Data Caring While Caring for Human Remains: Challenges of Legacy Collections

Received: 25 November 2025 Revised: 13 January 2026 Accepted: 21 January 2026 Published: 26 January 2026

© 2026 The authors. This is an open access article under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

1. Introduction

For the past 5 years, I have been attentive to the growing emphasis placed on “data”, “data management”, “big data”, “open data”, “FAIR data”, “FAIR Principles” related not only to the trend of digitalisation of museum collections, but also with the dissemination of data associated with research, archives, collections (others), particularly how these would impact collections constituted with human remains. Many of these museum collections have been essential for scientific research on human evolutionary history, disease, and behaviour, among other topics, focusing not only on the analysis of human remains but also on associated biographical data, e.g., [1,2]. In the age of digital circulation and AI, data extracted from human remains crosses new domains, sometimes severed from context. The focus is often on the importance of data extracted and collected from these remains, ensuring they are structured in accordance with the FAIR principles (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable) to facilitate responsible stewardship. However, compliance with FAIR does not necessitate universal openness; rather, it allows for data to be ‘as open as possible, as closed as necessary’ through controlled access mechanisms [3,4,5]. The possibility of accessing data and its reuse allows researchers to build on existing knowledge. In the case of fragile items and human remains, it also contributes to minimising damage, avoiding unnecessary manipulation of the remains and data duplication, and maximising resource efficiency, ensuring more inclusive scientific advancement. The narrative for many who engage with FAIR principles supports the advancement of scientific inquiry by facilitating robust comparative analyses across samples and collections. All acceptable, given the importance of standardisation of data collection for population comparisons across time and space. Clear protocols and precise definitions ensure researchers can gather data consistently and comparably, minimising individual biases and methodological variation, which are often issues. The lack of standardised data is one of the major issues when undertaking comparative studies across or within disciplines, including those with human remains as their foundational element of analysis, e.g., Biological Anthropology, Bioarchaeology, Forensic Anthropology. Jane Buikstra and Douglas Ubelaker’s 1994 publication, Standards for Data Collection from Human Skeletal Remains, was one of the first to address the need for a comprehensive, systematic recording protocol for analysing human remains. This manual includes guidelines on inventorying metric and nonmetric data, anatomical, pathological, and taphonomical-related bine changes, providing essential consistency for comparative research and training in the field [6].

However, addressing data standardisation is not the same as promoting FAIR data principles: a clear distinction is necessary. With this in mind, this manuscript advances three central arguments. First, that the FAIR principles are insufficient to guide the stewardship of ancestors (used here in the broader sense) human remains; second, the CARE principles (Collective Benefit, Authority to Control, Responsibility, Ethics) provide a better and relational framework when considering data associated with human remains [7,8]; and third, researchers, museums and other institutions engaged with the study and/or curation of human remains must move from data accumulation and dissemination, toward a stewardship grounded in sovereignty, relationality, and critical detachment. This manuscript aims to extend the CARE principles beyond their foundational Indigenous Data Governance context, both theoretically and practically. By applying the CARE principles to legacy collections of varied provenance, including archaeological mortuary contexts and contemporary identified collections, this approach broadens the discussion to context-driven and “detached” stewardship for all human remains. I often engage with the question, within the broader discussion of Open Science and the FAIR principles, of how we should think about ancestral remains and associated data in the age of Open Science. Can/should the circulation of digital data ever be disentangled from context? And, most importantly, from provenance? What does it mean to curate human remains not as objects but as persons when dealing with data? And how to address its associated data?

