Extracellular Vesicles from Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma Carry OGT/OGA with Possible Implications in Tumor O-GlcNAcylation

Received: 19 October 2025 Revised: 09 December 2025 Accepted: 22 December 2025 Published: 26 December 2025

© 2025 The authors. This is an open access article under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

1. Introduction

Oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) is the most common malignant tumor of the oral mucosa, accounting for nearly 90% of neoplasms that develop in this region [1]. It is characterized by high aggressiveness, frequent recurrence, and poor prognosis, with a global five-year survival rate below 50% [2,3]. In Latin America, particularly in Mexico, OSCC constitutes a major public health problem due to late diagnosis and the lack of reliable biomarkers that enable early detection [4,5].

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) are lipid bilayer structures released by virtually all cell types. They act as mediators of intercellular communication by transporting proteins, nucleic acids, and lipids to neighboring or distant cells [6,7]. In the context of cancer, EVs have been shown to facilitate key processes such as invasion, angiogenesis, metastasis, and immune evasion [8,9]. In OSCC, recent studies have demonstrated that tumor-derived EVs can reprogram the metabolism of normal oral fibroblasts toward a pro-tumoral phenotype [10]. That elevated plasma levels of exosomes are associated with postoperative recurrence, supporting their potential as prognostic biomarkers [11].

O-GlcNAcylation is a dynamic and reversible post-translational modification in which an N-acetylglucosamine residue is added to nuclear, cytoplasmic, or mitochondrial proteins. This modification is exclusively catalyzed by two enzymes: O-GlcNAc transferase (OGT) and O-GlcNAcase (OGA) [12]. Both enzymes regulate multiple cellular processes, including signaling, transcription, and metabolism [13,14]. Dysregulation of O-GlcNAc homeostasis has been linked to tumor growth, invasion, therapeutic resistance, and metabolic reprogramming [15,16]. In OSCC, regulatory genes such as GALNT6 have been reported to contribute to tumor progression by increasing O-GlcNAcylation levels [17].

Recent evidence in other cancer types has expanded the understanding of the relationship between O-GlcNAcylation and extracellular vesicles. In triple-negative breast cancer, adipocyte-derived exosomes were shown to transport circCRIM1, which activates the OGA/FBP1 pathway, promoting tumor glycolysis and metastasis [18]. Similarly, in colorectal cancer, OGT overexpression increased the O-GlcNAc burden in proteins and, through tumor-derived exosomes, promoted macrophage polarization toward an immunosuppressive M2 phenotype, thereby contributing to a pro-tumoral microenvironment [19]. These findings reinforce the hypothesis that EVs not only transport classical regulatory molecules but also carry enzymes capable of directly modifying post-translational processes in recipient cells.

Despite these advances, the association of OGT and OGA with extracellular vesicles in the context of OSCC has not yet been explored. This study aimed to characterize the presence of both enzymes in EVs derived from tumor cell lines (SCC-152 and SCC-25) and to compare them with non-tumoral keratinocytes (HaCaT). Based on current evidence indicating that EVs can transfer functional proteins capable of modulating signaling and metabolic pathways in recipient cells, we hypothesized that OGT and OGA are selectively incorporated into OSCC-derived EVs and may participate in the modulation of the tumor microenvironment through alterations in O-GlcNAcylation dynamics. In this context, the present study focuses on the identification and comparative analysis of OGT and OGA as EV-associated proteins, providing an initial framework for exploring their potential relevance in OSCC. While functional enzymatic activity was not directly assessed, the detection of these enzymes within EVs cargo represents a necessary first step toward future functional characterization. Our results demonstrate that OGT and OGA are present in the vesicular cargo, with significant differences between tumor and non-tumor cell lines, suggesting that these enzymes may serve as vesicular biomarkers and potential mediators of OSCC progression.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Lines and Culture Conditions

Human oral squamous cell carcinoma cell lines SCC-152 (ATCC CRL-3240) and SCC-25 (ATCC CRL-1628), as well as the immortalized human keratinocyte line HaCaT (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), were cultured under standard conditions at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2.

SCC-152 cells were maintained in Minimum Essential Medium Alpha (MEM; Caisson Laboratories, Smithfield, ID, USA. Lot: 10161019) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (extracellular vesicle–depleted FBS; Biowest, Nuaillé, France. S1094351650), 100 U/mL penicillin, and 10 µg/mL streptomycin (Sigma-Aldrich, Burlington, MA, USA. P4333). SCC-25 cells were cultured in low-calcium Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% extracellular vesicle–depleted FBS, 100 U/mL penicillin, 10 µg/mL streptomycin, and 1 µg/mL hydrocortisone. HaCaT cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium/Ham’s F12 (DMEM/F12) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (v/v), 100 U/mL penicillin, 10 µg/mL streptomycin, 2 mM L-glutamine, and 1 mM sodium pyruvate.

Cells were seeded in 25 cm2 or 75 cm2 culture flasks (Corning Inc., Corning, NY, USA. 3055) and observed under an inverted phase-contrast microscope (ZEISS, Oberkochen, Germany) using 5×, 20×, and 40× objectives. Culture media were replaced every third day to remove non-adherent cells and collect the supernatant for isolation of extracellular vesicles (EVs). When cell confluence reached 80–90%, cultures were washed with Ca2+/Mg2+-free PBS, treated with 0.05% trypsin-EDTA (Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) for 5 min, and subsequently subcultured or cryopreserved for further experiments.

