Systemic Sclerosis (SSc) is an autoimmune process that is characterized by widespread fibrosis. Variability in disease expression and severity is observed, ranging from limited organ involvement, including the skin and extremities, to a more diffuse pattern of organ involvement, including the lungs, GI tract, heart, and vasculature [

1,

2]. The underlying pathophysiology for the progression of SSc is complex and, although somewhat shrouded in mystery, may have important generalizability to a host of other fibrotic diseases, including aging. The development of fibrosis in many disease processes is a fundamental cause of morbidity and mortality in the aging population and, to no surprise, has gained widespread interest among basic translational researchers. It has been estimated that nearly 50% of deaths in Westernized countries can be attributed to fibrosis [

3]. Considering the important role that collagen elaboration plays in various disease processes affecting all organs, the development of novel therapies to interrupt this devastating process has significant implications. SSc-associated interstitial lung disease (SSc-ILD) may have a nuanced mechanism. It exhibits a variable clinical course and is associated with high mortality [

2]. Much of the variability seen in SSc patient lung involvement has been associated with race [

4]. For example, patients of Asian descent have an earlier onset and more severe manifestations of SSc-ILD compared with patients of Caucasian descent, with approximately 80% of Asian patients presenting with SSc-ILD, which was reported to have a rapidly progressing phenotype [

4]. SSc-ILD is thought to be the leading cause of death [

5]. Correctly diagnosing SSc-ILD is critical to better disease management. Not only is correlating the autoantibody profile important [

6], but recently, ultrasounds [

7] and high-resolution computed tomography [

8] have become valuable tools in diagnosing early SSc-ILD onset.

Advancing our understanding of the mechanisms that lead to collagen formation in fibroblasts isolated from patients with SSc may provide a valuable model for understanding a variety of other fibrotic diseases. SSc is considered an autoimmune disease, but it shares many similarities with other fibrotic disease states caused by increased collagen deposition and cellular senescence, including those affecting the cardiovascular, pulmonary, and renal systems.

1.1. NLRP3 Inflammasome in SSc

A central player in inflammation seen in pulmonary SSc fibroblasts is the NLRP3 inflammasome. Key studies have shown that disruption of NLRP3 inflammasome signaling via caspase-1 results in the amelioration of collagen deposition and myofibroblast differentiation [

9]. Inflammasome activation is part of the innate immune system’s defense against invaders and is a long-standing idea that has been shown to be an effective mechanism to protect against non-autologous antigens [

10]. There are even indications that certain pathogens exploit this pathway to gain an advantage against the body’s immune system, such as hepatitis B [

11]. However, the idea that the inflammasomes can be activated by internal stimuli (cellular stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, pharmaceuticals,

etc.) is a relatively novel idea that has become popular in the investigation of autoinflammatory conditions [

12,

13].

Broadly speaking, two aspects of inflammasome activation appear to be important regardless of disease: priming and triggering. The NLRP3 inflammasome does not typically sit ready, waiting for an inflammatory insult to become activated. There is priming, which increases NLRP3 and pro-inflammatory cytokine gene transcription through the NFκB pathway. Inflammaging, the low-grade and chronic inflammation associated with aging, may be enough for priming [

14]. This allows for activation by inflammatory stimuli such as ATP, toxins, ROS, DNA, unfolded proteins, crystals, or other cellular stressors [

15]. Priming is responsible for increasing expression via the NFκB pathways to prepare for the insult, which is followed by activation by cellular stressors, resulting in potassium efflux and activation of downstream inflammasome signaling [

16,

17].

