Therapies Targeting Metabolic Pathways in Lung Fibrosis: Advances and Future Perspectives

Received: 08 December 2025 Revised: 19 December 2025 Accepted: 20 January 2026 Published: 22 January 2026

© 2026 The authors. This is an open access article under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

1. Introduction

Pulmonary fibrosis encompasses a group of chronic interstitial lung diseases characterized by aberrant fibroblast activation, excessive extracellular matrix deposition, and progressive remodeling of lung architecture, ultimately leading to respiratory failure [1]. These disorders primarily affect older adults and are associated with poor prognosis, with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) exhibiting a median survival of only three to five years after diagnosis. Despite extensive research, the etiology of many forms of pulmonary fibrosis, including IPF, remains incompletely understood, and unpredictable clinical courses further complicate disease management.

A central pathological event in pulmonary fibrosis is the failure of effective alveolar repair. Injury to alveolar epithelial type II (AEC2) cells, which function as progenitor cells maintaining epithelial integrity, disrupts normal regeneration and promotes aberrant activation of fibroblasts. In IPF and related fibrotic lung diseases, these activated fibroblasts differentiate into myofibroblasts, leading to excessive ECM accumulation, destruction of alveolar architecture, and progressive impairment of gas exchange. Immune and endothelial cells also contribute to the establishment of a profibrotic microenvironment, reinforcing the chronic and self-sustaining nature of fibrotic remodeling.

Currently available antifibrotic drugs, pirfenidone and nintedanib, can partially slow the decline of lung function but cannot reverse established fibrosis or substantially improve long-term survival. Their limited efficacy suggests that therapies targeting classical signaling pathways—such as the transforming growth factor-β/Smad homolog (TGF-β/Smad) axis—may have reached a therapeutic plateau. These limitations highlight the need to identify additional mechanisms that drive disease progression and to explore novel therapeutic strategies.

Advances in metabolomics and single-cell transcriptomics have revealed that metabolic reprogramming is closely associated with the onset and progression of pulmonary fibrosis. Metabolic alterations not only reflect changes in energy demand but also actively promote fibrogenesis. Three major metabolic pathways—glucose, lipid, and amino acid metabolism—have gained particular attention.

Enhanced glycolysis is one of the earliest and most prominent metabolic changes in IPF and other fibrotic lung diseases. Activated fibroblasts exhibit a Warburg-like phenotype, favoring glycolysis even under normoxic conditions [2]. Accumulated lactate acts as a signaling molecule that amplifies fibrotic responses by activating TGF-β and HIF-1α, thereby supporting myofibroblast differentiation and ECM production. Lipid metabolism is also markedly dysregulated. In AEC2 cells, increased de novo lipogenesis combined with reduced fatty acid oxidation contributes to lipid droplet accumulation and mitochondrial dysfunction, thereby impairing epithelial repair. Conversely, fibroblasts enhance lipid synthesis to meet the biosynthetic demands of ECM production [1,3]. Significant abnormalities also occur in amino acid metabolism: glutamine and arginine pathways are upregulated, supplying energy and precursors for collagen synthesis. Glutamine metabolism generates α-ketoglutarate to maintain NADPH levels required for redox homeostasis [4,5], while arginine contributes to the synthesis of proline and other collagen precursors [6].

These metabolic pathways are interconnected through regulatory hubs such as mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) and HIF-1α. For example, the glycolytic enzyme PFKFB3 can activate mTOR, and oxidized lipids can stimulate TGF-β signaling, collectively amplifying metabolic and fibrotic remodeling [5]. This highly integrated network of metabolic disturbances contributes to the persistence and irreversibility of fibrotic lung diseases, including IPF.

Although many examples discussed in this review are derived from studies on idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, most metabolic alterations described are shared across fibrotic lung diseases. Therefore, this review focuses broadly on lung fibrosis while highlighting IPF as a representative and well-studied subtype.

Metabolic reprogramming not only regulates intracellular energy balance but also shapes intercellular communication within the fibrotic lung microenvironment. Metabolites such as lactate, lipid mediators, nitric oxide, and amino acid–derived compounds act as signaling molecules, influencing interactions among fibroblasts, epithelial cells, endothelial cells, and immune cells. These signals can promote fibroblast activation, hinder epithelial repair, and bias immune cells toward a profibrotic phenotype, creating a self-sustaining fibrotic niche [6]. Importantly, metabolic patterns vary between disease stages. Early-stage fibrosis is marked by enhanced glycolysis and LXR pathway activation, where inhibitors such as the PFKFB3 blocker 3PO or LXR agonists can effectively prevent fibrosis onset. Late-stage fibrosis [5], however, is dominated by disrupted amino acid metabolism, particularly glutamine and arginine pathways, supporting collagen synthesis, and thus GLS1 inhibitors offer greater therapeutic benefit at this stage. Understanding these stage-specific metabolic alterations provides insight into optimal timing and targeting of antifibrotic therapies.

2. Glucose Metabolism and Pulmonary Fibrosis

2.1. Pathological Basis of Glucose Metabolic Dysregulation in Pulmonary Fibrosis

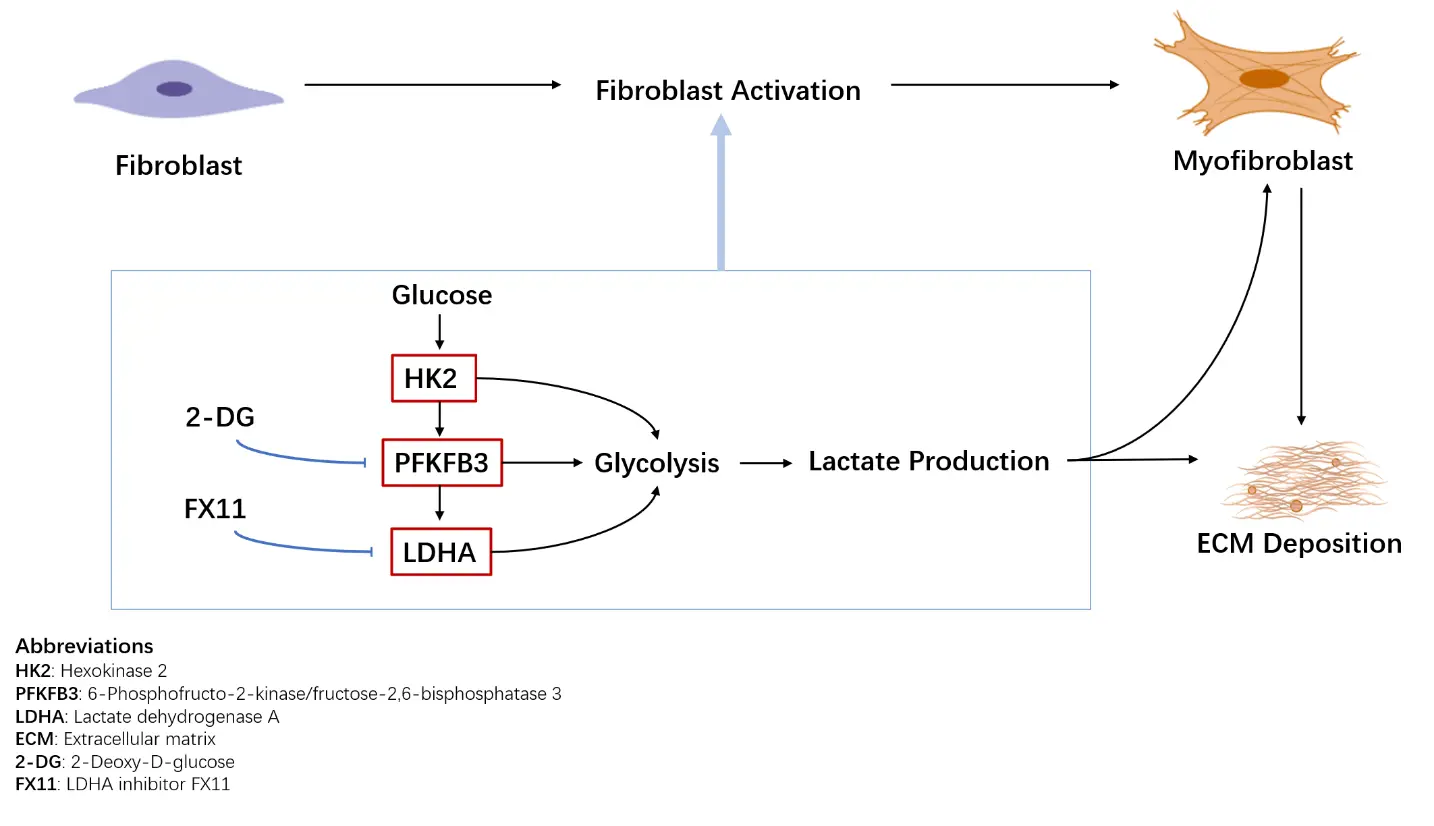

Emerging evidence suggests that glucose metabolism reprogramming is actually a key driver of the occurrence and development of pulmonary fibrosis, similar to the metabolic phenotype observed in cancer cells. In fibrotic lungs [7], ysis, even under normoxic conditions. This reminds one of the Warburg effect. After analyzing the lung tissues of patients with IPF and experimental models, it was found that the expression of glycolytic related enzymes was significantly upregulated, including hexokinase 2 (HK2), 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-bisphosphatase 3 (PFKFB3), pyruvate kinase M2 (PKM2), and lactate dehydrogenase A (LDHA). Lactic acid production and extracellular acidification also increased.

Lactic acid is not merely a metabolic by-product; it is also a highly functional signaling molecule [8]. It can promote the differentiation of fibroblasts into myofibroblasts, enhance the contractility of cells, and stimulate the deposition of extracellular matrix [9]. Lactic acid can also amplify the fibrotic response by relying on local acidification, activating the TGF-β pathway, and stabilizing HIF-1α [10]. Lactic acid can also damage the anti-inflammatory activity of macrophages, allowing the profibrotic microenvironment to persist [11].

In terms of mechanism, the mTOR pathway plays a coordinating role in this metabolic remodeling. PFKFB3 activates mTOR, which then increases the expression of glycolytic genes, establishing a PFKFB3-mTOR glycolytic positive feedback loop that maintains fibroblast activation. Besides fibroblasts, Abnormal sugar metabolism can also cause damage to the functions of other cells in the lungs [12]. In alveolar epithelial cells, elevated glycolysis can lead to endoplasmic reticulum stress, apoptosis, and impaired tissue repair [13]. In macrophages, glycolysis promotes the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines and also facilitates the recruitment of fibroblasts [14,15]. Overall, these findings suggest that metabolic reprogramming in pulmonary fibrosis is not merely an energy adaptation [16]. It is also a cross-cellular signaling event that can promote the progression of diseases. These metabolic alterations further influence intercellular communication between fibroblasts and surrounding epithelial and immune cells, amplifying profibrotic signaling within the lung microenvironment.

