Mechanical Characterization of Ship Building Grade A Steel by Rapid Cooling in Different Liquid Media

Received: 28 September 2025 Revised: 13 November 2025 Accepted: 28 November 2025 Published: 09 December 2025

© 2025 The authors. This is an open access article under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

1. Introduction

The shipbuilding industry comprises many materials like wood, steel, and composites like aluminum alloys, out of which carbon is the most common due to its superiority in availability and cheaper prices [1]. Carbon containing steels can be broken down into 3 categories; high-carbon steels (0.7–1.7% C), medium-carbon steels (0.3–0.7% C), and low-carbon steels (<0.3% C) [2,3]. Although the formation of martensite is generally not expected in mild steel, small amounts may still develop in thin sections or localized regions where the cooling rate becomes extremely high [4,5,6]. Hence in the modern world, the steel industry needs to keep up with the demand as well as the quality of the production including its effect on the environment [7,8]. Out of all the methods for heat treatment, when medium carbon steels are quenched in the right medium, the hardening process has the biggest impact on improving their mechanical qualities as compared to their counterparts [9,10,11]. The effectiveness of quenching is determined by quenching medium, composition, size, heat treatment, as well as the material’s sensitivity to the quenching medium’s cooling characteristics [12].

Mohammad et al. [13] quenched medium-carbon steel using polymer (polyalkylene glycol) solutions with concentrations of 0, 10, 15, and 20%, followed by tempering the samples at 400 °C for 1 h. The tempered specimens were then evaluated for improved mechanical performance through standard hardness and wear tests, along with microstructural examination. Their results indicated that the 10% polyalkylene glycol solution produced the most favorable properties among all quenched and tempered samples. The influence of quenching temperature on the microstructure and mechanical behavior of AISI 420 stainless steel processed through quenching and partitioning (Q&P) was studied. Higher quenching temperatures promoted the development of very fine grain boundaries, whereas lower temperatures primarily produced tempered structures and retained austenite. At the transition between low and high temperatures, the fraction of retained austenite reached its peak value (0.35). However, as cementite formed at higher quenching temperatures, the carbon content within the retained austenite decreased. Although the maximum austenite fraction did not yield the optimum balance of strength and ductility, its mechanical stability improved with increasing carbon content. Mola et al. [14] examined direct quenching following hot rolling in low carbon and low alloy high tensile strength steels. In contrast to coarse bainite from reheat-quenching, which had a 40% improvement in hardenability, the results demonstrated that direct-quenching produced a microstructure of fine pearlite and bainite, improving strength and toughness.

Kou et al. [15] investigated the weld solidification structures of ferritic stainless steels 430, 309 and 304 semi austenitic, and 310 austenitic stainless steels under various quenching procedures. In the absence of quenching, phase changes masked the solidification structures of 309 and 304, whereas 430 displayed quick homogenizations. These structures were made visible by liquid-tin quenching, which also removed martensite and acicular austenite from the 430 welds’ grain borders. On the other hand, quenching had little effect on the solidification structure of 310 stainless steel. The observed microstructures were explained using phase diagrams for the Fe-Cr-Ni and Fe-Cr-C systems. Dhua et al. [16] studied the impact of direct quenching on the structure-property behavior of lean HSLA-100 steels with different compositions. Compared with reheat-quench plates, direct-quench and tempered plates demonstrated higher yield strength (~900 MPa) and lower-temperature impact toughness. However, because of boron segregation, the Nb–Cu–B steel displayed less toughness. Improved mechanical qualities were a result of finer precipitates and a smaller martensite inter-lath spacing.

Duan et al. [17] investigated how the mechanical characteristics and microstructure of high-strength steel were affected by double quenching and tempering (DQT) as opposed to traditional reheat quenching and tempering (RQT). In comparison to RQT (920 MPa and 871 MPa, respectively), the DQT process produced better tensile strength (975 MPa) and yield strength (925 MPa) due to its much-enhanced hardenability. Performance of high strength low alloy steel was compared after quenching in conventional quenchants such as water and SAE engine oil with clay and air as quenching media. The efficiency of quenching was assessed by measuring mechanical characteristics such as impact energy, hardness, and tensile strength. According to the results, palm kernel oil produced the lowest hardness (740.34 HBN), whereas water created the highest hardness (1740.54 HBN) [18].

Khadim et al. [19] quenched AISI 1039 medium carbon steel quenched in cold water, water, oil, and hot water to investigate its mechanical characteristics. The results indicated that hardness and tensile strength increased with increasing heating temperature, reaching their highest values for cold water quenching at 360.4 Hv and 998.6 N/mm2, respectively. With absorbed energy at 23.6 J and wear rate at 2 × 10−7 gm/cm, elongation reduced and impact toughness and wear rates were at their lowest following cold-water quenching.

Komatsubara et al. [20] studied the microstructure and mechanical characteristics of hot-rolled AISI 4140 Steel, in relation to the impacts of DQT and CQT. Through the use of optical and scanning electron microscopy, the study demonstrated that DQT greatly increased impact toughness by producing smaller martensitic packages and finer austenite grain sizes. Furthermore, DQT performed better mechanically than CQT due to reduced Sulphur and phosphorus impurity concentrations close to earlier austenite grain boundaries. Rahman et al. [21] evaluate the mechanical and microstructural characteristics of low carbon steel (AISI 1020) by examining the impacts of heat treatment. After being heated to 950 °C, the specimens were cooled using a variety of quenching media, including ash, water, and air. According to the results, full annealing reduced hardness because of the creation of ferrite, normalizing provided moderate hardness and ductility, and hardening resulted in fine grain boundaries, which greatly increased hardness. Andre et al. [22] compared massive, Carney-type, and dilatometric samples chilled in different quenching conditions to investigate the effect of quenching stresses on hardness. The absence of quenching stress highly increased its hardness in large samples, according to the results. While plastic deformation below 575 °C had little influence on hardness, applying stress during quenching in oil decreased it by 123 HV. However, combining deformations produced hardness that was comparable to large samples. Aronov et al. [23] conducted a study of intense quenching of AISI 8617, which results in high compressive stresses that are deeply penetrated at the surface. This shortens the carburizing time and increases the service life of steel components. The article offers comparative hardness distribution data and describes how this quenching technique is used for different carburized products. Additionally, an environmentally friendly, completely automated intensive quenching system was created to process these carburized goods.

Pandey et al. [24] with an emphasis on temperatures between 623 K to 1033 K, this study examines the phase evolution and mechanical characteristics of modified 9Cr-1Mo P91 steel under various heat treatment settings. Characterization methods showed that whereas higher tempering temperatures generated a desirable combination of yield strength, tensile strength, hardness, toughness, and ductility, low tempering temperatures produced high yield strength and hardness but poor toughness. Salman et al. [25] examines the impact of different quenching media water, oil, and Poly Vinyl Chloride (PVC) on the mechanical properties of 1030 steel, commonly used in machinery parts requiring strength and hardness. Results indicate that water quenching significantly enhances yield strength, ultimate tensile strength, toughness, and hardness, while reducing elasticity and strain hardening. The study compared water, 10% aqueous polymer solutions, and conventional quench oil for hardening carbonitrided parts [26]. Literature survey revealed comprehensive studies were conducted to improve mechanical properties of alloy steel by utilizing post heat treatment methods like quenching and tempering etc. However, most of these investigations employed oil for quenching because of better mechanical properties. Post tempering followed by quenching is not essential due to slow cooling in oil as compared to water. This study emphasized on varying quenching media for ship building steel (AISI 1020) to evaluate impact of different media on mechanical and microstructural properties. Vegetable oil (Canola oil), and Polyvinylpyrrolidone polymer (PVP) are used as quenching media. The selection of a 10 wt% PVP concentration was deliberate, as it ensures a swift and effective cooling rate compared to higher concentrations (20% or more). This difference in cooling performance is directly attributable to the solution’s viscosity; increasing the PVP concentration enhances viscosity, which negatively impacts the cooling rate by promoting the adherence of a thicker, more insulating polymer layer to the material’s surface, consequently degrading heat transportation.

