Consanguineous Marriage in Global Perspective: Anthropological Roots, Genetic Risks, Contemporary Relevance, and the Way Forward

Received: 23 September 2025 Revised: 03 November 2025 Accepted: 17 December 2025 Published: 29 December 2025

© 2025 The authors. This is an open access article under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

1. Introduction

Consanguineous marriage refers to a union between individuals who share a common ancestor, typically first or second cousins, and has been practiced for millennia across diverse societies [1,2,3,4,5,6,7]. However, consanguinity was not formally defined by a single individual. Instead, consanguinity has been studied, classified, and interpreted across various disciplines—including anthropology, sociology, genetics, law, etc. Scholars like L.H. Morgan (1871) in his foundational work Systems of Consanguinity and Affinity of the Human Family, classified kinship systems and documented the social rules governing cousin marriage [5]. C. Lévi-Strauss (1949), a renowned scholar, interpreted consanguineous unions as mechanisms of alliance and reciprocity between groups in his book The Elementary Structures of Kinship. Fox (1967), later in his seminal work Kinship and Marriage: An Anthropological Perspective, emphasized that cousin marriage represents a culturally regulated form of social organization rather than a biological anomaly [3]. Fox (1967) identified cross-cousin marriage and parallel-cousin marriage, and emphasized that cross-cousin marriage is widely favored in many matrilineal and alliance-based societies, as it promotes exchange and reciprocity between lineages [3]. Fox (1967) argues that cousin marriage preferences are not biologically driven but socially constructed rules that help to organize and reproduce social relationships [3]. He quotes:

“The form of cousin marriage a society chooses—if any—is a function of its descent rules and its ideas of where property and authority ought to flow” (Fox 1967: 158) [3].

Beyond anthropological investigation, consanguineous marriage continues to attract multidisciplinary interest for its implications in bio-medical, genetics, demography, and public health [2,8,9,10,11,12]. While biomedical studies highlight elevated genetic risks such as congenital disorders and infant mortality, anthropological and sociological research demonstrates that such unions often reinforce kin solidarity, economic stability, and cultural continuity. Kalam et al. (2024) found that consanguinity heightens stillbirth and neonatal post-neonatal mortality risks; its effect is milder in close unions, reflecting enhanced alloparental support—a dimension that shows the bio-social aspect of consanguinity [10]. Wright (1922) found that consanguinity tends to reduce genetic variability and may decrease vigour due to inbreeding depression, though it can also help in fixing desirable traits under certain controlled conditions [13]. Sabbagh et al. (2014) found that consanguinity is a significant risk factor for nonsyndromic orofacial clefts (NSOFC), indicating nearly twice the risk among children born to consanguineous parents [14]. Studies have shown that consanguinity may increase spousal violence [15] while also enhancing social solidarity and old age security [16].

Thus, understanding the coexistence of socio-cultural and bio-medical costs underscores consanguinity as a complex bio-social phenomenon. Given the diverse and at times contradictory findings across disciplines, there is a clear need for an integrated and updated review that synthesizes anthropological, sociological, and biomedical perspectives to better understand the multifaceted implications. The present paper seeks to examine global and regional patterns of consanguineous marriage by tracing its historical roots, theoretical foundations, cultural rationales, and shifting dynamics in relation to modernity, migration, and public health. By integrating anthropological insights with recent demographic and biomedical evidence, the presentreview provides a comprehensive understanding of consanguinity as both a culturally embedded social institution and a contemporary health concern.

2. Materials and Methods

We conducted a comprehensive and systematic literature search using multiple renowned academic databases and digital libraries to collect scholarly materials related to consanguineous marriage. These included PubMed, Web of Science (formerly Web of Knowledge), Google Scholar, JSTOR, the National Digital Library of India (NDLI), Wiley, Springer, Elsevier, AnthroSource, Anthropology Plus, the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS), and reports from the World Health Organization’s Eastern Mediterranean Regional Office (WHO EMRO). PubMed, maintained by the U.S. National Library of Medicine, was instrumental in providing access to peer-reviewed biomedical and genetic research articles. Web of Science enables exploring multidisciplinary journals with strong citation tracking for scientific rigor. Google Scholar, as a freely accessible academic search engine, offered a wide array of sources, including articles, theses, books, and conference papers. JSTOR facilitated access to archived literature, especially in anthropology and the social sciences. NDLI, an initiative of the Government of India, allowed for the inclusion of region-specific academic works, institutional repositories, and vernacular publications. Wiley, Springer, and Elsevier databases provided international peer-reviewed journals relevant to genetic counseling and cross-cultural studies. AnthroSource and Anthropology Plus contributed specialized ethnographic and kinship-focused literature. Additionally, demographic patterns and prevalence data were gathered from national and regional DHS datasets, while WHO EMRO reports offered vital insights into the public health implications of consanguinity in Arab and Muslim-majority countries.

We developed the search strategy to capture a comprehensive range of publications, encompassing both seminal early works on consanguineous marriage and the more recent studies that continue to shape contemporary and future debates on the subject. We applied specific filters to collect studies that explored especially anthropological perspectives of consanguineous marriages, along with their types, prevalence, effects of such marriages, changing patterns, policy implications, as well as ethnographic voices. The retrieved literature included peer-reviewed journal articles, book chapters, and online resources. While some studies drew on nationally representative datasets, others provided in-depth insights from local community-level research.

Each database yielded citations in various formats (e.g., APA, MLA, Chicago, Harvard, and Vancouver), and we used Mendeley, a reference management software, to systematically organize, annotate, and cite all references throughout the study. All selected sources were thoroughly reviewed to ensure their relevance, reliability, and academic integrity.

3. Classification of Consanguineous Marriages

The anthropological categorization of consanguineous marriage involves categorizing such unions based on cultural, kinship, and lineage systems across societies. Anthropologists analyze consanguineous marriage not only in terms of biological relatedness but also as a social institution that reinforces alliances, lineage continuity, property transmission, and identity [3,6,9,10,11,16,17].

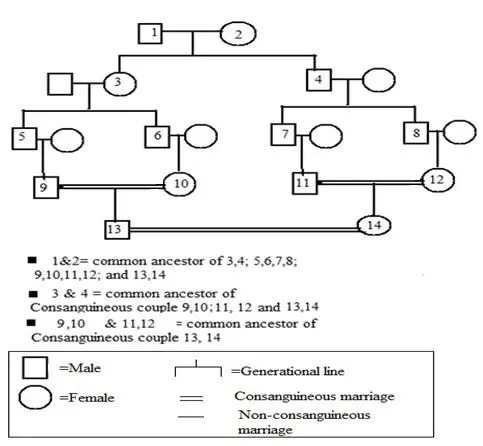

3.1. Classification by Degree of Relatedness

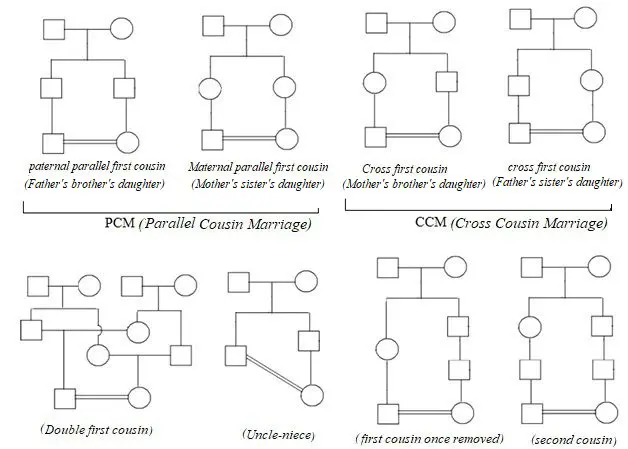

Consanguineous unions are primarily defined by biological proximity. First cousin marriages, i.e., marriagesbetweenindividualswhoshareacommongrandparent, are the most prevalent worldwide, notably in the Middle East, North Africa, and South Asia [1,2,7]. Marriage between the son and daughter of two same-sexsiblings (such as Father’s brother or Mother’s sister) is classified as a parallel cousin marriage(PCM), in which father’s brother’s daughter (FBD) is predominant in Arab-Islamic societies and often reinforces agnatic lineage ties [5,12,17]. Whilemarriages between a son and a daughter of two different-sexsiblings (such as Father’s sister/Mother’s brother) are categorized as cross-cousin marriage (CCM), among which mother’s brother’s daughter (MBD) is common in South Indian Dravidian kinship systems and often preferred by custom [18]. Second-cousin marriages occur in societies where first-cousin unions are less culturally preferred. Uncle-niece marriages, though rare, are practiced among certain South Indian castes and historically in royal lineages, such as ancient Egypt [3,5]. Double cousin marriages, where both maternal and paternal sides are connected, aim to maximize kinship bonds and property consolidation [19,20]. The common connections and types of cousin marriage have been presented in Figure 1 and Figure 2, respectively.

