The Double Face of Exosomes Derived from Mesenchymal Stromal Cells in Fibrotic Lung Diseases: Pathology Contribution or Treatment?

Received: 23 December 2025 Revised: 14 January 2026 Accepted: 22 January 2026 Published: 28 January 2026

© 2026 The authors. This is an open access article under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

1. Introduction

Fibrotic lung diseases encompass a wide range of conditions. Various causes, such as genetic predisposition, underlying autoimmune diseases, environmental exposures or even drugs may induce damage to the lung parenchima, finally causing stiffness of the interstitium and progressive fibrosis. However, in the case of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis (IPF), the most aggressive form of Intersitial Lung Disease (ILDs), that is considered the prototype of these group of disorders, the etiology is still unknown [1]. Several ILD subtypes have pathophysiological and morphological features in common. It is believed that in certain ILD the primary damage to alveolar epithelial cells is usually followed by activation and differentiation of fibroblasts into myofibroblasts: after sustained proliferation these cells further lead to an excessive accumulation of extracellular matrix (ECM) in the interstitial space of the lung. In others ILDs, instead, the activation of pro-inflammatory signals in the lung parenchyma may, under certain circumstances, develop toward the fibro-proliferative pathway. The complex interplay between alveolar or epithelial cells, inflammatory cells and fibroblasts appears therefore pivotal in regulating extracellular matrix remodeling and deposition. In the recent years it has become evident that exosomes, cell-released nanosized particles, have a prominent role in the intercellular communications among various cell subtypes. Exosomes, comprising a ceramide- and cholesterol-rich lipid bilayer membrane [2], an array of membrane and cytosolic proteins [3] and selected RNA species [4], mediate a variety of physiological functions through different mechanisms. Increasing evidences have currently demonstrated that in IPF, exosomes, released within the affected microenvironment, may stimulate fibroblasts activation or either epithelial mesenchymal transition (EMT). However, on the other hand, exosomes derived from mesenchymal stromal cells (MSC) may have a regenerative and therapeutic potential depending on their origin [5,6,7,8]. We would like to focus here on the dual role played by exosomes or microvescicles to promote or, on the contrary, to counteract lung fibrosis in ILDs. To date a deeper comprehension of the molecules and mechanisms involved in these processes appears of great importance to devise novel therapeutic strategies.

