Small Is Big: Making Difference in Lives of Small and Marginal Farmers with Focus on Women Through Rice Nursery Entrepreneurship

Received: 23 August 2025 Revised: 24 September 2025 Accepted: 08 January 2026 Published: 13 January 2026

© 2026 The authors. This is an open access article under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

1. Introduction

“The farming is not new to us; we have been doing it for generations and will keep doing it for generations to come. What we lack is an identity of our own; what we will cherish is an identity as women farmers in Harpur Village, Bihar”.

In India, small and marginal farmers produce 60 percent of the total food grain and 49 percent of the total rice [1]. They are more efficient in terms of productivity and cropping intensity as compared to the large farmers [2]. However, they are highly vulnerable to climate extremes without any viable mode of coping mechanisms. This is mainly because of their dependence on agriculture on monsoon, but unfortunately, the onset of monsoon is increasingly uncertain and erratic due to climate change. For instance, in the state of Bihar in India, the annual rainfall received stood at 689.6 mm, which was 20 percent less than the long run average rainfall of 848.2 mm [3]. Hence, it is crucial to manage the risks involved in rice farming and to develop coping strategies for farmers to address monsoon variability. It becomes more important when it comes to small holders and marginal farmers in rice production, especially the women farmers [4]. A study on climate-smart agricultural practices found that, although women tend to be less aware of these practices than men, they are no less likely to adopt them once they gain access to new knowledge [5].

Women are heavily involved in different value chains in agriculture, they are farmers, they are entrepreneurs, but when it comes to access of productive resources, extension services and markets, they face various obstacles [6]. Often, the role of women in agriculture is underestimated. Indeed, despite their heavy involvement in agriculture, due to the prevailing social norms and male dominance in the society, acknowledging women’s contributions is often confined to within the walls of the home [7], thus making them invisible. As a result, they constantly struggle to establish their identity in general and as farmers in particular due to the existence of non-gender sensitive policy environment [8]. It is important to understand that for women in rural areas, agriculture is important. There is a need for well proven technical interventions which strengthen women’s access to productive resources, manage their time and reduce their labor [9]. We often find that in the case of climate stress; women farmers are most vulnerable. Climate stress has more adverse effects on women than men, and it is not gender neutral [10,11]. Further, the patriarchal system led to women being in a deprived position in terms of land rights. In most of the traditional societies that have a patrilineal system, endowment of women with land is strongly opposed by the men [12]. Across the globe, only 15 percent landholders are women [13], but the land rights in eastern India are a meagre 3.5 percent [14].

The unequal access to productive resources by women is also a matter of concern. In developing countries, women on average comprise 43 percent of the agricultural labor force. Out migration is yet another important reality in rural areas, which has a direct impact on the women of the migrants’ households. In the state of Bihar, out-migration of men for better livelihood is happening since the 19th century and over a period of time, in recent years, it has increased manyfold. The consequences of such migration lead to additional workload for women in the family, including several day-to-day responsibilities. This also leads to increased space for restructuring of the gender relations [15]. They perform more diversified agricultural activities after the migration of the men of the households. For those who worked in the family farm and shared cropping in the absence of the men of the households, the work burden increased tremendously along with the added responsibility of decision making associated with transplanting, sowing, weeding, harvesting, use of seeds and fertilizers [16]. The manifestation of feminization in agriculture is thus a continuous struggle, not just confined to the cultivation landscape, but with the social and political landscape where women are increasingly interacting and engaging in order to sustain their production.

Developing countries are found practicing gradual changes in the adoption of improved agriculture practices, but there is an increasing need for transformative innovations to be adopted at the household level with resilient agriculture practices dealing with rainfall variability and climate stress [17,18]. To address the consequences of climate variability in rice farming, the Cereal Systems Initiative for South Asia (CSISA) introduced the rice nursery entrepreneurship (RNE) concept at both the individual and community levels to support rice farmers in dealing with monsoon variability and generating additional income for their households. The RNE focuses on rice seedling nursery as a business and income-earning opportunity for individual and group entrepreneurs, and quality rice seedling production through training on best-bet agronomic practices. It has had a positive effect on the quality of rice productivity; the transplanting of younger rice seedlings of 15–20 days age resulted in a yield advantage of 1.43 t/ha as compared to the seedlings of greater than 35 days old across 10 districts in Bihar and Eastern Uttar Pradesh during kharif 2018.

1.1. Background to the Inclusive RNE Model in Operation

In order to deal with the monsoon variability and climate change, it is widely acknowledged by researchers, practitioners, and policymakers that addressing gender is important [19,20]. The major factors which act as a stumbling block for their decision making remain their lack of knowledge, poor access to farm information and literacy [21]. CSISA followed a progressive approach by improving direct access to information and technology for women farmers in rural areas.

Women have exclusive needs in order to access and have control over resources. In agriculture, it is important to address their need at the design stage of any program, policy, and project. Otherwise, in due process, they will remain a neglected group without information and service provisions [18]. Hence, it becomes important to create opportunities where women farmers are direct recipients of improved knowledge and can gain access to new technologies to improve their farm production and livelihoods through the Rice Nursery Enterprise. In the eastern Indian state of Bihar, CSISA focused on creating such opportunities, harnessing the important social engine platform of women, the Self-help Group (SHG). By empowering rural women, SHGs have become the vehicle of change for poor and marginalized people to be released from the clutches of poverty [22]. It has also enhanced the status of women as participants, decision makers, and beneficiaries in the democratic, economic, social and cultural spheres of life [23].

1.2. Identity Close to the Heart of a Woman: Self-Identity to Community Identity

The issue faced by women at the grassroots remains their ignorance of being recognized as farmers. In spite of direct and indirect involvement in rice farming, hardly they are recognized as farmers, but as ‘farmers’ wives. Farm women have taken steps forward, forming a farmer identity that is not defined by the patriarchal ecosystem, i.e., the identity of a woman farmer [24] Increasingly, farm women have started identifying themselves as farmers, more so in a collective way, such as SHGs, women cooperatives, etc.

The gap in data might also contribute to the non-recognition of the identity of women farmers. Globally, nearly half of women report agriculture as their primary economic activity, whereas it is more than three fourth in less developed countries [25]. CSISA, since 2014, started working with women and women collectives—recognizing them as farmers and with Mahila Samkhya, a Government of India Program, introduced the concept of ‘Kisan Sakhi’, to establish the identity of a woman farmer as a ‘farmer’ rather than as a ‘farmer wife’. With the self-esteem and confidence women farmers develop, it’s a soft power with which they gain the confidence to lead the change. Along with the recognition of women as farmers at the institutional level, CSISA initiated a capacity-building program on sustainable climate-resilient practice. It is important to understand that the constraints and requirements of women farmers are different from those of men farmers. Women’s day care needs and mobility issues must be considered when designing the program intervention. The prevailing social norms constrain the mobility of women due to less access to transport, as well as to the social restrictions on travelling alone [25]. Owing to this, the capacity building programs were designed at their village, accounting for their time availability and gender sensitive technology intervention in rice, wheat, and maize. The on-field adoption of technologies by women farmers resulted in improved yields, establishing their identity as informed farmers at the community level.

In this process, it was understood that along with recognition and self-confidence, in order to mainstream women in agriculture transformation, it is crucial that the gender gap in using modern tools and technologies be addressed, more in a participatory way. The cultural context with which such a transformation is designed, an appropriate mix of social and technological interventions is a prerequisite. CSISA introduced this to the SHG, where women have a collective voice in carrying out agrarian transformation, which often demands a certain degree of operation at scale.

1.3. Self-Help Group as the Channel for Piloting Rice Nursery Enterprise

It is crucial to consider the cultural context in which a woman belongs and interacts, for designing a program to increase her income and household nutrition in agriculture [26]. In the Indian context, SHGs are a key channel for reaching out to the poor women farmers. SHGs are voluntary associations of 10–20 women members from similar economic and social backgrounds who come together to find ways to improve their living conditions. In India, the self-help group has been a vehicle for a silent revolution positively impacting the social, economic, and political opportunities for women, and is a conducive platform for promoting new technology and improved knowledge about sustainable agriculture practices among the women farmers by leveraging the improved social capital in the SHGs.

