Short-Form Video Application Use and Self-Rated Health among Older Adults: The Mediating Role of Perceived Social Support and the Moderating Role of Media Literacy

Received: 27 October 2025 Revised: 18 November 2025 Accepted: 03 December 2025 Published: 08 December 2025

© 2025 The authors. This is an open access article under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

1. Introduction

With the rapid development of information and communication technologies, the use of the internet and online applications (apps) has become increasingly popular among older adults. For example, more than 50% of older adults in China are now using various digital applications, such as social media and e-shopping apps [1]. Notably, short-form video apps like TikTok have emerged as particularly prevalent. Recent data from the China Internet Network Information Center reveals that about 94% of Internet users engage in short-form video apps [2]. Correspondingly, older adults demonstrate a strong preference for these apps due to their user-friendly design, social interaction, and instant access [3]. These apps allow users to easily watch, create, and share videos lasting from several seconds to a few minutes [4]. Older adults frequently watch short videos related to current affairs, friends’ lives, and health-related knowledge, and they also often create videos to share their own lives or hobbies [2]. These usage behaviors may empower older adults to maintain their independence and engage in social activities, making the use of short-form video apps a crucial way to sustain health.

Previous studies on general internet use have demonstrated a positive relationship between Internet use and health-related indicators, such as self-reported health, activities of daily living, well-being, and cognitive functions [5,6,7,8]. However, the associations between short-form video app use and health outcomes in older adults, as well as the underlying psychological mechanisms of the associations, remain unclear. Currently, studies exploring the effects of using short video apps among older adults are limited. A few studies introduced the concept of addiction to short-form video apps, focusing on the negative impacts of such use [9,10]. But in these studies, older adults scored remarkably low on the addiction scale [9]. A national survey in China also showed that older adults spend an average of 1.5 h on short-form video apps, which is less than the average levels among all users [11]. The findings suggested that their engagement with short-form video apps may not be as problematic as previously assumed. The actual influence of using short video apps on the health outcomes of older adults requires further investigation.

1.1. Short-Form Video App Use and Self-Rated Health

Considerable studies have examined the positive implications of Internet use on various health outcomes among older adults. Specifically, studies suggest that Internet use can improve older adults’ well-being [8]. This could be attributed to increased contact with friends and family [12,13] and enhanced engagement in online leisure activities such as playing digital games, watching films, and listening to music [14]. Additionally, the internet provides a cognition-stimulating environment that could benefit cognitive functions in older adults [5]. Furthermore, online health-related information may promote healthy behaviors in older adults. For example, a large sample survey found that around 80% of older adult Internet users acquire health-related knowledge through the internet [15], which might encourage them to engage in healthy activities such as healthy diets and exercises [16]. Short-form video apps, among the latest forms of online apps, can be used for various purposes, such as staying in touch with family and friends, watching entertaining or health-related videos, learning or sharing knowledge, and seeking health information. Building on the positive effects of Internet use observed in previous studies, we hypothesized that short-form video app use is positively related to health outcomes among older adults (Hypothesis 1). Self-rated health was chosen as a suitable indicator in our study as it integrates different aspects of health [17], and it is easy for older adults to assess and respond.

1.2. Short-Form Video App Use and Perceived Social Support

There is growing evidence that Internet use influences health through various mental factors, with perceived social support being a crucial yet often overlooked factor. Perceived social support refers to individuals’ perceptions of available support and care from their social ties [18]. It is even more important than the actually received social support in predicting health-related indicators [19]. The frequency of social contact can influence perceived social support, and older adults with higher frequencies of social contact typically report greater perceived social support [20]. First, short-form video apps allow users to share interesting videos with others on social media platforms (e.g., WeChat) and to engage in more common discussion topics [21]. This may increase the frequency with which older adults contact their family and friends [3], and further heighten the closeness of existing relationships [22]. Second, older adults who actively share content on short-form video apps may receive positive feedback, such as likes and comments. This can enhance their perceived social support [23]. Third, interaction with content creators may develop a parasocial relationship characterized by a one-sided sense of intimacy toward the creators [24], resulting in improved perceived emotional support. A recent study also revealed that older adults’ use of short-form video apps improved their interpersonal satisfaction [25]. Thus, it is reasonable to expect short-form video app use to be positively related to perceived social support among older adults. According to the main effect model of social support, social support is related to a series of mental and physical outcomes [26]. Perceiving more social support is associated with less psychological distress [27], better hypertension control [28], higher levels of vitality [29], and better self-reported health [30]. Therefore, we hypothesized that perceived social support mediated the relationship between short-form video app use and self-rated health (Hypothesis 2).