2.2. Key Molecular Pathways Linking Glucose Metabolism and Fibrosis

Four major signaling axes mediate the interplay between glucose metabolism and pulmonary fibrosis, promoting sustained fibroblast activation and ECM accumulation:

HIF-1α pathway: Hypoxia or lactate accumulation stabilizes HIF-1α, which transcriptionally upregulates glycolytic genes such as glucose transporter 1 (GLUT1), HK2, and LDHA, forming a positive feedback loop that amplifies glycolysis and fibrotic signaling [17].

PI3K–Akt–mTOR pathway: This pathway enhances both expression and activity of glycolytic enzymes while suppressing mitochondrial oxidative metabolism, thereby favoring glycolysis to support fibroblast proliferation and collagen biosynthesis [18,19].

TGF-β/Smad signaling: TGF-β induces PFKFB3 expression and lactate production, which, in turn, reinforce TGF-β signaling, creating a feedforward loop that accelerates ECM synthesis [20].

ATF4-mediated metabolic adaptation: Under stress conditions such as nutrient deprivation or oxidative stress [21], activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4) upregulates genes involved in glucose and one-carbon metabolism, ensuring adequate substrates for collagen and ECM production [22,23].

These pathways underscore the close integration of metabolic alterations with canonical profibrotic signaling, highlighting potential targets for therapeutic c intervention [24].

2.3. Representative Metabolic Targets and Drug Research

2.3.1. PFKFB3 Inhibition: 3PO

PFKFB3 can catalyze the formation process of fructose-2,6-diphosphate, and fructose-2,6-diphosphate is a highly active allosteric activator of PFK-1. This activator is highly expressed in activated fibroblasts and promotes collagen synthesis through mTOR activation [25]. In the LPS-induced lung injury model, the small molecule PFKFB3 inhibitor 3PO reduces the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines by alveolar macrophages. The release of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-1β will also decrease. At the same time, it can alleviate pulmonary edema and reduce collagen deposition. In addition, 3PO can also inhibit NF-κB signaling and the transdifferentiation of fibroblasts into myofibroblasts. Currently, 3PO remains in preclinical evaluation, with strategies such as lung-targeted delivery proposed to minimize off-target effects. In addition to small-molecule inhibitors like 3PO, activation of the glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor (GLP-1R) has also been shown to attenuate pulmonary fibrosis progression by disrupting NOD-like receptor family pyrin domain containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome/PFKFB3-driven glycolysis and histone lactylation, providing an alternative strategy for targeting PFKFB3-related metabolic reprogramming [26].

2.3.2. LDHA Inhibition: Gossypol

LDHA can catalyze the conversion of pyruvate into lactic acid, and this process is a key step in promoting lactic acid accumulation during the differentiation of myofibroblasts through the activation of TGF-β1. Relevant content is mentioned in references [27,28]. Gossypol is a natural LDHA inhibitor that competitively binds to the active site of the enzyme, thereby reducing lactic acid production. It can also inhibit the TGF-β1/Smad3 signaling pathway, which is also explained in reference [29]. Preclinical studies have demonstrated that gossypol has antifibrotic effects. However, gossypol has certain toxicity, such as hepatotoxicity and reproductive effects. It is necessary to develop safer analogues for its clinical application.

2.3.3. GLUT1 Inhibition: STF-31

GLUT1 can mediate the uptake of glucose by fibroblasts and is upregulated in IPF. STF-31 can reduce the availability of glycolytic substrates [30] and also inhibit the activation of mTOR and the synthesis of collagen, which are recorded in relevant literature [31,32]. Although STF-31 has demonstrated certain antifibrotic potential in in vivo model experiments, it still needs to be optimized to enhance its selectivity while minimizing its impact on GLUT1-dependent tissues as much as possible.

2.3.4. Broad Glycolysis Inhibition: 2-Deoxy-D-Glucose (2-DG)

2-DG can inhibit glycolysis over a relatively wide range and also reduce inflammatory phenomena and ECM deposition in preclinical fibrosis models [33]. However, its application in clinical practice is constrained by systemic toxicity. In tissues with a high degree of glucose dependence, if local administration is adopted, just like by inhalation or using nanoparticle carriers for drug administration, it may enhance its safety and efficacy, and it may also be used in combination therapy rather than just as a single treatment.

2.3.5. Indirect Modulation: Metformin

Metformin can inhibit the glycolytic process mediated by PFKFB3 by activating adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK)/mTOR. It can increase the AMP/ATP ratio by reducing mitochondrial ATP production, then activate AMPK, inhibit mTOR, and finally reduce collagen synthesis in fibroblasts [34,35]. Preclinical studies have shown that metformin, whether used alone or in combination with pirfenidone, has antifibrotic effects [36]. Considering that metformin has been proven safe in clinical practice, makes it an attractive candidate for repurposing, pending further controlled clinical evaluation (Table 1).

Table 1. Summary of Glucose Metabolism Drugs.

|

COMPOUND |

TARGET |

MECHANISM OF ACTION |

RESEARCH STATUS |

|---|---|---|---|

|

3PO |

PFKFB3 |

Inhibits PFKFB3, reduces the production of fructose-2,6-bisphosphate, thereby inhibiting the mTOR signaling pathway, decreasing the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β), suppressing the transformation of fibroblasts into myofibroblasts, and reducing collagen deposition |

In the preclinical evaluation stage; a lung-targeted delivery strategy has been proposed to reduce off-target effects [26] |

|

GOSSYPOL |

LDHA |

Competitively binds to the active site of LDHA, inhibits the conversion of pyruvate to lactate, reduces lactate accumulation, and further inhibits the TGF-β1/Smad3 signaling pathway to suppress myofibroblast differentiation |

Preclinical studies have shown antifibrotic efficacy, but it has issues such as hepatotoxicity and reproductive toxicity; safer analogs need to be developed for clinical translation [29] |

|

STF-31 |

GLUT1 |

Inhibits GLUT1-mediated glucose uptake in fibroblasts, reduces glycolytic substrate supply, and inhibits mTOR activation, thereby suppressing collagen synthesis |

In vivo models have demonstrated antifibrotic potential; further optimization is required to improve selectivity and reduce impacts on GLUT1-dependent tissues such as the brain and heart [32] |

|

2-DEOXY-D-GLUCOSE |

Glycolytic pathway (Global inhibition) |

Broadly inhibits the glycolytic process, reduces inflammatory responses, and extracellular matrix deposition |

Clinical application is limited by systemic toxicity, especially significant impacts on tissues highly dependent on glucose; it is expected to be delivered locally via inhalation or nanoparticle carriers, or used in combination therapy rather than monotherapy [34] |

|

METFORMIN |

PFKFB3 (AMPK/mTOR pathway) |

Reduces mitochondrial ATP production, increases the AMP/ATP ratio, activates AMPK, thereby inhibiting mTOR and PFKFB3-mediated glycolysis, and decreases collagen synthesis in fibroblasts |

Clinical safety has been established; preclinical studies have shown antifibrotic effects both alone and in combination with pirfenidone, supporting its potential for further investigation in pulmonary fibrosis [36] |

2.4. Conclusion and Prospect

Glucose metabolic reprogramming is a key driver of fibroblast activation and extracellular matrix deposition in pulmonary fibrosis, with lactate serving as a critical mediator of profibrotic signaling. Targeting glycolysis through enzymes such as PFKFB3 and LDHA, or via metabolic sensors such as AMPK, has shown robust antifibrotic effects in preclinical models (Figure 1). However, clinical translation is hindered by uncertainties regarding the causal role of aerobic glycolysis in fibrosis initiation, off-target toxicity, and efficient delivery to fibrotic lung tissue. Advanced strategies, including inhalable formulations and fibroblast-targeted nanoparticles, may improve tissue specificity and safety. Furthermore, the interplay between glucose metabolism and other pathways, such as lipid and one-carbon metabolism, remains largely unexplored and may uncover novel therapeutic vulnerabilities. Integrating metabolic interventions with approved anti-fibrotics—such as combining AMPK activators with pirfenidone or nintedanib—could enhance efficacy through synergistic effects. Future studies should emphasize longitudinal in vivo metabolic tracing, single-cell metabolic profiling, and biomarker-driven patient selection to optimize therapy. By addressing mechanistic gaps, improving delivery, and combining metabolic modulation with existing treatments, targeting glucose metabolism holds promise as a precision strategy for clinically translatable antifibrotic interventions.

Figure 1. Glucose metabolic reprogramming in lung fibrosis. Fibroblasts in fibrotic lungs exhibit enhanced glycolytic activity, leading to increased lactate production. Upregulation of key glycolytic enzymes, including hexokinase 2 (HK2), 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-bisphosphatase 3 (PFKFB3), and lactate dehydrogenase A (LDHA), supports fibroblast activation and extracellular matrix (ECM) deposition. Representative glycolytic inhibitors investigated in preclinical models are indicated.

