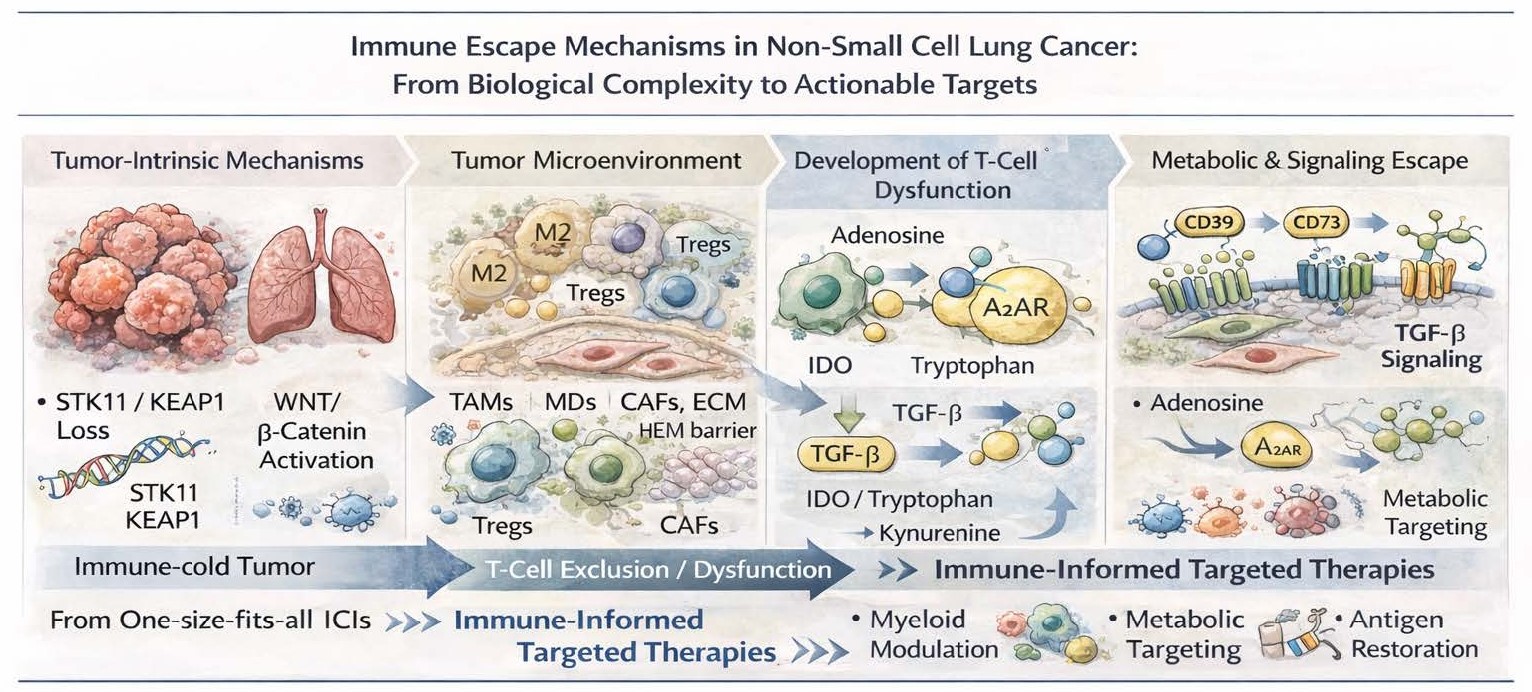

Immune Escape Mechanisms in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: From Biological Complexity to Actionable Targets

Received: 19 December 2025 Accepted: 24 December 2025 Published: 30 December 2025

© 2025 The authors. This is an open access article under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

1. Tumor-Intrinsic Drivers of Immune Escape

Somatic aberrations in tumor cells drive antitumor immunity. In particular, loss-of-function mutations in STK11/LKB1 and KEAP1 have come to be considered paradigmatic immune-cold drivers in NSCLC. Defective T-cell infiltration, dysfunction instead of activation of the interferon signaling, and resistance to PD-1 blockade despite the presence of PD-L1 expression has been documented after STK11 mutation associated with deficiency in other tumor types [1,2]. In a similar fashion, KEAP1 mutations drive metabolic remodeling and resistance to oxidative stress creating an immunosuppressive environment that also correlates with poor response to immunotherapy [3].

