Life Cycle Assessment of the Emissions Reduction Potential of Recycled-Carbon-Fibre for Western-Australian Offshore Wind Turbine Blades

Received: 04 December 2025 Revised: 29 December 2025 Accepted: 13 January 2026 Published: 19 January 2026

© 2026 The authors. This is an open access article under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

1. Introduction

The growing demand for renewable energy has driven the rapid development of wind turbines to combat climate change. When wind farms approach end-of-life stages, it is important to consider how high-environmental-impact materials can be reused and recycled. Carbon-fibre (CF) is being consumed in high quantities by the wind industry; there are currently, however, nominal recycling opportunities for a circular economy in offshore Western Australian markets.

Australia, a signatory of the Paris Agreement, pledges net-zero green-house-gas (GHG) emissions by 2050; Australia’s electricity sector accounted for 35% of its GHG emissions in 2024, with non-renewable sources such as coal contributing 56% of total electricity generation [1,2]. Renewable energy, however, is a major step towards reducing Australia’s GHG emissions, and focusing on (offshore) wind energy can provide an almost constant, reliable source of electricity that’s not limited by cloud cover or day/night cycles [3,4]. Offshore wind farms require less land and are argued to be highly cost-effective at $3223/kW, compared to coal at $6037/kW [5]. Australia has pegged 6 areas for new offshore wind project development; currently, there are no national offshore turbines [1,6,7].

Weight is a key criterion in improving the efficiency of energy production for wind turbines, as lighter turbine components, specifically turbine blades, allow manufacturing bigger turbines with higher electricity generating capacity [8]. Traditionally, wind turbine blades were made of glass-fibre (GF), but there has been a shift in the industry to using carbon-fibre (CF) for the main blade material [3]. Compared to GF, the density of CF is 30% lower, and the strength is 40% higher; CF blades also have improved fatigue resistance, leading to the uptake in CF use for turbine blades. In 2021, global CF consumption was approximately 181 kilotons. Due to its use in wind turbine blades, the wind energy industry is now the leading consumer of CF worldwide, accounting for 28% of global supply. Although beneficial to energy efficiency, such high use of CF may have negative environmental consequences.

During the production stage of CF, high temperatures of 200–300 °C are required for the oxidation of polymeric fibre. The next process involves a carbonisation process requiring temperatures of 1000–1200 °C [9]. These high temperatures are achieved by furnaces using electrical power, requiring a huge energy draw, which is costly for the environment, depending on the type of electricity production relied upon. Usage of predominantly non-renewable energy to power these furnaces can have a major CO2 emissions reduction.

CF production also directly emits GHGs into the atmosphere. Large amounts of hydrogen cyanide (HCN), methane (CH4), ammonia (NH3), carbon monoxide (CO) and other hydrocarbon-rich compounds are released during production, and are either emitted to the atmosphere or incinerated to convert to CO2, which contributes to further energy costs and emissions [10]. According to past research [11,12,13], which compiled various data sources to estimate the average climate change impact of CF production, 13.0 to 34.1 kg CO2 equivalent (CO2eq) is emitted per kg of CF. These values are based on polyacrylonitrile carbon fibre (PAN) based CF, which is considered the predominant type of CF produced.

End-of-life impacts must be considered, since the application of CF is for wind turbine blades with an expected lifespan of 20 years [14]. Currently, most turbine blade waste is disposed of in landfills [15], but this is inefficient because the energy invested in production cannot be reclaimed, and, depending on the country, disposal land can be scarce. In the US alone, it is estimated that by 2050, there will be a total of 2.2 million t of turbine blade waste [16]. Although larger countries such as Australia have abundant land for disposal, it is important to consider other options early. The wasted energy potential from the production stage must also be considered to reclaim the lost potential energy stored within the blade waste material; thus, current disposal of blade waste to landfills necessitates recycling approaches.

The current methods of recycling globally include mechanical recycling, cement co-processing, pyrolysis and solvolysis [17]. Mechanical recycling involves breaking down turbine blade waste into small pieces that can then be used as aggregates in construction materials. Cement co-processing is the process of using the CF as fuel in a cement kiln, with the remaining constituent being used as feedstock for cement clinker [17]. Although these two methods of recycling remove blade waste from landfills, they are not circular in nature, can release further emissions, and other materials can be used in place of the blade waste material for these processes. Pyrolysis and solvolysis, on the other hand, are two recycling processes that support the circular economy, a concept in which materials are recycled and reused to reduce new raw material consumption [18], thereby preventing blade waste and new raw material consumption. These methods involve using thermal or chemical-based processes to break down CF waste material into high quality usable fibres and resins that have the potential to be remanufactured into new recycled carbon fibre (rCF) turbine blades.

Although work appears limited in the consideration of a full, life cycle analyses (LCA) of recycled-carbon-fibre rCF blades’ environmental impacts in the southern hemisphere, research [19] does review emissions comparison between GF blades and rCF hybrid blades across Europe where, improvements in global warming potential are stated as between 27 to 45% (Sweden is an area for recycling due to its majority renewable energy powered electricity grid). European data may, however, skew the emissions improvements in the rCF blades’ favour, as there will be little to no emissions due to electricity when producing and recycling CF, which are both energy intensive procedures. There are also differences in infrastructure for recycling and production, as well as transportation distances, when trying to apply the results of European reports to other locations; gaps for Australasian applications become evident. Some available work [19] compares rCF blades with GF blades, but not virgin-carbon-fibre vCF blades. Due to Australia’s fledgling offshore wind industry, most farms will utilise some form of CF blades, as regional offshore turbines require stronger, lighter components to compensate for higher offshore wind speeds. Therefore, it is important that a comparison can be made between vCF and rCF in an antipodean context; being the same base material, they are more comparable and will likely be the predominant options for future Australian offshore turbines, where there is no current deployment.

Given the above, this work focuses on the feasibility and GWP comparison of standard virgin-carbon-fibre (vCF) wind turbine blades and recycled-carbon-fibre (rCF) wind turbine blades in an Australian context where no offshore turbines are yet in place.

1.1. Policy, Regulation and Recycling

No explicit international standards, codes or regulations encompass a fully integrated guide for rCF production, applications’ use and strength requirements. For vCF, on the other hand, international standards include ISO11566 (tensile properties), ISO13003/ 14125 (fatigue /properties) and, ISO527-5 (tensile properties), focusing on the strength properties of vCF. If rCF can meet the same requirements and be incorporated into these documents, then rCF becomes a viable alternative to vCF for both structural and non-structural applications. Globally, countries have begun to implement various guidance, policies and regulations that cover wind turbine blade waste materials’ disposal. France has introduced legislation to encourage blade waste recycling [20], while Germany [21] and China [22] have introduced landfilling bans on blade waste. Denmark has also introduced research and development programs for the recycling of blade waste [23]. Currently, although Australia has a national waste policy action plan [24], policies are less clearly defined and consist of waste reduction targets such as 80% resource recovery from waste by 2030, which are not directly applicable to the wind/ offshore wind industry. There is an opportunity for Australia to reach waste reduction and recycling targets if policies for blade waste are re-structured, encouraging wind turbine manufacturers to avoid excessive landfill usage. As rCF blades are a relatively new technology that has yet to be established as a conventional blade type, this work is deemed important to assess the feasibility of rCF blades.

