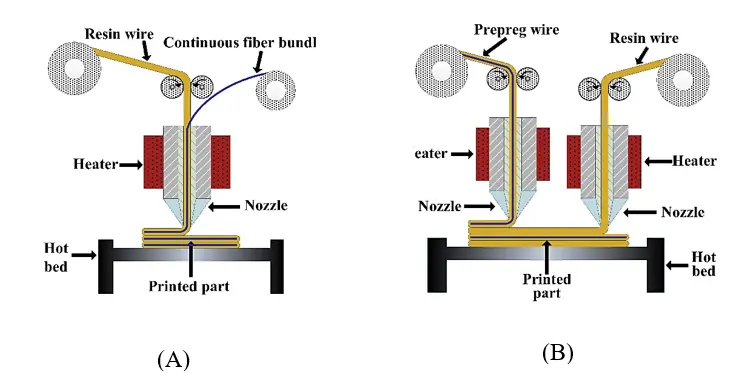

CFRTPCs (carbon fiber-reinforced thermoplastic composites) fabricated using FDM combine the strength and stiffness of reinforced fibers—typically carbon, glass, aramid, and natural fibers, with the flexibility and ease of processing of thermoplastic polymers [44]. According to Yang et al. (2023) [45], the principles of FDM processing for CFRTPCs are classified into two categories: online infiltration co-extrusion and offline prepreg double-nozzle extrusion.

Online infiltration co-extrusion refers to a process in which continuous fibers are impregnated with a thermoplastic matrix during 3D-printing. In contrast, offline prepreg double-nozzle extrusion involves a two-stage process where pre-impregnated fibers (prepregs) are combined with a thermoplastic matrix. This technique uses two nozzles to simultaneously extrude both the prepreg fibers and the molten thermoplastic matrix during 3D-printing, with fiber impregnation occurring separately before extrusion. Figure 5 illustrates the online infiltration co-extrusion and (B) offline prepreg double nozzles.

An offline prepreg double-nozzle extrusion process was used by Iragi et al. (2019) [46] to produce a 3D-printed composite with continuous carbon fiber/PA (CCF/PA) filament coextruded with PA6 yarn. The intra- and interlaminar behaviors of the printed laminates were characterized to determine the material’s elastic and strength properties. The authors identified defects in the printed material, including inhomogeneous fiber distribution, a high number of intra- and interlaminar voids, and weak interlayer bonding. These defects were likely caused by insufficient thermal consolidation parameters, resulting from the fast cooling rate below the glass transition temperature (Tg).

A melt impregnation line based on FDM was created by Uşun and Gümrük (2019) [47] to extrude polylactic acid (PLA) with carbon fibers to test the effects of different fiber fractions on the mechanical properties of CFRTP filaments. The processing line consists of fiber spreading, polymer mixing, and molding zones. The results indicated that the filaments exhibited excellent mechanical strength, particularly in tensile strength. Proper adjustment of the filament’s fiber volume results in a material with enhanced performance, provided that good wettability and consolidation are maintained. However, the authors highlighted the inhomogeneous distribution of fibers during processing, noting that as the fiber fraction decreased, the fibers concentrated in the center of the filament.

PEEK powder was extruded using a single-screw extruder to produce filaments for 3D-printing without fiber reinforcement, as reported by Rinaldi et al. (2018) [48]. The infill layer refers to the internal structure of a 3D-printed object, and the study demonstrated significant differences in mechanical performance depending on the printing direction. These differences were attributed to the pattern or mesh used to fill the space between the object’s outer boundary. The results also showed no significant differences in thermal properties, such as the glass transition temperature (Tg) and melting point (Tm), between PEEK filaments and 3D-printed PEEK.

The study conducted by Luo et al. (2019) [49] explored the preparation of Continuous Carbon Fiber Reinforced Polyether Ether Ketone (CCF/PEEK) composites using 3D-printing. According to the study, incorporating continuous fibers into the 3D-printing process leads to interlayer delamination due to weak bonding and high porosity. However, the study suggested that modifying the viscosity of the matrix material and applying pre-impregnation techniques, such as laser in-situ preheating, enhanced impregnation between the carbon fiber tow and PEEK. The diagram presented in

The study conducted by Pagliarulo et al. (2022) [50] combined full-field, non-contact optical techniques, such as 2D Digital Image Correlation (2D-DIC) and Electronic Speckle Pattern Interferometry (ESPI), with scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and optical microscopy, for micro and macroscale analysis of 3D-printed CF/PEEK composites. The results demonstrated how a multimodal approach can comprehensively characterize manufactured by the FDM technique. The findings from the multimodal analysis revealed areas with low fiber fill, likely caused by rapid narrowing or insufficient filament overlap. This may lead to embrittlement, even though the fiber orientation aligns with the nozzle flow direction.

