Self-Directed Learning Across the Lifespan Regarding Psychological Flow—A Topical Assessment of Recent Publications with High Recall and High Precision

Received: 27 August 2025 Revised: 29 October 2025 Accepted: 10 November 2025 Published: 17 November 2025

© 2025 The authors. This is an open access article under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

1. Introduction

Psychological flow is a theory pioneered by psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi (1934–2021 [1]) in 1975 [2]. Its recognition is as one of the most significant theories in contemporary psychology [3], with its study directing extensive research [4] in various disciplines [5]. An analysis of experiences judged by individuals as enjoyable [6] participating in activities Csikszentmihalyi described as “play-forms” [7] defines psychological flow. Most notably, his studies of play-form participants included chess masters [8], rock climbers [9], elite athletes [10], and professional performance musicians [11]. However, in contrast to play [12], the enjoyment focus for psychological flow is on the conditions under which challenging activities are sustainable [13]. In the words of Csikszentmihalyi, “flow makes us feel better in the moment, enabling us to experience the remarkable potential of the body and mind fully functioning in harmony. However, what makes flow an even more significant tool is its ability to improve the quality of life in the long run” [14] (p. 63). The identification of flow in an activity is a self-directed process for meeting challenges deemed of interest to the individual. Operationally, flow is achievable dependent on the following conditions: (1) clear goals; (2) instantaneous feedback; (3) an equivalence of skills to challenges; (4) an integration of awareness and action; (5) any distractions from the activity are ignored; (6) failure is not considered an option; (7) no self-consciousness is involved; (8) there is a distortion of time; and (9) the activity itself is the desired end [15]. Various methods measure psychological flow. One is self-reporting through either structured [16] or semi-structured interviews [17,18]. Another is the completion of standardized questionnaires, like the widely used Flow State Scale 2 (FSS-2) [19] with cross-cultural validation [20,21,22], which provides a post-event assessment of flow, or the Dispositional Flow Scale 2 (DFS-2) that interprets a presently experienced flow state [23], also with cross-cultural validation [24,25]. Still another measurement technique is the Experience Sampling Method (ESM)—a real-time snapshot [26] of the flow experience and its related factors, like challenge and skill [27]. Some researchers also use physiological measures, including neuroimaging (electroencephalography (EEG) [28] and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) [29]). These techniques observe brain activity during a flow state to study the neurological foundations of flow. Other researchers study physiological data, such as heart rate [30], heart rate variability (HRV) [31], and skin conductance [32].

Self-direction is a requirement of psychological flow, where these must operate together to create “the good life”, in the estimation of Csikszentmihalyi [33]. Self-direction is the degree to which one can formulate goals and learn from previous experiences [34,35] in making decisions free from external control [36]. It relates to self-determination, serving as the basis for motivationally activated behavior [37], since autonomy, competence, and relatedness are essential for enacting self-determined behaviors [37,38]. Self-direction can be measured in various ways with performance-based tasks [39], self-reflection [40], self-reporting [41], and standardized questionnaires [42].

Self-directed learning represents one type of self-determined behavior [43]. Since self-direction depends on choice, one can choose to self-direct learning in correspondence with the demands of others [44]. However, to correspond with the flow, this self-direction requires self-directed learning [45,46] that arises from and is sustained by what the individual values in achieving their personal goals [47]. Although these goals may include adhering to the standards of a group [48], the individual’s desire and goal is to meet these standards—it is not an external imposition. Nevertheless, learning about the necessary structures for meeting the standards is an essential ingredient to self-directed learning [49]. Several methods measure self-directed learning. Some are instruments such as the Self-Directed Learning Readiness Scale (SDLRS) [50,51] or the Self-Rating Scale of Self-Directed Learning (SRSSDL) [52], which measure attitudes, behaviors, and readiness for self-directed learning, or microanalytic assessment in real time during a specific task [53,54]. Qualitative methods of assessment include self-assessment [55], process evaluation [56], and assessing the content and structure of learning activities [57].

In considering psychological flow regarding self-directed learning through the lifespan, the assumption is that changes over a lifetime affect both psychological flow and self-directed learning. This assumption rests on the understanding that people change physiologically [58,59], psychologically [60,61], and in their intentions [62,63].

A post-mortem 2022 publication with Csikszentmihalyi as a co-author identified it as the first assessment of flow throughout the lifespan [64]. What that article does not discuss is the relationship between flow and self-directed learning. Recent empirical studies on the relationship between flow and self-directed learning include those that differentiate by occupation [46,65,66,67], expertise [68,69,70], geographic area [71,72,73], and age [74,75,76]. What they do not discuss is self-directed learning and psychological flow throughout the lifespan. This work will be the first to consider the relationship among all three concepts. The aim is to identify (1) the English language, (2) empirical research studies in (3) peer-reviewed publications with both a (4) high recall and (5) high precision by topic, representing (6) the most promising research directions. The hypothesis is that distinct topics are recognizable using this type of limited review to investigate relationships among self-directed learning, psychological flow, and lifespan—ones that regard the promotion of psychological flow throughout the lifespan through self-directed learning.

2. Materials and Methods

Gathering the materials for this limited review follows the guidelines of the 2020 Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews Statement Extension to Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) [77,78]. In choosing this method, the intention was not to identify the range and depth of research on this subject, as would be the case in an actual scoping review [79]. Nevertheless, the PRISMA-ScR process was viewed as the most appropriate methodology because it is internationally standardized as a review process [80] and considered the best practice for scoping reviews [81]. What differentiates this limited search from a scoping review is its focus on recent high-recall, high-precision peer-reviewed publications. The choice was to limit the review to this extent as the aim of the study was to identify promising current research directions regarding the relationships among self-directed learning, lifespan, and psychological flow. Restricting the search in this way eliminated older research that may no longer be relevant (especially as a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic [82,83,84,85]), publications that are not empirical research studies, and those studies with a low recall. They are not considered for review as they are unlikely to promote the development of empirical research on the topic, the aim of this review.

2.1. Databases

The method began on 3 August 2025. It involved searching six relevant primary databases (APA PsycArticles®, Embase, Medline, PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science) and one supplementary database (Google Scholar). A subsequent search of ProQuest was on 30 October 2025. Included in this search were the following databases: ERIC (Education), International Bibliography of the Social Sciences (IBSS) (Social sciences), and PsycInfo (Psychology). There is no necessary number of databases to search when following the PRISMA-ScR process [81]. The databases searched should be relevant to the literature, as noted in the most recent comments on scoping reviews published in 2022 [81]. However, primary databases—those with consistent results—are distinguished from those considered supplementary databases, where the search results are inconsistent [86]. Although by this measure, Google Scholar is labeled a supplementary database [86], a 2019 study of 12 academic databases identified it as the most comprehensive search engine, acknowledging that it is the database most frequently used by academics. The finding is that it outperforms the coverage of Scopus or Web of Science [87]. This conclusion was additionally reconfirmed in 2023 [88]. The extensive reach of Google Scholar, as an academically respected database, supports including this supplementary database as part of the search process.

The keywords for the primary database searches were “self-directed learning AND lifespan AND psychological flow”. A previous scoping review by the author demonstrated that limiting a Google Scholar search to keywords and Boolean operators restricted the possible results [89]. Consequently, the author conducted a Google Scholar experiment during the database search to examine the extent of returns comparing the inclusion or exclusion of Boolean operators. For Google Scholar, using quotation marks to distinguish keywords is equivalent to the AND Boolean function.

The Google Scholar experiment showed that, in most cases, fewer Boolean operators produced more results. With all three keywords distinguished with quotation marks, there were four results. Removing the quotation marks from the keyword lifespan produced only two additional results. They compare with having all keywords in quotation marks. Eleven more returns resulted from an absence of quotation marks on self-directed learning. Most significantly, there were 970 additional results regarding psychological flow. This result compares with the results of quotation marks differentiating all the keywords. When two of the keywords lacked quotation marks, and psychological flow was the only one with them, there was the least difference between the results of it and when all the keywords retained quotation marks (and thus incorporated Boolean functions), with only 21 additional results. If only self-directed learning retained the quotation marks, the extra results from those of all quotation marks were 2796. When lifespan was the only keyword with quotation marks, the added results were 3806 from those with Boolean operators. The most significant difference corresponding to the initial search with all quotation marks was when they were missing from all keywords. In this case, the results that appeared in addition to the four using Boolean functions were 10,896. These differences regard the number of results for each of the eight Google Scholar searches, labeled A to H. They are in Table 1, along with the results of all the primary database searches.

