The Role of Empathy in Resource Control Strategy Selection and Social Dominance in Early Childhood

Received: 08 December 2025 Revised: 23 December 2025 Accepted: 30 December 2025 Published: 15 January 2026

© 2026 The authors. This is an open access article under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

1. Introduction

When children start school, the new social environments necessitate the development and deepening of their social behaviors. These behaviors can be viewed as prosocial (e.g., being friendly, cooperation, sharing) or aggressive/coercive (e.g., posturing, physical or verbal attacks). Beyond these general social behaviors, certain behaviors are more specifically directed toward the acquisition or control of valued resources, such as toys, play opportunities, or social attention. Within this functional perspective, Resource Control Theory (RCT) [1,2,3] distinguishes between general social behaviors (prosocial and aggressive) and resource control strategies (RCS), which are the deliberate, goal-oriented behaviors children use to obtain or defend resources. These strategies may be expressed through prosocial means, such as helping, negotiating, or cooperating to achieve shared goals, or through coercive means, including intimidation and exclusion. Thus, while general prosocial and aggressive behaviors reflect a child’s overall social orientation, prosocial and coercive RCS represent the strategic deployment of behavior in situations involving competition for resources.

According to Resource Control Theory (RCT) [3], social dominance refers to the “exercise of chief authority or rule; occupying a commanding position” (p. 323) within dyads and groups, and it emphasizes the role of RCS in establishing social dominance hierarchies. Whereas prior views of social dominance saw aggression as the key driver of social dominance hierarchies [4,5,6], RCT also incorporates prosocial strategies into the dominance framework [7,8,9,10,11,12], viewing social dominance as resulting from an individual’s successful control of resources, regardless of the means by which it was achieved. Indeed, Pellegrini and colleagues found that socially dominant preschool children display increasing prosocial strategies and an increase in sociometric ratings over time [13,14,15]. In this way, RCT conceptualizes social dominance not as a trait but as a flexible, strategy-based process that enables children to achieve social goals and negotiate power dynamics within their peer groups.

A central theoretical distinction within RCT [1,2,3] concerns the differentiation between (a) resource control strategies, (b) resource control success, and (c) social dominance, which represent related but non-equivalent constructs. Resource control strategies (RCS) refer to the behaviors children deliberately use to influence access to resources. In contrast, resource control success refers to the effectiveness of these strategies, indexed by the extent to which children obtain desired resources during peer interactions. Resource control success, therefore, represents an outcome of strategy use rather than a strategy itself. Social dominance reflects a broader, higher-order social status construct, describing a child’s recognized influence within the peer group, which is theorized to emerge over time from repeated patterns of effective resource control. Accordingly, RCS are conceptualized as behavioral predictors, resource control success as an intermediate outcome of strategy use, and social dominance as a subsequent social outcome.

Whilst the behaviors and strategies that result in resource control have been empirically described, potential cognitive correlates are scarcely researched. Pellegrini et al. [14] found that theory of mind, which is the ability to infer the mental states of others [16], was associated with social dominance in 2–4-year-olds. However, the measure of theory of mind used did not address emotion understanding or empathy, which may be another predictor of resource control. Empathy is a highly complex affective-cognitive construct that goes through substantial development during early childhood [17,18,19]. It comprises both affective empathy (the ability to share another’s emotions) and cognitive empathy (the ability to understand another’s emotional state) [20]. Although related, these components show different developmental trajectories [21,22,23]. Affective empathy emerges within the first three years of life, while cognitive empathy develops later and increases alongside theory-of-mind abilities [24].

Although a range of socio-emotional abilities may shape children’s behavior in peer contexts, empathy is particularly relevant for extending RCT because it helps explain why children differ in their use of prosocial and coercive strategies. RCT describes the behavioral routes through which children gain influence, but it does not address the socio-emotional skills that guide children’s choices between these strategies. Affective empathy may increase children’s awareness of others’ emotions, making prosocial approaches more likely, whereas cognitive empathy may allow children to anticipate others’ reactions and adjust their behavior strategically. Empathy is therefore theorized to influence strategy selection rather than functioning as a direct determinant of resource control success or social dominance. These developmental perspectives on empathy [19,24] highlight how emotional understanding and perspective-taking contribute to children’s social decisions. Although other socio-emotional skills may also influence strategy use, empathy is especially pertinent because it directly relates to how children interpret social situations and adjust their behavior, accordingly, thereby enriching RCT’s ability to account for variability in children’s strategic behavior.

Within the framework of RCT, strategic behavior requires not only motivation to obtain resources but also the capacity to anticipate others’ reactions, evaluate alternative courses of action, and regulate emotional responses in competitive social contexts [2,3]. From this perspective, cognitive empathy is particularly relevant because it enables children to represent and predict others’ emotional states, thereby providing a cognitive basis for selecting flexible and goal-directed strategies. By understanding how peers are likely to feel or respond, children can adjust their behavior to maximize the effectiveness of prosocial or coercive strategies, which aligns closely with RCT’s emphasis on adaptive, context-sensitive resource control [13,14]. Although other social–cognitive abilities, such as theory of mind, are also implicated in strategic social behavior [16,24], empathy constitutes a uniquely integrative construct because it combines emotional sensitivity with cognitive appraisal [18,19,20,21]. Affective empathy heightens awareness of others’ emotional states, while cognitive empathy supports the regulation and strategic application of this emotional information, allowing children to balance concern for others with self-interested goals. This dual-component structure makes empathy particularly well-suited to explaining individual differences in children’s selection and deployment of resource control strategies. Drawing on Hoffman’s developmental theory of empathy [19], the present study conceptualizes cognitive empathy as a regulatory mechanism that can modulate affective arousal, a process originally proposed in the context of moral development but equally relevant to competitive peer interactions. When integrated with social information-processing accounts of social behavior [25], this perspective suggests that empathy may function not only as a moral capacity but also as a social–cognitive resource that supports strategic behavior within the competitive dynamics described by RCT.

Positive associations between cognitive and affective empathy and prosocial behavior have been well-documented in both children and adults [17,26]. More recent evidence also underscores the role of empathy in shaping positive social behaviors in early childhood. For instance, Güngördü et al. [27] found that among children aged 3–5, cognitive empathy significantly predicted both prosocial decision-making and prosocial creativity, suggesting that even at the preschool level, children may draw on their understanding of others’ emotions to guide socially adaptive responses. Interestingly, the role of empathy in RCS, particularly in relation to the use of prosocial and coercive RCS, remains unexplored. This represents a critical gap in the literature, given that RCS directly influences children’s social standing within peer groups.

