CRISPR-Armed Phages: Design, Mechanisms, Applications, and Prospects in Precision Microbiome Engineering

Received: 02 October 2025 Revised: 19 November 2025 Accepted: 05 December 2025 Published: 11 December 2025

© 2025 The authors. This is an open access article under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

1. Introduction

The microbiome, a complex assemblage of microorganisms colonizing various ecological niches (e.g., human gut, soil, and aquatic environments), plays a pivotal role in maintaining host health, nutrient cycling, and ecosystem stability [1,2,3]. However, the dysregulation of microbial communities, such as the overgrowth of pathogenic bacteria or the acquisition of antibiotic resistance genes, often leads to severe consequences, including infectious diseases, metabolic disorders, and the disruption of ecological balance [4].

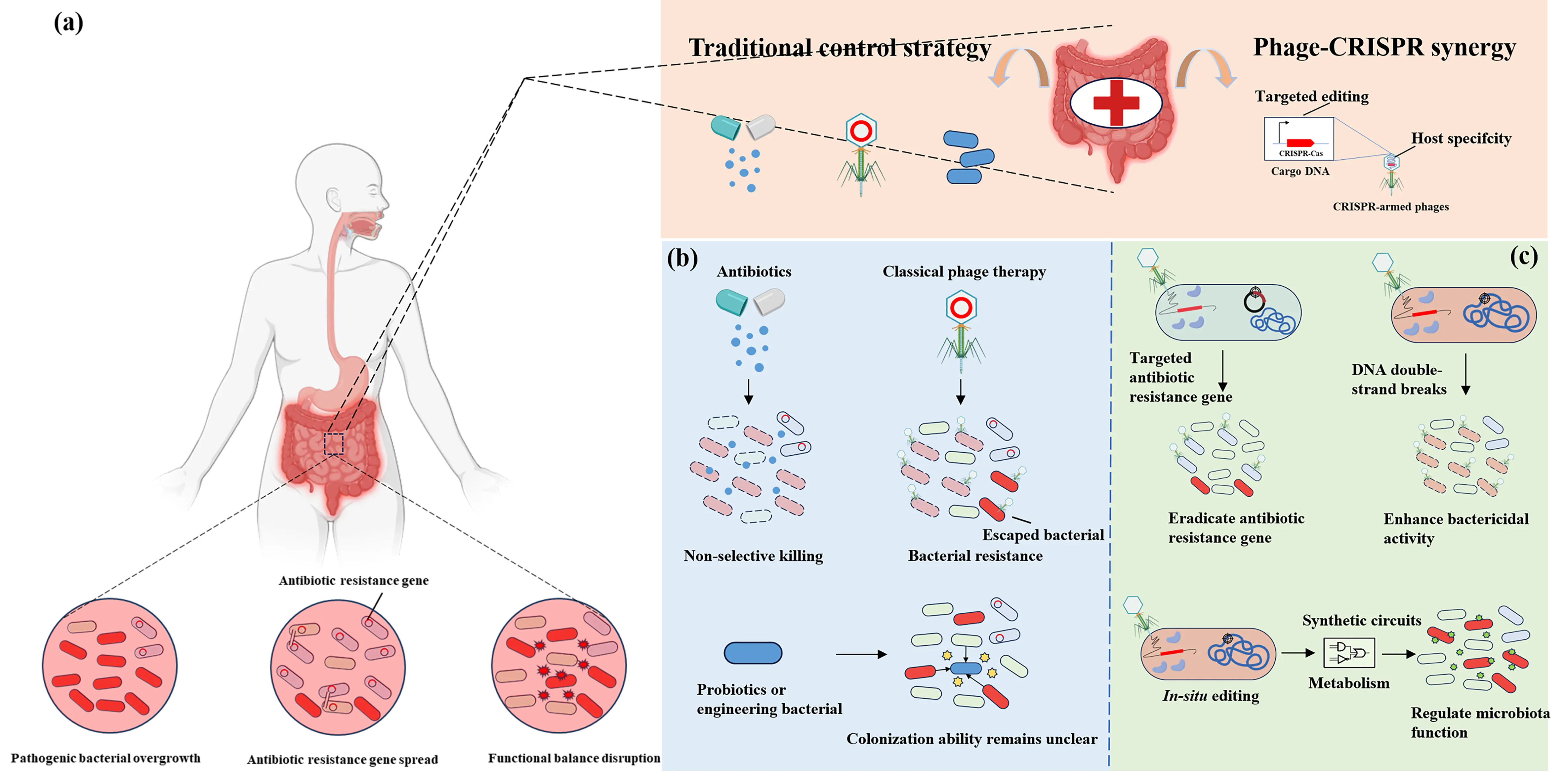

To address microbiome dysregulation, a variety of modulation strategies have been developed, each with distinct advantages alongside inherent limitations (Figure 1). Broad-spectrum antibiotics such as streptomycin and β-lactams, for instance, exert non-specific inhibitory or bactericidal effects that can rapidly alleviate acute infections, but they often disrupt beneficial microbial populations like gut-residing Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus while driving the evolution of multidrug-resistant strains [5]. In contrast to the non-specificity of antibiotics, classical phage therapy leverages natural phages to lyse target bacteria. It thus boasts high host specificity, yet it is constrained by bacterial defense mechanisms, including restriction-modification systems and endogenous CRISPR-Cas immunity, as well as a narrow host range—natural phages typically target only 1 to 2 strains within a single bacterial species [6]. Single-strain biotherapeutics, encompassing probiotics like Saccharomyces boulardii and Lactobacillus rhamnosus, modulate the microbiome by competing for nutrients or producing antibacterial metabolites, but their efficacy is often strain-dependent and lacks the capacity for targeted regulation of pathogenic or resistant bacteria [7,8]. Recent advances in synthetic biology have facilitated the development of engineered microorganisms for applications. For instance, Lactococcus lactis can be designed to secrete the anti-inflammatory protein heme oxygenase-1 to alleviate colitis symptoms in mice [9]; engineered Escherichia coli can function as a cancer biosensor, bind to colorectal cancer cells, or convert dietary metabolites into anticancer compounds [10,11]. However, engineered bacteria require frequent administration, which not only increases treatment costs but also reduces patient compliance. To improve bacterial survival rate, control residence time, and achieve targeted delivery of microorganisms to specific sites in the gastrointestinal tract, complex formulations are indispensable, potentially further driving up costs [12]. Additionally, even if the introduced strains can achieve stable colonization, they may compete with endogenous commensal bacteria, which is detrimental to the balance of the microbial ecosystem.

One promising strategy is to directly modify the endogenous microbiota within its natural environment, a method commonly referred to as in situ microbiome engineering. Its core lies in delivering transgenes to specific members of the endogenous microbiota. This “microbiome gene therapy” offers significant advantages: editing long-colonized species enables genetically modified bacteria to persist longer, holding promise for stable colonization, which in turn reduces the frequency of administration and lowers the overall treatment cost; additionally, it does not directly alter the composition of the microbiome, exerting minimal impact on other members of the ecosystem and thus avoiding disrupting its delicate balance.

Figure 1. Microbiome dysregulation scenarios and modulation strategies. (a) Three core scenarios of microbiome dysregulation: pathogenic bacterial overgrowth, antibiotic resistance gene spread, and disruption of functional balance. (b) Traditional microbiome modulation strategies: Broad-spectrum antibiotics exert non-selective killing of microorganisms, which can disrupt microbial community balance and induce antimicrobial resistance. Classic phage therapy lyses specific host bacteria but tends to trigger bacterial resistance and suffers from a narrow host range. Probiotics or engineered bacteria can modulate or reconstitute the microbiome; however, they fail to achieve targeted regulation of pathogenic bacteria or drug-resistant strains. Meanwhile, these approaches face challenges, including competition with endogenous commensal bacteria and difficulties with long-term colonization. (c) CRISPR-armed phages: These phages can precisely target pathogenic bacteria while preserving beneficial microorganisms. The integration of CRISPR-based gene editing technology further expands its application scenarios: on one hand, it can utilize the nuclease activity of the CRISPR system to damage the host DNA, thereby enhancing the bactericidal activity of the bacteriophage; on the other hand, it can rely on the targeting capability of the CRISPR system to accurately eliminate pathogenic genes or drug-resistant genes; in addition, it can directly modify the functions of specific bacterial strains in the microbiome through the editing function of the CRISPR system.

The discovery of the CRISPR-Cas system, an adaptive immune mechanism inherent in bacteria and archaea, has revolutionized the field of gene editing and microbiology [13,14]. Characterized by sequence-specific nucleic acid recognition and cleavage, CRISPR-Cas systems enable precise manipulation of microbial genomes, offering unprecedented potential for targeted regulation of the microbiome [15]. However, a critical bottleneck in translating CRISPR-Cas technology into microbiome engineering lies in efficient and specific delivery: naked CRISPR components are easily degraded by nucleases in complex environments, and non-specific delivery vectors (plasmids or nanoparticles) often fail to target desired microbial strains, and limit their efficacy and safety [16].