2. Open Science and FAIR Principles

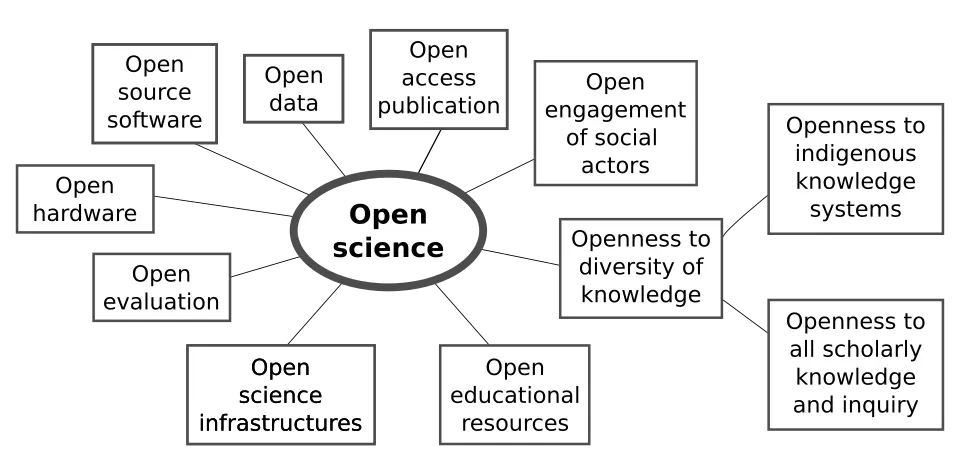

To those working in research and development in Europe, and with funding from the European Commission (both directly and indirectly), the term “Open Science” is a must know (Figure 1). It is an obligation attached to scientific practice, and research designs should consider, from the start, how data will be shared and other decision-making practices that most scholars have not considered or have addressed only briefly. That is, despite the increasing emphasis on Open Science from institutions, governments, and other sectors, a significant literacy gap persists among established researchers, emerging academics, junior scholars, and master’s and PhD students, including science managers, on how to treat data. Many have not received formal training in the principles of open data, ethical sharing, or dissemination platforms or repositories, leading to uncertainty and inconsistent compliance [9,10,11,12]. This lack of foundational understanding often results in superficial adherence to requirements, missed opportunities for collaboration, or, worse, a lack of transparency and misuse of data in research. As the research environment evolves rapidly, especially with the rise of generative artificial intelligence tools, machine learning, and data scraping, there is a pressing need for targeted educational initiatives to cultivate open science. In recent years, several initiatives have promoted Open Science and data management practices; the European Open Science Cloud (EOSC) is but one example [13]. In Portugal, the Forum Gestão de Dados de Investigação (GDI) (https://forumgdi.rcaap.pt/, accessed on 23 January 2026), has been a major contributor to the debate and sharing of ideas, projects, and best practices in research data management, aggregating a numerous professionals who support data management in research institutions and science funding agencies, namely, managers of digital repositories and data centers, libraries and archives technicians, IT specialists, researchers, data scientists, science managers, amongst others. More recently, the Re.Data consortium (https://redata.pt/sobre/#consorcio, accessed on 23 January 2026) has been acting similarly. This consortium has emerged amid the growing importance of data sharing and management, creating services and training programs that support the research data lifecycle and establishing best practices as a priority within scientific institutions in Portugal.

Figure 1. Open science elements based on a UNESCO presentation of 17 February 2021 by RobbieIanMorrison. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/, accessed on the 1 November 2025). Link: Wikimedia Commons https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Osc2021-unesco-open-science-no-gray.svg, accessed on 1 November 2025.

Open Science aims to expand access to data, foster collaboration, and drive scientific innovation [14,15], benefiting scientists and society. Hence, Open science is about ensuring not only that scientific knowledge is accessible, but also that knowledge production is inclusive, equitable, and sustainable. And although it emphasises the sharing of knowledge, results, and tools, it also functions on the principle of ‘as open as possible, as closed as necessary’ [16]. Open science thus sets the standards for researchers, highlighting a layer of scientific responsibility related to data and research practices across Europe and, by proxy, for all those collaborating in European-funded research. We may argue that Open Science, and its ethos of emphasising data openness, transparency, accessibility, and ultimately collaboration, were crystallised in the FAIR principles, and that the continued growth of Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning has further strengthened these principles. However, it is necessary to stress that while Open Science emphasizes transparency, the FAIR principles specifically provide a framework for data stewardship. Hence, being FAIR-compliant—ensuring data is Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable—does not mandate that the data itself be public: access can be restricted or controlled through specific access protocols while still meeting standards for findability and interoperability. However, as data has become a commodity as valuable as gold in an Age of AI, frictions exist on both ethical and legal grounds, and although concerns are rising, Open and FAIR data continues to be the motto [17,18,19,20].

Let’s agree that within Open Science, the FAIR principles play a pivotal role. They enunciate a structured framework for data management, aiming at its sharing and reusability. For this reason, the FAIR principles promote that data should be Findable—easily located through standardised identifiers; Accessible—retrievable through clear protocols, which may include authorization and authentication requirements for restricted datasets; Interoperable—integrated across systems; Reusable—structured for long-term use [3] (Figure 2). FAIR has been widely embraced by funding agencies, journals, and research institutions [21]. It underpins data management in genomics, climate science, and public health, extending from the medical sciences to the social sciences and humanities. While the implementation of these principles has highlighted many possibilities for improving research practices, anchored in transparency, sharing, and inclusiveness, when aligned with Open Science policies, it has also revealed substantial deficiencies within existing scientific collaboration practices. The FAIR principles are not merely technical; they are increasingly ethical, framed as a global responsibility to maximise knowledge production. And most importantly, being FAIR does not necessitate being ‘Open’. Data stewardship under FAIR principles enables controlled access mechanisms, ensuring that sensitive information remains protected while still being findable through robust metadata.

Figure 2. FAIR guiding principles for data resources by Sangya Pundir. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license. (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/, accessed on 1 November 2025). Link: Wikimedia Commons https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:FAIR_data_principles.svg, accessed on 1 November 2025.

There exist numerous contexts in which the ethical, practical, and epistemological concerns warrant sustained critical attention and rigorous debate. This work delimits its scope to a focused analysis of the application of the FAIR principles to human remains, while also considering their broader applicability to heritage collections. The latter is essential, given that a substantial number of human remains are amassed in institutional collections—particularly university-linked museums—amid growing concern, contestation, and controversy [22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31]. Returning to the topic at hand, what does it mean for data associated with human remains to be “findable” or “accessible”? To be Interoperable and Reusable? Not only that, but within the framework of the FAIR principles, metadata standards aggregate human remains, i.e., remains of ancestors, with artefacts and materials, reinforcing the objectification of these ancestors [32]. Also, interoperability will imply standardising the data, overlooking Indigenous epistemologies that resist being reduced to universal categories [7,8,33,34]. On the other hand, we can also argue that reusability perpetuates violence by enabling further circulation of data associated with remains acquired in contexts of violence (broader sense), and almost always without community and/or personal consent. In recent years, various case studies have illustrated these tensions, not necessarily framed within the FAIR principles and Open Science framework, but this is a pressing issue. Indeed, and ironically, for many researchers and the community at large, the implementation of Open Access policies and practices, and the FAIR principles by promoting transparency, openness, and inclusion, has also highlighted many uncomfortable histories related to provenance issues, and the acquisition of many heritage items in museums, including the amassment of remains from human ancestors.

When applied to human ancestors, the FAIR principles are neither neutral nor fair. They risk reinscribing violent practices of acquisition, often colonial practices, by treating ancestors as data, detached from their relational, cultural, and spiritual contexts [32,35]. In this sense, the FAIR principles embody some epistemological assumptions that data are universal, that openness is inherently good, and that ethical concerns can be addressed through access restrictions and/or limitations. Yet human remains are not simply data. And although much of the discussion emphasises Indigenous and colonial frameworks, it should also include other contexts, such as human remains exhumed from archaeological mortuary contexts and from contemporary cemeteries. In the absence of consent, this is an issue: none consented to their exhumation, nor to their study, nor to having their data shared. The FAIR principles’ universalist aspirations risk obscuring this reality, which scholars who have the privilege to study human remains should engage with as part of our professional and human obligations.