1.2. Energy and Environmental Considerations, and Industry Uptake

The consequences of disposing of blade waste in a landfill open opportunities for recycling. The current methods of recycling include pyrolysis, and solvolysis, and cement co-processing and mechanical recycling, which involves breaking down turbine blade waste into small pieces that can then be used for aggregates in construction materials [17]. Findings from the literature indicate that pyrolysis has an energy demand of 3 to 30 MJ/kg of CF [25,26], which can lead to potentially high GHG emissions depending on the electricity mix used. Although pyrolysis requires high temperature heating and therefore high energy consumption, when compared to vCF production, which requires 100–900 MJ/kg [27,28], it is relatively low. The burning-off of char during pyrolysis also releases GHGs directly into the atmosphere. There is little research regarding direct emissions; one study [24] covers the types and concentrations of gases released, with CO2, toluene and octane being the primary pollutants, but the volume of emissions per kg of CF consumed is less addressed.

Solvolysis uses chemical solvents to break down the polymer matrix, leaving the carbon fibres intact. Common chemical solvents include acetone, alcohols and amines. Solvolysis typically requires temperatures under 200 °C to break down the materials (versus the high temperatures of 300–800 °C required by pyrolysis). Solvolysis is argued to have minimal impact on CF quality; work [29] finds that rCF surfaces appear unaffected by solvolysis when scanned by an electron microscope. Other studies similarly note that methanesulfonic acid used for solvolysis leaves no residue on fibres, whilst other work finds rCF surfaces identical to vCF after solvolysis [27,30]. This is primarily due to the nature of solvolysis chemicals, which only react with the resin used, leading to no damage to the actual fibres; fibre length is also unaffected and is only limited by the vessel size used for solvolysis. Research [31] also compared the environmental impact of solvolysis in comparison with landfilling and reported a climate change impact of almost zero for solvolysis. This study, however, used French nuclear power as its primary electricity mix and did not consider the impacts of obtaining the solvents used. Other work [32] conducted a full cradle to grave analysis of several solvolysis methods and determined an energy consumption of 9.5 MJ/kg (supercritical water) to 69.45 MJ/kg (1-Propanol) of CF recycled. Although not zero, this research indicates relatively low energy consumption when compared to vCF. GWP was also studied for each solvent [32], displaying impact categories separately. When compared, it can be observed that SC Ethylene Glycol has the lowest emissions at 1.11 kg CO2eq, with SC Methanol having the highest at 7.4 kg CO2eq per kg of recycled material. Other work concluded that chemical recycling had 5 times less emissions of 1.2 kg CO2eq compared to pyrolysis, which falls within a similar range [33].

Real-world commercial application of rCF is progressing; major industries such as aerospace, automotive and cycling are exploring the use of this recyclate-feedstock. Boeing and Mitsubishi Chemical Group are trialling the use of rCF in non-structural airplane sidewall panels [34]; Boeing is also testing rCF sourced from airplane components for use in non-structural applications such as laptop cases [35]. McLaren is looking at the use of rCF in F1 car panels [36], and Asahi is experimenting with continuous rCF in various automotive components [37]. Giant bicycles retail a rCF bicycle with structural long strand fibres [38]. Notwithstanding the above, the lack of uptake in the wind-energy-market and its related limited recycling infrastructure necessitate options’ life-cycle-assessment comparisons.

1.3. Life Cycle Assessment

Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) is a widely accepted and standardised method for quantifying environmental impacts of products and processes throughout their entire life cycle from acquiring raw materials to final product disposal & recycling (cradle to grave, to cradle), with international standards governing LCA practices noted to include ISO14040/14044 (environmental management principles/ requirements). LCAs typically assess several environmental-impact categories, and calculate emissions input data/data available in a database [4,39]. LCA also calculates energy use, material use and waste generation, providing a holistic overview of a product’s life cycle [40]. In the context of CF composite wind turbine blades, LCA is particularly useful due to the high energy demands for emissions values associated with CF production and the importance of keeping emissions low for renewable infrastructure. The main environmental impact categories for an LCA are GWP, acidification, eutrophication, ozone layer depletion, abiotic depletion and ecotoxicity. Wind turbines are considered climate solutions and promoted as a low carbon alternative to fossil fuel-based energy, even although CF is somewhat of a carbon intensive material with high energy consumption, leading to high GHG emissions. In wind turbines, this results in GWP heavily outweighing other categories [41]. Towards clarity, this study focuses on the GHG emissions of carbon-fibre CF (both virgin—vCF, and recycled—rCF) wind turbine blades, for offshore Australia.

1.3.1. Virgin Carbon-Fibre—vCF—Blade LCAs

Whilst there are LCA studies calculating efficiency improvements in using CF in wind turbines [42], there is limited literature available on vCF LCAs specifically for emissions of wind turbine blades; some work [8] uses a functional unit of 1 kg of vCF with such a case-study in China, determining that the production stage of vCF has the biggest impact at 32.8 kg CO2eq per kg of vCF. The overall GWP value provided in literature limits somewhat insight into determining the environmental impact from wind turbine blades, as such work calculates the decarbonisation effect from energy generation (in comparison to non-renewables), which can often negate impacts; similarly, regional variables such as electricity grid mix and transport distances must be considered when applying findings to other countries. Another study [43] analysed whole wind turbines using LCA, finding blades contribute to 14% of total GWP, but this study presents values as gCO2eq per kWh of electricity produced, creating difficulties when comparing against turbine systems with different power ratings, or determining blade impact only; indeed such studies assume 50% of blade materials are incinerated adding higher emission values in comparison to landfill’s inert-waste. Overall, there appear to be gaps in finding simplified data for wind turbine blade GHG emissions for an Australian context.

1.3.2. Recycled Carbon-Fibre—rCF—Blade LCAs

There are several studies that cover recyclable wind turbine blades in the form of recyclable resins; one study [44] finds a 28% reduction in GHG emissions compared to standard blades, although the regional boundaries’ functional units are unspecified. Other work [45] finds a similar reduction of 30% this work does state the functional unit as a 13 m prototype blade in Ireland. Studies mostly cover recyclability for the resin and do not cover CF, which is argued to be a main contributor to emissions. A recent study [46] did assess rCF, but did not address a cradle to grave test as the production stage of materials was not considered; this study used a functional unit of key cumulative blade wastes and found a 2.5 to 3.5 Mt reduction in CO2 for rCF; the functional unit for this study is difficult to apply individually to wind farms and is more of a broad overview on the potential emissions reduction for the wind turbine blade market. The study also used a transport distance, between factories and wind farms, of 200 km, which may not accurately represent the required large travel distances in Australia, sea-to-shore vagaries notwithstanding. Existing studies did not consider the use of rCF back-into new blades, towards CF-circular-economies.

Currently, there is limited literature available on LCA for wind turbine blades constructed for rCF; one of the very few studies [19] has used LCA to calculate and compare the cradle to grave environmental impacts of a hybrid rCF turbine blade and standard GF turbine blade, albeit as mentioned, this is Europe-centric in approach. The lack of research on the GHG emissions or environmental impacts of rCF wind turbine blades reinforces the work presented here and offers recommendations to a fledgling offshore wind turbine industry in Western Australia.

The following discussion highlights the research herewith: Section 2 reviews the materials & methods of this work, namely virgin-carbon-fibre vCF, & recycled-carbon-fibre rCF comparisons; Section 3 notes a discussion of calculation validation; Section 4 presents the results & discussion of this research, such that vCF structural components’ replacement by rCF is viable; and Section 5 notes the conclusions & recommendation that rCF uptake is encouraged.