2. Exosomes in the Pathogenesis of Lung Fibrosis and Their Potential as Disease Biomarker

The term exosome was used for the first time in 1987 [9]. Exosomes are released from late endosomes called multivesicular bodies bearing intraluminal vesicles (ILVs) intracellularly. When multivesicular bodies fuse with the plasma membrane and empty their contents, ILVs are released and are termed exosomes once they are extracellular. Exosomes are the smallest extracellular particles naturally released by cells with a size of 30–100 nm, while microvesicles, derived from the outward blebbing of the plasma membrane, show a bigger size of 0.1–1 μm. Exosomes and microvesicles, collectively referred to as extracellular vesicles (EVs), are the two main classes of submicroscopic vesicle released into the extracellular space by various cellular types: they facilitate the cell to cell cross-talk trough the transfer of the parental cell-derived cargos (proteins, mRNAs, non-coding RNAs, lipids) to the recipient cell, or trough ligands/receptors engagement or either through the expression of soluble mediators. In the last years various studies have suggested the potential involvement of exosomes or microvesicles in lung fibrotic progression. Differences between the molecular load and amount of EVs have been observed in the microenvironment of the diseased lung, potentially due to the IPF development and stress conditions such as inflammation and oxidative stress. Martin-Medina A. et al. [10] reported for the first time that EVs were increased in experimental and human pulmonary fibrosis: the characterization of EVs derived from broncho-alveolar lavage (BAL) collected from bleomycin (BLM)-treated or untreated mice, as well as from IPF or healthy controls subjects, revealed the presence of a larger amount of EVs, in particular exosomes, in BAL from treated mice or from IPF patients, as compared with BAL of controls. They further observed increased levels of WNT5A in EVs from patients with IPF with respect to EVs from non-IPF patients. Given the well-known involvement of Wnt-family members in tissue development, as well as in epithelial-mesenchymal transition, this finding seems pivotal in demonstrating that the enhanced WNT5A cargo in fibroblast-EVs may mediate fibroblast proliferation in an autocrine manner, as already suggested in the most recent literature [11,12]. In addition EVs from lung fibroblasts of IPF patients induce mitochondrial damage and senescence of human bronchial epithelial cells (HBEC) through the transferring of specific transcriptional inhibitory microRNA (miR-23b-3p and miR-494–3p) [13]. Moreover, senescent fibroblasts, typically observed in IPF, release fibronectin (FN)-enriched-EVs and promote an invasive phenotype trough FN/α5β1 integrin interaction in recipient fibroblasts [14]. Interestingly, Burgy O. et al. [15], through the integration of proteomic analysis and single-cell RNA-Seq data, proposed fibroblasts as the most significant source of EVs in lung fibrosis: they further evidenced SFRP1 (Secreted Frizzled-Related Protein-1) as a critical mediator of the profibrotic function of fibroblast-derived-EVs in lung fibrosis, possibly acting, once more, through the WNT-mediated pathway [16]. Extracellular vesicles may further favor lung cancer development in patients with IPF. It is well known that IPF patients have a higher susceptibility to develop lung cancer [17]. Yu Fujita et al. demonstrated that EVs derived from lung fibroblasts of IPF patients showed markedly altered microRNA compositions and stimulate proliferation of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cells. They suggested that the observed enrichment of miR-19a in IPF-derived EVs contributes to cancer progression through regulation of the zinc finger MYND-type containing 11 (ZMYND11)/c-MYC signaling pathway, [18]. The study from Yugiong Lei et al., also evidenced that exosomes derived from senescent IPF lung fibroblasts promote NSCLC cells proliferation through the up-regulation of senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) factors, in particular by the overexpression of Matrix Metalloproteinase 1 (MMP1), which may exert its collagen-degradative activity within the tissue microenvironment as well as contribute to fibroblasts senescence through the activation of the PAR1-mediated PI3K-AKT-mTOR pathway [19]. Extracellular vesicles also represent potential biomarkers for pulmonary fibrosis: various biofluids, such as serum, blood, BAL or sputum can be studied for their diagnostic or prognostic value. Indeed Makon-Sébastien Njock et al. [20], through a comparative analyses of healthy subjects and patients, reported a substantial modification in the composition of the miRNA cargos of exosomes derived from patients further identifying three promising biomarkers (miR-142-3p, miR-33a-5p, let-7d-5p) as potential diagnostic candidates useful for disease establishment. Kadota T. et al. [13] further described that EVs derived from IPF lung fibroblasts contain elevated levels of miR-23b-3p and miR-494-3p that correlated positively with IPF disease severity. In the study of D’Alessandro M. et al. [21] BAL-derived- EVs from IPF, Hypersensitivity Pneumonitis (HP) and sarcoidosis patients were phenotyped by flow cytometric analysis: some EVs surface markers such as CD56, CD105, CD142, CD31 and CD49e resulted exclusively expressed in IPF patients, while EVs-HP showed only CD86 and CD24. Moreover, EVs-HP and EVs-sarcoidosis shared some markers such as CD11c, CD1c, CD209, CD4, CD40, CD44 and CD8. These results, taken together, corroborate the hypotheses of different fibrotic phenotypes in HP and IPF: the former is related to cell-mediated inflammation and the latter is more often due to tissue repair and remodeling. CD44, in BAL fluids from patients with diffuse parenchymal lung disease, was also identified as a reliable biomarker of pulmonary fibrosis since biochemical and biophysical characterizations revealed an exosomal origin of CD44 [22].

Although the potential of EVs as biomarkers in certain stages of fibrotic lung diseases appears quite interesting, more explorations are however needed today to determine whether EVs components are sufficiently specific to be used diagnostically or prognostically for disease staging.

