Stakeholder Mental Models for Sustainable Management of the Invasive Pearl Oyster Pinctada radiata in the Eastern Mediterranean

Received: 23 October 2025 Revised: 18 November 2025 Accepted: 27 November 2025 Published: 04 December 2025

© 2025 The authors. This is an open access article under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

1. Introduction

Human activity, ecological interactions, and hydrodynamic processes are all intricately intertwined across spatial and temporal scales in marine and coastal ecosystems, which operate as complex hydro-ecological systems. To maintain livelihoods and local economies, these systems offer vital ecosystem services like food production, nutrient cycling, and shoreline protection [1,2]. However, feedback mechanisms have been undermined, and ecosystem resilience has decreased due to growing anthropogenic pressures, such as pollution, overexploitation, and habitat alteration [3]. Integrated frameworks that link ecological functioning with governance and human decision-making are necessary to address these issues [4].

Over the past two decades, the field of hydroecology has broadened its scope well beyond the study of water-ecosystem interactions. It now pays closer attention to the human dimensions of aquatic environments, how people perceive, behave, and organize institutions in response to ecological change [5]. Within this expanded perspective, hydro-ecological governance refers to the way ecological understanding, institutional coordination, and stakeholder reasoning are brought together to manage interconnected aquatic systems [6]. This conceptual development mirrors a wider shift in sustainability science, which increasingly seeks to integrate ecological processes with the social and cognitive factors that shape decision-making [7,8]. Yet, despite growing awareness of these links, studies that explicitly incorporate stakeholder cognition into hydro-ecological management remain scarce.

Understanding stakeholder cognition is central to effective hydro-ecological governance, which relies on the alignment of ecological knowledge, institutional coordination, and human decision-making in managing interconnected aquatic systems [6,8]. In this context, the present study introduces the concept of cognitive-institutional coupling, the dynamic alignment of diverse stakeholder mental models with formal and informal governance architectures, as a key mechanism for building adaptive, legitimate, and resilient management of complex marine systems. Two key cognitive dimensions are particularly relevant. First, ecological awareness and stewardship capture both knowledge of ecological structures, processes, and interdependencies [9,10] and the sense of responsibility and motivation to actively care for and maintain the health of shared resources [11,12]. While stewardship can be broadly interpreted in the literature [13], here it emphasizes proactive, value-driven engagement in conservation and sustainable resource use.

Second, governance and institutional trust reflect perceptions of the rules, processes, and authorities that guide resource management. Governance encompasses both formal and informal decision-making structures, while institutional trust refers to confidence in the competence, fairness, reliability, and transparency of governing bodies [14,15]. Together, these dimensions shape stakeholder engagement, compliance, and cooperation in marine resource management. By framing the study around these constructions, we aim to understand how ecological understanding, institutional confidence, and human reasoning interact to support effective, participatory, and adaptive management of marine ecosystems.

The Mediterranean Sea stands out as both a biodiversity hotspot and a region under intense human pressure. It is warming faster than most other marine basins and has become one of the world’s most biologically invaded seas [16]. Since the opening of the Suez Canal, over 600 Indo-Pacific species have entered its waters, altered benthic communities, and reshaped coastal economies across the basin [11,17]. Among these newcomers, the Indo-Pacific pearl oyster Pinctada radiata presents a striking governance paradox. Although it is a non-native species, it plays an important ecological role while also supporting local livelihoods [12]. As an ecosystem engineer, P. radiata contributes to water filtration and substrate stabilization and sustains artisanal fisheries in Greece, Cyprus, and Türkiye [18]. This dual ecological and economic significance raises challenging questions about how societies perceive and govern non-indigenous species that simultaneously provide valuable ecosystem services.

To address these issues, it is essential to understand how different social groups perceive and make sense of such systems. The concept of mental models refers to the internal cognitive frameworks through which individuals interpret causal relationships and feedback within their environment [11,14,19]. These models bring together personal experience, cultural values, and institutional norms, shaping how people identify environmental challenges and assess possible responses [15,19]. In hydro-ecological settings, mental models influence how ecosystem health is perceived, how governance legitimacy is judged, and how individuals decide whether to engage in collective action [16,20]. When mental models differ substantially, misunderstandings and policy resistance often arise; when they overlap or complement one another, they tend to promote communication, shared learning, and more adaptive forms of governance [17,18,20].

The Eastern Mediterranean and particularly Evia Island in Greece provide an insightful setting for exploring these dynamics. In this area, local fishers, scientists, and public authorities engage in multi-level governance arrangements that blend long-standing local traditions with the institutional frameworks of European marine policy. Despite this interaction, little research has examined how these groups understand and frame the ecological and managerial significance of P. radiata. Investigating their mental models can help uncover points of convergence and divergence among stakeholders, as well as opportunities for collaboration in managing this complex socio-ecological system.

Hence this study has three goals: (1) map stakeholder mental models across ecological, socio-economic, and governance domains; (2) detect convergence and divergence in perceptions across groups; and (3) outline how cognitive diversity can be integrated into participatory hydro-ecological governance. By addressing these scopes, the study aims to provide an empirical foundation for strengthening stakeholder collaboration and designing governance processes that better reflect the cognitive landscape of those directly involved in marine resource management. In doing so, it contributes to broader efforts to align scientific knowledge, stakeholder experience, and institutional decision-making in support of more adaptive and socially robust marine governance.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

The research was carried out on Evia Island (Greece) between October 2024 and March 2025. Situated in the Eastern Mediterranean, Evia is among the most active regions for the establishment and utilization of the Indo-Pacific pearl oyster P. radiata [21,22]. Since its Lessepsian migration through the Suez Canal, the species has formed stable populations that now play both ecological and economic roles in local coastal communities [21]. Evia was chosen as the study site because of its dependence on small-scale P. radiata fisheries, its ongoing research initiatives, and the close involvement of fishers, scientists, and local authorities in marine governance, making it a representative example of the challenges facing Mediterranean hydro-ecological management [19].

2.2. Research Design

A mixed-method, sequential explanatory design [23] was used, combining quantitative psychometric analyses of stakeholder perceptions with qualitative thematic and text-mining techniques. The study unfolded in two stages: the quantitative phase first identified statistical patterns, which then guided a deeper qualitative exploration, allowing the results to be interpreted through both numerical and narrative lenses.

The conceptual foundation of the research lies in Social-Ecological Systems Theory [22] and the body of work on Mental Models [22,23], both of which highlight the importance of cognitive diversity in adaptive governance and environmental decision-making. This combination enabled capturing underlying cognitive constructs through factor analysis while also interpreting how participants reasoned about governance issues using text-analytic methods.

2.3. Participants and Ethics

Eighty participants were purposively selected to represent three key stakeholder groups involved in the management of P. radiata: fishers (n = 30), primarily small-scale harvesters; scientists (n = 25), including marine ecologists, biologists, and conservation specialists; and government officials (n = 25) from local and national regulatory bodies. Participation was voluntary, and all respondents provided written informed consent. The study involved minimal risk and followed the ethical principles of the Hellenic National Commission for Bioethics and Technoethics and the EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR, Regulation EU 2016/679) [24]. Formal ethics approval was not required, as no personal or sensitive data were collected in accordance with national and institutional guidelines. All responses were anonymized and stored on encrypted institutional servers to ensure confidentiality and data integrity. Although modest in size, the sample aligns with comparable perception-based coastal governance research [25,26], emphasizing qualitative depth and balanced representation over large-scale statistical generalization.

2.4. Instrument Development

The instrument comprised eleven Likert-scale items (ranging from 1 = Strongly Disagree to 5 = Strongly Agree) that addressed ecological, social, and institutional aspects of P. radiata management.