2. Materials and Methods

The aim of this project is to evaluate and compare the total GHG emissions in kg CO2eq of virgin-carbon-fibre vCF and recycled-carbon-fibre rCF wind turbine blades throughout the total blade lifespan, including raw materials, production, maintenance and end of life processes for wind turbines in Australia and to provide a recommendation on selecting vCF, or rCF. The objectives for this research are to: conduct a global review of rCF feasibility through research of secondary sources; compare global and Australian wind sector waste; conduct a comparison of vCF and rCF wind turbine blade GHG emissions; and fourthly, recommend an approach for CF use in the Australian wind industry based on GWP. Overall, the vCF and rCF blades are compared to determine the effect on GHG emissions of recycling CF blades and using the rCF in new blades, via a life cycle assessment (LCA) in which the life cycle inventory data is garnered form the Sphera/GaBi database [47] in line with ISO14040:2006 (environmental management). Any other data unavailable in Sphera/GaBi is obtained through secondary research sources.

Comparison involves 3 blade types: standard vCF, non-structural rCF and structural rCF. All GHG emissions are converted into CO2 equivalent emissions and calculated using the CML2001 (mid-point centric approach) that primarily focuses on the GHG emissions of the blade types; the financial aspects of all processes are excluded. Research only considers 3 options: vCF wind turbine blades with an end of life in landfill, rCF blades with recycled CF only used for non-structural components (e.g., GF), which will be recycled at end of life, and thirdly, rCF blades where recycled CF will be used for both structural and non-structural components and will be recycled at end of life. Other non-circular recycling methods, such as mechanical recycling into different products, are not considered. This LCA system boundary is Australia, with energy infrastructure, transport distances, production and disposal/recycling data based locally.

The functional unit for this LCA is a set of 3 fibre composite wind turbine blades, based on each vCF blade being 20 t, typical for large onshore blades (Table 1). Durability, power rating, dimensions and structure remain the same across the three blade types, but weight varies due to the density of CF, which replaces the GF in the rCF blade types. The manufacturing process involves acquiring/production of the main raw materials used for the blade in Victoria, including composite, foam core, protective coating, and resin for composite production, which are transported to the local blade assembly facility. These materials are then assembled into complete vCF wind turbine blades in one facility; vCF is used for the internal structural frame of the blade, and GF is used for the outer blade shell, with both composites using epoxy resin for infusion. PVC is used to fill the central voids of the blade, and the components are combined in a sandwich construction method. PU resin is used as a protective coating layer on the outside shell. 17% of materials used are consumed as production scrap and are disposed of in landfills [14]. Three blades of the same specifications are manufactured and transported via truck to an onshore wind farm site 596 km away (avg distance to nearest wind farms) and installed, thence transported offshore; the offshore transportation component is deemed a constant and excluded from this scope. After the use phase, the blades are disassembled and transported back to urban Victoria, where they are disposed of in a landfill without shredding or incineration, with offshore variables excluded from scope.

Manufacturing processing remains the same as for standard vCF blades, but the outer blade shell material is replaced with rCF instead of GF. Assembly methods, transportation, use and location remain the same. After the use phase, blades are disassembled and transported back to a recycling facility in rural Victoria, where both vCF and rCF are recycled. During the recycling process, solvolysis is used to produce rCF material, with 10% CF lost during recycling, and all non-CF scrap, such as resin, foam, and coating, is disposed of in a landfill. rCF is taken to the assembly facility, where new resin is used for infusion. rCF is not used for structural components. Manufacturing processes remain the same as non-structural rCF blades, except for the structural vCF frame being replaced by rCF in addition to the outer shell. Due to the loss of CF during recycling and manufacturing, CF scrap from additional sources, such as other turbine blades and aircraft components already in landfills, will be used to create the required rCF for the new blades.

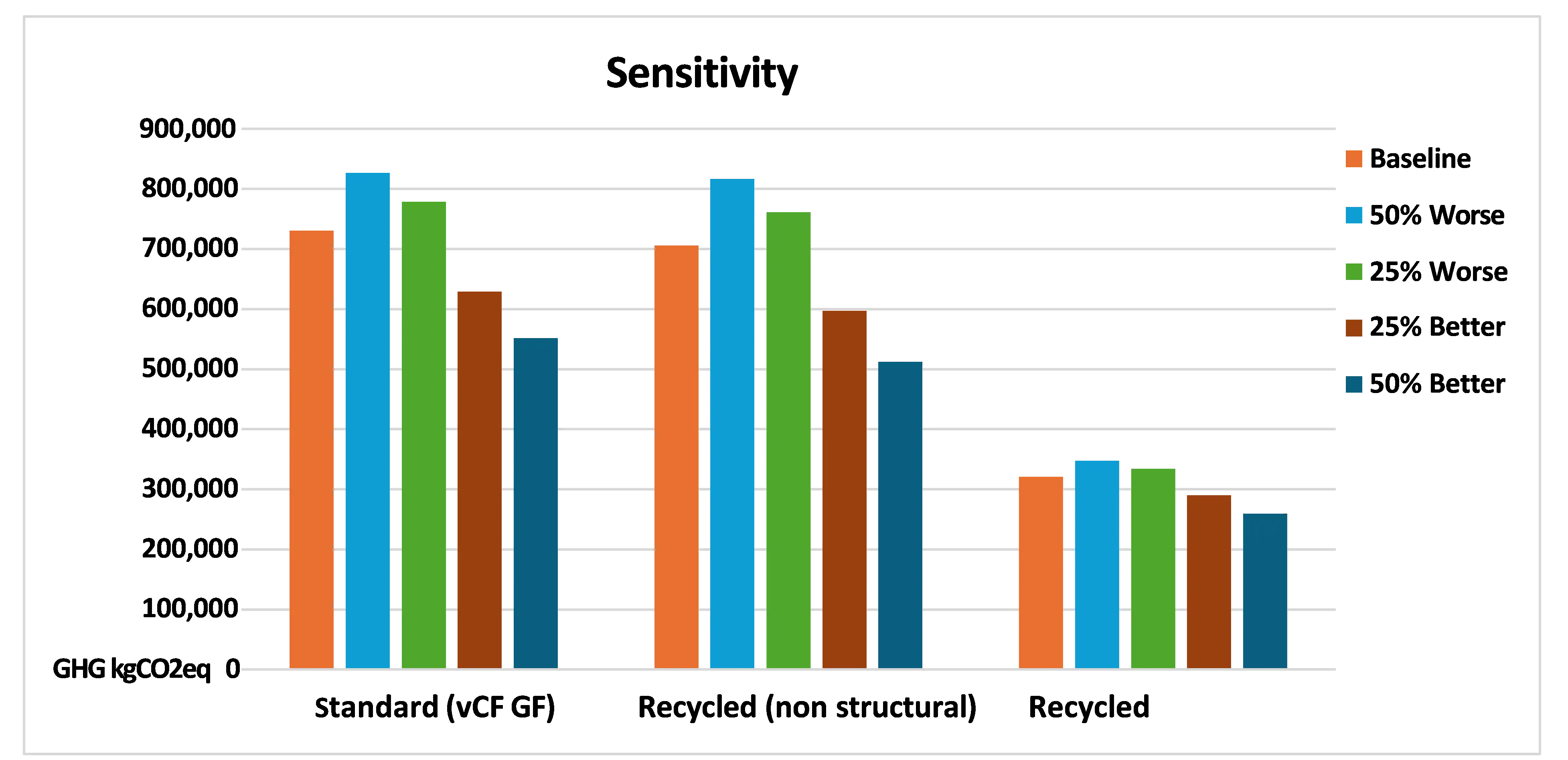

The LCI model is based on production in Victoria, the only known current wind turbine manufacturing site in Australia. Australian electricity grid mix is used to build all LCI sets, including energy consumption for CF manufacture, blade manufacture, PVC production and PU resin production. All LCI were built within GaBi [47] Education 9.2.1.68. CML2001 Jan. 2016 Global Warming Potential impact assessment is used to determine the GWP calculated in kg CO2eq, which is a conservative midpoint impact assessment methodology that is accepted by Australian Life Cycle Assessment Society -ALCAS, and compliant with ISO14040 (environ.mngmt). A sensitivity analysis determines the robustness of results; this is done by varying input parameters for high contribution processes [48,49]. The sensitivity analysis was performed to examine the effects of varying input data across the 3 main high-impact categories: electricity, CF production, and rCF recycling. Best and worst-case scenarios were modelled. The best-case scenarios used a decrease by 25–50% in electricity emissions, CF production energy consumption and rCF emissions. The worst-case scenarios used the baseline electricity emissions (assuming non-renewable energy would not increase), a 25–50% increase in CF production energy consumption and the same rCF emissions increase. This is in line with other uncertainty studies [46].