In CSISA, SHGs were the conduit for reaching out to the women farmers in rural areas for technology dissemination through community rice nursery entrepreneurship. An evidence-based technology dissemination was promoted among women farmers through the Ministry of Human Resource Development program Mahila Samakhya, State Rural Livelihood Mission JEEVIKA, and a community-based organization supported by private players in the state of Bihar. When we have a bird’s-eye view of women’s empowerment, especially in agriculture, where she is mostly invisible, it is important to understand that her empowerment is not an isolated concept. It is influenced by social norms, her immediate household environment, and the social agencies around her. It is influenced not only by individual change but also by power structures within and between institutional levels.[27]

1.4. Climate Change and Erratic Monsoon

Earlier, the climate-related challenges were minimal. The regular rainfall enabled farmers to have timely rice cultivation and maintain the crop cycle. This also resulted in a low cost of production. However, over the period of time, due to climatic challenges, especially the erratic rainfall, there has been increased dependence on irrigation, which further led to the increased cost of production. The non-availability of improved varieties was another concern in rice productivity. Farmers would grow ‘mota dhan’. They replaced the variety with ‘mini mansoori (MTU 7029)’ for a higher yield of rice than before. Nowadays, with JEEVIKA and CSISA-like interventions, it is easier to connect with people and attend training programs. The information on labor saving techniques and new agricultural practices is readily available. Earlier, women farmers had no such exposure. Indeed, the strategy involving female community associations and Self Help Groups at the entry level in the action research program has the capacity to promote increased productivity and profits in rice enterprises [28].

1.5. Inception of the Inclusive RNE Model

Attributing to gender, women farmers face big hurdles in their agricultural engagement—social, institutional, and technical constraints. It varies from non-identification of women as farmers and systemic exclusion from development programs, lack of targeted extension programs, lack of access and awareness about the programs by women, social and personal misconceptions existing in the ecosystem that women do not have ideas in farming, and they suffer from low self-confidence [29]. Setting priorities and ensuring that the improved agricultural technologies ascertain welfare gain in the context of the patriarchal agrarian system is critical to women farmers and labours. It is equally important to enhance their technological knowledge and skills to implement improved crop establishment techniques [26].

The extent to which men and women can participate and benefit from adaptation is influenced by social and cultural norms [18]. For instance, in the Bhojpur district in Bihar, farmers were found to be addressing the sale of nursery seedlings as a distant social norm. They shared, ‘Hum mori aur chori nahi bechtey—we do not sell our paddy nursery and girls’. It determines the influence of culture and traditions on the agricultural practices in rural India. Understanding the social norms, working in the field with the farmers and realizing the need for innovation in rice farming, which can add income and productivity value to their crops, strategically, rice nursery entrepreneurship (RNE) was introduced, understanding the challenges small and marginal farmers face and the opportunities that lie ahead for the women farmers. It is critical to understand the innovation, which offers economic benefits and options for farmers to deal with monsoon variability, and to act as a catalyst in convincing farmers to adopt it. Where the Rice Nursery Enterprise was exclusively run by women farmers, it was found that they have slowly started sharing the market space which is generally understood to be men domain. This has also slowly started shedding the misconception attached to her capabilities. Accordingly, CSISA adopted a dedicated approach with the women farmers to start their nursery enterprise with Jeevika.

RNE, being a new concept in the area, introduced the farmers to the technical aspect of raising quality nurseries. In the discussion with the farmers for piloting the rice nursery enterprise, two models emerged—single women and men leading their own enterprise and the second one as a community enterprise where a group of women come together to do the RNE.

The intervention followed a bottom-up participatory approach with a series of meetings with multiple stakeholders involving self-help group members of the partner organizations like Jyoti Mahila Samkhya Federation in Muzaffarpur and SEWA Bharat, under ITC Corporate Social Responsibility, women farmers, and a community (rice) nursery entrepreneurship (CNE) concept was piloted. Subsequently, scaling of the CNE was done through the partnership with the state rural livelihood mission JEEVIKA. In the due process, CSISA worked closely with women farmers to bridge the knowledge gap and then reached out to the scaling of its interventions with the Bihar Rural Livelihood Promotion Society, popularly known as JEEVIKA.

1.6. Objective of the Study

Knowledge and information flow need to be linked amongst women to achieve progress in both socio-economic dimensions [30]. It is also important to understand that the behavioral pattern of both men and women is different when the decision making related to any farm practice is concerned. In the same circumstances, women respond differently compared to men of the household. A deeper level of focused attention is required, which reflects the understanding of how both men and women within the same household interact in the enterprise related to farming [31]. Accordingly, research was done in the context of RNE in the state of Bihar (India) with the following objectives:

-

To understand the characteristics and dynamics of nursery raising by individual and group rice growers and entrepreneurs

-

To understand the scope of the nursery enterprise as a profitable and viable option for both men and women farmers

-

To understand the dynamics of women farmers who led the enterprise.

2. Materials and Methods

In the year 2019, in order to understand the process, characteristics and feasibility of rice nursery entrepreneurship (RNE), a field study was organized in the state of Bihar. Two types of nursery enterprises were considered: individual nursery enterprises (INE) and community nursery enterprises (CNE). In addition, the individual farmers who grow nursery for their own purpose (individual growers) act as a control for nursery enterprises in cost comparisons. Further, a comparison between these individual growers and customers of nursery enterprises provides details about the benefits at the farm level. The study approach has been to deep dive into the RNE being carried by the farmers at the individual and group level. Further exploring the models in operation led by women, largely in groups and men farmers at the individual level. The sampling details are provided in Table 1.

Table 1. Sample distribution.

|

Type of Sample |

Sample Size |

Total Sample |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

Men |

Women |

||

|

Community nursery enterprises |

- |

10 |

10 |

|

Individual nursery enterprises |

66 |

7 |

73 |

|

Individual grower |

177 |

21 |

198 |

|

Customer of nursery enterprises |

336 |

69 |

405 |

One hundred and ninety-eight individual growers1 were interviewed (177 men and 21 women growers). The sampling is purposive, covering farmers who have carried out the nursery enterprise at the community and individual levels. In order to understand RNE dynamics, the individual entrepreneurs and group entrepreneurs2 were closely studied to understand the dynamics of their enterprise; in total, 73 entrepreneurs were interviewed, which included 66 men and 7 women entrepreneurs. Ten group leaders of the Self-Help Group and their members were interviewed, who did the business at the group level. Along with the entrepreneurs, 405 customers were interviewed (336 men and 69 women customers). The respondents were mainly the farmers with whom CSISA has worked through community-based organizations, the Bihar Rural Livelihood Promotion Society, and private partners.

In November 2019, the women entrepreneurs from JEEVIKA self-help group, their customers, and the Village Resource Person (VRP) of JEEVIKA, who led the Rice Nursery Enterprise (RNE), were interviewed to get an understanding of the rationale behind starting the rice nursery enterprise, the process involved, the challenges faced, and the viability of the business. In total, five focus group discussions (FGDs), one group discussion with the spouses of the entrepreneurs, four in-depth interviews (IDIs) with two village resource persons (VRPs), the block program manager (BPM), and the district program manager (DPM) were conducted in the Ara district of Bihar. VRPs, BPM and DPM are the officials of JEEVIKA.

3. Results

3.1. Background Characteristics

The age difference across groups (i.e., individual members, individual entrepreneurs, as well as customers was not considerable (they were all in their 40s). However, a stark difference was seen in the level of education and social association. The individual entrepreneurs were better educated than the other two groups. 42 percent of the entrepreneurs were graduates as compared to 11 percent and 22 percent among individual growers and customers, respectively. The women entrepreneurs, though fewer in number, were better educated than the growers and customers. The women entrepreneurs (86 percent) and growers (43 percent) were associated more with organizations than the men. Also, irrespective of gender, the customers were least associated with any organization (16 percent). Further, Table 2 reveals that the total land owned and cultivated is higher among men than women.

Table 2. Land information of the individual nursery growers, entrepreneurs, and customers by gender.

|

Land Holding (Acres) |

Individual Grower (%) |

Individual Entrepreneurs (%) |

Customers (%) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Men (N = 177) |

Women (N = 21) |

Total (N = 198) |

Men (N = 66) |

Women (N = 7) |

Total (N = 73) |

Men (N = 336) |

Women (N = 69) |

Total (N = 405) |

|

|

Total land owned |

|||||||||

|

<2 |

29 |

76 |

34 |

8 |

43 |

11 |

20 |

48 |

25 |

|

2–5 |

53 |

24 |

50 |

8 |

57 |

12 |

61 |

46 |

59 |

|

5–10 |

12 |

0 |

11 |

33 |

0 |

30 |

15 |

6 |

13 |

|

>10 |

6 |

0 |

6 |

52 |

0 |

47 |

4 |

0 |

4 |

|

Total Kharif/Aman rice cultivated area |

|||||||||

|

<1 |

20 |

19 |

20 |

5 |

100 |

14 |

14 |

20 |

15 |

|

1–2 |

35 |

57 |

37 |

8 |

0 |

7 |

51 |

62 |

53 |

|

2–4 |

38 |

19 |

36 |

52 |

0 |

47 |

30 |

17 |

28 |

|

>4 |

7 |

5 |

7 |

36 |

0 |

33 |

5 |

0 |

4 |

3.2. Creating Awareness and Knowledge for the Rice Nursery Enterprise

Awareness and knowledge play an important role and are one of the enabling factors for any business to succeed. The endeavor to start the rice nursery enterprise, which is a new concept for the people, was built on a strong base of awareness and knowledge, not just on the benefits of the enterprise, but also the plausible disadvantages in cases of failure of demand aggregation, etc. However, strategies were adopted to cope with the problems and to make the rice nursery enterprise a viable business.