Hawley and Geldhof [28] reported that preschoolers who frequently used both prosocial and coercive RCS, the so-called bistrategic controllers, were rated by teachers as more socially dominant but as showing lower levels of moral functioning. This pattern suggests that such children may possess social-cognitive and emotional skills that enable them to recognize and influence others’ emotions and intentions, but may not always apply these skills toward prosocial ends. In other words, emotional and cognitive sophistication can underpin both cooperative and manipulative behaviors. This interpretation provides a stronger conceptual bridge between moral functioning, emotional understanding, and empathy, highlighting that empathy-related abilities can support either prosocial or self-serving strategies in social contexts. Evidence from older children (10–12 years) indicates that general empathy predicts fairness-related decisions in resource allocation tasks [29]; however, much less is known about how the affective and cognitive components of empathy jointly shape RCS use and social dominance in younger children.

Building on this behavioral account, integrating empathy into RCT provides a theoretically grounded explanation for how children regulate and select prosocial or coercive strategies during competitive peer interactions. According to RCT [2,3], social dominance emerges from children’s ability to control access to valued resources through both prosocial and coercive RCS. While RCT provides a robust behavioral account of how social influence is achieved, it does not explicitly address the emotional and cognitive processes that guide the selection and regulation of these strategies. Empathy offers a useful extension to this framework by capturing the affective and cognitive capacities that shape how children perceive and respond to others during social exchanges. Affective empathy may motivate prosocial influence by fostering concern for others’ emotions, whereas cognitive empathy may allow children to anticipate others’ reactions and use this understanding strategically. Integrating empathy within RCT, therefore, provides a more comprehensive model of social dominance, linking the behavioral expression of RCS to the underlying emotional and cognitive mechanisms that inform them.

Hoffman’s developmental theory of empathy [19] provides a useful framework for understanding how affective and cognitive empathy interact to shape children’s social behaviors. Affective empathy (the capacity to share another’s emotional state) may motivate prosocial behaviors that foster cooperation and affiliation [17], while cognitive empathy (the capacity to understand another’s emotional perspective) can regulate and refine these emotional responses [19]. The balance between emotional arousal and cognitive understanding may therefore determine whether a child employs prosocial or coercive tactics. For example, children high in both affective and cognitive empathy may be more inclined toward prosocial strategies that balance self-interest with others’ needs, whereas those high in affective but low in cognitive empathy may act more impulsively, relying on coercive means. Although empathy is typically viewed as prosocial, it can also be used strategically or manipulatively when combined with advanced perspective-taking skills. Integrating this dual process view of empathy within RCT provides a more comprehensive explanation of how emotional and cognitive mechanisms contribute to individual differences in social dominance and resource control.

The present study, therefore, examined how affective and cognitive empathy relate to children’s use of prosocial and coercive RCS, how these strategies predict resource control success, and how strategy use and resource control success jointly contribute to social dominance. Consistent with RCT, resource control success was examined as an outcome of strategy use and as a proximal contributor to social dominance, rather than as a behavioral predictor. Additionally, we examined whether cognitive empathy moderates the association between affective empathy and RCS selection. Based on previous findings and theoretical reasoning, this study addressed three main research questions: whether affective and cognitive empathy are associated with children’s use of prosocial and coercive RCS; whether empathy, general social behaviors (prosocial and aggressive), and RCS relate to children’s RC success and social dominance; and whether cognitive empathy moderates the relationship between affective empathy and RCS selection. In line with prior work, we anticipated that affective empathy would show a positive association with prosocial RCS, given its links to cooperative and prosocial behavior [17,26]. We also explored whether cognitive empathy moderates the association between affective empathy and the use of coercive strategies, as suggested by developmental models proposing that cognitive understanding can regulate or amplify emotional responses [19]. Furthermore, we expected that prosocial RCS would be related to greater RC success, while both prosocial and coercive RCS were expected to be associated with higher social dominance [2,14,28]. Finally, we anticipated that general prosocial behavior would show a positive association with children’s social dominance and RC success, while aggressive behaviors would show a negative association.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

Ninety-two 4–5-year-old children (M age = 4.64, SD age = 0.29) were recruited from four UK-based reception classes (US equivalent Preschool & Kindergarten) from three state-funded primary schools in the southeast of England (males, n = 47; females, n = 45). All participating schools served urban and suburban catchment areas representing predominantly middle socioeconomic backgrounds, as determined by parental occupation and educational data provided by the schools. Approximately 68% of parents held a post-secondary qualification, and 72% were employed in skilled or professional occupations. None of the participants had received a diagnosis for attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), autism spectrum disorder (ASD), conduct disorder, or a learning disability; however, one child was diagnosed with sight impairment, and one child was registered as deaf and was equipped with a hearing aid. In both cases, each child did not seem to struggle with any of the tasks. Six children spoke English as a second language. Participation rates for the four classes were 73%, 73%, 76% and 80%. Parental or carer consent and child assent were obtained.

Teachers from each classroom (N = 4; all female) also participated in the study by completing the teacher-report measures for the children in their respective classes, as described below.

Post hoc power estimation using G Power indicated that the final sample (N = 92) provided adequate power (>0.80) to detect medium effect sizes (f2 = 0.15, α = 0.05) in the regression analyses.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Teacher-Rated Child Behavior Report

Teachers completed a child behavior questionnaire for each child in their classroom individually. This questionnaire contained five items relating to dominance (α = 0.80) on a five-point scale [30], three items relating to relational aggression (α = 0.81) and three relating to overt aggression (α = 0.83) on a four-point scale [31] and four items relating to prosocial behavior (α = 0.86) on a five-point scale [32]. In addition, 18 resource control-related items, on a seven-point Likert scale, were taken from the questionnaire used by Hawley [3] and Hawley and Geldhof [28] and added to the questionnaire in order to provide specific data regarding prosocial (six items; α = 0.74) and coercive (six items; α = 0.87) RCS as well as items regarding resource control success (six items; α = 0.85). Therefore, in total the questionnaire was composed of 33 items. Items were scored numerically according to the scale from which they originated, e.g., social dominance items (a seven-point Likert scale) were scored between 1 (strongly disagree) and 7 (strongly agree). Items included “this child… gets what s/he wants by ‘helping’ others (even if they don’t really need it)” (prosocial RCS); “… makes others follow his/her plans to gets what s/he want” (coercive RCS); “… usually gets what s/he wants when with peers” (resource control success); “… is a leader” (social dominance); “… is kind to peers” (non-resource-specific general prosocial behavior); “… fights with others” (non-resource-specific aggressive behavior).