3.2. By Cultural-Kinship Systems

Dravidian Kinship Systems: Cross-cousin marriage (mother’s brother’s daughter or father’s sister’s son) is often prescriptive, facilitating alliances between lineages [18]. Arab-Islamic Kinship: Preference for patrilateral parallel cousin marriage supports endogamy, preserves tribal cohesion, and maintains wealth within the paternal line [19,21]. African Lineage Systems: Varying traditions exist, with some practicing cousin marriage and others favoring exogamy; patterns are often shaped by descent and bridewealth institutions [22]. Christian-European Societies: Canon law historically proscriptive cousin marriage, especially under Roman Catholicism, due to concerns over genetic risks and moral doctrine [23].

4. Worldwide Prevalence of Consanguineous Marriages

In prehistoric times, the prevalence of consanguineous marriage varied significantly between hunter-gatherer and early agricultural societies. Among hunter-gatherers, small group sizes and high mobility often resulted in relatively low rates of close kin marriage, especially beyond first cousins. While some degree of consanguinity was inevitable due to limited population sizes, many hunter-gatherer groups practiced forms of exogamy to avoid inbreeding, favoring marriage outside the immediate band or clan [24]. In contrast, with the advent of agriculture during the Neolithic period, sedentary life and increased population densities enabled more stable kinship systems. This transition saw a rise in consanguineous marriages in some regions, particularly among early agriculturalists who began to use marriage to consolidate land, property, and social alliances within extended family groups [25]. In such contexts, cousin marriages—especially between parallel and cross cousins—could become culturally institutionalized to maintain lineage cohesion and resource control. Thus, while consanguineous marriage among hunter-gatherers was typically limited by ecological and social factors, early agricultural societies showed a growing tendency toward kin-based marital practices, which laid the foundation for many historical and contemporary patterns of cousin marriage.

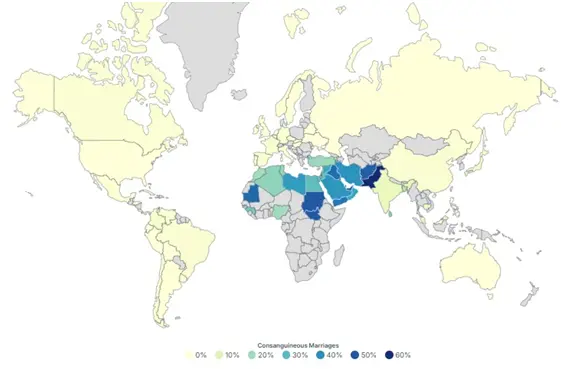

The practice of consanguineous marriage is globally heterogeneous in nature, ranging from cultural normativity in parts of Asia and the Middle East to virtual extinction in Western nations [7]. It reflects deep socio-cultural, economic, and political systems and is undergoing a gradual transformation in many regions due to urbanization, education, and genetic awareness. The detailed compilation of the worldwide prevalence of consanguineous marriage, supported by authors, years, and reasons behind the practice of consanguinity, is presented in Table 1 and shown in Figure 3. The data is organized region-wise, citing recent and landmark studies where available.

Table 1. Worldwide prevalence of consanguineous marriage.

|

Region/Country |

Prevalence (%) |

Author(s) & Year |

Observations |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Afghanistan |

~46% |

Saify& Saadat (2012) [26] |

Tribal norms, ethnic identity |

|

Pakisthan |

~56% |

Agha (2016) [27] |

Islamic tradition, rural practice |

|

Egypt |

30-35% |

Temtamy and Aglan (2012) [28] |

Family unity, stability |

|

India |

~14% |

Kalam et al. (2024) [10] |

Close consanguineous marriage affects pregnancy wastage less compared to distant consanguineous marriage |

|

Iran |

20–40% |

Rural traditions, Shia Islam acceptance |

|

|

Iraq |

~45% |

Tadmouri et al. (2009) [31] |

War and displacement increase intra-family marriage |

|

Israel (Bedouins) |

~45% |

Jaber et al. (1998) [12] |

Strong kinship ties |

|

Jordan |

~40–50% |

Jaber et al. (1998) [12] |

Cultural tradition, reduced dowry costs |

|

Kwait |

~55% |

Jaber et al. (1998) [12] |

Tradition and dowry costs |

|

Lebanon |

~15–20% |

Barbour & Salameh (2009) [32] |

Declining in urban areas |

|

Morocco |

~20% |

Bittles & Black (2010) [7] |

Rural customs |

|

Pakistan |

50–60% |

Tradition, family integrity, and property consolidation |

|

|

Qatar |

51% |

Bener& Denic (2001) [35] |

Cultural norms, social preferences |

|

Saudi Arabia |

51–58% |

Tribal culture, Islamic legitimacy, wealth retention |

|

|

Sub-Saharan Africa |

<5% (except Sudan) |

Tadmouri et al. (2009) [31] |

Mostly exogamous cultures |

|

Sudan |

40–45% |

Tadmouri et al. (2009) [31] |

Custom, tribal linkages |

|

Syria |

25–30% |

Tadmouri et al. (2009) [31] |

Tribal and sectarian identities |

|

Tunisia |

~20% |

Hamamy (2012) [11] |

Traditional regions |

|

Turkey |

20–25% |

Tuncbilek & Koc (1994) [38] |

Kurdish areas, cultural continuity |

|

UK (Pakistani diaspora) |

38% |

Transnational continuity of tradition |

|

|

United Arab Emirates |

39–50% |

Social cohesion, tribalism |

|

|

USA & Europe |

<1% |

Rare; limited to immigrant communities |

|

|

Yemen |

~40% |

Hamamy (2012) [11] |

Custom, rurality |

5. Anthropological Perspectives on the Origins of Consanguineous Marriage

The inquiry into the origin of consanguineous unions dates back to the prehistoric period [44]. From an anthropological perspective, the prevalence of cousin marriage in many traditional societies can be interpreted as a rational social, economic, and political strategy rather than a random or purely emotional choice. Kinship systems have long been recognized as fundamental to the organization of human societies, and cousin marriage—particularly within the lineage—has often functioned to maintain group cohesion, inheritance, and social trust. One major reason for preferring cousin marriage over affinal (non-kin or distant) unions is its capacity to strengthen kin unity and preserve lineage solidarity. As Fox (1967) observed in Kinship and Marriage, cousin marriage is not an anomaly but a rule-governed institution embedded within broader structures of descent and alliance [3].

In segmentary lineage systems such as those among Arab Bedouins or African pastoralists, patrilateral parallel-cousin marriage (father’s brother’s daughter) ensures that property, authority, and allegiance remain within the patriline, thereby minimizing the fragmentation of wealth and influence [46]. Kin-based unions also help manage risk and reciprocity by promoting marriages within trusted, familiar networks, reducing uncertainty about loyalty and obligations that might arise in affinal alliances [47]. This functioned especially well in stateless or small-scale societies, where kinship provided the primary framework for social regulation and mutual support. Within such settings, cousin marriage reinforced existing kin ties, fostered mutual obligations, and retained bridewealth or dowry within the family that might otherwise be transferred to unrelated groups [23,48]. A recent ethnographic study among Khotta Muslims similarly shows that women often prefer cousin marriages to avoid the insecurity of marrying unfamiliar partners[16].

