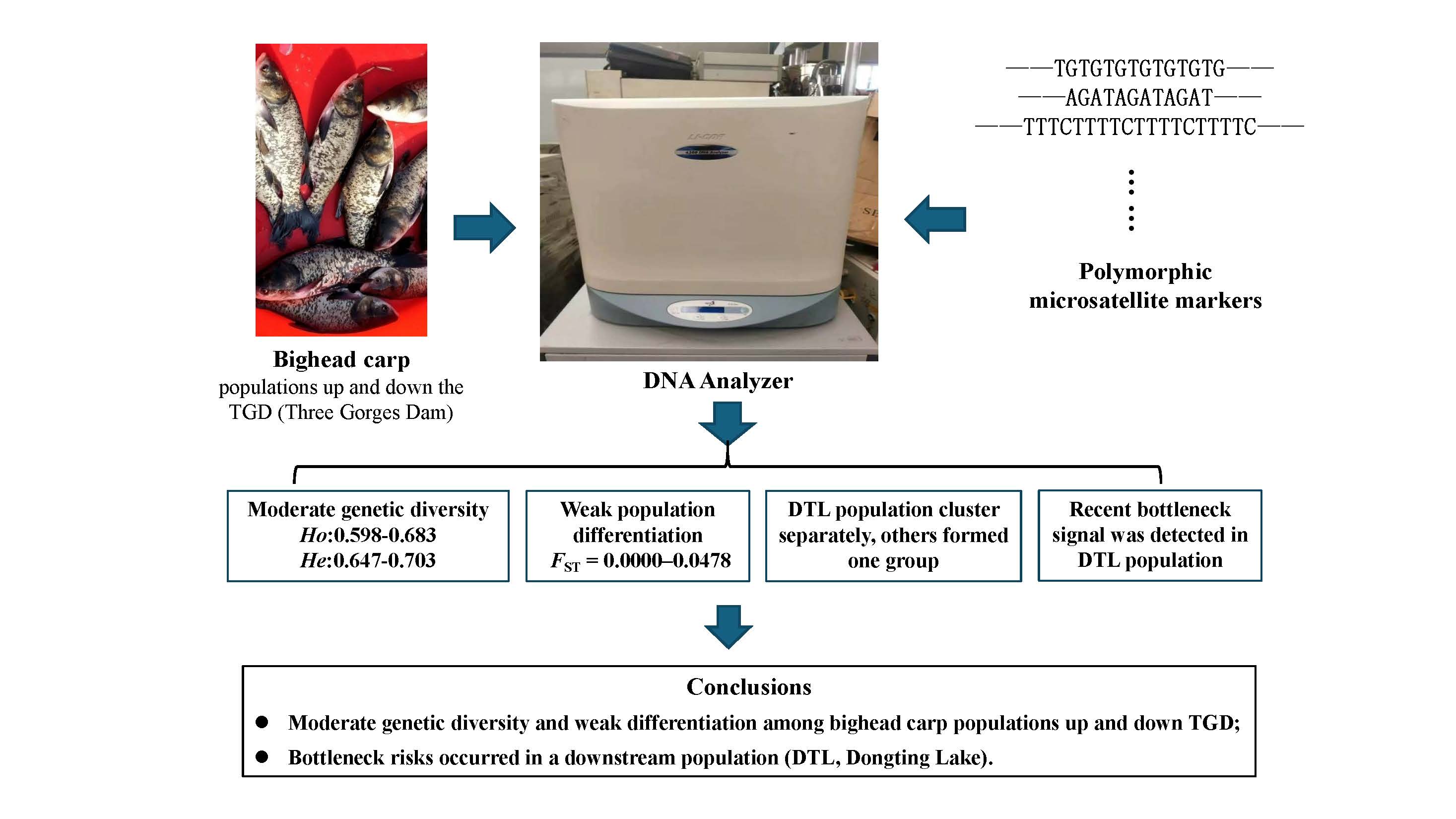

Genetic Diversity Among Populations of Bighead Carp (Hypophthalmichthys nobilis) Upstream and Midstream Yangtze River by Microsatellite DNA Analysis