3. What About Legacy Collections, Ancestral Human Remains, and FAIR Data?

Inherited collections composed of human remains bring discomfort due to their historical context and procurement practices. The word “inherited” is, in itself, controversial and raises prompts questions about ownership, rights, and ethical treatment, with various cultural and legal implications regarding claims to human remains, a person’s rights, the concept of “personhood”, and ethical research considerations, among many others [36,37,38,39]. Also, for some indigenous communities, the connection people have with their ancestors’ remains is profoundly spiritual, even after death; therefore, all the latter presuppositions are profoundly harmful. For those engaged with such sensitivity, whether from indigenous communities or not, human remains were and ultimately continue to be people [19,22,40,41]. This shift in narrative is challenging when addressing human remains exhumed from archaeological contexts. In most cases, these are described as archaeological “material”. Extensive engagement with professional archaeologists, academics, and students reveals that advocating for human remains as more than ‘material’ or ‘objects’ is frequently met with resistance or prejudice, grounded in established disciplinary practices and evoking an argument that “this is how we have always done it”.

The provenance of the human remains amassed in legacy collections is diverse. Let’s consider legacy collections, in the broader sense, to be those passed down from one curator/researcher to another. The acquisitions of the remains gathered into some of these collections were done via grave-robbing, desecration, looting, and commercialisation of the remains. Some of these collections include not only skeletonised human remains but also mummified people. In some cases, the genealogy of the collections was deeply entangled with colonial projects. I say “was”, but until this entanglement is untangled and dissected, I would argue that these collections continue to be colonial projects (when applicable) [42,43,44,45]. There is also a significant number of ancestors’ remains that were acquired in contemporary cemeteries worldwide, such as those incorporated into reference and/or identified collections and secured by institutional protocols between cemeteries and academic institutions [1,2]. There are also countless human remains amassed into archaeological collections resulting from archaeological digs and treated as heritage goods [39]. Regardless of the acquisition practices, the result of how these ancestors’ remains are kept is similar. Ancestors’ remains are stored in containers, kept in storage rooms, sometimes in poor condition and/or without particular care. This is often the case with human remains exhumed from archaeological digs. The degree of care is positively related to the availability of human and economic resources. Many curators do their best with what they have, and this is always a challenge.

As agglomerated into scientific collections, human remains see their data extracted into databases, folders, or other, and by data, we include an array of formats from photos to measurements to notes to DNA to geochemical information, including the creation of their digital models. And if, for many descendant communities, these ancestors are not “objects” to be studied or catalogued, but persons requiring dignity, care, and return [19,22,35,46,47]; it is also true that, depending on the country, culture, heritage laws and personal sensitivity, for many, ancestral remains in museums and/or collections are alike, and treated as many other artifacts. Hence, although these collections of human remains are referred to as “collections”, stressing that these are in fact human remains is imperative. The last decade has been prolific in scholarly discourses on museum collections composed of human remains, with emphasis on ethical concerns on the one hand and, on the other, detailed promotion of their existence and validity for research and teaching bearing in mind that that these legacy collections have been foundational in fostering various scientific fields, including physical, biological and forensic anthropology, as well as paleopathology and bioarchaeology. They have supported many of our careers and continue to do so (me included).

Therefore, notwithstanding the role studying human remains has played in science, i.e., how they have sustained research in the human past, health and behaviour, the last decade has seen a growing discussion and concern on the provenance of the remains, the historical context of their procurement and acquisition, and the complex relationships between museums and the communities from which these remains originate. For example, Jones (2019) highlighted the complexities and limitations of traditional documentation practices in museums that privilege colonial figures and institutions over Indigenous creators and communities, inviting museums to adopt a relational and polyvocal approach to provenance and documentation of artefacts and archives, by incorporating Indigenous perspectives and fostering community involvement in the process [48].

Unfortunately, the provenance of many legacy collections is not openly discussed, which in an age of advocated Open Science policies and practices may be viewed as ironic and a opportunity to a much-needed open discussion. Should we consider storing, studying, and sharing these legacy collections and associated data? Many were unethically acquired, and, from a scientific viewpoint, they add little new knowledge beyond what is already known, except perhaps in aiding the identification of the individuals who assisted in their return, ideally to the communities of origin. Although the emphasis here is placed on the remains of ancestors, many of these legacy collections hold diverse assemblages of items, including artefacts, documents, art, and audio recordings, all of which are also subject to data extraction and sharing. To view these collections as neutral repositories of knowledge, culture, and/or human heritage is to overlook the exerted social and political dynamics and structural roots that shaped their collection, study, display and now sharing [49,50]. In this sense, legacy collections play a pivotal role in understanding historical contexts, as they are, in themselves, data that illustrate the evolution of acquisition and archival practices.

4. Critiques of FAIR: Objectification and Digital Violence

Why keep holding ancestors in museums, given the procurement practices? Given that they are people, not “things”? Given all that has been written on ethical issues and the handling of human remains over the last few years [19,21,27,37,51,52], why do many of the collections continue to be available for research and study? The answer, for most, is that those remains still hold untapped scientific value for studies of the human past, health, and evolution, as a species, as well as inhabitants of shared ecosystems with other non-human organisms. This is the reasoning of science; however, some descendant communities counter that scientific knowledge cannot outweigh spiritual obligations. The passage of this idea is difficult in cases where human remains have no known descendant communities or advocates; they may find surrogates among those who, professionally or by chance, have embraced the role of curators and stewards. But this often happens only for a limited time: it is often the case with archaeologically exhumed human remains. Ultimately, between the balance of science and society, human remains are “data” for some, and “ancestors” for others. Therefore, any discussion of data governance or Open Science must consider these issues, aiming to avoid repeating past violence in new forms. And there is urgency in such a discussion, as AI waits for no human.