3. Lipid Metabolism in Pulmonary Fibrosis

3.1. Pathological Basis of Abnormal Lipid Metabolism

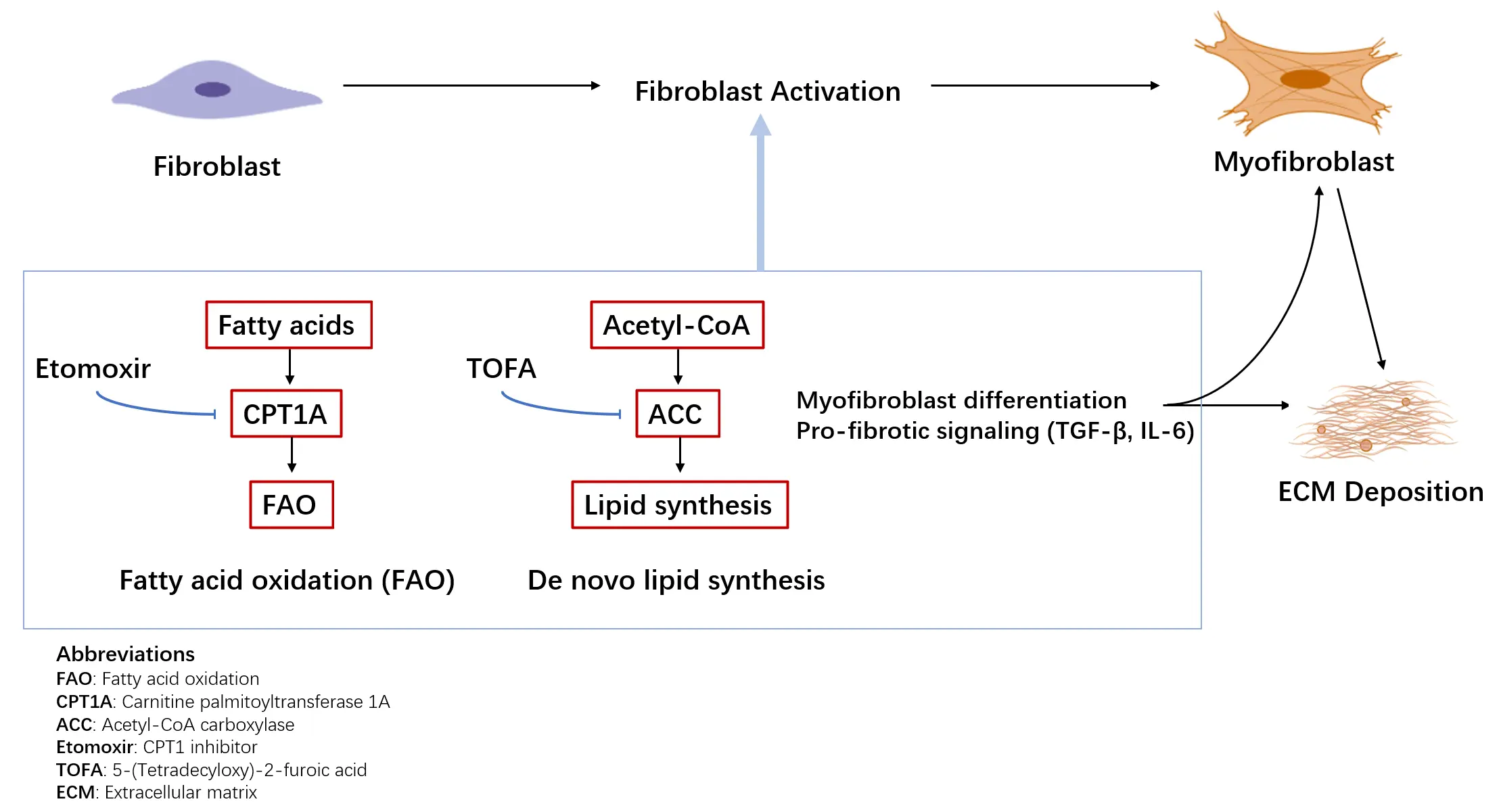

Pulmonary fibrosis is increasingly recognized as a disorder involving not only glucose metabolic reprogramming but also profound alterations in lipid metabolism. Under physiological conditions, AEC2 cells rely on fatty acid oxidation (FAO) and cholesterol homeostasis to maintain surfactant production and cellular integrity. In IPF patients and experimental models, AEC2 cells exhibit enhanced de novo lipogenesis (DNL), reduced FAO [37], and disrupted cholesterol metabolism, resulting in lipid accumulation, mitochondrial dysfunction, and heightened cellular stress [1].

Single-cell transcriptomic analyses have shown significant downregulation of FAO-related genes and upregulation of fatty acid synthesis genes in AEC2 cells of IPF lungs [38], indicating a metabolic shift from oxidation to synthesis [3]. Reanalysis of single-cell RNA-seq databases further unraveled novel molecular mechanisms underlying lipid metabolic dysregulation in IPF, highlighting cell-type-specific lipid metabolic signatures that contribute to epithelial dysfunction and fibroblast activation [39]. In addition to key enzymes involved in lipid synthesis and fatty acid oxidation, such as fatty acid synthase (FASN) and carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1A (CPT1A), downregulation of HMGCS2 [40] in AEC2 cells has also been identified as a key mediator of lipid metabolic alteration, which promotes pulmonary fibrosis by activating fibroblasts [41]. Moreover, dysregulation of fatty acid profiles correlates with lung function decline in IPF patients, emphasizing the clinical relevance of lipid metabolic abnormalities in disease progression [42]. This reprogramming impairs AEC2 regenerative capacity, increases endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress and reactive oxygen species (ROS) accumulation, and promotes epithelial apoptosis [43], collectively hindering tissue repair [44,45].

In interstitial compartments, activated fibroblasts also display abnormal lipid metabolism, including enhanced fatty acid synthesis that supplies energy and lipid precursors for collagen production [46,47]. Accumulated lipid droplets and cholesterol derivatives can further act as signaling molecules, activating the TGF-β pathway and exacerbating fibrosis [1].

3.2. Key Molecular Pathways and Mechanisms of Action

De novo lipogenesis (DNL): fatty acid synthase (FASN) and stearoyl-CoA desaturase 1 (SCD1) are upregulated in fibrotic tissues. Excessive fatty acid synthesis leads to ER stress, apoptosis, and impaired epithelial repair, while saturated fatty acids activate the TLR4/NF-κB pathway to amplify inflammation [5].

Fatty acid oxidation (FAO): CPT1, the rate-limiting enzyme of FAO, is downregulated in AEC2 cells of IPF patients [3]. Reduced FAO results in energy deficiency and lipid droplet accumulation, impairing alveolar epithelial regeneration. Pharmacologic FAO activation can restore AEC2 function and promote repair [48].

Cholesterol metabolism: Cholesterol and its derivatives modulate lipid synthesis and inflammatory signaling through liver X receptor (LXR) and sterol regulatory element-binding protein (SREBP) pathways [44,49]. Accumulation of cholesterol and oxysterols is linked to AEC2 injury, and LXR agonists may improve lipid homeostasis, although they could also exacerbate inflammation [50].

Cross-cell metabolic crosstalk: Altered lipid metabolism in immune cells, particularly macrophages, promotes a profibrotic phenotype through TGF-β and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) secretion [47]. Fibroblasts and AEC2 may interact via free fatty acids or lipid-derived signals, forming a metabolic network that sustains fibrosis.

3.3. Representative Targets and Drug Research

3.3.1. FASN Inhibitors

FASN is an enzyme that plays a key role in the process of fatty acid synthesis and is highly expressed in IPF fibroblasts [51]. In the bleomycin mouse model, studies have shown that FASN inhibition can restore fibroblasts to a quiescent state and reduce collagen deposition [52]. Although current clinical evaluations primarily focus on oncology, FASN inhibitors have potential for treating pulmonary fibrosis. These inhibitors, such as TVB-2640, have demonstrated manageable safety profiles in clinical trials, with mild gastrointestinal effects being the most common. When combined with targeted fibroblast delivery methods, they can limit systemic toxicity, further supporting their therapeutic repurposing for lung fibrosis.

3.3.2. PPARγ Agonist: Rosiglitazone

PPARγ can regulate the formation of lipid droplets and also inhibit the transdifferentiation of fibroblasts into myofibroblasts, which has been mentioned in relevant studies. In IPF, the expression of PPARγ has decreased, and this phenomenon of reduced expression has caused functional disorders in adipocytes. Rosiglitazone can activate PPARγ. Once PPARγ is activated, it can promote the formation of lipid droplets and also restrict the differentiation of myofibroblasts, which is elaborated in the study. While systemic side effects remain a concern, lung-targeted delivery could enhance therapeutic specificity.

3.3.3. Sphingosine-1-Phosphate (S1P) Receptor Antagonists: JTE-013, TY-52156

The S1P signal promotes the production of ECM by activating PI3K/Akt through sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 2 (S1P2R) and sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 3 (S1P3R), which is mentioned in relevant research literature [53,54]. In preclinical models, antagonists JTE-013 and TY-52156 can inhibit downstream signal transduction. It leads to a decrease in the expression of collagen and fibronectin. For future precision medicine strategies, patients with elevated S1P levels can be stratified, and then targeted treatments can be carried out for these patients [55].

3.3.4. PCSK9 Inhibitor: Evolocumab

Proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (Pcsk9)-mediated LDL receptor degradation can cause cholesterol accumulation and also trigger Wnt/β-catenin-driven epithelial-mesenchymal transition, which has been studied in reference. Evolocumab can restore low-density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR) function and reduce cholesterol deposition in the body. It can also suppress the Wnt signal [56]. Although Evolocumab has been clinically approved for the treatment of hyperlipidemia, its therapeutic effect on pulmonary fibrosis still needs to be verified.

3.3.5. ACSL4 Inhibitor: Liproxstatin-1

Acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 4 (ACSL4) can promote lipid peroxidation in AEC2 cells and cause ferroptosis in AEC2 cells, which leads to epithelial damage [57]. Liproxstatin-1 can inhibit ACSL4, reduce the amount of lipid peroxides, and protect the vitality of AEC2 cells, targeting ferroptosis [58,59]. It may also provide new treatment options for specific subtypes of pulmonary fibrosis [60].

3.3.6. Cholesterol Metabolism Modulators

LXR agonists and SREBP inhibitors have been explored for restoring cholesterol homeostasis, as reported in references [61]. However, these agents exert dual effects on lipid regulation and inflammation, and clinical studies have observed a risk of exacerbated inflammatory responses. To mitigate these effects, strategies such as low-dose administration, combination therapy, or targeted lung delivery are being investigated. Prior to clinical translation, detailed studies on cell-type-specific effects and safety profiles are essential to ensure efficacy while minimizing systemic inflammatory risks [62] (Table 2).