The farmers never thought that rice nursery could be a business and could be an added source of income generation. Earlier, farmers would grow a nursery for farming, but not for commercial purposes. The surplus seedlings were uprooted from the nursery area (as the plot needed to be used for transplanting) and kept as residue or given for free to other farmers. Hence, RNE, as a concept, was new, and it involved a shift in the community’s perception that ‘seedlings can be sold and have monetary value associated with them’. In order to understand the business aspect of nursery selling, the farmers were queried about the time period since they had seen the business. It helped in understanding their information related to the financial value addition to the seedling through the enterprise, and also exploring further their thought on the feasibility of the enterprise for expansion. Higher percentages of women growers and entrepreneurs have seen the selling of rice nursery earlier than the men growers or entrepreneurs. The growers and entrepreneurs, especially women entrepreneurs, were in favor of rice seedling business as an individual/private enterprise, while customers were in favor of community enterprise (Table 3).

The main source of information for the women who received the information on rice nursery enterprise was the research institution (CSISA), while for men farmers the sources of information were printed materials from CSISA, agriculture input dealers, and research institution. Almost all the entrepreneurs, irrespective of gender, reported that social networking helped in the nursery business.

Table 3. Knowledge about the nursery business among the farmers’ groups (Time period).

|

Passive Experience of Rice Nursery Enterprise |

Individual Grower (%) |

Individual Entrepreneurs (%) |

Customers (%) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Men (N = 177) |

Women (N = 21) |

Total (N = 198) |

Men (N = 66) |

Women (N = 7) |

Total (N = 73) |

Men (N = 336) |

Women (N = 69) |

Total (N = 405) |

|

|

Ever seen the practice of selling rice nursery in the area |

22 |

33 |

23 |

18 |

100 |

26 |

21 |

19 |

20 |

|

Period when it came to the knowledge |

|||||||||

|

0–1 year |

63 |

71 |

64 |

25 |

0 |

16 |

83 |

46 |

77 |

|

2–3 years |

13 |

14 |

13 |

17 |

71 |

37 |

10 |

54 |

17 |

|

3–5 years |

8 |

0 |

7 |

25 |

14 |

21 |

3 |

0 |

2 |

|

More than 5 years |

16 |

14 |

16 |

33 |

14 |

26 |

4 |

0 |

4 |

|

The rice nursery business should be introduced as |

|||||||||

|

Community enterprise |

29 |

29 |

29 |

25 |

0 |

16 |

54 |

46 |

52 |

|

Private/individual enterprise |

71 |

71 |

71 |

58 |

100 |

74 |

44 |

54 |

45 |

|

Partnership within the same social settings /homogenous group |

0 |

0 |

0 |

17 |

0 |

11 |

3 |

0 |

2 |

3.3. Going Against the Social Norm (Attitude) That Nursery Seedlings Cannot Be Sold, the Case of JEEVIKA in Ara

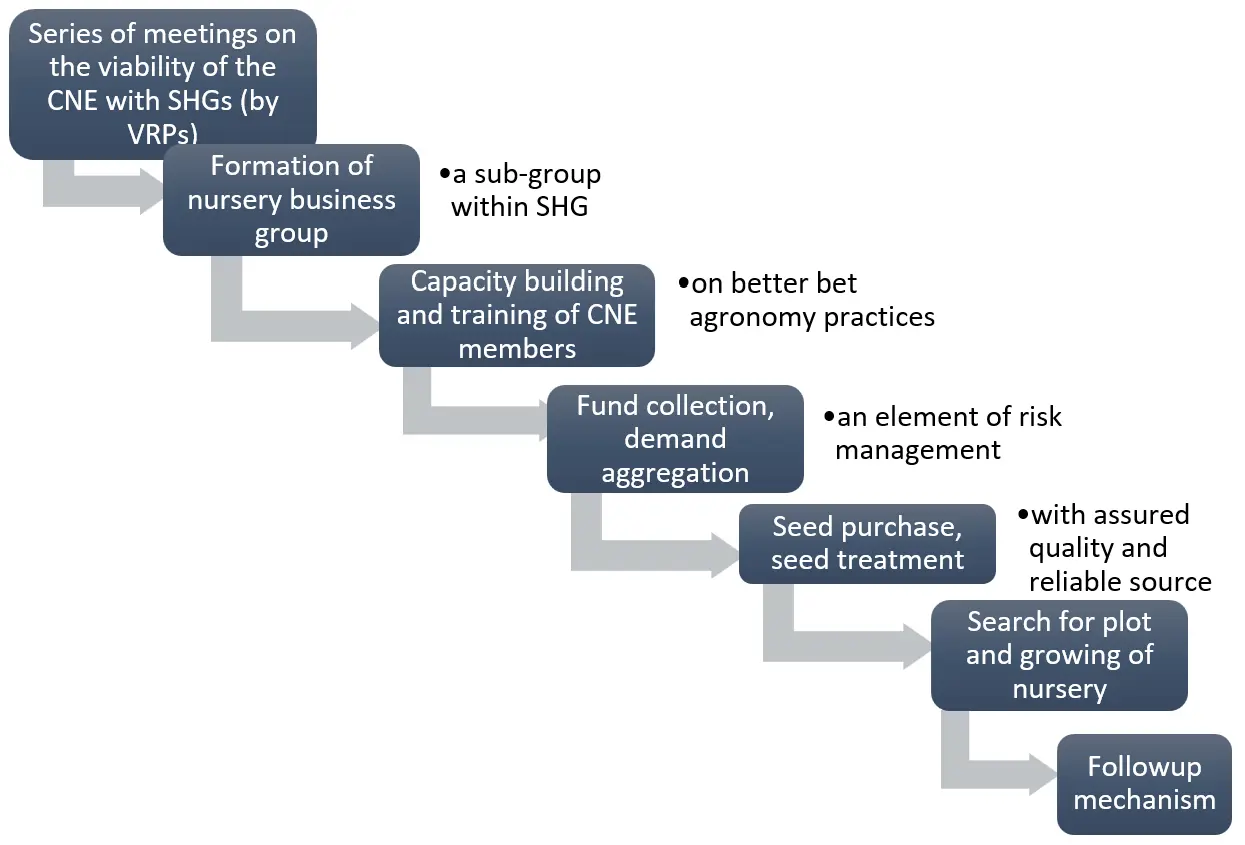

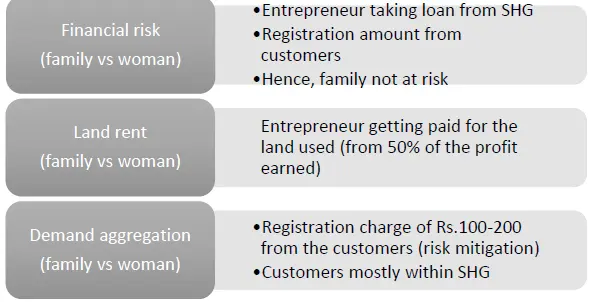

In 2016, the VRPs who were trained under the CSISA Trainee of Trainers (ToTs) model reached out to the farmers for starting the first-ever rice nursery enterprise in their villages. Initially, this was contentious as it was a new concept and had never been done by anyone in the village or in the vicinity. The farmers were sceptical about taking the initiative to start the business. CSISA played an important role as a catalyst during this process by putting forth the technicalities for running the business. Together with the dedicated work of Village Resource Persons (VRPs), they did a scoping exercise to mitigate the risk of starting the business. The farmers, especially women farmers, faced several challenges, but their aspirations did not let them stop. The same approach was used under the CSISA Trainee of Trainers model with JEEVIKA in 2017, see Figure 1. The JEEVIKA VRPs met the women from self-help groups and discussed with them the prospects of starting the rice nursery enterprise. They played a crucial role in motivating women farmers to take up the business model. A series of meetings was held by the women farmers within their SHG, brainstorming on the pros and cons of the rice nursery enterprise.

It is also important to highlight that the group affiliation gives a level playing field for women to try new innovations and have better risk-taking capacity. The self-help groups act as an important conduit for providing a safe space for women to come together, discuss, debate, and try out new initiatives, forming opinions. Self-help groups have emerged as an important source of social capital, where women interact and act together with trust and mutual cooperation. The RNE emerged as one of such examples in agriculture where the power of SHGs has crossed the barriers of social norms and stigmas related to the selling of nurseries. The affiliation to SHGs empowers them with larger control over income and better decision making over the credits [32]. This provided a strong base to take the innovation among the farmer community.