Table 1. (1) Numbered (#) order of search, (2) databases searched on 3 August 2025 and on 30 October 2025 (ProQuest), (3) the search parameters, and (4) the number of returns regarding searches of the keywords “self-directed learning, lifespan, psychological flow”, listed in the order searched.

|

# |

Database |

Search Parameters |

Returns |

|---|---|---|---|

|

1 |

APA PsycArticles® |

Keywords: self-directed learning AND lifespan AND psychological flow Limits: English language, Publication year: 2021–2025 |

17 |

|

2 |

Embase |

Keywords: self-directed learning AND lifespan AND psychological flow Limits: English language, Publication year: 2021–2025 |

0 |

|

3 |

Medline |

Keywords: self-directed learning AND lifespan AND psychological flow Limits: English language, Publication year: 2021–2025 |

0 |

|

4 |

PubMed |

Keywords: ((self-directed learning) AND (lifespan)) AND (psychological flow) |

0 |

|

5 |

Scopus |

Keywords: self-directed learning AND lifespan AND psychological flow |

0 |

|

6 |

Web of Science |

Keywords: self-directed learning, lifespan, psychological flow. WOS does not have the option to limit a search by year before conducting the search Limit: Publication year: 2021–2025, once the search is performed. |

2 |

|

7 |

A. Google Scholar |

“self-directed learning” “lifespan” “psychological flow” Limit: Publication year: 2021–2025 |

4 |

|

8 |

B. Google Scholar |

“self-directed learning” lifespan “psychological flow” Limit: Publication year: 2021–2025 |

6 |

|

9 |

C. Google Scholar |

self-directed learning “lifespan” “psychological flow” Limit: Publication year: 2021–2025 |

15 |

|

10 |

D. Google Scholar |

self-directed learning lifespan “psychological flow” Limit: Publication year: 2021–2025 |

25 |

|

11 |

E. Google Scholar |

“self-directed learning” “lifespan” psychological flow Limit: Publication year: 2021–2025 |

974 |

|

12 |

F. Google Scholar |

“self-directed learning” lifespan psychological flow Limit: Publication year: 2021–2025 |

2800 |

|

13 |

G. Google Scholar |

self-directed learning “lifespan” psychological flow Limit: Publication year: 2021–2025 |

3810 |

|

14 |

H. Google Scholar |

self-directed learning lifespan psychological flow Limit: Publication year: 2021–2025 |

10,900 |

|

15 |

ProQuest |

Keywords: self-directed learning AND lifespan AND psychological flow Limits: Publication date: after 1 January 2021, Case Study, Feature, Chronology, Report, Research Topic, Statistics/Data Report, English language |

69 |

2.2. The Search Process

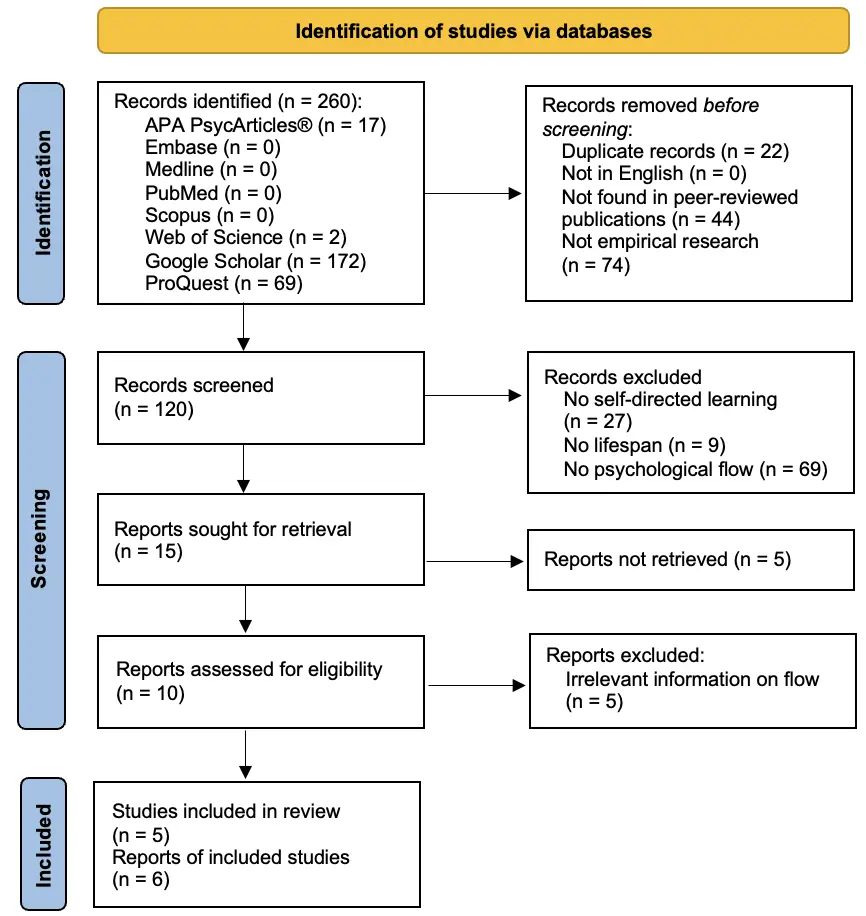

Supplementary S1 provides an in-depth record of the method followed for the PRISMA-ScR process [43]. In this process, the “Records identified” equals the number of returns from each database searched. Only two primary databases contributed to the 3 August 2025, results: APA PsycArticles® (n = 17) and Web of Science (n = 2). Since the aim was to identify only publications with high recall and high precision, the author limited the number of results considered from each of the eight Google Scholar searches to the unique ones and the first 15 pages of 10 returns per page for H. Google Scholar. The result was (n = 150) for H. Google Scholar added to (n = 2) for unique returns found on B. Google Scholar + D. Google Scholar, plus (n = 1) for the unique results of C. Google Scholar + D Google Scholar, plus (n = 10) for those found only one C Google Scholar, added to (n = 1) of the unique result from E. Google Scholar, and (n = 8) of the distinct result from G. Google Scholar. F. Google Scholar produced no unique returns. The total of the assessed records is the Google Scholar result (n = 172) = (n = 150 + 2 + 1 + 10 + 1 + 8). As such, the total records identified on 3 August 2025, was (n = 191).

Concerning the requirements of the PRISMA flow diagram [77], the databases searched are differentiated only regarding “Records identified”. There is a combination of all records returned from each database after the “Records removed before screening”. Removed were the duplicates (n = 3), records not in English (n = 0), those not found in peer-reviewed publications (n = 35), and studies that were not empirical research (n = 68). Marking records as ineligible did not use automation tools. The result of these removals on 3 August 2025, was the following records screened (n = 85). Studies not found in peer-reviewed publications included non-peer-reviewed publications and published abstracts without a full manuscript.

Screening is in three parts following the PRISMA-ScR process [43]. A lack of keywords in the publications resulted in the first exclusions on 3 April 2025. The result was: no self-directed learning (n = 3), no lifespan (n = 4), and no psychological flow (n = 63). After removing these records, the reports sought for retrieval were (n = 15). Five of these reports could not be retrieved, leaving (n = 10) reports assessed for eligibility. An exclusion of five containing irrelevant information was the result after reading the complete reports. The result was (n = 5) studies included in the review, but as one of the publications reported on two studies, (n = 6) represents the reports of included studies.

An additional search on 30 October 2025, was completed—ProQuest. The purpose was to improve the 3 August 2025, search that produced five results with additional reports. The ProQuest search included the following databases: ERIC (Education), International Bibliography of the Social Sciences (IBSS) (Social sciences), and PsycInfo (Psychology). For this search, there were (n = 69) records identified. The exclusions began with those removed before screening: duplicated (n = 19), those not found in peer-reviewed publications (n = 9), and those not based on empirical research (n = 6). Although screening in the PRISMA-ScR process is in three parts, no results remained after completing the first screening part: no self-directed learning (n = 24), no lifespan (n = 5), and no psychological flow (n = 6). As such, the addition of the ProQuest search on 30 October 2025, produced no included studies. They remained (n = 5), with the reports of included studies (n = 6).