Table 2. Summary of Lipid Metabolism Drugs.

|

COMPOUND |

TARGET |

MECHANISM OF ACTION |

RESEARCH STATUS |

|---|---|---|---|

|

FASN INHIBITORS |

FASN |

Inhibits fatty acid synthase (FASN), restores fibroblasts to a quiescent state, reduces collagen deposition, and simultaneously alleviates endoplasmic reticulum stress and epithelial cell apoptosis |

Clinical evaluations are mainly focused on the oncology field; it is expected to be repurposed for pulmonary fibrosis treatment, requiring combination with fibroblast-targeted delivery to reduce systemic toxicity [63] |

|

ROSIGLITAZONE |

PPARγ |

Activates PPARγ, regulates lipid droplet formation, inhibits the transformation of fibroblasts into myofibroblasts, and improves lipofibroblast function |

There is a risk of systemic side effects; lung-targeted delivery can enhance therapeutic specificity; further optimization of delivery methods is needed for clinical translation |

|

JTE-013, TY-52156 |

S1P2R, S1P3R |

Inhibit the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway mediated by S1P receptors, reducing the expression of collagen and fibronectin |

Preclinical models have shown effectiveness; in the future, stratified targeted therapy can be performed for patients with elevated S1P levels through precision medicine strategies [53,54] |

|

EVOLOCUMAB |

PCSK9 |

Inhibits PCSK9-mediated degradation of LDL receptors, restores LDLR function, reduces cholesterol deposition, and inhibits Wnt/β-catenin-driven epithelial-mesenchymal transition |

Already approved for the treatment of hyperlipidemia; its antifibrotic efficacy in pulmonary fibrosis still needs verification [56] |

|

LIPROXSTATIN-1 |

ACSL4 |

Inhibits ACSL4, reduces lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis, protects the viability of type II alveolar epithelial cells (AEC2), and alleviates epithelial damage |

Provides a new therapeutic direction for specific subtypes of pulmonary fibrosis; currently in the preclinical research stage [58,59] |

3.4. Conclusion and Perspective

Lipid metabolic reprogramming in pulmonary fibrosis is characterized by enhanced fatty acid synthesis, reduced fatty acid oxidation (FAO), and disrupted cholesterol homeostasis(Figure 2). In AEC2 cells, these changes impair epithelial repair, whereas in fibroblasts, altered lipid flux fuels extracellular matrix (ECM) production. Preclinical studies targeting lipid metabolism—including FASN inhibitors, FAO activators, PPARγ agonists, and ACSL4 inhibitors—demonstrate promising antifibrotic effects. However, clinical translation is limited by systemic toxicity, inefficient lung-targeted delivery, and insufficient patient stratification. Key mechanistic questions remain unresolved, such as the temporal sequence of lipid abnormalities and their causal role in fibrosis progression. Addressing these gaps will require longitudinal studies and dynamic metabolomic profiling. Furthermore, crosstalk between lipid metabolism and pathways such as inflammation, autophagy, and ferroptosis is incompletely understood, yet may reveal synergistic targets for combination therapies [63]. Advances in pulmonary-targeted formulations, single-cell–guided delivery, and precision medicine approaches could enhance therapeutic specificity and safety [64]. Ultimately, robust evaluation of safety, pharmacodynamics, and biomarker-driven patient selection will be essential. By integrating mechanistic insights with innovative delivery and combinatorial strategies, lipid-targeted interventions hold potential as a precision therapy complementing glucose- and amino acid–focused approaches in pulmonary fibrosis. Recent advances in fatty acid metabolic reprogramming in pulmonary fibrosis have further highlighted novel targets and regulatory networks, providing additional support for lipid-focused therapeutic strategies and emphasizing the need for further translational research [65].

Figure 2. Lipid metabolic reprogramming in lung fibrosis. Fibroblasts undergo lipid metabolic reprogramming characterized by altered fatty acid oxidation (FAO) and de novo lipid synthesis. Enhanced FAO, mediated by carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1A (CPT1A), and increased lipid synthesis contribute to metabolic support of myofibroblast differentiation and profibrotic signaling. Representative metabolic enzymes and inhibitors investigated in preclinical models are indicated.

4. Amino Acid Metabolism in Pulmonary Fibrosis

4.1. Pathological Basis of Abnormal Amino Acid Metabolism

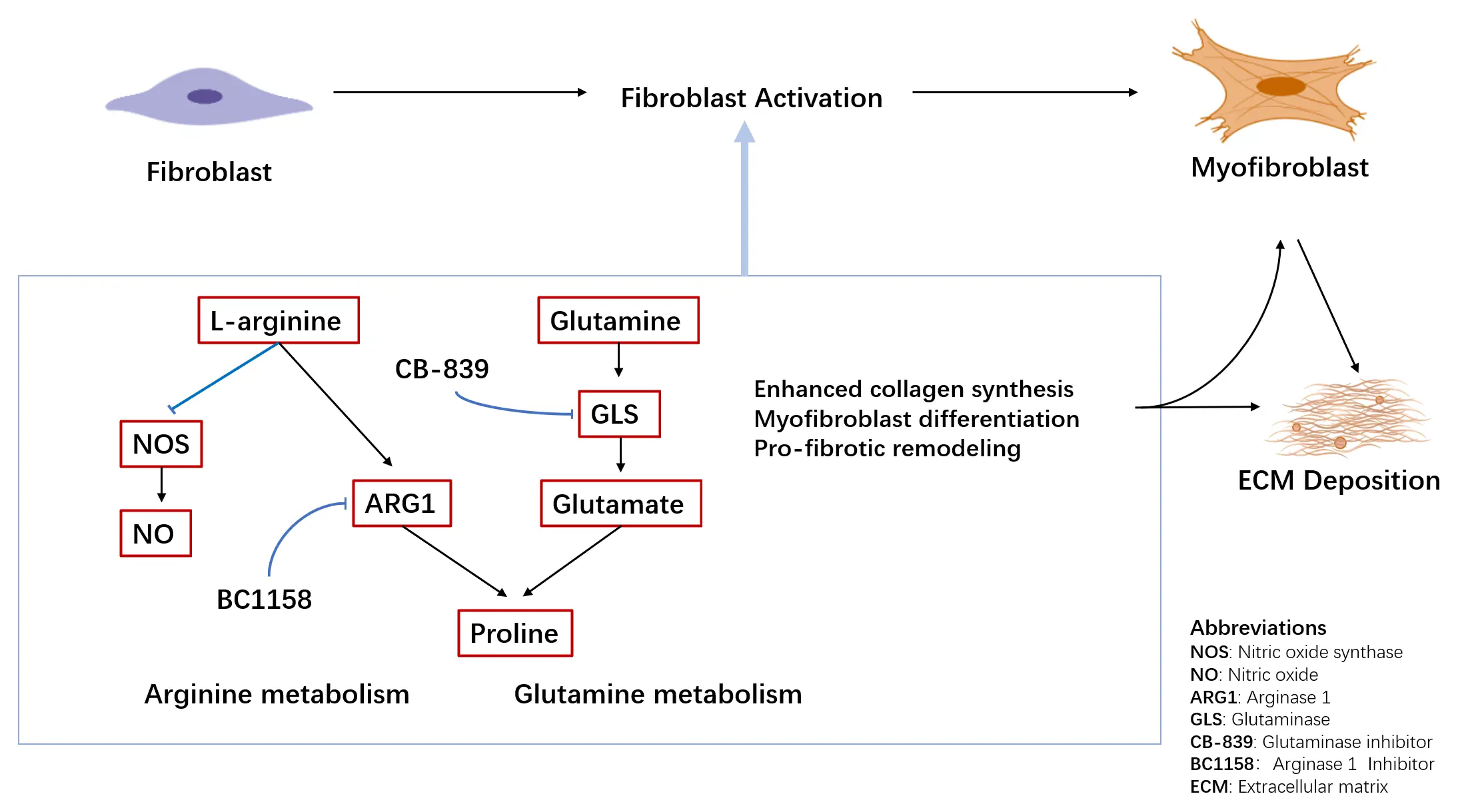

Amino acids are not only fundamental components in protein synthesis, but also key regulatory factors in energy metabolism, antioxidant defense, and signaling pathways. In the case of pulmonary fibrosis, amino acid metabolic reprogramming is increasingly regarded as a key driving factor for the continuous development of the disease [66]. Among them, Glutamine cleavage, arginine metabolism, and the serine/glycine pathway are the main aspects of research. Metabolomics analysis of lung tissue and serum from IPF patients revealed that elevated levels of glutamine, arginine, and proline were related to the severity of the disease [67]. The activation of fibroblasts relies on glutamine and arginine, as they are the sources of carbon and nitrogen for the synthesis of collagen and ECM. Arginine metabolites promote the differentiation of myofibroblasts. Make the fibrotic reaction more severe.

4.2. Key Metabolic Pathways and Mechanisms of Action

4.2.1. Glutamine Metabolism

Glutamine is the most abundant amino acid in lung tissue. It enters cells through the transport of solute carrier family 1 member 5 (SLC1A5), providing necessary substrates for mitochondrial metabolic processes and antioxidant defense mechanisms. The expression of SLC1A5 in IPF fibroblasts and AEC2 cells is upregulated. This upregulation state has a certain correlation with the production of collagen. Glutamine is converted into glutamic acid through Glutaminase 1 (GLS1), generating α-ketoglutaric acid. α-ketoglutaric acid activates mTOR, and the activated mTOR can promote collagen synthesis and also support the generation of mitochondrial NADPH, thereby enhancing the antioxidant capacity of cells. Notably, a two-sample Mendelian randomization study confirmed a causal relationship between circulating glutamine levels and IPF susceptibility, further supporting the pathogenic role of glutamine metabolic reprogramming in disease initiation [68]. GLS1 is overexpressed in fibrotic lungs [69,70]. This overexpression can promote the production of ECM by providing proline precursors and maintaining redox homeostasis.

4.2.2. Arginine Metabolism

The metabolism of arginine mainly occurs through two pathways. The first one is the nitric oxide synthase pathway, in which arginine is converted into NO and citrulline. NO can act as a vasodilator, inhibiting the activation of fibroblasts and regulating the polarization of macrophages towards an antifibrotic phenotype. In the disease of pulmonary fibrosis, oxidative stress can reduce the activity of NOS and also decrease the production of NO, thereby weakening its protective effect [71]. However, if exogenous L-arginine is used or NOS is activated, the NO-mediated antifibrotic signal can be restored. This point has been mentioned in the relevant literature [72]. The second one is the arginase pathway. In this pathway, arginase converts arginine into ornithine, which is then processed by ornithine decarboxylase into polyamines or by pyrroline-5-carboxylate synthase (P5CS) into proline. These substances can provide substrates for collagen synthesis, which is described in references [73]. In cases of fibrosis, the activity of arginase increases, which diverts arginine from the NOS pathway, promoting the differentiation of myofibroblasts and the deposition of ECM.

4.2.3. Serine/Glycine Metabolism

Serine and glycine are beneficial for the synthesis of glutathione, which can maintain antioxidant balance. Serine metabolism can provide a carbon unit for the synthesis of nucleotides and phospholipids, while glycine is integrated into collagen tripeptides [74]. In IPF, the level of glutathione is decreased, while the expression of enzymes such as phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase is upregulated. This indicates that fibroblasts will enhance the metabolism of serine and glycine to meet the demands of extracellular matrix synthesis and alleviate oxidative stress.

4.2.4. Proline Metabolism

Proline accounts for approximately one-third of the amino acids in collagen. It is a rate-limiting factor in the process of collagen synthesis. In cases of fibrosis, fibroblasts rely on the arginine-ornithine-proline pathway to produce proline. In the lungs of IPF, the expressions of ornithine transaminase and pyrrolin-5-carboxylic acid reductase 1 showed an increase. The activity of pyrroliin-5-carboxylate reductase 1 is related to the expression of type I collagen. If pyrroliin-5-carboxylate reductase 1 is inhibited, the availability of proline can be reduced, and the synthesis of collagen will also decrease [75]. Glutamine can also promote proline production. It will establish the glutamine-proline axis, which supports the deposition of extracellular matrix [76,77].