2.2.2. Child-Reported Empathy Assessment

The Empathy Test for Preschoolers (EMP) [33] was used to assess children’s cognitive and affective empathy. The EMP is a storybook measure of cognitive and affective empathy, comprising eight short, three-part vignettes. Four vignettes feature a child as the protagonist, and four vignettes feature a dog as the protagonist, with the protagonists not being identified as any gender in name or appearance. Similar to other measures of empathy [34], the vignettes are designed to evoke happiness, sadness, fear, and anger. Each vignette consists of three pages, featuring a colored illustration and accompanying brief narrative text. As per the official EMP guidance notes, affective empathy was assessed by asking children, “How do you feel after hearing this?”. This question was asked first, followed by the cognitive empathy assessment question, “How does the child/dog feel about this?”. Responses to these questions were coded on a scale of 0–4.

Scoring was also conducted according to the official guidance, which provided an extensive list of response words associated with each score. A score of 4 was given for a response exactly matching the emotion portrayed in the vignette. A score of 3 was given for responses that were similar to the displayed vignette emotion, but did not match precisely (e.g., “upset” instead of “angry”). A score of 2 was given for responses naming a related emotion to the displayed vignette emotion, but not one that was similar (e.g., “not good” instead of angry). A score of 1 was given if the child gave a verbal response to the question, provided that this response was in some way appropriate to the displayed vignette emotion. For example, this could be the child referring to a time in their own lives when something similar happened to them. A score of 0 was given if the child gave no response, responded entirely inappropriately, or referred to something completely unrelated (e.g., saying that they are going to the cinema that weekend).

Mean cognitive and affective empathy scores were computed to represent the empathy of each child. The order of the vignettes and questions was counterbalanced. The internal consistency reliability for this measure is acceptable (Spearman-Brown coefficient = 0.976).

2.2.3. Verbal Ability

Children’s receptive vocabulary was measured with the British Picture Vocabulary Scale III (BPVS III) [35]. Children were asked to select the picture (from four options) that best matched the word. Verbal ability was included as a control variable to account for variance in social and empathic measures related to language skills.

2.3. Procedure

The University’s Research Ethics Committee approved the research. The present study was based on data from the first phase of a longitudinal investigation into the cognitive and behavioral factors associated with strategy selection, resource control, and social dominance in children over the first year at school. The present analyses are based on cross-sectional data collected at the first wave of a larger longitudinal project.

Consent for child participation was obtained from parents/carers, and assent was obtained from children. Teachers consented to their own participation. Data collection was conducted at the beginning of the children’s first school year (Reception Year in the UK). Teachers were asked to complete their tasks by the end of the data collection phase with their class. Data collection with each class occurred within two weeks. Children were seen individually in a quiet area of the school. Teacher responses were gathered via the ‘anonymous link’ function of the Qualtrics survey software.

2.4. Data Analysis

All analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics (Version 24). Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations were first computed to examine associations among all study variables. Because measures differed in scale format (4-, 5-, and 7-point Likert scales), all continuous variables were standardized (z-scores) prior to inclusion in the regression analyses. Two hierarchical multiple regression analyses were then performed to examine (a) predictors of resource control (RC) success and (b) predictors of social dominance as a distinct social status outcome. Predictors were entered hierarchically: Block 1 contained verbal ability, affective and cognitive empathy, and their interaction term. Verbal ability and empathy were entered in Block 1 because they develop earlier than broader social behaviors and strategic responses and are shown in developmental and social-information-processing research to shape children’s interpretation of social cues before behavioral decisions are made [19,25,35]. Block 2 included prosocial behavior and aggressive behaviors (overt and relational); Block 3 added prosocial and coercive resource control strategies (RCS). In the RC success model, RCS were treated as behavioral predictors and RC success as the outcome variable. For the social dominance model, RC success was entered as a final block to test its incremental contribution beyond empathy, general social behaviors, and strategy use. General prosocial and aggressive behaviors were entered in Block 2 because they represent broad social tendencies that build upon earlier-developing socio-cognitive skills and are theorized to influence, but remain distinct from, the more targeted strategic behaviors captured by RCS [1,25]. Prosocial and coercive RCS were entered in Block 3 because RCT identifies these strategies as the proximal, goal-directed behaviors most directly responsible for children’s resource control success and social dominance [1,13]. RC success was entered last in the social dominance model because RCT conceptualizes it as an outcome of children’s strategy use that functions as a proximal contributor to their dominant standing within the peer group, rather than as a behavioral predictor [13,14].

To further explore the role of empathy, additional multiple regression analyses were subsequently conducted to examine affective and cognitive empathy (and their interaction) as predictors of prosocial and coercive RCS. These analyses allowed for a direct test of whether empathy independently or interactively explained variation in children’s strategic behavior. All continuous predictors were mean-centered before computing interaction terms to minimize multicollinearity. Regression assumptions (linearity, normality, and homoscedasticity) were examined and found to be adequately met. The term “predict” is used in a statistical sense to denote variance explained in the outcome variables, not temporal or causal inference.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptives and Correlations

We first present the descriptive statistics and correlations (Table 1). Preliminary correlation analysis results indicated that verbal ability was positively correlated to several behavioral variables (prosocial behavior, overt aggressive behavior, and relational aggressive behavior) and cognitive empathy. Further correlation analysis is therefore reported with verbal ability partialled out. Gender was dummy coded: males = 1 and females = 2.

As shown in Table 1, strong positive correlations were found among social dominance, resource control success, prosocial RCS, and coercive RCS. Both overt and relational aggression were strongly positively associated with coercive RCS and, to a lesser extent, with prosocial RCS. General prosocial behavior was negatively correlated with overt and relational aggression, as well as with coercive RCS, and showed a smaller negative association with prosocial RCS. Affective empathy demonstrated moderate positive correlations with social dominance, both types of RCS, and cognitive empathy. Cognitive empathy was moderately and positively associated with affective empathy.