2.2. Extracellular Vesicle Isolation

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) were isolated from conditioned media of SCC-152, SCC-25, and HaCaT cell lines cultured in EVs-depleted fetal bovine serum. Briefly, cell culture supernatants were collected and subjected to sequential centrifugation steps to remove cells and cellular debris. Supernatants were first centrifuged at 300× g for 10 min, followed by 2000× g for 20 min and 10,000× g for 30 min at 4 °C. The resulting supernatant was subsequently filtered through a 0.22 μm pore-size filter and then ultracentrifuged at 100,000× g for 70 min at 4 °C. The EVs pellet was washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and ultracentrifuged again at 100,000× g for 70 min. Final EVs pellets were resuspended in PBS and stored at −80 °C until further analysis.

Although nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA) or dynamic light scattering (DLS) was not performed to determine particle size distribution and concentration, EVs identity was confirmed by transmission electron microscopy and by the detection of canonical EVs markers.

2.3. Extracellular Vesicle Characterization

The identity of extracellular vesicles (EVs) was verified by Western blot detection of the markers CD63 and TSG101, and by transmission electron microscopy (TEM). Protein concentrations were determined using the BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Equal amounts of protein (30 µg per lane) were loaded, separated by SDS-PAGE, and transferred onto PVDF membranes (MilliporeSigma, Burlington, MA, USA). Membranes were incubated with primary antibodies used for Western blot and immunocytochemistry included anti-O-GlcNAcase (OGA; NCOAT-H300, rabbit polyclonal; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA), anti-O-GlcNAc transferase (OGT; TI14, rabbit polyclonal; Abcam, Cambridge, UK), anti-CD63 (mouse monoclonal; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA), anti-TSG101 (mouse monoclonal; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA), and anti-β-actin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). Secondary antibodies included HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Abcam, ab6721, Cambridge, UK) and HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (Abcam, ab6789, Cambridge, UK), both used at a dilution of 1:5000 for Western blot detection.

For immunocytochemistry, Alexa Fluor–conjugated secondary antibodies (Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-rabbit IgG and Alexa Fluor 594 goat anti-mouse IgG; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) were used according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) was quantified on a per-cell basis using software Fiji (ImageJ 20250529-2217), from fluorescence micrographs acquired under identical imaging conditions for each marker.

For TEM analysis, EVs samples were placed on carbon-coated grids, incubated for one-minute, excess sample was removed, and grids were negatively stained with 1% phosphotungstic acid for 1 min. After removing the excess stain, grids were air-dried at room temperature and examined under a JEOL JEM transmission electron microscope.

2.4. Immunocytochemistry

SCC-152, SCC-25, and HaCaT cells were seeded onto Nunc® Lab-Tek® Chamber SlideTM systems (C7182), fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100, and blocked with 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA). Primary antibodies against OGT (TI14, Abcam), OGA (NCOAT-H300, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and CD63 (H-193, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) were incubated overnight at 4 °C. For visualization, Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:1000, Thermo Fisher Scientific) were used, and nuclei were counterstained with DAPI. Images were acquired using a Leica fluorescence microscope.

Mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) was quantified on a per-cell basis using ImageJ/Fiji software (National Institutes of Health), from fluorescence micrographs acquired under identical imaging conditions for each marker.

2.5. Detection of OGT and OGA in Extracellular Vesicles

The presence of OGT and OGA in extracellular vesicles (EVs) was evaluated by Western blot following the protocol described above. Anti-OGT (1:1000) and anti-OGA (1:1000) antibodies were used. β-actin (1:5000, Sigma-Aldrich, Burlington, MA, USA) was included as a loading control. For densitometric analyses, Western blot signals were detected by chemiluminescence, immunoblot images corresponding to each target protein were acquired using identical exposure settings across the compared samples, and signals were collected within the linear range of detection to ensure quantitative comparability. Densitometric quantification was performed using ImageJ/Fiji software.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

All experiments were independently performed in triplicate using three independent biological replicates (n = 3). Data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism 8.0 software (GraphPad Software, Boston, MA, USA). One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test was applied for group comparisons. Data are presented as the mean ± SD from three independent experiments. Statistical significance was indicated as p < 0.05 (*) and p < 0.01 (**).

Given the exploratory nature of the study and its in vitro design, parametric statistical tests were applied to compare experimental groups, as data were obtained under controlled conditions and expressed as mean ± standard deviation.

2.7. Ethical and Biosafety Considerations

This study was conducted exclusively using established human cell lines and did not involve human participants or animal subjects. All experimental procedures were performed in accordance with institutional biosafety guidelines.