How many of us take the time to consider the provenance of the human ancestral remains used in their studies and research? How many dedicate enough time to consider a data management plan? How many take the time to reflect upon what it means to render data FAIR and available? And, when it came to human remains, what does “as open as possible, as closed as necessary” mean? Critiques of the FAIR principles highlight their complicity in objectifying ancestral human remains, treating them primarily as data sets rather than as culturally significant human entities, and the possibility that access to data may not lead to understanding what they are primarily intended to showcase [53]. By emphasising discoverability, availability, interoperability, and reusability, FAIR transforms ancestral human remains into nodes in the digital networks. Detached from their contexts, they become digital surrogates that circulate independently of the persons they represent and were [54,55,56]. Just as the remains were once catalogued and displayed, digital remains and data are now aggregated and shared, reinforcing hierarchies of knowledge and control. The concerns associated with the digitalisation of human remains are not novel [57,58,59]. Ongoing digital repatriation projects illustrate both the promise and the perils, but, most importantly, the complex and multifaceted process it is, which goes beyond simply returning digital copies of cultural materials to indigenous/other communities [34,60,61]. But note that, when we are addressing Open Science and data sharing, we are not limited to a digital form of the remains, e.g., a specific bone, often enough a skull, but also any associated data, including a person’s DNA. When uploading ancestors’ data to online repositories, often without context and/or consent, and without considering the communities’ objectification and disrespect, we are contributing to the narrative of objectification. Metadata aggregations that list human remains alongside artefacts further contribute to the loss of personhood, reinforcing their objectification (or in this case, datafication). Therefore, FAIR principles can become ethically problematic when applied uncritically to human remains. It perpetuates structural violence through digital means, transforming ancestors into data objects, circulating without consent, stripped of relational context.

5. Data Care While Caring for Human Ancestral Remains

Let us agree that data curation, management, and stewardship are key in scientific research. Hence, the option to care for data while also caring for human ancestors’ remains should not be viewed as mutually exclusive. The CARE principles for Indigenous Data Governance offer a view that focuses not only on data, but also on people [7,8]. The emphasis is on people rather than data, e.g., instead of asking how to make data interoperable, it asks who has the authority to decide whether data should circulate at all. The CARE principals highlight that data governance must advance: Collective Benefit—data should support the well-being of communities; Authority to Control—Indigenous peoples retain sovereignty over their data; Responsibility—researchers must act with accountability; and Ethics—decisions must respect cultural protocols and dignity. Arguably, the CARE principles were developed for Indigenous Data Governance; however, they are applicable to other contexts, including those involving data collected from human remains linked to various communities, or even those remains whose associated communities are unknown, and/or unable to be ascertained. The CARE principles challenge the idea that data should be shared, as they contextualise data differently than the FAIR principles. Instead, they reframe data thinking by adding that some data should either not be shared at all or remain under community control. Data is repositioned, contextualised, and linked to its origin, enabling a more conscious approach to provenance and broader context. Demanding that data provenance be addressed drives each one to consider ethical issues related to data provenance, sovereignty, and the “meaning” of the data and its associated context. We must question conventional ideas of objectivity in the creation of scientific knowledge since the concept of situated knowledges emphasises relationality [62]. According to this epistemological perspective, all knowledge is fundamentally contextual and local, influenced by particular social, cultural, and historical factors. Haraway’s framework encourages researchers to acknowledge the privileges and limitations of their own positions, recognising the importance of one’s positionality and the role it plays in the research process, and calling for the adoption of reflexive practices that consider the power dynamics at play in one’s work. Hence, the intertwinement of CARE and FAIR principles has practical consequences. Rethinking cataloguing systems is necessary as we consider whether human ancestors’ remains belong in the same database as artefacts; metadata must change from characterising remains as objects to recognising their status as persons; and policies must be updated to prioritise care. Museums and researchers can stop seeing human remains as data by adopting this reframing. This realisation changes the epistemological underpinnings of heritage work, and ultimately our relation to ancestors’ human remains.

6. Moving Forward: Detachment and Critical Thinking

What does caring for ancestral human remains should be in the 21st century? It requires a paradigm change from data collection and sharing to caring, from universalism to sovereignty, and from transparency to personal accountability. Institutions must update their policies to reflect CARE principles rather than just FAIR. This includes embedding authority-to-control within collections (since the remains continue to be identified as such), management systems, and ensuring that descendant communities and/or associated communities, and/or those that care for the remains, determine access conditions. Some institutions have already taken steps to incorporate the CARE principles into their research data management policies and guidelines (e.g., University of Cambridge, University of Oslo, Massey University, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, and Berdyansk State Pedagogical University [63,64,65,66,67], all of which explicitly reference CARE to guide ethical data stewardship. The adoption of CARE principles into open research and research data management policies, and open research resources, demonstrates that embedding community-led governance into university policy is feasible and adds to scientific advancement.