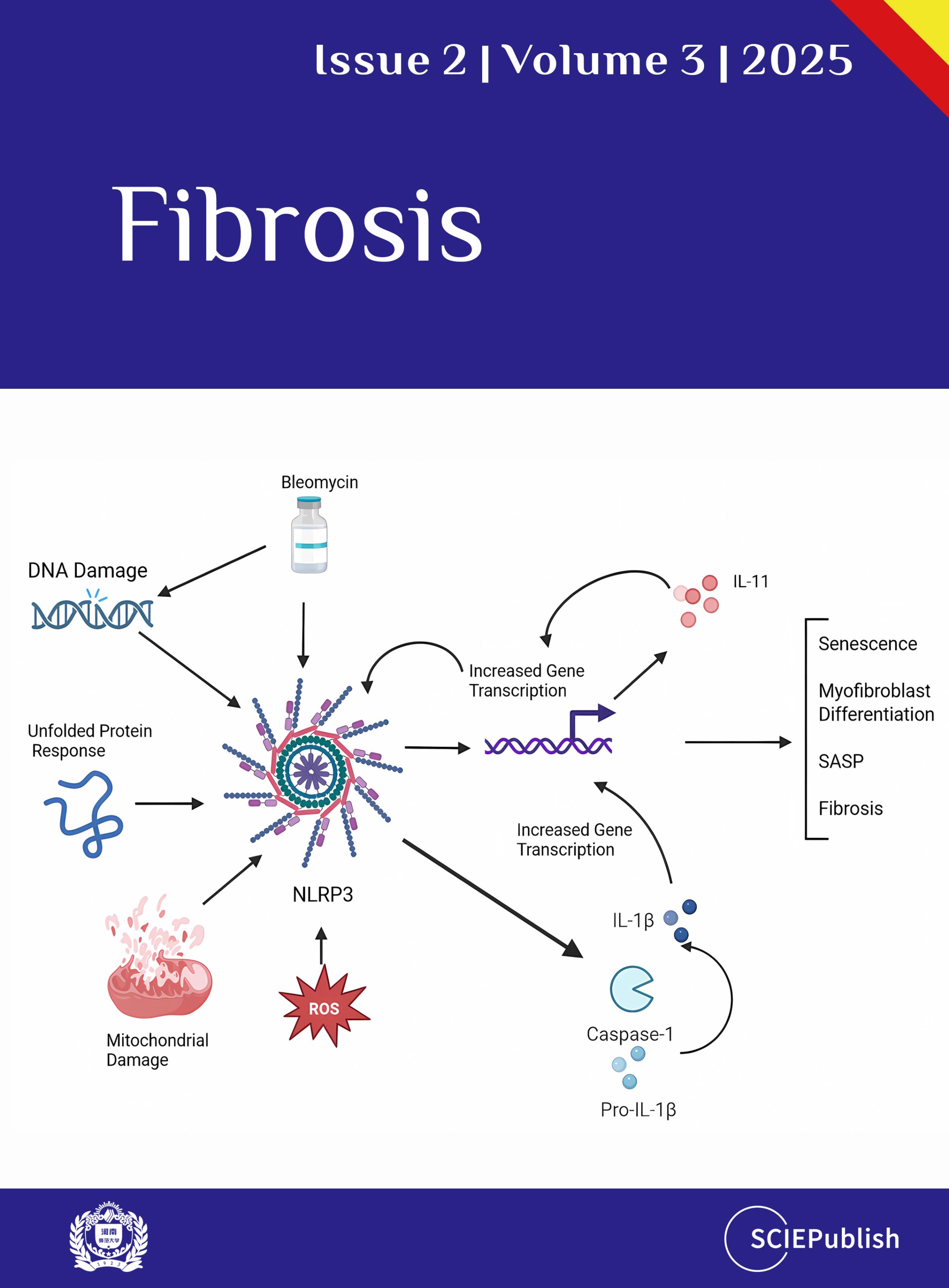

Activation of the inflammasome leads to the cleavage of procaspase-1 to its active form, caspase-1 (). Caspase-1 is one of the most well-studied human caspases and goes on to cleave several cytokines into their active forms, most notably IL-1β, IL-18, and IL-33, which are prime targets for activation via this pathway [

9,

18]. Caspase-1 is also able to cleave and activate itself as well as exert several downstream effects, including cleaving proteins involved in mitochondrial function, cytoskeleton rearrangement, and glycolytic pathways [

19,

20]. Cytokines activated by caspase-1 exert fibrotic responses such as collagen secretion, crosslinking, and myofibroblast transitions through transcriptional changes [

21]. Specifically, blockade of IL-1, IL-33, and IL-36 has been postulated as treatment targets for inflammasome activation [

22].

