Insights in Applying Self-Determination Theory to Study Chinese Students’ Positive Functioning: Review of Current Literature and Suggestions for Future Directions

Received: 28 August 2025 Revised: 26 September 2025 Accepted: 04 December 2025 Published: 15 December 2025

© 2025 The authors. This is an open access article under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Self-determination theory (SDT) [1] is a prominent theory in positive psychology [2]. SDT has been applied to explain the optimal functioning of youths in educational institutions, in various aspects such as affective [3], achievement [4], and social [5] outcomes. Although there is no doubt that SDT is a prominent framework in studying well-being of school- or college-aged youths, SDT has been questioned regarding its validity to be applied in non-Western cultures, especially the East Asian culture that is prototypically represented by China. The current paper, hence, provides an updated review of various issues in applying SDT to study positive functioning in the context of Chinese education. In the first section, we briefly introduce what SDT is and why it has been an issue when applying it to China. Then, in the second section, we review empirical research that has examined SDT-related questions in China with a focus on the young population, thus providing information regarding the validity of SDT in China. Notably, Yu, Chen, et al. [6] have provided a good summary of research published before 2016, and thus, this current contribution will mainly focus on new literature since 2016. In the third part, the current article integrates new ideas from positive psychology and cross-cultural research to suggest future directions for applying SDT in Chinese education. The recent years have seen numerous influential articles published in the field of positive psychology to reflect on its cultural sensitivity. So far, these concerns have not been sufficiently realized by the SDT community in its effort of cross-cultural research. Thus, we aim to extend the existing research on applying SDT in China and point to potentially more fruitful frontiers.

1. A Brief Introduction to SDT, and Controversies Regarding Its Applications in China

1.1. A Brief Introduction to SDT

SDT is a macro-theory of human motivation, personality, and development [1]. It was founded by Edward L. Deci and Richard M. Ryan, and over the course of its development (which is five decades to date, counting from the first research by Deci [7]), it has gained international popularity and become one of the most influential contemporary theories for human positivity.

The core of SDT is the notion of self-determination, referring to one’s feelings, thoughts, and behaviors being determined by one’s true self [6]. SDT sees the self as an “integrative function”, or the “process through which a person contacts the social environment and works toward integration with respect to it” [8] (p. 238). Therefore, being self-determined refers to a person’s psychology being integrated, in the sense that constituent aspects of one’s psychology are in harmony with each other, rather than compartmentalized from or conflicted with each other. Self-determination represents a growth tendency among living organisms, and thus it is theorized as an essential contributor to human wellness.

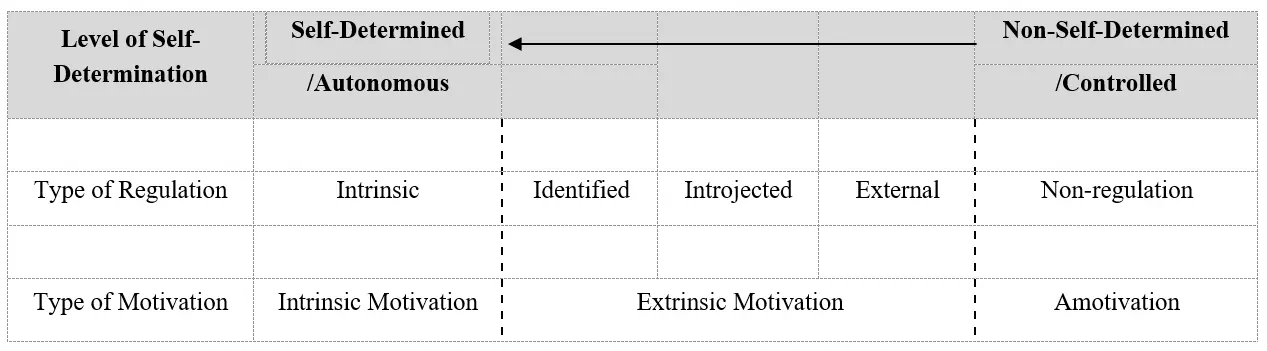

In the context of education, the prototype of student self-determination is intrinsic motivation. When students learn out of interest and fun, their learning behavior is motivated solely by the learning activity per se. Such is a manifestation of the students’ tendency to grow and develop a more differentiated, integrated self through interaction with the environment. In addition to intrinsic motivation, students’ learning may also be driven by extrinsic motivation, in which case it is not an end in itself but serves an instrumental purpose. Extrinsic motivation could be self-determined or non-self-determined, depending on how well that instrumental end is internalized. When the internalization is full, students wholeheartedly endorse the personal importance or value of their studies (termed identified regulation; also includes integrated regulation); in such cases, the behavior is perceived as consistent with their true self, and they are self-determined. When the internalization is nonexistent, students study only because of rewards or punishments alien to themselves, which are not integrated with their sense of self. Such is termed external regulation. Finally, sometimes the internalization is partial and incomplete: Students study for a reason not explicitly external to them, but not fully internalized. For example, students have an internal demand for themselves to study hard; otherwise, they feel unworthy. In such cases, the behavior is driven by internal pressure and conflict rather than integration, and it is termed introjected regulation.

These types of motivation and regulation (intrinsic motivation, identified regulation, introjected regulation, and external regulation), plus amotivation (the absence of any intrinsic or extrinsic motivation), form a continuum of self-determination (Figure 1 near here). SDT’s propositions about self-determination, including its continuum structure and its essential role in positive functioning, have received considerable empirical support over the past decades. For example, a recent meta-analysis [9] synthesizing 486 samples representing 205,000 participants clearly supported the continuum model. Another meta-analysis [10] synthesizing 344 samples representing 223,209 participants showed that student self-determination is positively correlated with adaptive outcomes (e.g., effort, engagement, psychological wellness, and self-efficacy) and negatively correlated with maladaptive outcomes (e.g., absenteeism and dropout and psychological ill-being).

Another important part of SDT is basic psychological needs (BPNs) [1]. Just as all living organisms need certain physical nutrients to function well physiologically, the human mind also needs certain experiential nutrients to function well psychologically. Thus, three of these experiential nutrients, or BPNs, have been identified, i.e., autonomy, relatedness, and competence. Autonomy refers to people’s need to self-organize their experiences and self-regulate their behaviors, while frustration that is related to this need involves feeling pressured and internally conflicted. Relatedness refers to the need to establish meaningful relationships with others, to care for others and be cared for, while the frustration related to this need involves relational exclusion and feelings of loneliness. Competence refers to the need to feel effective in interacting with the environment, while frustration that is related to this need involves feelings of failure and doubts about one’s efficacy. These needs have also received consistent support over the last decades (e.g., autonomy: [7]; competence: [11]; relatedness: [12]; for a comprehensive review, see [1], chapter 10).