Away from academia, other examples include the Mukurtu CMS platform, which showcases an example of hybrid governance, enabling communities to manage digital heritage through layered access protocols that embed cultural rules into its technical design [68]. Their mission statement is clear: “Mukurtu (MOOK-oo-too) is a grassroots project aiming to empower communities to manage, share, narrate, and exchange their digital heritage in culturally relevant and ethically-minded ways. We are committed to maintaining an open, community-driven approach to Mukurtu’s continued development. Our first priority is to help build a platform that fosters relationships of respect and trust” (https://mukurtu.org/about/, accessed on 20 November 2025). Another example is that of the Plateau Peoples’ Web Portal (https://plateauportal.libraries.wsu.edu/about, accessed on 20 November 2025).). It empowers tribes to annotate, restrict, or release materials in accordance with their own protocols. Both these platforms are examples of prioritising sovereignty and ethics. Of course, there is always a question to be posed here: what about human ancestral remains with no living communities, such as those exhumed from archaeological contexts? In such cases, I would argue that the responsibility of care extends to researchers and other stakeholders. All those involved in the excavation, exhumation, study, and curation processes, including universities, museums, and governments, must recognise their positionality and resist what may be considered extractive practices. For a researcher to simply access data, extract what is necessary, conduct research, and leave is no longer acceptable, nor is merely sharing data of one’s research. There is a duty of care and professional responsibility. And here, there is still a lot to do to engage scholars with inclusive ways of doing research. As exemplified by indigenous methodologies, we should prioritise reciprocity and care, requiring researchers to act as allies rather than extractors. Funding agencies should support projects that prioritise ethics, even when this limits openness or delays publication, contrary to Open Access policies.

Also, ethically, stewardship means acknowledging that not all data should be open, that sovereignty must override universalism, and that the remains of human ancestors require care rather than classification. Ethical responsibility is not an obstacle to science: it may pose challenges and call for new ways of thinking and working, but without it, research perpetuates the very violence it claims to overcome. This also applies to all associated data being produced. Data are never just Data; to view them as such is but to replicate ongoing structural violence and/or a new form of objectification via digital formats. Hence, critical thinking requires resisting the impulse to universalise openness. The proclamation of Open Science—“as open as possible, as closed as necessary”—cannot adequately address the ethical issues related to the curation, use, and dissemination of data associated with ancestral remains. Sometimes the most ethical action is closure: not to digitise, not to share, not to publish. Community engagement is, therefore, the way to establish new scientific practices.

Over the past 20 years, scholarly approaches to museum collections made up of human remains have changed dramatically, reflecting broader ethical concerns as well as a growing focus on cultural sensitivity and community involvement. Looking back on my PhD research, based on human remains from Portuguese Identified Skeletal Collections (as called), I would certainly be doing things very differently [69]. Researchers have explored various facets of these collections, including repatriation, ethical stewardship, visitor perceptions, and historical contexts [22,23,26]. Mutyandaedza, who addresses the storage methods of human remains in Zimbabwean museums, does a good job of expressing the emotional impact of human remains, especially in non-Western contexts. The storage of the remains highlights the emotional toll of their assembly, which stems from colonial histories that resonate within impacted communities, even though they are not on display [70]. Mutyandaedza advocates for museum practices that honour cultural significances through restitution and community involvement, reinforcing the broader movement towards ethical stewardship. The interaction between indigenous rights and museum practices creates a landscape in which museums must navigate complex ethical dilemmas while balancing scientific research needs with communities’ desires for repatriation [70,71]. When focusing on archaeological collections with no information on the communities from which these remains originate, the same approach should be considered. They remain ancestral human remains and deserve the same care. In a culture that rewards accumulation, detachment means recognising the value of restraint. For researchers, this may mean declining to analyse human remains when communities object, reconsidering an invasive research design, or even limiting the amount of information gathered. However, these constraints may also offer new ways to conduct research and share data. For museums, this may mean limiting access to the remains, restricting data gathering, removing digital images or human remains from public databases, and rethinking curation practices. For funders, it may mean valuing ethical care as much as scientific output, treating ancestors’ remains as persons and respecting descendant communities, or surrogates. Moving forward, the goal is not simply to manage and share data but to cultivate ethical relations with integrity and transparency. This requires humility, restraint, and respect. It demands that researchers and institutions cede authority, recognising that some decisions are not theirs to make.

7. Conclusions

More recent literature on human remains in museums indicates an evolving landscape, with scholars advocating for more informed and culturally sensitive practices and recognising the significant historical and ethical implications of their collection. Legacy collections of ancestral remains embody both memory and violence. They preserve traces of the past, but they also testify to histories of desecration, dispossession, and scientific racism. In the age of Open Science, the challenge is not whether to open or close data, but how to address these issues ethically, whether data should even be collected, and whether these ancestors should be kept as collectives in museums and other institutions alike. Hence, this challenge requires a shift in perspective, not just of practices and policies. It requires recognising human remains not as objects but as persons, not as data but as relations. Such an approach acknowledges that these remains and their associated data are not isolated, nor mere points of information, but are fundamentally defined by their relationality and cultural context. Only by embracing this reframing can museums and researchers move beyond colonial legacies and objectification practices and toward futures grounded in reconciliation and care.

Although technically robust, we could argue that the FAIR Data principles are not fair, and this statement aims to be thought-provoking. FAIR principles lack a corresponding ethical framework to address ancestral remains associated data. They do not acknowledge various forms of knowledge viewing or dignify ancestral remains; instead, a purely technical application of these principles sustains a new form of objectification through the digital replication of ongoing structural violence: Data are never just Data. There has been growing concern about data care and stewardship amongst museums and allied institutions, and although the argument is based on the fairness and conscious ethical sharing, any collection and associated data need to be questioned about their origins, as many were unethically acquired. Ultimately, integrating CARE principles alongside FAIR principles may advance the shift in perspective required. For example, data management plans and policies must evolve from being mere technical checklists into frameworks for mandatory ethical reflection on data provenance and the prevention of digital objectification. Furthermore, funding and institutional requirements should prioritise ‘ethical sharing’ over universal openness, formally recognising that some ancestral data must remain restricted to respect community sovereignty and personhood. Finally, institutional (e.g., museums, universities) repositories must transition from neutral data aggregators to active ethical stewards, implementing metadata standards that distinguish human remains from artefacts and adopting ‘as closed as necessary’ protocols to ensure that data circulation does not perpetuate historical or digital violence.