3. Mesenchymal Stromal Cells-Derived Exosomes as a Promising Therapeutic Approach for Lung Fibrosis

Given the limited options to cure lung fibrosis, novel therapeutic approaches are urgently needed. From this point of view, over the last few years, mesenchymal stromal cells have been proposed as a potential therapy to repair and regenerate the lung tissue. Mesenchymal stromal cells isolated from bone marrow, adipose, placental, and other tissues can, after either systemic or direct airway administration, ameliorate inflammation and injury in a wide range of preclinical disease models [23,24,25]. Mesenchymal stromal cells can regulate the activity, function, and proliferation of several immune cells, (neutrophils, regulatory and effector T cells, macrophages, and dendritic cells) or either cytokines (i.e., TGFβ, PDGFβ, CNTGF, IL1β, IL6) involved in multiple inflammatory pulmonary disorders. The efficacy of MSCs therapy may however depend on many factors, such as the type of disease, the dosing regimen or either MSCs features and source. MSCs isolated from any given tissue source constitute in fact a heterogeneous population of cells with different attributes and potential therapeutic. It has been indeed observed that the MSCs with progenitor features were more protective than those with fibroblastic characteristics [25,26,27]. Although the mechanism of actions of MSCs in lung diseases have not yet been fully elucidated the beneficial effects appears to be mainly dependent on release of bioactive molecules such as cytokines or either EVs. In comparison with MSCs-therapy, today, the use of MSCs-derived-EVs (MSC-EVs) for treatment of lung fibrosis may represent a safer approach. MSC-EVs may in fact mimic the therapeutic capabilities of MSCs but overcome low rates of engraftments and maintain reduced immunogenic or tumorigenic property. In vitro experiments, preclinical studies and clinical trials have demonstrated the considerable therapeutic effects of MSC-EVs. Wang et al. explored the activity of exosomes derived from MSC in the pre-clinical model in vivo of lung fibrosis induced by radiation in the Sprague-Dawley rats, and also in vitro by the use of two irradiated cell lines (RLE-6TN, BEAS-2B) [28]. The Authors here demonstrated that MSCs-exosomes alleviate radiation-induced fibrosis by inhibiting inflammatory responses, epithelial mesenchymal transition (EMT) processes and ECM deposition. In agreement with these observations, Chen W. et al. also reported that exosomes derived from bone marrow stromal cells (BMSCs) inhibited EMT in the BLM-induced mouse model of pulmonary fibrosis: MSC-exosomes appear in fact to regulate NOD1/NF-kB (Nucleotide-binding Oligomerization Domain-containing protein 1/Nuclear Factor Kappa-Light chain enhancer of activated B cells) signaling pathway to suppress the activation of NLRP3 (NLR family pyrin domain containing 3) inflammasomes both in vivo and in vitro [29]. Furthermore, Charoenphannathon J.S. and collaborators recently reported that BMSCs-EVs attenuated TGFβ-stimulated collagen I deposition from human dermal and non-IPF patient-derived lung myofibroblast. Similarly, BMSC-EVs therapeutically reduced myofibroblast differentiation and type I collagen deposition in a murine model of bleomycin-induced lung fibrosis. BMSC-EVs appeared also to promote the balance between MMP-9 activity over TIMP-1 (Tissue Inhibitor of Metalloproteinase-1) levels in the lung: it is indeed of note that MMP9/TIMP1 ratio can mirror the rate of fibrosis in ILDs [30]. However in this study it has been also observed that the anti-fibrotic efficacy of these BMSC-EVs was not observed when administered to fibroblasts isolated from patients with advanced IPF, potentially due to high levels of TGFβ commonly found in IPF myofibroblasts [31].

Exosomes mitigate fibrosis by delivering miRNAs [32]; indeed various miRNAs appear involved in fibrotic processes of the lung and may participate in maintaining homeostasis of the lung tissue. Zhou et al. through in vitro and in vivo experiments demonstrated that miR186 is down-regulated in IPF but enriched in EVs derived from BMSCs: miR186 delivered by BMSC-EVs therefore inhibited the proliferation, invasion and differentiation of fibroblasts by down-regulating the expression of SOX4 and DKK1 [33]. BMSCs-derived-EVs overexpressing mir29b-3p were also capable of suppressing fibroblast activation in IPF [34]. Moreover, by analyzing collagen gel contraction, cell migration and α-smooth muscle actin expression, Sumiyoshi et al. demonstrated that the anti-fibrotic mechanism of MSCs-EVs in lung fibroblasts was associated with miR-4516 delivery, through integrin αV-mediated FAK signaling following the MAPK pathway. Interestingly lung fibroblasts derived from fibrotic lungs showed greater inhibition of responses than normal lung fibroblasts. These MSCs-EVs further attenuated BLM-induced pulmonary fibrosis, which was accompanied by a reduction of integrin αV expression in the lung interstitium [35].

As above discussed, lung resident MSCs might contribute to lung fibrosis pathogenesis as they might differentiate into myofibroblasts after lung damage. However, due to their great heterogeneity it is also possible that some MSCs may instead favor lung tissue repair. On this view telocytes (TCs), a recently discovered type of mesenchymal or interstitial cells, appear to be involved in maintaining tissue homeostasis and facilitating tissue regeneration [36]. Telocytes have been found in numerous organs/tissues, especially under airway epithelial cells and interstitial tissues of lungs. Here they mediate the cross-talk among multiple cells through their long characteristic cell protrusion called telopodes. The formation of extensive intercellular connections in the mesenchyme and the function of exocrine vesicles are the biological or physical basis for TCs to perform cellular functions. It has been further shown that these cells may mediate this function through the transfer of mitochondria in [37]. It is worth noting that lung TCs exhibit distinct gene and protein expression profiles that distinguish them from other mesenchymal cell populations: in addition, among the genes that appear selectively up-regulated, they display FHL2 (Four-and-a-Half LIM domains 2), a gene associated with attenuation of fibrotic pathways, and QSOX1 (Quiescin Sulfhydryl Oxidase 1), involved in ECM remodeling; collectively this data suggests that TCs may protect from inflammation and fibrosis in lung diseases [38,39,40]. Intra-tracheal administration of activated TCs has also been shown to alleviate ventilator-induced lung injury in a mouse model through the release of angiogenic factors [41]. Moreover, telocytes, derived from rat lung tissue and co-cultured with rat tracheal epithelial cells, were capable of inhibiting TGFβ-induced EMT through the secretion of hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) [42]. The efficacy of exosomes-derived-TCs has been preliminarily assessed in acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) showing that miR221, increased in TCs-exosomes after LPS stimulation, promoted angiogenesis and reduced inflammation [43]. Altogether in vitro and in vivo preclinical models have therefore demonstrated that TCs transplantation, or the administration of TCs-derived exosomes, might be useful to counteract fibrogenesis in the lung. Future research should however provide a deeper understanding of the molecular mechanisms regulating TCs-anti-fibrotic activity and, in parallel, explore novel strategies for TCs isolation and expansion.

4. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

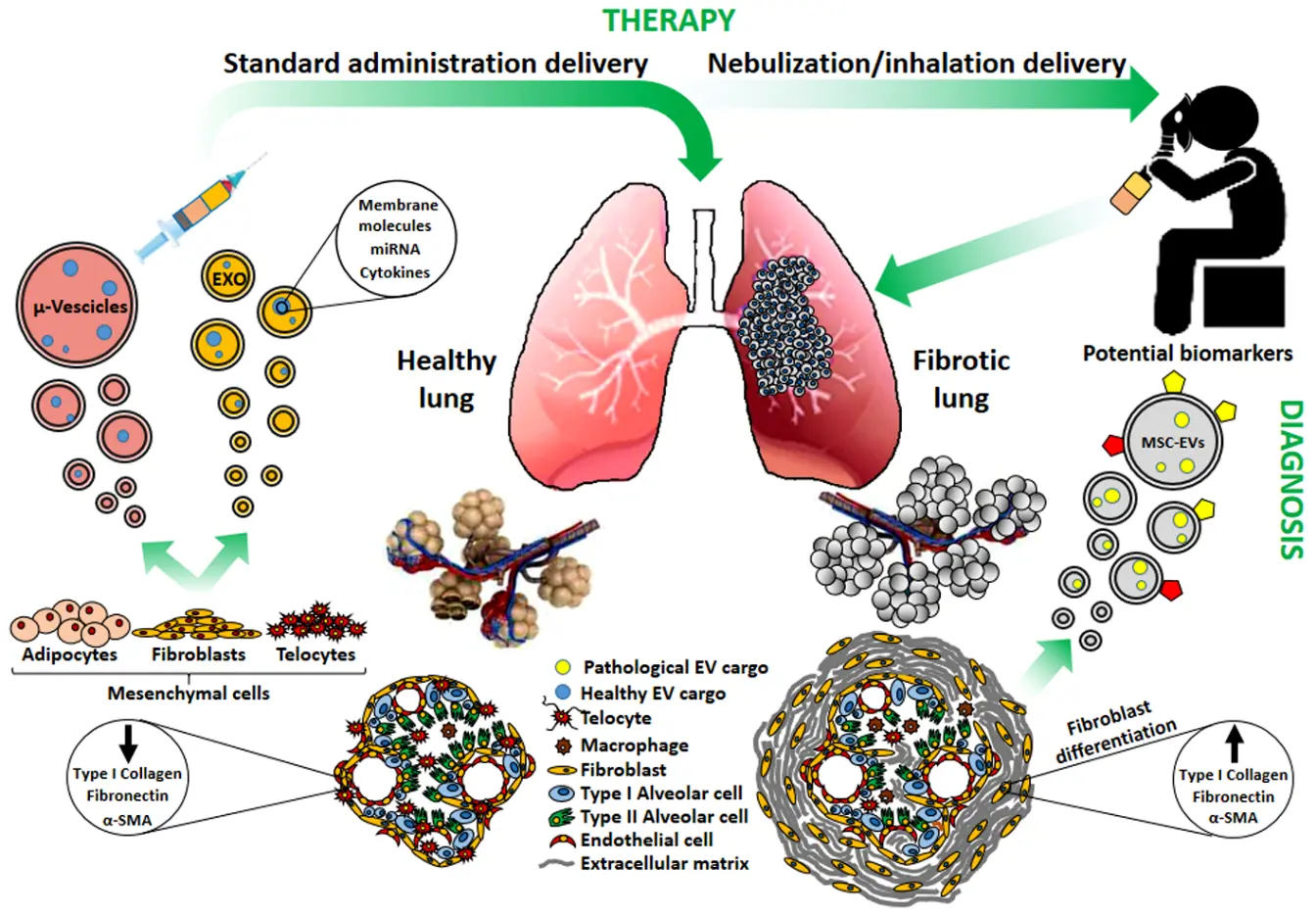

It is evident that MSCs have strong plasticity and in pulmonary fibrosis may act as a double-edged sword: indeed, microvesicles or exosomes derived from MSCs may promote or antagonize fibrosis in association with the microenvironment changes (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1. A different physio-pathological condition of the lung (Healty vs. Fibrotic) is evidenced by a modified morphology of the alveolar structure and of the constituent cell types involved, which diversely contribute to the microenvironment modification and fibrotic progression. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vescicles (MSCs-EVs; microvescicles and exosomes) released from healthy mesenchymal cells/tissues may contribute to lung repair and could be prospectively envisaged in nebulization/inhalation-based therapeutic approaches, whereas EVs released from resident fibrotic tissues could be sources of yet undisclosed biomarkers useful for diagnostic purposes. EXO: exosomes; μ-Vescicles: micovescicles; α-SMA: smooth muscle actin.

Exosomes or microvesicles may therefore represent feasible biomarkers for patients’ diagnosis and, at the same time, a useful new tool for therapy, when derived from MSCs of healthy subjects. In addition, strategies to bio-engineer EVs have also raised a great interest to enhance their targeting, potency and consistency [32]. However, the clinical application of MSC-derived-EVs to treat pulmonary fibrosis has been rather limited to date. One registered clinical trial (NCT05191381), is currently investigating intravenous administration of MSC-derived exosomes in patients with pulmonary fibrosis after COVID-19: this trial is still recruiting patients (18–90 years) and, to date, no results have been published [44]. The results from another phase l clinical trial involving twenty-four patients in a randomized, single-blind, and placebo-controlled study (MR-46-22-004531, ChiCTR2300075466), where pulmonary fibrosis was treated by nebulization of human umbilical cord-EVs (hUCMSC-EVs), evidenced that patients receiving the combined therapy of nebulized hUCMSC-EVs and routine treatment show significant improvements in both lung function indices (forced vital capacity and maximal voluntary ventilation) and respiratory health status [45].The Authors have here suggested that hUCMSC-EVs have a complementary effect under the routine treatment for pulmonary fibrosis patients (COPD with fibrosis, IPF, ILD, or post-inflammatory pulmonary fibrosis): although no intergroup differences were observed across pulmonary fibrosis subtypes, two patients with post-inflammatory pulmonary fibrosis exhibited significant