. The interplay between the NLRP3 inflammasome and IL-11 in SSc fibrosis. Numerous insults can activate the NLRP3 Inflammasome, which has a pathologic role in collagen deposition in SSc tissues. The maturation of caspase-1 leads to its downstream processing of IL-1β (and other cytokines), which increases the expression of IL-11. This, in turn, upregulates collagen deposition in the tissues and is involved in the differentiation of myofibroblasts, leading to SASP, senescence, and fibrosis. Created in BioRender. Artlett, C. (2025) https://BioRender.com/p83n03i (accessed on 4 April 2025).

Though caspase-1 is responsible for the bulk of downstream activity of the NLRP3 inflammasome, caspase-4 and -5 (and -11 in mice) are the remaining so-called “inflammatory” caspases that are involved in non-canonical signaling [

23,

24,

25]. To this end, the activity of these caspases is ancillary to that of caspase-1, but more work is needed to understand these non-canonical pathways. Interestingly, caspase-5 is expressed to a greater degree than other caspases, including caspase-1, in psoriatic skin lesions [

26]. However, no reports of increased caspase-4 or -5 in SSc exist.

Following activation of IL-1β and IL-18 in fibroblasts, there is a response leading to increased collagen deposition and myofibroblast transition [

17]. This is also accompanied by increases in the machinery that controls the export of collagen from the endoplasmic reticulum [

21]. This activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome leading to increased fibrosis is recapitulated in the in vitro studies on fibroblasts and in vivo mouse models using bleomycin. Collectively, bleomycin exerts diffuse fibrotic effects, which are dependent on the NLRP3 inflammasome [

9], and the fibrosis seen in SSc fibroblasts is dependent on the NLRP3 inflammasome [

9]. Downstream effects of the NLRP3 inflammasome leading to fibrosis are mediated by TGF-β1 [

27], which exerts vast fibrotic impacts that are relevant to the elaboration of pulmonary fibrosis, potentially via IL-11 signaling.

1.2. IL-11 in SSc

Though there are a host of cytokines that are upregulated in diseased SSc fibroblasts, IL-11 specifically has garnered much attention in recent years as a possible modulator of disease. Starting initially with studies in myocardial fibroblasts, Schafer et al. postulated that IL-11 is a mediator of fibrosis through its effect on TGF-β1 [

28]. Further studies by this group showed similar mechanisms in pulmonary and hepatic fibroblasts, further strengthening the hypothesis that IL-11 drives fibrosis [

29,

30]. However, other studies could not replicate this data and suggested that IL-11 effects limit fibrosis in tissues or have no effect at all [

31,

32,

33,

34]. These studies have been complicated by different effects between human and mouse antibodies, but the conclusions are hazy and suggest a more complicated mechanism [

35].

Though the end-points of fibrosis, such as increased collagen deposition, cannot be entirely attributed to IL-11, there is no dispute that its levels are elevated in SSc, with particularly elevated levels in SSc with pulmonary involvement [

36]. Although the mechanism underlying enhanced expression of IL-11 in SSc remains elusive, our lab has shown that it is dependent upon caspase-1 activation, which, in turn, is activated by the NLRP3 inflammasome [

34]. Inhibition of IL-1β, whose activation in SSc is also dependent on caspase-1 activation, does not demonstrate as great of an effect on IL-11 expression as inhibition of caspase-1 or of TGF-β1 [

34]. These data suggest the vital role that the NLRP3 inflammasome plays in the fibrotic process in the lungs of individuals with SSc, potentially via the IL-11 signaling cascade.

1.3. Senescence in SSc

An unanswered question posed by researchers and clinicians alike is how intrinsic functional abnormalities in tissue fibroblasts leads to extensive fibrosis. It has been hypothesized that an initial hit causes a domino effect of cellular abnormalities, as previously discussed. One attractive concept is that cellular senescence, typically associated with aging and cell cycle arrest, leads to a senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) [

2]. In a healthy system, SASP contributes to wound healing after a sudden insult, but in a diseased or aged system without a counterregulatory check, it can be unleashed and contribute to chronic inflammation [

37]. Senescent cells are characterized by upregulation of the transcription factor p16

