A Large-Scale Language Model Based System for Automated Generation of Offshore Wind Power Feasibility Study Reports

Received: 10 December 2025 Revised: 19 December 2025 Accepted: 04 January 2026 Published: 08 January 2026

© 2026 The authors. This is an open access article under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

1. Introduction

Driven by global energy transition goals, the accelerated scaling of offshore wind power development imposes stringent requirements on the professionalism [1,2,3], standardization, and timeliness of feasibility studies:

(1) Professional expertise must precisely integrate multi-disciplinary technical parameters, policy standards, and engineering experience to meet cross-disciplinary validation needs [4]. (2) Standardization necessitates unified chapter frameworks, data definitions, and terminology systems to accommodate diverse applications such as approvals and credit assessments [5]. (3) Timeliness demands responsiveness to dynamic shifts in policy, market conditions, and technology, enabling rapid compilation and flexible updates [6].

Traditional manual compilation struggles to meet these concurrent demands, with core bottlenecks concentrated in two areas:

First, regarding professionalism, offshore wind projects involve highly complex, multi-disciplinary knowledge spanning meteorology, marine engineering, electrical systems, and economic evaluation. However, in practice, it is difficult for a single manual compiler to possess “comprehensive professional capabilities” across all these domains. Consequently, reliance on individual expertise inevitably leads to friction points—such as the disconnect between engineering parameter updates and financial valuation models—resulting in potential issues like policy standard confusion and gaps in interdisciplinary knowledge integration, which significantly undermines report credibility [7]. Second, insufficient timeliness: manual collaborative compilation cycles are lengthy. When data updates or plan adjustments occur, extensive time is required for cross-chapter modifications, and issue tracing lacks clear pathways, making it difficult to support rapid decision-making needs [8]. These pain points fundamentally stem from the lack of structured knowledge accumulation, standardized compilation processes, and automated modeling capabilities. There is an urgent need to leverage technological means to achieve efficient knowledge reuse, automated process operation, and collaborative data flow.

Automated document generation technology has evolved through multiple stages: Early template-filling mechanisms only enabled static content assembly, lacking semantic understanding and dynamic logic control, and failing to meet the interdisciplinary requirements of offshore wind reports [9,10]. Subsequent rule-based engine approaches improved generative logic control but suffered from poor scalability and high maintenance costs, struggling to keep pace with rapid policy and technological iterations in the offshore wind sector [11]. In recent years, large language model-driven professional text generation has made progress in fields like law and medicine [12]. However, in offshore wind feasibility study scenarios, quality issues such as parameter confusion, data inconsistencies, and loose logic persist, failing to meet requirements for multi-module collaboration and compliance verification [13,14].

To address the procedural management challenges of AI applications, workflow frameworks like LangChain and Llama Index [15], alongside low-code platforms such as Dify and Coze [16], have emerged. These enable visual workflow orchestration through declarative languages like YAML. The selection of a YAML-based workflow is specifically driven by its interpretability and accessibility for non-technical domain experts, allowing engineers to visually orchestrate complex generation logic and templates without requiring deep coding expertise [17]. Concurrently, existing research has established generic frameworks leveraging the structural characteristics of feasibility reports, providing domain knowledge support [18]. However, significant gaps remain in the automated generation of offshore wind power feasibility reports: existing systems predominantly focus on isolated stages, lacking end-to-end modeling from data input to report output. They struggle to integrate multi-source heterogeneous data and enable cross-chapter logical coordination, and crucially, fail to establish comprehensive quality control mechanisms across the entire workflow. The generation process remains a “black box”, lacking interpretability and human intervention interfaces, making quality issue tracing difficult. No universal paradigm has emerged that balances controllability, professionalism, quality reliability, and reusability. This prevents systematic validation to avoid quality defects such as parameter confusion, data inconsistencies, and information gaps, and hinders adaptation to quality standards under personalized requirements.

To address these challenges, this paper constructs a configurable, explainable report generation system tailored for feasibility studies in the offshore wind power industry, enabling end-to-end document generation through structured data-driven approaches. This system specifically addresses the core challenge of “controllability”—defined in the context of Feasibility Study Reports (FSR) as the critical balance between algorithmic efficiency and the capability for human intervention, ensuring that the generation process is not a deterministic “black box” but a verifiable workflow. Key contributions include:

- (1)

-

Proposing a YAML-based workflow-driven architecture supporting visual orchestration of complex analytical modules.

- (2)

-

Designing a multi-level prompt framework to achieve precise data-to-text mapping.

- (3)

-

Validating system effectiveness, generation efficiency, and content accuracy through real-world project implementation.

- (4)

-

Exploring a new paradigm of intelligent document generation via “low-code platforms + large models”, providing a technical pathway for automating feasibility study validation in offshore wind projects.

2. System Design

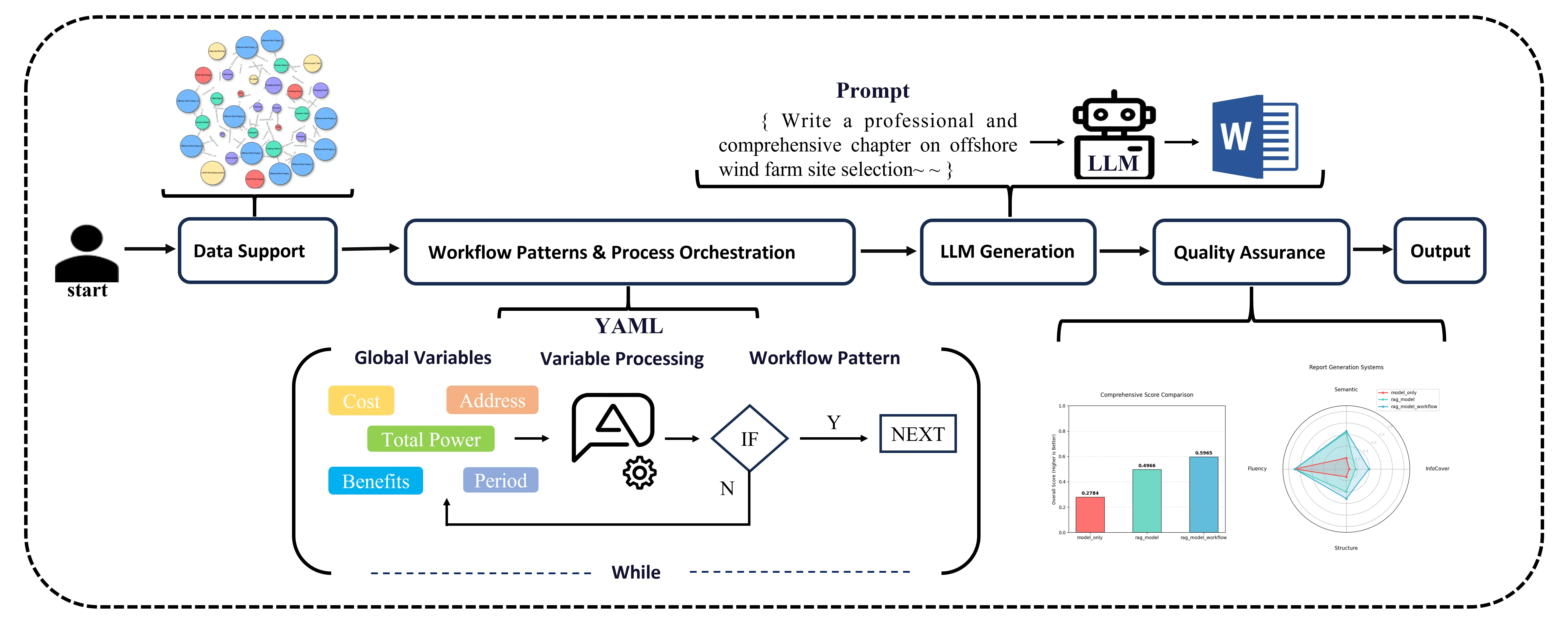

To address the requirements for professionalism, standardization, and timeliness in preparing feasibility studies for offshore wind power projects, this chapter establishes a systematic design framework centered on “Data Support—Process Driven—Quality Assurance”. The focus is on designing the core workflow modules, with the system design structure detailed in Figure 1.