There has been a conscious move away from the traditional classification of ancestral remains as “material” or “objects”. Human remains are, were, and remain people if one uses multiple lenses of knowledge, beliefs, and senses. They are not collections, objects, or exotic artefacts to be easily displayed, exchanged, measured, photographed, stored, and transformed into data and disseminated. Ethical issues no longer relate solely to ancestral remains; they extend to their data and metadata across matters related to governance, circulation, “ownership?”, and repatriation. Alongside FAIR, one must practice CARE, and above all, allow for detachment and critical thinking: even of one’s own work.

Statement of the Use of Generative AI and AI-Assisted Technologies in the Writing Process

During the preparation of this manuscript Grammarly (2025) was used to address typographical/spelling and grammatical errors, and to provide writing clarity. All content was revised, and I take full responsibility for the manuscript content.

Acknowledgments

I would like to express my gratitude and respect to the people whose remains I had the privilege to study, and with whom I have learnt and grown over these years. I would also like to extend my thanks to all those with whom I have shared and discussed opinions and experiences: all welcome. This manuscript was presented as a poster at the 5a Encontro Nacional do IN2PAST, Universidade do Minho, Braga, Portugal, 22–25 January 2025. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14837128.

Ethics Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No data was produced during the development of this manuscript.

Funding

This research is funded by Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia through CRIA—Center for Research in Anthropology Strategic Development Plan grant number [UID/04038/2025], and IN2PAST—Laboratório Associado para a Investigação e Inovação em Património, Artes, Sustentabilidade e Território grant number [LA/P/0132/2020]. Francisca Alves Cardoso is also funded by the project Life After Death grant number [2020.01014.CEECIND/CP1634/CT0002], and FCT funding reference [2023.11076.TENURE.188]. This research is also part of the BeFRAIL project—Porto in Times of Cholera and War: A Bioarchaeological Approach to Human Frailty grant number [2022.02398.PTDC], DOI: https://doi.org/10.54499/2022.02398.PTDC.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The author declares that she has no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Henderson CY, Cardoso FA. Identified Skeletal Collections: The Testing Ground of Anthropology?; Archaeopress: Oxford, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Alves-Cardoso F, Campanacho V. The Scientific Profiles of Documented Collections via Publication Data: Past, Present, and Future Directions in Forensic Anthropology. Forensic Sci. 2022, 2, 37–56. DOI:10.3390/forensicsci2010004 [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson MD, Dumontier M, Aalbersberg IJ, Appleton G, Axton M, Baak A, et al. The FAIR Guiding Principles for scientific data management and stewardship. Sci. Data 2016, 3, 160018. DOI:10.1038/sdata.2016.18 [Google Scholar]

- Landi A, Thompson M, Giannuzzi V, Bonifazi F, Labastida I, da Silva Santos LOB, et al. The “A” of FAIR—As open as possible, as closed as necessary. Data Intell. 2020, 2, 47–55. DOI:10.1162/dint_a_00027 [Google Scholar]

- Jati PHP, Lin Y, Nodehi S, Cahyono DB, van Reisen M. FAIR versus open data: A comparison of objectives and principles. Data Intell. 2022, 4, 867–881. DOI:10.1162/dint_a_00176 [Google Scholar]

- Buikstra JE, Ubelaker DH. Standards for Data Collection from Human Skeletal Remains: Proceedings of a Seminar at the Field Museum of Natural History, 12154th ed.; Arkansas Archeological Survey: Fayetteville, NC, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll SR, Garba I, Figueroa-Rodríguez OL, Holbrook J, Lovett R, Materechera S, et al. The CARE Principles for Indigenous Data Governance. Data Sci. J. 2020, 19, 43. DOI:10.5334/dsj-2020-043 [Google Scholar]

- GIDA. CARE Principles for Indigenous Data Governance. Available online: https://www.gida-global.org/care (accessed on 15 January 2026).

- Ferguson J, Littman R, Christensen G, Paluck EL, Swanson N, Wang Z, et al. Survey of open science practices and attitudes in the social sciences. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 5401. DOI:10.1038/s41467-023-41111-1 [Google Scholar]

- Balafoutas L, Celse J, Karakostas A, Umashev N. Incentives and the replication crisis in social sciences: A critical review of open science practices. J. Behav. Exp. Econ. 2025, 114, 102327. DOI:10.1016/j.socec.2024.102327 [Google Scholar]

- Alter U, Crone G, Camilleri C, Counsell A. A mismatch between open science practices and intentions in North America: Barriers and incentives for early-career and senior researchers. Can. Psychol. 2025, in press. DOI:10.1037/cap0000446 [Google Scholar]

- Brohmer H, Hoffmann MF. The struggle to make transparency mainstream: Initial evidence for a slow uptake of open science practices in PhD theses. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2025, 12, 250826. DOI:10.1098/rsos.250826 [Google Scholar]