Table 1. Means, standard deviations, and intercorrelations among study variables (verbal ability partialled out).

|

Variable |

M |

SD |

Min |

Max |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

11 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1. Gender |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

−0.027 |

−0.006 |

0.044 |

0.072 |

0.030 |

−0.030 |

−0.163 |

0.030 |

−0.033 |

0.027 |

|

2. Age (years) |

4.64 |

0.29 |

4.08 |

5.17 |

– |

0.018 |

0.035 |

−0.100 |

−0.095 |

0.083 |

−0.012 |

−0.042 |

0.014 |

−0.073 |

|

|

3. Social dominance |

2.62 |

0.87 |

1.00 |

4.75 |

– |

0.647 *** |

0.777 *** |

0.651 *** |

−0.270 * |

0.302 ** |

0.374 *** |

0.400 *** |

0.064 |

||

|

4. RC success |

3.61 |

1.86 |

1.00 |

7.00 |

– |

0.693 *** |

0.397 *** |

−0.327 ** |

0.095 |

0.263 * |

0.208 |

−0.097 |

|||

|

5. Prosocial RCS |

3.62 |

1.40 |

1.00 |

6.33 |

– |

0.709 *** |

−0.496 *** |

0.351 ** |

0.527 *** |

0.441 *** |

0.116 |

||||

|

6. Coercive RCS |

2.05 |

0.93 |

1.00 |

5.17 |

– |

−0.593 *** |

0.671 *** |

0.688 *** |

0.374 *** |

0.199 |

|||||

|

7. Prosocial behavior |

3.57 |

0.82 |

1.50 |

5.00 |

– |

−0.647 *** |

−0.625 *** |

−0.215 |

−0.092 |

||||||

|

8. Overt aggression |

1.26 |

0.49 |

1.00 |

3.00 |

– |

0.675 *** |

0.161 |

0.083 |

|||||||

|

9. Relational aggression |

1.33 |

0.53 |

1.00 |

3.00 |

– |

0.202 |

0.134 |

||||||||

|

10. Affective empathy |

2.85 |

0.94 |

0.00 |

4.00 |

– |

0.397 *** |

|||||||||

|

11. Cognitive empathy |

3.42 |

0.51 |

0.63 |

4.00 |

– |

Note. M = mean; SD = standard deviation; RC = resource control; RCS = resource control strategy. * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001.

3.2. Factors Influencing Resource Control Success and Social Dominance

Subsequently, data were analyzed using two hierarchical multiple regression models to examine statistical predictors of (a) resource control (RC) success, and (b) social dominance. For each outcome, predictors were entered in blocks reflecting theoretical precedence: Block 1 included verbal ability (as a control), affective empathy, cognitive empathy, and their interaction term. In subsequent blocks, prosocial behavior and aggressive behaviors (overt & relational) were added, followed by prosocial and coercive RCS. For the social dominance model, RC success was entered in the final block to assess its incremental contribution beyond empathy, behaviors, and strategies.

Hierarchical multiple regression analysis was first conducted to examine statistical predictors of RC success. In Block 1, affective empathy was a significant positive predictor, β = 0.21, p = 0.037, accounting for 4% of the variance, R2 = 0.04, F(1, 103) = 4.46, p = 0.037. The affective × cognitive empathy interaction was also tested in Block 1, but it did not significantly predict RC success, ΔR2 < 0.01, F(1, 102) = 0.84, p = 0.362. After entering prosocial behaviors and aggressive behaviors in Block 2, the model explained 19% of the variance, ΔR2 = 0.15, F(3, 101) = 7.75, p < 0.001. In this model, affective empathy was no longer significant, while prosocial behavior negatively predicted resource control success, β = −0.33, p = 0.003. In Block 3, the addition of prosocial and coercive RCS substantially improved model fit, with the model explaining 52% of the variance, ΔR2 = 0.33, F(5, 99) = 21.50, p < 0.001. Prosocial RCS was the strongest predictor, β = 0.63, p < 0.001, while coercive RCS was non-significant. The final model, therefore, highlighted prosocial RCS as the most robust predictor of children’s RC success (Table 2).

A second hierarchical multiple regression analysis was conducted to examine predictors of social dominance. In Block 1, verbal ability, β = 0.30, p = 0.002, and affective empathy, β = 0.24, p = 0.017, were significant positive predictors, together explaining 18% of the variance, R2 = 0.18, F(2, 102) = 11.14, p < 0.001. The affective × cognitive empathy interaction was also entered at Block 1, but it did not significantly contribute to the prediction of social dominance at this stage, ΔR2 = 0.02, F(1, 101) = 1.79, p = 0.184. The addition of prosocial and aggressive behaviors in Block 2 improved model fit to 33% explained variance, ΔR2 = 0.15, F(4, 100) = 12.39, p < 0.001, with verbal ability (β = 0.29, p = 0.003) and affective empathy (β = 0.21, p = 0.026) remaining significant. In Block 3, the addition of prosocial and coercive RCS further improved model fit to 63% explained variance, ΔR2 = 0.30, F(6, 98) = 27.44, p < 0.001, with prosocial RCS (β = 0.41, p < 0.001) and coercive RCS (β = 0.23, p = 0.004) both significant predictors. Importantly, the interaction between affective and cognitive empathy became significant, explaining an additional 12% of the variance, ΔR2 = 0.12, F(1, 101) = 7.16, p = 0.009. In Block 4 (Table 2), the inclusion of RC success further improved model fit, with the model explaining 70% of the variance, ΔR2 = 0.07, F(7, 97) = 32.22, p < 0.001. Resource control success was a significant predictor (β = 0.29, p = 0.001), alongside prosocial RCS (β = 0.37, p < 0.001), coercive RCS (β = 0.20, p = 0.008), and general prosocial behavior (β = 0.19, p = 0.013) (Table 2). Full block-by-block regression models are available in Table S1 (Supplementary Materials).

Table 2. Final hierarchical regression models predicting resource control success and social dominance.

|

Predictor |

Resource Control Success |

Social Dominance |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

B |

SE β |

β |

95% CI |

B |

SE B |

β |

95% CI |

|

|

Verbal ability |

0.18 |

0.10 |

0.17 |

[−0.03, 0.39] |

0.20 * |

0.09 |

0.19 |

[0.04, 0.39] |

|

Affective empathy |

−0.09 |

0.10 |

−0.09 |

[−0.26, 0.14] |

0.08 |

0.07 |

0.08 |

[−0.07, 0.22] |

|

Cognitive empathy |

−0.13 |

0.10 |

−0.12 |

[−0.35, 0.04] |

−0.07 |

0.09 |

−0.07 |

[−0.25, 0.10] |

|

Prosocial RCS |

0.63 *** |

0.12 |

0.66 |

[0.43, 0.88] |

0.37 * |

0.14 |

0.33 |

[0.13, 0.70] |

|

Coercive RCS |

0.08 |

0.16 |

0.08 |

[−0.25, 0.37] |

0.29 * |

0.13 |

0.26 |

[0.03, 0.54] |

|

Prosocial behavior |

— |

— |

— |

— |

0.24 ** |

0.09 |

0.23 |

[0.07, 0.43] |

|

RC success |

— |

— |

— |

— |

0.40 ** |

0.09 |

0.38 |

[0.21, 0.58] |

|

Model fit |

F = 10.33 ***, adj. R2 = 0.52 |

F = 19.57 ***, adj. R2 = 0.70 |

Note. RC = Resource Control; RCS = Resource Control Strategy. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001. Full block-by-block regression coefficients are available in Table S1 (Supplementary Materials).