3. Results

3.1. Characterization of Extracellular Vesicles

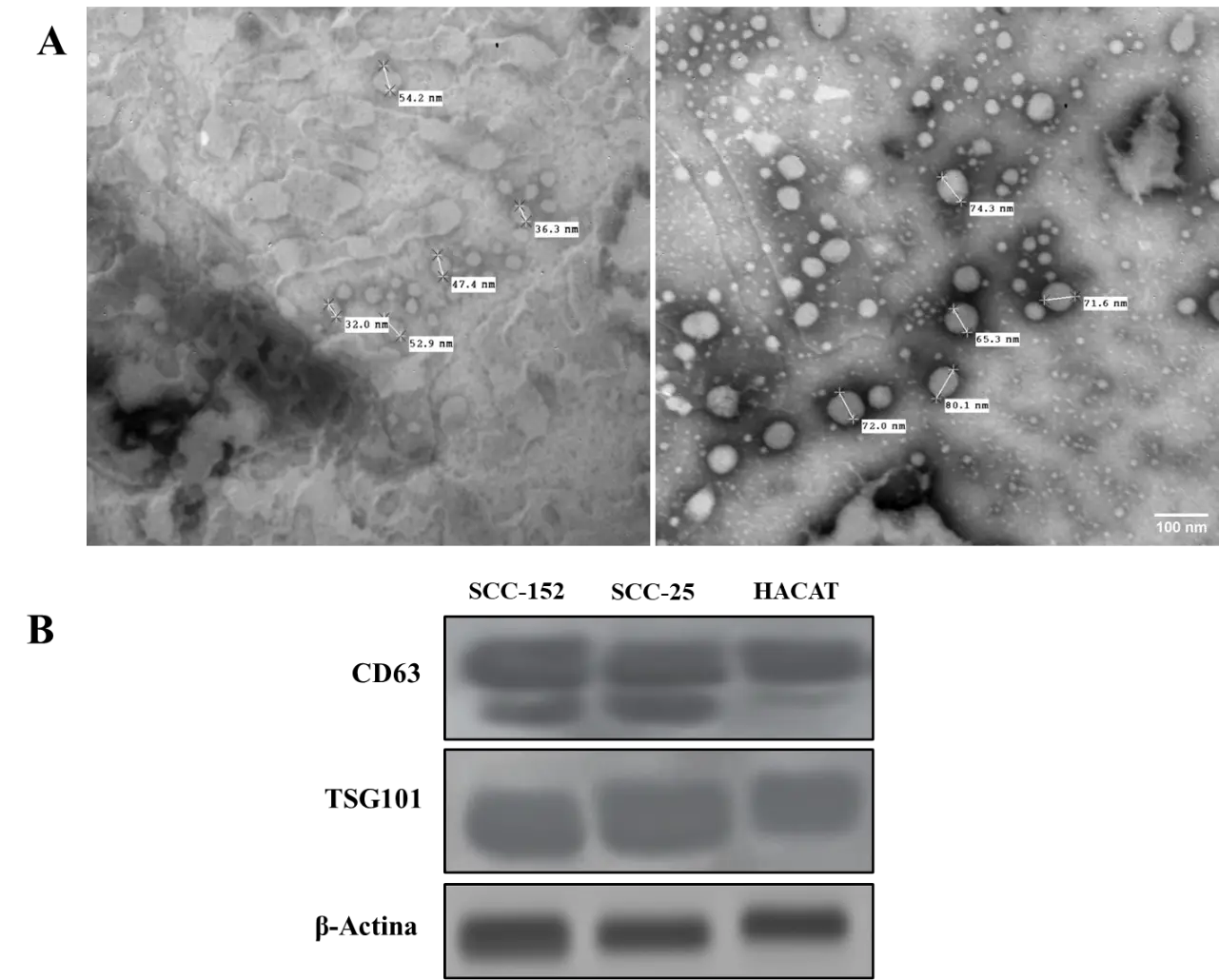

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) were successfully isolated from the culture supernatants of SCC-152, SCC-25, and HaCaT cell lines by differential centrifugation. Morphological characterization by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) confirmed the presence of cup-shaped vesicular particles with an average diameter ranging from 50 to 150 nm in EVs derived from SCC-152 and SCC-25 as estimated from representative TEM images (Figure 1A). The identity of EVs was verified by Western blot, showing the expression of the vesicular markers CD63 and TSG101 in fractions obtained from all three cell lines at the expected molecular weights (Figure 1B). These results confirm that the isolated particles meet the morphological and molecular criteria established by the MISEV2018 guidelines for extracellular vesicle identification.

Figure 1. Characterization of extracellular vesicles isolated from oral squamous cell carcinoma and non-tumoral keratinocyte cell lines. (A) Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images showing the typical cup-shaped morphology of extracellular vesicles isolated from SCC-152, SCC-25, and HaCaT cell lines. (B) Western blot analysis of EV-associated markers CD63 and TSG101 in extracellular vesicle preparations from the indicated cell lines.