Caminero et al. (2018) [51] studied the interlaminar bonding performance of PA reinforced with glass, carbon, and Kevlar® fibers for 3D-printed CFRTPC using FDM technology. The authors concluded that interlaminar bonding decreases with increasing laminate thickness, due to the effect of porosity. Additionally, the study found that carbon fiber composites exhibit superior mechanical properties to glass and Kevlar® fibers, as they enhance wettability and impregnation capability.

Liu et al. (2020) [52] developed a micro-screw in-situ extrusion process for CFRTPC 3D-printing, using pellets of polyamide 12 (PA12) as the matrix. According to the authors, the 3D-printing process integrates both the composite preparation (mixing fibers with the resin) and the formation (printing the composite part), resulting in enhanced impregnation, a high fiber volume fraction, and improved mechanical performance, thus demonstrating great potential for broad industrial applications.

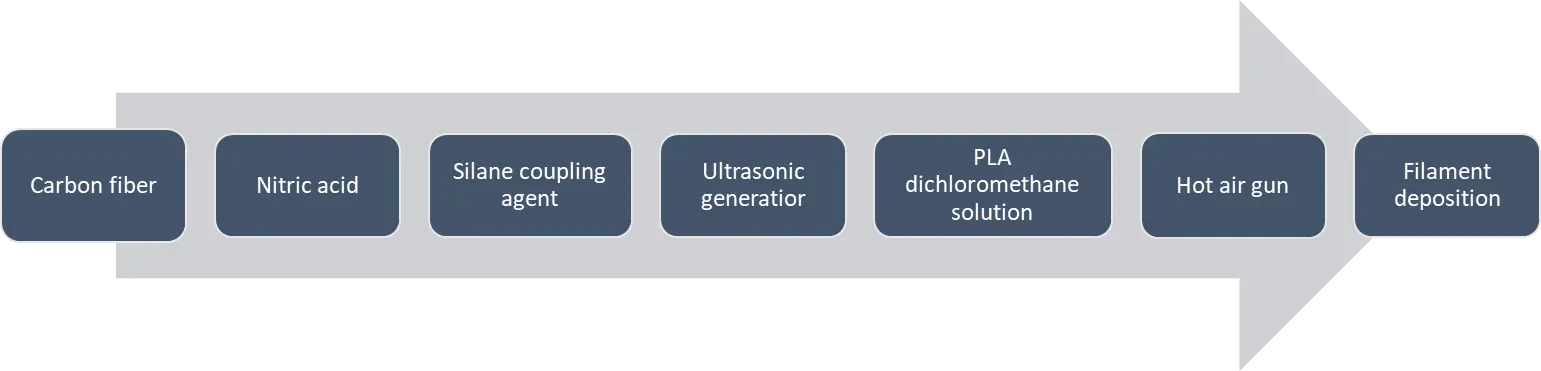

Zhang et al. (2021) [53] reported new advancements in FDM with a coaxial extrusion process for CFRTPC, to address manufacturing defects caused by poor resin wettability on fiber bundles and to improve the quality of traditional 3D-printed materials. Their approach involved a pre-process that included fiber surface modification (using acetone solution, nitric acid, and a silane coupling agent) and ultrasonic treatment applied to the PLA resin solution and fibers to enhance the impregnation during thermal consolidation. The preprocessing improved the mechanical strength of CFRTPC by enhancing resin wettability on the fiber bundles. Additionally, the authors emphasized the reduction of manufacturing defects caused by poor and unstable fiber-resin bonding, a common issue with the single extrusion method. The additive manufacturing process is detailed in Figure 6.

The study by Pandelidi et al. (2022) [54] focused on producing CFRTPC through a coaxial extrusion process. They modified a 3D printer by upgrading the heated platform, motion platform, and carriages to withstand the high temperatures required for consolidation. The results revealed insufficient fiber/matrix adhesion and fiber breakage during FFF processing, negatively impacting the load-transfer capability and overall composite properties.

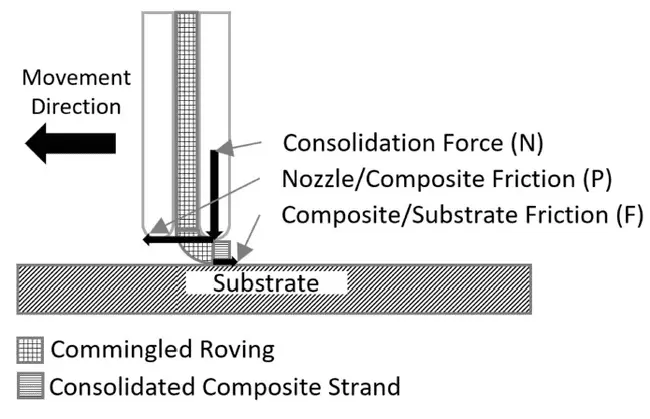

Automated Fiber Placement (AFP) for in-situ consolidation of continuous carbon fiber (CF) and high-performance thermoplastic composites utilizes continuous fiber-reinforced thermoplastic prepregs [37]. The operating principle of AFP resembles the type of processing required for commingled tows in 3D printing. The process involves an automated placement equipment that positions, lays up, and consolidates the fibers according to a mathematical model (Figure 7). Components are built up layer by layer in the thickness direction until the desired thickness is reached, eliminating the need for traditional processes like autoclave curing after lay-up. This technology is poised to revolutionize the manufacturing of composite components, particularly in aerospace applications, by streamlining production and enhancing material performance [30].

