Leveraging Productivity Analysis for Smallholders’ Sustainable Development: Dairy Efficiency in Central Madagascar’s Crop-Livestock Family Farms

Received: 22 September 2025 Revised: 18 November 2025 Accepted: 17 December 2025 Published: 26 December 2025

© 2025 The authors. This is an open access article under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

1. Introduction

The global milk sector is projected to increase by 20% through 2027, and developing countries can expect to see a significant increase in dairy consumption [1]. In Africa [2], this trend is driven by population growth and urbanization [3]. However, inadequate domestic milk production means that many African countries import milk powder to meet demand [4,5]. There is an opportunity to promote dairy production in developing African countries, presenting a viable path for smallholders’ sustainable development, particularly for the family farms characterizing Africa’s rural landscapes [6].

To that end, this study conducts a development-oriented analysis of smallholder milk production in Madagascar. Livestock productivity has grown worldwide, but more slowly and to a smaller degree in Africa [7], where milk production efficiency is highly variable. In the more developed milk sectors of Ethiopia and Sudan, technical efficiency sits at just 64% and 60%, respectively [8,9]. Nakanwagi and Hyuha [10] estimated Ugandan smallholders’ milk production efficiency at 68%, while producers in Eswatini were found to operate at 78% [11]. In Tanzania, estimates placed productive efficiency at 80% [12], while in Zimbabwe, smallholders produce at only 55% of optimal efficiency [13]. The literature reflects how a range of technical, economic, and social factors influence efficiency in smallholder systems.

This study set out to explore those factors in an African country where productivity analysis of dairy has not previously been applied. It presents the first efficiency analysis of Malagasy smallholder milk production, using stochastic frontier analysis (SFA) to identify farm-level factors influencing productivity and to explore areas of social concern relevant to smallholders’ development. A recent World Bank-funded project1 identified Madagascar’s milk value chain for developmental investment, so the study focuses on milk producers in central Madagascar’s crop-livestock family farms. Section 2 lays out the methods and describes the dataset and regional production context. Section 3 presents the results, and Section 4 discusses the findings and their implications for research-for-development and policy.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Empirical Models of Dairy Production

The study employs stochastic frontier methods to model farm-level technical efficiency among central Madagascar’s milk-producing smallholders. Productivity is a familiar topic in commercial agriculture. Depending on sample size, milk production is usually explained by herd size, labor, sometimes land, and purchased inputs (e.g., concentrates, roughage, veterinary expenses) [14,15]. Inefficiency is variously determined by farmer characteristics, market factors, institutional arrangements, and the adoption of different production practices [8,16,17]. The resource-constrained reality of smallholder production implies that the production function will have few inputs. The farming system is often technically simpler, but milk production still requires cows, feed and/or forage, and labor. Grazing often occurs on common land, and purchased feed may be minimal [18]. Some proportion of milk output may be allocated for home consumption, and labor is generally drawn from the family. Technical inefficiency among smallholders is explained by a variety of factors, including farmer characteristics, extension, and market-related factors [9,11,13]; household size [8]; water availability [10]; and non-cattle income [12].

2.2. Stochastic Frontier Modelling to Measure Technical Efficiency

A stochastic frontier production function is a technique for analyzing the performance of enterprise units. The concept of technical efficiency compares actual output with the output that could be produced in a scenario of optimal efficiency with the same inputs [19]. A parametric stochastic frontier production function uses econometric models to fit a production frontier and identify the factors of technical (in)efficiency relative to that frontier. SFA has been applied across all economic sectors, including agriculture [20,21,22]. Stochastic frontier methods are well-suited for agricultural applications because they incorporate random errors to address the statistical noise of unpredictable external phenomena, such as weather, disease, pests, or economic shocks, as well as measurement errors [23,24].

Aigner et al. [25] and Meeusen and van den Broeck [26] first proposed the stochastic frontier production function as

where Yi is the quantity or value of output of the ith firm, F(۰) is the translog or Cobb-Douglas production function, X is an inputs vector, β is a vector of parameters to be estimated, V is a symmetric random error term, and U is an asymmetric, non-negative random error representing technical inefficiency [20]. Estimates of technical efficiency for individual farms (TE of the ith firm) are obtained by expressing actual output as a proportion of frontier output, per Equation (2).

In order to explain observed efficiency levels, Equation (1) was fitted jointly with Equation (3), where inefficiency is specified as a linear function of a set of farm and farmer characteristics [27].

In Equation (3) above, Z is a vector comprised of a constant and a set of farm-specific explanatory variables, δ is a vector of the inefficiency parameters to be estimated, and W is the unobservable random error (where σU is defined so that Ui ≥ 0). Since Equation (3) captures differences in inefficiency, the δ carries a negative sign to reflect a desirable reduction in inefficiency. The multiplicative Cobb-Douglas functional form is linearized by expressing both sides of the equation in natural logarithms. Both the Cobb-Douglas and translog functional forms were compared using demeaned variables. Referring to the Kodde and Palm critical values, the likelihood ratio (LR) test did not prefer the Cobb-Douglas version over the translog, but the Cobb-Douglas offered a lower Bayesian information criterion (BIC) value. The translog version also contradicted the theoretical expectation that the coefficients on the squares and cross products are jointly equal to zero, so it was decided that the Cobb-Douglas production function better fit the sample.

The production function and inefficiency model were fitted, and post-estimation tests were conducted in Stata/SE 16.1. Experimentation confirmed that a half-normal distribution best fitted this study’s dataset. Efficiency measurement is critically bound to the distribution of one component of the error term, so it is necessary to conduct a series of LR specification tests for goodness-of-fit. For a frontier to exist, restrictions imposed by a mean response model (OLS) must pass an LR test. The normal variance $${\sigma }_{U}^{2}$$ addresses measurement problems, while differences in efficiency are captured by $${\sigma }_{U}^{2}$$. Degrees of freedom in the LR test are equal to the number of restrictions imposed, and the test statistic is $$LR=-2×\left({LLH}_{restricted}-{LLH}_{unrestricted}\right)$$; this test can be used to compare nested specifications. Another batch of LR tests are usually conducted to refine the inefficiency model.

