Adaptive Time Management: A Life-History Framework Integrating Mental Time Travel, Mortality Awareness, and Anticipatory Decision-Making

Received: 31 July 2025 Revised: 17 September 2025 Accepted: 20 October 2025 Published: 23 October 2025

© 2025 The authors. This is an open access article under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

1. Introduction

Throughout the lifespan, autonoetic consciousness enables individuals to project the self through time, weaving past experiences, present awareness, and imagined futures into coherent personal narratives [1,2], which positions humans as highly effective managers of time. Rather than being paralyzed by the shadow of death, people often accept personal risks to safeguard the well-being of future generations [3]. This tendency illustrates that mortality awareness can motivate purposeful, fitness-enhancing decisions rather than merely eliciting fear and defensive reactions [4,5,6].

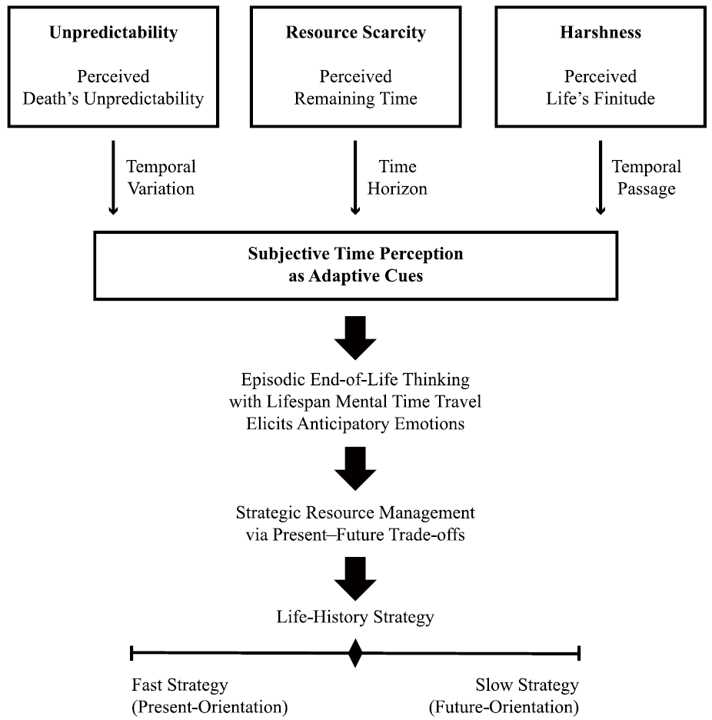

Building on life-history theory [7], we introduce the adaptive time management framework to describe how individuals allocate their finite time along a fast–slow life-strategy continuum. Fast strategies emphasize immediate needs and short-term goals, whereas slow strategies focus on long-term planning and future investment [8,9]. By integrating subjective time perception with episodic future thinking and mental time travel toward life’s endpoint, our framework illustrates how shifts in temporal focus may shape present–future trade-offs and support emotion regulation. Although previous research on mortality cues has often emphasized their adverse consequences (e.g., anxiety, fear, and terror) [10,11,12], the adaptive time management framework underscores their potential adaptive functions [13,14,15].

Terror management theory remains a dominant account of death awareness in social psychology. According to terror management theory, mortality salience (i.e., the activation of thoughts about unavoidable death) elicits existential anxiety that can undermine adaptive functioning if left unchecked [16,17]. Individuals manage this anxiety through proximal defenses (e.g., denial, invulnerability) and subsequently through distal defenses (e.g., worldview affirmation, self-esteem bolstering) to restore psychological equilibrium [18,19]. While these responses capture an important facet of human reactions to mortality, they conceptualize death primarily as a threat to be suppressed rather than as a potential catalyst for strategic adaptation.

In contrast, our adaptive time management framework views mortality cues as dynamic signals that help recalibrate temporal focus and mobilize proactive trade-offs [13,14,15]. Temporal focus, the degree to which attention is directed toward past, present, or future events [20], shifts in response to perceived time horizons. Socioemotional selectivity theory provides a clear example: as perceived remaining time diminishes in older adulthood, goals shift from future planning toward present-oriented emotional fulfillment [21,22,23]. Our recent meta-analysis indicates a U-shaped pattern in present–future preferences across the lifespan, with an inflection point around age fifty. This finding underscores the adaptiveness of shifting temporal focus and suggests a three-way trade-off among mortality, fertility, and parental needs over the life course [24].

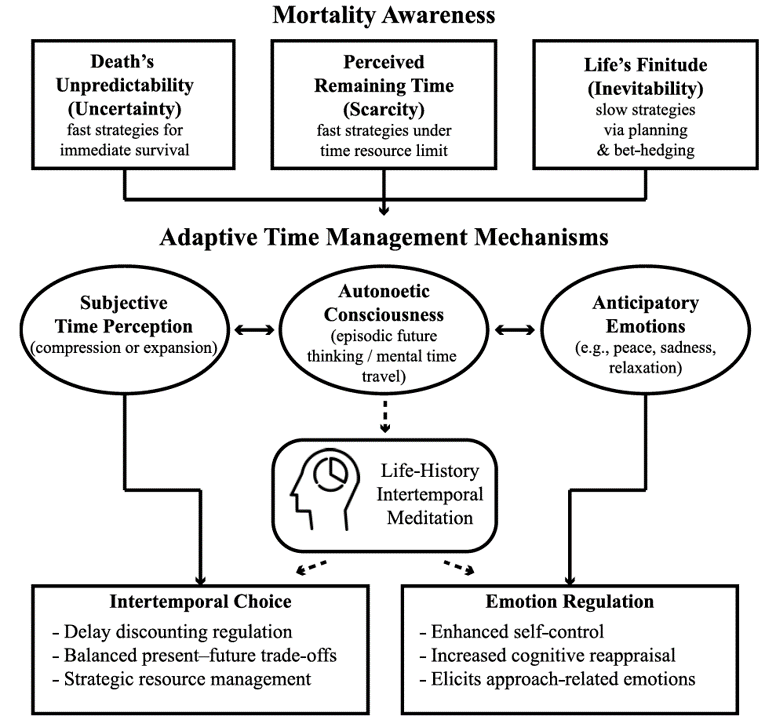

Based on life-history theory, three ecological factors are proposed to shape strategy selection: resource scarcity, unpredictability, and harshness [7]. Within the adaptive time management framework, these ecological factors correspond to three decision premises: perceived remaining time (scarcity), perceived unpredictability of death (unpredictability), and perceived inevitability of death or finitude of life (harshness). Accordingly, mortality cues emphasize two complementary dimensions: the stochastic timing of death (temporal uncertainty) and the limited lifespan (death’s inevitability).

First, resource scarcity also implies time scarcity, as time is a major resource, like money. Time scarcity tends to shorten perceived remaining time and alter subjective time perception: a constricted horizon can make time feel accelerated and prompt present-oriented, fast strategies, whereas an extended horizon can make time feel slower and facilitate future-oriented, slow strategies. Scarcity narrows individuals’ attentional focus, and, by the same token, perceived time scarcity biases their intertemporal choices toward the present. In one behavioral experiment, participants who imagined living on an extremely tight monthly budget (i.e., reduced perceived remaining time) exhibited significantly steeper delay discounting, choosing smaller immediate payoffs over larger delayed rewards [25]. A higher discounting rate reflects a stronger preference for immediate benefits, whereas a lower rate indicates a greater willingness to wait for delayed rewards. The strategic shift toward higher discounting helps ensure that, under genuine resource constraints, urgent needs are met first [7].

Second, the perceived unpredictability of death shapes strategic present orientation. The temporal variation of the endpoint of life highlights the value of more immediate rewards and resource allocation. Rather than being paralyzed by death anxiety, death unpredictability motivates present-oriented choices to secure day-to-day safety under risk. In contexts of elevated uncertainty, forgoing immediate rewards may entail steep survival costs [7]. For example, many animals forage in ways that maximize immediate energetic returns under environmental constraints [26,27,28]. Similarly, when confronted with salient reminders of mortality, humans often prioritize meeting minimum survival needs before allocating resources toward future investments [29].