radiologic improvement. It is of further interest to highlight that the nebulized/inhalation delivery allows for the direct deposition of therapeutic MSCs-EVs in the lung, maximizing their local concentration, minimizing systemic adverse effects and enhancing patient compliance in lung fibrosis management. Investigations on vesicular proteins and noncoding RNAs as potential therapeutic components within MSCs-EVs appears therefore an emergent field to be disclosed for managing chronic respiratory diseases. However it should also be noted that new insights need to be disclosed and deepened with respect to the possible variable cargos of the EVs, given the wide scenario of mesenchymal cell sources available (see for ex. [46,47,48]), or given the different cell response on EVs coming from different sources [49]. Before full clinical implementation, the development of EV-based therapeutics needs to cope with several production, isolation, and characterization requirements, including the quality of the final product, therapeutic potential preservation during disease severity worsening and dose-scalability. Moreover, in addition to the cargo and source issues, it should be considered that in vitro potency assays do not necessarily predict the therapeutic effect in vivo, as well as the use of EVs in animal models may not predict the same efficacy in human therapeutic approaches [50].

Hence further researches are warranted to address standardization of MSCs-EVs isolation and large-scale production, establishing robust clinical trials design to drive this new challenging therapeutic approach to its practical application.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.d.T.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, D.d.T., P.G.; Writing—Review & Editing, D.d.T., P.G., M.G., E.B.; Visualization, P.G.; Supervision, E.B., D.d.T.

Ethics Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was partially funded by 5X1000 year 2022, grant # C809A (to E.B.).

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

-

Althobiani MA, Russell AM, Jacob J, Ranjan Y, Folarin AA, Hurst JR, et al. Interstitial lung disease: A review of classification, etiology, epidemiology, clinical diagnosis, pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatment. Front. Med. 2024, 11, 1296890. DOI:10.3389/fmed.2024.1296890 [Google Scholar]

-

Trajkovic K, Hsu C, Chiantia S, Rajendran L, Wenzel D, Wieland F, et al. Ceramide triggers budding of exosome vesicles into multivesicular endosomes. Science 2008, 319, 1244–1247. DOI:10.1126/science.1153124 [Google Scholar]

-

Simpson RJ, Lim JW, Moritz RL, Mathivanan S. Exosomes: Proteomic insights and diagnostic potential. Expert Rev. Proteom. 2009, 6, 267–283. DOI:10.1586/epr.09.17 [Google Scholar]