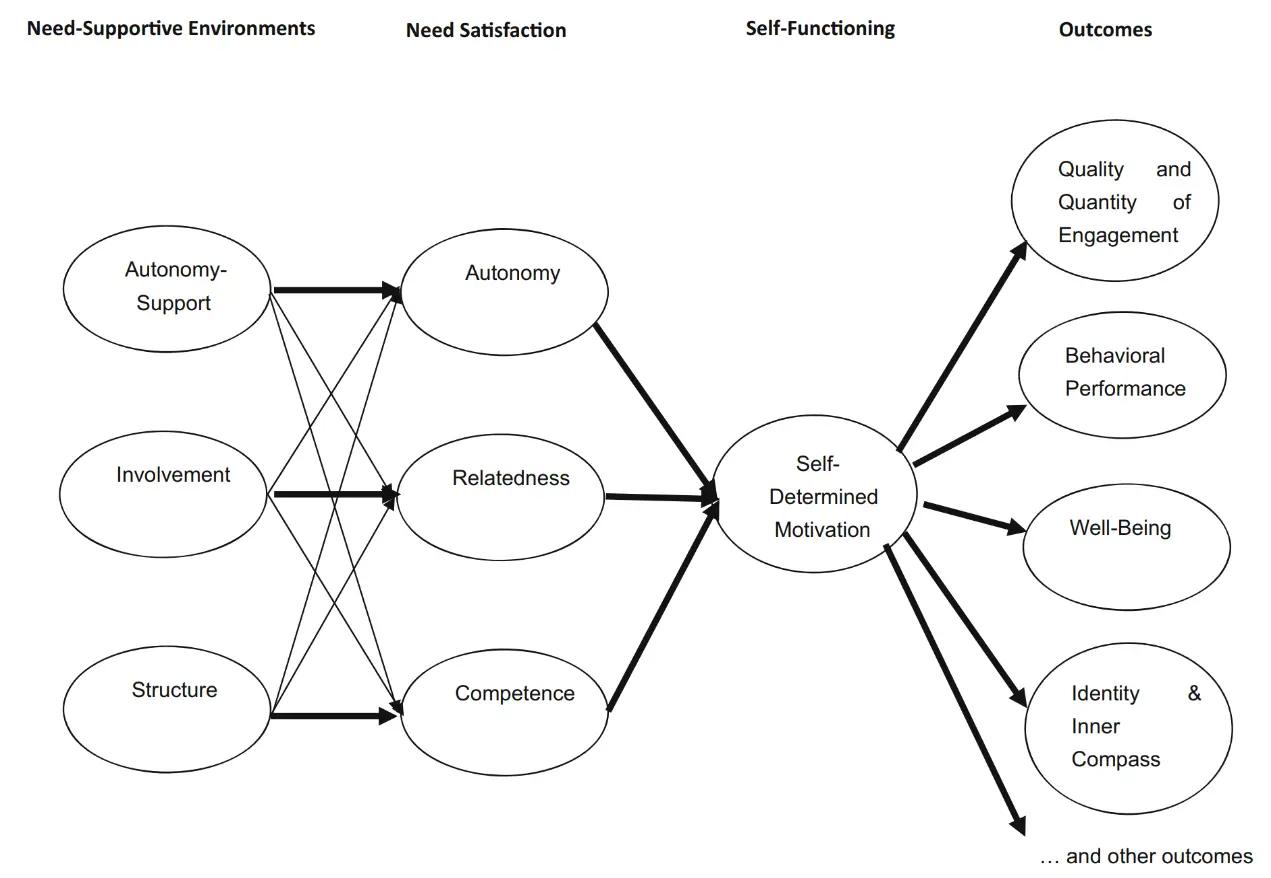

A last important component of SDT in the context of education is the social context. Just as features of the physical environment differentially satisfy the physiological needs of biological organisms (e.g., a tropical environment provides much more water to a plant than a desert), features of the social environment differentially satisfy the psychological needs of the human mind. SDT research has identified characteristics of social contexts that support the BPNs. For example, an autonomy-supportive classroom is characterized by teacher providing choices and options, minimizing control, taking student perspectives, and offering students rationale/relevance; a relatedness-supportive social context is characterized by the teacher (or parents) caring about the student (or child) and involved in the latter’s education; a competence-supportive social context is characterized by structure, or the presence of clear instructions, guidance, and feedback [1].

The foregoing theoretical prepositions have been summarized as the general SDT model (Figure 2 near here) [6]. In this model, social context either supports or thwarts the BPNs, which then predicts student self-determination, which then explains student positive and negative outcomes.

1.2. Controversies of Applying SDT in China

Most research on SDT during its formation years was conducted in Western populations. Consequently, the cross-cultural validity of SDT has been challenged over the last decades. When applied to China, the debate mainly focuses on whether the idea of self-determination applies to collectivist cultures as well as Western individualist cultures. According to Markus and Kitayama [13], people in collectivist societies such as East Asia have interdependent self-construals (one’s idea of self overlaps with that of other individuals), in contrast to the independent self-construals popular among Western individualist cultures. For this reason, it is questionable whether individual self-determination or autonomy is essential for positivity. For example, Iyengar and Lepper [14] showed that making a personal choice was motivating for Anglo-American children, but choices made by in-group others (e.g., mothers, classmates) were more motivating for Asian American children.

On the other side of the debate, SDT theorists pointed out a critical conceptual distinction between self-determination (or autonomy), defined as integrated functioning, and independence, individualism, or separation. It may be true that independence, individualism, or separation is less relevant for people from collectivist cultures; however, self-determination or autonomy is considered to have an evolutionary basis and thus universal among humanity. Psychometric evidence supported the conceptual separation between self-determination or autonomy and independence or self-reliance [15]. In addition, some research has also shown that individualism, independence, or self-reliance is relatively orthogonal to self-determination or autonomy. That is, an individual’s being individualist or independent from others may be based either on self-determination or non-self-determination, and it is the latter that is always essential for human wellness [16].

These controversies are relevant not only to academia but also to educational policies and pedagogical practices. Indeed, dismissing SDT’s core tenets as inapplicable could be used to justify high-pressure, controlling pedagogical practices that may undermine student well-being, even if they are culturally entrenched [6]. Conversely, validating SDT’s framework in China provides a crucial theoretical and empirical foundation for educational reform, offering a clear rationale for whether policies like the “Shuangjian” (double-reduction) initiative [17] can be effective or not. Furthermore, it shifts the practical focus from merely importing Western-style interventions to developing culturally adapted pedagogical strategies that effectively support Chinese students’ universal needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness, thereby promoting both well-being and high-quality learning.

2. How Research Has Addressed These Issues of Application in China

So far, research has primarily addressed the issue of applying self-determination theory to China by examining the general SDT model and its components in China. That is, the core propositions of SDT, including the effect of self-determined motivation, the effect of BPN, and the effect of need-supportive context, have all been tested in China, and sometimes compared to the West, to illuminate their validity and strength in a collectivist context.

We identified SDT studies in the Chinese context on Google Scholar, using a comprehensive combination of several strategies. First, we engaged in a direct literature search using key terms such as “self-determination theory”, “Chinese”, “(education OR school OR student OR learning OR classroom OR teaching)”, and “culture”, limiting the search results to those published after or citing the key publication by Yu et al. [6]. Second, we searched the Chinese literature using the Chinese counterpart of these search terms. Third, we reviewed the publications of several key research labs relevant to this area, such as Prof. Tian Lili.

The empirical evidence generally points to a universalism without a uniform pattern [18]. That is, the general SDT model has been supported in China, although there has been some research showing variant strengths of the effects. In the following, we provide the most recent review of research that applied SDT to China. As previously explained, this review will mainly focus on empirical research published since 2016. For research before 2016, we will only very briefly mention, and the readers are directed to Yu, Chen, et al. [6] for more details.

2.1. Universal Findings

2.1.1. Effects of Self-Determined Motivation

First, studies have supported the effects of self-determined motivation. Before 2016, a few studies had already supported the importance of self-determined motivation for Chinese students. For example, Vansteenkiste et al. [19] showed that self-determined motivation to study English predicts their adaptive learning attitudes, academic success, and personal well-being. Research in recent years has tested the role of self-determined motivation in more diverse situations and extensive outcomes.

For example, various studies by Yu and colleagues [20,21,22] showed that self-determined motivation predicts academic performance, well-being, and psychological growth; Liu et al. [23] showed that primary school students’ self-determined motivation for homework predicts their positive affect experienced for doing homework; Zhou and Ren [24] showed that students with more self-determined academic motivation tend to like collaborative learning, which subsequently explains their lower levels of task disengagement; Ma et al. [25] showed that self-determined academic motivation predicts students’ higher academic expectancy; Jiang and Huang [26], who showed that autonomous motivation was associated with beliefs and intentions for leisure physical activity; Chen et al. [27] reported that Ph.D students’ autonomous motivation was negatively correlated with their burnout and depression.

Notably, the association of self-determined motivation with various forms of engagement received especially abundant attention. This association with engagement has been supported among Chinese high school students [28], postgraduate students [29], students with special needs [30], as well as online learners [31].

2.1.2. Effects of BPN

Before 2016, the most prominent research that testified the importance of BPN for Chinese students was perhaps Chen et al. [32], who showed that satisfaction of each of the three needs was found to contribute uniquely to the prediction of well-being, whereas frustration of each of the three needs contributed uniquely to the prediction of ill-being, and that these predictive effects hold constant across cultures. In the following years, researchers have followed up to test the effects of BPN in more varieties of educational contexts and on more varieties of student outcomes. For example, while Zhang et al. [33] replicated the positive effect of BPN on positive affect, Xu [34] showed that BPN positively predicted self-regulated learning (e.g., using time-management strategies to organize one’s studies), and Ganotice et al. [35], Liu et al. [36], Zhang and Qian [37], and Zhou et al. [38] reported a positive impact of BPN on classroom engagement and performance. Other student outcomes shown to be positively predicted by BPN include intercultural [39] and career-related competencies [40].

Other research has shown that the effects of BPN on student functioning provide a proximal explanatory mechanism for other antecedents. For example, several studies [37,38,41,42,43,44,45] have shown that BPN mediates the association between social support and student engagement. Other studies showed that BPN mediates the positive effects of students having an eudaimonia orientation [46] and intrinsic goals [47], as well as the negative effects of students’ making academic social comparisons [48].

One area of research popular in recent years is the application of BPN in online or computer-assisted classrooms, perhaps due to the recent trend of digitizing learning and the influence of COVID-19. In the Chinese cultural context, research shows that BPN is positively associated with students’ engagement in online classrooms [49,50,51], their intention to use online learning tools [52], and their satisfaction with flipped classroom learning [53]. Additionally, BPN experienced by teachers predicts their use of online teaching methods [54,55].