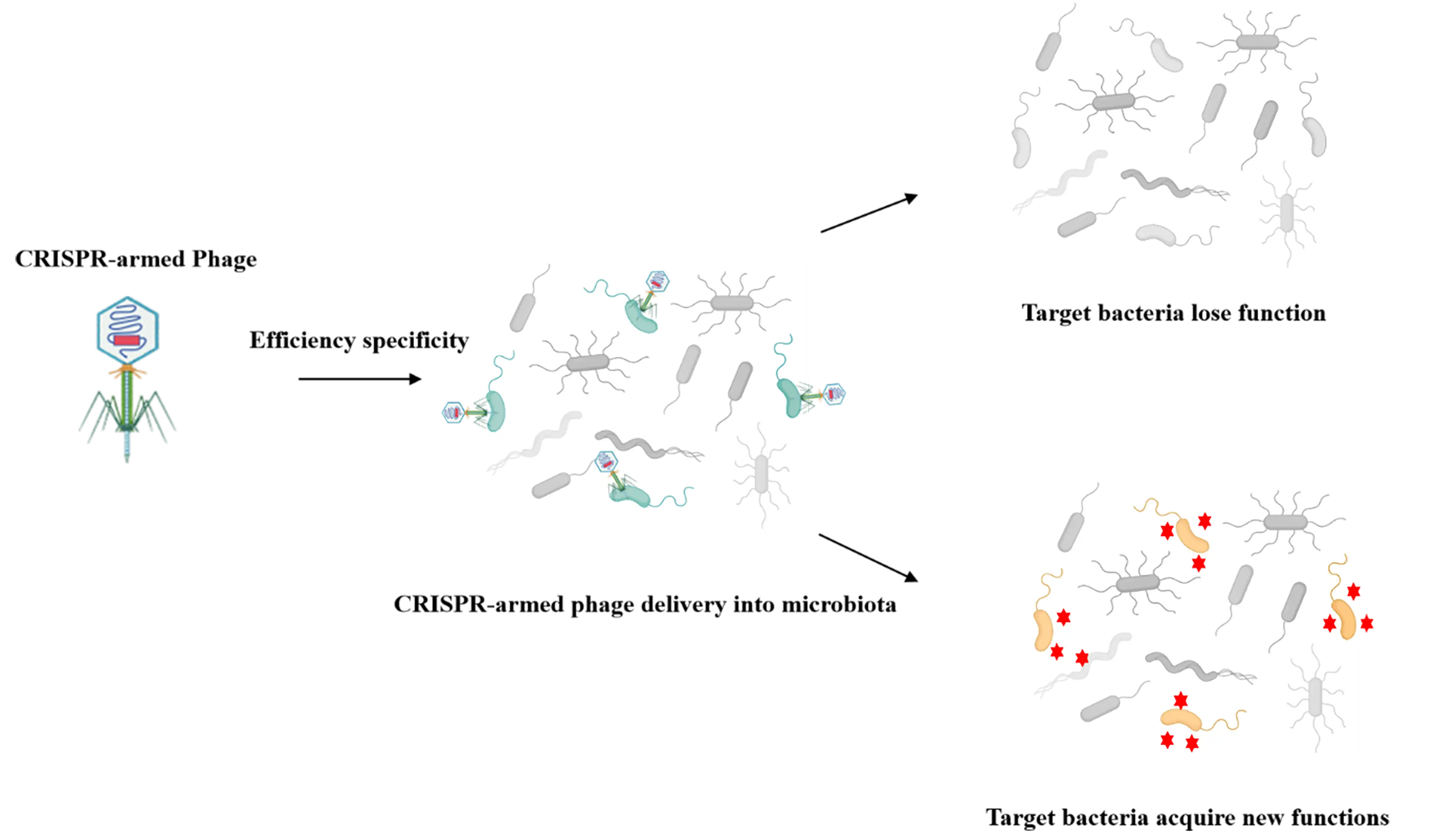

Bacteriophages (phages), natural viral predators of bacteria, have emerged as ideal carriers to address this delivery challenge [17]. Phages exhibit inherent host specificity, mediated by the interaction between their receptor-binding proteins (RBPs) and unique receptors on bacterial cell surfaces [18]. This specificity ensures that phages deliver cargo molecules exclusively to target strains, thereby preventing adverse impacts on the balance of the microbial ecosystem. Additionally, phages can be genetically engineered to carry CRISPR-Cas systems, leveraging their life cycles (lytic or lysogenic) for either transient or sustained cargo expression. For instance, lytic phages enable rapid delivery of CRISPR-Cas systems to kill pathogenic bacteria, while temperate phages can integrate into the host genome to achieve long-term gene regulation without disrupting bacterial viability [19]. The combination of these two technologies enables the construction of CRISPR-armed phages. This approach not only capitalizes on the “targeted delivery” property of phages but also leverages the “precision editing” advantage of the CRISPR-Cas system, thereby providing an unprecedented level of controllability for regulating the composition and function of microbial communities.

This article systematically reviews the design, mechanism of action, and applications of CRISPR-armed phages in microbiome engineering. First, the article discusses different types of CRISPR-Cas systems based on their structural and functional characteristics, and elaborates in detail on how each system exerts its regulatory effects after being delivered by phages. Subsequently, the article discusses the engineering strategies for phage vectors (integrative and non-integrative types) and their respective applications in ecological regulation (strain-specific clearance) and genetic regulation (gene editing) of the microbiome. Finally, the review analyzes current limitations and future development prospects, aiming to provide a comprehensive theoretical framework for promoting the development of this transformative technology.

2. Phage-Mediated Delivery of CRISPR-Cas Systems: Mechanisms and Engineering Strategies

In recent years, significant progress has been made in optimizing phage vectors and expanding the CRISPR-Cas toolbox for microbiome regulation. Different CRISPR-Cas subtypes exhibit distinct mechanisms of nucleic acid targeting and cleavage, making them suitable for diverse applications from the rapid elimination of pathogenic bacteria to the in situ modification of bacterial genes. Concurrently, engineered phages have been classified into integrative and non-integrative types based on their life-cycle characteristics, each tailored to specific regulatory needs (long-term gene repression or transient gene editing). This chapter systematically reviews the classification, molecular mechanisms, and engineering strategies of phage-delivered CRISPR-Cas systems, aiming to provide a comprehensive framework for advancing this cutting-edge technology in basic research and clinical translation.

2.1. Phage-Delivered CRISPR-Cas Systems

The CRISPR-Cas system is an adaptive immune system derived from bacteria and archaea [20]. The CRISPR-Cas gene cluster structure consists of a CRISPR locus containing clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPRs) and adjacent genes encoding effector Cas proteins, with classification based on the subunit number and structure of these effector Cas proteins [21,22].

According to differences in function and structure, CRISPR-Cas systems can be divided into two major classes (Class I and Class II) [23]. Each class is further categorized based on the structure of Cas proteins: Class I encompasses Type I, Type III, and Type IV systems, corresponding to Cas3, Cas10, and Csf1 proteins, respectively [24]; Class II includes Type II, Type V, and Type VI systems, with the respective Cas proteins being Cas9, Cas12, and Cas13 [25]. Different classes possess unique functional module compositions. For instance, Class I systems rely on the synergistic assembly of multiple Cas proteins into a complex to execute the immune response [24], whereas Class II systems can independently accomplish the “recognition-cleavage” process via a single-subunit Cas protein [26]. These differences endow them with diverse application potentials in microbiome regulation (Table 1).

Table 1. Phage-Delivered CRISPR-Cas Systems.

|

Gene Editing Tool |

Type |

Target |

Mechanism |

Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

CRISPR-Cas3 |

Class I (Type I) |

dsDNA |

Cascade binds to target DNA and recruits Cas3 nuclease to degrade DNA. |

1. Can target multiple sequences simultaneously (CRISPR array); 2. Capable of degrading long DNA fragments, ensuring high bactericidal efficiency. |

|

CRISPR-Cas9 |

Class II (Type II) |

dsDNA |

Dual nuclease domains (HNH/RuvC) cleave DNA, generating blunt-end breaks. |

High targeting specificity and most widely used. |

|

CRISPR-Cas13a |

Class II (Type VI) |

ssRNA |

After binding to target RNA, it activates the HEPN domain to degrade RNA non-specifically. |

1. Requires PFS; 2. Only targets RNA, avoiding DNA damage stress; 3. Reduces the risk of bacterial antibiotic resistance evolution. |

|

CRISPR Base Editor (CBE/ABE) |

dsDNA |

Fusing deaminase with inactive Cas (dCas) enables point mutations without double-strand breaks. |

1. No risk of random indels or chromosomal abnormalities; 2. Non-lethal regulation that does not affect bacterial survival. |

|

|

CRISPRi |

dsDNA |

Using inactive Cas proteins to block transcription. |

1. Non-cleaving regulation with no risk of genomic damage; 2. Reversibility of regulation. |

|

|

CRISPR-associated Transposons |

Class I (Type I-B/I-D/I-F), Class II (Type V-K) |

dsDNA |

With the assistance of crRNA and Cas proteins, DNA is precisely inserted into the genome via a transposition mechanism analogous to that of the Tn7 transposon. |

1. Capable of inserting large DNA fragments; 2. High insertion efficiency. |

2.1.1. CRISPR-Cas3

CRISPR-Cas3 belongs to the Type I within the Class I CRISPR-Cas systems [27]. Compared with the Class II CRISPR-Cas9 system, it exhibits significant differences in complex composition, target DNA acting mode, and functional effects. Its core characteristic lies in the synergistic action of the 5′→3′ helicase activity and nuclease activity of the Cas3 protein [28], which enables unidirectional and long-fragment degradation of target DNA (as opposed to the site-specific double-strand breaks (DSBs) induced by Cas9). This process relies on close coordination between the Cascade (CRISPR-associated complex for antiviral defense) complex and the Cas3 protein [29], and the two sequentially complete the entire molecular chain of “target DNA recognition—binding—recruitment—degradation”.

The Cascade complex is a ribonucleoprotein complex composed of multi-subunit Cas proteins and CRISPR RNA (crRNA) [30]. Specific differences in subunit composition exist among different Type I subtypes (e.g., Type I-E, I-F, and I-C), and their functions include pre-crRNA processing, target DNA recognition, and R-loop structure formation [30]. Cas3 serves as the functional core of the CRISPR-Cas3 system, with a helicase domain at its N-terminus and a nuclease domain at its C-terminus [31]. Upon the binding of the Cascade complex to the Cas3 protein, the helicase domain of Cas3 is activated: it unwinds the target DNA double strand from the R-loop region toward the direction away from the protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) in a 5′→3′ manner, continuously generating ssDNA [32,33]. Meanwhile, the nuclease domain performs specific cleavage using this single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) as a substrate, enabling continuous degradation of long target DNA fragments (up to ~200 kb) along the unwinding direction, which ultimately results in the complete breakage of the target DNA [34].

In microbiome regulation mediated by CRISPR-armed phages, the CRISPR-Cas3 system is primarily used for the targeted elimination of bacteria in the microbiome. Unlike site-specific double-strand breaks (DSBs) induced by Cas9, it possesses the advantage of enabling large-fragment degradation of target genes, thereby ensuring the efficient killing capability of CRISPR-armed phages. Currently, engineered phages carrying the CRISPR-Cas3 system have been applied in bacterial infection mouse models to achieve targeted elimination of Clostridioides difficile [35] and enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli (EHEC) [36], respectively. Recently, LBP-EC01, a CRISPR-Cas3-enhanced phage cocktail, has undergone a phase 2 clinical trial in humans [37]. In the treatment of uncomplicated urinary tract infections (UTIs) caused by E. coli, this cocktail achieved rapid clearance of E. coli and complete resolution of clinical symptoms.

2.1.2. CRISPR-Cas9

As a typical representative of Class II CRISPR-Cas systems, CRISPR-Cas9 has become the most widely used gene-editing tool currently, thanks to its advantages of high targeting accuracy and strong operational simplicity [15]. Its core working mechanism relies on the binary complex formed by Cas9 nuclease and guide RNA (gRNA) [38], and the editing process can be divided into three key stages: target site recognition, DNA cleavage, and damage repair.

