Large-Scale Language Model Assisted Construction of Multi-Source Heterogeneous Knowledge Graphs for Marine Renewable Energy

Received: 10 December 2025 Revised: 17 December 2025 Accepted: 09 January 2026 Published: 14 January 2026

© 2026 The authors. This is an open access article under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

1. Introduction

The global energy structure is accelerating its transition toward cleaner and low-carbon systems. Marine renewable energy, especially offshore wind power and photovoltaic (PV) installations, has progressed into a new phase marked by large deployment, deep-sea development, and intelligent operation [1,2,3,4]. In operation monitoring, fault diagnosis, and other maintenance activities of wind farms and PV plants, substantial volumes of unstructured or semi-structured textual data are continuously generated. These data include industry standards, maintenance procedures, equipment technical manuals, project documents, corrosion inspection records, and meteorological and oceanographic reports. Such information contains critical operational characteristics and maintenance knowledge, forming a fundamental basis for predictive maintenance, improved equipment availability, and reduced operational costs [5,6].

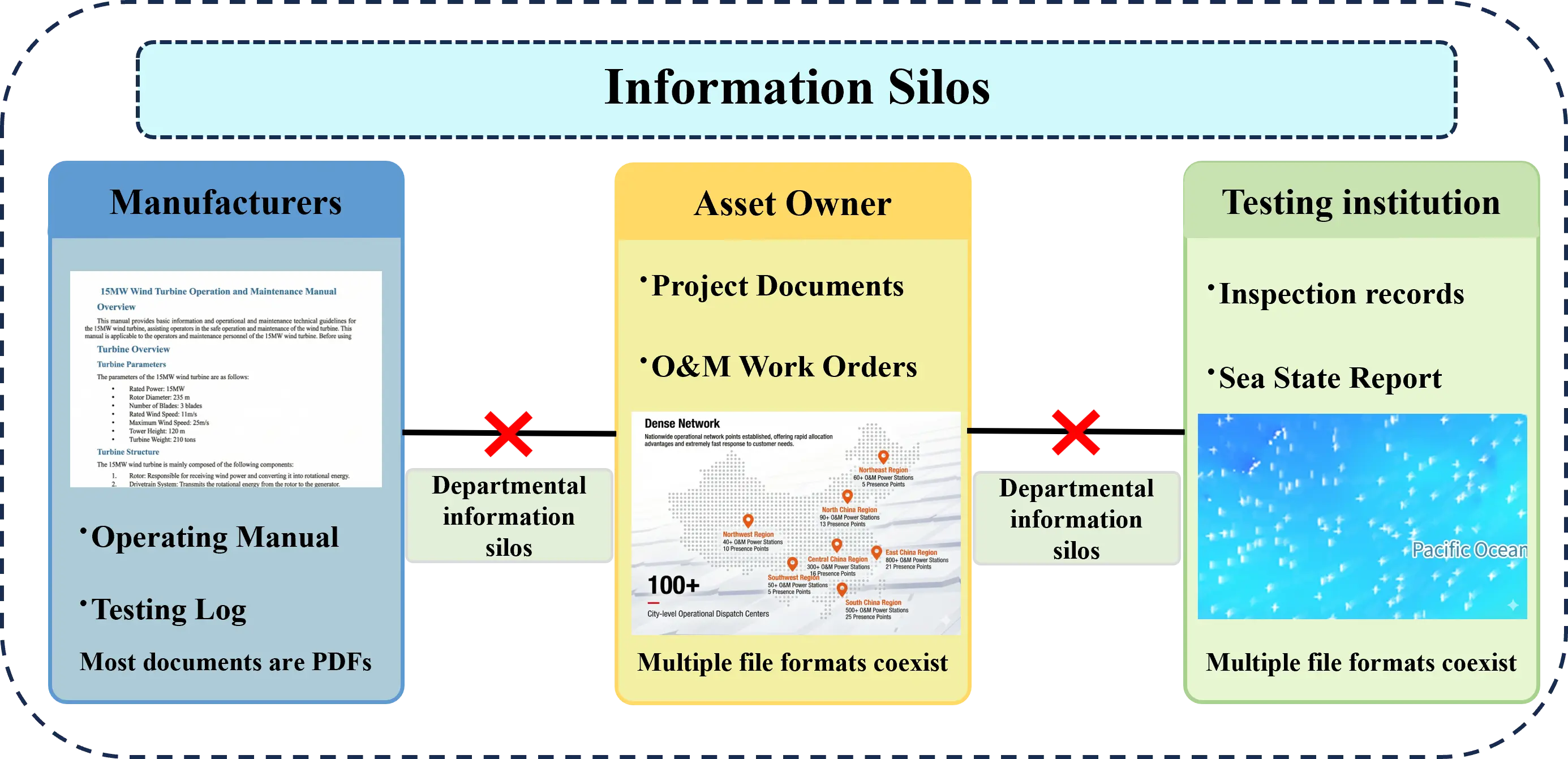

However, maintenance knowledge remains fragmented due to dispersed data sources (manufacturers, asset owners, and third-party inspection agencies) and significant data heterogeneity. We explicitly define this heterogeneity in two dimensions: format diversity (ranging from digital Word documents to scanned PDFs containing optical noise) and semantic variability (spanning from rigid technical manuals to unstructured, informal daily logs). Coupled with the complexity of domain-specific terminology, these factors create substantial barriers. Traditional rule-based or standard NLP models often fail in this context, as their performance depends heavily on the distribution of general pre-training data. Consequently, they struggle to generalize to the marine energy domain, where an abundance of specialized terminology leads to suboptimal extraction results. As a result, large amounts of knowledge exist only as isolated pieces of text and cannot be systematically organized or effectively reused. This situation reinforces information silos, prevents the accumulation of historical fault experience, leads to repeated diagnosis of similar issues, and limits the knowledge support required for maintenance strategies. These challenges significantly hinder the automation and intelligence levels of marine renewable energy operations and maintenance (O&M) [7], as illustrated in Figure 1.

Against this background, a technical pathway capable of automatically extracting structured knowledge from multi-source heterogeneous data and revealing semantic associations is required. As a structured knowledge representation method, the knowledge graph uses a semantic network of “entity–relation–entity” to model components, failure modes, environmental conditions, and maintenance activities in a unified manner. This representation provides an interpretable and searchable knowledge foundation for fault tracing, case-based reasoning, and decision support, and demonstrates substantial application potential in intelligent O&M [8].

However, constructing knowledge graphs for marine renewable energy O&M remains a substantial challenge. Conventional natural language processing methods show limited domain adaptability when dealing with highly specialized texts, and often fail to capture relationships among technical terms or correctly identify abbreviations and terminology variations. In addition, their performance depends heavily on manual annotation, which is costly and difficult to maintain in continuously evolving maintenance scenarios [9]. In recent years, large-scale language models have demonstrated significant advantages in information extraction due to their strong contextual semantic understanding and few-shot generation capabilities. When combined with structured prompt engineering designed for intelligent O&M, large-scale language models can accurately identify entities and extract engineering-relevant relational triples from raw text. This capability offers a new, efficient, and feasible paradigm for automated knowledge graph construction [10,11].

