Advances in Hydrology of Irrigation Districts in Cold Regions

Received: 28 August 2025 Revised: 17 November 2025 Accepted: 24 December 2025 Published: 30 December 2025

© 2025 The authors. This is an open access article under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

1. Introduction

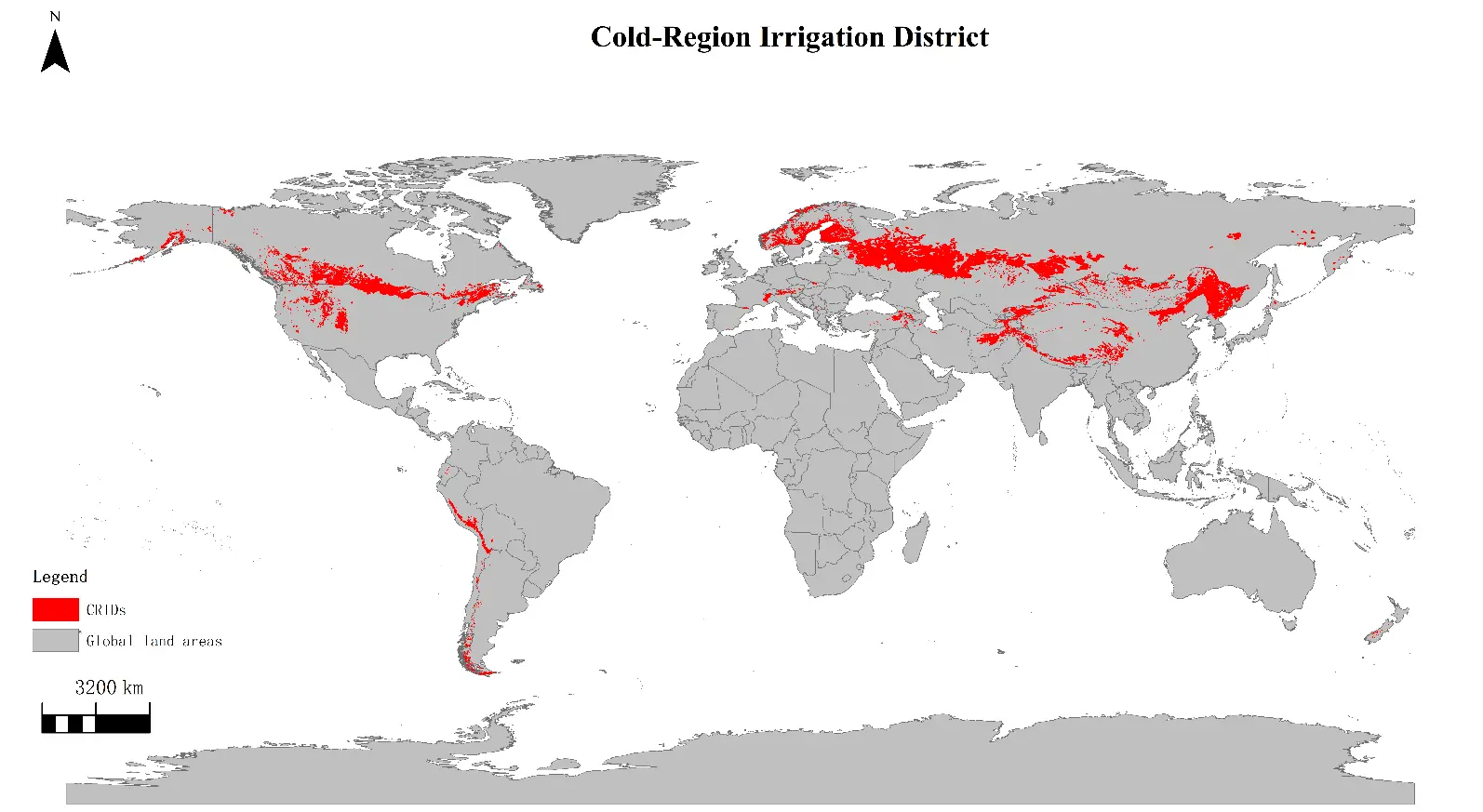

Cold-Region Irrigation Districts (CRIDs) specifically refer to agricultural districts located in mid-to-high latitude or high-altitude cold regions that rely on artificial irrigation to sustain agricultural productivity [1,2]. These districts are primarily distributed across Alaska and northern Canada, northern Europe, Siberia in Russia, as well as northeastern to northwestern China [3,4,5] Figure 1.

CRIDs represent unique geographic units where cold climate and irrigation systems are coupled, and their hydrological processes are governed by complex interactions between hydrothermal dynamics, resulting in water cycling mechanisms distinct from those in conventional irrigation areas [6]. The hydrological processes in CRIDs fundamentally control the spatiotemporal distribution of water resources by regulating the storage and release of snowmelt, leading to the characteristic “spring flood–summer drought” paradox that defines regional water availability. Consequently, they directly determine the feasibility and productivity of agriculture in short growing seasons, as irrigation management is essentially an artificial intervention to realign this mismatched water supply with crop demand. Simultaneously, these processes introduce significant agricultural and environmental risks, including soil salinization, non-point source pollution, and waterlogging [7,8].

Figure 1. Global distribution of Cold-Region Irrigation Districts. The global distribution was derived by integrating two publicly available and globally consistent datasets, using the software of ArcGIS 10.8. Cold regions were identified using the WorldClim v2.1 global climate dataset (1970–2000, 5-arc-minute resolution), based on areas with an annual mean temperature below 0 °C or at least one month having a mean temperature below 0 °C. Irrigated agricultural areas were obtained from the Global Map of Irrigated Areas (GMIA v5, circa 2015), using the percentage of each grid cell equipped for irrigation.

Beyond water and agriculture, CRID hydrology creates profound feedback with the regional climate and environment. It alters local microclimates through enhanced evapotranspiration, threatens permafrost stability, and regulates the vitality of downstream ecosystems by controlling ecological water flows [9,10,11]. Ultimately, these interconnected hydrological functions act as a central nexus, governing the resilience and vulnerability of the entire socio-ecological system. A comprehensive understanding of these influences is therefore a foundational prerequisite for achieving sustainable water management, agricultural security, and ecological protection in cold regions [10].

Driven by the interaction between seasonal freeze–thaw cycles and irrigation practices, CRIDs exhibit distinct agricultural hydrological processes. In winter, infiltration pathways from the surface to the subsurface are blocked, thereby impeding groundwater recharge, while shallow soil moisture is retained in a frozen state [12]. In spring, as air temperatures rise, the active soil layer rapidly thaws, releasing large amounts of previously frozen water. This leads to sharp increases in surface runoff, soil temperature, and water–heat fluxes, along with a rapid rise in groundwater levels [13,14], ultimately reshaping regional hydrodynamic structures [15]. The overall hydrological cycle spans surface water, the vadose zone, and groundwater [16]. Compared with irrigation districts in temperate regions, CRIDs are strongly influenced by precipitation, irrigation, and freeze–thaw dynamics, resulting in pronounced seasonal transient hydrological behavior [17,18]. Here, “transient hydrological behavior” refers to physical transient processes rather than statistical non-stationarity. Additionally, water and heat transport are tightly coupled, and solute migration (particularly of salts) is highly active [19], posing significant challenges to agricultural and ecological adaptation. Due to the uneven spatiotemporal distribution of water resources and the limited capacity for natural regulation, CRID hydrological systems are susceptible to climate variability, irrigation practices, and shifts in freeze–thaw regimes [12]. Collectively, the hydrological processes of CRIDs can be characterized as exhibiting seasonal and transient hydrological dynamics, strong hydro-thermal-salt coupling, and systemic vulnerability [20].

Hydrological systems generally exhibit significant long-term uncertainties at multi-year scales, typically characterized by long-term persistence (LTP) of hydrological variables and the clustering of wet and dry years [21,22,23]. Key components such as precipitation, runoff, groundwater recharge, and snow water equivalent often exhibit extended periods of above- or below-average conditions, which can significantly affect regional water resource availability and variability [21]. In cold regions, interannual fluctuations in snow accumulation, snowmelt, and seasonal freeze–thaw processes further amplify this long-term uncertainty, thereby increasing the complexity of water resource regulation and irrigation management [21].

The intensification of climate change is profoundly altering precipitation patterns, temperature regimes, and freeze–thaw cycles [12,15,24,25]. These changes interact with the unique hydrological mechanisms of CRIDs, amplifying the spatiotemporal extremes of water distribution, complicating surface–groundwater interactions, and increasing the risk of soil salinization [26,27,28,29,30]. The combined effects of climate change and non-stationary systems not only magnify existing instabilities but also introduce unprecedented challenges, thereby imposing higher demands on sustainable agricultural development and water resource management in CRIDs [31,32,33]. Against this backdrop, synthesizing research progress in this field holds significant theoretical and practical value. Such synthesis can deepen understanding of cold-region hydrological processes and provide scientific support for addressing water resource risks under climate change [34,35,36].