Received: 30 September 2025 Revised: 28 November 2025 Accepted: 23 December 2025 Published: 30 December 2025

© 2025 The authors. This is an open access article under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

1. Introduction

Microsatellite DNA is a kind of simple sequence repeat (SSR), which consists of tandem DNA repeats of 1–6 base pairs [1], and microsatellites with tandem DNA repeats of 2–4 base pairs are widely applied to genetic analysis currently. Studies have shown that the polynucleotide repeated microsatellites have higher stability of amplification, and more faithfully reflect the genetic variation of DNA sequences compared to the dinucleotide repeated microsatellites [2,3]. Investigating and understanding the genetic status of a fish species is an indispensable step in conservation and scientific utilization of genetic resources. Molecular markers have proven useful for addressing questions about genetic diversity and population structure in fish species [4,5]. Among all molecular markers, microsatellites are the most informative and widely used in a variety of fish species in recent years, such as brown trout (Salmo trutta) [6], pike-perch (Sander lucioperca) [7], grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella) [8], Yellow River Carp (Cyprinus carpio haematopterus) [9], silver carp (Hypophthalmichthys molitrix) [10] and so on.

Bighead carp (Hypophthalmichthys nobilis) is one of the four major Chinese farmed carps and occupies an essential role in the freshwater fisheries of China. It is endemic and cultivated for more than a thousand years [11], and naturally distributed from the Pearl River (the south) to the Yellow River (the north) as well as the Yangtze River (the central) and other river systems of China [12]. The Yangtze River is the main production area of freshwater fisheries in China, and reports showed that the fry production of the four major Chinese farmed carps in the Yangtze River was superior to other water systems [13]. However, long-term overfishing, hydropower construction, and a series of man-made factors have led to dramatic changes in the Yangtze River water system in recent years, which caused a serious resource recession of the four major Chinese farmed carps, including bighead carp [14]. The Three Gorges Reservoir (TGR) on the Yangtze River is the world’s largest hydropower project. The Three Gorges Dam (TGD) that started operating in 2003 [15] located in the upstream Yangtze River, close to the boundary between its middle and upper sections. The effects of dams on riverine fish have been of great concern and broadly studied worldwide [16,17,18,19], and dams are considered one of the most negative anthropogenic activities on ecosystems. Some genetic analyses on bighead carp populations from the Yangtze River have been reported previously [20,21,22,23], which mainly concentrated in the midstream and downstream Yangtze River. Nevertheless, the status of germplasm resources for bighead carp in the upstream Yangtze River has been scarcely studied [24], especially after the TGD began operating.

In the present study, we used nine polymorphic microsatellites to analyze seven populations of bighead carp, of which five populations were from the upstream and two populations from the midstream of Yangtze River. The aims of this study were: (1) to obtain information about the genetic diversity of bighead carp in the upper and middle streams of the Yangtze River, China; (2) to estimate potential genetic differentiation of bighead carp populations up and down TGD.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Fish Samples and DNA Preparation