Table 1. LCI Materials Input for Blades *.

|

Input Material |

Standard vCF |

Non-Structural rCF |

Structural rCF |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Weight (kg) |

wt.% |

Weight (kg) |

wt.% |

Weight (kg) |

wt.% |

|

|

vCF |

2140 |

10.7 |

2140 |

15.5 |

0 |

0.0 |

|

rCF |

0 |

0.0 |

2573 |

18.7 |

4713 |

34.2 |

|

Epoxy Resin |

5600 |

28.0 |

5600 |

40.7 |

5600 |

40.7 |

|

GF |

8800 |

44.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

|

PU Resin |

460 |

2.3 |

460 |

3.3 |

460 |

3.3 |

|

PVC Foam |

3000 |

15.0 |

3000 |

21.8 |

3000 |

21.8 |

|

Total Weight |

20,000 |

100 |

13,773 |

100 |

13,773 |

100 |

* Total standard blade weight is adapted from literature [50] where rCF blades are based on equitable composition ratios; CF is significantly lighter than GF, which it is replacing, resulting in the difference in total weight; Material composition ratios based on averages are calculated from available source material [19,44]; values are composition totals after manufacturing wastage.

3. Theory/Calculation Validation and Ethics Statement

Towards industry validation of LCA methodology input data, local wind turbine blade manufacturers and offshore developers were contacted in line with University ethics procedures; whilst interviewees declined explicit identification and confirmation of specific results, anecdotal alignment with proprietary emissions data can be argued.

4. Results and Discussion

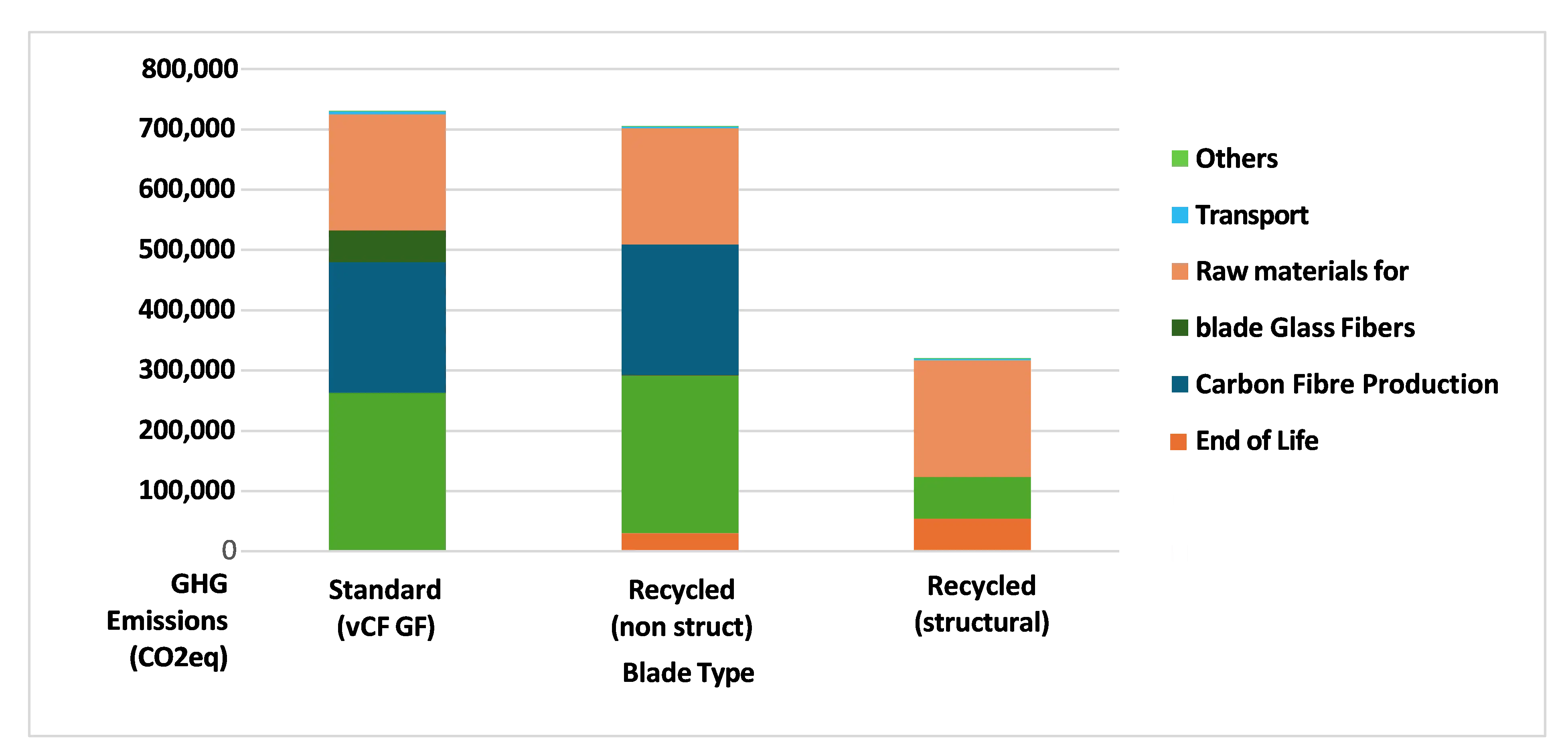

The results for the LCA comparing the GHG emissions of the 3 blade types are shown in Figure 1. The standard vCF blade and non-structural rCF blade exhibit similar total emissions values of 730.9 T CO2eq and 705.9 T CO2eq, respectively, indicating a 3.42% reduction for the rCF blade. The structural rCF blade had emissions of 320.6 T CO2eq, which is a major reduction of 56.14%. The standard and non-structural rCF blade GWP results are similar to those reported in the literature [19]. However, other work does not compare structural rCF blades in the same scenario; in the optimum conditions scenario, a GWP reduction of approximately 26% is noted.