4.3. Representative Targets and Drug Research

4.3.1. GLS1 Inhibitors: CB-839

CB-839 can inhibit GLS1. This inhibitory effect will reduce the production of glutamic acid and α-KG, thereby limiting the activation of mTOR and the synthesis of proline, and inhibiting collagen deposition [78]. Preclinical studies have shown that it has the potential for anti-fibrosis. Preliminary safety data have also been obtained in tumor clinical trials. For clinical application, the dosage should be carefully optimized due to potential adverse effects on immune function. Notably, pyruvate metabolism has been shown to dictate fibroblast sensitivity to GLS1 inhibition during fibrogenesis, suggesting that combining GLS1 inhibitors with modulators of pyruvate metabolism may enhance therapeutic efficacy by overcoming metabolic compensation [79].

4.3.2. Glutamine Transport Inhibitor: V-9302

V-9302 blocks SLC1A5-mediated glutamine uptake, inhibiting fibroblast mTOR activation and ECM synthesis while improving AEC2 function in bleomycin models [80]. Its selective action on fibrotic cells suggests high safety and translational potential [81].

4.3.3. NOS Agonist: L-Arginine

Exogenous L-arginine restores NO production in oxidative stress–impaired lungs, improving pulmonary perfusion, inhibiting fibroblast proliferation, and modulating macrophage polarization [82,83]. Preclinical data are promising, but clinical evaluation in IPF is lacking.

4.3.4. Arginase 1 (ARG1) Inhibitor: BC1158

BC1158 competitively inhibits ARG1, reducing ornithine and proline production, collagen synthesis, and fibroblast-to-myofibroblast transdifferentiation via TGF-β/Smad pathway suppression [76,84]. In vitro studies demonstrate efficacy, but in vivo and clinical studies are pending.

4.3.5. SHMT2 Inhibitor: SHIN1

SHIN1 inhibits one-carbon metabolism, reducing NADPH availability for prolyl hydroxylase and limiting hydroxyproline formation, while decreasing glycine supply for collagen tripeptides [79,81]. In preclinical fibrosis models, SHIN1 reduces lung collagen deposition, though effects on cellular antioxidant capacity warrant caution [82](Table 3).

Table 3. Summary of Amino Acid Metabolism Drugs.

|

COMPOUND |

TARGET |

MECHANISM OF ACTION |

RESEARCH STATUS |

|---|---|---|---|

|

CB-839 |

GLS1 |

Inhibits glutaminase GLS1, reduces the production of glutamate and α-ketoglutarate (α-KG), thereby inhibiting mTOR activation and proline synthesis, and suppressing collagen deposition |

Preclinical studies support its antifibrotic potential; clinical trials in the oncology field have provided preliminary safety data; dosage optimization is needed to avoid impacts on immune function [78,79] |

|

V-9302 |

SLC1A5 |

Blocks SLC1A5-mediated glutamine uptake, inhibits mTOR activation and extracellular matrix synthesis in fibroblasts, and improves AEC2 function |

Exerts selective effects on fibrotic cells with high safety and translational potential; in the preclinical research stage [80,81] |

|

L-ARGININE |

NOS |

Serves as a substrate for NOS, restores NO production in lungs impaired by oxidative stress, improves pulmonary perfusion, inhibits fibroblast proliferation, and regulates macrophage polarization |

Preclinical data show promising prospects, but clinical evaluation in IPF patients is lacking [82] |

|

BC1158 |

ARG1 |

Competitively inhibits ARG1, reduces the production of ornithine and proline, and decreases collagen synthesis and the transformation of fibroblasts into myofibroblasts by inhibiting the TGF-β/Smad pathway |

In vitro studies have shown effectiveness; in vivo and clinical studies have not been carried out [76,84] |

|

SHIN1 |

SHMT2 |

Inhibits serine SHMT2, reduces the production of one-carbon metabolites, decreases NADPH availability and glycine supply, thereby inhibiting hydroxyproline formation and collagen tripeptide synthesis |

Can reduce pulmonary collagen deposition in preclinical fibrosis models; its impact on cellular antioxidant capacity needs careful evaluation; currently in the preclinical research stage [82] |

4.4. Conclusion and Prospect

Amino acid metabolic reprogramming is a central driver of pulmonary fibrosis, with glutamine, arginine, and serine/glycine pathways supplying fibroblasts with energy, redox equivalents, and essential substrates for collagen synthesis. Among these pathways, glutamine catabolism and its downstream products—such as α-ketoglutarate and proline—play a particularly prominent role in sustaining fibroblast activation and extracellular matrix (ECM) production [85] (Figure 3). GLS1 inhibitors therefore, represent the most advanced candidates for clinical translation, while arginase blockers and serine/glycine pathway inhibitors continue to show encouraging preclinical efficacy. However, the temporal dynamics and cell-type-specific contributions of these pathways remain incompletely defined, underscoring the need for integrated single-cell omics and metabolic profiling to map metabolic dependencies across fibroblasts, epithelial cells, and immune populations.

Figure 3. Amino acid metabolism in lung fibrosis. Dysregulated amino acid metabolism contributes to fibrotic lung remodeling through altered arginine and glutamine utilization. Arginine metabolism is partitioned between nitric oxide synthase (NOS)–mediated nitric oxide (NO) production and Arginase 1 (ARG1)–dependent pathways generating polyamines and proline. In parallel, enhanced glutamine metabolism via glutaminase (GLS) provides substrates for collagen synthesis and supports myofibroblast differentiation. Representative metabolic enzymes and inhibitors investigated in preclinical models are indicated.

Several challenges hinder therapeutic development. Systemic inhibition of amino acid metabolism risks disrupting immune cell function and normal tissue homeostasis, necessitating strategies such as pulmonary-targeted delivery, precision dosing, or tissue-selective transport inhibitors to improve safety and specificity. Additionally, compensatory activation of parallel metabolic pathways may limit the efficacy of single-target approaches; therefore, rational combination therapies—such as simultaneous inhibition of glutamine uptake and proline synthesis—may yield synergistic antifibrotic effects.

Beyond metabolism alone, the interactions between amino acid pathways and broader cellular networks—including mTOR signaling, redox regulation, epigenetic remodeling, and ferroptosis—remain underexplored but may reveal new therapeutic vulnerabilities [86]. Clinical translation will also require robust pharmacodynamic markers and biomarker-driven patient stratification to identify individuals most likely to benefit from amino acid–targeted interventions [87]. At the same time, Lung-targeted delivery strategies, including inhalation-based administration or nanoparticle-mediated delivery, may enhance drug accumulation in fibrotic lung tissue while minimizing systemic exposure.

By addressing these mechanistic and translational challenges, amino acid–focused therapies have the potential to complement glucose- and lipid-directed strategies, collectively expanding the landscape of precision metabolic interventions for pulmonary fibrosis.

5. Future Perspectives

Despite growing evidence that metabolic reprogramming contributes to pulmonary fibrosis, several conceptual and translational challenges remain. A major unresolved issue is the pronounced spatiotemporal heterogeneity of metabolic alterations across lung cell types and disease stages [88]. Most current studies rely on bulk tissue analyses or static in vitro systems, which are insufficient to distinguish initiating metabolic drivers from secondary adaptive responses [89]. Defining cell-specific and stage-dependent metabolic vulnerabilities in vivo will be essential for prioritizing therapeutic targets with true disease-modifying potential.

Another critical barrier to clinical translation is the lack of lung- and cell-selective targeting strategies for metabolic interventions [90,91]. Because core metabolic pathways are indispensable for systemic homeostasis, pharmacological inhibition often results in off-target toxicity in energy-demanding tissues [92]. Advances in pulmonary-targeted delivery approaches may allow more precise modulation of pathogenic metabolism while minimizing systemic exposure, thereby expanding the therapeutic window of metabolic drugs that are currently limited by safety concerns.

Metabolic plasticity further complicates therapeutic development. Extensive redundancy and compensatory flux within metabolic networks may compromise undermine the durability of single-pathway inhibition [89]. This highlights the need for rational combination strategies, either targeting multiple interconnected metabolic nodes or integrating metabolic modulation with established antifibrotic therapies [93]. However, the optimal timing, sequence, and patient populations for such combinations remain poorly defined and warrant systematic investigation.

Beyond energy metabolism, emerging evidence suggests that metabolic pathways intersect with broader regulatory networks, including immune modulation, epithelial plasticity, redox balance, and epigenetic control [92]. Metabolites such as lactate, lipids, and tricarboxylic acid cycle intermediates may act as signaling molecules that influence gene regulation and cell fate decisions, positioning metabolism as an upstream coordinator of fibrogenic programs rather than a passive consequence of disease [94,95].

Finally, progress toward clinical translation will depend on the development of robust metabolic biomarkers to support patient stratification, target engagement, and therapeutic monitoring [96]. Integrating metabolomic profiling with genetic approaches, imaging modalities, and clinical phenotyping may enable the identification of metabolically defined subgroups of pulmonary fibrosis [97]. Such stratification could facilitate more precise and durable interventions, moving metabolic targeting closer to personalized antifibrotic therapy.

6. Conclusions

The metabolic reprogramming of glucose, lipids, and amino acids reflects the core pathological biological markers of pulmonary fibrosis and provides a set of therapeutic targets with many mechanism validations [98], such as key regulatory factors like PFKFB3, GLUT1, LDHA, FASN, S1P signaling, GLS1, SLC1A5, and ARG1 [99]. They regulate fibroblast activation, failed epithelial repair, immune cell reprogramming, and ECM accumulation, demonstrating consistent antifibrotic potential in preclinical systems [100,101]. These findings highlight that metabolism is a driving factor and a modifiable determinant of fibrogenesis [102]. However, current research has some limitations. On the one hand, there is insufficient understanding of cell-specific and stage-specific metabolic dependencies. On the other hand, there is a lack of lung or cell-targeted delivery technologies. Moreover, compensatory metabolic mechanisms have reduced the persistence of single-pathway interventions [103]. In addition, there are relatively few metabolic biomarkers used for clinical translation. To address these limitations, three coordinated strategies are needed. The first is to conduct high-resolution metabolic analysis, which includes single-cell and spatial metabolomics. The second is to develop lung-targeted drug delivery systems that can enhance specificity and reduce systemic toxicity [104]. The third is to carry out biomarker-guided early clinical trials. This is to establish safety, metabolic target participation, and personalized treatment methods. With the continuous integration of metabolomics, systems biology, biomaterials engineering, and pharmacology, metabolic reprogramming is preparing to advance from the understanding of mechanisms to therapeutic applications. Targeting metabolic susceptibility, whether alone or in combination with existing antifibrotic drugs, it may provide a revolutionary approach for the precise and effective treatment of pulmonary fibrosis. A recent review further summarizes the core mechanisms of metabolic reprogramming in IPF, integrating glucose, lipid, and amino acid metabolic abnormalities and supporting the translational potential of targeting metabolic vulnerabilities [105].