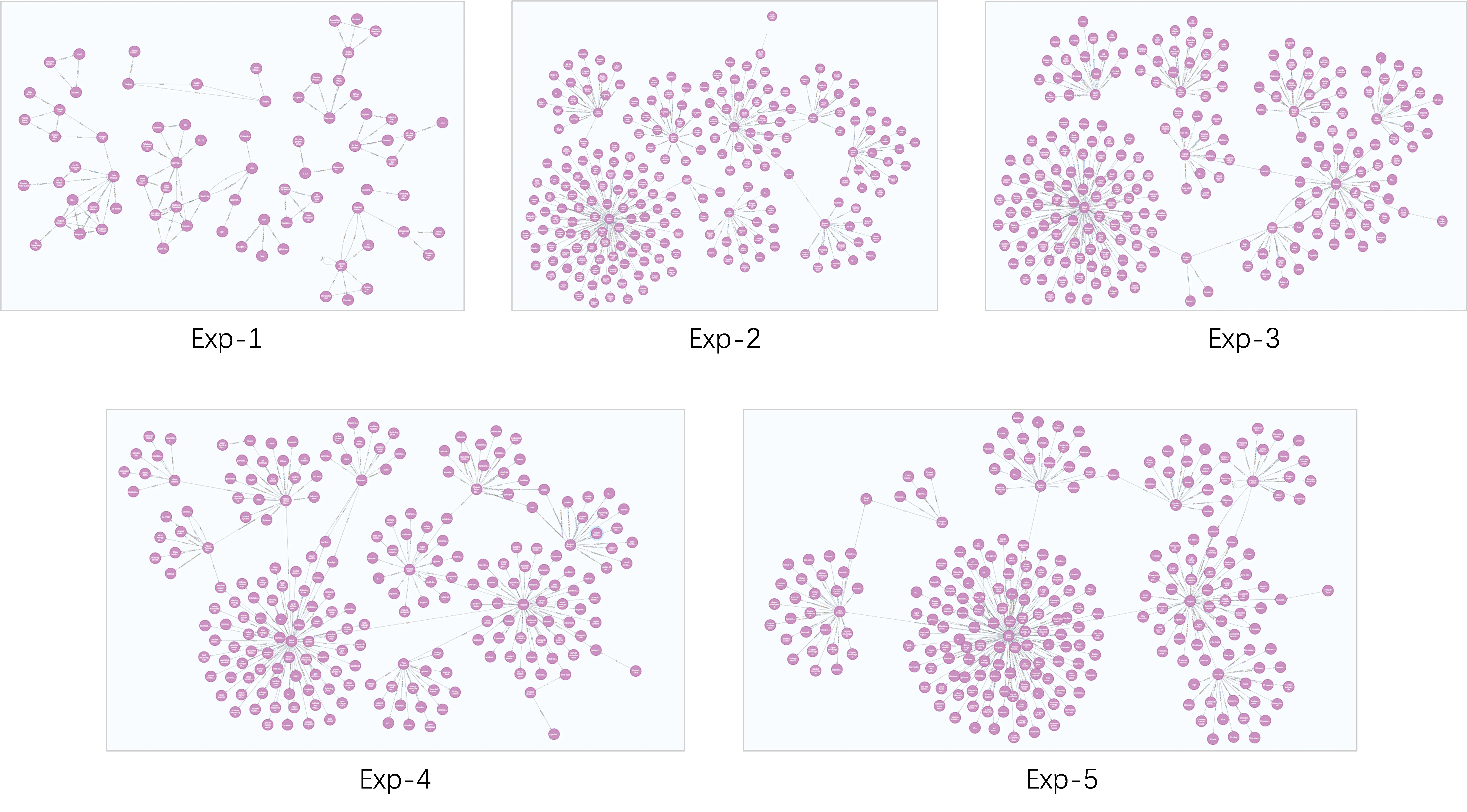

To address the above issues, this study proposes a knowledge graph construction method for intelligent operation and maintenance of marine renewable energy systems, assisted by large-scale language models. The method integrates multiple data sources, including maintenance work orders, fault analysis reports, technical manuals, relevant logs, patents, and academic publications. A unified preprocessing workflow converts heterogeneous formats, such as PDFs, Word documents, and scanned documents, into sentence-level corpora with complete semantics. Prompt templates tailored for maintenance scenarios are then designed to guide large-scale language models in entity recognition and relation extraction. Furthermore, rule-based processing, domain dictionaries, and semantic entity normalization mechanisms are incorporated to address terminology heterogeneity. The resulting knowledge graph enables the structured organization of key entities and semantic relations contained in multi-source heterogeneous maintenance texts in the offshore wind and PV domains. It systematically consolidates essential knowledge elements such as equipment information, fault phenomena, environmental factors, and maintenance actions. It also provides a foundational knowledge-representation framework for downstream applications, including fault retrieval and maintenance-strategy recommendation. Finally, distinct from static knowledge bases that require complete rebuilding for updates, this study structurally enables dynamic evolution. While not implementing real-time data streaming, the framework supports incremental extraction, allowing the knowledge graph to grow continuously as new maintenance logs are digitized and processed, ensuring the system remains current without the computational cost of full-scale reconstruction. To rigorously validate these components, a systematic ablation study (Exp-1 to Exp-5) is employed to decouple the effects of preprocessing and prompting strategies, demonstrating the necessity of each module for handling heterogeneous marine data.

2. Proposed Methodology

2.1. Overall Framework

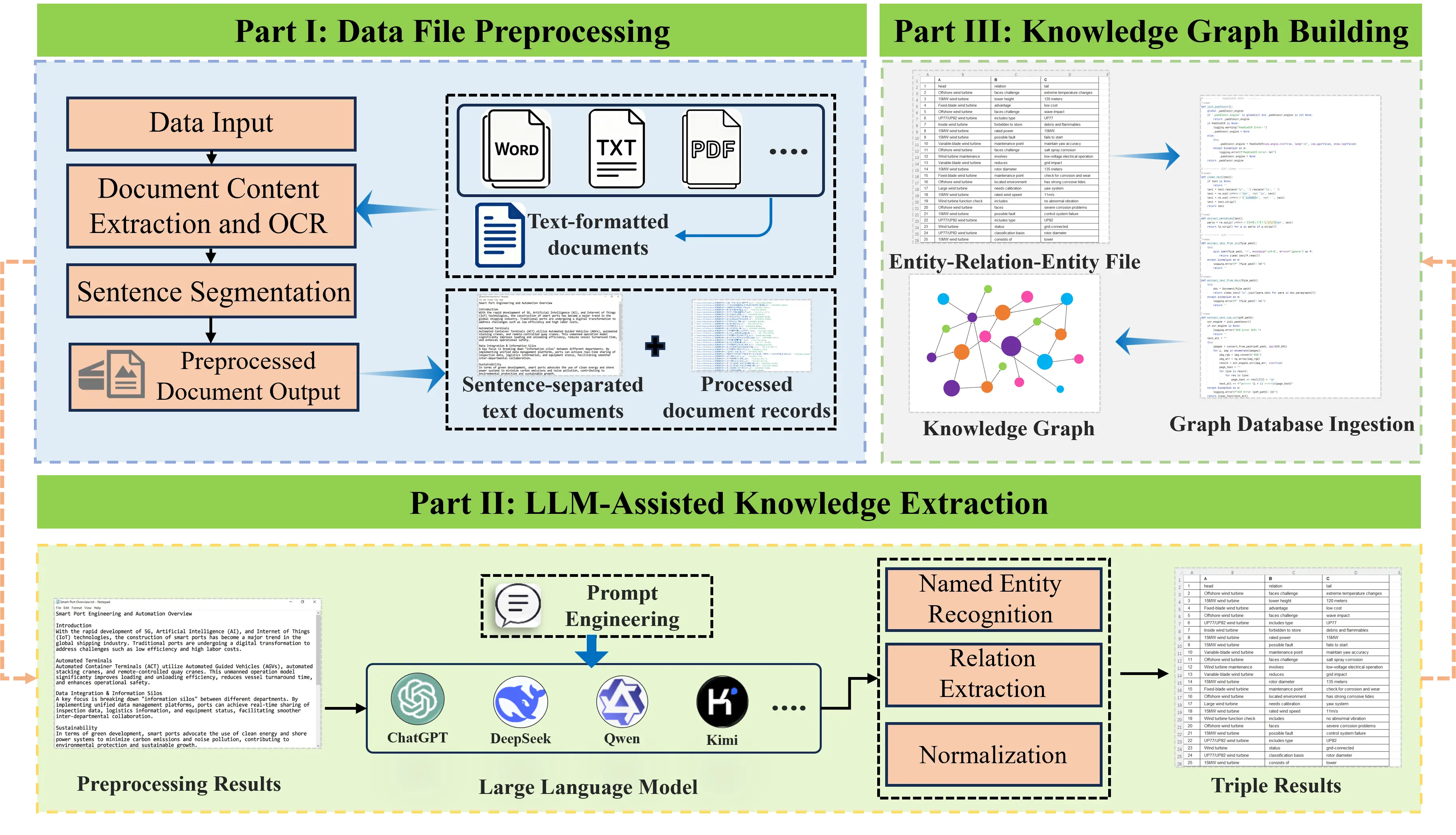

The construction of knowledge graphs for intelligent operation and maintenance in the marine renewable energy domain faces three main challenges: highly heterogeneous data sources, strong domain-specific semantic expressions, and dynamically evolving knowledge structures. To tackle these issues, this study presents a large-scale language model assisted approach for building knowledge graphs from multi-source heterogeneous data in marine renewable energy intelligent maintenance. The overall technical framework is illustrated in Figure 2 and comprises three closely linked core stages:

Multi-source heterogeneous data preprocessing: To address the complex formats and noisy characteristics of marine renewable energy maintenance documents, a unified workflow for document parsing, cleaning, segmentation, and semantic filtering is designed. This process converts raw heterogeneous data into sentence-level corpora with clear structure and complete semantics.