Figure 1 depicts the combined search process for both days in the most recent PRISMA 2020 flow diagram [90]. The boxes on the right side present the exclusion criteria flow, with the last box under “Included” on the left specifying the final number included. Those included represent empirical studies in English, published since 2021 in peer-reviewed publications, with information relevant to each of the three keywords. Of interest regarding the Google Scholar experiment is that the final five studies included were all and only from H. Google Scholar. As such, adding any Boolean operators to the Google Scholar search ultimately returned no results for this review after exclusions.

3. Results

The results attend to the relevant sections of the PRISMA-ScR Checklist [90]. They include (1) the characteristics of the sources of evidence, (2) the results of individual sources of evidence, and (3) a synthesis of the results. Identification of the characteristics of the evidence sources is in the subsection on reports of included studies. Two subsections that follow examine the results of individual sources of evidence. One concerns the study details and the other the methodological details. The subsection on topics contains a synthesis of the results.

3.1. Reports of Included Studies

The titles of the five returns describe two types of results: flow regarding lifelong online self-directed learning [91,92,93] and continuing work-related flow through self-directed learning [94,95]. The first title returned 29th in the H. Google Scholar search [92]. The second returned 42nd [93]; the third, 77th [91]; the fourth, 84th [95]; and the fifth, 98th [94]. Two points are evident from the ordinal placement of these results in the returns. The first is that articles concerning online self-directed learning had a higher recall than those with a work-related self-directed learning focus. The implication is that, for lifespan flow, online self-directed learning is most relevant. The second point is that no returns, after the 98th, were included As such, although this review process searched the H. Google Scholar for the first 150 returns, there were likely no relevant articles with a lower recall than might have been included for review.

Those reports on online learning [91,92,93] were also the ones that had multiple authors. In contrast, the two reports about in-person work had a single author [94,95].

The first return [92] was also the only conference submission. It is included here as part of an IEEE (Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers) peer-reviewed publication [96]. IEEE publications are considered to undergo high-quality peer review [97,98] and are deemed a better representation of the industry than journal publications [99]. The topic is viewed from an engineering perspective in this report and in another [91]. The other three reports come from journals focused on psychological considerations [93,94,95].

It is interesting to note that 2022 is the most recent publication regarding this topic—the final year of a Csikszentmihalyi-authored publication following his death in 2021. There are two publications from 2022 [92,95]. The other three were published in 2021 [91,93,94]. See Table 2.

Table 2. Bibliographic details: (1) # (citation number), (2) article title, (3) authors, (4) publication source, and (5) publication year for the 3 August 2025 search of “self-directed learning, lifespan, psychological flow” resulting from the reports included for the appraisal of the database (Google Scholar), listed in the order of the searched returns.

|

# |

Title |

Authors |

Publication Source |

Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

[92] |

Metaverse learning: The relationship among quality of VR-based education, self-determination, and learner satisfaction |

Gim G, Bae H, and Kang S |

2022 IEEE/ACIS 7th International Conference on Big Data, Cloud Computing, and Data Science (BCD) |

2022 |

|

[93] |

Self-directed learning online: An opportunity to binge |

LaTour KA and Noel HN |

Journal of Marketing Education |

2021 |

|

[91] |

Goldilocks conditions for workplace gamification: How narrative persuasion helps manufacturing workers create self-directed behaviors |

Seo K, Fels S, Kang M, Jung C and Ryu H |

Human–Computer Interaction |

2021 |

|

[95] |

Learning at work: Maximizing the potential of lifelong learners at the workplace |

Yusoff A |

Journal of Cognitive Sciences and Human Development |

2022 |

|

[94] |

Jammin’ the Blues: Experiencing the “Good Life” |

Debrot RA |

Frontiers in Psychology |

2021 |

3.2. Study Details

The aims of the five reports are disparate. The focus of the first one [92] is improving a Metaverse platform for lifelong use by encouraging greater online participation through improving self-direction in the learning process. The assumption is that greater satisfaction comes increased flow experience. The aim of [93] contrasts with other studies in that achieving the flow experience through binge self-directed learning through the lifespan is considered detrimental to learning the material taught. As such, one study examined the effect of various forms of binge learning on student grades, while the second study investigated how to direct students away from the flow state with shorter classes. The three remaining publications [91,94,95] all consider flow from the perspective of work through the lifespan, rather than focusing on the psychological perception of personal enjoyment from flow. However, each does so from a different perspective. The first [91] considers whether self-directed behavior applied to learning in Narrative Gamification is more effective in producing flow than, most specifically, performance-focused gamification. The second explored achieving flow in self-directed learning across the lifespan. This was regarding several psychological traits that can improve productivity at work. It was accomplished by meeting company targets through enhancing worker innovation. The third article examining self-directed learning in relation to flow across the lifespan investigated that biographical factors that permit blues/rock musicians to interpret their subjective well-being as connected to the opportunity to jam with other musicians.

The two publications with the highest recall were those with the highest number of participants. The first [92] investigated 535 online users, while the second [93] surveyed 588 students in professional or master’s programs as participants in one study and 99 students from the e-provider in the second. The remaining publications had fewer than 20 participants. Each was specific to a particular type of work. The first of the three [91] studied 18 male Hyundai employees between the ages of 25 and 20; the second [95], the top 5 employees of three organizations—primarily middle managers with 8–10 years of experience; and the third [52], one female and six male musicians.

COVID-19 is known to have affected flow through self-directed learning at various learning levels [66,100]. However, of the five resulting publications, only two were most likely conducted during the COVID-19 [101] pandemic, [92,95]. The first article states that the study was in March 2022. Regarding the second, the assumption is that the research was conducted during the pandemic, as the initial submission date was August 2021. For [94], the study, from December 2019 to January 2020, coincides with the identification of the COVID-19 virus. However, it was before the pandemic was declared [102]. The studies of two other publications either (1) were not conducted during the pandemic [93] (the two studies of this publication were between 2015 and 2019) or (2) likely undertaken before the pandemic, based on their funding approval in 2019 [91].

The locations of the studies were in three areas—South Korea [91,92], the United States [93,94], and Malaysia [95], although location is not directly stated in two of the publications, [92,95]. Unfortunately, these are the two publications conducted during the pandemic, the time period of most relevance to the keywords. See Table 3.

Table 3. Study details (1) # (citation number), (2) study aim, (3) type of participants and their number, (4) study date, and (5) study location for the 3 August 2025 search of “self-directed learning, lifespan, psychological flow” resulting from the reports included for the appraisal of the database (Google Scholar), listed in the order of the searched returns.

|

# |

Study Aim |

Participants |

Study Date |

Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

[92] |

Investigating (1) the quality variables of the Metaverse platform and how they affect learner satisfaction in achieving flow, and (2) how the self-determination of learners affects their flow in relation to user-friendliness and ease of use of the platform |

535 participants with experience in using VR or AR-based educational content |

March 2022 |

South Korea (not stated directly) |

|

[93] |

Study 1: assessing whether students spread out or “binge” their self-directed online learning activity to achieve a flow state, by comparing the impact of different learning schedules on student grades. Study 2: investigating whether shorter classes lead to less self-directed bingeing of material, moving students out of the flow state, as well as how scheduling affects their net promoter status, and the current manner in which the online provider measures satisfaction |

Study 1: 588 students of an Ivy League online professional and master’s course provider Study 2: 99 students of the Study e-provider |

Study 1: 2015 to 2018 consecutively Study 1: Fall 2018 and Spring 2019 |

United States |

|

[91] |

Comparing the self-directed learning of narrative gamification against other gamifications, in particular, performance-focused gamification, to assess the workers’ psychological work perception and flow experience |

18 male workers from Hyundai Motors Company, between the ages of 25 and 30 years |

Not provided: final funding approved in 2019 |

South Korea |

|

[95] |

Investigating whether grit, resilience, and a desire to engage in self-directed learning and re-learning in the flow of work for lifelong learners can improve their productivity, enhance their innovation, and increase their meeting company targets |

Top 5 employees of 3 organizations (n = 15) representing mostly middle managers with 8–10 years working experience. |

Not provided: manuscript received in August 2021 |

Malaysia (not stated directly) |

|

[94] |

Considering (1) in what ways biographical factors and engagement with music influence the lives of older adult blues/rock musicians who participate in a local blues jam, dependent on flow, and (2) the implications for subjective well-being regarding music to inform self-directed music education practices |

Seven musicians, six males and one female. |

December 2019 to January 2020. |

United States |

3.3. Methodological Details

The outcomes of each study differed. The basis of the difference was the learner’s intention regarding their self-directed learning. Moreover, there was a contrast between the type of flow reported and the participant’s lifelong commitment to a flow-producing activity.