Cas9 consists of two nuclease domains responsible for DNA strand cleavage (Ruv-C nuclease domain and HNH nuclease domain) and one recognition domain that interacts with gRNA [38]. After Cas9 protein forms a complex with gRNA, it precisely recognizes and binds to the target DNA containing a protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) sequence (e.g., NGG) through the 20-nucleotide sequence of gRNA [39]. Subsequently, the two nuclease domains of Cas9 cleave the double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) at a position 3 base pairs upstream of the PAM, generating DSBs [40]. When cells undergo repair via non-homologous end joining (NHEJ), insertions/deletions (indels) are introduced; alternatively, in the presence of a homologous template, cells can achieve precise gene insertion, replacement, or point mutation correction through homology-directed repair (HDR), thereby realizing targeted editing of the genome [41].

As the earliest studied and most mature CRISPR-Cas system, CRISPR-Cas9 possesses core advantages of high specificity, high efficiency, and ease of design. It has now been widely applied in microbiome regulation and is compatible with a variety of phage vectors, including filamentous phages [42], temperate phages [43], and phagemids [44]. Based on the delivery of the CRISPR-Cas9 system via phages, it is feasible to achieve both compositional regulation of microbial communities and targeted genetic modification of specific microbiomes.

2.1.3. CRISPR-Cas13a

CRISPR-Cas13a belongs to the Type VI CRISPR-Cas system and is the only CRISPR type that relies entirely on RNA-mediated targeting [45]. Cas13a proteins from different sources share high structural similarity, and their core domains can be divided into two categories: RNA recognition domains and nuclease domains. The RNA recognition domain consists of a crRNA-binding domain and a target RNA complementary pairing domain, while the nuclease domain is composed of two HEPN domains [46].

The functional implementation of Cas13a requires three key steps: “crRNA maturation → target RNA recognition → nuclease activity activation”. Its essential mechanism involves the precise targeting of exogenous RNA through RNA-RNA complementary pairing, followed by the cleavage and clearance of invading nucleic acids [47]. First, the CRISPR-Cas system transcribes its own CRISPR array to generate pre-crRNA, which then undergoes “maturation processing” and binds to Cas13a [48]. The mature crRNA binds to Cas13a to form a binary complex, where the HEPN nuclease domain of Cas13a remains in a “repressed state” (inactive). When the complex encounters exogenous RNA, Cas13a recognizes the target RNA via the PFS (Protospacer Flanking Site). Subsequently, the spacer sequence of crRNA undergoes base complementary pairing with the protospacer sequence of the target RNA, forming an RNA duplex [49]. The binding of target RNA induces a conformational change in Cas13a, activating its nuclease activity to trigger specific cleavage and achieve targeted clearance of the exogenous target RNA [50]. More uniquely, Cas13a activated by target RNA binding, also exhibits non-specific RNase activity toward surrounding non-target RNAs. This effect elicits non-adaptive immunity in bacterial hosts, which prevents the spread of infection by inhibiting host growth [51].

The CRISPR-Cas13a system utilizes RNA-guided single-stranded RNA (ssRNA) cleavage activity. After recognizing the mRNA of the target gene, it triggers non-specific RNA degradation, ultimately leading to bacterial cell death. This effect is effective regardless of whether the target gene is located on a plasmid or chromosome. Furthermore, since the CRISPR-Cas13a system does not involve DNA cleavage, it avoids inducing DNA damage stress responses, thereby reducing the risk of bacterial antibiotic resistance evolution. These characteristics render it safer for long-term microbiome regulation. Currently, research teams have achieved sequence-specific bactericidal activity by packaging CRISPR-Cas13a into phage capsids, such as the M13 phage (targeting E. coli) and the 80α phage (targeting Staphylococcus aureus) [52].

2.1.4. CRISPR-Cas Base-Editing

With the optimization of Cas enzymes in CRISPR-Cas systems, a precision tool that eliminates the need for DSBs and exogenous templates has emerged in the field of gene editing, namely CRISPR base editors [53]. As a derivative technology of CRISPR-Cas, its core component is a fusion protein composed of a deaminase and a Cas9 mutant [54]. The Cas9 mutants include Cas9 nickase (Cas9n) and catalytically dead Cas9 (dCas9). The former generates a single-strand break (SSB) through the inactivation of either the HNH or RuvC domain, while the latter completely loses cleavage activity. Both bind to target DNA in an sgRNA-directed manner.

The advantage of base editors lies in overcoming the limitations of traditional CRISPR-Cas9. Conventional Cas9 achieves gene editing through HDR or NHEJ following double-strand cleavage. HDR exhibits low efficiency (mostly <30%) and requires exogenous templates, whereas NHEJ is prone to inducing random insertions/deletions and chromosomal abnormalities [38,55]. In contrast, base editors leverage the synergy between Cas variants and deaminases to directly induce chemical modifications of target bases, triggering the intrinsic base repair machinery. This process enables precise base conversions without generating DSBs, thereby reducing unintended risks [56].

Currently, two major types of base editors are widely applied: cytosine base editors (CBEs) and adenine base editors (ABEs). The former mediates C→U modification, which is converted to C→T (or G→A on the reverse strand) after repair [57]. The latter deaminates adenine to inosine (I), which is repaired to A→G (or T→C on the reverse strand) [58,59]. Base editing technology enables precise regulation of complex microbial communities. For instance, researchers have delivered CBEs into synthetic soil microbial communities using genetically engineered λ phages, achieving precise in situ editing of chromosomal and plasmid genes in target bacteria—both in vitro and within EcoFAB synthetic soil devices [60]. Recently, the ABEs or CBEs were delivered into the gut microbiota of mice by modifying the tail structure of λ phages (Ur-λ subtype) and constructing non-replicative vectors. This approach allows for precise editing of target genes in E. coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae while causing minimal disruption to non-target microbial populations in the gut [61].

2.1.5. CRISPR Interference

CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) is a gene expression inhibition technology engineered from the CRISPR-Cas system [62]. Without altering the genomic sequence, it specifically “silences” transcription of target genes, thereby enabling the investigation of gene function or the regulation of biological metabolic pathways [63]. Owing to its advantages, including high specificity, low off-target effects, and ease of operation, CRISPRi has become one of the core tools in molecular biology, synthetic biology, and functional genomics.

The CRISPRi system mainly relies on the synergistic action of deadCas (dCas) protein and sgRNA to achieve targeted inhibition [64]. Among these components, the dCas protein is derived from the wild-type Cas protein. By introducing mutations into its nuclease-active domains, the dCas protein loses the ability to cleave double-stranded DNA [65]. However, it still retains the capacity to bind to sgRNA and, under the guidance of sgRNA, specifically associates with the target DNA sequence. After the dCas-sgRNA complex binds to the specific region of the target gene, it directly hinders the binding of RNA polymerase to the promoter or blocks the movement of RNA polymerase along the DNA template, thereby completely abrogating the initiation of transcription.

When combined with a sgRNA library, CRISPRi enables efficient genome-wide high-throughput screening [66]. This application facilitates in-depth dissection of bacterial gene functions and exploration of key regulatory pathways. Meanwhile, CRISPRi also possesses flexible dynamic regulation capabilities: by linking inducible promoters to the coding genes of dCas or sgRNA, respectively, precise spatiotemporal control over the expression of these two components can be achieved, thereby realizing “on-demand silencing” of target genes [67]. Currently, in the field of in situ microbiome engineering, researchers have delivered the CRISPR-dCas9 system using bacteriophages, achieving targeted inhibition of specific genes in E. coli within the mouse gut [68]. This study demonstrates the application prospects of utilizing the CRISPRi system to regulate microbiome gene expression at the in situ scale.

2.1.6. CRISPR-Associated Transposons

Traditional CRISPR-Cas systems rely on the induction of DSBs and the host cell’s HDR or NHEJ mechanisms to achieve gene editing, which significantly limits their application in microbiome engineering [38]. The emergence of CRISPR-associated transposase (CAST) systems has brought a revolutionary breakthrough to bacterial genome engineering. Innovatively integrating the sequence programmability of CRISPR-Cas systems with the efficient integration capability of transposases, this system enables targeted gene insertion independent of DNA repair, effectively overcoming the limitations of traditional CRISPR-Cas systems in bacterial editing [69].

The evolutionary origin of CAST systems can be traced back to the adaptive evolution process of Tn7-like transposons. Through bioinformatics studies, certain transposons in bacteria were first discovered to have significant associations with the host CRISPR-Cas systems [70]. Specifically, Tn7-like transposons captured nuclease-deficient CRISPR-Cas systems via at least four independent functional adaptation events, forming a functionally synergistic CRISPR-transposon composite system, namely, the CAST system. These integrated CRISPR-Cas systems can be classified into four subtypes: Type I-B [71], Type I-D [72], Type I-F [73] (all multi-subunit effector complexes), and Type V-K (containing the single-subunit effector protein Cas12k) [74]. Among them, the Type V-K system consists of four proteins: Cas12k, TnsB, TnsC, and TniQ, while the Type I-F CRISPR system comprises components such as Cas7, Cas6, Cas8, TnsA, TnsB, TnsC, and TniQ.

In terms of application performance, although the Type I-F CRISPR system has a complex composition, it exhibits excellent targeted insertion capability and system stability in E. coli. Under non-selective pressure, it can precisely insert 10 kb exogenous DNA fragments into the bacterial genome with nearly 100% efficiency [75]. The application scope of this system has been extended to various bacteria, including Klebsiella oxytoca and Pseudomonas putida. Also, it can achieve site-specific insertion in specific bacterial strains within complex microbial communities [75]. In contrast, the Type V-K CAST system has the advantage of a more compact structure and has been successfully applied to various bacteria of the phylum Proteobacteria [76]. However, the application of this system in E. coli still faces issues such as high off-target rates and co-integration phenomena, which require further optimization.