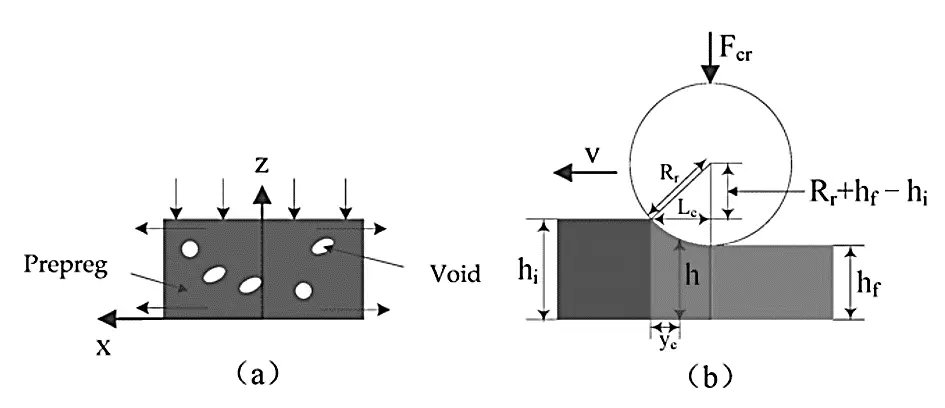

During the in-situ consolidation process, the prepreg and substrate are melted and compressed by the compaction roller. The material is then cooled and solidified, bonding the layers together. Before pressure is applied, the thermoplastic matrix of the prepreg undergoes softening, thermal expansion, and melting during a brief heating period. Simultaneously, dissolved volatiles and trapped air are released, and voids begin to form within the laminate. The pressure from the compaction roller eliminates interlaminar and intralaminar voids; however, residual pores can often form within the material, leading to porosity (Figure 8) [30].

The contact length $${L}_{c}$$ between the compaction roller and prepreg can be described as:

|

```latex{L}_{c} = {\sqrt{\left[{R}_{r}^{2} - {\left({R}_{c} - {h}_{i} + {h}_{f}\right)}^{2}\right]}}^{}``` |

(1) |

similarly, the height ℎ of the layer may be expressed as:

|

```latexh = {R}_{r} + {h}_{f} - {\sqrt{\left[{R}_{r}^{2} - {\left({L}_{c} - {y}_{c}\right)}^{2}\right]}}^{}``` |

(2) |

where, yc represents the distance between the contact point of the prepreg and the front of the compaction roller (the position where the thickness of the layer is ℎ), initial thickness of the layers is ℎi, the width is $${w}_{i}$$, $$x$$ is the width direction, $$y$$ is the direction of movement, $$z$$ is the thickness direction, and the placement speed is $$v$$. As the compaction roller passes through the bonding area, the thickness of the layer is reduced to $${h}_{f}$$ and the width changes to $${w}_{f}$$.

In the in situ consolidation process, voids are usually inter-laminar and intra-laminar. The intra-laminar voids mainly contribute to the following aspects: (1) softening of the resin matrix, (2) primary voids in the prepreg, and (3) dissolved air. The inter-laminar voids are mainly caused by the fact that the intimate contact between layers has not reached one [55]; hence, there exists residual air between the layers.

To mitigate issues in 3D printing, such as final porosity, compacted thermoplastic printing utilizes a heated roller that compacts the layers during printing, thus preventing voids. This process requires greater complexity in the printing head, which must move while keeping the compacting roller perpendicular to the printing orientation [56].

As mentioned before, commingled technology refers to fiber-reinforced materials in which continuous fibers are combined with a thermoplastic polymer matrix (in yarn form) into a single tow or filament that is easy to store, shape, and mold [57]. The processing of commingled tow depends on temperature and high pressure, which can be achieved through compression molding. When the proper temperature and pressure are applied, effective consolidation of the commingled tow results in a final composite material with strong fiber-matrix bonding, ensuring better fiber alignment and distribution [11]. The consolidation process of the thermoplastic commingled composite results in the pressure compaction of the material in the form of fabric, with the impregnation and wetting of the reinforcing fibers by the polymer matrix in the molten state, and consequently, the elimination of voids within the material [58].

The use of commingled tow in 3D-printed composites results in significant improvements in the material’s mechanical properties. Continuous fibers provide superior strength and stiffness, while the thermoplastic matrix offers flexibility and ease of processing. These composites exhibit enhanced strength-to-weight ratios, making them ideal for lightweight, high-performance applications.