Third, in life-history theory, harshness is often indexed by mortality rate, which shapes the perception of life’s finitude and directs attention to the inevitability of death, shifting temporal focus toward the interval between the present and life’s end. Thus, the reminders of death’s inevitability and the finitude of life may engage individuals in mental time travel, simulate future scenarios, and prepare them for contingencies. As a result, it fosters future-oriented decisions and activates slow life-strategies for resource reservation. Episodic future thinking, activated by vivid mortality imagery or mortality salience, can generate anticipatory emotions that serve as signals in allocating resources toward future needs [2,30,31]. Unlike reactive emotions, anticipatory emotions are proactive, arising from envisioning expected outcomes during decision-making [31]. Supporting this account, our study conducted during China’s first COVID-19 lockdown found that imagining personal infection (vs. reflecting on the pandemic in general) significantly increased future orientation in monetary intertemporal choice tasks and the intention to adopt preventive measures [32]. This finding illustrates the adaptive utility of mortality awareness focused on life’s finitude in guiding behavioral decision-making.

Based on the above analysis, the adaptive time management framework offers an alternative perspective on mortality awareness: not as a static source of anxiety and fear, but as a flexible time cue that individuals across different stages of life may use to recalibrate priorities and navigate present–future (survival–reproduction) trade-offs more effectively (see Figure 1). Through episodic end-of-life thinking, individuals can experience anticipatory emotions toward mortality, which in turn serve as adaptive cues for regulating emotions and supporting strategic decision-making in resource management by adjusting priorities between immediate survival and future reproduction.

In the following sections, we aim to provide a thorough review of more recent research developments to evaluate the adaptive time management framework that integrates mental time travel, episodic future thinking, and meditation, and focus on their synergistic effects on intertemporal choice in resource management, instead of a comprehensive literature review of each subfield. To enhance transparency, we systematically summarized the key findings of 114 reviewed articles and books (Table A1 in the Appendix A). We first examine how mortality awareness may adaptively reshape present–future trade-offs via temporal cues. Specifically, we consider how each decision premise modulates these effects, including perceived remaining time, death’s unpredictability, and life’s finitude. Next, we explore the potential role of mortality awareness in enhancing emotion regulation via episodic end-of-life thinking, particularly through the elicitation of anticipatory emotions. This section also introduces a novel behavioral intervention, “life-history intertemporal meditation”, grounded in the adaptive time management framework, and considers its potential for improving emotion regulation. Finally, we outline the framework’s research outlook and practical applications.

2. Methods

2.1. Literature Search Strategy

This review employed a targeted literature search strategy to identify key scholarly works at the intersection of mortality awareness and adaptive time management. The focus was on sources that integrate concepts of mental time travel, episodic future thinking, and meditation in the context of mortality cues and their influence on variations in life-history strategies, intertemporal choice, and resource allocation. The goal was to synthesize recent developments and insights into how mortality awareness can shape time perception, decision-making, and emotion regulation, rather than to conduct an exhaustive systematic review of each related subfield.

Specifically, we included studies that explicitly examined how mortality awareness influences time-related cognition and decision-making. Such outcomes encompassed future planning, intertemporal choice (delay discounting), life-history strategy selection (fast–slow continuum), and emotion regulation. We primarily considered peer-reviewed empirical studies, review articles, and theoretical papers directly addressing this intersection. This selective approach allowed for the inclusion of seminal foundational works alongside contemporary empirical findings.

2.2. Search Strategy and Keywords

We conducted comprehensive searches across multiple databases, including PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus, and Google Scholar, to identify relevant literature. Our search strategy combined terms from four thematic domains with death-related keywords to pinpoint studies linking mortality awareness to time-oriented cognition and decision-making. Specifically, four main key categories were defined (with representative examples). Search terms from each category were used in various combinations with mortality-related terms (e.g., “mortality”, “death”, “death anxiety”, “death reflection”): (1) mental time travel (e.g., “episodic future thinking”, “anticipatory emotion”, “autonoetic consciousness”, “mental time travel”); (2) time perception and management (e.g., “time perception”, “delay discounting”, “temporal focus”, “time management”); (3) life-history theory (e.g., “fast–slow strategy”, “resource scarcity”, “unpredictability”, “harshness”); and (4) emotion regulation (e.g., “self-control”, “cognitive reappraisal”, “approach–avoidance emotion”, “mindfulness meditation”).

2.3. Search Date

All literature searches were completed in September 2025. The final set of 114 publications spans a broad range of publication years, from 1971 to 2025, reflecting the inclusion of both early influential works and the most up-to-date research available at the time of the review.

3. Mortality Awareness Regulates Present–Future Trade-Offs via Time Cues

3.1. Time Management vs. Terror Management

What has been affected by mortality awareness, time management, or terror management? According to terror management theory, mortality awareness primarily elicits negative emotions and defensive reactions aimed at self-preservation [16,17]. This defensive stance often manifests as death anxiety, which generates proximal and distal defenses [18,19]. However, the adaptive time management hypothesis argues that the finitude of life is a central evolutionary premise for the design of the human mind. The pursuit of human beings is tailored to their limited lifespan and adapted to the needs at different stages of life, including survival, growth, reproduction, and parenting [4,7,8,13,14]. Whereas terror management theory highlights the palliative function of defenses to alleviate existential anxiety, the adaptive time management hypothesis emphasizes the proactive role of mortality awareness as a temporal signal for adaptive regulation.

Humans are not merely defensive beings, but also effective time managers, capable of engaging in foresight, future planning, goal setting, and organizing their behaviors accordingly [2]. Mortality reminders sharpen perceptions of time scarcity, making temporal allocation itself a central regulatory task. Thus, when contemplating or confronting death, responses are not limited to passive defenses; instead, they often involve strategic time management, in which awareness of mortality helps recalibrate priorities. This adaptive form of death reflection enables individuals to move beyond impulsivity and anxiety triggered by death and instead prepare with greater caution, calmness, and deliberation. Emotionally, this strategic stance is characterized by an anticipatory affective profile that fosters existential vigilance, distinct from the existential anxiety emphasized by terror management theory. It shifts responses from reactive fear to calm preparedness and sustains a steady, goal-directed mindset rather than defensive reactivity.

Prior research has distinguished between death anxiety, which evokes terror and defensiveness, and death reflection, which represents a calmer, more deliberate awareness of mortality that helps individuals reorient priorities [33]. Evidence further suggests that death reflection, unlike standard mortality salience manipulations, can foster constructive outcomes, such as gratitude and an appreciation for meaningful experiences, by facilitating priority recalibration and sense-making [5,34]. These findings are consistent with the adaptive time management view that mortality awareness may serve adaptive functions for strategic time management.

3.2. Subjective Time Perception as an Adaptive Cue

The adaptive time management framework proposes that mortality awareness regulates how individuals perceive time by compressing or expanding their subjective time perception and shifting temporal focus across the lifespan. According to pacemaker-accumulator models, an internal neural clock emits pulses counted to judge elapsed intervals [35,36,37]. Dynamic calibration of this clock can promote deliberate and measured responses, thereby dampening impulsive tendencies.

Converging evidence suggests that heightened arousal accelerates the internal clock, making intervals feel longer and increasing the speed of intervals. Together, these effects may foster a sense of urgency in intertemporal decisions [38,39]. Practically, each “tick” of the internal clock comes faster, so a given objective interval feels longer [39]. If the interval until life’s end seems to collapse, distant rewards lose subjective value, thereby increasing delay discounting [36]. Delay discounting measures, widely used in economics and psychology as indices of intertemporal choice and strategic resource management, capture present–future trade-offs in choices between smaller-sooner (SS) and larger-later (LL) rewards [40]. For example, imagine choosing between $100 in six months or $50 today. Under resource (time) scarcity, the perceived horizon shortens, increasing preference for the immediate $50 option. Conversely, when resources are plentiful and arousal subsides, individuals are more likely to wait for delayed payoffs.

Environmental factors (i.e., resource scarcity, unpredictability, and harshness) and mortality awareness may interact and affect delay discounting differently, depending on how mortality cues are induced and the decision maker’s age (life-history stage). When mortality awareness arises from the temporal variations of life’s endpoint, this salience of death’s unpredictability can make death feel imminent and, thus, promote SS preference. Time perception may also slow or feel “stopped” as individuals are trapped in the anticipated terminal moment of life. Consistent with this account, our ongoing experimental work shows that young adults engaging in endpoint-focused episodic thinking (vs. present-focused episodic thinking) report slower subjective time, suggesting that endpoint salience narrows temporal focus and fosters present-oriented strategies.