- Almeida AV, Borges MM, Roque L. The European Open Science Cloud: A New Challenge for Europe. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Technological Ecosystems for Enhancing Multiculturality (TEEM 2017), Cádiz, Spain, 18–20 October 2017; Article 32, pp. 1–4. DOI:10.1145/3144826.3145382 [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. UNESCO Open Science Toolkit; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. An Introduction to the UNESCO Recommendation on Open Science; Canadian Commission for UNESCO: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Méndez E, Cueva J. Open Science and Intellectual Property Rights; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Chandrasekhar R. Legal Frictions for Data Openness: Reflections from a Case-Study on Re-Use of the Open Web for AI Training; Center Internet et Société—CNRS, INNO3, Open Knowledge Foundation: Paris, France, 2025; p. 75. Available online: https://hal.science/hal-05009616v2 (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Hosseini M, Horbach SPJM, Holmes K, Ross-Hellauer T. Open Science at the generative AI turn: An exploratory analysis of challenges and opportunities. Quant. Sci. Stud. 2025, 6, 22–45. DOI:10.1162/qss_a_00337 [Google Scholar]

- Burgelman JC, Pascu C, Szkuta K, Von Schomberg R, Karalopoulos A, Repanas K, et al. Open Science, Open Data, and Open Scholarship: European Policies to Make Science Fit for the Twenty-First Century. Front. Big Data 2019, 2, 43. DOI:10.3389/fdata.2019.00043 [Google Scholar]

- Martorana M, Kuhn T, Siebes R, van Ossenbruggen J. Aligning restricted access data with FAIR: A systematic review. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 2022, 8, e1038 DOI:10.7717/peerj-cs.1038 [Google Scholar]

- Mons B. Data Stewardship for Open Science: Implementing FAIR Principles; Chapman and Hall/CRC: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson Stutz L. Between objects of science and lived lives. The legal liminality of old human remains in museums and research. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2023, 29, 1061–1074. DOI:10.1080/13527258.2023.2234350 [Google Scholar]

- Robbins Schug G, Halcrow SE, de la Cova C. They Are People Too: The Ethics of Curation and Use of Human Skeletal Remains for Teaching and Research. Am. J. Phys. Anthr. 2025, 186, e70013. DOI:10.1002/ajpa.70013 [Google Scholar]

- Watkins R, Muller J. Repositioning the Cobb human archive: The merger of a skeletal collection and its texts. Am. J. Hum. Biol. 2015, 27, 41–50. DOI:10.1002/ajhb.22650 [Google Scholar]

- de la Cova C, Hofman CA, Marklein KE, Sholts SB, Watkins R, Magrogan P, et al. Ethical futures in biological anthropology: Research, teaching, community engagement, and curation involving deceased individuals. Am. J. Phys. Anthr. 2024, 185, e24980. DOI:10.1002/ajpa.24980 [Google Scholar]

- Muller JL, Pearlstein KE, de la Cova C. Dissection and Documented Skeletal Collections: Embodiments of Legalized Inequality. In The Bioarchaeology of Dissection and Autopsy in the United States; Nystrom KC, Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 185–201. [Google Scholar]

- Geller PL. Building Nation, Becoming Object: The Bio-Politics of the Samuel G. Morton Crania Collection. Hist. Arch. 2020, 54, 52–70. DOI:10.1007/s41636-019-00218-3 [Google Scholar]

- Cornwall J, Champney TH, de la Cova C, Hall D, Hildebrandt S, Mussell JC, et al. American Association for Anatomy recommendations for the management of legacy anatomical collections. Anat. Rec. 2024, 307, 2787–2815. DOI:10.1002/ar.25410 [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal SC. The bioethics of skeletal anatomy collections from India. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1692. DOI:10.1038/s41467-024-45738-6 [Google Scholar]

- Roque R. Headhunting and Colonialism: Anthropology and the Circulation of Human Skulls in the Portuguese Empire, 1870–1930; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Van Beurden J. Inconvenient Heritage: Colonial Collections and Restitution in the Netherlands and Belgium; Amsterdam University Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Christen K. Does Information Really Want to be Free? Indigenous Knowledge Systems and the Question of Openness—Washington State University. Int. J. Commun. 2012, 6, 2870–2893. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/2376/5705 (accessed on 20 November of 2025).

- Garba I, Sterling R, Plevel R, Carson W, Cordova-Marks FM, Cummins J, et al. Indigenous Peoples and research: Self-determination in research governance. Front. Res. Metr. Anal. 2023, 8, 1272318. DOI:10.3389/frma.2023.1272318 [Google Scholar]

- Kukutai T, Taylor J. Indigenous Data Sovereignty: Toward an Agenda; ANU Press: Canberra, Australia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Colwell C. Plundered Skulls and Stolen Spirits: Inside the Fight to Reclaim Native America’s Culture; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Charlier P. Naming the body (or the bones): Human remains, anthropological/medical collections, religious beliefs, and restitution. Clin. Anat. 2014, 27, 291–295. DOI:10.1002/ca.22358 [Google Scholar]

- Sholts SB. “To honor and remember”: An ethical awakening to African American remains in museums. Am. J. Biol. Anthr. 2025, 186, e24943. DOI:10.1002/ajpa.24943 [Google Scholar]

- Doğan E, Thys-Şenocak L, Joy J. Who Owns the Dead? Legal and Professional Challenges Facing Human Remains Management in Turkey. Public Archaeol. 2021, 20, 85–107. DOI:10.1080/14655187.2022.2070209 [Google Scholar]

- Marquez-Grant N, Fibiger L. The Routledge Handbook of Archaeological Human Remains and Legislation; Routledge: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Gruenthal‐Rankin A, Somogyi T. Opening the Cabinets: A Critical Evaluation of Skeletal Teaching Collections in the United States. Am. J. Biol. Anthropol. 2025, 186, e25051. DOI:10.1002/ajpa.25051 [Google Scholar]

- Cornwall J, Hildebrandt S, Champney TH, DeLeon VB. Interdisciplinary Interaction and Engagement Around the Use of Human Remains: Comment on “They Are People Too: The Ethics of Curation and Use of Human Skeletal Remains for Teaching and Research”. Am. J. Biol. Anthropol. 2025, 187, e70089. DOI:10.1002/ajpa.70089 [Google Scholar]