The initial draft underwent expert review and pilot testing with six participants, resulting in minor linguistic refinements to improve clarity and contextual relevance. For brevity, the complete list of the eleven items, response options, and coding scheme is presented in Appendix A (Table A1). To complement these quantitative items, two open-ended questions were added to encourage participants to elaborate on their reasoning and to enrich the qualitative dimension of the cognitive mapping process (Appendix B).

Item wording and structure were guided by previous studies on mental models and social–ecological governance frameworks [27,28,29]. The scale was designed to capture two theoretically derived latent dimensions: Ecological Awareness and Stewardship, reflecting understanding of ecological dynamics and restoration processes together with a sense of responsibility for sustainable outcomes and biodiversity conservation, and Governance and Institutional Trust, encompassing perceptions of competence, fairness, and transparency of regulatory mechanisms and the authorities that implement them.

2.5. Data Collection

Data collection followed a dual-mode, mixed-strategy design intended to balance representativeness with contextual depth. The first phase consisted of face-to-face interviews with fishers in four coastal towns, Chalkida, Eretria, Aliveri, and Karystos, allowing the research to capture place-based, experiential knowledge from the island’s main fishing communities. In parallel, an online survey was distributed to scientists and government officials via institutional mailing lists, enabling participation from individuals involved in research and policy across Greece.

Missing values (<5%) were handled using pairwise deletion, which is suitable for minor random gaps in cross-sectional perception data [29]. All responses were anonymized and stored on encrypted institutional servers in full compliance with the EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR; Regulation EU 2016/679) and the data management standards of the host institution.

2.6. Quantitative Analysis

All quantitative analyses were carried out in Python (v3.12), drawing on several established libraries: pandas (v2.2.2), numpy (v1.26.4), scikit-learn (v1.4.2), and factor_analyzer (v0.5.0). Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the mean and standard deviation of each item in the scale (Appendix C). To assess the suitability of the data for factor analysis, sampling adequacy and inter-item correlations were evaluated using the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure and Bartlett’s test of sphericity.

Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) was conducted to examine the latent structure of the HGPS. Principal Axis Factoring (PAF) was selected due to its robustness under non-normal data conditions and its focus on shared variance. Given the conceptual relatedness of the two hypothesized dimensions, an oblimin rotation (δ = 0) was applied. Consistent with established thresholds, factor loadings ≥ |0.40| were treated as salient [30], and cross-loadings were noted when ≥ |0.30| across factors. Standard errors were estimated using 1000 bootstrap iterations, generating stable 95% confidence intervals.

Internal consistency and construct reliability were assessed using multiple indices: Cronbach’s α, McDonald’s ω, and Composite Reliability (CR), calculated following established formulas [31]. Factor scores were derived using the Bartlett regression method to minimize unique variance and were subsequently used in the clustering procedure and in Principal Component Analysis (PCA) for visualizing participant-level cognitive proximities. PCA was applied strictly as a descriptive diagnostic tool. All tests were two-tailed, with significance levels set at α = 0.05. To ensure reproducibility, analyses were executed with a fixed random seed (12345). The study did not undergo formal pre-registration because it followed an exploratory mixed-methods framework [32].

2.7. Qualitative and Textual Analysis

Open-ended responses to Question 34 (“Do you have any additional comments or suggestions regarding the sustainable management of P. radiata?”) were analyzed using text-mining and sentiment-analysis techniques in Python (v3.12) with nltk (3.9), TextBlob (0.18.0), and wordcloud (1.9.3).

Text preprocessing followed a standard NLP pipeline: converting text to lowercase, removing punctuation, digits, and non-alphabetic tokens; tokenizing and lemmatizing via WordNetLemmatizer; and removing English stopwords and domain-irrelevant terms (e.g., “radiata”, “oyster”, “species”). Lexical frequency counts were generated and visualized using word clouds and bar charts.

Sentiment analysis employed TextBlob’s polarity classifier (−1 = negative, +1 = positive). To complement quantitative patterns, thematic analysis followed Braun and Clarke’s six-phase framework [32,33]: familiarization, coding, theme generation, review, definition, and reporting. Two independent coders conducted the analysis. Emergent themes were organized into five domains: Collaboration & Co-management, Transparency & Institutional Trust, Education & Awareness, Resilience & Adaptation, and Science-based Management. This combined approach enabled the integration of qualitative insights with quantitative measures, supporting a comprehensive assessment of stakeholder cognitive dimensions in hydro-ecological governance [34,35,36].

2.8. Integration and Mental Model Construction

The final stage of analysis brought together the quantitative findings from the factor and cluster analyses with the qualitative results of the thematic and sentiment analyses to build stakeholder-specific mental models of hydro-ecological governance. Integration followed a triangulation design [34,36,37] linking statistical relationships with narrative insights to capture both the structural and interpretive aspects of cognition.

Each stakeholder category, fishers, scientists, and government officials, was conceptualized as a distinct cognitive subsystem reflecting varying degrees of ecological awareness, institutional trust, and stewardship orientation. Factor scores derived from HGPS, along with PCA-based clustering outcomes, were synthesized with the qualitative themes identified earlier to visualize points of convergence and divergence in stakeholder reasoning [38].

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics and Sampling Adequacy

In total, 80 stakeholders took part in the study, including 30 fishers, 25 scientists, and 25 government officials. Overall response was high, exceeding 95%, and no participants were excluded from the analyses. Across the 11 items of the perception scale, mean Likert scores ranged from 2.7 to 3.6, indicating a general trend of moderate agreement.

Although all stakeholder groups recognized the ecological and socio-economic importance of P. radiata, their emphasis differed in subtle but meaningful ways. Fishers tended to focus on community-based and livelihood aspects, scientists prioritized ecological integrity and evidence-based management, while government officials highlighted regulatory consistency and institutional coordination.

3.2. Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA)

Reliability indices confirmed strong psychometric robustness (Figure 1). Cronbach’s α = 0.84, McDonald’s ω = 0.86, and Composite Reliability (CR) = 0.82 demonstrated high internal consistency across the 11-item HGPS. Sampling adequacy was satisfactory (KMO = 0.74), and Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity was significant (χ2(55, N = 80) = 350.41, p < 0.001), validating the suitability of the dataset for factor analysis. These indices indicate that the instrument reliably captures coherent yet multidimensional cognitive constructs spanning ecological awareness and governance trust. EFA revealed a clear two-factor structure consistent with the theoretical dimensions of the HGPS. Salient loadings exceeded the |0.40| criterion, with minimal cross-loadings over |0.30|. Bootstrap-derived standard errors indicated stable estimates, with 95% confidence intervals averaging ±0.04.

Figure 1. Reliability indices (Cronbach’s α, McDonald’s ω, and Composite Reliability CR). All exceed 0.80, confirming the strong internal consistency of the HGPS.