By contrast, when mortality awareness arises from mental time travel (i.e., envisioning the passage of time) between the present and life’s end, it emphasizes life’s finitude and the travel between now and the future endpoint, and, thus, may promote LL strategies. In such a condition, subjective time may accelerate, as individuals experience time flowing toward an inevitable end. Experimental findings show that people overestimate time passage when a future aversive outcome is expected at a specific temporal point (e.g., waiting time for a punishment seems longer) [39,41]. Our recent empirical study demonstrates that repeated mental time travel between the present and life’s endpoint can accelerate subjective time perception among young adults [15]. Moreover, episodic future thinking reduces delay discounting, particularly in young adults who perceive a longer time horizon in the future [42,43]. Simulating a life journey toward an uncertain terminus engages prospection and retrospection, treating time as a moving flow rather than a fixed point [2,36]. Under this “passage focus”, each moment seems to rush, spurring individuals to act quickly to secure future outcomes. This type of mortality awareness highlights life goals for young adults with more time remaining. It fosters a greater future orientation by reducing impulsivity and urgency, while reinforcing long-term planning.

3.3. Present–Future Trade-Offs as Strategic Decisions

According to the adaptive time management framework, mortality cues may prompt individuals to strategically adjust their temporal priorities, as measured by delay discounting. Importantly, delay discounting reflects trade-offs between present and future orientations, not impulsivity per se. Although steep discounting is often equated with impulsiveness [44,45], recent research has found low convergent validity between delay discounting and various behavioral impulsivity measures, with correlations as low as zero, suggesting that delay discounting and impulsivity represent distinct psychological constructs [46]. Similarly, shallow discounting does not necessarily guarantee high self-control, because self-control entails resolving conflicts between the feeling and reason beyond simple temporal preference [47].

Preferring SS rewards can, in specific contexts, be an adaptive strategy for achieving long-term goals rather than a lapse of self-control. An SS choice may be allocated toward immediate leisure or used to meet the needs of survival (e.g., purchasing insurance), growth (e.g., investing in education), and reproduction (e.g., parental care). Consequently, when confronted with mortality cues, individuals may adaptively shift toward present-focused choices or future-focused planning, depending on contextual demands and strategic needs—without this necessarily implying irrationality or poor regulation.

Mortality cues have emerged as potent influences on how people weigh immediate rewards against future benefits. A broad range of studies, spanning controlled experiments and correlational field studies, converge to show that present–future preference shifts occur in ways broadly consistent with predictions of life-history theory when death looms (literally or psychologically). However, the direction of this shift is not uniform. Below, we synthesize these findings within the framework of adaptive time management.

3.3.1. Less Perceived Remaining Time Favors Fast Strategies

The adaptive time management framework suggests that a constricted perception of remaining time can be a powerful trigger for fast strategies, prioritizing immediate gains over delayed payoffs. When future horizons appear narrow (due to actual resource scarcity or imagined constraints), people’s subjective time tends to feel accelerated, directing attention toward urgent needs rather than long-term investments.

Ecological and demographic analyses generally align with this prediction at the population level. In Chicago neighborhoods with the lowest life expectancy and highest homicide rates, the median age at first birth was 22.6 years, compared with 27.3 years in safer areas, suggesting that shortened horizons may accelerate reproductive timing [48]. Across 170 countries, female life expectancy explained 74% of the variance in average age at first birth: shorter national lifespans predicted younger motherhood [49]. Similar trends are evident within nations: English neighborhoods marked by low longevity and high deprivation show faster life-history profiles, including larger families and earlier reproduction [50]. Likewise, rural Caribbean populations exposed to frequent community deaths and reduced life expectancy adopted accelerated reproductive schedules [51]. Although these correlations cannot rule out alternative explanations, such as socioeconomic prosperity, education, or maternal health risks, they are consistent with the idea that when remaining time feels scarce, populations shift toward more present-focused choices.

Experimental and neurocognitive studies further show that subjective constriction of time can tilt intertemporal preferences. Participants were asked to imagine living on a severely limited monthly budget, thereby evoking a narrow time horizon, exhibiting steeper delay discounting, and trading off LL rewards for SS ones [25]. Other studies indicate that anticipatory time contraction systematically increases discounting [38]. More recent work, which directly manipulates internal timekeeping, has revealed corresponding shifts in discounting, accompanied by neural changes in prefrontal and insular circuits that support time perception [52].

At the individual level, developmental and contextual factors shape sensitivity to time scarcity. Adolescents typically show steeper delay discounting than young and middle-aged adults, forming the first arm of a U-shaped discounting curve [24]. Meta-analytic modeling across 105 studies suggests that discounting is lowest around midlife (around age 50) and rises again in later adulthood [24]. A three-way mortality-fertility-parenting trade-off model helps explain this pattern: as mortality risk increases and fertility declines with age, individuals must balance current reproduction with the need for parenting and resource conservation [24]. These competing needs and motivations jointly shape age-related shifts in intertemporal choice. Middle-aged adults, who face multiple future obligations (e.g., career, family), often adopt slow strategies in response to mortality cues, thereby preserving accumulated resources.

According to socioemotional selectivity theory, older adults, perceiving their lifetime as shrinking, are expected to shift preferences toward the here-and-now [21,22,23]. Yet despite age-related decline, they often report higher well-being and life satisfaction than their younger counterparts [53]. While this theory highlights perceived time horizons as a driver of well-being, recent longitudinal meta-analysis challenges this account [54]. Life satisfaction rises modestly until about age seventy and then declines. Positive affect decreases across adulthood, while negative affect declines until age sixty and then increases. In late adulthood, well-being tends to worsen rather than improve [54]. These results suggest that well-being trajectories primarily reflect the accumulation of losses in health and social relationships [55,56], rather than simply a shrinking time horizon. However, these findings do not contradict the U-shaped function of delay discounting; an SS preference in old age may be strategic for improving more urgent physical and social needs, and is often sensitive to specific environmental inputs [57]. From the adaptive time management perspective, calibrating present–future trade-offs is a lifelong task.

Beyond age, early-life environments also influence the calibration of delay discounting. Adults raised in low-socioeconomic-status (SES) contexts exhibit a more substantial present-orientation in response to mortality reminders, whereas those from high-SES backgrounds often shift toward future rewards [58,59]. Extending this line of research, one of our ongoing studies reveals a nuanced SES–fertility interaction: parents with two or more children had a lower delay discounting rate than those with only one child. This relationship was moderated by their childhood SES, which negatively correlated with delay discounting. Real-world crises provide further evidence. During the COVID-19 pandemic, Turkish undergraduates exposed to vivid mortality statistics required larger delayed rewards to forgo immediate payouts [60]. Chinese participants imagining personal infection showed similarly elevated discounting [57]. In a U.S. survey, low-income adults facing severe financial hardship discounted money and grocery rewards more steeply than those without hardship, with food insecurity further amplifying discounting of grocery rewards [61]. These findings underscore that responses to perceived time scarcity are developmentally calibrated and context-dependent.

In sum, evidence across ecological, experimental, and individual levels converges on a core adaptive time management framework prediction. When perceived remaining time is limited, individuals tend to shift toward fast, present-focused strategies as an adaptive response to scarcity.

3.3.2. Greater Awareness of Death’s Unpredictability Favors Fast Strategies

The adaptive time management framework proposes that when death’s unpredictability becomes salient, attention narrows to immediate survival, and individuals may adopt fast strategies to secure fitness. Unlike terror management theory’s emphasis on suppressing death anxiety, this “uncertainty focus” can serve an adaptive purpose: when life feels fragile and uncertain, seizing present opportunities enhances personal safety and redirects effort toward protecting kin.

Evidence from animal foraging and human survival contexts is consistent with this prediction. In high-risk habitats, birds and mammals shift toward low-cost, high-yield food sources rather than exploring uncertain options [27]. Similarly, chimpanzees prefer guaranteed rewards over risky payoffs in the face of threat [26]. Similarly, human studies show that when resources are scarce and mortality cues become unpredictable (i.e., high variations), people prioritize basic needs before aspirational goals [29]. These findings suggest that when unpredictability is salient, organisms shift toward strategies that maximize immediate survival.