Knowledge extraction based on large-scale language models: Leveraging the powerful semantic understanding and generation capabilities of large-scale language models, combined with maintenance-scenario-oriented prompt engineering, structured triples are automatically extracted from the preprocessed sentences. An entity-normalization mechanism is incorporated to resolve terminology diversity [12].

Knowledge graph construction and dynamic expansion: The extracted results are mapped into a graph structure to build a knowledge graph that supports querying and inference. An incremental update mechanism is designed to support the continuous evolution of the graph with new data.

The framework follows the main line of “data-driven—model-enabled—graph deployment”. It inherits the classical paradigm of knowledge graphs construction while deeply integrating generative AI techniques. Specifically, it provides an end-to-end automated solution tailored to the fragmented, domain-specific, and frequently updated nature of engineering feasibility data.

2.2. Multi-Source Document Reading and Preprocessing

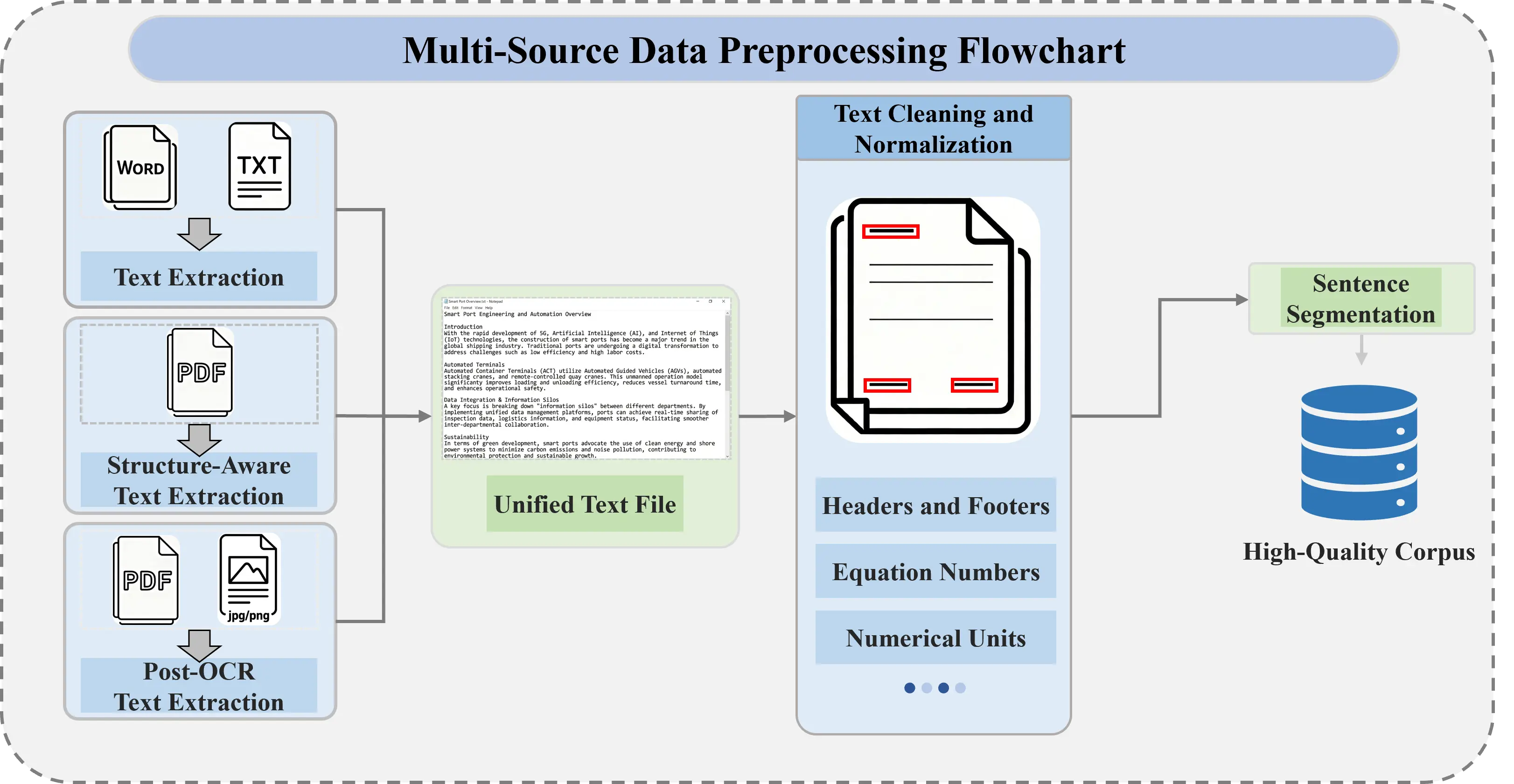

Data used in intelligent O&M of marine renewable energy systems naturally exhibit strong multi-source heterogeneity. Maintenance work orders are often stored in Word or Excel formats; fault reports are typically archived as PDFs; equipment manuals may contain scanned drawings; corrosion inspection records are produced by third-party agencies in inconsistent formats; and meteorological bulletins frequently combine tables with free text. Directly feeding such raw data into a knowledge-extraction module would introduce substantial noise and semantic distortion. Therefore, this study designs a systematic preprocessing workflow tailored to marine renewable energy maintenance scenarios, aiming to achieve unified formatting, content purification, and semantic focusing, as illustrated in Figure 3.

2.2.1. Document Parsing and Format Normalization

A differentiated parsing strategy is applied according to the characteristics of each data source: unstructured documents (e.g., .docx) are directly parsed to extract the main text, digitally generated PDFs are processed via their embedded text layer, and scanned files are converted using optical character recognition (OCR) [13]. To avoid redundant processing during incremental updates, a unique identifier is assigned to each document upon its first ingestion, and its processing status is recorded. This identifier serves as workflow control metadata, ensuring that only previously unseen files are handled when new data are introduced, thereby maintaining the efficiency of the preprocessing pipeline.

2.2.2. Text Cleaning and Normalization

This stage focuses on removing noise that is typical in engineering documents, including headers and footers, reference markers, equation numbers, and fragmented short tokens caused by line breaks. Numerical units, technical symbols, and chemical formulas are further standardized and converted to the International System of Units to improve consistency across data from different sources.

2.2.3. Semantic-Oriented Sentence Segmentation and Filtering

The documents are segmented into semantically complete sentence units. Content with no knowledge value, such as signature blocks, distribution lists, and attachment descriptions, is removed, and only sentences containing essential information are retained. This strategy significantly increases the information density of the input corpus and provides a solid foundation for high accuracy knowledge extraction.

Finally, the preprocessing results are stored in a structured format, with each sentence linked to its original source and location, forming a high quality, traceable, and engineering-oriented sentence level corpus.

2.3. Knowledge Extraction Based on Large-Scale Language Models

After completing the preprocessing of multi-source heterogeneous documents, the system proceeds to the knowledge extraction stage. The primary objective of this stage is to automatically identify and structure “entity–relation–entity” triples from semantically complete sentences, thereby generating high quality knowledge units for knowledge graph construction. Traditional methods often rely on manually annotated corpora or predefined rule templates [14]. However, when applied to engineering operation and monitoring texts, these approaches typically suffer from limited generalization and poor adaptability. Such texts contain dense terminology, complex sentence structures, and implicit logical dependencies [15].

To address these limitations, this study introduces a large-scale language model as a generative knowledge extraction engine. By leveraging its strong contextual understanding, semantic reasoning, and structured generation capabilities, the system achieves an end-to-end mapping from unstructured text to standardized knowledge representations.