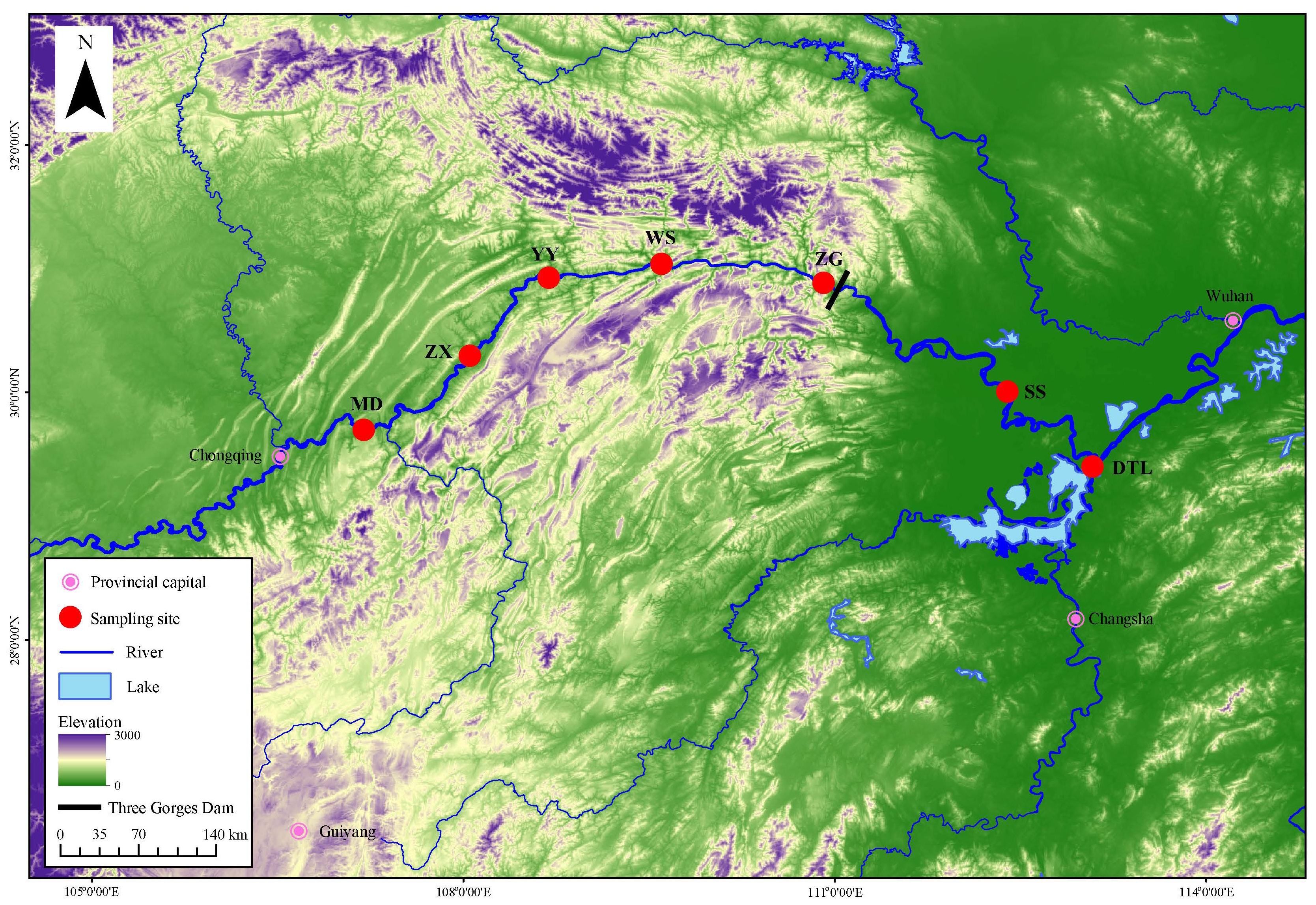

Fin clips of 295 bighead carp were collected from five wild populations in the upstream and two populations in the midstream of the Yangtze River from 2013 to 2014, including 25 for Mudong, Chongqing Province (MD); 43 for Zhongxian, Chongqing Province (ZX); 44 for Yunyang, Chongqing Province (YY); 48 for Wushan, Chongqing Province (WS) and 48 for Zigui, Hubei Province (ZG); 47 for Shishou, Hubei Province (SS) and 40 for Dongting Lake (DTL). The detailed sample information and locations of seven populations were shown in Table 1 and Figure 1. Total DNA was extracted from ethanol-preserved fin clips using a standard proteinase K/phenol-chloroform method [25]. The concentration and quantity of DNA were estimated by NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, DE, USA).

Figure 1. Distribution of sampling sites. MD stands for Mudong, ZX stands for Zhongxian, YY stands for Yunyang, WS stands for Wushan, ZG stands for Zigui, SS stands for Shishou, DTL stands for Dongting Lake.