2.2. Engineering Strategies of Phage Vectors for CRISPR-Cas Delivery

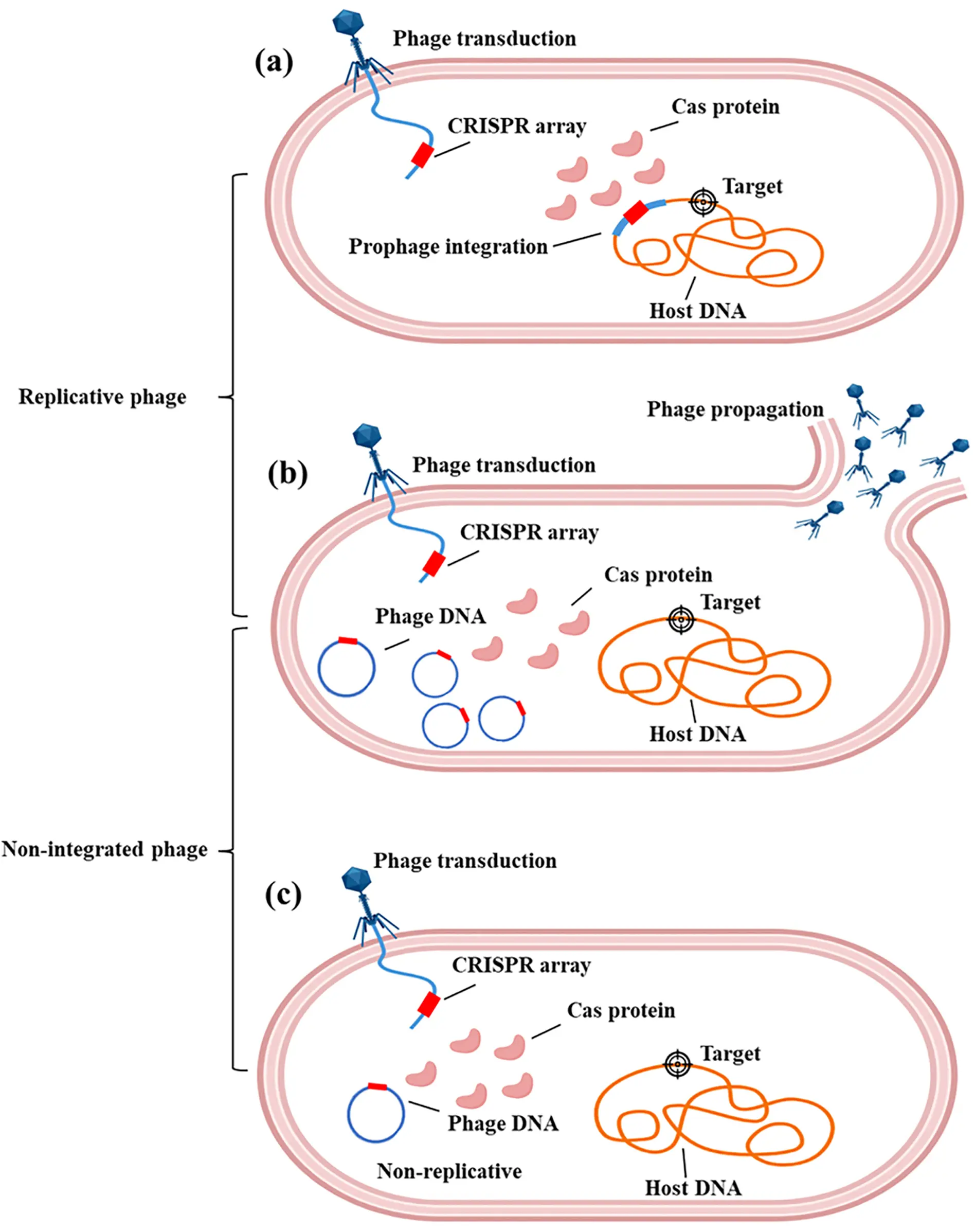

The life cycles of phages can be categorized into the lytic cycle and lysogenic cycle [77]. Virulent phages (e.g., T7 and T4 phages) replicate exclusively through the lytic cycle, which involves lysing infected cells and producing progeny phages [78]. In contrast, temperate phages exhibit a dual-life cycle [79]. They can either enter the lytic cycle to lyse host cells and release progeny or establish a coexistence relationship via the lysogenic cycle. During lysogeny, the phage genome, termed prophage, integrates into the host genome and replicates synchronously with host DNA. When bacteria encounter stressful conditions, the prophage can excise from the host genome, initiate lytic replication, and release progeny phages. These life-cycle distinctions directly influence engineering strategies for phage-mediated gene regulation in microbiomes, leading to the classification of engineered phages into two major types: integrative phages and non-integrative phages (Figure 2) [80].

Figure 2. Engineering phage type. (a) Phages in the lysogenic state integrate the CRISPR-Cas system into the bacterial chromosome; (b) Virulent phages express the CRISPR-Cas cargo during their lytic cycle; (c) Non-replicative phages can only support the transient activity of CRISPR-Cas tools.

2.2.1. Integrative Engineered Phages

A defining feature of integrative engineered phages is their gene integration capability. For practical application, these phages require genetic engineering to overcome the prophage resistance of target bacteria, ultimately enabling stable integration of their genome into the host bacterial chromosome rather than replicating independently in the cytoplasm [81].

This integration capability allows them to persist long-term within host bacteria, facilitating sustained regulation at the genetic level [82]. Temperate λ phages modified via genetic engineering to carry catalytically dead Cas9 (dCas9), tracrRNA, and target-specific crRNA can precisely repress the expression of the rfp gene in E. coli both in vitro and within the mouse gut [68]. Since the phage genome integrates into the host bacterium, its regulatory effects are heritable through bacterial division, enabling long-term, continuous intervention in target bacterial populations without the need for frequent administration.

Another application advantage of integrative engineered phages lies in their minimal disruption to microbial communities. Unlike virulent phages that directly lyse bacteria, integrative engineered phages do not extensively kill target bacteria but only inhibit their pathogenic or antibiotic-resistant functions. This avoids gut microbiota dysbiosis caused by massive bacterial clearance, making them particularly suitable for regulating opportunistic pathogens. Temperate λ phages have been genetically modified to integrate the 933W repressor gene and overcome superinfection exclusion [81]. These modified phages can efficiently infect and lysogenize E. coli harboring the 933W prophage in the mammalian gut, stably maintaining the lysogenic state of the 933W prophage to block expression of Shiga toxin Stx2. A single dose administration significantly reduces Stx2 concentrations in mouse feces without substantially altering the host bacterial load, achieving in situ stable neutralization of virulence factors in gut bacteria.

2.2.2. Non-Integrative Engineered Phage

Non-integrative engineered phages can be classified into two subtypes based on their replication capacity: replicative and non-replicative. The replicative subtype is the most commonly used in traditional phage therapy, following the classic lytic cycle, i.e., adsorption-injection-replication-assembly-release [83]. These phages do not integrate into the host bacterial genome but can utilize the host cell’s metabolic machinery for massive self-replication, ultimately releasing progeny phages through host lysis, forming a self-propagating cycle [84].

There are two main engineering strategies for replicative phages. The first strategy is to directly utilize the lytic properties of virulent phages and insert the CRISPR-Cas system into their genomes [85]. After infecting target bacteria, the CRISPR-Cas system is rapidly expressed to complete editing, followed by host lysis, thereby achieving the dual effect of editing and clearance. The second strategy is to modify temperate phages by knocking out genes involved in integration. These phages lose their lysogenic capacity and only retain the lytic cycle, which enhances the lytic ability of temperate phages [86].

The replicative subtype is primarily used in scenarios requiring rapid, massive clearance of target bacteria, such as combating multidrug-resistant bacteria or acute infections. Its bactericidal effect exhibits amplification, enabling a small input of phages to continuously proliferate after infecting hosts, theoretically maintaining high bactericidal concentrations without repeated administration [87,88].

The non-replicative subtype of engineered phages undergoes genetic modifications such as deleting essential replication genes and disrupting capsid assembly-related sequences. This renders them unable to replicate their genomes or assemble progeny phages after infecting target bacteria. Instead, they solely deliver gene-editing tools to host cells without lysing the host or releasing progeny. These phages are primarily used for in situ gene regulation in the gut microbiome. For example, they can deliver CRISPR-Cas systems or base editors to specific bacteria to achieve gene knockout or repression while preserving bacterial viability [61].

Due to their non-replicative nature, the dosage of editing tools can be precisely controlled, minimizing the risk of spreading to non-target microbiota and reducing horizontal gene transfer. By avoiding bacterial lysis, they maintain gut microbiota balance. The absence of progeny phages also reduces immunogenicity and enhances in vivo safety, making them suitable for long-term mild modulation of gut microbial genes.

3. Applications of CRISPR-Armed Phages in Microbiome Engineering

A current development trend in microbiome engineering is achieving precision regulation. Leveraging sequence-specific targeting capabilities, CRISPR-Cas systems have emerged as exceptional gene-editing tools. With their precise editing capacity, these systems enable specific manipulation of the microbiome. They can not only inhibit the overgrowth of pathogenic bacteria through targeted genomic deletions, but also modify specific genes or regulate the ecology of target bacteria with minimal disruption to the overall genetic background of the microbiome. However, a central challenge in the application of CRISPR-Cas systems lies in their delivery efficiency. Phages, as natural predators of bacteria, provide an effective solution to this bottleneck. They serve as excellent carriers to deliver exogenous CRISPR-DNA, facilitating CRISPR-Cas systems to overcome delivery limitations and exert their functions more effectively on target microorganisms.