2.3. The Vakinankaratra Context and Dataset

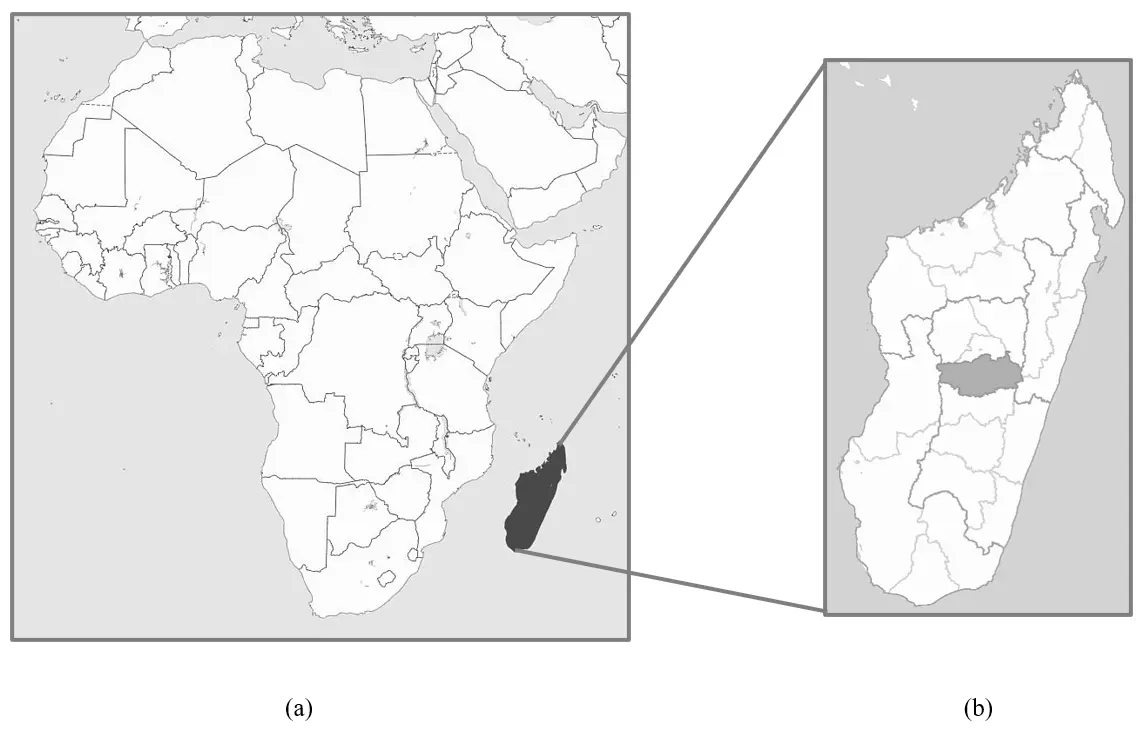

The study focuses on the highlands region of Vakinankaratra, Madagascar. A developing island nation in the southeastern Indian Ocean, Madagascar is populated by some 28 million people [28], the majority of whom live in poverty [29,30]. Nearly three-quarters of the country’s land mass is arable [31], and more than 80% of all Malagasy households are agricultural [32]. The dominant farming system throughout the country is mixed crop-livestock family farming, with most production occurring on >1.5 ha of land (ibid.). Vakinankaratra (see Figure 1) is one of Madagascar’s main agricultural regions, boasting a temperate subtropical climate favorable to staple cereals, market vegetables, deciduous and stone fruits, and livestock [33,34].

In the region’s typical farming systems (see Figure S1), dairy production can contribute to climate adaptation strategies via agroecological intensification and on-farm nutrient recycling [3,35]. Alongside improving farm incomes and reducing poverty, dairy production can also boost food security and children’s health when some milk is retained for household consumption [36]. Given that the dairy industry has more potential for technical progress than other farm commodities [37,38] and that smaller dairies relying on family labor are more efficient than those with hired workers [18], there is real potential for improving smallholder milk production in the region. However, effective interventions targeting African family farms should be shaped by context-specific analyses that holistically evaluate constraints and opportunities [34] to generate quantitative evidence for comprehensive rural development policy [39].

To that end, the study’s sample originates from two farm-level surveys conducted by an established international agricultural research-for-development (AR4D) consortium2. Two-stage sampling was employed in both surveys to represent Vakinankaratra’s agricultural diversity. Regional experts conducted reasoned choice identification of districts and communes. With administrative authorities as witnesses, survey samples of farm households were drawn from electoral lists.

The EcoAfrica project survey3 (N = 405) was conducted in late 2018, and the CASEF Milk Value Chain (CASEF) project survey4 (N = 602) was conducted in early 2019. While each project had its own specific aims, both survey instruments sought to characterize the region’s crop-livestock farms in terms of their socio-economic and technical production factors. The surveys were designed by the same team within the AR4D consortium, with questions consistently framed to ensure the data could be combined and leveraged for analyses beyond those defined by the respective project. The survey instruments were pilot tested and administered by trained, bilingual enumerators in French and Malagasy. The same team captured data in two Access databases, which were audited and validated prior to subsequent analyses. Individual farms were not duplicated across the two surveys. For this study, both databases’ nomenclature was first translated from French to English, then the data were inventoried, common variables identified, and consolidated into a single dataset. Harmonization was substantially supported by the similarity in survey design and data collection methods. From there, it involved ensuring comparability of conceptual definitions, response categories, and measurement approaches. The selection criteria for this study’s sample were: farms located in the region of Vakinankarata, ownership or management of milk cows, milk produced, and only cases categorized as randomly sampled in the originating dataset. The residual sample of n = 147 was suitable for SFA. Farm size and key household characteristics (i.e., age, education level, composition) in the sample were compared to the most recent government census data [32] to ensure the sample’s representativeness for interpreting results later.

The sample includes two cases that do not have cows of their own. They manage one cow each in ‘metayage’, which means they are responsible for managing milk production (i.e., providing shelter, feed, water, and maintaining cow health at their own expense) in exchange for the cow’s milk and sometimes its calves. Those cases were retained since they represent a cultural production practice not uncommon in the region. The sample also contains two outlying cases at the very high end of the regional milk production spectrum. They were retained because their production process does not differ substantially from the rest of the sample, and because the’ level of milk production in those two cases is that to which other farmers aspire. Such volumes were unexceptional in the past when a former President’s regional dairy was thriving.

Descriptive statistics are reported in Table 1. Milk is the number of liters produced per annum (p.a.) from the whole herd. Land use (i.e., usable agricultural area) is reported in 1/100th of a hectare, and herd size is measured as cows in milk. Feed and veterinary expense variables reflect total expenditure on all livestock feed and veterinary services and/or inputs purchased in the prior year, respectively. Due to data irregularities and measurement challenges, it was not possible to accurately parse out cows-only feed expenditures nor calculate precise quantities purchased. The total assets variable reflects the aggregated value of all tangible farm and household goods as a proxy for wealth/poverty.

Total Agricultural Work Units (AWUs) were calculated for the entire farm household based on the age of each household member as follows: age <4 = 0, age 5 to 11 = 0.25 units, age 12 to 14 = 0.5 units, age 15 to 65 = 1.0 units; age >65 = 0.5 units [41]. The labor index, on the other hand, focuses only on the main farmer. It was constructed based on farmers’ reported principal, secondary, and tertiary productive/income-generating activities (both on-farm and off-farm). It represents farmers’ total time investment in on-farm agricultural activities in 25% increments.