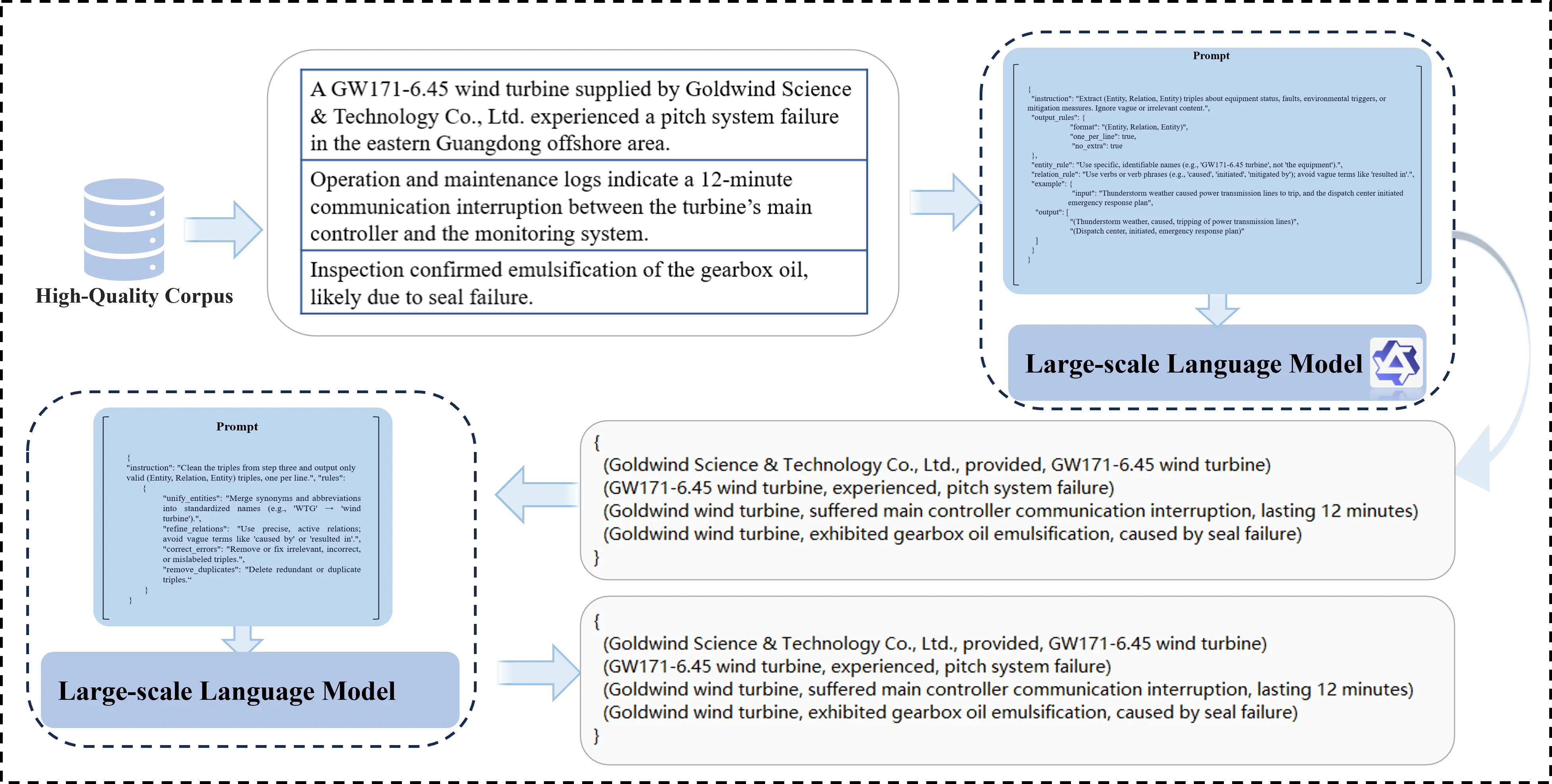

To address the specialized and diverse nature of knowledge expressions in marine renewable energy O&M, this study develops a domain adapted prompt engineering framework, as illustrated in Figure 4. The framework employs structured prompts to guide the model toward key technical elements, ensuring a balanced outcome in terms of semantic accuracy, structural consistency, and domain alignment. Moreover, to mitigate the high heterogeneity of terminology, a multi-level entity-normalization mechanism is applied after extraction. This mechanism addresses issues such as the coexistence of full names, abbreviations, and informal names for the same material. This mechanism effectively reduces graph fragmentation caused by naming inconsistencies. The final extraction results are exported in a standardized format, providing structured inputs that can be directly mapped to the knowledge graph construction process [16].

2.3.1. Prompt Design and Task Definition

O&M texts in the marine renewable energy domain often contain extensive technical terminology, abbreviations, and complex causal sentence structures. Directly applying a general-purpose large-scale language model for open-ended generation may cause the output to deviate from the intended knowledge structure. Therefore, this study designs a structured prompt template that clearly defines task boundaries and output formats, guiding the model to follow the semantic conventions of O&M knowledge during generation.

The core elements of the prompt template include:

Entity-type constraints: Restricting the recognizable entity categories to high-frequency semantic units in O&M texts, such as materials, methods, equipment, experimental conditions, performance metrics, research problems, and technical parameters.

Relation-semantic guidance requires relations to be expressed as verb-like phrases, such as ‘enhances’, ‘leads to’, ‘adopts’, ‘is applicable to’, or ‘depends on’, to capture technical logic with interpretability and reasoning value.

Output-format specification: Enforcing a structured list format for all extracted triples, where each item contains the fields “head”, “relation”, and “tail”, facilitating downstream automated processing.

For instance, for the sentence: “At 300 °C, the tensile strength of Material A shows a significant improvement”, the model is expected to produce:

[{“head”: “Material A”, “relation”: “improves”, “tail”: “tensile strength”}]

Through explicit task definitions and format constraints, this design transforms the open-ended generative capabilities of large-scale language models into a controllable, reusable knowledge-extraction tool, significantly enhancing its applicability in specialized domains.

2.3.2. Sentence-by-Sentence Processing and Validity Filtering

Knowledge extraction operates on preprocessed sentences as the smallest processing unit, feeding each sentence individually into the large-scale language model for reasoning. Considering that O&M documents contain substantial non-knowledge content, such as material lists or approval signatures, this study introduces a semantic validity filtering mechanism. Knowledge extraction is triggered only when a sentence includes explicit technical statements such as causal relationships or anomaly descriptions; otherwise, the model returns an empty result.

This strategy not only avoids unnecessary computation, thereby improving overall processing efficiency, but also effectively reduces the introduction of noisy triples, ensuring the purity and reliability of the knowledge base.

2.3.3. Entity Normalization and Synonym Merging

In the marine energy domain, the same concept often appears in multiple forms due to differing sources or conventions. For example, “#03 Wind Turbine”, “WTG-03”, and “Unit 3” all refer to the same device. “Cathodic protection”, “CP system”, and “sacrificial anode” may be used interchangeably in specific contexts. Without normalization, these variations can lead to redundant nodes and fragmented semantics in the knowledge graph.

To address this issue, this study does not adopt the traditional post-processing normalization workflow. Instead, the normalization logic is integrated into the prompt design stage. Specifically, standard terminology is explicitly defined within the structured prompt template, and the large-scale language model is instructed to use the standardized names directly when generating triples.

In this way, the model performs term normalization simultaneously during knowledge extraction, achieving an integrated process of “extraction and standardization”. This strategy not only simplifies the system workflow by eliminating the need for an additional post-processing module but also significantly reduces the risk of graph fragmentation caused by term variations.

2.3.4. Result Storage and Database Import Preparation

After completing knowledge extraction and entity normalization, all triples are uniformly stored in a structured tabular file. Each row contains the head entity, the relation, the tail entity, and the necessary normalization identifiers. This format offers a clear structure and strong compatibility, facilitating cross-platform exchange and manual verification. Moreover, it can be directly used as a bulk import interface for graph databases, avoiding complex intermediate conversions.

2.4. Knowledge Graph Construction and Expansion

After obtaining structured triples, the system proceeds to the knowledge graph construction stage. The objective of this stage is to organize discrete knowledge units into a unified graph structure, forming a knowledge network that supports efficient querying, semantic reasoning, and dynamic evolution. Considering that knowledge in the marine renewable energy domain involves multi-source integration, continuous updates, and complex interrelations, this study designs a knowledge graph construction and expansion method tailored for dynamic evolution.

2.4.1. Data Mapping and Node Reuse

The structured triple file serves as direct input for knowledge graph construction and is first parsed into entity–relation pairs by the system. During the mapping process, each entity undergoes a uniqueness check: if the entity does not yet exist in the graph, a new node is created; if it already exists, the existing node is reused to avoid redundancy. Each relation is then mapped as a directed edge connecting the two entities, completing the topological construction of the knowledge graph.

This mapping mechanism ensures a seamless transformation of extracted results into a graph structure, while the node-reuse strategy maintains the compactness and consistency of the knowledge graph.