1.3. The Moderating Role of Media Literacy

Although the use of short-form video apps can contribute to perceived social support and thereby health outcomes, the extent may depend on older adults’ media literacy. The United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (2013) defines media literacy as the ability to access, understand, evaluate, use, and create as well as share media information in various formats [31]. The ability to evaluate true and false information is most important for older adults [32]. Older adults use short-form video apps for various purposes, including watching videos on current affairs, health-related information, funny stories, leisure activities, and updates shared by family members or friends [3]. According to the uses and gratifications theory, individuals use the internet in different ways to satisfy their motivations and needs [33]. This indicates that older adults with different levels of media literacy may engage with short-form video apps in varied manners. As social support is a key predictor of media literacy among older adults [34], those with higher levels of media literacy may have already gained more support from their social networks. Therefore, they may be more inclined to use short-form video apps for purposes other than improving social connections, such as learning health-related knowledge [35]. In addition, their higher media literacy may lead them to use other types of apps, not just short-form video ones, to maintain or develop social ties. As a result, the positive effect of short-form video app use on their perceived social support may be too small to detect. In contrast, older adults with lower levels of media literacy may experience weaker social support. The compensation hypothesis argues that online engagement can compensate for insufficient offline social networks [22,36]. Therefore, the association between short-form video app use and perceived social support may be stronger among older adults with lower levels of media literacy. We proposed that the mediating effect of perceived social support was stronger among older adults with lower levels of media literacy than among those with higher levels (Hypothesis 3).

Short-form video apps are increasingly popular among older adults worldwide, including in China. However, the relationship between short-form video app use and health outcomes among older adults, as well as the underlying mechanisms, remains largely unexplored. In our study, we aimed to test three hypotheses. First, short-form video app use is positively associated with self-rated health in older adults. Second, perceived social support mediates the positive association between short-form video app use and self-rated health. Finally, media literacy moderates the positive association between short-form video app use and perceived social support, with the association being weaker among older adults with higher (vs. lower) levels of media literacy.

2. Methods

Participants

Using convenience sampling method, we recruited 392 participants to complete a survey distributed online or offline. After excluding 70 participants with excessively quick responses and 3 with fixed responses to questions, the final sample size was 319 (valid response rate = 81.38%). Of the 319 participants, 56.74% were 55–59 years old, 13.79% were 60–64 years old, 20.38% were 65–69 years old, and 9.09% were over 70 years old. Males accounted for 42.00% of the sample. Regarding educational level, the proportions of subjects with primary school or below, with middle and high school, and those with bachelor’s degrees or above were 30.72%, 61.13%, and 8.15%, respectively. Table 1 summarizes the demographic characteristics of the participants. Before completing the questionnaire, consent to participate was obtained from older adults.

Table 1. Demographic Characteristics of the Sample (N = 319).

|

Variables |

n |

% |

|---|---|---|

|

Age |

||

|

55–59 years old |

181 |

56.74 |

|

60 to 64 years old |

44 |

13.79 |

|

65 to 69 years old |

65 |

20.38 |

|

≥70 years old |

29 |

9.09 |

|

Gender |

||

|

Male |

134 |

42.00 |

|

Female |

185 |

58.00 |

|

Education |

||

|

Primary school or below |

98 |

30.72 |

|

Middle and high school |

195 |

61.13 |

|

University or more education |

26 |

8.15 |

|

Living arrangement |

||

|

Live alone |

45 |

14.11 |

|

Live with a spouse |

173 |

54.23 |

|

Live with children |

49 |

15.36 |

|

Others |

52 |

16.30 |

|

Martial status |

||

|

Married with a spouse |

239 |

74.92 |

|

Widowed |

33 |

10.34 |

|

Divorced |

39 |

12.23 |

|

Never married |

8 |

2.51 |

|

Monthly income |

||

|

≤2000 CNY |

105 |

32.92 |

|

2001 to 4000 CNY |

139 |

43.57 |

|

≥4000 CNY |

75 |

23.51 |

3. Measures

3.1. Short-Form Video App Use

Based on the assessment of Internet usage in previous studies [37,38], to measure the frequency of short-form video apps use, participants were asked to report how often they use short-form video apps on their mobile phones (0 = hardly ever use, 1 = about once a week, 2 = about two to four times once a week, 3 = about five to seven times once a week, 4 = use it many times a day). Participants were also asked to report how much time they spend on average each time they use short-form video apps (1 = less than 30 min, 2 = 30 to 60 min, 3 = 61 to 90 min, 4 = 91 to 120 min, and 5 = more than 120 min). To calculate the weekly intensity of short-form video app use, we multiplied the frequency score by the average use time. The resulting value served as the independent variable, with a higher score indicating a higher frequency of short-term video app use.