-

Valadi H, Ekstrom K, Bossios A, Sjostrand M, Lee JJ, Lotvall JO. Exosome-mediated transfer of mRNAs and microRNAs is a novel mechanism of genetic exchange between cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 2007, 9, 654–659. DOI:10.1038/ncb1596 [Google Scholar]

-

Dinh PC, Paudel D, Brochu H, Popowski KD, Gracieux MC, Cores J, et al. Inhalation of lung spheroid cell secretome and exosomes promotes lung repair in pulmonary fibrosis. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1064. DOI:10.1038/s41467-020-14344-7 [Google Scholar]

-

Lopes-Pacheco M. Extracellular Vesicles: Multimodal Tools for Diagnosis, Prognosis, and Therapy in Respiratory Diseases. Expert Rev. Mol. Med. 2025, 27, e38. DOI:10.1017/erm.2025.10025 [Google Scholar]

-

Nija RJ, Nithya TG. Pulmonary fibrosis and exosomes: Pathways to treatment. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2025, 52, 749. DOI:10.1007/s11033-025-10855-y [Google Scholar]

-

Wang J, Shi Y, Su Y, Pang C, Yang Y, Wang W. Research advances of extracellular vesicles in lung diseases. Cell Transplant. 2025, 34, 9636897251362031. DOI:10.1177/09636897251362031 [Google Scholar]

-

Johnstone RM, Adam M, Hammond JR, Orr L, Turbide C. Vesicle formation during reticulocyte maturation. Association of plasma membrane activities with released vesicles (exosomes). J. Biol. Chem. 1987, 262, 9412–9420. DOI:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)48095-7 [Google Scholar]

-

Martin-Medina A, Lehmann M, Burgy O, Hermann S, Baarsma HA, Wagner DE, et al. Increased Extracellular Vesicles Mediate WNT5A Signaling in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2018, 198, 1527–1538. DOI:10.1164/rccm.201708-1580OC [Google Scholar]

-

Singla A, Reuter S, Taube C, Peters M, Peters K. The molecular mechanisms of remodeling in asthma, COPD and IPF with a special emphasis on the complex role of Wnt5A. Inflamm. Res. 2023, 72, 577–588. DOI:10.1007/s00011-023-01692-5 [Google Scholar]

-

Zhang X, Liu X, Noble PW. From fibroblast foci to dense scars: PAK2-activated fibroblasts drive fibrosis progression in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Eur. Respir. J. 2025, 66, 2501549. DOI:10.1183/13993003.01549-2025 [Google Scholar]

-

Kadota T, Yoshioka Y, Fujita Y, Araya J, Minagawa S, Hara H, et al. Extracellular Vesicles from Fibroblasts Induce Epithelial-Cell Senescence in Pulmonary Fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2020, 63, 623–636. DOI:10.1165/rcmb.2020-0002OC [Google Scholar]

-

Chanda D, Thannickal VJ. Modeling Fibrosis in Three-Dimensional Organoids Reveals New Epithelial Restraints on Fibroblasts. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2019, 61, 556–557. DOI:10.1165/rcmb.2019-0153ED [Google Scholar]

-

Burgy O, Mayr CH, Schenesse D, Fousekis Papakonstantinou E, Ballester B, Sengupta A, et al. Fibroblast-derived extracellular vesicles contain SFRP1 and mediate pulmonary fibrosis. JCI Insight 2024, 9, e168889. DOI:10.1172/jci.insight.168889 [Google Scholar]

-

Mayr CH, Sengupta A, Asgharpour S, Ansari M, Pestoni JC, Ogar P, et al. Sfrp1 inhibits lung fibroblast invasion during transition to injury-induced myofibroblasts. Eur. Respir. J. 2024, 63, 2301326. DOI:10.1183/13993003.01326-2023 [Google Scholar]

-

Czyzak B, Majewski S. Concomitant Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis and Lung Cancer: An Updated Narrative Review. Adv. Respir. Med. 2025, 93, 31. DOI:10.3390/arm93040031 [Google Scholar]

-

Fujita Y, Fujimoto S, Miyamoto A, Kaneko R, Kadota T, Watanabe N, et al. Fibroblast-derived Extracellular Vesicles Induce Lung Cancer Progression in the Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis Microenvironment. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2023, 69, 34–44. DOI:10.1165/rcmb.2022-0253OC [Google Scholar]

-

Lei Y, Zhong C, Zhang J, Zheng Q, Xu Y, Li Z, et al. Senescent lung fibroblasts in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis facilitate non-small cell lung cancer progression by secreting exosomal MMP1. Oncogene 2025, 44, 769–781. DOI:10.1038/s41388-024-03236-5 [Google Scholar]