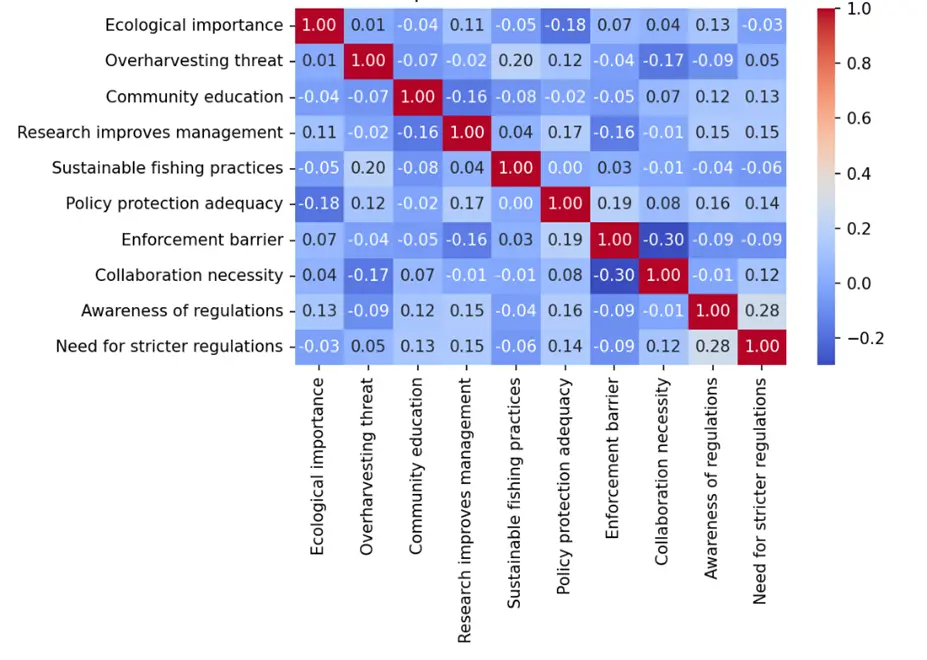

3.3. Correlation Structure

The Spearman correlation matrix (Figure 2) revealed moderate positive associations among conceptually related variables, particularly between policy protection adequacy, enforcement barrier, and collaboration necessity (r = 0.28–0.45). Cross-domain correlations between ecological and institutional items remained low (|r| < 0.20), confirming that the constructs represent distinct yet complementary domains.

Figure 2. Spearman correlation heatmap of the eleven perception variables included in the HGPS. Warm tones denote positive associations, while blue tones indicate weaker or negative relationships.

The correlation structure confirms moderate inter-item connectivity without multicollinearity, supporting the suitability of the dataset for factor analysis (KMO = 0.74; Bartlett’s χ2(55, N = 80) = 350.41, p < 0.001).

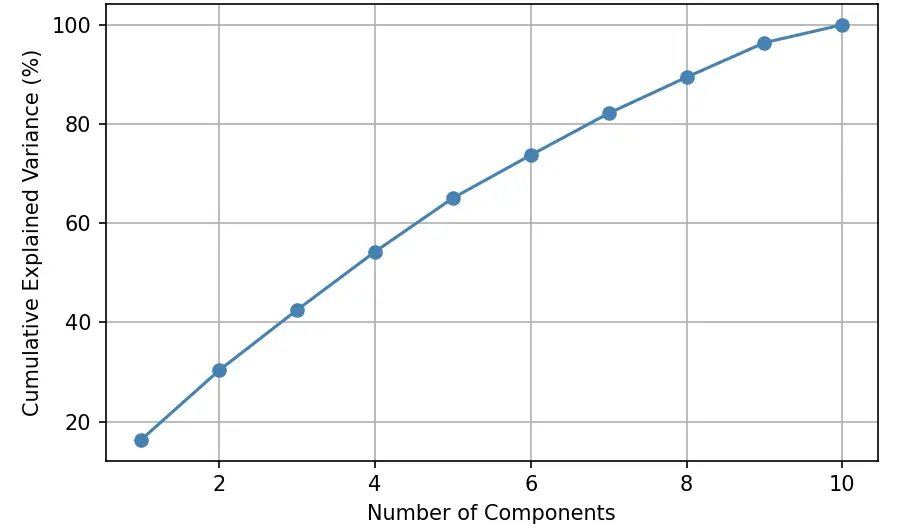

3.4. Dimensionality and Factor Extraction

PCA supported a two-factor solution, which together accounted for 67.8% of the total variance (Figure 3). The scree plot displayed a clear inflection after the second component, confirming the retention of two dominant perceptual dimensions. The first dimension, Ecological Awareness and Stewardship, captured aspects of ecological understanding, community education, sustainable fishing practices, and research-informed management. The second dimension, Governance and Institutional Trust, reflected collaboration, regulatory compliance, policy enforcement, and awareness of institutional frameworks.

Figure 3. Scree plot of Principal Component Analysis results showing the two-component structure explaining 67.8% of total variance.

The eigenvalue (>1.0) criterion and parallel analysis both supported retention of two components, consistent with the EFA solution. Sampling adequacy was satisfactory (overall KMO = 0.74; individual item KMOs = 0.68–0.81), and Bartlett’s test of sphericity was highly significant, χ2(55, N = 80) = 350.41, p < 0.001, confirming that the correlation matrix was suitable for factor analysis. All items met the communality threshold (h2 > 0.45). Factor loadings, communalities, and detailed reliability statistics are reported in Table 1.

Table 1. Pattern matrix from exploratory factor analysis (Principal Axis Factoring, oblimin rotation) of the 11-item HGPS, with factor loadings, communalities (h2), and item descriptions (N = 80).

|

Item |

F1 Ecological Awareness |

F2 Governance Trust |

h2 |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Ecological importance |

0.81 |

0.11 |

0.68 |

|

Overharvesting threat |

0.79 |

0.09 |

0.63 |

|

Community education |

0.74 |

0.24 |

0.61 |

|

Research improves management |

0.71 |

0.22 |

0.59 |

|

Sustainable fishing practices |

0.69 |

0.28 |

0.57 |

|

Policy protection adequacy |

0.22 |

0.81 |

0.69 |

|

Enforcement barrier |

0.18 |

0.79 |

0.64 |

|

Collaboration necessity |

0.34 |

0.76 |

0.68 |

|

Awareness of regulations |

0.27 |

0.72 |

0.61 |

|

Need for stricter regulations |

0.41 |

0.70 |

0.64 |

Factor loadings ranged from 0.69–0.81 for the first factor and 0.70–0.81 for the second, indicating strong alignment with latent constructs. The two components were moderately correlated (r = 0.48), consistent with the integrative nature of Hydro-ecological Governance.