Within the data preprocessing and knowledge graph construction module, multidimensional data cleansing and validation rules are established to provide high-quality structured data support for the knowledge graph, enabling the transformation and association of data into domain knowledge [19]. The declarative workflow engine serves as the system’s central hub, employing a three-tier architecture to construct the overall framework [20]. Based on YAML, it builds a visual workflow engine featuring three layered workflow modes: serial generation, conditional branching, and loop aggregation [21]. Combined with modular prompt engineering and robust variable management mechanisms, it supports full-process automation from data input to report output. Through the above design, the system ensures both accuracy in data processing and completeness in knowledge association, while also possessing flexibility in process orchestration and efficiency in report generation. This lays the technical foundation for subsequent scenario applications and evaluations.

2.1. Data Preprocessing and Knowledge Graph Construction

This phase implements the “data support” step, with the core objective of transforming multi-source, heterogeneous policy and project data into high-quality, structured domain knowledge. This provides a solid factual foundation for subsequent LLM-generated report texts [22].

Structured Modeling and Knowledge Extraction

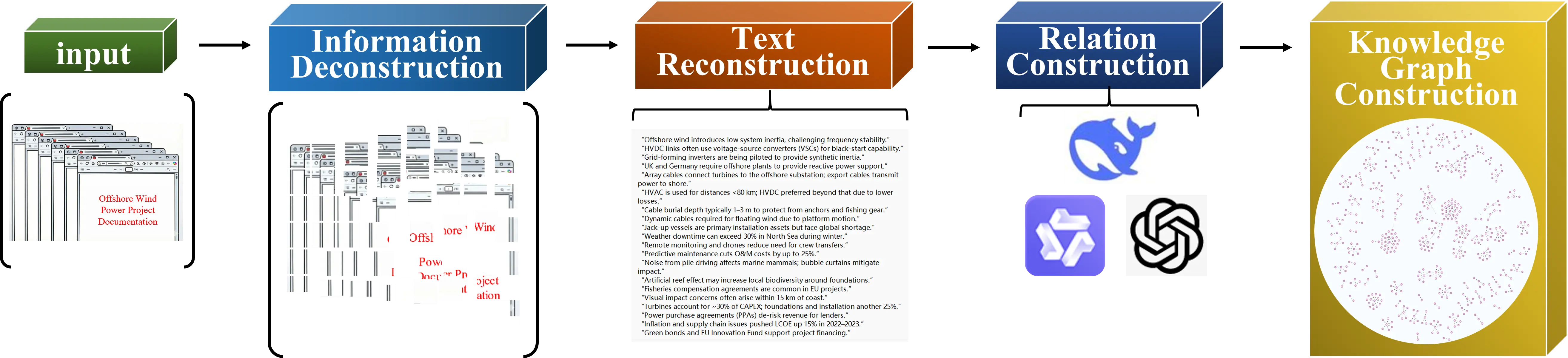

The system’s data sources primarily consist of policy documents, specialized development reports, and project application materials published on official government websites at all levels, ensuring authority, standardization, and timeliness. We first perform report structure analysis on these raw data, defining the hierarchical logic and core content modules of the reports as “concept nodes” and “entity-attribute” mapping carriers within the knowledge graph. Through multidimensional data cleansing, logical validation (e.g., logical constraints, unit standardization), and data-to-text mapping mechanisms (defining semantic expression rules for converting numerical values into natural language), we ultimately construct a domain knowledge graph, achieving the transformation of data into inferable domain knowledge (see Figure 2 for the knowledge extraction process). This process ensures LLMs can accurately and professionally reference factual data during report generation. Serving as the foundation for Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG), it significantly enhances the factual accuracy of generated content.

Specifically, regarding the implementation configuration, the system constructs domain knowledge graphs using an “entity-relation-entity” triple schema, with the knowledge base scale dynamically adjusted based on project size. To balance retrieval precision and contextual coherence, we employ a Parent-Child chunking strategy, smaller child chunks are utilized for precise vector matching, while larger parent chunks provide broader context for the LLM. High-dimensional vector representations are generated by the Qwen-text-embedding-v4 model. For retrieval, we employ a hybrid mechanism weighted at 0.6 (semantic similarity) and 0.4 (keyword matching). The system filters results using a relevance score threshold of 0.2 and retrieves the Top-10 candidate segments for evidence injection.

2.2. Workflow Design

At this stage, the system executes the “process-driven” step within the “data-driven—process-driven—quality-driven” framework. Report generation tasks typically involve complex collaboration across multiple stages, conditions, and roles. This necessitates an automated scheduling and intelligent decision-making system powered by a structured, configurable, and traceable workflow engine. Therefore, our core objective is to build a YAML-based visual workflow engine. This engine models the report generation process as a directed flowchart composed of “nodes-edges-variables-conditions”, utilizing a layered pattern to adapt to both standardized and customized scenarios. To enhance the professionalism and consistency of generated content, the system integrates a modular prompt engineering system with context-aware mechanisms. It dynamically injects domain-specific variables and few-shot examples to guide large language models in producing section content compliant with industry standards. Simultaneously, global variable management and intermediate state caching enable cross-node data sharing and fault recovery capabilities. This ensures stable, efficient, and traceable workflow execution under complex conditions, ultimately driving end-to-end automation from raw data to complete reports.

2.2.1. Overall Architecture of the Workflow System

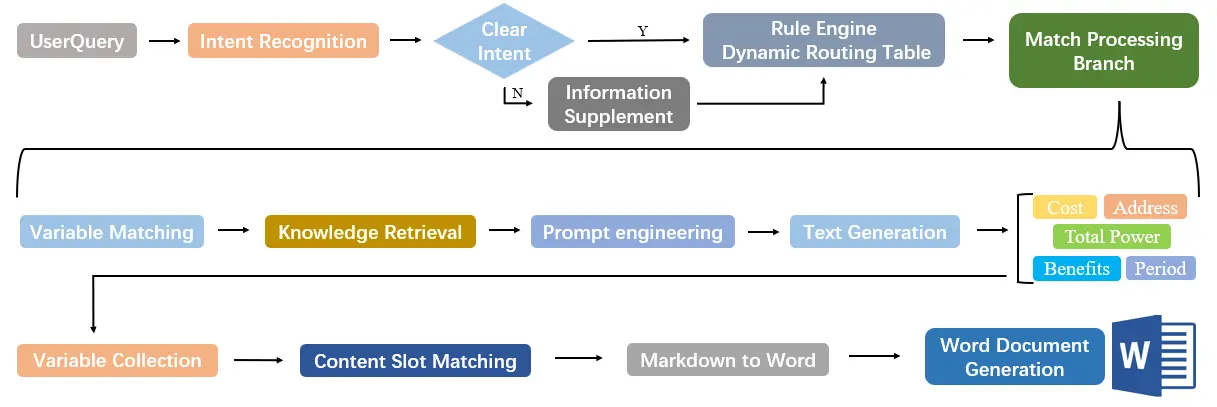

The system adopts a three-tier architecture with layered decoupling. Each tier supports end-to-end automated processing from data input to report output through clearly defined responsibilities and collaborative mechanisms. The system flowchart is shown in Figure 3 below.