Unlike traditional composite manufacturing techniques (such as filament winding or resin transfer molding), which involve multiple steps to combine fibers and matrix materials, 3D printing with commingled tow offers a more streamlined process that simplifies fabrication. Achieving optimal bonding between the fiber and the thermoplastic matrix is crucial to maximizing mechanical performance. Poor bonding can lead to delamination or premature failure of the printed part, so research continues to focus on improving this bond. Handling commingled tows during 3D printing requires careful management of the material’s flow properties to prevent clogging of the extrusion nozzle and ensure consistent deposition.

Commingled tow for 3D printing offers a powerful method for creating high-performance composite parts with customized mechanical properties. By combining continuous fibers with a thermoplastic matrix, this technology enables the production of lightweight, strong, and durable components for various industries, including aerospace, automotive, and sports equipment. While challenges persist in terms of fiber-matrix bonding and processing, the potential benefits of commingled tow in 3D printing are significant, particularly for custom and high-performance applications.

The versatility of commingled 3D-printed materials includes the ability to control fiber alignment during printing process. By adjusting the orientation of the commingled tow in each printed layer, the mechanical properties can be tailored to meet specific requirements, such as enhanced tensile strength or impact resistance. Additionally, this technology helps reduce waste, as the fiber and matrix are combined into a single filament, and the process is more precise compared to traditional methods of fiber lay-up or prepregging [59].

A 3D-printed CF/PA6 pultruded commingled was developed by Zhuo et al. (2022) [60]. A pultrusion process has been applied to a commingled tow to create a prepreg prior to subsequent printing. According to the authors, the commingled tow cannot be directly used in the 3D printing process due to insufficient impregnation. As a result, the CF/PA prepreg increased fiber volume and reduced void content. However, the authors suggest that further development in commingled 3D printing is needed to improve and optimize the material’s performance.

A large-format gantry-style 3D printer with a 5-axis extrusion system has been developed by Bourgeois et al. (2021) [61]. Initially, they recognized that for effective material consolidation, the extruder must remain perpendicular to the placement surface throughout the process. To address this issue, a five-axis system was employed to demonstrate the capability of material consolidation over complex contours. Additionally, this system allows adjustment of the deposition width by rotating the placement nozzle, as shown in Figure 9.

2.3. Multiscale Modelling

Multiscale modeling is defined by a simulation approach that relates the material behavior across different length and time scales. These simulations involve the microscale as fiber, matrix, and interface, to the macroscale referring to the entire printed structure. The studies allow accurate prediction of the mechanical performance of complex composite systems like 3D printed continuous fiber reinforced thermoplastic (CFTP) composites [62].

The study conducted by Fu and Dong (2024) [63] investigated the behavior of 3D-printed continuous fiber-reinforced thermoplastic composites (CFTP) under low-velocity impact conditions, identifying delamination and defect propagation as the main failure modes. To increase impact resistance, the authors proposed a new design for 3D-printed continuous fiber-reinforced thermoplastic orthogonal fabric composites (CFTPOF). They developed analytical models for both the molding process and the mechanical properties and introduced a coupled multiscale analysis method (3DP-MS method) to accurately predict the mechanical performance of the material. This multiscale modeling approach encompasses behaviors at the micro, meso, and macro-scales, including fiber-matrix interfaces, yarn debonding, and material damage, with its accuracy validated experimentally. Furthermore, it was found that configurations with multiple vertical yarn groups per warp-weft pair improve interlacing and mechanical strength, while denser filling of the warp yarns increases compaction and overall structural integrity of the 3D-printed composites.

Mechanical properties of 3D printed continuous fiber reinforced thermoplastic fabric composites (CFRTPFCs) were studied by Fu et al. (2022) [64]. Manufacturing processes parameters, and the mechanical properties of the composites were analyzed using the multiscale fluid-solid coupling method. The simulation approach was based on the resin infiltration, temperature change and resin curing of 3D printed CFRTPFCs. The main results include that space utilization and the strength of the composites will be improved by reducing the distance between two parallel tows, decreasing the total thickness of the fabric, and decreasing the aspect ratio of beads.

The mechanical behavior of 3D printed CFRTPCs was also investigated by Fu and Yao (2021) [65]. The authors simulated the melting–deposition–cooling process to evaluate CFRTPCs mechanical properties, according to resin infiltration, temperature variation, and curing cycles during printing. The study found that the stacking method and aspect ratio of beads have a significant impact on the space utilization of 3D printing. Also, damage in CFRTPCs initially occurs in regions between adjacent beads, and then by the crack propagation along the fiber direction, affecting the mechanical properties of CFRTPCs.

2.4. Future Directions

After a thorough analysis of the materials, systems, and processes of 3D printing of composites, it is highlighted that future developments of these technologies involve improving material performance, process accuracy, and scalability, the latter being the ability of a system, network, or process to grow and handle an ever-increasing volume of work without compromising performance or functionality.

Emerging research should emphasize multi-material and functionally graded printing, which enables the achievement of combined mechanical, thermal, and electrical properties in a single component. Also noteworthy is the integration of mixed filaments, in-situ consolidation, and real-time process monitoring through sensors and artificial intelligence-based control systems. The goal is to improve adhesion between layers and reduce void formation. Hybrid manufacturing, combining additive manufacturing techniques and automated fiber deposition, allows for the production of larger and high-strength structural parts.

