Advances in the Biosynthesis and Application of Sialyllactose

Received: 31 October 2025 Revised: 12 November 2025 Accepted: 01 December 2025 Published: 08 December 2025

© 2025 The authors. This is an open access article under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

1. Introduction

Human milk consists of essential nutrients (such as lactose and protein) and other substances [1,2,3,4,5]. Human milk oligosaccharides (HMOs) are a unique class of oligosaccharides found especially in human milk. They rank third in abundance among human milk’s solid components, surpassed only by lactose and fat. Since the 1930s, HMOs have been recognized as the most important prebiotic substance in human milk, playing a crucial role in infant gut microbiota colonization, immune system development, and infection resistance [6]. HMOs act as soluble decoy receptors that mimic host epithelial cell surface glycans, effectively blocking the adhesion of various pathogens (such as Campylobacter jejuni, Salmonella) and viruses (such as norovirus) to the intestinal mucosa [7]. This reduces the risk of gastrointestinal, genitourinary, and respiratory infections caused by pathogens, and even prevents mother-to-child transmission of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15]. Additionally, infant formula enriched with HMOs has functions such as mimicking human milk components and promoting brain development, making it a more critical and essential component widely used in infant formula [16] (Figure 1).

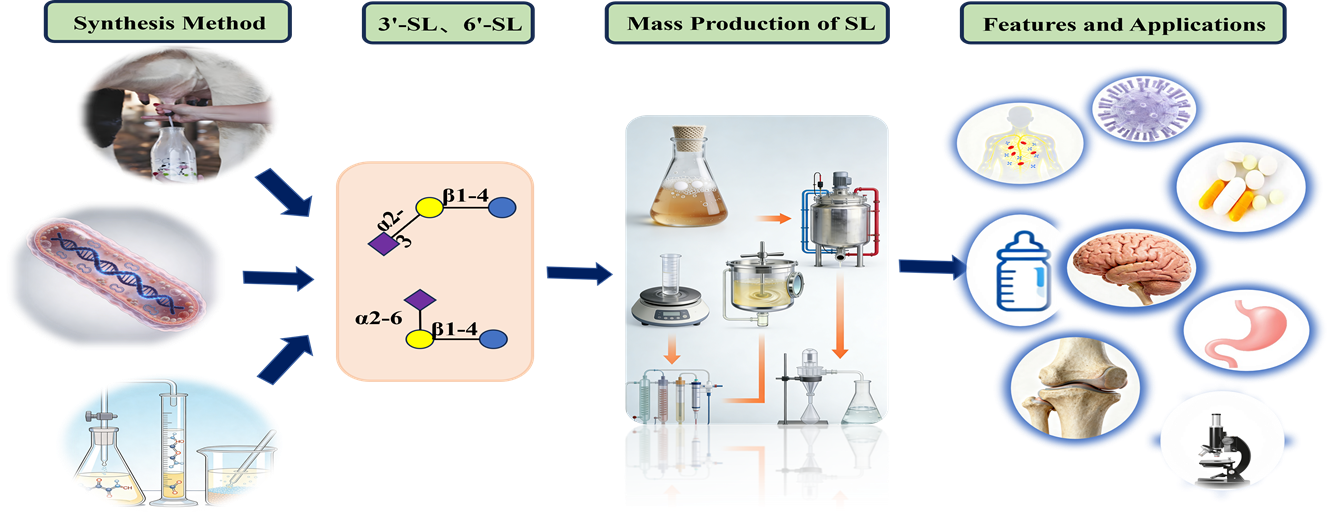

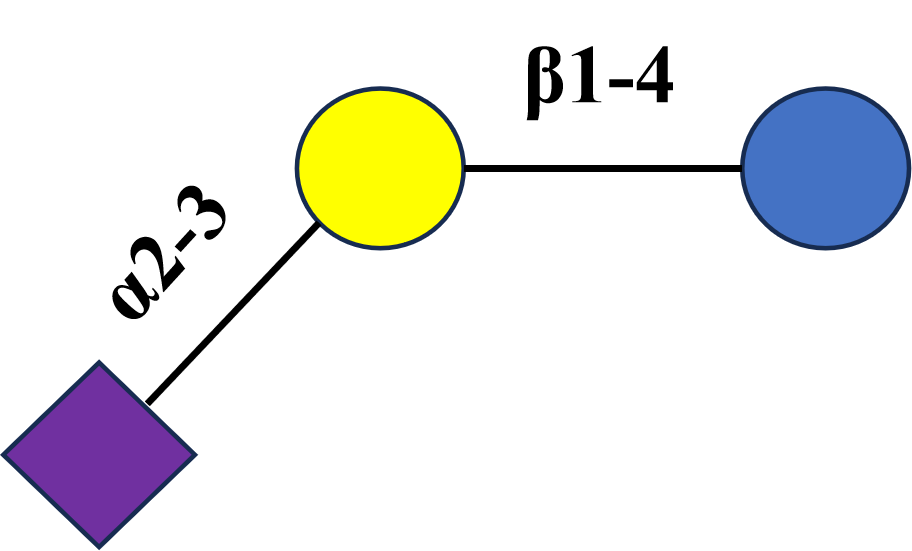

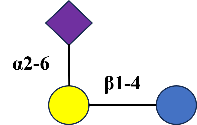

To date, over 200 structurally diverse HMOs have been identified [17]. These molecules are typically composed of five monosaccharides—glucose, galactose, sialic acid, L-fucose, and N-acetylglucosamine—linked in various combinations. They are primarily classified into three categories: fucosylated oligosaccharides, nonfucosylated neutral oligosaccharides, and sialylated HMOs (SHMOs). SHMOs, as an important component of HMOs, are acidic glycans characterized by the attachment of sialic acid (primarily N-acetylneuraminic acid, Neu5Ac) via α,2-3 or α,2-6 linkages to the lactose core (Galβ1-4Glc) or extended core structures like lacto-N-tetraose (LNT) and lacto-N-neotetraose (LNnT) [18]. The relatively simple structures are 3′-SL and 6′-SL, which are connected to lactose by α,2-6 and α,2-3 glycosidic bonds, respectively. SL exhibits distinct structural and functional characteristics compared to neutral HMOs (such as 2′-FL, 3′-FL, and LNnT) approved for use in infant formula and infant foods. With its unique sialic acid structure, SL demonstrates significant advantages in promoting infant neurocognitive development. Research confirms its ability to directly promote sialic acid deposition in brain tissue and upregulate gene expression related to learning and memory in the hippocampus. Such as cell-free culture with 3′-SL could reduce virulence gene expression in Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium [19]. 6′-SL can cross the blood-brain barrier to support synapse formation, playing a crucial role in cognitive development, including memory and learning [20,21].

Compared to other SHMOs, 3′-SL and 6′-SL feature simpler structures, are easier to synthesize, and exhibit relatively high abundance in human milk. In recent years, SL has become a focal point of research at the intersection of glycobiology and nutrition. Currently, SL has been commercialized for application. Such as Similac 360 Total Care, Nestle Beba (BEBA), and Illuma Future 10HMOs have incorporated multiple components, including 6′-SL and 3′-SL into their formulations. Nestlé NAN SensiPro is a deeply hydrolyzed protein formula powder enriched with HMOs, designed to reduce the risk of milk protein allergy while preventing diarrhea. SL has achieved a mature application in infant and toddler nutrition, encompassing both standard formulas and formulas for special medical purposes. In sectors such as adult health foods, functional food and beverages, and pet nutrition, it remains largely in the market exploration and preliminary application stages. It is recognized as a future development direction. However, the supply of natural human milk is limited and cannot meet the needs of all infants and young children, let alone those of adults and other sectors. Therefore, how to efficiently and sustainably synthesize SL to meet growing market demand has become an urgent issue for researchers to address. This article provides an overview of the synthesis and application of SL and discusses the challenges and future directions in its synthesis.

2. Classification and Function of SHMOs

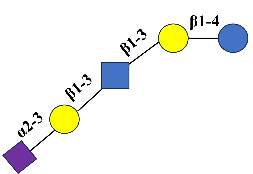

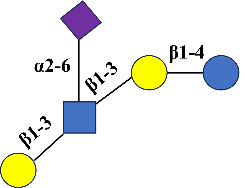

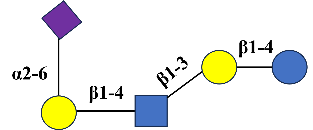

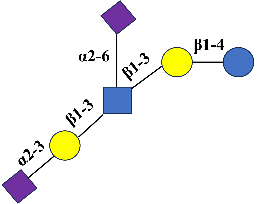

Neu5Ac can be attached to the core structure of HMOs via α,2-3 or α,2-6 glycosidic bonds (Figure 2). These oligosaccharides, known as SHMOs, are primarily classified into two major series: Neu5Ac modified lactose and structurally more complex sialic acid-modified lactose-N-tetrasaccharides. Neu5Ac modified lactose is SL. SL is the most fundamental and common type of SHMOs, consisting of a single Neu5Ac molecule attached to the core structure of lactose. The structure of SL is formed by three glycosidic bonds, with the non-reducing end of its lactose residue linked to a single Neu5Ac residue via an α,2-3 or α,2-6 bond. It primarily exists in two isomeric forms: 3′-SL and 6′-SL [22]. These oligosaccharides play a unique role in infant neurological development, immune defense, and gut microbiota regulation [23]. In recent years, this has become a research focus at the intersection of glycobiology and nutrition. The core structure of Neu5Ac modified lactose-N-tetrasaccharides is lactose-N-tetrasaccharide, with Neu5Ac attached at different positions. Among these, LNT can undergo further salicylate modification at different sites, forming a series of salicylate derivatives such as LSTa, LSTb, and DSLNT. However, LNnT derivatives can form LSTc, LSTd, and DSLNnT through salivary acidification (Table 1). SHMOs possess multiple health-promoting effects for infants, including anti-adhesion and antibacterial capabilities, regulation of intestinal epithelial cell responses, and promotion of brain development [24].

Table 1. Below are examples of SHMOs, along with their molecular formulas, glycosidic bond linkage, structures, and countries approved for use as food safety ingredients.

|

Abbreviation |

Full Name |

Molecular Formula |

Glycosidic Bond Linkage |

Structure |

Approved Country |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

3′-SL |

3′-Sialyllactose |

C23H39NO19 |

Neu5Acα2-3 Gal β1-4 Glc |

|

US (2018) EU (2021) |

|

6′-SL |

6′-Sialyllactose |

C23H38NNaO19 |

Neu5Acα2-6 Galβ1-4Glc |

|

US (2020) EU (2021) |

|

LSTa |

Sialyllacto-N-tetraose a |

C37H61N2O29Na |

Neu5Acα2-3Galβ1-3GlcNAcβ1-3Galβ1-4Glc |

|

None |

|

LSTb |

Sialyllacto-N-tetraose b |

C37H62N2O29 |

Neu5Acα2-6 [Galβ1-3] GlcNAcβ1-3Galβ1-4Glc |

|

None |

|

LSTc |

Sialyllacto-N-tetraose c |

C37H62N2O29 |

α-Neu5Ac-(2→6)-β-d-Gal-(1→4)-β-d-GlcNAc-(1→3)-β-d-Gal-(1→4)-d-Glc |

|

None |

|

LSTd |

Sialyllacto-N-tetraose d |

C37H62N2O29 |

α-Neu5Ac-(2→3)-β-d-Gal-(1→4)-β-d-GlcNAc-(1→3)-β-d-Gal-(1→4)-d-Glc |

|

None |

|

DSLNT |

Disialyllacto-N-tetraose |

C48H79N3O37 |

α-Neu5Ac-(2→3)-β-Gal-(1→3)- [α-Neu5Ac-(2→6)]-β-GlcNAc-(1→3)-β-Gal-(1→4)-Glc |

|

None |

3. SL Synthesis

SL primarily consists of 3′-SL and 6′-SL, representing one of the most significant acidic core members among HMOs. Due to its immense commercial value and health benefits, developing efficient and economical SL synthesis methods has become a research hotspot.

