Defiant Doctorates: Reshaping the Social, Cultural and Intellectual Value of the Doctorate in Regional Universities

Received: 08 September 2025 Revised: 14 November 2025 Accepted: 01 December 2025 Published: 09 December 2025

© 2025 The authors. This is an open access article under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Doctoral Studies and the Scholarship of Supervision (SoS) are (post)disciplines that are emerging from the intellectual shadows and acquiring profile and propulsion, journals and special issues. Too often the discarded rag doll of Critical Higher Education Studies and the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning (SoTL), the weaponization of the PhD by the Alt-Right and right-wing populist political movements [1] has meant that enrolling in a doctorate, supervising a doctorate, and carrying a doctoral qualification through a professional life is a statement of commitment, excellence and courage. It confirms a belief in reading, writing, and scholarship, often against the policies and agendas within a nation-state.

For example, the Australian University’s Accord discussed ‘Research Training’ rather than ‘Research Education’ [2]. But even more significantly, the value of regional, rural, and remote universities was compressed into a deficit ideology. These institutions were clustered with other markers of marginalization: low socio-economic background, Indigenous citizens, women, older students, and students with a disability. Such an ideology has a profound impact on the valuing of these places and the people who populate them. This ideology crushes the different and defiant capacity of these universities to provide high-quality research education and doctoral programmes. This is not only an Australian issue. The focus on the international ranking of institutions through the Times Higher Education, the Quacquarelli Symonds (QS), and the Shanghai Academic Ranking of World Universities (ARWU) assumes and measures a standard of quality and excellence that is applied like a blanket over the entire sector. What happens through such rankings is that the specificity—the defiant differences—of regional universities is lost when applying specific criteria for ‘quality’.

The role, function, and power of the PhD in regional universities is a profound absence in the Australian Universities Accord document [3]. This present article, working with Doctoral Studies and the Scholarship of Supervision, enacts this repair work. Written by an educator who is also a PhD student and a senior academic, this article summons these different lenses to add complexity to the thinking about the regional, rural, and remote PhD. Not as a deficit, or a lack, or a minimized and marginalized enrolment, but as a defiant statement of excellence and achievement from a national university system that ignores, minimizes, and compresses their value, role, and importance. The goal of this article is to ‘hold the space’ for a regional doctoral candidate so that their voices, views, and decisions are recognized and logged with respect. This research is enabled through the specialisms emerging in SoS, such as supervisory selection [4], attrition rates for specific sociological groups [5], reciprocity and vulnerability [6], and motivations to write [7]. This diversity of learning-led research is welcome. Our research contributes to welcoming the diversity of Doctoral Studies and SoS, with attention to place-based research education. This is both a theoretical and conceptual paper, creating and holding space for PhD students in a revisioning of regional universities.

This article has two parts, written by each of the named authors. The first part of this article, written by Tara Brabazon, has two goals. The first explores the nature of regional—small—cities and the role of universities in building and sustaining this unique urbanity [8]. The second goal offers some shapes and possibilities for reorganizing and revisioning a different way of thinking about—and doing—a regional doctorate. The imperative is to park policy instruments that equate regional, rural, and remote doctoral programmes with deficit models of teaching and learning. The last part of this article, written by Matthew Crane, takes these models for a professional walk. He explores how a student, enrolled in a regional university, gains from this experience.

This article activates a more intricate and complex lens on and for regional doctoral programmes. We enact the repair work—the foundational research—for a topic that was so marginalized and minimized that a report on Australia’s university system did not mention it. Regional research education has incredible value. If it continues to be discarded or ignored, then the different and defiant intellectual context will remain misunderstood and neglected.

1. Regional, Rural and Remote as a Context for Place-Based Doctoral Education

Every nation has regional, rural, and remote locations, and they occupy a specific role and relational function. Unproductive binary oppositions dis/organize RRR education.

city/country,

centre/periphery,

exciting/banal,

innovative/nostalgic.

To add complexity to these simple divisions, the naming of areas as regional, rural and remote activates colonial and colonizing language, imposing value and importance on urbanity, tethering it to modernity. ‘Remote’ places are centres for knowledge, faith, memory, and history for Indigenous citizens, First Nations, and First Peoples. They are only labelled as regional, rural, or remote in relation to—and in opposition to—urban environments that are the hubs of commerce, finance, industry, and colonisation. Remote locations are not only configured through distance from a metropolis, but through a lack of (colonially configured) infrastructure. These labels and definitions are what Hallinan and Judd have described as “racialized thinking” [9], configuring particular narratives of progress that shadow—uncomfortably if predictably—colonizing histories that are fuelled by absences, gaps, and silences. Colonization continues to shunt these places outside of modernity, and they are defined through extreme difficulty and absence. Small populations enable the active forgetting of these places by policymakers and politicians, as confirmed by the 2024 Universities Accord document. Regional, rural, and remote locations are imagined into existence through a lack [10], constructed by national policies and measurement tools, delivered from large cities [11].

Too often, regional, rural, and remote locations are defined as places of problems and difficulties. Stuart Hall and others described “the career of a label” [12]. They were interested in how particular terms and concepts were stacked and packed with ideologies that are activated when a word is expressed. The career of the labels of regional, rural, and remote is marinated in crime and crisis, intensified through drought, iterative pandemics, economic injustice, floods, and climate emergencies. Through colonization, the regional, rural, and remote perpetuate the configuration of being in deficit to the urban. This deficit is defined through depopulation [13], reduction in health and education services [14], suicide rates [15], and extreme political views, which Cramer described as “the politics of resentment” [16]. While these injustices, inequalities, oppressions, and discriminations continue, the regional, rural, and remote are shaped and organized in the interests of global and second-tier cities that contain the political leadership, corporate headquarters, stock markets, well-funded and functional educational and health infrastructure, and direct, proxemic alignments of production and consumption.

Based on population or a lack of agency and autonomy in national policy decisions, RRR locations are reimagined through popular culture as backwaters, boring, dangerous, and irrelevant. Feminism and postcolonialism can interrupt and intervene in these binary oppositions. From this disruption and agitation, different theories can be offered, including an architecture of advocacy. Australia offers a key example in the international RRR story. Two-thirds of the Australian population live in major cities, making Australia one of the most urbanized populations in the world [11]. Australia also has one of the lowest population densities outside of the major cities. Therefore, most of the population can forget about the regional, rural, and remote in daily life.

Universities exist in these small cities. For academics, they present enormous advantages, including cheaper housing when compared to metropolitan centres, a greater diversity of experiences throughout the university with regard to tasks and roles, and more direct relationships between local governments, businesses, and not-for-profit organizations. The corresponding author for this article and the writer of this first part, Tara Brabazon, has chosen to work in these locations. Of the ten universities at which I have been employed, five were in regional areas of Australia, the United Kingdom, and Canada. As an academic, I know their strengths and weaknesses.