Ecological anthropology also provides explanatory insights. Ember and Ember (1983) found that cousin marriage is more common in ecologically unpredictable environments, where strong kinship bonds enhance cooperation and resilience [49]. Among endogamous tribal and clan-based groups, reluctance to marry outside the lineage or cultural group often stems from concerns about losing identity, land, or social cohesion [49]. In this sense, cousin marriage acts as a mechanism of cultural continuity, transmitting not only genetic material but also social values, religious identity, and customary rights within a trusted framework [19].

From a bio-cultural standpoint, some anthropologists suggest that mild consanguinity might have offered adaptive advantages in small or isolated populations by stabilizing inherited traits [1]. In contrast, distant or non-kin marriages could introduce uncertainty, dilute resources, and weaken intra-group cooperation. Thus, rather than a deviation from social norms, cousin marriage can be viewed as an adaptive social institution that integrates kin-based economic logic, ecological adaptation, and the reproduction of social order [13,14,44].

6. Evolution of Consanguineous Marriage

The evolution of consanguineous marriage is best understood as part of the broader dynamics of kinship systems, social structure, and cultural logic. Rather than viewing such unions solely through biomedical or legal lenses, anthropologists focus on their socio-cultural functions, symbolic meanings, and economic rationalities across time and space [50,51]. Historically, consanguineous marriages have been practiced in many segmentary lineage societies to maintain the integrity of kin groups, consolidate inheritance, and reinforce endogamous boundaries [52]. These marriages were not simply private choices but were embedded within rules of descent and preferential marriage norms, which varied according to whether a society was organized around patrilineal, matrilineal, or bilateral principles [3]. The anthropological classification of cousin marriages—particularly the distinction between cross-cousin and parallel-cousin marriage—was pioneered by Lewis Henry Morgan (1871), who saw kinship as a universal system that could be compared across societies [5]. Later, Claude Lévi-Strauss (1949) transformed this understanding through his structuralist theory, positing that cross-cousin marriage was central to the alliance theory of kinship, where marriage acts as a system of reciprocal exchange between social groups, thereby ensuring cohesion and cooperation [6]. Fox (1967) argues that cousin marriage is not a random or biologically determined phenomenon, but a culturally regulated practice that evolves in tandem with a society’s rules of descent, property transmission, and authority structures [3]. According to Fox (1967), cross-cousin marriage tends to emerge in societies organized around exchange and alliance, particularly those with matrilineal descent or bilateral kinship systems [3]. In these societies, marriage between cross-cousins helps build alliances and redistribute rights, obligations, and goods between lineages. This form is often seen as promoting exogamy within lineages while maintaining endogamy within the larger community. Fox (1967) noted that consanguineous marriage functions to retain wealth, women, and power within the male line, thereby strengthening lineage cohesion [3]. Fox (1967) emphasizes that the evolution of cousin marriage patterns in any given society reflects broader transformations in social structure, inheritance logic, and political economy [3]. Over time, as societies shift from tribal, segmentary systems to centralized state systems or adopt new religious-legal frameworks, the acceptability and form of cousin marriage also change. Thus, for Fox (1967), cousin marriage evolves not due to genetics or mere tradition, but through its embeddedness in social strategies and cultural logic that adapt to historical and institutional changes [3].

In many Middle Eastern and South Asian societies, however, parallel-cousin marriage—especially father’s brother’s daughter (FBD) marriage—emerged as a preferred pattern, interpreted not in terms of alliance but of agnatic solidarity and patrilineal closure [6,8]. Anthropologists have pointed out that such practices are deeply tied to concerns over property retention, family honour, gendered power dynamics, old-age security, and community solidarity [20,39,53]. With the advent of post-structuralist and feminist anthropological critiques, attention shifted to how consanguineous marriage affects individual agency, particularly among women, who may face social pressures, limited marital autonomy, or blame for genetic outcomes [27,54]. The focus thus expanded from structural functions to lived experiences, subjectivities, and the inter-sectionality of kinship, gender, and power. In contemporary anthropology, the study of consanguineous marriage is situated at the intersection of tradition and modernity, recognizing that such marriages persist not out of ignorance but often as rational, culturally embedded choices, shaped by evolving social, economic, and political conditions [8,15,16].

Lewis Henry Morgan (1877), in his “Ancient Society”, outlined an evolutionary scheme of the family, beginning with the consanguineous family, in which sexual relations were permitted among cousins within the same kin group [4,5]. This was followed by the punaluan family, in which brothers of one group collectively married sisters of another, with sibling incest prohibited, thereby initiating exogamy. The next stage was the syndyasmian family, characterized by relatively stable pairings between a man and a woman, though the union could be easily dissolved. Finally, Morgan identified the monogamous family as the most advanced form, marked by exclusive unions between one man and one woman, reinforced by inheritance and property rights [4,5].

Consanguineous→ punaluan→ syndyasmian → monogamous

Later on, Engels, in The Origin of the Family, Private Property, and the State (1884), adopted Morgan’s stages but reinterpreted them through a materialist perspective [55]. He accepted the idea of the consanguineous family as the earliest stage, illustrating primitive promiscuity and the absence of incest taboos. However, Engels linked the evolution of family forms directly to changes in modes of production, property ownership, and social inequality. For him, the rise of monogamy was not merely a cultural progression but a consequence of the emergence of private property and patriarchal control, which he famously described as the “world-historic defeat of the female sex”. In this way, Engels (1884) expanded Morgan’s anthropological framework into a broader theory of social and economic transformation [55].

7. Dimensions of Consanguineous Marriage

Consanguineous marriage has held deep social, economic, and symbolic significance throughout human history. From an anthropological standpoint, such marriages are not merely familial choices but culturally structured institutions embedded in broader kinship, alliance, and inheritance systems.

7.1. Historical Trend and Cultural Rationales

Consanguineous marriage has a long-standing historical presence across diverse cultures and civilizations. Far from being a marginal or pathological phenomenon, it has historically functioned as a culturally sanctioned and strategically utilized institution. In ancient civilizations such as Pharaonic Egypt, Mesopotamia, and Zoroastrian Persia, consanguineous marriages—including even sibling unions among elites—were practiced to preserve dynastic purity, consolidate power, and maintain control over royal or priestly lineage [9,23]. Among Muslim societies, cousin marriage gained legal and religious legitimacy based on Qur’anic sanction, contributing to its widespread practice in the Middle East, North Africa, and South Asia [21,56]. The cultural logic behind these marriages lies in their utility for preserving wealth and land within the extended family, strengthening social cohesion, and reinforcing trust between kin. In South Asian societies, especially among Muslims and certain Hindu castes of South India, cousin marriage has historically allowed families to uphold notions of izzat (honour), reduce the economic burden of dowry or bridewealth, and ensure that daughters marry into known, trusted households [16,57]. Anthropological research demonstrates that cousin marriage is not random or biologically motivated, but rather part of a structured system of alliance and inheritance management [3]. Parallel-cousin marriage is particularly prevalent in patrilineal societies, where it ensures the retention of property within the male line, while cross-cousin marriage is common in systems of reciprocal alliance, such as those found in Dravidian kinship systems [18]. Thus, the historical prevalence of consanguineous marriage reflects adaptive responses to social and ecological conditions, deeply rooted in local systems of kinship, descent, and cultural value.