Awareness of death’s unpredictability may promote protective risk-taking to preserve inclusive fitness. This form of risk-taking involves self-sacrificing actions to enhance kin survival. From a life-history perspective [7], such behavior reflects a fast strategy at the individual level, where one trades longevity for immediate gains in inclusive fitness, while remaining adaptive at the genetic level. A vivid example comes from salmon, which swim upstream against lethal odds to spawn, ensuring the next generation’s survival rather than prolonging their own [14]. Humans display similar behaviors: parents, especially mothers, are often willing to endure personal danger to safeguard offspring [62]. Such protective risk-taking represents a fast strategy to increase inclusive fitness at a personal cost [63,64].

Human decision-making experiments and real-world data support this prediction. Exposure to everyday mortality cues that signal volatility reliably shifts preferences toward the present. Graphic news of local violence (an acute, stochastic hazard) increases preference for immediate monetary rewards [65]. In Caribbean communities, recent family or community deaths (salient cues that survival prospects are volatile rather than stable) accelerate reproductive schedules [51]. In the UK, regions with high local mortality, such as frequent traffic fatalities, where fatal risk is experienced as unpredictable in daily settings, show reduced engagement in preventive health behaviors [66]. Together, these findings indicate that when death is appraised as uncertain in timing and control, people prioritize near-term, sure gains over delayed, more fragile benefits—a fast, present-oriented strategy under unpredictability.

Developmental and psychological factors modulate the strength of this fast-strategy response. Adults exposed to high childhood adversity show greater present bias under mortality cues [58,59], consistent with the idea that unpredictable and threatening early environments calibrate individuals toward immediacy. By contrast, brief self-affirmation can buffer urgency and reduce discounting, highlighting the role of psychological resources in offsetting fast shifts. Older adults, often integrating death into their self-concept, display less reactivity and greater emotion regulation [21,22,23], suggesting that accumulated experience and acceptance of life’s finitude can temper the pull of unpredictability cues. Although longitudinal data are limited, our recent meta-analysis reveals a U-shaped trajectory of discounting, with an inflection point around age fifty, consistent with a three-way trade-off among mortality, fertility, and parental needs [24]. Thus, while younger and adversity-exposed individuals lean more heavily toward present-focused strategies under unpredictability, emotional acceptance and lifespan recalibration later in life can partially mitigate urgency before shrinking horizons again re-orient decisions toward the present.

In sum, awareness of death’s unpredictability across species and contexts generally drives fast, present-oriented strategies. By focusing on life’s uncertainty and proximity to death, mortality cues elicit a sense of urgency and promote immediate gains—a pattern shaped by developmental stage, resilience, and individual history.

3.3.3. Higher Awareness of Life’s Finitude Favors Slow Strategies, If Perceived as Controllable

When mortality awareness is induced by information about the inevitability of death, individuals (especially the young) tend to adopt more future-oriented strategies. Crucially, perceived agency matters. Impulsivity measures (e.g., pleasure-based diet choice) increased when mortality risk was framed as uncontrollable, whereas controllable mortality risk produced no change [66]. This distinction suggests that a sense of control can buffer the pull of fast strategies even under time-scarcity conditions. Because life’s finitude can be appraised as manageable through preparation, individuals high in self-efficacy are especially likely to channel mortality awareness into proactive planning. Self-efficacy may thus become a critical factor in regulating domain-specific confidence and reducing impulsivity [67,68].

Psychological evidence reinforces this pattern. Although death is inevitable, age-based mortality distributions are probabilistically predictable: young adults typically have more remaining time before the end of life than older adults. Therefore, when the cues of finitude are perceived as controllable, individuals may shift into slow, future-oriented strategies, emphasizing planning and diversification to achieve life goals before it is too late. This finitude-management orientation encourages mentally simulating multiple possible outcomes and allocating resources to guard against potential threats, much like evolutionary bet-hedging [7,69]. Episodic future thinking engages prefrontal networks linked to planning and prospection [2], eliciting anticipatory emotions (e.g., peace, sadness) that can increase the attractiveness of delayed rewards [15,32]. Our experiments further demonstrate this dynamic. Mortality reminders reduced delay discounting and accelerated subjective time perception among young adults [14]. For these young participants in their early 20s, self-generated mortality awareness is more likely to highlight the inevitability of death than its unpredictability. The inevitability of death (life’s finitude) fosters slow strategies and LL choices, if it engages in mental time travel. Follow-up work showed that retrospective mental time travel (i.e., replaying past events) under mortality/old-age priming produced greater reductions in discounting than prospective primes (i.e., imagining future scenarios)—an effect absent when the prime referenced old age (e.g., “turning 70”) rather than death [13].

Behavioral studies and real-world crises also support this account. Liu and Aaker [70] found that young adults who experienced a relative’s cancer-related death became more willing to save for the long term, treating resources as a buffer against finitude. During China’s first COVID-19 lockdown, imagining personal infection increased future orientation, lowered discounting, and boosted preventive intentions compared to control reflections [32]. Although modest, this effect aligns with the prediction that anticipatory emotions triggered by mortality reminders can lead to slow strategies. Likewise, when mortality risk was framed as stochastic but survivable, people scheduled more preventive health appointments while still meeting immediate needs, illustrating a calibrated form of bet-hedging that integrates fast and slow strategies [71]. Extending to social domains, subtle death-word puzzles increased low-cost altruistic giving in dictator games, indicating investment in collective welfare against certain but unpredictable endpoints [72].

Anthropological observations provide parallel evidence. In semi-arid pastoralist communities of northern Kenya, herders diversify livestock species (e.g., camels, goats, cattle, donkeys) and invest in rainwater harvesting structures, such as Zai pits and water pans, to buffer against intermittent droughts [73,74]. Such practices exemplify long-term, future-oriented bet-hedging strategies, reflecting how awareness of life’s finitude motivates resource diversification and planning to enhance future survival rates.

Developmental evidence also illustrates this orientation. Having experienced multiple life contingencies, older adults are more likely to readily translate finitude cues into long-term planning. Surveys conducted during economic downturns reveal that retirees who perceive greater limitations in the future allocate larger shares of their portfolios to diversified assets and estate-planning vehicles, such as Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities, real assets, and wills. In contrast, those perceiving less constraint maintain higher allocations in short-term, riskier holdings [75,76]. These findings also align with the proposition of adaptive time management, which suggests that awareness of life’s finitude motivates resource bet-hedging and long-term planning, particularly to safeguard offspring and kin in the face of life’s inevitable limitations.

In sum, converging evidence suggests that individuals often employ slow, future-oriented strategies to hedge against possible outcomes when life’s finitude is salient. People allocate resources toward planning, diversification, and long-term investment by widening temporal focus to encompass an inevitable endpoint. This adaptive orientation emerges across natural processes, laboratory and field studies, cultural practices, and life stages, underscoring the central role of finitude focus in human resource management under uncertainty.

4. Mortality Awareness Enhances Emotion Regulation via Episodic Future Thinking

4.1. Anticipatory Emotions as Informative Signals for Risk Management

The adaptive time management framework proposes that mortality cues shape temporal priorities and enhance emotion regulation via episodic future thinking and lifespan mental time travel. In ancestral settings, where trial and error often meant life or death, mentally simulating future risks provided a safe way of learning and decision-making [77,78]. By vividly imagining possible risks and consequences, individuals could anticipate dangers without physical exposure and make more informed, less costly choices [31,32].

Imagining future risky events generates anticipatory emotions that distill complex risk assessments into salient affective cues [79]. Rather than merely provoking generalized anxiety, these emotions guide cognitive evaluations of probability and severity through embodied sensations [31], directing attention to hazards of greatest relevance. Reviews of empirical studies consistently indicate that anticipatory emotions have a stronger effect on risk perception and behavioral intentions than unrelated emotional states [80,81].