This review focuses on hydrological processes in CRIDs under freeze–thaw conditions, summarizing advances in five major areas: (1) the evolution of hydrological process research in Cold-Region Irrigation Districts (CRIDs); (2) hydrological processes under the interaction of freeze–thaw cycles and irrigation in CRIDs; (3) numerical modeling of hydrological processes in CRIDs; (4) hydrological response of CRIDs to climate warming and extreme events; and (5) challenges and perspectives in the study of hydrological processes in irrigated cold regions. The overarching aim is to provide theoretical insights and modeling references for hydrological process studies in CRIDs, and to support the sustainable utilization of agricultural water resources in cold regions [37,38,39].

2. Evolution of Hydrological Process Research in Cold-Region Irrigation Districts

Systematic research on hydrological processes in CRIDs dates to the 1950s and 1960s. In the early stages of the mid-to-late 20th century to the early 21st century, studies primarily focused on the regulatory role of seasonal freezing in the water cycle. Field observations revealed that frozen soil layers substantially restrict surface water infiltration, reduce winter groundwater recharge, and lead to rapid snowmelt runoff peaks in spring, thereby reshaping regional hydrodynamic structures [40,41]. During this stage, research was dominated by phenomenon identification, emphasizing hydrological indicators such as frozen-layer thickness, active-layer dynamics, and groundwater table responses [17,42,43]. However, most studies have concentrated on single-factor processes—for example, the effects of freeze–thaw cycles on heat distribution, infiltration, or groundwater fluctuations [44,45]—while the interactive feedback among processes received limited attention. In particular, systematic understanding of the dynamic interplay between artificial irrigation and freeze–thaw processes remained lacking [16].

As research on frozen-soil hydrology has advanced, investigations of hydrological processes in CRIDs have gradually evolved from single-process simulations to multi-process coupled modeling. Representative hydrological models, such as SWAT (Soil and Water Assessment Tool), MIKE SHE, and GSFLOW (Groundwater and Surface Water Flow Model), have been extended to incorporate freeze–thaw dynamics, soil hydrothermal processes, groundwater recharge, and crop water requirements [33,46,47,48,49]. These models can simulate soil temperature distributions, water fluxes, and groundwater variations under freeze–thaw conditions [46,50]. Despite these advancements in mechanistic representation, most models were originally developed for temperate or humid regions, primarily for natural ecosystems rather than agricultural landscapes. As a result, freeze–thaw processes are often oversimplified into binary “frozen/thawed” states, while irrigation scheduling, tillage disturbances, and crop physiological traits are insufficiently represented [35,36,51,52]. This limits their applicability in cold-region agricultural settings, particularly in capturing the coupled interactions among crop growth cycles, irrigation regulation, and groundwater responses.

Since the beginning of the 21st century, research priorities have shifted toward integrated coupling mechanisms among irrigation regimes, climate change, and freeze–thaw dynamics. Notable progress has been achieved through the extension of hydrological models, such as VIC (Variable Infiltration Capacity Model) and HYPE (Hydrological Predictions for the Environment), which incorporate soil thermal modules and irrigation subsystems to simulate seasonal freeze–thaw transitions, irrigation demands, and basin-scale water balance [53,54,55,56]. For instance, the VIC–CropSyst (Variable Infiltration Capacity–Crop System Model framework) framework has enabled explicit coupling between crop water use and hydrological fluxes, and has been applied in scenario-based assessments of agricultural catchments in cold regions [57]. Concurrently, regional observations have revealed a characteristic “V-shaped” fluctuation in groundwater levels during freeze–thaw transitions—declining during freezing and rebounding rapidly upon thawing—governed by critical factors such as frozen-layer thickness, initial groundwater depth, and snowpack accumulation [12,58,59,60].

At present, simulations of hydrological processes in CRIDs are entering a new phase characterized by cross-scale, multi-system integration. On the one hand, models are incorporating more sophisticated physical mechanisms, such as nonlinear freeze–thaw phase-change dynamics and groundwater–vadose zone feedback [48,61,62,63,64,65,66]. On the other hand, increasing efforts are being made to integrate crop models that explicitly consider crop growth cycles, root-zone water uptake, and land cover evolution, thereby enhancing their applicability to agricultural settings and irrigation management [67,68,69,70,71,72].

Nevertheless, current models face three major challenges that require further breakthroughs: (1) the representation of nonlinear phase-change processes remains insufficient, with freeze–thaw often simplified into binary “frozen/unfrozen” states [73]; (2) the mechanisms linking land-surface crop cover and anthropogenic disturbances to hydrological responses are not yet fully developed, limiting their ability to reflect the dynamics of actual irrigation management [74,75]; and (3) regional-scale applications still lack sufficient integration of hydrological, meteorological, and ecological systems, constraining the quantitative assessment of model performance in regulation and management [76,77,78,79,80].

Overall, with the intensification of global climate warming, increasing agricultural water demand, and the growing complexity of irrigation-district ecosystems [81], research on hydrological processes in CRIDs has evolved from empirical observations to physically based modeling, and from single-factor descriptions to multi-process coupled simulations. This evolution not only deepens the understanding of hydrological mechanisms but also reflects continuous improvements in model conceptualization, coupling capabilities, and application accuracy [73,82,83,84,85,86,87,88].

3. Hydrological Processes under the Interaction of Freeze–Thaw Cycles and Irrigation

3.1. Key Components of Hydrological Processes in CRIDs

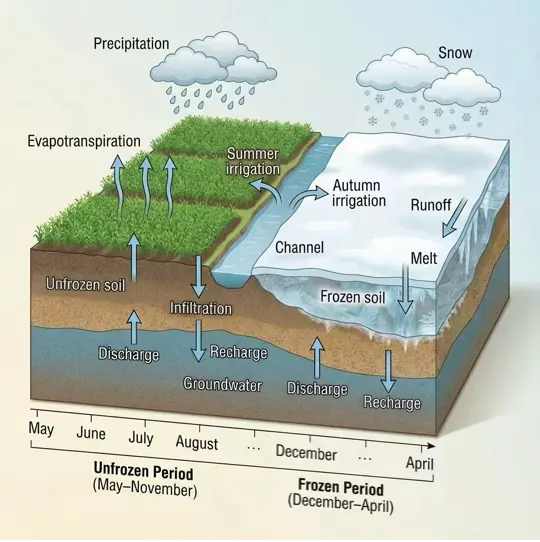

In irrigated cold-region basins, the hydrological regime exhibits pronounced transient behavior and complex spatiotemporal variability under the combined influence of seasonal freeze–thaw cycles and agricultural water application [89,90]. As shown in Figure 2, precipitation and irrigation water, runoff generation and routing, infiltration, evapotranspiration, and groundwater recharge–discharge are tightly coupled, forming a highly interactive, time-varying system [91]. Within this system, freeze–thaw dynamics exert first-order control on flow paths, fluxes, and the spatial distribution of soil water: the formation of a frozen layer suppresses vertical percolation, promotes near-surface water ponding, and consequently enhances Hortonian/impermeable-layer overland flow; during thaw, snowmelt inputs and the decay of the frost table enable rapid infiltration, preferential flow, and pulse-like recharge that redistribute soil water and modulate aquifer replenishment [92,93,94,95].

Irrigation, as an anthropogenic water addition, directly perturbs soil moisture states and the coupled water–energy balance. Winter (off-season) irrigation can elevate antecedent water content, delay frost penetration, and reconfigure the vertical distribution of unfrozen water, thereby altering freeze-up dynamics and promoting a stronger groundwater rebound during the thaw, which in turn benefits early-season crop water supply [96,97]. However, excessive or poorly timed irrigation can lead to persistently wet topsoil, higher non-productive evaporation, abnormal groundwater-level rise or, conversely, in some systems, long-term groundwater depletion and waterlogging or salinization risks that complicate allocation and root-zone management [98,99,100]. The net outcome of freeze–thaw–irrigation interactions therefore governs not only soil-water dynamics and groundwater recharge but also crop phenology and agricultural productivity across irrigated cold-region landscapes [101,102,103]. Figure 2 provides a conceptual illustration of these hydrological processes, highlighting the coupled dynamics of soil water, groundwater, and surface fluxes in cold-region irrigation districts.

The hydrologic regime of irrigated cold regions constitutes a tightly coupled system in which the combined action of freeze–thaw dynamics and irrigation profoundly shapes the spatiotemporal distribution of water, drives fluctuations in the groundwater table, and constrains water allocation decisions. These cryo-hydrologic interactions modulate runoff–infiltration partitioning, vadose-zone storage, and recharge pulses, thereby propagating signals to the aquifer and surface networks [12,32,94,104]. Against the backdrop of global warming, climate change is altering seasonality in hydrologic processes, accelerating or shifting freeze–thaw rates, and reshaping irrigation demand—intensifying water-stress risks and management complexity [33,83,105,106,107]. These evolving forcings necessitate adaptive water-resources governance—integrating coupled surface–groundwater modeling under seasonal freezing, demand management, and allocation that safeguards environmental flows—to sustain agricultural productivity [108,109,110].

3.2. Water Input Processes Driven by Precipitation Phase Changes and Agricultural Irrigation

In the hydrological cycle of cold-region irrigation districts, precipitation consistently plays a fundamental role, while agricultural irrigation constitutes another major source of water input, functioning in parallel with natural precipitation.: winter precipitation stored as snow functions as a seasonal natural reservoir, and the timing and magnitude of snow accumulation and melt directly control the tempo of springtime soil moisture recharge and the initiation of early-season runoff [111,112].