Targeting metabolic pathways represents a promising therapeutic avenue in lung fibrosis, particularly during early and potentially reversible stages of disease progression. However, effective clinical translation will require careful consideration of disease heterogeneity, lung-specific drug delivery strategies, and safety in vulnerable patient populations. Future studies integrating metabolic profiling with cell-specific and stage-specific targeting approaches may enable more precise and durable antifibrotic therapies.

Statement of the Use of Generative AI and AI-Assisted Technologies in the Writing Process

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT (version 4.0) solely for grammar checking. After using this tool, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and assume full responsibility for the content of the published article.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all researchers whose work contributed to this review.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.W.; Methodology, Y.W.; Software, Y.W.; Validation, Y.Z. (Yanlin Zhou), and Y.Z. (Yilin Zhang), and J.L.; Formal Analysis, Y.Z. (Yanlin Zhou); Investigation, Y.Z. (Yanlin Zhou); Resources, Y.W. and Y.Z. (Yanlin Zhou); Data Curation, Y.Z. (Yilin Zhang) and J.L.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, Y.W.; Writing—Review & Editing, Y.W.; Visualization, Y.W.; Supervision, G.Y. and L.W.; Project Administration, G.Y. and L.W.; Funding Acquisition, G.Y. and L.W.

Ethics Statement

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were generated or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China(Grant Number 32570921 to L.W.), State Innovation Base for Pulmonary Fibrosis (111 Project) , Key R&D Program of Henan province, China (231111310400 to G.Y.), Zhongyuan scholar, Henan, China (244000510009 to G.Y.), and Henan Project of Science and Technology, China (GZS2023008, 242102311167, 252102520084).

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper

References

- Ptasinski VA, Stegmayr J, Belvisi MG, Wagner DE, Murray LA. Targeting Alveolar Repair in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2021, 65, 347–365. DOI:10.1165/rcmb.2020-0476TR [Google Scholar]

- Dai T, Liang Y, Li X, Zhao J, Li G, Li Q, et al. Targeting Alveolar Epithelial Cell Metabolism in Pulmonary Fibrosis: Pioneering an Emerging Therapeutic Strategy. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2025, 13, 1608750. DOI:10.3389/fcell.2025.1608750 [Google Scholar]

- Qian W, Xia S, Yang X, Yu J, Guo B, Lin Z, et al. Complex Involvement of the Extracellular Matrix, Immune Effect, and Lipid Metabolism in the Development of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2022, 8, 800747. DOI:10.3389/fmolb.2021.800747 [Google Scholar]

- Hamanaka RB, O’Leary EM, Witt LJ, Tian Y, Gökalp GA, Meliton AY, et al. Glutamine Metabolism Is Required for Collagen Protein Synthesis in Lung Fibroblasts. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2019, 61, 597–606. DOI:10.1165/rcmb.2019-0008OC [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Qu S, Wang L, Wang C, Yu Q, Zhang Z, et al. Tianlongkechuanling Inhibits Pulmonary Fibrosis Through Down-Regulation of Arginase-Ornithine Pathway. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 661129. DOI:10.3389/fphar.2021.661129 [Google Scholar]

- Bernard K, Logsdon NJ, Benavides GA, Sanders Y, Zhang J, Darley-Usmar VM, et al. Glutaminolysis is required for transforming growth factor-β1-induced myofibroblast differentiation and activation. J. Biol. Chem. 2018, 293, 1218–1228. DOI:10.1074/jbc.RA117.000444 [Google Scholar]

- Xie N, Tan Z, Banerjee S, Cui H, Ge J, Liu RM, et al. Glycolytic Reprogramming in Myofibroblast Differentiation and Lung Fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2015, 192, 1462–1474. DOI:10.1164/rccm.201504-0780OC [Google Scholar]

- Shin H, Park S, Hong J, Baek AR, Lee J, Kim DJ, et al. Overexpression of fatty acid synthase attenuates bleomycin induced lung fibrosis by restoring mitochondrial dysfunction in mice. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 9044. DOI:10.1038/s41598-023-36009-3 [Google Scholar]

- Hinz B, Phan SH, Thannickal VJ, Galli A, Bochaton-Piallat ML, Gabbiani G. The myofibroblast: One function, multiple origins. Am. J. Pathol. 2007, 170, 1807–1816. DOI:10.2353/ajpath.2007.070112 [Google Scholar]

- Sun Z, Ji Z, He W, Duan R, Qu J, Yu G. Lactate Accumulation Induced by Akt2-PDK1 Signaling Promotes Pulmonary Fibrosis. FASEB J. 2024, 38, e23426. DOI:10.1096/FJ.202302063RR [Google Scholar]

- Mu X, Shi W, Xu Y, Xu C, Zhao T, Geng B, et al. Tumor-derived lactate induces M2 macrophage polarization via the activation of the ERK/STAT3 signaling pathway in breast cancer. Cell Cycle 2018, 17, 428–438. DOI:10.1080/15384101.2018.1444305 [Google Scholar]

- Tang CJ, Xu J, Ye HY, Wang XB. Metformin prevents PFKFB3-related aerobic glycolysis from enhancing collagen synthesis in lung fibroblasts by regulating AMPK/mTOR pathway. Exp. Ther. Med. 2021, 21, 581. DOI:10.3892/etm.2021.10013 [Google Scholar]

- Yan P, Liu J, Li Z, Wang J, Zhu Z, Wang L, et al. Glycolysis Reprogramming in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis: Unveiling the Mystery of Lactate in the Lung. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 25, 315. DOI:10.3390/ijms25010315 [Google Scholar]

- Tannahill GM, Curtis AM, Adamik J, Palsson-McDermott EM, McGettrick AF, Goel G, et al. Succinate is an inflammatory signal that induces IL-1β through HIF-1α. Nature 2013, 496, 238–242. DOI:10.1038/nature11986 [Google Scholar]

- Murray LA, Chen Q, Kramer MS, Hesson DP, Argentieri RL, Peng X, et al. TGF-beta driven lung fibrosis is macrophage dependent and blocked by Serum amyloid P. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2011, 43, 154–162. DOI:10.1016/j.biocel.2010.10.013 [Google Scholar]

- Jin T, Gao H, Wang Y, Ning Z, Bing D, Wang Y, et al. SRSF7 promotes pulmonary fibrosis through regulating PKM alternative splicing in lung fibroblasts. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2025, 15, 3041–3058. DOI:10.1016/j.apsb.2025.04.017 [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin J, Choi H, Hsieh MH, Neugent ML, Ahn JM, Hayenga HN, et al. Targeting Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-1α/Pyruvate Dehydrogenase Kinase 1 Axis by Dichloroacetate Suppresses Bleomycin-induced Pulmonary Fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2018, 58, 216–231. DOI:10.1165/rcmb.2016-0186OC [Google Scholar]

- Yang L, Gilbertsen A, Xia H, Benyumov A, Smith K, Herrera J, et al. Hypoxia enhances IPF mesenchymal progenitor cell fibrogenicity via the lactate/GPR81/HIF1α pathway. JCI Insight 2023, 8, e163820. DOI:10.1172/jci.insight.163820 [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Yang X, Ma J, Xie X, Sun Y, Chang X, et al. PI3K/AKT pathway promotes keloid fibroblasts proliferation by enhancing glycolysis under hypoxia. Wound Repair Regen. 2023, 31, 139–155. DOI:10.1111/wrr.13067 [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Hu K, Cai X, Yang B, He Q, Wang J, et al. Targeting PI3K/AKT signaling for treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2022, 12, 18–32. DOI:10.1016/j.apsb.2021.07.023 [Google Scholar]

- Harding HP, Zhang Y, Zeng H, Novoa I, Lu PD, Calfon M, et al. An integrated stress response regulates amino acid metabolism and resistance to oxidative stress. Mol. Cell 2003, 11, 619–633. DOI:10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00105-9 [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Wang X, Du C, Wang Z, Wang J, Zhou N, et al. Glycolysis and beyond in glucose metabolism: Exploring pulmonary fibrosis at the metabolic crossroads. Front. Endocrinol. 2024, 15, 1379521. DOI:10.3389/fendo.2024.1379521 [Google Scholar]

- Yan X, Liu C. The ATF4-glutamine axis: A central node in cancer metabolism, stress adaptation, and therapeutic targeting. Cell Death Discov. 2025, 11, 390. DOI:10.1038/s41420-025-02683-7 [Google Scholar]

- Henderson J, O’Reilly S. The emerging role of metabolism in fibrosis. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2021, 32, 639–653. DOI:10.1016/j.tem.2021.05.003 [Google Scholar]

- Shin KWD, Atalay MV, Cetin-Atalay R, O’Leary EM, Glass ME, Houpy Szafran JC, et al. mTOR signaling regulates multiple metabolic pathways in human lung fibroblasts after TGF-β and in pulmonary fibrosis. Am. J. Physiol.-Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2025, 328, L215–L228. DOI:10.1152/ajplung.00189.2024 [Google Scholar]

- Hu X, Xu Q, Wan H, Hu Y, Xing S, Yang H, et al. PI3K-Akt-mTOR/PFKFB3 pathway mediated lung fibroblast aerobic glycolysis and collagen synthesis in lipopolysaccharide-induced pulmonary fibrosis. Lab. Investig. 2020, 100, 801–811. DOI:10.1038/s41374-020-0404-9 [Google Scholar]

- Liu C, Zhang Q, Zhou H, Jin L, Liu C, Yang M, et al. GLP-1R activation attenuates the progression of pulmonary fibrosis via disrupting NLRP3 inflammasome/PFKFB3-driven glycolysis interaction and histone lactylation. J. Transl. Med. 2024, 22, 954. DOI:10.1186/s12967-024-05753-z [Google Scholar]

- Kottmann RM, Kulkarni AA, Smolnycki KA, Lyda E, Dahanayake T, Salibi R, et al. Lactic acid is elevated in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and induces myofibroblast differentiation via pH-dependent activation of transforming growth factor-β. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2012, 186, 740–751. DOI:10.1164/rccm.201201-0084OC [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J, Shi W, Wang YL, Chen H, Bringas P, Datto MB, et al. Smad3 deficiency attenuates bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis in mice. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 2002, 282, L585–L593. DOI:10.1152/ajplung.00151.2001 [Google Scholar]