Table 1. Information of bighead carp samples upstream and midstream Yangtze River used in this study.

|

Sampling Sites |

Sample Size |

Sampling Time |

|---|---|---|

|

Mudong (MD) |

25 |

2013 |

|

Zhongxian (ZX) |

43 |

2013 |

|

Yunyang (YY) |

44 |

2012–2013 |

|

Wushan (WS) |

48 |

2012–2013 |

|

Zigui (ZG) |

48 |

2013 |

|

Shishou (SS) |

47 |

2013 |

|

Dongting Lake (DTL) |

40 |

2013 |

2.2. Molecular Markers and Microsatellite Amplification

Nine pairs of the SSR primers (Table 2) with high polymerase chain reaction (PCR) success and polymorphism were selected in this study. According to the testing requirements of the LI-COR 4300 DNA analysis system, a 19 bp sequence (5′-CACGACGTTGTAAAACGAC-3′) should be added to the 5′ end of each forward primer when synthesizing SSR primers [26]. Hence, the forward primer can combine with not only the target fragment, but also the IR-M13F primer [M13 Forward (-29) IRDye 700 Primer or M13 Forward (-29) IRDye 800 Primer] (LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE, USA) when used in PCR amplification. PCR products were genotyped by LI-COR 4300 DNA analyzer.

PCR amplification was conducted in a volume of 12.5 µL reaction mixture, which consists of the following components: 30–50 ng of template DNA, 0.4 U of Taq DNA polymerase, 1.25 µL of 10× PCR buffer, 0.4 µL of dNTP (2.5 mmol/L), 0.4 µL of forward and reverse primer mixture (2.5 µmol/L), 0.3 µL of IR-M13F primers, and sterile water to the final volume. PCR amplification conditions were as follows: 94 °C for 5 min, followed by 25 cycles of 94 °C for 35 s, 48–60 °C for 35 s (annealing temperatures are shown in Table 2), 72 °C for 40 s and post-cycling extension at 72 °C for 10 min.

Table 2. Information of microsatellite markers used in this study.