3.3. Empathy as a Predictor of Resource Control Strategy

A multiple regression analysis examined empathy as a predictor of prosocial and coercive RCS (Table 3). For prosocial RCS, the final model was significant, F(4, 87) = 4.62, p = 0.001, adj. R2 = 0.14, with affective empathy emerging as the only significant predictor (β = 0.46, 95% CI [0.25, 0.67], p < 0.001). Verbal ability and cognitive empathy were non-significant. For coercive RCS, the final model was also significant, F(4, 83) = 4.62, p = 0.005, adj. R2 = 0.12. Affective empathy (β = 0.31, 95% CI [0.16, 0.49], p < 0.01) and the affective × cognitive empathy interaction (β = 0.19, 95% CI [0.001, 0.37], p < 0.05) were significant predictors, whereas verbal ability and cognitive empathy as main effects were non-significant. These results suggest that affective empathy directly supports prosocial RCS, while in combination with cognitive empathy, it may also facilitate coercive RCS.

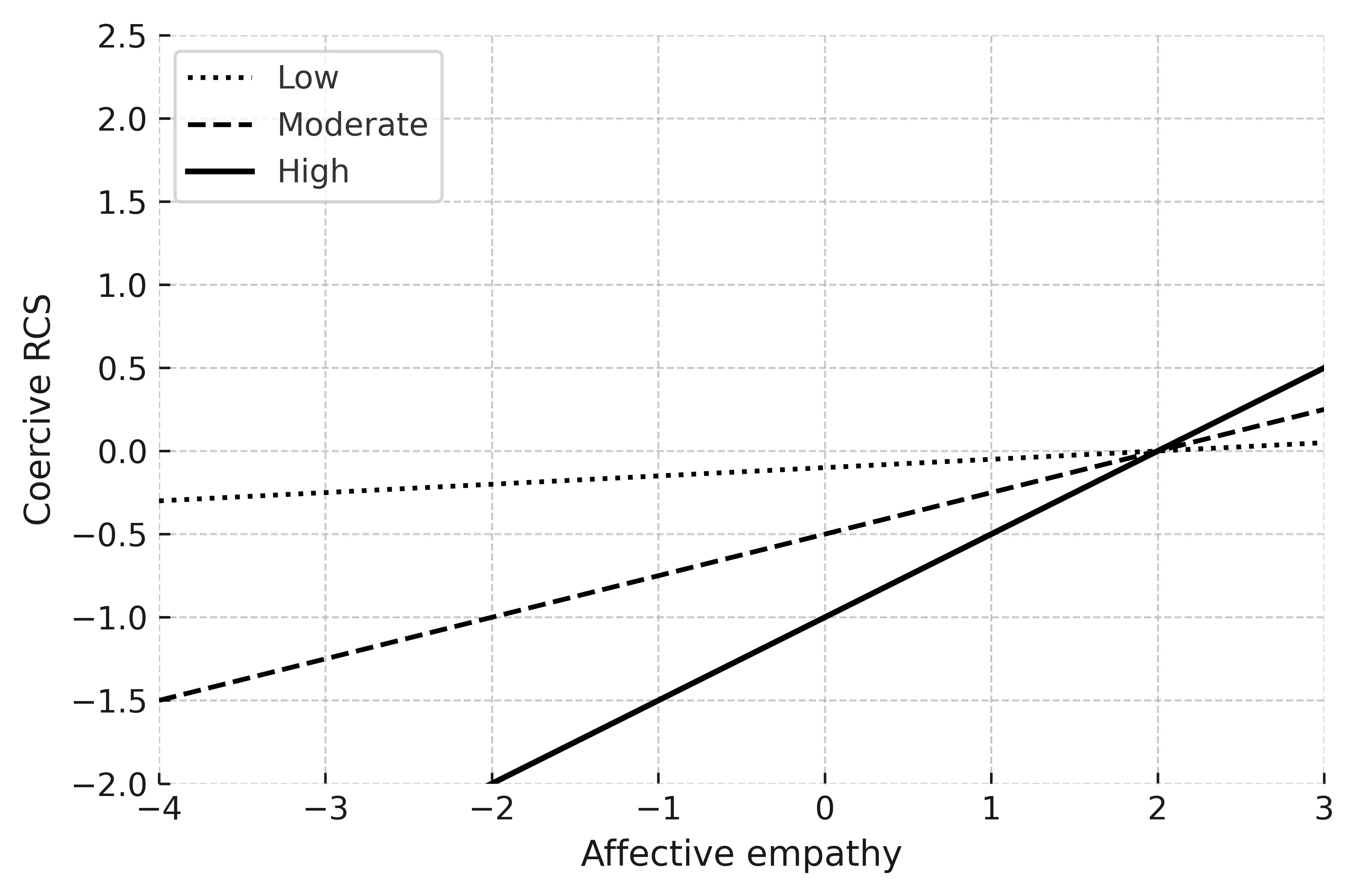

To investigate these interactions further, children were split into three groups according to standard deviations from the cognitive empathy score mean for the sample overall (low group = score ≤ 1 SD, high group ≥ 1 SD, average group = within 1 SD). A regression with affective empathy (predictor) and coercive RCS (outcome) was carried out for each cognitive empathy group. For children scoring low or average in cognitive empathy, there was no significant relationship between affective empathy and coercive RCS, β = 0.54, t(31) = 0.312, p = 0.770, and β = 0.245, t(24) = 1.14, p = 0.183, respectively. However, a significant effect of affective empathy was found for the group high in cognitive empathy, β = 0.39, t(31) = 2.14, p = 0.009 (Figure 1).