The improved breed index reflects the type of cow(s) employed for milk production. The index was constructed as follows: 0 = Zafindraony (indigenous zebu), 1 = Rana (indigenous zebu crossed with 1/16th to 1/8th old French breeds Bordelaise and Jerseyaise), 2 = Demiquart (crossed breed with 1/4th to 1/2 improved breed), 3 = PRN (Norwegian red cows, i.e., specialized dairy breed from Europe).

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of farm-level milk output and inputs (n = 147).

|

Variable |

Units |

Mean |

Std. Dev. |

Coeff. Var. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Milk quantity produced |

liters p.a. |

1244.034 |

2001.875 |

1.609 |

|

Land |

ares a |

84.882 |

105.569 |

1.244 |

|

Cows |

number |

1.694 |

1.162 |

0.686 |

|

Purchased feed |

1000s MGA b |

176,041 |

495,966 |

2.817 |

|

Vet expenses |

1000s MGA b |

10,718 |

13,627 |

1.271 |

|

Total assets |

1000s MGA b |

538,919 |

634,416 |

1.177 |

|

Total AWUs c |

number |

2.721 |

0.451 |

0.498 |

|

Labor index |

1–4 |

3.469 |

0.830 |

0.239 |

|

Improved breed index |

0–3 |

1.145 |

0.924 |

0.807 |

|

Hired labor |

0 = none, 1 = some |

0.068 |

0.253 |

3.714 |

|

Off-farm income |

0 = none, 1 = some |

0.286 |

0.453 |

1.587 |

a 1 are = 1/100th of a hectare; b 1 USD = 4 549 MGA (as of Jan 2024); c Agricultural Work Units.

3. Results

3.1. Establishing the Production Frontier

The frontier was fitted by ‘testing down’ to a Cobb-Douglas production function wherein the quantity of milk produced was specified as a function of cows in milk, purchased feed, farmer’s overall labor investment, and total assets (see Table 2).

The specified frontier was compared to an ‘empty’ version of the production function (i.e., the maximum likelihood optimization) using an LR test of functional form that preferred the specified version (LR chi2(2) = 11.91 with p = 0.003) to the null version.

Table 2. Frontier production function with half-normal distribution (n = 147).

|

Milk Quantity Produced |

Coeff. |

Std. Err. |

Sig. |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Cows |

1.101 |

0.225 |

*** |

|

Purchased feed |

0.031 |

0.011 |

*** |

|

Total assets |

0.176 |

0.072 |

** |

|

Labor index |

0.583 |

0.177 |

*** |

|

constant |

3.450 |

0.912 |

*** |

|

lnsig2v |

−1.656 |

0.376 |

*** |

|

lnsig2u |

0.353 |

0.227 |

|

|

sigma2 |

1.612 |

0.283 |

|

|

lambda |

2.731 |

0.198 |

|

|

Degrees of freedom |

7 |

||

|

Log likelihood |

−177.983 |

*** indicates $$\mathrm{p}\mathrm{r}\mathrm{o}\mathrm{b}\le 0.01$$ and ** indicates $$\mathrm{p}\mathrm{r}\mathrm{o}\mathrm{b}\le 0.05$$.

As expected, milk production is enhanced by feed purchases and asset ownership (i.e., the farm is comparatively better off in terms of capital). Land was left out of the production function because of its detrimental collinearity with herd size and because most Malagasy farmers graze livestock on commonly held pastures, rather than privately owned lands. Multicollinearity was excluded using predictors’ variance inflation factor values, which were below the common threshold of 5.

Summing the coefficients indicates that this Malagasy smallholder milk production system exhibits strongly increasing returns to scale. The 1.891 parameter means that a 10% increase in scale will result in almost 19% more output. This is slightly at odds with the reality that most Malagasy farms produce milk with only one cow, but it accords with the increasing returns to scale found in Greyling et al. [18].

3.2. Specifying the Inefficiency Model

The Vakinankaratra dataset offers some interesting variables for explaining production efficiency, whereas other potentially relevant data were unavailable. Climate data would be useful in this rainfed production context, but unfortunately, the available regional data lacked sufficient granularity for explanatory relevance. Access to extension data was also unavailable. However, the dataset contains demographic variables about the farmer and his/her household, the presence of off-farm income in the household, hiring of external labor, data on access to roads, credit and markets, use of improved dairy breeds, farm altitude, level of integration in the regional “milk zone”, and an index of diversification of crop and livestock production.

Note that detailed correlations can be referenced in the Supplementary Materials. Farmer education is moderately correlated with milk output. Hired labor and farmer membership in an organization are both strongly correlated with milk production. A dummy for the use of an improved cow breed was not correlated with output, but an index reflecting the degree of improvement in the breed is strongly correlated. The farm’s distance to market (proxied by kilometers to the village chief) and its level of integration in the government’s “milk zone” classification are both significantly correlated with milk production. An altitude variable was tested as a proxy for climate differences, but it was uncorrelated with output. The diversification index, which captures the total number of crop types and livestock taxa produced on-farm, was also not correlated with milk production.

The inefficiency model was specified by building complexity one variable at a time, then comparing models after each addition. Model selection was facilitated by conducting LR tests comparing models’ log likelihood values, as well as producing Akaike’s information criteria (AIC) and BIC for further comparison. Given the inherent heterogeneity of the sample’s smallholder farming context, AIC was preferred over BIC in final model selection.

An inefficiency model containing five explanatory variables best fitted the data. When interpreting the results in Table 3, a negative sign on a variable’s coefficient indicates that the variable in question reduces inefficiency and is therefore desirable as an explanatory factor.

Table 3. Stochastic frontier with inefficiency effects (n = 147).

|

Variables |

Coeff. |

Std. Err. |

|---|---|---|

|

Cows |

1.001 *** |

0.199 |

|

Purchased feed |

0.024 ** |

0.010 |

|

Total assets |

0.175 *** |

0.069 |

|

Labor index |

0.469 *** |

0.172 |

|

Improved breed index |

−1.140 *** |

0.280 |

|

Milk zone integration |

−0.951 *** |

0.337 |

|

Years of experience |

0.029 ** |

0.012 |

|

Off-farm income |

0.954 * |

0.490 |

|

Oxen |

0.294 * |

0.153 |

|

Degrees of freedom |

12 |

|

|

Log likelihood |

−159.375 |

|

|

LR test 1 |

49.12 *** |

|

|

LR test 2 |

3.44 * |

|

|

AIC |

342.750 |

|

|

BIC |

378.636 |

*** $$\mathrm{p}\mathrm{r}\mathrm{o}\mathrm{b}\le 0.01$$, ** $$\mathrm{p}\mathrm{r}\mathrm{o}\mathrm{b}\le 0.05$$, and * $$\mathrm{p}\mathrm{r}\mathrm{o}\mathrm{b}\le 0.10$$. 1 The first LR test was conducted using the empty/null model nested in the more complex model considered. 2 The second LR test was conducted using the prior/less complex model nested in the next/more complex model considered.

