Emergent Superorganisms: Grass Rings Shaped by Individual Growth and Mortality

Received: 27 November 2025 Revised: 31 December 2025 Accepted: 19 January 2026 Published: 27 January 2026

© 2026 The authors. This is an open access article under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

1. Introduction

Nature abounds with regular patterns akin to the geometric codes of the natural world [1,2]. For instance, specific cloud formations serve as vital indicators for forecasting weather changes and guiding agricultural activities. Analogous phenomena are ubiquitously observed in plant aggregation structures (Figure 1), manifesting as regular vegetation patterns such as rings [3], spots [4], stripes [5,6], spirals [7,8], arcs [9], and labyrinthine structures [10,11].

Figure 1. Vegetation pattern in nature. (a) ring with a diameter of 15 cm; Stipa spp. (b) spot with a diameter of 60 cm; Oxytropis falcata Bunge (c) arc with a width of 2 m; Juniperus pingii var. wilsonii (d) labyrinthine; (e) Spiral with 10 cm; Stipa spp. All photos were taken in Tibet, China.

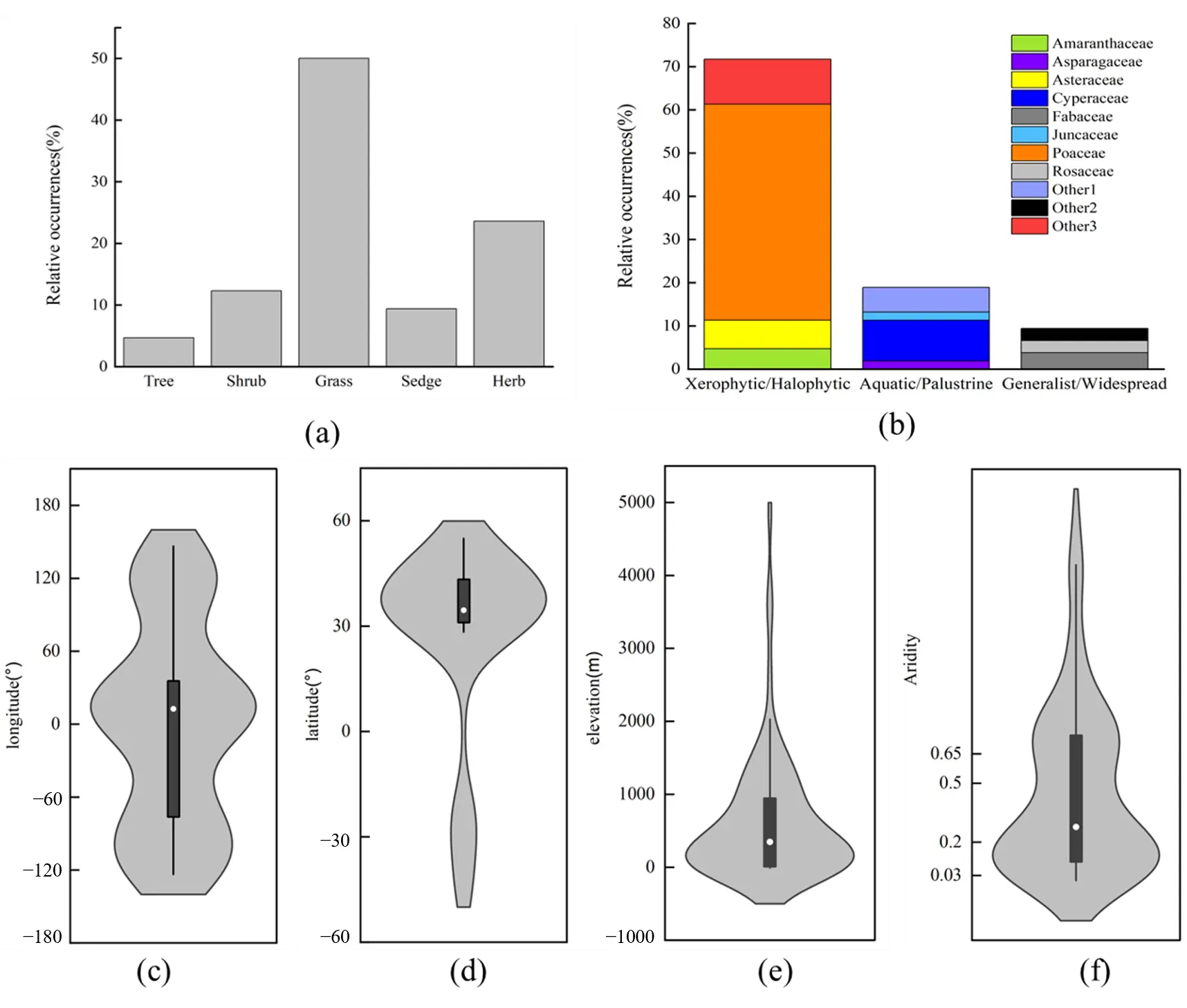

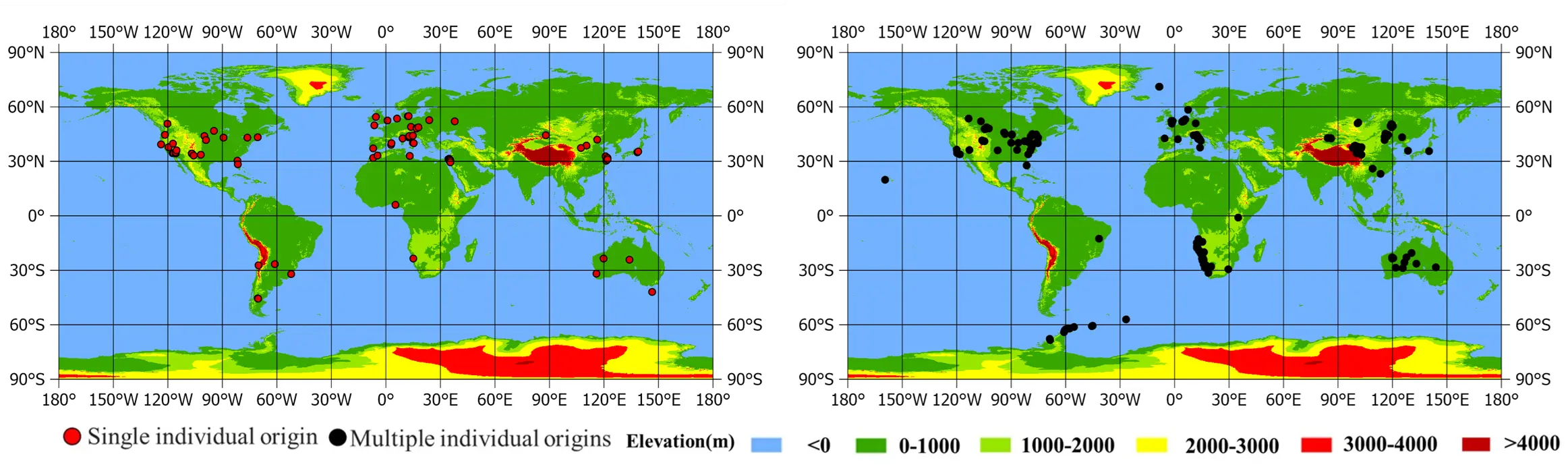

A grass ring, which is an arrangement of plants in an approximately circular form, represents a classic example of vegetation patterns [12]. Historically interpreted as supernatural artifacts, their perception has evolved into a subject of rigorous scientific inquiry, driven by their multiple roles as ecosystem engineers [13]. These rings critically influence plant populations by alleviating soil toxicity and ensuring reproduction, structure communities by creating microhabitats that enhance biodiversity, and serve as potential bio-indicators of ecosystem health [3,14]. The Grass ring, a phenomenon of persistent scientific interest, exhibits a global distribution (Figure 2a), spanning terrestrial, aquatic, and artificial ecosystems with grasslands as the predominant habitat (Figure 2b).

We define our subjects first to clarify scope and avoid confusion. It should be noted that, while relevant literature on fairy circles is consulted, our analysis does not target the circles themselves, but rather examines the ring-like structures found in the surrounding peripheral vegetation zones, defining them based solely on appearance and visual characteristics. It must be acknowledged that a view holds that the perennial vegetation belt is distinct from a true ring pattern, despite its visual resemblance [15]. Regarding the term “fairy circle”, please refer to the literature [15,16]. We are merely drawing upon relevant research to study the vegetation belts surrounding fairy circles. There is no intention to conflate the terminology of “fairy circle”. If we are to specify a particular type of ring, attention must be paid to its distinguishing features in soil moisture gradients, spatial scale, and distribution prevalence [15]. A clear recognition of both the shared morphology and these underlying differences is therefore essential to reduce ambiguity for researchers working on pattern formation in dryland ecosystems. While we first delineate the existing differences to avoid conflation, incorporating their shared visual ring morphology into our analysis is a valid approach.

Figure 2. Global distribution and habitat types of grass rings. (a) Global distribution map; (b) Proportional representation of different habitat types. Data were compiled from literature searches in the Web of Science and China National Knowledge Infrastructure databases. Location, Habitat, and original source information can be found in the Supplementary Material. The artificial ecosystem refers to habitats significantly influenced by human activities, such as managed grasslands, pastures, lawns, and so on.

However, a central question is how to reconcile the extensive documentation of grass ring formation with the emergence of visually similar patterns from divergent processes and origins. Previous investigations, while valuable for isolating specific mechanisms, have predominantly focused on regional cases or singular processes, and have struggled to explain the full range of formation pathways observed globally (Table 1).