3.1. Precise Regulation at the Ecological Level

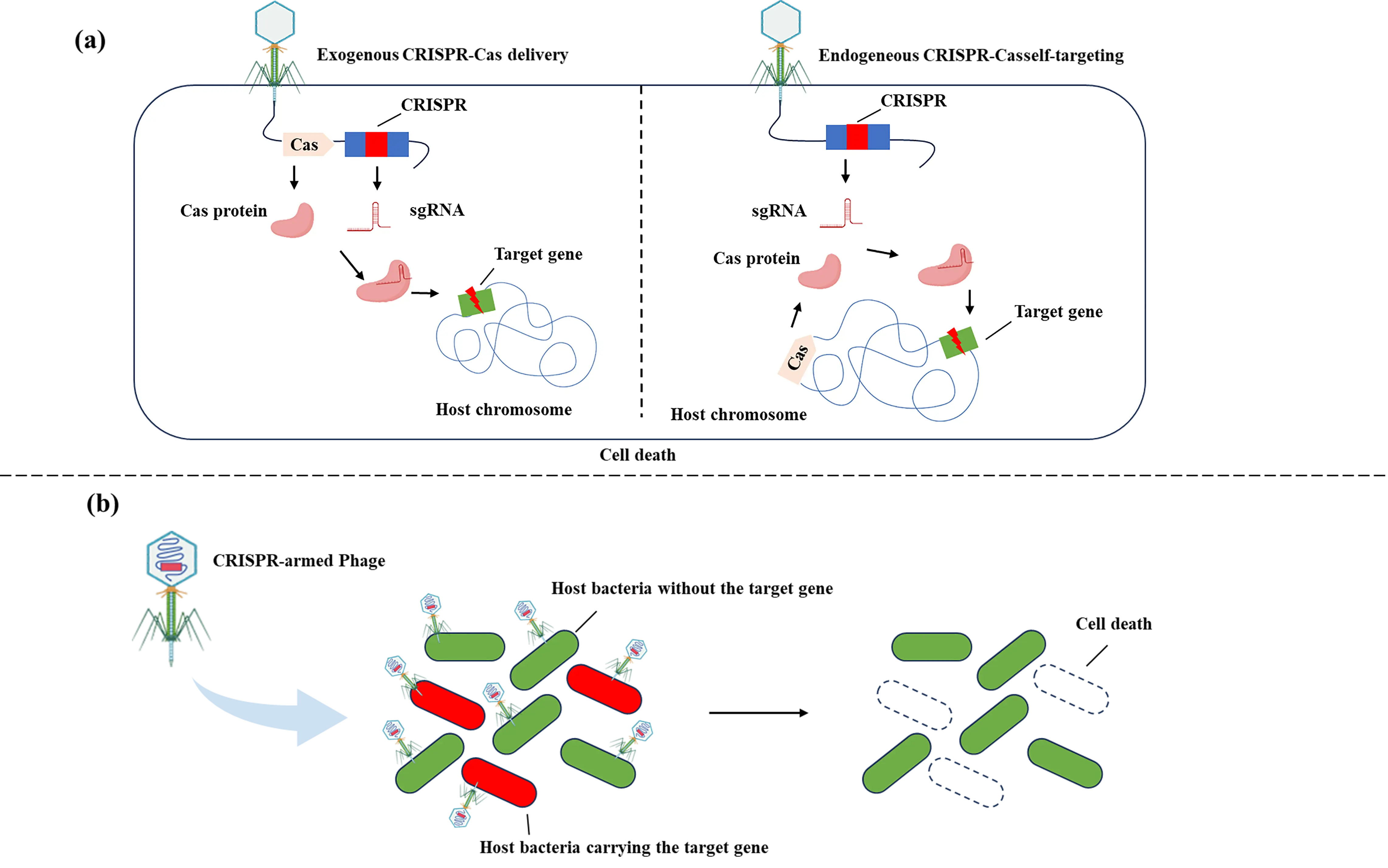

As natural enemies of bacteria, phages possess a core advantage of high host specificity. By recognizing specific receptors on the surface of target bacteria, such as lipopolysaccharides (LPS), capsular polysaccharides, or outer membrane proteins, phages can achieve precise infection of specific bacterial strains without affecting other symbiotic microorganisms [89,90]. However, the antibacterial efficacy of natural phages is highly dependent on their complete life cycle. When encountering defensive systems within bacterial cells, e.g., restriction-modification systems, abortive infection systems, or CRISPR-Cas autoimmune barriers, their infection process is easily interrupted, leading to a significant reduction in killing efficiency or even complete inactivation [91,92]. This limitation greatly limits the application of natural phages for controlling drug-resistant bacteria or strains with active defense mechanisms. By genetically engineering phages to integrate the CRISPR-Cas system into the phage genome, the reliance on the phage’s own life cycle can be eliminated. Instead, the target bacteria are killed through the nucleic acid cleavage mechanism of the CRISPR-Cas system, thereby effectively overcoming the defensive restrictions that bacteria impose on natural phages [93].

The core mechanism by which the CRISPR-Cas system mediates bacterial lethality is closely related to the characteristics of DNA damage repair mechanisms in prokaryotes [94]. Most prokaryotes have an underdeveloped NHEJ repair system, which is unable to efficiently repair Cas protein-mediated DSBs [95]. Therefore, in the absence of a homologous repair template, Cas proteins can precisely induce DSBs at specific loci on the target bacterial chromosome through sgRNA-guided sequence specificity [96]. Due to the ineffective repair of broken ends, bacteria will die from the disruption of genomic integrity. This mechanism provides a molecular basis for achieving precision knockout of specific strains within microbial populations through engineered phage-delivered CRISPR-Cas systems.

Given the widespread distribution of CRISPR-Cas systems in prokaryotes, e.g., CRISPR-Cas loci present in approximately 90% of archaeal genomes and 50% of bacterial genomes, it is possible to deliver only sgRNA via engineered phages in some target strains, utilizing the strain’s own endogenous Cas proteins to mediate DSBs and thereby achieve self-killing [97]. This strategy eliminates the need to deliver the complete CRISPR-Cas system through phages, i.e., no requirement to simultaneously deliver Cas protein-encoding genes, which not only effectively circumvents the problem of low expression efficiency of heterologous Cas proteins in target bacteria, but also overcomes the technical bottleneck of limited packaging capacity of phage capsids for large-molecular-weight DNA, such as fusion fragments of Cas protein genes and sgRNA coding sequences [98,99]. This provides an efficient, low-cost delivery pathway for controlling drug-resistant bacteria, especially strains with multidrug resistance to traditional antimicrobial approaches (Figure 3).

The main conclusions from the aforementioned studies have been fully validated in animal models, laying the groundwork for clinical translation of this strategy. In regulatory studies targeting specific genotypic E. coli, a mouse model of intestinal dysbiosis was first established through streptomycin pretreatment, followed by colonization of the target E. coli strain in the mice. Based on this, the CRISPR-Cas9 system was packaged into engineered phage M13 and delivered via oral administration to achieve intestinal targeting. The research results showed that this system could precisely recognize and cleave specific gene loci in the target E. coli in mice, ultimately achieving efficient targeted knockout of the strain without significant disturbance to the abundance and composition of other symbiotic microorganisms in the intestine [42]. This study not only confirmed the delivery efficiency of engineered phages as CRISPR-Cas system carriers in the complex in vivo microenvironment, but also verified their core advantages of precision regulation with low ecological interference.

For the clinically prevalent C. difficile infection (CDI) [100], the C. difficile-specific phage ΦCD24-2 was used as a carrier, and the gRNAs targeting key genes in the pathogen’s genome, instead of the complete CRISPR-Cas system, were delivered to the pathogen in infected model mice. The endogenous type I CRISPR system of C. difficile itself was employed to mediate nucleic acid cleavage, ultimately achieving efficient targeted killing of the pathogen. In this study, the pathogen’s own immune components were utilized, which not only simplified vector design by eliminating the need to package Cas protein-encoding genes but also avoided potential immunogenicity issues caused by heterologous Cas proteins in vivo. Additionally, it significantly reduced the packaging pressure on phage capsids, providing a more clinically feasible solution for treating refractory infections such as CDI [35]. These two in vivo studies collectively demonstrate that engineered phage-delivered CRISPR-Cas systems have clear application potential for the precise prevention and treatment of pathogenic bacteria, particularly suitable for regulating complex in-situ microbiomes such as those in the intestine.

In practical applications, bacteria may develop resistance by losing components related to the CRISPR-Cas system, e.g., Cas protein-encoding genes or mutations in sgRNA recognition sites, thereby evading the killing effect. To address this potential challenge, the Cas13a protein, characterized by its specific RNA-targeting cleavage activity and a unique collateral cleavage effect triggered upon activation, offers a novel approach for constructing a resistance-evasive antibacterial system. This effect disrupts global RNA homeostasis within bacterial cells, leading to robust growth inhibition. Even if bacteria escape targeted cleavage through mutations, their growth remains significantly suppressed by the collateral effect, effectively reducing the probability of resistance development. Leveraging this property, specific crRNAs targeting bacterial antibiotic resistance genes were designed, e.g., the β-lactam antibiotic resistance gene blaTEM, to deliver the Cas13a system into drug-resistant E. coli via phages [52]. The research results demonstrated that the CRISPR-armed phages not only successfully eliminated the resistance gene mRNA to reduce bacterial drug resistance, but also inhibited bacterial proliferation through the collateral effect. Ultimately, this achieved inhibitory knockout of drug-resistant strains by simultaneously realizing the dual effects of reducing drug resistance and suppressing bacterial growth.

Figure 3. Precision engineering at the ecological level. Regulation at the ecological level aims to eliminate and modulate specific bacterial strains in a targeted manner. (a) Efficient loading of the CRISPR system into bacteriophages can endow phages with new properties, allowing them to eliminate bacteria that are susceptible to phage infection yet not lysed by phages. This type of approach is intended to enhance the lethality of phage infections that originally have no killing effect, or to restrict the host’s defensive responses by degrading the host genome. If the target bacteria themselves carry an endogenous CRISPR-Cas system, only the delivery of a self-targeting CRISPR array is required to guide Cas nucleases to act on the desired sites; another strategy involves the direct delivery of a complete exogenous CRISPR-Cas system via bacteriophages. (b) When targeting and eliminating opportunistic pathogenic commensal bacteria, maintaining a delicate balance is crucial. It is necessary to avoid both excessive elimination and insufficient targeting. By delivering CRISPR via bacteriophages to target virulence/resistance genes, the elimination of target bacteria can be achieved while minimizing disturbance to the microbiome.

3.2. Precise Regulation at the Genetic Level

Beyond the ecological-level regulation strategies discussed earlier, another application direction for CRISPR-armed phages in microbiomes lies in genetic-level regulation. Centered on precision intervention of bacterial phenotypes and elucidation of functional gene roles, genetic-level regulation does not rely on lytic or lethal effects. Instead, it leverages phages to deliver the CRISPR-Cas system for editing or regulating the expression of bacterial functional genes. This approach preserves the strain’s ecological niche while eliminating its harmful functions, or reveals the actual role of genes in the community microenvironment, by providing a more refined, low-risk technical pathway for microbiome regulation (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Precision engineering at the genetic level. Through the delivery of CRISPR systems by bacteriophages, the editing or expression of bacterial functional genes is achieved. This approach enables the elimination of virulence/drug-resistant genes while preserving the ecological niche of bacterial strains, or allows transduced bacterial hosts to express beneficial molecules via the insertion of specific genes, thereby providing a more precise and low-risk technical strategy for microbiome modulation.