- Andrianifahanana M, Hernandez DM, Yin X, Kang J, Jung M, Wang Y, et al. Profibrotic up-regulation of glucose transporter 1 by TGF-β involves activation of MEK and mammalian target of rapamycin complex 2 pathways. FASEB J. 2016, 30, 3733–3744. DOI:10.1096/fj.201600428R [Google Scholar]

- Judge JL, Nagel DJ, Owens KM, Rackow A, Phipps RP, Sime PJ, et al. Prevention and treatment of bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis with the lactate dehydrogenase inhibitor gossypol. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0197936. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0197936 [Google Scholar]

- Cho SJ, Moon JS, Lee CM, Choi AM, Stout-Delgado HW. Glucose Transporter 1-Dependent Glycolysis Is Increased during Aging-Related Lung Fibrosis, and Phloretin Inhibits Lung Fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2017, 56, 521–531. DOI:10.1165/rcmb.2016-0225OC [Google Scholar]

- Temre MK, Kumar A, Singh SM. An appraisal of the current status of inhibition of glucose transporters as an emerging antineoplastic approach: Promising potential of new pan-GLUT inhibitors. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 1035510. DOI:10.3389/fphar.2022.1035510 [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y, Mu M, RenChen X, Wang W, Zhu Y, Zhong M, et al. 2-Deoxy-D-glucose ameliorates inflammation and fibrosis in a silicosis mouse model by inhibiting hypoxia-inducible factor-1α in alveolar macrophages. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 269, 115767. DOI:10.1016/j.ecoenv.2023.115767 [Google Scholar]

- Li SX, Li C, Pang XR, Zhang J, Yu GC, Yeo AJ, et al. Metformin Attenuates Silica-Induced Pulmonary Fibrosis by Activating Autophagy via the AMPK-mTOR Signaling Pathway. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 719589. DOI:10.3389/fphar.2021.719589 [Google Scholar]

- Rangarajan S, Bone NB, Zmijewska AA, Jiang S, Park DW, Bernard K, et al. Metformin reverses established lung fibrosis in a bleomycin model. Nat. Med. 2018, 24, 1121–1127. DOI:10.1038/s41591-018-0087-6 [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Yuan H, Li W, Yan P, Zhao M, Li Z, et al. ACSS3 regulates the metabolic homeostasis of epithelial cells and alleviates pulmonary fibrosis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2024, 1870, 166960. DOI:10.1016/j.bbadis.2023.166960 [Google Scholar]

- Adams TS, Schupp JC, Poli S, Ayaub EA, Neumark N, Ahangari F, et al. Single-cell RNA-seq reveals ectopic and aberrant lung-resident cell populations in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eaba1983. DOI:10.1126/sciadv.aba1983 [Google Scholar]

- Ji H, Dong H, Lan Y, Bi Y, Gu X, Han Y, et al. Metformin attenuates fibroblast activation during pulmonary fibrosis by targeting S100A4 via AMPK-STAT3 axis. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1089812. DOI:10.3389/fphar.2023.1089812 [Google Scholar]

- Yang J, Pan X, Xu M, Li Y, Liang C, Liu L, et al. Downregulation of HMGCS2 mediated AECIIs lipid metabolic alteration promotes pulmonary fibrosis by activating fibroblasts. Respir. Res. 2024, 25, 176. DOI:10.1186/s12931-024-02816-z [Google Scholar]

- Shi X, Chen Y, Shi M, Gao F, Huang L, Wang W, et al. The novel molecular mechanism of pulmonary fibrosis: Insight into lipid metabolism from reanalysis of single-cell RNA-seq databases. Lipids Health Dis. 2024, 23, 98. DOI:10.1186/s12944-024-02062-8 [Google Scholar]

- Faverio P, Rebora P, Franco G, Amato A, Corti N, Cattaneo K, et al. Alteration of Lipid Metabolism in Patients with IPF and Its Association with Disease Severity and Prognosis: A Case-Control Study. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 5790. DOI:10.3390/ijms26125790 [Google Scholar]

- Korfei M, Ruppert C, Mahavadi P, Henneke I, Markart P, Koch M, et al. Epithelial endoplasmic reticulum stress and apoptosis in sporadic idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2008, 178, 838–846. DOI:10.1164/rccm.200802-313OC [Google Scholar]

- Lawson WE, Cheng DS, Degryse AL, Tanjore H, Polosukhin VV, Xu XC, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress enhances fibrotic remodeling in the lungs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 10562–10567. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1107559108 [Google Scholar]

- Mo C, Li H, Yan M, Xu S, Wu J, Li J, et al. Dopaminylation of endothelial TPI1 suppresses ferroptotic angiocrine signals to promote lung regeneration over fibrosis. Cell Metab. 2024, 36, 1839–1857.e12. DOI:10.1016/j.cmet.2024.07.008 [Google Scholar]

- Scialò F, Pagliaro R, Gelzo M, Matera MG, D’Agnano V, Zamparelli SS, et al. Fatty Acids Dysregulation Correlates with Lung Function in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Lung 2025, 203, 99. DOI:10.1007/s00408-025-00852-0 [Google Scholar]

- Geng J, Liu Y, Dai H, Wang C. Fatty Acid Metabolism and Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Front. Physiol. 2022, 12, 794629. DOI:10.3389/fphys.2021.794629 [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Kuan PJ, Xing C, Cronkhite JT, Torres F, Rosenblatt RL, et al. Genetic defects in surfactant protein A2 are associated with pulmonary fibrosis and lung cancer. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2009, 84, 52–59. DOI:10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.11.010 [Google Scholar]

- Zelcer N, Tontonoz P. Liver X receptors as integrators of metabolic and inflammatory signaling. J. Clin. Investig. 2006, 116, 607–614. DOI:10.1172/JCI27883 [Google Scholar]

- Gowdy KM, Fessler MB. Emerging roles for cholesterol and lipoproteins in lung disease. Pulm. Pharmacol. Ther. 2013, 26, 430–437. DOI:10.1016/j.pupt.2012.06.002 [Google Scholar]

- Jung MY, Kang JH, Hernandez DM, Yin X, Andrianifahanana M, Wang Y, et al. Fatty Acid Synthase Is Required for Profibrotic TGF-β Signaling. FASEB J. 2018, 32, 3803–3815. DOI:10.1096/FJ.201701187R [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, Liang Y, Dai C. Metabolic Regulation of Fibroblast Activation and Proliferation during Organ Fibrosis. Kidney Dis. 2022, 8, 115–125. DOI:10.1159/000522417 [Google Scholar]

- Lian H, Zhang Y, Zhu Z, Wan R, Wang Z, Yang K, et al. Fatty acid synthase inhibition alleviates lung fibrosis via β-catenin signal in fibroblasts. Life Sci. Alliance 2024, 8, e202402805. DOI:10.26508/lsa.202402805 [Google Scholar]

- Park SJ, Im DS. Deficiency of Sphingosine-1-Phosphate Receptor 2 (S1P2) Attenuates Bleomycin-Induced Pulmonary Fibrosis. Biomol. Ther. 2019, 27, 318–326. DOI:10.4062/biomolther.2018.131 [Google Scholar]

- Huang LS, Sudhadevi T, Fu P, Punathil-Kannan PK, Ebenezer DL, Ramchandran R, et al. Sphingosine Kinase 1/S1P Signaling Contributes to Pulmonary Fibrosis by Activating Hippo/YAP Pathway and Mitochondrial Reactive Oxygen Species in Lung Fibroblasts. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2064. DOI:10.3390/ijms21062064 [Google Scholar]

- Qiu H, Liu J, You J, Zhou O, Hao C, Shu Y, et al. Inhibition of sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor 3 ameliorates bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis by suppressing macrophage M2 polarization. Genes Dis. 2024, 12, 101244. DOI:10.1016/j.gendis.2024.101244 [Google Scholar]

- Lin J, Pan Z, Sun J, Wang X, Yin D, Huo C, et al. PCSK9 inhibitor alleviates experimental pulmonary fibrosis-induced pulmonary hypertension via attenuating epithelial-mesenchymal transition by suppressing Wnt/β-catenin signaling in vivo and in vitro. Front. Med. 2024, 11, 1509168. DOI:10.3389/fmed.2024.1509168 [Google Scholar]

- Doll S, Proneth B, Tyurina YY, Panzilius E, Kobayashi S, Ingold I, et al. ACSL4 dictates ferroptosis sensitivity by shaping cellular lipid composition. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2017, 13, 91–98. DOI:10.1038/nchembio.2239 [Google Scholar]

- Yao M, Liu Z, Zhao W, Song S, Huang X, Wang Y. Ferroptosis in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: Mechanisms, impact, and therapeutic opportunities. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1567994. DOI:10.3389/fimmu.2025.1567994 [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Kang R, Kroemer G, Tang D. Broadening horizons: The role of ferroptosis in cancer. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 18, 280–296. DOI:10.1038/s41571-020-00462-0 [Google Scholar]

- Lin M, Lv J, Zhao D, Liu S, Xu J, Wu Y, et al. MRNIP is essential for meiotic progression and spermatogenesis in mice. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2021, 550, 127–133. DOI:10.1016/j.bbrc.2021.02.143 [Google Scholar]

- Bensinger SJ, Tontonoz P. Integration of metabolism and inflammation by lipid-activated nuclear receptors. Nature 2008, 454, 470–477. DOI:10.1038/nature07202 [Google Scholar]

- Koundouros N, Poulogiannis G. Reprogramming of fatty acid metabolism in cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2020, 122, 4–22. DOI:10.1038/s41416-019-0650-z [Google Scholar]

- Mikelez-Alonso I, Magadán S, González-Fernández Á, Borrego F. Natural killer (NK) cell-based immunotherapies and the many faces of NK cell memory: A look into how nanoparticles enhance NK cell activity. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2021, 176, 113860. DOI:10.1016/j.addr.2021.113860 [Google Scholar]

- Shichino S, Ueha S, Hashimoto S, Otsuji M, Abe J, Tsukui T, et al. Transcriptome network analysis identifies protective role of the LXR/SREBP-1c axis in murine pulmonary fibrosis. JCI Insight 2019, 4, e122163. DOI:10.1172/jci.insight.122163 [Google Scholar]

- Bröer S, Bröer A. Amino acid homeostasis and signalling in mammalian cells and organisms. Biochem. J. 2017, 474, 1935–1963. DOI:10.1042/BCJ20160822 [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Zhang Y, Liu Y. Fibroblast activation and heterogeneity in fibrotic disease. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2025, 21, 613–632. DOI:10.1038/s41581-025-00969-8 [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Hou T, Ge F, Jiang H, Liu F, Tian J, et al. Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis Is Associated with Type 1 Diabetes: A Two-Sample Mendelian Randomization Study. J. Gene Med. 2025, 27, e70008. DOI:10.1002/jgm.70008 [Google Scholar]