|

Locus |

Accession No. |

Repeat Motif |

Primer Sequence |

Ta (°C) |

Size Range (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

HysdE1502-1 |

KC191534 |

(TG)26 |

F: CGAGGAAAGCAAAGAAAGTC |

56 |

166–187 |

|

R: ATAAAGATGGCAGCGATAGAG |

|||||

|

Hysd849-1 |

KC191547 |

(TTA)10 |

F: GTCTTCGGTGTCACATGATC |

54 |

235–259 |

|

R: ATCCAAAGTGACTAAGTAA |

|||||

|

Hysd280-1 |

KC191443 |

(TCT)13 |

F: GCTGATATGTTTGGGGAGT |

61 |

205–317 |

|

R: AGGGTGAAATGAGTATTGAC |

|||||

|

Hysd18-1 |

JN657291 |

(ATCC)7 |

F: TCTCCAGGTCACAGAGTCGC |

55 |

208–216 |

|

R: GCAAGAAGGTCCAGACACTCC |

|||||

|

Hysd209-2 |

JX499889 |

(AGAT)10 |

F: GTCTGAGGAAACATGGGCTACT |

59 |

212–323 |

|

R: AAAAAGGCTATTTCGGGGG |

|||||

|

Hysd666-1 |

KC191406 |

(TTTCT)17 |

F: TAGATGAGCCAGTGAAGTGC |

50 |

304–369 |

|

R: TCAAGTTGTTCCAAACCTGT |

|||||

|

Hysd293-1 |

JX499400 |

(AAGAG)14 |

F: AACGAACTCATTTCCAGACCAG |

57 |

124–244 |

|

R: CCAACATACATAAAGTACATCCC |

|||||

|

Hysd792-1 |

KC160529 |

(GAAGA)15 |

F: ATAACTGAATCATTCCATCGCC |

50 |

84–164 |

|

R: AGCCTAACCTGCCCTTTACTTG |

|||||

|

Hysd1148-1 |

JX499496 |

(AAATA)8 |

F: GTTCATTTGGTGGACTATTC |

50 |

138–263 |

|

R: TGGCTTTCATCACTATTTAT |

2.3. Data Statistics

The number of alleles (Na), observed heterozygosity (Ho) and expected heterozygosity (He) were estimated using a PopGene software package (version 1.32) [27]. The polymorphism information content (PIC) was implemented by an excel-based software [28] (microsatellite toolkit). Genetic divergence between populations was quantified by calculating pairwise Fst values using Arlequin 3.0 [29], and the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) tests for each locus in each population were also implemented by Arlequin. In addition, a molecular variation analysis (AMOVA) [30] was performed to estimate the distribution of genetic variations within and among populations and regions (upstream vs. midstream). A neighbor joining (NJ) tree was constructed based on Nei’s standard genetic distance. Population genetic structure was inferred using STRUCTURE v2.3.4 [31], applying a model-based clustering algorithm with Bayesian (MCMC sampling) estimation on multilocus genotype data [32]. The analysis of mutation-drift equilibrium was performed by Sign test using Bottleneck 3.4 [33], under three models including infinite allele model (IAM), two phase model (TPM) and the stepwise mutation model (SMM). The excess or deficiency of heterozygosity was analyzed to predict the dynamic variations of each population for a recent time.

3. Results

3.1. Genetic Diversity within Populations

The genetic parameters of 295 bighead carp individuals evaluated by nine microsatellites were summarized in Table 3. A total of 101 alleles (Na), ranging from 4 (Hysd849-1 and Hysd18-1) to 26 (Hysd293-1), with an average number of alleles per locus of 11.2, were detected in the seven populations. The mean expected heterozygosity (He) and observed heterozygosity (Ho) were 0.691 and 0.651, ranging from 0.463 to 0.934 and 0.443 to 0.903, respectively. And the polymorphism information content (PIC) values were 0.368–0.929 (mean 0.635).

Table 3. Polymorphic information of microsatellites in seven bighead carp populations.

|

Locus |

Na |

Ho |

He |

PIC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

HysdE1502-1 |

10 |

0.564 |

0.593 |

0.575 |

|

Hysd849-1 |

4 |

0.443 |

0.463 |

0.368 |

|

Hysd280-1 |

11 |

0.660 |

0.741 |

0.701 |

|

Hysd18-1 |

4 |

0.534 |

0.474 |

0.371 |

|

Hysd209-2 |

12 |

0.822 |

0.845 |

0.826 |

|

Hysd666-1 |

9 |

0.647 |

0.672 |

0.645 |

|

Hysd293-1 |

26 |

0.903 |

0.934 |

0.929 |

|

Hysd792-1 |

14 |

0.832 |

0.877 |

0.863 |

|

Hysd1148-1 |

11 |

0.452 |

0.522 |

0.440 |

|

Average |

11.2 |

0.651 |

0.691 |

0.635 |

As shown in Table 4, the mean Na per locus ranged from 5.3 (DTL) to 8.4 (ZG) among seven tested populations. The average He, Ho and PIC values for each population were 0.647 (DTL)–0.703 (MD), 0.598 (DTL)–0.683 (SS) and 0.591 (DTL)–0.639 (MD), respectively. One to four specific alleles were detected in each population, including one in WS and ZG, two in ZX, three in SS and DTL, and four in MD and YY.

Significant deviations (p < 0.05) from HWE were detected only at loci Hysd666-1 and Hysd1148-1 in the DTL population after Bonferroni corrections (Table 4).