In addition to these individual research extensions, Tian and colleagues [56,57,58,59,60] conducted a series of systematic large-scale survey studies to examine the role of BPN in student positive functioning. For example, Wang et al. [57] and Zhou et al. [59] demonstrated the longitudinal effects of BPN satisfaction on behavioral engagement, academic achievement, and positivity (e.g., optimism, satisfaction with life, and confidence in others), using a cross-lagged model. Zhou et al. [58] showed that BPN predicts more positive profiles of mental health, and Zhou et al. [60] showed that profiles of BPN were significantly associated with time-varying mental health and academic functioning indicators.

Finally, Yu et al. [61] provided a review covering all research published before 2016 to compare the strengths of the relationship between the need for autonomy and subjective well-being. The authors found that a medium-sized correlation (r = 0.46) characterizes both studies conducted among Americans and studies conducted among East Asians. The between-culture difference in this association between autonomy need satisfaction and well-being is non-significant.

Effects of Inner Compass. In addition to the abovementioned research testing the “classic” needs in SDT in China, in the recent decade, Assor [62] proposed a new concept, inner compass, which characterizes a more positive and active aspect of the need for autonomy. That is, fulfilling the need for autonomy requires not only that one’s will not being constrained by external constraints (i.e., “freedom from”, or the negatively defined aspect of autonomy), but also that one knows what one wants to do to be themselves authentically (i.e., “freedom for”, or the positively defined aspect of autonomy). It is not uncommon for even privileged young people, who arguably are relatively free from external constraints, to feel that they cannot engage in behaviors that are personally meaningful and engaging.

For example, a psychological problem that has gained popularity in Chinese education in recent years is kongxinbing (空心病, or “empty heart disease” by literal translation [63]. A Chinese psychologist, Xu Kaiwen, coined this term when he observed that as many as 40% first-year students at Peking University, a top university in China, suffered from meaninglessness and suicidal tendencies. Thus, freedom from constraints is insufficient for youths to have their need for autonomy satisfied; they also need to develop an inner compass, or schemas (e.g., values, interests, goals, and group affiliation) that guide them in important decisions to lead a satisfying life [62]. This need seems to be important also for Chinese students, which may be especially intriguing given that traditionally Chinese education has downplayed individual pursuits and emphasized individuals’ contributions to the collective society [6].

Recent research supported the importance of having an authentic inner compass for Chinese youths. For example, Assor, Yu, and colleagues showed that having an authentic inner compass contributes to Chinese and Israeli youths’ well-being [64] and that having an authentic inner compass contributes to youths’ self-determination in interacting with their mothers and subsequent vitality [65]. Research by Yu and colleagues also demonstrated that youths’ development of an inner compass is predicted by a set of specialized parenting styles [66], especially inherent value demonstration [67]. Overall, these studies extended the cross-cultural universality of self-determination theory into the emerging field of research on inner compass.

2.1.3. Effects of Needs Support

Prior to 2016, there had already been a multitude of research supporting the importance of need-supportive vs. need-thwarting contexts in Chinese education. For example, many studies showed the effects of autonomy support and control for teachers [51,68,69,70,71,72] and parents [73,74,75,76,77] on motivation, engagement, academic performance, and well-being.

In the recent years, research has shed light on the role of need-supportive context on more diverse outcomes in Chinese education, such as students’ undertaking of mastery vs. performance goals [78], homework quality [79], increased STEM interest and identity [80], career exploration [81], better class engagement [37,44,45], creativity [82], academic performance [83], socio-emotional skills [84], and developmental trajectories of depression symptoms [85]. Some [86] tested the effects of autonomy-supportive teaching intervention on student needs and learning outcomes.

Importantly, some researchers took advantage of the openly accessible PISA dataset [87] to examine the effects of teacher autonomy support cross-culturally. Wang et al. [88] showed that need-supportive teaching has positive effects on subjective, eudaimonic, and social forms of well-being across all eight cultural groups included in the PISA dataset (i.e., Africa and Middle East, Confucian, East-Central Europe, English-speaking, Latin America, South-East Asia, and West Europe). Nalipay et al.’s [89] analyses took a more refined look at the support for the three needs separately: They found that (a) all three need supports have a positive role across cultures (and thus supporting the universality claim), and (b) the strengths of effects hold constant for autonomy support and relatedness support, but not competence support, which was stronger in the West.

Some researchers further supported the role of parental autonomy support vs. control in predicting various youth positive outcomes. For example, Li et al. [90] analyzed the profiles of parents’ need for support and showed that high parental involvement may not always be good, unless accompanied by relatively high levels of autonomy support and low levels of control. Ching et al. [91] and Wei [92] both showed that parental psychological control predicts adolescents’ higher levels of academic contingent self-esteem, while Chen et al. [93] showed that compared to American youths, Chinese youths particularly suffered from lower self-esteem over the course of seventh to eighth grade because their parents are more controlling.

Notably, two studies have examined the effect of teacher and parents need support in conjunction. Li et al. [94] and Zhou et al. [95] both showed that teacher and parent autonomy support work together to predict self-determination processes and positive outcomes.

2.1.4. The General SDT Model

The Li et al. [94] and Zhou et al. [95] studies serve not only as examples of need-supportive parenting, but also as the general SDT model. That is, over the past years, an increasing amount of research has examined the effects of needs support (vs. needs thwarting), self-determination processes (e.g., BPN and self-determined motivation), and positive student functioning outcomes in conjunction with each other. This body of research has shown that self-determination processes mediate the effect of need-supportive vs. need-thwarting social context on various student outcomes including engagement [95,96], well-being [17,97], personal growth [98], socio-emotional development [99], grit [100], peer victimization [101], academic dishonesty [102], and non-suicidal self-injury [103]. A recent meta-analysis that focused on the relationship between teacher autonomy support, basic psychological needs, academic motivation, and academic achievement [104] supports the general SDT model, and also concluded that the effects of teacher autonomy support are not moderated by student age or economic and cultural background.

2.2. Without Uniformity

Empirical findings of the moderation of culture when applying SDT to China can be generally categorized into two types, consistent with the summary by [17]. The first type focuses on the front-end of the SDT model, i.e., the effects of social context on self-determination processes, while the second type focuses on the rear-end of the SDT model, i.e., the effects of self-determination processes on positive student functioning.

Concerning the front-end, research has shown that due to the fact that harsh and controlling teaching and parenting styles are more normative among Chinese families [6,105], their negative impact on self-determination and positive functioning may be weakened. For example, Zhou et al. [71] showed that Chinese primary school students perceived teacher behaviors, such as detaining the student after school and asking the student to repeat the spelling mistakes many times, as less controlling than their American counterparts. This perception subsequently explains Chinese students’ higher levels of classroom engagement. A similar finding was reported by Chen et al. [106], who showed that Chinese adolescents perceived parents’ use of guilt induction as less controlling and demonstrated more compliant coping. Soenens et al. [107] showed a similar finding among Korean students (who have a similar cultural background as Chinese students) that students’ endorsement of the collectivist value predicts their being less sensitive in perceiving controlling teaching behavior.

A few studies have also shown evidence of moderation at the rear end. For example, Lynch et al. [108] examined authenticity, operationalized as the congruence between one’s ideal and actual self-concept, among college students from various countries. They found that although larger discrepancies between actual and ideal self-concepts are associated with worse well-being, the association is weaker among Chinese participants, compared to Americans. Given that authenticity can be seen as highly related to the need for autonomy (i.e., one aspect of autonomy need satisfaction is that one’s thinking, feeling, and behaviors are congruent with one’s true self), Lynch et al.’s [108] research provided one piece of evidence that the effect of autonomy need satisfaction may be slightly weaker in China.

Relatedly, materialism has been considered as strongly thwarting the basic psychological needs, because it directs people away from the most intrinsically satisfying things in life [109]. However, recent research showed some evidence that materialistic orientation may not be as harmful for Chinese and other East Asians [110]. The researchers posit that this moderation is at least partially because East Asians’ materialism is motivated by social relatedness. That is, materialism in East Asian means more of aiming at owning more money so that one can relate to others, as opposed to owning more money so that one can outcompete others, which is the typical case in Western culture. To the extent that this interpretation is true, this finding may not necessarily exemplify the cultural moderation of the effects of basic needs per se; still, it illustrates a possibility that the well-established self-determination processes may manifest different outcomes in Chinese culture.

A recent study by Nalipay et al. [88] tested cultural moderation using the large PISA dataset. Although they did not find a moderation effect of autonomy and relatedness support, they did find that teacher competence support has a stronger facilitative role for academic achievement for students in the West compared to the East (including Chinese societies). According to Nalipay et al. [88], this may be due to the ceiling effect in the East, where the competence support is already very high. This serves as another incidence of the moderation effect found in self-determination processes on Chinese student outcomes.