Furthermore, the adoption of multiscale modeling can accelerate the feedback cycle between design, manufacturing, and performance, enabling predictive optimization of mechanical properties.

The future of 3D-printed composites converges on smart materials, adaptive manufacturing, and digital engineering for the creation of lightweight, durable, and environmentally responsible structures.

Finally, commingled filaments, in which the reinforcing fibers and the thermoplastic matrix are intimately combined in the same tow, offer significant potential for fast impregnation, higher adhesion between the fiber and the matrix, and fully recyclable thermoplastic composites. Future research will aim to improve process control during the manufacturing and deposition of the filaments, enabling precise temperature control, uniform consolidation, and minimization of void formation.

The integration of in-situ consolidation techniques, such as laser-assisted or induction heating, will improve interlayer adhesion and mechanical performance. Furthermore, multi-axis and robotic additive manufacturing systems will allow the deposition of commingled filament bundles with controlled orientation and high compaction levels. The combination of multiscale simulations and AI-based optimization techniques will enable real-time prediction and correction of process deviations. Ultimately, the evolution of 3D printing of composites with commingled filaments will lead to lightweight, high-strength, and customizable components for aerospace, automotive, and structural applications, bridging the gap between additive manufacturing and advanced composite engineering.

3. Conclusions

In conclusion, 3D-printed continuous fiber composites stand at the forefront of additive manufacturing, offering unprecedented opportunities to produce lightweight, high-strength components with enhanced mechanical properties. The integration of continuous fibers within the printing process addresses many limitations of conventional polymer-based 3D printing, pushing the boundaries of what can be achieved in terms of structural performance and design complexity. This review has highlighted critical advancements in fiber materials, deposition technologies, and novel commingled approaches that unify reinforcement and matrix at the filament level. Together, these developments not only deepen our understanding of continuous fiber-reinforced additive manufacturing but also pave the way for innovative applications across diverse industries. As research and technology continue to evolve, the potential for these composites to revolutionize manufacturing and enable tailored, high-performance products is both promising and substantial.

Statement of the Use of Generative AI and AI-Assisted Technologies in the Writing Process

ChatGPT was used only for language refinement and not for content generation.

Aknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the Composite Technology Center (NTC) from the Federal University de Itajubá-Brazil for the general facilities.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: R.M.D.B. and A.C.A.J. Methodology: I.C. and F.N. Investigation: L.C.P. and A.J. Resources: R.M.D.B. and A.C.A.J. Writing—Original Draft Preparation: R.M.D.B. and I.C. Writing—Review & Editing: L.C.P., A.J., I.C. and F.N. Visualization: T.d.F.S. and A.J. Supervision: A.C.A.J. Project Administration: R.M.D.B. Funding Acquisition: R.M.D.B. and A.C.A.J.

Ethics Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new datasets were generated or analyzed for this study.

Funding

This research was funded by National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) under project 407431/2022-5, 447331/2024-8 and 303160/2023-3; from Research Foundation of the State of Minas Gerais (FAPEMIG) under project APQ 01846-18 and APQ-00853-25.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Di Benedetto RM, Janotti AJ, Gomes GF, Ancelotti Junior AC, Botelho EC. Statistical approach to optimize crashworthiness of thermoplastic commingled composites. Mater. Today Commun. 2022, 31, 2352–4928. doi:10.1016/j.mtcomm.2022.103651. [Google Scholar]

- Di Benedetto RM, Botelho EC, Janotti A, Ancelotti Junior AC, Gomes GF. Development of an artificial neural network for predicting energy absorption capability of thermoplastic commingled composites. Compos. Struct. 2021, 257, 113–131. doi:10.1016/j.compstruct.2020.113131. [Google Scholar]

- Di Benedetto RM, Raponi OA, Junqueira DM, Ancelotti Junior AC. Crashworthiness and Impact Energy Absorption Study Considering the CF/PA Commingled Composite Processing Optimization. Mater. Res. 2017, 20, 792–799. doi:10.1590/1980-5373-mr-2017-0777. [Google Scholar]

- Di Benedetto RM, Botelho EC, Gomes GF, Junqueira DM, Ancelotti Junior AC. Impact Energy Absorption Capability of Thermoplastic Commingled Composites. Compos. Part. B Eng. 2019, 176, 107307. doi:10.1016/j.compositesb.2019.107307. [Google Scholar]

- Chawla KK. Composite Materials: Science and Engineering; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto S, Ohnishi E, Sato H, Hoshina H, Ishikawa D, Ozaki Y. Low-Frequency Vibrational Modes of Nylon 6 Studied by Using Infrared and Raman Spectroscopies and Density Functional Theory Calculations. J. Phys. Chem. B 2019, 123, 5368–5376. doi:10.1021/acs.jpcb.9b04347. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S. Selective Laser Sintering/Melting. Compr. Mater. Process Thirteen. Vol. Set. 2014, 10, 93–134. doi:10.1016/B978-0-08-096532-1.01003-7. [Google Scholar]