Table 1. Overview of Publications on Major Grass Ring Formation Theories.

|

Major Theory |

References |

|---|---|

|

Natural senescence and architectural constraints |

Bonanomi et al., 2014 [3] |

|

Environmental stress and physical disturbance |

|

|

Nutrient and water depletion |

|

|

Species-specific negative plant-soil feedback |

|

|

Ecosystem engineering by termites |

Kappel et al., 2020 [17] |

|

Clonality hypothesis |

|

|

Vegetation self-organization hypothesis |

|

|

The morpho-phenological hypothesis |

Herooty et al., 2020 [18] |

|

The ecological hypothesis |

|

|

The aeolian hypothesis |

|

|

Ants and termite hypothesis |

Juergens, 2013 [19] |

|

Fungal hypothesis |

Zotti et al., 2025 [20] |

Note: Natural senescence and architectural constraints: plants grow radially, and their inner regions naturally die off due to the aging of the meristem. Environmental stress and physical disturbance: environmental abiotic stress may play an important role in the formation of rings. Nutrient and water depletion: the depletion of below-ground resources (nutrient and/or water) at the center of the clonal clump due to intraspecific and intra-clonal competition among densely aggregated ramets or, alternatively, by interspecific competition with other species rooted in the inner zone of the clone. Species-specific negative plant-soil feedback: Species-specific negative plant-soil feedback is defined as the rise of negative conditions for plant vegetative and reproductive performances of the same species induced in the soil by the plants themselves. Ecosystem engineering by termites: Ecosystem engineering by termites that remove plants from the center, facilitating localized underground water accumulation in the center. This moisture maintains the termites and the band of perennial grass on which termites feed year-round. Clonality hypothesis: the clonal mode of growth of individuals of many arid-land species that create vegetation rings. Vegetation self-organization hypothesis: the interplay between facilitation and competition. This sub-surface flow sustains the matrix and allows the peripheral grasses to grow large. The morpho-phenological hypothesis: A single parent individual produces ramets in a radial pattern to form a rondel patch, in which individuals in the center are older and thus die earlier. Outward rooting and a lack of regeneration buds in the center prevent plant development in the center, leaving it barren. The ecological hypothesis: The ecological hypothesis suggests that as a plant patch grows and becomes more densely vegetated, competition over water and nutrients among its constituent individuals increases. Individuals closer to the patch’s edge (the future perimeter) have better access to runoff flowing from the surrounding matrix, whereas those in the center can only access direct rainfall. Thus, the individuals at the patch’s edge outcompete those at the center, depriving them of water and causing their dieback. The aeolian hypothesis: The aeolian hypothesis proposes that in arid environments, plants trap fine wind-blown particles, creating a soil texture and hydraulic gradient between the patch center and edge. The gradient drives water and nutrient flow toward the edge, leading to resource depletion and plant mortality in the center, ultimately forming a vegetation ring. Ants and termite hypothesis: The water at the edge allows the formation of a ring of peripheral vegetation due to the impact of ants and termites. Fungal hypothesis: Fungi promote plant growth through mechanisms operating at physical, chemical, and biological levels.

As a step toward a more unified understanding, this review constructs a comprehensive database through systematic analysis of some publications. The database contains information on longitude, latitude, altitude, aridity, habitat, mechanisms, and genetic origin. We begin by providing a global overview of grass rings with two origins, then systematically examine the developmental processes of both formation pathways, and finally unify these observations under the superorganism concept. By transcending fragmented case studies, this review establishes a unified conceptual framework that analyzes grass ring formation through genetic origin and developmental processes, grounded in three core insights. First, grass rings can be classified based on the genetic origin of their constituent components into single and multiple individual origins. Second, the formation of grass rings fundamentally represents the development of a superorganism, exhibiting both individual life cycles and the formation and disintegration of ring structures. In the single individual origin, a mat-like clonal population formed through asexual reproduction undergoes central dieback due to biotic or abiotic factors, resulting in the formation of a superorganism, which continues to develop and eventually disintegrates. In the multiple individual origins, individual plants, stimulated by environmental gradients, locally form regularly arranged dominant populations, leading to superorganism formation. A third insight is that, while grass rings occur globally with distinct formation mechanisms across different habitats and developmental stages, the processes of ring formation at altitudes above 4000 m remain poorly understood.

2. Origins and Processes in Grass Ring Formation

Grass ring formation presents a persistent question: similar ring patterns can emerge from divergent ecological processes and contrasting origins [17]. Rings may originate from a single or multiple individuals. The ring formation process is governed by dynamic feedback between plant physiology and environmental heterogeneity. Crucially, the relative importance of these drivers can shift across a ring’s lifespan and vary with environmental context, clarifying why no single mechanism provides a universal explanation.

2.1. Ring Formation of a Single Individual Origin

Grass rings from a single individual origin observed across diverse ecosystems [21,22]. Morphological and genetic analyses confirm that constituent plants within such rings share clonal ancestry derived from a common origin, exhibiting uniformity in growth form and morphological traits [23,24,25]. Notably, this phenomenon is not limited to grasses but also occurs in shrubs and trees, and is particularly prevalent across multiple, highly adaptable plant families (Figure 3a,b). Geographically, these rings predominantly occur in mid-latitude zones (30°–60° N) and near the Tropic of Capricorn (30° S). Its distribution is restricted predominantly to semi-arid (0.2 ≤ AI < 0.5) and dry sub-humid (0.5 ≤ AI < 0.65) climates (Figure 3c–f). Ecologically, they thrive in varied habitats, including grasslands, deserts, forests, coastal areas, and artificial wetlands [3,26,27,28,29].

Figure 3. The overview of single individual origin rings. (a) Proportion of growth form of ring-forming plants; (b) Category of ring-forming plants; The environmental factors (longitude (c), latitude (d), elevation (e), climate (f)) distribution of single individual origin rings. Note: climate classification is based on the Aridity Index (AI) as follows [30]: Hyper Arid (AI < 0.03), Arid (0.03 ≤ AI < 0.2), Semi-Arid (0.2 ≤ AI < 0.5), Dry sub-humid (0.5 ≤ AI < 0.65), and Humid (AI ≥ 0.65). Detailed descriptions are provided in the Supplementary Material.

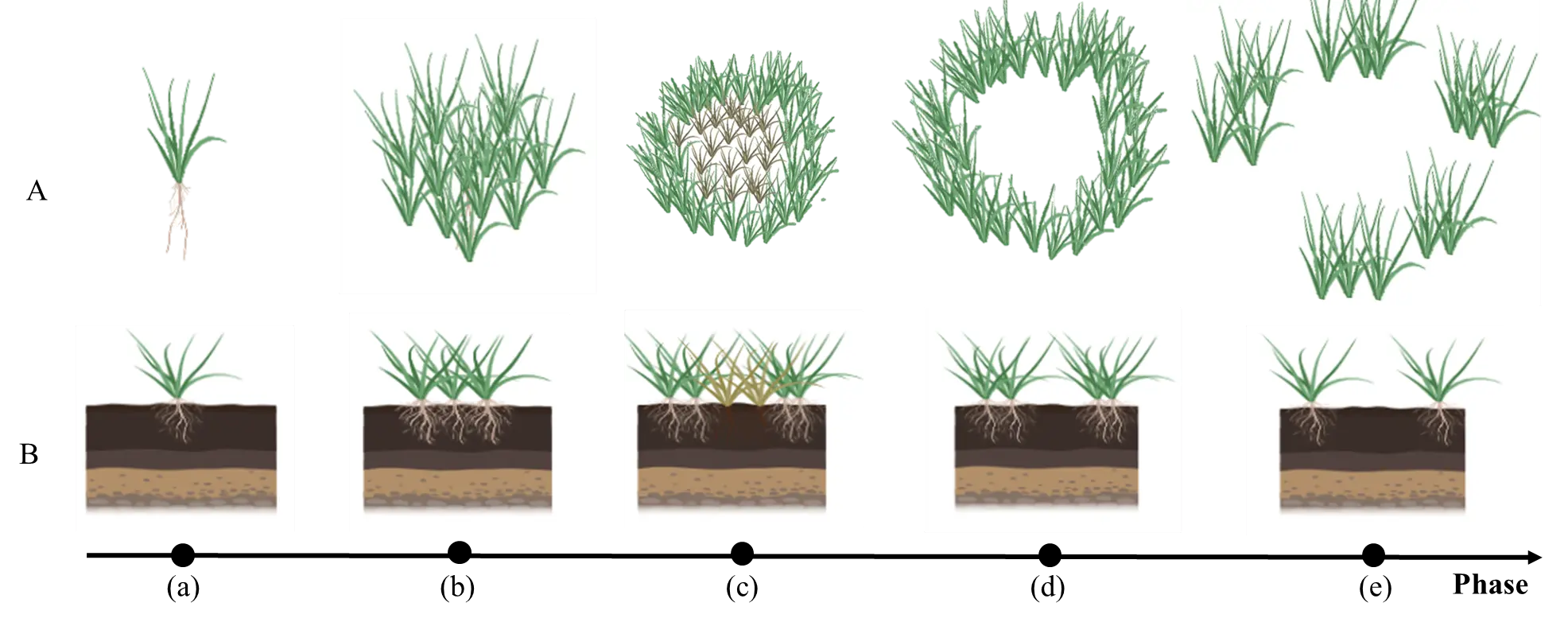

The formation of grass rings from a single individual origin represents a prototypical patch dynamics process, whose life cycle can be divided into several successive stages [31]. Based on long-term field observations and model simulations, this process typically encompasses five key phases: establishment, maturation, degradation, hollowing, and fragmentation [12,21,31,32]. During this process, a single genet expands to form a population of connected ramets through asexual reproduction, subsequently undergoing gradual central mortality, ultimately forming ring structures that further fracture with growth, completing the rise and fall cycle of the ring [31,32,33,34]. Accordingly, we focus on the following key processes (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Schematic diagram of the formation process of a single individual origin ring. (A) Top view; (B) Sectional view; (a) the clustered structure of a single genet; (b) a dense tussock; (c) The decline of above-ground parts in the tussock center; (d) a ring structure; (e) The ring structure fragments into multiple segments.

2.1.1. A Genet to Patch Phase

The development of ring patterns is not a singular event, but a sequential process. This “from-cluster-to-patch” process, driven by the lateral growth of single plants, is often reductively attributed to “clonal spread” in literature. Consequently, a critical gap exists, with the systemic investigation into the mechanisms and factors controlling this initial patch formation being largely absent. The following questions are fundamental to understanding the entire sequence, yet they remain conspicuously understudied.

A key question concerns the drivers of the initiation phase. Specifically, what factors dictate where a new patch is established? This is unlikely to be a stochastic process. To what degree is the location pre-programmed by inherited growth rules (e.g., spacer length) versus being a plastic response to fine-scale resource gradients? Furthermore, how do abiotic and biotic factors, such as soil texture and microbial communities, interact to determine the success or failure of a new patch?

Another question is whether these universal precursors are always destined to become rings. This leads to the pivotal unanswered question of whether a critical threshold exists that commits a patch to central dieback and ring formation. This threshold would be defined by factors such as patch size, ramet density, or internal resource stress, and once surpassed, it would preclude alternative fates, such as remaining static or dissipating.