The Input Layer builds upon existing data collection, integration, and interaction capabilities by enhancing intent recognition and guided input functions. The language understanding module parses user input text, leveraging domain-specific dictionaries to extract core intent elements such as report section requirements, information supplementation needs, and formatting adjustments. These elements are precisely categorized to provide decision-making basis for subsequent workflow matching. Based on intent recognition results, the system automatically matches corresponding processing branches through a rule engine and dynamic routing table. For ambiguous or incomplete instructions, the system maintains contextual awareness through session state management and generates structured prompting scripts. This ensures supplementary information is accurately linked to the workflow node corresponding to the original instruction. Ultimately, the input layer evolves from a passive data receiver into an intelligent interaction hub, achieving precise alignment between user needs and system processing capabilities. This provides scenario-based, process-oriented input support for report compilation.

As the core logical unit of the system, the processing layer adopts a microservices architecture to integrate the YAML workflow engine, AI capability invocation module, branch-embedded prompt engineering, and global variable keyword retrieval mechanism. The YAML workflow engine defines files for visual task orchestration and automated execution. The AI capability invocation module interfaces with large language model services via APIs to encapsulate and invoke atomic capabilities like text generation and semantic analysis. Building upon this, the branch-embedded prompt engineering provides precise prompt optimization solutions for each business process node, while the global variable mechanism supports keyword retrieval across different sections. Together, they enhance knowledge base association and support for paragraph content. Modules collaborate through event-driven mechanisms to sequentially execute critical workflows: rule-engine-based anomaly handling, vector database-enhanced retrieval, and collaborative generation combining template engines with LLMs.

The output layer centers on “diversified report delivery”, establishing an integrated system that consolidates execution results and adapts formats. This layer first aggregates outcomes from all business branches and standardizes them into the global variable storage space. It then systematically integrates content based on the structured data within these global variables, following a predefined chapter logic framework to generate standardized Markdown documents. This ensures logical coherence and content completeness in the output text. Subsequently, specialized format conversion modules enable precise mapping and efficient export from Markdown to Word office formats.

2.2.2. YAML-Based Workflow Engine

The processing layer, serving as the central hub for core system logic, relies on a YAML-based workflow engine to enable automated execution through visual workflow orchestration and end-to-end scheduling. This engine is deployed and configured via the Dify platform. The Dify platform offers a low-code drag-and-drop interface, enabling users to rapidly complete visual workflow design, parameter configuration, and online debugging without requiring deep coding expertise. This significantly lowers the technical barriers and operational costs associated with process orchestration.

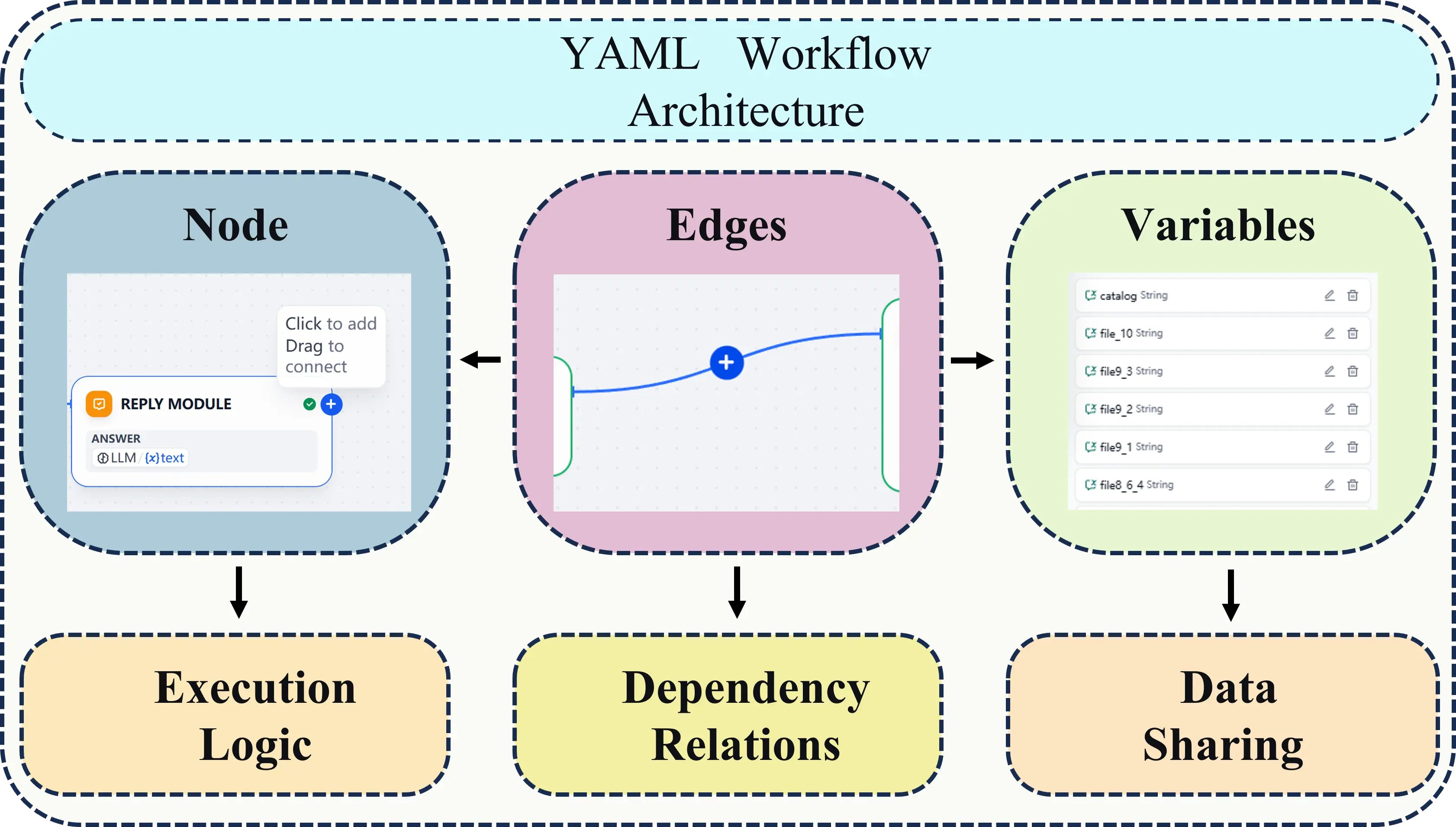

The core structure of YAML workflows comprises four key elements that collectively support the structured definition and flexible execution of processes. The static functional diagram is shown in Figure 4:

Conditional Expression: Serving as the core trigger for branching workflows, it evaluates variable values or node execution results to return Boolean values (True or False), enabling dynamic decision-making for workflow direction.