3.1. Direct Extraction Methods

Currently, the primary naturally occurring sources of SL are mammalian milk, such as human, cow’s, and goat’s milk, as well as other substances. Direct extraction of SL from natural sources remains the fundamental method for obtaining these valuable HMOs. Human milk itself is the natural source of SL and other HMOs. The concentration of sialylated oligosaccharides, including SL, is highest in colostrum [25]. However, extracting SL directly from human milk is not feasible for large-scale applications due to obvious limitations in availability, ethical considerations, and high cost. Similarly, animal milks generally contain much lower concentrations and different profiles of sialylated oligosaccharides than human milk, making them unattractive for efficient SL extraction [26].

Therefore, the primary source for direct extraction is whey, a byproduct of cheese production [27]. Whey contains a complex mixture of lactose, proteins, minerals, and various oligosaccharides, including SL, particularly the 3′-SL isomer. The extraction includes the following steps: Ultrafiltration (UF) is first used to remove proteins from whey, producing a permeate rich in lactose and oligosaccharides. A multi-step ion-exchange resin process then demineralizes the permeate and selectively captures SL. The adsorbed SL is finally eluted, enabling valorization of whey by recovering valuable oligosaccharides from dairy waste. According to the technology of Beijing Sanyuan Foods Co., Ltd., through processes such as ultrafiltration, nanofiltration, chromatographic separation, and desalination, the oligosaccharide lyophilized powder obtained from whey liquid can achieve a total content of over 40% for 3′-SL and 6′-SL combined. However, the concentration of SL in whey is relatively low, making the purification process complex and potentially costly for obtaining high purity SL on a large scale. Generally, the direct extraction method is not used to obtain SL.

3.2. Chemical Synthesis Method

The difficulty of isolating sufficient amounts of SL from natural sources has prompted the development of corresponding chemical synthesis methods. Chemical synthesis was the earliest approach attempted, involving the chemical bonding of protected Neu5Ac donors to lactose acceptors through complex chemical reaction steps, followed by the removal of protecting groups to yield the target product. Including the following steps: Sialic acid’s reactive groups (COOH, OH) are protected, while lactose is selectively protected to expose only one specific hydroxyl. Glycosylation: The activated Neu5Ac donor couples with the protected lactose using promoters to form the α-glycosidic bond under anhydrous conditions. Deprotection: All protective groups are removed, and the final SL is purified via chromatography. The chemical-enzymatic method, which combines chemical construction of complex oligosaccharide backbones with enzymatic addition of terminal sialic acid groups, has been developed to enhance synthetic efficiency. Recent advances, including the application of protecting group strategies and novel glycosyl donors, have significantly improved stereoselectivity and yield. This progress enables efficient construction of complex sialylated structures essential for biochemical and immunological studies.

3.3. Synthetic Biology Strategies and Methods for SL Synthesis

3.3.1. Enzyme Catalyzed Synthesis

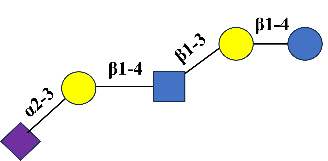

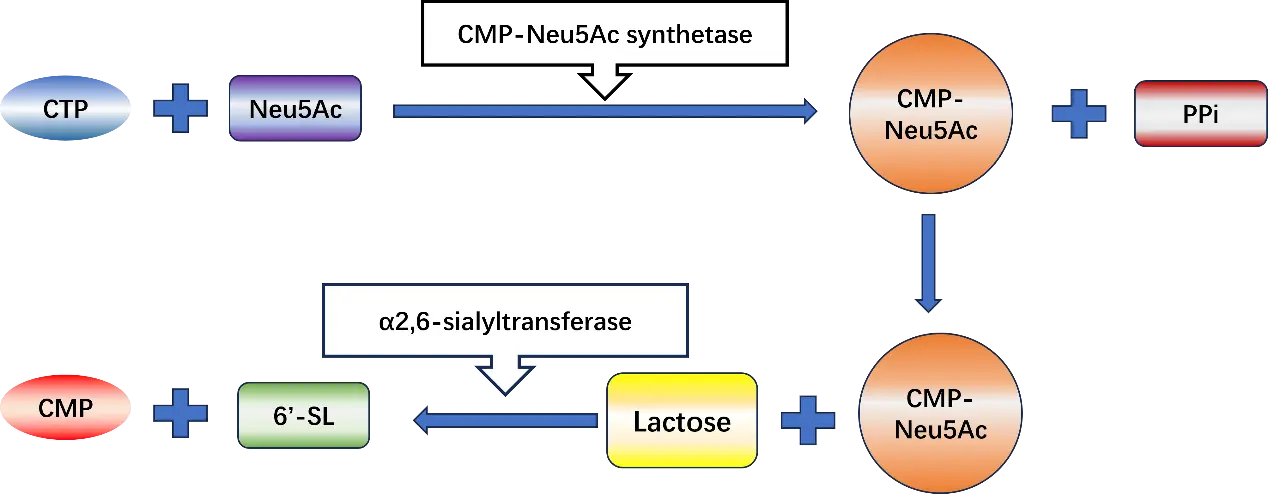

The core mechanism of SL enzyme synthesis relies on the synergistic action of CMP-Neu5Ac synthase and sialyltransferase (SiaT) [28]. CMP-Neu5Ac synthase catalyzes the combination of Neu5Ac with CTP to produce CMP-Neu5Ac. Subsequently, under the catalysis of SiaT, CMP-Neu5Ac is synthesized into SL (Figure 3) [29].

Figure 3. Two step synthesis of salivary lactose. Compound abbreviations: CTP: cytidine triphosphate; Neu5AC: sialic acid; CMP-NeuAc: cytidine monophosphate-N-acetylneuraminic acid; CMP: cytidine monophosphate; 6′-SL: 6′-Sialyllactose; PPi: pyrophosphate.

Cytidine Monophosphate-N-acetylneuraminic Acid Synthetase (NeuA)

NeuA serves as the “activation switch” in the SL enzyme synthesis pathway. It is responsible for converting free Neu5Ac molecules into high-energy neuraminide, providing the essential substrate for the final assembly of sugar chains. NeuA acts as the molecular hub and bridge connecting the synthesis of free Neu5Ac with its utilization (glycosylation). It plays a pivotal role in this pathway by linking these two processes [30]. In many enzyme systems, the expression level of neuA directly influences the synthesis rate of CMP-Neu5Ac, thereby controlling the speed and extent of the entire sialylation process. Consequently, it is considered a key rate-limiting enzyme. In summary, neuA serves as an indispensable “activation switch” in Neu5Ac enzyme synthesis, converting inert Neu5Ac molecules into a high-energy, usable form. Providing precursors for SL synthesis is one of the critical steps determining whether SL can be synthesized.

Sialyltransferase (SiaT)

SiaT are primarily classified into four major types based on the glycosidic linkage they catalyze (Table 2): the ST3Gal enzyme family exhibits strict α2-3 linkage regio-selectivity, specifically transferring sialic acid to galactose acceptors. Their catalytic efficiency varies significantly among different isoforms and is highly dependent on the acceptor substrate structure, though they generally demonstrate higher efficiency towards simple substrates like lactose. However, their native forms often possess limited stability for in vitro applications. The ST6Gal family specifically catalyzes the formation of α2-6 galactose linkages and also shows high catalytic efficiency towards lactose. Certain engineered bacterial ST6Gal enzymes have been widely adopted in industrial biosynthesis due to their improved stability, whereas mammalian ST6Gals generally remain challenging to stabilize. The ST6GalNAc family also generates α2-6 linkages but demonstrates distinct substrate specificity for N-acetylgalactosamine, particularly acting on mucin-type O-glycans. Its catalytic efficiency is highly dependent on the acceptor structure, and its stability profile is similar to that of ST6Gal. The ST8Sia family catalyzes α2-8 sialic acid linkages to form polysialic acid chains with strict regio-selectivity. However, as this process involves sequential polymerization of multiple sialic acid residues, its catalytic efficiency is typically lower than that of monosialyltransferases. These enzymes are derived from mammalian sources, which exhibit high substrate specificity but pose challenges for recombinant expression, and from microbial sources, which are more amenable to industrial biocatalytic applications due to their efficient heterologous production. SiaT belongs to the Glycosyltransferases (GTs) family and catalyzes the transfer of Neu5Ac from the activated donor substrate CMP-Neu5Ac to the receptor on the terminal sugar chain of specific glycoproteins or glycolipids. This process is a key step in the synthesis of SL. Katharina et al. found that his85, the active site of Pasteurella sialyltransferase, can promote productive SA transfer, thereby preventing the ineffective hydrolysis of CMP-Neu5Ac [31]. Cao Hongzhi et al. overcame the regional selectivity limitations of α2-6 sialyltransferase by developing an innovative “substrate engineering” strategy. This approach guides enzymatic specificity through pre-modification of sugar receptor molecules, enabling site-specific sialylation of complex polysaccharide chains [32]. Anne S Meyer et al. used the engineered sialidase Tr15 from Trypanosoma rangeli to synthesize 3′-SL directly in cow’s milk. This transsialylation reaction, using κ-casein glycomacropeptide (cGMP) as a donor at 5 °C, yielded 1160 mg/L within 10 min [33]. Guo et al. developed an enzymatic synthesis process utilizing Bacteroides fragilis-derived exo-α-sialidase, achieving efficient production of purity 6′-SL via α2-6 specific transglycosylation that transfers sialyl oligosaccharides to lactose, with a conversion rate of 18.2% and a yield of 1520 mg/L, where its regioselectivity provides critical advantages for large-scale manufacturing [34]. Therefore, we can optimize the catalytic efficiency and substrate specificity of SiaT through directed evolution and rational design. Traditional enzymatic methods face economic constraints due to the high cost of substrates, making them unsuitable for large-scale commercial production. Therefore, microbial synthesis of SL has become particularly important.