Awareness and knowledge create the base, but the attitude is the result of the social norms and practices. According to one FGD with the women rice nursery business group, the men in the villages said ‘kutta bhi nahi aayega beechda lene’ (even dogs won’t come to purchase seedlings). However, the group now proudly says that ‘… ab to bade bade aadmi aa rahe hai bichda khareedne’ (… now big (influential) people are coming to buy seedlings). As a result of societal attitudes, women themselves were skeptical about starting the business. The concerns (challenges) had been:

-

Whether it will be an initiative worth starting for a woman to lead?

-

How to pool resources like capital, manpower, skills, and knowledge to raise healthy seedlings for commercial purposes?

-

Whether it will be a viable business?

-

Whether there will be enough demand aggregation for the seedlings?

3.4. Process Adopted and RNE Model

The approach adopted by the women farmers involved getting the members within the self-help group together who were interested in the RNE. Hence, a sub-group was formed within the SHG exclusively for the RNE. The meetings were held at the SHG level, with all members in attendance, and, after a mutual decision, subgroups were formed consisting of the members who would lead the RNE. After forming the sub-group, training of the members was held on better bet agronomy practices, and the members collected capital money for the business (through micro planning). For this, they followed a two-pronged approach:

-

Took a loan from their self-help group and

-

an advance payment from the customer as part of the registration fee.

It is important to note that during registration, charging a nominal amount of Rs. 100 to 200 prospective customers was a well-thought-out risk-mitigation strategy by the entrepreneurs’ group. Customers comprised of the members from their own SHG, other self-help group members of the nearby community and also fellow farmers from the village in some places. However, initially, the customers were not ready to pay Rs. 100 as they suggested the group first grow the seedling and then demand money. However, the customers were later convinced by the nursery business group and the VRPs of the importance of collecting the money. To initiate the process, the nursery business group members themselves contributed the registration amount first.

The business group would then start looking for a plot for a nursery. The selection of the plot was based on the Standard Operating Procedures shared by the scientists’ team of CSISA, such as feasibility and availability of irrigation facilities, suitable varieties, date of sowing, etc. Under the guidance of the trained VRPs, the rice bed was formed for the nursery. This was mainly done for value addition and to attract customers to buy the seedlings. For quality assurance, the VRPs bought seeds from KVKs (Krishi Vigyan Kendra). The members of the business groups themselves worked in the field to save labor cost. They were mocked for the field work, but they ignored what others in the village had to say as they believed ‘they were doing their own work’. ‘Hum apnaa kaam kar rahey they, hansne waale hanstey rahe. Par jab humara business hua to wahi log humaarey grahak bhi baney’ (We were giving our labor for our own business, people who were mocking us, were the ones who were our customers when the seedlings were ready for selling)—Woman farmer, rice nursery business group member.

The negative attitude was changed through a series of meetings that brainstormed the pros and cons of the rice nursery enterprise. The challenges were transformed into opportunities. The best-bet agronomic practice training received by the entrepreneur team (both male and female farmers) created an enabling environment for value addition to their product.

3.5. The Enabling Factors (Opportunities) for the Rice Nursery Enterprise

-

Capacity-building support helped them understand the technical and financial nuances of the business

-

Improved knowledge on better bet agronomy practices for raising healthy seedlings with market value through trainings

-

Openness and flexibility towards negotiation

-

Conducive risk-sharing platform

-

Buying seedlings is a less risk-taking product for the customers, and they are assured about the quality of the seeds by seeing the seedlings.

Farmers received training on the package of practices for developing healthy seedlings, the importance of young seedlings and their effect on productivity, value addition to the seedlings as a source of generating additional income to the household led by women of the family.

3.6. Seed Variety Details of Individual Growers and Nursery Entrepreneurs (2017)

Farmers mainly used high yielding variety seeds (Table 4). The three most important sources of seeds for the farmers were their own saved seeds from previous production, local input shops and KVKs (Krishi Vigyan Kendra)/Universities. The majority of the farmers used certified seeds. However, a higher percentage of women farmers than men farmers had no idea whether the seeds were certified or not. There is a need to increase awareness of seed certification among women and to educate men and women farmers about seed treatment.

Table 4. Types of seeds used by individual growers and entrepreneurs.

|

Types of Seeds Used |

Individual Grower (%) |

Individual Entrepreneurs (%) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Men (N = 201) |

Women (N = 22) |

Total (N = 223) |

Men (N = 66) |

Women (N = 7) |

Total (N = 73) |

|

|

Number of varieties used for the nursery (mean number) |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

|

High Yield Varieties |

73 |

68 |

72 |

63 |

57 |

63 |

|

Hybrid |

26 |

32 |

27 |

32 |

29 |

32 |

|

Local |

2 |

0 |

1 |

5 |

14 |

6 |

Time of seeding nursery: For men growers, the approximate time of seeding nursery in the village was from mid-May to mid-June, while for women growers it was from mid-June to the end of June. The main deciding factors for the timing of seeding in the nursery were irrigation, seed availability, variety duration, and the onset of pre-monsoon rain. The dependence of women growers on the onset of pre-monsoon rain for seeding nursery was higher than that of men growers. This explains why the women growers reported the end of June as the time of seeding the nursery (Table 5).

Table 5. Time of seeding nursery by individual growers and entrepreneurs.

|

Time of Seeding the Nursery |

Individual Grower (%) |

Individual Entrepreneurs (%) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Men (N = 177) |

Women (N = 21) |

Total (N = 198) |

Men (N = 66) |

Women (N = 7) |

Total (N = 73) |

|

|

Approximate time of seeding the nursery in your village |

||||||

|

15–30 May |

53 |

14 |

49 |

29 |

29 |

29 |

|

1–15 June |

41 |

33 |

40 |

58 |

57 |

58 |

|

15–30 June |

7 |

52 |

12 |

9 |

14 |

10 |

|

1–15 July |

0 |

0 |

0 |

5 |

0 |

4 |

|

Deciding factors for the time of seeding the nursery |

||||||

|

Irrigation source |

94 |

81 |

92 |

91 |

14 |

84 |

|

Onset of pre monsoon rain |

19 |

67 |

24 |

29 |

100 |

36 |

|

At the outbreak of the monsoon |

1 |

14 |

2 |

5 |

43 |

8 |

|

Weather prediction modules |

20 |

10 |

19 |

6 |

0 |

6 |

|

Variety duration |

57 |

52 |

56 |

44 |

43 |

44 |

|

Availability of seeds |

86 |

71 |

84 |

91 |

86 |

90 |

|

Availability of subsidy |

22 |

5 |

20 |

39 |

0 |

36 |

|

Others |

0 |

0 |

0 |

8 |

0 |

7 |

|

If the decision is based on the onset of monsoon rains, what are the reasons? |

N = 48 |

N = 26 |

||||

|

Lack of a source of irrigation |

59 |

100 |

71 |

90 |

100 |

92 |

|

Cost of irrigation |

77 |

36 |

65 |

84 |

100 |

89 |

|

Tradition |

6 |

0 |

4 |

16 |

0 |

12 |

3.7. Demand Aggregation by the Entrepreneurs

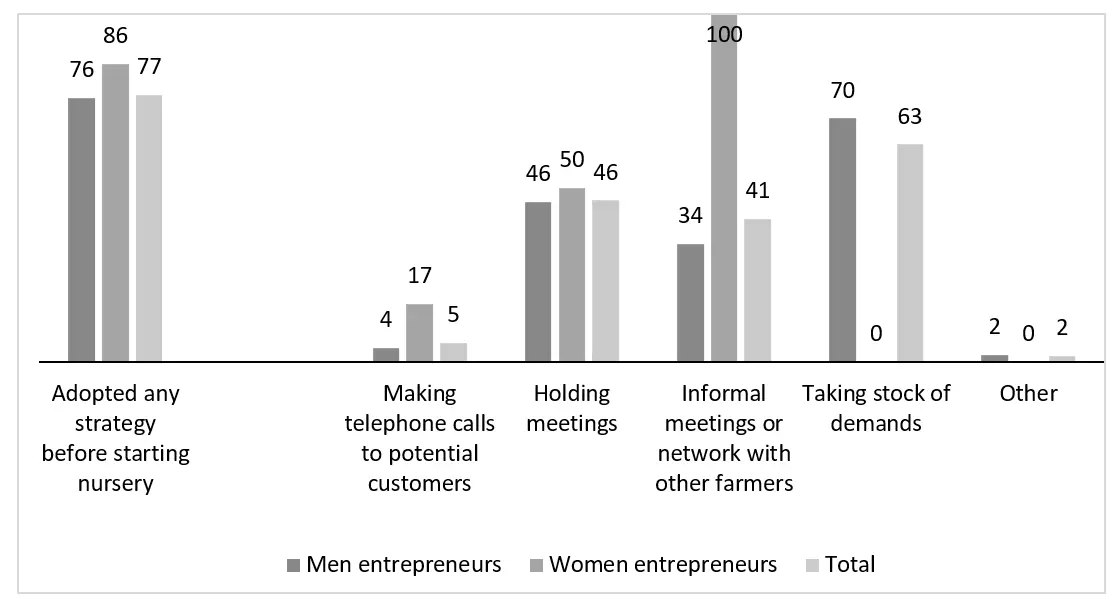

The entrepreneurs followed a demand aggregation strategy to get their customers. They did their customer profiling beforehand through physical meetings with fellow farmers, both in the form of formal and informal and telephonic calls. It is interesting to note that 70 percent of the men entrepreneur had already taken the stock of demand while none of the women entrepreneur did so (Figure 2).