Warming-driven changes in precipitation phase are already reshaping these dynamics. In many headwater basins, including portions of the Upper Yellow River, observational and modeling evidence indicate a statistically significant decrease in snowfall fraction and an increase in winter rainfall frequency over recent decades, with attendant reductions in snowpack water equivalent that weaken the “snow reservoir” relied upon for spring replenishment [113,114,115], thereby increasing the dependence on irrigation water.

There is a clear interaction between changes in natural precipitation and irrigation practices. During the winter freezing period, rainfall is impeded by the frozen soil layer and cannot infiltrate; irrigation applied at this stage faces a similar constraint, resulting in surface water stagnation and limited infiltration. During the spring thaw, rainfall combined with snowmelt can enhance soil moisture and deep recharge if irrigation is applied in an appropriate manner. However, improper superposition of rainfall and irrigation may lead to field waterlogging and increased drainage pressure.

Therefore, under climate warming, changes in precipitation phase not only reshape the pattern of natural water inputs but also intersect with irrigation-driven inputs. Together, they determine the spatiotemporal distribution of water and soil freeze–thaw dynamics, and the effective spring recharge in cold-region irrigation districts, imposing new and more complex requirements on irrigation management.

3.3. Surface Runoff Generation and Infiltration

Surface runoff generation and vertical infiltration are tightly coupled during freeze–thaw cycles and jointly regulate the exchange of water between the land surface and the soil column [91,102]. In winter, the development of a frozen layer substantially constrains vertical percolation, causing precipitation and meltwater to remain in the near-surface horizon and, in low-lying areas, to pond or form surface water bodies [116,117]. With the onset of spring warming and the progressive thawing of the frozen layer, the water previously detained at the surface or in shallow soil is released: a fraction is delivered as short-duration flood peaks while another fraction rapidly infiltrates to recharge deeper soil reservoirs [118,119]. The extent and rate of infiltration are not only a function of the freeze–thaw state but are also strongly mediated by soil texture and structure—frozen-induced macropores and thaw cracks in coarse-textured soils can enhance downward flow, whereas clayey soils with an intact frost barrier tend to produce disproportionately large surface-runoff fractions [98,120].

Observational and modeling studies from mountain catchments demonstrate the dominance of snowmelt and the suppressive effect of frozen ground on infiltration [121,122,123]. For example, in parts of the European Alps, spring snowmelt may account for the majority of annual river discharge, and the presence of a frost-impermeable layer causes many winter rainfall events to be routed almost entirely to surface runoff with little subsurface penetration. Similar field measurements in high-cold mountain systems, such as the Qilian Mountains, reveal characteristic “wet-above/dry-below” soil moisture profiles during freeze–thaw transition periods: abundant surface or near-surface water that does not infiltrate into the root zone until thawing progresses to greater depths [124,125]. These responses are controlled by snowpack depth, frozen-soil thickness, and topographic slope, among other natural factors [91,121,126].

By contrast, irrigated lowland fields are typically leveled and tilled, feature smaller microtopographic relief, and receive anthropogenic water inputs that modify surface–subsurface exchange [127]. In irrigated districts, the rapid springtime replenishment of soil moisture comprises meltwater and precipitation augmented by scheduled irrigation [121]. If irrigation is applied while the soil column remains partially frozen, water commonly accumulates in the shallow layer and is lost as surface runoff. Conversely, well-timed irrigation that coincides with sufficient thawing can markedly increase infiltration and alleviate moisture stress during crop greening [44]. Field practices in the Ningxia Yellow River diversion irrigation district, for instance, schedule winter irrigation within a narrow “freeze-initiation window” when surface temperatures approach 0 °C and soil temperatures remain below ~5 °C [128]; by controlling application depth and timing, the water becomes effectively “stored” within the forming frozen layer (the so-called “ice-bank” or “ice-reservoir” effect), which then releases substantial moisture to the root zone upon spring thaw [129]. In other systems, such as the Hetao (Hohhot–Baotou) and upstream Hetao/Hetao–Huanghe irrigation areas, however, premature or excessive autumn/winter irrigation has been observed to raise groundwater tables beneath the frozen layer (reported increases on the order of decimeters in intensive cases) [130], induce surface waterlogging in the tilled layer, delay the thawing front, and impair early-season crop emergence [131].

These examples illustrate that freeze–thaw modulation of runoff–infiltration partitioning sculpts the seasonal spatiotemporal pattern of soil moisture and ultimately governs irrigation water-use efficiency [132]. In mountainous environments, partitioning is primarily controlled by natural factors (snowpack, soil freezing depth, slope) [133,134]; in irrigated plains, partitioning results from the compound effect of frozen-ground hydraulics and irrigation management (method, timing, and volume) [135,136]. This coupled natural–anthropogenic control produces runoff and infiltration dynamics in cold-region irrigation districts that are distinct from those in purely high-altitude or non-irrigated landscapes and require irrigation strategies that explicitly account for soil thermal state and frozen-ground hydrodynamics [92,94].

3.4. Evaporation and Transpiration Processes

Evapotranspiration (ET) represents a key output term in the water budget of irrigated cold regions, and its spatiotemporal dynamics are co-constrained by seasonal freeze–thaw processes and irrigation management. During the frozen season, low temperatures suppress soil liquid-water mobility and limit available energy, so both soil/surface evaporation and canopy transpiration remain at low flux levels; at the initial thaw, rapid snowmelt and abrupt increases in shallow-layer liquid water frequently trigger short-lived surges in surface evaporation that are subsequently transferred—as vegetation leaf area and activity recover—into transpiration-dominated water use during crop green-up [104,137].

Flux-tower and integrative observational studies over cold temperate regions (e.g., Canadian prairies and high-latitude sites) document this “thaw-driven ET jump”: energy and water fluxes rapidly shift from an input-limited or potential-ET regime toward a state constrained by available moisture and canopy conductance after thaw, producing pronounced post-thaw ET peaks and strong seasonality in latent-heat release [138,139].

In irrigated oases and agricultural districts (for example, irrigated systems in Xinjiang), remote-sensing inversion and in-situ monitoring indicate that winter–spring irrigation raises early-season root-zone moisture and reduces crop water stress, thereby stabilizing transpiration during the tillering/elongation stages; however, excessive irrigation amplifies non-productive evaporation and lowers overall water-use efficiency, an effect quantified in recent regional assessments combining satellite ET retrievals and ground observations [140,141,142].

Non-irrigated cold ecosystems also exhibit a thaw-ET (or transpiration) transition, but the phenological and hydrological expression differs: in boreal and temperate agricultural or forest plots of Scandinavia and other cold temperate zones, the post-thaw energy balance evolves from sensible-heat dominance toward latent-heat dominance, yet ET there is tightly coupled to snowmelt supply and canopy phenology because of the lack of anthropogenic water inputs, limiting managerial leverage. Long-term observational and modeling studies have documented these land-cover dependent contrasts in water–energy partitioning across similar climatic envelopes [137,138,143].

By contrast, irrigated plains operating under the same climatic forcing can actively reshape thaw-period soil-moisture boundary conditions and energy partitioning through human decisions on irrigation timing, method, and volume—i.e., irrigation timing, irrigation quotas, and application methods. These management controls can substantially alter the ratio and timing of evaporation versus transpiration during thaw, and regional hydrothermal assessments for inland river basins (e.g., the Hexi Corridor/Heihe and other arid inland catchments) show that ET in irrigated districts is jointly sensitive to climate and operational practice [144,145,146].

Synthesis of the controlling factors indicates that the principal drivers of these differences are: air temperature and radiation (which set thaw rate and potential ET), snow depth and melt timing (which define early-season available water and the temporal window of evaporation peaks), frozen-layer thickness and soil texture/structure (which regulate upward and downward water fluxes and evaporative supply), vegetation phenology and canopy structure (which determine transpiration capacity), and irrigation scheduling/quotas (which directly reset soil-moisture and surface energy boundaries). In unmanaged systems, these drivers are dominated by climate and substrate attributes, whereas the anthropogenic management dimension overlays and often dominates in irrigated systems, yielding higher controllability but also greater management dependence of ET signals [143,147].

3.5. Groundwater Recharge and Discharge

Groundwater recharge constitutes the integrated expression of freeze–thaw–irrigation coupling, and its spatiotemporal variability is jointly regulated by seasonal soil freezing–thawing and irrigation management. During the frozen season, the formation of a frost layer strongly impedes vertical percolation and renders direct groundwater recharge minimal; water instead tends to accumulate in the near-surface horizon, increasing surface storage and routing to overland flow [34,148].

With the onset of thaw, however, rapid release of snowmelt and previously detained soil water promotes expedited percolation to depth and a characteristic, often sharp, rebound of the water table (a “V-shaped” response in many monitored sites). Preferential flow pathways through macropores and thaw-induced cracks can allow substantial recharge even while portions of the vadose zone remain frozen, producing short, pulse-like groundwater rises during spring melt [94,118].