In summary, the prevailing research paradigm skips this foundational stage (Figure 4a–b) and focuses on explaining the mature ring. However, it is the specific interplay of plant architecture, environmental drivers, and internal competition during this initial patch formation that sets the initial conditions for all subsequent dynamics. A causal explanation for this is that the foundation shift is therefore the key step in formulating a complete theory of ring pattern formation.

2.1.2. The Phase of Central Plant Biomass Recession

The recession of the central region represents a critical demographic shift that defines the transition from a solid vegetation patch to a distinct ring structure (Figure 4b–c). The interplay between plant traits and environmental drivers actively propels this phase, transforming what might seem like a passive die-off into a dynamic process [12]. While several hypotheses have been proposed to explain this central dieback, they are increasingly viewed as complementary mechanisms that may operate in concert, with their relative importance varying across species and environment [3].

- I

- Natural senescence and architectural constraints hypothesis

The branching and bud reservoir distribution of clonal plants naturally induce central hollowing during the growth phase [35,36]. For instance, central individuals gradually die off due to senescence, forming a ring-like structure [23,37,38]. However, current support for this hypothesis largely stems from correlative morphological observations, and experimental evidence establishing causality is still lacking [39]. The research gap lies in moving beyond descriptive morphology to validate the underlying function. Two key questions remain: first, how architectural constraints serve as the primary causal driver for the initiation of central recession, and second, to what extent the mortality of central ramets constitutes a deterministic program of senescence. Future research must employ manipulative experiments to elevate the hypothesis from a correlative inference into a validated mechanistic framework.

- II

- Nutrient and water depletion hypothesis

This hypothesis posits that intraspecific competition for limited soil resources initiates a feedback loop that drives central dieback [33,40]. This process is rooted in soil resource heterogeneity, which can shape spatial patterning at small scales [41]. The asymmetry in resource competition, where peripheral plants thrive on external resources while central ones face intense scarcity, initiates a self-reinforcing process of central recession and resource depletion [42,43]. Research attributes central dieback to two distinct mechanisms, the overland flow mechanism and the water uptake mechanism, both arising from asymmetric competition for water [44,45]. This effectively leads to a process of hydrological resource piracy; the desiccated central zone acts like a funnel unable to retain water effectively, while the structurally intact peripheral zone, with its dense root networks, functions like a sponge, actively drawing it in [18,40].

However, a limitation in validating this hypothesis lies in the reliance on static spatial comparisons of resources among the inner, ring, and outer zones. This snapshot approach can be misleading, as it primarily reveals the outcome of spatial disparity but fails to capture the dynamic processes driving ring formation and expansion. The question is whether the observed resource heterogeneity is the cause of central dieback or a consequence of ring shape. This causal ambiguity remains difficult to resolve with static studies or single stage study. Therefore, future research must move beyond static comparisons and prioritize continuous monitoring to elucidate how the spatial redistribution of resources couples in real-time with plant growth feedback. As field studies are often limited by long cycles and high costs, process-based mathematical models offer a key tool for simulating long-term feedback and overcoming these constraints. The preferred approach integrates modeling with field studies for mutual validation. Field methods such as space-for-time substitution, which uses plant morphology to represent different stages of ring development, can also help infer temporal dynamics. Combining tracer experiments with process-based math models will be crucial to definitively establish the role of resource depletion in grass ring dynamics.

- III

- Species-specific negative plant-soil feedback hypothesis

Ring formation is driven by self-inhibitory processes in which plants modify the soil environment through root exudates, pathogenic soil microbes, and litter decomposition, leading to central dieback [46,47,48,49]. Two primary mechanisms are the accumulation of phytotoxic allelochemicals that directly inhibit plant growth and the enrichment of host-specific soil pathogens that impair plant health [28,49,50,51,52,53,54]. This process of central degradation can be further accelerated in specific environments, such as carbonate-rich substrates, where factors such as sulfide toxicity may come into play [29,55,56,57].

However, research remains largely in a “black box” stage. Identification of the specific chemical substances or microbial taxa driving these feedbacks remains limited [58]. This process is likely governed by a complex network of interactions among multiple chemicals and microbial communities, rather than a single compound. Consequently, simply quantifying known substances is insufficient to reveal the underlying mechanisms fully.

Breaking through this bottleneck urgently requires integrating advanced technologies, such as omics and microbial metagenomics, to systematically characterize the chemical and biological information in soil. The central task for future research is to investigate how signaling molecules and pathogens regulate plant physiology to drive ring formation, thereby elucidating the ecological processes underlying negative feedback.

- IV

- Environmental stress and physical disturbance hypothesis

This hypothesis suggests that environmental stress, such as wind-blown sand, fire, or grazing, promotes ring formation by either directly destroying biomass or regulating resource availability [18,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66]. However, supporting evidence remains largely conceptual, relying primarily on correlations between disturbance regimes and ring presence rather than causal demonstrations from manipulative experiments [12]. Future research should employ controlled field experiments and quantitative modeling to dissect the relative contributions of these disturbances. Another question is how a fundamentally disturbance process can give rise to the highly regular spatial rings.

2.1.3. The Phase of Strengthening Grass Ring Integrity

During this phase (Figure 4c–d), the vegetation transitions from a diffuse ring-like formation retaining some central biomass to a stable ring structure. While factors such as fire are recognized to enhance ring integrity, the ecological processes that sustain ring integrity over time remain poorly studied [3,12]. For instance, the ring interior develops conditions such as low soil water content and biocrusts that inhibit grass recruitment [12]. Future research should focus on identifying the mechanisms that prevent the re-invasion of central areas and maintain ring distinctness, which represents a critical and understudied aspect of grass ring dynamics.

2.1.4. Grass Ring Disintegration Phase

The final stage of the grass ring life cycle (Figure 4d–e), transitioning from a mature ring to its eventual fragmentation, remains a poorly documented phase. It is hypothesized that the expansion of the central bare zone intensifies wind erosion, potentially restoring infiltration capacity through sediment loss, or that it triggers asymmetric growth from highly uneven resource distribution, ultimately causing the ring structure to rupture [12]. However, it is critical to note that this disintegration sequence is not a universally observed phenomenon. Its inclusion completes the conceptual model of ring dynamics, but whether this process necessarily occurs and under what conditions remains an open question.

2.2. The Ring Formation of Multiple Individual Origins

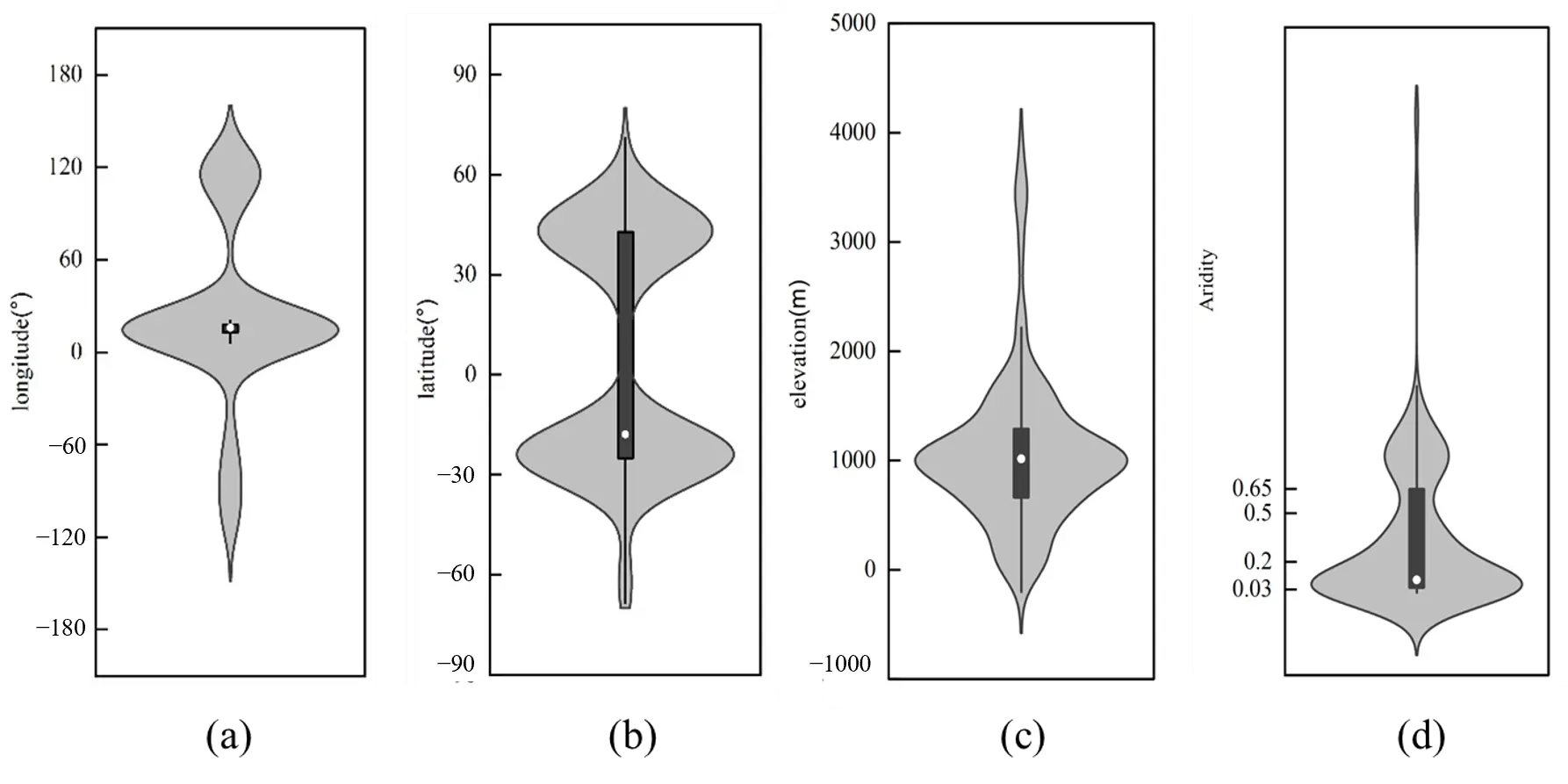

However, the single individual origin cannot fully explain the formation of all grass rings. Genetic evidence reveals that grass rings can originate from multiple founders, supporting a multiple formation mode [15,17,67]. The ring is predominantly confined to a semi-arid climate zone (0.2 ≤ AI < 0.5) (Figure 5). Their recorded habitats range from high-altitude alpine meadows to diverse environments, including Arctic and Antarctic islands, as well as lawns, farmlands, pastures, grasslands, deserts, and salt marshes [60,68,69,70,71,72].