The engine incorporates two key node types to accommodate core business requirements: First, the Conditional Judgment Node branches the process into “condition met” and “condition not met” paths based on predefined conditional expressions. For example, it determines whether to trigger the “Large Project Specialized Analysis” branch based on the “Project Scale” variable. Second, AI Generation Nodes encapsulate large language model invocation logic. By receiving prompt templates and input variables, they output AI-generated text tailored to specific scenarios (e.g., market analysis sections, financial evaluation conclusions), while supporting custom configuration of model parameters like temperature and max_tokens.

2.2.3. Layered Workflow Model

To fully unleash the flexible orchestration capabilities of the YAML workflow engine and accommodate diverse report generation requirements across different scenarios, the system employs three layered workflow modes to achieve precise alignment between scenarios and processes: Serial Generation Mode: Adopts an execution logic of “sequential chapter progression”, wherein each chapter generation node is rigorously activated in strict compliance with the standardized report structure, including Project Overview, Market Analysis, Financial Evaluation, Risk Analysis, and Conclusions and Recommendations. This mode suits conventional report generation scenarios with fixed structures and no special branching requirements. Linear execution ensures logical continuity and content integrity between chapters. Conditional Branching Mode: Enables differentiated branching based on “content feature variables”. Taking offshore wind power as an example, core variables like “project scale”, “development stage”, or “technical approach” dynamically match corresponding analysis modules, data dimensions, and chapter structures. This achieves refined, personalized content generation for specific scenarios, significantly enhancing report professionalism and relevance. Cyclic Aggregation Mode: For comprehensive reports encompassing multiple subprojects, this closed-loop process employs “subproject cyclic generation—result aggregation and summarization”. First, the loop node traverses all subproject data to generate dedicated analysis chapters for each subproject. Subsequently, the aggregation node integrates multiple chapters according to predefined rules (e.g., sorting by subproject ID, merging similar analysis conclusions) to form a unified comprehensive report, effectively avoiding redundant operations and data duplication.

2.2.4. Variable Management and State Transfer

Whether it’s the fundamental scheduling of workflow engines or the differentiated execution of layered workflow models, both rely on consistent data flow across nodes and tiers. To this end, the system incorporates a robust variable management and state transfer mechanism, ensuring workflow execution stability and traceability through three dimensions: data storage, sharing, and fault tolerance: Context Object Design: Defines a global Context object as the unified variable storage container, categorizing variables by data attributes into three types: “Input Variables” (e.g., user-uploaded project foundation data), “Intermediate Variables” (e.g., post-cleaning investment amounts, AI-generated chapter text), and “Configuration Variables” (e.g., workflow ID, template version number). Each variable records creation time, modification history, and associated node information to support issue identification and process tracing. Cross-Node Variable Sharing Mechanism: Employs a dual-layer storage structure of “global variable pool + node-local variables”. Data in the global pool is accessible and modifiable by all nodes, while local variables remain valid only within their current node. Cross-node data access is enabled through “variable ID mapping”. For example, the “AI Generation Node” can directly reference “Standardized Financial Data” stored in the global variable pool by the “Data Cleansing Node”, ensuring efficient data flow. Intermediate Result Caching Strategy: For critical intermediate outputs during workflow execution (e.g., AI-generated chapter texts, data validation reports), a combined storage approach of local caching and scheduled backups is employed. Should the workflow abnormally terminate due to network failures or model invocation errors, restarting allows direct retrieval of completed intermediate results from cache without re-executing the entire process. This significantly enhances system fault tolerance and execution efficiency.

2.2.5. Modular Prompt Engineering

Building upon the foundational capabilities of the YAML workflow engine’s scheduling and variable-passing mechanisms, the system has established a systematic modular prompt engineering framework to further enhance the professionalism, accuracy, and logical consistency of AI-generated content. This framework comprises three core components: a modular prompt template library, refined optimization strategies, and scientific parameter configuration. The Modular Prompt Template Library, categorized by report chapter types and functional scenarios, consists of three core template series: project background generation prompts, which include sub-templates such as “Industry Trend Analysis”, “Regional Development Needs Statement”, and “National Strategy Alignment Explanation” and dynamically generate background narratives highlighting the project’s strategic value by injecting variables like “Project Domain”, “Location Region”, “Policy Support Documents”, and “Energy Transition Goals”, market analysis generation prompts, which cover sub-templates such as “Industry Development Trend Analysis”, “Target Customer Positioning”, and “Competitive Landscape Assessment” and require variables including “Project Industry Attributes” and “Regional Market Data” for targeted generation; and risk analysis generation prompts, which encompass sub-templates like “Risk Identification & Assessment”, “Risk Management Solutions”, and “Technical Risk Mitigation” and require customization based on parameters such as “Project Domain” and “Risk Factor Weighting”. Complementing this template library, the Prompt Optimization Strategy employs two core methods to enhance generation quality: Context-aware Prompting, which dynamically embeds workflow variables into prompts to ensure AI-generated content maintains logical consistency with existing information while avoiding conflicts and redundancy, and Example-driven Prompting, which incorporates 1–3 high-quality domain-specific examples into the prompt to guide the AI in learning professional expression patterns and industry terminology, thereby enhancing content expertise. The Model Parameter Configuration further balances diversity and accuracy through key settings: a temperature value of 0.2 enables low randomness control to prevent overly rigid or off-topic content, and a max_tokens limit of 512 restricts single-segment text length to avoid redundancy, precisely matching the length requirements of individual chapters or paragraphs.

3. Scenario Application and Evaluation

At this stage, the system implements the “Quality Assurance” step within the “Data-Driven—Process-Driven—Quality Assurance” framework. This chapter focuses on the algorithmic principles underlying the four core indicators of the evaluation system. By integrating literature support and mathematical derivations, it clarifies the technical selection logic and domain-specific optimization strategies, providing theoretical underpinnings for the scientific rigor and reliability of evaluation outcomes.

3.1. Semantic Consistency Evaluation: RCMD Algorithm Principles and Implementation

The semantic consistency metric employs the Relaxed Contextualized Token Mover’s Distance (RCMD) algorithm [23]. This algorithm’s core advantage lies in addressing the issues of “ignoring contextual dependencies” and “token-level matching bias” inherent in traditional n-gram based metrics like BLEU [24] or ROUGE [25]. While these traditional metrics focus on surface-level lexical overlap, RCMD utilizes contextualized embeddings to measure semantic distance. This makes it particularly suitable for fact consistency detection in specialized domain texts, where preserving the meaning of technical parameters is more critical than matching exact phrasing.

3.1.1. Core Logic of the Algorithm

The RCMD algorithm achieves optimal matching of textual semantic distributions through a three-step process: “semantic embedding”, “distance matrix construction”, and “marginal distance calculation”.

(1) Token-level semantic embedding generation: Utilizes a pre-trained BERT model to perform token-level encoding on baseline text Sb and generated text Sg, outputting a contextual semantic vector $${h}_{i}\in {\mathbb{R}}^{768}$$ for each token (where i denotes the token index). This process leverages self-attention mechanisms to capture token dependencies, ensuring contextual relevance of semantic vectors.