2. Materials and Methods

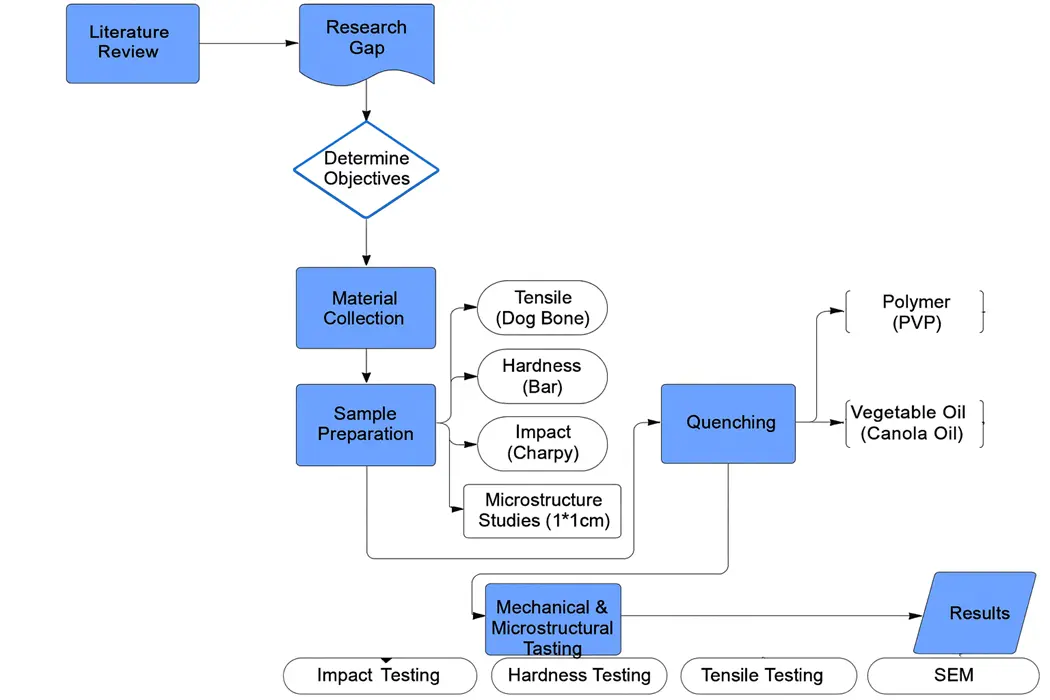

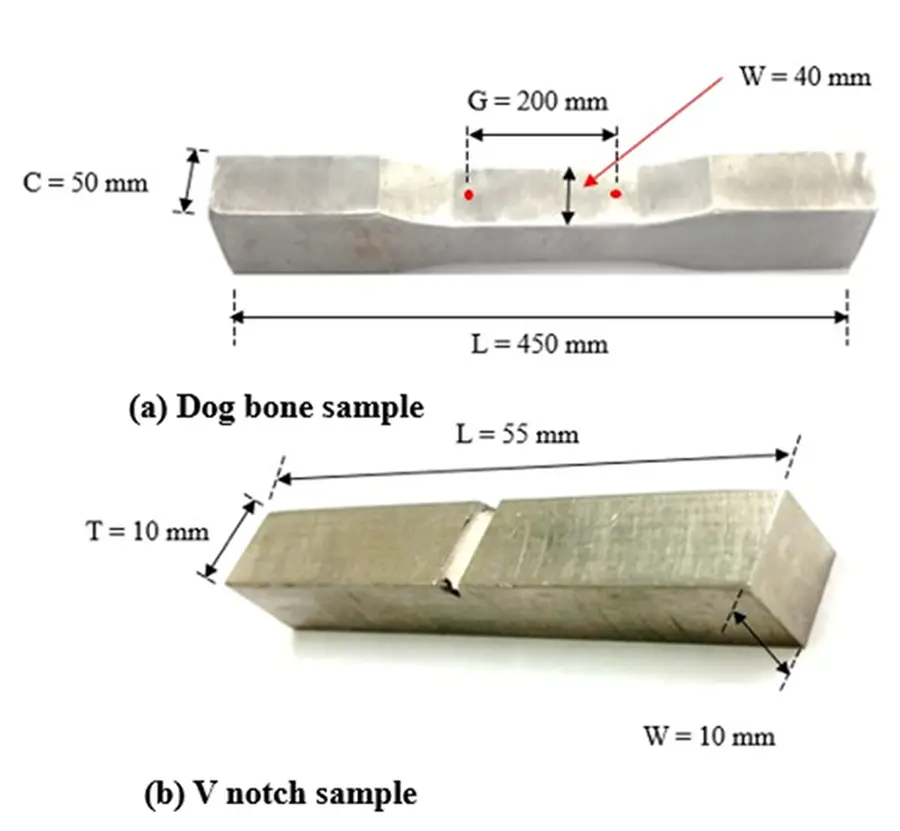

Shipbuilding-grade A steel, is a carbon steel containing 0.2% carbon, was used in this study. The chemical composition was determined using X-ray fluorescence (XRF) spectroscopy, as is shown in Table 1. The percentage of carbon in it confirmed that the steel was classified to be mild steel. A number of tests as shown in process flow chart in Figure 1, including tensile, impact, and hardness tests, have been carried out to determine the mechanical characteristics. SEM, or scanning electron microscopy, was also used to examine the microstructure. In compliance with ASTM E 18-97a guidelines, hardness tests were performed using the Rockwell B scale. Impact testing was conducted using Charpy testing equipment, while tensile testing was conducted using an Ultimate tensile machine with a 150 kN capability. ASTM E8/E8M standards were followed in the preparation of the tensile test samples, as depicted in Figure 2. Impact testing samples as shown in Figure 2 were prepared as per ASTM E23-16B standard. Microstructural study was performed by using Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM). The purpose of these tests was to give a thorough grasp of the material’s microstructural properties and mechanical performance, which are essential for determining if it is suitable for use in shipbuilding. The steel samples were heated to 1000 °C and kept there for 25 min, then it was quickly cooled using PVP, and Canola oil as cooling media. In accordance with ASTM E 407-99, nital, a solution of 2 mL of nitric acid and 100 mL of 98% ethanol, was applied during the etching process for this analysis. The cooling rate of water reported generally is more than 280 ± 30 °C/s, but it much lower for PVP and Canola oil such as 150 ± 20 °C/s and 80 ± 20 °C/s respectively [27].