2.4.2. Knowledge Graph Construction and Visualization

After data import is completed, the system generates a preliminary intelligent O&M knowledge graph for the marine renewable energy domain. In this graph, nodes represent core O&M elements, and directed edges denote technical semantic relationships, forming a semantic network that integrates multi-source heterogeneous knowledge. Users can intuitively explore knowledge paths through the visualization interface of the graph database. Additionally, the system supports complex semantic queries based on graph query languages, such as “find all information related to entity X”, enabling O&M personnel to efficiently retrieve target entities and their associated information from massive datasets.

2.4.3. Incremental Updates and Dynamic Expansion

Knowledge in the marine renewable energy domain is highly dynamic, with new inspection findings, maintenance experiences, and environmental events continuously emerging. To avoid the problem of a “one-time construction and rapid obsolescence” of the knowledge graph, this study designs an incremental knowledge update mechanism:

- (1)

-

When a new batch of triples is input, the system automatically identifies newly added entities and relations.

- (2)

-

Uniqueness checks for nodes and relations ensure that existing knowledge is not duplicated.

- (3)

-

Dynamic supplementation of existing node attributes is supported (e.g., adding new performance data or updating experimental parameters).

This mechanism endows the knowledge graph with “self-growing” capabilities, allowing it to continuously evolve with O&M data and remain synchronized with field conditions, thereby serving as a dynamic knowledge infrastructure for predictive maintenance, intelligent diagnostics, and knowledge accumulation in offshore wind operations.

3. Experimental Design

To validate the effectiveness of the proposed large-scale language model assisted method for constructing a knowledge graph from multi-source heterogeneous data in the marine renewable energy domain, a series of comparative experiments was designed. The aim was to systematically evaluate the impact of document preprocessing strategies, knowledge-extraction model selection, and prompt engineering on the final quality of the knowledge graph. The experiments were based on historical O&M documents from actual offshore wind farms and PV plants, using a manually curated standard triple set as a reference. A comprehensive evaluation was conducted from both objective quantitative metrics and subjective visualization analysis perspectives.

3.1. Dataset Construction

The experimental data were sourced from O&M archival records of an offshore wind farm and a PV park along the coast. The dataset includes typical document types such as industry standards, maintenance procedures, equipment technical manuals, project-related materials, corrosion inspection records, and meteorological and sea-condition reports, exhibiting pronounced multi-source heterogeneous characteristics. The original dataset comprises 50 files, with the following format distribution, summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Distribution of Data File Formats.

|

Format |

Quantity |

Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

|

Scanned PDF (including official seals and handwritten signatures) |

23 |

Unstructured, requires OCR recognition, text quality varies |

|

Digitized PDF |

15 |

Semi-structured, text content can be directly extracted, but the quality is moderate. |

|

Word (.doc/.docx) |

12 |

Structured clearly, the text can be directly extracted, and of good quality |

The contents of all files include critical information such as project numbers, key components, fault phenomena, maintenance measures, and environmental impacts, providing the rich semantics necessary for constructing “entity–relation–entity” triples.

3.2. Experimental Group Design

To systematically evaluate the impact of document preprocessing and knowledge-extraction models on the construction of multi-source heterogeneous knowledge graphs in engineering feasibility studies, five comparative experimental groups were designed. These experiments cover three dimensions: “traditional extraction framework vs. large-scale language model”, “raw data vs. preprocessed data”, and “zero-shot prompts vs. optimized prompt engineering”, forming a complete ablation study framework. Each experimental group follows a unified output specification: starting from the original files, the data undergoes the designated processing workflow, resulting in a structured set of triples, which are then imported into Neo4j 2025.04.0 to construct the knowledge graph [17]. The experimental design is summarized in Table 2.

Table 2. Experimental Design.

|

Experiment Group |

Document Preprocessing |

Knowledge Extraction Method |

Core Objective |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Exp-1 |

Yes |

DeepKE |

Baseline of the traditional pipeline |

|

Exp-2 |

No |

Qwen-plus-latest (Zero-shot Prompting) |

Zero-shot knowledge extraction from raw documents |

|

Exp-3 |

Yes |

Qwen-plus-latest (Zero-shot Prompting) |

Impact of preprocessing on zero-shot LLM performance |

|

Exp-4 |

Yes |

Qwen-plus-latest (Optimized Prompt Engineering) |

Peak performance of the full workflow |

|

Exp-5 |

Yes |

DeepSeek-chat (Same Optimized Prompting) |

Generalizability of optimized prompts |

DeepKE is an open-source and extensible knowledge extraction framework that supports fully supervised, few-shot, and document-level settings, covering tasks such as named entity recognition, relation extraction, and attribute extraction [18]. To evaluate its baseline performance, we conducted tests on 50 daily text samples, which demonstrated satisfactory accuracy.

DeepKE employs an open-source Chinese relation extraction pipeline, implemented on the bert-base-chinese pre-trained language model. Considering that DeepKE lacks the capability to directly parse raw documents (such as unprocessed PDF or Word files) and performs poorly on knowledge extraction tasks without prior text cleaning and structured preprocessing, no experimental group using “raw data + DeepKE” was established in this study.

Qwen-plus-latest and DeepSeek-chat invoke their respective platform APIs, taking either raw or preprocessed sentences as input. The output format is constrained by prompt engineering to produce CSV-formatted triples.

All experiments are conducted at the sentence level as the minimal processing unit to prevent semantic misalignment across sentences.

3.3. Construction of Control Groups

The manually annotated standard dataset was independently constructed by two researchers with backgrounds in marine renewable energy O&M or marine engineering, following the procedure below:

- (1)

-

Thoroughly read all 50 documents and extract all semantically complete “entity–relation–entity” structures.

- (2)

-

Normalize entities according to a predefined O&M knowledge structure specification.

- (3)

-

Cross-verify and discuss divergent items to reach consensus.

- (4)

-

Sample-check all triples by a third expert.

The final standard dataset contains 11,530 triples, covering the core semantic patterns of typical O&M knowledge, such as:

“Photovoltaic power plant”, “defined as”, “PV plant”.

“UP77-1500 wind turbine”, “adopts”, “active pitch control”.

3.4. Evaluation Metrics

To comprehensively assess the performance of different experimental schemes in knowledge extraction from real O&M documents, this study adopts a combined “subjective evaluation + objective comparison” strategy. At the subjective level, the structure completeness and semantic quality of the generated knowledge graphs are compared through visualization. At the objective level, focus is placed on the number of extracted triples and their accuracy, evaluating each method’s information mining capability and output reliability.

3.4.1. Subjective Evaluation Metrics

To comprehensively evaluate the quality of knowledge graphs constructed under different experimental schemes, a subjective qualitative assessment was first conducted, focusing on the graphs’ interpretability, connectivity, and usability in practical engineering applications. Specifically, the triples generated from the five experimental groups were imported into the Neo4j graph database, visualized through its graphical interface, and blindly evaluated by five domain experts with backgrounds in offshore wind farm O&M, equipment management, or marine engineering.

Experts performed a comprehensive assessment of each knowledge graph based on four criteria:

Structural clarity: Evaluating whether the graph contains a large number of isolated nodes, fragmented subgraphs, or overlapping edges, in order to assess the overall readability and layout quality [19].

Core entity connectivity: Focusing on whether key engineering entities (e.g., “wind turbine”, “wind farm”, “project”) possess rich semantic connections, reflecting their central role in the knowledge network.

Semantic connectivity: Assessing whether the system can effectively associate information across multiple documents.

Engineering usability: Examining whether the graph supports typical marine renewable energy O&M query tasks, such as “Which technology is adopted by a specific unit?” or “How is a given technology applied?”.

Based on this subjective evaluation, objective quantitative metrics were introduced to precisely measure the extraction accuracy and coverage of each method, thereby establishing a complementary evaluation framework combining subjective and objective assessments.

3.4.2. Objective Evaluation Metrics

In this section, the manually curated standard triple set is used as a reference, and quantitative comparisons are conducted along the following three dimensions:

Number of Extracted Triples:

The total number of triples generated automatically by each experimental group from the 50 documents is recorded. This metric reflects how extensively each method can extract information under the same input conditions, demonstrating its content coverage capability over multi-source heterogeneous text.

Manual Sampling Evaluation:

In the quality assessment of triples, due to the absence of a complete standard answer and the high cost of full-scale manual evaluation, a manual sampling approach was adopted to assess the accuracy of the knowledge graphs. To fairly and effectively compare the extraction performance of different models, domain experts with a background in marine renewable energy engineering were invited to judge the factual correctness of entities, entity attributes, and relationships between entities in the knowledge graphs. This approach is widely recognized as reliable and feasible in current knowledge-graph evaluation practices.