When freeze–thaw dynamics interact with managed irrigation, recharge and leakage behavior depart from patterns observed in non-frozen or non-irrigated settings. Winter (off-season) irrigation increases antecedent soil moisture and alters the frozen-layer evolution, concentrating recharge during thaw and accelerating springtime groundwater recovery under moderate application regimes; field monitoring in several Yellow-River irrigated plains (e.g., Hetao, Yinchuan/Ningxia) reports faster post-thaw groundwater level recovery where winter irrigation is applied in controlled amounts [149,150].

Conversely, excessive or improperly timed winter irrigation can drive undesirable groundwater dynamics: anomalous groundwater rises beneath the frost table, prolonged soil waterlogging in the tilled horizon, delayed thaw propagation, and consequent impediments to spring sowing and seedling emergence. Intensive local studies and basin assessments from Xinjiang and other irrigated inland regions document cases in which significant winter flood-irrigation events elevated shallow groundwater by decimeters, exacerbated drainage loads during thaw, and prolonged cold-season soil saturation [151,152].

By contrast, non-frozen or non-irrigated regions show groundwater recharge regimes governed primarily by precipitation seasonality, soil hydraulic properties and topography; in temperate humid zones (e.g., parts of Europe) winter recharge is more evenly distributed because precipitation mainly falls as rain and frozen ground plays little or no role, while in tropical climates year-round infiltration maintains more stable recharge controlled by monsoon or convective rainfall patterns [153].

Therefore, the superposition of freeze–thaw processes and irrigation management produces pronounced seasonal variability and a degree of anthropogenic control over groundwater recharge in cold-region irrigation districts. Compared with the relatively stable recharge regimes of humid or tropical regions, cold-region irrigated systems are more sensitive to the timing, volume and method of irrigation; well-designed winter and spring irrigation schedules that account for soil thermal state can mitigate frost-barrier effects, accelerate groundwater recovery during thaw, and improve irrigation water-use efficiency [104,136].

4. Multiscale Approaches and Modeling Frameworks for Hydrological Process Simulation

The simulation of hydrological processes is a fundamental tool for water-resources management, agricultural irrigation optimization, and flood prevention. Depending on spatial scale, hydrological models can generally be categorized into field-scale models and watershed-scale models. Field-scale models focus on the soil–crop–atmosphere interactions of a single agricultural plot or small experimental area, enabling detailed representation of vertical soil-water movement, root-water uptake, and crop transpiration; such models are widely used in irrigation design, crop water-requirement assessment, and field water-balance management. Representative examples include AquaCrop (Aquatic Crop Model) [154] and HYDRUS (Hydrus-1D/2D/3D Variably Saturated Flow Model) for variably saturated flow [155].

In contrast, watershed-scale models integrate spatial heterogeneity in topography, soils, vegetation, and land use, allowing simulation of precipitation–runoff generation and water-flux regulation across larger spatial domains. Such models are widely used in watershed water resource assessment, flood forecasting, and management planning. Classical examples include SWAT [156], HBV (Hydrologiska Byråns Vattenbalansavdelning Model) [157], and TOPMODEL (Topographic Wetness Index Model) [158]. Different model scales each have their strengths, and the optimal choice depends on research objectives, data availability, and computational demands.

4.1. Field-Scale Soil Moisture Model

Field-scale soil moisture models can be broadly classified into conceptual water-balance models and physics- or process-based numerical models.

4.1.1. Conceptual Water Balance Models

Conceptual models typically use the basic soil water balance equation as the core framework, which describes the change in soil water storage(ΔS) under precipitation (P), irrigation (I), evapotranspiration (ET), runoff (R), and deep percolation (D):

|

```latex∆S=P+I-ET-R-D``` |

These models feature a simple structure, low parameter requirements, and strong robustness, making them suitable for data-scarce regions or scenarios requiring rapid assessment. Typical models developed under this framework include the FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations) crop water requirement model, the Kc–ET₀ (Crop Coefficient–Reference Evapotranspiration) single-crop-coefficient approach, ISAREG (Irrigation Scheduling and Simulation Model), AquaCrop, and SMDualKc (Soil Moisture Dual Crop Coefficient Model).

The FAO framework was first established in the late 1970s to standardize crop water requirement estimation worldwide [159]. Subsequently, the Kc–ET₀ approach was refined by Allen et al. [160] to address consistency issues in estimating crop evapotranspiration across diverse climate regions. During the 1990s–2000s, the ISAREG model integrated soil water balance with crop growth processes to support optimized irrigation scheduling [161]. Later, AquaCrop incorporated biomass production mechanisms into the water-balance structure to predict yield responses under conditions of climate variability and climate change [154]. More recently, the SMDualKc model improved the representation of soil evaporation and crop transpiration partitioning by coupling the dual crop coefficient method with soil water balance calculations [162].

4.1.2. Physics-Based Models

The physics-based models include Richards-equation-based unsaturated flow models, coupled heat–water–vapor transfer models, and preferential flow models. Physics-based models are commonly formulated using the Richards equation:

|

```latex\frac{\partial \theta }{\partial t}=\nabla \cdot \left[K\left(\theta \right)\left(\nabla h+\nabla z\right)\right]``` |

where θ is volumetric water content, K(θ) is hydraulic conductivity, h is pressure head, and z is gravitational potential. This equation [163] describes water movement in the unsaturated zone and can be coupled—under either the h-form or mixed-form formulation—with the energy conservation equation, vapor diffusion processes, or dual-domain flow models; the pure θ-form is less commonly used because it handles the saturated–unsaturated transition poorly.

These models offer clear physical interpretability and can explicitly represent vertical water redistribution, evaporation partitioning, root water uptake, and preferential flow. Typical models based on the Richards equation include HYDRUS, SWAP (Soil-Water-Atmosphere-Plant Model), SHAW (Simultaneous Heat and Water Model), COUPMODEL (Coupled Heat and Water Flow Model), and various dual-domain preferential flow models.

The van Genuchten–Mualem model [164] proposed unified hydraulic functions for unsaturated soils, forming the theoretical foundation for contemporary soil water flow modeling. During the 1990s, the HYDRUS model family [155,165] used the finite-element method to solve the Richards equation, enabling simulations of variably saturated water flow, solute transport, and coupled heat–water–vapor processes, and has been widely applied in drip irrigation, salinity leaching, and vadose-zone studies. Contemporaneously, the SWAP [166] model integrated surface energy balance with root water uptake to analyze evaporation–transpiration partitioning, deep percolation, and crop–soil interactions. Meanwhile, the SHAW model [167] emphasized coupled water, heat, and freeze–thaw dynamics and has been extensively used in cold-region agro-ecosystems and frozen-soil hydrology. Entering the 2000s, COUPMODEL [168] extended coupled heat- and water-flow modeling by incorporating carbon and nitrogen cycles, enabling its use in high-latitude agricultural freeze–thaw processes and forest–crop system comparisons. Additionally, to represent rapid flow in macroporous, fractured, or swelling soils, Gerke & van Genuchten [169] introduced a dual-permeability/dual-domain model that divides soil into matrix and macropore domains with exchange fluxes, and this approach has been widely applied in studies of rainfall-runoff generation and pesticide transport.

Field-scale models provide high physical realism and predictive capability for complex hydrological processes, but consequently require more detailed parameters, boundary conditions, and computational resources.

4.2. Watershed-Scale Hydrological Models

Unlike field-scale models that focus on water dynamics within individual plots, watershed-scale hydrological models are capable of integrating spatial heterogeneity and capturing the influences of topography, soil variability, and land-use patterns on runoff generation and water regulation, thereby supporting flood forecasting, watershed management, and large-scale water resource assessment. Watershed-scale models can be broadly categorized into conceptual water-balance models and physics-based distributed models, with the former including lumped and semi-distributed conceptual structures, and the latter including distributed soil-water–runoff models and high-resolution coupled hydrological models.

4.2.1. Conceptual Models

Conceptual models are generally built upon the watershed water-balance equation:

|

```latex\frac{dS}{dt}=P-ET-{Q}_{s}-{Q}_{g}``` |

where S represents watershed water storage, P precipitation, ET evapotranspiration, Qₛ surface runoff, and Q𝗀 groundwater runoff. This equation describes the overall hydrological relationship among precipitation inputs, evapotranspiration losses, changes in water storage, and both surface and subsurface flows at the watershed scale. Owing to their simple structure and modest data requirements—parameters can typically be estimated from watershed hydrological observations and meteorological datasets—these models are well suited for water-resource evaluation, flood forecasting, and climate-change impact analysis. Representative conceptual models include the HBV (Hydrologiska Byråns Vattenbalansavdelning Model) model developed in the mid-1970s [157], TOPMODEL, which introduced a topographic wetness index to simulate distributed soil-moisture and subsurface flow processes [170], the SWAT model, whose conceptual structure divides the watershed into sub-basins and hydrological response units for long-term water-quantity and water-quality simulation [156], and the VIC model, whose conceptual version employs a multilayer soil-water and energy-balance framework suitable for large-scale climate-impact hydrology [171].

Although computationally efficient and relatively straightforward to calibrate, conceptual models have limited capability in resolving micro-topographic variations, spatially explicit soil and land-surface heterogeneity, and nonlinear flow processes that strongly influence watershed hydrological responses.

4.2.2. Physics-Based Hydrological Models

Physics-based hydrological models are commonly based on fully distributed three-dimensional process equations. Surface-water flow (shallow-water/Saint–Venant equations):

|

```latex\frac{\partial h}{\partial t}=\frac{\partial \left(uh\right)}{\partial x}+\frac{\partial \left(vh\right)}{\partial y}=R-I``` |

where h is water depth, u and v are depth-averaged velocities in the x and y directions, and R is the source–sink term representing bed-slope forcing.