(2) Cosine Distance Cost Matrix Construction: Calculate the cosine distance between all token semantic vectors of Sb and Sg to construct the cost matrix. $$M\in {\mathbb{R}}^{{L}_{b}×{L}_{g}}$$, where Lb and Lg represent the token lengths of the two texts respectively. Matrix element Mij is defined by Equation (1).

|

```latex{M}_{ij}=1-\frac{{h}_{b,i}\cdot {h}_{g,j}}{‖{h}_{b,i}‖\cdot ‖{h}_{g,j}‖}``` |

(1) |

The cosine distance formula is: $${M}_{ij}\in \left[0,\mathrm{ }2\right]$$. A smaller value indicates higher semantic similarity between two tokens.

Marginal Distance Weighted Summation: Introduce token distribution vectors $${d}_{1}\in {\mathbb{R}}^{{L}_{b}}$$ and $${d}_{2}\in {\mathbb{R}}^{{L}_{g}}$$ obtained by normalizing token frequency with TF-IDF weights. Calculate the optimal matching marginal distance between texts. The final semantic consistency scoring algorithm formula is given by Equation (2).

|

```latexSim\left(S_b, S_g\right) = 1 - \frac{1}{2}\left( \sum_{i=1}^{L_b} d_1\left(i\right) \cdot \min_j M_{ij} + \sum_{j=1}^{L_g} d_2\left(j\right) \cdot \min_j M_{ij} \right)``` |

(2) |

In the formula, $$\underset{j}{\mathrm{min}}{M}_{ij}$$ denotes the optimal matching distance of the i token in Sb to Sg, and vice versa. After weighted summation, the average is calculated and normalized to ensure that the score positively correlates with semantic consistency.

3.1.2. Domain-Specific Adaptation Optimization

To enhance the professionalism of feasibility study reports, the RCMD algorithm undergoes three optimizations:

(1) Topic Consistency Penalty: calculates the thematic consistency between generated text and baseline text, applying a penalty to semantic consistency scores accordingly. (2) Pre-trained Model Fine-tuning: strengthens the model’s ability to capture semantic nuances of domain-specific terminology such as “project investment”, “technical parameters”, and “policy standards”. (3) Key Sentence Weight Enhancement: for key sentences in the baseline text containing core data or technical indicators, the distribution vector weight d1(i) of their tokens is increased by 1.5 times to emphasize the importance of matching core information.

3.2. Information Integrity Assessment: BERT-NER Entity Retrieval Algorithm

Information integrity is achieved through an optimized BERT-NER model, which adopts a two-stage architecture of “pre-training followed by fine-tuning”. This model achieves an F1 score of 0.91 on general entity extraction tasks, making it suitable for both academic research and engineering implementation.

3.2.1. Core Principles of Entity Extraction

The BERT-NER model employs a labeling strategy to transform entity extraction into a sequence labeling task (labeling system: B-ORG (organization), I-ORG, B-LOC (location), I-LOC, B-DATE (date), I-DATE, B-NUM (number), I-NUM, O (non-entity)). Its core workflow is as follows:

- (1)

-

Text Encoding: Input text is processed through a BERT encoder to generate contextual semantic vectors, incorporating positional and segment encodings to distinguish text boundaries.

- (2)

-

Entity Decoding: Semantic vectors are mapped to the label space via a fully connected layer. A Conditional Random Field (CRF) model optimizes the plausibility of label sequences (e.g., preventing invalid annotations like “B-ORG” immediately followed by “B-LOC”).

- (3)

-

Entity Filtering: Post-processes decoded results by filtering out entity fragments shorter than 2 tokens and merging consecutive entities of the same type (e.g., “2024” and ‘December’ are merged into “December 2024”).

3.2.2. Core Principles of Entity Extraction

Using the baseline text Sb and the key entity set Eb = {eb1,eb2,┄,ebn} extracted via BERT-NER as the reference, the entity set Eg = {eg1,eg2,┄,egn} extracted from the generated text Sg is defined. Information recall rate is defined as shown in Equation (3).

|

```latexRecall=\frac{|{E}_{g}\cap {{E}_{b}}^{\prime}|}{|{E}_{b}|}``` |

(3) |

Eb′ represents the domain adaptation expansion set for Eb: Considering the diversity of entity expressions in the feasibility study report (e.g., “XX Co., Ltd.” may be abbreviated as “XX Company”), an entity synonym mapping table is constructed using the domain dictionary. Expressions synonymous with Eb entities in Eg are included in the matching scope to ensure the validity of recall rate calculations.

3.3. Structural Compliance Assessment: Chapter Structure Tree Matching Algorithm

Structural compliance is achieved by constructing a five-core chapter structure tree T = {t1,t2,┄,t5} encompassing “Objectives, Technology, Economics, Environment, Conclusions”. Each chapter tk corresponds to a set of domain-specific keywords, with compliance scores calculated using a keyword weight matching algorithm.

Structure Tree Construction: Define hierarchical relationships and characteristic keywords for each section based on industry standards. Assign weight ωk to each keyword (set according to its distinctiveness within the section, e.g., “core technology” weight 0.8, “technical parameters” weight 0.5).

Generated Text Chapter Identification: Segment the generated text into paragraphs and match them with keywords. Calculate the sum Wk of keyword weights matching each chapter tk. If Wk exceeds the threshold θ (set to 0.6 via cross-validation), the chapter is deemed present.

Compliance Score Calculation: Define the compliance score as the ratio of matched chapters to the baseline total number of chapters, as expressed in Equation (4).

|

```latexCompliance = \frac{\displaystyle\sum_{k=1}^{5} \mathrm{I}\left(W_k \ge \theta\right)}{5}``` |

(4) |

where I (⸳) is an indicator function that takes the value 1 when the condition is satisfied and 0 otherwise.

3.4. Expression Fluency Assessment

Fluency is quantified using the “Qwen3-Max” model, which demonstrates high consistency with human experts in text quality evaluation tasks through its trillion-parameter pre-training.

3.4.1. Evaluation Dimensions and Prompt Design

The evaluation dimensions focus on the practical requirements of feasibility studies, encompassing three core indicators, each with clearly defined assessment criteria, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Prompt Scoring Dimensions Table.

|

Scoring Dimension |

Evaluation Criteria |

Weights |

|---|---|---|

|

Grammatical Correctness |

No grammatical errors, accurate word choice, and standardized use of technical terminology |

0.3 |

|

Sentence Coherence |

Natural paragraph transitions, complete logical chain, and no semantic discontinuity |

0.4 |

|

Professionalism |

Compliant with the formal register of feasibility study reports, precise technical expression, and no colloquial or ambiguous language |

0.3 |

Design standardized prompt to ensure scoring consistency: “As a feasibility study review expert, please evaluate the following text on a scale of 0–100 based on three dimensions: grammatical accuracy, sentence coherence, and professionalism. Round scores to one decimal place and output the total score. Text: [Generated text content]”.

3.4.2. Score Normalization

Given that Qwen3-Max scores operate on an absolute scale of [0, 100], they are rescaled to the [0, 1] interval via min-max normalization, as defined in Equation (5).

|

```latexFluenc{y}_{norm}=\frac{Fluenc{y}_{raw}}{100}``` |

(5) |

where Fluencyraw represents the raw score output by the API, and Fluencynorm ∈ [0, 1] denotes the normalized fluency metric.

3.5. Comprehensive Scoring Algorithm

The composite score employs a weighted sum model, with weights determined by the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) based on the practical application scenarios outlined in the feasibility study report: Semantic Consistency (0.2), Information Completeness (0.3), Structural Compliance (0.3), and Expressive Fluency (0.2). The final composite score formula is Equation (6).

|

```latexTotalScore=0.2×Sim+0.3×Recall+0.3×Compliance+0.2×Fluenc{y}_{norm}``` |

(6) |

This weighting scheme emphasizes the central importance of “factual accuracy” while also balancing “format standardization” and “readability of expression”, thereby meeting the requirements for feasibility studies to serve as a basis for decision-making.