3.2. Detection and Relative Expression of OGT and OGA Enzymes in Cell Lines

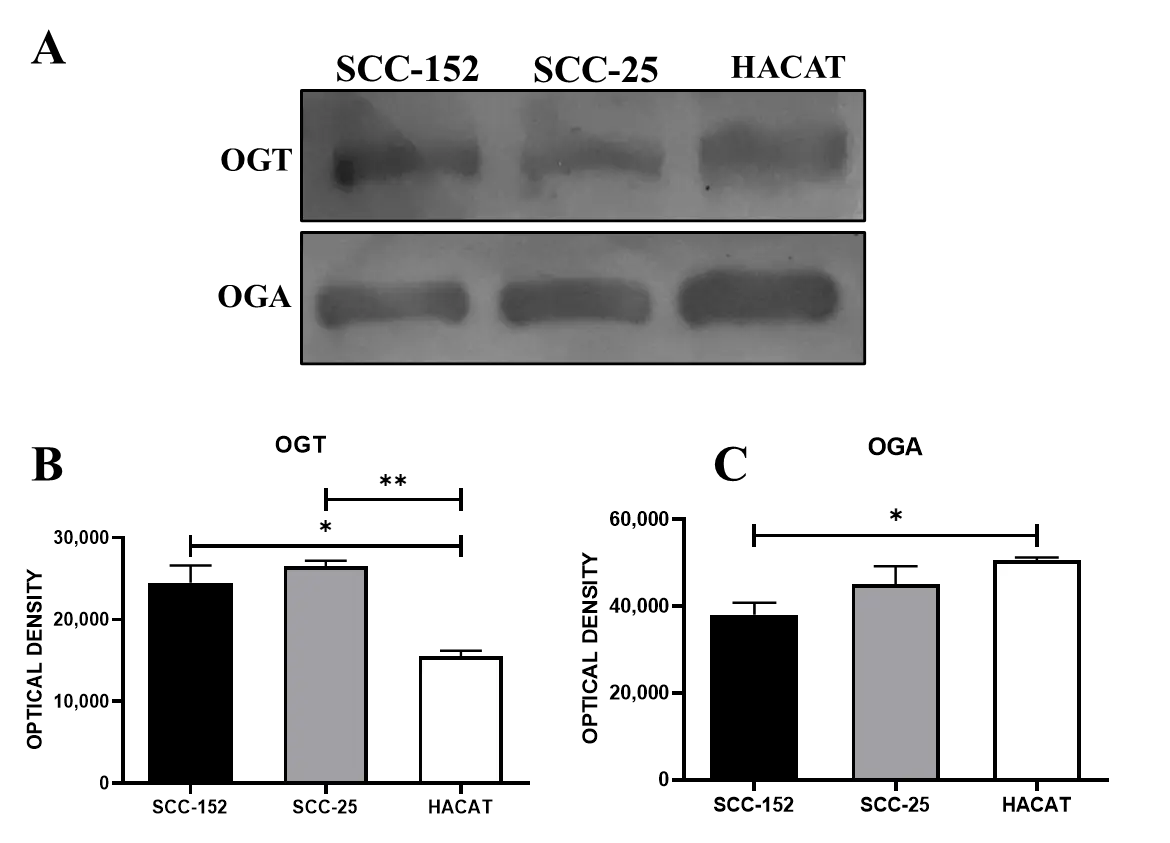

The enzymes O-GlcNAc transferase (OGT) and O-GlcNAcase (OGA) were detected by immunoblot in protein extracts from SCC-152, SCC-25, and HaCaT cell lines (Figure 2A). Densitometric analysis demonstrated differential expression of both enzymes among the evaluated cell lines (Figure 2B,C). OGA showed a consistently higher relative signal compared with OGT across all cell lines, with the highest levels observed in the non-tumoral HaCaT cells. These differences were statistically significant (OGT, p = 0.006; OGA, p = 0.035). Together, these results indicate a relative predominance of the OGA signal within the experimental system, rather than an absolute quantitative comparison of OGA and OGT protein abundance, which may reflect differences in the regulation of the O-GlcNAcylation cycle in the tumor context of oral squamous cell carcinoma.

Figure 2. Representative immunoblot showing the detection of OGT and OGA enzymes in oral squamous cell carcinoma and non-tumoral keratinocyte cell lines. (A) Immunoblot of OGT and OGA in SCC-152, SCC-25, and HaCaT cell lines. (B) Densitometric analysis of OGT relative expression. (C) Densitometric analysis of OGA relative expression. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA (OGT: α = 0.05, ** p = 0.006; OGA: α = 0.05, * p = 0.035), followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test (95% CI). Data represent mean ± standard deviation (n = 3, independent experiments).