- Strong AB. Thermoplastic Composites. In Fundamentals of Composites Manufacturing—Materials, Methods and Applications; Society of Manufacturing Engineers: Southfield, MI, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Chang IY, Lees JK. Recent Development in Thermoplastic Composites: A Review of Matrix Systems and Processing Methods. J. Thermoplast. Compos. Mater. 1998, 1, 277–296. doi:10.1177/089270578800100305. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell FC. Structural Composite Materials; ASM International: Materials Park, OH, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Van West BP, Pipes RB, Advani SG. The consolidation of commingled thermoplastic fabrics. Polym. Compos. 1991, 12, 417–427. doi:10.1002/pc.750120607. [Google Scholar]

- Mc Grath JE. Advances in polymer matrix composites. Polymer 1993, 34, 675. doi:10.1016/0032-3861(93)90346-C. [Google Scholar]

- Bafna SS, Sun T, Baird DG. The role of partial miscibility on the properties of blends of a polyetherimide and two liquid crystalline polymers. Polymer 1993, 34, 708–715. doi:10.1016/0032-3861(93)90352-B. [Google Scholar]

- Luo Y, Verpoest I, Hoes K, Vanheule M, Sol H, Cardon A. Permeability measurement of textile reinforcements with several test fluids. Compos. Part. A 2001, 32, 1497–1504. doi:10.1016/S1359-835X(01)00049-5. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigez E, Giacomelli F, Vazquez A. Permeability-Porosity Relationship in RTM for Different Fiberglass and Natural Reinforcements. J. Compos. Mater. 2004, 38, 259–268. doi:10.1177/0021998304039269. [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z, Ye L, Lu M. Permeability Predictions for Woven Fabric Preforms. J. Compos. Mater. 2010, 44, 1569–1586. doi:10.1177/0021998309355888. [Google Scholar]

- Han KK, Lee CW, Rice BP. Measurements of the permeability of fiber preforms and applications. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2000, 60, 2435–2441. doi:10.1016/S0266-3538(00)00037-3. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt TM, Goss TM, Amico SC. Permeability of Hybrid Reinforcements and Mechanical Properties of their Composites Molded by Resin Transfer Molding. J. Reinf. Plast. Compos. 2009, 28, 2839–2850. doi:10.1177/0731684408093974. [Google Scholar]

- Vernet N, Ruiz E, Advani S, Alms JB, Aubert M, Barburski M, et al. Experimental determination of the permeability of engineering textiles: Benchmark II. Compos. Part. A 2014, 61, 172–184. doi:10.1016/j.compositesa.2014.02.010. [Google Scholar]

- Arter R, Beraud JM, Binetruy C, Bizet L, Breard J, Cardona S, et al. Experimental determination of the permeability of textiles: A benchmark exercise. Compos. Part. A 2014, 42, 1157–1168. doi:10.1016/j.compositesa.2011.04.021. [Google Scholar]

- Amico S, Lekakou C. An experimental study of the permeability and capillary pressure in resin-transfer moulding. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2001, 61, 1945–1959. doi:10.1016/S0266-3538(01)00104-X. [Google Scholar]

- Mc Lauchlin AR, Ghita OR, Savage L. Studies on the reprocessability of poly(ether ether ketone) (PEEK). J. Mater. Process Technol. 2014, 214, 75–80. doi:10.1016/j.jmatprotec.2013.07.010. [Google Scholar]

- Pan L, Yapici U. A comparative study on mechanical properties of carbon fiber/PEEK composites. Adv. Compos. Mater. 2016, 25, 359–374. doi:10.1080/09243046.2014.996961. [Google Scholar]

- Cheremisinoff NP. Processing of Advanced Thermoplastic Composites. In Advanced Polymer Processing Operations; Elsevier: Norwich, NY, USA, 1998; pp. 167–212. [Google Scholar]

- Wu C. Effects of Carbon Fiber Treatment on Interfacial Properties of Advanced Thermoplastic Composites. Polym. J. 1997, 29, 705–707. doi:10.1295/polymj.29.705. [Google Scholar]

- Boglea A, Olowinsky A, Gillner A. Fibre laser welding for packaging of disposable polymeric microfluidic-biochips. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2007, 254, 1174–1178. doi:10.1016/j.apsusc.2007.08.013. [Google Scholar]

- Yousefpour A, Hojjati M, Immarigeon J. Fusion Bonding/Welding of Thermoplastic Composites. J. Thermoplast. Compos. Mater. 2004, 17, 303–341. doi:10.1177/0892705704045187. [Google Scholar]