4. Experimental Results and Discussion

4.1. Experimental Setup and Evaluation Data

This experiment compares three generative systems with distinct technical approaches: the “LLM_only” system relying solely on foundational language models, the “RAG + LLM” system integrating retrieval-augmented generation technology, and the “RAG + LLM + Workflow” system incorporating workflow optimization. To ensure rigorous and diverse evaluation, the benchmark dataset comprises one primary core case and three supplementary test cases. The core assessment case employs a feasibility study report for a standard offshore wind power project with a total installed capacity of 1000 MW. Characterized by its large scale, high technical complexity, intricate chapter structure, and substantial volume of heterogeneous data, the project serves as a rigorous stress test for the system’s data processing and logical orchestration capabilities. Its performance is quantified through four core metrics, with detailed experimental data presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Evaluation Table of Experimental Results Across All Dimensions.

|

Systems |

Semantic Consistency |

Information Coverage |

Structure Compliance |

Expression Fluency |

Overall Score |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

LLM_only |

0.1909 |

0.0500 |

0.1358 |

0.8950 |

0.2784 |

|

|

RAG + LLM |

0.6366 |

0.1594 |

0.3942 |

0.8950 |

0.4966 |

|

|

RAG + LLM + Workflow |

0.6592 |

0.3908 |

0.5123 |

0.8950 |

0.5965 |

Note: Bold indicates the best performance in each category.

4.2. Analysis of Results Across Dimensions

4.2.1. Semantic Consistency Evaluation Results

The semantic consistency metric results show that the “RAG + LLM + Workflow” system scored 0.6592, demonstrating its advantage in semantic preservation. The “LLM_only” system scored 0.1909, potentially indicating issues such as topic deviation or inappropriate terminology usage, reflecting limitations in its professional semantic understanding. The “RAG + LLM” system’s score of 0.6366 represents a significant improvement over the base model, demonstrating that the introduction of retrieval mechanisms contributes to enhanced semantic accuracy.

4.2.2. Information Integrity Assessment Results

The information completeness assessment based on the BERT-NER model indicates that in terms of information coverage, the “RAG + LLM + Workflow” system scored 0.3908, demonstrating its ability to comprehensively cover key information. The “LLM_only” system achieved a coverage rate of 0.0500, indicating its difficulty in autonomously ensuring the completeness of specialized content. While the “RAG + LLM” system’s score of 0.1594 outperforms the baseline model, it still lags behind the workflow-enhanced system, reflecting the workflow mechanism’s additional gains in information integration. This demonstrates that relying solely on language models without integrating domain knowledge retrieval struggles to ensure the informational completeness of professional documents.

4.2.3. Structural Compliance Assessment Results

In the structural compliance assessment, the “RAG + LLM + Workflow” system scored 0.5123, indicating greater reliability in adhering to standard documentation structure. The “LLM_only” system scored 0.1358, suggesting potential issues such as missing sections or logical inconsistencies. The “RAG + LLM” system showed significant improvement in structural organization with a score of 0.3942, though it still falls short of the workflow system’s level. Although the “LLM_only” system achieved a basic fluency score of 0.8950, its structural compliance score was only 0.1358. Key issues include: (1) Disrupted chapter logic, with a lack of coherence between the technical solution and economic analysis sections. (2) Missing standard chapters, such as the complete omission of the critical “Risk Analysis and Countermeasures” section. This underscores the necessity of structured templates in professional document generation.

4.2.4. Fluency Assessment Results

In terms of expression fluency, the three systems scored identically, indicating comparable performance in linguistic coherence and naturalness of expression. This demonstrates that the introduction of retrieval-enhanced and workflow mechanisms did not compromise textual fluency, with each system capable of generating content of high linguistic quality.

4.3. Discussion on Overall Performance

4.3.1. Validation of Technical Approach Effectiveness

The comprehensive score indicates that the “RAG + LLM + Workflow” system significantly outperforms both “RAG + LLM” and “LLM_only” systems. This demonstrates that the combined strategy of “retrieval augmentation + workflow optimization” holds a distinct advantage in generating feasibility study reports. The retrieval mechanism provides domain-relevant knowledge to the model, while the workflow design further enhances content structuring and information organization capabilities, collectively driving the overall performance improvement. Crucially, the integration of the Knowledge Graph significantly mitigates the “hallucination” issues inherent in the “LLM_only” model. As evidenced by the NER analysis, the “LLM_only” system failed to recognize most of key entities, largely because it relied on probabilistic parametric memory which often fabricates technical parameters and economic indicators. In contrast, the Knowledge Graph anchors the generation process to a structured “factual foundation” derived from authoritative policy and project documents. This ensures that critical entities are retrieved and validated against the graph’s “entity-attribute” mappings before generation, thereby transforming the system from a creative probabilistic model into a reliable, evidence-based reporting tool. The observed performance enhancement stems primarily from:

- (1)

-

The retrieval mechanism ensures accurate infusion of domain knowledge.

- (2)

-

The workflow design guarantees standardized document structure.

- (3)

-

Multi-stage quality control reduces semantic deviation.

After weight adjustment, the importance of information completeness and structural compliance is highlighted, aligning more closely with the practical requirements of feasibility reports as decision-making reference documents. We excluded a standalone “LLM + Workflow” baseline because professional reports require strict factual grounding. Without retrieval-augmented domain knowledge, the workflow would merely organize hallucinations into a standardized format. Therefore, the “LLM_only” system suffices as the representative baseline for scenarios lacking external data support, confirming that accurate data retrieval is a prerequisite for effective workflow execution.

4.3.2. Correlation Analysis of Various Indicators

Based on the performance of each system, semantic consistency, information coverage, and structural compliance exhibit a positive correlation trend and align closely with the overall score. While expressive fluency remains consistent across systems, it does not serve as a key differentiator in system performance. This finding indicates that in professional document generation scenarios, content accuracy, information completeness, and structural standardization exert a more critical influence on overall quality.

4.3.3. System Robustness and Adaptability Analysis

To assess the system’s generalizability across diverse offshore wind scenarios, we conducted extended experiments on three distinct project types: standard fixed-bottom projects, complex floating projects, and small-scale (300 MW) projects. The corresponding experimental data are presented in Table 3.

As evidenced by the comparative results, the “RAG + LLM + Workflow” system exhibits remarkable robustness, maintaining consistent high performance across heterogeneous scenarios. Specifically, the performance discrepancy between the primary case and the standard fixed-bottom case was negligible (<0.3%), underscoring the high stability of the workflow architecture when applied to standardized engineering templates. Furthermore, regarding adaptability to complexity, the system achieved a comprehensive score of 0.5836 even in floating offshore wind projects characterized by intricate hydrodynamic terminology. Notably, structural compliance in this complex scenario remained robust at 0.4600, significantly outperforming the “LLM_only” model. Conversely, in the 300 MW small-scale project category, the system demonstrated enhanced efficacy, achieving its peak overall score of 0.6278 accompanied by an information coverage rate of 0.4768.

Collectively, these findings corroborate that the proposed framework avoids overfitting to specific project templates. The workflow ensures structural integrity regardless of project variations, while the RAG module provides essential domain adaptability, jointly ensuring the system’s robustness across diverse engineering applications.