To enhance comparability and control across models, the sampling strategy was further optimized. Rather than randomly sampling independently from each model’s extraction results, a set of “anchor entities” successfully extracted by all models was first identified. For each anchor entity, all triples generated by each model related to that entity were collected to construct an entity-aligned evaluation pool. Stratified random sampling by relation type was then applied, yielding a total of 500 triples as the evaluation sample [20]. This strategy ensures that all models are evaluated within the same entity context, effectively avoiding performance bias caused by differences in entity distribution, and more accurately reflects each model’s factual extraction capability under identical input conditions.

Subsequently, two domain experts independently performed double-blind annotation of the sample. Triples were labeled TRUE if they were semantically and factually correct; otherwise, they were labeled FALSE [21]. The mean proportion of triples labeled TRUE by both experts was used as the estimate of accuracy, reflecting the overall reliability of the extraction results.

Result Coverage:

To evaluate the extent to which the extraction results of each experimental group are validated by the reference set, coverage is used as an evaluation metric, defined as the proportion of the intersection between the experimental group and the reference set relative to the total size of the experimental group, as shown in Equation (1).

where $$A$$ represents the set of triples in the experimental group judged as TRUE by experts (extracted by the model and confirmed correct), and $$B$$ denotes the corresponding set of benchmark correct triples in the reference group. This metric reflects the proportion of experimentally extracted triples that can be verified against an authoritative standard. A higher value indicates stronger reliability of the model’s extracted content [22,23].

This metric effectively reflects how much of the automatically extracted content is accurate and acceptable, making it suitable for application-oriented evaluations focused on result quality.

4. Experimental Results Analysis

This chapter systematically evaluates the practical performance of different processing strategies in constructing multi-source heterogeneous O&M knowledge graphs for offshore wind farms, based on the five comparative experiments designed in Section 3. The evaluation considers both subjective quality assessments and objective quantitative metrics.

4.1. Comparison of Subjective Knowledge Graph Quality

To evaluate the usability of the knowledge graphs from a practical O&M perspective, five invited expert reviewers conducted a blind assessment of the graphs generated by Exp-1 through Exp-5. The evaluation was performed using the Neo4j visualization interface, focusing primarily on structural clarity and the connectivity of core entities, as shown in Figure 5.

In terms of structural clarity, the knowledge graphs constructed by Exp-1 are overall sparse, with numerous isolated nodes and fragmented subgraphs. Key entities, such as “wind farm” and “project”, fail to effectively aggregate related information, exhibiting a pronounced “knowledge island” phenomenon.

Although Exp-2 exhibits a significant increase in the number of nodes compared to Exp-1, and core entities can be identified, the connections between entities remain weak. The graph lacks effective semantic linkage paths, and the overall structure is still loosely distributed, failing to form a network with inherent logical coherence.

Exp-3 further expands the node scale; however, stable and coherent connections between key entities remain absent. Multiple independent subgraphs exist within the network, resulting in a loosely structured graph that lacks a unified organizational framework. This reflects the model’s tendency, in the absence of structural guidance, to accumulate local information while neglecting global topological consistency.

In contrast, the knowledge graphs of Exp-4 and Exp-5 exhibit higher structural rationality. Centered around the “wind farm” and “project” entities, they form a clear hierarchical topology, with well-defined main relationships and distinct branch layers. Key entities are effectively connected through semantically consistent relationship chains, resulting in an overall structure that is more interpretable and aligned with engineering logic.

Regarding the connectivity of core entities, only Exp-4 and Exp-5 are able to ensure that hub entities such as “wind farm” and “project” are stably linked to multiple related attributes, demonstrating strong knowledge aggregation capabilities. In contrast, the other experimental groups fail to construct a complete semantic network: Exp-1 and Exp-2 are primarily limited by omissions in information extraction, resulting in missing key associations; Exp-3, lacking prompt constraints, introduces misclassifications during relation extraction, causing semantic distortion.

Overall, subjective evaluations consistently indicate that only when high-quality input is combined with structured prompts can large-scale language models generate knowledge graphs that are complete, accurate, and practically applicable.

4.2. Comparison of Objective Results

To quantify differences in information extraction capability and output accuracy among the experimental groups, the total number of triples extracted by each method was recorded. The results are presented in Table 3.

As can be observed from the table:

Exp-1 (DeepKE), serving as the baseline traditional method, extracted only 952 triples. This indicates limited semantic understanding capability in specialized domain texts, making it difficult to identify complex engineering terminology and their associated relationships effectively, and rendering it insufficient for high-precision knowledge requirements in project O&M.

Exp-2 (No Preprocessing + Qwen-plus-latest + Zero-shot Prompt) significantly increased the number of extracted triples to 7872 following the introduction of a large-scale language model. This result demonstrates that, owing to its powerful contextual understanding and generalization capabilities, the large-scale language model offers a clear advantage over traditional methods in specialized domain knowledge extraction tasks.

Table 3. Experiment on the Quantity of Extracted Triples.

|

Experiment Group |

Document Preprocessing |

Knowledge Extraction Method |

Extraction Count |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Exp-1 |

Yes |

DeepKE |

952 |

|

Exp-2 |

No |

qwen-plus-latest (Zero-shot Prompting) |

7872 |

|

Exp-3 |

Yes |

qwen-plus-latest (Zero-shot Prompting) |

11,724 |

|

Exp-4 |

Yes |

qwen-plus-latest (Optimized Prompt Engineering) |

11,211 |

|

Exp-5 |

Yes |

deepseek-chat (Same Optimized Prompting) |

11,088 |

Exp-3 (Preprocessed + Qwen-plus-latest + Zero-shot Prompt) extracted a total of 11,724 triples, far exceeding the non-preprocessed model group (Exp-2). This further confirms the critical role of document preprocessing in enhancing information extraction quality. Specifically, operations such as OCR correction for scanned PDFs, paragraph segmentation, and format standardization effectively reduce textual noise and improve the model’s ability to perceive information, thereby significantly increasing the efficiency of entity and relation recognition.

Exp-4 (Preprocessed + Qwen-plus-latest + Few-shot Prompt) maintained a high extraction volume, yielding a total of 11,211 triples. Although slightly lower than Exp-3, it remains at a substantial level. Notably, by incorporating few-shot prompt engineering, this group guided the model output both semantically and structurally, effectively suppressing irrelevant or redundant information and enhancing the accuracy and consistency of the extracted results.

Exp-5 (Preprocessed + DeepSeek-Chat + Same Optimized Prompt) extracted 11,088 triples under the same prompt strategy, showing performance comparable to Exp-4. This indicates that, with consistent prompt engineering, different large-scale language models demonstrate strong generalization capability and transferability in knowledge extraction tasks.

In summary, the experimental results indicate that high-quality input preprocessing serves as the foundation for enhancing the knowledge extraction capability of large-scale language models. Structured prompt engineering can significantly improve the accuracy and semantic consistency of the extracted results without compromising extraction volume. Therefore, constructing efficient knowledge graphs for engineering domains requires the integrated application of preprocessing and prompt optimization techniques, thereby achieving simultaneous improvements in both quantity and quality.

To evaluate the accuracy of different models in knowledge extraction, a systematic comparison of various extraction strategies was conducted through manual sampling and coverage analysis. Considering that Exp-1 extracted a very limited number of triples and exhibited low accuracy in entity recognition and relation extraction, it was excluded from this accuracy and coverage assessment. The evaluation results for the remaining experimental groups are presented in Table 4.

Table 4. Experiment on the Quantity of Extracted Triples.

|

Experiment Group |

Document Preprocessing |

Knowledge Extraction Method |

Coverage |

Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Exp-2 |

No |

qwen-plus-latest (Zero-shot Prompting) |

59.87% |

89.2% |

|

Exp-3 |

Yes |

qwen-plus-latest (Zero-shot Prompting) |

76.39% |

89.6% |

|

Exp-4 |

Yes |

qwen-plus-latest (Optimized Prompt Engineering) |

91.47% |

94.1% |

|

Exp-5 |

Yes |

deepseek-chat (Same Optimized Prompting) |

89.10% |

93.8% |

As shown in the table, all four experimental groups maintained high triple accuracy, fully demonstrating the significant advantage of large-scale language models in knowledge extraction tasks within specialized domains.