Table 1. Chemical composition of ship building Grade A steel.

|

Chemical Composition |

Weight (%) |

|---|---|

|

Carbon |

0.2 |

|

Silicon |

0.48 |

|

Manganese |

0.93 |

|

Phosphorus |

0.029 |

|

Sulfur |

0.049 |

|

Iron |

Remaining |

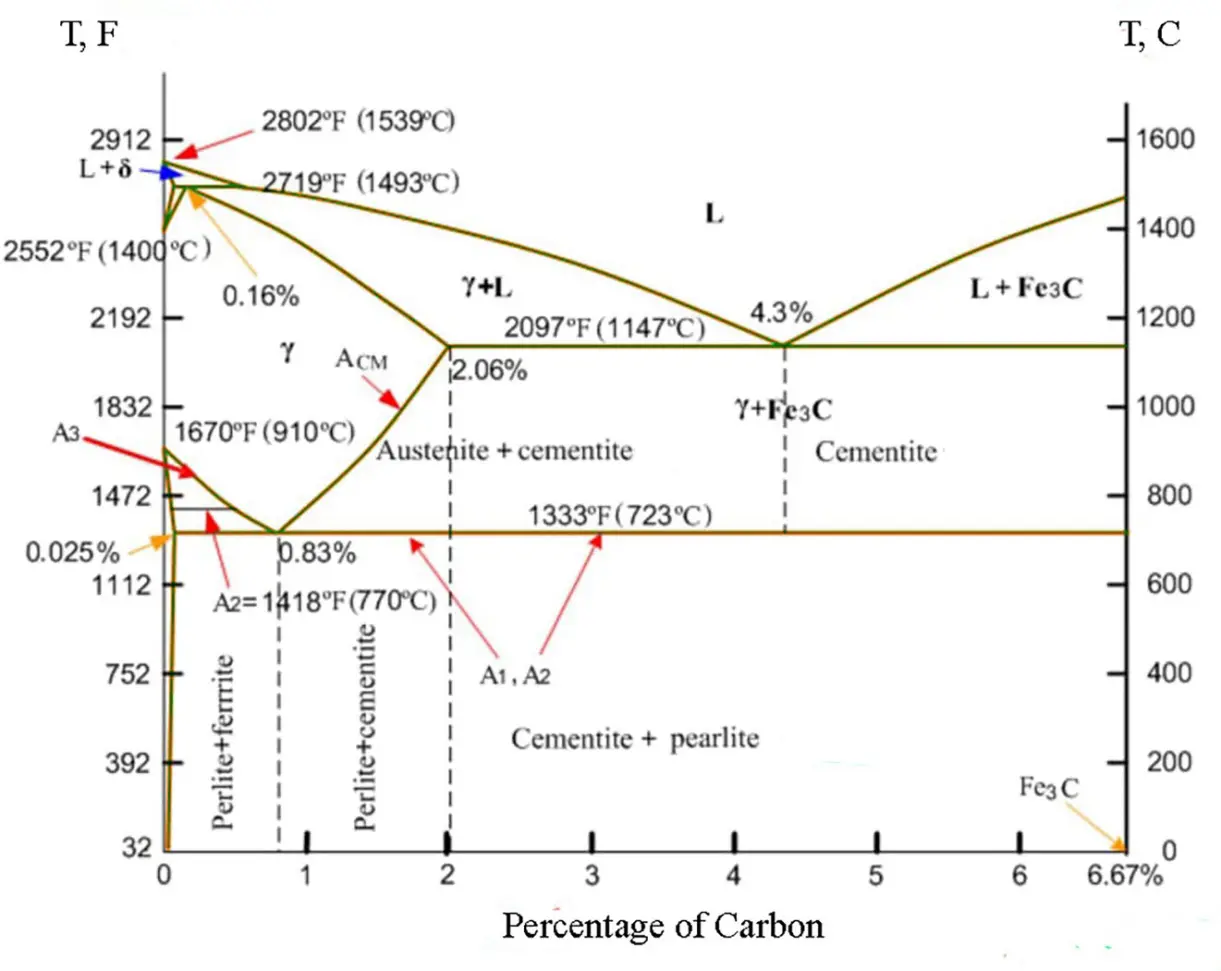

Figure 3 illustrates the phase changes of carbon steel as temperature varies. The amount of carbon directly influences the solid-solution phases: low carbon content in iron results primarily in ferrite with a small amount of pearlite, while increasing the carbon content shifts the microstructure from ferrite toward fully pearlite regions and eventually to hard cementite. All of these phases originate from austenite, which exists as a stable solid solution only above the lower critical temperature (723 °C). At room temperature, austenite is nearly impossible to retain or is highly unstable; therefore, upon cooling from this temperature at a controlled rate, it transforms into ferrite, pearlite, and cementite.