Table 3. Quantitative Assessment of System Generalizability Across Distinct Offshore Wind Project Types.

|

Systems & Projects |

Semantic Consistency |

Information Coverage |

Structure Compliance |

Expression Fluency |

Overall Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

LLM_only (standard fixed-bottom) |

0.1936 |

0.0136 |

0.2134 |

0.8950 |

0.2838 |

|

RAG + LLM (standard fixed-bottom) |

0.6341 |

0.2600 |

0.3333 |

0.8950 |

0.5139 |

|

RAG+LLM+Workflow (standard fixed-bottom) |

0.6667 |

0.4133 |

0.4600 |

0.8950 |

0.5950 |

|

LLM_only (complex floating) |

0.1917 |

0.0077 |

0.2000 |

0.8950 |

0.2788 |

|

RAG + LLM (complex floating) |

0.6369 |

0.2040 |

0.2333 |

0.8950 |

0.4779 |

|

RAG + LLM + Workflow (complex floating) |

0.6619 |

0.3800 |

0.4600 |

0.8950 |

0.5836 |

|

LLM_only (small-scale) |

0.1938 |

0.0135 |

0.1413 |

0.8950 |

0.2695 |

|

RAG + LLM (small-scale) |

0.6338 |

0.1621 |

0.3467 |

0.8950 |

0.4871 |

|

RAG + LLM + Workflow (small-scale) |

0.6590 |

0.4768 |

0.5401 |

0.8950 |

0.6278 |

Note: Bold values indicate the data for the system with the best performance in each metric.

4.3.4. Failure Mode Analysis

The “LLM_only” system performed poorly across multiple metrics, indicating its difficulty in meeting professional document generation requirements without external knowledge support. The “RAG + LLM” system demonstrated significant improvements in most dimensions, yet still fell short of workflow-integrated systems in terms of information coverage and structural compliance. This highlights the workflow mechanism’s role in further strengthening information integration and structural control.

4.4. Limitations and Areas for Improvement

Although the “RAG + LLM + Workflow” system demonstrates superior performance across multiple dimensions, its semantic consistency and information coverage still hold room for improvement. In terms of computational efficiency, the architecture inevitably introduces higher inference latency compared to single-pass LLM generation methods. The multi-step process, involving intent recognition, iterative knowledge retrieval, and cross-chapter logical validation, increases the time-to-output. However, this latency is acknowledged as a necessary trade-off to ensure the “controllability” and “accuracy” required for professional engineering reporting.

Furthermore, when addressing highly novel or non-standard project structures, although technical specifications and regulations within the RAG module can be updated, the generation logic may still necessitate alignment with specific project characteristics. The system’s configurable YAML workflow addresses this issue by enabling engineers to rapidly adjust logical templates. This ensures that the system can flexibly adapt to unique project requirements through low-code configuration, maintaining high generation quality even in non-standard scenarios. Future work can focus on the following areas: enhancing domain-adaptive retrieval mechanisms, optimizing multi-stage content quality control within workflows, and exploring more granular structural compliance modeling approaches.

5. Conclusions

Analysis of experimental results demonstrates that the ‘retrieval-augmented generation + workflow optimization’ technical approach exhibits significant advantages in the task of automatically generating feasibility study reports. The “RAG + LLM + Workflow” system achieved the best performance across key metrics including semantic consistency, information coverage, and structural compliance. Specifically, the “Cyclic Aggregation Mode” proved critical in handling complex report structures by enabling cross-chapter logical coordination and data aggregation for subprojects. Its overall score improved by approximately 114% compared to the baseline language model system, significantly outperforming the intermediate system that employed retrieval augmentation alone. Weight adjustments better reflect the dual requirements of feasibility studies as formal decision-making documents: demanding strict content accuracy (information completeness + semantic consistency) while emphasizing standardized document structure (structural compliance + expressive fluency). Through scientific weight allocation and systematic experimental validation, this study provides a more practical methodological foundation for evaluating and optimizing professional document auto-generation systems.

The evaluation results accurately reflect the core requirements of professional document generation tasks: while ensuring expressive fluency, the system should prioritize the accuracy of professional content, the completeness of information, and the standardization of document structure. Through multidimensional quantitative assessment and systematic comparison, this study validates the effectiveness of the composite technical approach in professional document generation, providing methodological references and practical foundations for optimizing related systems and their real-world applications.

Beyond immediate performance metrics, this study aligns with the broader dynamics of technological innovation. As highlighted by Pazhouhan et al. [26]. in their patent landscape analysis of renewable energy, emerging technologies evolve through complex “innovation clusters” and distinct maturity stages. Our system serves as a critical digital adaptation to manage this growing technical complexity, bridging the gap between exploding information volumes and standardized engineering applications.

Looking forward, we aim to extend the system’s applicability to more complex, high-demand scenarios. First, we plan to adapt the “Market Analysis” and “Technical Solution” modules to support the integration of high-load consumers, such as data centers. By incorporating methodologies for optimizing renewable consumption through computing-load migration and storage [27], the system can generate sophisticated strategies for “energy-computing” synergy projects. Second, to enhance the depth of the “Risk Analysis” module, we intend to integrate stochastic optimization models. Drawing on frameworks that handle composite uncertainty [28], future iterations will account for both exogenous and endogenous variables, thereby significantly improving the robustness of automated economic and technical feasibility assessments.

Future research may further focus on adaptive optimization for specialized domains and deep consistency modeling for long document structures, thereby continuously enhancing the quality and practical value of automated professional document generation.

Statement of the Use of Generative AI and AI-Assisted Technologies in the Writing Process

In the preparation of this work, the authors utilized DeepSeek to assist with grammatical corrections of the manuscript. Following the use of this tool, the authors reviewed and edited the content as necessary and assume full responsibility for the publication’s content.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the financial support of Nanning city science and Technology Bureau.

Author Contributions

Methodology, M.L.; Software, T.L.; Validation, Y.Y.; Investigation T.L., X.M. and Z.J.; Writing Original Draft Preparation, T.L.; Review & Editing, J.Z. and Y.W.; Supervision, Q.M.; Project Administration, M.L.; Funding Acquisition, M.L.

Ethics Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

Funding

This research was funded by the Key R&D Program of the Nanning Science Research and Technology Development Plan grant number (20253057).

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

-

Wang B, Zhang J, Chen Y, Zhu H, Teng L. Effects of Platform Motions on Dynamic Responses in a Floating Offshore Wind Turbine Blade. Mar. Energy Res. 2025, 2, 10018. DOI:10.70322/mer.2025.10018 [Google Scholar]

-

Zhang S, Lu Y, Huang Q, Liu M. Hybrid Encoder–Decoder Model for Ultra-Short-Term Prediction of Wind Farm Power. Smart Energy Syst. Res. 2025, 1, 10004. DOI:10.70322/sesr.2025.10004 [Google Scholar]

-

Gao X, Dong X, Ma Q, Liu M, Li Y, Lian J. Marine Photovoltaic Module Salt Detection via Semantic-Driven Feature Optimization in Mask R-CNN. Mar. Energy Res. 2025, 2, 10015. DOI:10.70322/mer.2025.10015 [Google Scholar]

-

Perez-Moreno SS, Zaaijer MB, Bottasso CL, Dykes K, Merz KO, Rethore P-E, et al. Roadmap to the multidisciplinary design analysis and optimization of wind energy systems. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2016, 753, 062011. DOI:10.1088/1742-6596/753/6/062011 [Google Scholar]

-

Pires ALG, Junior PR, Morioka SN, Rocha LCS, Bolis I. Main Trends and Criteria Adopted in Economic Feasibility Studies of Offshore Wind Energy: A Systematic Literature Review. Energies 2021, 15, 12. DOI:10.3390/en15010012 [Google Scholar]

-

Ospino-Castro A, Robles-Algarín C, Mangones-Cordero A, Romero-Navas S. An Analytic Hierarchy Process Based Approach for Evaluating Feasibility of Offshore Wind Farm on the Colombian Caribbean Coast. Int. J. Energy Econ. Policy 2023, 13, 64–73. DOI:10.32479/ijeep.14621 [Google Scholar]

-

Hyari K, Kandil A. Validity of Feasibility Studies for Infrastructure Construction Projects. Jordan J. Civ. Eng. 2009, 3, 66–12. Available online: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:28715125 (accessed on 1 January 2026).