Crucially, these forward-looking emotions differ from the dysfunctional fear and anxiety emphasized by terror management theory [16,17]. Under the adaptive time management framework, mortality awareness directs episodic future thinking toward adaptive, purpose-driven affects (i.e., what Heidegger termed “being-toward-death”), such as excitement that heightens attention to decision goals or fear that signals the risk of falling below a critical threshold. These anticipatory emotions can bolster self-control and motivate preventive actions by clarifying values and priorities, rather than triggering avoidance or denial [15].

4.2. Episodic End-of-Life Thinking Enhances Emotion Regulation

According to the adaptive time management framework, mortality awareness can evoke powerful anticipatory emotions about one’s future (e.g., a sense of urgency), thereby influencing how individuals regulate their ongoing emotions. Recent research suggests confronting mortality may promote internal growth and strengthen emotion regulation capacities [82,83]. When people become aware of their limited time, they often reevaluate their priorities and engage in self-regulation, enabling them to live more meaningfully and with greater psychological balance.

This section examines how mortality cues and the anticipatory emotions they elicit may enhance self-control, cognitive reappraisal, and other adaptive regulatory capacities, and how these processes are moderated by age and personality traits.

4.2.1. Enhanced Self-Control under Mortality Awareness

Mortality awareness may motivate individuals to exercise self-control [14,15]. Anticipatory emotions, such as anticipating future regret, play a crucial role in adaptive decisions [84]. When people imagine feeling regret at life’s end for not pursuing important goals or for succumbing to short-term temptations, they are more likely to exhibit greater impulse control in the present.

For example, reminders of mortality can lead individuals to prioritize meaningful pursuits over fleeting gratifications, thereby down-regulating impulsive desires. Empirical studies show that when participants are guided to reflect deeply on their own mortality, they subsequently display less greed and a greater focus on intrinsic values [85]. In other words, a profound mortality awareness intervention encouraged people to exercise self-control by shifting away from self-indulgence and toward value-driven goals [85,86]. This effect extends to health behaviors and moral choices. Some research suggests that mortality reminders, when combined with a sense of efficacy, prompt healthier lifestyle choices (e.g., quitting smoking or reducing risky behaviors) as individuals anticipate future consequences and take steps to avoid regret [66,71]. Such findings resonate with the notion that life is too short for trivialities: awareness of life’s fragility (unpredictability and finitude) may encourage individuals to control impulsive urges that conflict with their enduring values. Recent evidence on narrative episodic future thinking provides a parallel demonstration: vividly imagining limited future horizons reduces delay discounting and enhances goal salience in general population samples [87], suggesting that future-oriented simulations, like death reflections, can strengthen self-control.

Personality and situational factors also shape the effects of mortality awareness. Mortality cues are more likely to elicit productive self-control efforts among individuals with greater baseline self-discipline or future orientation, whereas those with lower self-control may feel overwhelmed by fear and fail to change behavior. Notably, dispositional self-control has been found to buffer against negative, selfish responses to mortality cues [88,89], suggesting that trait-level self-regulation can help harness death-related emotions constructively.

In sum, when anticipatory emotions aroused by mortality are coupled with reflection on personal goals, they can enhance self-control by motivating individuals to “make the most” of their remaining time and avoid actions they may later regret. This pattern reflects the adaptive time management framework’s emphasis on the finitude of life. By confronting the inevitability of death, individuals are motivated to invest in future-oriented, value-consistent strategies rather than short-sighted ones.

4.2.2. Mortality Awareness Promotes Cognitive Reappraisal and Positive Refocusing

Mortality awareness may enhance emotion regulation by promoting increased cognitive reappraisal and a greater focus on positive emotional experiences. Cognitive reappraisal (i.e., reinterpreting a situation to alter its emotional impact) is a key adaptive strategy in regulating feelings [90]. Awareness of life’s fragility can put daily hassles and conflicts into perspective, making it easier for individuals to reappraise negative events as relatively minor or as opportunities for growth.

Research consistently shows that people shift toward more frequent use of positive reappraisal and less use of maladaptive strategies, such as rumination or aggression, as they age and their subjective sense of remaining time shortens [91]. For instance, studies report a developmental trend in which older adults rely more on cognitive reappraisal and less on expressive suppression compared to younger adults [91]. This shift is thought to occur because older individuals, aware of their limited time, become motivated to maximize positive affect and minimize negative affect in their daily lives [21,22,23]. By reframing adversities in life more positively and meaningfully, individuals can regulate their emotions more effectively. Although these shifts are most consistently observed in later life, experimental work indicates that similar reappraisal processes can be temporarily induced in younger adults through mortality reminders [15].

Mortality awareness can foster a similar mindset in younger individuals: reminders of death often prompt people to reevaluate what truly matters to them, facilitating a reappraisal of petty stressors (e.g., “don’t sweat the small stuff”) and a greater appreciation for each day. Experimental work shows that death reflection and standard mortality salience manipulations increase “gratitude for life” among undergraduates compared with controls, a shift consistent with adopting a positive reappraisal stance [5]. In media contexts, mortality salience has also heightened appreciation for meaningful films, especially among individuals high in the search for meaning [34]. From the adaptive time management perspective, these findings suggest that when death reminders are actively transformed into opportunities for sense-making, they enable individuals to “zoom out”, reconsider priorities, and regulate emotions in more constructive, future-oriented ways. Thus, anticipatory emotions triggered by mortality may encourage individuals to adopt a broader, more positive perspective, thereby potentially enhancing their emotion regulation [15].

Those adept at reappraisal can transform death-related fears into motivation to live more fully, often reporting feelings of gratitude or clarity about priorities, thereby enhancing emotional well-being. Indeed, engaging in cognitive reappraisal immediately after a mortality reminder can reduce individuals’ negative affect and dampen defensive reactions [92,93]. Unlike defensive avoidance emphasized in terror management theory, this pattern highlights a functional adaptation that channels death awareness into constructive regulation.

In sum, mortality awareness may catalyze cognitive reappraisal, enabling individuals to regulate distress by focusing on the meaning, silver linings, and positive aspects of life.

4.2.3. Mortality Awareness Promotes Approach-Oriented Emotions and Sense-Making

While death awareness can elicit fear (an avoidance-oriented emotion), it may also spark approach-oriented emotions, such as hope, compassion, or a drive for meaning, which play a crucial role in emotion regulation. Recent theoretical frameworks distinguish between death anxiety (i.e., a panic-like, avoidance response to mortality) and death reflection (i.e., a calm, deliberate contemplation of mortality and its implications) [33].

Death anxiety corresponds to terror and defensiveness, which often undermine emotional stability. By contrast, death reflection tends to generate approach-oriented motivations: people consider what gives their life meaning and how they want to spend their remaining time, often leading to self-transcendent emotions and behaviors (e.g., love, altruism, or achieving personal aspirations) rather than withdrawal. For example, Grant and Wade-Benzoni [33] proposed that “cool” death awareness (reflection) prompts prosocial actions and meaningful, approach goals, whereas “hot” death awareness (anxiety) triggers self-protective avoidance.

In addition to prosocial motivation, death reflection often involves sense-making processes that transform anxiety into constructive energy. By finding meaning in life via mortality awareness (e.g., seeing death as a natural transition or an impetus to live authentically), people can reframe death as a source of motivation and resilience. Psychological research refers to this process as “posttraumatic growth” in the context of life-threatening experiences [94]: individuals often report that confronting death, whether through personal crises or global events, fosters emotional growth, deepening gratitude, spirituality, or connection. For instance, Lykins and colleagues [86] found that mortality reminders can shift personal goals and values in a growth-oriented direction among those predisposed to reflection, bridging terror management processes with positive transformation. Even a brief “memento mori” intervention (i.e., warnings of death) increased generosity and reduced materialism when they encouraged reflective processing [85].

Empirical research during the COVID-19 pandemic provides further support for this dual-pathway model. Studies identified distinct profiles of employees facing heightened mortality cues: “calm reflectors” (high death reflection, low anxiety) and “anxious reflectors” (high on both) were more common than disengaged individuals [83]. Notably, calm and anxious reflectors were more likely to exhibit approach behaviors like prosocial actions than disengaged individuals [83]. Similarly, Shao and colleagues [95] found that exposure to COVID-related death news simultaneously raised death anxiety and generativity-based death reflection, with contrasting outcomes: anxiety predicted greater work withdrawal (avoidance), whereas reflection predicted greater helping (approach) behavior toward coworkers.