3. Results

3.1. Microstructural Analysis

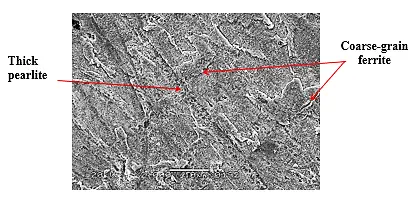

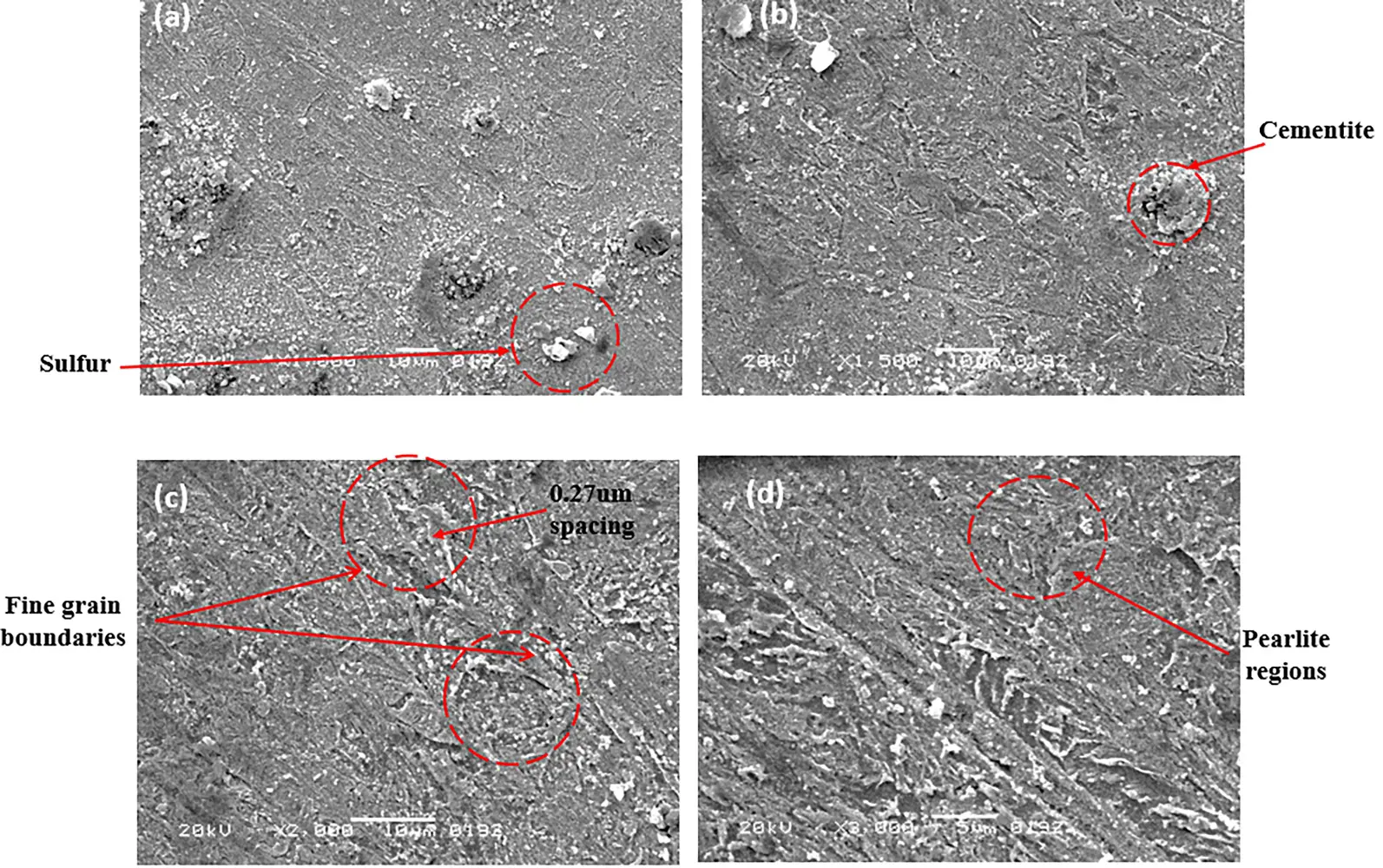

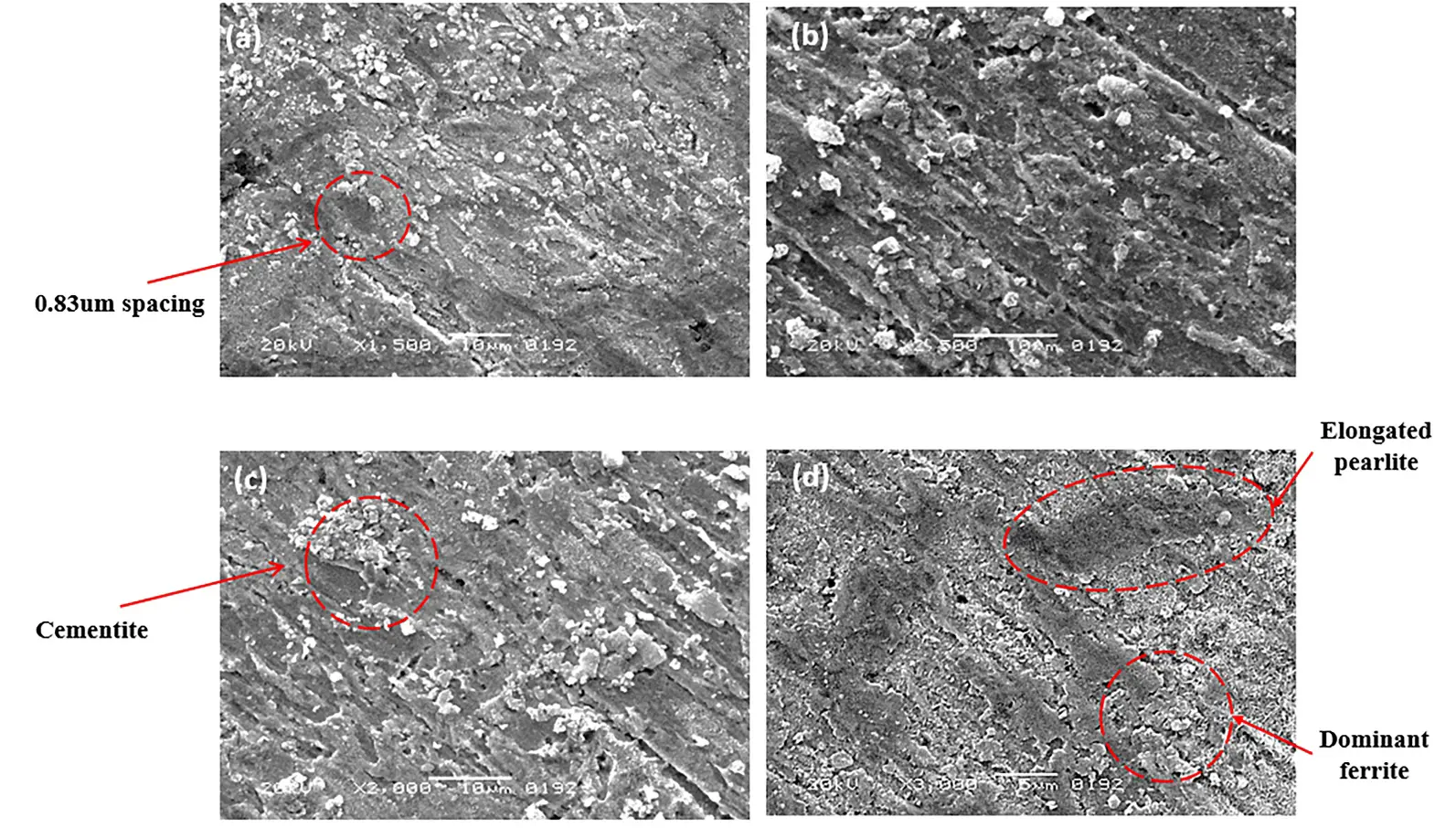

Microstructural evaluation was conducted to identify variations due to different quenching media. Figure 4 depicts the coarse-grained microstructure of a steel specimen produced by slow cooling during annealing. The structure is primarily composed of large, light-colored ferrite grains, accompanied by smaller regions of lamellar pearlite. The pearlite, recognizable by its dark, layered morphology, is mainly located along the ferrite grain boundaries. Figure 5 and Figure 6 depicts microstructure after quenching in vegetable oil and PVP emulsion, respectively.

Figure 5. Micrographs of vegetable-oil quenched samples. (a) sulfur inclusion (b) cloudy cementite (c) fine grain boundaries of ferrite and pearlite (d) highlighting pearlite regions.

Figure 6. Micrographs of PVP quenched samples. (a) ferrite and pearlite grains (b) Coarse grain boundaries (c) Cementite clouds (d) Grains elongation.

The cooling process in canola oil is slower than in water due to its higher viscosity. Since the boiling point of oil is more than twice that of water, the viscous medium tends to adhere to the specimen surface. Heat transfer occurred primarily through natural convection currents within the oil layers, with conduction contributing to a lesser extent. Compared with water quenching, localized carbon segregation leading to cementite formation was less pronounced in Figure 5, as only a minor fraction of cementite was observed. PVP-based polymer cooling was chosen for its broad applicability to steel products. A quenching solution consisting of 10 wt% PVP and 90 wt% water was prepared, offering a moderate cooling rate that falls between that of water and oil. As shown in Figure 6, the resulting microstructure exhibited elongated pearlite, formed due to directional cooling in the PVP medium. These elongated grain boundaries likely arise from enhanced thermal dissipation within the austenite-to-pearlite transformation range.