-

Oelker S, Sander A, Kreutz M, Ait-Alla A, Freitag M. Evaluation of the Impact of Weather-Related Limitations on the Installation of Offshore Wind Turbine Towers. Energies 2021, 14, 3778. DOI:10.3390/en14133778 [Google Scholar]

-

Lee J, Kim S, Kwak N. Unlocking the Potential of Diffusion Language Models through Template Infilling. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2510.13870. DOI:10.48550/arXiv.2510.13870 [Google Scholar]

-

Soori M, Arezoo B, Dastres R. Artificial intelligence, machine learning and deep learning in advanced robotics, a review. Cogn. Robot. 2023, 3, 54–70. DOI:10.1016/j.cogr.2023.04.001 [Google Scholar]

-

Janocha MJ, Lee CF, Wen X, Ong MC, Raunholt L, Søyland S, et al. Exploring the Technical Boundaries in Upscaling Floating Offshore Wind Turbines. In Proceedings of the ASME 2024 43rd International Conference on Ocean, Offshore and Arctic Engineering, Singapore, 9–14 June 2024; Volume 87851, p. V007T09A047. DOI:10.1115/OMAE2024-128063. [Google Scholar]

-

Xu X, Zhao L, Xu H, Chen C. CLaw: Benchmarking Chinese Legal Knowledge in Large Language Models—A Fine-grained Corpus and Reasoning Analysis. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2509.21208. DOI:10.48550/arXiv.2509.21208 [Google Scholar]

-

Wang Z, Gao J, Danek B, Theodorou B, Shaik R, Thati S, et al. Compliance and factuality of large language models for clinical research document generation. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2025, ocaf174. DOI:10.1093/jamia/ocaf174 [Google Scholar]

-

Walker C, Rothon C, Aslansefat K, Papadopoulos Y, Dethlefs N. SafeLLM: Domain-Specific Safety Monitoring for Large Language Models: A Case Study of Offshore Wind Maintenance. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.10852. DOI:10.48550/arXiv.2410.10852 [Google Scholar]

-

Akkiraju R, Xu A, Bora D, Yu T, An L, Seth V, et al. FACTS about building retrieval augmented generation-based chatbots. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2407.07858. DOI:10.48550/arXiv.2407.07858 [Google Scholar]

-

Ma X, Xie X, Wang Y, Wang J, Wu B, Li M, et al. Diagnosing Failure Root Causes in Platform-Orchestrated Agentic Systems: Dataset, Taxonomy, and Benchmark. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2509.23735. DOI:10.48550/arXiv.2509.23735 [Google Scholar]

-

Es S, James J, Espinosa Anke L, Schockaert S. RAGAs: Automated Evaluation of Retrieval Augmented Generation. In Proceedings of the 18th Conference of the European Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: System Demonstrations; Aletras N, De Clercq O, Eds.; Association for Computational Linguistics: St. Julians, Malta, 2024; pp. 150–158. DOI:10.18653/v1/2024.eacl-demo.16 [Google Scholar]

-

Bandaru SH, Becerra V, Khanna S, Espargilliere H, Torres Sevilla L, Radulovic J, et al. A General Framework for Multi-Criteria Based Feasibility Studies for Solar Energy Projects: Application to a Real-World Solar Farm. Energies 2021, 14, 2204. DOI:10.3390/en14082204 [Google Scholar]

-

Hogan A, Blomqvist E, Cochez M, D’amato C, Melo GD, Gutierrez C, et al. Knowledge Graphs. ACM Comput. Surv. 2022, 54, 1–37. DOI:10.1145/3447772 [Google Scholar]

-

Gao Y, Li R, Croxford E, Caskey J, Patterson BW, Churpek M, et al. Leveraging Medical Knowledge Graphs into Large Language Models for Diagnosis Prediction: Design and Application Study. JMIR AI 2025, 4, e58670. DOI:10.2196/58670 [Google Scholar]

-

Liu P, Yuan W, Fu J, Jiang Z, Hayashi H, Neubig G. Pre-train, Prompt, and Predict: A Systematic Survey of Prompting Methods in Natural Language Processing. ACM Comput. Surv. 2023, 55, 1–35. DOI:10.1145/3560815 [Google Scholar]

-

Nandini D, Koch R, Schönfeld M. Towards Structured Knowledge: Advancing Triple Extraction from Regional Trade Agreements Using Large Language Models. In Web Engineering; Verma H, Bozzon A, Mauri A, Yang J, Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 3–10. DOI:10.1007/978-3-031-97207-2_1 [Google Scholar]

-

Lee S, Lee D, Jang S, Yu H. Toward Interpretable Semantic Textual Similarity via Optimal Transport-based Contrastive Sentence Learning. In Proceedings of the 60th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), Dublin, Ireland, 22–27 May 2022; Muresan S, Nakov P, Villavicencio A, Eds.; Association for Computational Linguistics: Dublin, Ireland, 2022; pp. 5969–5979. DOI:10.18653/v1/2022.acl-long.412 [Google Scholar]

-

Lin C-Y. ROUGE: A Package for Automatic Evaluation of Summaries. In Proceedings of the Workshop on Text Summarization Branches Out, Barcelona, Spain, 25–26 July 2004; Association for Computational Linguistics: Barcelona, Spain, 2004; pp. 74–81. Available online: https://aclanthology.org/W04-1013/ (accessed on 1 January 2026).

-

Papineni K, Roukos S, Ward T, Zhu W. BLEU: A Method for Automatic Evaluation of Machine Translation. In Proceedings of the 40th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 7–12 July 2002; Association for Computational Linguistics: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2002; pp. 311–318. DOI:10.3115/1073083.1073135 [Google Scholar]

-

Pazhouhan M, Karimi Mazraeshahi A, Jahanbakht M, Rezanejad K, Rohban MH. Wave and tidal energy: A patent landscape study. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 1967. DOI:10.3390/jmse12111967 [Google Scholar]

-

Du Z, Yin H, Zhang X, Hu H, Liu T, Hou M, et al. Decarbonisation of data centre networks through computing power migration. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE 5th International Conference on Computer Communication and Artificial Intelligence (CCAI), Haikou, China, 23–25 May 2025; pp. 871–876. DOI:10.1109/CCAI65422.2025.11189418 [Google Scholar]

-

Giannelos S, Konstantelos I, Zhang X, Strbac G. A stochastic optimization model for network expansion planning under exogenous and endogenous uncertainty. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2025, 248, 111894. DOI:10.1016/j.epsr.2025.111894 [Google Scholar]