-

Njock MS, Guiot J, Henket MA, Nivelles O, Thiry M, Dequiedt F, et al. Sputum exosomes: Promising biomarkers for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Thorax 2019, 74, 309–312. DOI:10.1136/thoraxjnl-2018-211897 [Google Scholar]

-

d’Alessandro M, Gangi S, Soccio P, Canto E, Osuna-Gomez R, Bergantini L, et al. The Effects of Interstitial Lung Diseases on Alveolar Extracellular Vesicles Profile: A Multicenter Study. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 4071. DOI:10.3390/ijms24044071 [Google Scholar]

-

Suchankova M, Zsemlye E, Urban J, Barath P, Kohutova L, Sivakova B, et al. The bronchoalveolar lavage fluid CD44 as a marker for pulmonary fibrosis in diffuse parenchymal lung diseases. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1479458. DOI:10.3389/fimmu.2024.1479458 [Google Scholar]

-

Curley GF, O’Kane CM, McAuley DF, Matthay MA, Laffey JG. Cell-based Therapies for Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome: Where Are We Now? Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2024, 209, 789–797. DOI:10.1164/rccm.202311-2046CP [Google Scholar]

-

Ting AE, Baker EK, Champagne J, Desai TJ, Dos Santos CC, Heijink IH, et al. Proceedings of the ISCT scientific signature series symposium, “Advances in cell and gene therapies for lung diseases and critical illnesses”. International Society for Cell & Gene Therapy, Burlington VT, US, July 16, 2021. Cytotherapy 2022, 24, 774–788. DOI:10.1016/j.jcyt.2021.11.007 [Google Scholar]

-

Weiss DJ. Unraveling the Complexities of Mesenchymal Stromal Cell-based Therapies: One Size Doesn’t Fit All. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2024, 210, 709–711. DOI:10.1164/rccm.202405-0961ED [Google Scholar]

-

Cyr-Depauw C, Cook DP, Mizik I, Lesage F, Vadivel A, Renesme L, et al. Single-Cell RNA Sequencing Reveals Repair Features of Human Umbilical Cord Mesenchymal Stromal Cells. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2024, 210, 814–827. DOI:10.1164/rccm.202310-1975OC [Google Scholar]

-

Wang Q, Li J, Wang S, Deng Q, Wang K, Dai X, et al. Single-cell transcriptome profiling reveals molecular heterogeneity in human umbilical cord tissue and culture-expanded mesenchymal stem cells. FEBS J. 2021, 288, 5311–5330. DOI:10.1111/febs.15834 [Google Scholar]

-

Wang LL, Ouyang MY, Yang ZE, Xing SN, Zhao S, Yu HY. Mesenchymal stem cells-derived exosomes alleviate radiation induced pulmonary fibrosis by inhibiting the protein kinase B/nuclear factor kappa B pathway. World J. Stem Cells 2025, 17, 106488. DOI:10.4252/wjsc.v17.i6.106488 [Google Scholar]

-

Chen W, Peng J, Tang X, Ouyang S. MSC-derived exosome ameliorates pulmonary fibrosis by modulating NOD 1/NLRP3-mediated epithelial-mesenchymal transition and inflammation. Heliyon 2025, 11, e41436. DOI:10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e41436 [Google Scholar]

-

Bertolotto M, de Totero D, Giannoni P, Barisione E, Grosso M, Nano E, et al. Fibroblast-driven MMP-9/TIMP-1 imbalance in bronchoalveolar lavage reflects fibrotic progression in interstitial lung disease. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2025, 56, e70162. DOI:10.1111/eci.70162 [Google Scholar]

-

Charoenphannathon JS, Wong PD, Royce SG, Jaffar J, Westall GP, Wang C, et al. Human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles induce inverse dose-dependent anti-fibrotic effects in human myofibroblast cultures and bleomycin-injured mice with pulmonary fibrosis. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2025, 190, 118370. DOI:10.1016/j.biopha.2025.118370 [Google Scholar]

-

Chen Y, Li M, Yang J, Chen Y, Wang J. Engineerable mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles as promising therapeutic strategies for pulmonary fibrosis. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2025, 16, 367. DOI:10.1186/s13287-025-04490-4 [Google Scholar]

-

Zhou J, Lin Y, Kang X, Liu Z, Zhang W, Xu F. microRNA-186 in extracellular vesicles from bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells alleviates idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis via interaction with SOX4 and DKK1. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2021, 12, 96. DOI:10.1186/s13287-020-02083-x [Google Scholar]

-

Wan X, Chen S, Fang Y, Zuo W, Cui J, Xie S. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles suppress the fibroblast proliferation by downregulating FZD6 expression in fibroblasts via micrRNA-29b-3p in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. J. Cell. Physiol. 2020, 235, 8613–8625. DOI:10.1002/jcp.29706 [Google Scholar]