Table 2. Below are examples of SiaT, including their catalytic bond type, primary subtypes, primary substrate preference, and function.

|

Enzyme Name |

Catalytic Bond Type |

Primary Subtypes |

Primary Substrate Preference |

Function |

References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

α2-3 Sialyltransferase |

α2-3glycosidic bond |

ST3GAL1 |

Preference for the Galβ1-3GalNAc structure (T antigen) on O-linked glycan chains. |

The acidification modifications it mediates in saliva can influence cancer cells’ immune evasion and metastatic potential. |

[35] |

|

ST3GAL2 |

Preference for the Galβ1-3GalNAc structure (T antigen) on O-linked glycan chains. |

Synergizes with ST3GAL1 to maintain melanoma, and its knockdown significantly inhibits tumor growth and induces apoptosis. |

[36] |

||

|

ST3GAL3 |

Preference for Galβ1-4GlcNAc structures on N-linked glycans (type II glycans). |

By generating structures such as sialyl-Lewis X (sLeX), it enhances adhesion between tumor cells and endothelial cells, thereby promoting cancer metastasis. |

|||

|

ST3GAL4 |

Preferential action on Galβ1-3GalNAc (O-linked) structures. |

Acidification of Siglec ligands via saliva contributes to tumor immune evasion. |

[37] |

||

|

ST3GAL5 |

Specificity toward lactosylceramide (LacCer) as a substrate. |

Catalyzes the synthesis of important gangliosides, serving as a key enzyme in ganglioside biosynthesis. |

[38] |

||

|

ST3GAL6 |

this enzyme exhibited restricted substrate specificity, i.e., it utilized Galbeta1,4GlcNAc on glycoproteins, and neolactotetraosylceramide and neolactohexaosylceramide. |

ST3GAL6 participates in the α2-3 sialylation of various glycosylated compounds, and its abnormal expression is associated with the progression of certain cancers. |

[39] |

||

|

α2-6 Sialyltransferase |

α2-6 glycosidic bond |

ST6GAL Family |

Preference for transferring sialic acid to N-linked glycan chains. |

ST6GAL promotes resistance to chemoradiotherapy by inhibiting apoptosis in rectal cancer cell lines. |

|

|

ST6 N-Acetylgalactosamine Sialyltransferase |

α2-6 glycosidic bond |

ST6GALNAC1 |

Primarily active against Tn antigen (GalNAc α-Ser/Thr), T antigen (Gal β1-3GalNAc α-Ser/Thr), and ST antigen (Neu5Acα2-3 Gal β1-3GalNAc α-Ser/Thr). |

ST6GALNAC1 enhances cell adhesion or migration by catalyzing sTn modification of CD44 protein, thereby promoting endometrial-embryo interactions during embryo implantation. In breast cancer, it drives tumor metastasis by inducing the EMT pathway. |

|

|

ST6GALNAC2 |

Primarily active against the T antigen (Gal β1-3GalNAc α-Ser/Thr). |

ST6GALNAC2 is associated with IgA nephropathy risk, suppressed by miRNA to promote invasion in colorectal cancer, and highly expressed in breast cancer where it inhibits metastasis and improves prognosis via O-glycosylation. |

|||

|

ST6GALNAC3 |

Capable of catalyzing α2-6 sialylation of GM1b ganglioside and O-glycan ST. |

ST6GALNAC3 can act as an lncRNA to inhibit skin fibroblast proliferation and migration, and also function as an enzyme involved in the synthesis of the bis-sialic acid-T structure, which maintains vascular integrity. |

|||

|

ST6GALNAC4 |

Substrates with an α2-3 sialic acid structure are preferred, particularly ST antigen (Neu5 Acα2-3 Gal β1-3GlcNAc). |

ST6GALNAC4 promotes tumor proliferation, migration, and immune suppression in hepatocellular carcinoma by inducing abnormal glycosylation of TGFBR2, thereby activating the TGF-β pathway. Concurrently, it synergizes with ST6GALNAC3 to synthesize bis-sialic acid T antigen, maintaining lymph node vascular endothelial integrity; its absence can lead to hemorrhage. |

|||

|

ST6GALNAC5 |

It exhibits broad substrate specificity and can recognize multiple HMO substrates, including those with the Neu5Acα2-3 Gal β1-3Glc NAc structure. |

ST6GALNAC5 inhibits breast cancer cell-BBB interactions, its mutations cause CAD, and promote prostate cancer invasion/metastasis via GATA2 upregulation. |

|||

|

ST6GALNAC6 |

Possesses the broadest substrate specificity, efficiently recognizing and catalyzing a wide range of HMO substrates, including those with branched structures. |

ST6GALNAC6 suppresses bladder cancer via circRNA-mediated ferroptosis promotion, drives gastric cancer stemness, and loses immunosuppressive function in early colon cancer through epigenetic silencing. |

|||

|

α-2,8-Sialyltransferase |

α-2,8-glycosidic bond |

ST8Sia Family |

Preferentially uses CMP-sialic acid (CMP-Neu5Ac) as the donor substrate for sialic acid. |

ST8Sia is involved in neurobiological processes such as brain development, regulates ganglioside biosynthesis, and mediates multidrug resistance in cancer. |

3.3.2. Microbial Synthesis Method

SL Synthesis Pathway

Compared to the method of extracting enzymes involved in oligosaccharide synthesis from microbial cells and adding them to a reaction system, the microbial synthesis approach utilizes endogenous or genetically engineered enzymes within the microbial cell for oligosaccharide production. This method employs glycosyltransferases for in vivo synthesis, eliminating the need for enzyme purification, and allows for the intracellular generation of sugar-nucleotide donors via cellular metabolism, thereby significantly reducing production costs. Enzymatic synthesis is cost-prohibitive and is only suitable for small-batch production on a laboratory scale, making it unsuitable for large-scale industrial applications. Therefore, it becomes particularly important to engineer chassis microorganisms by introducing key enzymes to directly produce SL through fermentation using low-cost carbon sources. This process relies primarily on two key enzymes: Neu5Ac synthase activates the Neu5Ac precursor (CMP-Neu5Ac), while SiaT precisely transfers it onto lactose to form SL. Through metabolic engineering to enhance precursor supply and inhibit side reactions, combined with fermentation process optimization, efficient and green biomanufacturing of SL was ultimately achieved.

Strategies for Constructing Metabolic Engineering Strains to Synthesize SL

Based on the substrate source, the biosynthesis pathways of SL can be divided into the de novo synthesis pathway and the salvage pathway. The de novo pathway synthesizes Neu5Ac using low-cost carbon sources, such as glycerol, and then utilizes Neu5Ac as a precursor to produce SL. Currently, the de novo approach is predominantly adopted for SL synthesis to reduce production costs. Zhu M et al. established a de novo synthetic pathway for 6′-SL based on N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc), utilizing glycerol as the carbon source. Ultimately, heterologous expression achieved a yield of 14.33 g/L of 6′-SL in a 3L fermenter [63]. PRIEM B et al. discovered a method in E. coli that utilizes its endogenous metabolic pathway to generate CMP-Neu5Ac through a cascade reaction starting from UDP-GlcNAc. In a fermentation culture with sequential addition of glycerol and lactose, the final titer of 3′-SL reached 25.5 g/L [64]. As a key precursor in the de novo synthesis pathway, efficient methods for the direct synthesis of Neu5Ac are equally important. Using GlcNAc as the substrate, ManNAc is synthesized through the catalytic action of the ce-3 enzyme. Subsequently, ManNAc can be converted into Neu5Ac under the catalysis of the neuB enzyme. Lee et al. achieved ATP regeneration in a whole-cell system using GlcNAc as substrate. By optimizing the ratio of two catalytic cells, they ultimately realized efficient Neu5Ac production with a maximum yield of 10.2 g Neu5Ac/L·h and a glucuronic acid conversion rate of 33.3%. Recombinant E. coli cells demonstrated reusability for over eight cycles while maintaining yields exceeding 8.0 g Neu5Ac/L·h. [65]. Lin et al. successfully developed a highly efficient whole-cell catalytic system to enhance Neu5Ac yield. By employing heterologous expression, they achieved a maximum Neu5Ac titer of 240 mM (74.2 g/L), a productivity of 6.2 g Neu5Ac/L·h, and a GlcNAc conversion rate of 40%. The engineered strain could be reused for at least five cycles with a productivity of >6 g/L/h [66]. Accumulated a large amount of precursor substances for SL synthesis.

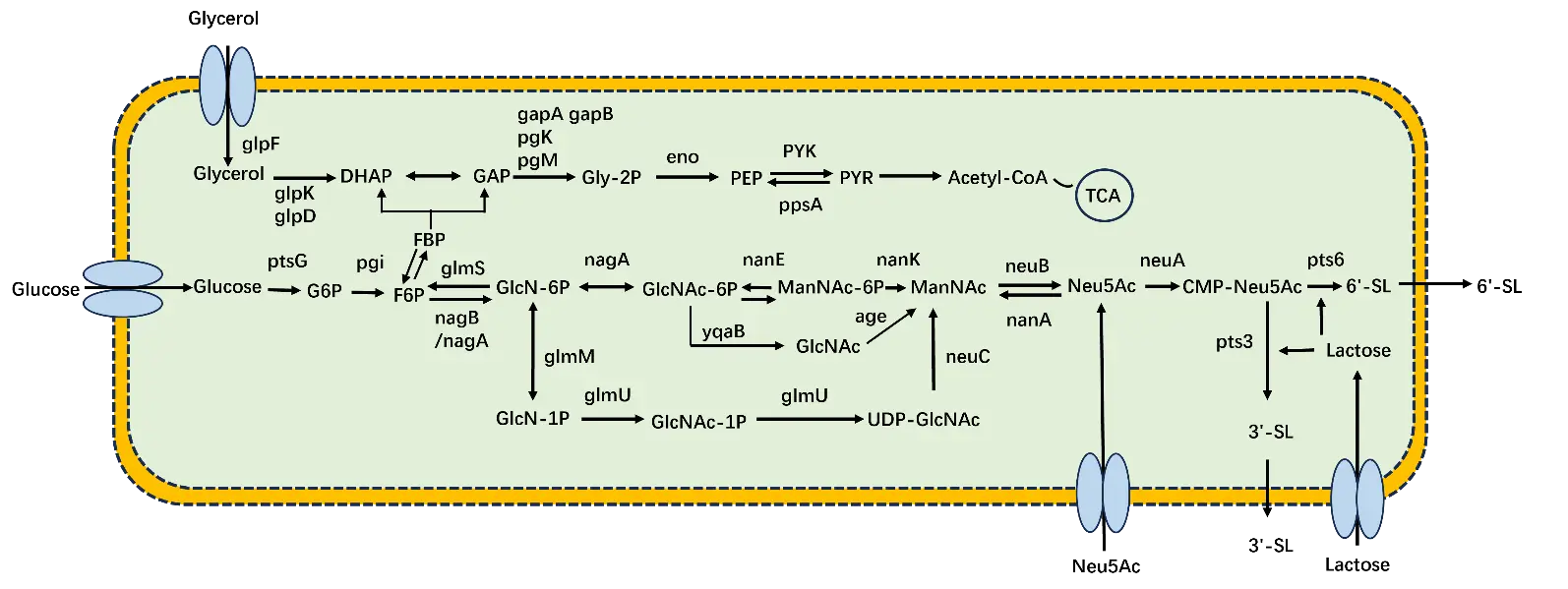

The salvage pathway directly synthesizes SL using Neu5Ac as the substrate. Neu5Ac is synthesized into CMP-Neu5Ac by the action of the neuA enzyme, and subsequently, CMP-Neu5Ac is ultimately synthesized into SL by the action of the pst3 enzyme. Endo et al. constructed recombinant E. coli and Corynebacterium ammoniagenes for coupled bacterial fermentation; they overexpressed genes encoding CMP-Neu5Ac synthase, CTP synthase, and α2-3 sialyltransferase, adding substrates such as Neu5Ac and lactose in a 5 L fermenter. Ultimately, the yield of 3′-SL synthesized through heterologous expression reached 33 g/L [67]. However, this salvage pathway utilizes Neu5Ac as the substrate, which is relatively expensive compared to low-cost carbon sources, leading to higher production costs for SL. The most critical consideration in SL synthesis is the production cost, wherein substrate optimization is a key factor in microbial fermentation methods. Therefore, de novo synthetic pathways are preferred over the salvage pathway for constructing metabolic engineering strains for SL production. Although significant progress has been made in the biosynthesis of SL using E. coli, numerous challenges remain for achieving efficient industrial-scale production. One major limiting factor in microbial fermentation is the low conversion rate of the key precursor, Neu5Ac. To address this, different Neu5Ac synthesis pathways can be engineered, and the synthesis efficiency of SL can be enhanced by modulating factors such as strain selection, competing pathways, cofactors, and transport proteins (Figure 4).