7.2. Theoretical Perspective

Fox (1967), in his Kinship and Marriage, argued that cousin marriage is not anomalous but a “systematic solution” to social needs like alliance formation, alloparenting, and inheritance regulation [3]. He distinguished between patrilateral parallel-cousin marriage (common in Arab tribes) and matrilateral cross-cousin marriage (typical in Dravidian and Australian Aboriginal societies), each serving different alliance and descent functions. Anthropologists have examined consanguineous marriage not merely as a biological arrangement but as a deeply embedded cultural practice shaped by kinship systems, social obligations, and economic strategies. Structuralism and Alliance Theory, developed by Claude Lévi-Strauss (1949), conceptualize cousin marriage—particularly matrilateral cross-cousin marriage—as a system of reciprocal exchanges that sustains alliances and solidarity between kin groups [6]. Descent Theory, as articulated by Radcliffe-Brown and Evans-Pritchard, emphasizes patrilateral parallel-cousin marriage as a means to preserve lineage, property, and identity, particularly in patrilineal societies such as those in the Arab world [54,58]. Transactional and Economic Interpretations, advanced by Jack Goody (1983) and Barth (1960), explain cousin marriage as a strategy to minimize bridewealth, retain land and resources within families, and control women’s mobility [16,47]. Symbolic and Cultural Interpretations, notably by David Schneider (1984), reframe kinship—including consanguineous marriage—as a culturally constructed system in which notions of relatedness, incest, and marriage ability vary across societies [59]. Feminist and Postcolonial Critiques highlight the gendered dimensions of cousin marriage, illustrating how such unions may simultaneously reinforce patriarchal structures and offer familial security for women [27,60]. Collectively, these theories interpret consanguineous marriage as an anthropological mechanism for social reproduction and alliance (Structuralism, Alliance Theory), a means to secure lineage and inheritance (Descent Theory), a strategic response to economic and symbolic needs (Transactional/Economic and Symbolic Theories), and a contested site of gendered negotiation and cultural agency (Feminist and Postcolonial Approaches) [6,27,60].

7.3. Colonial Encounters and Modernity in Consanguineous Marriages

Colonialism played a critical role in reshaping discourses and practices around consanguineous marriage, often framing them through lenses of pathology, backwardness, or religious tradition. During the British colonial administration in South Asia, marriage practices such as cousin marriage—common among Muslims and certain Hindu castes—were scrutinized under the influence of Western Christian ideals of the nuclear family and exogamy. British officials and missionaries viewed endogamous and cousin marriages as markers of social stagnation and impediments to progress, linking them to presumed racial degeneration and social disorder [61]. This moral and racial framing shaped colonial legal interventions and census classifications, reinforcing binaries between ‘modern’ Western marriage and ‘traditional’ native kinship structures. For example, debates surrounding Muslim personal law in colonial India highlighted cousin marriage as a point of contention between Islamic jurisprudence and colonial modernity [62]. Similarly, in the Middle East, colonial ethnographers and health officials interpreted high rates of consanguinity through a eugenic lens, often ignoring the social logic behind these practices [63]. Postcolonial anthropologists have since challenged such essentialist and Eurocentric views, demonstrating that consanguineous marriage practices are not vestiges of backwardness but adaptive strategies embedded in systems of kinship, inheritance, and gendered security [27]. Moreover, the encounter with modernity—through education, migration, and state health interventions—has led to changing perceptions and negotiations of cousin marriage within communities, especially among youth who increasingly question the practice while balancing familial obligations and personal autonomy [64]. Thus, colonial and modern state discourses did not erase consanguineous marriage but reconfigured its meanings, often reinforcing patriarchal control while opening spaces for re-interpretation in postcolonial societies. In recent years, in the aftermath of the post-colonial era and under the influence of modernity, factors such as educational advancement, media exposure, and growing awareness of the harmful consequences of consanguineous marriages appear to have contributed to their decline [65,66,67].

8. Drivers of Consanguineous Marriage

Anthropologists and social scientists have long examined the persistence of consanguineous marriage patterns, highlighting a complex interplay of social, economic, religious, and cultural factors that sustain the practice despite modernization and changing demographic trends [17,33,68,69].

8.1. Socio-Cultural and Kinship Factors

Anthropologically, systems of kinship and lineage organization significantly influence the persistence of consanguineous marriages. Such unions, particularly between cousins, often function as strategies to reinforce familial bonds and uphold clan or lineage unity [16,20]. In many societies where kinship determines social standing and access to resources, marrying within the family helps sustain internal cohesion and strengthens mutual trust among relatives [3,19]. Furthermore, endogamous practices act as cultural mechanisms that preserve social identity and maintain boundaries, especially within tribal and caste-oriented communities [17,56].

8.2. Economic and Property Considerations

Economic rationales are among the strongest drivers of consanguineous marriage. Marrying within the family allows for the consolidation of land, property, and wealth, minimizing fragmentation through inheritance [16,33]. In agrarian and pastoral economies, maintaining property within the patrilineage is considered vital to sustaining household economic stability. Furthermore, such marriages reduce dowry or bride price expenses and enhance the perceived economic security of women within the familiar kin network [16,30,37,69,70,71,72].

8.3. Religious and Moral Dimensions

Religious beliefs often reinforce the practice of consanguinity by providing cultural legitimacy. In Islamic societies, for example, cousin marriages are not only permissible but often valorized as a morally sound and socially acceptable form of union [17]. Religious sanction provides a framework for preserving lineage purity (nasab) and maintaining moral control within the family. Similarly, among Christian and Hindu groups in certain regions, cousin marriage is influenced more by local customs and interpretations than by strict doctrinal prohibitions [21,73].

8.4. Social Trust, Compatibility, and Marital Stability

Another key driver concerns perceived trust and compatibility among kin. Families often prefer marrying known relatives over outsiders to ensure social security, reduce marital uncertainty, and enhance compatibility through shared upbringing, values, and lifestyle [7,17,30]. Studies in Pakistan, Iran, and India indicate that cousin marriages are often perceived as more stable and emotionally secure, offering stronger support networks for couples [34].

8.5. Gender and Control Dimensions

Consanguineous marriages can also be seen as mechanisms of patriarchal control over women’s mobility and sexuality. Marrying within the kin group allows male elders to monitor and maintain authority over female members, preventing “outsider” alliances and potential loss of property or honor [16,20,63]. This dimension intersects with the broader socio-cultural ideals of family honor (izzat) and purity, especially in patriarchal rural societies.

8.6. Modernization and Migration

Although modernization and education have altered marriage patterns in many contexts, consanguinity persists even among modern migrant populations in Western countries [48,74]. For diaspora communities, cousin marriage often functions as a strategy to maintain transnational kin networks, cultural identity, and social cohesion [39,53,67,75].

8.7. Psychological and Emotional Familiarity

Emotional security is an important factor influencing partner selection in societies where kinship relations are strong. Individuals who marry within their extended family often share early life experiences, cultural norms, and similar social environments, which help build mutual understanding and trust. Such familiarity reduces the apprehension or gamophobia—the fear of marrying a stranger—that may accompany unions with unrelated partners. For women in conservative or patriarchal settings, psychological familiarity with in-laws also eases the process of post-marital adjustment and strengthens feelings of safety and belonging [16,17,76].

8.8. Fear of Cultural Dilution

In certain societies, marrying beyond the kin group is perceived as a potential risk to the preservation of cultural identity and ancestral lineage. Although lacking a scientific foundation, this perception reflects a symbolic desire to protect the integrity of the family’s “bloodline” and sustain cultural or ethnic uniformity across generations [39,40].

9. Effects of Consanguineous Marriage

9.1. Beneficiary Effects of Consanguineous Marriage

Despite growing global concerns about the associated genetic risks, such marriages persist for several socio-cultural, economic, and ecological reasons. Anthropological, sociological, and biomedical studies have outlined various benefits of these marital arrangements, contextualized within particular kinship systems and societal structures [17,68].

9.1.1. Strengthening Family and Kinship Ties

One of the most cited advantages of consanguineous marriages is the reinforcement of kinship bonds and familial solidarity. In societies where lineage, clan, or tribal cohesion is central to social organization, marrying within the extended family serves as a mechanism to maintain intergenerational trust and cooperation [1,3,16,17]. This practice often ensures the continuity of mutual obligations, such as caregiving, inheritance, and dispute mediation, within the same kin network.

9.1.2. Economic and Property Consolidation

Consanguineous marriages often help retain property, land, and wealth within the extended family or lineage. This is particularly evident in patrilineal societies where land fragmentation due to dowry or inheritance transfers can be averted through cousin marriages [19,70,71,72,73]. Marrying within the family reduces the economic uncertainties associated with external alliances, safeguarding familial assets across generations.

9.1.3. Marital Stability and Social Compatibility

Studies have suggested that consanguineous marriages exhibit lower divorce rates and greater marital stability than non-consanguineous unions [16,68,77,78]. This is attributed to prior familiarity between the spouses and their families, resulting in reduced cultural and behavioral conflict. Pre-existing familial trust and reduced dowry demands also contribute to smoother marital negotiations and post-marital support.