- Harrison R. Heritage: Critical Approaches; Routledge: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Biers T, Clary KS. The Routledge Handbook of Museums, Heritage, and Death; Routledge: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Redman S. Bone Rooms; Harvard University Press: Harvard, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Besterman TP. Contested human remains in museums: Can ‘Hope and History Rhyme’? In The Routledge Companion to Indigenous Repatriation; Routledge: London, UK, 2020; pp. 940–960. [Google Scholar]

- Tarlow S. The Names of the Dead: Identity, Privacy and the Ethics of Anonymity in Exhibiting the Dead Body. Public Archaeol. 2023, 22, 1–20. DOI:10.1080/14655187.2023.2268384 [Google Scholar]

- Simpson M. Making Representations: Museums in the Post-Colonial Era; Routledge: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Jones M. Collections in the Expanded Field: Relationality and the Provenance of Artefacts and Archives. Heritage 2019, 2, 884–897. DOI:10.3390/heritage2010059 [Google Scholar]

- de Oliveira BH, Bizerra AF. Social participation in science museums: A concept under construction. Sci. Educ. 2024, 108, 123–152. DOI:10.1002/sce.21829 [Google Scholar]

- Dan H. The Brutish Museums: The Benin Bronzes, Colonial Violence and Cultural Restitution; Pluto Press: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Barron J, Bayles B, Hamilton MD. Educational, But Ethical? The Tension Within Historic Skeletal Collections. Pract. Anthropol. 2025, 1–11. DOI:10.1080/08884552.2025.2544568 [Google Scholar]

- Squires K, Errickson D, Márquez-Grant N. Ethical Approaches to Human Remains: A Global Challenge in Bioarchaeology and Forensic Anthropology; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Pilcher J, Vermeylen S. From Loss of Objects to Recovery of Meanings: Online Museums and Indigenous Cultural Heritage. M/C J. 2008, 11. DOI:10.5204/mcj.94 [Google Scholar]

- Hess M, Robson S, Serpico M, Amati G, Pridden I, Nelson T. Developing 3D Imaging Programmes—Workflow and Quality Control. J. Comput. Cult. Herit. 2015, 9, 1–11. DOI:10.1145/2786760 [Google Scholar]

- Hess M, Simon Millar F, Robson S, MacDonald S, Were G, Brown I. Well Connected to Your Digital Object? E-Curator: A Web-based e-Science Platform for Museum Artefacts. Lit. Linguist. Comput. 2011, 26, 193–215. DOI:10.1093/llc/fqr006 [Google Scholar]

- Geismar H. Museum Object Lessons for the Digital Age; UCL Press: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Plemons AM, Spiros MC. Toward Ethical Digital Practices: Guidelines for Consent, Accountability, and Transparency in Anthropology. Am. J. Biol. Anthropol. 2025, 186, e70044. DOI:10.1002/ajpa.70044 [Google Scholar]

- Carew RM, French J, Rando C, Morgan RM. Exploring public perceptions of creating and using 3D printed human remains. Forensic Sci. Int. Rep. 2023, 7, 100314. DOI:10.1016/j.fsir.2023.100314 [Google Scholar]

- Alves-Cardoso F, Campanacho V. To replicate, or not to replicate? The creation, use, and dissemination of 3D models of human remains: A case study from Portugal. Heritage 2022, 5, 1637–1658. DOI:10.3390/heritage5030085 [Google Scholar]

- Bell JA, Christen K, Turin M. After the Return. Mus. Worlds 2013, 1, 195–203. DOI:10.3167/armw.2013.010112 [Google Scholar]

- Suchikova Y, Nazarovets S. Extending the CARE Principles: Managing data for vulnerable communities in wartime and humanitarian crises. Sci. Data 2025, 12, 420. DOI:10.1038/s41597-025-04756-9 [Google Scholar]

- Haraway D. Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective. Fem. Stud. 1988, 14, 575–599. DOI:10.2307/3178066 [Google Scholar]

- University of Oslo. Policies and Guidelines for Research Data Management. Available online: https://www.uio.no/english/for-employees/support/research/research-data-management/policies-guidelines.html (accessed on 15 January 2026).

- Massey University. Research Data Management Policy. Available online: https://www.massey.ac.nz/documents/2138/Research_Data_Management_Policy.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2026).

- University of Cambridge. Research Data Management—CARE Principles. Available online: https://www.data.cam.ac.uk/policies-ethics-legal/care-principles (accessed on 15 January 2026).

- Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam. CARE Principles—What Are the CARE Principles? Available online: https://rdm.vu.nl/topics/care-principles.html (accessed on 15 January 2026).

- Suchikova Y, Nazarovets S. Strategy for Open Science Development at Berdyansk State Pedagogical University. Zenodo 2025. DOI:10.5281/zenodo.15007508 [Google Scholar]

- Christen K, Merrill A, Wynne M. A Community of Relations: Mukurtu Hubs and Spokes. D-Lib. Mag. 2017, 23, 1–9. DOI:10.1045/may2017-christen [Google Scholar]

- Alves Cardoso F. A Portrait of Gender in Two 19th and 20th Century Portuguese Populations: A Palaeopathological Perspective. Ph.D. Thesis, Durham University, Durham, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Mutyandaedza B. Reclaiming Lost Memory: Reflections on the Restitution of Cultural Material Within the Local Context, with Specific Reference to Zimbabwe. Collections 2025, 21, 339–353. DOI:10.1177/15501906251331299 [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher S. Museums and the Return of Human Remains: An Equitable Solution? Int. J. Cult. Prop. 2010, 17, 65–86. DOI:10.1017/S0940739110000019 [Google Scholar]