Based on current research progress, the core strategies for constructing highly efficient SL synthetic strains can be summarized. Prioritizing de novo synthesis pathways driven by low-cost carbon sources and maximizing industrial feasibility are achieved through systematic engineering approaches that enhance Neu5Ac precursor supply, block metabolic diversion pathways, optimize cofactor balance, and improve substrate transport efficiency. Future breakthroughs could focus on enhancing precursor synthesis flux—such as developing multi-enzyme cascade recycling systems—combined with microbial community division of labor or compartmentalized cell design. This approach will overcome existing conversion rate bottlenecks, ultimately achieving economically efficient large-scale production.

Figure 4. Synthesis Pathways of Different Substrate SLs in E. coli. glpF: Glycerol facilitator protein; glpK: Glycerol kinase; glpD: Glycerol 3-phosphate dehydrogenase; DHAP: Dihydroxyacetone phosphate; gapA, gapB: Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase A, Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase B; pgK: Phosphoglycerate kinase; pgM: Phosphoglycerate mutase; GAP: Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate; Gly-2P: Glycerol-2-phosphate; eno: Enolase; PEP: Phosphoenolpyruvate; PYK: Pyruvate kinase; ppsA: Phosphoenolpyruvate synthase A; PYR: Pyruvate; Acetyl-CoA: Acetyl coenzyme A; TCA: Tricarboxylic acid cycle; ptsG: Phosphotransferase system glucose-specific transporter subunit G; pgi: Phosphoglucose isomerase; G6P: Glucose 6-phosphate; F6P: Fructose 6-phosphate; FBP: Fructose-1,6-bisphosphate; glms: Glutamine-fructose-6-phosphate aminotransferase; nagB: Glucosamine-6-phosphate deaminase; nagA: N-acetylglucosamine-6-phosphate deacetylase; glmM: Phosphoglucosamine mutase; GlcN-6P: Glucosamine-6-phosphate; GlcNAc-6P: N-acetylglucosamine-6-phosphate; nanE: N-acetylglucosamine-6-phosphate 2-epimerase; nanK: N-acetylmannosamine kinase; ManNAc-6P: N-acetylmannosamine-6-phosphate; ManNAc: N-Acetylmannosamine; neuB: N-acetylneuraminic acid synthase; neuA: CMP-Neu5Ac synthase; pts6: α2-6 sialyltransferase; 6′-SL: 6′-Sialyllactose; nanA: N-acetylneuraminic acid lyase; neuC: UDP-N-acetylglucosamine 2-epimerase; GlcN-1P: Glucosamine-1-phosphate; glmU: UDP-N-acetylglucosamine pyrophosphorylase/glucosamine-1-phosphate acetyltransferase; GlcNAc-1P: N-acetylglucosamine-1-phosphate; UDP-GlcNAc: Uridine-5′-diphosphate-N-acetylglucosamine; Neu5Ac: N-Acetylneuraminic acid; CMP-Neu5Ac: Cytidine monophosphate-N-acetylneuraminic acid; pts3: ST3 beta-galactoside alpha-2,3-sialyltransferase; pts6: ST6 beta-galactoside alpha-2,6-sialyltransferase; Lactose: Lactose; Glucose: Glucose; Glycerol: Glycerol; 3′-SL: 3′-Sialyllactose; 6′-SL: 6′-Sialyllactose; GlcNAc: N-acetylglucosamine; age: N-acetylglucosamine 2-epimerase; yqaB: N-acetylglucosamine-6-phosphate phosphatase.

Whole-Cell Fermentation Method for SL Synthesis

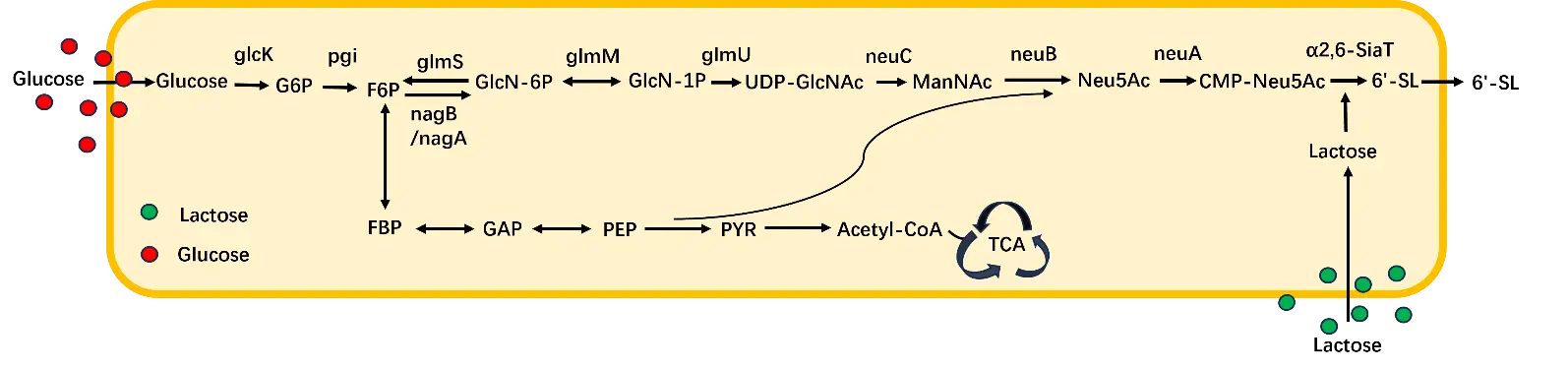

Whole cell fermentation method of SL is categorized into three methods: single-cell catalysis, dual-cell catalysis, and multicell fermentation synthesis. Single-cell synthesis involves cloning all required genes into a single host, achieving de novo heterologous synthesis through genetic engineering modifications and metabolic pathway optimization. The metabolically engineered E. coli BL21star(DE3)ΔlacZ single-cell platform achieved high-efficiency 3′-SL production at 56.8 g/L through non-essential gene knockout, exogenous biosynthetic module integration, carbon flux optimization, and cofactor cycling enhancement [68]. Fierfort N et al. simultaneously expressed the α2-3 fucosyltransferase gene alongside neuC, neuB, and neuA genes in E. coli. They concurrently knocked out genes encoding Neu5Ac aldolase, ManNAc kinase, and β-galactosidase to prevent substrate degradation, thereby ensuring all precursors were directed toward SL synthesis. Through continuous lactose supplementation during fermentation, the recombinant strain ultimately achieved a heterologously expressed SL concentration of 25 g/L [69]. Jianming Yao et al. developed a modular metabolic engineering approach using engineered E. coli DAT07, which incorporated targeted gene deletions (nanA, nanK, nanE, nanT) and an optimized single-plasmid expression system. Through systematic optimization using GlcNAc, lactose, and CMP-NeuAc as substrates, the engineered strain achieved a maximum heterologous expression level of 3′-SL reaching 30.18 g/L in a 5-L bioreactor [70]. Long Liu et al. first integrated neuC, neuB, neuA (derived from Neisseria meningitidis), and pst6 (derived from Photobacterium sp. JT-ISH-224) to construct a synthetic pathway for 6′-SL in Bacillus subtilis. Using glucose as the substrate and adding 20 g/L lactose, they successfully synthesized 6′-SL with a yield of 135.17 mg/L (Figure 5). Finally, de novo synthesis of 6′-SL was achieved in Bacillus subtilis through multiple metabolic engineering approaches combined with heterologous expression of four key enzymes, resulting in a titer of 3.55 g/L in shake flasks and 15.0 g/L in 3L fermenters [71]. Long Liu et al. used glucose and lactose as substrates, de novo biosynthesis of 3′-SL was achieved in engineered Bacillus subtilis 3D6.2 through heterologous expression of specific enzymes (the enzymes encoded by the neuA and nst genes from Neisseria meningitidis) combined with various optimization methods, resulting in a final titer of 1252.1 mg/L [72]. In contrast to E. coli, Bacillus subtilis offers a superior safety profile as a GRAS organism certified by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and it does not produce endotoxins. Consequently, the choice of Bacillus subtilis constitutes a safe and economically viable strategy for synthesis.

In single-cell synthesis, the introduction of exogenous pathways imposes metabolic burdens, energy imbalances, and growth limitations, thereby reducing SL yield. Consequently, most researchers opt for dual-cell catalysis and multicell fermentation synthesis. Zhang et al. pioneered a dual-cell catalysis for the synthesis of 3′-SL. This system compartmentalizes the complex biosynthetic pathway into an E. coli strain and pairs it with S. cerevisiae to achieve CTP recycling, resulting in a significant increase in 3′-SL yield compared to conventional single-cell catalysis. Synthesis of 3′-SL through heterologous expression using lactose, pyruvic acid, and GlcNAc as substrates. The yield is 78.03 g/L, which is currently the highest yield for producing 3′-SL [26]. Multicellular fermentation synthesis of SL requires three or more cells. Endo T et al. developed a microbial coupling method using N-acetylneuraminic acid, orotic acid, and lactose as substrates. By utilizing three engineered E. coli strains and Corynebacterium ammoniagenes to co-express CTP synthetase, CMP-Neu5Ac synthetase, and the α2-3 sialyltransferase gene (nst) from Neisseria gonorrhoeae, they established a whole-cell reaction system achieving a 3′-SL yield of 52 mM (33 g/L) [67,73]. Lastly, we summarize the existing SL synthesis methods in a comparative overview for convenient reference and comprehension, laying a foundation for subsequent discussions on technical bottlenecks and future development directions (Table 3).

Figure 5. The metabolic pathway of SL in Bacillus subtilis. glcK: Glucokinase; pgi: Phosphoglucose isomerase; glmS: Glutamine-fructose-6-phosphate aminotransferase; nagB: Glucosamine-6-phosphate deaminase; nagA: N-acetylglucosamine-6-phosphate deacetylase; glmM: Phosphoglucosamine mutase; glmU: UDP-N-acetylglucosamine pyrophosphorylase; neuC: UDP-N-acetylglucosamine 2-epimerase; neuB: N-acetylneuraminic acid synthase; neuA: CMP-Neu5Ac synthase; α2-6 SiaT: α2-6 sialyltransferase; Glucose: Glucose; G6P: Glucose 6-phosphate; F6P: Fructose 6-phosphate; GlcN-6P: Glucosamine-6-phosphate; GlcN-1P: Glucosamine-1-phosphate; UDP-GlcNAc: Uridine-5′-diphosphate-N-acetylglucosamine; ManNAc: N-Acetylmannosamine; Neu5Ac: N-Acetylneuraminic acid; CMP-Neu5Ac: Cytidine monophosphate-N-acetylneuraminic acid; 6′-SL: 6′-Sialyllactose; Lactose: Lactose; α2-3 SiaT: ST3 beta-galactoside alpha-2,3-sialyltransferase; 3′-SL: 3′-Sialyllactose; FBP: Fructose-1,6-bisphosphate; GAP: Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate; PEP: Phosphoenolpyruvate; PYR: Pyruvate; Acetyl-CoA: Acetyl coenzyme A; TCA: Tricarboxylic acid cycle.