For [92], the learning concerned externally derived standards for learner success. The learners’ flow acted as an important mediating variable for learner satisfaction. This result suggests that designing and running a systematic platform that encourages self-directed learning is imperative to support best educational practices regarding the Metaverse. Under these conditions, where the learner did not plan the curriculum, flow was unaffected by the quality of information or the service quality. This result means that, as learners progressed through the Metaverse, the experience rather than the content connected their flow. The authors did not expect that this lack of quality would leave participant flow unaffected. Similarly, in [93], the learner was required to conform to the standardized curriculum expectations. In this case, achieving flow from bingeing on online classes was viewed as an unwanted outcome. This result was especially for those who binged at the end of the course. The reason was that the learner’s focus was on enjoyment rather than learning. Yet, in the second of the two studies for [93], when the effect of shortening the semester was tested regarding reducing bingeing behavior, the change eliminated bingeing during the middle of the course, but not at the beginning or the end. The focus of this article was on reducing the type of flow from online bingeing when engaging in self-directed learning. However, the learners had a successful course outcome regardless of their bingeing. Their attitude towards the course differed. Front bingers were more positive about the learning experience than Back bingers. Unlike the anti-flow message presented in [93], report [91] focused on the type of gamification most likely to create flow in Hyundai Motor Company workers. Of the three types tested (none, Conventional, and Narrative), Narrative Gamification supported the highest productivity and flow state. According to the authors, this dependence of Narrative Gamification on self-directed learning based on intrinsic values is the reason, unlike the other two. This correlation with intrinsic values maintains the flow state throughout the employment period. This flow concentration, particularly during an extended work period, was also the focus of [95]. For the top employees studied at the three corporations, flow was directly tied to the purpose and meaning in their careers. Interestingly, when flow is career-related, as in this study, the self-directed learning must not infringe on the meaning the employee has developed regarding their work. As such, the most effective self-directed learning in this case comes in “bite-sized” modules, rather than extended courses. The final publication [94] also views flow as dependent on a lifelong connection with work—evident when the musician has the opportunity to jam. Here, self-directed learning evolves from the flow achieved. There is a difference concerning the extended flow of top corporate employees and blues/rock musicians. It is that top employees have an intention regarding the direction they want their flow to take them. For the musicians, the flow is accepted for itself and, lifelong, the type of flow experienced is not expected to change.

The study type of four of the five publications [91,92,93,95] is quantitative. One is qualitative [94]. For the quantitative, two studies have measurements taken by the authors—the first of [91,93]. Quantitative assessments of author-administered surveys are found in the second [93] study, [91,92,95]. In contrast, [94] is based on a qualitative interpretation of author-conducted interviews.

The significance of the measures related to distinct variables for each publication. The outcomes were significant for [92] because all variable values were 0.7 or higher. For [93], a likely reason that achieving flow through binge-watching was not encouraged is that the result for those who did not binge (Spacers) was significantly higher than for those who binged. However, Middle-bingers were significantly higher than Spacers post-hoc, but not the Front-bingers. When the length of the course was shortened in the second study of [93], there were significantly more Front-bingers than in the first study. With the period for middle bingeing eliminated, Spacers and Back-bingers were noticeably increased. Although the authors identified Narrative Gamification as the type of gamification that produces flow [91], the difference between Narrative Gamification and Conventional Gamification was not significant when compared with No Gamification. Concerning completion time, there was no difference among the three forms of Gamification. Significance tests were not performed for [95]. However, 78.6% preferred self-directed learning for self-development to be undertaken first thing in the morning, during the commute to work. Representing a qualitative study, there was no test for significance for [94]. See Table 4.

Table 4. Methodological details (1) # (citation number), (2) study outcomes regarding the aim, (3) study type, and (4) whether the results were statistically significant for the 3 August 2025 search of “self-directed learning, lifespan, psychological flow” resulting from the reports included for the appraisal of the database (Google Scholar), listed in the order of the searched returns.

|

# |

Outcomes Regarding Aim |

Study Type |

Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

|

[92] |

Self-determination extensively impacts VR-based education in the Metaverse equally in virtual education compared with online education, but, unexpectedly, the quality of neither information nor service affected flow |

Quantitative, based on a survey on the satisfaction of VR- or AR-based educational content |

Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio value of 0.9 or lower, Cronbach’s Alpha 0.7 or higher, Composite Reliability of 0.7 or higher, and Dijkstra-Henseler rho_A of 0.7 or higher for all variables |

|

[93] |

Study 1: Students in flow state binged their online classes during all quartiles of the semester, not just at the last minute, with back-bingers representing procrastinators, and the front-binge behavior not observed previously in online education. Study 2: The shorter semester did not reduce flow-state binge behavior. Those who may have binged in the middle of the longer semester adjusted their activity either to the front or the back-end of class. Both types of bingers had successful course completion; however, the Front-bingers and Spacers were more positive than Back-bingers about their experience |

Quantitative: Study 1: Each time a student logs into the system, a virtual footprint is recorded Study 2: Post-class net promoter surveys |

Study 1: Back-binge group: significantly lower than other groups; Spacers: significantly higher than bingers. The bingers were not significantly different from one another. Post-hoc, Middle-binge group was significantly higher than the Spacers but not significantly different from the Front-bingers Study 2: significantly more Front-bingers than in Study 1, with a significant difference in more Spacers and more Back-bingers |

|

[91] |

HMC workers managed the three gamified systems differently regarding the gamification that improved their work performance, provided a flow experience and eventually created effective work behaviors; workers with Narrative Gamification had the highest productivity and the highest flow state, succeeding when they did not feel forced to perform system-given goals |

Quantitative: work performance, flow experience, physiological arousal and stress, and video recordings collected with task completion time and accuracy assessed from log data. |

Torque value and accuracy: significant differences in both Narrative Gamification and Conventional Gamification (not statistically different from each other) compared to No Gamification, with no statistical difference in terms of completion time |

|

[95] |

Top employees look for purpose and meaning in the learning that they engage in, towards delivering their tasks and achieving their professional targets with a self-directed learning preference of “bite sized” modules with flow regarding the work schedule, in contrast to the learning. |

Quantitative based on interviews. |

78.6% prefer self-directed learning for self-development and do so in the morning before commuting to work, with a lack of time being the reason it is not always pursued—significance tests not performed |

|

[94] |

The ability to make individual choices about “how to manage one’s life and surrounding world” is considered a key aspect of subjective well-being with jamming engendering feelings of affirmation, accomplishment, and self-acceptance through flow. |

Qualitative, based on semi-structured, open-ended interviews |

Not tested |

3.4. Topics

To consider the common topics of the five publications regarding self-directed learning through the lifespan from the perspective of psychological flow it is helpful to return to the optimal elements of psychological flow: (1) clear goals; (2) instantaneous feedback; (3) an equivalence of skills to challenges; (4) an integration of awareness and action; (5) any distractions from the activity are ignored; (6) failure is not considered an option; (7) no self-consciousness is involved; (8) there is a distortion of time; and (9) the activity itself is the desired end [15]. Interpreting this optimal state regarding self-directed learning throughout the lifespan must correspond to the words of Csikszentmihalyi, “flow makes us feel better in the moment, enabling us to experience the remarkable potential of the body and mind fully functioning in harmony. But what makes flow an even more significant tool is its ability to improve the quality of life in the long run” [14] (p. 63). As such, three topics are derivable from this statement: (1) feeling better in the moment, (2) body and mind are in harmony, and (3) improving the quality of life. The results from each publication are synthesizable regarding these three topics.