Table 3. Multiple regression examining empathy as a predictor of prosocial and coercive resource control strategies.

|

Predictor |

β |

SE β |

95% CI |

F |

adj. R2 |

p |

β |

SE β |

95% CI |

F |

adj. R2 |

p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Prosocial RCS |

Coercive RCS |

|||||||||||

|

Block 1 |

0.43 |

0.00 |

0.98 |

0.00 |

||||||||

|

Verbal ability |

−0.069 |

0.101 |

[−0.291, 0.114] |

n.s. |

−0.106 |

0.118 |

[−0.307, 0.164] |

n.s. |

||||

|

Block 2 |

4.62 ** |

0.14 |

4.00 ** |

0.12 |

||||||||

|

Verbal ability |

−0.080 |

0.127 |

[−0.345, 0.172] |

n.s. |

−0.089 |

0.129 |

[−0.323, 0.189] |

n.s. |

||||

|

Affective empathy |

0.463 *** |

0.105 |

[0.248, 0.668] |

<0.001 *** |

0.313 ** |

0.086 |

[0.160, 0.494] |

<0.01 ** |

||||

|

Cognitive empathy |

−0.105 |

0.153 |

[−0.427, 0.174] |

n.s. |

0.062 |

0.135 |

[−0.199, 0.334] |

n.s. |

||||

|

Affective × cognitive empathy |

0.043 |

0.091 |

[−0.130, 0.256] |

n.s. |

0.193 * |

0.091 |

[0.001, 0.369] |

<0.05 * |

Note. Values are standardized regression coefficients (β) with standard errors and 95% confidence intervals. Final model fit: Prosocial RCS, F(4, 87) = 4.62, p = 0.001, adj. R2 = 0.14; Coercive RCS, F(4, 83) = 4.00, p = 0.005, adj. R2 = 0.12. * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001; n.s. = not significant.

Figure 1. Moderation of the association between affective empathy and coercive resource control strategy (RCS) by cognitive empathy. Lines represent children low, moderate, and high in cognitive empathy (±1 SD). Axes display standardized values. p < 0.01.

4. Discussion

The present study examined the associations between RCS, resource control success, and social dominance in preschool children, and investigated the roles of affective and cognitive empathy in the use of these strategies. Framed within RCT [2,28,32], the findings explain the emotional and cognitive factors associated with peer influence in early childhood. The results contribute to a more detailed understanding of how children acquire and maintain social dominance at this age.

Both prosocial and coercive RCS were positively associated with resource control success and social dominance. Children who used strategies more flexibly were more likely to gain influence within their peer group, a finding that agrees with prior work [14,28]. Importantly, resource control success was related to social dominance, consistent with RCT. In contexts where access to toys, attention, or space is limited, children who consistently secure resources may be seen as more capable or assertive, thereby enhancing their social standing.

Interestingly, prosocial behavior was negatively correlated with both prosocial and coercive RCS, suggesting that everyday kindness and cooperation are not necessarily linked to strategic behaviors aimed at resource acquisition. This distinction highlights the functional specificity of RCS; while prosocial behaviors serve to maintain group cohesion, RCS are targeted, goal-directed, and often competitive. Such a distinction underscores the Machiavellian nature of resource control [2,3], in which RCS, whether prosocial or coercive, are selected to maximize personal gain rather than to reflect broader social competence.

Results revealed that prosocial RCS significantly predicted success in resource control, whereas coercive RCS did not. This contrasts with earlier research on younger preschoolers [13,14], where coercion often facilitated the acquisition of resources. Developmental factors may explain this discrepancy; the children in the present sample were older compared (4–5 years old) to samples in the aforementioned studies (2–5-years old). At 4–5 years of age, when they begin formal schooling, they may already be shifting away from coercion toward more socially acceptable strategies. School environments, with structured rules and adult monitoring, may also constrain coercive RCS while reinforcing prosocial ones. Thus, prosocial RCS may not only be more effective but also more sustainable in such contexts, aligning with research showing that cooperative strategies promote positive peer relationships and peer acceptance [36].

When predicting social dominance, however, both prosocial and coercive RCS made unique contributions, even after controlling for RC success. This supports RCT’s claim that multiple behavioral pathways can lead to influence [2]. Coercive RCS may enhance visibility, instill compliance, or project strength, even if they do not directly secure resources. In contrast, prosocial RCS may generate social capital by fostering goodwill and cooperation, making children more attractive partners and leaders. The contribution of general prosocial behavior further emphasizes that social dominance is not solely resource-driven but also shaped by behaviors that sustain group cohesion and peer approval [37]. Together, these findings indicate that social dominance in early childhood reflects a dynamic interplay of RC success, RCS, and general prosociality.

The role of empathy added further complexity. Affective empathy was positively associated with both prosocial and coercive RCS, suggesting that children sensitive to others’ emotions may engage in influence behaviors of various kinds. This expands traditional views of empathy as purely prosocial [17,38], indicating that empathic sensitivity can also enable coercive tactics when social competition is salient. Cognitive empathy, on its own, did not predict coercive RCS; however, the interaction between affective and cognitive empathy revealed that affective empathy predicted greater coercive RCS use only among children high in cognitive empathy. This finding aligns with Hoffman’s theory of empathy and moral development [19], which posits that empathy serves both as an emotional motivator for prosocial behavior and as a moral regulator that can be shaped or distorted by cognitive appraisal. Children with advanced perspective-taking may thus be capable of transforming empathic insight into goal-directed, strategic action.

The findings also correspond closely with Crick and Dodge’s [25] social information-processing (SIP) model, which describes how children encode, interpret, and respond to social cues. Within this framework, empathy may influence both the encoding of emotional information and the selection of behavioral responses. For example, affective empathy can heighten awareness of others’ emotions, while cognitive empathy supports the evaluation of possible responses and their anticipated outcomes. In some children, this processing sequence may culminate in prosocial acts aimed at restoring fairness or harmony; in others, particularly those with competitive goals, it may facilitate the use of empathy-based insight to manipulate peers or control resources. Integrating the dual potential of empathy within these two frameworks helps to explain how empathy can function as both a moral compass and a strategic tool in early social interactions.

Taken together, these findings highlight the dual potential of empathy in early peer relations. While empathy can promote cooperation and social harmony, it can also serve strategic or self-serving functions when combined with advanced cognitive perspective-taking. Within both Hoffman’s theory [18] and Crick and Dodge’s SIP [25] model, this duality reflects an interaction between emotion and cognition, where empathic concern and moral understanding intersect with goal-oriented reasoning. Empathy thus provides the affective information necessary for moral sensitivity but also the cognitive means through which social goals can be strategically pursued. Recognizing this dual potential reframes empathy as a socially flexible mechanism rather than a purely prosocial disposition.