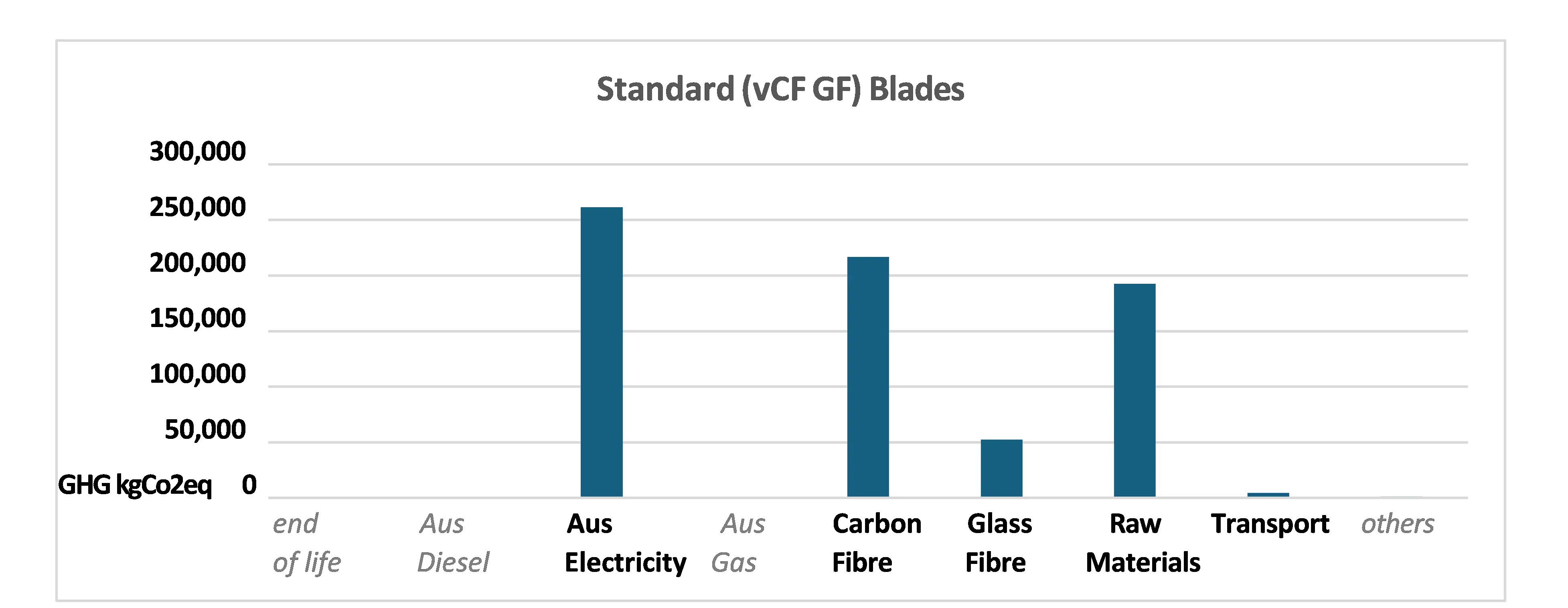

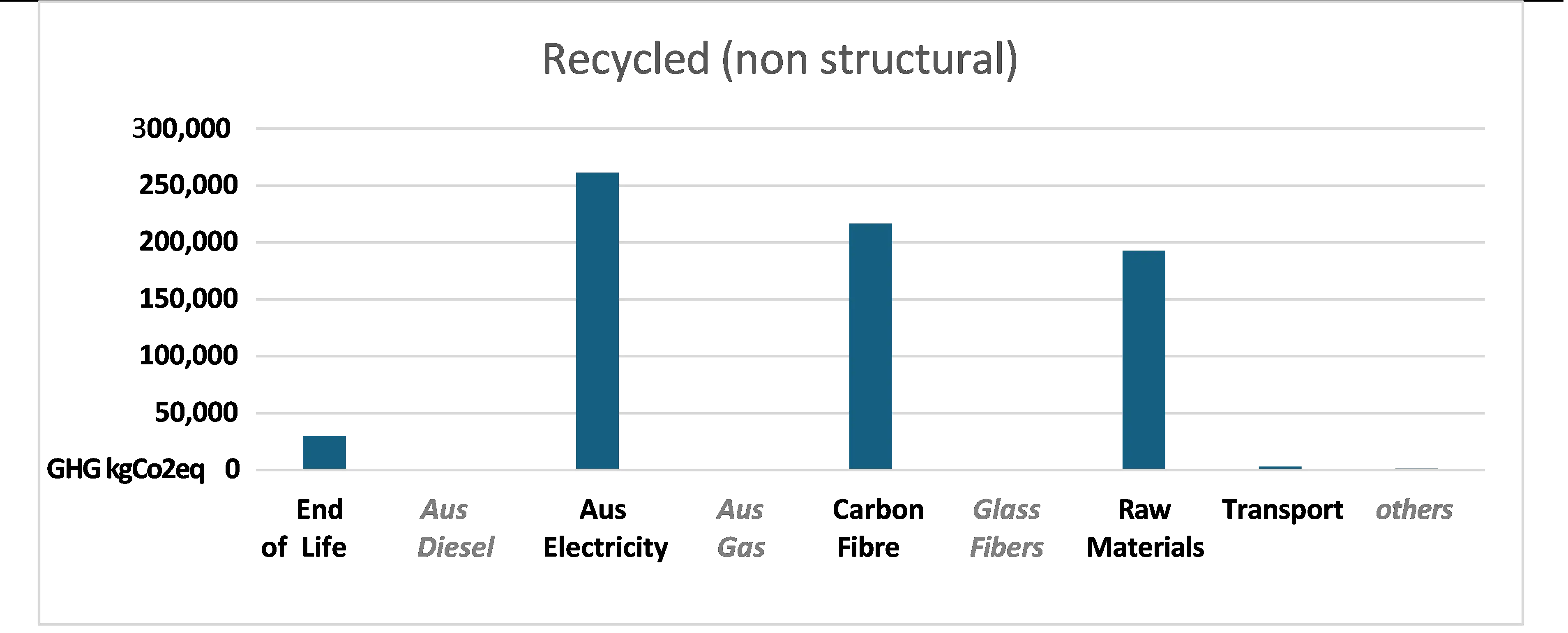

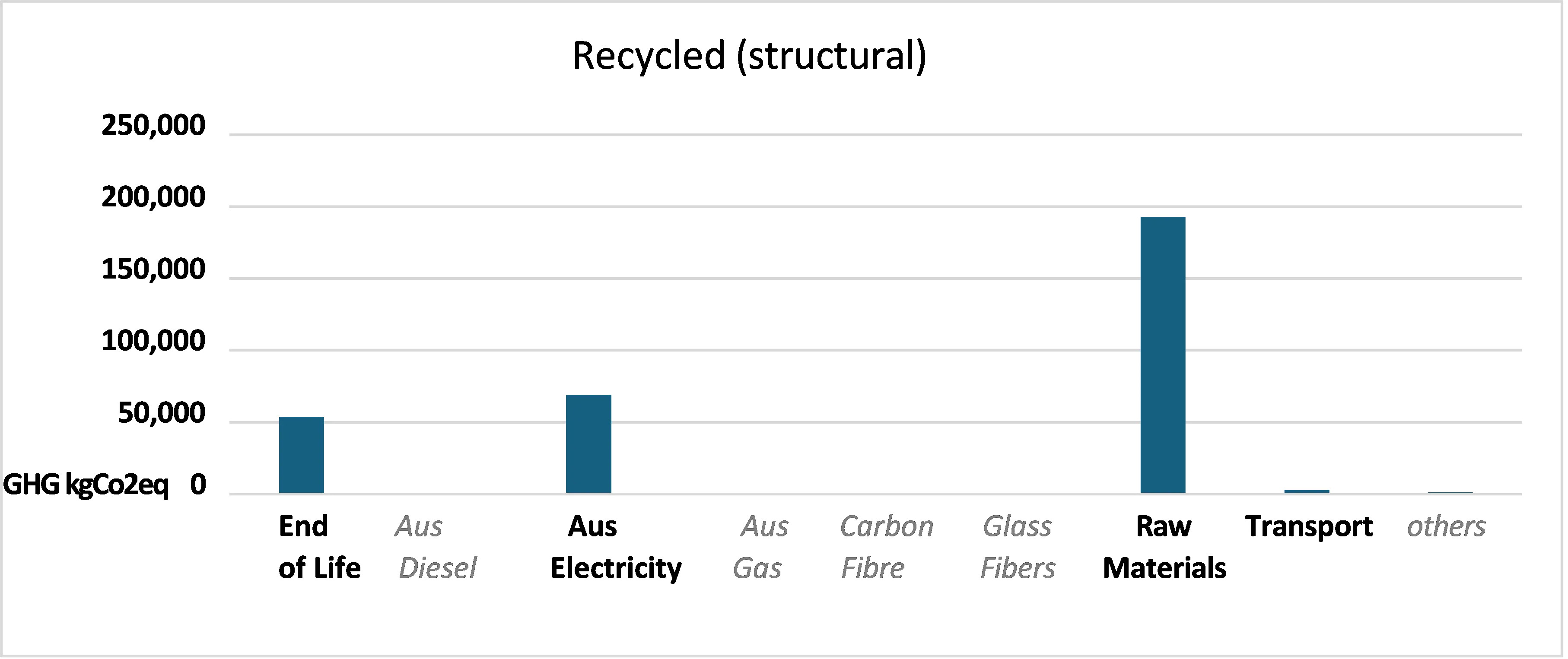

Figure 1. LCA GHG Emissions for the Total Life Cycle for Each Blade Type with Categorical Breakdown.

The difference is due to the vCF being produced in Australia for this study, with a higher GHG impact of the electricity grid compared to CF production and recycling in Europe, where Sweden’s energy grid emissions were 39 g CO2eq per kWh [19], whereas the Australian energy grid emissions used from the GaBi data base was 0.93 kg CO2eq per kWh. Since the structural rCF blade does not use any vCF, this study resulted in a more significant drop in GHG emissions.

Analysing the breakdown of each blade type, the main differences or key impact categories are electricity, CF production, GF production and the end-of-life stages. The raw materials category remains mostly the same, as it excludes any CF processes, and all blades use the same coating, resin, and core.

The majority of electricity consumption is due to the production of vCF, which is an energy intensive procedure, since both standard and non-structural rCF use vCF for the inner structural frame, energy consumption and therefore emissions are the same. The structural rCF blade has a 73.6% reduction in GHG emissions due to electricity, since solvolysis is used for the recycling process, which is mainly a chemical process that requires little electricity. vCF production emissions also remain the same for the first two blade types, as both use equal quantities for the structural frame, compared to the structural rCF, which only uses rCF.

Comparing the end-of-life procedures, both rCF blade types see significant increases in emissions of 36.5× and 65.6× the values of the standard blade, this is mainly due to the standard blade being considered inert landfill waste; if other impact categories were considered, the overall environmental impact of the end-of-life may increase for the standard blade. Although the values’ transportation emission values were not significant, both rCF blades saw a 36% decrease due to the lighter rCF replacing the GF in the standard blade; blade breakdowns are shown in Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5.

Sensitivity analysis, testing the vagaries of high-contribution assumptions’ inputs [47,48], is displayed below (Figure 5), with the best-case scenario showing a 7.25% improvement in emissions for the non-structural blade compared to the standard blade, whereas the worst-case scenario shows a nominal difference (1.2%). Therefore, it can be argued that due to the uncertainty of this model’s input data, there is no emissions reduction value in using rCF for non-structural wind turbine components. For the structural rCF blade, changes in scenario have little effect on emissions; this blade performs better than the standard blade in all scenarios. It is concluded that rCFs are useful if high quality rCF can be obtained for structural use, whereas there is no GHG emissions benefit for rCF use replacing GF, and should not be used.

Figure 5. Sensitivity Analysis: High Impact Parameters of Best/Worst-Case Scenarios in 25% Increments.

Whilst the assessment provides useful insights into the potential environmental benefits of rCF blades, factors that influence the results obtained from this study may be noted, namely: the structural rCF scenario relies on there being excess CF waste available to be recycled from other sources such as aircraft, automative or other wind turbine components; the recycling and production process results in some material loss/wastage, meaning a closed loop life cycle may not be possible. If there is a scenario in which excess CF waste is unavailable for recycling, then vCF will be required in small quantities, increasing the GHG impacts of the structural rCF blade. It is worth noting that the LCA secondary research and the GaBi 2018 database may be less reflective of region-specific manufacturing practices.