Groundwater flow (Darcy’s law):

|

```latex\bm{q}=-\bm{K}\nabla h``` |

where q is the three-dimensional flow vector (m/s), K is the hydraulic-conductivity tensor (possibly anisotropic), and ∇h is the hydraulic-head gradient. These models perform spatial–temporal simulation of watershed hydrological cycles by explicitly describing precipitation infiltration, soil-moisture dynamics, surface-runoff generation, channel flow, and energy fluxes. Common models include MIKE SHE, DHSVM (Distributed Hydrology Soil Vegetation Model), ParFlow (Parallel Flow Model), and SWAT-M.

MIKE SHE [172] integrates the Richards equation, surface-water flow equations, and an energy-balance scheme to enable detailed watershed-scale hydro-thermal simulation. DHSVM [173] incorporates high-resolution topography, vegetation, and soil data, along with coupled energy–water fluxes, to simulate snow, soil-moisture, vegetation processes, and runoff generation in a unified framework. ParFlow [174] solves the three-dimensional Richards equation, along with surface-flow coupling formulations, enabling physically based simulation of variably saturated flow and surface–subsurface interactions at large-watershed scales. MODFLOW(Modular Three-Dimensional Finite-Difference Groundwater Flow Model) [175,176], based on the 3-D groundwater-flow governing equation, can simulate aquifer hydraulic heads, recharge and discharge, stream–aquifer interactions, and pumping impacts. When coupled with SWAT, MIKE SHE, or other models, it is widely used for integrated surface–subsurface watershed modeling. Furthermore, improved models such as SWAT-M [177] introduce distributed soil-water and crop-transpiration modules into the original conceptual structure, increasing spatial detail while maintaining computational efficiency.

Watershed-scale models can accurately represent spatial heterogeneity and rapid hydrological responses. However, achieving high-precision physical-process simulation requires extensive data, numerous parameters, and substantial computational resources. Meanwhile, lumped or semi-distributed conceptual models still face limitations in capturing micro-topography and nonlinear hydrological responses within complex basins.

Although hydrological models at field, watershed, and integrated scales have been widely developed and applied in various regions, their performance in cold-region irrigated areas remains generally limited or unsatisfactory. The main challenges arise from the difficulty of simultaneously representing freeze–thaw dynamics, soil water–heat interactions, irrigation management, and canal-network effects. As a result, models often fail to accurately capture soil moisture redistribution, crop–water interactions, groundwater–surface water exchange, and water-salt dynamics under cold irrigated conditions. This highlights a clear gap in current hydrological modeling, emphasizing the need for targeted adaptation, calibration, and long-term observational data to improve model reliability and decision support in cold-region irrigated areas.

4.3. Coupled Models for Hydrological Processes

In many hydrological systems, precipitation infiltration, surface runoff, river–groundwater exchange, soil moisture movement, and three-dimensional groundwater flow are tightly interconnected; relying on a single model often fails to represent the full water cycle. To address these limitations, recent decades have seen widespread adoption of integrated surface–vadose–groundwater coupling models that simulate the entire cascade—from overland flow to aquifer recharge—within a unified framework.

A widely used example is SWAT+MODFLOW [178], which links a comprehensive land-surface/soil-plant-atmosphere model with a fully distributed groundwater model to quantify recharge, soil–groundwater exchange, canal seepage, irrigation pumping, and stream–aquifer interactions under managed-watershed conditions.

Another classical implementation is GSFLO [179], which integrates the PRMS precipitation–runoff model with MODFLOW, enabling simultaneous simulation of infiltration, overland flow, streamflow, baseflow, and saturated groundwater dynamics across entire watersheds.

Extensions of these frameworks continue to appear. For instance, SWAT+gwflow [180] improves the representation of groundwater–surface water interactions within SWAT+, providing refined groundwater flow processes under irrigation and climate-variability conditions.

Applications of SWAT–MODFLOW have also demonstrated the importance of coupled modeling in regions where pumping, irrigation, and land-use change strongly modify recharge and baseflow.

Overall, these integrated coupling models provide [181] a unified representation of overland flow, infiltration, vadose-zone water redistribution, groundwater recharge and discharge, stream–aquifer exchange, and anthropogenic interventions. As a result, they are now widely applied in irrigation management, groundwater sustainability assessment, flood and drought prediction, land-use change evaluation, and climate-impact analysis.

5. Hydrological Response of Cold-Region Irrigation Districts to Climate Warming and Extreme Events

5.1. Characterizing Climate Change in Cold Regions

In recent years, the trajectory of global warming has intensified. NOAA’s global monitoring indicates that May 2025 registered the second-warmest May in the 176-year record (anomalies of +1.10 °C relative to the 20th-century mean). [182], and January–July 2025 ranks second-warmest for the year-to-date, just 0.10 °C below the 2024 record pace [183]. Consistent with these observations, the WMO Global Annual to Decadal Climate Update (2025–2029) projects the global mean near-surface temperature each year to be 1.2–1.9 °C above the 1850–1900 baseline, with an 86% probability that at least one year in 2025–2029 will exceed 1.5 °C, and a 70% probability that the five-year mean will do so as well—posing a direct challenge to the Paris Agreement’s temperature goal. Independent coverage of the WMO update further underscores amplified Arctic warming, expected at >3.5× the global average and about +2.4 °C above the recent 30-year baseline in the coming winters [184].

Precipitation regimes and extremes are shifting in tandem. Canonical “wet-gets-wetter, dry-gets-drier” responses and increases in heavy precipitation and hydroclimatic extremes are assessed with high confidence in recent syntheses (IPCC AR6), reflecting a warmer atmosphere’s enhanced moisture-holding capacity and changing circulation [185]. Observationally, 2024–2025 featured widespread pluvial and drought episodes that stressed water-resource systems and agricultural irrigation demands, with sea-surface temperature and surface-air temperature anomalies reinforcing extreme hydrological loading [186]. High-latitude and cold-region basins emerge as particularly sensitive “hotspots” under warming, with projected increases in cool-season precipitation and a higher fraction of intense convective rainfall that challenge legacy flood-control and irrigation infrastructure [184].

Concurrently, extreme heat has become a hallmark of the evolving climate. During June–July 2025, Europe endured a severe heatwave; Portugal observed nation-leading maxima near 46–47 °C (e.g., 46.8 °C at Coruche and 46.6 °C at Santarém), amid reports of substantial excess mortality linked to heat stress [105,184]. In South Asia, an April 2025 heat episode drove temperatures to ~48 °C in parts of India and Pakistan, with documented public health and agricultural impacts [187].

With global temperatures continuing to reach new records, the frequency and intensity of extreme climatic events are rising sharply, and precipitation patterns are becoming increasingly volatile. High-latitude and cold-region areas exhibit particularly strong sensitivity to extreme events—defined as the amplified response of hydrological systems to changes in the intensity, return period, or duration of extreme meteorological events such as extreme rainfall, drought, or heatwaves—which introduces greater instability into hydrological processes and irrigation management in cold-region irrigation districts [184,188,189]. The frequent alternation of heatwaves, heavy rainfall, and drought is reshaping the mechanisms governing the formation and decay of frozen layers, as well as the timing and magnitude of water replenishment, bringing substantial uncertainty and challenges to agricultural water-resource regulation [190,191,192,193,194]. Data sources are presented in Table A1.

5.2. Response of Hydrological Processes in CRIDs to Climate Warming and Extreme Events

With the intensification of global climate change, the increasing frequency of extreme weather events—including extreme precipitation (e.g., heavy rainfall, snow, and freezing rain), extreme temperature events (e.g., sudden thawing and rapid snowmelt), and extreme droughts—has introduced greater uncertainty into hydrological processes and irrigation management under freeze-thaw conditions [195,196]. The alternation of droughts and heavy rainfall exacerbates the volatility of hydrological processes in cold-region irrigation districts [31]. Extreme droughts lead to insufficient groundwater recharge, necessitating increased irrigation intensity; whereas extreme rainfall events can trigger large-scale surface runoff and soil erosion, reducing soil moisture retention capacity [197]. Under rapidly shifting freeze–thaw conditions, the abrupt alternation between extreme drought and intense rainfall amplifies soil structural instability, because freeze–thaw cycles weaken soil aggregates and reduce infiltration capacity. This makes hydrological responses more volatile and difficult to predict, thereby increasing uncertainty in irrigation scheduling and agricultural production.