Our findings have several implications for practice. Given empathy’s functional flexibility, interventions should focus not only on enhancing empathic ability but also on guiding how it is applied in everyday peer interactions. Effective empathy training in early childhood should integrate emotion knowledge, perspective-taking, self-regulation, and moral reasoning to ensure that empathy is used constructively. Educators can promote accurate emotion recognition and empathic concern through brief, discussion-based activities and story-based exercises that link understanding others’ feelings with cooperative goals such as fairness and inclusion. Supporting self-regulation through mindfulness and emotion control techniques can help children manage arousal and inhibit coercive reactions, while explicit teaching of non-coercive influence strategies, such as negotiation, collaboration, and seeking adult help, provides functional alternatives to manipulation. Emphasizing moral reasoning and classroom norms related to fairness, kindness, and consent, together with teacher modeling and ongoing monitoring, can further ensure that empathy development fosters cooperation, inclusivity, and socially responsible influence. In this way, empathy can be cultivated not merely as an emotional capacity but as a morally guided and self-regulated social skill.

Despite its contributions, this study is not without limitations. Several limitations should be noted. First, the cross-sectional design of the study precludes conclusions about causal relations or developmental directionality among empathy, resource control strategies, resource control success, and social dominance. Longitudinal research is required to examine how these associations unfold over time. One limitation is the lack of observational data, with the study relying on one member of staff for the behavioral reports. In addition, social dominance was assessed using teacher reports, which provide valuable and ecologically valid observations across multiple peer interactions but may differ from children’s own perceptions or peer-based assessments. Future studies would benefit from combining teacher reports with peer nominations or observational methods to capture multiple perspectives on children’s social standing. Another limitation concerns the measurement context of the study variables. Empathy was assessed using a story-based task designed to capture children’s affective and cognitive understanding of others’ emotions, whereas resource control strategies and social dominance were assessed via teacher reports of children’s behavior in real peer interactions. These approaches may differ in levels of emotional engagement and motivational relevance compared to live resource competition situations, potentially influencing how empathic processes are expressed. In addition, the present study did not include measures of executive functioning, such as inhibitory control or cognitive flexibility, which are known to contribute to emotional regulation, impulse control, and strategic behavior in social contexts. The absence of executive function measures may limit the extent to which the unique role of empathy can be isolated. Future research would benefit from integrating executive function assessments alongside empathy measures to provide a more comprehensive account of the cognitive and regulatory processes underlying children’s resource control strategy selection. Future studies should endeavor to collect behavioral data from the child’s classroom setting, along with cognitive and affective measures, to more accurately address the question of how these factors affect resource control strategy in real-world terms. Future research should also endeavor to use empathy measures that are based on realistic resource control contest scenarios where the child would be more likely to use empathic cognition relevant to real-world resource control contests. Another limitation is that the two RCS dimensions were examined as separate behavioral phenomena. Further research could explore how empathy affects how children use a combination of coercive and prosocial RCS in resource contest situations.

5. Conclusions and Implications

This study extends RCT by incorporating empathy’s emotional and cognitive components into the explanation of how young children attain and maintain social influence. The results demonstrate that affective and cognitive empathy, both independently and interactively, contribute to the use and effectiveness of RCS. Empathy’s dual potential, to foster inclusion or facilitate manipulation, emphasizes that it functions as a flexible social mechanism rather than a uniformly prosocial trait. By situating empathy within RCT, this study provides a more comprehensive account of early social dominance, integrating emotional understanding with goal-directed behavior.

From a practical perspective, these findings suggest that empathy-based educational interventions should combine the development of empathic awareness with explicit instruction in moral reasoning, self-regulation, and non-coercive social strategies. Teachers and practitioners should help children channel emotional sensitivity and perspective-taking toward cooperative goals through guided discussion, role play, and positive reinforcement. Embedding these principles in early childhood curricula may promote prosocial leadership and peer harmony while reducing the likelihood that empathy is used for manipulative purposes. In conclusion, fostering empathy without accompanying guidance may be insufficient. Programs that pair emotional understanding with ethical and self-regulatory training are more likely to ensure that empathy becomes a foundation for fairness, cooperation, and socially responsible influence rather than a tool for coercion or control.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be found at: https://www.sciepublish.com/article/pii/836, Table S1: Hierarchical multiple regression predicting resource control success and social dominance.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the participating children, schools, and their staff for their valuable support during the data collection phase.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.P.R., C.P.M. and S.T.; Methodology, A.P.R., C.P.M. and S.T.; Software, A.P.R.; Validation, A.P.R., C.P.M. and S.T.; Formal Analysis, A.P.R.; Investigation, A.P.R.; Resources, A.P.R.; Data Curation, A.P.R.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, A.P.R.; Writing—Review & Editing, C.P.M. and S.T.; Visualization, A.P.R.; Supervision, C.P.M. and S.T.; Project Administration, A.P.R.; Funding Acquisition, C.P.M.; S.T. and A.P.R. contributed equally to this work.

Ethics Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and received ethical approval from the University of Greenwich Research Ethics Committee (UREC) (reference number: 15.4.5.14., June 2016).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Funding

This research was funded by the University of Greenwich Vice-Chancellor’s PhD Scholarship Scheme.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Roberts AP, Monks CP, Tsermentseli S. The influence of gender and resource holding potential on aggressive and prosocial resource control strategy choice in early childhood. Front. Educ. 2020, 5, 593763. DOI:10.3389/feduc.2020.593763 [Google Scholar]

- Hawley PH. The ontogenesis of social dominance: A strategy-based evolutionary perspective. Dev. Rev. 1999, 19, 97–132. DOI:10.1006/drev.1998.0470 [Google Scholar]

- Hawley PH. Prosocial and coercive configurations of resource control in early adolescence: A case for the well-adapted Machiavellian. Merrill-Palmer Q. 2003, 49, 279–309. DOI:10.1353/mpq.2003.0013 [Google Scholar]

- Hawley PH. Ontogeny and social dominance: A developmental view of human power patterns. Evol. Psychol. 2014, 12, 318–342. DOI:10.1177/147470491401200204 [Google Scholar]

- McGrew WC. An ethological study of agonistic behaviour in preschool children. In International Congress of Primatology, 2nd ed.; Karger Publishers: Basel, Switzerland, 1969; pp. 149–159. [Google Scholar]

- McGrew WC. An Ethological Study of Children’s Behaviour; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Sluckin AM, Smith PK. Two approaches to the concept of dominance in preschool children. Child Dev. 1977, 48, 917–923. DOI:10.2307/1128341 [Google Scholar]