- Luo T, Hu Y, Zhang M, Jia P, Zhou Y. Recent advances of sustainable and recyclable polymer materials from renewable resources. Resour. Chem. Mater. 2025, 4, 100085. doi:10.1016/J.RECM.2024.10.004. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell FC. Polymer Matrix Composites; Elsevier: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Song Q, Liu W, Chen J, Zhao D, Yi C, Liu R, et al. Research on Void Dynamics during In Situ Consolidation of CF/High-Performance Thermoplastic Composite. Polymers 2022, 14, 1401. doi:10.3390/polym14071401. [Google Scholar]

- Long AC, Wilks CE, Rudd CD. Experimental characterisation of the consolidation of a commingled glass/polypropylene composite. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2001, 61, 1591–1603. doi:10.1016/S0266-3538(01)00059-8. [Google Scholar]

- Ren P, Hou S, Ren F, Zhang Z, Sun Z, Xu L. The Influence of Compression Molding Techniques on Thermal Conductivity of UHMWPE/BN and UHMWPE/(BN + MWCNT) Hybrid Composites with Segregated Structure. Compos. Part. A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2016, 90, 13–21. doi:10.1016/j.compositesa.2016.06.019. [Google Scholar]

- Lin HH, Ranganathan S, Advani SG. Consolidation of Continuous Fiber Systems. In Flow and Rheology in Polymer Composites Manufacturing: Composite Materials Science Series; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1994; Volume 10, pp. 325–358. [Google Scholar]

- Howell DD, Fukumoto S. Compression Molding of Long Chopped Fiber Thermoplastic Composites. In Composites and Advanced Materials Expo; TenCate Advanced Composites: Orlando, FL, USA, 2014; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Vaneker THJ, Kuiper S, Willemstein N, Baran I. Effects of nozzle design on CFRP print quality using Commingled Yarn. Procedia CIRP 2023, 120, 1492–1497. doi:10.1016/J.PROCIR.2023.09.200. [Google Scholar]

- Compton BG, Post BK, Duty CE, Love L, Kunc V. Thermal analysis of additive manufacturing of large-scale thermoplastic polymer composites. Addit. Manuf. 2017, 17, 77–86. doi:10.1016/J.ADDMA.2017.07.006. [Google Scholar]

- Brasington A, Sacco C, Halbritter J, Wehbe R, Harik R. Automated fiber placement: A review of history, current technologies, and future paths forward. Compos. Part. C Open Access 2021, 6, 100182. doi:10.1016/J.JCOMC.2021.100182. [Google Scholar]

- Cai H, Chen Y. A Review of Print Heads for Fused Filament Fabrication of Continuous Carbon Fiber-Reinforced Composites. Micromachines 2024, 15, 432. doi:10.3390/mi15040432. [Google Scholar]

- Turner BN, Strong R, Gold SA. A review of melt extrusion additive manufacturing processes: I. Process design and modeling. Rapid Prototyp. J. 2014, 20, 192–204. doi:10.1108/RPJ-01-2013-0012. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong W, Li F, Zhang Z, Song L, Li Z. Short fiber reinforced composites for fused deposition modeling. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2001, 301, 125–130. doi:10.1016/S0921-5093(00)01810-4. [Google Scholar]

- Elsonbaty AA, MRashad A, Abass OY, Abdelghany TA. A Survey of Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM) Technology in 3D Printing. J. Eng. Res. Reports 2024, 26, 304–312. doi:10.9734/jerr/2024/v26i111332. [Google Scholar]

- He Q, Wang H, Fu K, Ye L. 3D printed continuous CF/PA6 composites: Effect of microscopic voids on mechanical performance. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2020, 191, 108077. doi:10.1016/j.compscitech.2020.108077. [Google Scholar]

- Liao B, Yang H, Ye B, Xi L. Microscopic void distribution of 3D printed polymer composites with different printing direction. Mater. Lett. 2023, 341, 134236. doi:10.1016/J.MATLET.2023.134236. [Google Scholar]

- Santos NV, Giubilini A, Cardoso DCT, Minetola P. Exploring printing methods for continuous natural fiber-reinforced thermoplastic biocomposites: A comparative study. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 2025, 43, e01253. doi:10.1016/j.susmat.2025.e01253. [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y, Yang B, Chang Z, Duan J, Chen W. Research Status of and Prospects for 3D Printing for Continuous Fiber-Reinforced Thermoplastic Composites. Polymers 2023, 15, 3653. doi:10.3390/polym15173653. [Google Scholar]

- Iragi M, Pascual-González C, Esnaola A, Lopes CS, Aretxabaleta L. Ply and interlaminar behaviours of 3D printed continuous carbon fibre-reinforced thermoplastic laminates; effects of processing conditions and microstructure. Addit. Manuf. 2019, 30, 100884. doi:10.1016/J.ADDMA.2019.100884. [Google Scholar]

- Uşun A, Gümrük R. The mechanical performance of the 3D printed composites produced with continuous carbon fiber reinforced filaments obtained via melt impregnation. Addit. Manuf. 2021, 46, 102112. doi:10.1016/J.ADDMA.2021.102112. [Google Scholar]