Although Australia was used as the region boundary, there is currently limited availability for wind turbine blade manufacture due to uncertainties in labour costs and the fledgling nature of offshore wind farm development in Australia. CF recycling is somewhat limited in Australia. Whilst independent work is noted as ongoing towards circular economy carbon fibre uptake [51,52], there are limited national facilities for industry level production, such that, if this current work’s findings seek application, then recycling will need outsourcing overseas.

This work’s objectives were addressed; an LCA comparison was conducted, whilst the results indicate that non-structural use of rCF does not provide significant GWP reduction in comparison to vCF blades, it is noteworthy that the use of rCF in structural components, in addition to non-structural components, finds a significant reduction in GWP (56.14%). These results are not significantly affected by sensitivity parameters. For use in the Australian wind industry, it is recommended that rCF be further explored to facilitate the replacement of vCF structural components with rCF.

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

Research on lower emission alternative materials is important for a complete transition to renewable energy production. This study aimed to assess and compare the GHG emissions of virgin-carbon-fibre vCF and recycled-carbon-fibre rCF wind turbine blades within an Australian context, using a cradle to grave life cycle assessment. Three blade types were compared, standard CF and GF mix, rCF used only for non-structural components (replacing GF), and rCF used for both structural and non-structural components.

The work herewith notes constraints & limitations related to a lack of propriety WA applications’ information, and that, as a result, inventory inputs are sourced from Sphera databases and available literature for regional conditions.

The results indicate little to no reduction in GHG emissions for the non-structural blades, due predominantly to virgin carbon fibre still being used, with its high impact on emissions. Sensitivity analysis revealed that in certain scenarios, non-structural rCF blades can have higher GHG emissions than their standard vCF counterpart. Structural rCF blades, on the other hand, saw a major reduction in GHG emissions, reducing by 56%. Even when sensitivity analysis is considered, the structural rCF blades do show a significant reduction in GHG emissions, indicating value in using rCF in wind turbine blades; vCF can be replaced for environmental gain.

Whilst this study can be considered a screening or preliminary study, with a full, more detailed study using primary data recommended to validate these preliminary findings, these LCA results do however, show that the use of rCF is superior in reducing GHG emissions, depending on the quantity and replacement of vCF, when compared to standard vCF blades. As Australia moves towards expanding its renewable energy infrastructure, integrating recycled materials such as rCF into offshore wind turbine production will contribute meaningfully to achieving sustainability goals and directing future policies, providing ongoing government motivations, technological, and data challenges are addressed.

There is evidence that using rCF can reduce GHG emissions significantly, depending on the quantity used. It is important to determine the detailed feasibility and a more detailed environmental impact analysis following this work.

Further research is proposed; namely, a more detailed LCA that breaks major processes down into more fundamental components is recommended. Using primary data will obtain more accurate results, especially if collaboration and explicit corroboration with an active, local industry partner can be secured, such that LCA results could be directly applied to specific blade designs that are currently in-use, or nearing the end of life. Although rCF may be a better alternative to vCF in reducing GHG emissions, chemically intensive processes such as solvolysis have an impact on categories such as acidification potential, ecotoxicity and human toxicity, and require more study.