- Chapais B. Role of alliances in the social inheritance of rank among female primates. In Coalitions and Alliances in Humans and Other Animals; Harcourt AH, de Waal FBM, Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1992; pp. 29–59. [Google Scholar]

- Charlesworth WR. Resources and resource acquisition during ontogeny. In Sociobiological Perspectives on Human Development; Donald KBM, Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1988; pp. 85–121. [Google Scholar]

- Charlesworth WR. Co-operation and competition: Contributions to an evolutionary and developmental model. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 1996, 19, 25–39. DOI:10.1177/016502549601900103 [Google Scholar]

- Russon AE, Waite BE. Patterns of dominance and imitation in an infant peer group. Ethol. Sociobiol. 1991, 12, 55–73. DOI:10.1016/0162-3095(91)90012-F [Google Scholar]

- Strum S. Reconciling aggression and social manipulation as means of competition: A life-history perspective. Int. J. Primatol. 1994, 15, 739–765. DOI:10.1007/BF02737429 [Google Scholar]

- Pellegrini AD, Roseth CJ, Mliner S, Bohn CM, Van Ryzin M, Vance N, et al. Social dominance in preschool classrooms. J. Comp. Psychol. 2007, 121, 54–64. DOI:10.1037/0735-7036.121.1.54 [Google Scholar]

- Pellegrini AD, Van Ryzin MJ, Roseth CJ, Bohn-Gettler C, Dupuis DN, Hickey MC, et al. Behavioral and social cognitive processes in preschool children’s social dominance. Aggress. Behav. 2011, 37, 248–257. DOI:10.1002/ab.20385 [Google Scholar]

- Roseth CJ, Pellegrini AD, Dupuis DN, Bohn CM, Hickey MC, Hilk CL, et al. Preschoolers’ bistrategic resource control, reconciliation, and peer regard. Soc. Dev. 2011, 20, 185–211. DOI:10.1111/j.1467-9507.2010.00579.x [Google Scholar]

- Premack D, Woodruff G. Does the chimpanzee have a theory of mind? Behav. Brain Sci. 1978, 1, 515–526. DOI:10.1017/S0140525X00076512 [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Miller PA. The relation of empathy to prosocial and related behaviors. Psychol. Bull. 1987, 101, 91–119. DOI:10.1037/0033-2909.101.1.91 [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Strayer J. Empathy and Its Development; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman ML. Empathy and Moral Development: Implications for Caring and Justice; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Cuff BMP, Brown SJ, Taylor L, Howat DJ. Empathy: A review of the concept. Emot. Rev. 2016, 8, 144–153. DOI:10.1177/1754073914558466 [Google Scholar]

- Decety J. The neurodevelopment of empathy in humans. Dev. Neurosci. 2010, 32, 257–267. DOI:10.1159/000317771 [Google Scholar]

- Decety J, Cacioppo S. The speed of morality: A high-density electrical neuroimaging study. J. Neurophysiol. 2012, 108, 3068–3072. DOI:10.1152/jn.00473.2012 [Google Scholar]

- Decety J, Meidenbauer KL, Cowell JM. The development of cognitive empathy and concern in preschool children: A behavioral neuroscience investigation. Dev. Sci. 2018, 21, e12570. DOI:10.1111/desc.12570 [Google Scholar]

- Imuta K, Henry JD, Slaughter V, Selcuk B, Ruffman T. Theory of mind and prosocial behavior in childhood: A meta-analytic review. Dev. Psychol. 2016, 52, 1192–1205. DOI:10.1037/dev0000140 [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR, Dodge KA. A review and reformulation of social information-processing mechanisms in children’s children’s social adjustment. Psychol. Bull. 1994, 115, 74–101. DOI:10.1037/0033-2909.115.1.74 [Google Scholar]

- Telle NT, Pfister HR. Positive empathy and prosocial behavior: A neglected link. Emot. Rev. 2016, 8, 154–163. DOI:10.1177/1754073915586817 [Google Scholar]

- Gungordu N, Hernandez-Reif M, Walker DI, Wind SA. Empathy and creativity as foundations and predictors of how prosocial behavior develops in preschool age children. Int. J. Child Care Educ. Policy 2025, 19, 6. DOI:10.1186/s40723-025-00147-0 [Google Scholar]

- Hawley PH, Geldhof JG. Preschoolers’ social dominance, moral cognition, and moral behavior: An evolutionary perspective. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 2012, 112, 18–35. DOI:10.1016/j.jecp.2011.10.004 [Google Scholar]

- Wang W. The altruism prioritization engine: How empathic concern shapes children’s inequity aversion in the ultimatum game. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1034. DOI:10.3390/bs15081034 [Google Scholar]

- Roseth CJ, Pellegrini AD, Bohn CM, Van Ryzin M, Vance N. An observational, longitudinal study of preschool dominance and rates of social behavior. J. Sch. Psychol. 2007, 45, 479–497. [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR, Casas JF, Mosher M. Relational and overt aggression in preschool. Dev. Psychol. 1997, 33, 579–588. DOI:10.1037/0012-1649.33.4.579 [Google Scholar]

- Hawley PH. Strategies of control, aggression, and morality in preschoolers: An evolutionary perspective. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 2003, 85, 213–235. DOI:10.1016/S0022-0965(03)00073-0 [Google Scholar]

- Sezov D. The Contribution of Empathy to Harmony in Interpersonal Relationships. Ph.D. Thesis, Temple University, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Poresky RH. The Young Children’s Empathy Measure: Reliability, validity and effects of companion animal bonding. Psychol. Rep. 1990, 66, 931–936. DOI:10.2466/pr0.1990.66.3.931 [Google Scholar]

- Dunn L, Dunn D. The British Picture Vocabulary Scale, 3rd ed.; GL Assessment: Brentford, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Fabes RA, Hanish LD, Martin CL, Eisenberg N. Young children’s negative emotionality and social isolation: A latent growth curve analysis. Merrill-Palmer Q. 2002, 48, 284–307. DOI:10.1353/mpq.2002.0012 [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein IS. Dominance: The baby and the bathwater. Behav. Brain Sci. 1981, 4, 419–429. DOI:10.1017/S0140525X00009614 [Google Scholar]

- Williams A, O’Driscoll K, Moore C. The influence of empathic concern on prosocial behavior in children. Front. Psychol. 2014, 5, 425. DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00425 [Google Scholar]