Among the groups without few-shot prompt engineering, Exp-3 with document preprocessing achieved significantly higher coverage than the non-preprocessed Exp-2. This indicates that effective data preprocessing can substantially enhance the large-scale language model’s comprehension of low-quality engineering texts (e.g., scanned PDFs), thereby improving the consistency of the extracted knowledge with authoritative benchmarks.

A further comparison between Exp-3 and Exp-4 reveals that, under the same preprocessing conditions, the introduction of optimized structured prompt engineering (i.e., few-shot prompts) in Exp-4 increased coverage to 91.47%, significantly higher than the zero-shot Exp-3 group. This result validates the critical role of prompt engineering in guiding the model to generate factually correct and semantically coherent knowledge. It not only enhances the reliability of the extracted content but also improves the alignment with domain-standard knowledge.

Moreover, Exp-4 and Exp-5 demonstrated highly similar performance in terms of accuracy and coverage, indicating that under a consistent preprocessing workflow and prompt framework, different large-scale language models can reliably produce high-quality knowledge. This highlights the method’s strong cross-model adaptability and engineering robustness.

In summary, the experimental results fully demonstrate that constructing knowledge graphs in specialized domains requires an integrated approach that leverages high quality document preprocessing, structured prompt engineering, and advanced large-scale language models. This combination ensures large-scale extraction while simultaneously achieving high accuracy, extensive coverage, and strong domain adaptability. This technical paradigm provides a practical pathway for automated knowledge management in technology-intensive industries such as marine renewable energy.

5. Discussion

5.1. Interpreting Extraction Quality for Decision Support

The experimental results presented in Section 4 demonstrate that the proposed workflow (Exp-4) achieves superior coverage and accuracy compared to baseline methods. From a knowledge-engineering perspective, these quantitative improvements directly translate into critical capabilities for intelligent O&M:

The quantitative improvements in extraction quality directly translate into critical capabilities for intelligent O&M. From a structural perspective, the high connectivity achieved by our method (as illustrated in Figure 5) effectively eliminates the “island phenomenon”, creating a coherent semantic network that ensures reasoning reliability and fault traceability. Simultaneously, in the high-stakes environment of offshore maintenance, the high accuracy achieved in Exp-4 minimizes the risk of model hallucinations. This precision serves as a cornerstone of decision confidence, allowing engineers to rely on the system for retrieving critical technical parameters without the burden of excessive manual verification.

Experimentally, the proposed method (Exp-4) demonstrates a favorable balance, achieving the highest performance in both accuracy and coverage among the tested settings, which suggests that the current configuration provides a solid foundation for general O&M applications. However, acknowledging that diverse real-world scenarios may require distinct prioritizations, the Exp-4 configuration serves as a flexible baseline subject to subsequent optimization. Specifically, for Operational Tasks prioritizing safety, the current rigorous settings are recommended to ensure high decision confidence; conversely, for Strategic Tasks where maximizing information recall is the primary objective, the prompt constraints based on Exp-4 can be further adjusted or relaxed to capture marginal data points that might be excluded by stricter defaults, thus tailoring the framework to specific analytical requirements.

5.2. Practical Implications and Deployment Prerequisites

The proposed knowledge graph translates technical triples into actionable insights for distinct stakeholders.

For O&M engineers, the primary value lies in operational efficiency, specifically in reducing the Mean Time to Repair (MTTR). Instead of manually searching through hundreds of PDF pages for technical specifications, engineers can query the graph to instantly retrieve specific parameters. This capability transforms troubleshooting from a document-retrieval task into a precise knowledge-querying process. For asset managers, the system aggregates fragmented data into a unified view, effectively eliminating the “information silos” that often hinder collaboration. By providing a shared knowledge base, it facilitates smoother communication between departments like maintenance and procurement, ensuring that strategic decisions are based on a comprehensive understanding of asset health rather than isolated reports.

However, effective deployment requires specific organizational focuses. First, regarding Data Lifecycle Management, organizations must transition from archiving “dead data” (static files) to maintaining “live assets” (digitized knowledge) to ensure the graph remains current. Second, Source Data Quality is paramount. While the method effectively bridges information gaps, maximizing its value requires stronger connections between data-generating departments. Ensuring high-quality, standardized data input from diverse sources is the fundamental prerequisite for constructing and evolving a superior knowledge graph.

5.3. Deployment Challenges and Technical Constraints

Beyond organizational readiness, several technical constraints must be addressed for real-world adoption. The first challenge is computational cost. While LLM-based extraction is resource-intensive, our framework integrates the high-cost construction phase with the low-latency querying phase. Crucially, to mitigate recurring maintenance costs, we adopt an incremental extraction strategy that processes only newly added data rather than re-extracting the entire dataset, thereby significantly optimizing resource expenditure. The second issue is model dependence. Although this study utilized proprietary model APIs for feasibility testing, handling confidential engineering documents requires strict privacy controls. Future deployments should prioritize the fine-tuning and local deployment of open-source models to prevent data leakage and avoid vendor lock-in. Finally, regarding integration with existing infrastructure, the knowledge graph is designed not as an isolated unit but as an interoperable module. It is intended to interface seamlessly with enterprise systems via standardized APIs, thereby supporting automated workflows.

5.4. Synergies with Broader Knowledge Management Ecosystems

While this study focuses on the operational phase, the proposed extraction framework aligns with broader strategic initiatives in marine energy knowledge management. Recent scholarship has demonstrated the value of structured knowledge for mapping innovation trends in wave and tidal energy patent landscapes [24]. There is a clear synergy between these approaches: while patent analysis reveals the trajectory of technological innovation (R&D perspective), our O&M knowledge graph captures the ground truth of asset performance and failure modes (operational perspective). Integrating these two dimensions could foster a “Design for Maintainability” feedback loop, where empirical failure data extracted from O&M manuals and logs directly informs the strategic direction of future technological innovations, ensuring that new patent developments are grounded in real-world operational challenges.

6. Conclusions and Outlooks

This study addresses the practical challenges in marine renewable energy O&M, including dispersed knowledge, semantic heterogeneity, and complex structures, by proposing a multi-source heterogeneous knowledge graph construction method assisted by large-scale language models. By integrating typical documents such as industry standards, maintenance procedures, equipment manuals, project-related materials, corrosion inspection records, and meteorological and ocean condition briefs, and combining document preprocessing, LLM-based extraction, and entity normalization strategies, the method achieves automatic transformation from unstructured text to structured triples and constructs a dynamically evolving intelligent O&M knowledge graph for marine renewable energy.

Experimental results demonstrate that, compared with traditional methods, the proposed approach significantly improves the quantity of triple extraction, recognition accuracy, and matching rate. In particular, it exhibits stronger semantic understanding and generalization when handling scanned documents, specialized terminology, and complex causal sentences. Exp-4, which incorporates preprocessing and optimized prompt engineering, achieves the highest matching rate, validating the critical role of a systematic workflow in enhancing knowledge quality. Notably, the integration of semantic entity normalization directly into the prompt engineering workflow represents a distinct efficiency gain. By guiding the LLM to standardize terminology during the extraction phase, this approach effectively eliminates the need for complex, standalone post-processing pipelines, thereby streamlining the engineering implementation.

However, certain limitations regarding the external validity of this study should be acknowledged. The empirical evaluation presented here relies on O&M datasets sourced from specific offshore wind and photovoltaic assets. While the results provide compelling evidence for the feasibility of the proposed LLM-assisted workflow, its robustness across broader contexts remains to be verified, particularly in facilities with varying documentation standards, different terminological conventions, or diverse data granularities. Consequently, the findings should be interpreted as a validation of the design methodology rather than a guarantee of generalizable performance across all marine renewable energy scenarios without local adaptation. Furthermore, a critical challenge inherent to generative AI is the risk of “hallucinations”—the generation of plausible but factually incorrect relations. While our prompt engineering minimizes this risk, the probabilistic nature of LLMs implies that absolute accuracy cannot be guaranteed. Therefore, in safety-critical O&M scenarios, the extracted knowledge graph should function as a decision-support aid subject to expert verification (human-in-the-loop), rather than as a fully autonomous authority. Finally, it is important to note that while the system processes scanned documents, the current graph construction relies exclusively on textual content extracted via OCR. Visual features contained within these files, such as schematic diagrams, technical drawings, or photographic evidence of defects, are not currently parsed or semantically integrated. Incorporating visual understanding remains a specific objective for our future multimodal research.