Table 3. Below are some synthetic examples of SL, including their product categories, yields, methods, and host systems.

|

Methodologies |

Product Categories |

Yields (g/L) or Conversion Rate (%) |

Process |

Host Systems |

References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Direct Extraction Methods |

3′-SL 6′-SL |

40% |

Ultrafiltration, nanofiltration, chromatographic separation, and desalination. |

None |

Sanyuan Foods Co., Ltd., Beijing, China |

|

Enzyme Catalyzed Synthesis Method |

3′-SL |

10.40 g/L |

A mathematical modeling-guided cascade biocatalysis synthesizes 3SL from N-acetyl-D-mannosamine via in situ Neu5Ac (two pathways) with key enzymes, optimized for enzyme ratio to reduce protein load. |

None |

[74] |

|

Enzyme Catalyzed Synthesis Method |

3′-SL |

1.16 g/L |

Using engineered sialidase Tr15 from Trypanosoma rangeli, 3′-SL was synthesized directly in cow’s milk via transsialylation of κ-casein glycomacropeptide (cGMP) at 5 °C. |

None |

[33] |

|

Enzyme Catalyzed Synthesis Method |

6′-SL |

Above 20% |

Using a transglycosylation reaction catalyzed by the exo-α-sialidase BfGH33C from Bacteroides fragilis, utilizing sialic acid dimer or oligomer as the glycosyl donor and lactose as the acceptor under optimized conditions (50 °C, pH 6.5, 10 min). |

None |

[34] |

|

Microbial Synthesis Method |

6′-SL |

14.33 g/L |

Blocking lactose degradation/GlcNAc degradation pathways, eliminating carbon catabolite repression (CCR), alleviating metabolic pressure, and implementing fed-batch fermentation. |

Escherichia coli (E. coli) |

[63] |

|

Microbial Synthesis Method |

3′-SL |

25.5 g/L |

Optimizing the flux of the endogenous sialic acid pathway and implementing a two-stage feeding strategy, the recombinant E. coli SG3 was fed and fermented in batches. |

E. coli SG3 |

[64] |

|

Microbial Synthesis Method |

3′-SL |

33 g/L |

A tri-strain system converted orotic acid, NeuAc, and lactose into 33 g/L 3′-SL in 11 h with minimal byproducts, validated at a 5-L scale. |

E. coli NM522, E. coli MM294 and Corynebacterium ammoniagenes |

[67] |

|

Microbial Synthesis Method |

3′-SL |

56.8 g/L |

Blocked degradation pathways via nanA/nanK/nanE/nanT knockout, integrated neuBCA/nST for biosynthesis, optimized carbon flux, regenerated CTP cofactors, and screened transport proteins. |

E. coli BL21star(DE3)ΔlacZ |

[68] |

|

Microbial Synthesis Method |

SL |

25 g/L |

Using metabolically engineered E. coli K12 lacking Neu5Ac aldolase and ManNAc kinase, co-express recombinant sialyltransferases and neuC/neuB/neuA genes for endogenous CMP-Neu5Ac production and lactose sialylation. |

E. coli K12 |

[69] |

|

Microbial Synthesis Method |

6′-SL |

30.18 g/L |

Modular metabolic engineering was employed, encompassing sequential gene knockout, optimization of de novo pathway construction for co-expression of α2-6 sialyltransferase, combinatorial promoter RBS engineering, and multi-chassis screening. |

E. coli DAT07 |

[70] |

|

Microbial Synthesis Method |

6′-SL |

15.00 g/L |

Integrating neuC, neuB, neuA and pst6 to construct a synthetic pathway for 6′-SL |

Bacillus subtilis |

[71] |

|

Microbial Synthesis Method |

3′-SL |

12.52 g/L |

heterologouing expression of specific enzymes (the enzymes encoded by the neuA and nst genes from Neisseria meningitidis) combined with various optimization methods. |

Bacillus subtilis 3D6.2 |

[72] |

|

Microbial Synthesis Method |

6′-SL |

34.00 g/L |

Knocking-out nanA, nanK, and lacZ genes. Decreasing the expression level of the sialyltransferase gene. Increasing the expression level of neuABC genes. |

E. coli DC |

[75] |

|

Microbial Synthesis Method |

3′-SL |

78.03 g/L (maximum) |

Modular synthesis was achieved using engineered Escherichia coli JM109(DE3), with Saccharomyces cerevisiae modules enabling synergistic multi-substrate utilization and CTP regeneration. |

E. coli JM109(DE3) and Saccharomyces cerevisiae |

[26] |

|

Microbial Synthesis Method |

6′-SL |

52.29 g/L (maximum) |

A dual-strain coupled two-step fermentation process was employed to construct an engineered E. coli co-expressing sialyltransferase (ST6 or ST3) and NeuA enzyme. This strain was co-cultured with Saccharomyces cerevisiae to synthesize SL using lactose and sialic acid as substrates. |

E. coli JM109(DE3) and Saccharomyces cerevisiae |

[76] |

4. Optimization of Fermentation Process and Large-Scale Production of SL

4.1. Effect of Fermentation Conditions on Yield and Optimization

The above studies indicate that SL can be effectively enhanced through methods such as metabolic pathway modification of microbial strains and whole-cell fermentation, though the increase remains limited. To further boost SL production, research has revealed that fermentation processes for strains engineered to produce SL can be optimized. Identifying the optimal fermentation conditions for these strains is essential to fully harness their potential and enable large-scale production. Zhang H et al. successfully synthesized 3′-SL through whole-cell catalysis using four genes from three modules. Subsequently, fermentation process optimization was conducted on induction conditions (determining 15 °C as the most critical factor) and substrate concentration, increasing the yield of 3′-SL to 71.62 g/L [26]. Jesper Holck et al. optimized the optimal reaction conditions for 3′-SL synthesis using a salivary acylase derived from Trypanosoma cruzi at pH 5.7 and 30 °C. At these conditions, the enzyme exhibited maximum activity and efficiently converted lactose using casein glycomacropeptide as the Neu5Ac donor [77]. Successfully promoted the synthesis of 3′-SL. In summary, we could enhance SL yield by optimizing fermentation conditions such as temperature, substrate concentration, induction conditions, pH, and other parameters.

4.2. Scale Up Process from Laboratory Shaker Flasks to Reactors

As a key component of HMOs, the industrial production of SL represents a research hotspot in synthetic biology and metabolic engineering. The scale-up process from laboratory-scale shake flasks to reactor-scale production not only serves as the ultimate test of strain performance but also constitutes a complex systems engineering endeavor involving strain adaptation, metabolic regulation, process parameter optimization, and engineered scale-up. Zhang Tao et al. achieved a 3′-SL yield of 9.04 g/L in shake flasks through systematic metabolic engineering of E. coli, including knockout of competing pathways, enhanced precursor supply, and optimized expression of key enzymes. Subsequently, by transferring to a 3 L reactor and employing a fed-batch fermentation process with precise control of nutrient supply and pH, the yield was significantly increased to 44.2 g/L, successfully achieving process scale-up from shake flasks to reactors [78]. Li Jianghua et al. innovatively established a novel metabolic pathway based on N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) for synthesizing 6′-SL, replacing the traditional precursor supply method. By implementing a decoupled cultivation strategy that separates growth and production phases in a 3L reactor, they successfully increased the yield to 14.33 g/L, validating the scalability of this new pathway [63]. Currently, research on scaling up SL production from laboratory-scale shake flasks to reactors remains limited and faces significant challenges. Therefore, we should prioritize studies on its industrial-scale production to lay a solid foundation for commercial manufacturing.

4.3. Advances in Downstream Separation and Purification Technologies and Cost Control

Downstream purification of SL involves steps such as microbial pretreatment and preliminary separation, crude purification, and process optimization. Firstly, the reaction solution underwent heat treatment, followed by sequential ultrafiltration and nanofiltration through membrane systems with varying pore sizes to progressively remove proteins, macromolecular impurities, and most lactose. Membrane separation technology utilizes the selective properties of membranes to separate substances based on molecular size, hydrophilicity, or charge differences. Due to the mild operating conditions of membrane separation processes, which do not require phase transitions, they feature high automation levels and rapid separation rates, making them particularly suitable for the separation and purification of oligosaccharide nutrients. Subsequently, desalting and purification were achieved using ion exchange resin through chromatographic purification techniques, ultimately yielding SL powder with a purity of 95–97%. Cost control relies not only on optimizing purification techniques but also on reducing overall expenses through process integration. For instance, when synthesizing 6′-SL, Li Jianghua et al. engineered E. coli through metabolic engineering, achieving a yield of 14.33 g/L in a 3 L fermenter. This high yield reduced both the raw material input per unit product and the downstream purification burden, thereby indirectly lowering separation costs [63]. This review also systematically summarizes alternative strategies for the separation of SL, with a detailed elaboration of their corresponding detection methodologies, core technical characteristics, and practical separation performance (Table 4). Notably, the current body of research focusing on separation and purification technologies tailored for microbially synthesized SL remains relatively scarce and fragmented. Current efforts primarily focus on small-scale laboratory-based separation, and future studies should prioritize downstream separation and purification techniques.

Table 4. Below are other methods for SL separation, along with their detection techniques, characteristics, and separation capabilities.

|

Separation Methods |

Detection Methods |

Features (Strengths) |

Features (Weaknesses) |

Separation Capability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Capillary Electrophoresis |

Laser-induced fluorescence, mass spectrometry |

High separation efficiency and resolution, rapid analysis speed, minimal sample requirements, and detection sensitivity down to trace levels |

Not easily combined with mass spectrometry. |

Strong |

|

Membrane separation technology |

Calculated by weighing or the concentration difference |

Room-temperature operation, eco-friendly, low-consumption, easily scalable. |

Membrane fouling issues exist, separation precision is limited, and operational pressure requirements apply. |

Moderate |

|

Anion Exchange Chromatography |

Pulse ampere detection |

The separation principle aligns with SL’s negative charge characteristics, operation is relatively simple in nature, and automation level and efficiency are relatively high. |

Low column capacity with challenging post-column collection and complex sample matrices, causing significant interference requiring cumbersome pretreatment. |

Weak |

|

Ion Mobility Spectrometry |

Mass spectrometry |

Extremely fast separation speed, powerful separation capability, minimal sample requirements, and excellent detection compatibility. |

Sensitive to matrix interference, difficult to quantify, and complex migration models. |

Extremely strong |

|

Hydrophilic Interaction Chromatography |

Fluorescence detection, mass spectrometry |

Highly effective at separating SL isomers, excellent compatibility with detection methods, and low solvent consumption. |

High demands on sample pretreatment, complex retention mechanisms, and time-consuming method optimization. |

Strong |

|

Graphitized Carbon Liquid Chromatography |

Mass spectrometry |

High resolution for SL isomers, excellent acid and alkali resistance, and no secondary interactions |

SLs with strong polarity and multiple hydroxyl groups exhibit strong retention and are difficult to elute. |

Extremely strong |

|

Activated Carbon Adsorption Method |

High-Performance Liquid Chromatography |

Simple operation requires no complex instruments, only basic steps such as adsorption and elution. |