There is, however, a specific and new challenge emerging in these locations, revealed through Jason Cervone’s Corporatizing rural education: neoliberal globalization and reaction in the United States [17]. Cervone argued that waves of neoliberal globalization have battered regional towns and cities. Because the economies are brittle in these locations, corporations move in to exploit this situation. The ideology of weakness and deficit feeds into neoliberalism, with the ‘problems’ being solved by profit-motivated industries. This anti-statism bleeds into anti-governance and regulation, with profound consequences to health, education, and public services such as libraries.

There are political reverberations from this displacement and denial. In the United States, these “angry, white men and women” [17], as Cervone described them, were not validated or addressed by the major political parties until Donald Trump and MAGA. With migrants scapegoated for class-based economic injustices, the regional, rural, and remote environments were and are framed by problematic ideologies. Cervone argues that,

The corporatization of rural schools is based on the same ideology that has affected rural communities throughout US history, the ideology that shapes rural communities as backward and in need of modernization [17].

The rural and the regional are framed as in deficit and deficient, outside of modernity. The market economy, rather than public services, rectifies the weaknesses and lack. This invented problem triggers neoliberal solutions. Therefore, ‘modernization’ is mashed with the exploitation of people, animals, and the land. Education is cheapened, and public schooling is undermined. With an inadequate schooling system and few choices for alternative providers, rural and regional citizens continue to have fewer choices and options than those from larger cities. Such an ideology poses particular challenges for universities in these environments. Regional schools confront instability, including the churn of teaching staff, which impacts the quality of education for students. Therefore, it is more challenging for these students to receive the result that gets them to university.

Universities are important socially, economically, and culturally. But a different maxim is tested in this article: the smaller the city, the more important the university. Theorists of urbanity, including urban planners, city imaging researchers, and cultural policy scholars, often segment cities to enable transferable and generalizable knowledge. These tiers are: global cities, second-tier cities, and third-tier cities. Global cities are large international cities where corporations and financial capital are housed. They enable the mobility of people, ideas, and money. Many universities and an array of higher education institutions are available. Second-tier cities are the non-capital cities in their nations, defined relationally from global cities. They are the sites of research case studies, probing the specificity of Perth, Liverpool, Osaka, or Dundee. Multiple options for higher education are available. Choice of educational providers is possible. These cities gain the advantages of aggregation to services, particularly health, education, and a diverse workforce.

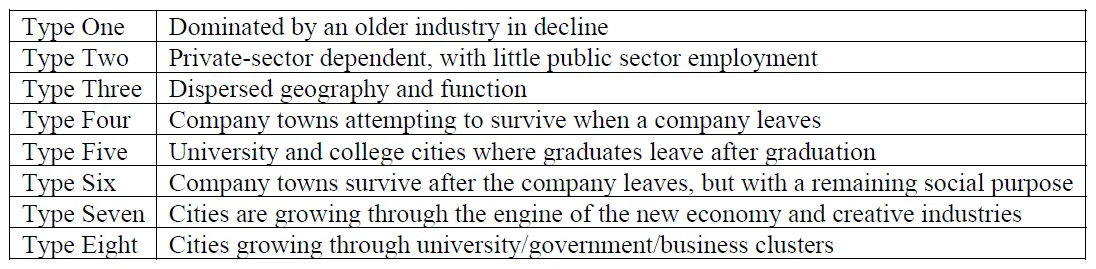

Regional Universities are located in third-tier cities. These small urban environments are not well known or internationally recognized. Lacking the benefit of aggregation, distinctive economic and social issues emerge. Most significantly for this article, the diversity of these small cities has been mapped. Erickcek and McKinney configured a powerful taxonomy of eight types [18], which is presented in Figure 1.

Universities are a determinant in two of the eight categories, depending on whether the graduates stay or leave the city after graduation. Erickcek and McKinney confirm that third-tier cities are diverse, as are the educational institutions within them. Cambridge University in Cambridge has little connection to Federation University in Ballarat. Both are third-tier cities with universities. Yet that is the end of the similarity. But is it? There are benefits that Cambridge and Federation share. Universities are employers of staff. While academics dominate, an array of retail and customer service, caretakers, sports and leisure workers, childcare specialists, gardeners, chefs, librarians, marketing professionals, and technicians are employed by the institution. They are also key employers of early-career academics, and provide infrastructure for residents of the city, including gyms, pools, coffee shops, and health clinics, including for psychology and speech pathology, to provide two common examples. They are, as Birch et al. confirmed, “anchor institutions” [19]. Regional universities are crucial for economic and social diversification. Doctoral students are not mentioned in this study, but the length of their enrolment, research dissemination processes, and expertise they hold and develop through the programme enable innovative knowledge development in regional locations. Doctoral students activate a very specific mode of “anchor” for social, economic, and knowledge development.

This anchoring also facilitated an array of powerful functions for regional development. Borlaug and Elken tracked the impact of ‘third mission’ activities, nesting entrepreneurism, technology transfer, and knowledge transfer [20]. They showed that regional universities activate “a wider range of knowledge transfer mechanisms, such as formal R&D collaborations between industry and universities, providing graduates to the regional labour market and informal collaboration” [20]. While their research confirms the benefit of academics working with community partners, the role of doctoral studies in building not only relationships but also gown and town alignments remains unaddressed. The value of doctoral students in building bridges between the professional and regional development goals in a regional location is under-discussed.

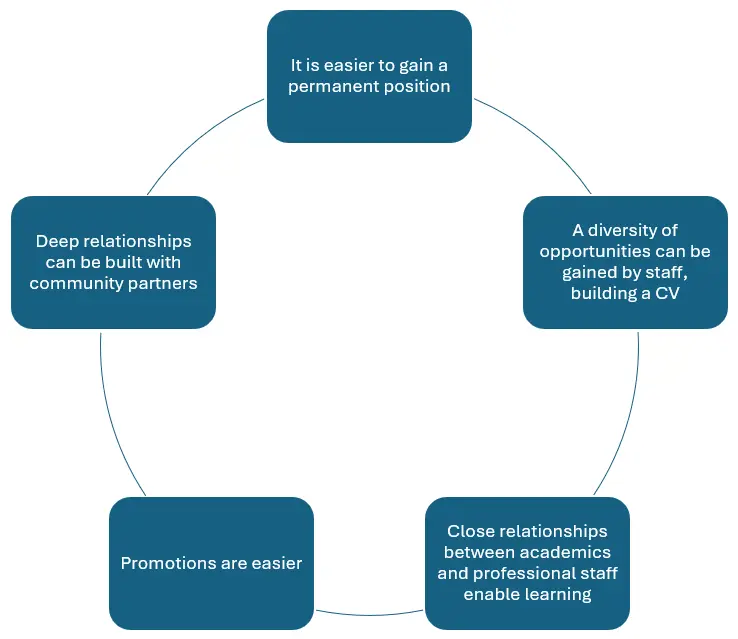

Recognizing this ‘third mission’ imperative and returning to Erickcek and McKinney’s early work, this article offers a different shaping and organization of their taxonomy to add further complexity to create both space and recognition for the role played by doctoral students. There are five strengths of regional universities, as shown in Figure 2.