By integrating the CRISPR-Cas9 system into the genome of the lysogenic E. coli phage (vB_EcoM-IME365), the constructed vB_Cas9 phage can efficiently eliminate antibiotic resistance plasmids in bacteria, rendering drug-resistant bacteria resusceptible to antibiotics [101]. Compared with traditional lytic phage therapy, this method does not directly induce host lysis, resulting in a lower risk of phage resistance induction. When combined with antibiotic treatment, it can achieve more durable and efficient bactericidal effects. This strategy provides a highly effective and economical new approach to combat antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

Base editing technology has further expanded the application scenarios of CRISPR-armed phages in bacterial phenotype regulation. When the CRISPR-Cas system targets the host chromosome, it may cause cell death. Unlike wild-type Cas proteins, which can induce DSBs, base editing produces only single-strand nicks, a technique with minimal impact on bacterial survival and microbial community structure, making it more suitable for non-lethal regulation. The application potential of this regulatory strategy has been verified in in-situ microbiome engineering research. Researchers integrated the APOBEC-1-based CBE into the non-essential gene region of phage λ [60]. This system can achieve precise C-to-T mutations under the guidance of sgRNA without the need for a repair template. It successfully edited chromosomal genes, e.g., lacZ, with an editing efficiency of 81–98%, and plasmid genes, e.g., mCherry and ampicillin resistance genes, in E. coli without disturbing the surrounding genome. In synthetic soil bacterial communities containing E. coli and Klebsiella species, as well as in EcoFAB simulated soil devices, it achieved a population-editing efficiency of 10–28%, providing a feasible solution for in-situ, precise genetic manipulation of soil microbiomes. Recently, researchers loaded adenine base editors ABE or CBE onto phage λ, achieving efficient editing of the β-lactamase gene (bla) in E. coli within the mouse gut with a median efficiency of 93% by a single dose, and the edited bacteria were stably maintained for over 42 days [61]. They also successfully edited cancer-related colibactin genes (clbH, clbJ), virulence genes (cnf1, csgA), and drug resistance genes (aph(3′)-Ia) in pathogenic E. coli (UTI89, TN03) and K. pneumoniae (ST258). Moreover, 16S sequencing confirmed that this system did not significantly alter the overall composition of the gut microbiota, providing a new solution for precise intervention in the gut microbiome.

dCas9 is a Cas9 mutant with only DNA-targeting and binding capabilities [102]. It can bind to specific sequences and hinder the binding of transcription factors by steric hindrance, thereby inhibiting gene transcription [103]. Unlike Cas9, dCas9 does not cleave DNA but suppresses gene expression solely via physical binding, with no significant impact on bacterial metabolism or proliferation. Furthermore, the reversibility of dCas9 can control dCas9 expression via an inducible promoter and allows target genes to be turned on or off as needed. Researchers inserted dCas9, tracrRNA, and a target-specific crRNA into a non-essential gene region of phage λ, achieving transcriptional inhibition of a specific gene (rfp) in intestinal E. coli [68]. In mouse intestinal experiments, a single dose of this system as low as 5 × 103 pfu maintained a high level of lysogenization efficiency in E. coli. The inhibition efficiency of the rfp gene reached 70–80% and persisted for over 6 days, with no disturbance to the overall composition of the intestinal microbiota.

The CAST system is a newly identified class of CRISPR systems that enables targeted DNA insertion independent of DSBs. It exhibits distinct advantages, including high insertion efficiency, excellent site specificity, and the ability to integrate large DNA fragments. Building on the type I-F CAST system, the DART (DNA-editing all-in-one RNA-guided CRISPR-Cas transposase) system was further developed [104]. Featuring a core “all-in-one” conjugative vector design, this system integrates the CasTn gene, a guide RNA (crRNA/sgRNA), barcode-labeled transposon, and functional cargo (e.g., antibiotic resistance genes, metabolic pathway genes). It is mainly classified into two subtypes, VcDART and ShDART. Among them, VcDART has become mainstream due to its lack of off-target insertion, editing efficiency comparable to that of the traditional mariner transposon, and compatibility with multiple delivery methods. Notably, the DART system breaks through the limitation of traditional gene editing that relies on pure cultured strains. It enables site-specific editing of specific species in complex microbial communities without disrupting the community structure.

Recently, researchers integrated the DART system into the genome of phage λ [105]. This phage-delivered DART system achieved targeted insertion/knockout of the thyA and lacZ genes in E. coli, with edited efficiency exceeding 50% after optimization. Notably, it maintained the ability to specifically edit target strains even in mixed communities containing E. coli, Klebsiella spp., and Burkholderia spp., thereby providing a novel strategy for the in-situ precision engineering of complex microbial communities.

4. Limitations and Prospects of CRISPR-Cas-Engineered Phages

Despite significant progress in CRISPR-armed phages in microbiome engineering, several key limitations remain to be addressed for their widespread clinical and industrial application. These limitations primarily include the narrow host range of phages, the inevitable evolution of bacterial phage resistance, and the insufficient in-situ editing efficiency.

4.1. Limitation of Host Range

In specific scenarios, the high specificity of phages confers significant advantages. When there is a need to eliminate a single pathogenic bacterium while avoiding disruption of the symbiotic microbiota, the precise host-targeting ability effectively prevents impairment of the microbiome homeostasis. For instance, within the human intestinal microecosystem, if only a particular harmful pathogenic bacterium requires clearance, the high specificity of phages ensures that other beneficial microbial communities remain unaffected, thereby maintaining the balance of the intestinal microbial flora [106]. However, in scenarios demanding extensive and consistent modulation of the microbiome across multiple individuals, such as population-level prevention and control of pathogenic bacteria or optimization of gut microbiota function in human populations, the high specificity of phages becomes a limiting factor [107]. Owing to their narrow host range, phages struggle to exert comprehensive effects across a wide range of bacterial species, failing to meet the requirements for large-scale, consistent microbiome modulation. Consequently, the design of phages with an appropriate host range is crucial for enhancing the precision and efficacy of phage therapy.

The targeting specificity and efficiency of phages toward their hosts are primarily determined by RBPs, such as tail fibers, tail spikes, and tail tips, as well as by bacterial cell-surface receptors, including LPS, peptidoglycan, and porins [108]. In recent years, numerous studies have focused on expanding the host range of phages. A growing literature has reported successful expansion of the phage host range through engineering of their RBPs [18]. Additionally, the scope of phage action can be extended by designing engineered phages to deliver diverse effective payloads. Via genetic engineering techniques, specific endolysin genes are introduced into the phage genome, enabling recombinant phages to express and release endolysins following infection of the original host bacteria. These endolysins can lyse other target bacteria beyond the original host through enzymatic hydrolysis. To date, this strategy has achieved expansion of the phage host spectrum in Gram-positive bacteria such as Staphylococcus aureus and Bacillus coagulans, facilitating the coordinated prevention and control of multiple pathogenic bacteria [109,110,111]. The design of phage cocktails targeting different bacterial strains also serves as an effective strategy to achieve more comprehensive bacterial targeting [112]. Formulating a mixed preparation of multiple phages with distinct host specificities allows coverage of a broader range of bacterial species [113]. Simultaneously, designing phage cocktails that target different receptors on specific bacteria not only reduces the development of phage resistance but also minimizes potential antagonistic interactions between phages.

4.2. Challenges of Bacteriophage Resistance

The evolution of bacteriophage resistance in bacteria is inevitable, as bacteria can develop resistance through mutations and other mechanisms [114]. This resistance primarily manifests in two forms: blocking phage invasion and inhibiting phage replication [115]. The first mechanism involves preventing phage adsorption and genome injection into the bacterial host. As previously discussed, the main strategies to address this issue involve engineering phage receptor-binding proteins or formulating phage cocktails. The second mechanism involves complex pathways that arise from the coevolutionary arms race between bacteria and phages [116]. To overcome such bacterial resistance, researchers have focused on enhancing phage bactericidal activity through targeted engineering. Currently, phage-related bacterial killing strategies are mainly categorized into three types. The first is the nucleic acid-targeted degradation method, which involves loading Type II restriction endonucleases onto non-lytic phagemids. Bacterial killing is achieved by leveraging the enzymes’ sequence-specific cleavage of bacterial genomic DNA. During this process, key considerations include the abundance of enzyme recognition sites in the target bacteria, the host range of the phage, and the methylation status of bacterial DNA [117,118]. The second type is the DNA replication inhibition method, which specifically entails inserting the small acid-soluble protein (SASP) gene into temperate phages and replacing their holin genes to ensure the phages remain non-lytic. Subsequently, SASP condenses bacterial chromosomes to inhibit DNA replication. Notably, due to the small molecular size of SASP, it offers the advantage of being easily engineered [119]. The third type is the toxin-like molecule delivery method, e.g., cloning the lethal gene from the toxin-antitoxin system into phagemids to achieve bacterial killing [120], and modifying phages to encode antimicrobial peptides, thereby accelerating the killing effect on planktonic bacteria and biofilm-forming bacteria [121].

4.3. Editing Efficiency of CRISPR-Armed Phages

Delivery efficiency and specificity are critical for the success of in situ editing. The editing efficiency is constrained by three primary factors: CRISPR components, bacteriophage vectors, and host characteristics.

Among these, CRISPR components serve as the core determinants of in situ editing efficiency, including targeting accuracy and repair efficiency. On one hand, the rational design of crRNA directly influences on-target cleavage efficiency. The design must satisfy complementarity with the target DNA sequence and conform to the downstream positioning requirement [122]. An inappropriate length of the spacer sequence or an unmodified scaffold structure often results in insufficient cleavage activity or the occurrence of off-target risks. On the other hand, the NHEJ pathway is either absent or extremely inefficient in prokaryotes. Thus, HDR becomes the primary repair mechanism [123,124]. However, the insufficient length of the donor DNA template and the lack of a high-efficiency recombination system significantly limit HDR repair efficiency. To address the above issues, future efforts should be focused on both precision design and functional enhancement in a coordinated manner. First, bioinformatics prediction combined with high-throughput screening should be applied to optimize the length of the crRNA spacer sequence, thereby improving the targeted cleavage efficiency and reducing off-target effects [125,126]. Second, the length of the donor template should be customized according to the HDR characteristics of different bacterial strains [127]. Meanwhile, recombinases such as λ-Red and RecET should be modularly integrated with the CRISPR-Cas system to construct an integrated cleavage-repair component [128,129]. This integration can enhance the enrichment of the donor template near the damaged site and further increase the probability of HDR-mediated directed repair.

In the delivery application of the CRISPR-Cas system, phage vectors confront the challenge of vector compatibility. Phage vectors have inherent limitations in their loading capacity because the spatial capacity of the phage capsid has a strict upper limit, which makes it difficult to efficiently carry various components required for the CRISPR system. This not only prevents the CRISPR-Cas system from being incorporated into the phage genome, but also facilitates the easy loss of CRISPR-Cas components. To address the aforementioned issues, a series of targeted strategies can be adopted. First, the CRISPR components are streamlined, for example, by using compact Cas proteins with smaller molecular weights or truncating non-essential sequences in the components, to shorten the total length of the components while ensuring the editing function of the system remains unaffected [130]. Second, the phage capsid proteins are engineered by genetic engineering techniques to expand the spatial capacity of the capsid, enabling it to accommodate the complete CRISPR-Cas system. This guarantees the intact delivery of components and thereby enhances the editing efficiency of the CRISPR system in host cells.

The constraints of host bacterial characteristics on editing efficiency are mainly reflected in differences in repair capacity and interference from defense mechanisms. On one hand, there are significant variations in homologous recombination (HR) capacity among different bacterial strains; for instance, some strains exhibit inherently weak HR activity, which directly limits editing outcomes. Additionally, the physiological state of the host, such as its growth cycle and metabolic activity, can affect transformation efficiency, further reducing editing success rates indirectly. On the other hand, the host defense system actively clears exogenous DNA, which further impedes the transformation process.