Follow up mechanism: In order to ascertain the quality of their seedling produced, they planned to follow up with the customers regarding the productivity of the seedlings they have sold and transplanted by their customers in the field. The follow up with customers is done through the following mechanisms:

-

Taking stock of the growth of the standing crop quality and productivity

-

Visiting the plots of the customers to progressively follow the standing crop and noting the difference in the productivity and quality of their customers.

3.8. Challenges Encountered

Nursery raising: A major limitation was the weak and variable monsoon. The second limitation faced by entrepreneurs was, the management issues like fertilizer application, demand aggregation etc. (Table 6).

Table 6. Problems faced during nursery raising by individual growers and entrepreneurs.

|

Problem Faced During Nursery Raising |

Individual Grower (%) |

Individual Entrepreneurs (%) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Men (N = 177) |

Women (N = 21) |

Total (N = 198) |

Men (N = 66) |

Women (N = 7) |

Total (N = 73) |

|

|

No problem |

6 |

14 |

7 |

11 |

43 |

14 |

|

Management issue |

4 |

10 |

5 |

33 |

57 |

36 |

|

Health issue |

4 |

5 |

4 |

5 |

0 |

4 |

|

Drudgery |

3 |

24 |

5 |

6 |

0 |

6 |

|

Weak and Variable monsoon |

85 |

57 |

82 |

50 |

0 |

45 |

|

Others |

5 |

5 |

5 |

21 |

57 |

25 |

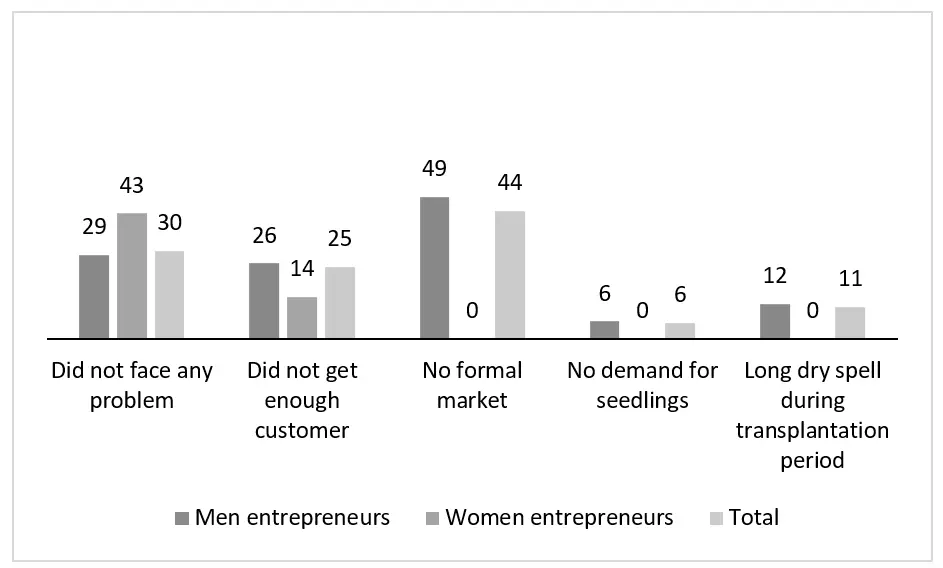

Nursery selling: The maximum percentage of women entrepreneurs did not face any problem in comparison to men. It is quite interesting to observe that the women entrepreneurs only shared a lack of enough customers as their major concern. This may be because it was a new initiative not only for the entrepreneurs but also for the customers. The men farmers highlighted problems, apart from not getting enough customers, such as no formal market, and a long dry spell during the transplantation period (Figure 3). Because it’s a new initiative, a formal market was not in place for selling seedlings, as compared to what the farmers have access to for selling vegetables and livestock products.

The women farmers who led the group enterprise reported management issues, unfavorable weather (scanty and variable rainfall) and drudgery during the raising of bed nursery as the main problems. Here, it is important to note that the group had done the business of a mat-type nursery. Out of ten groups, three groups reported no issue while growing their nursery seedlings, three groups reported management issues, two groups reported unfavorable weather and two other groups reported drudgery as the main issue. It is important to observe that the majority of the groups did not face any problem in selling the nursery.

3.9. The Cost-Benefit of the RNE Model

In JEEVIKA, carrying out the RNE in groups helped the women farmers to pool resources effectively. Here, women farmers have done nursery seedling raising for manual transplanting. It helped them to do planned investment with calculated risk and easy financial credit access from their self-help groups. This also helped them in advance planning for demand aggregations and also getting the customers. The young seedlings of 14 to 18 days were being sold at the cost of INR.450–550 per bigha (INR.720–880/acre). The rate was decided after calculating the cost of production and in discussion with the VRPs and the nursery business groups. Even the nursery business group members (including the entrepreneur) had to buy the seedlings. In the case of Group 1, the total investment cost was INR.16,200, and the total income was INR.43,000. After paying the loan and recovering the cost of production, the total profit earned was INR.27,000. The strategy for saving labor cost helped them to have a margin in profit making. Table 7 presents the Cost-benefit analysis.

Table 7. Cost-benefit analysis.

|

Total SHG Members |

Total Nursery Group Members |

Fund from SHG |

Number of Customers |

Registration Amount Charged |

Total Nursery Area |

Total Transplanted Area |

Total Investment Cost |

Total Income |

Total Profit |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Group 1 |

12 |

8 |

12,000 |

42 |

INR.4200 (Rs.100 per customer) |

32 kattha |

81 bigha (27 acre) |

16,200 |

43,000 |

27,000 |

|

Group 2 |

22 |

6 |

None |

22 |

INR.4400 (INR.200 per customer *) |

14 kathha |

66 bigha (22 acre) |

5550 |

17,882 |

11,000 |

|

Group 3 |

12 |

4 |

None |

32 |

INR.3200 (INR.100 per customer) |

15 kathha |

36 bigha (12 acre) |

5860 |

19,400 |

12,000 |

|

Group 4 |

22 |

5 |

3000 |

22 |

INR.2200 (Rs.100 per customer) |

22 kathha |

32 bigha |

5360 |

14,212 |

8852 |

|

Group 5 |

23 |

4 ** |

None |

37 |

INR.3700 (INR.100 per customer) |

14 kathha |

16 bigha |

6900 |

19,682 |

12,721 |

* Rs.200 each was collected because this group comprised large farmers. The nursery group members paid the difference between the cost and the total funds collected. ** did not take a share in the profit, instead bought a seedling.

3.10. Mechanism for Profit Distribution Among the Group Members: The Profit Earned Was Divided into Two Ways

-

One half would go to the farmer whose land was used. The reasons behind accepting the half profit to be shared with the leader are:

- (a)

-

The land is contributed by the leader

- (b)

- She is the one who takes a loan from the SHG on her name to carry out this business with the RNE team. In their words, she is the main risk taker along with others.

-

The other half would go to the other members in the nursery business group.

It is important to note here that the decision for profit sharing is decided by the members themselves, where they make sure that transparency and giving due to each group member are assured. The other members accepted this strategy after doing the cost calculation of the profit sharing. Since they are members of the SHG, the loan which was taken was a shared loan, labor was also shared between the members, and hence the profit sharing was done on the basis of the contributions made while carrying out the business.

3.11. Cost of Rice Nursery Enterprise: 2017

Investment made by farmers for raising both mat and manual nursery input costs was calculated in detail. It was found to produce seedlings of manual and mat type nursery for one acre of land, the entrepreneurs invested on an average of INR.15,729. It was seen that 42 percent of women farmers and 35 percent of men farmers raised mat type nursery whereas 58 percent of women farmers and 65 percent of men farmers opted for manual nursery. It is also evident from the data that since a greater number of women farmers opted for mat type nursery in the study, their investment was more. The uprooting cost has not been accounted for, as it is a part of the expense incurred by the customers (Table 8).