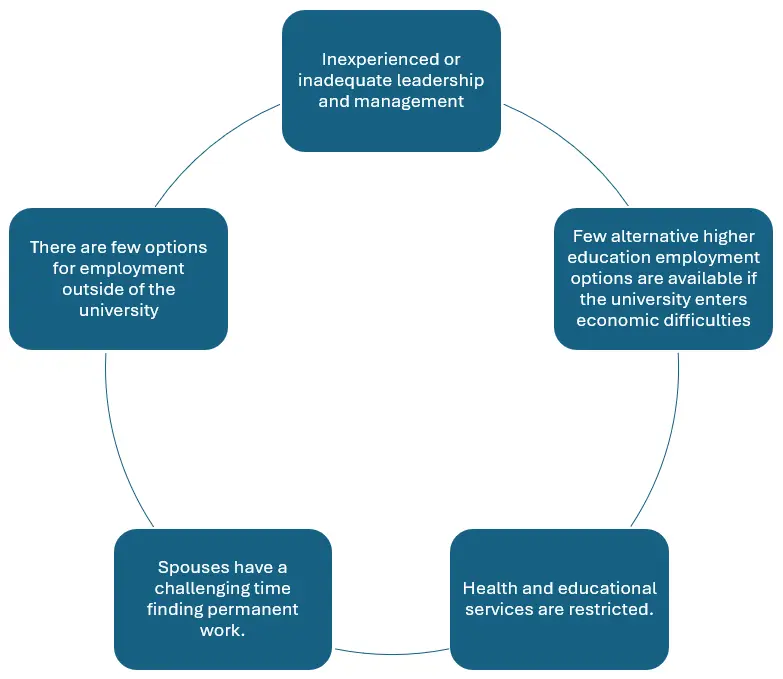

Similarly, there are five weaknesses, conveyed in Figure 3.

From these strengths and weaknesses, there are three modes of university in third-tier cities. Examples of the first mode of third-tier city universities include Massey University (New Zealand), Federation University, and Southern Cross University (Australia). The second type of institution, regional universities with campuses spread through regional locations, includes Central Queensland University and Charles Sturt University in Australia. In Aotearoa/New Zealand, the Institutes of Technology provide this function in further education, with Te Wānanga o Aotearoa an innovative tertiary education provider with full national coverage and specializing in regional, rural, and remote environments. The third type of institution is the outlier campus of a university with its ‘main’ campus in a capital city. For example, the University of Otago has a campus in Invercargill, New Zealand. Flinders University has campuses in Renmark and Mount Gambier, Australia. The University of Western Australia, based in the capital city of Perth, has a campus in Albany at the base of the state.

The specificity and distinctiveness of these models can be lost when focusing on regional development. For example, Boucher, Conway, and Van Der Meer confirmed—rightly—“the role of universities in regional economic development” [21]. They listed these functions as “to promote a learning environment, develop skills and build resources for competitiveness and social cohesion” [21], with a focus on “institutional thickness” [21]. They deployed this phrase to assess the sharing of knowledge beyond the university to promote cooperation. Once more, the role of doctoral students was unmentioned. But even more significantly, greater attention is required to recognize and track the diversity of institutions within the label of ‘Regional Universities’.

One significant way to map and differentiate these universities is to explore the role and place of doctoral education on the regional campus. The following guide questions are meaningful.

-

Is doctoral enrolment possible on this regional campus?

-

Are supervisors present on this regional campus?

-

Are the library and support facilities able to assist doctoral candidates?

-

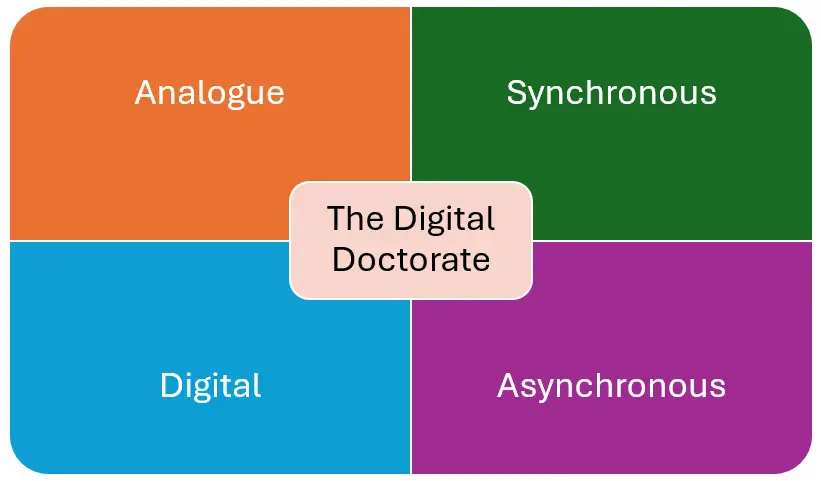

Are both synchronous and asynchronous, analogue and digital, professional development programmes available to and for students?

Such questions offer meaningful proxies to assess the degree of commitment to doctoral candidates in a regional university, and particularly an outlier regional campus of a metropolitan university, as presented in Figure 4. Paolo Seri and Lorenzo Compagnucci’s recent work has enlarged the assessable variables when researching university satellite campuses, with specific attention to “maximizing the formation of human capital” [22]. Yet once more, they focus on the entire graduate population, rather than the specific role of doctoral candidates through their candidature, examination, and graduation.

While the literature confirms the economic and social impact of all regional university campuses, differentiation and granularity do matter, and the positioning and support for doctoral education is an important—if frequently invisible—enrolment to consider. A key variable for assessment is the capping of student expectations: is it possible to enrol in—and complete—a doctorate in a regional, rural, or remote location? Is the library sufficient? Are supervisors available? Are professional staff on hand to support the candidature in this location? The exploration of the value of embedded students, supervisors, and locations living in, working in, and contextualizing regional experiences is rare in the literature. Instead, the focus is on health and educational placements from which the student and supervisor leave after the placement is concluded [23,24].