Figure 5. Environmental factor distributions for rings of multiple individual origins. (a) longitude; (b) latitude; (c) elevation; (d) climate. Note: climate classification is based on the Aridity Index (AI) as follows: Hyper Arid (AI < 0.03), Arid (0.03 ≤ AI < 0.2), Semi-Arid (0.2 ≤ AI < 0.5), Dry sub-humid (0.5 ≤ AI < 0.65), and Humid (AI ≥ 0.65). Detailed descriptions are provided in the Supplementary Material.

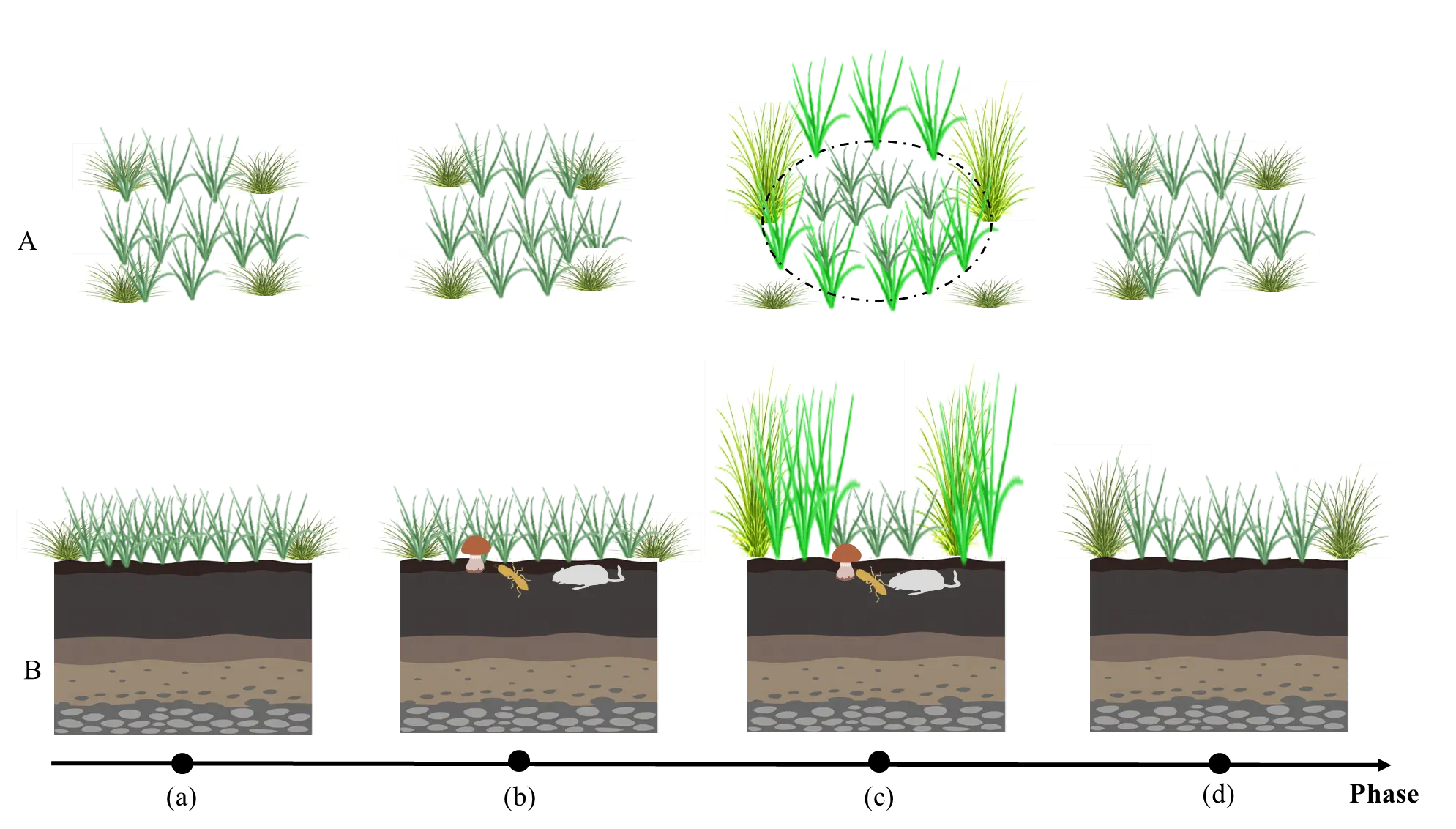

High-resolution satellite imagery and field observations have documented the complete life cycle of multiple individual origins grass rings, from initiation to disappearance [73]. Their formation is initiated by environmental heterogeneity induced by stimuli, in which peripheral plants exhibit distinct phenotypic responses, including enhanced biomass, height, and color [16,20]. This vigorous growth leads to the emergence of a ring structure. As the ring develops, it enters a state of dynamic feedback with its local environment, ultimately establishing a new stable equilibrium (Figure 6). These rings are not permanent and therefore follow a developmental sequence of establishment, formation, and disappearance phases [74,75,76].

Figure 6. Schematic Diagram of the formation process of multiple individual origins ring. (A) Top view; (B) Sectional view; (a) vegetation in initial state; (b) The state by some disturbance source (fungi, termites, or other animals); (c) Vigorous plant growth around the disturbance source, forming a ring; The dashed circle serves as a visual aid to define the region on the ring and is not a real feature. (d) New succession after the formation of the ring.

2.2.1. Establishment Phase

The establishment phase (Figure 6a–b) aims to elucidate the initial conditions and driving factors of ring formation. Current research suggests that the initial mechanism is the activation of resident fungi by favorable soil conditions or the introduction of new fungi via animal droppings [77,78]. It should be noted that these mechanisms remain speculative based on observations and lack direct experimental evidence. Other driving factors may exist but have not yet been discovered.

2.2.2. Formation Phase

This phase (Figure 6b–c) centers on resource redistribution that leads to the manifestation of ring patterns. The following sections review and evaluate three primary hypotheses, namely the fungal hypothesis, the faunal hypothesis, and the self-organization hypothesis.

- I

- Fungal hypothesis

This hypothesis posits that soil fungi drive this phenomenon through coordinated biological activities [79,80]. Driven by radial growth, fungal mycelia form an active peripheral ring [20]. This subterranean development process significantly alters local soil conditions, promoting the development of a visible ring of greener, taller vegetation on the surface [79]. Fungi promote plant growth within these rings through mechanisms that operate at the physical, chemical, and biological levels.

These interconnected mechanisms operate across multiple levels of the plant-soil system. Physically, the mycelial networks stabilize soil structure and create physical channels for root extension, thereby improving plant access to water and nutrients and shifting aboveground biomass accumulation [81,82]. Chemically, fungi regulate the soil environment by releasing growth-regulating compounds and mineralizing saprophytic nutrients. Specifically, they produce plant growth regulators, such as fairy chemicals 2-azahypoxanthine (AHX) and 2-aza-8-oxohypoxanthine (AOH), and the protein encoded by its gene LY9 enhances nitrogen assimilation, stress resistance, and hormonal modulation [83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93]. Additionally, multiple nitric oxide synthase (NOS) genes in fungi enable them to stimulate plant growth, likely through nitric oxide signaling [94]. Furthermore, the saprophytic release of essential nutrients, including nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium [95,96,97]. Biologically, fungi reconfigure the soil microbial community by enriching functional groups, such as nitrogen-fixing and phosphatase-solubilizing bacteria, thereby amplifying nutrient cycling processes [70,79,82,98,99,100]. Beyond these indirect nutrient-mediated pathways, specific symbiotic fungi can also directly induce morphological adaptations, such as stem elongation and leaf greening [101,102,103].

In summary, the fungal hypothesis interprets ring formation as emerging from plant-soil-fungi interaction networks [104]. This ring development results not from isolated factors but from the synergistic integration of multiple processes, including soil physical structure modification, chemical signaling, nutrient cycling, and microbial community restructuring [101]. This complex interaction network creates locally optimized growth niches above the active mycelial front, ultimately manifesting as unique circular spatial patterns [105]. However, two key aspects remain poorly understood and warrant future investigation. First, the mechanistic basis for the context-dependent effects of the same fungi on plants across different habitats remains unresolved. Second, while the broad developmental stages of rings are well-characterized, a deeper dissection of the specific ecological and molecular interactions governing each phase is needed to explain the emergent spatial dynamics fully.

- II

- Faunal hypothesis

The faunal hypothesis posits that ring is driven primarily by the ecosystem-engineering activities of social insects, particularly termites [19,106]. According to this concept, termite foraging and nesting engineer the soil environment by redistributing water or enriching soils with nutrients and hydrocarbons [107,108,109,110,111,112,113]. As a result of this water redistribution, a harvesting mechanism is created that facilitates lateral moisture movement to the periphery, thereby sustaining plant growth at the periphery of the ring [73,112]. Overall, these modifications create a competitive asymmetry that favors the growth of plants at the patch edge, resulting in the ring [73]. Indigenous knowledge identifies these patterns, and incorporating it provides a compelling line of evidence for this hypothesis [106].

Despite strong evidence, debates persist. Some studies question the primacy of termites, while others critique evidence for specific species [107,108,114]. The future of this hypothesis lies in rigorously testing these mechanisms through controlled field experiments that quantify the relative contributions of herbivory, hydrology, and microbial interactions.

- III

- Self-organization hypothesis

The self-organization hypothesis explains the perennial vegetation ring belt formation through ecological feedback mechanisms [16,115,116,117,118,119,120]. This theory states that when water becomes scarce, plant competition starts self-organizing processes [115]. Plant roots create local soil moisture gradients, which channel surface flow to further concentrate resources at the vegetation margins, thereby reinforcing the ring pattern [19,121]. The self-organization hypothesis is now tested by integrating mathematical models with field measurements from drone mapping, soil moisture sensors, and stable isotope tracing [122,123,124,125,126,127]. This synthesis has quantified how plant competition shapes landscapes, confirming the role of water redistribution and its dependence on rainfall levels in driving ring formation [128,129]. To advance the self-organization hypothesis, future research must integrate rigorous field studies to strengthen its empirical foundation and identify key feedback loops among other environmental factors besides water.

2.2.3. Disappearance Phase

The disappearance of these rings marks a transition toward ecosystem uniformity following the weakening of their maintaining forces (Figure 6c–d). Despite observations that have described fading patterns linked to fungal senescence or shrub death [13,130], the underlying mechanisms governing this phase remain poorly understood. Critical gaps exist in our understanding of when rings disappears and becomes permanent, the defining roles of climate and soil in this process, and the persistence of the ring induced effects on the environment.