3. Emerging Concerns and Future Directions Informed by Recent Advancements in Cultural and Positive Psychology

Research reviewed in the previous section applied the well-established SDT model (with variables well-established in the West) in China to examine its generalizability. Apart from this cross-cultural approach of studying SDT in China, in recent years, several new issues have emerged that emphasize sensitivity to cultural and contextual issues in the study of topics related to positive functioning [111]. In our view, these issues have not yet gained enough attention from SDT researchers interested in China, and they deserve to inspire and lead future directions of inquiry.

3.1. Using Individual Positivity Indicators Native to the Chinese Culture

The first of these concerns is that positive psychologists have increasingly realized the cultural differences in the nature of individual positivity. For example, subjective well-being (SWB) [112] has been used as one predominant measure of individual well-being (including in SDT research), yet this understanding has been criticized as culturally insensitive, as each culture may have its own form of well-being [113,114]. In this vein, SDT research should extend itself to studying how self-determination processes explain positive outcomes that are grounded in and more indigenous to the Chinese culture.

Before proceeding to discuss the application of SDT research to positive outcomes sensitive to the Chinese culture, it is important to first discuss a caveat of what qualifies as culturally sensitive positive outcomes. It is in our view an important distinction that we should study positivity as a characteristic of the Chinese culture, rather than positivity as merely conceptualized as important or native to the Chinese culture. To illustrate, Tafarodi et al. [115] showed that Chinese people, among all cultures investigated, had the highest level of endorsement for “having had a successful career” as important for living a good life (also supported in Lu, [116]). Does this mean career is one form of well-being that is truly more relevant to Chinese people? We argue not necessarily, because this conception could be wrong, and it may not actually be the case that career success is more characteristic of a Chinese person’s good life. Past research has already shown that what people believe to be important may not be truly good [109] or that it does not matter for what is truly good [31].

So, what forms of positivity are truly more characteristic of the Chinese culture? One theme that has been established in the past two decades is that Chinese people tend to experience affects that are characterized by lower arousal, more balance, and harmony. For example, Tsai et al. [117] showed that more excited (vs. calm) positive emotions were characteristic of American children’s books compared to Taiwanese children’s books. As another example, Ho et al. [118] showed that Chinese people’s peak experiences are typically more characterized by serenity compared to those of the Portuguese. Kitayama et al. [119] also showed that among Japanese (who share a similar cultural background as Chinese) college students, the correlations between positive and negative emotions are more likely to be positive, an opposite finding compared to those found among American college students.

This phenomenon has been explained to be related to the philosophies unique to the East Asian context. For example, in Buddhism, equanimity is seen as an ideal state of mind achieved by those who reach nirvana or a state of freedom from troubles in daily life [120]. From the Buddhist perspective, happiness, as defined in the Western context, is no more than an illusory and not particularly desirable experience [113]. In Confucianism, moderation in happiness is seen as one of the many reflections of the Doctrine of the Mean (zhongyong) [121], which is considered a virtuous way to live. In Daoism, the harmonious state of mind is seen as a result of acquiring and practicing the dao—the truth of life and the vital principles of the world, which involves a dialectic between the positive and the negative.

Some research has followed this line of reasoning and examined the role of self-determination in positive affects more characteristic of the Chinese culture. In Yu et al. [3], the authors compared the effects of basic psychological needs on two positive affects that are more characteristic of Chinese and Western cultures, respectively, namely peace of mind [122] and vitality [123]. Results showed that basic psychological needs indeed predict peace of mind, with an effect that is even stronger than predicting vitality, although no moderation role of culture was supported. Relatedly, another research by Datu [124] showed that among another collectivist Asian (i.e., Filipino) student population, peace of mind was positively associated with autonomous academic motivation, although the association with controlled motivation is also positive. A recent study [125] showed that there is a subgroup of Chinese college students whose well-being profiles were characterized by high levels of peace of mind, and that self-determination variables predict membership in this profile.

Overall, these studies constitute some of the first attempts to examine SDT with a cultural awareness of positivity measures used. In the future, more research is needed to examine the effects of self-determination processes on positive psychological processes that characterize the Chinese culture. As an example, classic research that demonstrates the potency of SDT in predicting positive functioning [126,127,128] can be replicated in China with a focus on using peace of mind as the well-being outcome. Candidates for such positive indicators may include ideas such as a sense of moral-ethical fulfillment (e.g., 仁义的理性之乐), and a state of spiritual-aesthetic joy derived from appreciating and “flowing with” nature (e.g., 顺应自然之乐) [129], both of which represent profound states of well-being deeply rooted in the traditional Chinese culture.

In addition, another implication that is more theoretical is that the SDT model itself may be adapted to fit the Chinese context. For example, past research [130] has already shown that interpersonal harmony is more essential for Chinese people’s well-being. Given that the idea of interpersonal harmony is highly overlapped with the idea of relatedness, one may argue that it is perhaps more fruitful to treat relatedness as an integral part of well-being (as opposed to a predictor of it, as shown in the general SDT model) when studying the Chinese population.

3.2. Considering Collective-Level Well-Being Indicators

The preceding section discusses the issue of forms of individual well-being more characteristic of the Chinese culture. However, well-being can be conceived not only on the individual level but also on the social level, and they do not always cohere [131]. The idea, per se, that individual-level positivity is the ultimate outcome variable to study self-determination processes can be argued to be based on a Western view. At the end of the previous section, we discussed how Chinese people’s well-being is more inherently connected to the well-being of others. Therefore, Chinese people may choose to sacrifice their own well-being if it helps with the collective harmony. As examples, Lin et al. [132] and Kao et al. [133] both showed that under interpersonal conflict situations, a relational or self-transcendent (vs. self-interest) orientation explains why some Chinese people experience higher well-being and relationship quality even when they suppress themselves and compromise with the other side in the conflict. Assumably, suppressing oneself generally does not feel good, but because one recognizes its contribution to the collective, they are at peace in that situation. Given this interpretation, evaluating the positive effects of self-determination on individual well-being may not always capture the essential positivity. Krys and colleagues’ research [134,135] also showed that countries high on individualism (vs. collectivism) tend to score also higher on individual satisfaction with life, but not on other more interdependent forms of well-being, which further supports the point that individual-level well-being may not be as characteristic for Chinese people’s positivity as in the West.

This issue of higher-level analysis is pertinent, especially when considering the analogy that in Eastern cultures, collectives can be considered as superorganisms. For example, Haidt et al. [136] pointed out that when it comes to egg productivity, productive cages are more relevant than productive individual chickens. That is, a cage of high-producing individual chickens may not produce the most eggs, because the chickens therein may fight each other. Along the same line of reasoning, just as cell-level wellness is more pertinent as an indicator of wellness for amoebas than for humans, maybe traditional individual well-being, such as subjective well-being [112], is more suitable as an indicator of wellness for Westerners than for Easterners, given the latter’s tighter social cohesion.

What may serve as collective-level indicators of positivity (which are more relevant to the Chinese population)? Veenhoven [137] provided a framework for conceptualizing such collective-level indicators by considering how the collective functions, such as its affordances and outcomes, internally and externally. Oishi [138] pointed out that at the national level, one example is corruption. He showed that countries such as Italy have higher levels of individual well-being but worse levels of corruption when compared to regions such as Hong Kong. Thus, positive-functioning individuals did not equal positive-functioning collectives, in this case. Another example may be to look at family-level functioning, considering that strong family ties are part of Chinese culture [139]. In this regard, SDT research may borrow from the recent progress in the study of positive psychology in families [114,140], and focus on indicators of positivity at the family level, such as leisure time family members spent together, frequency of positive and negative communication between family members, family cohesion, family meaning and identity, positive family outlook, effective financial management, consistency between family members’ psychology, etc. Currently, SDT research on families has primarily focused on child-parent dyads or couple dyads [1], while future research may target families as the unit of study for positive functioning.

We acknowledge that collective well-being is a highly novel issue, given that little research has paid attention to differential levels of analysis in positive psychology [30]. One particular challenge brought by this preliminary nature of the literature is the validation of collective wellness constructs. That is, just as the construct validity of individual wellness measures needs to be supported with an established empirical paradigm, the construct validity of collective wellness also needs conceptual development and empirical support—this is a relatively underdeveloped area in positive psychology.

3.3. Other Contextual Issues in Chinese Education

Finally, a recent advancement in cultural research is to see culture as a system of multiple interconnected and interacting constituents, as opposed to monolithic categories such as individualism vs. collectivism [141]. Thus, when applying SDT to non-Western cultures, the issues worth studying should extend much further beyond the question that has predominantly guided researchers so far (also see King et al., [142]), i.e., “does self-determination work under a collectivist culture?”.