The focus of [92] is the ability of flow to sustain the interest of learners in situations where the standards are external. Achieving flow in this instance depends on a connection between self-directed learning and maintaining the flow experience rather than retaining the intended content for learning. In this article, there is no discussion of the importance of harmonizing the body and mind. The lack of concentration on harmonizing the body and mind regarding flow is also in [93]. The authors regret that feeling better in the moment is the outcome of binge learning (although, contrary to the authors’ expectations, academic performance is not affected). What the authors point to is the reduced satisfaction that Back binge learners have with their learning. The implication is that this decreases their quality of life. For both [92][93], there is an emphasis on the negative aspects of flow concerning self-directed learning throughout the lifespan. This emphasis results from the standards learners are to meet not being ones for which they have a personal attachment. Recognizing the importance of developing this type of personal attachment to externally designed goals, [91] identifies the importance of Narrative Gamification. Also, these authors are aware of the importance of all three topics. They find that employees can only feel better in the moment concerning flow if they willingly select to perform system goals. This outcome requires the body and mind working in harmony—something that necessitates the use of narrative regarding gamification. With Narrative Gamification, flow is sustainable in work-related tasks. Unlike the other publications, [95] does not emphasize the aspect of feeling better in the moment regarding flow. This lack of emphasis directly relates to the study of top employees. For these employees, lifespan flow is an experience to maintain. It is maintainable because of a harmonized body and mind resulting from these employees having careers with purpose and meaning. Their self-directed learning must correspond with their values and not interfere with their work schedules. For this reason, they accomplish this learning during their commute to work. Concerning the musicians interviewed [94], their jamming related to flow. Without it, the jam ended. The aim of those interviewed is to find opportunities to jam. Jamming helped them feel better in the moment by harmonizing their body and mind. Through their self-directed learning, they created ways to continue jam sessions—considered by the musicians to be what improves their quality of life. See Table 5

Table 5. Topics created by the author arising from the words of Csikszentmihalyi in [14], on page 63, for synthesizing the results of the five publications reviewed with respect to self-directed learning, lifespan, and psychological flow.

|

# |

Feeling Better in the Moment |

Body and Mind Are in Harmony |

Improving the Quality of Life |

|---|---|---|---|

|

[92] |

Flow acts as an important mediating variable for learner satisfaction |

Not a focus |

Self-directed learning is tied to the flow experience rather than the content when standards are external. |

|

[93] |

Flow encourages bingeing in learning course-related materials |

Not a focus |

Only for Front Bingers of self-directed learning, not Back Bingers |

|

[91] |

Only when employees do not feel forced to perform system goals |

Narrative Gamification encourages such harmony in flow |

Flow can be sustained regarding self-directed learning in work tasks |

|

[95] |

Not a focus |

Body and Mind working together in flow is necessary for excellence |

Self-directed learning relates to purpose and meaning as an employee |

|

[94] |

Relevant to beginning and sustaining a jam session |

Collaboration continues because flow harmonizes the body and mind |

Self-directed learning relates to creating the time to engage in jams |

Regarding the hypothesis—that distinct topics are recognizable through this type of limited review concerning relationships among self-directed learning, psychological flow, and lifespan, regarding how self-directed learning promotes psychological flow throughout the lifespan—the relationship among these variables can be interpreted. Psychological flow helps self-directed learners feel better in the moment while simultaneously permitting a harmonious body and mind. By accomplishing both, the individual’s quality of life improves to be sustainable throughout the lifespan. For the relationship of the three topics of Feeling better in the moment, Body and mind in harmony, and Improving the quality of life, for each of the five studies. Based on the synthesis, the level of meaning the learner ascribes to their work determines the relationship among the three keywords.

4. Discussion

According to a statement by Csikszentmihalyi published at the end of his life, in 2021, “Entering into the state of flow, respondents described it as one of intense concentration in which they tended to lose self-consciousness. Some of the other key features of this state include having a sense of being in control of their actions, the sensation that time is distorting, and a sense that the experience was its own reward” [103] (p. 196). This comment by Csikszentmihalyi coincides with his early career findings [2]. This review has demonstrated that these features of flow are more than personally relevant regarding self-directed learning throughout the lifespan; they also have a social component.

In both [92][93], the positive social value of flow about self-directed learning throughout the lifespan is questioned. Those experiencing flow lose interest in social expectations. Their self-directed learning connects to the flow experience rather than the prescribed content they are to learn—a result of their loss of self-consciousness, the control of their actions, their distorted sense of time, and the experience being the reward [92]. Bingeing becomes the preferred self-directed learning method when there is a requirement to learn prescribed course-related material. Those who “Back binge” (binge at the course end) express reduced positive attitudes towards their learning compared with those who space out their learning to coincide with the curriculum throughout the lifespan, although this bingeing does not appear to affect academic results.

However, identified social problems appear to result from the learner lacking the ability to truly self-direct their learning. In [91,94,95], the value of flow to sustaining a career and encouraging innovation is the focus. Recognizing the narrative is relevant to maintaining flow [91], that flow can relate to an entire career [95], and that creativity in flow guides self-directed learning [94] demonstrates that, if social interests work in concert with flow, that flow is not only personally satisfying throughout the lifespan—it is productive socially.

An earlier publication by the author examining psychological flow in athletes, musicians, and researchers [46] noted that flow for athletes and musicians most often was evident during an evaluated skills performance. In contrast, researchers might maintain flow throughout the entire period of their investigation. For them, presenting their work at a conference is unlikely to produce a flow experience. The relationship of flow to athletes and musicians over the lifespan contrasts with that of researchers in this limited review. For athletes and musicians, their flow through self-directed learning is related to opportunities to perform throughout their life—a point reinforced by [94]. However, for researchers, flow throughout the lifespan relates to self-directed learning regarding their research program. Similarly top executives, they experience flow when their employment purpose and meaning correspond with self-directed learning [95]. For top researchers, flow and self-directed learning can be a continuous process throughout the lifespan [68]. This difference between the lifespan flow of athletes and musicians compared to that of researchers has been differentiated as external flow versus internal flow [104]. Contrary to social concerns about flow and inattention, a 2019 study of external and internal flow found a negative relationship between flow and inattention, and people who experience flow more frequently appear to demonstrate relatively less inattention in everyday contexts.

An additional consideration is whether self-directed learning regarding flow throughout the lifespan is similar to the hyperfocus associated with ADHD [74,75] or autism [76]. From this perspective, hyperfocus is detrimental to social functioning, while psychological flow is considered favorable [76]. However, recent research has questioned this association between flow and hyperfocus. Results suggest that hyperfocus and flow are distinct, inversely related constructs, or that the investigation methods influence different accounts of their task absorption experiences [105].

4.1. Triangulation

Various methods study the same phenomena with triangulation [106]. The purpose is to overcome research bias and validity problems [107], increasing confidence in the findings [108]. The four recognized means of triangulation are: (1) method triangulation, (2) investigator triangulation, (3) theory triangulation, and (4) data source triangulation [106,107,109]. However, different terminology regarding triangulation complicates its understanding [110]. This study achieved triangulation in various ways.

By following the PRISMA-ScR, there is one method. Therefore, achieving method triangulation is possible with a supplementary file (Supplementary S1) listing the returned results from each search in the order of their return. This file permits method accuracy assessment. As such, although the investigation is by a sole researcher, the results can be reviewed by any other researcher. Comparison of psychological flow with self-determination theory [37], and with the hyperfocus associated with ADHD [111,112] or autism [113], achieves theoretical triangulation. Searching seven primary databases relevant to the topic and one supplementary database in eight different ways achieves data source triangulation. Without extending the search to Google Scholar, there would have been no relevant results for this review.

4.2. Limitations

There were no returns on this topic from several primary database searches (Embase, Medline, PubMed, and Scopus)—representing an unexpected result. Keyword bias could be the reason. Generating and comparing keywords after reading articles is identified as an effective means to enhance the relative accuracy of keywords [114]. Using this method was not part of this search, as APA PsycArticles®, Web of Science, and ProQuest—the other primary databases—produced results. Therefore, it is unlikely that a gap in the field is the cause for the lack of returns from Embase, Medline, PubMed, and Scopus. In such cases, the advice is to search the supplementary database Google Scholar [115]. Employing this method was productive. Nevertheless, without Embase, Medline, PubMed, and Scopus as primary databases in the included reports, the expected comprehensiveness is reduced. However, the reason for these primary databases producing no returns may be that the search engine is more precise in including scoped articles. Although APA PsycArticles®, Web of Science, and ProQuest returned results, ultimately, none were included.

Another reason these primary databases produced no results may be that they were not the relevant databases to select. The focus of two of the publications Google Scholar returned was engineering rather than health. As such, health databases were irrelevant to their search. That an engineering database was relevant for searching self-directed learning, lifespan, and psychological flow had not been considered. That the suitability of searching engineering databases, such as IEEE Xplore, Engineering Village [116], or Compendex [117], was not recognized represents a limitation. Nevertheless, an after-the-fact test search of these databases also returned no results.