3.2. Perceived Social Support

The Social Support Rating Sub-Scale was used to measure perceived social support [39]. This scale contains 8 items, each with a score ranging between 1 and 4. An example item is “How much support and care do you get from your partner/parents/children/siblings/others?”. Response options include “1 = none”, “2 = very few”, “3 = some”, and “4 = fully support”. The final score was calculated by summing the scores across all eight items, with a higher score indicating higher perceived social support. The Cronbach’s coefficient of this scale was 0.77.

3.3. Self-Rated Health (SRH)

Participants were asked to rate how they feel about their health on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = very poor, 2 = fairly poor, 3 = average, 4 = fairly good, 5 = very good) [40].

3.4. Media Literacy

The Media Literacy Sub-Scale was used to measure media literacy level [41]. The term “media” was adjusted to “short videos” in our study. The scale contains 5 items. Two sample items are “I can evaluate the credibility of the information in a short video by searching supporting material” and “I can evaluate the credibility of the information in a short video based on the title and content”. Participants rated each item on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree). Higher scores indicated greater evaluative ability. The Cronbach’s coefficient of the scale was 0.89.

3.5. Statistical Analysis

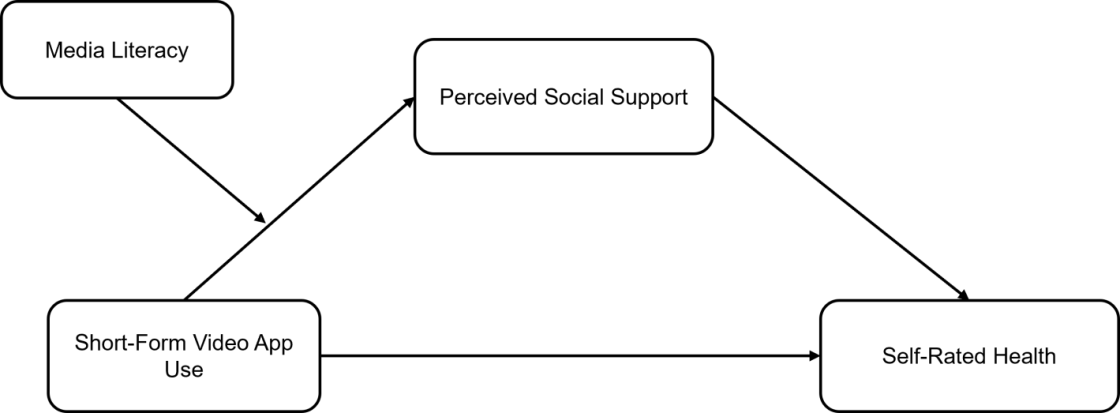

First, descriptive statistics and correlation analysis were conducted using SPSS 26.0. Second, we calculated the regression coefficients for self-rated health and short-form video app use to test Hypothesis 1. Third, the mediating role of perceived social support was examined using Model 4 of the PROCESS macro program [42]. In the mediation model, short-form video app use served as the independent variable, self-rated health as the outcome variable, and perceived social support as the mediating variable. The 95% bootstrap confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated for the model effects for the significance test (an effect was deemed non-significant if its CI covered 0). Finally, the Model 7 of the PROCESS macro program was used to test the moderated mediation effect [42], in which we included the moderating effect of media literacy on the link between short-form video app use and perceived social support into the mediation model specified in the third step above. Age, marital status, and living arrangement (dummy coded) were controlled in all models. Figure 1 illustrated the moderated mediation model we constructed.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Results

The mean, standard deviation, and intercorrelation of all the variables are shown in Table 2. Short-form video app use was positively related to self-rated health (r = 0.45, p < 0.001), perceived social support (r = 0.37, p < 0.001), and media literacy (r = 0.32, p < 0.001). Perceived social support was positively correlated with media literacy (r = 0.41, p < 0.001) and self-rated health (r = 0.55, p < 0.001). There was a positive relationship between media literacy and self-rated health (r = 0.30, p < 0.001).