2.3. From Origin to Process

In summary, the formation of two origin grass rings represents the coupling of distinct strategies with ecological processes. The proposed origin-process paradigm provides a clear framework for understanding the developmental dynamics of the ring (Figure 7).

The formation of a single individual origin ring follows a death-based mode. The core of this mode lies in an inside-out process of senescence, the ring develops from a central founder plant, meaning its initial clonal expansion defines the ring’s morphology. The subsequent dieback in the center during later developmental stages is an inevitable consequence of negative feedback mechanisms, such as intraspecific resource competition, allelopathy, or the accumulation of host-specific pathogens.

In contrast, the formation of multiple individual origins rings exemplifies a growth-based mode. The plants comprising the ring originate from different individuals, indicating that the ring pattern is not genetically predetermined but is an emergent response to a heterogeneous resource environment. Ecosystem engineers create a resource-enriched periphery. This heterogeneous environment subsequently attracts and facilitates the establishment and growth of various plants.

It is important to note that a key prospect for future research is to investigate whether these two modes are mutually exclusive or can operate synergistically across different spatial and temporal scales to shape ring morphology in more complex ecosystem scenarios collectively. Nevertheless, the origin-process paradigm successfully integrates diverse hypotheses into a coherent logical framework, profoundly revealing how the dynamic coupling of plant life activities and environmental factors drives the formation of the Grass Ring.

3. Toward a Superorganism View of Grass Rings

Analysis of grass ring formation pathways reveals that distinct origin modes, despite their mechanistic differences, converge on a similar phenotypic outcome. This commonality prompts a fundamental question of whether grass rings share a unified essential nature beneath their different formation pathways.

Existing evidence shows that both formation modes exhibit three key characteristics: coordinated growth rhythms among individuals, a complete life cycle at the system level, and effective resource sharing within the population [131,132]. These features indicate that grass rings are not mere plant assemblages but highly organized living systems [133,134]. Based on these findings, we propose that grass rings constitute a superorganism [135]. In a single individual origin, individuals reproduce asexually to form a mat-like clonal population. Subsequently, due to biotic or abiotic factors, the central part of the population gradually dies off, resulting in a ring-shaped structure. This marks the formation of the superorganism, which then continues to develop and eventually disintegrate. In the multiple individual origins ring, individual plants, stimulated by environmental gradients, locally form regularly arranged dominant populations, leading to ring formation and the formation of a superorganism. The single individual origin and death-based mode achieves ring formation through central dieback, while the multiple individual origins growth-based mode forms ring patterns through coordinated establishment of multiple individuals. These two pathways represent different developmental strategies for superorganism establishment, yet both create functional wholes with complete life cycles.

Understanding grass rings as superorganisms provides an integrative perspective for studying their formation mechanisms. This approach regards spatial patterns as external manifestations of systemic life processes, helping to transcend debates about specific formation mechanisms and grasp the biological essence of grass rings holistically.

4. The Need for High-Altitude Perspective

The environmental frameworks are primarily based on studies at lower and mid-elevations, and no case studies exist from extreme high-altitude habitats (above 4000 m). Consequently, whether the proposed universal mechanisms can fully explain ring formation under such a unique environment remains an open question. These high-altitude environments are characterized by low temperatures, seasonal and regional precipitation, intense solar radiation, strong winds, low oxygen content, and slow soil nutrient conversion rates. Although grass rings are documented here, their underlying formation mechanisms remain largely unexplored (Figure 8).

High-altitude habitats provide a unique perspective for investigating ring formation. The distinct selective pressures in these extreme environments may shape formation pathways different from those at lower altitudes, potentially even giving rise to yet unrecognized mechanisms. Consequently, high-altitude research should as a starting point for exploring the diversity of grass ring formation mechanisms and the role of environmental drivers. By systematically comparing formation processes across altitudinal gradients, we can elucidate the dynamic interplay between death-based and growth-based strategies in shaping ring, thereby advancing our understanding of grass ring formation.

Figure 8. The altitudinal gradient distribution map of grass rings under investigation for formation mechanisms.

5. Conclusions

This review establishes three propositions for grass ring research.

First, grass rings are classified into two origin types, corresponding specifically to death-based and growth-based formation modes, respectively. Single individual origin rings achieve ring construction through central dieback, while multiple individual origin rings form organized structures through coordinated responses to environmental signals. Both developmental pathways ultimately lead to the establishment of superorganisms.

Second, grass rings are superorganisms in essence. Evidence demonstrates that they represent biological entities with complete life cycles, coordinated resource allocation, and systematic developmental programs, characteristics that transcend mere spatial aggregation of plants.

Third, despite the global distribution of superorganisms, their formation mechanisms in high-altitude regions (above 4000 m) remain a knowledge gap. Extreme high-altitude environments serve as natural laboratories that may select for unique formation pathways or generate novel mechanisms.

Critical knowledge gaps and future research priorities include multi-scale quantitative studies of the superorganism’s life cycle and the formation mechanisms of grass rings in extreme high-altitude environments.

These findings reconsider the apparent growth-based and death-based strategies by unifying both strategies within the superorganism concept. To advance this field, we recommend establishing international monitoring networks that utilize national parks and research stations as natural laboratories and integrate citizen science programs with mechanistic modeling, drone-based monitoring, and multi-omics approaches.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be found at: https://www.sciepublish.com/article/pii/848, Table S1: Grass Ring Database. Supplementary Table S1 is the vegetation ring database, comprising the following sheets: Sheet 1 (Total database) contains core data fields including Reference, Ring type, Longitude, Latitude, Aridity Index, Climate zone, Elevation, Site, Habitat, Specific habitat, Proposed Mechanism, and Evidence Type. Sheet 2 lists Reference and Ring size (m). Sheets 3–8 provide the underlying source data for generating Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 5 and Figure 7.

Statement of the Use of Generative AI and AI-Assisted Technologies in the Writing Process

During the preparation of this manuscript, the author used DeepSeek in order to polish the language. After using this tool, the author reviewed and edited the content as needed and takes full responsibility for the content of the published article.

Acknowledgments

We thank for Junyao Sun for invaluable advice during the initial stages of this work.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.Y.; Methodology, X.Y. and J.J.; Investigation, J.J.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, J.J.; Writing—Review & Editing, X.Y., J.H., S.Y., R.Z. and L.Q.; Visualization, J.J.; Supervision, X.Y.

Ethics Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions are included in the article. All data are available in the supporting information.

Funding

This work was supported by the Second Tibetan Plateau Scientific Expedition and Research (STEP) program (2019QZKK0502).

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Rietkerk M, Van De Koppel J. Regular pattern formation in real ecosystems. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2008, 23, 169–175. DOI:10.1016/j.tree.2007.10.013 [Google Scholar]

- Meron E. From Patterns to Function in Living Systems: Dryland Ecosystems as a Case Study. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 2018, 9, 79–103. DOI:10.1146/annurev-conmatphys-033117-053959 [Google Scholar]

- Bonanomi G, Incerti G, Stinca A, Cartenì F, Giannino F, Mazzoleni S. Ring formation in clonal plants. Community Ecol. 2014, 15, 77–86. DOI:10.1556/ComEc.15.2014.1.8 [Google Scholar]

- Aguiar MR, Sala OE. Patch structure, dynamics and implications for the functioning of arid ecosystems. Trends Ecol. Evol. 1999, 14, 273–277. DOI:10.1016/S0169-5347(99)01612-2 [Google Scholar]

- Valentin C, d’Herbès JM, Poesen J. Soil and water components of banded vegetation patterns. CATENA 1999, 37, 1–24. DOI:10.1016/S0341-8162(99)00053-3 [Google Scholar]

- Hidalgo-Ogalde B, Pinto-Ramos D, Clerc MG, Tlidi M. Nonreciprocal feedback induces migrating oblique and horizontal banded vegetation patterns in hyperarid landscapes. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 14635. DOI:10.1038/s41598-024-63820-3 [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Oto C, Escaff D, Cisternas J. Spiral vegetation patterns in high-altitude wetlands. Ecol. Complex. 2019, 37, 38–46. DOI:10.1016/j.ecocom.2018.12.003 [Google Scholar]

- Pal MK, Poria S. Role of herbivory in shaping the dryland vegetation ecosystem: Linking spiral vegetation patterns and nonlinear, nonlocal grazing. Phys. Rev. E 2023, 107, 064403. DOI:10.1103/PhysRevE.107.064403 [Google Scholar]

- Tlidi M, Clerc MG, Escaff D, Couteron P, Messaoudi M, Khaffou M, et al. Observation and modelling of vegetation spirals and arcs in isotropic environmental conditions: Dissipative structures in arid landscapes. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2018, 376, 20180026. DOI:10.1098/rsta.2018.0026 [Google Scholar]

- Clerc MG, Echeverría-Alar S, Tlidi M. Localised labyrinthine patterns in ecosystems. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 18331. DOI:10.1038/s41598-021-97472-4 [Google Scholar]

- Echeverría-Alar S, Pinto-Ramos D, Tlidi M, Clerc MG. Effect of heterogeneous environmental conditions on labyrinthine vegetation patterns. Phys. Rev. E 2023, 107, 054219. DOI:10.1103/PhysRevE.107.054219 [Google Scholar]

- Ravi S, D’Odorico P, Wang L, Collins S. Form and function of grass ring patterns in arid grasslands: The role of abiotic controls. Oecologia 2008, 158, 545–555. DOI:10.1007/s00442-008-1164-1 [Google Scholar]

- Shantz H, Piemeisel R. Fungus fairy rings in Eastern Colorado and their effect on vegetation. J. Agric. Res. 1917, 11, 191–245. [Google Scholar]

- Hou L, Li L, Chen R, Wu Y, Feng G, Sun G-Q. Vegetation dynamics: Modeling, mechanisms, and emergent properties. Phys. Rep. 2025, 1145, 1–87. DOI:10.1016/j.physrep.2025.09.003 [Google Scholar]

- Getzin S, Yizhaq H, Tschinkel WR. Definition of “fairy circles” and how they differ from other common vegetation gaps and plant rings. J. Veg. Sci. 2021, 32, e13092. DOI:10.1111/jvs.13092 [Google Scholar]

- Cramer MD, Tschinkel WR. Fairy circle research: Status, controversies and the way forward. Perspect. Plant Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2025, 67, 125851. DOI:10.1016/j.ppees.2025.125851 [Google Scholar]