Why is the doctorate important to a university, particularly a regional university? With the leadership of regional universities buffeted by scandals, media attention, financial constraints, under-performance, and research integrity concerns, how can the power and potential of the regional PhD be valued and sustained? There are incredible and inspiring innovations emerging in these locations. As Cuesta-Delgado et al. confirmed, universities have always maintained functions beyond reified teaching and research [25]. These economic and social functions [25] can also be mapped over the diversity of doctoral enrolments that are proliferating. The modes of doctorate are expanding into artefact and exegetical modes, PhDs by Prior Publication, and a widening suite of professional doctorates. Internships and expansive industry partnerships from the experimental sciences to Galleries, Libraries, Archives and Museums (GLAMs) are expanding, alongside the number of doctoral students [26]. Similarly, the sociological configuration of the students is widening, expanding, and transforming. Older students and women are increasing [27]. But also, the PhD has been problematized and weaponized by the Alt-Right. Even Andrew Tate constructed his own version of the PhD: Pimpin’ Hoes Degree [1]. His PhD shadowboxes the changing reality of international doctoral education.

Graduate education is changing. In 2017, and for the first time in the United States, women dominated doctoral programmes. In 2022—and for the first time in Aotearoa/New Zealand—women dominated doctoral programmes. The expansion of health and education research—including midwifery, nursing, social work, early childhood, and further education—has ensured that women are enrolling in doctoral programmes in increasing numbers. This sociological transformation is redefining the methodologies, epistemologies, and ontologies of research [28]. While the regional development research focus has remained on university and industry collaborations in higher education, with a focus on STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics—or Medicine) [29], actually more expansive applications of the word ‘industry’ are required, moving from the creative arts and creative industries, through to the applied social sciences and allied health. Women dominate these disciplines. Without the widening of this discussion, the focus will remain on “technology transfer” [29], rather than expertise development and increasing the complexity, diversity, and stability of the regional workforce and wider population. The narrow and narrowing definitions of “industry” must be monitored and addressed, as shown in a recent systematic review [30]. The regional, rural, and remote (RRR) doctorates remain under-discussed and misplaced in such a time. This is a gendered issue. Heavily dominated by women in allied health and education, the place and positioning of doctorates in regional, rural, and remote locations remain invisible and forgotten. The other key challenge is the silence in the specificity of both the theory and research of supervising higher degree students in regional, rural, and remote locations [31]. So little exists on how to ensure the specific needs and conditions of rural, regional, and remote students are met. Industry partnerships are important, particularly for regional development [32]. So are intellectual standards. But so is the recognition of the proliferation of industries that exist beyond STEM that are crucial to regional locations, including sport, food, education and professional development, tourism, music, and GLAMs.

These alternatives are available if researchers—to cite Chambers—“put the last first” [33]. To conclude my part of the article, I offer four shapes to reconfigure the RRR doctorate. The first is the visualization of a process. PhDs have a beginning, middle, and an end, as shown in Figure 5.

Each stage offers distinct opportunities and disadvantages for connection, community, and communication in regional, rural, and remote communities and doctoral programmes.

As shown in Figure 6, the PhD requires through each stage of enrolment, connection, communication, and community. Atomization and isolation are characteristics of doctoral students, which are intensified if students and supervisors are geographically separated. The third shape, captured in Figure 7, features quadrants with four adjectives that, when combined in different ways, provide the mode and strategy for innovative deterritorialized candidature management, to build a community.

Each of these four squares connects and engages. The key is to align the four quadrants with the architectures of identity for students and supervisors, enabling a relationship to be built. Each quadrant has a specific relationship that configures particular platforms, applications, and behaviours. These relationships can align and disconnect at distinct points of the candidature. Synchronous refers to real-time communication sharing. Asynchronous confirms a delay between one communication event and another. Through the proliferating online environment, analogue has been connoted as that which is not digital, describing physical objects and bodies that continually move outside of digitized, pixilated screens. Digital is the culture, media, and economy founded, developed, and stored through binary numbers. The characteristic of digitization is mobility. Digitally synchronous platforms include Teams and Zoom. Digital asynchronous describes email. Analogue asynchronous is reading a draft chapter on paper. An analogue synchronous is a meeting held in a supervisor’s office.

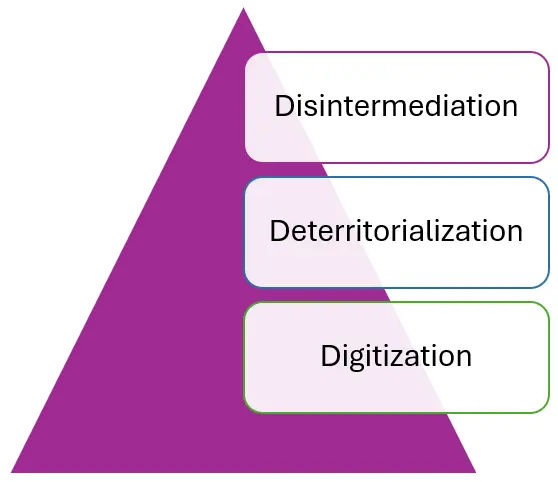

My final shape, shown in Figure 8, is another triangle, titled the 3 Ds: Digitization, deterritorialization, and disintermediation

Disintermediation invokes a flattening of power structures, removing layers in a supply chain. For example, students can follow an academic on Google Scholar and receive alerts to their email address, without the intervention of a librarian. Deterritorialization unhooks a commitment to a singular space and territory to build a shared digital community. If a student is interested in grounded theory, then they can use YouTube content delivered by experienced academics and find universities around the world sharing their resources. Digitization builds new networks of education, entrepreneurship, advocacy, communication, and connection [34,35,36]. New modes of research education are possible.

At the admissions stage, digitization has a profound impact. Students can gather information about supervisors and evaluate their capacity, strengths, and weaknesses before going into the programme. This digital asynchronous searching enables the discovery of an array of information: are supervisors research active? Are they decent human beings? How do they treat their students? Are supervisors able to move students through to completion in the minimum time? With the proliferation of online materials, it is very simple to search for a supervisor and check and recheck the available information.

After a strong supervisory team has been assembled at the admissions stage, a different array of sources and combinations can be configured while progressing through the degree. The candidature itself can be long, complex, convoluted, and difficult. But with attention to three elements of candidature punctuation—meetings, feedback, and milestones—digital and analogue options can be configured to increase the rigour, transparency, and quality of the teaching and learning experience.