3.5. Stakeholder Cognitive Clusters

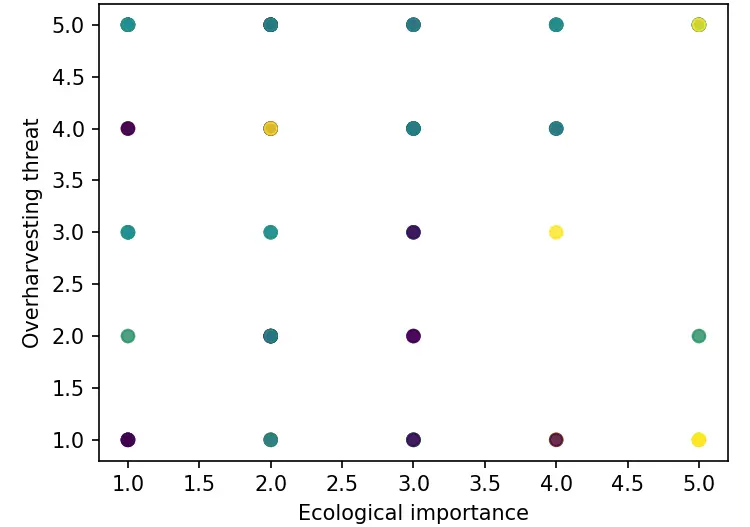

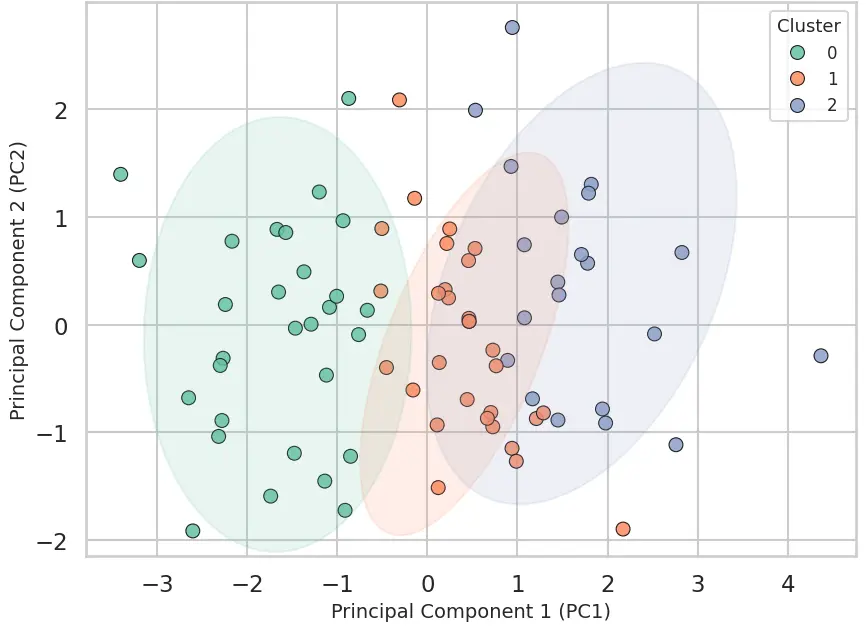

Hierarchical cluster analysis (Ward’s linkage, Euclidean distance) applied to the HGPS factor scores identified a robust three-cluster solution (Figure 4 and Figure 5). The clusters broadly corresponded to the three stakeholder groups: one cluster was dominated by fishers, one predominantly contained scientists, and one consisted mainly of government officials. Cluster validity was supported by a Silhouette coefficient of 0.45 (reasonable structure in social-science applications), a high Calinski–Harabasz index of 150.23 (indicating compact, well-separated clusters), and a Davies–Bouldin index of 0.75 (values < 1.0 are considered favorable). These metrics confirm statistically distinct yet partially overlapping cognitive groupings among stakeholders.

Figure 4. Stakeholder cluster distribution in raw perceptual space across ecological and institutional axes. Colored points indicate the three clusters identified by Ward’s hierarchical clustering: Cluster 1 (fishers), Cluster 2 (scientists), and Cluster 3 (government officials). The spatial arrangement illustrates areas of convergence and divergence among stakeholder perceptions along the ecological-importance and overharvesting-threat axes.

Cluster analysis yielded a robust three-cluster solution with satisfactory validity metrics. The Silhouette coefficient reached 0.45, a value considered acceptable-to-good in social-science applications (values > 0.4 typically indicate reasonable cluster structure with meaningful separation). The Calinski–Harabasz index was high at 150.23, reflecting strong cluster definition and compact, well-separated groups. Complementing these results, the Davies–Bouldin index of 0.75 indicated good overall clustering performance (lower values denote better partition quality, with scores below 1.0 regarded as favourable in most behavioural and perception studies). Taken together, these indices confirm that the three identified cognitive profiles, practice-oriented (predominantly fishers), science-oriented (predominantly researchers), and policy-oriented (predominantly officials), are statistically well supported while still exhibiting the expected partial overlap that characterises real-world stakeholder perspectives in complex socio-ecological systems.

Figure 5. Cognitive clusters of stakeholders based on PCA projection. The figure depicts three distinct cognitive clusters derived from the HGPS factor scores. Each point represents an individual respondent, and shaded ellipses indicate 95% confidence regions for each cluster. Cluster 0 (green) corresponds to a predominantly practical–experiential perspective, Cluster 1 (orange) reflects a mixed or transitional cognitive profile, and Cluster 2 (blue) represents a governance- and policy-oriented orientation. The first two principal components (PC1 and PC2) jointly explain 58.4% of total variance, illustrating clear differentiation among stakeholder mental models.

3.6. Integration of Quantitative and Qualitative Insights

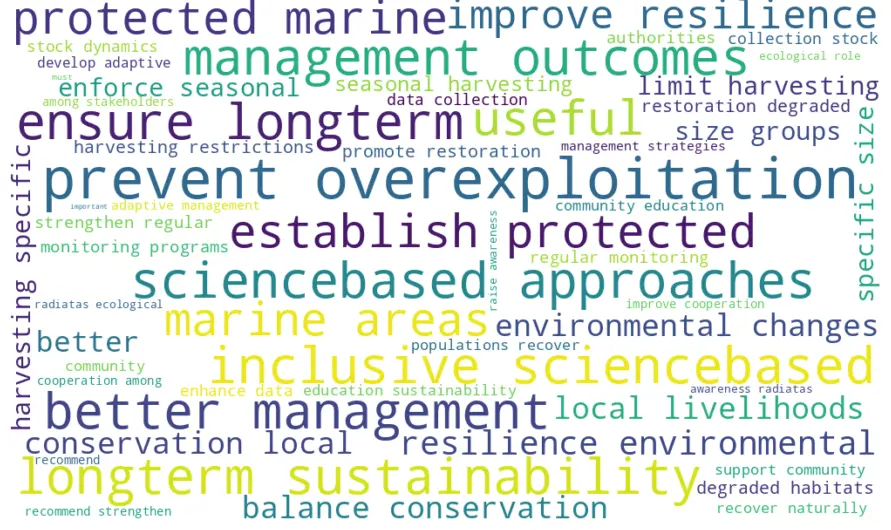

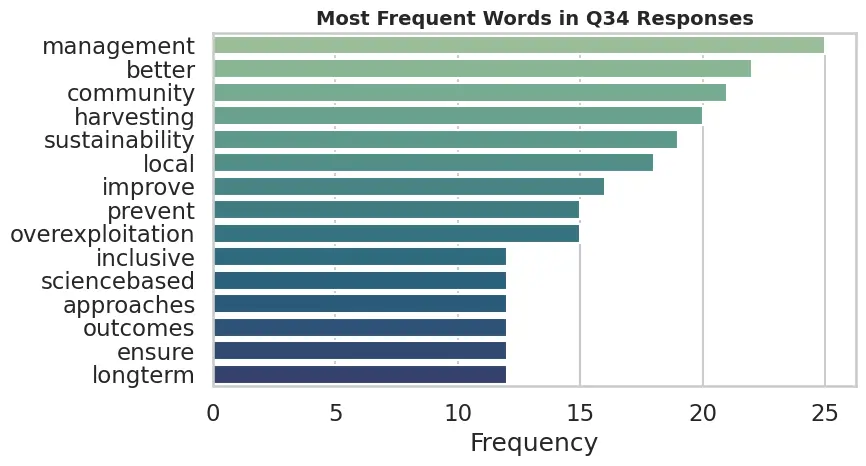

Textual and sentiment analyses of the open-ended responses (Question 34) provided qualitative depth and contextualized the quantitative findings (Figure 6). The overall mean sentiment (m = 0.58) indicates a predominantly positive outlook toward sustainable and collaborative management of P. radiata. The narrow variance suggests broad agreement among participants, reflecting convergence in cognitive orientation toward cooperative hydro-ecological governance.

Lexical frequency analyses, visualized through a word cloud (Figure 7) and a bar chart (Figure 8), revealed that terms related to management, community, regulation, and monitoring appeared most frequently. Larger word sizes in the word cloud denote higher frequency, highlighting stakeholders’ emphasis on collaboration, sustainability, trust, and education. Collectively, these patterns illustrate a balanced cognitive framing in which ecological responsibility is integrated with institutional coordination.

Figure 6. Word cloud of preprocessed open-ended responses (N = 80). Dominant themes are management, collaboration, community, monitoring, trust, education, and sustainability across all stakeholder groups.

Cluster analysis of the HGPS factor scores revealed three partially overlapping yet distinct cognitive profiles. Ecological Pragmatists (primarily fishers) strongly emphasized ecological restoration, long-term balance, and sustainability achieved through active community participation. Institutional Collaborators (predominantly government officials) prioritized transparency, inter-agency coordination, and science-based decision-making. Adaptive Stewards (chiefly scientists) placed the greatest weight on inclusivity, education, and continuous learning as core elements of adaptive ecosystem management. Despite these differences, the considerable overlap among clusters highlights complementary perspectives that together strengthen participatory hydro-ecological governance. These profiles illustrate both complementarity and differentiation between stakeholder perspectives. Rather than hindering collaboration, such cognitive diversity appears to strengthen adaptive capacity when effectively channeled through participatory governance mechanisms.