- Chen M, Meng X, Zhu Y, Wang D, Wang M, Wang Z, et al. Cathepsin K Aggravates Pulmonary Fibrosis Through Promoting Fibroblast Glutamine Metabolism and Collagen Synthesis. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12, e13017. DOI:10.1002/advs.202413017 [Google Scholar]

- Hassanein M, Hoeksema MD, Shiota M, Qian J, Harris BK, Chen H, et al. SLC1A5 mediates glutamine transport required for lung cancer cell growth and survival. Clin. Cancer Res. 2013, 19, 560–570. DOI:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-2334 [Google Scholar]

- Xu T, Liu C, Ning X, Gao Z, Li A, Wang S, et al. Causal relationship between circulating glutamine levels and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: A two-sample mendelian randomization study. BMC Pulm. Med. 2024, 24, 451. DOI:10.1186/s12890-024-03275-4 [Google Scholar]

- Lee TY, Lu HH, Cheng HT, Huang HC, Tsai YJ, Chang IH, et al. Delivery of nitric oxide with a pH-responsive nanocarrier for the treatment of renal fibrosis. J. Control. Release 2023, 354, 417–428. DOI:10.1016/j.jconrel.2022.12.059 [Google Scholar]

- Hamanaka RB, Shin KWD, Atalay MV, Cetin-Atalay R, Shah H, Houpy Szafran JC, et al. Arginine promotes the activation of human lung fibroblasts independent of its metabolism. Biochem. J. 2025, 482, 823–838. DOI:10.1042/BCJ20253033 [Google Scholar]

- Amelio I, Cutruzzolá F, Antonov A, Agostini M, Melino G. Serine and glycine metabolism in cancer. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2014, 39, 191–198. DOI:10.1016/j.tibs.2014.02.004 [Google Scholar]

- Phang JM, Liu W, Hancock CN, Fischer JW. Proline metabolism and cancer: Emerging links to glutamine and collagen. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2015, 18, 71–77. DOI:10.1097/MCO.0000000000000121 [Google Scholar]

- Karadima E, Chavakis T, Alexaki VI. Arginine metabolism in myeloid cells in health and disease. Semin. Immunopathol. 2025, 47, 11. DOI:10.1007/s00281-025-01038-9 [Google Scholar]

- Yadav P, Gómez Ortega J, Dabral P, Tamaki W, Chien C, Chang KC, et al. Myeloid-mesenchymal crosstalk drives Arg1-dependent profibrotic metabolism via ornithine in lung fibrosis. J. Clin. Investig. 2025, 135, e188734. DOI:10.1172/JCI188734 [Google Scholar]

- Cui H, Xie N, Banerjee S, Ge J, Jiang D, Dey T, et al. Lung Myofibroblasts Promote Macrophage Profibrotic Activity through Lactate-induced Histone Lactylation. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2021, 64, 115–125. DOI:10.1165/rcmb.2020-0360OC [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, Li X, Ma Q, Wang Q, Wu J, Yu H, et al. Glutamine Metabolism Is Required for Alveolar Regeneration during Lung Injury. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 728. DOI:10.3390/biom12050728 [Google Scholar]

- Contento G, Wilson JAAM, Selvarajah B, Platé M, Guillotin D, Morales V, et al. Pyruvate metabolism dictates fibroblast sensitivity to GLS1 inhibition during fibrogenesis. JCI Insight 2024, 9, e178453. DOI:10.1172/jci.insight.178453 [Google Scholar]

- Park HY, Kim MJ, Kim YJ, Lee S, Jin J, Lee S, et al. V-9302 inhibits proliferation and migration of VSMCs, and reduces neointima formation in mice after carotid artery ligation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2021, 560, 45–51. DOI:10.1016/j.bbrc.2021.04.079 [Google Scholar]

- Choudhury M, Schaefbauer KJ, Kottom TJ, Yi ES, Tschumperlin DJ, Limper AH. Targeting Pulmonary Fibrosis by SLC1A5-Dependent Glutamine Transport Blockade. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2023, 69, 441–455. DOI:10.1165/rcmb.2022-0339OC [Google Scholar]

- Alhakamy NA, Alamoudi AJ, Asfour HZ, Ahmed OAA, Abdel-Naim AB, Aboubakr EM. L-arginine mitigates bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis in rats through regulation of HO-1/PPAR-γ/β-catenin axis. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2024, 131, 111834. DOI:10.1016/j.intimp.2024.111834 [Google Scholar]

- Steggerda SM, Bennett MK, Chen J, Emberley E, Huang T, Janes JR, et al. Inhibition of arginase by CB-1158 blocks myeloid cell-mediated immune suppression in the tumor microenvironment. J. Immunother. Cancer 2017, 5, 101. DOI:10.1186/s40425-017-0308-4 [Google Scholar]

- Younesi FS, Miller AE, Barker TH, Rossi FMV, Hinz B. Fibroblast and myofibroblast activation in normal tissue repair and fibrosis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2024, 25, 617–638. DOI:10.1038/s41580-024-00716-0 [Google Scholar]

- Li S, Zhang G, Hu J, Tian Y, Fu X. Ferroptosis at the nexus of metabolism and metabolic diseases. Theranostics 2024, 14, 5826–5852. DOI:10.7150/thno.100080 [Google Scholar]

- Zheng H, Zhang L, Wang C, Wang Y, Zeng C. Metabolic dysregulation in pulmonary fibrosis: insights into amino acid contributions and therapeutic potential. Cell Death Discov. 2025, 11, 411. DOI:10.1038/s41420-025-02715-2 [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y, Tong Z, Zhu X, Wu C, Zhou Y, Dong Z. Deciphering the cellular and molecular landscape of pulmonary fibrosis through single-cell sequencing and machine learning. J. Transl. Med. 2025, 23, 3. DOI:10.1186/s12967-024-06031-8 [Google Scholar]

- Jang C, Chen L, Rabinowitz JD. Metabolomics and Isotope Tracing. Cell 2018, 173, 822–837. DOI:10.1016/j.cell.2018.03.055 [Google Scholar]

- Diwan R, Bhatt HN, Beaven E, Nurunnabi M. Emerging delivery approaches for targeted pulmonary fibrosis treatment. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2024, 204, 115147. DOI:10.1016/j.addr.2023.115147 [Google Scholar]

- Deng Z, Kalin GT, Shi D, Kalinichenko VV. Nanoparticle Delivery Systems with Cell-Specific Targeting for Pulmonary Diseases. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2021, 64, 292–307. DOI:10.1165/rcmb.2020-0306TR [Google Scholar]

- Zhao H, Dennery PA, Yao H. Metabolic reprogramming in the pathogenesis of chronic lung diseases, including BPD, COPD, and pulmonary fibrosis. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 2018, 314, L544–L554. DOI:10.1152/ajplung.00521.2017 [Google Scholar]

- Richeldi L, du Bois RM, Raghu G, Azuma A, Brown KK, Costabel U, et al. Efficacy and safety of nintedanib in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 370, 2071–2082. DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa1402584 [Google Scholar]

- Gu X, Zhu Y, Su J, Wang S, Su X, Ding X, et al. Lactate-induced activation of tumor-associated fibroblasts and IL-8-mediated macrophage recruitment promote lung cancer progression. Redox Biol. 2024, 74, 103209. DOI:10.1016/j.redox.2024.103209 [Google Scholar]

- Guo T, Jiang CS, Yang SZ, Zhu Y, He C, Carter AB, et al. Mitochondrial fission and bioenergetics mediate human lung fibroblast durotaxis. JCI Insight 2023, 8, e157348. DOI:10.1172/jci.insight.157348 [Google Scholar]

- Zhang YZ, Jia XJ, Xu WJ, Ding XQ, Wang XM, Chi XS, et al. Metabolic profiling of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in a mouse model: Implications for pathogenesis and biomarker discovery. Front. Med. 2024, 11, 1410051. DOI:10.3389/fmed.2024.1410051 [Google Scholar]

- Tang W, Jiang H, Wu X, Wu G, Zhao C, Lin W, et al. Metabolomic insights into pulmonary fibrosis: A mendelian randomization study. BMC Pulm. Med. 2024, 24, 271. DOI:10.1186/s12890-024-03079-6 [Google Scholar]

- Liu B, Liu W, Li H, Zhai N, Lv C, Song X, et al. circ0066187 promotes pulmonary fibrogenesis through targeting STAT3-mediated metabolism signal pathway. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2025, 82, 79. DOI:10.1007/s00018-025-05613-z [Google Scholar]

- Meliton AY, Cetin-Atalay R, Tian Y, Szafran JCH, Shin KWD, Cho T, et al. Mitochondrial one-carbon metabolism is required for TGF-β-induced glycine synthesis and fibrotic responses. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 9250. DOI:10.1038/s41467-025-64320-2 [Google Scholar]

- Yamada M, Kubo H, Ota C, Takahashi T, Tando Y, Suzuki T, et al. The increase of microRNA-21 during lung fibrosis and its contribution to epithelial-mesenchymal transition in pulmonary epithelial cells. Respir. Res. 2013, 14, 95. DOI:10.1186/1465-9921-14-95 [Google Scholar]

- Yan J, Wang SY, Su Q, Zou MW, Zhou ZY, Shou J, et al. Targeted Immunotherapy Rescues Pulmonary Fibrosis by Reducing Activated Fibroblasts and Regulating Alveolar Cell Profile. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 3748. DOI:10.1038/S41467-025-59093-7 [Google Scholar]

- Deindl S, Elf J. More Than Just Letters and Chemistry: Genomics Goes Mechanics. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2021, 46, 431–432. DOI:10.1016/j.tibs.2021.03.004 [Google Scholar]

- Liu M, Kang GJ, Dudley SC, Jr. Preventing unfolded protein response-induced ion channel dysregulation to treat arrhythmias. Trends Mol. Med. 2022, 28, 443–451. DOI:10.1016/j.molmed.2022.03.006 [Google Scholar]

- Conroy LR, Clarke HA, Allison DB, Valenca SS, Sun Q, Hawkinson TR, et al. Spatial metabolomics reveals glycogen as an actionable target for pulmonary fibrosis. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 2759. DOI:10.1038/s41467-023-38437-1 [Google Scholar]

- Selvarajah B, Azuelos I, Anastasiou D, Chambers RC. Fibrometabolism—An emerging therapeutic frontier in pulmonary fibrosis. Sci. Signal. 2021, 14, eaay1027. DOI:10.1126/scisignal.aay1027 [Google Scholar]