The characteristic of students who finish in the minimum time is weekly meetings. The duration is not relevant. The frequency is important. What is significant is that it does not matter if those meetings are analogue or digital. The key is that they are synchronous. A meeting via Teams, Zoom, or Adobe Connect is just as functional and productive as a session in the office. This means that off-campus students can engage in equally effective supervision through weekly, digital, synchronous meetings. The key is the synchronous connection, whether analogue or digital.

If there is a commitment to widening participation, respecting caring responsibilities, and ensuring students in full-time work are supported, then there should be no need for students to attend a specific campus and location. A regional student should not have to travel to the ‘main campus’ for a milestone event. Milestones are a useful andragogical strategy to create transparency and accountability from both students and supervisors, enabling backward mapping. A student can live in Alice Springs and complete a milestone in Adelaide. A student can be in Parkes and complete a milestone in Melbourne. Travel is not required. Family responsibilities are not interrupted. Simple tools like Zoom or Teams enable the synchronous digital delivery of seminars, lectures, and presentations.

Asynchronous digital materials—born digital objects—can also demonstrate achievement and progress and can be uploaded into annual review or milestone documents. These can be videos or podcasts where students, with or without their supervisors, talk through ideas. Further, sonic note-taking is very useful for students who may be in clinical or professional placements—or indeed living their lives—and need to capture at speed an idea digitally for later review.

The doctoral examination is now fully digitized, with theses being sent to examiners in any location in the world connected via the internet. The qualifications and expertise of examiners can be verified, and their reports returned digitally. Therefore, the full capacity of asynchronous digitization is used through examination. As an expertise-driven process, the best examiners anywhere in the world can be deployed, regardless of their location. For students, the speed of delivery and the verification of results are also increased. Similarly, oral examinations can also be conducted via Teams, Adobe Connect, or Zoom. Once more, a deterritorialized process can be implemented. While the thesis can be examined through digital asynchronous means, the oral examination can be conducted through digital synchronous channels.

Digitization gives regional, rural, and remote PhD students power and increases their choices for professional development, and the creation of a bespoke and customized supervisory strategy that is flexible and can change as the students’ circumstances change. A clear example can show how these four shapes can challenge, transform, and transcend acceptable structures and strategies for research education. Writing and writing communities offer a clear example. Shut up and write was a strategy to ensure that graduate students at elite universities could gather in a room, be quiet, and write together [37]. While this project moved online through COVID-19, one author of this article began the Write Bunch in 2016 [38], with the singular aim of unifying doctoral students in and through writing who were geographically dispersed. Regional, rural, and remote students were not an afterthought or an inconvenience. They were the foundational community. Not surprisingly, therefore, regional students dominated this weekly session, including students from Mount Gambier, Tennant Creek, Dubbo, Ballarat, and Alice Springs. This project was extended further through Write Club [39], which provided international community building for students isolated in the Northern Territory. Other options for deterritorialized communication, connection, and community include online reading groups, shared digital events such as Digital Office Hours [40], professional development sessions, and weekly vlogs constructed via the requests of graduate students.

Therefore, using the 3Ds (Digitization, disintermediation, and deterritorialization), students, through diverse stages of their candidature and in diverse locations, could meet, write, and talk. There is no metropolitan centre, no urban core, to disempower other places, research strategies, or people. There is no centre. There is no ‘main campus’. Following on from the innovations of Bell and Jayne [41], a new research agenda can emerge, but with doctoral students at the centre of the project. The goal is not to consider or apply a deficient model of teaching and learning, but an abundance model. Supervisory Professional Development is required [31]. When applying these shapes, supervision transforms so that the outstanding students in the regions, rural and remote environments can live, work, enjoy their families, and pursue a doctorate in their lives, rather than remain marginalized, demeaned, and discarded from the university sector.

The next section of this article summarizes the life, pathways, and trajectories of a PhD student enrolled in a regional location. We answer the call from Melián and Meneses [42] to construct and create spaces for regional, rural, and remote doctoral students to be heard, listened to, and understood. They log—as we have logged in this article—that these students remain “largely understudied and their voices unheard” [42]. This article interrupts the isolation and disrupts the singular focus on regional development and industry partnerships. In the second half of the paper that follows, Matthew Crane discusses how his capabilities were recognized and extended through a robust, considered, and meaningful doctoral program. The power and inspiration of this story capture the value of great supervision, strong professional development, and deep personal connections between students and the support structures that encircle them.

2. What Was Your Pathway into Research and a PhD Programme?

With the drawing of this Love and the voice of this Calling

We shall not cease from exploration

And the end of all our exploring

Will arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time [43].

—T.S. Eliot

My pathway into research and the PhD programme was like arriving where I started, but this time knowing myself, my capabilities, and indeed the university, for the first time. To understand this journey, I offer a narrative exploration of the educational journey that led me to undertake the PhD programme at a regional university.

I grew up in a small town outside a regional centre, and whilst I did not know it then, we were quite poor. My parents were adversely affected by the Global Financial Crisis; they went from running a successful transportation business, which enabled them a comfortable lifestyle, to barely being able to keep up with competing financial demands and the needs of a young family.

My eldest brother had learning challenges, and an emerging understanding of Attention Deficit Disorder (ADD), as it was known, presented my mother with decisions about education, particularly his and my secondary education, that she was perhaps not comfortable or equipped to make. Neither of my parents completed their high school education. Both parents had come from farming families: my mother, who was removed during the Stolen Generation and adopted by a non-Aboriginal farming family near the Murray River, and my father from a share-farming family who regularly moved around rural Victoria in search of work on other people’s farms. The class divide was bridged when my father, a milkman for Kraft, married my mother, who was the daughter of a well-heeled farmer. Education for these National Party voting early high school leavers was not a priority.

Consequently, and despite our firmly “culturally Anglican” (or C of E, as my mother would say) roots, a small Catholic school was chosen since it offered the best one-on-one learning support for my eldest brother. I hated this school because I existed in the shadow of my brother’s problematic behaviour—think of that one “naughty” child who pulled any and every stunt he could to cause trouble (behaviours designed, as we now know, to mask his educational struggles). As a precocious “goodie two-shoes”, I was subjected to regular and vicious bullying because I was nothing like my older brother.

A change in campus within the school brought about a shift in my educational journey. Amongst a new group of peers, I discovered a love of literature, history, and the sociological and anthropological aspects of the Religion & Society curriculum. My teachers saw a spark of curiosity in me and encouraged me to read widely and to express myself through writing, public speaking, debating, and the creative arts.

Despite my parents’ insistence one night when I was in Year 10 that they could no longer afford to pay the school fees, and I would have to go to work with my father, I persevered with my education. I put my uniform on each day without being told to get up, and took myself off to school where I felt safe, supported, and nurtured.