Another tumor-intrinsic immune exclusion mechanism that is represented by activation of the WNT/β-catenin pathway which promotes defective dendritic cell recruitment and impaired T-cell priming [4]. Simultaneously, changes in antigen presentation machinery such as HLA class I loss, β2-microglobulin mutations and interferon-γ signaling defects directly impair immune recognition, further facilitating immune evasion following therapeutic selection pressure [5].

Recent evidence has further refined this concept by demonstrating that immune escape in NSCLC is often subclonal rather than uniform. High-resolution analyses revealed that distinct tumor subclones may independently acquire immune-evasive features, resulting in spatially heterogeneous immune pressure and mixed clinical responses to ICIs [6]. These findings provide a biological explanation for early resistance and highlight the limitations of single-biopsy–based biomarkers.

These molecular characteristics not only emphasize the reason PD-L1 expression cannot fully characterize the immunological complexity in NSCLC but point to the necessity of integrating tumor genomics into ongoing therapeutic approaches targeting immunity.

2. The Tumor Microenvironment as an Active Driver of Resistance

Apart from mechanisms aimed at cancer cell–intrinsic escape, immune evasion in NSCLC is heavily influenced by the TME. Tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), especially the ones polarized toward an M2-like phenotype, inhibit cytotoxic T-cell activity by producing IL-10, TGF-β and arginase, and promote tumor angiogenesis and progression [7]. Similarly, regulatory T cells (Tregs) and myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) inhibit effector immune responses in actively way and are associated with resistance to ICIs [8].

Cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) also facilitate immune evasion by undergoing changes that remodel the extracellular matrix and lead to mechanical barriers to immune infiltration, as well as secreting immunosuppressive cytokines [9]. This leads to an overall spatial and functional heterogenity of the immune miocroenvironment that complicates the success of immune checkpoint blockade and mandate therapeutic strategies that directly address this stroma and myeloid components.

3. Metabolic and Signaling Pathways as Immune Targets

New emerging data demonstrates the role of metabolic immune escape mechanisms in NSCLC. Accumulation of adenosine in the TME due to CD39 and CD73 activity inhibits T-cell and natural killer cell activity through A2A receptor signaling and is viewed as a potential therapeutic target [10]. Dysregulated tryptophan metabolic pathway through indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) is associated to T-cell exhaustion and immune tolerance as well [11].

Importantly, the TGF-β pathway is at the juncture of immune suppression and tumor progression, contributing to T-cell exclusion, CAF activation and epithelial–mesenchymal transition. The clinical failures of unselected TGF-β inhibition highlight the need for biomarker-driven strategies that prioritize individuals most likely to respond to targeting this pathway [12].

4. Rethinking Targeted Therapy in the Immunotherapy Era

This limited success of combining ICIs with conventional targeted therapies in oncogene addicted NSCLC is one of the most critical problems, as most of the targeted agents were developed without contemplating the immunological implications of their use. Indeed, EGFR- and ALK-driven tumors, for example, show low levels of tumor mutational burden, defective antigen presentation, and immunosuppressive TMEs that likely explains their lack of responsiveness to immunotherapy [13,14].

Rather than pursuing unselected combinations, future strategies should focus on targeting immune escape mechanisms themselves. Insights from other immunotherapeutic platforms, including adoptive cell therapies, further emphasize the dominant role of the microenvironment in shaping resistance, with shared suppressive circuits involving myeloid cells, stromal barriers, and metabolic competition [15].

In this context, the concept of targeted therapy warrants redefinition. No longer confined to inhibition of oncogenic drivers, targeted therapy in the immunotherapy era should encompass interventions aimed at specific immune-evasive pathways that actively shape tumor–immune interactions.

Future strategies should instead aim to target mechanisms of immune escape themselves, rather than randomly chasing unselected combinations. Such therapies may involve myeloid cell modulation, tumor metabolic reprogramming, restoration of antigen presentation and converting immune-cold tumors to immune-inflamed tumors.

5. Toward Immune-Informed Targeted Therapies

Molecular mechanisms underpinning immune escape in NSCLC need a paradigm shift. We should really think about targeted therapy not simply as an inhibition of oncogenic drivers, but also as a re-adaptation of tumor–immune interactions. For the identification of opportunistic immune-evasive mechanisms and rational topping up strategies, molecular profiling merged with immune characterization will be relevant.

Eventually, the future of precision oncology in NSCLC will require targeting not only the tumor genome, but also the immune pathways that allow cancer and resistance to treatment to persist.