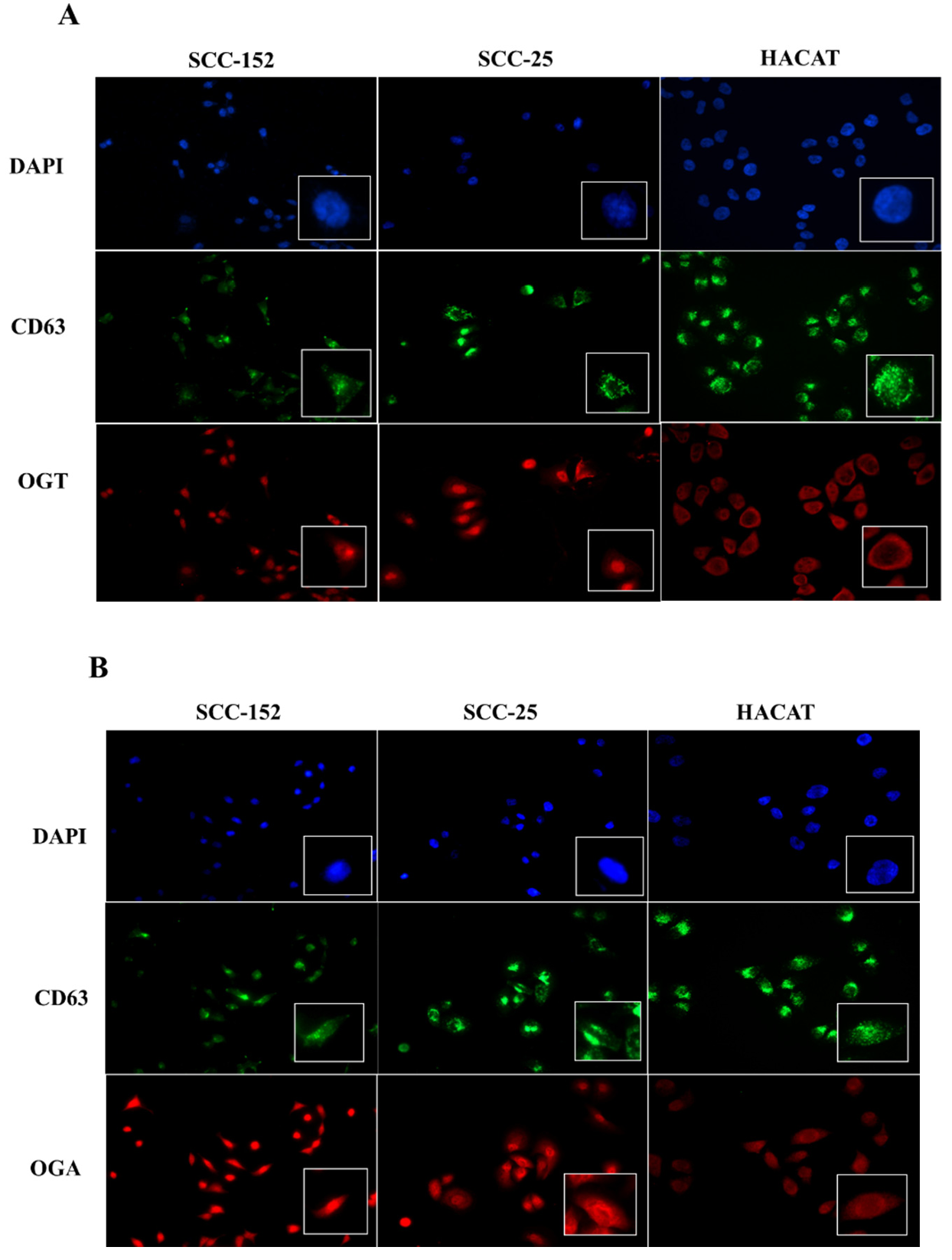

3.3. Subcellular Localization of OGT and OGA in Tumoral and Non-Tumoral Cell Lines

Immunocytochemical analysis showed the expression of the enzymes O-GlcNAc transferase (OGT) and O-GlcNAcase (OGA) in all three analyzed cell lines: SCC-152, SCC-25, and HaCaT (Figure 3). Both enzymes exhibited cytoplasmic and perinuclear localization under all evaluated conditions, as assessed by immunofluorescence microscopy. In parallel, detection of the vesicular marker CD63 (green) confirmed its expression in the three cell lines, displaying a cytoplasmic distribution pattern consistent with endosomal compartments. These findings support the involvement of O-GlcNAcylation enzymes in cellular mechanisms related to the processing and release of extracellular vesicles.

3.4. Comparison of the Mean Fluorescence Intensity of OGT and OGA

Immunocytochemical analysis revealed the presence of O-GlcNAc transferase (OGT) and O-GlcNAcase (OGA) in SCC-152, SCC-25, and HaCaT cell lines, showing a predominantly cytoplasmic and perinuclear localization pattern. Representative immunofluorescence images illustrate OGT distribution in the analyzed cell lines (Figure 3A), while OGA localization is shown in Figure 3B.