- Kappel C, Illing N, Huu CN, Barger NN, Cramer MD, Lenhard M, et al. Fairy circles in Namibia are assembled from genetically distinct grasses. Commun. Biol. 2020, 3, 698. DOI:10.1038/s42003-020-01431-0 [Google Scholar]

- Herooty Y, Bar P, Yizhaq H, Katz O. Soil hydraulic properties and water source-sink relations affect plant rings’ formation and sizes under arid conditions. Flora 2020, 270, 151664. DOI:10.1016/j.flora.2020.151664 [Google Scholar]

- Juergens N. The Biological Underpinnings of Namib Desert Fairy Circles. Science 2013, 339, 1618–1621. DOI:10.1126/science.1222999 [Google Scholar]

- Zotti M, Bonanomi G, Mazzoleni S. Fungal fairy rings: History, ecology, dynamics and engineering functions. IMA Fungus 2025, 16, e138320. DOI:10.3897/imafungus.16.138320 [Google Scholar]

- Watt AS. Pattern and Process in the Plant Community. J. Ecol. 1947, 35, 1. DOI:10.2307/2256497 [Google Scholar]

- Heslop-Harrison Y, Heslop-Harrison J. Ring Formation by Triglochin maritima in Eastern Irish Salt Marsh. Ir. Nat. J. 1958, 12, 223–229. [Google Scholar]

- Vasek FC. CREOSOTE BUSH: LONG-LIVED CLONES IN THE MOJAVE DESERT. Am. J. Bot. 1980, 67, 246–255. DOI:10.1002/j.1537-2197.1980.tb07648.x [Google Scholar]

- Lanta V, Doležal J, Šamata J. Vegetation patterns in a cut-away peatland in relation to abiotic and biotic factors: A case study from the Šumava Mts., Czech Republic. Suo 2004, 55, 33–43. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-Mendoza GA, Krämer K, Von Rönn GA, Schwarzer K, Heinrich C, Reimers H-C, et al. Circular structures on the seabed: Differentiating between natural and anthropogenic origins—Examples from the Southwestern Baltic Sea. Front. Earth Sci. 2023, 11, 1170787. DOI:10.3389/feart.2023.1170787 [Google Scholar]

- Douhovnikoff V, Cheng AM, Dodd RS. Incidence, size and spatial structure of clones in second-growth stands of coast redwood, Sequoia sempervirens (Cupressaceae). Am. J. Bot. 2004, 91, 1140–1146. DOI:10.3732/ajb.91.7.1140 [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Reynés D, Gomila D, Sintes T, Hernández-García E, Marbà N, Duarte CM. Fairy circle landscapes under the sea. Sci. Adv. 2017, 3, e1603262. DOI:10.1126/sciadv.1603262 [Google Scholar]

- Borum J, Raun AL, Hasler-Sheetal H, Pedersen MØ, Pedersen O, Holmer M. Eelgrass fairy rings: Sulfide as inhibiting agent. Mar. Biol. 2014, 161, 351–358. DOI:10.1007/s00227-013-2340-3 [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Reynés D, Mayol E, Sintes T, Hendriks IE, Hernández-García E, Duarte CM, et al. Self-organized sulfide-driven traveling pulses shape seagrass meadows. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2216024120. DOI:10.1073/pnas.2216024120 [Google Scholar]

- Zomer RJ, Xu J, Trabucco A. Version 3 of the Global Aridity Index and Potential Evapotranspiration Database. Sci. Data 2022, 9, 409. DOI:10.1038/s41597-022-01493-1 [Google Scholar]

- Gatsuk LE, Smirnova OV, Vorontzova LI, Zaugolnova LB, Zhukova LA. Age States of Plants of Various Growth Forms: A Review. J. Ecol. 1980, 68, 675. DOI:10.2307/2259429 [Google Scholar]

- Lewis JP, StofellaSL, Feldman SR. Monk’s tonsure-like gaps in the tussock grass Spartina argentinensis (Gramineae). Rev. Biol. Trop. 2001, 49, 313–316. [Google Scholar]

- Sheffer E, Yizhaq H, Gilad E, Shachak M, Meron E. Why do plants in resource-deprived environments form rings? Ecol. Complex. 2007, 4, 192–200. DOI:10.1016/j.ecocom.2007.06.008 [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi K, Yokoi Y. Spatiotemporal patterns of shoots within an isolated Miscanthus sinensis patch in the warm-temperate region of Japan. Ecol. Res. 2003, 18, 41–51. DOI:10.1046/j.1440-1703.2003.00538.x [Google Scholar]

- Wong S, Anand M, Bauch CT. Agent-based modelling of clonal plant propagation across space: Recapturing fairy rings, power laws and other phenomena. Ecol. Inform. 2011, 6, 127–135. DOI:10.1016/j.ecoinf.2010.11.004 [Google Scholar]

- Oborny B, Mony C, Herben T. From virtual plants to real communities: A review of modelling clonal growth. Ecol. Model. 2012, 234, 3–19. DOI:10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2012.03.010 [Google Scholar]

- Jansen HC. Hollow Crown in Semidesert Needle Grasses. Rangelands 1988, 10, 56–57. [Google Scholar]

- Warwick RM. Seagrass ‘fairy circles’ on the Isles of Scilly. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. United Kingd. 2022, 102, 63–68. DOI:10.1017/S0025315422000273 [Google Scholar]

- Zheng Z, Bai W, Zhang W. Clonality-dependent dynamic change of plant community in temperate grasslands under nitrogen enrichment. Oecologia 2019, 189, 255–266. DOI:10.1007/s00442-018-4317-x [Google Scholar]

- Yizhaq H, Al-Tawaha ARMS, Stavi I. A First Study of Urginea maritima Rings: A Case Study from Southern Jordan. Land 2022, 11, 285. DOI:10.3390/land11020285 [Google Scholar]

- Greig-Smith P. Pattern in Vegetation. J. Ecol. 1979, 67, 755. DOI:10.2307/2259213 [Google Scholar]

- Yizhaq H, Stavi I. Ring formation in Stipagrostis obtusa in the arid north-eastern Negev, Israel. Flora 2023, 306, 152353. DOI:10.1016/j.flora.2023.152353 [Google Scholar]

- Derner JD, Briske DD, Polley HW. Tiller organization within the tussock grass Schizachyrium scoparium: A field assessment of competition–cooperation tradeoffs. Botany 2012, 90, 669–677. DOI:10.1139/b2012-025 [Google Scholar]

- Sheffer E, Yizhaq H, Shachak M, Meron E. Mechanisms of vegetation-ring formation in water-limited systems. J. Theor. Biol. 2011, 273, 138–146. DOI:10.1016/j.jtbi.2010.12.028 [Google Scholar]

- Von Hardenberg J, Kletter AY, Yizhaq H, Nathan J, Meron E. Periodic versus scale-free patterns in dryland vegetation. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2010, 277, 1771–1776. DOI:10.1098/rspb.2009.2208 [Google Scholar]

- Abbas M, Giannino F, Iuorio A, Ahmad Z, Calabró F. PDE models for vegetation biomass and autotoxicity. Math. Comput. Simul. 2025, 228, 386–401. DOI:10.1016/j.matcom.2024.07.004 [Google Scholar]

- Cartenì F, Marasco A, Bonanomi G, Mazzoleni S, Rietkerk M, Giannino F. Negative plant soil feedback explaining ring formation in clonal plants. J. Theor. Biol. 2012, 313, 153–161. DOI:10.1016/j.jtbi.2012.08.008 [Google Scholar]

- Vincenot CE, Cartenì F, Bonanomi G, Mazzoleni S, Giannino F. Plant–soil negative feedback explains vegetation dynamics and patterns at multiple scales. Oikos 2017, 126, 1319–1328. DOI:10.1111/oik.04149 [Google Scholar]

- Ross ND, Moles AT. The contribution of pathogenic soil microbes to ring formation in an iconic Australian arid grass, Triodia basedowii (Poaceae). Aust. J. Bot. 2021, 69, 113–120. DOI:10.1071/BT20122 [Google Scholar]

- Marasco A, Iuorio A, Cartení F, Bonanomi G, Tartakovsky DM, Mazzoleni S, et al. Vegetation Pattern Formation Due to Interactions Between Water Availability and Toxicity in Plant–Soil Feedback. Bull. Math. Biol. 2014, 76, 2866–2883. DOI:10.1007/s11538-014-0036-6 [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-Spiegelberg P, Rietkerk M, Gomila D. How spatiotemporal dynamics can enhance ecosystem resilience. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2025, 122, e2412522122. DOI:10.1073/pnas.2412522122 [Google Scholar]

- Carlton L, Duncritts NC, Chung YA, Rudgers JA. Plant-microbe interactions as a cause of ring formation in Bouteloua gracilis. J. Arid Environ. 2018, 152, 1–5. DOI:10.1016/j.jaridenv.2018.02.001 [Google Scholar]

- Bonanomi G, Rietkerk M, Dekker SC, Mazzoleni S. Negative Plant–Soil Feedback and Positive Species Interaction in a Herbaceous Plant Community. Plant Ecol. 2005, 181, 269–278. DOI:10.1007/s11258-005-7221-5 [Google Scholar]

- Klipcan L, Kamennaya NA, Than Aye NT, Van-Oss-Pinhasi R, Meron E, Assouline S, et al. Microbial Factors May Contribute to the Persistence of Australian Fairy Circles. J. Biomed. Res. Environ. Sci. 2024, 5, 33–43. DOI:10.37871/jbres1869 [Google Scholar]

- Zhao L-X, Zhang K, Siteur K, Li X-Z, Liu Q-X, Van De Koppel J. Fairy circles reveal the resilience of self-organized salt marshes. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabe1100. DOI:10.1126/sciadv.abe1100 [Google Scholar]

- Mirlean N, Costa CSB. Geochemical factors promoting die-back gap formation in colonizing patches of Spartina densiflora in an irregularly flooded marsh. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2017, 189, 104–114. DOI:10.1016/j.ecss.2017.03.006 [Google Scholar]

- Wei X, Tian J, Zhao J. Fairy circles and temporal periodic patterns in the delayed plant-sulfide feedback model. Math. Biosci. Eng. 2024, 21, 6783–6806. DOI:10.3934/mbe.2024297 [Google Scholar]