I knew at 15 years of age that education would be my ticket out of that small country town and my often-challenging home environment. I was the first in my family to finish secondary school. To then be offered a place at a university was joyful for me, but confusing for my parents.

I took up the Bachelor of Arts with enthusiasm. New friends, a new capital city context, and new possibilities. Names such as Weber, Durkheim, Foucault, Kant, Lisa Bellear, Peter Carey, Geraldine Brookes, Tony Birch, Chris Wallace Crabbe, and their respective writings entered my consciousness. I planned to finish the BA, do a Dip Ed, and return to my old school as an English teacher.

Instead of committing to study with the same dedication it took to get into university, I worked two jobs and spent far too much time drinking strong black coffee and smoking Marlboro Golds supplied by my new best friend. I failed two units, including Shakespeare, and had to “show cause”—the university’s equivalent of “please explain?”.

This experience coincided with a desire to change degrees. I took the early graduate option and nestled the units I had successfully completed into a diploma, and changed to a Bachelor of Theology. From the Bachelor’s, I completed a Master of Theology and then a Master of Social Work (Qualifying).

Throughout my studies, I often pondered the idea of doctoral research; however I was plagued by self-doubt and a nagging sense that I was not smart enough. Honours had been phased out of the undergraduate theology program, and I was encouraged to complete a research project and minor thesis during the Master of Theology. I had been chipping away at this master’s by coursework degree for six years whilst working full time, so when it came to undertaking research, I was well and truly sick of study. The COVID-19 global pandemic hit, with university campuses and their libraries closed, ushering in a new wave of uncertainty—not just in the world but also in higher education.

The uncertainty of the pandemic and a lack of any clear research ideas led me to undertake a small capstone project and take out the degree without a minor thesis. This seemed to close off any possibility of doctoral studies, but that was okay because I was not smart enough, anyway.

However, at the end of my social work studies, I was interviewing for some sessional teaching work. During that conversation, I was asked if I had considered a PhD. I laughed. “Yes, often!” I replied. The inevitable question followed: “What would you do it in?”. As I began to respond, mumbling something along the lines of not really knowing what I would like to do, I was suddenly hit by an idea. I responded, “power and abuse in the church”.

The job interview set into motion a series of events that quickly became a blur. I had a conversation with an academic at my university with whom I felt there was a great simpatico. That academic was ecstatic to be asked to chat and very enthusiastic about the topic. And that was how it began.

However, there were hurdles that needed to be overcome. I had not written an honours thesis and avoided a master’s minor thesis. I was ineligible for admission to the Doctor of Philosophy.

Fortunately, my university had a clause in the admission criteria that allowed for “honours equivalency”, which my would-be supervisor and the HDR coordinator in our Institute felt could be achieved. This involved submitting a detailed case where I needed to demonstrate the required skills and research experience to undertake independent research at an AQF Level 10 degree.

I applied for the PhD, hastily cobbling together a proposal, submitting a careful table of everything I had done that just might meet the criteria, references from two academics, including my proposed supervisor, offered up a prayer, and pressed submit.

A long wait followed. Questions came from the School of Graduate Research. Responses were sent. More questions and responses. Then silence.

The silence soon abated, when one day in November 2023 I received an email congratulating me on being offered a place in the PhD program, and—to my sheer astonishment—a government scholarship in the form of a stipend, and as if that was not enough, I was also given a scholarship top-up by the University Council.

I read and re-read that email. I read it out loud to myself and to others multiple times. I was sure the university had made a mistake. But no, they assured me, they had not. Despite that little voice in my head that was still telling me that I was “not smart enough”, 15 years after I first attended university—the first in my family, and against all odds—I was enrolling in a doctoral program and thus taking small steps towards fulfilling a dream.

3. You Selected a Regional University for Your Doctoral Programme: Why Did You Make That Decision?

There are two key reasons why I applied to a regional university and ultimately accepted an offer into the doctoral program.

Firstly, the relationship with the university felt right. It was comfortable. I had approached some city-based universities and a regional campus of a metropolitan university much closer to my home, and in each case, there was no flexibility for admission, nor a willingness to take a holistic view of my education and career. To gain admission to those universities, I was required to write a minor thesis through a Graduate Certificate (and pay between $16,000 and $17,000 for the pleasure), and of course, with good reason—my capacity to undertake research at a doctoral level was completely unknown.

An academic friend once said to me that I should “go where the supervisor is”. So, remembering the positive vibe and enthusiasm expressed by my now principal supervisor, I applied to the regional university where I had completed the Master of Social Work, a place where I was well-known and my capacity for further research had been affirmed. I chose the regional university because of the relationships I had built, not only with members of the faculty, but also with library staff, the coffee shop staff, and of course, with my peers. It was easy to accept an offer into the PhD programme because I felt seen as a person, with a unique contribution to make to scholarship.

Secondly, accessibility played an important role in my decision-making. I am not a devotee of working from home. For me to succeed in the PhD, I soon realised that I needed to work away from home, in a scholarly environment for dedicated thinking and writing time. Additionally, I wanted to collaborate with peers and academics face-to-face without the pressure of needing to attend to life at home.

The resources available to higher degree students at the university include the provision of computers and individual workspaces. I have written many thousands of words at my desk on campus because I have been able to focus solely on reading and writing. I have friends at larger, metropolitan universities who must book a “hot-desk” if they want to work on campus. I have been fortunate to be allocated my private office because of the nature of my research.

4. From Your Perspective, What Gifts, Opportunities, and Benefits Does a Regional University Grant a Higher Degree Student?

There are enormous gifts, opportunities, and benefits for students enrolling in higher degree programs at regional universities. Access to one-on-one support, the provision of resources, and the capacity to build relationships across the university have proven to be a significant benefit.

At a small university, I have benefited from the availability of librarians who have extraordinary expertise. They know you and speak with you in the coffee queue. They know what you are researching and ask after your work (and your wellbeing!).

The staff within the Graduate Research School at my university—from the Pro Vice Chancellor, Academics, Dean, HDR Coordinators to the administrative staff—are responsive, accessible, and kind. I recently received a personal apology from the Dean of Graduate Research because she had misread my travel request and asked me to justify the expense of hiring a car interstate for a fieldwork trip. Having realised that I did not plan to drive all the way to Canberra, but was flying, the Dean wrote to apologise for the unnecessary questions. Whilst I did not feel inconvenienced by the need to justify my request, I appreciated that the Dean felt that an apology was necessary. In this way, I am not merely a faceless student number who is relied on for the payment of fees; I am a person who is known by the team and whose research is valued.

The university gives HDR students “associate” status, which provides us with a staff email address and the same access to resources as if we were staff members. This, alongside a computer and dedicated workspaces (not “hot desks”!), represents a generous investment in us as apprentice academics.