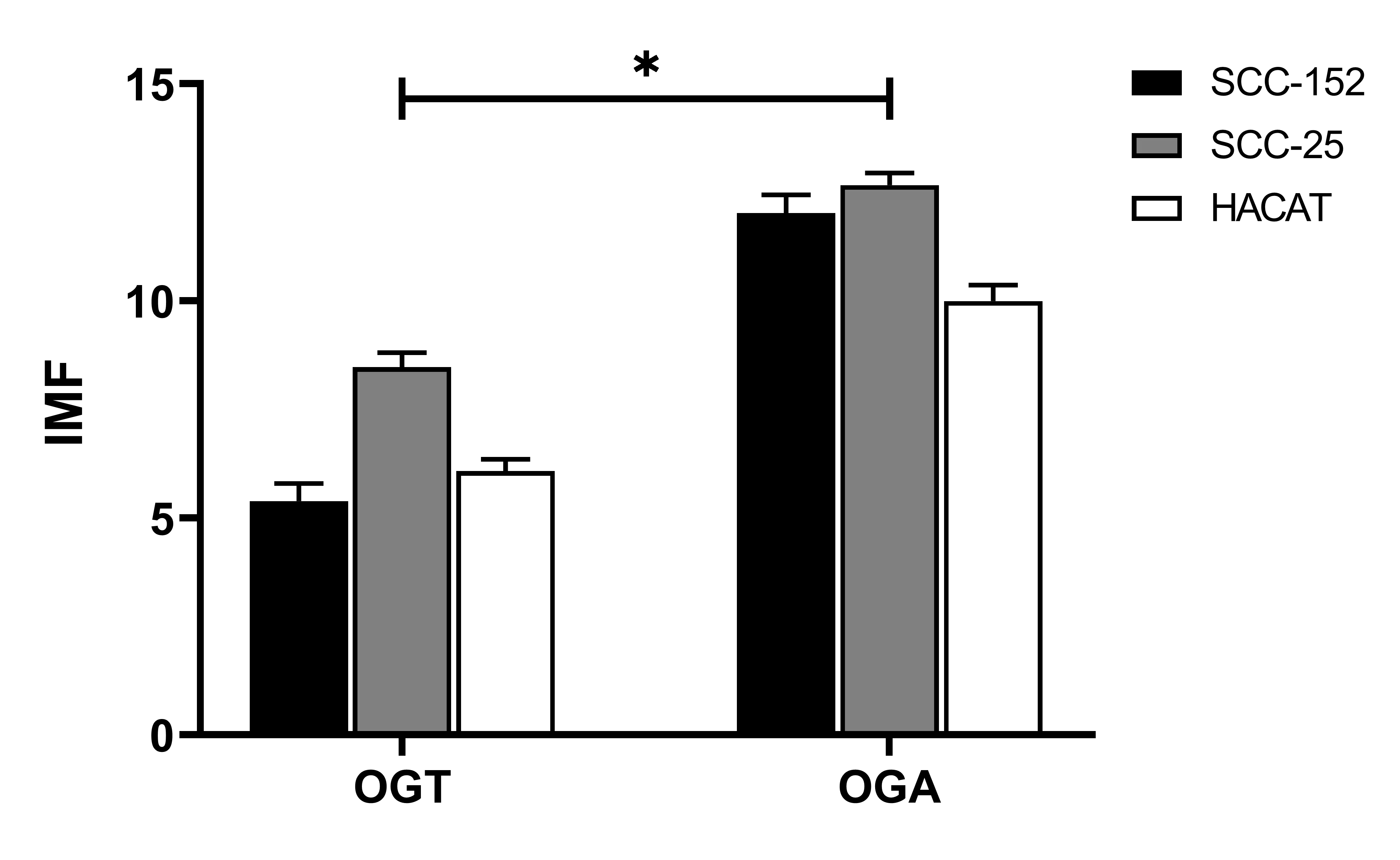

Analysis of the mean fluorescence intensity of OGT and OGA in SCC-152, SCC-25, and HaCaT cell lines showed that the fluorescence signal corresponding to OGA was higher in relative terms than that of OGT (p = 0.03), with fluorescence values quantified on a per-cell basis, indicating a higher relative fluorescence signal of this enzyme across all evaluated cell lines (Figure 4). In addition, both enzymes displayed higher relative fluorescence signals in the tumor cell lines SCC-152 and SCC-25 compared with the non-tumoral HaCaT keratinocytes.

The obtained values, expressed as the mean ± standard deviation from three independent experiments, were consistent with the relative signal trends observed in the Western blot analysis. Together, these findings indicate a relative predominance of the OGA signal compared with OGT, rather than an absolute quantitative difference, in cellular processes associated with the O-GlcNAcylation pathway in oral squamous cell carcinoma under the experimental conditions evaluated.

Figure 3. Immunocytochemical detection of OGT and OGA in oral squamous cell carcinoma and non-tumoral keratinocyte cell lines. (A) Detection of OGT (red) and the vesicular marker CD63 (green) in SCC-152, SCC-25, and HaCaT cell lines. (B) Detection of OGA (red) and CD63 (green) in the same cell lines. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue). Under all conditions, both enzymes and CD63 showed cytoplasmic and perinuclear localization.

Figure 4. Comparison of the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of OGT and OGA enzymes in oral squamous cell carcinoma and non-tumoral keratinocyte cell lines. MFI was determined in SCC-152, SCC-25, and HaCaT cell lines. Under all evaluated conditions, the fluorescence signal for OGA was higher relative to OGT, and both enzymes showed higher relative fluorescence signals in the tumor cell lines SCC-152 and SCC-25 compared with HaCaT. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) from three independent experiments. Statistical analysis was performed using two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. Significant differences were indicated as p < 0.05 (*).

4. Discussion

Oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) represents one of the most aggressive epithelial tumors of the oral cavity, associated with high mortality and recurrence rates [1,2,3]. Understanding the molecular mechanisms that drive its progression and invasive capacity remains a major challenge in biomedical research. In this context, extracellular vesicles (EVs) have emerged as key mediators of intercellular communication, playing a critical role in remodeling the tumor microenvironment and disseminating oncogenic signals [6,7,8,9].

In this study, EVs derived from tumoral (SCC-152 and SCC-25) and non-tumoral (HaCaT) cell lines were isolated and met the morphological and molecular criteria proposed by the MISEV2018 guidelines [20]. The presence of the vesicular markers CD63 and TSG101, along with the typical cup-shaped morphology observed by transmission electron microscopy, supports the proper identification of the isolated EVs for exploratory in vitro analyses.