These findings suggest that when mortality awareness triggers approach-oriented emotions (e.g., a sense of responsibility to others or a sense of urgency to contribute), individuals can channel their emotional energy into constructive behaviors that improve their well-being (e.g., through building social support, finding purpose, etc.). Approach-related emotions, such as inspiration or excitement about “making a difference”, may mitigate the helplessness of fear and facilitate active coping.

In sum, anticipatory emotions that are approach-oriented and stem from mortality awareness may bolster individuals’ capacity to regulate emotions. Such emotions motivate proactive behaviors and foster a mindset that embraces life with purpose rather than retreating into fear.

4.2.4. Moderating Roles of Age and Personality on the Effects of Mortality Awareness

The impact of mortality cues on emotion regulation via anticipatory emotions is not uniform for everyone; age and personality traits critically moderate these effects. Age differences in responses to mortality are well documented. Generally, older adults (who encounter mortality more saliently due to life experience) demonstrate better emotion regulation and fewer defensive reactions to death awareness than younger adults. They often report lower death anxiety and greater acceptance of mortality [21,22,23]. For example, Maxfield and colleagues [96] found that while younger adults reacted to mortality cues with defensive responses, older adults were relatively undisturbed. Instead, they avoided conflict and used positive reappraisal to maintain emotional stability.

Adaptations to frequent encounters with death (e.g., loss of loved ones, health threats) may allow older adults to experience mortality cues with less panic and more reflection, turning mortality into a tolerable, even motivating, aspect of life [97,98]. Nevertheless, when guided toward reflective mortality awareness (e.g., during the COVID-19 pandemic), younger adults can also show adaptive responses, such as increased future orientation and preventive intentions [32]. Importantly, older adults react to mortality reminders or cues differently. Those individuals in good mental health and with psychological resilience are likely to exhibit positive coping [99], whereas older individuals with unresolved death anxiety may continue to struggle [100]. The key point is that age brings opportunities for sense-making from reflections on mortality [24], thereby enhancing regulation via anticipatory adaptive emotions.

Personality traits also influence whether mortality awareness serves as a catalyst for emotional growth or a trigger for distress. Resilience is one crucial trait: highly resilient individuals are better able to cope with stress and adapt positively, making mortality cues more likely to evoke constructive anticipatory emotions rather than debilitating fear. A recent latent profile analysis of nurses in China illustrates this role: high resilience and death-education were associated with low anxiety and high mortality reflection, consistent with constructive responses to mortality [82]. Beyond occupational samples, experimental work indicates that the impact of death reminders can depend on resilience-related resources in other domains. For instance, mortality salience increased experimentally induced pain sensation, which can be buffered by mental resilience [101]. Self-esteem also provides a complementary buffer. Meanwhile, low self-esteem predicts larger drops in well-being, meaning in life, and exploration following death-thought activation across both U.S. and Chinese samples [102,103]. These findings suggest that resilience and self-esteem not only suppress anxiety but also facilitate the constructive processing of mortality awareness, aligning with the adaptive time management emphasis on strategic time management.

Mindfulness represents another moderator. Individuals high in dispositional mindfulness can encounter mortality reminders without being overwhelmed, often relying on acceptance-based strategies. Supporting evidence comes from near-death experience survivors: Bianco and colleagues [104] compared people who had a life-threatening near-death experience with individuals who had not and found that near-death experience survivors reported significantly lower death anxiety, higher mindfulness, and greater self-esteem. Having faced death, these individuals tended to view mortality more as a natural transition, a mindset shift associated with enduring improvements in emotion regulation. For example, high mindfulness correlates with more effective stress management and negative affect [105].

In sum, factors such as resilience, mindfulness, and self-esteem moderate the impact of mortality awareness on emotion regulation. Interventions that strengthen these traits have shown promise in enabling individuals to confront mortality and emerge psychologically stronger rather than traumatized. Mindfulness meditation, defined as nonjudgmental attention to the present moment, emphasizes body sensations, affective responses, and calm acceptance [106]. Empirical studies show that such practices can attenuate fear of death and reduce mortality-related anxiety, consistent with buffering mechanisms highlighted in terror management theory. For instance, mindfulness training diminishes defensive reactions to mortality salience, thereby alleviating death anxiety in experimental and clinical contexts [107,108]. Mindfulness provides present-focused mental practice. Meditation can be combined with mental time travel by extending mindfulness practice into a life-history framework. In the next section, we introduce “intertemporal meditation” and illustrate its potential effects on emotion regulation and adaptive decision-making.

4.3. Life-History Intertemporal Meditation within the Adaptive Time Management Framework

Life-history intertemporal meditation is a guided practice that integrates elements of traditional mindfulness with structured lifespan mental time travel and episodic future thinking [15]. During the practice, participants mentally travel between the present and the end of life. Following instructions, they engage in episodic future thinking while imagining scenarios from the current moment forward to life’s end and then returning, in repeated “out-and-back” cycles.

By explicitly linking the present self to a future self at life’s terminus, intertemporal meditation leverages three uniquely human capacities: mental time travel, episodic future thinking, and anticipatory emotions [13,14,31]. According to the adaptive time management framework, this practice is hypothesized to exert threefold effects on subjective time perception, anticipatory emotion, and intertemporal choice preferences.

In an exploratory experiment with Chinese young adults (mean age of 21.72), we compared intertemporal meditation against a matched mindfulness control [15]. The results showed that intertemporal meditation significantly accelerated subjective time: participants rated a 10-year span as shorter following intertemporal meditation, whereas mindfulness meditation alone did not alter time perception.

The two meditation types also yielded distinct emotional profiles. After intertemporal meditation, “peace” and “thrill” received the highest and lowest ratings, respectively, and “relaxation” and “fear” were rated the highest and lowest, respectively, after mindfulness meditation. Consistent with the adaptive time management hypothesis, anxiety did not increase, indicating that imagining the end of life generated adaptive, reflective emotions (e.g., peace) rather than paralyzing fear. Moreover, across participants, high acceleration of subjective time was associated with lower sadness, and this negative association was significantly stronger following intertemporal meditation. Together, these results imply that mindfulness and intertemporal meditations can regulate emotions without amplifying fear or anxiety. Intertemporal meditation appears to have a more substantial regulatory effect, reducing sadness by reshaping subjective time through episodic future thinking [15].

Neuroimaging evidence from functional near-infrared spectroscopy further elucidates the neural substrates of these effects. While both meditation forms engaged prefrontal and temporal networks, intertemporal meditation produced greater left-lateralized activation in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC), anterior prefrontal cortex, and orbitofrontal cortex across sessions. These regions are implicated in cognitive control, reappraisal, and valuation processes critical for emotion regulation and delaying gratification [109,110,111]. In contrast, mindfulness meditation showed relatively stronger right-hemisphere DLPFC activation, associated with withdrawal-oriented processing [112].

These preliminary findings support the adaptive time management hypothesis that intertemporal meditation fosters adaptive compression of perceived time and balanced anticipatory emotions, marked by calmness and reflective sadness, while avoiding overwhelming fear and reducing impulsive responses. The accompanying prefrontal activation pattern suggests enhanced cognitive control and regulation capacities, indicating that intertemporal meditation may uniquely strengthen self-regulatory functions compared to mindfulness alone. As a proof of concept, intertemporal meditation may serve as a practical, neuroscience-informed tool for improving emotion regulation and strategic decision-making [15].

5. Discussion

The adaptive time management framework integrates mortality awareness, mental time travel, and episodic future thinking, with their synergistic effects of shaping present–future trade-offs through time perception and anticipatory emotions. By highlighting the unpredictability of death or the finitude of life, individuals adaptively adjust their life-history strategies (varied between the fast–slow continuum), according to decision premises reflected in the mortality reminders and cues (i.e., resource scarcity, unpredictability, and harshness). The adaptive time management model emphasizes how episodic end-of-life thinking triggers anticipatory emotions that serve as informative signals for managing time and resource allocation risks.