3.2. Tensile Testing

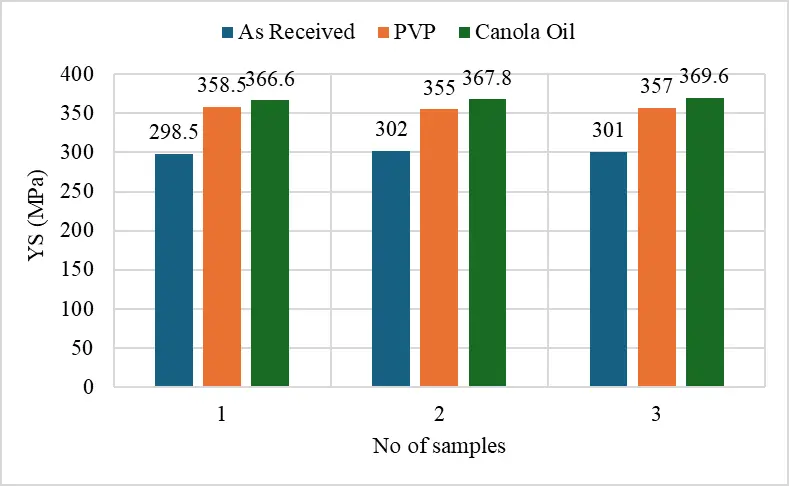

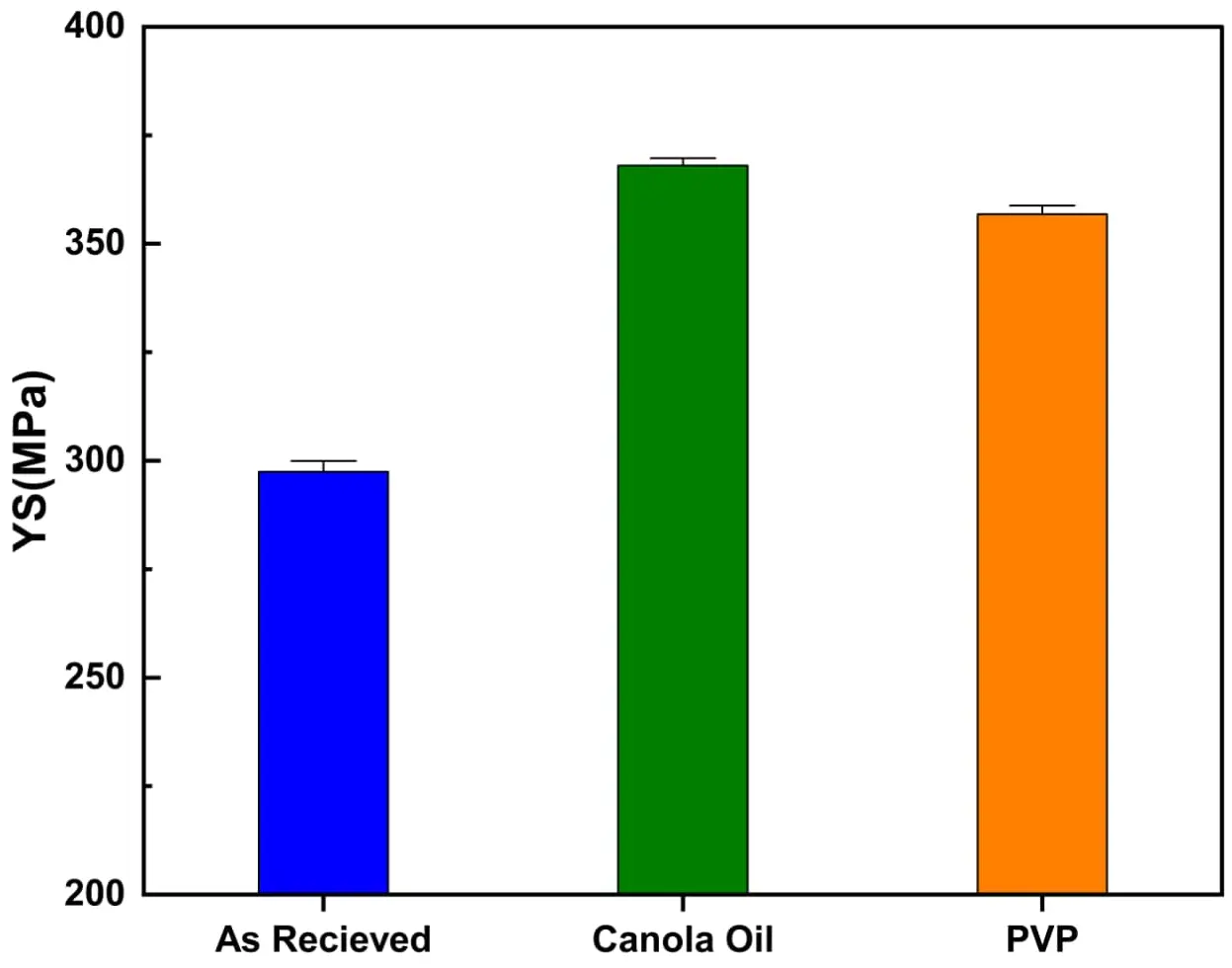

Mechanical testing was performed to assess the effect of quenching media on the alloy’s performance, with the as-received condition serving as the reference. Tensile tests were conducted to determine yield strength (YS), ultimate tensile strength (UTS), and elongation, thereby capturing variations in strength and ductility associated with cooling rate. The variation in YS is presented in Figure 7. The as-received material exhibited the lowest YS, averaging 298 MPa. All quenched conditions demonstrated improvements relative to this baseline. PVP quenching increased YS to 358 MPa, representing an enhancement of 20%. Canola oil quenching produced a slightly higher YS of 370 MPa (24% increase).