The detection of O-GlcNAc transferase (OGT) and O-GlcNAcase (OGA) in the analyzed cell lines provides evidence for the involvement of the O-GlcNAcylation process in the tumor context of OSCC [9,10,17]. Both enzymes exhibited cytoplasmic and perinuclear localization. Regarding the vesicular marker CD63, its cytoplasmic distribution suggests a possible association with endosomal compartments and the biogenesis of extracellular vesicles [6]. The identification of OGT and OGA within the vesicular cargo is consistent with recent observations in other cancer types, where EVs have been shown to transport components of the O-GlcNAcylation machinery [16,18,19]. In this context, EVs-associated OGT and OGA could potentially influence recipient cells by modulating the dynamic balance of protein O-GlcNAcylation, thereby affecting signaling pathways, metabolic regulation, or cellular responses within the tumor microenvironment.

In particular, Li et al. (2023) demonstrated that adipocyte-derived exosomes promote the progression of triple-negative breast cancer through OGA-dependent activation, highlighting its role in metabolic regulation and metastasis [18]. Complementarily, Wang et al. (2025) reported that OGT overexpression in colorectal cancer promotes macrophage polarization toward an immunosuppressive M2 phenotype through tumor-derived exosomes, thereby demonstrating the immunomodulatory function of these enzymes [19]. These observations, together with the results of the present study, suggest that OSCC-derived EVs may participate in intercellular communication mechanisms that modulate tumor responses and microenvironmental homeostasis.

Moreover, the higher relative signal of OGA compared with OGT in all analyzed cell lines may indicate a shift in the dynamic regulation of the O-GlcNAcylation cycle, rather than simple enhancement of protein deglycosylation. Such imbalance has been associated with tumor progression, metabolic adaptation, and cellular stress responses in cancer [13,14,15,16]. This difference in OGA abundance could have implications for the dynamic modification of key proteins involved in signaling, proliferation, and immune responses.

In parallel, alternative explanations for the relative predominance of OGA within EVs should be considered. EV composition is increasingly recognized as the result of selective, regulated cargo-loading processes rather than a passive reflection of intracellular protein abundance [6,21]. Accordingly, OGA enrichment in EVs may reflect preferential vesicular sorting mechanisms. In addition, differences in intracellular expression levels, protein stability, or turnover between OGA and OGT could influence their relative availability for EV incorporation [12,16].

The use of distinct antibodies for immunoblot detection constrains direct comparison of OGT and OGA protein abundance. Therefore, the differences observed in this study reflect relative expression patterns within the experimental system rather than absolute quantitative measurements. Approaches enabling absolute protein quantification, including the use of purified standards or mass spectrometry–based analyses, will be required to define differences in OGT and OGA abundance precisely.

Despite these findings, several limitations should be acknowledged. This study was conducted exclusively using in vitro cell line models, and functional assays were not performed to directly assess the biological activity of EVs-associated OGT and OGA in recipient cells. In addition, EVs characterization focused on morphology and marker expression, without quantitative assessment of particle size distribution or concentration. Finally, the limited sample size reflects the exploratory nature of this work.

Taken together, the results indicate that extracellular vesicles derived from oral squamous cell carcinoma carry components of the O-GlcNAcylation process, represented by the enzymes OGT and OGA. Their presence and differential expression between tumoral and non-tumoral cell lines suggest a potential role in modulating the tumor microenvironment and intercellular communication. Further investigation will be required to determine whether EVs-associated OGT and OGA retain enzymatic activity, whether their activity differs from that observed in parental cells, and how pharmacological modulation of extracellular vesicle biogenesis or release may influence their incorporation into EVs. Such approaches will be essential to define the functional and translational relevance of EVs-associated OGT and OGA as candidate biomarkers or therapeutic targets in OSCC.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates, for the first time, the presence of the enzymes O-GlcNAc transferase (OGT) and O-GlcNAcase (OGA) in extracellular vesicles derived from oral squamous cell carcinoma cell lines. Both enzymes were detected in EVs from tumoral and non-tumoral lines, with a higher relative signal observed in EVs derived from SCC-152 and SCC-25 cells. These results suggest that extracellular vesicles may contribute to tumor microenvironment modulation through the transfer of enzymatic components associated with the O-GlcNAcylation machinery. While these findings are based on in vitro models, they lay the groundwork for future investigations aimed at elucidating the functional role of EVs-associated OGT and OGA in tumor communication and their potential translational value as candidate biomarkers or therapeutic targets in OSCC. Overall, these findings provide an initial conceptual framework for future functional and translational studies.

Statement of the Use of Generative AI and AI-Assisted Technologies in the Writing Process

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT solely to improve language clarity, coherence, and readability of certain sections of the text. After using this tool, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the published article.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Escuela Nacional de Ciencias Biológicas, Instituto Politécnico Nacional, Mexico, for its support and research facilities.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.C.C.-S. and M.C.-C.; Formal Analysis, D.S.C.-H. and M.C.-C.; Resources, M.C.-C. and D.S.C.-H.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, M.C.C.-S.; Writing—Review & Editing, D.S.C.-H. and M.C.-C.; Visualization, M.C.-C. and D.S.C.-H.