Figure 2 provides a concise visual summary of the main findings reviewed under the adaptive time management framework. We developed a novel practice called life-history intertemporal meditation based on this framework. By alternating between present- and endpoint-focused scenarios, intertemporal meditation flexibly shifts temporal focus, heightening present action when time feels short and enhancing future planning when time feels ample. Future research should systematically examine the short- and long-term effects of this practice on impulsivity, risk-taking, and well-being, and test variations in directional emphasis guided by more detailed neuroimaging evidence to target the neural circuits underlying intertemporal meditation. Additional work should also explore how personality traits and individual differences, such as resilience, dispositional mindfulness, and self-esteem, moderate the adaptive benefits of this intervention.

Figure 2. A conceptual summary of the main findings reviewed under the adaptive time management framework. Note: The dashed arrows distinguish the extrinsic behavioral effects of intertemporal meditation from the intrinsic functional connections as indicated by the solid arrows.

Beyond individual training, the adaptive time management framework presents a new perspective on death education in contexts where discussing mortality remains taboo [113]. Traditional curricula often emphasize academic or vocational skills, leaving students underprepared for life’s inevitable end [113]. Experiential learning modules that foster a balanced time perspective—for example, by embedding endpoint-focused exercises, reflective writing on values, and guided intertemporal meditation into programs—may be helpful. Such activities teach factual knowledge about mortality and how to harness awareness of limited time to make wiser choices and manage grief more effectively. This approach resonates with Confucian wisdom (i.e., “one must understand life before understanding death”) and aligns with socioemotional selectivity theory, which posits that a limited time horizon shifts priorities toward emotionally meaningful goals [21,22,23]. Integrating adaptive time management into death education could reduce the psychological shocks of bereavement, promote healthier end-of-life decisions, and foster a culture that values both meaningful living and dignified dying.

Finally, adaptive time management-based interventions differ fundamentally from surreptitious behavioral “nudges”. Whereas nudges subtly alter choice architecture behind the scenes [114], intertemporal meditation and episodic end-of-life thinking explicitly engage participants in active reflections on mortality and life’s trajectory. This educational approach encourages intuitive change in time perception, emotional experience, and choice preferences, shaping decisions to better align with both immediate and long-term goals across the lifespan.

6. Limitations for Current Review

This review provides a focused conceptual synthesis rather than a comprehensive investigation of all related literature. As such, the selection of studies was guided by thematic relevance to mortality awareness and adaptive time management, rather than through formalized inclusion criteria or meta-analytic procedures. While this approach enabled the integration of diverse insights and the development of a novel interdisciplinary framework, it may have overlooked some peripheral studies that could have offered additional context. Nevertheless, by highlighting the convergence of mortality awareness, mental time travel, and time-related behavioral regulation, the proposed adaptive time management framework offers a new lens through which to understand intertemporal decision-making and life-history strategy variation. Future work may benefit from expanding this framework through systematic reviews or empirical validation across diverse contexts and samples.

7. Conclusions

This review introduced the adaptive time management framework as an alternative to terror management theory, highlighting mortality awareness as a cue for recalibrating temporal priorities rather than merely a source of anxiety. By integrating evidence from three life-history factors (resource scarcity, unpredictability, and finitude), we argued that death reflection combined with episodic future thinking can elicit anticipatory emotions, strengthen self-control, and promote adaptive strategies across the lifespan. Building on this perspective, we proposed life-history intertemporal meditation as a practical application designed to foster foresight and emotional balance. The adaptive time management hypothesis reframes mortality awareness and intertemporal mediation to manage time and resources in the face of death’s unpredictability and life’s finitude.

Appendix A

Table A1. References and empirical evidence for evaluating the adaptive time management hypothesis vs. the terror management theory.

|

Article List |

Research Type |

Adaptive Time Management Account |

Terror Management Account |

Neutral Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

[1] Tulving (2002). Episodic memory: from mind to brain. Annual Review of Psychology. |

Review |

- |

- |

Introduces autonoetic consciousness and episodic memory as the basis for self-projection across time. |

|

[2] Suddendorf & Corballis (2007). The evolution of foresight: what is mental time travel, and is it unique to humans? Behavioral and Brain Sciences. |

Review |

- |

- |

Argues humans uniquely simulate future scenarios via mental time travel. |

|

[3] Garay et al. (2019). To save or not to save your family member’s life? Evolutionary stability of self-sacrificing life history strategy in monogamous sexual populations. BMC Evolutionary Biology. |

Empirical study |

Self-sacrifice can be evolutionarily stable when it enhances kinship-based inclusive fitness, illustrating that adaptive long-term investment is consistent with adaptive time management. |

- |

- |

|

[4] Navarrete & Fessler (2005). Normative bias and adaptive challenges: a relational approach to coalitional psychology and a critique of terror management theory. Evolutionary Psychology. |

Review |

Challenges terror management theory and emphasizes coalitional psychology over terror-based defenses. |

- |

- |

|

[5] Frias et al. (2011). Death and gratitude: death reflection enhances gratitude. The Journal of Positive Psychology. |

Empirical study |

Death reflection increases gratitude for life, F(2, 109) = 5.92, p = 0.004, partial η2 = 0.10, supporting the adaptive time management view that mortality cues can elicit adaptive anticipatory emotions. |

- |

- |

|

[6] Wade-Benzoni et al. (2012). It’s only a matter of time: death, legacies, and intergenerational decisions. Psychological Science. |

Empirical study |

Mortality cues increase concern for legacy and future generations, t(17.35) = 3.01, p = 0.008, supporting adaptive time management by showing that death reflection can promote future-oriented, generative goals. |

- |

- |

|

[7] Ellis et al. (2009). Fundamental dimensions of environmental risk: the impact of harsh versus unpredictable environments on the evolution and development of life history strategies. Human Nature. |

Review |

Defines ecological risk dimensions that guide fast–slow life-history strategies, which form the theoretical basis for terror management theory. |

- |

- |

|

[8] Figueredo et al. (2006). Consilience and life history theory: from genes to brain to reproductive strategy. Developmental Review. |

Review |

Illustrates the distinction between fast and slow strategies from the developmental perspective. |

- |

- |

|

[9] Belsky et al. (1991). Childhood experience, interpersonal development, and reproductive strategy: an evolutionary theory of socialization. Child Development. |

Review |

Same as above. |

- |

- |

|

[10] Li et al. (2025). Mortality, self-interest, and fairness: the differential impact of death-related news on advantageous inequity aversion. Personality and Individual Differences. |

Empirical study |

- |

Death-related news supports terror management theory by showing that mortality cues (accidental vs. illness) shift fairness preferences toward defensive self-interest (Study 1: F(3, 142) = 2.800, p = 0.042, partial η2 = 0.056; Study 2: F(1, 60) = 10.46, p = 0.002, partial η2 = 0.148). |

- |

|

[11] Gasiorowska et al. (2018). Money as an existential anxiety buffer: exposure to money prevents mortality reminders from leading to increased death thoughts. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. |

Empirical study |

- |

Monetary primes buffered mortality salience (MS), reducing death-thought accessibility (e.g., Exp. 2: MS × money, F(1, 72) = 21.23, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.23) |

- |

|

[12] Zaleskiewicz et al. (2015). The scrooge effect revisited: mortality salience increases the satisfaction derived from prosocial behavior. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. |

Empirical study |

- |

Mortality reminders increase satisfaction with prosocial acts (e.g., F(1, 60) = 4.90, p = 0.010, partial η2 = 0.11; F(1, 39) = 5.50, p = 0.020, partial η2 = 0.12), indicating that prosocial acts buffer death anxiety. |

- |

|

[13] Wang & Wang (2024). How mortality awareness regulates intertemporal choice: a joint effect of endpoint reminder and retrospective episodic thinking. Consciousness and Cognition. |

Empirical study |

Endpoint (death) reminders, combined with retrospective thinking, reduced delay discounting more than prospective cues, F(1, 219) = 10.90, p = 0.001, partial η2 = 0.047, showing that mortality awareness enhances future orientation through backward mental time travel. |

- |

- |

|

[14] Wang et al. (2019). Adaptive time management: the effects of death awareness on time perception and intertemporal choice. Acta Psychologica Sinica. |

Empirical study |

Mortality awareness (vs. control) accelerated subjective time perception (F (3, 243) = 255.47, p = 0.001, partial η2 = 0.76) and reduced delay discounting (t(121) = −3.04, p = 0.003, Cohen’s d = 0.55), supporting adaptive time management by showing that death cues foster a “time-flies” perception that promotes future-oriented choices. |