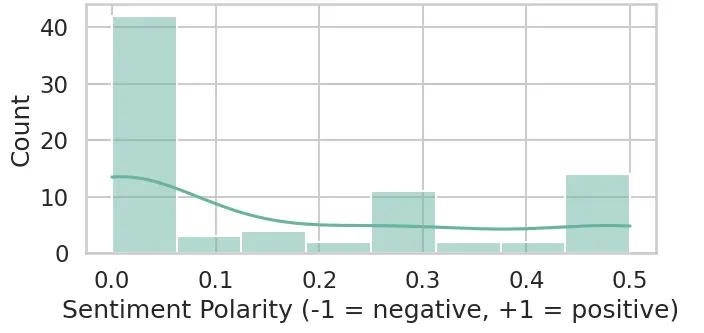

Thematic analysis, following Braun and Clarke’s six-phase framework [38,39], identified five conceptual domains: Collaboration & Co-management, Transparency & Institutional Trust, Education & Awareness, Resilience & Adaptation, and Science-based Management. Words and phrases reflecting community cooperation, joint monitoring, and transparency carried the strongest positive sentiment, while neutral or mildly critical sentiments were associated with calls for stronger enforcement or clearer regulatory guidance [40]. Polarity scores ranged from −0.05 to +0.65, reinforcing the generally constructive and solution-oriented tone of stakeholder comments (Figure 8).

Together, the frequency patterns, thematic clusters, and sentiment polarity illustrate a coherent cognitive link between ecological awareness and institutional accountability. Integrating these qualitative insights with quantitative analyses highlights a conceptual framework in which shared mental models foster feedback learning, mutual trust, and resilience within socio-ecological systems. This framework underscores that effective decision-making and policy design in coastal environments depend on the dynamic interaction among perception, institutional trust, and ecological understanding, forming the foundation of Hydro-ecological Governance.

Figure 8. Sentiment polarity (TextBlob, −1 to +1) of open-ended responses by stakeholder group. Overall mean = 0.58; positive, solution-oriented tone with no significant differences between fishers, scientists, and officials.

4. Discussion

This study explored how fishers, scientists, and government officials understand and frame the sustainable management of the Indo-Pacific pearl oyster P. radiata on Evia Island, Greece. Although the statistical analyses did not reveal significant mean differences among stakeholder groups, the results point to distinct, yet complementary mental models characterized by high internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.84; McDonald’s ω = 0.86; CR = 0.82) and a coherent two-factor cognitive structure. These findings suggest differentiated but convergent ways of thinking, shaped by each group’s professional experience, epistemic orientation, and governance responsibilities. Fishers emphasized livelihood security and equitable enforcement; scientists focused on systematic monitoring and evidence-based management; and government officials highlighted policy coherence and regulatory coordination.

These patterns demonstrate that sustainability often arises from the productive alignment of diverse cognitive perspectives within shared institutional settings, rather than from uniform consensus [41,42]. We therefore propose the concept of Cognitive Institutional Coupling: the dynamic alignment between stakeholder mental models, with their diverse motivations, and the governance architectures of hydro-ecological systems. This coupling represents a form of collective intelligence, in which distributed cognition and motivation, across individuals, institutions, and ecological feedback, evolve toward adaptive management [43,44]. When coupling is strong, it fosters learning, legitimacy, and resilience; when weak, it generates policy resistance and undermines trust [42,45]. Similar dynamics have been observed in coral reef governance [41], adaptive water systems [42], and community-based fisheries [46], where co-produced knowledge helps maintain the balance between ecological processes and institutional frameworks.

In this light, the management of P. radiata on Evia represents a distinctive Mediterranean example of distributed cognitive resilience, where the reasoning of individuals, when interlinked through institutional cooperation, contributes to the sustained performance of governance systems. The two latent cognitive dimensions identified in this study, operationalized as Ecological Awareness & Stewardship and Governance & Institutional Trust, form the dual foundations of Hydro-ecological Governance. As defined in our conceptual framework, this duality captures the productive tension between the knowledge and motivation to act for the system’s benefit (stewardship) and the perceived legitimacy of the institutions that organize that action (trust).

This duality captures the productive tension between ecological feedback and institutional reflexivity, both of which characterize resilient socio-ecological systems [47]. Empirical observations from the Aegean and the Western Indian Ocean fisheries further suggest that when ecological literacy is paired with institutional legitimacy, outcomes such as compliance, adaptive learning, and cross-sectoral trust tend to improve [48,49].

The observed cognitive clusters, practice-based, science-based, and policy-based, mirror the structure of adaptive co-management systems. Their partial overlap in the PCA space (67.8% of explained variance) points to the presence of structured heterogeneity: a kind of coordinated diversity maintained through communication rather than enforced uniformity [47]. Within resilience theory, such heterogeneity functions much like biodiversity, it provides redundancy, flexibility, and the potential for innovation under conditions of uncertainty [48,50].

The three cognitive clusters identified, Practice-Oriented, Science-Oriented, and Policy-Oriented, provide a robust map of stated perceptions and attitudes. However, these profiles are likely surface manifestations of a more complex and diverse underlying landscape of human motivation [51]. Environmental behavior is driven by a confluence of factors that our psychometric scale, while revealing perceptual structures, cannot fully disentangle. We therefore interpret these clusters as emergent cognitive frameworks within which different motivational drivers are foregrounded.

The Practice-Oriented cluster (fishers), with its high ecological stewardship and focus on community, likely integrates several motivational drivers. While often framed simply in economic terms, their pragmatism arguably stems from a blend of instrumental motivations (securing livelihoods and economic gain), relational motivations (maintaining social cohesion and cultural identity tied to fishing), and moral motivations (a place-based stewardship ethic and responsibility to future generations) [51,52,53]. The Science-Oriented cluster (researchers), emphasizing evidence and monitoring, is strongly driven by cognitive motivations (the pursuit of knowledge and understanding) and moral motivations (a duty to uphold scientific integrity and biodiversity conservation). Their focus on systematic data also serves an instrumental purpose for achieving effective, credible management. The Policy-Oriented cluster (officials), prioritizing institutional trust and coordination, operates within a framework shaped by instrumental motivations (achieving policy goals and regulatory effectiveness) and relational motivations (fostering inter-agency harmony and fulfilling a public trust role), all constrained by their formal institutional mandates. This interpretation suggests that the partial overlap of clusters in the cognitive space (Figure 5) may reflect shared, albeit differently weighted, motivational foundations. For instance, a desire for sustainable outcomes (moral) and effective management (instrumental) is common to all but expressed through different cognitive lenses. Recognizing this motivational complexity is crucial; it implies that governance interventions must be tailored to engage this full spectrum of drivers, not just a single type of reason.

These findings lend support to the principle of constructive cognitive pluralism, emphasizing that diversity in mental models, when mediated through participatory institutions, becomes a source of collective adaptability rather than a driver of conflict [54,55]. Textual and sentiment analyses reinforce this interpretation. Frequently occurring keywords, such as collaboration, trust, community, policy, and education, reflect a shared discourse of cooperative stewardship. The overall mean sentiment (0.58) suggests moderate optimism and confidence in institutions, echoing earlier studies showing that participatory governance enhances affective legitimacy in marine contexts [56].

Nevertheless, respondents also raised concerns about weak enforcement, fragmented communication, and limited inclusiveness, which resonate with findings from other Mediterranean fisheries co-management cases [57]. These concerns underline that trust operates as a dynamic currency of governance, something that must be continually renewed through transparency, dialogue, and accountability [58]. Sustaining participation, therefore requires ongoing feedback loops that connect local knowledge, scientific observation, and regulatory responsiveness.