Future research can be further advanced in several high-demand directions. First, enhancing the processing of non-textual information, such as tables and images, is necessary to achieve multimodal knowledge extraction. Second, developing domain-specific models will improve the understanding of terminology and logical structures in offshore wind O&M. Third, beyond static data, future iterations should integrate the knowledge graph with stochastic optimization models to account for “endogenous uncertainty”, enabling maintenance decisions guided by the graph to actively inform network planning and risk management [25]. Finally, as the construction of large-scale knowledge graphs relies on energy-intensive computing resources, the carbon footprint of the digital infrastructure itself must be considered. Frameworks regarding computing power migration and renewable integration could be adapted to optimize the deployment of these AI-driven O&M systems, ensuring that the digital twins are as low-carbon as the wind farms they monitor [26]. The ultimate goal is to establish a professional, dynamically evolving, and ecologically responsible knowledge infrastructure for marine renewable energy.

Statement of the Use of Generative AI and AI-Assisted Technologies in the Writing Process

During the preparation of this manuscript, the author utilized AI large-scale models to assist with translation. All content generated by these tools has been thoroughly reviewed, revised, and verified by the author, who assumes full responsibility for the accuracy and completeness of the published material.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the financial support of Nanning city science and Technology Bureau.

Author Contributions

Methodology, M.L.; Software, Z.J.; Validation, Y.Y. and X.M.; Investigation, Z.J. and T.L.; Writing Original Draft Preparation, Z.J.; Review & Editing, J.Z. and Y.W.; Supervision, J.Z. and Q.M.

Ethics Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

Funding

This research was funded by the Key R&D Program of the Nanning Science Research and Technology Development Plan grant number (20253057).

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

-

Lian J, Cui L, Fu Q. Offshore Renewable Energy Advance. Mar. Energy Res. 2024, 1, 10006. DOI:10.70322/mer.2024.10006 [Google Scholar]

-

Gao X, Dong X, Ma Q, Liu M, Li Y, Lian J. Marine Photovoltaic Module Salt Detection via Semantic-Driven Feature Optimization in Mask R-CNN. Mar. Energy Res. 2025, 2, 10015. DOI:10.70322/mer.2025.10015 [Google Scholar]

-

He Z, Yang J, Tang G, Yang Y, Du Z, Zhang S. Key technologies and development trends of VSC-HVDC transmission for offshore wind power. Renew. Energy Syst. Equip. 2025, 1, 35–49. DOI:10.1016/j.rese.2024.09.001 [Google Scholar]

-

Gao X, Wang T, Liu M, Lian J, Yao Y, Yu L, et al. A framework to identify guano on photovoltaic modules in offshore floating photovoltaic power plants. Sol. Energy 2024, 274, 112598. DOI:10.1016/j.solener.2024.112598 [Google Scholar]

-

Ali AAIM, Imran MMH, Jamaludin S, Ayob AFM, Suhrab MIR, Norzeli SM, et al. A review of predictive maintenance approaches for corrosion detection and maintenance of marine structures. J. Sustain. Sci. Manag. 2024, 19, 182–202. DOI:10.46754/jssm.2024.04.014 [Google Scholar]

-

Fox H, Pillai AC, Friedrich D, Collu M, Dawood T, Johanning L. A review of predictive and prescriptive offshore wind farm operation and maintenance. Energies 2022, 15, 504. DOI:10.3390/en15020504 [Google Scholar]

-

Yang Y, Wang S, Tan J, Chen L. The Intelligent Operation and Maintenance Management System for Offshore Wind Farms. South. Energy Constr. 2025, 8, 74–79. DOI:10.16516/j.gedi.issn2095-8676.2021.01.011. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

-

Lou P, Yu D, Jiang X, Hu J, Zeng Y, Fan C. Knowledge graph construction based on a joint model for equipment maintenance. Mathematics 2023, 11, 3748. DOI:10.3390/math11173748 [Google Scholar]

-

Bouwer UI. Maintenance strategies for deep-sea offshore wind turbines. J. Qual. Maint. Eng. 2010, 16, 367–381. DOI:10.1108/13552511011084526 [Google Scholar]

-

Pi Q, Lu J, Zhu T, Peng Y. A large language model-enhanced zero-shot knowledge extraction method. Comput. Sci. 2025, 52, 22–29. DOI:10.1186/jsjkx.241000049. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

-

Yang Y, Chen S, Zhu Y, Liu X, Ma W, Feng L. Intelligent extraction of reservoir dispatching information integrating large language model and structured prompts. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 14140. DOI:10.1038/s41598-024-64954-0 [Google Scholar]

-

Tang H, Liu Z, Chen D, Chu Q. ChatSOS: A large language model-based question-answering system for safety engineering knowledge. China Saf. Sci. J. 2024, 34, 178–185. DOI:10.16265/j.cnki.issn1003-3033.2024.08.1901. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

-

Sarhan AM, Ali HA, Wagdi M, Ali B, Adel A, Osama R, et al. CV content recognition using YOLOv8 and Tesseract-OCR deep learning. Comput. J. 2025, bxaf124. DOI:10.1093/comjnl/bxaf124 [Google Scholar]

-

Yang M, Yoo S, Jeong O. DeNERT-KG: Named entity and relation extraction model using DQN, knowledge graph, and BERT. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 6429. DOI:10.3390/app10186429 [Google Scholar]

-

Xu D, Chen W, Peng W, Zhang C, Xu T, Zhao X, et al. Large language models for generative information extraction: A survey. Front. Comput. Sci. 2024, 18, 186357. DOI:10.1007/s11704-024-40555-y [Google Scholar]

-

Xing J, Nie X, Li Q, Fan X. Construction of distributed photovoltaic operation and maintenance knowledge base based on time series knowledge map. Discov. Appl. Sci. 2025, 7, 409. DOI:10.1007/s42452-025-06858-w [Google Scholar]

-

Zhang H, Zhang H, Yan W, Zhu S, Jiang Z. Precise extraction of remanufacturing process knowledge using chain-of-thought prompting with large language models. Manuf. Technol. Mach. Tool 2025 10, 90–98. DOI:10.19287/j.mtmt.1005-2402.2025.10.007. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

-

Zhang N, Xu X, Tao L, Yu H, Ye H, Qiao S, et al. DeepKE: A deep learning based knowledge extraction toolkit for knowledge base population. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2201.03335. DOI:10.48550/arXiv.2201.03335 [Google Scholar]

-

Wei Z, Xiao Y, Tong Y, Xu W, Wang Y. Linear building pattern recognition via spatial knowledge graph. Acta Geod. Et Cartogr. Sin. 2023, 52, 1355–1363. DOI:10.11947/j.AGCS.2023.20220121. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

-

Di Paolo G, Rincon-Yanez D, Senatore S. A quick prototype for assessing OpenIE knowledge graph-based question-answering systems. Information 2023, 14, 186. DOI:10.3390/info14030186 [Google Scholar]

-

Lang TA, Stroup DF. Who knew? The misleading specificity of “double-blind” and what to do about it. Trials 2020, 21, 697. DOI:10.1186/s13063-020-04607-5 [Google Scholar]

-

Mishra BD, Tandon N, Clark P. Domain-targeted, high precision knowledge extraction. Trans. Assoc. Comput. Linguist. 2017, 5, 233–246. DOI:10.1162/tacl_a_00058 [Google Scholar]

-

Sabbatini F, Calegari R. On the evaluation of the symbolic knowledge extracted from black boxes. AI Ethics 2024, 4, 65–74. DOI:10.1007/s43681-023-00406-1 [Google Scholar]

-

Pazhouhan M, Karimi Mazraeshahi A, Jahanbakht M, Rezanejad K, Rohban MH. Wave and tidal energy: A patent landscape study. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 1967. DOI:10.3390/jmse12111967 [Google Scholar]

-

Giannelos S, Konstantelos I, Zhang X, Strabc G. A stochastic optimization model for network expansion planning under exogenous and endogenous uncertainty. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2025, 248, 111894. DOI:10.1016/j.epsr.2025.111894 [Google Scholar]

-

Du Z, Yin H, Zhang X, Hu H, Liu T, Hou M, et al. Decarbonisation of Data Centre Networks through Computing Power Migration. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE 5th International Conference on Computer Communication and Artificial Intelligence (CCAI), Haikou, China, 23–25 May 2025; pp. 871–876. DOI:10.1109/CCAI65422.2025.11189418 [Google Scholar]