Consider the research by Heine et al. [143], as well as Oishi and Diener [144], who showed that unlike Americans, whose engagement in a task is determined by previous experiences of success, for Asians, their engagement is non-related to previous experiences of success, or even negatively related, such that participants who succeeded on a previous task are actually less likely to persist on the task. Their findings are in stark contrast to SDT’s claims about the importance of positive feedback in supporting the satisfaction of the need for competence [1,11]. However, to the best of our knowledge, these anomaly findings have not yet been addressed by SDT researchers. This highlights the fact that the existing SDT research applied to a cross-cultural context, which primarily focuses on how collectivism influences the effect of autonomy, has been very limited.

Such a phenomenon has multiple potential explanations from the SDT perspective. The first possibility is that failure does not have invariantly the same functional significance in different cultures. Just like mentioned in previous sections, when controlling practices become normative in the Chinese culture, Chinese students become accustomed to it and do not perceive it as controlling as their Western counterparts. By the same token, it is possible that due to the highly challenging (and typically non-student-centered) basic education that Asians typically receive [6], they have developed a high tolerance for failure. Negative task feedback, therefore, does not constitute a thwart to their competence, but rather, due to their informational value, may constitute structure. This possibility corresponds to the front-end moderation in the aforementioned perspective of universality without uniformity.

Another possibility is rear-end moderation: Asian students do suffer from competence frustration when they encounter negative task feedback, but for some reason, their task engagement is not affected (or even improved). For example, maybe because the Chinese culture emphasizes effort more than the West [145], Chinese students’ output continued to be identified with engagement. Alternatively, maybe because Chinese students tend to have lower self-determined motivation [6,19], they become ego-involved after the failure and output continued compulsive engagement. These possibilities will only be addressed if future SDT research extends its cross-cultural lens beyond individualism vs. collectivism.

4. Contributions, Practical Implications, and Limitations

This review makes several key contributions to the field. Its primary contribution is the synthesis of two decades of research to provide a clear, evidence-based resolution to the long-standing controversy regarding SDT’s applicability in China. By organizing the evidence, we demonstrate a consistent “universalism without uniformity” pattern. This moves the academic discourse beyond a simplistic “East vs. West” dichotomy and toward a more nuanced understanding of how universal psychological needs are expressed, and can be supported, within China’s unique cultural and institutional context. Furthermore, this review bridges established SDT models with emerging research in cultural and positive psychology by proposing concrete future directions that focus on culturally-sensitive well-being indicators (e.g., peace of mind, moral fulfillment) and collective-level functioning [refer to Section 3].

Beyond its academic contributions, this review has significant practical implications for policymakers, educational psychologists, and educators in China, especially in light of recent social and political factors. The validation of SDT’s core tenets provides a powerful diagnostic lens for understanding pressing contemporary phenomena. For example, the widespread sense of “involution” (Neijuan) or the “educational arms race” can be understood as a large-scale societal outcome of a collective thwarting of basic psychological needs, where motivation becomes predominantly controlled and amotivated [96]. From this perspective, major top-down interventions like the “Shuangjian” (double-reduction) policy [96] can be analyzed as an attempt to de-escalate the need-thwarting pressures on students and families. For policymakers and educational psychologists, SDT thus offers a clear theoretical rationale for why such reforms are necessary for student well-being and provides an empirical framework for evaluating their success based on whether they genuinely shift the motivational climate in schools and homes.

For educators on the ground, this review cautions against two opposing pitfalls: (1) dismissing autonomy-supportive practices as “Western” and inapplicable, or (2) importing them wholesale without cultural adaptation. The principle of “universalism without uniformity” suggests the practical challenge is to identify and implement pedagogical strategies that are functionally autonomy-supportive, even if they are not topographically identical to Western-style choice provision. For example, a teacher providing clear structure, meaningful rationale, and constructive feedback in a way that is perceived as caring and guiding (rather than as a tool for shaming or control) can be highly need-supportive in the Chinese context. The practical goal for educators, therefore, is to foster internal motivation and well-being by finding these culturally-congruent ways to support students’ needs for autonomy (e.g., acknowledging perspective, providing rationale), competence (e.g., offering optimal challenges, non-controlling feedback), and relatedness (e.g., demonstrating warmth and care).

It is also important to contextualize the robustness of the reviewed data by highlighting several limitations and directions for future research. First, a significant portion of the research relies on cross-sectional, self-report methodologies, which limit the ability to draw causal conclusions. Future work would be substantially enriched by the inclusion of longitudinal studies to track motivational changes over time and specific educational intervention studies to causally test the impact of need-supportive pedagogical practices in Chinese classrooms. Second, many studies treat “Chinese culture” as a monolith, overlooking the vast internal diversity within China. There is a pressing need for research to explore internal variations, such as regional, urban/rural, and school-level differences (e.g., “key” schools vs. vocational schools). Investigating these nuances is crucial for understanding how local socioeconomic and institutional factors interact with broader cultural values to shape student motivation, allowing for more targeted and effective policies.

Finally, future studies may continue to engage in critical reflection on the universalism without a uniform pattern. In our review, we occasionally identified findings where the proposed effects in SDT are supported only in Western, not East Asian samples. For example, Taylor and Lonsdale found that the association between perceived relatedness and academic effort was non-significant among Hong Kong students, whereas it was significant among their British counterparts [146]. Such findings are scarce and do not threaten the validity of the overall pattern of universalism without uniformity, although we encourage future studies to continue studying the cultural variability of SDT.

5. Conclusions

In this article, we provide an updated review of research on the cross-cultural issues of SDT in Chinese education. The review of existing research has supported a universalism without uniformity pattern. That is, the basic tenets of SDT have received qualitative confirmation when applied to China, although the effects’ strengths vary quantitatively due to various mechanisms (e.g., the “front-end” and “rear-end” moderators). The evidence regarding “universalism” is especially solid given the unanimous support provided by dozens of studies. The “without uniformity” part may be relatively thin at present, and more research appears to be needed before a consistent understanding can be formed about the conditions under which the strengths of effect may be moderated.

The richness of the research reviewed above, which examined SDT cross-culturally and supported the universalism without uniformity pattern, stands in stark contrast to the dearth of research addressing a few other emerging yet still important issues of applying SDT to study Chinese education. That is, little (if at all) research has focused on (1) how SDT explains phenomena of positivity native to the Chinese context, (2) how SDT could be used to explain positivity at the collective level, which is supposed to be more relevant to China compared to the West, and (3) whether there are cultural moderations of SDT in addition to the individualism vs. collectivism dimension. Future research is urgently needed.

Given the current review, it appears that while research has been maturing in some well-established paradigms, it has yet to be developed in other emerging areas. Whenever such a differential exists between two areas, it can be predicted that energy flows from the maturing area to the emerging area. Such ebbs and flows have been termed waves and used to describe the directions of progression in the field of positive psychology [114]. In the same vein, here we tentatively suggest that it may be reasonable to summarize the existing paradigm of cross-cultural SDT research (i.e., replicating the well-established SDT model and variables to the Chinese population to examine its generalizability under a collectivist culture, as reviewed in the second section) as the first wave, and the emerging trends identified in the third section as the second wave. It is no doubt valuable for researchers to continue contributing to the energy of the first wave; nonetheless, in our view, research that transcends simple replication across cultures and embraces higher sensitivity to phenomena native to the Chinese culture beyond the collectivism aspect is where it promises the greatest inspiration and discovery.

Statement of the Use of Generative AI and AI-Assisted Technologies in the Writing Process

This manuscript is a comprehensive review article. During the preparation of this work, the authors utilized GPT-5 to help optimize text organization and language polishing. No generative AI tools were used to create or generate the scientific or conceptual content of the paper. All theoretical viewpoints and literature discussions presented in this article are original and independently developed by the authors. After using this tool, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the published article.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, original draft preparation, review and editing, supervision—S.Y. Review and editing—J.G.