3.3. Predicting Technical (In)efficiency in Smallholder Milk Production in Vakinankaratra

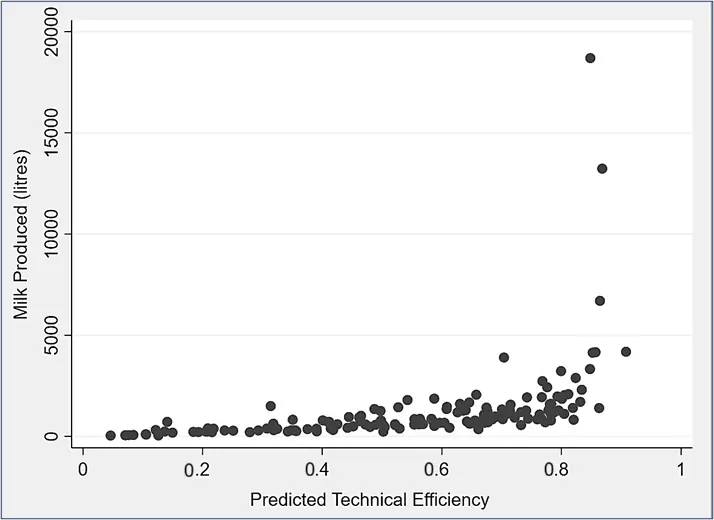

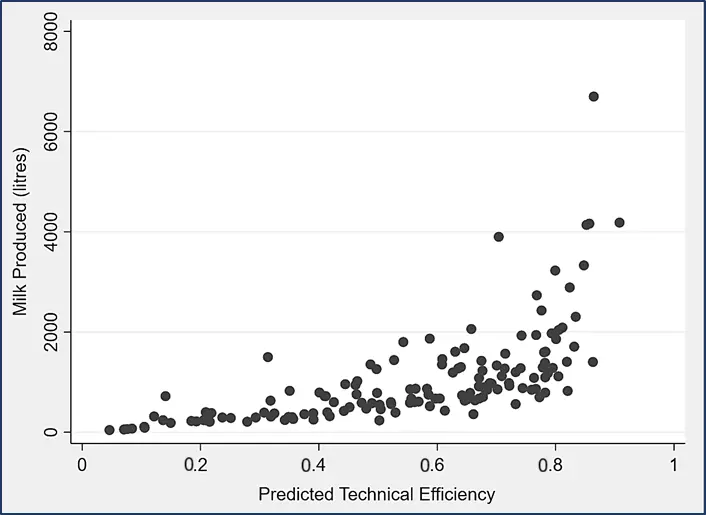

Predicted efficiency levels were generated using the inefficiency model (Figure 2). Technical efficiency across the sample ranged from 4.6% to 90.8% with a mean of 55.5% (std. err. = 0.221).

As mentioned previously, the sample contains two outlying cases at the very high end of milk production. For a more granular illustration of efficiency scores across the rest of the sample, Figure 3 omits the two data points for those outlying cases.

To explore their influence, the two outlying cases were removed from the sample. Excluding them weakened the model substantially (Wald chi2 statistic reduced by 47%; AIC, BIC, and LLH values only improved by 4–5% each). Similarly, the two cases producing milk in metayage were also considered potential influential outliers, however, removing them from the sample also weakened the model. Due to the core sample’s high degree of heterogeneity, model fit was improved by including the full spectrum of production variants, so all four cases were retained.

Of course, Africa’s smallholder production context is characterized by substantial heterogeneity [42]. The regional AR4D consortium has generated evidence typologizing Vakinanakaratra’s farmers, which also evidences this region [43,44]. This study’s results affirm the need to capture as much smallholder heterogeneity as possible in survey samples and to explore the influence of outliers rather than simply omitting them.

Figure 3. Predicted technical efficiency of milk production across the sample, omitting two outlying cases (n = 145).

4. Discussion

4.1. Explaining Farmers’ Deviation from Optimal Efficiency

Labor

Having more cows and providing them with purchased feed are logically significant to farmers’ optimal production. There was no difference in the number of cows between the least and most efficient groups. However, the degree of genetic improvement in the breed used is significant (one-way ANOVA p = 0.000, Bonferroni’s p = 0.000). Purchased feed also differs significantly between groups (one-way ANOVA p = 0.0195, Bonferroni’s p = 0.016). The differences in these categories relate to one another because improved cow breeds do require more and better-quality feed. The dataset’s feed variable represents farmers’ total annual expenditure on all feed types (i.e., hay, green and dry fodder, grains, manioc and taro, maize, composed commercial feed, and feed concentrate). It would be worthwhile to explore which feed types and volumes are most significant to optimal efficiency. That analysis was not possible due to highly variable local measurements in the originating datasets.

Total available household labor (measured in AWUs) was tested in the frontier, but it was not significant, so other labor variables were explored. The labor index, which reflects only the main farmer’s labor, was significant to the production frontier when controlling for other inputs. A high value on the labor index indicates that a farmer is engaged full-time in on-farm production activities, as opposed to having off-farm employment. Its positive and significant coefficient is perhaps counterintuitive to the commonly held assumption that having additional off-farm income is always a good thing for smallholders. Practically speaking, this result means that farmers with off-farm jobs, which absorb time, energy, and management attention, are less efficient milk producers, regardless of any benefits that additional income might offer. Working off-farm also means not being able to supervise others’ labor in real time, ensuring work is carried out properly, and appropriate effort is being invested, particularly by hired labor. This is all relevant for efficient milk production, especially if the farmer has improved breed cows that require more skilled management. This finding is echoed in the inefficiency model, where the presence of off-farm income (presumably) reduces available labor directed at milk production and pulls down efficiency.

The total assets variable captures agricultural equipment (manual and motorized for crop and livestock production), transport assets (carts, bicycles, motorized vehicles), and household electronics (televisions, radios, computers, domestic appliances, telephones). As a proxy, this variable’s significance in the frontier confirms the relevance of wealth/poverty to efficiency in this production context, which is characterized by chronic poverty and constraints on capital. For smallholders, assets are a resource that can be leveraged to raise funds for expansion (e.g., selling equipment to buy another cow). Those assets are also leveraged for decapitalization to cope with shocks (e.g., a family member’s medical treatment, a climate event that destroys a harvest). In this vulnerable context, capital acts as both a lever for intensification and a cash reserve for farm and family emergencies.

Integration in the regional milk zone indicates access to marketing infrastructure, such as collection centers and value-added processing. This variable can also be viewed as a proxy for distance to market, reflecting some farmers’ greater rurality than others. In fact, the least efficient group is on average 4.27 km from the market, while the most efficient group is only 2.43 km away (ANOVA p = 0.012, Bonferroni’s p = 0.053, Wilcoxon rank-sum exact p = 0.050). These results illustrate the importance of rural infrastructure (i.e., roads and a reliably functional cold supply chain) to this production context.