5. Conclusions

The phage-delivered CRISPR-Cas system, as an innovative technology in the field of microbiome engineering, provides a revolutionary solution for the precise regulation of microbial communities. By combining the accurate editing capability of the CRISPR-Cas system with the host-targeting property of phages, this technology not only overcomes the bottleneck of low delivery efficiency of traditional CRISPR-Cas systems, but also surmounts the limitation that the antibacterial effect of natural phages is easily restricted by bacterial defense mechanisms. It achieves multi-dimensional regulation, ranging from the precise elimination of specific pathogenic bacteria at the ecological level to the editing of functional genes at the genetic level, and demonstrates significant application value in scenarios such as the maintenance of gut microbiome balance and the treatment of drug-resistant bacteria.

To systematically dissect the regulatory mechanism of this technology and strengthen the connection between theory and practice, this review constructs an integrated “tool-carrier-application” framework. By systematically coupling CRISPR-Cas system subtypes with phage vector engineering strategies (integrative/non-integrative), this framework clearly illustrates the specific mechanisms by which different combination modes achieve customized regulation at both the ecological (strain elimination) and genetic (gene editing) levels. This integrative analytical approach addresses the limitation of previous studies that often explored individual components in isolation, thereby providing core theoretical support for the precise design of technical schemes. On this basis, the study further expands the coverage of technologies by incorporating cutting-edge CRISPR-based tools, including base editors, CRISPRi, and CAST systems. This expansion breaks the limitation of traditional studies that focused solely on Cas9/Cas3-mediated bactericidal effects, extending the regulatory scope to non-lethal in situ gene modification and microbiota functional remodeling. Such extensional research effectively fills the critical gap in previous studies that overlooked non-lethal regulatory modes—a mode of great significance for maintaining microbiome homeostasis.

At present, although this technology has verified its feasibility in animal models and some clinical studies, it still faces challenges, including a narrow host range, the evolution of bacterial phage resistance, and limited in-situ editing efficiency. Through strategies such as the engineering of phage receptor-binding proteins, optimization of phage bactericidal activity, and optimization of CRISPR components, these bottlenecks are being gradually addressed to clear obstacles for the clinical translation of the technology.

In the future, with the continuous iteration of gene-editing tools and the constant maturity of phage vector engineering technology, the phage-delivered CRISPR-Cas system is expected to achieve wider applications in the in-situ regulation of complex microbiomes. It will not only provide precise therapeutic solutions for diseases such as drug-resistant bacterial infections and gut microbiota dysbiosis, but also offer new technical approaches for fields including soil microbiome optimization and industrial microbial fermentation regulation. This will promote the advancement of microbiome engineering from basic research to practical applications, and provide crucial support for human health and the sustainable development of the ecological environment.

Statement of the Use of Generative AI and AI-Assisted Technologies in the Writing Process

During the preparation of this manuscript, the author(s) used DeepSeek in order to refine the English expressions and optimize linguistic accuracy. After using this tool/service, the author(s) reviewed and edited the content as needed and take(s) full responsibility for the content of the published article.

Acknowledgments

All illustrations in this study were created with the aid of the BioRender platform (©BioRender: biorender.com), and we hereby express our gratitude for its user-friendly design tools.

Author Contributions

Y.Y.: Writing—review & editing, Writing—original draft, Visualization. J.S.: Writing—original draft, Conceptualization. Z.X.: Writing—review & editing, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization.

Ethics Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China grant number [22478059].

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

-

Shi K, Xu J, Cui H, Cheng H, Liang B, Wang A. Microbiome regulation for sustainable wastewater treatment. Biotechnol. Adv. 2024, 77, 108458. doi:10.1016/j.biotechadv.2024.108458. [Google Scholar]

-

Kunath BJ, De Rudder C, Laczny CC, Letellier E, Wilmes P. The oral-gut microbiome axis in health and disease. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2024, 22, 791–805. doi:10.1038/s41579-024-01075-5. [Google Scholar]

-

Compant S, Cassan F, Kostić T, Johnson L, Brader G, Trognitz F, et al. Harnessing the plant microbiome for sustainable crop production. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2025, 23, 9–23. doi:10.1038/s41579-024-01079-1. [Google Scholar]

-

Réthi-Nagy Z, Juhász S. Microbiome’s universe: Impact on health, disease and cancer treatment. J. Biotechnol. 2024, 392, 161–179. doi:10.1016/j.jbiotec.2024.07.002. [Google Scholar]

-

Bhalodi AA, van Engelen TSR, Virk HS, Wiersinga WJ. Impact of antimicrobial therapy on the gut microbiome. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2019, 74, i6–i15. doi:10.1093/jac/dky530. [Google Scholar]

-

Luong T, Salabarria A, Roach DR. Phage therapy in the resistance era: Where do we stand and where are we going? Clin. Ther. 2020, 42, 1659–1680. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2020.07.014. [Google Scholar]

-

Carvalho JP, Moreno DS, Domingues L. Genetic engineering of Saccharomyces boulardii: Tools, strategies and advances for enhanced probiotic and therapeutic applications. Biotechnol. Adv. 2025, 84, 108663. doi:10.1016/j.biotechadv.2025.108663. [Google Scholar]

-

Kullar R, Goldstein EJC, Johnson S, Mcfarland LV. Lactobacillus bacteremia and probiotics: A review. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 896. doi:10.3390/microorganisms11040896. [Google Scholar]

-

Shigemori S, Watanabe T, Kudoh K, Ihara M, Nigar S, Yamamoto Y, et al. Oral delivery of Lactococcus lactis that secretes bioactive heme oxygenase-1 alleviates development of acute colitis in mice. Microb. Cell Fact. 2015, 14, 189. doi:10.1186/s12934-015-0378-2. [Google Scholar]

-

Danino T, Prindle A, Kwong GA, Skalak M, Li H, Allen K, et al. Programmable probiotics for detection of cancer in urine. Sci. Transl. Med. 2015, 7, 289ra84. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.aaa3519. [Google Scholar]

-

Ho CL, Tan HQ, Chua KJ, Kang A, Lim KH, Ling KL, et al. Engineered commensal microbes for diet-mediated colorectal-cancer chemoprevention. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2018, 2, 27–37. doi:10.1038/s41551-017-0181-y. [Google Scholar]

-

Vargason AM, Anselmo AC. Clinical translation of microbe-based therapies: Current clinical landscape and preclinical outlook. Bioeng. Transl. Med. 2018, 3, 124–137. doi:10.1002/btm2.10093. [Google Scholar]

-

Li T, Yang Y, Qi H, Cui W, Zhang L, Fu X, et al. CRISPR/cas9 therapeutics: Progress and prospects. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 36. doi:10.1038/s41392-023-01309-7. [Google Scholar]

-

Shen J, Lv L, Wang X, Xiu Z, Chen G. Comparative analysis of CRISPR-cas systems in Klebsiella genomes. J. Basic. Microbiol. 2017, 57, 325–336. doi:10.1002/jobm.201600589. [Google Scholar]

-

Pacesa M, Pelea O, Jinek M. Past, present, and future of CRISPR genome editing technologies. Cell. 2024, 187, 1076–1100. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2024.01.042. [Google Scholar]

-

Brophy JAN, Triassi AJ, Adams BL, Renberg RL, Stratis-Cullum DN, Grossman AD, et al. Engineered integrative and conjugative elements for efficient and inducible DNA transfer to undomesticated bacteria. Nat. Microbiol. 2018, 3, 1043–1053. doi:10.1038/s41564-018-0216-5. [Google Scholar]

-

Nath A, Bhattacharjee R, Nandi A, Sinha A, Kar S, Manoharan N, et al. Phage delivered CRISPR-cas system to combat multidrug-resistant pathogens in gut microbiome. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 151, 113122. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2022.113122. [Google Scholar]

-

Zhang S, Kim J, Ahn J. Phage engineering strategies to expand host range for controlling antibiotic-resistant pathogens. Microbiol. Res. 2025, 300, 128278. doi:10.1016/j.micres.2025.128278. [Google Scholar]

-

Schmitt DS, Siegel SD, Selle K. Applications of designer phage encoding recombinant gene payloads. Trends Biotechnol. 2024, 42, 326–338. doi:10.1016/j.tibtech.2023.09.008. [Google Scholar]

-

Bhatia S, Pooja, Yadav SK. CRISPR-cas for genome editing: Classification, mechanism, designing and applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 238, 124054. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.124054. [Google Scholar]

-

Xu Y, Le H, Wu Q, Wang N, Gong C. Advancements in CRISPR/cas systems for disease treatment. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2025, 15, 2818–2844. doi:10.1016/j.apsb.2025.05.007. [Google Scholar]

-

Zhou J, Li Z, Seun Olajide J, Wang G. CRISPR/cas-based nucleic acid detection strategies: Trends and challenges. Heliyon 2024, 10, e26179. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e26179. [Google Scholar]

-

Makarova KS, Wolf YI, Iranzo J, Shmakov SA, Alkhnbashi OS, Brouns SJJ, et al. Evolutionary classification of CRISPR-cas systems: A burst of class 2 and derived variants. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2020, 18, 67–83. doi:10.1038/s41579-019-0299-x. [Google Scholar]

-

Makarova KS, Wolf YI, Alkhnbashi OS, Costa F, Shah SA, Saunders SJ, et al. An updated evolutionary classification of CRISPR-cas systems. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2015, 13, 722–736. doi:10.1038/nrmicro3569. [Google Scholar]

-

Shmakov S, Smargon A, Scott D, Cox D, Pyzocha N, Yan W, et al. Diversity and evolution of class 2 CRISPR-cas systems. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2017, 15, 169–182. doi:10.1038/nrmicro.2016.184. [Google Scholar]

-

Shmakov S, Abudayyeh OO, Makarova KS, Wolf YI, Gootenberg JS, Semenova E, et al. Discovery and functional characterization of diverse class 2 CRISPR-cas systems. Mol. Cell. 2015, 60, 385–397. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2015.10.008. [Google Scholar]

-

Morisaka H, Yoshimi K, Okuzaki Y, Gee P, Kunihiro Y, Sonpho E, et al. CRISPR-cas3 induces broad and unidirectional genome editing in human cells. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 5302. doi:10.1038/s41467-019-13226-x. [Google Scholar]

-

Sinkunas T, Gasiunas G, Fremaux C, Barrangou R, Horvath P, Siksnys V. Cas3 is a single-stranded DNA nuclease and ATP-dependent helicase in the CRISPR/cas immune system. EMBO J. 2011, 30, 1335–1342. doi:10.1038/emboj.2011.41. [Google Scholar]

-

Huo Y, Nam KH, Ding F, Lee H, Wu L, Xiao Y, et al. Structures of CRISPR cas3 offer mechanistic insights into Cascade-activated DNA unwinding and degradation. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2014, 21, 771–777. doi:10.1038/nsmb.2875. [Google Scholar]