Ethics Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The author declares that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

-

Ryan RM, Deci EL. Self-Determination Theory: Basic Psychological Needs in Motivation, Development, and Wellness; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

-

Sheldon KM, Ryan RM. Positive Psychology and Self-Determination Theory: A Natural Interface. In Human Autonomy in Cross-Cultural Context; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2011; pp. 33–44. [Google Scholar]

-

Yu S, Zhang F, Nunes LD, Deng Y, Levesque-Bristol C. Basic Psychological Needs as a Predictor of Positive Affects: A Look at Peace of Mind and Vitality in Chinese and American College Students. J. Posit. Psychol. 2020, 15, 488–499. doi:10.1080/17439760.2019.1627398. [Google Scholar]

-

Yu S, Levesque-Bristol C. A Cross-Classified Path Analysis of the Self-Determination Theory Model on the Situational, Individual and Classroom Levels in College Education. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2020, 61, 101857. doi:10.1016/j.cedpsych.2020.101857. [Google Scholar]

-

Weinstein N, Ryan RM. When helping helps: Autonomous motivation for prosocial behavior and its influence on well-being for the helper and recipient. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2010, 98, 222–244. doi:10.1037/a0016984. [Google Scholar]

-

Yu S, Chen B, Levesque-Bristol C, Vansteenkiste M. Chinese education examined via the lens of self-determination. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2018, 30, 177–214. doi:10.1007/s10648-016-9395-x. [Google Scholar]

-

Deci EL. Effects of externally mediated rewards on intrinsic motivation. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1971, 18, 105. doi:10.1037/h0030644. [Google Scholar]

-

Deci EL, Ryan RM. A Motivational Approach to Self: Integration in Personality; University of Nebraska Press: Lincoln, Nebraska, 1991. [Google Scholar]

-

Howard JL, Gagné M, Bureau JS. Testing a continuum structure of self-determined motivation: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 2017, 143, 1346–1377. doi:10.1037/bul0000125. [Google Scholar]

-

Howard JL, Bureau J, Guay F, Chong JXY, Ryan RM. Student Motivation and Associated Outcomes: A Meta-Analysis from Self-Determination Theory. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2021, 16, 1300–1323. doi:10.1177/1745691620966789. [Google Scholar]

-

Reeve J, Olson BC, Cole SG. Motivation and performance: Two consequences of winning and losing in competition. Motiv. Emot. 1985, 9, 291–298. doi:10.1007/BF00991833. [Google Scholar]

-

Bao X, Lam S. Who makes the choice? Rethinking the role of autonomy and relatedness in Chinese children’s motivation. Child Dev. 2008, 79, 269–283. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01125.x. [Google Scholar]

-

Markus HR, Kitayama S. Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychol. Rev. 1991, 98, 224–253. doi:10.1037//0033-295X.98.2.224. [Google Scholar]

-

Iyengar SS, Lepper MR. Rethinking the value of choice: A cultural perspective on intrinsic motivation. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 76, 349–366. doi:10.1037//0022-3514.76.3.349. [Google Scholar]

-

Van Petegem S, Vansteenkiste M, Beyers W. The jingle–jangle fallacy in adolescent autonomy in the family: In search of an underlying structure. J. Youth Adolesc. 2013, 42, 994–1014. doi:10.1007/s10964-012-9847-7. [Google Scholar]

-

Chirkov V, Ryan RM, Kim Y, Kaplan U. Differentiating autonomy from individualism and independence: A self-determination theory perspective on internalization of cultural orientations and well-being. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 84, 97–109. doi:10.1037//0022-3514.84.1.97. [Google Scholar]

-

Yu S, Gong Z, Shen Y, Wei J. A motivational perspective on the educational arms race in China: Self-determination in out-of-school educational training among Chinese students and their parents. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 43, 9116–9129. doi:10.1007/s12144-023-05034-w. [Google Scholar]

-

Vansteenkiste M, Ryan RM, Soenens B. Basic psychological need theory: Advancements, critical themes, and future directions. Motiv. Emot. 2020, 44, 1–31. doi:10.1007/s11031-019-09818-1. [Google Scholar]

-

Vansteenkiste M, Zhou M, Lens W, Soenens B. Experiences of autonomy and control among Chinese learners: Vitalizing or immobilizing? J. Educ. Psychol. 2005, 97, 468–483. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.97.3.468. [Google Scholar]

-

Yu S, Zhang F, Nunes LD, Levesque-Bristol C. Self-determined motivation to choose college majors, its antecedents, and outcomes: A cross-cultural investigation. J. Vocat. Behav. 2018, 108, 132–150. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2018.07.002. [Google Scholar]

-

Yu S, Zhang F, Nunes LD, Levesque-Bristol C. Doing Well vs. Doing Better: Preliminary Evidence for the Differentiation of the “Static” and “Incremental” Aspects of the Need for Competence. J. Happiness Stud. 2021, 23, 1121–1141. doi:10.1007/s10902-021-00442-w. [Google Scholar]

-

Yu S, Zhang F, Little TD. Measuring the rate of psychological growth and examining its antecedents: A growth curve modeling approach. J. Personal. 2023, 92, 530–547. doi:10.1111/jopy.12843. [Google Scholar]

-

Liu Y, Chai X, Gong S, Sang B. The influence of parents’ autonomous motivation on primary school students’ emotions in mathematics homework: The role of students’ autonomous motivation and teacher support. Psychol. Dev. Educ 2017, 33, 577–586. [Google Scholar]

-

Zhou M, Ren J. A self-determination perspective on Chinese fifth-graders’ task disengagement. Sch. Psychol. Int. 2017, 38, 149–165. doi:10.1177/0143034316684532. [Google Scholar]

-

Ma X, Zhao Y, Li Y, Yao F, Gong N. Xuexi Xiaonenggan, Ziwojueding Dongji Dui Xueye Qiwang De Zongyong: Jiyu Tonghe Moxing De Fenxi [the effects of academic efficacy, self-determined motivation on academic expectancy: An Analysis Based on Integrated Model]. Psychol. Tech. Appl. 2021, 9, 12–19. doi:10.16842/j.cnki.issn2095-5588.2021.01.002. [Google Scholar]

-

Jiang Y, Huang JH. The Influence of Autonomous Motivation on Leisure Physical Activity Intention of Chinese College Students Application of The Extended Model of Planned Behavior Theory. J. Posit. Sch. Psychol. 2022, 6, 7526–7539. [Google Scholar]

-

Chen J, King RB, Li Y, Xu W. The role of the research environment and motivation in PhD students’ well-being: A perspective from self-determination theory. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2024, 43, 809–826. doi:10.1080/07294360.2023.2269870. [Google Scholar]

-

Wang Y, Liu H. The mediating roles of buoyancy and boredom in the relationship between autonomous motivation and engagement among Chinese senior high school EFL learners. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 992279. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.992279. [Google Scholar]

-

Wang H, Wang L, Zhu J. Moderated mediation model of the impact of autonomous motivation on postgraduate Students’ creativity. Think. Ski. Creat. 2022, 43, 100997. doi:10.1016/j.tsc.2021.100997. [Google Scholar]

-

Yang L, Chiu HM, Sin KF, Lui M. The effects of school support on school engagement with self-determination as a mediator in students with special needs. Int. J. Disabil. Dev. Educ. 2022, 69, 399–414. doi:10.1080/1034912X.2020.1719046. [Google Scholar]

-

Gao J, Li M, Zhang W. Zhudongxing renge yu wangluo xuexi touru de guanxi: Ziwo jueding dongji lilun de shijiao (the relationship between proactive personality and online studying engagement: A self-determination theory perspective). E-Educ. Res. 2015, 36, 18–22. [Google Scholar]

-

Chen B, Vansteenkiste M, Beyers W, Boone L, Deci EL, Van der Kaap-Deeder J, et al. Basic psychological need satisfaction, need frustration, and need strength across four cultures. Motiv. Emot. 2015, 39, 216–236. doi:10.1007/s11031-014-9450-1. [Google Scholar]

-

Zhang X, Peng T, Hong Y, Luo J. Jiben xinli xuyao yu daxue xinsheng jiji qingxu de guanxi: Xingbie de tiaojie zuoyong (the relationship between basic psychological needs and positive affect among college freshmen: The moderating effect of gender). J. Dali Univ. 2021, 6, 123–128. doi:10.3969/j.issn.2096-2266.2021.03.021. [Google Scholar]

-

Xu Y. Chuzhongsheng jiben xinli xuyao manzu yu zizhu xuexi zhuangkuang xiangguan tanjiu (an investigation of the basic psychological needs satisfaction and self-regulated learning among middle school students). J. Heihe Univ. 2016, 7, 77–80. [Google Scholar]

-

Ganotice FA, Chan KMK, Chan SL, Chan SSC, Fan KKH, Lam MPS, et al. Applying motivational framework in medical education: A self-determination theory perspectives. Med. Educ. Online 2023, 28, 2178873. doi:10.1080/10872981.2023.2178873. [Google Scholar]

-

Liu H, Wang Y, Wang H. Exploring the mediating roles of motivation and boredom in basic psychological needs and behavioural engagement in English learning: A self-determination theory perspective. BMC Psychol. 2025, 13, 179. doi:10.1186/s40359-025-02524-3. [Google Scholar]

-

Zhang BG, Qian XF. Weight self-stigma and engagement among obese students in a physical education class. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 10. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1035827. [Google Scholar]

-

Zhou SA, Hiver P, Al-Hoorie AH. Dynamic engagement: A longitudinal dual-process, reciprocal-effects model of teacher motivational practice and L2 student engagement. Lang. Teach. Res. 2023, 29, 13621688231158789. doi:10.1177/13621688231158789. [Google Scholar]

-

Zhang X, Zhou M. Adolescents’ perceived ICT autonomy, relatedness, and competence: Examining relationships to intercultural competence in great China region. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2023, 28, 6801–6824. doi:10.1007/s10639-022-11463-0. [Google Scholar]

-

Xu M, Lu H, Guo Q. Research on the impact of basic psychological needs satisfaction on career adaptability of Chinese college students. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 8. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1275582. [Google Scholar]