One researcher alone completed the searches. Conducting research without a team may lead to cognitive bias [118]. Two steps counteract possible cognitive bias: (1) PRISMA-ScR procedures for scoping review [119] were followed, and (2) a supplementary file of all searches that produced returns was created. This file is Supplementary S1. It provides information on all the returns for the primary databases, the first 150 results for H. Google Scholar, and the additional unique returns from the other A.-G. Google Scholar searches.

This review of recent publications with high recall in the style of a scoping review analyzes five studies and six reports. The paucity of studies from this approach limits the empirical depth and generalizability of the analysis. The consequence is that, rather than empirical, this work is primarily a conceptual and methodological contribution that lacks sufficient in-depth scientific analysis. The empirical quality of this study is also limited by not being a complete scoping review nor a systematic review and meta-analysis [98,99]. Therefore, the study is missing a deeper critical evaluation of its quality and methodological rigor. A scoping review would include all relevant publications of any kind written at any date [81]. As the focus was on investigating those publications regarding this topic since the death of Csikszentmihalyi in 2021 [1]—providing the most promising research directions—it does not a systematic review and meta-analysis would include an evaluation of the sample sizes [120] and an assessment of the validity of the measurement tools [121]. Since this work is not a systematic review and meta-analysis, it does not. In following the advice on when to undertake a scoping review [122,123], the aim of this review precluded following the PRISMA guidelines for systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

An additional limitation of the reports included is that none comprehensively addresses self-directed learning, psychological flow, and lifespan development simultaneously. Moreover, doing so is not the intent of the publication. Instead, the author examined the articles for the points made about the three topics and their relationships. As such, if the authors of the included reports had intended to investigate the three topics comprehensively, the results might have differed. Regarding the relationship among the three subjects, the authors’ intentions are unknown. This lack of knowledge is a limitation.

A final limitation is that, although each empirical study should include all relevant keywords, [92] did not include “self-directed learning” as a distinct concept. Instead, [91] concerns “self-directed behaviors”, of which “learning” was a focus. Since the article effectively examines self-direction as a concept, [91] was not excluded. However, not mentioning this keyword specifically is a limitation.

4.3. Future Research Directions

As the first work to consider flow and self-directed learning throughout the lifespan, there is room for substantial research in this area. A first attempt, an investigation of the most recent literature with high recall on self-directed learning and psychological flow throughout the lifespan, is the practical value of this work. With a wide selection of databases for this undertaking, this initial attempt offers a comprehensive foundation for fruitful research directions, a full scoping review, and a future systematic review and meta-analysis of the topic.

In undertaking this study, the assumption was that lifetime changes affect psychological flow and self-directed learning. The basis of this assumption was that people change physiologically [58,59], psychologically [60,61], and in their intentions [62,63] over their lifetime. Future research should investigate this assumption from three perspectives: changes to physiology, psychology, and personal intentions regarding self-directed learning, along with the concept of psychological flow.

The returns demonstrated that online self-directed learning is most relevant for flow through the lifespan. Based on this result, a topic for future research is the value of online self-directed learning to achieving and maintaining flow throughout the lifespan. Since those reports on online learning [86,87,88] had multiple authors, an added area to research in this regard is the optimal number of authors for such an investigation. Also to be considered when assessing the role of self-directed online learning for promoting psychological flow throughout the lifespan is the role of COVID-19 [66].

The included studies were all published in 2021 or 2022. The last co-authored paper of Csikszentmihalyi was in 2022, following his death [64]. Another area that might produce fruitful research is investigating the relevance of Csikszentmihalyi as a current researcher to continuing research on all aspects of psychological flow. The purpose would be to evaluate the effect of Csikszentmihalyi’s consistent publications throughout his life on interest in this topic and whether, with his death, the interest subsides.

When Csikszentmihalyi and his associates investigated flow throughout the lifespan, they did so without considering self-directed learning [64]. Their focus was on changes to flow and human physiology over time. That a decline in functional capacity does not prohibit the experience of flow was their conclusion. Flow-inducing activities can be engaged in by readjusting skills, reducing challenges, or reinvesting time in other flow-conducive activities. This limited review has examined flow from a different perspective. Here, the focus was on the value of self-directed learning regarding flow within a social context. Before this review, research on flow has concentrated on the personal value of flow. Additional research is needed to examine flow from a social context, including its possible relationship to hyperfocus [111,112,113].

The finding that the two publications with the highest recall were those with the most participants points to the need for additional studies on the relationship among self-directed learning, psychological flow, and lifespan that include a large number of participants. This level of research would improve the validity and recall level of the studies in database searches.

The studies that mentioned their location were in three areas—South Korea [91,92], the United States [93,94], and Malaysia [95]. Given that these are all highly developed countries, there is significant room for cross-cultural comparisons in online self-directed learning, particularly with countries that lack consistent internet access [124].

The type of flow reported was in contrast to the participant’s lifelong commitment to the activity that produces flow. Another area for future research is evaluating commitment to achieving psychological flow in relation to the number of flow activities reported throughout the lifespan when engaged in self-directed learning.

Four of the five publications [91,92,93,95] were quantitative, one was qualitative [94]. More quantitative research is necessary for improved data reliability, accuracy, integrity, and veracity. However, equally valuable is additional qualitative research. This necessity is especially so as various reliable measures of psychological flow—structured [16] or semi-structured interviews [17,18]—are qualitative. Similarly, so are those measuring self-directed learning: self-assessment [55], process evaluation [56], and assessing the content and structure of learning activities [57].

Research concerning the three topics mentioned by Csikszentmihalyi, identified in the five publications, would be valuable. These topics are (1) feeling better in the moment, (2) body and mind are in harmony, and (3) improving the quality of life. The evolution of feeling better in the moment with flow, from self-directed learning throughout the lifespan, represents one area of relevant research. How the body and mind function harmoniously with self-directed learning through the lifespan when flow is evident is another research topic. By maintaining flow through self-directed learning, the third is investigating the possibility of improved lifespan quality. These are examples of research questions that may be productive for the three topics.

Theoretically, the three topics focus on two aspects of psychological flow—feeling better in the moment, and the body and mind acting in harmony—to work in conjunction with self-directed learning, and together they serve to improve the quality of life. This improved quality of life is then possibly maintainable throughout the life span. What this relationship does not explain is how often a person must experience psychological flow for any improvement in their quality of life. Future research is necessary to answer this question. Perhaps it is required to experience psychological flow at meaningful periods in life—another point to be studied. Moreover, although psychological flow may depend on self-directed learning, it is unknown if experiencing psychological flow is necessary to promote the type of self-directed learning that leads to an improved quality of life. Future investigations should also consider when it matters that learning be self-directed to support a better quality of life. Whether self-chosen other-directed learning can support and improve quality of life throughout the lifespan in a manner comparable to self-directed learning involving psychological flow is to be identified.

Google Scholar was the only database returning relevant results for this review. Therefore, investigating its relegation to a secondary database supports a previous suggestion, made earlier this year for the same reason [89]. Please see the detailed analysis of the matter in that work.

5. Conclusions

This limited review followed the PRISMA-ScR process. It aimed to identify (1) high recall, (2) high precision, (3) empirical research studies, (4) written in English, (5) in peer-reviewed publications, and (6) representing the most promising research directions by topic. The hypothesis was that distinct topics would be evident from this limited review of the relationships among self-directed learning, psychological flow, and lifespan. How they would be apparent is through the promotion of psychological flow throughout the lifespan with self-directed learning. Returned were five relevant studies representing six reports with disparate themes regarding the three keywords from the database searches.

Self-directed online learning for achieving psychological flow throughout the lifespan was a significant theme. From these results, corroborating the hypothesis, three Csikszentmihalyi-inspired topics were relevant: (1) feeling better in the moment, (2) body and mind are in harmony, and (3) improving the quality of life. The finding was that psychological flow helps self-directed learners feel better in the moment. It did so while also permitting their body and mind to act harmoniously. Accomplishing both provides an improved quality of life that is sustainable throughout the lifespan. Although the results were small in number, the topics point to new areas of research regarding psychological flow. These topics provide the basis of several possible avenues of future research. A fundamental research area in this regard would distinguish psychological flow from hyperfocus regarding self-directed learning throughout the lifespan. As the first review of empirical research regarding the relationship among self-directed learning, psychological flow, and lifespan, this work is valuable.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be found at: https://www.sciepublish.com/article/pii/756, Supplementary S1: Results of the database searches of 3 August 2025, and 30 October 2025, of the keywords “self-directed learning AND lifespan AND psychological flow”.