Low cost, with inexpensive activated carbon consumables, making it suitable for small-scale coarse separation or pretreatment scenarios. |

Extremely weak |

|

Gel filtration chromatography |

Evaporative Light Scattering Detector |

Mild separation conditions, simple operation, and non-adsorptive. |

Low separation efficiency, lengthy analysis time, and limited sensitivity. |

Weak |

5. The Function of SL

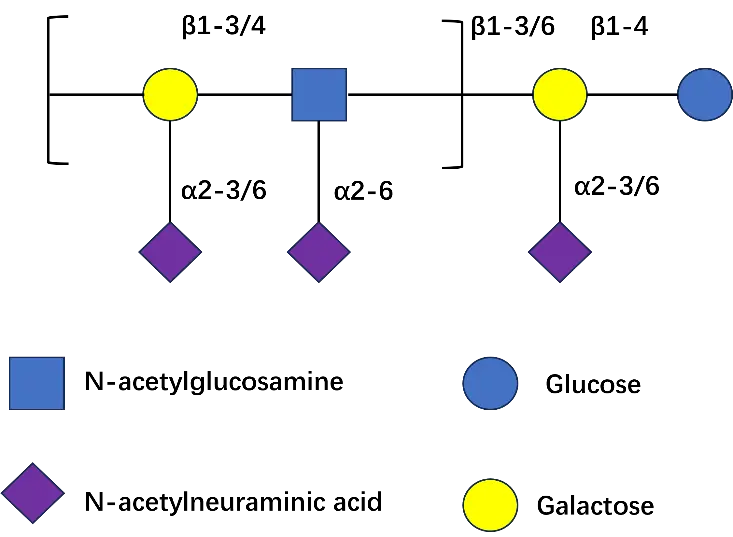

SL is not digested in the small intestine and serves as an important prebiotic that stimulates the growth of specific bifidobacterial populations [79]. However, intact SL can be minimally absorbed by the gut, thereby exerting immunomodulatory effects [80]. SL demonstrates high biological activity and application potential in immune regulation, gut microbiota interactions, antiviral effects, and antitumor activity [81] (Figure 6). Intensive research on these compounds will enhance our understanding of their mechanisms of action and advance their application in human health, including for infants.

5.1. Prebiotic Effect

SL demonstrates notable prebiotic activity by selectively regulating gut microbiota composition. Being a non-digestible carbohydrate, it remains undegraded during passage through the upper digestive system and arrives intact in the colon. There, it functions as a fermentable nutrient source for beneficial microorganisms, specifically Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus strains [82]. These bacteria produce specialized transporter proteins and digestive enzymes, including solute-binding proteins and glycosidases, to break down SL, resulting in enhanced bacterial proliferation and metabolic function. Accordingly, 6′-SL is broadly recognized as a promising prebiotic compound for infant nutrition [83]. Research investigations have verified that 6′-SL serves as an efficient growth substrate for Bifidobacterium infantis, stimulating its propagation [84]. Through its dual capacity to selectively promote beneficial bacteria and strengthen intestinal barrier integrity, SL establishes itself as an effective prebiotic substance [85,86]. These characteristics emphasize its application potential in functional food products and medical approaches addressing gut microbiome-associated pathological conditions.

5.2. Anti-Inflammatory Effect

The anti-inflammatory activity of SL is primarily achieved by modulating key inflammatory signaling pathways. Studies have confirmed that 3′-SL can inhibit the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-6 (IL-6) and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) in lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced macrophages. In an osteoarthritis model, 3′-SL alleviated cartilage destruction by inhibiting NF-κB activation and reducing the expression of matrix metalloproteinases and cyclooxygenase-2 [87,88]. Notably, 6′-SL has also been shown to inhibit Toll-like receptor 4 signal transduction, which is crucial for preventing necrotizing enterocolitis [24,89].

The anti-inflammatory function of SL demonstrates synergistic effects when combined with other active components. For instance, the combination of 3′-SL and Bifidobacterium infantis can more effectively alleviate colitis and restore intestinal barrier function [90]. In summary, SL exhibits multifaceted anti-inflammatory functions through the inhibition of inflammatory pathways, such as NF-κB, the regulation of cytokine production, and synergistic interactions with other probiotics [88]. These findings provide a theoretical basis for its application in nutritional interventions and therapeutic strategies for inflammation-related diseases.

5.3. Antiviral Effect

SL directly interferes with the early stages of viral infection. Its mechanism is largely attributed to acting as a soluble decoy receptor [91]. Many viruses, such as influenza viruses, initiate infection by binding to sialic acid residues on host cell surfaces. SL, bearing a terminal sialic acid, can competitively bind to viral surface proteins, such as hemagglutinin, thereby blocking viral attachment to host cells and preventing subsequent entry and infection [92]. For instance, 3′-SL has demonstrated the ability to inhibit influenza virus infection in vitro. This direct virucidal effect, achieved by mimicking viral receptors, highlights SL’s potential as a natural broad-spectrum antiviral agent, particularly against viruses that utilize sialic acids for cellular entry.

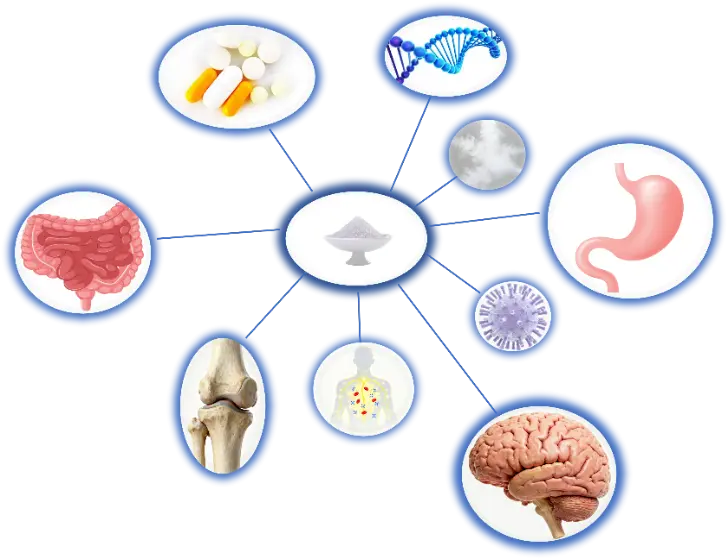

5.4. Promote Brain Development

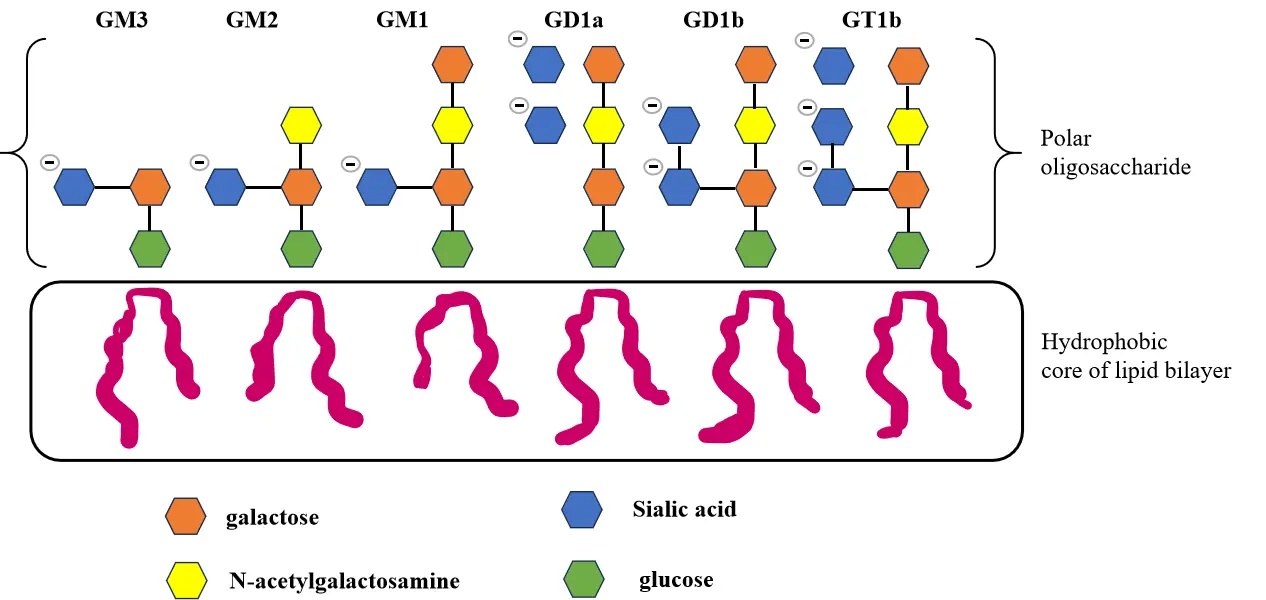

SL demonstrates multifaceted positive effects in promoting brain development. Studies have shown that 3′-SL supplementation significantly enhances learning and memory capabilities in young mice and upregulates the expression of cognition-related genes in the hippocampus [93]. In piglet models, dietary SL intake increased cerebral levels of myoinositol and glutamate, metabolites closely associated with neurodevelopment and myelination [94]. Research indicates that sialic acid, a precursor for the synthesis of glycoproteins and gangliosides in the infant brain, is critical for brain development. By supplying sialic acid, SL increases the levels of these macromolecules, which support memory formation and overall brain maturation [95,96] (Figure 7). Additionally, SL may indirectly influence cognitive function through the gut-brain axis regulatory mechanism. Based on these findings, nutritional formulations containing specific SL ratios have been developed to enhance learning and memory capabilities by increasing SL concentration in the brain.

Figure 7. The figure displays the chemical structures of several brain-derived gangliosides, with the sialic acid residues explicitly marked.

5.5. Immunomodulatory Effect

Numerous studies have elucidated the immunomodulatory properties of SL [97]. Specifically, SL directly interacts with immune cells by binding to specific receptors on the surface of dendritic cells and macrophages, thereby regulating cytokine production and promoting regulatory T cell differentiation. Furthermore, SL enhances intestinal barrier function by upregulating tight junction proteins and promotes the growth of beneficial microbiota that contribute to immune homeostasis. This dual mechanism, combining direct immunocyte regulation and indirect microbiota-mediated effects, establishes SL as a key immunomodulator during early development [82,98,99]. The study by Castillo-Courtade et al. investigated the potential role of several HMOs in treating food allergy symptoms, demonstrating that 6′-SL can alleviate food allergy manifestations by inducing IL-10-producing regulatory cells and indirectly stabilizing mast cells [100]. Current evidence supports its potential applications in nutritional strategies for immune-related disorders and in the optimization of infant formula.

6. Applications of SL

6.1. Infant and Child Nutrition

SL, a key component of HMOs, has garnered significant attention in the field of infant nutrition. It serves not only as a core additive in premium infant formula designed to mimic human milk composition but also demonstrates potential importance in promoting infants’ cognitive, language, and overall development. GRN 921 explicitly permits the addition of 3′-SL sodium salt to infant and follow-on formula for infants aged 0–12 months, establishing a safe dose threshold of 0.28 g/L; GRN documents 881 (2020) and 922 (2021) establish a maximum addition limit of 0.4 g/L for 6′-SL and its sodium salt in formula for full-term infants. Making the composition of infant formula as close as possible to human milk is a key focus in infant nutrition research. The addition of SL to infant formula aims to address the deficiency of this component in traditional formulas, thereby bringing them closer to the natural composition of human milk.