INK4a or p53-p21, which causes cell cycle arrest, as well as β-galactosidase, monocyte chemotactic protein-1, plasminogen activator inhibitor 1, inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and pro-fibrotic cytokines such as TGF-β [

38]. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, which is a more aggressive fibrotic disease of the lung, is often studied in conjunction with SSc-ILD, and both show increased markers of senescence [

39]. In a comparison study, the expression of hundreds of genes associated with cellular senescence was upregulated in SSC-ILD and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis compared to controls [

40]. The authors show that aging and senescence markers are elevated in both diseases. In addition, dermal fibroblasts from SSc mirror the genetic upregulation of senescent-associated markers seen in the lungs [

40]. These dermal fibroblasts have increased oxidative stress and SASP profile that can be ameliorated with reactive oxygen species scavengers, suggesting that senescence is driven by oxidative stress [

41].

Age-related senescence in pulmonary fibroblasts leads to increased NLRP3 inflammasome expression, possibly through increased priming due to inflammaging. In bleomycin studies, aged mice are more likely to die than younger mice [

42]. These studies also showed elevated NLRP3 expression with bleomycin in aged mice, which increased the processing of IL-1β and IL-18 and downstream TGF-β mediated effects. Bleomycin injury in the lung also induces ROS, which exacerbates the fibrotic process seen in the lungs, and this likely occurs through the induction of cellular senescence. Inhibition of NLRP3 inflammasome through CY-09 ameliorates this effect and causes a reduction in markers of cellular senescence [

43].

Tying in another factor that contributes to cellular senescence is DNA damage. SSc has long been known to have damaged DNA, and cells feature telomere attrition [

44] and chromosomal rearrangements [

45]. More recently, studies have expanded on these earliest observations to show that this damage can be extensive [

46]. Damage to nuclear and mitochondrial DNA promotes the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome [

47,

48], and in turn, NLRP3 activity can promote DNA damage. Intriguingly, the Licondro group found that the deficiency in NLRP3 reduced the overall amount of damage to DNA in cells due to inflammation [

49]. Furthermore, the unfolded protein response and senescence are closely related; this feature promotes NLRP3 activation in the lung, leading to fibrosis [

50]. It is currently unknown whether these factors directly induce IL-11 expression or whether it is induced secondary to inflammasome activation.

Given the possible relationship between NLRP3 inflammasome and SASP, this begs the question of whether there is a relationship between IL-11 and cellular senescence. Like age-induced senescent cell markers (p16 and p21), IL-11 expression increases in all tissues with age [

51]. Further, the direct administration of IL-11 to fibroblasts increased p16 and p21 expression [

51]. Supporting this evidence, IL-11-KO mice had longer lifespans compared to controls, and through this work by Widjaja and others, they have postulated that IL-11 could be a regulator of senescence [

51,

52]. Recent work by Chen et al. investigated the effect of cellular senescence on TGF-β and IL-11 pathways using the Bmi-1-KO mouse model. Bmi-1 plays a role in cellular senescence by inhibiting p16 and maintaining redox balance, while the Bmi-1-KO mouse demonstrates stress-induced premature senescence. IL-11 was increased in Bmi-1-KO, and this was decreased with the reactive oxygen species scavenger NAC by inhibiting the expression of p16. In addition, the inhibition of IL-11 led to decreased p16 expression, suggesting IL-11 plays a role in managing cellular senescence, likely through upregulation of the MEK/ERK signaling cascade [

53].

These recent advances in fibrotic diseases and the study of SSc fibrosis have raised an interest in senolytics that specifically cause the death of senescent cells and in senomorphics, which interrupt the senescent signaling cascade. One such compound is dasatinib, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor, which, in conjunction with quercetin, demonstrated a reduction in senescent dermal fibroblasts in SSc [

54,

55]. However, to date, no studies have investigated the direct effects of senolytics on IL-11 expression. Further studies in senolytics have been performed in other fibrotic and age-related diseases that have an accumulation of senescent cells, with variable results and toxicity profiles [

17]. Senolytics are being identified using artificial intelligence screening of existing therapeutics and could open the door to novel treatment strategies in the future, particularly in SSc [

56].

Writing—Original Draft Preparation, C.M.M.; Writing—Review & Editing, C.M.M., C.M.A.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.