- Wikberg S, Mucina L. Spatial variation in vegetation and abiotic factors related to the occurrence of a ring-forming sedge. J. Veg. Sci. 2002, 13, 677–684. DOI:10.1111/j.1654-1103.2002.tb02095.x [Google Scholar]

- Yizhaq H, Stavi I, Swet N, Zaady E, Katra I. Vegetation ring formation by water overland flow in water-limited environments: Field measurements and mathematical modelling. Ecohydrology 2019, 12, e2135. DOI:10.1002/eco.2135 [Google Scholar]

- Cremonini S, Trenti W, Pastorelli R, Fabiani A, Vianello G, Vittori Antisari L. Subaqueous soils and preliminary considerations on the occasional formation of “fairy circles” in the Comacchio saline (Province of Ferrara, Italy). EQA Int. J. Environ. Qual. 2024, 61, 62–70. DOI:10.6092/ISSN.2281-4485/19883 [Google Scholar]

- Strickland R. Hollow Crowns Overgrazing, Undergrazing, or Old Age. Rangel. Arch. 1983, 5, 13–14. [Google Scholar]

- Incerti G, Giordano D, Stinca A, Senatore M, Termolino P, Mazzoleni S, et al. Fire occurrence and tussock size modulate facilitation by Ampelodesmos mauritanicus. Acta Oecologica 2013, 49, 116–124. DOI:10.1016/j.actao.2013.03.012 [Google Scholar]

- Yizhaq H, Rein C, Saban L, Cohen N, Kroy K, Katra I. Aeolian Sand Sorting and Soil Moisture in Arid Namibian Fairy Circles. Land 2024, 13, 197. DOI:10.3390/land13020197 [Google Scholar]

- Cipriotti PA, Aguiar MR. Effects of grazing on patch structure in a semi-arid two-phase vegetation mosaic. J. Veg. Sci. 2005, 16, 57–66. DOI:10.1111/j.1654-1103.2005.tb02338.x [Google Scholar]

- Smit C, Buyens IPR, Le Roux PC. Vegetation patch dynamics in rangelands: How feedbacks between large herbivores, vegetation and soil fauna alter patches over space and through time. Appl. Veg. Sci. 2023, 26, e12747. DOI:10.1111/avsc.12747 [Google Scholar]

- Koffi KF, N’Dri AB, Lata J-C, Konaté S, Srikanthasamy T, Konan M, et al. Effect of fire regime on the grass community of the humid savanna of Lamto, Ivory Coast. J. Trop. Ecol. 2019, 35, 1–7. DOI:10.1017/S0266467418000391 [Google Scholar]

- Meyer JJM, Schutte CS, Galt N, Hurter JW, Meyer NL. The fairy circles (circular barren patches) of the Namib Desert—What do we know about their cause 50 years after their first description? South Afr. J. Bot. 2021, 140, 226–239. DOI:10.1016/j.sajb.2021.04.008 [Google Scholar]

- Fenton JHC. Concentric fungal rings in antarctic moss communities. Trans. Br. Mycol. Soc. 1983, 80, 415–420. DOI:10.1016/S0007-1536(83)80038-2 [Google Scholar]

- Rosa LH, De Sousa JRP, De Menezes GCA, Da Costa Coelho L, Carvalho-Silva M, Convey P, et al. Opportunistic fungi found in fairy rings are present on different moss species in the Antarctic Peninsula. Polar Biol. 2020, 43, 587–596. DOI:10.1007/s00300-020-02663-w [Google Scholar]

- Zotti M, De Filippis F, Cesarano G, Ercolini D, Tesei G, Allegrezza M, et al. One ring to rule them all: An ecosystem engineer fungus fosters plant and microbial diversity in a Mediterranean grassland. New Phytol. 2020, 227, 884–898. DOI:10.1111/nph.16583 [Google Scholar]

- Rosa LH, Da Costa Coelho L, Pinto OHB, Carvalho-Silva M, Convey P, Rosa CA, et al. Ecological succession of fungal and bacterial communities in Antarctic mosses affected by a fairy ring disease. Extremophiles 2021, 25, 471–481. DOI:10.1007/s00792-021-01240-1 [Google Scholar]

- Bonanomi G, Iacomino G, Di Costanzo L, Moreno M, Tesei G, Allegrezza M, et al. Mechanisms and impacts of Agaricus urinascens fairy rings on plant diversity and microbial communities in a montane Mediterranean grassland. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2025, 101, fiaf034. DOI:10.1093/femsec/fiaf034 [Google Scholar]

- Tarnita CE, Bonachela JA, Sheffer E, Guyton JA, Coverdale TC, Long RA, et al. A theoretical foundation for multi-scale regular vegetation patterns. Nature 2017, 541, 398–401. DOI:10.1038/nature20801 [Google Scholar]

- Tschinkel WR. The Life Cycle and Life Span of Namibian Fairy Circles. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e38056. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0038056 [Google Scholar]

- Salvatori N, Moreno M, Zotti M, Iuorio A, Cartenì F, Bonanomi G, et al. Process based modelling of plants–fungus interactions explains fairy ring types and dynamics. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 19918. DOI:10.1038/s41598-023-46006-1 [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Sinclair R. Namibian fairy circles and epithelial cells share emergent geometric order. Ecol. Complex. 2015, 22, 32–35. DOI:10.1016/j.ecocom.2015.02.001 [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert JH. Note on the Occurrence of “Fairy-Rings”. J. Linn. Soc. Lond. Bot. 1875, 15, 17–24. DOI:10.1111/j.1095-8339.1875.tb00208.x [Google Scholar]

- Salazar LM, Sebastià MT, Poch RM. Fungal Microfeatures in Topsoils Under Fairy Rings in Pyrenean Grasslands. Soil Syst. 2025, 9, 92. DOI:10.3390/soilsystems9030092 [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Guo L, Wilson GWT, Cobb AB, Wang K, Liu L, et al. Assessing soil microbes that drive fairy ring patterns in temperate semiarid grasslands. BMC Ecol. Evol. 2022, 22, 130. DOI:10.1186/s12862-022-02082-x [Google Scholar]

- Duan M, Lu M, Lu J, Yang W, Li B, Ma L, et al. Soil Chemical Properties, Metabolome, and Metabarcoding Give the New Insights into the Soil Transforming Process of Fairy Ring Fungi Leucocalocybe mongolica. J. Fungi 2022, 8, 680. DOI:10.3390/jof8070680 [Google Scholar]

- Caesar-TonThat TC, Espeland E, Caesar AJ, Sainju UM, Lartey RT, Gaskin JF. Effects of Agaricus lilaceps Fairy Rings on Soil Aggregation and Microbial Community Structure in Relation to Growth Stimulation of Western Wheatgrass (Pascopyrum smithii) in Eastern Montana Rangeland. Microb. Ecol. 2013, 66, 120–131. DOI:10.1007/s00248-013-0194-3 [Google Scholar]

- Cao M, Liu F, Sun L, Wang Y, Wan J, Wang R, et al. Floccularia luteovirens modulates the growth of alpine meadow plants and affects soil metabolite accumulation on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Plant Soil 2021, 459, 125–136. DOI:10.1007/s11104-020-04699-7 [Google Scholar]

- Liu S, Ye C, Guo J, Chen D, Liu J, Zhou X, et al. From fairy rings to fairy chemicals: The story from nature phenomenon to commercial application. Mod. Agric. 2024, 2, e24. DOI:10.1002/moda.24 [Google Scholar]

- Choi J, Fushimi K, Abe N, Tanaka H, Maeda S, Morita A, et al. Disclosure of the “Fairy” of Fairy-Ring-Forming Fungus Lepista sordida. ChemBioChem 2010, 11, 1373–1377. DOI:10.1002/cbic.201000112 [Google Scholar]

- Choi JH, Abe N, Tanaka H, Fushimi K, Nishina Y, Morita A, et al. Plant-Growth Regulator, Imidazole-4-Carboxamide, Produced by the Fairy Ring Forming Fungus Lepista sordida. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 58, 9956–9959. DOI:10.1021/jf101619a [Google Scholar]

- Choi J, Ohnishi T, Yamakawa Y, Takeda S, Sekiguchi S, Maruyama W, et al. The Source of “Fairy Rings”: 2-Azahypoxanthine and its Metabolite Found in a Novel Purine Metabolic Pathway in Plants. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 1552–1555. DOI:10.1002/anie.201308109 [Google Scholar]

- Kawagishi H. Fairy chemicals—A candidate for a new family of plant hormones and possibility of practical use in agriculture. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2018, 82, 752–758. DOI:10.1080/09168451.2018.1445523 [Google Scholar]

- Takemura H, Choi JH, Matsuzaki N, Taniguchi Y, Wu J, Hirai H, et al. A Fairy Chemical, Imidazole-4-carboxamide, Is Produced on a Novel Purine Metabolic Pathway in Rice. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 9899. DOI:10.1038/s41598-019-46312-7 [Google Scholar]

- Kawagishi H. Chemical studies on bioactive compounds related to higher fungi. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2021, 85, 1–7. DOI:10.1093/bbb/zbaa072 [Google Scholar]

- Duan M, Tao M, Wei F, Liu H, Han S, Feng J, et al. Leucocalocybe mongolica Fungus Enhances Rice Growth by Reshaping Root Metabolism, and Hormone-Associated Pathways. Rice 2025, 18, 52. DOI:10.1186/s12284-025-00813-4 [Google Scholar]

- Takemura H, Choi J-H, Fushimi K, Narikawa R, Wu J, Kondo M, et al. Role of hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyltransferase in the metabolism of fairy chemicals in rice. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2023, 21, 2556–2561. DOI:10.1039/D3OB00026E [Google Scholar]

- Graziosi S, Lombini A, Puliga F, Righini H, Dalla Pozza L, Zuffi V, et al. Analysis of Plant–Fungus Interactions in Calocybe gambosa Fairy Rings. Plants 2025, 14, 2884. DOI:10.3390/plants14182884 [Google Scholar]

- Duan M, Lu J, Yang W, Lu M, Wang J, Li S, et al. Metabarcoding and Metabolome Analyses Reveal Mechanisms of Leymus chinensis Growth Promotion by Fairy Ring of Leucocalocybe mongolica. J. Fungi 2022, 8, 944. DOI:10.3390/jof8090944 [Google Scholar]

- Takano T, Yamamoto N, Suzuki T, Dohra H, Choi J-H, Terashima Y, et al. Genome sequence analysis of the fairy ring-forming fungus Lepista sordida and gene candidates for interaction with plants. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 5888. DOI:10.1038/s41598-019-42231-9 [Google Scholar]