The authors initially hypothesized that the degree of crop-livestock diversification would affect milk production, but the diversification index was insignificant in the frontier and inefficiency models. The number of oxen owned is perhaps a better proxy for diversification since manual traction for cropping is the regional norm. Farmers are unlikely to own oxen not used for that purpose. When tested in the model, the number of oxen was indeed significantly and negatively associated with efficiency. The least efficient farms own 0.69 oxen, while the most efficient have 0.39. As a proxy for diversification, this finding also suggests that the least efficient group is engaged in more crop production than their most efficient peers. Among milk producers in the region’s ubiquitous crop-livestock systems, farmers are making tough choices about how to allocate limited feed between cows and oxen, and they are also dividing management attention and the household’s available productive labor between milk and crop production.

Comparing demographic characteristics fleshes out the sample’s production story further. The least efficient group’s mean farmer age is 49.79 years, while that of the most efficient is 46.43 years. The least efficient farmers have an average of 26.69 years of farming experience, but the most efficient group has only 18.96 years, and this difference is significant (one-way ANOVA p = 0.013, Bonferroni’s p = 0.010). Less experienced, younger farmers in the sample favor efficiency, while more experienced, older farmers are at a disadvantage. This finding aligns with other studies on smallholder dairy where farmers’ advanced age reduced production efficiency [8,13].

Farmers in the least efficient group have, on average, 5.41 years of schooling, while the most efficient have 5.92 years. The difference between groups was not significant for years of education, but when that variable was transformed into classes (0–6 years = low, 7–10 years = mid, 11–12 years = high with one-way ANOVA p = 0.0538) and evaluated in a contingency table, the difference between groups is significant (Fisher’s exact p = 0.027). As with age and experience, this finding echoes evidence in the literature demonstrating the positive relationship between farmer education and improved productivity [8,11].

Mean household size among the least efficient farms is 5.24 members with an average of 2.04 inactive individuals (i.e., small children <5 years, very elderly, sick, or disabled). The most efficient farms have, on average, 4.71 members with only 1.73 inactive individuals. While differences between the groups were not statistically significant, it is relevant that the least efficient farms have larger household sizes overall, with more inactive members. Their dependency ratios are more likely to be unbalanced, which can influence choices about dividing limited household resources and allocating labor to on-farm activities.

Total available household labor (measured as AWUs) did not differ significantly between the least and most efficient groups. However, when decomposed by age categories, AWUs for 12- to 14-year-olds are significantly different between the most and least efficient groups (two-sample Wilcoxon rank-sum exact p = 0.020). The least efficient farms engage 0.107 AWUs from adolescents, while the most efficient only engage 0.043 AWUs from this age group. This means that the least efficient farms use more than twice the adolescent labor than their most efficient counterparts. While these data do not tell us explicitly whether that labor is allocated to milk production, to crop production, or both, the reality on diversified family farms is that available labor is spread across multiple production activities [41]. The authors posit that 12 to 14 years may be the age when families decide whether a child continues with schooling or takes on more farm labor. Perhaps the most efficient farms are better positioned to allow those children to carry on with their education full-time, while the least efficient need more of their available labor.

4.2. Implications for Rural Development Policy and Research

The study’s results illustrate a clear opportunity to improve productivity among the sample’s least efficient dairy farmers, who are producing at only 28.95% efficiency. This group is older with less education, and their households are larger with more inactive members. Farms are more rural, with less access to infrastructure and markets. This group has fewer assets overall and represents more diversified crop-livestock farming systems. The latter two characteristics are key considerations when considering research and policy implications.

The story here is not just a simple econometric tale of more or less efficient milk production. The Malagasy smallholder context is defined by risk-averse diversification, poverty, and vulnerability to shocks. This context shapes nearly all aspects of the farming system. The lines between productive enterprises on-farm are blurry and negotiable when it comes to allocating scarce resources. Limited capital is used as both a lever for intensification and a safety net for surviving shocks. In this context, one must consider productivity not as maximizing output, per se, but in terms of balancing inherent trade-offs and acknowledging the need to protect vulnerable producers [33,34]. In other words, production efficiency must be in equilibrium with farmers’ lived realities.

Use of improved breeds would no doubt improve milk production for the sample’s farmers [45]. Access to credit for enabling the purchase of improved breed cows is one option [46], but the metayage production model could also be considered for farmers whose credit repayment might detract from establishing a solid foundation for intensification. However, the more improved the breed, the more resources it consumes (e.g., water, feed, management attention). A supporting policy package would need to simultaneously address farms’ access to clean water sources and feed inputs. Training programs would also be advisable, and given the study’s findings about off-farm income activities hurting efficiency, perhaps targeting younger, unemployed household members for technical capacity building would be a strategic move. Finally, further research could identify the degree of breed improvement that balances increased milk production with physical hardiness for tolerating heat, water stress, and variable feed mixtures.

The challenges of rurality and farmers’ access to markets and infrastructure are not new, but the study’s findings do reinforce the continued need for investment in rural roadways and electrification to support the milk value chain. As milk production increases, infrastructural investment in value-added processing facilities would further strengthen the sector. It could potentially create more job opportunities, given the established demand for cheese and yogurt in the Malagasy marketplace.

Policymakers should also view family farms’ complex labor scenario through a holistic lens. Family members contribute productive labor that is distributed across multiple on-farm activities, but an individual’s contribution to the labor mix is influenced by factors like age, health status, school attendance, and off-farm employment. At the same time, limited resources must still be divided amongst all household members. Inactive or less active individuals are a drain on overall household resources and productivity and, therefore, likely inhibit intensification. When this scenario is situated within increasing population pressures in Madagascar [47], there are two non-agricultural policy elements that emerge: family planning and health outcomes. Providing context-appropriate family planning services would obviously help to control family size [48,49]. In post-analysis focus groups implemented by the first author5, farmers expressed their awareness of, and concern about, the challenges and implications of having many children. They said they would make use of family planning services if they were free or very low-cost, since the current state offering is beyond their income constraints.

Addressing poor rural health outcomes would also help support family farms’ milk production efficiency and their crop-livestock production more broadly [50]. Dependence on family members’ labor means that if someone falls ill and is unable to work, farm productivity takes an immediate hit. If illness is prolonged or results in disability or death, then that farm’s productivity may never recover. As mentioned previously, health outcomes also relate to decapitalization and a farm’s potential for intensification. There may be no other available source of cash beyond livestock or equipment to buy medicines or pay for hospital or funeral expenses. Those household-level shocks directly impact family farms’ development, particularly when combined with climate and economic vulnerabilities [51]. Delving deeply into rural health policy is beyond the scope of this study, but it is clearly a key component of comprehensively addressing family farms’ production constraints.