6.2. Functional Foods and Health Supplements

The application of SL in functional foods and health supplements primarily focuses on two aspects: serving as a prebiotic and functioning as a high-value nutritional supplement. Nestlé has patented a nutritional formulation containing a specific ratio of 3′-SL and 6′-SL, specifically designed to enhance learning abilities and promote the growth of beneficial bacteria. This product works by increasing Neu5Ac concentrations in the brain, targeting individuals seeking cognitive health benefits. The composite of xanthan gum and 3′-SL mimetic salivary polysaccharides is engineered for use in cosmetic and health supplement formulations as a bird’s nest substitute, while also providing macromolecular moisturizing properties. This expands the application scenarios for SL in high-end functional ingredients.

6.3. Potential in the Pharmaceutical Sector

As a key component of HMOs, SL has emerged as a frontier focus in drug discovery in recent years due to its remarkable potential in areas such as anti-infection and neuroprotection. The potential of SL in the field of infection control, particularly against viruses, stems from its ability to precisely interfere with the binding process between viruses and host cells. Zhang Ping et al. designed a sugar copolymer containing both sulfated fucose and 6′-SL. This novel drug simultaneously targets two key proteins of the influenza virus hemagglutinin and neuraminidase, demonstrating potent inhibitory activity against both wild-type and drug-resistant influenza strains. It offers a new strategy for combating viral drug resistance [101]. In the field of neuroprotection, SL demonstrates potential for intervening in neurodegenerative diseases, with its effects primarily associated with inhibiting the aggregation of pathogenic proteins. Researchers at Jiangnan University have developed a manno-oligosaccharide-Neu5Ac graft compound. In mouse model experiments, this compound demonstrated the ability to reduce Aβ protein aggregation, improve cognitive function, and decrease amyloid plaque deposition in the brain. Overall, SL demonstrates broad potential in the pharmaceutical field due to its unique sugar structure and multiple biological activities. Of course, translating this potential into mature clinical drugs remains challenging, including optimizing delivery routes, establishing long-term safety profiles, and validating efficacy in clinical trials. However, advances in synthetic biology enabling large scale SL production, coupled with its inherent safety profile due to its natural presence in human milk, undoubtedly position SL as a highly valuable pharmaceutical lead compound. Eventually, to intuitively illustrate the diverse application scenarios of SL, a schematic diagram is provided (Figure 8).

7. Safety Evaluation and Regulatory Status

7.1. Toxicological Evaluation of Synthetic SL

Comprehensive toxicological testing indicates that synthetic SL exhibits high safety under recommended conditions of use. Genotoxicity testing: SL showed no evidence of mutagenicity or genotoxicity in the Ames test, chromosome aberration test, and micronucleus test. Acute and chronic toxicity: Acute oral toxicity LD50 > 5000 mg/kg. In a 26-week repeated-dose study, no observed adverse effect level was observed even at the high dose (6000 mg/kg/day). Although occasional reversible soft stools were noted, no significant adverse effects were observed in key parameters (body weight, blood biochemistry, organ pathology). Toxicokinetic profile: SL exhibits no bioaccumulation in vivo with a short half-life (approximately 1.92–2.38 h), supporting its long-term safety profile. The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) has assessed the sodium salt of SL produced by fermentation using Escherichia coli K-12 DH1 strain, Escherichia coli NEO3 strain (producing 3′-SL), and Escherichia coli NEO6 strain (producing 6′-SL). It concluded that these SL are safe as novel foods under the proposed conditions of use, including in infant formula and foods for special medical purposes [102]. Based on existing toxicological data, synthetic SL is safe for the general population, including infants and young children, when used within the scope and dosage limits specified by regulations. Its safety has been recognized by authoritative bodies, including the European Union.

7.2. Current Regulations Governing the Use of SL in Food and Health Products

As an important HMOs, the use of SL in food and health products must comply with a series of national food safety standards. Currently, 3′-SL and 6′-SL have passed the safety assessment of the U.S. FDA and have been formally included in the GRAS substance list. Simultaneously, both substances have been recognized as novel foods by the EFSA under Regulation (EU) 2015/2283 [103]. This dual certification system provides robust regulatory support for its compliant application in infant formula, functional foods, and other related fields. Several companies worldwide have made significant progress in HMOs production and preparation. For instance, DuPont, Jennewein, and Concord Kirin have all achieved industrial-scale fermentation production of 3′-SL and 6′-SL. However, due to a later start in research, no domestic companies have yet achieved industrialization. In 2023, the National Health Commission of the PRC issued the “Announcement on 15 New Food Ingredients Including Peach Gum”, which included two HMOs substances: 2′-FL and LNnT. In March 2024, the National Health Commission (NHC) issued a public consultation on 3′-SL and 6′-SL as new varieties of food additives, marking official recognition of their safety and necessity as food additives.

8. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

As a key component of HMOs that combines fundamental structure with significant biological activity, the immense nutritional and medical application value of SL has become widely recognized. Currently, microbial fermentation based on synthetic biology has surpassed chemical and enzymatic methods to become the dominant strategy for achieving large-scale green manufacturing of SL. By reconstructing and optimizing biosynthetic pathways in the microbial substrate, the fermentation yield of SL has been significantly enhanced, demonstrating substantial potential for industrial-scale production. However, to overcome the current bottlenecks in industrialization and achieve broader application of SL, breakthroughs must be made across the following dimensions: Disruptive reconstruction of production systems: from “single strain” to “multi strain division of labor and cooperation”. Packing the entire complex SL synthesis pathway into a single strain often induces growth inhibition and metabolic stress. The construction of synthetic microbial communities represents a highly promising direction. In the future, a symbiotic system composed of different engineered strains could be designed. Firstly, “raw material strains” specifically convert inexpensive carbon sources into simple precursors (CMP-Neu5Ac, UDP-GlcNAc). Secondly, “power strains” are responsible for the recycling and regeneration of energy molecules, ATP/CTP. Thirdly, the “synthetic strains” efficiently execute the final SL assembly. Through interspecies metabolite exchange and quorum sensing communication, this system holds promise for achieving production efficiencies far surpassing those of single strains, offering a novel paradigm for massive SL production. The key driver for efficient SL biosynthesis is a high-performance SiaT. Currently, widely used SiaT enzymes commonly suffer from issues such as low catalytic efficiency, poor thermal stability, and insufficient substrate specificity. The future breakthrough lies in developing efficient protein engineering strategies. Targeted evolution of SiaT can enable precise modifications to the enzyme’s active site, substrate channel, and dynamic conformation, aiming to significantly enhance its catalytic activity and specificity toward lactose receptors. This approach facilitates improved production efficiency of SL. The efficient synthesis of SL is highly dependent on the adequate supply of intracellular precursors. Traditional static gene knockout and overexpression strategies often lead to metabolic imbalances. Future research should focus on introducing a dynamic metabolic regulatory system to integrate metabolic engineering approaches to systematically optimize the Neu5Ac synthesis module. This includes enhancing the catalytic performance of key enzymes, knocking out competing pathways, regulating transporters, and implementing cofactor regeneration strategies to maximize precursor flux. Concurrently, dynamic regulatory strategies should be considered to balance cellular growth with product synthesis.

Currently, the synthesis of sialic acid lactulose still faces a series of core challenges that require urgent resolution. At the technical level, highly efficient and low-cost synthetic pathways remain immature. The activity, stability, and catalytic efficiency of key enzymes still need improvement, and reliance on expensive substrates keeps production costs high. At the industrialization level, transitioning from laboratory-scale to large-scale production presents significant technical bottlenecks. These include process control in large bioreactors, mass transfer efficiency, and downstream technologies for efficient separation and purification. Regarding safety, establishing stringent safety evaluation and quality control standards applicable to diverse application scenarios, particularly infant and toddler foods, is a critical hurdle that must be overcome before product commercialization. Resolving these challenges is essential to propel this technology from laboratory achievements to widespread market adoption. Precision regulation of metabolic pathways through synthetic biology tools and the development of microbial cell factories capable of directly utilizing inexpensive carbon sources represent the fundamental pathway to cost reduction. Promoting the effective integration of diverse synthetic technologies holds promise for balancing yield, purity, and cost. Ultimately, with ongoing technological breakthroughs and deepening cross-disciplinary collaboration, SL is poised to realize its broad application prospects in personalized nutrition and specific health needs.

Statement of the Use of Generative AI and AI-Assisted Technologies in the Writing Process

During the preparation of this manuscript, the author(s) used ChatGPT in order to refine the English expressions. After using this tool/service, the author(s) reviewed and edited the content as needed and take(s) full responsibility for the content of the published article.

Acknowledgments

This work supported by BYHEALTH Nutrition and Health Research Foundation (NO. TY202101096) and China National key Research and development Program from International scientific and technological innovation cooperation between the governments of China and Egypt (grant number 2024YFE0199700).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.Z. and H.W.; Methodology, H.Z.; Software, X.C.; Investigation, Z.Z.; Resources, H.Z.; Data Curation, Z.Z. and X.L.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, H.W.; Writing—Review & Editing, H.Z. and H.W.; Supervision, H.Z.; Project Administration, X.C. and H.W.; Funding Acquisition, H.Z.

Ethics Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Funding

This research was funded by BYHEALTH Nutrition and Health Research Foundation (NO. TY202101096); China National key Research and development Program from International scientific and technological innovation cooperation between the governments of China and Egypt (grant number 2024YFE0199700).

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

-

Sato K, Nakamura Y, Fujiyama K, Ohneda K, Nobukuni T, Ogishima S, et al. Absolute quantification of eight human milk oligosaccharides in breast milk to evaluate their concentration profiles and associations with infants’ neurodevelopmental outcomes. J. Food Sci. 2024, 89, 10152–10170. doi:10.1111/1750-3841.17597. [Google Scholar]

-

Smilowitz JT, Lebrilla CB, Mills DA, German JB, Freeman SL. Breast milk oligosaccharides: structure-function relationships in the neonate. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2014, 34, 143–169. doi:10.1146/annurev-nutr-071813-105721. [Google Scholar]

-

Meredith-Dennis L, Xu G, Goonatilleke E, Lebrilla CB, Underwood MA, Smilowitz JT. Composition and Variation of Macronutrients, Immune Proteins, and Human Milk Oligosaccharides in Human Milk from Nonprofit and Commercial Milk Banks. J. Hum. Lact. 2018, 34, 120–129. doi:10.1177/0890334417710635. [Google Scholar]

-

Garrido D, Dallas DC, Mills DA. Consumption of human milk glycoconjugates by infant-associated bifidobacteria: mechanisms and implications. Microbiology 2013, 159, 649–664. doi:10.1099/mic.0.064113-0. [Google Scholar]

-

Borewicz K, Gu F, Saccenti E, Arts ICW, Penders J, Thijs C, et al. Correlating Infant Fecal Microbiota Composition and Human Milk Oligosaccharide Consumption by Microbiota of 1-Month-Old Breastfed Infants. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2019, 63, e1801214. doi:10.1002/mnfr.201801214. [Google Scholar]

-

Nguyen TLL, Nguyen DV, Heo KS. Potential biological functions and future perspectives of sialylated milk oligosaccharides. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2024, 47, 325–340. doi:10.1007/s12272-024-01492-3. [Google Scholar]