The take-away message from this work is that this study demonstrates that rCF can significantly reduce GHG emissions in the life cycle of offshore wind turbine blades in Australia, and it is recommended that rCF should be explored further for usage in the fledgling Australian offshore wind energy industry.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.W., L.H.; Methodology, L.H., A.W.; Software, L.H.; Validation, L.H.; Formal Analysis, L.H.; Investigation, L.H.; Resources, L.H. & A.W.; Data Curation L.H.; Writing, original draft preparation, L.H.; Writing, review & editing, A.W., L.H.; Visualization A.W. & L.H.; Supervision, A.W.; Project Administration, A.W.; Funding n/a.

Ethics Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines approved by the ethics committee of Curtin University Perth Australia, project HRE2024-0372, 13 March 2025.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

For this original article, accessibility of research data linked to the paper is retained and available in the usual way.

Funding

The authors declare that they received no external funding other than in-kind, institutional facilities’ support.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

-

DCCEEW 2024c—Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment & Water, of the Australian Government. Australia’s Offshore Wind Areas. 6 March 2024. Available online: https://www.dcceew.gov.au/energy/renewable/offshore-wind/areas (accessed on 1 December 2025).

-

DCCEEW 2025—Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment & Water, Australian Government. Net Zero. Jan 2025. Available online: https://www.dcceew.gov.au/climate-change/emissions-reduction/net-zero (accessed on 1 December 2025).

-

Akkawat P, Whyte A, Hasan U. Offshore Wind Turbine Key Components’ Life Cycle Cost Analysis (LCCA): Specification Options in Western Australia. Eng 2025, 6, 118. DOI:10.3390/eng6060118 [Google Scholar]

-

Castellanos I, Whyte A, Urquhart S. Life Cycle Assessment of Semi-Submerged Offshore Wind Turbines Foundation Materials: Concrete versus Steel. In Proceedings of the Eighth International Conference on the Durability of Concrete Structures, SCE06, Edinburgh, UK, 15–17 October 2025. Available online: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1756&context=icdcs (accessed on 1 December 2025).

-

Graham P. GenCost 2024-25; CSIRO: Canberra, Australia, 2024. [Google Scholar]

-

Clean Energy Council. Clean Energy Australia 2024; Clean Energy Council: Melbourne, Australia, 2024. Available online: https://assets.cleanenergycouncil.org.au/documents/resources/reports/clean-energy-australia/Clean-Energy-Australia-2024.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2025).

-

Climate Council. Australia and Offshore Wind; Climate Council: Canbera Australia, 2023. Available online: https://www.climatecouncil.org.au/resources/offshore-wind-fact-sheet/ (accessed on 1 December 2025).

-

Zhang S, Gan J, Lv J, Shen C, Xu C, Li F. Environmental Impacts of Carbon Fiber Production and Decarbonization Performance in Wind Turbine Blades. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 351, 119893. DOI:10.1016/j.jenvman.2023.119893 [Google Scholar]

-

Satoh T. Reducing emissions from the manufacturing of carbon fibers. Chemical Engineering. Nov 1 2019, https://www.chemengonline.com/reducing-emissions-carbon-fiber-manufacturing/ (accessed on 1 December 2025) [Google Scholar]

-

Liu C, Zhao R, Li Q, Yadav R, Ferdowsi MR, Wang Z, et al. Surface Engineering of Carbon Fiber via Upcycling of Waste Gases Generated during Carbon Fiber Production: A Sustainable Approach towards High-Performance Composites. Compos. Part B Eng. 2023, 255, 110624. DOI:10.1016/j.compositesb.2023.110624 [Google Scholar]

-

Prenzel TM, Hohmann A, Prescher T, Angerer K, Wehner D, Ilg R, et al. Bringing Light into the Dark-Overview of Environmental Impacts of Carbon Fiber Production and Potential Levers for Reduction. Polymers 2024, 16, 12. DOI:10.3390/polym16010012 [Google Scholar]

-

Kawajiri K, Kobayashi M. Cradle-to-Gate Life Cycle Assessment of Recycling Processes for Carbon Fibers: A Case Study of Ex-Ante Life Cycle Assessment for Commercially Feasible Pyrolysis and Solvolysis Approaches. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 378, 134581. DOI:10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.134581 [Google Scholar]

-

Kawajiri K, Sakamoto K. Environmental Impact of Carbon Fibers Fabricated by an Innovative Manufacturing Process on Life Cycle Greenhouse Gas Emissions. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 2022, 31, e00365. DOI:10.1016/j.susmat.2021.e00365 [Google Scholar]

-

Liu P, Barlow CY. Wind Turbine Blade Waste in 2050. Waste Manag. 2017, 62, 229–240. DOI:10.1016/j.wasman.2017.02.007 [Google Scholar]

-

Majewski P, Florin N, Jit J, Stewart RA. End-of-Life Policy Considerations for Wind Turbine Blades. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 164, 112538. DOI:10.1016/j.rser.2022.112538 [Google Scholar]

-

Cooperman A, Eberle A, Lantz E. Wind Turbine Blade Material in the United States: Quantities, Costs, and End-of-Life Options. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 168, 105439. DOI:10.1016/j.resconrec.2021.105439 [Google Scholar]

-

Sproul E, Williams M, Rencheck ML, Korey M, Ennis BL. Life Cycle Assessment of Wind Turbine Blade Recycling Approaches in the United States. IOP Conf. Series. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2023, 1293, 012027. DOI:10.1088/1757-899X/1293/1/012027. [Google Scholar]

-

DCCEEW 2024b—Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment & Water, Australian Government. Australia’s Circular Economy Framework. Available online: https://www.dcceew.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/australias-circular-economy-framework.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2025).

-

Upadhyayula VK, Gadhamshetty V, Athanassiadis D, Tysklind M, Meng F, Pan Q, et al. Wind Turbine Blades Using Recycled Carbon Fibers: An Environmental Assessment. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 1267–1277. DOI:10.1021/acs.est.1c05462 [Google Scholar]

-

Eligüzel İM, Özceylan E. A Bibliometric, Social Network and Clustering Analysis for a Comprehensive Review on End-of-Life Wind Turbines. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 380, 135004. DOI:10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.135004 [Google Scholar]

-

Nagle AJ, Delaney EL, Bank LC, Leahy PG. A Comparative Life Cycle Assessment between Landfilling and Co-Processing of Waste from Decommissioned Irish Wind Turbine Blades. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 277, 123321. DOI:10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.123321 [Google Scholar]

-

MIIT China. Law PRC China: Prevention and Control of Environmental Pollution by Solid Waste (Revised 2020). 29 Jan 2022. Available online: https://wap.miit.gov.cn/zwgk/zcwj/flfg/art/2022/art_0c01c26f141a473895d42ead21deed6b.html (accessed on 1 December 2025).

-

Decomblades. DecomBlades Wind Industry Blade Decommissioning. 2025. Available online: https://decomblades.dk/ (accessed on 1 December 2025).

-

DCCEEW 2024a—Department of Climate Change, Engergy, the Environment & Water, Australian Government. 2024 National Waste Policy Action Plan. Available online: https://www.dcceew.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/national-waste-policy-action-plan-2024.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2025).