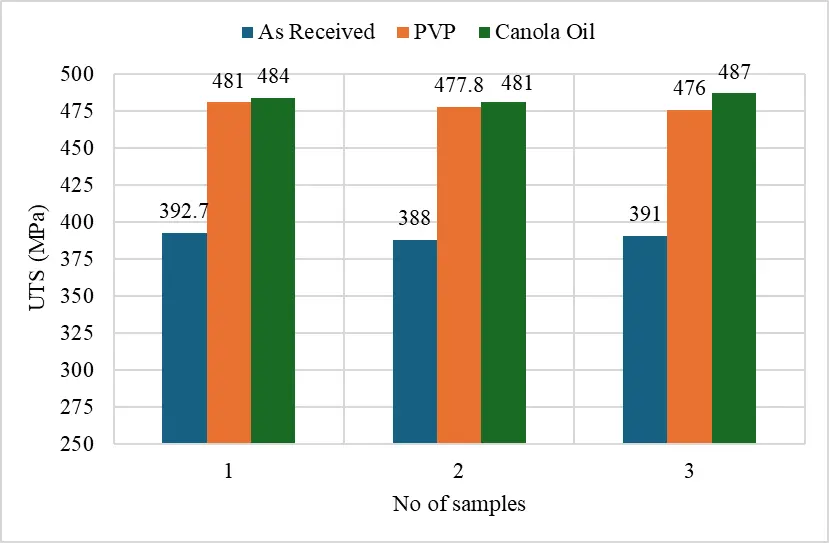

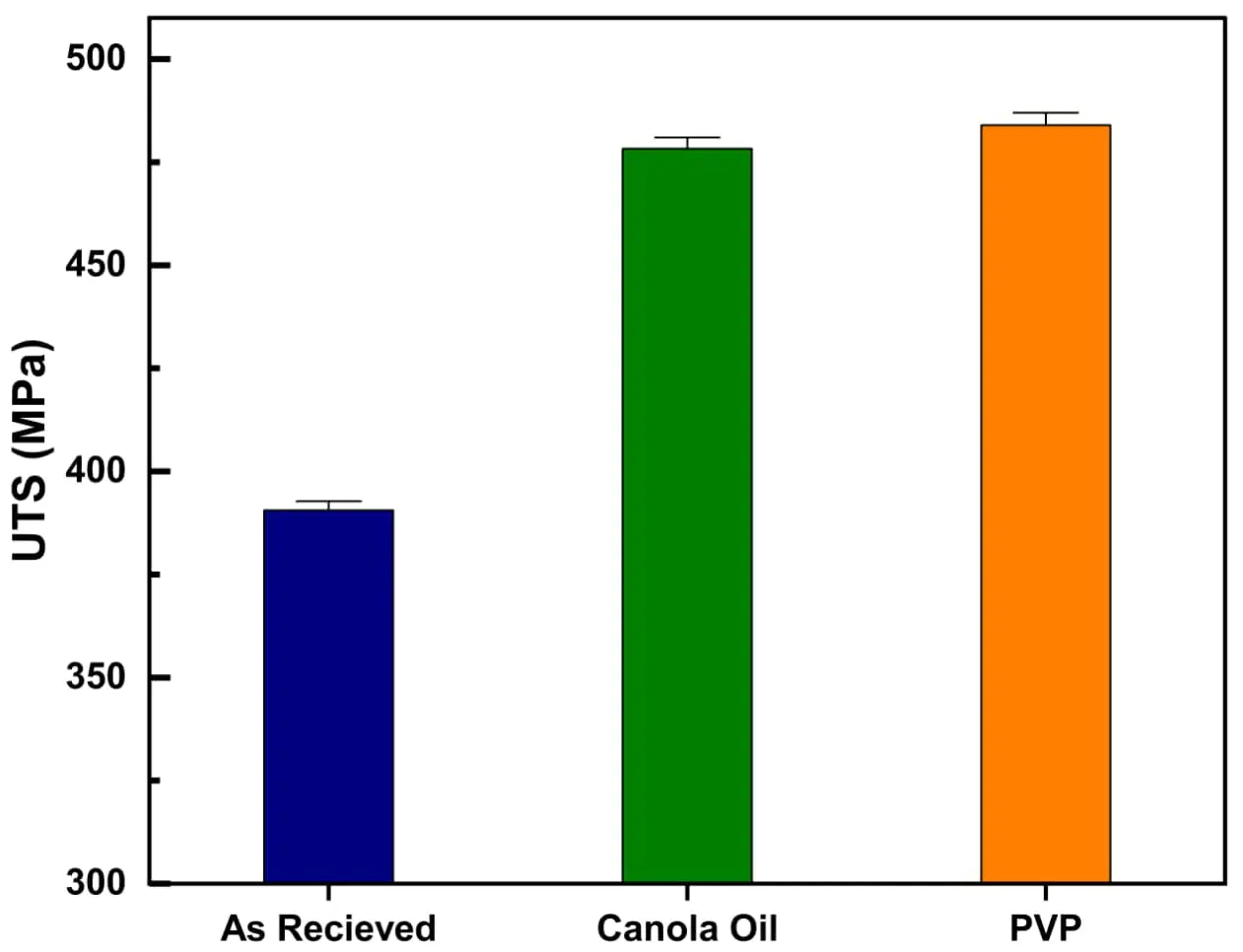

The variation in UTS with quenching media is presented in Figure 8. The annealed (as-received) specimens exhibited the lowest UTS, averaging 398 MPa. PVP quenching increased UTS to 473 MPa, corresponding to an improvement of 19%. Canola oil quenching produced slightly higher values in the range of 485–490 MPa, representing an enhancement of 22%. The improvement can be attributed to microstructural refinement achieved through rapid cooling, which limits dislocation mobility during tensile loading. Specifically, fast cooling promoted the transformation of austenite into fine pearlitic lamellae and ferrite, thereby enhancing strength. The presence of fine ferrite, along with a limited fraction of cementite, further contributed to strength enhancement under applied stress. The difference between YS and UTS was most pronounced in the liquid media quenched and as-received samples, where the formation of multiple microstructural barriers reduced the plastic deformation capacity.

|

|

|

(a) |

(b) |

Figure 7. (a) Samples YS analysis cooled in different quenching media. (b) Error bars with average YS values.

|

|

|

(a) |

(b) |

Figure 8. (a) Samples UTS analysis cooled in different quenching media. (b) Error bars with average UTS values.

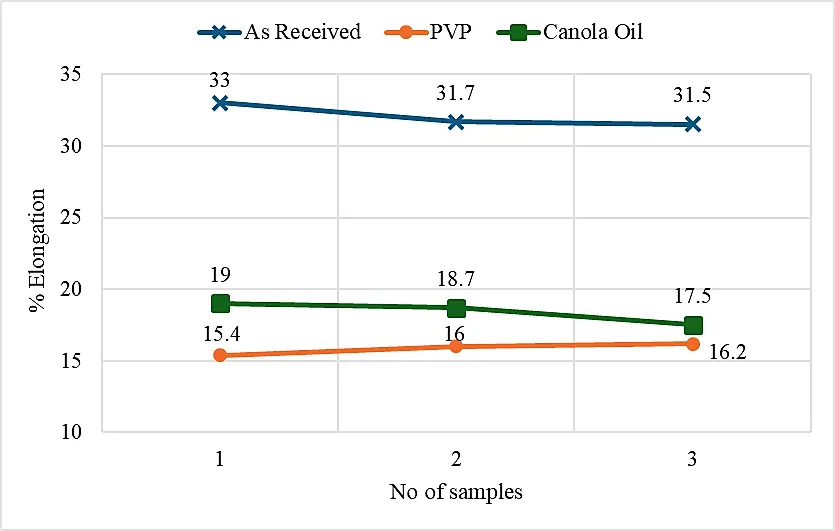

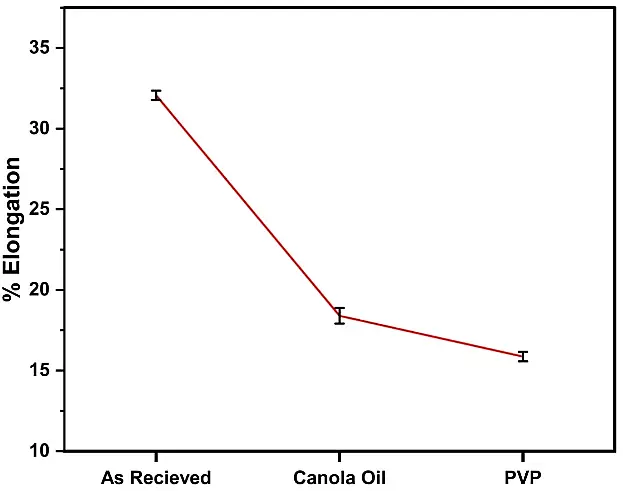

The effect of different quenching media on ductility is expressed in terms of percentage elongation as illustrated in Figure 9. The as received samples displayed the highest elongation values, close to 33 percent. This level of ductility reflects the relatively coarse ferrite-pearlite microstructure and the ease of plastic deformation. Following quenching, a substantial reduction in elongation was observed. PVP quenched samples recorded values of around 15 to 16 percent, which represents a decrease of nearly 50%. Canola oil quenched samples retained slightly higher ductility in the range of 17 to 19% corresponding to a reduction of about 45%.

Moreover, sulfur segregated and local cementite layers also acted as barriers to the plastic flow of material. Canola oil viscosity was higher than polymer coolant, hence elongation of samples quenched in oil was minutely better than PVP. The directional grains of pearlite also generated localized deformation, which ultimately causes residual stresses, hence, ductility is mitigated. The observed hierarchy in ductility followed the reverse of strength, with as received greater than oil, greater than polymer.

|

|

|

(a) |

(b) |

Figure 9. (a) Percentage elongation analysis. (b) Error bars with average values of percent elongation.

3.3. Hardness & Impact Testing

The hardness of the investigated steel samples exhibited a strong dependence on the quenching medium, as shown in Figure 10. The as-received specimen recorded the lowest hardness of 75 HRB, establishing the baseline prior to heat treatment. Quenching in PVP solution resulted in a marked increase to 98 HRB, attributed to moderate cooling rates that promote ferrite grain refinement. The maximum hardness achieved in PVP quenching highlights the pronounced effect of rapid cooling in generating finer microstructures and facilitating partial cementite transformation. The presence of sulfur along grain boundaries further contributed to hardness enhancement. Canola oil quenching produced an intermediate hardness of 90 HRB, consistent with its slower cooling rate compared to PVP, yet more effective than the untreated state. Overall, these findings confirm the critical role of quenching media in tailoring hardness, with PVP quenching yielding the most significant improvement, followed by Canola oil, while the as-received condition remained the lowest.

The results of impact testing in Figure 11 reveal a significant variation in the toughness of the steel under different quenching conditions. The as received samples recorded the highest impact value of 130 J, indicating the ability of the material to absorb maximum energy before fracture. This behavior is characteristic of the coarse ferrite pearlite microstructure present in the untreated state, which promotes ductility and resistance to sudden failure. PVP quenched samples showed a reduced impact value of 107.7 J compared to the as received condition.

The moderate cooling rate of PVP refines the grain structure and increases dislocation density, thereby enhancing strength but reducing ductility, resulting in a corresponding decrease in energy absorption capacity. The sharp decline is associated with the rapid cooling rate in liquid media, which produces a very fine microstructure with partial cementite formation at grain boundaries and sulfur particles. The relatively slower cooling rate of canola oil favors the formation of ferrite and pearlite phases that help in retaining ductility while still improving strength compared to the as received state.

Figure 11. Impact energy absorbed by samples.