-

Jantscher-Krenn E, Bode L. Human milk oligosaccharides and their potential benefits for the breast-fed neonate. Minerva Pediatr. 2012, 64, 83–99. [Google Scholar]

-

Ruiz-Palacios GM, Cervantes LE, Ramos P, Chavez-Munguia B, Newburg DS. Campylobacter jejuni binds intestinal H(O) antigen (Fuc alpha 1, 2Gal beta 1, 4GlcNAc), and fucosyloligosaccharides of human milk inhibit its binding and infection. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 14112–14120. doi:10.1074/jbc.M207744200. [Google Scholar]

-

Nilsen M, Madelen Saunders C, Leena Angell I, Arntzen M, Lødrup Carlsen KC, Carlsen KH, et al. Butyrate Levels in the Transition from an Infant- to an Adult-Like Gut Microbiota Correlate with Bacterial Networks Associated with Eubacterium Rectale and Ruminococcus Gnavus. Genes 2020, 11, 1245. doi:10.3390/genes11111245. [Google Scholar]

-

Fukuda S, Toh H, Hase K, Oshima K, Nakanishi Y, Yoshimura K, et al. Bifidobacteria can protect from enteropathogenic infection through production of acetate. Nature 2011, 469, 543–547. doi:10.1038/nature09646. [Google Scholar]

-

Albrecht S, Lane JA, Mariño K, Al Busadah KA, Carrington SD, Hickey RM, et al. A comparative study of free oligosaccharides in the milk of domestic animals. Br. J. Nutr. 2014, 111, 1313–1328. doi:10.1017/s0007114513003772. [Google Scholar]

-

Craft KM, Townsend SD. The Human Milk Glycome as a Defense Against Infectious Diseases: Rationale, Challenges, and Opportunities. ACS Infect. Dis. 2018, 4, 77–83. doi:10.1021/acsinfecdis.7b00209. [Google Scholar]

-

Antunes KH, Fachi JL, de Paula R, da Silva EF, Pral LP, Dos Santos A, et al. Microbiota-derived acetate protects against respiratory syncytial virus infection through a GPR43-type 1 interferon response. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 3273. doi:10.1038/s41467-019-11152-6. [Google Scholar]

-

Yu ZT, Chen C, Kling DE, Liu B, McCoy JM, Merighi M, et al. The principal fucosylated oligosaccharides of human milk exhibit prebiotic properties on cultured infant microbiota. Glycobiology 2013, 23, 169–177. doi:10.1093/glycob/cws138. [Google Scholar]

-

Plaza-Díaz J, Fontana L, Gil A. Human Milk Oligosaccharides and Immune System Development. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1038. doi:10.3390/nu10081038. [Google Scholar]

-

Cai R, Zhang J, Song Y, Liu X, Xu H. Research Progress on the Degradation of Human Milk Oligosaccharides (HMOs) by Bifidobacteria. Nutrients 2025, 17, 519. doi:10.3390/nu17030519. [Google Scholar]

-

Noll AJ, Gourdine JP, Yu Y, Lasanajak Y, Smith DF, Cummings RD. Galectins are human milk glycan receptors. Glycobiology 2016, 26, 655–669. doi:10.1093/glycob/cww002. [Google Scholar]

-

Wang B. Sialic acid is an essential nutrient for brain development and cognition. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2009, 29, 177–222. doi:10.1146/annurev.nutr.28.061807.155515. [Google Scholar]

-

Bondue P, Crèvecoeur S, Brose F, Daube G, Seghaye MC, Griffiths MW, et al. Cell-Free Spent Media Obtained from Bifidobacterium bifidum and Bifidobacterium crudilactis Grown in Media Supplemented with 3′-Sialyllactose Modulate Virulence Gene Expression in Escherichia coli O157:H7 and Salmonella Typhimurium. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 1460. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2016.01460. [Google Scholar]

-

Craft KM, Townsend SD. Mother Knows Best: Deciphering the Antibacterial Properties of Human Milk Oligosaccharides. Acc. Chem. Res. 2019, 52, 760–768. doi:10.1021/acs.accounts.8b00630. [Google Scholar]

-

Lis-Kuberka J, Orczyk-Pawiłowicz M. Sialylated Oligosaccharides and Glycoconjugates of Human Milk. The Impact on Infant and Newborn Protection, Development and Well-Being. Nutrients 2019, 11, 306. doi:10.3390/nu11020306. [Google Scholar]

-

Duman H, Bechelany M, Karav S. Human Milk Oligosaccharides: Decoding Their Structural Variability, Health Benefits, and the Evolution of Infant Nutrition. Nutrients 2024, 17, 118. doi:10.3390/nu17010118. [Google Scholar]

-

Zhou Q, Lu S, Feng K, Na K, Xiang L, Xiao M, et al. Comparative effect of sialic acid and 3′-sialyllactose on fecal microbiota fermentation and prebiotic activity in ETEC-challenged IPEC-J2 cells. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2025, 105, 6615–6629. doi:10.1002/jsfa.14372. [Google Scholar]

-

Zhu Y, Zhang J, Zhang W, Mu W. Recent progress on health effects and biosynthesis of two key sialylated human milk oligosaccharides, 3′-sialyllactose and 6′-sialyllactose. Biotechnol. Adv. 2023, 62, 108058. doi:10.1016/j.biotechadv.2022.108058. [Google Scholar]

-

Chen Z, Song Y, Yan Y, Wu Z, Xu J. Simulative Fabrication of Milk Fortified with Sialyloligosaccharides and Its Prospective Applications. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2025, 73, 15835–15846. doi:10.1021/acs.jafc.5c02884. [Google Scholar]

-

Zhang Z, Zhang H, Wang Z, You X, Mao Y, Li Z, et al. A Cellular Coupling Strategy Leveraging Pathway Modularization and Cofactor Regeneration for the biosynthesis of 3′-Sialyllactose. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2025, 73, 18380–18389. doi:10.1021/acs.jafc.5c04764. [Google Scholar]

-

Chen J, Hansen T, Zhang QJ, Liu DY, Sun Y, Yan H, et al. 1-Picolinyl-5-azido Thiosialosides: Versatile Donors for the Stereoselective Construction of Sialyl Linkages. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2019, 58, 17000–17008. doi:10.1002/anie.201909177. [Google Scholar]

-

Li C, Liu Z, Li M, Miao M, Zhang T. Review on bioproduction of sialylated human milk oligosaccharides: Synthesis methods, physiologic functions, and applications. Carbohydr. Polym. 2025, 352, 123177. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2024.123177. [Google Scholar]

-

Juge N, Tailford L, Owen CD. Sialidases from gut bacteria: A mini-review. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2016, 44, 166–175. doi:10.1042/bst20150226. [Google Scholar]

-

Abeln M, Albers I, Peters-Bernard U, Flächsig-Schulz K, Kats E, Kispert A, et al. Sialic acid is a critical fetal defense against maternal complement attack. J. Clin. Investig. 2019, 129, 422–436. doi:10.1172/jci99945. [Google Scholar]

-

Schmölzer K, Eibinger M, Nidetzky B. Active-Site His85 of Pasteurella dagmatis Sialyltransferase Facilitates Productive Sialyl Transfer and So Prevents Futile Hydrolysis of CMP-Neu5Ac. Chembiochem 2017, 18, 1544–1550. doi:10.1002/cbic.201700113. [Google Scholar]

-

Lu N, Ye J, Cheng J, Sasmal A, Liu CC, Yao W, et al. Redox-Controlled Site-Specific α2-6-Sialylation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 4547–4552. doi:10.1021/jacs.9b00044. [Google Scholar]

-

Perna VN, Dehlholm C, Meyer AS. Enzymatic production of 3′-sialyllactose in milk. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 2021, 148, 109829. doi:10.1016/j.enzmictec.2021.109829. [Google Scholar]

-

Guo L, Chen X, Xu L, Xiao M, Lu L. Enzymatic Synthesis of 6′-Sialyllactose, a Dominant Sialylated Human Milk Oligosaccharide, by a Novel exo-α-Sialidase from Bacteroides fragilis NCTC9343. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2018, 84, e00071-18. doi:10.1128/aem.00071-18. [Google Scholar]

-

Guo J, Jia W, Jia S. The multifaceted roles of ST3GAL family in cancer: Mechanistic insights and therapeutic implications. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 2025, 197, 48–59. doi:10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2025.06.001. [Google Scholar]

-

Agrawal P, Chen S, de Pablos A, Vadlamudi Y, Vand-Rajabpour F, Jame-Chenarboo F, et al. Integrated in vivo functional screens and multiomics analyses identify α2,3-sialylation as essential for melanoma maintenance. Sci. Adv. 2025, 11, eadg3481. doi:10.1126/sciadv.adg3481. [Google Scholar]

-

Dimitroff CJ, Pera P, Dall’Olio F, Matta KL, Chandrasekaran EV, Lau JT, et al. Cell surface n-acetylneuraminic acid alpha2,3-galactoside-dependent intercellular adhesion of human colon cancer cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1999, 256, 631–636. doi:10.1006/bbrc.1999.0388. [Google Scholar]

-

Kim KW, Kim SW, Min KS, Kim CH, Lee YC. Genomic structure of human GM3 synthase gene (hST3Gal V) and identification of mRNA isoforms in the 5′-untranslated region. Gene 2001, 273, 163–171. doi:10.1016/s0378-1119(01)00595-9. [Google Scholar]

-

Okajima T, Fukumoto S, Miyazaki H, Ishida H, Kiso M, Furukawa K, et al. Molecular cloning of a novel alpha2,3-sialyltransferase (ST3Gal VI) that sialylates type II lactosamine structures on glycoproteins and glycolipids. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 11479–11486. doi:10.1074/jbc.274.17.11479. [Google Scholar]

-

Smithson M, Irwin R, Williams G, Alexander KL, Smythies LE, Nearing M, et al. Sialyltransferase ST6GAL-1 mediates resistance to chemoradiation in rectal cancer. J. Biol. Chem. 2022, 298, 101594. doi:10.1016/j.jbc.2022.101594. [Google Scholar]

-

Britain CM, Bhalerao N, Silva AD, Chakraborty A, Buchsbaum DJ, Crowley MR, et al. Glycosyltransferase ST6Gal-I promotes the epithelial to mesenchymal transition in pancreatic cancer cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2021, 296, 100034. doi:10.1074/jbc.RA120.014126. [Google Scholar]

-

Luo Y, Cao H, Lei C, Liu J. ST6GALNAC1 promotes the invasion and migration of breast cancer cells via the EMT pathway. Genes. Genom. 2023, 45, 1367–1376. doi:10.1007/s13258-023-01445-y. [Google Scholar]

-

Dong X, Wang H, Cai J, Wang Y, Chai D, Sun Z, et al. ST6GALNAC1-mediated sialylation in uterine endometrial epithelium facilitates the epithelium-embryo attachment. J. Adv. Res. 2025, 72, 197–212. doi:10.1016/j.jare.2024.07.021. [Google Scholar]

-

Murugaesu N, Iravani M, van Weverwijk A, Ivetic A, Johnson DA, Antonopoulos A, et al. An in vivo functional screen identifies ST6GalNAc2 sialyltransferase as a breast cancer metastasis suppressor. Cancer Discov. 2014, 4, 304–317. doi:10.1158/2159-8290.Cd-13-0287. [Google Scholar]

-