In the spring of 2024, Heilongjiang Province experienced an extreme drought lasting two months, resulting in a drop in groundwater levels and severe soil moisture deficits, which adversely affected crop growth [179]. According to data from the agricultural department, wheat and maize yields decreased by 15% and 20%, respectively. However, in the summer of the same year, the region experienced heavy rainfall, leading to large-scale surface runoff and soil erosion, which affected the infiltration and retention capacity of soil moisture [195]. This “drought-rain” alternating extreme weather phenomenon has intensified the management challenges of irrigation systems [198]. Particularly under extreme climatic conditions, how to adjust irrigation strategies in a timely and accurate manner has become an urgent issue [199].

Meanwhile, climate warming has led to reduced freeze depth and shortened freeze-thaw cycles, making the responses of hydrological processes more frequent and rapid [200,201]. The acceleration of freeze-thaw cycles has, to some extent, promoted water migration efficiency, activated the hydrological cycle in irrigation districts, and facilitated the dynamic utilization and recycling of water resources. Recent observational data from Heilongjiang Province indicate that the average duration of the freeze-thaw cycle has shortened from 120 days to approximately 100 days, and the depth of frozen soil has decreased by 20–30% [202]. This change has accelerated the turnover rate of soil moisture and enhanced water migration efficiency, making the hydrological cycle in irrigation districts more active, and contributing to the dynamic utilization and recycling of water resources. In some areas, the shortening of the freeze-thaw cycle has even improved soil moisture conditions in spring, providing more adequate water support for crops. In the spring of 2023, certain farmlands in Heilongjiang Province experienced an earlier release of meltwater, resulting in soil moisture levels approximately 10% higher than the long-term average, giving crops a favorable start [203].

However, shortening of the freeze–thaw cycle also introduces new challenges: the intensifying occurrence of extreme drought and heavy rainfall makes hydrological processes more volatile and increases uncertainty in irrigation management [204]. Observations from Alberta, Canada, show that, as the climate warms, the depth of frozen soil decreases year by year, and the earlier release of spring meltwater leads to insufficient soil moisture [205]. This results in a substantial rise in agricultural water demand, forcing farmers to increase irrigation intensity to compensate for the moisture deficit.

At the irrigation-management level, different irrigation methods exhibit distinct responses to variations in climatic factors. Taking the Hetao Irrigation District in Inner Mongolia, China, as an example, the region’s traditional surface irrigation is strongly influenced by the freeze–thaw cycle and precipitation processes [133]. In early spring, lower temperatures and reduced evapotranspiration demand help minimize conveyance losses. However, under hot, low-humidity conditions with strong evaporation, sprinkler and center-pivot irrigation—although capable of improving water-use efficiency—incur additional energy consumption due to pump operation. In contrast, the increasingly adopted drip irrigation is relatively less sensitive to changes in temperature, humidity, and evapotranspiration (ET), and can significantly reduce evaporative losses in dry years while increasing crop output per unit of water [206]. Therefore, air temperature determines evapotranspiration demand and energy load; humidity influences the level of evaporative loss under sprinkler irrigation; rainfall and snowfall determine the magnitude of spring irrigation supply; and ET provides the direct basis for regulating irrigation intensity across different irrigation systems.

These interactions highlight that the synergy between irrigation practices and climatic conditions is particularly pronounced in cold regions, underscoring the need for adaptive irrigation-system research under changing freeze–thaw regimes.

In the context of climate warming leading to reduced freeze depth, shortened freeze-thaw cycles, and increased frequency of extreme weather events, the agricultural production system in cold-region irrigation districts must enhance its adaptive capacity. Based on the changes in freeze-thaw and hydrological processes, scientifically formulating dynamic irrigation strategies is particularly important [207]. It is necessary to optimize and adjust planting structures according to the temporal and spatial dynamics of soil moisture, scientifically develop irrigation plans to match the changes in soil moisture patterns, reduce water waste, and improve water use efficiency. Under different groundwater table depths and frozen soil conditions, differentiated irrigation strategies are crucial. For example, in areas with shallow groundwater tables, attention should be paid to the impact of elevated groundwater levels during the freezing period on root zone moisture conditions, while in areas with deep groundwater tables, fine-tuned irrigation techniques can be employed to reduce excessive interaction between surface water and groundwater, achieving steady-state regulation of the hydrological system [136].

In summary, integrating irrigation management with dynamic coupling analysis of freeze-thaw and hydrological processes is of significant guiding importance for enhancing the response capacity of cold-region irrigation districts to climate warming and extreme events, achieving sustainable water resource utilization, and ensuring stable agricultural production [19,25,32,33,207,208,209,210].

6. Challenges and Perspectives in the Study of Hydrological Processes in Irrigated Cold Regions

As understanding of hydrological processes in cold-region irrigation districts has deepened, research has gradually shifted from single-factor observations toward integrated, multi-process and multi-scale simulation frameworks. However, constrained by the complexity of freeze–thaw mechanisms, the diversity of agricultural management, and the growing uncertainty of extreme climate conditions, substantial theoretical and technical challenges remain [211]. Future development, therefore, requires not only breakthroughs in hydrological mechanism research but also an expansion to an integrated agricultural–ecological–carbon perspective to support sustainable development of cold-region irrigation systems [212].

6.1. Major Challenges in Current Research

There remain clear deficiencies in the physical representation of freeze–thaw phase change. Although some models have introduced energy-balance and three-phase transport formulations, many still treat freezing and thawing as a binary switch and cannot capture the nonlinear dynamics of ice content and microscopic migration processes; this limitation becomes especially evident under extreme events—for example, rapid snowmelt can induce characteristic “V-shaped” groundwater responses that many current models struggle to reproduce.

Building on this, the interactive mechanisms between irrigation management and freeze–thaw cycles are also insufficiently represented. Most mainstream hydrological models were developed within natural-ecosystem frameworks and lack detailed modules for winter irrigation timing, amount allocation, and root-zone uptake processes; consequently, they fail to capture field-scale phenomena such as the “ice-bank” (or “ice-reservoir”) effect documented in some Chinese irrigation districts, weakening the models’ applicability to practical agricultural management.

Looking further, multi-scale simulation of strongly transient hydrological dynamics systems remains a major bottleneck. Hydrological processes in cold-region irrigation districts span surface water, the vadose zone, and groundwater and display pronounced seasonal transient hydrological dynamics. Maintaining mechanistic consistency and comparability of results across plot–district–catchment scales remains a core challenge for model integration and upscaling.

In cold-region hydrological modeling, long-term efforts have been constrained by the lack of critical observational data, especially during the freezing period and the early thaw. Core processes such as three-phase migration, groundwater recharge, and crop responses lack continuous, high-resolution monitoring—significantly increasing the uncertainty in model calibration and validation [213,214]. Meanwhile, parameterization in the Richards equation remains the main bottleneck limiting model applicability: direct parameterization—though more accurate—is expensive, poorly representative, and challenging to reflect the dynamic soil-structure changes caused by freeze–thaw [19]; indirect parameterization relies on empirical relationships, databases, or inversion methods, which may work at regional scale, but under freeze–thaw and three-phase coexistence conditions present high uncertainty and limited generality. Overall, the temperature sensitivity and structure-dependence of cold-region soil hydraulic parameters remain systematically quantified, and there is an urgent need to establish a parameterization framework that is transferable across scales.