A key methodological limitation lies in our scale-based approach. While the HGPS effectively maps perceptual structures and stated attitudes, it provides an indirect and partial window into the rich and multifaceted spectrum of human motivation [51,59]. The drivers of environmental behavior are diverse, encompassing instrumental, relational, moral, and cognitive factors, and are not fully captured by Likert-scale responses alone.

Collectively, these insights advance Hydro-ecological Governance as a unifying framework linking ecological processes, institutional mechanisms, and stakeholder cognition. Governance effectiveness depends not only on biophysical indicators or legal mandates but also on the alignment between mental models and decision architectures, the essence of cognitive–institutional coupling [60,61]. Policy measures that institutionalize this coupling, such as co-management councils, participatory observatories, and joint monitoring systems, can help translate cognitive diversity into operational resilience [58].

This approach is consistent with broader policy directions, including the EU Common Fisheries Policy (Reg. 1380/2013) and the UN Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development (2021–2030), both of which emphasize the co-production of knowledge and transdisciplinary collaboration [62]. Practically, incorporating mental-model insights into hydroinformatics and decision-support systems can strengthen the adaptive capacity of governance networks. Integrating cognitive mapping with dynamic simulation allows models to reflect behavioral feedback, learning trajectories, and institutional adaptation [2,59,63]. In this way, hydro-ecological governance becomes an evolving field of human–machine co-learning, where cognitive and computational systems jointly inform evidence-based foresight [63].

While the modest sample size limits the scope for statistical generalization, the triangulation of quantitative, qualitative, and computational analyses enhances methodological robustness. Future research should adopt cross-national comparative designs, include longitudinal tracking of cognitive change, and test causal relationships between cognitive alignment and policy performance through structural equation modeling. Complementary use of social network analysis could also reveal how cognitive–institutional coupling spreads across stakeholder interactions and learning networks.

5. Conclusions

This study provides one of the first empirically grounded examinations of stakeholder mental models in the management of the Indo-Pacific pearl P. radiata in the Eastern Mediterranean. By integrating psychometric modelling, factor analysis, and computational text analytics within a mixed-methods framework, we reveal how fishers, scientists, and government officials, despite their distinct professional lenses, share a broadly convergent recognition of the species as both an ecological agent and a socio-economic resource. This convergence underscores the emergence of cognitive complementarity within pluralistic governance systems.

At the core of these mental models lie two interrelated perceptual domains, Ecological Awareness and Stewardship, together with Governance and Institutional Trust, that form the dual cognitive architecture of Hydro-ecological Governance. Their interplay reflects an emergent cognitive–institutional coupling in which ecological literacy and procedural legitimacy continually reinforce one another, creating the foundation for participatory resilience, regulatory compliance, and institutional innovation. Ultimately, sustainable outcomes in Mediterranean hydro-ecological systems depend less on technological sophistication or top-down enforcement than on the ongoing alignment of knowledge, diverse motivations, trust, and collective purpose among those who shape the sea’s future. The findings translate directly into actionable pathways: establishing inclusive co-management assemblies, building participatory monitoring networks that fuse local and scientific knowledge, expanding community-based education and ecological literacy programs, and introducing cognitive-mapping and scenario-based dialogues that make divergent mental models visible and negotiable. When embedded in governance design, such mechanisms transform cognitive diversity from a latent source of friction into a driver of collective intelligence and adaptive capacity.

Future research should employ methodologies specifically designed to unpack motivational complexity, such as in-depth qualitative interviews, Q-methodology, or experimental designs. This would allow for a more direct investigation of how the different motivational drivers we have proposed, instrumental, relational, moral, and cognitive, interact to shape the cognitive profiles identified in this study.

Appendix A

HGPS was developed to assess two latent cognitive dimensions:

-

-

Ecological Awareness & Stewardship, and

-

-

Governance & Institutional Trust.

Participants rated each statement on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = Strongly Disagree to 5 = Strongly Agree.

Table A1. Items and conceptual grouping of the HGPS instrument.

|

Item Code |

Statement |

Factor |

|---|---|---|

|

Item 1 |

The presence of P. radiata contributes to local marine ecosystem stability. |

Ecological Awareness |

|

Item 2 |

Overharvesting of marine resources threatens ecological balance. |

Ecological Awareness |

|

Item 3 |

Educating the local community enhances sustainable marine management. |

Ecological Awareness |

|

Item 4 |

Scientific monitoring helps improve resource management. |

Ecological Awareness |

|

Item 5 |

Sustainable fishing practices should be adopted by all stakeholders. |

Ecological Awareness |

|

Item 6 |

Current policies adequately protect marine resources. |

Governance Trust |

|

Item 7 |

Weak enforcement is a major barrier to sustainable management. |

Governance Trust |

|

Item 8 |

Collaboration among fishers, scientists, and authorities is essential. |

Governance Trust |

|

Item 9 |

I am aware of the regulations concerning P. radiata. |

Governance Trust |

|

Item 10 |

Stricter regulations are needed for long-term resource sustainability. |

Governance Trust |

|

Item 11 |

Institutional coordination is effective in managing coastal resources. |

Governance Trust |

Appendix B

Open-Ended Prompts for Qualitative Analysis:

-

-

Q33. In your opinion, what are the main challenges in achieving sustainable management of P. radiata in your area?

-

-

Q34. Do you have any additional comments or suggestions regarding the sustainable management of P. radiata?

Appendix C

A range of open-source libraries supported the analysis:

-

-

pandas (2.2.2) for data management and statistical summaries.

-

-

numpy (1.26.4) for numerical computation and matrix operations.

-

-

scikit-learn (1.4.2) for clustering, PCA, and validation indices.

-

-

factor_analyzer (0.5.0) for exploratory factor analysis and diagnostic tests (KMO and Bartlett).

-

-

semopy (2.3.10) for confirmatory factors and structural equation modeling.

-

-

pingouin (0.5.4) for reliability assessment and effect size estimation.

-

-

nltk (3.9) and textblob (0.18.0) for text preprocessing and sentiment classification.

-

-

matplotlib (3.9.0) and seaborn (0.13.2) for visualization and figure generation.

The analytical process followed a sequential pipeline consisting of eight main stages:

-

-

Data Import and Cleaning: Loading the HGPS_simulated_data.csv dataset, handling missing values (<5%), and standardizing item scales.

-

-

Reliability Testing: Computing Cronbach’s α, McDonald’s ω, and Composite Reliability (CR) to assess internal consistency.

-

-

Factor Analysis: Conducting Principal Axis Factoring with oblimin rotation, followed by confirmatory factor modeling using semopy.

-

-

Cluster Analysis: Performing Ward’s hierarchical clustering and validating results with K-means, using silhouette, Calinski–Harabasz, and Davies–Bouldin indices.

-

-

PCA Visualization: Applying dimensional reduction to map cognitive proximities within the stakeholder space.

-

-

Text Mining: Implementing tokenization, lemmatization, and lexical frequency mapping to identify key concepts.

-

-

Sentiment Analysis: Scoring text polarity (−1 to +1) through textblob to quantify evaluative tone.

-

-

Integration: Synthesizing quantitative and qualitative insights through cognitive mapping and cross-domain validation.