Lastly, the negative influence of crop-livestock diversification on milk production must be reconciled with its ubiquity across Madagascar. Family farms buffer against vulnerability by spreading risk and income generation across productive activities. Agricultural households in Vakinankaratra with the highest incomes also have the most diverse crop and livestock activities [52,53]. However, if one accepts this study’s use of oxen as a crude proxy for crop production, then the results reveal that diversification lowers milk production efficiency. While improved manure management within these diversified systems can optimize farm-level resource allocation [35], further research is recommended to model the most dairy-efficient crop-livestock combination(s) to strengthen policy guidance and support developmental outcomes.

Diversification’s influence also extends beyond milk production efficiency. Consider the finding about the least efficient farms’ significantly higher use of adolescent labor. In post-analysis focus groups, farmers confirmed that adolescents are often called upon to provide more labor at this age because they are physically capable and there is little money for/or availability of, hired labor (especially during crop harvests). In addition, they also said that, given scarce resources for school fees, this is the age when parents may stop adolescents’ formal education so younger siblings can begin schooling. This finding speaks to the complex trade-offs between diversified production, labor, and resource allocation on those family farms. It also draws attention to the potential social outcomes influenced by those dynamics: in this case, under-educating children in exchange for their labor when faced with resource constraints. This is particularly relevant for African countries’ development because children’s educational attainment is an indicator of intergenerational mobility and poverty alleviation [54,55].

Future research could model children’s educational attainment in crop-livestock production systems to identify optimal diversification mixtures for efficiency and positive social outcomes. The authors used this study’s findings as the basis for exploratory modeling of educational outcomes among children in the sample [56], further demonstrating how SFA can be strategically leveraged not only to improve farm-level productivity but also for informing broader policy guidance for smallholders’ development.

5. Conclusions

Interventions targeting Africa’s smallholders aim to address widespread poverty and support improved production.AR4D should therefore take a multidisciplinary approach to generating evidence for more comprehensive policy responses like those discussed above. This study’s findings describe how, in the Malagasy dairy context, cows are embedded in diversified crop-livestock family farming systems in which limited resources are allocated across multiple production activities. AR4D that pursues sustainable rural development for these smallholders can start with a narrow focus on a single product and metric—in this case, milk and efficiency. Researchers must then zoom out, consider the social factors influencing production, and use findings to illustrate a more complete picture for policy guidance.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be found at: https://www.sciepublish.com/article/pii/813, Figure S1: Diagram of typical small-scale crop-livestock milk production system in Vakinankaratra, Madagascar; Table S1: Correlations of milk quantity produced with explanatory variables for differences in observed efficiency (n = 147).

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the EcoAfrica and CASEF research teams for their generous access to survey data and for their valuable support throughout analysis and post-analysis validation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.T. and B.C.; Methodology, A.T. and B.C.; Software, A.T.; Validation, A.T. and B.C.; Formal Analysis, A.T. and B.C.; Investigation, A.T.; Resources, A.T.; Data Curation, A.T.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, A.T. and B.C.; Writing—Review & Editing, A.T. and B.C.; Visualization, A.T.; Supervision, B.C.; Project Administration, A.T.; Funding Acquisition, A.T.

Ethics Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The study’s data are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request and pending approval of the AR4D consortium that collected them.

Funding

This work was financed by the FCT—Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, I.P. (Portugal) within the scope of project UIDB/04129/2020 LEAF—Linking Landscape, Environment, Agriculture and Food Research Center, project LA/P/0092/2020 of Associate Laboratory TERRA, and the doctoral research fellowship SFRH/BD/147494/2019 held by PhD Candidate Amy E. Thom.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Footnotes

-

The ‘Croissance Agricole de SÉcurisation Foncière—Hautes Terres’ (CASEF) project (2018 to 2021) was funded by the World Bank and implemented by consultants partnering with government and research-for-development partners. All references to the CASEF project in this article were sourced from unpublished project literature.

-

For more than three decades, Madagascar’s National Center for Applied Research in Rural Development (FOFIFA) and Center for Research and Rural Development in Agriculture and Livestock (FIFAMANOR) have partnered with the French Center for International Cooperation in Agricultural Research for Development (CIRAD) to conduct AR4D in the Vakinankaratra region.

-

Survey methodology was sourced from the EcoAfrica project’s unpublished African Union Grant Application (2016), Interim Narrative Report (2019), and Final Report (2022).

-

CASEF’s survey methodology was sourced from the project’s unpublished 2019 Annual Report and Milk Value Chain Study (2020).

-

Two post-analysis focus groups were conducted in French and Malagasy in July 2022 with a total of 52 crop-livestock dairy farmers purposively drawn from the Vakinankaratra region. The objective was to discuss and validate the study’s results in situ with farmers.

References

-

OECD-FAO. Agricultural Outlook 2018–2027; OECD Editions: Paris, France, 2018. doi:10.1787/agr_outlook-2018-en. [Google Scholar]

-

IFCN. International Farm Comparison Network Dairy Report 2020; IFCN: Kiel, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

-

Vall E. Emergence of Intensive and Agroecological Dairy Farming Systems. Technical Document Produced by the Africa-Milk Project. 2020. Available online: https://www.africa-milk.org/content/download/4516/33229/

version/2/file/Result+1.+Syst%C3%A8mes+de+production+de+lait+vf+ENG-2.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025). [Google Scholar] -

Chatellier V. La planète laitière et la place de l’Afrique de l’Ouest dans la consommation, la production et les échanges de produits laitiers. 3èmes Recontres Internationales “Le LAIT, vecteur de développement”. Dakar: 12–13 Juin 2019. Available online: https://hal.science/hal-02439973/ (accessed on 1 September 2025). [Google Scholar]

-

Merem EC, Twumasi Y, Wesley J, Olagbegi D, Crisler M, Romorno C, et al. The Analysis of Dairy Production and Milk Use in Africa Using GIS. Food Public Health 2022, 12, 14–28. doi:10.5923/j.fph.20221201.03. [Google Scholar]

-

FAO. FAO’s Work on Family Farming: Preparing for the Decade of Family Farming (2019–2028) to Achieve the SDGs; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2018. Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/ca1465en/CA1465EN.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025). [Google Scholar]

-

Acosta A, De los Santos-Montero LA. What is driving livestock total factor productivity change? A persistent and transient efficiency analysis. Glob. Food Secur. 2019, 21, 1–12. doi:10.1016/j.gfs.2019.06.001. [Google Scholar]

-

Girma H. Estimation of technical efficiency of dairy farms in central zone of Tigray National Regional State. Heliyon 2019, 5, e01322. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e01322. [Google Scholar]