4. Discussion

The presence of thick, distinct pearlite lamellae together with the coarse ferrite grains indicates prolonged cooling, which provided ample time for the development of both pre-eutectoid ferrite and coarse pearlite. Water quenching normally shifts austenite into martensite for medium and high carbon steel, but moderate cooling in oil and polymer cannot change austenite to martensite due to the low amount of carbon. The issue of sulfur segregation, which is common due to disturbed cooling, was partially mitigated by the moderate cooling rate. A significant presence of lamellar pearlite was noted, indicating an effective redistribution of carbon from austenite to pearlite after cooling in canola oil. The fine pearlite and ferrite grain boundaries serve as obstacles to dislocation motion, thereby enhancing resistance to plastic deformation. The directional structures due to PVP quenching provide greater resistance to plastic deformation, thereby contributing to an increase in hardness. Fine-grained ferrite is dominant due to the relatively slow cooling rate compared to oil quenching. However, these grains are coarser, and the bright portion of sulfur segregation was increased. Localized diffusion of carbon into cementite was observed in certain regions, which ultimately impacts mechanical properties.

The substantial improvement was witnessed during tensile testing and attributed to rapid cooling, which refined coarse grains into finer structures, thereby increasing barriers to dislocation motion. Furthermore, enhanced carbon diffusion into cementite and the formation of fine pearlitic lamellae contributed additional resistance to dislocation slip, resulting in higher YS. Across all specimens, the consistent trend was depicted that YS of Canola oil was greater than PVP, and as-received steel, with only marginal differences between oil and polymer-quenched samples due to their comparable moderate cooling rates. However, sulfur segregation at grain boundaries and localized cementite formation were also detected due to PVP quenching, which may adversely affect ductility and toughness. Overall, the UTS of oil quenched samples was slightly greater than that of the PVP quenching medium, and the difference was not much pronounced. Confirming that quench severity directly governs strength response. Rapid cooling in liquid media produced the most significant reduction, with elongation values falling to nearly 15%. This reduction of almost 60% compared to the baseline reflects the influence of grain boundary strengthening generated during severe cooling. The resulting increase in hardness comes at the expense of toughness, as the steel becomes more brittle and susceptible to fracture under impact loading. Similarly, Canola oil quenching resulted in an impact value of 111.5 J, which was higher than that for PVP. Table 2 indicates the statistical comparison of the variation in yield and ultimate tensile strength of as-received steel and steel quenched in PVP and Canola Oil. It can be seen that the maximum average tensile and ultimate strength yielded around 368 MPa and 484 MPa, respectively, with a variability of around 4 MPa by means of oil quenching, followed by PVP and the unquenched steel.

Table 2. Statistical data of tensile testing.

|

Yield Strength |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

S.No |

As Received |

PVP |

Oil |

|||||||||

|

Values |

Median |

Mean |

Range |

Values |

Median |

Mean |

Range |

Values |

Median |

Mean |

Range |

|

|

MPa |

MPa |

MPa |

||||||||||

|

R1 |

298.435 |

298.435 |

297.478 |

4 |

358.5 |

357 |

356.833 |

3.5 |

366.6 |

367.8 |

368 |

3 |

|

R2 |

295 |

355 |

367.8 |

|||||||||

|

R3 |

299 |

357 |

369.6 |

|||||||||

|

Ultimate Strength |

||||||||||||

|

S.No |

As Received |

PVP |

Oil |

|||||||||

|

Values |

Median |

Mean |

Range |

Values |

Median |

Mean |

Range |

Values |

Median |

Mean |

Range |

|

|

MPa |

MPa |

MPa |

||||||||||

|

R1 |

392.75 |

396 |

395.25 |

4.25 |

481 |

477.8 |

478.267 |

5 |

484 |

484 |

484 |

6 |

|

R2 |

396 |

477.8 |

481 |

|||||||||

|

R3 |

397 |

476 |

487 |

|||||||||

|

(% Elongation) |

||||||||||||

|

S.No |

As Received |

PVP |

Oil |

|||||||||

|

Values |

Median |

Mean |

Range |

Values |

Median |

Mean |

Range |

Values |

Median |

Mean |

Range |

|

|

% |

% |

% |

||||||||||

|

R1 |

33 |

33 |

32.9667 |

0.7 |

15.4 |

16 |

15.8667 |

0.8 |

19 |

18.7 |

18.4 |

1.5 |

|

R2 |

33.3 |

16 |

18.7 |

|||||||||

|

R3 |

32.6 |

16.2 |

17.5 |

|||||||||

The observed hierarchy in ductility followed the reverse of strength, with as-received greater than oil greater than polymer, as shown in Table 2. Moreover, Table 3 shows that the presence of finer ferrite and partial cementite grain transformation resulted in a maximum hardness of around 98 HRB in the PVP solution compared to the as-received specimen. Furthermore, the coarse ferrite-pearlite grain promoted the ductility exhibited by the mean values of specimens with and without heat treatment.

Table 3. Statistical data of impact testing and hardness.

|

Hardness Test |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

S.No |

As Received |

PVP |

Oil |

|||||||||

|

Values |

Median |

Mean |

Range |

Values |

Median |

Mean |

Range |

Values |

Median |

Mean |

Range |

|

|

HRB |

HRB |

HRB |

||||||||||

|

R1 |

74 |

75 |

75 |

2 |

98 |

98 |

98 |

2 |

92 |

89 |

90 |

3 |

|

R2 |

75 |

97 |

89 |

|||||||||

|

R3 |

76 |

99 |

89 |

|||||||||

|

Impact Test |

||||||||||||

|

S.No |

As Received |

PVP |

Oil |

|||||||||

|

Values |

Median |

Mean |

Range |

Values |

Median |

Mean |

Range |

Values |

Median |

Mean |

Range |

|

|

J |

J |

J |

||||||||||

|

R1 |

130 |

130 |

130 |

0 |

105.7 |

108.3 |

107.667 |

3.3 |

110 |

112 |

111.5 |

2.5 |

|

R2 |

130 |

109 |

112 |

|||||||||

|

R3 |

130 |

108.3 |

112.5 |

|||||||||

5. Conclusions

The effect of different quenching media on AISI 1020 steel was evaluated through mechanical testing and microstructural analysis. Microstructural examination revealed that PVP and Canola oil quenching produced a fine ferritic matrix containing compact pearlite colonies with reduced interlamellar spacing. Liquid quenching resulted in very fine grain boundaries together with a limited fraction of cementite and sulfur particles. In contrast, the as-received material displayed a coarse ferrite-pearlite morphology. Rapid cooling suppressed grain coarsening and increased dislocation density across grain boundaries, which was directly reflected in the mechanical response. The yield strength of the as-received steel was 298 MPa. This improved to 358 MPa with PVP quenching, representing a 20% increase. Canola oil quenching further raised the yield strength to 370 MPa, an enhancement of 24%. Ultimate tensile strength followed the same trend: from 398 MPa in the as-received state, UTS increased by 19% and 22% after PVP and canola oil quenching, respectively. Ductility decreased as a consequence of rapid cooling. Percentage elongation dropped from 33% in the as-received material to 15–16% in PVP-quenched samples, a reduction of about 50%. Canola oil quenching retained elongation values of 17–19%, corresponding to a 45% decrease. Hardness results supported this behavior, increasing from 75 HRB in the as-received condition to 98 HRB with PVP quenching, followed by 90 HRB with Canola oil quenching. Impact testing confirmed the reduction in toughness with increasing quench severity. The as-received steel absorbed 130 J of energy before fracture. This value decreased to 107.7 J for PVP quenching and 111.5 J for Canola oil quenching.