Table 2. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations for Interested Variables.

|

Variable |

M |

SD |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Short-form video app use |

7.52 |

5.63 |

- |

|||

|

Perceived social support |

24.07 |

4.54 |

0.37 *** |

- |

||

|

Media literacy |

18.42 |

4.67 |

0.32 *** |

0.41 *** |

- |

|

|

Self-rated health |

3.46 |

1.21 |

0.45 *** |

0.55 *** |

0.30 *** |

- |

Note. M = mean; SD = standard deviation. *** p < 0.001.

4.2. Short-Form Video Use and Self-Rated Health

The results of the linear regression analysis showed that short-form video app use positively predicted self-rated health (b = 0.28, p < 0.001), which supported our Hypothesis 1.

4.3. The Mediating Effect of Perceived Social Support

All path coefficients in the mediation model are presented in Table 3. The results revealed that short-form video app use positively predicted perceived social support (b = 0.21, p < 0.001), and perceived social support positively predicted self-rated health (b = 0.33, p < 0.001). After including perceived social support in the regression model, short-form video app use still positively predicted self-rated health (b = 0.21, p < 0.001). The indirect effect of short-form video app use on self-rated health via perceived social support was 0.07 (accounting for 25% of the total effect), with a 95% confidence interval of [0.03, 0.11], indicating that perceived social support significantly mediated the relationship between short-form video app use and self-rated health. Hypothesis 2 was verified.

Table 3. Regression Results for Testing the Mediating Role of Perceived Social Support in the Relationship Between Short-Form Video App Use and Self-Rated Health.

|

Outcome Variable |

Predictors |

R2 |

F |

df1, df2 |

b |

SE |

p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Perceived social support |

Short-form video app use |

0.37 |

18.23 |

10, 308 |

0.21 |

0.05 |

<0.001 |

|

Self-rated health |

Short-form video app use |

0.44 |

22.05 |

11, 307 |

0.21 |

0.05 |

<0.001 |

|

Perceived social support |

0.33 |

0.05 |

<0.001 |

Note. All variables in the table have been standardized.

As shown in Table 4, the moderated mediation model revealed that short-form video app use positively predicted perceived social support (b = 0.18, p < 0.01), and the interaction effect between short-form video app use and media literacy on perceived social support was significant (b = −0.19, p < 0.01), indicating that media literacy played a significant moderating role in the relationship between short-form video app use and perceived social support.

Table 4. Regression Results for Testing the Moderating Role of Media Literacy in the Relationship Between Short-Form Video App Use and Perceived Social Support

|

Outcome Variable |

Predictors |

R2 |

F |

df1, df2 |

b |

SE |

p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Perceived social support |

Short-form video app use |

0.44 |

20.06 |

12, 306 |

0.18 |

0.05 |

<0.01 |

|

Media literacy |

0.15 |

0.06 |

<0.01 |

||||

|

Short-from video app use × media literacy |

−0.19 |

0.06 |

<0.01 |

||||

|

Self-rated health |

Short-form video app use |

0.44 |

22.05 |

11, 307 |

0.21 |

0.05 |

<0.001 |

|

Perceived social support |

0.33 |

0.05 |

<0.001 |

Note. All variables in the table have been standardized.

The results of the follow-up simple slope test showed that short-form video app use positively predicted perceived social support (b = 0.37, SE = 0.09, p < 0.01, 95% CI = [0.19, 0.55]) among older adults with lower levels of media literacy, but not among those with higher levels of media literacy (b = −0.01, SE = 0.07, p > 0.05, 95% CI = [−0.15, 0.13]), as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. The Moderating Effect of Media Literacy on the Relationship Between Short-Form Video App Use and Perceived Social Support.

The mediating effect of perceived social support on the relationship between short-form video aApp use and self-rated health was significant (estimated effect = 0.12, bootstrap SE = 0.04, 95% CI = [0.05, 0.20]) among older adults with lower levels of media literacy, but not among those with higher levels of media literacy (estimated effect = −0.003, bootstrap SE = 0.02, 95% CI = [−0.05, 0.04]).

5. Discussion

Our study revealed a positive association between short-form video app use and self-rated health among older adults, with perceived social support mediating this association. Moreover, we identified a significant interaction between short-form video app use and media literacy on perceived social support. Specifically, short-form video app use was positively associated with perceived social support among older adults with lower media literacy, but not among those with higher media literacy.