Ultimately, abandoning the one-size-fits-all immunotherapy paradigm in favor of immune-informed targeted approaches may represent the most critical step toward achieving durable clinical benefit in NSCLC.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.B.; Methodology, C.B.; Validation, M.C., L.B. and G.L.I.; Formal Analysis, C.B.; Investigation, C.B.; Resources, M.C.; Data Curation, C.B.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation C.B.; Writing—Review & Editing, C.B.; Visualization, J.G. and G.L.I.; Supervision, L.S.; Project Administration, C.B.

Ethics Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

-

Skoulidis F, Goldberg ME, Greenawalt DM, Hellmann MD, Awad MM, Gainor JF, et al. STK11/LKB1 Mutations and PD-1 Inhibitor Resistance in KRAS-Mutant Lung Adenocarcinoma. Cancer Discov. 2018, 8, 822–835. doi:10.1158/2159-8290.CD-18-0099. [Google Scholar]

-

Skoulidis F, Li BT, Dy GK, Price TJ, Falchook GS, Wolf J, et al. Sotorasib for Lung Cancers with KRAS p.G12C Mutation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 2371–2381. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2103695. [Google Scholar]

-

Arbour KC, Jordan E, Kim HR, Dienstag J, Yu HA, Sanchez-Vega F, et al. Effects of Co-occurring Genomic Alterations on Outcomes in Patients with KRAS-Mutant Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2018, 24, 334–340. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-1841. [Google Scholar]

-

Spranger S, Bao R, Gajewski TF. Melanoma-intrinsic β-catenin signalling prevents anti-tumour immunity. Nature 2015, 523, 231–235. doi:10.1038/nature14404. [Google Scholar]

-

Zaretsky JM, Garcia-Diaz A, Shin DS, Escuin-Ordinas H, Hugo W, Hu-Lieskovan S, et al. Mutations Associated with Acquired Resistance to PD-1 Blockade in Melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 819–829. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1604958. [Google Scholar]

-

Dijkstra KK, Vendramin R, Karagianni D, Witsen M, Gálvez-Cancino F, Hill MS, et al. Subclonal immune evasion in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Cell 2025, 43, 1833–1849.e10. doi:10.1016/j.ccell.2025.06.012. [Google Scholar]

-

Mantovani A, Marchesi F, Malesci A, Laghi L, Allavena P. Tumour-associated macrophages as treatment targets in oncology. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 14, 399–416. doi:10.1038/nrclinonc.2016.217. [Google Scholar]

-

Bronte V, Brandau S, Chen SH, Colombo MP, Frey AB, Greten TF, et al. Recommendations for myeloid-derived suppressor cell nomenclature and characterization standards. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 12150. doi:10.1038/ncomms12150. [Google Scholar]

-

Chen X, Song E. Turning foes to friends: Targeting cancer-associated fibroblasts. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2019, 18, 99–115. doi:10.1038/s41573-018-0004-1. [Google Scholar]

-

Allard B, Allard D, Buisseret L, Stagg J. The adenosine pathway in immuno-oncology. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 17, 611–629. doi:10.1038/s41571-020-0382-2. Erratum in Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 17, 650. doi:10.1038/s41571-020-0415-x. [Google Scholar]

-

Platten M, Nollen EAA, Röhrig UF, Fallarino F, Opitz CA. Tryptophan metabolism as a common therapeutic target in cancer, neurodegeneration and beyond. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2019, 18, 379–401. doi:10.1038/s41573-019-0016-5. [Google Scholar]

-

Mariathasan S, Turley SJ, Nickles D, Castiglioni A, Yuen K, Wang Y, et al. TGFβ attenuates tumour response to PD-L1 blockade by contributing to exclusion of T cells. Nature 2018, 554, 544–548. doi:10.1038/nature25501. [Google Scholar]

-

Gainor JF, Dardaei L, Yoda S, Friboulet L, Leshchiner I, Katayama R, et al. Molecular Mechanisms of Resistance to First- and Second-Generation ALK Inhibitors in ALK-Rearranged Lung Cancer. Cancer Discov. 2016, 6, 1118–1133. doi:10.1158/2159-8290.CD-16-0596. [Google Scholar]

-

Madeddu C, Donisi C, Liscia N, Lai E, Scartozzi M, Macciò A. EGFR-Mutated Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer and Resistance to Immunotherapy: Role of the Tumor Microenvironment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 6489. doi:10.3390/ijms23126489. [Google Scholar]

-

Lamplugh ZL, Wellhausen N, June CH, Fan Y. Microenvironmental regulation of solid tumour resistance to CAR T cell therapy. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2025, Oct 14., 1–19. doi:10.1038/s41577-025-01229-3. [Google Scholar]