-

Li Y, Chiu TKF. The mediating effects of needs satisfaction on the relationship between teacher support and student engagement with generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) chatbots from a self-determination theory (SDT) perspective. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2025, 30, 20051–20070. doi:10.1007/s10639-025-13574-w. [Google Scholar]

-

Shao X, Chen R, Wang Y, Zheng P, Huang Y. The Predictive Effect of Teachers’ Emotional Support on Chinese Undergraduate Students’ Online Learning Gains: An Examination of Self-determination Theory. Asia-Pac. Educ. Res. 2023, 33, 571–585. doi:10.1007/s40299-023-00754-w. [Google Scholar]

-

Xin ZY. Perceived social support and college student engagement: Moderating effects of a grateful disposition on the satisfaction of basic psychological needs as a mediator. BMC Psychol. 2022, 10, 298. doi:10.1186/s40359-022-01015-z. [Google Scholar]

-

Xu X, Wu Z, Wei D. The relationship between perceived teacher support and student engagement among higher vocational students: A moderated mediation model. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 11. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1116932. [Google Scholar]

-

Zhang BG, Qian XF. Perceived teacher’s support and engagement among students with obesity in physical education: The mediating role of basic psychological needs and autonomous motivation. J. Sports Sci. 2022, 40, 1901–1911. doi:10.1080/02640414.2022.2118935. [Google Scholar]

-

Lv G, Zhou Y. The mediating effect of prosocial behaviors and basic psychological needs on the relationship between eudaimonia orientation and happiness. Psychol. Tech. Appl. 2021, 9, 95–101. doi:10.16842/j.cnki.issn2095-5588.2021.02.004. [Google Scholar]

-

Lei Z, Wuyuntena, Jin T. The relationship between intrinsic life goals and subjective well-being of middle school students: The mediating role of basic psychological needs. Psychol. Tech. Appl. 2021, 9, 313–320. doi:10.16842/j.cnki.issn2095-5588.2021.05.007. [Google Scholar]

-

Li J, Zhang N, Yao M, Xing H, Liu H. Academic Social Comparison and Depression in Chinese Adolescents: The Mediating Role of Basic Psychological Needs Satisfaction. Sch. Ment. Health 2021, 13, 719–729. doi:10.1007/s12310-021-09436-8. [Google Scholar]

-

Chiu TKF. Applying the self-determination theory (SDT) to explain student engagement in online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Res. Technol. Educ. 2022, 54 (Suppl. S1), S14–S30. doi:10.1080/15391523.2021.1891998. [Google Scholar]

-

Zhou S, Zhu H, Zhou Y. Impact of Teenage EFL Learners’ Psychological Needs on Learning Engagement and Behavioral Intention in Synchronous Online English Courses. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10468. doi:10.3390/su141710468. [Google Scholar]

-

Bai X, Gu X. Contribution of self-determining theory to K–12 students’ online learning engagements: Research on the relationship among teacher support dimensions, students’ basic psychological needs satisfaction, and online learning engagements. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2024, 72, 2939–2961. doi:10.1007/s11423-024-10383-9. [Google Scholar]

-

Su CY, Chen CH. Investigating university students’ attitude and intention to use a learning management system from a self-determination perspective. Innov. Educ. Teach. Int. 2022, 59, 306–315. doi:10.1080/14703297.2020.1835688. [Google Scholar]

-

Hao Y, Lan Y. Research and practice of flipped classroom based on mobile applications in local universities from the perspective of self-determination theory. Front. Psychol. 2023, 13, 963226. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.963226. [Google Scholar]

-

Chiu TKF. School learning support for teacher technology integration from a self-determination theory perspective. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2022, 70, 931–949. doi:10.1007/s11423-022-10096-x. [Google Scholar]

-

Jiang L, Zang N, Zhou N, Cao H. English teachers’ intention to use flipped teaching: Interrelationships with needs satisfaction, motivation, self-efficacy, belief, and support. Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn. 2021, 35, 1890–1919. doi:10.1080/09588221.2020.1846566. [Google Scholar]

-

Tian L, Tian Q, Huebner ES. School-related social support and adolescents’ school-related subjective well-being: The mediating role of basic psychological needs satisfaction at school. Soc. Indic. Res. 2016, 128, 105–129. doi:10.1007/s11205-015-1021-7. [Google Scholar]

-

Wang Y, Tian L, Scott Huebner E. Basic psychological needs satisfaction at school, behavioral school engagement, and academic achievement: Longitudinal reciprocal relations among elementary school students. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2019, 56, 130–139. doi:10.1016/j.cedpsych.2019.01.003. [Google Scholar]

-

Zhou J, Jiang S, Zhu X, Huebner ES, Tian L. Profiles and transitions of dual-factor mental health among Chinese early adolescents: The predictive roles of perceived psychological need satisfaction and stress in school. J. Youth Adolesc. 2020, 49, 2090–2108. doi:10.1007/s10964-020-01253-7. [Google Scholar]

-

Zhou J, Huebner ES, Tian L. The reciprocal relations among basic psychological need satisfaction at school, positivity and academic achievement in Chinese early adolescents. Learn. Instr. 2021, 71, 101370. doi:10.1016/j.learninstruc.2020.101370. [Google Scholar]

-

Zhou J, Huebner ES, Tian L. Co-developmental trajectories of psychological need satisfactions at school: Relations to mental health and academic functioning in Chinese elementary school students. Learn. Instr. 2021, 74, 101465. doi:10.1016/j.learninstruc.2021.101465. [Google Scholar]

-

Yu S, Levesque-Bristol C, Maeda Y. General need for autonomy and subjective well-being: A meta-analysis of studies in the US and East Asia. J. Happiness Stud. 2017, 19, 1863–1882. doi:10.1007/s10902-017-9898-2. [Google Scholar]

-

Assor A. Allowing choice and nurturing an inner compass: Educational practices supporting students’ need for autonomy. In Handbook of Research on Student Engagement; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2012; pp. 421–439. [Google Scholar]

-

Mair V. Empty Heart Disease. 2016. Available online: https://languagelog.ldc.upenn.edu/nll/?p=29515 (accessed on 12 December 2025). [Google Scholar]

-

Assor A, Benita M, Shi Y, Goren R, Yitshaki N, Wang Q. The Authentic Inner Compass as a Well-Being Resource: Predictive Effects on Vitality, and Relations with Self-Esteem, Depression and Behavioral Self-realization. J. Happiness Stud. 2021, 22, 3435–3455. doi:10.1007/s10902-021-00373-6. [Google Scholar]

-

Assor A, Cohen R, Ezra O, Yu S. Feeling Free and Having an Authentic Inner Compass as Important Aspects of the Need for Autonomy in Emerging Adults’ Interactions with their Mothers. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 1792. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.635118. [Google Scholar]

-

Yu S, Deng Y, Yu H, Liu X. Attachment avoidance moderates the effects of parenting on Chinese adolescents’ having an inner compass. Curr. Psychol. 2018, 40, 887–894. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-018-0007-4. [Google Scholar]

-

Yu S, Assor A, Liu X. Perception of parents as demonstrating the inherent merit of their values: Relations with self-congruence and subjective well-being. Int. J. Psychol. 2015, 50, 70–74. doi:10.1002/ijop.12074. [Google Scholar]

-

Bao Z. Chuzhongsheng Waizai Xuexi Dongji Neihua De Shiyan Yanjiu [The Experimental Research on Internalization of Extrinsic Learning Motivation of Students at Junior High School]. Doctoral Dissertation, Northeast Normal University, Changchun, China, 2006. [Google Scholar]

-

Bao Z, Zhang X. Chuzhongsheng Waizai Xuexi Dongji Neihua De Xinli Jizhi Yanjiu [The mental mechanisms of junior high school students’ internalization of extrinsic learning motivation]. Psychol. Sci. 2008, 31, 580–583. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1671-6981.2008.03.015. [Google Scholar]

-

Lau KL. Within-year changes in Chinese secondary school students’ perceived reading instruction and intrinsic reading motivation. J. Res. Read. 2014, 39, 153–170. doi:10.1111/1467-9817.12035. [Google Scholar]

-

Zhou M, Ma WJ, Deci EL. The importance of autonomy for rural Chinese children’s motivation for learning. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2009, 19, 492–498. doi:10.1016/j.lindif.2009.05.003. [Google Scholar]

-

Zhou N, Lam SF, Chan KC. The Chinese classroom paradox: A cross-cultural comparison of teacher controlling behaviors. J. Educ. Psychol. 2012, 104, 1162–1174. doi:10.1037/a0027609. [Google Scholar]

-

Cheung SS. The Role of Parents’ Control and Autonomy Support in the United States and China: Beyond Children’s Reports. Doctoral Dissertation, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign: Champaign, IL, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