The finding of a positive relationship between short-form video app use and self-rated health among older adults is consistent with previous studies showing that Internet use can improve health-related outcomes among older adults [7,8]. The active aging framework emphasizes the importance of optimizing older adults’ opportunities for health, participation, and security to enhance their quality of life. Short-form video apps can facilitate social participation in digital ways. For example, they enable older adults to connect with a larger social network, access social news, acquire knowledge, and engage in self-presentation. Importantly, these online behaviors may promote older adults’ offline activities, such as visiting others, participating in educational courses, and doing volunteer work [43,44], which are linked to reduced cognitive decline [45] and decreased psychological distress [46]. Therefore, short-form video app use may be beneficial for older adults’ health. While many studies have focused on addiction to short-form video apps or other online applications among younger adults [47,48], studies on older adults suggest that digital platforms can serve as valuable tools for social participation, with current findings indicating significant potential benefits. Given the widespread popularity of short-form video apps in China and their demonstrated positive effects, promoting their use among older adults could be an effective strategy to reduce the digital divide. Intervention programs should consider incorporating short-form video apps as a tool to promote older adults’ social well-being and health.

The present study also revealed that perceived social support mediated the relationship between the use of short-form video apps and self-rated health. Internet use, including the use of short-form video apps, allows older adults to easily maintain contact with distant friends or family [49], which facilitates their communication with others on the platforms. Short-form video app use also reinforces older adults’ interaction with geographically proximal individuals. Staying updated with news of others, liking or commenting on others’ content, and sharing videos with others create more opportunities for communication. At the same time, older adults can also receive help from their families or friends if they encounter difficulties using online apps [50]. Therefore, the use of short-form video apps can enhance older adults’ perceived social support, and perceived social support, in turn, benefits their self-rated health, according to previous empirical studies and theories such as the main effect model of social support [26,27,30]. However, the mediating effect of perceived social support only contributed to 25% of the total effect of short-form video app use and self-rated health, suggesting the existence of other mechanisms. More than 40% of older adults watch health-related videos on short-form video apps [3], which may promote physical activities and self-treatment of common diseases [51,52]. Future studies can examine the mediating roles of health information exposure and health behaviors, other than perceived social support, to better understand how short-form video app use is positively associated with the health of older adults.

Another important finding of our study was that the mediating effect of perceived social support on the relationship between short-form video app use and self-rated health was significant only among older adults with lower, not higher, levels of media literacy. One possible explanation for this finding is that, compared with those with lower media literacy, older adults with higher media literacy might be more inclined to use short-form video apps for non-social purposes (e.g., information seeking) rather than for socializing, which attenuated the mediating effect of perceived social support. An alternative interpretation is that participants with lower media literacy generally had lower levels of perceived social support than their counterparts with higher media literacy (see Figure 2). This discrepancy may be attributed to the fact that older adults with lower media literacy tended to have a lower socioeconomic status (in our sample, r media literacy, income = 0.33, p < 0.001), fewer resources, and smaller social networks. As proposed by the compensation hypothesis, these participants might benefit more from using the internet and short-form video apps to compensate for their lack of social connections in real life through several mechanisms, such as reconnecting with old friends, strengthening the existing networks, and fostering new social connections [36,53]. In contrast, the positive effect of short-form video app use on perceived social support may be weaker or even non-significant for older adults with higher levels of media literacy, as they may already have higher levels of social support, leaving little room for further improvement. This finding aligns with previous studies [54]. Altogether, the present study suggests that the variation in the levels of media literacy and perceived real-life social support may contribute to explaining the inconsistent findings regarding whether internet use benefits or harms individuals’ well-being (e.g., depression and loneliness) in the existing literature [53].

6. Limitations

Several limitations of the present study should be acknowledged. First, the type or purpose of short-form video app use was not measured, which might restrict our interpretation of current results. Prior studies suggest that only active use of short-form video apps predicts enhanced well-being [55], and more information about social media use is needed to better understand its influence on older adults’ well-being and health [56]. Future studies could further investigate the differential effects of active and passive use. Second, the use of a convenience sampling method limits the generalizability of the findings. Specifically, since half of the participants were aged 55–60 and only 9.09% were aged 70 or above, the conclusions may be primarily relevant to the young-old adults. Thirdly, given the popularity of short-form video apps in China and their demonstrated benefits for older adults, future research could investigate the acceptance and influence of these platforms among older adults in other cultural contexts. Finally, the cross-sectional survey design of our study limits the interpretation of the causal relationship between the variables. Based on these preliminary results, future studies should collect and analyze large, nationally representative longitudinal data or conduct intervention experiments to further reveal their relationships.