-

Hassan S, Abdelaziz H, Ibrahimc A. The Technical Efficiency of Dairy Farms in Sudan: A Stochastic Frontier Approach. GPH-Int. J. Agric. Res. 2018, 1, 1–14. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Abdelateif-Ibrahim/publication/331801561_TECHNICAL_EFFICIENCY_OF_DAIRY_FARMS_IN_SUDAN_A_STOCHASTIC_FRONTIER_APROCH/links/5c8c7e24299bf14e7e7f5371/TECHNICAL-EFFICIENCY-OF-DAIRY-FARMS-IN-SUDAN-A-STOCHASTIC-FRONTIER-APROCH.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025). [Google Scholar]

-

Nakanwagi T, Hyuha T. Technical Efficiency of Milk Producers in Cattle Corridor of Uganda: Kiboga District Case. Mod. Econ. 2015, 6, 846–856. doi:10.4236/me.2015.67079. [Google Scholar]

-

Masuku MB, Sihlongonyane MD. A stochastic frontier approach to technical efficiency analysis of smallholder dairy farmers in Swaziland. J. Econ. Sustain. Dev. 2015, 6, 126–136. [Google Scholar]

-

Bahta S, Omore A, Baker D, Okike I, Gebremedhin B, Wanyoike F. An Analysis of Technical Efficiency in the Presence of Developments Toward Commercialization: Evidence from Tanzania’s Milk Producers. Eur. J. Dev. Res. 2021, 33, 502–525. doi:10.1057/s41287-020-00279-8. [Google Scholar]

-

Masunda S, Chiweshe AR. A stochastic frontier analysis on farm level technical efficiency in Zimbabwe: A case of Marirangwe smallholder dairy farmers. J. Dev. Agric. Econ. 2015, 7, 237–242. doi:10.5897/JDAE2014.0630. [Google Scholar]

-

Náglová Z, Rudinskaya T. Factors Influencing Technical Efficiency in the EU Dairy Farms. Agriculture 2021, 11, 1114. doi:10.3390/agriculture11111114. [Google Scholar]

-

Yilmaz H, Gelaw F, Speelman S. Analysis of technical efficiency in milk production: A cross-sectional study on Turkish dairy farming. Braz. J. Anim. Sci. 2020, 49, e20180308. doi:10.37496/rbz4920180308. [Google Scholar]

-

Yadaveni SA, Patoju SKS. Assessing Technical Efficiency of Cooperative Vis-à-Vis Private Dairy Plants in Andhra Pradesh, India: A Stochastic Frontier Analysis. Indian Econ. J. 2023. doi:10.1177/00194662231207005. [Google Scholar]

-

Yu Z, Liu H, Peng H, Xia Q, Dong X. Production Efficiency of Raw Milk and Its Determinants: Application of Combining Data Envelopment Analysis and Stochastic Frontier Analysis. Agriculture 2023, 13, 370. doi:10.3390/agriculture13020370. [Google Scholar]

-

Greyling JC, Mdluli BB, Conradie B. Farm size and productivity: smallholder dairy production in Eswatini. Agrekon 2023, 62, 49–60. doi:10.1080/03031853.2023.2176896. [Google Scholar]

-

Farrell MJ. The measurement of productive efficiency. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. A Stat. Soc. 1957, 120, 253–281. doi:10.2307/2343100. [Google Scholar]

-

Battese GE, Coelli TJ. Frontier production functions, technical efficiency and panel data: With application to paddy farmers in India. J. Product. Anal. 1992, 3, 153–169. doi:10.1007/BF00158774. [Google Scholar]

-

Conradie B, Genis A. Efficiency of a mixed farming system in a marginal winter rainfall area of the Overberg, South Africa, with implications for thinking about sustainability. Agrekon 2020, 59, 387–400. [Google Scholar]

-

Okoye BC, Abass A, Bachwenkizi B, Asumugha G, Alenkhe B, Ranaivoson R, et al. Differentials in technical efficiency among smallholder cassava farmers in Central Madagascar: A Cobb-Douglas stochastic frontier production approach. Cogent Econ. Financ. 2016, 4, 1143345. doi:10.1080/23322039.2016.1143345. [Google Scholar]

-

Coelli TJ, Rao DSP, Battese GE. An Introduction to Efficiency and Productivity Analysis; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Boston, MA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

-

Nguyen BH, Sickles RC, Zelenyuk V. Efficiency Analysis with Stochastic Frontier Models Using Popular Statistical Softwares; Working Paper Series No. WP09/2021; CEPA (Centre for Efficiency and Productivity Analysis), School of Economics, University of Queensland: Brisbane, Australia, 2021. ISSN No. 1932-4398. [Google Scholar]

-

Aigner D, Lovell CAK, Schmidt P. Formulation and estimation of stochastic frontier production function models. J. Econom. 1977, 6, 21–37. doi:10.1016/0304-4076(77)90052-5. [Google Scholar]

-

Meeusen W, van den Broeck J. Efficiency estimation from Cobb-Douglas production functions with composed error. Int. Econ. Rev. 1977, 18, 435–444. doi:10.2307/2525757. [Google Scholar]

-

Battese GE, Coelli TJ. A model for technical inefficiency effects in a stochastic frontier production function for panel data. Empir. Econ. 1995, 20, 325–332. doi:10.1007/BF01205442. [Google Scholar]

-

UNDESA Population Division. World Population Prospects 2019: Data Booklet; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

-

IMF. Republic of Madagascar: Economic Development Document; Country Report No. 17/225; International Monetary Fund: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

-

World Bank. Poverty & Equity Brief; Africa Eastern & Southern: Madagascar; World Bank Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

-

IFAD. Madagascar. Country Page. 2020. Available online: https://www.ifad.org/en/w/countries/madagascar (accessed on 1 September 2025). [Google Scholar]

-

INSTAT. Troisieme Recensement General de la Population et de l’Habitation. Rapport Thematique sur les Resultats du RGPH-3, Theme 16: Menages Agricoles a Madagascar; INSTAT Madagascar: Antananarivo, Madagascar, 2020. [Google Scholar]

-

Naudin K, Autfray P, Dusserre J, Penot É, Raboin LM, Raharison T, et al. Agroecology in Madagascar: From the plant to the landscape. In The Agroecological Transition of Agricultural Systems in the Global South; Chapter 2; Agricultures et Défis du Monde Collection, AFD, CIRAD; Côte F-X, Poirier-Magona E, Perret S, Rapidel B, Roudier P, Thirion M-C, Eds.; Éditions Quæ: Versailles, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

-

Sourisseau J-M, Bélières J-F, Marzin J, Salgado P, Maraux F. The drivers of agroecology in sub-Saharan Africa: An illustration from the Malagasy Highlands. In The Agroecological Transition of Agricultural Systems in the Global South; Chapter 10; Agricultures et Défis du Monde Collection, AFD, CIRAD; Côte F-X, Poirier-Magona E, Perret S, Rapidel B, Roudier P, Thirion M-C, Eds.; Éditions Quæ: Versailles, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