9.1.4. Easier Spousal Selection and Reduced Search Costs

In tightly knit communities, consanguineous marriage simplifies the process of spouse selection, reducing the burden of searching for suitable partners across distant social networks. This can be especially significant in regions with limited access to education and mobility, where kin-based matchmaking reduces logistical, financial, and cultural complications [11,16,17,79].

9.1.5. Support During Crisis and Caregiving

Cousin marriages offer practical advantages in caregiving and support during health, financial, or social crises. Having extended family members as in-laws facilitates cooperation in child-rearing, elder care, and resource sharing [7,10,16,69]. Such networks are particularly valuable in contexts where institutional support is weak or absent.

9.1.6. Reinforcement of Social Identity and Endogamy

In many caste- or tribe-based societies, consanguineous marriage reinforces social identity and preserves community endogamy. This helps maintain ritual purity, social status, and the continuity of cultural practices, especially among marginalized or minority populations who seek to resist assimilation [16,79].

9.1.7. Religious and Cultural Legitimacy

In Islam, for example, consanguineous marriage is religiously permissible, and in many Islamic societies, first cousin marriage is viewed favorably both culturally and scripturally [16,73,75]. Religious sanction often reinforces the social acceptability and perceived moral value of such unions.

9.1.8. Evolutionary and Behavioral Ecology Explanations

From a behavioral ecological perspective, some scholars argue that consanguineous marriages may confer inclusive fitness benefits by enhancing kin cooperation, trust, and resource pooling. Robin Fox (1967) proposed that such marriages could be evolutionarily advantageous in stable, endogamous communities by optimizing reproductive and economic success under particular environmental constraints [3,5,44,80].

9.2. Non-Beneficiary Effect of Consanguineous Marriage

Despite its cultural and social embeddedness in many parts of the world, consanguineous marriage is associated with a range of biological, social, and demographic disadvantages, as widely reported in biomedical, anthropological, and demographic literature [10,81,82,83].

9.2.1. Hereditary Risk

From a biomedical perspective, consanguinity increases the probability of homozygosity at recessive gene loci, elevating the risk of autosomal recessive disorders. Numerous studies have documented significantly higher incidences of congenital malformations, perinatal mortality, intellectual disability, and inherited metabolic disorders among offspring of consanguineous unions [10,81,82,83]. For instance, research in the Middle East and South Asia—regions with high prevalence of first-cousin marriages—shows that these unions are strongly correlated with increased rates of neonatal mortality and morbidity [83]. The magnitude of genetic risk is particularly elevated in regions where consanguinity is practiced over multiple generations, leading to an accumulation of deleterious alleles in family gene pools [1,7].

9.2.2. Burden on Healthcare Systems

From a demographic and public health standpoint, consanguinity can impose significant burdens on healthcare systems. Higher rates of disability-adjusted life years (DALYs), increased pediatric care costs, and the need for long-term rehabilitation services are noted in populations with high consanguinity rates [11,31,84]. Additionally, in some low-income and resource-constrained settings, the lack of adequate genetic counseling exacerbates the risks, leading to the persistence of hereditary conditions and contributing to a cycle of poverty and poor health outcomes [12].

9.2.3. Constrain on Women’s Autonomy

Socially, the preference for intra-familial unions may constrain women’s autonomy and freedom of marital choice, reinforcing patriarchal norms and kin-based control mechanisms [27,85,86,87]. In some contexts, girls may be married off at an early age within kin networks, potentially violating their rights and increasing their vulnerability to gender-based violence or social isolation. Moreover, while kin marriages may strengthen internal clan cohesion, they may also foster exclusivity, inhibit social mobility, and contribute to ethnic or caste endogamy, perpetuating social divisions and limiting broader societal integration [9,16].

9.2.4. Intra-Familial Conflict

Anthropological perspectives further reveal that while consanguinity is often rationalized in terms of kin loyalty and resource consolidation, it may paradoxically generate intra-familial conflict. Issues surrounding inheritance, resource competition, and intergenerational obligations may intensify in closed kin groups, particularly when economic inequality exists among close relatives [3,21,69]. This is particularly true in patrilineal societies where property is often retained within agnatic lines, sometimes at the cost of individual well-being.

9.2.5. Evolutionary Trade-Offs in Consanguineous Marriages

From an evolutionary perspective, several behavioral ecologists have argued that consanguineous marriages may confer short-term inclusive fitness advantages, particularly by reinforcing kin solidarity and cooperative behavior among genetically related individuals [3]. These unions can enhance social cohesion, facilitate familial resource pooling, and reduce partner-search costs within tightly knit communities. However, such perceived benefits are often counterbalanced by the long-term evolutionary consequences of reduced genetic heterogeneity. Specifically, consanguinity increases the likelihood of homozygosity for deleterious alleles, thereby elevating the genetic load within a population [7]. Over successive generations, this accumulation of harmful recessive mutations may result in a decline in overall population fitness, especially in small or endogamous groups where genetic diversity is already limited [7,44,72]. While consanguineous marriages may offer certain social and reproductive advantages, they also entail significant evolutionary risks, particularly in terms of genetic health. The most prominent risk is increased homozygosity, which increases the likelihood that offspring will inherit autosomal recessive disorders such as thalassemia, cystic fibrosis, and various congenital anomalies [7,72]. This is due to the fact that relatives are more likely to carry the same deleterious alleles, making their union more genetically hazardous. Moreover, inbreeding can lead to inbreeding depression, a reduction in biological fitness that may manifest as increased infant mortality, reduced cognitive development, impaired immune function, and overall lower survival rates of offspring [72]. From an evolutionary standpoint, such trade-offs reduce the long-term adaptability of populations by limiting genetic diversity, which is crucial for coping with environmental changes and disease pressures. These risks become especially pronounced in small, endogamous communities or isolated populations where genetic drift and founder effects amplify inherited disorders. Hence, while consanguinity may serve short-term social or reproductive goals, it can undermine population health and resilience over generations.

9.2.6. Increases Pregnancy Wastage

Multiple studies across South Asia and the Middle East have demonstrated a significant association between consanguineous unions and increased risks of adverse pregnancy outcomes and early-life mortality [10,75,81]. Of particular note, Kalam et al. (2024)—analyzing pooled data from India’s National Family Health Surveys 4 (2015–2016) and 5 (2019–2021)—employed logistic and Cox proportional hazards regression models to assess the impact of close (first-cousin) and distant consanguinity on spontaneous abortion, stillbirth, neonatal, post-neonatal, and under-five mortality [10]. Their findings indicated a statistically significant elevation in the risk of spontaneous abortion (for both close and distant consanguinity) and neonatal mortality (distant consanguinity) when compared to non-consanguineous marriages. Notably, no significant association was observed for child mortality beyond infancy, suggesting that broader socioeconomic developments and improved healthcare services may buffer later survival risks. Earlier research has similarly documented elevated infant and perinatal mortality among offspring of consanguineous unions [10]. For instance, Hussain and Bittles (1998) found that in Pakistan, child mortality was approximately 1.5 times higher among first-cousin couples relative to non-consanguineous couples [34]. Comparable findings emerge from Middle Eastern populations. El-Hazmi etal. (1995) reported notably heightened neonatal and infant mortality in Saudi Arabia, and Tadmouri etal. (2009) emphasized similar risk elevations across multiple Arab countries [31,36]. The biological mechanism underlying this increased risk is the greater likelihood of homozygosity for recessive deleterious alleles in the offspring of related parents, which can manifest as congenital anomalies, prematurity, low birth weight, and reduced vitality immediately after birth [7,43]. These genetic vulnerabilities are most likely expressed during the neonatal and early infant periods, aligning with the elevated risks observed in epidemiological studies.