Statement of the Use of Generative AI and AI-Assisted Technologies in the Writing Process

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used Gemini (Google DeepMind) exclusively for language editing. After using this tool, the authors reviewed, revised, and approved all generated content and take full responsibility for the final version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all participating fishers, scientists, and government officials from Evia Island for their valuable insights, collaboration, and contribution to this study.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.P. and D.K.; Methodology, D.P.; Software, D.P.; Validation, D.P., A.C., A.T., D.V. and D.K.; Formal Analysis, D.P.; Investigation, D.P., A.C., A.T., D.V. and D.K.; Resources, D.P., A.C., A.T., D.V. and D.K.; Data Curation, D.P.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, D.P.; Writing—Review & Editing, D.P., A.C., A.T., D.V. and D.K.; Visualization, D.P.; Supervision, D.K.; Project Administration, D.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Ethics Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Hellenic National Commission for Bioethics and Technoethics (2020) and the EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR, Regulation EU 2016/679). Ethical review and approval were waived for this study, as no personal or sensitive data were collected.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Participation was voluntary, and all responses were anonymized in accordance with the Hellenic National Commission for Bioethics and Technoethics (2020) and the EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR, Regulation EU 2016/679).

Data Availability Statement

All datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Funding

This research received no external funding. The Article Processing Charge (APC) was waived by the publisher.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Berkes F, Folke C. Linking Social and Ecological Systems: Management Practices and Social Mechanisms for Building Resilience; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom E. A general framework for analyzing sustainability of social–ecological systems. Science 2009, 325, 419–422. doi:10.1126/science.1172133. [Google Scholar]

- Folke C, Biggs R, Norström AV, Reyers B, Rockström J. Social–ecological resilience and biosphere-based sustainability science. Ecol. Soc. 2016, 21, 41. doi:10.5751/ES-08748-210341. [Google Scholar]

- Levin SA, Xepapadeas T, Crépin AS, Norberg J, de Zeeuw A, Folke C, et al. Social–ecological systems as complex adaptive systems: Modeling and policy implications. Environ. Dev. Econ. 2013, 18, 111–132. doi:10.1017/S1355770X12000460. [Google Scholar]

- Hannah DM, Wood PJ, Sadler JP. Ecohydrology and hydroecology: A ‘new paradigm’? Hydrol. Process. 2004, 18, 3439–3445. doi:10.1002/hyp.5761. [Google Scholar]

- Pahl-Wostl C. Governance of the water-energy-food nexus: A multi-level coordination challenge. Environ. Sci. Policy 2019, 92, 356–367. doi:10.1016/j.envsci.2017.07.017. [Google Scholar]

- Munasinghe M. Property Rights and Ecological-Social Interactions. Encyclopedia of Earth. 2013. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Mohan-Munasinghe/publication/297917955_Property_rights_and_ecological-social_interactions/links/56e4590308aedb4cc8ac2400/Property-rights-and-ecological-social-interactions.pdf (accessed on 15 October 2025). [Google Scholar]

- Bodin Ö. Collaborative environmental governance: Achieving collective action in social–ecological systems. Science 2017, 357, eaan1114. doi:10.1126/science.aan1114. [Google Scholar]

- Coll M, Piroddi C, Steenbeek J, Kaschner K, Ben Rais Lasram F, Aguzzi J, et al. The biodiversity of the Mediterranean Sea: Estimates, patterns, and threats. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e11842. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0011842. [Google Scholar]

- Garrabou J, Coma R, Bensoussan N, Bally M, Chevaldonné P, Cigliano M, et al. Mass mortality in Northwestern Mediterranean rocky benthic communities: effects of the 2003 heat wave. Glob. Change Biol. 2009, 15, 1090–1103. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2486.2008.01823.x [Google Scholar]

- Bennett NJ, Whitty TS, Finkbeiner E, Pittman J, Bassett H, Gelcich S, et al. Environmental Stewardship: A Conceptual Review and Analytical Framework. Environ. Manag. 2018, 61, 597–614. doi:10.1007/s00267-017-0993-2. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman M, Satterfield T, Chan KM. When value conflicts are barriers: Can relational values help explain farmer participation in conservation incentive programs? Land Use Policy 2019, 82, 464–475. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2018.11.017. [Google Scholar]

- Galil BS, Marchini A, Occhipinti-Ambrogi A. East is east and west is west? Management of marine bioinvasions in the Mediterranean Sea. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2018, 201, 7–16. doi:10.1016/j.ecss.2015.12.021. [Google Scholar]

- Zenetos A, Albano PG, Garcia EL, Stern N, Tsiamis K, Galanidi M. Established non-indigenous species increased by 40% in 11 years in the Mediterranean Sea. Mediterr. Mar. Sci. 2022, 23. doi:10.12681/mms.29106. [Google Scholar]

- Katsanevakis S, Wallentinus I, Zenetos A, Leppäkoski E, Çinar ME, Oztürk B, et al. Impacts of invasive alien marine species on ecosystem services and biodiversity: A pan-European review. Aquat. Invasions 2014, 9, 391–423. doi:10.3391/ai.2014.9.4.01. [Google Scholar]

- Jones NA, Ross H, Lynam T, Perez P, Leitch A. Mental models: An interdisciplinary synthesis of theory and methods. Ecol. Soc. 2011, 16, 46. doi:10.5751/ES-03802-160146. [Google Scholar]

- Moon K, Blackman D. A guide to understanding social science research for natural scientists. Conserv. Biol. 2014, 28, 1167–1177. doi:10.1111/cobi.12326. [Google Scholar]

- Zenetos A. Trend in aliens species in the Mediterranean. An answer to Galil, 2009 «Taking stock: Inventory of alien species in the Mediterranean Sea». Biol. Invasions 2010, 12, 3379–3381. doi:10.1007/s10530-009-9679-x. [Google Scholar]

- Diga R, Gilboa M, Moskovich R, Darmon N, Amit T, Belmaker J, et al. Invading bivalves replaced native Mediterranean bivalves, with little effect on the local benthic community. Biol. Invasions 2023, 25, 1441–1459. doi:10.1007/s10530-022-02986-1. [Google Scholar]

- Otero M, Cebrian E, Francour P, Galil B, Savini D. Monitoring Marine Invasive Species in Mediterranean Marine Protected Areas (MPAs): A Strategy and Practical Guide for Managers; IUCN Centre for Mediterranean Cooperation: Málaga, Spain, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Pafras D, Apostologamvrou C, Balatsou A, Theocharis A, Lolas A, Hatziioannou M, et al. Reproductive Biology of Pearl Oyster (Pinctada radiata, Leach 1814) Based on Microscopic and Macroscopic Assessment of Both Sexes in the Eastern Mediterranean (South Evia Island). J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 1259. doi:10.3390/jmse12081259. [Google Scholar]

- Pafras D, Theocharis A, Kondylatos G, Conides A, Klaoudatos D. Population Biology of the Non-Indigenous Rayed Pearl Oyster (Pinctada radiata) in the South Evoikos Gulf, Greece. Diversity 2024, 16, 460. doi:10.3390/d16080460. [Google Scholar]

- Gavrilović A, Piria M, Guo XZ, Jug-Dujaković J, Ljubučić A, Krkić A, et al. First evidence of establishment of the rayed pearl oyster, Pinctada imbricata radiata (Leach, 1814), in the eastern Adriatic Sea. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2017, 125, 556–560. doi:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2017.10.045. [Google Scholar]

- Lynam T, De Jong W, Sheil D, Kusumanto T, Evans K. A review of tools for incorporating community knowledge, preferences, and values into decision making in natural resources management. Ecol. Soc. 2007, 12, 5. doi:10.5751/ES-01987-120105. [Google Scholar]

- Dietz T, Ostrom E, Stern PC. The struggle to govern the commons. Science 2003, 302, 1907–1912. doi:10.1126/science.1091015. [Google Scholar]

- Matias G, Rosalino LM, Alves PC, Tiesmeyer A, Nowak C, Ramos L, et al. Genetic integrity of European wildcats: Variation across biomes mandates geographically tailored conservation strategies. Biological Conservation 2022 Apr 1; 268:109518. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2022.109518. [Google Scholar]