More importantly, current hydrological-process research still clearly under-represents considerations of the carbon cycle and ecological effects. Existing studies show that winter irrigation and rapid snowmelt not only alter water-quantity processes. However, they may also mobilize plant-derived carbon (for example, dissolved organic carbon produced by root respiration or litter decomposition, and biogenic CO2) via surface runoff or percolating water—and field observations in Heilongjiang’s irrigation districts have documented these pathways; see also broader analyses of irrigation runoff effects on stream DOC loads [215]. Such mobilization can alter ecosystem carbon budgets. In permafrost-degrading regions (e.g., Siberia), accelerated thawing increases CO2 and CH4 emissions and produces substantial feedbacks to the climate system [216,217]. In Xinjiang’s irrigated areas, long-term large-scale flood irrigation, while improving soil moisture conditions, can promote coupled transport and redistribution of plant-derived carbon and salts—thereby affecting soil microhabitats, crop growth, and the region’s carbon-sink capacity. However, these “water–carbon trade-off” effects have not yet been systematically incorporated into hydrological modeling and management frameworks for cold-region irrigation districts.

6.2. Future Research Directions

Looking ahead, hydrological research in cold-region irrigation districts needs to achieve breakthroughs and expansions in the following areas:

Deepening the Nonlinear Coupling Mechanisms of Freeze–Thaw–Water–Heat–Salt Processes: By improving the physical description of phase change processes and introducing microscopic-scale ice–liquid water migration mechanisms, models can better reproduce the advance of freezing fronts, latent heat release, and abrupt changes in water–heat fluxes. This will aid in explaining and predicting abnormal runoff and groundwater responses under extreme climate conditions [218,219].

Developing Dynamic Modules for Crop Growth and Irrigation Management: Future models should not only represent natural processes but also integrate crop water demand curves, root distribution, and tillage disturbances to form a unified framework of “crop–irrigation–freeze–thaw”. For instance, the VIC–CropSyst model coupling irrigation scheduling with crop growth states can enhance model applicability in agricultural decision-making [55,220].

Promoting Multi-Scale Observation and Model Validation: Conducting detailed field-scale observations, combined with remote sensing, big data, and groundwater monitoring, enables cross-scale integration from point to area. Hybrid models based on physical–data fusion (e.g., physics-constrained LSTM, data-driven Richards equation surrogate models) are expected to improve efficiency and accuracy in large-scale applications while maintaining physical consistency [221,222,223,224].

Fourth, strengthen integrated studies on water–carbon–ecology processes. Future research should not be limited to “water use efficiency” but should be expanded to include “water–carbon trade-offs” and “water–ecology synergies”. On the irrigated-area scale, focus should be placed on how irrigation activities influence the flux and redistribution of plant-derived carbon (e.g., dissolved organic carbon from root respiration or litter decomposition, and biogenic CO2) within the hydrological cycle, and how this regulates carbon-sink potential; on the watershed scale, one needs to assess feedback mechanisms from hydrological process changes on wetland carbon budgets and biodiversity. For example, although winter irrigation in the Heilongjiang irrigation districts improves spring soil moisture, it may—via runoff or infiltration—carry plant-derived dissolved organic carbon into water bodies, thereby affecting regional fields [225,226,227].

Addressing Climate Change and Extreme Event Uncertainty: Climate warming reduces freezing depth and shortens freeze–thaw cycles, leading to alternating extreme droughts and heavy rains, thereby requiring future irrigation district management to be more adaptable. Dynamic early warning systems based on simulation–observation integration can support differentiated irrigation strategies, such as focusing on the impact of winter irrigation on water table elevation in shallow groundwater areas and reducing water–carbon loss through precision irrigation in deep groundwater areas [24,195].

In summary, hydrological research in cold-region irrigation districts is transitioning from “hydrological process analysis” to a new stage of “water–carbon–ecosystem integrated assessment”. Only through the joint advancement of mechanism deepening, model enhancement, and interdisciplinary integration can coordinated and sustainable development of agriculture, water resource utilization, and ecological security in cold regions be achieved under the backdrop of intensified climate change and extreme events [135,228,229].

Appendix A

Table A1. Summary of All Climate Datasets and Statistical Characteristics Used in This Review.

|

No. |

Dataset Name |

Data Source |

Variables |

Time Range |

Missing Value Ratio |

Zero Value Ratio |

Primary Statistics (Mean/SD/Skewness/Kurtosis) |

Double-Period Statistics (Annual/Monthly) |

Cross-Correlation with Temperature/Precipitation |

Download Link |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1 |

Global Land Surface Temperature (Global Mean) |

NOAA GlobalTemp v5 |

Monthly temperature anomaly (°C) |

2000–2025 |

<0.1% |

0% |

0.82/0.19/–0.12/3.11 |

Annual amplitude: ~0.21 °C; Monthly SD: 0.18 °C |

Weak negative r ≈ −0.20 to −0.35 (vs. precipitation; lag 0–1 month) |

https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/products/land-based-temperature (accessed on 23 November 2025). |

|

2 |

Global Land Precipitation (GPCC v2023) |

GPCC |

Monthly precipitation (mm) |

2000–2025 |

0.5–1.2% |

3–7% (arid regions) |

78.5/41.3/1.81/5.92 |

Annual amplitude: 24.6 mm; strongly monsoon-driven |

Weak negative r ≈−0.25 to −0.45 (vs. temperature; lag 0–1 month) |

https://opendata.dwd.de/climate_environment/GPCC/html/download_gate.html (accessed on 23 November 2025). |

|

3 |

Reanalysis 2 m Air Temperature |

ERA5 |

2 m temperature (°C) |

2000–2025 |

<0.01% |

0% |

12.3/13.6/0.29/2.87 |

Diurnal amplitude: 7–14 °C; Seasonal amplitude: 20–25 °C |

r ≈−0.15 to −0.30 (vs. precipitation; region-dependent) |

https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu (accessed on 23 November 2025). |

|

4 |

Extreme Temperature Indicators (Heatwaves) |

ERA5/WMO |

Tx, heatwave days |

2000–2025 |

<0.01% |

0% |

Tx: 21.1/8.2/0.71/4.62 |

Annual cycle explains >90% of variance |

Positive r ≈ 0.40 to 0.60 (Temp vs. TXx) |

https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu (accessed on 23 November 2025). |

|

5 |

High-latitude/Arctic Climate Indicators |

ERA5/WMO |

Temperature, precipitation |

2000–2025 |

<0.01% |

0% |

Arctic warming rate: +0.74°C/decade |

Strong seasonal contrast; summer precipitation increases |

r ≈ –0.30 to −0.55 (Temp vs. Precip) |

https://public.wmo.int (accessed on 23 November 2025). |

|

6 |

CMIP6 Multi-Model Ensemble (Scenario Comparison) |

CMIP6 |

Temperature, precipitation, extremes |

2000–2025 (historical segment) |

Model-dependent |

N/A |

Multi-model ensemble statistics |

Used for inter-model consistency only |

N/A (not suitable for single-series correlation) |

https://esgf-node.llnl.gov/projects/cmip6 (accessed on 23 November 2025). |

|

7 |

Global Land Station Data (GHCN-Daily) |

NOAA |

TMAX, TMIN, precipitation |

2000–2025 |

0.5–5% |

0–2% |

TMAX often right-skewed; precipitation strongly skewed |

Strong seasonality; region-dependent |

r ≈−0.10 to −0.30 (TMAX vs. precipitation) |

https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/products/land-based-station-data (accessed on 23 November 2025). |

Statement of the Use of Generative AI and AI-Assisted Technologies in the Writing Process

During the preparation of this manuscript, we used GPT (ChatGPT, OpenAI) to assist with language refinement. After using this tool, we reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the published article.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.M. and X.T.; Methodology, X.T.; Investigation, Y.M.; Resources, L.L.; Data Curation, Y.Z.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, Y.M.; Writing—Review & Editing, X.T.; Visualization, Y.Z.; Supervision, X.T.; Project Administration, X.T.; Funding Acquisition, X.T.

Ethics Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data is available upon request.

Funding

This research was funded by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (2022SCU12113) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (51909175).

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

-

Capps S. The Cold Bay District. U.S. Geol. Surv. Bull. 739-C 1922, 77–116. doi:10.3133/b739C. [Google Scholar]

-

Ivanov O, Utenkov G, Ivanova T. Solution for Surface Irrigation in Agrolandscapes of Central Siberia. In Exploring and Optimizing Agricultural Landscapes; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 707–719. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-67448-9_38. [Google Scholar]

-

Cheng J-P. Design Preventing Frozen Bulge Damage of Irrigation Canals in Bad Cold Area. J. Irrig. Drain. 2007, 26, 65–68. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Design-Preventing-Frozen-Bulge-Damage-of-Irrigation-Jian-ping/2e3320913af0e94f744424a385fcb7ac64d28c70 (accessed on 26 December 2025). [Google Scholar]

-

Hao W, Li Z, Gong Y, Zhang W, Gilkes R, Prakongkep N. Siberian wildrye grass yield and water use response to single irrigation time in semiarid agropastoral ecotone of North China. In Proceedings of the 19th World Congress of Soil Science, Soil Solutions for a Changing World, Brisbane, Australia, 1–6 August 2010; pp. 153–156. [Google Scholar]

-

Demin A. Transformation of water and land use in irrigated agriculture in Siberian regions (1990–2020). Bull. NSAU (Novosib. State Agrar. Univ.) 2022, 3, 26–35. doi:10.31677/2072-6724-2022-64-3-26-35. [Google Scholar]

-