9.2.7. Consanguinity and Mental Health Illness

Consanguineous marriage has been linked to an elevated risk of certain mental health disorders, particularly those with a strong genetic component. The increased homozygosity resulting from consanguinity raises the likelihood of recessive genetic mutations being expressed, some of which may contribute to neuro-developmental and psychiatric disorders such as intellectual disability, autism spectrum disorders (ASD), epilepsy, and schizophrenia [7,88]. Research in South Asia and the Middle East—regions with high rates of consanguineous marriage—has reported a greater prevalence of cognitive impairment and learning disabilities among children born to closely related parents [83]. Additionally, studies have shown a higher incidence of major depressive disorder and bipolar disorder in certain populations practicing consanguinity. However, the relationship here is less direct and likely influenced by socio-environmental factors such as stigma, isolation, and lack of access to mental health services [33]. While not all mental illnesses are strongly heritable, consanguinity may increase the risk where multiple recessive genes interact or where genetic vulnerability combines with environmental stressors. Thus, consanguineous unions require careful genetic counseling to mitigate mental health risks, particularly in regions where such marriages are culturally preferred.

10. Consanguinity at the Intersection of Religion, Law, and Identity Politics

Consanguineous marriage is not merely a reproductive or familial choice; it is deeply embedded within religious doctrines, legal structures, and the socio-political constructions of identity. In many Islamic societies, cousin marriage is explicitly permitted and even encouraged under religious law. The Qur’an allows such unions (Surah An-Nisa 4:23–24), and the Prophet Muhammad’s marriage to his cousin Zaynab bint Jahsh is often cited as a religious precedent. Consequently, consanguineous unions are culturally and theologically framed as legitimate, fostering social cohesion, kin solidarity, and preservation of familial resources [73,78]. Similarly, among South Asian Hindus, although Sanskritic traditions (e.g., Dharmashastra) generally discourage close-kin marriages, regional practices vary. In northern India, such unions are largely proscribed under clan exogamy norms, while in southern India, cross-cousin and uncle-niece marriages are culturally preferred, aligning with the Dravidian kinship system and the logic of returning daughters and dowry within the natal lineage [18]. These religiously or customarily sanctioned norms, however, often come into tension with secular legal codes. For instance, in India, the Hindu Marriage Act (1955) prohibits marriage within defined degrees of consanguinity unless allowed by custom, while Muslim Personal Law permits cousin marriages, creating a legal pluralism rooted in religious identity [89,90,91].

This differential legality reveals how consanguinity intersects with identity politics, especially in pluralistic or post-colonial societies. Among diasporic communities—such as British Pakistanis—cousin marriage functions as a marker of cultural preservation, transnational belonging, and resistance against assimilation. Yet, it has also been subjected to racialized public health discourses in Western societies, where cousin marriage is often portrayed as a cause of congenital disorders, thus becoming a site of bio-political governance. These narratives tend to overlook structural determinants such as poverty, lack of genetic counseling, and healthcare inequality. As a result, consanguineous marriage becomes politicized—portrayed either as a backward cultural practice or defended as a human right within frameworks of religious freedom and cultural autonomy. This tension highlights the complexity of regulating intimacy in multicultural states, where laws, religious traditions, and political narratives converge. Ultimately, consanguineous marriage should be viewed not solely through biomedical or legal lenses but within a broader anthropological framework that situates it at the intersection of belief, law, kinship, and identity.

11. Changing Patterns of Consanguineous Marriage

While consanguineous marriage remains culturally normative and strategically valued in many parts of the Global South, including South Asia, the Middle East, and North Africa, migration has introduced significant shifts in how such practices are sustained or transformed in diaspora settings. Among first-generation immigrants, particularly from Pakistan, Bangladesh, or Arab countries, cousin marriage continues to be practiced as a way of preserving kinship ties, ensuring trust within the family, and consolidating transnational resources such as remittances and migration sponsorship, and the demographic transition period [53,65,67,92]. However, second-generation immigrants in host countries like the United Kingdom, Canada, and the Gulf States increasingly renegotiate the terms of consanguinity, navigating between inherited familial expectations and the values of individual autonomy, education, and romantic choice that are emphasized in host cultures [93].

Ethnographic research among British Pakistani communities, for example, illustrates the increasing ambivalence of second-generation youth toward cousin marriage. While some still consent to such unions to maintain familial loyalty or to meet parental expectations, others resist or delay marriage altogether, citing concerns over genetic risk, lack of personal compatibility, and generational dissonance [53,94]. This resistance often leads to intergenerational tensions, where elders perceive the younger generation’s reluctance as a threat to family honor and cultural continuity, while younger individuals view arranged cousin marriage as restrictive or outdated [95]. In Gulf countries, where South Asian and Arab expatriates form large transnational communities, employment-linked migration and temporary visa statuses often disrupt kinship continuity, leading to delayed marriages or shifts toward more individualized spousal selection patterns among younger migrants [74].

Moreover, the digital mediation of matchmaking has significantly altered how cousin marriages are arranged and perceived. Online platforms and matrimonial websites increasingly act as sites where tradition and modernity converge. While some families use digital tools to extend traditional matchmaking across borders (e.g., between UK-based youth and cousins in Pakistan or Bangladesh), others find these platforms empowering for youth seeking partners outside kinship lines [71,75]. Education and occupational mobility—particularly for women—also play a critical role in shaping new marital preferences. For instance, highly educated second-generation women often reject consanguineous unions in favor of partners who match their educational and professional achievements, leading to shifts in intra-community marriage norms and the emergence of negotiated or semi-arranged marriages [73].

In India, consanguineous marriage has been showing a declining trend, as demonstrated by earlier studies [53,67,96]. Based on a large-scale, pan-India dataset spanning more than two decades, the study revealed that factors such as modernity, the expansion of women’s education, and greater decision-making power among women have significantly contributed to this decline. At the regional level, Kalam and Ghosh (2025) also observed a generational reduction in consanguineous marriages among the Khotta Muslim community of West Bengal [66]. This pattern was influenced by multiple factors, including modernization, educational advancement, and increasing interactions with out-group communities.

Despite these changes, the pattern is not uniformly one of rejection. Some studies report reconfigurations of cousin marriage rather than its wholesale decline. In Canadian and Scandinavian Pakistani communities, for example, young people may strategically accept cousin marriages to fulfill immigration sponsorship roles or to retain inheritance rights in their country of origin, demonstrating a pragmatic, rather than purely emotional or ideological, engagement with kinship norms [75]. This ambivalence reflects a hybrid identity space, where cultural continuity is maintained but through adaptive practices that align with the realities of life in a multicultural society.

The practice of consanguineous marriage among diaspora communities is not static but shaped by dynamic negotiations between tradition and modernity, mediated by structural conditions such as migration policy, transnational family obligations, education, and digital culture. Recognizing these changes requires moving beyond a static or risk-centered view of cousin marriage to one that situates it within broader questions of transnational kinship, intergenerational agency, and diasporic identity.

12. Child and Adolescent Rights in the Context of Consanguineous Marriage

While several manuscripts thoughtfully explore women’s autonomy within the framework of consanguineous marriage, they remain silent on the critical issue of child and adolescent rights, particularly in relation to early and arranged marriages. This omission is significant given that consanguineous unions are often interwoven with early marriage practices, especially in patriarchal and resource-constrained settings where kinship structures prioritize familial control over individual choice. In such contexts, cousin marriages are frequently arranged during adolescence or even childhood, reflecting broader gendered norms that limit the autonomy and agency of young girls [89,90,91].

From a human rights perspective, early consanguineous marriage constitutes a violation of a child’s right to free and full consent, bodily autonomy, and access to education and health. International conventions such as the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) and the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) have repeatedly highlighted the adverse consequences of child marriage, including increased risks of domestic violence, maternal mortality, early school dropout, and mental health disorders [87,89,90]. When these early unions occur within consanguineous frameworks, the risks are compounded by genetic vulnerabilities and social isolation, particularly in contexts where young brides are transferred from one household to another without adequate support networks.

Moreover, consanguineous child marriages often take place in environments where legal enforcement of age at marriage is weak, and where cultural or religious justifications override statutory protections. In South Asia, the Middle East, and parts of North and East Africa—regions where both consanguinity and child marriage are prevalent—policy efforts have been inconsistent, frequently undermined by customary laws and patriarchal bargaining systems [89,90]. These dynamics not only violate international legal standards but also perpetuate intergenerational cycles of gender inequality and child rights deprivation.