-

Fanjaniaina ML, Stark F, Ramarovahoaka NP, Rakotoharinaivo JF, Rafolisy T, Salgado P, et al. Nutrient Flows and Balances in Mixed Farming Systems in Madagascar. Sustainability 2022, 14, 984. doi:10.3390/su14020984. [Google Scholar]

-

FAO. Contribution of Terrestrial Animal Source Food to Healthy Diets for Improved Nutrition and Health Outcomes—An Evidence and Policy Overview on the State of Knowledge and Gaps; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2023. Available online: https://openknowledge.fao.org/items/aee31ec6-7641-47ea-80f5-8de49e87e708 (accessed on 1 September 2025). [Google Scholar]

-

Conradie B, Galloway C, Renner A. Private extension delivers productivity growth in pasture-based dairy farming in the Eastern Cape, 2012–2018. Agrekon 2022, 61, 109–120. doi:10.1080/03031853.2022.2063143. [Google Scholar]

-

Vink N, Conradie B, Matthews N. The economics of agricultural productivity in South Africa. Annu. Rev. Resour. Econ. 2022, 14, 131–149. doi:10.1146/annurev-resource-111920-014135. [Google Scholar]

-

Affholder F, Bessou C, Juliette L, Feschet P. Assessment of trade-offs between environmental and socio-economic issues in agroecological systems. In The Agroecological Transition of Agricultural Systems in the Global South; Chapter 12; Agricultures et Défis du Monde Collection, AFD, CIRAD; Côte F-X, Poirier-Magona E, Perret S, Rapidel B, Roudier P, Thirion M-C, Eds.; Éditions Quæ: Versailles, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

-

Sadalmelik. Map of Madagascar with Vakinankaratra Region Highlighted. 2008. Available online: https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=3607410 (accessed on 1 September 2025). [Google Scholar]

-

André P, Delesalle E, Dumas C. Returns to farm child labor in Tanzania. World Dev. 2021, 138, 105818. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105181. [Google Scholar]

-

Vanlauwe B, Coe R, Giller KE. Beyond averages: New approaches to understand heterogeneity and risk of technology success or failure in smallholder farming. Exp. Agric. 2019, 55 (Suppl. S1), 84–106. doi:10.1017/S0014479716000193. [Google Scholar]

-

Andrianantoandro VT, Bélières J-F. L’agriculture familiale malgache entre survie et développement: Organisation des activités, diversification et différenciation des ménages agricoles de la région des Hautes Terres. Tiers Monde 2015, 221, 69–88. doi:10.3917/rtm.221.0069. [Google Scholar]

-

Raharison T, Razafimahatratra HM, Bélières J-F, Autfray P, Audouin S, Muller B. Mieux connaître la diversité des exploitations agricoles et leurs modes de fonctionnement.. un élément indispensable pour orienter les actions de développement. J. de l’Agro-Ecol. 2018, 7, 28–38. Available online: http://agritrop.cirad.fr/594976/1/2019_Journal_de_l%27Agro-ecologie_n%C2%B07_pp27-38.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025). [Google Scholar]

-

Chawala AR, Sanchez-Molano E, Dewhurst RJ, Peters A, Chagunda MGG, Banos G. Breeding strategies for improving smallholder dairy cattle productivity in Sub-Saharan Africa. J. Anim. Breed. Genet. 2021, 138, 668–687. doi:10.1111/jbg.12556. [Google Scholar]

-

Feyissa AA, Senbeta F, Tolera A, Guta DD. Unlocking the potential of smallholder dairy farm: Evidence from the central highland of Ethiopia. J. Agric. Food Res. 2023, 11, 100467. doi:10.1016/j.jafr.2022.100467. [Google Scholar]

-

Bélières J-F, Burnod P, Rasolofo P, Sourisseau J-M. The illusion of abundance: agricultural land issues in the Vakinankaratra region in Madagascar. In A New Emerging Rural World—An Overview of Rural Change in Africa; Pesche D, Losch B, Imbernon J, Eds.; CIRAD: Montpellier, France, 2016. [Google Scholar]

-

Ingutia RA, Sumelius J. Family Planning, Irrigation, and Agricultural Cooperatives for Sustainable Food Security in Kenya. Sustain. Agric. Res. 2024, 13, 16–39. doi:10.5539/sar.v13n2p16. [Google Scholar]

-

Van Hoyweghen K, Bemelmans J, Feyaerts H, Van den Broeck G, Maertens M. Small Family, Happy Family? Fertility Preferences and the Quantity-Quality Trade-Off in Sub-Saharan Africa. Popul. Res. Policy Rev. 2023, 42, 85. doi:10.1007/s11113-023-09828-5. [Google Scholar]

-

Combary O, Traore S. Impacts of Health Services on Agricultural Labor Productivity of Rural Households in Burkina Faso. Agric. Resour. Econ. Rev. 2021, 50, 150–169. doi:10.1017/age.2020.19. [Google Scholar]

-

Ansah IGK, Gardebroek C, Ihle R. Shock interactions, coping strategy choices and household food security. Clim. Dev. 2021, 13, 414–426. doi:10.1080/17565529.2020.1785832. [Google Scholar]

-

Rakotoarisoa J, Bélières J-F, Salgado P. (Eds.) Agricultural Intensification in Madagascar: Public Policies and Pathways of Farms in the Vakinankaratra Region; Summary Report; CIRAD/FOFIFA: Antananarivo, Madagascar, 2016. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/108450324/Agricultural_intensification_in_Madagascar_public_policies_and_pathways_of_farms_in_the_Vakinankaratra_region (accessed on 1 September 2025). [Google Scholar]

-

Razafimahatratra HM, Raharison T, Bélières J-F, Autfray P, Salgado P, Rakotofiringa HZ. Systèmes de Production, Pratiques, Performances et Moyens d’existence des Exploitations Agricoles du Moyen-Ouest du Vakinankaratra. SPAD. 2017. Available online: https://www.dp-spad.org/content/download/4458/33198/version/1/file/2017_SPAD_Description_EA_Moyen+Ouest_VF.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025). [Google Scholar]

-

Alesina A, Hohmann S, Michalopoulos S, Papaioannou E. Intergenerational Mobility in Africa. Econometrica 2021, 89, 1–35. doi:10.3982/ECTA17018. [Google Scholar]

-

Ouedraogo R, Syrichas N. Intergenerational Social Mobility in Africa Since 1920. IMF Working Paper No. 2021/215. 2021. Available online: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2021/08/06/Intergenerational-Social-Mobility-in-Africa-Since-1920-463400 (accessed on 1 September 2025). [Google Scholar]

-

Thom A, Bélières J-F, Conradie B, Salgado P, Vigne M, Fangueiro D. Exploring social indicators in smallholder food systems: Modeling children’s educational outcomes on crop-livestock family farms in Madagascar. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2024, 8, 1356985. doi:10.3389/fsufs.2024.1356985. [Google Scholar]