Zaremehrjardy M, Victor J, Park S, Smerdon B, Alessi D, Faramarzi M. Assessment of snowmelt and groundwater-surface water dynamics in mountainous, foothill, and plain regions in northern latitudes. J. Hydrol. 2022, 606, 127449. doi:10.1016/j.jhydrol.2022.127449. [Google Scholar]

-

Amer R. Spatial Relationship between Irrigation Water Salinity, Waterlogging, and Cropland Degradation in the Arid and Semi-Arid Environments. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 1047. doi:10.3390/rs13061047. [Google Scholar]

-

Nachshon U. Cropland Soil Salinization and Associated Hydrology: Trends, Processes and Examples. Water 2018, 10, 1030. doi:10.3390/w10081030. [Google Scholar]

-

Hiyama T, Yang D, Kane D. Permafrost Hydrology: Linkages and Feedbacks. In Arctic Hydrology, Permafrost and Ecosystems; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 471–491. [Google Scholar]

-

Andresen CG, Lawrence DM, Wilson CJ, McGuire AD, Koven C, Schaefer K, et al. Soil moisture and hydrology projections of the permafrost region—A model intercomparison. Cryosphere 2020, 14, 445–459. doi:10.5194/tc-14-445-2020. [Google Scholar]

-

Jin H, Huang Y, Bense VF, Ma Q, Marchenko SS, Shepelev VV, et al. Permafrost Degradation and Its Hydrogeological Impacts. Water 2022, 14, 372. doi:10.3390/w14030372. [Google Scholar]

-

Xie H, Jiang X, Tan S, Wan L, Wang X-S, Liang S, et al. Interaction of soil water and groundwater during the freezing–thawing cycle: Field observations and numerical modeling. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2021, 25, 4243–4257. doi:10.5194/HESS-25-4243-2021. [Google Scholar]

-

Qin J, Ding Y-J, Shi F, Cui J, Chang Y, Han T, et al. Links between seasonal suprapermafrost groundwater, the hydrothermal change of the active layer, and river runoff in alpine permafrost watersheds. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2024, 28, 973–987. doi:10.5194/hess-28-973-2024. [Google Scholar]

-

Zhang F-W, Li H-Q, Li Y, Guo X, Dai L, Lin L, et al. Strong seasonal connectivity between shallow groundwater and soil frost in a humid alpine meadow, northeastern Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. J. Hydrol. 2019, 574, 926–935. doi:10.1016/J.JHYDROL.2019.05.008. [Google Scholar]

-

Lyu H, Li H, Zhang P, Cheng C, Zhang H, Wu S, et al. Response Mechanism of Groundwater Dynamics to Freeze–thaw Process in Seasonally Frozen Soil Areas: A Comprehensive Analysis from Site to Regional Scale. J. Hydrol. 2023, 625, 129861. doi:10.1016/j.jhydrol.2023.129861. [Google Scholar]

-

Hayashi M. The Cold Vadose Zone: Hydrological and Ecological Significance of Frozen-Soil Processes. Vadose Zone J. 2013, 12, 1–8. doi:10.2136/vzj2013.03.0064. [Google Scholar]

-

Zhang X, Sun S. The impact of soil freezing/thawing processes on water and energy balances. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 2011, 28, 169–177. doi:10.1007/S00376-010-9206-0. [Google Scholar]

-

Beran J, Feng Y, Ghosh S, Kulik R. Long-Memory Processes; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 43–106. [Google Scholar]

-

Wang P, Liu Z, Wang C, Zhang C, Wang W, Wang X, et al. A novel soil water-heat-salt coupling model for freezing-thawing period in farmland with shallow groundwater. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2025, 57, 102099. doi:10.1016/j.ejrh.2024.102099. [Google Scholar]

-

Huang X, Rudolph D. Numerical Study of Coupled Water and Vapor Flow, Heat Transfer, and Solute Transport in Variably-Saturated Deformable Soil During Freeze-Thaw Cycles. Water Resour. Res. 2023, 59, e2022WR032146. doi:10.1029/2022WR032146. [Google Scholar]

-

Dimitriadis P, Koutsoyiannis D, Iliopoulou T, Papanicolaou P. A Global-Scale Investigation of Stochastic Similarities in Marginal Distribution and Dependence Structure of Key Hydrological-Cycle Processes. Hydrology 2021, 8, 59. doi:10.3390/hydrology8020059. [Google Scholar]

-

Hurst HE. Long-Term Storage Capacity of Reservoirs. Trans. Am. Soc. Civ. Eng. 1951, 116, 770–799. doi:10.1061/TACEAT.0006518. [Google Scholar]

-

Li M, Duan J-S, Heydari MH, Chen Y. Editorial: Long-range dependent processes: Theory and applications, volume II. Front. Phys. 2024, 12, 1449462. doi:10.3389/fphy.2024.1449462. [Google Scholar]

-

Scholl M, McCabe G, Olson C, Powlen K. Climate Change and Future Water Availability in the United States, 1894E; US Geological Survey: Reston, VA, USA, 2025; p. 72. [Google Scholar]

-

Zhang X, Zhang Y, Qi J, Marek GW, Srinivasan R, Feng P, et al. Effects of Changes in Freeze-Thaw Cycles on Soil Hydrothermal Dynamics and Erosion Degradation Under Global Warming in the Black Soil Region. Water Resour. Res. 2025, 61, e2024WR038318. doi:10.1029/2024WR038318. [Google Scholar]

-

Stavi I, Thevs N, Priori S. Soil Salinity and Sodicity in Drylands: A Review of Causes, Effects, Monitoring, and Restoration Measures. Front. Environ. Sci. 2021, 9, 712831. doi:10.3389/fenvs.2021.712831. [Google Scholar]

-

Hassani A, Azapagic A, Shokri N. Global predictions of primary soil salinization under changing climate in the 21st century. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 6663. doi:10.1038/s41467-021-26907-3. [Google Scholar]

-

Peng S, Xu X, Liao R, He B, Mihara K, Kuramochi K, et al. Hydro-climatic extremes shift the hydrologic sensitivity regime in a cold basin. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 949, 174744. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.174744. [Google Scholar]

-

Li B, Rodell M. How Have Hydrological Extremes Changed over the Past 20 Years? J. Clim. 2023, 36, 8581–8599. doi:10.1175/JCLI-D-23-0199.1. [Google Scholar]

-

Mohanavelu A, Naganna SR, Al-Ansari N. Irrigation Induced Salinity and Sodicity Hazards on Soil and Groundwater: An Overview of Its Causes, Impacts and Mitigation Strategies. Agriculture 2021, 11, 983. doi:10.3390/agriculture11100983. [Google Scholar]

-

Bărbulescu A, Costache R, Dumitriu CȘ. Climate Change and Hydrological Processes. Water 2025, 17, 1474. doi:10.3390/w17101474. [Google Scholar]

-

Liu S, Huang Q, Zhang W, Ren D, Huang G. Improving soil hydrological simulation under freeze–thaw conditions by considering soil deformation and its impact on soil hydrothermal properties. J. Hydrol. 2023, 619, 129336. doi:10.1016/j.jhydrol.2023.129336. [Google Scholar]

-

Li B, Tan L, Zhang X, Qi J, Marek GW, Feng P, et al. Enhanced Freeze-Thaw Cycle Altered the Simulations of Groundwater Dynamics in a Heavily Irrigated Basin in the Temperate Region of China. Water Resour. Res. 2024, 60, e2023WR036151. doi:10.1029/2023WR036151. [Google Scholar]

-

Li X, Chen X, Gao Y, Yang J, Ding W, Zvomuya F, et al. Freezing induced soil water redistribution: A review and global meta-analysis. J. Hydrol. 2025, 651, 132594. doi:10.1016/j.jhydrol.2024.132594. [Google Scholar]

-

Lamontagne-Hallé P, McKenzie J, Kurylyk B, Molson J, Lyon L. Guidelines for cold-regions groundwater numerical modeling. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Water 2020, 7, e1467. doi:10.1002/wat2.1467. [Google Scholar]

-

Yang X, Hu J, Sun Z. Integrated Hydrologic Modelling of Groundwater-Surface Water Interactions in Cold Regions. Front. Earth Sci. 2021, 9, 721009. doi:10.3389/feart.2021.721009. [Google Scholar]

-

Amani A, Boucher MA, Cabral AR, Vionnet V, Gaborit É. Cold climates, complex hydrology: Can a land surface model accurately simulate deep percolation? Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2025, 29, 2445–2465. doi:10.5194/hess-29-2445-2025. [Google Scholar]

-

Yang YF, Wang CX, He XL, Wang HX, Wang Y, Zhou FY, et al. Study on the effects of winter irrigation during seasonal freezing-thawing period on soil microbial ecological properties. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 23586. doi:10.1038/s41598-025-07845-2. [Google Scholar]

-

Demo AH, Gemeda MK, Abdo DR, Guluma TN, Adugna DB. Impact of soil salinity, sodicity, and irrigation water salinity on crop production and coping mechanism in areas of dryland farming. Agrosyst. Geosci. Environ. 2025, 8, e70072. doi:10.1002/agg2.70072. [Google Scholar]

-

Groff T, Pomeroy J. Snowmelt Infiltration and Runoff From Seasonally Frozen Hillslopes in a High Mountain Basin. Hydrol. Process. 2025, 39, e70048. doi:10.1002/hyp.70048. [Google Scholar]

-

Bauder J, Brun L, Krueger T. The Relationship of Soil Freezing to Snowmelt Runoff. North Dak. Farm Res. 1975, 32, 10–13. [Google Scholar]

-

Ridge N, Rush M, Rajaram H. Influence of Snowpack Cold Content on Seasonally Frozen Ground and Its Hydrologic Consequences: A Case Study From Niwot Ridge, CO. Water Resour. Res. 2022, 58, e2021WR031911. doi:10.1029/2021WR031911. [Google Scholar]

-

Wu T, Li H, Lyu H. Effect of freeze–thaw process on heat transfer and water migration between soil water and groundwater. J. Hydrol. 2022, 617, 128987. doi:10.1016/j.jhydrol.2022.128987. [Google Scholar]

-

Zheng X, Flerchinger G. Infiltration into Freezing and Thawing Soils under Differing Field Treatments. J. Irrig. Drain. Eng. 2001, 127, 176–182. doi:10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9437(2001)127:3(176). [Google Scholar]

-

Xiuqing Z, Van Liew M, Flerchinger G. EXPERIMENTAL STUDY OF INFILTRATION INTO A BEAN STUBBLE FIELD DURING SEASONAL FREEZE-THAW PERIOD. Soil Sci. 2001, 166, 3–10. doi:10.1097/00010694-200101000-00002. [Google Scholar]

-

Qi J, Li S, Li Q, Xing Z, Bourque CPA, Meng F-R. A new soil-temperature module for SWAT application in regions with seasonal snow cover. J. Hydrol. 2016, 538, 863–877. doi:10.1016/j.jhydrol.2016.05.003. [Google Scholar]

-

Schilling O, Park Y-J, Therrien R, Nagare R. Integrated Surface and Subsurface Hydrological Modeling with Snowmelt and Pore Water Freeze-Thaw. Groundwater 2018, 57, 63–74. doi:10.1111/gwat.12841. [Google Scholar]

-