Table 8. Cost of Rice nursery enterprise.

|

Cost of Inputs (INR/Acre) |

Men |

Women |

Total |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Seed |

646.44 (531.79) |

675.04 (961.45) |

649.22 (577.16) |

|

Nursery Area |

0.36 (0.32) |

0.17 (0.19) |

0.34 (0.31) |

|

Transplanted Area |

17.08 (14.95) |

14.71 (15.94) |

16.85 (14.95) |

|

Machinery cost (Bed preparation) |

130.74 (97.98) |

83.88 (52.29) |

126.18 (95.29) |

|

Labor cost (Bed preparation + irrigation) |

142.03 (134.37) |

181.67 (127.17) |

145.89 (133.34) |

|

Strawpolycost (Cost of Polythene etc.) |

48.29 (78.08) |

44.58 (63.00) |

47.93 (76.36) |

|

FYM |

38.49 (60.71) |

10.88 (18.79) |

35.81 (58.48) |

|

Fertilizer |

36.83 (50.47) |

13.09 (22.85) |

34.52 (48.89) |

|

Irrigation |

52.33 (63.33) |

35.30 (29.70) |

50.68 (60.96) |

|

Total Nursery Cost |

15,530.61 (13,859.42) |

17,578.28 (21,230.5) |

15,729.69 (14,546.8) |

|

Average cost of transplanting/acre |

1128.92 (592.05) |

1044.50 (1050.48) |

1120.72 (640.197) |

3.12. Outcome of Rice Nursery Enterprise

Effect of Rice Nursery Enterprise on the Yield of Rice

The entrepreneurs used better bet agronomy practices for growing young and healthy seedlings. As a result, there has been a positive shift in the paddy yield of the customers. Customers reported a higher yield increase than individual growers and entrepreneurs (Table 9). Across individual growers, individual entrepreneurs, and customers, >50 percent (and up to 80 percent in some cases) said that yield was improved. The customers had the upper hand in the rice nursery business because they had the opportunity to see the quality of the seedlings before the purchase. They could also monitor the nursery and knew about the quality of seed used and the type of seed treatment done. The customers were in a no-risk zone. As a result of CNE, an additional area of the village was transformed under healthy seedlings transplanting, which has a positive impact on productivity as a result of using a high yielding variety.

Table 9. Effect of nursery management on the yield of rice.

|

Effect of Nursery Management on Yield of Rice |

Individual Grower (%) |

Individual Entrepreneurs (%) |

Customers (%) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Men (N = 177) |

Women (N = 21) |

Total (N = 198) |

Men (N = 66) |

Women (N = 7) |

Total (N = 73) |

Men (N = 336) |

Women (N = 69) |

Total (N = 405) |

|

|

Does not affect |

40 |

10 |

36 |

5 |

17 |

6 |

7 |

9 |

7 |

|

Yield decreased by 10% |

7 |

5 |

7 |

3 |

0 |

3 |

4 |

6 |

5 |

|

Yield decreased by 20% |

0 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

0 |

3 |

10 |

6 |

9 |

|

Yield decreased by more than 20% |

1 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

3 |

1 |

|

Yield increased by 10% |

42 |

48 |

43 |

52 |

67 |

53 |

40 |

25 |

37 |

|

Yield increased by 20% |

10 |

33 |

12 |

30 |

17 |

29 |

33 |

47 |

35 |

|

Yield increased by more than 20% |

1 |

5 |

1 |

6 |

0 |

6 |

7 |

4 |

7 |

3.13. The Decision-Making Authority on the Profit Earned

Kandiyoti [33] outlines contexts of ‘classic patriarchy’—patrilocal extended households where a senior man is in control of the family, including younger men. Hence, apart from Southeast Asia, Asian women have little decision-making power at the household level, including on the use of their own earnings [11]. To reword Doss [9], but in another regard, the majority of women farmers live in male-headed households and farm on male-owned plots. Access to resources does not guarantee control over them [34], since the one in control might dominate in the decision making. We can also distinguish between various critical ‘control points’ within the decision-making process itself, where such control is defined in terms of the consequential significance of influencing outcomes at these different points. Distinguishes between the ‘control’ or policy-making function in making decisions about resource allocation and the ‘management’ function, decisions which pertain to implementation [35].

In this study it can be seen, the women (from FGDs in Ara district) who had earnings from the business had the priority in the decision making to spend the income generated from RNE. The money they earned was not shared with their husbands. According to them, it’s their money (ye huamra apna kamaya hua paisa hai, to hum hi isko kharch karengey na (we have earned this money and we will only use it)) and they have the right to decide what to do with that amount. The members of the CNE considered Rs.2000 as their extra added income source within a short time period of 15 days.

Expenditures area from the earnings of RNE:

-

The majority in this group have kept it in the bank

-

Have spent the income on daughter’s education, paying school fees

-

Have spent the earnings on the medicines

-

Doing the fisheries business

One woman reported that she decided the expense with the husband, but she was the primary decision maker. Another woman reported that her daughter had a problem in school due to non-payment of fees. As soon as she got the money, she paid the school fees and that enabled her daughter to take the exam. In such cases, earlier, the woman had to look up to her husband for money. According to the women, the money they earned was:

‘1600 rupayee hamare liye dher hai’ (INR.1600 enough for us), ‘Upari aamdani hai’ (it’s an additional income), ‘mera paisa hai’ (it’s my own money).

3.14. Rice Nursery Enterprise as a Viable Option to Tackle the Monsoon

All the farmers and entrepreneurs reported that the non-availability of nurseries is a constraint for transplanting, even if the normal monsoon arrives on time. Buying seedlings can ensure timely transplantation. The rationale behind buying seedlings is:

-

Quality seed assurance

-

Quality seedling assurance

-

Can see and monitor the quality before buying

-

Entrepreneurs do seed sorting and treatment to ensure the quality of the seedlings

-

Get healthy and young seedlings without risk

-

Time saving

-

Assured increase in rice yield

-

Maintains crop cycle

The RNE is an important viable option for the women farmers to generate added income in a short duration of 15 to 30 days. The reasons behind the sustainability of the business remain the group mechanism and the self-help group mode, which enabled them to take shared risk, financial credits and also develop confidence amongst themselves to negotiate with the customers. They clearly state, ‘at the individual level’, this is difficult to be taken forward owing to less scope for risk taking opportunity and smooth credit support. Also, small, fragmented land, no irrigation facility, are other factors that make RNE not so viable for individual farmers. One of the woman entrepreneurs reported low quality seed to the VRP. The VRP had bought seed form the KVK. He immediately contacted KVK, and the seed was replaced. This would not have been possible in the case of purchase from the local shop. The cost of labor will increase the cost of production (ultimately increasing the cost of seedlings to be sold), which is not the case in a community nursery. It is easier to do demand aggregation as a community than as an individual (faith generation).

The time saved due to the community nursery was used productively. A woman entrepreneur invested the profit earned from the nursery enterprise (INR.6000) in the fishery. The remaining money she got from JEEVIKA (INR.17,000). The total income from the fishery was INR.36,000. This is an additional value to RNE. The women are earning around INR.2000 in 15 days, which is considered an additional income. When this money is used for further business investment, the profit can be increased manifold. Synergy of themes can be initiated to increase the income.

3.15. The Demand Side: Customers’ Viewpoints

In order to understand the perspective of the customers, they were interviewed to understand their perspective regarding the RNE. In spite of being the farmers themselves, why did they choose to buy seedlings rather than grow them on their own? The customers did not face any problems buying the seedlings (Table 10 and Table 11), as they considered it more economical and viable than growing a nursery.

Table 10. Seedling purchase by the customers.

|

Reason for Buying Seedlings |

Customers (%) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Men (N = 336) |

Women (N = 69) |

Total (N = 405) |

|

|

No time for nursery raising |

21 |

15 |

20 |

|

Nursery raised but got spoiled |

19 |

6 |

17 |

|

Nursery is easily available in the market |

2 |

0 |

2 |

|

More economical and viable to buy than to grow a nursery |

73 |

81 |

75 |

|

Bought all the seedlings that were required |

72 |

33 |

65 |

|

Problem faced while buying the seedling. |

|||

|

I did not get healthy seedlings |

1 |

0 |

1 |

|

I did not get the seedling at the right time |

1 |

0 |

1 |

|

I did not get the desired quantity of seedlings I was looking for |

0 |

1 |

0 |

|

I did not get the preferred variety |

5 |

3 |

5 |

|

Did not face any problem |

94 |

96 |

94 |

Table 11. Customers’ recommendation.

|

Customers’ Recommendation |

Customers (%) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Men (N = 336) |

Women (N = 69) |

Total (N = 405) |

|

|

Recommend this entrepreneur to neighboring farmers |

92 |

96 |

93 |

|

Willing to purchase seedlings next year from the same entrepreneur |

76 |

87 |

78 |

3.16. Men’s Perspective on RNE

It is important to understand that women’s empowerment is not a standalone concept. In rural India, women’s empowerment is related to her immediate environment, social structure, and household dynamics. When it comes to women farmers, the relational attributes to her empowerment need a deeper level of understanding to plan the intervention for development oriented towards her. The concept of power, through to understand her empowerment, hence becomes crucial [36].

In the case of a community nursery, it is very interesting to experience how women farmers leading an enterprise with their on-field activities, financial management and social networking being a part of a self-help group doing a successful enterprise, has resulted in a transition in the mental block of men of the family and community towards her efficiency and importance.