13. Comparative Ethnographic Voices on Consanguinity

While consanguineous marriage is often addressed through demographic, biomedical, and policy-oriented lenses, its everyday enactment is deeply embedded in culturally specific, emotionally charged, and socially situated contexts. Integrating comparative ethnographic voices provides a richer understanding of how such marriages are not only institutional arrangements but also arenas where gender, generation, and kinship norms are contested, negotiated, or reaffirmed. Drawing from ethnographic studies in Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Kerala (India), and diaspora communities, we see both continuities and transformations in how consanguineous marriage is experienced and rationalized in everyday life.

In rural and urban Pakistan, for example, cousin marriage is deeply normalized and widely practiced, often underpinned by logics of family trust, resource consolidation, and lineage loyalty. In her fieldwork in Pakistan and among British Pakistani families, Shaw (2001) notes that women often describe cousin marriage as a mechanism for emotional safety, since marrying within the family is believed to provide greater long-term security and reduce the risks of abuse or neglect from unfamiliar in-laws [39]. However, Shaw (2009) also captures the ambivalence and resistance expressed by younger women, particularly in urban contexts, where educational exposure, media, and peer influence encourage them to question the inevitability of cousin marriage, leading to subtle but significant intergenerational negotiations [39].

Hussain (1999) observed [78] that consanguineous marriage has connections with religion, while his participants remarked as:

“The custom of consanguineous marriage has very little to do with sunnat. It is just a time-honoured tradition”.

Similarly, a Balochi respondent in his study stated:

“I do not think people go for consanguineous marriage because it is a sunnat, but they do it mainly because they want to enhance their family relationships”.

Similarly, his participants have other views regarding economic aspects of consanguineous marriage, such as participants expressed their concern:

“In our family, there is no strong tradition of big jahez. However, if one opts for non-consanguineous marriage, then the size of the jahez is larger to ensure that the girl does not have to listen to any taunts…”

In Saudi Arabia, where patrilineal kinship and tribal identity are central to social structure, parallel-cousin marriage (father’s brother’s daughter) is considered the ideal match in many regions. Al-Krenawi and Graham (2005) document how in Bedouin communities, cousin marriage is not only culturally valorized but also enforced through tribal expectations, and women often have limited power to refuse such unions [95]. Yet, the researchers also note increasing contestation among younger Saudi women, particularly in cities, who view such marriages as constraining and seek greater autonomy through education and delayed marriage. These voices reveal an ongoing tension between collectivist familial norms and emerging individual aspirations in post-oil, globalizing Saudi society.

In a study among Emirati women [97], Bureun and Gordon (2020) analyses the reasons for marrying cousins, and the participants stated:

“I followed the advice of my family”,

Another said

“I married consanguineously because of my family, I was 16, and all our family married like this, there was no other way [of marriage], my parents wanted me to marry him, also my mother wanted him, so I agreed… I took the advice of my parents because they knew best”.

In the Indian state of Kerala, particularly among Muslim and Christian matrilineal and bilateral communities, consanguineous marriage patterns differ sharply by caste, religion, and region. While Hindu communities largely follow gotra exogamy, many Muslim communities in northern Kerala prefer cross-cousin and uncle-niece marriages. Osella and Osella (2000), in their ethnographic work among Muslims in Kozhikode, reveal how such unions are motivated not merely by custom but also by economic strategies—especially when property or dowry negotiations are involved [74]. Here, consanguineous marriage serves as a pragmatic solution to preserve dowry investments within the extended family, demonstrating how kinship is tightly interwoven with financial rationalities. However, the Osella and Osella (2000) also note increasing anxiety among some younger Keralites about genetic risks and compatibility, reflecting a growing exposure to biomedical discourse and public health campaigns [74].

Kalam and Roy (2015) also found certain voices regarding consanguineous marriage and how it impinges on family relations. The participants in Kalam and Roy’s (2015) study focused more on old age security as a reason behind consanguineous marriage [98]. One such participant stated:

“I got my son married to my brother’s daughter. My brother and I took such a decision so that our children can stay in the same family and could look at us when we grow old”.

Kalam and Ghosh (2025) also found declining trends in consanguineous marriages and several reasons behind the decline, starting from changing decision-making power, educational upliftment, changing marriage payment, and family relations [53]. Some of their participants stated:

“My father sent me to Kolkata to pursue higher education. Living away from my family members and simultaneously finding the company of a new set of peers in the hostel and college, my orientation towards life changed. I created a new identity of my own, which was unacceptable to my family members”.

14. Digital and Technological Mediation in Consanguineous Marriage Practices

The role of digital technology in reshaping consanguineous marriage practices is a rapidly emerging yet underexplored domain within kinship and anthropological scholarship. As cousin marriages remain prevalent across South Asian, Middle Eastern, and North African societies—and their respective diasporas—technological mediation is increasingly influencing how such unions are arranged, perceived, and negotiated, particularly among younger generations. Online matrimonial platforms, social media, mobile matchmaking apps, and genetic screening technologies have collectively begun to transform the logics of kinship, mate selection, and reproductive risk management, thus challenging the assumed continuity of traditional consanguineous marriage practices.

In many communities, especially among British Pakistanis, Canadian South Asians, and Gulf-based expatriates, matrimonial websites and social media have extended the scope and reach of kin-based matchmaking. These platforms often reaffirm consanguinity by facilitating connections within extended kin networks, especially across borders, thus enabling the persistence of transnational cousin marriages [73,92,99]. For example, matrimonial websites such as Shaadi.com or Muslima.com offer customized filters that allow families to search for potential spouses based on caste, religious sect, and even family lineage, subtly reinforcing kin-endogamy. Simultaneously, such platforms are used by second-generation youth to exercise greater autonomy in spouse selection, often negotiating familial expectations with individual preferences [53].

At the same time, digital literacy and access to biomedical information, including online resources about genetic risks, are beginning to reshape youth perceptions of cousin marriage. Studies have shown that younger individuals, especially women, are increasingly aware of the hereditary health risks associated with consanguinity, leading to greater hesitance or conditional acceptance of cousin unions [7,100,101]. In countries like Saudi Arabia and the UAE, state-supported premarital genetic screening programs—some even mandatory—have introduced a new layer of biomedical governance that intersects with traditional kinship expectations [101,102]. These initiatives often utilize mobile apps and web-based portals to deliver screening results and marriage advisories, offering a technological form of risk regulation that can influence marital decisions [101,102,103,104,105]. Moreover, the rise of genetic counseling services and mobile genetic testing kits has contributed to increasing genetic literacy among educated urban youth, who now confront kinship decisions not only through cultural logics but also biomedical ones. While many families continue to value cousin marriage for reasons of trust, property, and social cohesion, growing awareness of autosomal recessive risks and carrier status is generating a generational shift, wherein consanguineous unions are either selectively practiced or coupled with biomedical interventions like carrier testing and pre-implantation genetic diagnosis [11,101,102,103,104].

Despite these trends, technological mediation does not uniformly undermine consanguineous marriage. Rather, it facilitates a hybrid model in which tradition and modernity are co-constituted. Digital platforms allow for a strategic recombination of cultural values and individual choice, and biomedical technologies are selectively embraced by families to mitigate perceived genetic burden while maintaining kinship ideals. Technology is not simply a disruptive force but also a tool of adaptive continuity, allowing consanguineous practices to persist in reformulated, context-specific ways.

15. Policy Implications and Public Health Interventions in Consanguineous Marriage

While the biomedical risks associated with consanguineous marriage—such as increased prevalence of autosomal recessive disorders, congenital anomalies, and intellectual disabilities—are well documented [7,11,103], these risks are not addressed uniformly within health systems or policy frameworks across the globe. In regions where consanguinity is prevalent, such as the Middle East, North Africa, South Asia, and communities in Europe and North America, the policy landscape remains uneven, shaped by a combination of religious norms, legal structures, public health priorities, and cultural politics. Effective interventions in this context require culturally sensitive, interdisciplinary, and community-engaged approaches, particularly those that bridge the gap between anthropological insight and public health practice.