7. Conclusions

The present study demonstrated a positive correlation between short-form video app use and health, which provides valuable implications for using digital technology to enhance older adults’ well-being and health. Moreover, the study unveiled the mediating role of perceived social support in the relationship between short-form video app use and health. Interestingly, the positive relationship between short-form video app use and perceived social support was observed only in older adults reporting lower media literacy. These findings suggest that it could be particularly useful to promote appropriate use of short-form video apps among older adults with lower literacy levels (or lower socioeconomic status) in order to boost their well-being and health.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge all participants in this study. Thanks for Yande Pan’s contribution to data collection.

Author Contributions

J.X.: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing—original draft; S.Y.: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing—review & editing; X.Z.: Conceptualization, Validation, Writing—review & editing; X.G.: Supervision, Validation, Writing—review & editing; W.S.: Writing—review & editing; Q.Y.: Writing—review & editing. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Ethics Statement

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Normal School of Hubei University (protocol code 20221010 and date of approval: 10 October 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants included in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Funding

This work was supported by Department of Education of Hubei Province of China under Grant [number 22ZD033].

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

-

China Internet Network Information Center. The 51st Statistical Report on China’s Internet Development; China Internet Network Information Center: Beijing, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

-

China Internet Network Information Center. The 55th Statistical Report on China’s Internet Development; China Internet Network Information Center: Beijing, China, 2025. [Google Scholar]

-

Jin YA, Liu WL, Zhao MH, Wang DH, Hu WB. Short video app use and the life of mid-age and older adults: An exploratory study based on a social survey. Popul. Res. 2021, 45, 31–45. [Google Scholar]

-

Zhang X, Wu Y, Liu S. Exploring short-form video application addiction: Socio-technical and attachment perspectives. Telemat. Inform. 2019, 42, 101243. doi:10.1016/j.tele.2019.101243. [Google Scholar]

-

Kamin ST, Lang FR. Internet use and cognitive functioning in late adulthood: longitudinal findings from the survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE). J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2018, 75, 534–539. doi:10.1093/geronb/gby123. [Google Scholar]

-

Luo Y, Yip PSF, Zhang QP. Positive association between Internet use and mental health among adults aged ≥50 years in 23 countries. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2024, 9, 90–100. doi:10.1038/s41562-024-02048-7. [Google Scholar]

-

Nakagomi A, Shiba K, Kawachi I, Ide K, Nagamine Y, Kondo N, et al. Internet use and subsequent health and well-being in older adults: An outcome-wide analysis. Comput. Human Behav. 2022, 130, 107156. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2021.107156. [Google Scholar]

-

Shapira N, Barak A, Gal I. Promoting older adults’ well-being through Internet training and use. Aging Ment. Health 2007, 11, 477–484. doi:10.1080/13607860601086546. [Google Scholar]

-

Deng JS, Wang MM, Mu WQ, Li SY, Zhu NH, Luo X, et al. The relationship between addictive use of short-video platforms and marital satisfaction in older Chinese couples: An asymmetrical dyadic process. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 364. doi:10.3390/bs14050364. [Google Scholar]

-

Xu J, Ramayah T, Arshad MZ, Ismail A, Jamal J. Decoding digital dependency: Flow experience and social belonging in short video addiction among middle-aged and elderly Chinese users. Telemat. Inform. 2025, 96, 102222. doi:10.1016/j.tele.2024.102222. [Google Scholar]

-

Jin YA, Hu WB, Feng Y. Internet use and the life of older adults aged 50 and above in digital era: Findings from a national survey. Popul. Res. 2024, 48, 40–55. [Google Scholar]

-

Li J, Zhou XC. Internet use and Chinese older adults’ subjective well-being (SWB): The role of parent-child contact and relationship. Comput. Human. Behav. 2021, 119, 106725. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2021.106725. [Google Scholar]

-

Yu KX, Wu SY, Chi I. Internet use and loneliness of older adults over time: The mediating effect of social contact. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2021, 76, 541–550. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbaa004. [Google Scholar]

-

Lifshitz R, Nimrod G, Bachner YG. Internet use and well-being in later life: A functional approach. Aging Ment. Health 2018, 22, 85–91. doi:10.1080/13607863.2016.1232370. [Google Scholar]

-

Hong YA, Cho J. Has the digital health divide widened? Trends of health-related internet use among older adults from 2003 to 2011. J Gerontol. 2017, 72, 856–863. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbw100. [Google Scholar]