Ethics Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Scully C, Bagan JV. Oral squamous cell carcinoma: Overview of current understanding of aetiopathogenesis and clinical implications. Oral Dis. 2009, 15, 388–399. doi:10.1111/j.1601-0825.2009.01563.x. [Google Scholar]

- Rivera C, Venegas B. Histological and molecular aspects of oral squamous cell carcinoma. Oncol. Lett. 2014, 8, 7–11. doi:10.3892/ol.2014.2103. [Google Scholar]

- Mascitti M, Orsini G, Tosco V, Monterubbianesi R, Balercia A, Putignano A, et al. An overview on current non-invasive diagnostic devices in oral oncology. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 1510. doi:10.3389/fphys.2018.01510. [Google Scholar]

- García-García V, Bascones A. Cáncer oral: Puesta al día. Av. Odontoestomatol. 2009, 25, 239–248. doi:10.4321/S0213-12852009000500002. [Google Scholar]

- Global Cancer Observatory. GLOBOCAN 2025. IARC. Available online: https://gco.iarc.who.int/overtime/en (accessed on 21 August 2025). [Google Scholar]

- Raposo G, Stoorvogel W. Extracellular vesicles: Exosomes, microvesicles, and friends. J. Cell Biol. 2013, 200, 373–383. doi:10.1083/jcb.201211138. [Google Scholar]

- Yáñez‐Mó M, Siljander PR, Andreu Z, Bedina Zavec A, Borràs FE, Buzas EI, et al. Biological properties of extracellular vesicles and their physiological functions. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2015, 4, 27066. doi:10.3402/jev.v4.27066. [Google Scholar]

- Théry C. Exosomes: Secreted vesicles and intercellular communications. F1000 Biol. Rep. 2011, 3, 15. doi:10.3410/B3-15. [Google Scholar]

- Momen-Heravi F, Bala S. Extracellular vesicles in oral squamous carcinoma carry oncogenic miRNA profile and reprogram monocytes via NF-κB pathway. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 34838–34854. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.26208. [Google Scholar]

- Lipka A, Søland TM, Nieminen AI, Sapkota D, Haug TM, Galtung HK. The effect of extracellular vesicles derived from oral squamous cell carcinoma on the metabolic profile of oral fibroblasts. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2025, 12, 1492282. doi:10.3389/fmolb.2025.1492282. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Zorrilla S, Lorenzo-Pouso AI, Fais S, Logozzi MA, Mizzoni D, Di Raimo R, et al. Increased plasmatic levels of exosomes are significantly related to relapse rate in patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma: A cohort study. Cancers 2023, 15, 5693. doi:10.3390/cancers15235693. [Google Scholar]

- Hart GW, Slawson C, Ramirez-Correa G, Lagerlöf O. Cross talk between O-GlcNAcylation and phosphorylation: Roles in signaling, transcription, and chronic disease. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2011, 80, 825–858. doi:10.1146/annurev-biochem-060608-102511. [Google Scholar]

- Jóźwiak P, Forma E, Bryś M, Krześlak A. O-GlcNAcylation and metabolic reprograming in cancer. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2014;5:145. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2014.00145. [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Wang J, Xiang Y, Wang K, Yan D, Tong Y. The roles of OGT and its mechanisms in cancer. Cell Biosci. 2024, 14, 121. doi:10.1186/s13578-024-01301-w. [Google Scholar]

- Slawson C, Copeland RJ, Hart GW. O-GlcNAc signaling: A metabolic link between diabetes and cancer? Trends Biochem. Sci. 2010, 35, 547–555. doi:10.1016/j.tibs.2010.04.005. [Google Scholar]

- Hu CW, Xie J, Jiang J. The Emerging Roles of Protein Interactions with O-GlcNAc Cycling Enzymes in Cancer. Cancers 2022, 14, 5135. doi:10.3390/cancers14205135. [Google Scholar]

- Yan J, Tang X, Zhou Y, Xiong X. GALNT6 associated with O-GlcNAcylation contributes to the tumorigenesis of oral squamous cell carcinoma. Discov. Oncol. 2025, 16, 132. doi:10.1007/s12672-025-02960-y. [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Jiang B, Zeng L, Tang Y, Qi X, Wan Z, et al. Adipocyte-derived exosomes promote the progression of triple-negative breast cancer through circCRIM1-dependent OGA activation. Environ. Res. 2023, 239 Pt 1, 117266. doi:10.1016/j.envres.2023.117266. [Google Scholar]

- Wang M, Qiao L, Jin L, Chen Y, Wen X, Wang H. OGT-regulated O-GlcNAcylation promotes the malignancy of colorectal cancer by activating STAT2 to induce macrophage M2: OGT protein macromolecule action. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 311 Pt 3, 144057. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2025.144057. [Google Scholar]

- Théry C, Witwer KW, Aikawa E, Alcaraz MJ, Anderson JD, Andriantsitohaina R, et al. Minimal information for studies of extracellular vesicles 2018 (MISEV2018): A position statement of the International Society for Extracellular Vesicles and update of the MISEV2014 guidelines. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2018, 7, 1535750. doi:10.1080/20013078.2018.1535750. [Google Scholar]

- Villarroya-Beltri C, Baixauli F, Gutiérrez-Vázquez C, Sánchez-Madrid F, Mittelbrunn M. Sorting it out: Regulation of exosome loading. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2014, 28, 3–13. doi:10.1016/j.semcancer.2014.04.009. [Google Scholar]