- Yang C, Zhang F, Liu N, Hu J, Zhang Y. Changes in soil bacterial communities in response to the fairy ring fungus Agaricus gennadii in the temperate steppes of China. Pedobiologia 2018, 69, 34–40. DOI:10.1016/j.pedobi.2018.05.002 [Google Scholar]

- Yang C, Li J, Liu N, Zhang Y. Effects of fairy ring fungi on plants and soil in the alpine and temperate grasslands of China. Plant Soil 2019, 441, 499–510. DOI:10.1007/s11104-019-04141-7 [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez A, Ibáñez M, Bol R, Brüggemann N, Lobo A, Jimenez JJ, et al. Fairy ring-induced soil potassium depletion gradients reshape microbial community composition in a montane grassland. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2022, 73, e13239. DOI:10.1111/ejss.13239 [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Wang C, Wei Y, Yao W, Lei Y, Sun Y. Soil Microbes Drive the Flourishing Growth of Plants From Leucocalocybe mongolica Fairy Ring. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 893370. DOI:10.3389/fmicb.2022.893370 [Google Scholar]

- Du J, He C, Wang F, Ling N, Jiang S. Habitat-specific changes of plant and soil microbial community composition in response to fairy ring fungus Agaricus xanthodermus on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Soil Ecol. Lett. 2024, 6, 230214. DOI:10.1007/s42832-023-0214-2 [Google Scholar]

- Marí T, Manjón-Cabeza J, Rodríguez A, San Emeterio L, Ibáñez M, Sebastià M-T. Changes in the Soil Bacterial Community Across Fairy Rings in Grasslands Using Environmental DNA Metabarcoding. Diversity 2025, 17, 322. DOI:10.3390/d17050322 [Google Scholar]

- Xu S, Dong K, Lee S, Ogwu MC, Undrakhbold S, Singh D, et al. Metagenetics of fairy rings reveals complex and variable soil fungal communities. Pedosphere 2023, 33, 567–578. DOI:10.1016/j.pedsph.2022.06.043 [Google Scholar]

- Marí T, Castaño C, Rodríguez A, Ibáñez M, Lobo A, Sebastià M-T. Fairy rings harbor distinct soil fungal communities and high fungal diversity in a montane grassland. Fungal Ecol. 2020, 47, 100962. DOI:10.1016/j.funeco.2020.100962 [Google Scholar]

- Zotti M, Bonanomi G, Mancinelli G, Barquero M, De Filippis F, Giannino F, et al. Riding the wave: Response of bacterial and fungal microbiota associated with the spread of the fairy ring fungus Calocybe gambosa. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2021, 163, 103963. DOI:10.1016/j.apsoil.2021.103963 [Google Scholar]

- Liu F, Liu P, Zhang Y, Sun L, Zhang P, Cao M, et al. Comparative metabolomics reveals that Agaricus bisporus fairy ring modulates the growth of alpine meadow plant on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 129, 107865. DOI:10.1016/j.ecolind.2021.107865 [Google Scholar]

- Liu M, Wei Y, Lian L, Zhang J, Liu N, Wilson GWT, et al. Discovering the role of fairy ring fungi in accelerating nitrogen cycling to promote plant productivity in grasslands. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2024, 199, 109595. DOI:10.1016/j.soilbio.2024.109595 [Google Scholar]

- Walsh F, Bidu GK, Bidu NK, Evans TA, Judson TM, Kendrick P, et al. First Peoples’ knowledge leads scientists to reveal ‘fairy circles’ and termite linyji are linked in Australia. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2023, 7, 610–622. DOI:10.1038/s41559-023-01994-1 [Google Scholar]

- Becker T, Getzin S. The fairy circles of Kaokoland (North-West Namibia) origin, distribution, and characteristics. Basic Appl. Ecol. 2000, 1, 149–159. DOI:10.1078/1439-1791-00021 [Google Scholar]

- Grube S. The fairy circles of Kaokoland (Northwest Namibia)—Is the harvester termite Hodotermes mossambicus the prime causal factor in circle formation? Basic Appl. Ecol. 2002, 3, 367–370. DOI:10.1078/1439-1791-00138 [Google Scholar]

- Picker MD, Ross-Gillespie V, Vlieghe K, Moll E. Ants and the enigmatic Namibian fairy circles—Cause and effect? Ecol. Entomol. 2012, 37, 33–42. DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2311.2011.01332.x [Google Scholar]

- Juergens N, Groengroeft A, Gunter F. Evolution at the arid extreme: The influence of climate on sand termite colonies and fairy circles of the Namib Desert. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2023, 378, 20220149. DOI:10.1098/rstb.2022.0149 [Google Scholar]

- Vlieghe K, Picker M, Ross-Gillespie V, Erni B. Herbivory by subterranean termite colonies and the development of fairy circles in SW Namibia. Ecol. Entomol. 2015, 40, 42–49. DOI:10.1111/een.12157 [Google Scholar]

- Jürgens N, Gunter F, Oldeland J, Groengroeft A, Henschel JR, Oncken I, et al. Largest on earth: Discovery of a new type of fairy circle in Angola supports a termite origin. Ecol. Entomol. 2021, 46, 777–789. DOI:10.1111/een.12996 [Google Scholar]

- Treonis AM, Bell LA, Marais E, Maggs-Kölling G. Namibian fairy circles: Hostile territory for soil nematodes. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0315884. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0315884 [Google Scholar]

- Getzin S, Yizhaq H. Desiccation of undamaged grasses in the topsoil causes Namibia’s fairy circles—Response to Jürgens & Gröngröft (2023). Perspect. Plant Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2024, 63, 125780. DOI:10.1016/j.ppees.2024.125780 [Google Scholar]

- Meron E. Vegetation pattern formation: The mechanisms behind the forms. Phys. Today 2019, 72, 30–36. DOI:10.1063/PT.3.4340 [Google Scholar]

- Getzin S, Erickson TE, Yizhaq H, Muñoz-Rojas M, Huth A, Wiegand K. Bridging ecology and physics: Australian fairy circles regenerate following model assumptions on ecohydrological feedbacks. J. Ecol. 2021, 109, 399–416. DOI:10.1111/1365-2745.13493 [Google Scholar]

- Getzin S, Yizhaq H, Bell B, Erickson TE, Postle AC, Katra I, et al. Discovery of fairy circles in Australia supports self-organization theory. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 3551–3556. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1522130113 [Google Scholar]

- Dong X. Fairy circle tales. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2314908120. DOI:10.1073/pnas.2314908120 [Google Scholar]

- Meron E. Pattern formation—A missing link in the study of ecosystem response to environmental changes. Math. Biosci. 2016, 271, 1–18. DOI:10.1016/j.mbs.2015.10.015 [Google Scholar]

- Getzin S, Holch S, Yizhaq H, Wiegand K. Plant water stress, not termite herbivory, causes Namibia’s fairy circles. Perspect. Plant Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2022, 57, 125698. DOI:10.1016/j.ppees.2022.125698 [Google Scholar]

- Cramer MD, Barger NN. Are Namibian “Fairy Circles” the Consequence of Self-Organizing Spatial Vegetation Patterning? PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e70876. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0070876 [Google Scholar]

- Fuentes MA, Cáceres MO. Fairy circles and their non-local stochastic instability. Eur. Phys. J. Spec. Top. 2017, 226, 443–453. DOI:10.1140/epjst/e2016-60178-1 [Google Scholar]

- Grabovsky VI. A Model of Vegetation Cover in Conditions of Resource Scarcity: Fairy Rings in Namibia. Biol. Bull. Rev. 2018, 8, 169–180. DOI:10.1134/S2079086418030064 [Google Scholar]

- Getzin S, Yizhaq H, Muñoz-Rojas M, Wiegand K, Erickson TE. A multi-scale study of Australian fairy circles using soil excavations and drone-based image analysis. Ecosphere 2019, 10, e02620. DOI:10.1002/ecs2.2620 [Google Scholar]

- Hill DJ. Existence of localized radial patterns in a model for dryland vegetation. IMA J. Appl. Math. 2022, 87, 315–353. DOI:10.1093/imamat/hxac007 [Google Scholar]

- Chen B, Teng S, Zheng G, Cui L, Li S, Staal A, et al. Inferring plant–plant interactions using remote sensing. J. Ecol. 2022, 110, 2268–2287. DOI:10.1111/1365-2745.13980 [Google Scholar]

- Bennett JJR, Bera BK, Ferré M, Yizhaq H, Getzin S, Meron E. Phenotypic plasticity: A missing element in the theory of vegetation pattern formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2311528120. DOI:10.1073/pnas.2311528120 [Google Scholar]

- Ravi S, Wang L, Kaseke KF, Buynevich IV, Marais E. Ecohydrological interactions within “fairy circles” in the Namib Desert: Revisiting the self-organization hypothesis. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 2017, 122, 405–414. DOI:10.1002/2016JG003604 [Google Scholar]

- Cramer MD, Barger NN, Tschinkel WR. Edaphic properties enable facilitative and competitive interactions resulting in fairy circle formation. Ecography 2017, 40, 1210–1220. DOI:10.1111/ecog.02461 [Google Scholar]

- Cipriotti PA, Aguiar MR. Biotic and abiotic changes along a cyclic succession driven by shrubs in semiarid steppes from Patagonia. Plant Soil 2017, 414, 295–308. DOI:10.1007/s11104-016-3131-7 [Google Scholar]

- Wilson DS, Sober E. Reviving the superorganism. J. Theor. Biol. 1989, 136, 337–356. DOI:10.1016/S0022-5193(89)80169-9 [Google Scholar]

- Detrain C, Deneubourg J. Self-organized structures in a superorganism: Do ants “behave” like molecules? Phys. Life Rev. 2006, 3, 162–187. DOI:10.1016/j.plrev.2006.07.001 [Google Scholar]

- Shoshitaishvili B. Is our planet doubly alive? Gaia, globalization, and the Anthropocene’s planetary superorganisms. Anthr. Rev. 2023, 10, 434–454. DOI:10.1177/20530196221087789 [Google Scholar]

- Oborny B. The plant body as a network of semi-autonomous agents: A review. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2019, 374, 20180371. DOI:10.1098/rstb.2018.0371 [Google Scholar]

- Huneman P. The Chicago school of ecology’s evolutionary superorganism and the clements-wright connection. Hist. Philos. Life Sci. 2025, 47, 12. DOI:10.1007/s40656-024-00652-4 [Google Scholar]