Ethics Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data are in Supplementary S1.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The author has no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

-

Zuzanek J. Tribute to Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi (1934–2021). Loisir et Société/Soc. Leis. 2022, 45, 445–447. doi:10.1080/07053436.2022.2097392. [Google Scholar]

-

Csikszentmihalyi M. Beyond Boredom and Anxiety, 1st ed.; The Jossey-Bass Behavioral Science Series; Jossey-Bass Publishers: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1975; ISBN 978-0-87589-261-0. [Google Scholar]

-

Heutte J, Fenouillet F, Martin-Krumm C, Gute G, Raes A, Gute D, et al. Optimal Experience in Adult Learning: Conception and Validation of the Flow in Education Scale (EduFlow-2). Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 828027. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.828027. [Google Scholar]

-

Abuhamdeh S. Investigating the “Flow” Experience: Key Conceptual and Operational Issues. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 158. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00158. [Google Scholar]

-

Zhang Y, Wang F. Developments and Trends in Flow Research Over 40 Years: A Bibliometric Analysis. Collabra Psychol. 2024, 10, 92948. doi:10.1525/collabra.92948. [Google Scholar]

-

Abuhamdeh S. On the Relationship Between Flow and Enjoyment. In Advances in Flow Research; Peifer C, Engeser S, Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 155–169; ISBN 978-3-030-53467-7. [Google Scholar]

-

Csikszentmihalyi M. Play and Intrinsic Rewards. J. Humanist. Psychol. 1975, 15, 41–63. doi:10.1177/002216787501500306. [Google Scholar]

-

Csikszentmihalyi M. Play and Intrinsic Rewards. In Flow and the Foundations of Positive Psychology; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 135–153; ISBN 978-94-017-9087-1. [Google Scholar]

-

Csikszentmihalyi M. A Theoretical Model for Enjoyment. In The Improvisation Studies Reader: Spontaneous Acts; Heble A, Caines R, Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2014; pp. 150–162; ISBN 978-0-203-08374-1. [Google Scholar]

-

Csikszentmihalyi M, Montijo MN, Mouton AR. Flow Theory: Optimizing Elite Performance in the Creative Realm. In APA Handbook of Giftedness and Talent; Pfeiffer SI, Shaunessy-Dedrick E, Foley-Nicpon M, Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2018; pp. 215–229; ISBN 978-1-4338-2696-2. [Google Scholar]

-

Csikszentmihalyi M, Rich G. Musical Improvisation: A Systems Approach. In Creativity in Performance; Sawyer RK, Ed.; Publications in Creativity Research; Ablex: London, UK, 1997; pp. 43–66; ISBN 978-1-56750-336-4. [Google Scholar]

-

Legaard JF. The Wonder of Play. Int. J. Play 2023, 12, 375–386. doi:10.1080/21594937.2023.2239562. [Google Scholar]

-

Peifer C, Wolters G, Harmat L, Heutte J, Tan J, Freire T, et al. A Scoping Review of Flow Research. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 815665. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.815665. [Google Scholar]

-

Csikszentmihalyi M. Good Business: Leadership, Flow, and the Making of Meaning; Viking: New York, NY, USA, 2003; ISBN 978-0-670-03196-2. [Google Scholar]

-

Csikszentmihalyi M. Creativity: Flow and the Psychology of Discovery and Invention, 1st ed.; HarperCollins Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 1996; ISBN 978-0-06-017133-9. [Google Scholar]

-

Swann C. Flow in Sport. In Flow Experience; Harmat L, Ørsted Andersen F, Ullén F, Wright J, Sadlo G, Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 51–64; ISBN 978-3-319-28632-7. [Google Scholar]

-

Clapp SR, Karwowski W, Hancock PA. Simplicity and Predictability: A Phenomenological Study of Psychological Flow in Transactional Workers. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1137930. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1137930. [Google Scholar]

-

Łucznik K, May J, Redding E. A Qualitative Investigation of Flow Experience in Group Creativity. Res. Danc. Educ. 2021, 22, 190–209. doi:10.1080/14647893.2020.1746259. [Google Scholar]

-

Jackson SA, Marsh HW. Development and Validation of a Scale to Measure Optimal Experience: The Flow State Scale. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 1996, 18, 17–35. doi:10.1123/jsep.18.1.17. [Google Scholar]

-

Józefowicz J, Kowalczyk-Grębska N, Brzezicka A. Validation of Polish Version of Dispositional Flow Scale-2 and Flow State Scale-2 Questionnaires. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 818036. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.818036. [Google Scholar]

-

Garcia WF, Nascimento Junior JRA, Mizoguchi MV, Brandão MRF, Fiorese L. Transcultural Adaptation and Psychometric Support for a Brazilian Portuguese Version of the Flow State Scale (FSS-2). Percept. Mot. Ski. 2022, 129, 800–815. doi:10.1177/00315125221093917. [Google Scholar]

-

Kawabata M, Mallett CJ, Jackson SA. The Flow State Scale-2 and Dispositional Flow Scale-2: Examination of Factorial Validity and Reliability for Japanese Adults. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2008, 9, 465–485. doi:10.1016/j.psychsport.2007.05.005. [Google Scholar]

-

Lee-Shi J, Ley RG. A Critique of the Dispositional Flow Scale-2 (DFS-2) and Flow State Scale-2 (FSS-2). Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 992813. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.992813. [Google Scholar]

-

Huang L-J, Hu F-C, Wu C, Yang Y-H, Lee S-C, Huang H-C, et al. Are the Measurement Structures of the Traditional Chinese Dispositional Flow Scale-2 Equivalent between Schizophrenic Patients and Healthy Subjects? J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 2022, 121, 1981–1992. doi:10.1016/j.jfma.2022.02.004. [Google Scholar]

-

Bittencourt II, Freires L, Lu Y, Challco GC, Fernandes S, Coelho J, et al. Validation and Psychometric Properties of the Brazilian-Portuguese Dispositional Flow Scale 2 (DFS-BR). PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0253044. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0253044. [Google Scholar]

-

Gross T, Malzhacker T. The Experience Sampling Method and Its Tools: A Review for Developers, Study Administrators, and Participants. Proc. ACM Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2023, 7, 1–29. doi:10.1145/3593234. [Google Scholar]

-

Peifer C, Engeser S. Theoretical Integration and Future Lines of Flow Research. In Advances in Flow Research; Peifer C, Engeser S, Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 417–439; ISBN 978-3-030-53467-7. [Google Scholar]

-

Rácz M, Becske M, Magyaródi T, Kitta G, Szuromi M, Márton G. Physiological Assessment of the Psychological Flow State Using Wearable Devices. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 11839. doi:10.1038/s41598-025-95647-x. [Google Scholar]

-

Ulrich M, Niemann F, Grön G. The Neural Signatures of the Psychological Construct “Flow”: A Replication Study. Neuroimage Rep. 2022, 2, 100139. doi:10.1016/j.ynirp.2022.100139. [Google Scholar]

-

Norsworthy C, Jackson B, Dimmock JA. Advancing Our Understanding of Psychological Flow: A Scoping Review of Conceptualizations, Measurements, and Applications. Psychol. Bull. 2021, 147, 806–827. doi:10.1037/bul0000337. [Google Scholar]

-

Jamalipournokandeh O, Hori J, Asakawa K, Yana K. Dispositional Flow and Related Psychological Measures Associated with Heart Rate Diurnal Rhythm. Adv. Biomed. Eng. 2023, 12, 9–20. doi:10.14326/abe.12.9. [Google Scholar]

-

Wonders M, Hodgson D, Whitton N. Measuring Flow: Refining Research Protocols That Integrate Physiological and Psychological Approaches. Hum. Behav. Emerg. Technol. 2025, 2025, 6464984. doi:10.1155/hbe2/6464984. [Google Scholar]

-

Nakamura J, Csikszentmihalyi M. The Concept of Flow. In Flow and the Foundations of Positive Psychology; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 239–263; ISBN 978-94-017-9087-1. [Google Scholar]

-

Lemmetty S, Collin K. Self-Direction. In The Palgrave Encyclopedia of the Possible; Glăveanu VP, Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 1456–1462; ISBN 978-3-030-90912-3. [Google Scholar]