Several countries with high rates of consanguineous marriage have introduced premarital genetic counseling and screening programs as part of public health initiatives. For instance, Iran has established a nationwide premarital screening policy that mandates genetic counseling for couples planning to marry, particularly those in consanguineous unions. This policy, grounded in religious legitimacy and delivered through culturally attuned health infrastructure, has shown some success in improving genetic literacy and reducing the incidence of thalassemia and other hereditary conditions [103]. Similarly, Pakistan, despite facing infrastructural challenges, has implemented targeted screening and public education programs through non-governmental organizations and selective regional interventions [103,104]. These efforts, while limited in reach, signal an acknowledgment of the genetic risks associated with cousin marriage and a move toward preventive care.

In the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries—including Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and the United Arab Emirates—state-sponsored premarital screening for hemoglobinopathies and other recessive disorders has been made mandatory. These programs often integrate digital health tools, mobile applications, and national registries, and provide certificates required for legal marriage registration [102,103]. However, while medically effective, such programs can sometimes lack cultural nuance. Studies have noted that screening results may be ignored or overridden in favor of familial or tribal expectations, suggesting that biomedical knowledge alone does not dictate marital choices in contexts where kinship is highly valued [16].

From a policy standpoint, several key challenges persist. First, many countries, such as developing and underdeveloped, lack comprehensive legal frameworks that ensure informed consent, protect privacy, and provide non-directive counseling in genetic testing—especially for women and adolescents, whose reproductive choices may be constrained by patriarchal kinship systems. Second, public health messaging around consanguinity often fails to address cultural beliefs and social incentives, and may inadvertently stigmatize communities rather than engage them in constructive dialogue [11,16]. Third, there is limited collaboration between biomedical practitioners, anthropologists, and community leaders, which hampers the development of effective, culturally competent outreach.

Thus, there is an urgent need for anthropologists and public health professionals to collaborate in designing interventions that are contextually grounded and ethically responsible. Anthropologists can provide insights into local kinship systems, marriage norms, and decision-making hierarchies, enabling public health initiatives to be better tailored to community realities. For instance, community-based participatory research (CBPR) and ethnographic models that involve elders, religious leaders, and women’s groups in dialogue around genetic risk and reproductive health can enhance acceptance and effectiveness. In diaspora contexts, such as among British Pakistanis, interventions that combine peer education, narrative storytelling, and digital outreach have been more successful than top-down biomedical messaging alone [100]. Policy responses to consanguineous marriage must strike a balance between public health imperatives and cultural sensitivity, recognizing that kinship choices are embedded in social, economic, and emotional logics. Rather than seeking to eliminate the practice, interventions should aim to inform, support, and empower communities to make reproductive choices that are both culturally meaningful and medically safe.

16. Is Consanguinity Relevant in the Present Day?

The relevance of consanguineous marriage in the contemporary world is a subject of sustained academic and policy debate, especially as societies grapple with questions of public health, cultural identity, globalization, and legal modernity. From a cultural and anthropological perspective, consanguineous unions are deeply embedded in social identity as well as kinship ideologies, often perceived as a means of strengthening familial ties, preserving lineage, reinforcing group solidarity, and ensuring the control and inheritance of property [3,16,19,20,80]. For many societies, especially those organized around patrilineal or clan-based systems, such marriages are not merely personal but institutionalized strategies to consolidate power, status, and trust within the extended family or tribe [6,79]. In Islamic contexts, for instance, first-cousin marriages are often religiously permissible and socially accepted, creating continuity between cultural norms and religious doctrines [1,7,21,73]. On the other hand, medical and genetic research has raised significant concerns. Numerous studies have established that consanguineous marriages increase the risk of autosomal recessive disorders, congenital anomalies, stillbirths, and childhood mortality [7,10,81,102]. As health systems evolve and genetic counseling becomes more accessible, there is growing pressure—particularly from biomedical professionals and public health authorities—to discourage such unions, especially where genetic disease prevalence is high.

Economically and educationally, globalization and increasing individual autonomy in marriage choice are challenging traditional kinship norms. In urbanizing societies, rising female education and workforce participation are leading to greater negotiation around spousal selection, often resulting in a shift from kin-arranged to love-based marriages [21]. Migration patterns—especially among diasporic communities from high-consanguinity regions—are also altering practices. In some cases, transnational marriage within kin continues as a strategy to maintain cultural identity abroad, while in others, acculturation has reduced the prevalence of such unions. From a behavioral ecological perspective, the evolutionary benefits once associated with consanguineous marriages—such as enhanced cooperative breeding, kin altruism, and resource pooling—are increasingly being outweighed by the risks posed by reduced genetic diversity and cumulative genetic load in small, endogamous populations [3,4]. Moreover, with declining fertility rates and smaller family sizes in many parts of the world, the social logic of cousin marriage as a strategy for preserving family cohesion may be diminishing. Legally, while most countries do not prohibit first-cousin marriage, many Western and Christian-majority nations have historically criminalized or stigmatized it, influenced by religious and moral codes. However, legal pluralism in multicultural democracies has complicated the regulation of consanguinity, as cultural rights and individual health risks intersect.

However, in the present socio-cultural context, it is difficult to ascertain the continued relevance of consanguineous marriage. From an anthropological perspective, however, the choice to marry a cousin ultimately rests with the individual, reflecting personal agency within democratic circumstances where no one can prescribe whom to marry or not. Nonetheless, what remains crucial is that, irrespective of whether the union is consanguineous or non-consanguineous, proper genetic counseling should precede mate selection.

17. Way Forward and Future Research Directions

Although consanguineous marriage has been widely studied, important gaps remain that call for future research. The following directions are particularly relevant:

17.1. Integrating Multidisciplinary Approaches

Scholarship is often polarized between biomedical studies that emphasize genetic risk [7,11,100,101,102,103,104] and anthropological accounts that highlight kinship, alliance, and economic rationalities [3,6,80,105]. Future research should bridge these approaches, adopting integrative frameworks that can simultaneously address biological outcomes and socio-cultural meanings.

17.2. Longitudinal and Comparative Studies

Most current evidence is cross-sectional, offering only a snapshot of practices. Longitudinal and intergenerational studies would illuminate how consanguinity adapts to processes such as education, urbanization, and migration [16,67,68]. Comparative work across regions where consanguinity is declining (e.g., North India, North Africa) and where it remains stable (e.g., Pakistan, Gulf States) could provide deeper explanatory insights.

17.3. Lived Experiences and Agency

Kinship-centered analyses often overlook the voices of those directly involved, particularly women and youth. More ethnographic research is needed to capture individual experiences of negotiation, resistance, or acceptance of cousin marriage [27,100]. Such studies would enrich our understanding of how agency operates within structural and familial constraints.

17.4. Intersection with Child Rights and Gender Justice

Future work should explicitly examine the overlap between consanguinity and early marriage, adolescent rights, and gender inequality. While feminist and postcolonial critiques have begun to address these issues [27,54,60,87,91], there is scope for connecting these perspectives with international child rights frameworks [87,89,91].

17.5. Technology, Genetic Counseling, and Digital Mediation

The rise of premarital genetic screening and online matchmaking platforms has reconfigured how cousin marriages are arranged and perceived [8,11,92]. Future research should investigate how biomedical knowledge, digital technologies, and kinship logics intersect to reshape marriage practices, especially among diaspora communities.

17.6. Policy-Oriented Ethnography

There is an urgent need for research that evaluates how health interventions, awareness campaigns, and legal frameworks are interpreted at the community level. Studies that combine anthropological insights with public health strategies could help design culturally sensitive interventions, moving beyond top-down biomedical models to community-based participatory approaches [11,102].

18. Concluding Remarks

Consanguineous marriage remains a complex and multifaceted institution situated at the intersection of kinship, genetics, religion, and modernity. Anthropological scholarship demonstrates that such unions are not merely private choices but socially embedded practices that historically served to preserve lineage, property, and identity. At the same time, biomedical research consistently highlights the genetic risks associated with close kin unions, prompting ongoing debates in public health and policy. Contemporary trends reveal a gradual decline in consanguinity in many regions, shaped by modernization, women’s education, migration, and digital mediation, though the practice persists where it continues to provide social and economic security. This duality underscores the need to view consanguinity neither as a relic of the past nor solely as a biomedical risk, but as a dynamic practice continually negotiated within changing socio-cultural and political contexts.

19. Future Prospective