-

Sumiyoshi I, Togo S, Watanabe J, Kaneko I, Uzu S, Yonekura T, et al. MicroRNA-4516 in extracellular vesicles-derived mesenchymal stem cells suppressed integrin alphaV-mediated lung fibrosis. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2025, 16, 442. DOI:10.1186/s13287-025-04559-0 [Google Scholar]

-

Rosa I, Romano E, Fioretto BS, Manetti M. Pathophysiologic implications and therapeutic potentials of telocytes in multiorgan fibrosis. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 2026, 38, 26–37. DOI:10.1097/BOR.0000000000001116 [Google Scholar]

-

Babadag S, Altundag-Erdogan O, Akkaya-Ulum YZ, Celebi-Saltik B. Evaluation of Tumorigenic Properties of MDA-MB-231 Cancer Stem Cells Cocultured with Telocytes and Telocyte-Derived Mitochondria Following miR-146a Inhibition. DNA Cell Biol. 2024, 43, 341–352. DOI:10.1089/dna.2024.0031 [Google Scholar]

-

Shi L, Dong N, Chen C, Wang X. Potential roles of telocytes in lung diseases. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2016, 55, 31–39. DOI:10.1016/j.semcdb.2016.02.008 [Google Scholar]

-

Wei XJ, Chen TQ, Yang XJ. Telocytes in Fibrosis Diseases: From Current Findings to Future Clinical Perspectives. Cell Transplant. 2022, 31, 9636897221105252. DOI:10.1177/09636897221105252 [Google Scholar]

-

Zheng Y, Cretoiu D, Yan G, Cretoiu SM, Popescu LM, Wang X. Comparative proteomic analysis of human lung telocytes with fibroblasts. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2014, 18, 568–589. DOI:10.1111/jcmm.12290 [Google Scholar]

-

Ma R, Wu P, Shi Q, Song D, Fang H. Telocytes promote VEGF expression and alleviate ventilator-induced lung injury in mice. Acta Biochim. Et Biophys. Sin. 2018, 50, 817–825. DOI:10.1093/abbs/gmy066 [Google Scholar]

-

Zhang S, Sun L, Chen B, Lin S, Gu J, Tan L, et al. Telocytes protect against lung tissue fibrosis through hexokinase 2-dependent pathway by secreting hepatocyte growth factor. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2023, 50, 964–972. DOI:10.1111/1440-1681.13823 [Google Scholar]

-

Gao R, Zhang X, Ju H, Zhou Y, Yin L, Yang L, et al. Telocyte-derived exosomes promote angiogenesis and alleviate acute respiratory distress syndrome via JAK/STAT-miR-221-E2F2 axis. Mol. Biomed. 2025, 6, 21. DOI:10.1186/s43556-025-00259-6 [Google Scholar]

-

Zou Y, Zhou Y, Li G, Dong Y, Hu S. Clinical applications of extracellular vesicles: Recent advances and emerging trends. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2025, 13, 1671963. DOI:10.3389/fbioe.2025.1671963 [Google Scholar]

-

Li M, Huang H, Wei X, Li H, Li J, Xie B, et al. Clinical investigation on nebulized human umbilical cord MSC-derived extracellular vesicles for pulmonary fibrosis treatment. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2025, 10, 179. DOI:10.1038/s41392-025-02262-3 [Google Scholar]

-

Isaac R, Reis FCG, Ying W, Olefsky JM. Exosomes as mediators of intercellular crosstalk in metabolism. Cell Metab. 2021, 33, 1744–1762. DOI:10.1016/j.cmet.2021.08.006 [Google Scholar]

-

O’Brien K, Breyne K, Ughetto S, Laurent LC, Breakefield XO. RNA delivery by extracellular vesicles in mammalian cells and its applications. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2020, 21, 585–606. DOI:10.1038/s41580-020-0251-y [Google Scholar]

-

Zhang J, Li S, Li L, Li M, Guo C, Yao J, et al. Exosome and exosomal microRNA: Trafficking, sorting, and function. Genom. Proteom. Bioinform. 2015, 13, 17–24. DOI:10.1016/j.gpb.2015.02.001 [Google Scholar]

-

Hagey DW, Ojansivu M, Bostancioglu BR, Saher O, Bost JP, Gustafsson MO, et al. The cellular response to extracellular vesicles is dependent on their cell source and dose. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, eadh1168. DOI:10.1126/sciadv.adh1168 [Google Scholar]

-

Maumus M, Rozier P, Boulestreau J, Jorgensen C, Noel D. Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Extracellular Vesicles: Opportunities and Challenges for Clinical Translation. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8, 997. DOI:10.3389/fbioe.2020.00997 [Google Scholar]