The male members had several questions regarding the concept and success of the rice nursery enterprise. In the beginning, they had a critical opinion of the women doing the RNE. However, they did not stop their wives from doing business. The reasons behind finally allowing women to do RNE have been their affiliation with a self-help group and the credit support they could access from JEEVIKA for Men. Figure 4 presents men perspective. Questioned about doing business with women. To describe the sentiments in their own words, the men reported:

That their wives are now the ‘supporting point’‘ab bachhe ka bhavishya achha hoga wife ke support se’ (better future for children with wife’s support). ‘pehele laga wife ko kaam karne ki jarurat nahi hai…jitna hum kamate hai utna bahut hai…lekin jab dekha group me hai tab theek laga’ (Initially felt no need for my wife to work…whatever I earn is enough…but then agreed when I saw the group affiliation). ‘pehele lagta tha ki ghar ka kaam to hota nahi hai ab beech daalegi…lekin ab aisa nahi lagta’ (Earlier felt that she is unable to handle household tasks how come now she will grow nursery…but now perception has changed). ‘aisa hone se sambandh ache hue’ (better conjugal relation). ‘hum bhi sunne lage hai biwi ko’ (we have started listening to our wives).

The nursery enterprise presents an exclusive intervention in rice farming, where men are co-travellers in the change process: first, they will oppose, then retaliate, then observe and see the result become part of the journey. The core is the economy. So, as rightly said, economic empowerment opens the door for women’s empowerment, which is also well proven by the RNE. In small rural communities, in order to make farming sustainable, the cooperation between husband and wife is important. There is a thin line between business relations on the farm of the family and the family relations within the farm household [37].

3.17. Perspective on the Continuity and Viability of the RNE from Women Farmers’ Perspective

The visit of scientists from CSISA, KVK and other departments boosts the confidence of the farmers. It was found during the study with JEEVIKA that the capacity building of the VRPs through the Training of Trainee model (ToT) to train the women farmers helped women farmers in taking the lead in new initiatives. One of the reasons is that the VRPs are from their local community, and hence, trust among women farmers and VRPs is inherent. The identity is close to women’s self-esteem, and the association of being a JEEVIKA SHG member has given them an identity of being recognized in the community. The woman entrepreneur and her team are the sub-group created for the business on RNE from the self-help groups operational in the village.

The RNE has added one aspect to it of being a ‘Women farmers’ Rice Nursery Entrepreneur Groups’ in the rice farming ‘Pehele pati ke naam se jaante the ab hamara naam liya jata hai’ (earlier known with our husband’s name, but now people know our names). This led to increased self-efficacy among the women farmers. It won’t be a left-handed compliment to say that the rice nursery business initiative resulted in improvement in their decision making with improved bargaining power. It created platforms for the women to negotiate both at the family and community levels. They themselves feel they are better heard and respected, not only in their families, but also in the community. They are listened to because of the skills and the knowledge acquired for healthy nursery raising, and the monetary value added to the seedlings. They take pride in the fact that they have earned this income themselves under their own leadership. It is important to note how they affiliate this income as their ‘very own’ and hence have negotiation scope in their decision making to spend the income as they prioritize. They look forward the next year to do it again. The nursery business group has followed up mechanism. After the seedlings were sold, they followed up with the customers regarding the yield. This strategy can be considered for customer retention and aggregation. The women farmers feel confident about the group effort. They, in a true sense, represent the phrase ‘united we stand, divided we fall’.

3.18. Learnings: Opportunities, Challenges and Way Forward

3.18.1. The Opportunities

In short, the RNE model can be described under the A’s:

-

Awareness among women farmers to start the rice nursery enterprise along with technical and financial information

-

Availability of conducive environment, training, knowledge, factors of production

-

Accessibility of training, factors of production

-

Affordability by raising money through customer registration and loan from SHG

-

Aggregation of demand for the business, where SHG played a pivotal role

-

Adherence to the effort.

3.18.2. Key Findings

-

Farmers found the rice nursery enterprise (RNE) to be a profitable business.

-

The majority of the farmers owned the feasibility of RNE as an added source of income in rice farming, generating profits and tackling monsoon variability. They also expressed their interest in its expansion with the creation of a supportive ecosystem.

-

Willingness was seen to purchase seedlings next year from the same entrepreneur. Customers consider it more economical and viable to buy than to grow a nursery.

-

Women growers and entrepreneurs are either associated with or in a leadership position of Self-Help Groups with organizations more than the men farmers.

-

The women entrepreneurs did not face any problems related to the formal market, demand for seedlings, unlike men entrepreneurs during nursery raising. Women farmers’ association with SHGs is a major factor behind this. They get the customers through their group networks.

-

Nursery management resulted in an increase in the yield level of rice for the women farmers than the men.

-

As compared to men farmers, more women farmers are planning to buy nursery from the group or individual entrepreneurs for the next season or to start a manual nursery business.

-

The majority of the farmers, both men (86 percent) and women entrepreneurs (100 percent) reported that non-availability of the nursery was a constraint for transplanting even if the normal monsoon arrives on time.

-

Social networking helped both men and women farmers in the nursery business to get customers.

-

For women farmers, the Self Help Group was a conduit.

-

Ownership of RNE from the State Rural Livelihood Mission gives a scope for expansion of the program with a larger impact area in the state.

3.18.3. The Challenges

-

The onset of pre monsoon rain is one of the major deciding factors for the women farmers for the time of seeding the nursery. This dependence is due to a lack of irrigation facilities. This holds equally for male farmers, but then their access to irrigation water from tubewells is a bit more easily accessible in comparison to that of the women farmers.

-

The major requirement for entrepreneurs to continue or expand the nursery business is to get the weather advisory on time. Non conducive weather is the main issue faced by the entrepreneurs.

-

More women customers are unaware of seed certification on high yielding hybrid/ varieties, and are more likely to prepare a healthy nursery than men customers.

3.18.4. The Way Forward

-

Provide time bound weather information to the entrepreneurs to tackle non–conducive weather. The timely weather information will play a key role in the planning of the business and variety selection by the farmer.

-

The capacity building program around Nursery Enterprise should focus on making women farmers aware of technical knowledge like seed certification.

-

To assess and understand the process to make irrigation facilities available and affordable to women farmers.

-

Strengthening the social network linkages of the farmers. There is a need to further understand and explore SHGs as a conduit for expanding the Nursery Enterprise.

-

To assess and understand the process that did not allow women customers to buy all the seedlings that were required.

-

Expansion of CNE with JEEVIKA, State Rural Livelihood Mission, to have a larger sustainable impact and huge scope for strengthening the linkages of small and marginal farmers especially women farmers to improved techniques in better bet agronomy practices in rice farming.

-

Institutions like JEEVIKA, State Rural Livelihood Mission, women centric and that work closely with the women farmers can act as the catalyst for increasing productivity and profitability in rice related enterprise.

-

Follow up studies focusing on the Community Nursery Enterprise, exploring the expansion and sustainability of it for empowering women in agriculture.

4. Conclusions

A detailed future study needs to be carried out to understand the sustainability of the Rice nursery Enterprise within the structure of institutions like JEEVIKA. Further understanding of the socio–economic impact of such technology innovation will shed light on the possible avenues of working with small and marginal farmers and improving their livelihood in agriculture. The current study did not have any limitations owing to the purposive angle of the sample. Establishing a direct linkage for the small and marginal farmers, especially women farmers, with direct training and capacity building programs will help them in enhancing their knowledge on improved agriculture practices, promoting sustainability in rice farming and adoption of climate resilient agriculture. Innovations promoting ‘Economic value addition’, like Rice Nursery Enterprise, can be one of the triggering factors which act as a catalyst for the adoption of new, improved technology in rice farming. In recent years, particularly in the field of agriculture, more equitable gender relations have started emerging slowly. It’s a time bound progressive process [37]. A self -help group member of JEEVIKA said, ‘We had additional earnings after doing the Nursery Enterprise in my group. The profit I had from doing a nursery enterprise might look small to the larger world, but I spent that money for paying computer tuition classes for my children. It had a huge value addition for me. I have never seen a computer, but now my children will learn it”.

Acknowledgments

This study was conducted as part of the Cereal Systems Initiative for South Asia (CSISA), a multi-institutional project of the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Centre (CIMMYT), International Rice Research Institute (IRRI), International Food Policy Research and Institute (IFPRI) with funding support from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (BMGF). The authors express their deepest gratitude to Bihar Rural Livelihood Promotion Society, JEEVIKA, for their valuable support while carrying out the activities and study on field. Authors are also grateful and offer deep respect to the several village level self-help groups, men and women farmers for their valuable time and persistent efforts for piloting the concept. The authors also express their deepest appreciation to the technical and field level team of JEEVIKA cadres and CSISA for providing their support in the field moderation and several round of focussed group discussions.