-

Lekes N, Gingras I, Philippe FL, Koestner R, Fang J. Parental autonomy-support, intrinsic life goals, and well-being among adolescents in China and North America. J. Youth Adolesc. 2010, 39, 858–869. doi:10.1007/s10964-009-9451-7. [Google Scholar]

-

Li D, Zhang W, Li D, Wang Y. Fumu xingwei kongzhi, xinli kongzhi yu qingshaonian zaoqi gongji he tuisuo de guanxi [The relationship between parental behavioral control, psychological control, and agression and social withdrawal in early adolescence]. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 2012, 28, 201–209. [Google Scholar]

-

Tong Y. Unpacking Chinese Parenting Paradox: A Cross-Cultural Inquiry of Children’s Affective Feelings Towards Maternal Involvement. Master’s Thesis, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

-

Wang Q, Pomerantz EM, Chen H. The role of parents’ control in early adolescents’ psychological functioning: A longitudinal investigation in the United States and China. Child Dev. 2007, 78, 1592–1610. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01085.x. [Google Scholar]

-

Jiang AL, Zhang LJ. University teachers’ teaching style and their students’ agentic engagement in EFL learning in China: A self-determination theory and achievement goal theory integrated perspective. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 704269. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.704269. [Google Scholar]

-

Xu J, Du J, Cunha J, Rosário P. Student perceptions of homework quality, autonomy support, effort, and math achievement: Testing models of reciprocal effects. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2021, 108, 103508. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2021.103508. [Google Scholar]

-

Chiu TKF. Using self-determination theory (SDT) to explain student STEM interest and identity development. Instr. Sci. 2023, 52, 89–107. doi:10.1007/s11251-023-09642-8. [Google Scholar]

-

Lu L, Gao X, Xiao Y. Impact of college students’ perceived teacher support on career exploration: A Self-Determination Theory approach. Innov. Educ. Teach. Int. 2022, 61, 528–540. doi:10.1080/14703297.2022.2147093. [Google Scholar]

-

Wang R. Investigating Perception of Teacher’s Autonomy Support on Creativity of Junior High School Students: Comparison of Urban Schools and Rural Schools from Shaanxi Province of China. Doctoral Dissertation, Dhurakij Pundit University, Bangkok, Thailand, 2022. [Google Scholar]

-

Peng X, Sun X, He Z. Influence Mechanism of Teacher Support and Parent Support on the Academic Achievement of Secondary Vocational Students. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 17. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.863740. [Google Scholar]

-

Wang F, Zeng LM, King RB. Teacher support for basic needs is associated with socio-emotional skills: A self-determination theory perspective. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 2025, 28, 76. doi:10.1007/s11218-024-10009-1. [Google Scholar]

-

Zhang D, Jin B, Cui Y. Do Teacher Autonomy Support and Teacher–Student Relationships Influence Students’ Depression? A 3-Year Longitudinal Study. Sch. Ment. Health 2021, 14, 110–124. doi:10.1007/s12310-021-09456-4. [Google Scholar]

-

Xia Q, Chiu TKF, Lee M, Sanusi IT, Dai Y, Chai CS. A self-determination theory (SDT) design approach for inclusive and diverse artificial intelligence (AI) education. Comput. Educ. 2022, 189, 104582. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2022.104582. [Google Scholar]

-

OECD. PISA: Programme for International Student Assessment; OECD: Paris, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

-

Wang Y, King RB, Wang F, Leung SO. Need-supportive teaching is positively associated with students’ well-being: A cross-cultural study. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2021, 92, 102051. doi:10.1016/j.lindif.2021.102051. [Google Scholar]

-

Nalipay MJN, King RB, Cai Y. Autonomy is equally important across East and West: Testing the cross-cultural universality of self-determination theory. J. Adolesc. 2020, 78, 67–72. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2019.12.009. [Google Scholar]

-

Li R, Yao M, Liu H, Chen Y. Chinese parental involvement and adolescent learning motivation and subjective well-being: More is not always better. J. Happiness Stud. 2020, 21, 2527–2555. doi:10.1007/s10902-019-00192-w. [Google Scholar]

-

Ching BHH, Wu HX, Chen TT. Maternal achievement-oriented psychological control: Implications for adolescent academic contingent self-esteem and mathematics anxiety. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2021, 45, 193–203. doi:10.1177/0165025420981638. [Google Scholar]

-

Wei J. Academic Contingent Self-Worth of Adolescents in Mainland China: Distinguishing Between Success and Failure as a Basis of Self-Worth; The Chinese University of Hong Kong (Hong Kong): Hong Kong, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

-

Chen HY, Ng J, Pomerantz EM. Why is self-esteem higher among American than Chinese early adolescents? The role of psychologically controlling parenting. J. Youth Adolesc. 2021, 50, 1856–1869. doi:10.1007/s10964-021-01474-4. [Google Scholar]

-

Li J, Deng M, Wang X, Tang Y. Teachers’ and parents’ autonomy support and psychological control perceived in junior-high school: Extending the dual-process model of self-determination theory. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2018, 68, 20–29. doi:10.1016/j.lindif.2018.09.005. [Google Scholar]

-

Zhou LH, Ntoumanis N, Thøgersen-Ntoumani C. Effects of perceived autonomy support from social agents on motivation and engagement of Chinese primary school students: Psychological need satisfaction as mediator. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2019, 58, 323–330. doi:10.1016/j.cedpsych.2019.05.001. [Google Scholar]

-

Wang Y, Qiao D, Chui E. Student engagement matters: A self-determination perspective on Chinese MSW students’ perceived competence after practice learning. Br. J. Soc. Work 2018, 48, 787–807. doi:10.1093/bjsw/bcx015. [Google Scholar]

-

Zhong H, Liu YS. Mediation effect of basic psychological needs on relationship between perceived autonomy support and happiness among undergraduates. Chin. J. Public Health 2019, 35, 223–225. doi:10.11847/zgggws1119961. [Google Scholar]

-

Xu D, Yu C, Dou K, Liang Z, Li Z, Nie Y. Parental Autonomy Support and Adolescents’ Future Planning: The Mediating Role of Basic Psychological Needs and Personal Growth Initiative. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 2019, 35, 23–31. [Google Scholar]

-

Cao J, Li X, Ye Z, Xie M, Lin D. Parental psychological and behavioral control and positive youth development among young Chinese adolescents: The mediating role of basic psychological needs satisfaction. Curr. Psychol. 2020, 41, 4645–4656. doi:10.1007/s12144-020-00980-1. [Google Scholar]

-

Du W, Li Z, Xu Y, Chen C. The Effect of Parental Autonomy Support on Grit: The Mediating Role of Basic Psychological Needs and the Moderating Role of Achievement Motivation. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2023, 16, 939–948. doi:10.2147/PRBM.S401667. [Google Scholar]

-

Peng C, Wang LX, Guo Z, Sun P, Yao X, Yuan M, et al. Bidirectional Longitudinal Associations between Parental Psychological Control and Peer Victimization among Chinese Adolescents: The Mediating Role of Basic Psychological Need Satisfaction. J. Youth Adolesc. 2023, 53, 967–981. doi:10.1007/s10964-023-01910-7. [Google Scholar]

-

Yu S, Assor A, Yu H, Wang Q. Autonomy as a potential moral resource: Parenting practices supporting youth need for autonomy negatively predict youth acceptance of academic dishonesty. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2023, 101, 102245. doi:10.1016/j.lindif.2022.102245. [Google Scholar]

-

Huang J, Zhang D, Chen Y, Yu C, Zhen S, Zhang W. Parental psychological control, psychological need satisfaction, and non-suicidal self-injury among Chinese adolescents: The moderating effect of sensation seeking. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2022, 136, 106417. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2022.106417. [Google Scholar]

-

Wang G, Zhao Y. Meta-analysis about Teacher Autonomy-support and Student Academic Achievement: The Mediation of Psychological Need Satisfaction, Motivation and Engagement. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 2022, 38, 380–390. [Google Scholar]

-

Helwig CC, To S, Wang Q, Liu C, Yang S. Judgments and reasoning about parental discipline involving induction and psychological control in China and Canada. Child Dev. 2014, 85, 1150–1167. doi:10.1111/cdev.12183. [Google Scholar]

-

Chen B, Soenens B, Vansteenkiste M, Van Petegem S, Beyers W. Where do the cultural differences in dynamics of controlling parenting lie? Adolescents as active agents in the perception of and coping with parental behavior. Psychol. Belg. 2016, 56, 169–192. doi:10.5334/pb.306. [Google Scholar]

-

Soenens B, Park SY, Mabbe E, Vansteenkiste M, Chen B, Van Petegem S, et al. The moderating role of vertical collectivism in South-Korean adolescents’ perceptions of and responses to autonomy-supportive and controlling parenting. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 1080. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01080. [Google Scholar]

-