- Rinaldi M, Ghidini T, Cecchini F, Brandao A, Nanni F. Additive layer manufacturing of poly (ether ether ketone) via FDM. Compos. Part. B Eng. 2018, 145, 162–172. doi:10.1016/J.COMPOSITESB.2018.03.029. [Google Scholar]

- Luo M, Tian X, Shang J, Zhu W, Li D, Qin Y. Impregnation and interlayer bonding behaviours of 3D-printed continuous carbon-fiber-reinforced poly-ether-ether-ketone composites. Compos. Part. A 2019, 121, 130–138. doi:10.1016/j.compositesa.2019.03.020. [Google Scholar]

- Pagliarulo V, Russo P, Leone G, D’Angelo GA, Ferraro P. A multimodal optical approach for investigating 3D-printed carbon PEEK composites. Opt. Lasers Eng. 2022, 151, 106888. doi:10.1016/J.OPTLASENG.2021.106888. [Google Scholar]

- Caminero MA, Chacón JM, García-Moreno I, Reverte JM. Interlaminar bonding performance of 3D printed continuous fibre reinforced thermoplastic composites using fused deposition modelling. Polym. Test. 2018, 68, 415–423. doi:10.1016/J.POLYMERTESTING.2018.04.038. [Google Scholar]

- Liu T, Tian X, Zhang Y, Cao Y, Li D. High-pressure interfacial impregnation by micro-screw in-situ extrusion for 3D printed continuous carbon fiber reinforced nylon composites. Compos. Part. A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2020, 130, 105770. doi:10.1016/J.COMPOSITESA.2020.105770. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Qiao J, Zhang G, Li Y, Li L. Prediction of deformation and failure behavior of continuous fiber reinforced composite fabricated by additive manufacturing. Compos. Struct. 2021, 265, 113738. doi:10.1016/J.COMPSTRUCT.2021.113738. [Google Scholar]

- Pandelidi C, Bateman S, Maghe M, Piegert S, Brandt M. Fabrication of continuous carbon fibre-reinforced polyetherimide through fused filament fabrication. Prog. Addit. Manuf. 2022, 7, 1093–1109. doi:10.1007/s40964-022-00284-9. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao D, Liu W, Chen J, Yue G, Song Q, Yang Y. Interlaminar bonding of high-performance thermoplastic composites during automated fiber placement in-situ consolidation. J. Compos. Mater. 2024, 58, 2247–2261. doi:10.1177/00219983241263808. [Google Scholar]

- Ueda M, Kishimoto S, Yamawaki M, Matsuzaki R, Todoroki A, Hirano Y, et al. 3D compaction printing of a continuous carbon fiber reinforced thermoplastic. Compos. Part. A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2020, 137, 105985. doi:10.1016/j.compositesa.2020.105985. [Google Scholar]

- Van West BP, Pipes RB, Keefe M, Advani SG. The draping and consolidation of commingled fabrics. Compos. Manuf. 1991, 2, 10–22. doi:10.1016/0956-7143(91)90154-9. [Google Scholar]

- Batch GL, Cumiskey S, Macosko CW. Compaction of Fiber Reinforcements. Polym. Compos. 2004, 23, 307–318. doi:10.1002/pc.10433. [Google Scholar]

- Nayana V, Kandasubramanian B. Advanced polymeric composites via commingling for critical engineering applications. Polym. Test. 2020, 91, 106774. doi:10.1016/J.POLYMERTESTING.2020.106774. [Google Scholar]

- Zhuo P, Li S, Ashcroft IA, Jones AI. Continuous fibre composite 3D printing with pultruded carbon/PA6 commingled fibres: Processing and mechanical properties. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2022, 221, 109341. doi:10.1016/J.COMPSCITECH.2022.109341. [Google Scholar]

- Bourgeois ME, Donald DW. Consolidation and Tow Spreading of Digitally Manufactured Continuous Fiber Reinforced Composites from Thermoplastic Commingled Tow Using a Five-Axis Extrusion System. J. Compos. Sci. 2021, 5, 73. doi:10.3390/jcs5030073. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Yang W, Li Y. Process-dependent multiscale modeling for 3D printing of continuous fiber-reinforced composites. Addit. Manuf. 2023, 73, 103680. doi:10.1016/J.ADDMA.2023.103680. [Google Scholar]

- Fu Y, Dong Y. Multiscale coupling analysis of energy absorption in 3D printed continuous fiber reinforced thermoplastic orthogonal fabric composites. Addit. Manuf. 2024, 84, 104084. doi:10.1016/J.ADDMA.2024.104084. [Google Scholar]

- Fu Y, Kan Y, Fan X, Xuan S, Yao X. Novel designable strategy and multi-scale analysis of 3D printed thermoplastic fabric composites. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2022, 222, 109388. doi:10.1016/J.COMPSCITECH.2022.109388. [Google Scholar]

- Fu Y, Yao X. Multi-scale analysis for 3D printed continuous fiber reinforced thermoplastic composites. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2021, 216, 109065. doi:10.1016/J.COMPSCITECH.2021.109065. [Google Scholar]