My access to my supervision team is also generous and open-hearted. I have heard stories of other students who have never met their supervisors. My principal supervisor and I have developed a warm working relationship, and we meet regularly to discuss my progress.

Within my Institute and discipline, I sense I am regarded as a colleague. I have been fortunate enough to be asked to teach and mark as a sessional academic, which has given me insight into life as an academic. My principal supervisor has initiated conversations about my future direction and actively supports my research and career aspirations.

5. Are There Areas Where You Feel You Have Missed out on What May Be Available in Metropolitan Sectors?

Whilst it may be true, to some extent, that the reputation of the university may matter to some people, this only furthers elitism in academia and the regional-metropolitan divide. I have been on the receiving end of unpleasant comments about undertaking a PhD at a regional university, with the implication that the best research happens within the hallowed halls of Group of Eight universities. In this way, in the eyes of a minority, I perhaps miss out on the implied prestige of graduating from a so-called “sandstone” university. Like buying luxury branded clothes from the charity shop, it is still a luxury item. So it is with the PhD. A PhD is a PhD. I will one day bear the title of “Doctor”, having earned a qualification through my own hard work. There are few things more satisfying than that.

6. Conclusions

Matthew Cane’s voice and views matter. As we conclude this paper, the corresponding author logs a gap in the research literature with consequences for national education policies, and regional and university development. When sourcing material on doctoral education and supervision in these regional, rural, and remote locations, the absence and silence are chilling. The rationale for this article is to ensure that Matthew Crane and all the higher degree students in regional locations are visible, supported, and enabled to make meaningful decisions about their lives, careers, and degrees. This is personally important to me. Both my parents were born and raised in tiny places. Kevin Brabazon, now 97, was born and raised in Northam. Schooling was uneven at best, and a university education was not an option or trajectory. My late mother, Doris Brabazon, spent a slab of her childhood living with her grandparents, John and Mary Ryan. John was a sleeper cutter, and they lived in Bowelling, 30 kilometres from Collie. There were 10 students at her school and one teacher. Today, Bowelling has 84 residents, and no school. University was and is not naturalized as a logical next step in life, education, and employment.

It is not surprising that I committed to these small and resonant places. I want these strong, different, defiant people to have the opportunity for an education, but not a cut-priced experience where their aspirations and ambitions are capped, but offering a parity of quality and expertise with any other university in the world. This goal requires strong, qualified, and engaged leadership, the deployment of open access or free digital resources, and a culture of compassionate followership to avoid the churning of staff. With thoughtful Scholarship of Supervision, applied with care, a student can complete an authentic, organic, empowering, and meaningful PhD on Stewart Island or Arthur’s Press, Kangaroo Island, or Bremer Bay. This is not imposing Auckland, Wellington, Christchurch, Sydney, Canberra, or Melbourne knowledge on RRR locations. Instead, a collaborative space is created—enabled through digitization—where a portfolio of support is available.

At their best, RRR PhDs enable not only the use of Suwala and Micek’s phrase “smart diversification” [44], but also remove the caps on the hopes, aspirations, and goals of students. We also need to ensure that outstanding supervisors are available in Ballarat, Renmark, Dubbo, and Port Hedland. The professional development programmes for supervisors must commence with care and respect for the diversity of students, rather than assumptions about aspirations and trajectories. It is time to park the deficit model of teaching, learning, and supervision. It is time to listen to the voices and views of regional doctoral students and enable learning-led research that enlivens their candidature.

Author Contributions

The conceptualization of the paper was configured by T.B. The theoretical research presented in this article, including regional educational development and andragogical modelling, was developed by T.B. The first part of the article and the conclusion were researched and written by T.B. The second part of the article was written by M.C. Both T.B. and M.C. edited and drafted the entire manuscript.

Ethics Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Funding

This paper received no external funding.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Brabazon T. Shut your cake hole, you over-educated whore: The misogynistic weaponization of the PhD. Fast Capital. 2024, 21, 134–151. doi:10.32855/fcapital.2024.014. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Education. Australian Universities Accord Final Report Document; Department of Education: Canberra, Australia, 2024. Available online: https://www.education.gov.au/australian-universities-accord/resources/final-report (accessed on 30 October 2025). [Google Scholar]

- Brabazon T. Beyond discord and deficit: The failures of regional higher education and revisioning an abundant future. Can. J. Educ. Soc. Stud. 2025, 5, 1–28. doi:10.53103/cjess.v5i4.375. [Google Scholar]

- Pavliuk D, Zhuchkova S. Choosing to succeed? Insights into doctoral students’ supervisor selection and its outcomes. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0328471. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0328471. [Google Scholar]

- Karaduman E, Gürsel-Bilgin G, Caner H, Afacan Fındıklı M, Seggie F. Views of Women Doctoral Students and Dropouts on Doctoral Education in Türkiye. Soc. Incl. 2025, 14, 9828. doi:10.17645/si.9828. [Google Scholar]

- Sekayi D. Expressions of intellectual humility in doctoral education: The role of vulnerability, reciprocal respect, and the adoption of a self-as-learner role. J. Furth. High. Educ. 2025, 49, 1079–1094. doi:10.1080/0309877X.2025.2531116. [Google Scholar]

- DeRonck NG, Stewart TJ. The Importance of Motivation and How to Motivate Doctoral Students in Dissertation Writing. In The Dissertation Research Guide for the Doctoral Scholar; Throne R, Ed.; IGI Global Scientific Publishing: Palmdale, PA, USA, 2026; pp. 161–186. doi:10.4018/978-1-6684-4905-9.ch006. [Google Scholar]

- Brabazon T. Unique Urbanity; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hallinan C, Judd B. Race relations, Indigenous Australia and the social impact of professional Australian football. Sport Soc. 2009, 12, 1220–1235. doi:10.1080/17430430903137910. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson B. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism (Revised and Extended); Verso: London, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- ABS. Remoteness Structure: The Australian Statistical Geography Standard (ASGS) Remoteness Structure; Australian Government: Canberra, Australia, 2016. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/statistical-geography/remoteness-structure (accessed on 30 October 2025). [Google Scholar]

- Hall S, Critcher C, Jefferson T, Clarke J, Roberts B. Policing the Crisis: Mugging, the State, and Law and Order; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson KM, Lichter DT. Rural depopulation: Growth and decline processes over the past century. Rural Sociol. 2019, 84, 3–27. doi:10.1111/ruso.12266. [Google Scholar]

- Maganty A, Byrnes ME, Hamm M, Wasilko R, Sabik LM, Davies BJ, et al. Barriers to rural health care from the provider perspective. Rural. Remote Health 2023, 23, 1–11. doi:10.22605/RRH7769. [Google Scholar]