-

Kooiman TJM, Dijkstra A, Kooy A, Dotinga A, Van Der Schans CP, De Groot M. The Role of Self-Regulation in the Effect of Self-Tracking of Physical Activity and Weight on BMI. J. Technol. Behav. Sci. 2020, 5, 206–214. doi:10.1007/s41347-020-00127-w. [Google Scholar]

-

AlShamsi A. Perspective Chapter: Performance-Based Assessment through Inquiry-Based Learning. In Education and Human Development; Waller L, Kay Waller S, Eds.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2023; Volume 6; ISBN 978-0-85014-243-3. [Google Scholar]

-

Deci EL, Ryan RM. The “What” and “Why” of Goal Pursuits: Human Needs and the Self-Determination of Behavior. Psychol. Inq. 2000, 11, 227–268. doi:10.1207/s15327965pli1104_01. [Google Scholar]

-

Deci EL, Ryan RM. Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior; Perspectives in Social Psychology; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1985; ISBN 978-0-306-42022-1. [Google Scholar]

-

Nguyen TC, Tran Huy P. Value and Appraisal: Human Resource Management Practices and Voice Behaviors. Manag. Decis. 2025, 63, 1657–1673. doi:10.1108/MD-05-2024-1062. [Google Scholar]

-

Colomer J, Serra T, Gras ME, Cañabate D. Longitudinal Self-Directed Competence Development of University Students through Self-Reflection. Reflective Pract. 2021, 22, 727–740. doi:10.1080/14623943.2021.1964947. [Google Scholar]

-

Van Doorn JR, Raz CJ. Leader Motivation Identification: Relationships with Goal-Directed Values, Self-Esteem, Self-Concept Clarity, and Self-Regulation. Front. Organ. Psychol. 2023, 1, 1241132. doi:10.3389/forgp.2023.1241132. [Google Scholar]

-

De Vries A, Tiemens B, Cillessen L, Hutschemaekers G. Construction and Validation of a Self-direction Measure for Mental Health Care. J. Clin. Psychol. 2021, 77, 1371–1383. doi:10.1002/jclp.23091. [Google Scholar]

-

Baber H, Deepa V, Elrehail H, Poulin M, Mir FA. Self-Directed Learning Motivational Drivers of Working Professionals: Confirmatory Factor Models. High. Educ. Ski. Work.-Based Learn. 2023, 13, 625–642. doi:10.1108/HESWBL-04-2023-0085. [Google Scholar]

-

Liu B, Wu Y, Shu H, Cui Y, Zuo C, Li W. Uncovering the Predictive Effect of Behaviours on Self-directed Learning Ability. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2024, 55, 1231–1252. doi:10.1111/bjet.13427. [Google Scholar]

-

Nash C. Towards Optimal Health Through Boredom Aversion Based on Experiencing Psychological Flow in a Self-Directed Exercise Regime—A Scoping Review of Recent Research. Sports 2025, 13, 161. doi:10.3390/sports13060161. [Google Scholar]

-

Nash C. Self-Directed Learning and Psychological Flow Regarding the Differences Among Athletes, Musicians, and Researchers. Psychol. Int. 2025, 7, 20. doi:10.3390/psycholint7010020. [Google Scholar]

-

Sun W, Hong J-C, Dong Y, Huang Y, Fu Q. Self-Directed Learning Predicts Online Learning Engagement in Higher Education Mediated by Perceived Value of Knowing Learning Goals. Asia-Pac. Educ. Res. 2023, 32, 307–316. doi:10.1007/s40299-022-00653-6. [Google Scholar]

-

van Woezik TET, Koksma JJJ, Reuzel RPB, Jaarsma DC, van der Wilt GJ. There Is More than ‘I’ in Self-Directed Learning: An Exploration of Self-Directed Learning in Teams of Undergraduate Students. Med. Teach. 2021, 43, 590–598. doi:10.1080/0142159X.2021.1885637. [Google Scholar]

-

Woon CP, Tee MY. Navigating Self-Directed Learning: Interaction between Internal and External Structures in Different Self-Directed Learning Contexts. OTH 2025, 33, 378–395. doi:10.1108/OTH-12-2024-0089. [Google Scholar]

-

Lim YS, Willey JM. Evaluation and Refinement of Self-Directed Learning Readiness Scale for Medical Students. Korean J. Med. Educ. 2024, 36, 175–188. doi:10.3946/kjme.2024.294. [Google Scholar]

-

Durr R, Guglielmino LM, Guglielmino PJ. Self-directed Learning Readiness and Occupational Categories. Hum. Resour. Dev. Q. 1996, 7, 349–358. doi:10.1002/hrdq.3920070406. [Google Scholar]

-

Onsawarng T, Wongdee P, Pinit P. Self-Rating Scale in Self-Directed Learning in Workplace Context: A Case Study of Thai Operational Employees in the Petrochemical Plant Industry. High. Educ. Ski. Work.-Based Learn. 2024, 15, 452–463. doi:10.1108/HESWBL-08-2024-0219. [Google Scholar]

-

Lo AWT. Students’ Self-Regulatory Processes in Content and Language Integrated Learning: A Vignette-Based Microanalytic Study. Int. J. Biling. Educ. Biling. 2025, 28, 19–35. doi:10.1080/13670050.2024.2384414. [Google Scholar]

-

Cleary TJ. Emergence of Self-Regulated Learning Microanalysis: Historical Overview, Essential Features, and Implications for Research and Practice. In Handbook of Self-Regulation of Learning and Performance; Zimmerman BJ, Schunk DH, Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 329–345; ISBN 978-0-415-87111-2. [Google Scholar]

-

Lubbe A, Mentz E, Olivier J, Jacobson TE, Mackey TP, Chahine IC, et al. Learning Through Assessment: An Approach Towards Self-Directed Learning; Mentz E, Lubbe A, Eds.; NWU Self-Directed Learning Series; AOSIS: New York, NY, USA, 2021; Volume 7; ISBN 978-1-77634-163-4. [Google Scholar]

-

Balkheyour AA, Tombs M. Evaluation of Self-Directed Learning Activities at King Abdulaziz University: A Qualitative Study of Faculty Perceptions. Cureus 2025, 17, e87353. doi:10.7759/cureus.87353. [Google Scholar]

-

Chukwunemerem OP. Lessons from Self-Directed Learning Activities and Helping University Students Think Critically. J. Educ. Learn. 2023, 12, 79. doi:10.5539/jel.v12n2p79. [Google Scholar]

-

Westerbeek H, Eime R. The Physical Activity and Sport Participation Framework—A Policy Model Toward Being Physically Active Across the Lifespan. Front. Sports Act. Living 2021, 3, 608593. doi:10.3389/fspor.2021.608593. [Google Scholar]

-

Briand M, Raffin J, Gonzalez-Bautista E, Ritz P, Abellan Van Kan G, Pillard F, et al. Body Composition and Aging: Cross-Sectional Results from the INSPIRE Study in People 20 to 93 Years Old. GeroScience 2024, 47, 863–875. doi:10.1007/s11357-024-01245-6. [Google Scholar]

-

Oishi S, Westgate EC. A Psychologically Rich Life: Beyond Happiness and Meaning. Psychol. Rev. 2022, 129, 790–811. doi:10.1037/rev0000317. [Google Scholar]

-

Smeeth D, Beck S, Karam EG, Pluess M. The Role of Epigenetics in Psychological Resilience. Lancet Psychiatry 2021, 8, 620–629. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30515-0. [Google Scholar]

-

Dorris L, Young D, Barlow J, Byrne K, Hoyle R. Cognitive Empathy across the Lifespan. Dev. Med. Child. Neuro 2023, 64, 1524–1531. doi:10.1111/dmcn.15602. [Google Scholar]

-

Gilbert SJ, Boldt A, Sachdeva C, Scarampi C, Tsai P-C. Outsourcing Memory to External Tools: A Review of ‘Intention Offloading. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 2023, 30, 60–76. doi:10.3758/s13423-022-02139-4. [Google Scholar]

-

Tse DCK, Nakamura J, Csikszentmihalyi M. Flow Experiences Across Adulthood: Preliminary Findings on the Continuity Hypothesis. J. Happiness Stud. 2022, 23, 2517–2540. doi:10.1007/s10902-022-00514-5. [Google Scholar]

-