-

Dutta-Bergman MJ. Health attitudes, health cognitions, and health behaviors among Internet health information seekers: Population-based survey. J. Med. Internet Res. 2004, 6, e15. doi:10.2196/jmir.6.2.e15. [Google Scholar]

-

Jylhä M. What is self-rated health and why does it predict mortality? Towards a unified conceptual model. Soc. Sci. Med. 2009, 69, 307–316. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.05.013. [Google Scholar]

-

Pillemer SC, Holtzer R. The differential relationships of dimensions of perceived social support with cognitive function among older adults. Aging Ment. Health 2016, 20, 727–735. doi:10.1080/13607863.2015.1033683. [Google Scholar]

-

Wethington E, Kessler RC. Perceived support, received support, and adjustment to stressful life events. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1986, 27, 78–79. doi:10.2307/2136504. [Google Scholar]

-

Ang S. Changing relationships between social contact, social support, and depressive symptoms During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2022, 77, 1732–1739. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbac063. [Google Scholar]

-

Vaterlaus JM, Winter M. TikTok: An exploratory study of young adults’ uses and gratifications. Soc. Sci. J. 2025, 62, 613–632. doi:10.1080/03623319.2021.1969882. [Google Scholar]

-

Valkenburg PM, Peter J. Preadolescents’ and adolescents’ online communication and their closeness to friends. Dev. Psychol. 2007, 43, 267–277. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.43.2.267. [Google Scholar]

-

Yue D, Liu LJ, Yu K. Interpersonal relationship satisfaction in the digital age: The role of online positive feedback and perceived social support. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 2025. doi:10.16187/j.cnki.issn1001-4918.2026.01.05. [Google Scholar]

-

Kim J, Song H. Celebrity’s self-disclosure on Twitter and parasocial relationships: A mediating role of social presence. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 62, 570–577. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2016.03.083. [Google Scholar]

-

Li C, Wang YY. Short-form video applications usage and functionally dependent adults’depressive symptoms: A cross-sectional study based on a national survey. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2024, 17, 3099–3111. doi:10.2147/RMHP.S491498. [Google Scholar]

-

Cohen S, Wills TA. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychol. Bull. 1985, 98, 310–357. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.98.2.310. [Google Scholar]

-

Xiao SJ, Shi L, Dong F, Zheng X, Xue YQ, Zhang JC, et al. The impact of chronic diseases on psychological distress among the older adults: the mediating and moderating role of activities of daily living and perceived social support. Aging Ment. Health 2022, 26, 1798–1804. doi:10.1080/13607863.2021.1947965. [Google Scholar]

-

Zhu TF, Xue J, Chen SL. Social support and depression related to older adults’ hypertension control in rural China. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2019, 27, 1268–1276. doi:10.1016/j.jagp.2019.04.014. [Google Scholar]

-

Carrapatoso S, Cardon G, Van Dyck D, Carvalho J, Gheysen F. Walking as a mediator of the relationship of social support with vitality and psychological distress in older adults. J. Aging Phys. Act. 2018, 26, 430–437. doi:10.1123/japa.2017-0030. [Google Scholar]

-

Krause N. Satisfaction with social support and self-rated health in older adults. Gerontologist 1987, 27, 301–308. doi:10.1093/geront/27.3.301. [Google Scholar]

-

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. Global Media and Information Literacy Assessment Framework; United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization: Paris, France, 2013. [Google Scholar]

-

Huang DY, Qiu ZQ. Media and information literacy assessment framework for the elderly in digital environment. Libr. Trib. 2021, 41, 96–107. [Google Scholar]

-

Katz E, Blumler JG, Gurevitch M. Uses and gratifications research. Public Opin. Q. 1973, 37, 509–523. doi:10.1086/268109. [Google Scholar]

-

Wu JX, Peng HM. Family guidance regarding internet mitigates older adults’ ehealth literacy inequality due to educational attainment through internet use. Geriatr. Nurs. 2025, 61, 414–422. doi:10.1016/j.gerinurse.2024.12.002. [Google Scholar]

-

Shang LL, Zuo MY. Investigating older adults’ intention to learn health knowledge on social media. Educ. Gerontol. 2020, 46, 350–363. doi:10.1080/03601277.2020.1759188. [Google Scholar]

-

Peter J, Valkenburg PM, Schouten AP. Developing a model of adolescent friendship formation on the internet. Cyberpsychol Behav. 2005, 8, 423–430. doi:10.1089/cpb.2005.8.423. [Google Scholar]