Author Contributions

The conceptualization was done by S.M. and R.K.M. Investigation was done by S.M. and S.G. Methodology and formal analysis were done by S.G. and S.M. Data Curation was done by M.S., Writing—Original Draft Preparation S.M. and S.G.; Review & Editing and Visualization were done by P.C., S.S., and V.K.

Ethics Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

- Individual growers have also been refereed as farmers in this document. Individual growers are those who grew nursery for their own use but did not sell it. [Google Scholar]

- Group entrepreneurs mean those farmers who have undergone the nursery enterprise in group. Here this involved the women farmers of self-help groups operating their business in groups. [Google Scholar]

References

- Agriculture Census 2014. Available online: https://eands.da.gov.in/PDF/Agricultural-Statistics-At-Glance2014.pdf (accessed on 8 October 2020)

- Chand R, Prasanna PL, Singh A. Farm Size and Productivity: Understanding the Strengths of Smallholders and Improving Their Livelihoods. Econ. Political Wkly. 2011, 46, 5–11.

- Bihar Economic Survey 2018–2019. Available online: https://www.adriindia.org/centre/report_details/economic-survey-2018-19-of-government-of-biharenglish- (accessed on 8 November 2020).

- Munshi S. Community Nursery Offers Means for Economic Empowerment of Women. 2016. Available online: https://www.irri.org/news-and-events/news/community-nursery-offers-means-economic-empowerment-women-farmers (accessed on 8 February 2020).

- Jost C, Kyazze F, Naab J, Neelormi S, Kinyangi J, Zougmore R, et al. Understanding gender dimensions of agriculture and climate change in smallholder farming communities. Clim. Dev. 2015, 8, 133–144. DOI:10.1080/17565529.2015.1050978

- FAO. The State of Food and Agriculture 2010–2011. Women in Agriculture: Closing the Gender Gap for Development; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Deere CD. The Feminization of Agriculture? Economic Restructuring in Rural Latin America, UNRISD Occasional Paper, No. 1; United Nations Research Institute for Social Development (UNRISD): Geneva, Switzerland, 2005. ISBN 9290850493. [Google Scholar]

- Munshi S. It’s Time to Recognize and Empower India’s Women Farmers. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/stories/2017/10/indias-women-farmers/ (accessed on 11 November 2020).

- Doss CR. Designing Agricultural Technology for African Women Farmers: Lessons from 25 Years of Experience. World Dev. 2001, 29, 2075–2092. DOI:10.1016/S0305-750X(01)00088-2

- Goh AHX. A Literature Review of the Gender-Differentiated Impacts of Climate Change on Women’s and Men’s Assets and Well-Being in Developing Countries; CAPRi Working Paper No. 106.; International Food Policy Research Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. Available online: https://doi.org/10.2499/capriwp106 (accessed on 8 November 2020).

- Kim H, Sambrook C. The Changing Role of Women in the Economic Transformation of Family Farming in Asia and the Pacific; International Fund for Agricultural Development: Rome, Italy, 2014. Available online: https://www.ifad.org/documents/10180/61297bc5-2280-4381-96b9-330b33a382bb (accessed on 17 June 2016).

- Agarwal B. Gender and command over property: A critical gap in economic analysis and policy in South Asia. World Dev. 1994, 22, 1455–1478. DOI:10.1016/0305-750X(94)90031-0

- FAO. The Gender Gap in Land Rights. 2018. Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/I8796EN/i8796en.pdf (accessed on 6 September 2020).

- Valera HG, Yamano T, Puskur R, Veettil PC, Gupta I, Ricarte P, et al. Women’s Land Title Ownership and Empowerment: Evidence from India. In ADB Economics Working Paper Series No. 559; Asian Development Bank: Manila, Philippines, 2018. DOI:10.22617/WPS189556-2

- Willis K, Yeoh B. Gender and Migration; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2000. DOI:10.12681/grsr.9177 [Google Scholar]

- Datta A, Mishra SK. Glimpses of Women lives in rural Bihar: Impact of male migration. Indian J. Labor Econ. 2011, 54, 457–477. [Google Scholar]

- Bryan E, Behrman J. Community-Based Adaptation to Climate Change: A Theoretical Framework, Overview of Key Issues and Discussion of Gender-Differentiated Priorities and Participation (CAPRi Working Paper 109); International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI): Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kristjanson P, Bryan E, Bernier Q, Twyman J, Meinzen-Dick R, Kieran C, et al. Addressing gender in agricultural research for development in the face of a changing climate: where are we and where should we be going? Int. J. Agric. Sustain. 2017, 15, 482–500. DOI:10.1080/14735903.2017.1336411 [Google Scholar]

- Beuchelt TD, Badstue L. Gender, nutrition- and climate-smart food production: Opportunities and trade-offs. Food Secur. 2013, 5, 709–721. DOI:10.1007/s12571-013-0290-8 [Google Scholar]

- Bernier Q, Meinzen-Dick RS, Kristjanson PM, Haglund E, Kovarik C, Bryan E, et al. Gender and Institutional Aspects of Climate Smart Agricultural Practices: Evidence from Kenya. 2015. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10568/65680 (accessed on 2 February 2020).

- Chayal K, Dhaka BL, Poonia MK, Tyagi SV, Verma SR. Involvement of Farm Women in Decision Making in Agriculture. Stud. Home Com. Sci. 2013, 7, 35–37. DOI:10.1080/09737189.2013.11885390

- Sahu L, Singh SK. A qualitative study on role of self-help group in women empowerment in rural Pondicherry, India. Natl. J. Comm. Med. 2012, 3, 473–479. [Google Scholar]

- Kondal K. Women empowerment through self-help groups in Andhra Pradesh, India. Intl. Res. J. Social Sci. 2014, 3, 13–16. [Google Scholar]

- Sachs C, Barbercheck M, Braiser K, Kiernan NE, Terman AR. The Rise of Women Farmers and Sustainable Agriculture; University of Iowa Press: Iowa City, IA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Caroline PC. Invisible Women, Exposing Data Bias in a World Designed for Men; Chatto & Windus: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Paris R. Women’s Roles and Needs in Changing Rural Asia with Emphasis on Rice-Based Agriculture; Food and Fertilizer Tech- nology Center (FFTC): Taipei, China, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Nazneen S, Hossain N, Chopra D. Introduction: contentious women’s empowerment in South Asia. Contemp. South Asia 2019, 27, 457–470. DOI:10.1080/09584935.2019.1689922 [Google Scholar]

- Ayoola JB, Kudi TM, Dangbegnon C, Daudu CK, Mando A, Amapu IY, et al. Gender Perspective of Action Research for improved Rice Value Chain in Northern Guinea Savanna, Nigeria. J. Agric. Sci. 2011, 4, 211. DOI:10.5539/jas.v4n1p211 [Google Scholar]

- Enete AA, Amusa TA. Determinants of Women’s Contribution to Farming Decisions in Cocoa Based Agroforestry Households of Ekiti State, Nigeria. 2010. Available online: https://journals.openedition.org/factsreports/396 (accessed on 5 November 2020).

- Dhaka BL, Poonia MK, Chayal K, Tyagi SV, Vatta L. Constraints in Knowledge and Information Flow amongst Farm Women. Int. J. Agric. Environ. Biotechnol. 2012, 5, 167–170.

- Seymour G, Doss CR, Marenya P, Meinzen-Dick R, Passarelli S. Women’s Empowerment and the Adoption of Improved Maize Varieties: Evidence from Ethiopia, Kenya, and Tanzania. 2016. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10568/76523 (accessed on 12 September 2020).

- Kumar N, Raghunathan K, Arrieta A, Jilani A, Pandey S. The power of the collective empowers women: Evidence from self-help groups in India. World Dev. 2021, 146, 105579. DOI:10.1016/j.worlddev.2021.105579

- Kandiyoti D. Bargaining with patriarchy. Gend. Soc. 1988, 2, 274–290. DOI:10.1177/089124388002003004 [Google Scholar]

- Ngenzebuke RL. The Returns of ‘I do’: Women Decision-Making in Agriculture and Productivity Differential in Tanzania. 2014. Available online: http://www.worldbank.org/content/dam/Worldbank/Feature%20Story/Africa/afr-rama-lionel-ngenzebuke.pdf (accessed on 18 July 2016).

- Kabeer N. Resources, Agency, Achievements: Reflections on the Measurement of Women’s Empowerment. Dev. Change 2002, 30, 435–464. DOI:10.1111/1467-7660.00125

- Galiè A, Farnworth CR. Power through: A new concept in the empowerment discourse. Glob. Food Secur. 2019, 21, 13–17. DOI:10.1016/j.gfs.2019.07.001 [Google Scholar]

- Brandth B. On the relationship between feminism and farm women. Agric. Hum. Values 2002, 19, 107–117. DOI:10.1023/A:1016011527245 [Google Scholar]