- Kõlves K, Milner A, McKay K, De Leo D. Suicide in Rural and Remote Areas of Australia; Australian Institute for Suicide Research and Prevention: Brisbane, Australia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Cramer KJ. The Politics of Resentment: Rural Consciousness in Wisconsin and the Rise of Scott Walker; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Cervone JA. Corporatizing Rural Education: Neoliberal Globalization and Reaction in the United States; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Erickcek GA, McKinney HJ. Thinking about the future of small metropolitan areas. Employ. Res. Newsl. 2004, 11, 1. doi:10.17848/1075-8445.11(2)-1. [Google Scholar]

- Birch E, Perry D, Taylor H. Universities as anchor institutions. J. High. Educ. Outreach Engagem. 2013, 17, 7–16. [Google Scholar]

- Borlaug SB, Elken M. Formalising variety: The organisation of universities’ regional engagement and third mission activities. Eur. J. High. Educ. 2024, 14 (Suppl. S1), 10–28. doi:10.1080/21568235.2024.2405555. [Google Scholar]

- Boucher G, Conway C, Van Der Meer E. Tiers of engagement by universities in their region’s development. Reg. Stud. 2003, 37, 887–897. doi:10.1080/0034340032000143896. [Google Scholar]

- Seri P, Compagnucci L. What are university satellite campuses for? A perspective on their contribution to Italian municipalities and regions. Reg. Stud. 2024, 58, 2276–2291. doi:10.1080/00343404.2023.2299282. [Google Scholar]

- Mills J, Francis K, Bonner A. Mentoring, clinical supervision and preceptoring: Clarifying the conceptual definitions for Australian rural nurses. Rural. Remote Health 2005, 5, 1–10. doi:10.22605/RRH410. [Google Scholar]

- Kaden U, Patterson P, Healy J. Updating the role of rural supervision: Perspectives from Alaska. J. Educ. Train. Stud. 2014, 2, 33–43. doi:10.11114/jets.v2i3.364. [Google Scholar]

- Cuesta-Delgado D, Barberá-Tomás D, Marques P. A text-mining analysis of Latin America Universities’ mission statements from a ‘Third Mission’ perspective. Stud. High. Educ. 2025, 50, 1420–1438. doi:10.1080/03075079.2024.2377371. [Google Scholar]

- Bernhard I, Olsson AK. One foot in academia and one in work-life–the case of Swedish industrial PhD students. J. Workplace Learn. 2023, 35, 506–523. doi:10.1108/JWL-11-2022-0157. [Google Scholar]

- Brabazon T, Gribbin E, Sharp C. The stories we tell ourselves about the doctorate and their consequences: Ageing and the PhD. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Educ. Stud. 2023, 10, 1–22. doi:10.23918/ijsses.v10i3p232. [Google Scholar]

- Crimmins G, Casey S. Addressing the binaries of regional/urban and boundaries of research methodologies in and through ‘slow’ research with women from non-urban communities. Qual. Res. 2024, 25, 1282–1299. doi:10.1177/14687941241297390. [Google Scholar]

- Bernhard I, Olsson AK. University-industry collaboration in higher education: Exploring the informing flows framework in industrial PhD education. Informing Sci. 2020, 23, 147. doi:10.28945/4672. [Google Scholar]

- Compagnucci L, Spigarelli F. Industrial doctorates: A systematic literature review and future research agenda. Stud. High. Educ. 2025, 50, 1076–1103. doi:10.1080/03075079.2024.2362407. [Google Scholar]

- Brabazon T. Supervising at a Distance. 2018. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/130264519/Brabazon_Supervising_at_a_distance (accessed on 30 October 2025). [Google Scholar]

- Compagnucci L, Spigarelli F, Perugini F, Iacobucci D. Industrial doctorates for regional development: The case of Le Marche Region. High. Educ. 2024, 1–21. doi:10.1007/s10734-024-01394-9. [Google Scholar]

- Chambers R. Rural Development: Putting the Last First; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Casey S, Crimmins G, Rodriguez Castro L, Holliday P. “We would be dead in the water without our social media!”: Women using entrepreneurial bricolage to mitigate drought impacts in rural Australia. Community Dev. 2022, 53, 196–213. doi:10.1080/15575330.2021.1972017. [Google Scholar]

- Ewart J, Brabazon T. Hope for the hyper-local? Women’s leadership in local news to build regional rural and remote communication and communities. Soc. Hum. Sci. Rev. 2024, 24, 327–348. [Google Scholar]

- Brabazon T, Ewart J. Disruptively regional: How women in Regional, Rural and Remote communities ‘imagine’with and through digital and social media. Smart Cities Reg. Dev. (SCRD) J. 2024, 8, 105–118. doi:10.25019/mpqkpt64. [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell J, Chang R. Building Research Culture Through Shut up and Write. Dr Hidden Curriculum. 2025. Available online: https://drhiddencurriculum.wordpress.com/2025/07/03/building-research-culture-through-shut-up-and-write/ (accessed on 30 October 2025). [Google Scholar]

- Brabazon T, Armstrong E, Baker N, Batchelor S, Brose J, Charlton S, et al. Deeply digital in shallow times: Writing communities in the shadow of the pandemic. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Educ. Stud. 2021, 8, 230–253. doi:10.23918/ijsses.v8i4p230. [Google Scholar]

- Brabazon T. Write Club. Graduate Channel for Charles Darwin University. 2023. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLFnd097NntmbRBhrJVEPJ-yVHYUR1oEO4 (accessed on 30 October 2025). [Google Scholar]

- Brabazon T. Digital Office Hours. Graduate Channel for Charles Darwin University. 2023. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLFnd097NntmbtwAP0pHKqzRa8WrPTQ_8J (accessed on 30 October 2025). [Google Scholar]

- Bell D, Jayne M. Small cities? Towards a research agenda. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2009, 33, 683–699. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2427.2009.00886.x. [Google Scholar]

- Melián E, Meneses J. Alone in the academic ultraperiphery: Online doctoral candidates’ quest to belong, thrive, and succeed. Int. Rev. Res. Open Distrib. Learn. 2024, 25, 114–131. doi:10.19173/irrodl.v25i2.7702. [Google Scholar]

- Eliot TS. Four Quartets; Faber & Faber: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Suwala L, Micek G. Beyond clusters? Field configuration and regional platforming: The Aviation Valley initiative in the Polish Podkarpackie region. Camb. J. Reg. Econ. Soc. 2018, 11, 353–372. doi:10.1093/cjres/rsy010. [Google Scholar]