-

Liu SQ, Zhao HY, Fu JJ, Kong DH, Zhong Z, Hong Y, et al. Current status and influencing factors of digital health literacy among community-dwelling older adults in Southwest China: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public. Health 2022, 22, 996. doi:10.1186/s12889-022-13378-4. [Google Scholar]

-

Yuan H. Internet use and mental health problems among older people in Shanghai, China: the moderating roles of chronic diseases and household income. Aging Ment. Health 2021, 25, 657–663. doi:10.1080/13607863.2020.1711858. [Google Scholar]

-

Xiao SY. The theoretical basis and application of the Social Support Rating Scale. J. Clin. Psychiatry 1994, 2, 98–100. [Google Scholar]

-

Jylhä M, Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L, Jokela J, Heikkinen E. Is self-rated health comparable across cultures and genders? J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 1998, 53, S144–S152. doi:10.1093/geronb/53B.3.S144. [Google Scholar]

-

Li JC. Construction and validation of measurement scale of media literacy. E-Educ. Res. 2017, 38, 20–27. [Google Scholar]

-

Hayers AF. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Apporoach; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

-

Kamin ST, Seifert A, Lang FR. Participation in activities mediates the effect of Internet use on cognitive functioning in old age. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2021, 33, 83–88. doi:10.1017/S1041610220003634. [Google Scholar]

-

Kim J, Lee HY, Christensen MC, Merighi JR. Technology access and use, and their associations with social engagement among older adults: Do women and men Differ? J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. 2016, 72, 836–845. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbw123. [Google Scholar]

-

Biddle KD, d’Oleire Uquillas F, Jacobs HIL, Zide B, Kirn DR, Rentz DM, et al. Social engagement and Amyloid-β-Related cognitive decline in cognitively normal older adults. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2019, 27, 1247–1256. doi:10.1016/j.jagp.2019.05.005. [Google Scholar]

-

Mackenzie CS, Abdulrazaq S. Social engagement mediates the relationship between participation in social activities and psychological distress among older adults. Aging Ment. Health 2021, 25, 299–305. doi:10.1080/13607863.2019.1697200. [Google Scholar]

-

Lozano-Blasco R, Robres AQ, Sánchez AS. Internet addiction in young adults: A meta-analysis and systematic review. Comput. Human Behav. 2022, 130, 107201. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2022.107201. [Google Scholar]

-

Yang ZY, Griffiths MD, Yan ZH, Xu WT. Can watching online videos be addictive? A qualitative exploration of online video watching among Chinese young adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2021, 18, 7247. doi:10.3390/ijerph18147247. [Google Scholar]

-

Quan-Haase A, Mo GY, Wellman B. Connected seniors: how older adults in East York exchange social support online and offline. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2017, 20, 967–983. doi:10.1080/1369118X.2017.1305428. [Google Scholar]

-

Tsai HY, Shillair R, Cotten SR. Social support and “playing around”: An examination of how older adults acquire digital literacy with tablet computers. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2017, 36, 29–55. doi:10.1177/0733464815609440. [Google Scholar]

-

Li G, Han CF, Liu PH. Does internet use affect medical decisions among older adults in China? Evidence from CHARLS. Healthcare 2021, 10, 60. doi:10.3390/healthcare10010060. [Google Scholar]

-

Shen C, Wang MP, Wan A, Viswanath K, Chan SSC, Lam TH. Health information exposure from information and communication technologies and its associations with health behaviors: Population-based survey. Prev. Med. 2018, 113, 140–146. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2018.05.018. [Google Scholar]

-

Nowland R, Necka EA, Cacioppo JT. Loneliness and social internet use: Pathways to reconnection in a digital world? Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2018, 13, 70–87. doi:10.1177/1745691617713052. [Google Scholar]

-

Woznicki N, Arriaga AS, Caporale-Berkowitz NA, Parent MC. Parasocial relationships and depression among LGBQ emerging adults living with their parents during COVID-19: The potential for online support. Psychol. Sex. Orientat. Gend. Divers. 2021, 8, 228–237. doi:10.1037/sgd0000458. [Google Scholar]

-

Wu YL, Wang XN, Hong S, Hong M, Pei M, Su YJ. The relationship between social short-form videos and youth’s well-being: It depends on usage types and content categories. Psychol. Pop. Media 2021, 10, 467–477. doi:10.1037/ppm0000292. [Google Scholar]

-

Cotten SR, Schuster AM, Seifert A. Social media use and well-being among older adults. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2022, 45, 101293. doi:10.1016/j.copsyc.2021.12.005. [Google Scholar]