- |

- |

|

[15] Xiao, Peng, & Wang (2025). Intertemporal meditation regulates time perception and emotions: an exploratory fNIRS study. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. |

Empirical study |

Intertemporal meditation accelerates time perception (t(34) = 4.05, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.56). It increases peace (F(6, 394) = 18.11, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.22), with left prefrontal activation (e.g., Broca’s area 9: Cohen’s d = 2.60), demonstrating the adaptive regulation of time and emotion. |

- |

- |

|

[16] Greenberg, Solomon, & Pyszczynski (1997). Terror management theory of self-esteem and cultural worldviews: empirical assessments and conceptual refinements. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. |

Review |

- |

Outlines terror management theory: mortality salience triggers defensive responses (self-esteem and worldview defenses). |

- |

|

[17] Greenberg, Pyszczynski, & Solomon (1986). The causes and consequences of a need for self-esteem: a terror management theory. Public Self and Private Self. |

Review |

- |

The original articulation of terror management theory proposed self-esteem as an anxiety buffer against death awareness. |

- |

|

[18] Pyszczynski et al. (2000). Proximal and distal defense: a new perspective on unconscious motivation. Current Directions in Psychological Science. |

Review |

- |

Differentiates proximal (immediate) vs. distal (symbolic) defenses engaged by mortality salience. |

- |

|

[19] Friedman & Rholes (2007). Successfully challenging fundamentalist beliefs results in increased death awareness. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. |

Empirical study |

- |

Undermining fundamentalist worldview beliefs increased death-thought accessibility (β = −0.39, t(211) = 2.04, p < 0.050), consistent with terror management theory’s anxiety-buffering hypothesis. |

- |

|

[20] Shipp et al. (2009). Conceptualization and measurement of temporal focus: the subjective experience of the past, present, and future. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. |

Empirical study |

- |

- |

Defines temporal focus as an individual-differences construct. |

|

[21] Carstensen, Fung, & Charles (2003). Socioemotional selectivity theory and the regulation of emotion in the second half of life. Motivation and Emotion. |

Review |

Limited time horizons in older adulthood can shift goals toward emotional meaning, consistent with adaptive time management’s view on active time management when confronted with mortality cues. |

- |

- |

|

[22] Carstensen et al. (2011). Emotional experience improves with age: evidence based on over 10 years of experience sampling. Psychology and Aging. |

Empirical study |

Emotional experience improves with age (γ = 0.003, p < 0.001), as older adults increasingly prioritize positive, meaningful experiences, consistent with the adaptive time management view that mortality awareness fosters anticipatory emotions and adaptive regulation. |

- |

- |

|

[23] Carstensen et al. (2000). Emotional experience in everyday life across the adult life span. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. |

Empirical study |

Older adults report more positive affect profiles than younger adults, with fewer negative emotions (r = −0.29, p < 0.010 until ~60 years), supporting the adaptive time management emphasis on adaptive affective shifts in response to perceived limited time. |

- |

- |

|

[24] Lu et al. (2023). Age effects on delay discounting across the lifespan: a meta-analytical approach to theory comparison and model development. Psychological Bulletin. |

Meta-analysis |

Indicates a U-shaped trajectory of delay discounting across the lifespan (Fisher’s z = −0.059, turning point ≈ 50 years), supporting adaptive time management’s view that age calibrates life-history trade-offs in present–future preferences. |

- |

- |

|

[25] Shah, Mullainathan, & Shafir (2012). Some consequences of having too little. Science. |

Empirical study |

Perceived scarcity of resources (time or money) increases present-focused choices and steepens delay discounting (Exp. 1: F(1, 54) = 4.16, p < 0.050, partial η2 = 0.07; Exp. 3: F(1, 102) = 22.39, p < 0.001), suggesting that scarcity cues bias attention toward short-term rewards at the cost of long-term investment. |

- |

- |

|

[26] Rosati (2017). Foraging cognition: reviving the ecological intelligence hypothesis. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. |

Review |

In nonhuman primates, harsh or unpredictable environments favor immediate returns, showing that environmental harshness promotes fast strategy. |

- |

- |

|

[27] Stephens & Krebs (1986). Foraging theory. Princeton University Press. |

Review |

Optimal foraging under environmental constraints illustrates how harsh conditions can favor fast, immediate-return strategies. |

- |

- |

|

[28] Liu, Wolfe, & Trueblood (2024). Risky hybrid foraging: the impact of risk, reward value, and prevalence on foraging behavior in hybrid visual search. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. |

Empirical study |

Hybrid foraging studies show strong risk aversion but context-dependent shifts toward risk-seeking when high-EV options are available (e.g., F(3, 79.5) = 88.55, p < 0.001; t(2088) = 8.51, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.37), supporting adaptive time management’s view that adaptive time–risk trade-offs are shaped by environmental reward structure (i.e., harshness). |

- |

- |

|

[29] Wang & Johnson (2012). A tri-reference point theory of decision making under risk. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. |

Empirical study |

Decision references include not only the status quo and goals but also survival and subsistence requirements, highlighting adaptive resource management under mortality cues—consistent with the view that mortality awareness guides adaptive time management by informing the setting of minimum requirements. |

- |

- |

|

[30] Suddendorf, Addis, & Corballis (2009). Mental time travel and the shaping of the human mind. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. |

Review |

- |

- |

Argues that the evolution of prospection (episodic future thinking) fundamentally shaped human cognition by enabling humans to simulate future scenarios and prepare adaptive present–future trade-offs. |

|

[31] Wang, Wang, & He (2021). The hypothesis of anticipatory emotions as information for social risks: examining emotional and cultural mechanisms of risky decisions in public. Advances in Psychological Science. |

Review |

- |

- |

Introduced anticipatory emotions that serve as inputs to social risk decisions and influence choices beyond cognitive calculations. |

|

[32] Wang et al. (2022). Episodic future thinking and anticipatory emotions: effects on delay discounting and preventive behaviors during COVID-19. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being. |

Empirical study |

Imagining personal infection (vs. control) increased future orientation and preventive intentions by reducing delay discounting (F(1, 488) = 4.31, p = 0.038, partial η2 = 0.009) and enhancing preventive behaviors (F(1, 489) = 7.02, p = 0.008, partial η2 = 0.014), showing that anticipatory emotions recalibrate present–future trade-offs under mortality awareness. |

- |

- |

|

[33] Grant & Wade-Benzoni (2009). The hot and cool of death awareness at work: mortality cues, aging, and self-protective and prosocial motivations. Academy of Management Review. |

Review |

Distinguishes death reflection as a “cool” cognitive process that channels mortality awareness into prosocial, future-oriented goals (e.g., generativity, legacy), demonstrating positive effects of death awareness. |

Differentiates death anxiety as a “hot” experiential process that heightens self-protective motives, in line with terror management theory’s account of mortality cues triggering defensive reactions. |

- |

|

[34] Hofer (2013). Appreciation and enjoyment of meaningful entertainment. Journal of Media Psychology. |

Empirical study |

Meaningful media content can increase life appreciation, especially under a search for meaning, consistent with adaptive time management’s view that reflection fosters positive anticipatory emotions. |

- |

- |

|

[35] Pouthas & Perbal (2004). Time perception depends on accurate clock mechanisms as well as unimpaired attention and memory processes. Acta Neurobiologiae Experimentalis. |

Empirical study |

- |

- |

Demonstrates that internal timing (“clock”) and attentional processes jointly determine subjective time perception. |

|

[36] Wittmann & Paulus (2008). Decision making, impulsivity and time perception. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. |

Review |

- |

- |

Reviews links between time perception and impulsivity in decision making, suggesting that altered time perception can modulate impulsive choices. |

|

[37] Zakay & Block (1997). Temporal cognition. Current Directions in Psychological Science. |

Review |

- |

- |

Summarizes research on how humans perceive time, providing foundational concepts for subjective time perception. |

|

[38] Kim & Zauberman (2009). Perception of anticipatory time in temporal discounting. Journal of Neuroscience, Psychology, and Economics. |

Empirical study |

- |

- |