- Regulation P. General data protection regulation. Intouch 2018, 25, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Gray SA, Zanre E, Gray SR. Fuzzy cognitive maps as representations of mental models and group beliefs. In Fuzzy Cognitive Maps for Applied Sciences and Engineering: From Fundamentals to Extensions and Learning Algorithms; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp 29–48. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-39739-4_2. [Google Scholar]

- Moon K, Guerrero AM, Adams VM, Biggs D, Blackman DA, Craven L. Mental Models for Conservation Research and Practice. Conserv. Lett. 2019, 12, e12642. doi:10.1111/conl.12642. [Google Scholar]

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa. [Google Scholar]

- Field A. Discovering Statistics Using SPSS, 5th ed.; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Fabrigar LR, Wegener DT, MacCallum RC, Strahan EJ. Evaluating the Use of Exploratory Factor Analysis in Psychological Research. Psychol. Methods 1999, 4, 272–299. doi:10.1037/1082-989X.4.3.272. [Google Scholar]

- Trahan LH, Stuebing KK, Fletcher JM, Hiscock M. The Flynn effect: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 2014, 140, 1332. doi:10.1037/a0037173. [Google Scholar]

- Cronbach LJ. Coefficient Alpha and the Internal Structure of Tests. Psychometrika 1951, 16, 297–334. doi:10.1007/BF02310555. [Google Scholar]

- WordCloud Team. Wordcloud: A Little Word Cloud Generator in Python. GitHub Repository (Version 1.9.3), 2024. Available online: https://github.com/amueller/word_cloud (accessed on 15 October 2025). [Google Scholar]

- European Union. General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council (27 April 2016). Official Journal of the European Union, L119, 1–88. Available online: https://dvbi.ru/Portals/0/DOCUMENTS_SHARE/RISK_MANAGEMENT/EBA/GDPR_eng_rus.pdf (accessed on 15 October 2025). [Google Scholar]

- Van Rossum G, Drake FL. Python Language Reference Manual; Network Theory Ltd.: Bristol, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Pedregosa F, Varoquaux G, Gramfort A, Michel V, Thirion B, Grisel O, et al. Scikit-learn: Machine Learning in Python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2011, 12, 2825–2830. [Google Scholar]

- Lemaître G, Nogueira F, Aridas CK. Imbalanced-Learn: A Python Toolbox to Tackle the Curse of Imbalanced Datasets in Machine Learning. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2017, 18, 559–563. [Google Scholar]

- Bird S, Klein E, Loper E. Natural Language Processing with Python; O’Reilly Media: Sebastopol, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Gray T, Hatchard J. A complicated relationship: Stakeholder participation and the ecosystem-based approach to fisheries management. Mar. Policy 2008, 32, 158–168. doi:10.1016/j.marpol.2007.09.002. [Google Scholar]

- Heinle KB, Al-Chokhachy R, Sepulveda A, Verhille C. Native Yellowstone cutthroat trout Oncorhynchus virginalis bouvieri growth and survival in a headwater stream primarily driven by warming stream temperatures, with non-native brown trout Salmo trutta posing an additional threat to survival. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2025, 82, 1–17. doi:10.1139/cjfas-2024-0211. [Google Scholar]

- Evans J, Thomas C. Environmental Governance; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2023. doi:10.4324/9781003334699. [Google Scholar]

- Reyers B, Moore ML, Haider LJ, Schlüter M. The contributions of resilience to reshaping sustainable development. Nat. Sustain. 2022, 5, 657–664. doi:10.1038/s41893-022-00889-6. [Google Scholar]

- Fujitani ML, Riepe C, Pagel T, Buoro M, Santoul F, Lassus R, et al. Ecological and social constraints are key for voluntary investments into renewable natural resources. Glob. Environ. Change 2020, 63, 102125. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2020.102125. [Google Scholar]

- Guerra AS. Wolves of the Sea: Managing human-wildlife conflict in an increasingly tense ocean. Mar. Policy 2019, 99, 369–373. doi:10.1016/j.marpol.2018.11.002. [Google Scholar]

- Adams KJ, Metzger MJ, Helliwell RC, Pohle I. Understanding knowledge needs for Scotland to become a resilient Hydro Nation: Water stakeholder perspectives. Environ. Sci. Policy 2022, 136, 157–166. doi:10.1016/j.envsci.2022.06.006. [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez NL, Hilborn R, Defeo O. Leadership, social capital and incentives promote successful fisheries. Nature 2011, 470, 386–389. doi:10.1038/nature09689. [Google Scholar]

- Folke C, Carpenter SR, Walker B, Scheffer M, Chapin T, Rockström J. Resilience thinking: integrating resilience, adaptability and transformability. Ecol. Soc. 2010, 15. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/26268226 (accessed on 15 October 2025). [Google Scholar]

- Oyanedel R. Tackling Small-Scale Fisheries Non-Compliance, Ph.D. Thesis, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ekardt F, Stoll-Kleemann S. Environmental Humanities: Transformation, Governance, Ethics, Law. (No Title). 2020. Available online: https://www.sustainability-justice-climate.eu/files/texts/Sustainability-Springer.pdf (accessed on 15 October 2025). [Google Scholar]

- Ryan RM, Deci EL. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 68–78. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Werff E, Steg L, Keizer K. The value of environmental self-identity: The relationship between biospheric values, environmental self-identity and environmental preferences, intentions and behaviour. J. Environ. Psychol. 2013, 34, 55–63. doi:10.1016/j.jenvp.2012.12.006. [Google Scholar]

- Janssen MA, Bodin Ö, Anderies JM, Elmqvist T, Ernstson H, McAllister RR, et al. Toward a network perspective of the study of resilience in social-ecological systems. Ecol. Soc. 2006, 11. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/26267803 (accessed on 15 October 2025). [Google Scholar]

- Cosens B, Gunderson L. Adaptive governance in north American water systems: A legal perspective on resilience and reconciliation. In Water Resilience: Management and Governance in Times of Change; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 171–192. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-48110-0_8. [Google Scholar]

- Charrua AB, Bandeira SO, Catarino S, Cabral P, Romeiras MM. Assessment of the vulnerability of coastal mangrove ecosystems in Mozambique. Ocean. Coast. Manag. 2020, 189, 105145. doi:10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2020.105145. [Google Scholar]

- Cappell R, MacFadyen G, Constable A. Research funding and economic aspects of the Antarctic krill fishery. Mar. Policy 2022, 143, 105200. doi:10.1016/j.marpol.2022.105200. [Google Scholar]

- Cardinale M, Colloca F, Bonanno A, Scarcella G, Arneri E, Jadaud A, et al. The Mediterranean fishery management: A call for shifting the current paradigm from duplication to synergy. Mar. Policy 2021, 131, 104612. doi:10.1016/j.marpol.2021.104612. [Google Scholar]

- Chuenpagdee R, Jentoft S. Transforming the governance of small-scale fisheries. Marit. Stud. 2018, 17, 101–115. doi:10.1007/s40152-018-0087-7. [Google Scholar]

- Olenin S, Minchin D. Introductions of non-indigenous species to coastal and estuarine systems. Treatise Estuar. Coast. Sci. 2024, 6, 259–301. doi:10.1016/B978-0-323-90798-9.00021-4. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen L, Ngwenyama O, Bandyopadhyay A, Nallaperuma K. Realising the potential of digital health communities: a study of the role of social factors in community engagement. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2024, 33, 1033–1068. doi:10.1080/0960085X.2023.2252390. [Google Scholar]

- Vasquez HM, Pianarosa E, Sirbu R, Diemert LM, Cunningham H, Harish V, et al.. Human factors methods in the design of digital decision support systems for population health: a scoping review. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 2458. doi:10.1186/s12889-024-19968-8. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. UN Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development (2021–2030); UNESCO Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission Report; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]