-

Witik RA, Teuscher R, Michaud V, Ludwig C, Månson JA. Carbon Fibre Reinforced Composite Waste: An Environmental Assessment of Recycling, Energy Recovery and Landfilling. Compos. Part A: Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2013, 49, 89–99. DOI:10.1016/j.compositesa.2013.02.009 [Google Scholar]

-

Song YS, Youn JR, Gutowski TG. Life Cycle Energy Analysis of Fiber- Reinforced Composites. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2009, 40, 1257–1265. DOI:10.1016/j.compositesa.2009.05.020 [Google Scholar]

-

Zhang X, Sibari R, Chakraborty S, Baz S, Gresser GT, Benner W, et al. Epoxy-Based Carbon Fiber-Reinforced Plastics Recycling via Solvolysis with Non-Oxidizing Methanesulfonic Acid. Chem. Ing. Tech. 2024, 96, 987–997. DOI:10.1002/cite.202300243 [Google Scholar]

-

Chin KY, Shiue A, You JL, Wu YJ, Cheng KY, Chang SM, et al. Carbon Fiber Recycling from Waste CFRPs via Microwave Pyrolysis: Gas Emissions Monitoring and Mechanical Properties of Recovered Carbon Fiber’. Fibers 2024, 12, 106. DOI:10.3390/fib12120106 [Google Scholar]

-

Tortorici D, Clemente R, Laurenzi S. Solvolysis Process for Recycling Carbon Fibers from Epoxy-Based Composites. Macromol. Symp. 2024, 413, 2400039. DOI:10.1002/masy.202400039 [Google Scholar]

-

Lebedeva EA, Astaf’eva SA, Istomina TS, Trukhinov DK, Il’inykh GV, Slyusar’ NN. Application of Low-Temperature Solvolysis for Processing of Reinforced Carbon Plastics. Russ. J. Appl. Chem. 2020, 93, 845–853. DOI:10.1134/S1070427220060117 [Google Scholar]

-

Prinçaud M, Aymonier C, Loppinet-Serani A, Perry N, Sonnemann G. Environmental Feasibility of the Recycling of Carbon Fibers from CFRPs by Solvolysis Using Supercritical Water. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2014, 2, 1498–1502. DOI:10.1021/sc500174m [Google Scholar]

-

Khalil YF. Sustainability Assessment of Solvolysis Using Supercritical Fluids for Carbon Fiber Reinforced Polymers Waste Management. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2019, 17, 74–84. DOI:10.1016/j.spc.2018.09.009 [Google Scholar]

-

Karuppannan Gopalraj S, Kärki T. A Review on the Recycling of Waste Carbon Fibre/Glass Fibre-Reinforced Composites: Fibre Recovery, Properties and Life-Cycle Analysis. SN Appl. Sci. 2020, 2, 433. DOI:10.1007/s42452-020-2195-4 [Google Scholar]

-

Mitsubishi Chemical Group. carboNXT® Recycled Carbon Fiber. Wevolver. 2025. Available online: https://www.wevolver.com/specs/carbonxt-recycled-carbon-fiber (accessed on 1 December 2025).

-

Toray. Toray Carbon Fiber Recycled from Boeing 787 Wing Production Process Applied in Lenovo ThinkPad X1 Carbon Gen 12’. TORAY. 14 December 2023. Available online: https://www.toray.com/global/news/article.html?contentId=v1wibzlx (accessed on 1 December 2025).

-

Mclaren. Strap in, Recycled Carbon Fibre Is Just the Start. 19 October 2023. Available online: https://www.mclaren.com/racing/formula-1/2023/united-states-grand-prix/strap-in-recycled-carbon-fibre-is-just-the-start/ (accessed on 1 December 2025).

-

Asahi Kasei. Asahi Kasei Develops Basic Technology for Recycling Continuous Carbon Fiber. 14 December 2022. Available online: https://www.asahi-kasei.com/news/2022/e221214.html (accessed on 1 December 2025).

-

Giant. A Push for Sustainability. Giant Bicycles. 2025. Available online: https://www.giant-bicycles.com/au/recycled-materials (accessed on 1 December 2025).

-

Lee B, Whyte A, Sarker D. Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) of sludge treatment and disposal methods in regional Western Australia. In Lecture Notes in Civil Engineering, 667 LNCE; Springer: Singapore, 2024; pp. 439–450. Available online: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-981-96-7818-1_37 (accessed on 1 December 2025).

-

Hahnel G, Whyte A, Biswas W. A Comparative Life Cycle Assessment of Structural Flooring Systems in Western Australia. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 35, 102109. DOI:10.1016/j.jobe.2020.102109 [Google Scholar]

-

Cao Y, Meng Y, Zhang Z, Yang Q, Li Y, Liu C, et al. Life Cycle Environmental Analysis of Offshore Wind Power: A Case Study of the Large- Scale Offshore Wind Farm in China. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2024, 196, 114351. DOI:10.1016/j.rser.2024.114351 [Google Scholar]

-

Merugula LA, Khanna V, Bakshi BR. Comparative Life Cycle Assessment: Reinforcing Wind Turbine Blades with Carbon Nanofibers. In Proceedings of the 2010 IEEE International Symposium on Sustainable Systems and Technology, Arlington, VA, USA, 17–19 May 2010; pp. 1–6. DOI:10.1109/ISSST.2010.5507724 [Google Scholar]

-

Guilloré A, Canet H, Bottasso CL. Life Cycle Environmental Impact of Wind Turbines: What Are the Possible Improvement Pathways? J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2022, 2265, 042033. DOI:10.1088/1742-6596/2265/4/042033. [Google Scholar]

-

Chiesura G, Stecher H, Jensen JP. Blade Materials Selection Influence on Sustainability: A Case Study through LCA. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 942, 012011. DOI:10.1088/1757-899X/942/1/012011. [Google Scholar]

-

Carallo GA, Casa M, Kelly C, Alsaadi M. Comparative Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) of Traditional and New Sustainable Wind Blade Construction. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2026. DOI:10.3390/su17052026 [Google Scholar]

-

Alavi Z, Khalilpour K, Florin N, Hadigheh A, Hoadley A. End-of-Life Wind Turbine Blade Management across Energy Transition: A Life Cycle Analysis. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2025, 213, 108008. DOI:10.1016/j.resconrec.2024.108008 [Google Scholar]

-

Sphera. Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) Software Solutions. 2023. Available online: https://sphera.com/solutions/product-stewardship/life-cycle-assessment-software-and-data/ (accessed on 1 December 2025).

-

Groen EA, Bokkers EA, Heijungs R, de Boer IJ. Methods for Global Sensitivity Analysis in Life Cycle Assessment. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2017, 22, 1125–1137. DOI:10.1007/s11367-016-1217-3 [Google Scholar]

-

Almusharraf A, Whyte A. Sensitivity of sub-task requirements towards quality deviations and construction defects. In Implementing Innovative Ideas in Structural Engineering & Project Management, Proceedings of the ISEC-8 Conference Proceedings Reprints, Sydney, Australia, 23–28 November 2015; Saha S, Zhang Y, Yazdani S, Singh A, Eds.; pp. A51–A56, ISBN: 978-0-9960437-1-7. Available online: https://www.isec-society.org/ISEC_PRESS/ISEC_08/index.html (accessed on 1 December 2025).

-

Ramos Júnior MJ, Medeiros DL, Almeida ED. Blade Manufacturing for Onshore and Offshore Wind Farms: The Energy and Environmental Performance for a Case Study in Brazil. Gestão Produção 2023, 30, e12122. Doi:10.1590/1806-9649-2022v29e12122 [Google Scholar]

-

White B. Gen 2 Carbon Forms Strategic Partnership with Deakin University to Lead Multimillion Recycling Initiative 19th May 2022. Gen 2 Carbon (Blog). 19 May 2022. Available online: https://www.gen2carbon.com/gen-2-carbon-forms-strategic-partnership-with-deakin- university-to-lead-multimillion-recycling-initiative/ (accessed on 1 December 2025).

-

Williams E. Carbon Copy: New Method of Recycling Carbon Fibre Shows Huge Potential. UNSW. 24 October 2023. Available online: https://www.unsw.edu.au/news/2023/10/carbon-copy--new-method-of-recycling-carbon-fibre-shows-huge-pot (accessed on 1 December 2025).