Statement of the Use of Generative AI and AI-Assisted Technologies in the Writing Process

During the preparation of this manuscript, the author(s) used Chatgpt in order to polish and rephrasing the writing content, however, the research results are 100% original. After using this tool/service, the author(s) reviewed and edited the content as needed and take(s) full responsibility for the content of the published article.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express my heartfelt gratitude to the technical staff of Material testing department, NEDUET Karachi for their support in heat treatment and characterization.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.S. and M.H.A.; Methodology, A.S. and M.L.; Software, M.W.; Validation, A.S., M.H.A. and M.U. and M.W.; Formal Analysis, A.S. and M.L.; Investigation, A.S. and M.H.A.; Resources, M.L.; Data Curation, M.U.; Writing Original Draft Preparation, A.S. and M.H.A.; Writing—Review & Editing, M.L. and M.U.; Visualization, M.H.A.; Supervision, M.U.; Project Administration, M.U.

Ethics Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request to the corresponding author.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

-

Demirtas M, Sekban DM. Optimization of strength, ductility and wear resistance of low-carbon grade A shipbuilding steel by post-ECAP annealing. Metall. Res. Technol. 2021, 118, 217. doi:10.1051/metal/2021021. [Google Scholar]

-

Abbasi E, Luo Q, Owens D. A comparison of microstructure and mechanical properties of low-alloy-medium-carbon steels after quench-hardening. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2018, 725, 65–75. doi:10.1016/j.msea.2018.04.012. [Google Scholar]

-

Shazad A, Astif M, Uzair M, Zaidi AA. Evaluation of preheating impact on weld residual stresses in AH-36 steel using Finite Element Analysis. Mem. Investig. En Ingeniería 2024, 26, 225–243. doi:10.36561/ing.26.14. [Google Scholar]

-

Odusote JK, Ajiboye TK, Rabiu AB. Evaluation of Mechanical Properties of Medium Carbon Steel Quenched in Water and Oil. J. Miner. Mater. Charact. Eng. 2012, 11, 859–862. doi:10.4236/jmmce.2012.119079. [Google Scholar]

-

Shazad A, Uzair M, Jadoon J, Saleem Khan M. Mechanical Characterization of Post weld quenched Al 6082-T6 TIG welded Joints. Mem. Investig. En Ingeniería 2025, 28, 58–70. doi:10.36561/ING.28.6. [Google Scholar]

-

Shazad A, Uzair M. Impact of Quenching Medium on Tensile Properties and Hardness of 15CDV6 TIG Welded Joints. Met. Sci. Heat Treat. 2025, 66, 701–707. doi:10.1007/s11041-025-01106-9. [Google Scholar]

-

García Gutiérrez I, Pina C, Tobajas R, Elduque D. Incorporating composition into life cycle assessment of steel grades. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 472, 143538. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2024.143538. [Google Scholar]

-

Ikubanni PP, Adediran AA, Adeleke AA, Ajao KR, Agboola OO. Mechanical properties improvement evaluation of medium carbon steels quenched in different media. Int. J. Eng. Res. Afr. 2017, 32, 1–10. doi:10.4028/www.scientific.net/JERA.32.1. [Google Scholar]

-

Raygan S, Rassizadehghani J, Askari M. Comparison of Microstructure and Surface Properties of AISI 1045 Steel after Quenching in Hot Alkaline Salt Bath and Oil. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2008, 18, 168–173. doi:10.1007/s11665-008-9273-x. [Google Scholar]

-

Senthilkumar T, Ajiboye TK. Effect of Heat Treatment Processes on the Mechanical Properties of Medium Carbon Steel. J. Miner. Mater. Charact. Eng. 2012, 11, 143–152. doi:10.4236/jmmce.2012.112011. [Google Scholar]

-

Shazad A, Uzair M, Tufail M. Influence of Multiple Post Weld Repairs on Mechanical and Microstructural Properties of Butt Weld Joint Utilized in Structural Members. Int. J. Precis. Eng. Manuf. 2024, 26, 157–164. doi:10.1007/s12541-024-01104-6. [Google Scholar]

-

Shazad A, Jadoon J, Uzair M, Akhtar M, Shakoor A, Muzamil M, et al. Effect of composition and microstructure on the rusting of MS rebars and ultimately their impact on mechanical behavior. Trans. Can. Soc. Mech. Eng. 2022, 46, 685–696. doi:10.1139/tcsme-2021-0207. [Google Scholar]

-

Mohmmed JHM, Al-hashimy ZIAH. Effect of Different Quenching Media on Microstructure, Hardness, and Wear Behavior of Steel Used in Petroleum Industries. J. Pet. Res. Stud. 2021, 8, 199–208. doi:10.52716/jprs.v8i2.244. [Google Scholar]

-

Mola J, De Cooman BC. Quenching and partitioning (Q&P) processing of martensitic stainless steels. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 2012, 44, 946–967. doi:10.1007/s11661-012-1420-1. [Google Scholar]

-

Kou S, Le Y. The Effect of Quenching on the Solidification Structure and Transformation Behavior of Stainless Steel Welds. Metall. Trans. A 1982, 13, 1141–1152. doi:10.1007/BF02645495. [Google Scholar]

-

Dhua SK, Sen SK. Effect of direct quenching on the microstructure and mechanical properties of the lean-chemistry HSLA-100 steel plates. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2011, 528, 6356–6365. doi:10.1016/j.msea.2011.04.084. [Google Scholar]

-

Duan Z, Li Y, Zhang M, Shi M, Zhu F, Zhang S. Effects of quenching process on mechanical properties and microstructure of high strength steel. J. Wuhan Univ. Technol. Mater. Sci. Ed. 2012, 27, 1024–1028. doi:10.1007/s11595-012-0593-1. [Google Scholar]

-

Shazad A, Uzair M. Post Weld Quenching Impact on Microstructure and Mechanical Properties (Tensile, Impact, Hardness) of High Strength Low Alloy Steel. Mem. Investig. En Ingeniería 2025, 28, 45–57. doi:10.36561/ING.28.5. [Google Scholar]

-

Kadhim ADZ. Effect of Quenching Media on Mechanical Properties for Medium Carbon Steel. Int. J. Eng. Res. Appl. 2016, 6, 26–34. [Google Scholar]

-

Komatsubara N, Watanabe S, Ohtani H. Improvement of the Strength and Toughness of Steel Plates by Direct-quenching and Tempering. Tetsu-to-Hagané 1983, 69, 975–982. doi:10.2355/tetsutohagane1955.69.8_975. [Google Scholar]

-

Rahman SMM, Karim KE, Simanto MHS. Effect of Heat Treatment on Low Carbon Steel: An Experimental Investigation. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2016, 860, 7–12. doi:10.4028/www.scientific.net/amm.860.7. [Google Scholar]

-

Andre M, Gautier E, Moreaux F, Simon A, Beck G. Influence of Quenching Stresses on the Hardenability of Steel. Mater. Sci. Eng. 1982, 55, 211–217. doi:10.1016/0025-5416(82)90134-3. [Google Scholar]

-

Aronov M, Kobasko N, Powell JA. Intensive quenching of carburized steel parts. IASME Trans. 2005, 2, 1841–1845. [Google Scholar]

-

Pandey C, Giri A, Mahapatra MM. Evolution of phases in P91 steel in various heat treatment conditions and their effect on microstructure stability and mechanical properties. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2016, 664, 58–74. doi:10.1016/j.msea.2016.03.132. [Google Scholar]

-

Salman KD, Ahmed BA, Frhan IN. Effect of Quenching Media on Mechanical Properties of Medium Carbon Steel 1030. J. Univ. Babylon Eng. Sci. 2018, 26, 214–222. [Google Scholar]

-

Gestwa W, Przylecka M, Totten GE. Use of aqueous polymer quenchants for hardening of carbonitrided parts. Int. J. Mater. Prod. Technol. 2005, 24, 126–141. doi:10.1504/ijmpt.2005.007944. [Google Scholar]

-

Vieira EDR, Biehl LV, Medeiros JLB, Costa VM, Macedo RJ. Evaluation of the characteristics of an AISI 1045 steel quenched in different concentration of polymer solutions of polyvinylpyrrolidone. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1313. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-79060-0. [Google Scholar]