-

Makarova KS, Wolf YI, Koonin EV. Classification and nomenclature of CRISPR-cas systems: Where from here? CRISPR J. 2018, 1, 325–336. doi:10.1089/crispr.2018.0033. [Google Scholar]

-

Sinkunas T, Gasiunas G, Siksnys V. Cas3 nuclease—Helicase activity assays. Methods Mol. Biol. 2015, 1311, 277–291. doi:10.1007/978-1-4939-2687-9_18. [Google Scholar]

-

Mulepati S, Bailey S. Structural and biochemical analysis of nuclease domain of clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat (CRISPR)-associated protein 3 (cas3). J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 31896–31903. doi:10.1074/jbc.M111.270017. [Google Scholar]

-

Howard JAL, Delmas S, Ivančić-Baće I, Bolt EL. Helicase dissociation and annealing of RNA-DNA hybrids by Escherichia coli cas3 protein. Biochem. J. 2011, 439, 85–95. doi:10.1042/BJ20110901. [Google Scholar]

-

Cameron P, Coons MM, Klompe SE, Lied AM, Smith SC, Vidal B, et al. Harnessing type I CRISPR-cas systems for genome engineering in human cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 1471–1477. doi:10.1038/s41587-019-0310-0. [Google Scholar]

-

Selle K, Fletcher JR, Tuson H, Schmitt DS, Mcmillan L, Vridhambal GS, et al. In vivo targeting of Clostridioides difficile using phage-delivered CRISPR-cas3 antimicrobials. MBio 2020, 11, 10-1128. doi:10.1128/mBio.00019-20. [Google Scholar]

-

Jin M, Chen J, Zhao X, Hu G, Wang H, Liu Z, et al. An engineered λ phage enables enhanced and strain-specific killing of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022, 10, e0127122. doi:10.1128/spectrum.01271-22. [Google Scholar]

-

Kim P, Sanchez AM, Penke TJR, Tuson HH, Kime JC, Mckee RW, et al. Safety, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics of LBP-EC01, a CRISPR-cas3-enhanced bacteriophage cocktail, in uncomplicated urinary tract infections due to Escherichia coli (ELIMINATE): The randomised, open-label, first part of a two-part phase 2 trial. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2024, 24, 1319–1332. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(24)00424-9. [Google Scholar]

-

Jinek M, Chylinski K, Fonfara I, Hauer M, Doudna JA, Charpentier E. A programmable dual-RNA-guided DNA endonuclease in adaptive bacterial immunity. Science 2012, 337, 816–821. doi:10.1126/science.1225829. [Google Scholar]

-

Mojica FJM, Díez-Villaseñor C, García-Martínez J, Almendros C. Short motif sequences determine the targets of the prokaryotic CRISPR defence system. Microbiology 2009, 155, 733–740. doi:10.1099/mic.0.023960-0. [Google Scholar]

-

Haider S, Mussolino C. Fine-tuning homology-directed repair (HDR) for precision genome editing: Current strategies and future directions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 4067. doi:10.3390/ijms26094067. [Google Scholar]

-

Canny MD, Moatti N, Wan LCK, Fradet-Turcotte A, Krasner D, Mateos-Gomez PA, et al. Inhibition of 53BP1 favors homology-dependent DNA repair and increases CRISPR-cas9 genome-editing efficiency. Nat. Biotechnol. 2017, 36, 95–102. doi:10.1038/nbt.4021. [Google Scholar]

-

Lam KN, Spanogiannopoulos P, Soto-Perez P, Alexander M, Nalley MJ, Bisanz JE, et al. Phage-delivered CRISPR-cas9 for strain-specific depletion and genomic deletions in the gut microbiome. Cell Rep. 2021, 37, 109930. doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2021.109930. [Google Scholar]

-

Cobb LH, Park J, Swanson EA, Beard MC, Mccabe EM, Rourke AS, et al. CRISPR-cas9 modified bacteriophage for treatment of Staphylococcus aureus induced osteomyelitis and soft tissue infection. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0220421. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0220421. [Google Scholar]

-

Fa-Arun J, Huan YW, Darmon E, Wang B. Tail-engineered phage P2 enables delivery of antimicrobials into multiple gut pathogens. ACS Synth. Biol. 2023, 12, 596–607. doi:10.1021/acssynbio.2c00615. [Google Scholar]

-

Abudayyeh OO, Gootenberg JS, Konermann S, Joung J, Slaymaker IM, Cox DBT, et al. C2c2 is a single-component programmable RNA-guided RNA-targeting CRISPR effector. Science 2016, 353, aaf5573. doi:10.1126/science.aaf5573. [Google Scholar]

-

Mahas A, Neal Stewart CJ, Mahfouz MM. Harnessing CRISPR/cas systems for programmable transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulation. Biotechnol. Adv. 2018, 36, 295–310. doi:10.1016/j.biotechadv.2017.11.008. [Google Scholar]

-

Basit A, Liu A, Zheng W, Zhu J. A review on the mechanism and potential diagnostic application of CRISPR/cas13a system. Mamm. Genome 2025, 36, 709–726. doi:10.1007/s00335-025-10143-x. [Google Scholar]

-

East-Seletsky A, O’Connell MR, Knight SC, Burstein D, Cate JHD, Tjian R, et al. Two distinct RNase activities of CRISPR-C2c2 enable guide-RNA processing and RNA detection. Nature 2016, 538, 270–273. doi:10.1038/nature19802. [Google Scholar]

-

Tang Y, Fu Y. Class 2 CRISPR/cas: An expanding biotechnology toolbox for and beyond genome editing. Cell Biosci. 2018, 8, 59. doi:10.1186/s13578-018-0255-x. [Google Scholar]

-

Liu L, Li X, Ma J, Li Z, You L, Wang J, et al. The molecular architecture for RNA-guided RNA cleavage by cas13a. Cell 2017, 170, 714–726.e10. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2017.06.050. [Google Scholar]

-

Bot JF, van der Oost J, Geijsen N. The double life of CRISPR-cas13. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2022, 78, 102789. doi:10.1016/j.copbio.2022.102789. [Google Scholar]

-

Kiga K, Tan X, Ibarra-Chávez R, Watanabe S, Aiba Y, Sato’o Y, et al. Development of CRISPR-cas13a-based antimicrobials capable of sequence-specific killing of target bacteria. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 2934. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-16731-6. [Google Scholar]

-

Hryhorowicz M, Lipiński D, Zeyland J. Evolution of CRISPR/cas systems for precise genome editing. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 14233. doi:10.3390/ijms241814233. [Google Scholar]

-

Li X, Wang Y, Liu Y, Yang B, Wang X, Wei J, et al. Base editing with a cpf1-cytidine deaminase fusion. Nat. Biotechnol. 2018, 36, 324–327. doi:10.1038/nbt.4102. [Google Scholar]

-

Danner E, Bashir S, Yumlu S, Wurst W, Wefers B, Kühn R. Control of gene editing by manipulation of DNA repair mechanisms. Mamm. Genome 2017, 28, 262–274. doi:10.1007/s00335-017-9688-5. [Google Scholar]

-

Kurt IC, Zhou R, Iyer S, Garcia SP, Miller BR, Langner LM, et al. CRISPR c-to-g base editors for inducing targeted DNA transversions in human cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 2021, 39, 41–46. doi:10.1038/s41587-020-0609-x. [Google Scholar]

-

Komor AC, Kim YB, Packer MS, Zuris JA, Liu DR. Programmable editing of a target base in genomic DNA without double-stranded DNA cleavage. Nature 2016, 533, 420–424. doi:10.1038/nature17946. [Google Scholar]

-

Cox DBT, Gootenberg JS, Abudayyeh OO, Franklin B, Kellner MJ, Joung J, et al. RNA editing with CRISPR-cas13. Science 2017, 358, 1019–1027. doi:10.1126/science.aaq0180. [Google Scholar]

-

Gaudelli NM, Komor AC, Rees HA, Packer MS, Badran AH, Bryson DI, et al. Programmable base editing of a•t to g•c in genomic DNA without DNA cleavage. Nature 2017, 551, 464–471. doi:10.1038/nature24644. [Google Scholar]

-

Nethery MA, Hidalgo-Cantabrana C, Roberts A, Barrangou R. CRISPR-based engineering of phages for in situ bacterial base editing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2206744119. doi:10.1073/pnas.2206744119. [Google Scholar]

-

Brödel AK, Charpenay LH, Galtier M, Fuche FJ, Terrasse R, Poquet C, et al. In situ targeted base editing of bacteria in the mouse gut. Nature 2024, 632, 877–884. doi:10.1038/s41586-024-07681-w. [Google Scholar]

-

Larson MH, Gilbert LA, Wang X, Lim WA, Weissman JS, Qi LS. CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) for sequence-specific control of gene expression. Nat. Protoc. 2013, 8, 2180–2196. doi:10.1038/nprot.2013.132. [Google Scholar]

-

Sun L, Zheng P, Sun J, Wendisch VF, Wang Y. Genome-scale CRISPRi screening: A powerful tool in engineering microbiology. Eng. Microbiol. 2023, 3, 100089. doi:10.1016/j.engmic.2023.100089. [Google Scholar]

-

Alexander NG, Cutts WD, Hooven TA, Kim BJ. Transcription modulation of pathogenic streptococcal and enterococcal species using CRISPRi technology. PLoS Pathog. 2024, 20, e1012520. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1012520. [Google Scholar]

-

Bendixen L, Jensen TI, Bak RO. CRISPR-cas-mediated transcriptional modulation: The therapeutic promises of CRISPRa and CRISPRi. Mol. Ther. 2023, 31, 1920–1937. doi:10.1016/j.ymthe.2023.03.024. [Google Scholar]

-

Zhu X, Luo H, Yu X, Lv H, Su L, Zhang K, et al. Genome-wide CRISPRi screening of key genes for recombinant protein expression in Bacillus subtilis. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, e2404313. doi:10.1002/advs.202404313. [Google Scholar]

-

Zheng H, Mao C, Chen S, Hou S, Sun D. A quorum sensing-controlled type I CRISPRi toolkit for dynamically regulating metabolic flux. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, gkaf693. doi:10.1093/nar/gkaf693. [Google Scholar]

-

Hsu BB, Plant IN, Lyon L, Anastassacos FM, Way JC, Silver PA. In situ reprogramming of gut bacteria by oral delivery. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 5030. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-18614-2. [Google Scholar]

-

Gelsinger DR, Vo PLH, Klompe SE, Ronda C, Wang HH, Sternberg SH. Bacterial genome engineering using CRISPR-associated transposases. Nat. Protoc. 2024, 19, 752–790. doi:10.1038/s41596-023-00927-3. [Google Scholar]

-