Table 4. Polymorphic information of seven bighead carp populations at 9 microsatellites.

|

Parameter |

HysdE 1502-1 |

Hysd 849-1 |

Hysd 280-1 |

Hysd 18-1 |

Hysd 209-2 |

Hysd 666-1 |

Hysd 293-1 |

Hysd 792-1 |

Hysd 1148-1 |

Average |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

MD |

Na |

6 |

3 |

7 |

3 |

9 |

7 |

16 |

11 |

4 |

7.3 |

|

He |

0.573 |

0.475 |

0.740 |

0.542 |

0.869 |

0.771 |

0.927 |

0.880 |

0.551 |

0.703 |

|

|

Ho |

0.542 |

0.591 |

0.750 |

0.500 |

0.913 |

0.500 |

0.870 |

0.792 |

0.542 |

0.667 |

|

|

PIC |

0.522 |

0.375 |

0.681 |

0.441 |

0.832 |

0.723 |

0.899 |

0.847 |

0.433 |

0.639 |

|

|

ZX |

Na |

8 |

3 |

5 |

2 |

9 |

8 |

20 |

10 |

5 |

7.8 |

|

He |

0.548 |

0.492 |

0.698 |

0.452 |

0.816 |

0.709 |

0.941 |

0.831 |

0.512 |

0.667 |

|

|

Ho |

0.535 |

0.452 |

0.651 |

0.535 |

0.714 |

0.767 |

0.930 |

0.907 |

0.488 |

0.665 |

|

|

PIC |

0.524 |

0.379 |

0.649 |

0.347 |

0.786 |

0.674 |

0.926 |

0.800 |

0.419 |

0.612 |

|

|

YY |

Na |

7 |

3 |

6 |

3 |

9 |

6 |

18 |

10 |

5 |

7.4 |

|

He |

0.546 |

0.484 |

0.703 |

0.446 |

0.838 |

0.569 |

0.934 |

0.865 |

0.533 |

0.658 |

|

|

Ho |

0.568 |

0.500 |

0.659 |

0.500 |

0.818 |

0.591 |

0.864 |

0.841 |

0.500 |

0.649 |

|

|

PIC |

0.518 |

0.384 |

0.649 |

0.353 |

0.806 |

0.536 |

0.918 |

0.838 |

0.446 |

0.605 |

|

|

WS |

Na |

9 |

2 |

6 |

3 |

9 |

7 |

22 |

12 |

3 |

8.1 |

|

He |

0.656 |

0.427 |

0.737 |

0.498 |

0.857 |

0.656 |

0.914 |

0.855 |

0.451 |

0.674 |

|

|

Ho |

0.696 |

0.372 |

0.543 |

0.609 |

0.911 |

0.652 |

0.935 |

0.804 |

0.457 |

0.669 |

|

|

PIC |

0.627 |

0.333 |

0.690 |

0.391 |

0.830 |

0.620 |

0.897 |

0.829 |

0.378 |

0.623 |

|

|

ZG |

Na |

9 |

3 |

7 |

2 |

9 |

9 |

21 |

11 |

5 |

8.4 |

|

He |

0.505 |

0.474 |

0.766 |

0.500 |

0.856 |

0.634 |

0.921 |

0.884 |

0.503 |

0.671 |

|

|

Ho |

0.438 |

0.426 |

0.625 |

0.521 |

0.933 |

0.625 |

0.875 |

0.813 |

0.438 |

0.633 |

|

|

PIC |

0.487 |

0.385 |

0.723 |

0.372 |

0.828 |

0.597 |

0.906 |

0.862 |

0.410 |

0.619 |

|

|

SS |

Na |

8 |

2 |

7 |

2 |

11 |

7 |

21 |

12 |

4 |

8.2 |

|

He |

0.743 |

0.449 |

0.762 |

0.491 |

0.862 |

0.564 |

0.941 |

0.865 |

0.528 |

0.689 |

|

|

Ho |

0.630 |

0.444 |

0.739 |

0.617 |

0.830 |

0.591 |

0.957 |

0.830 |

0.511 |

0.683 |

|

|

PIC |

0.709 |

0.346 |

0.715 |

0.368 |

0.836 |

0.516 |

0.926 |

0.839 |

0.426 |

0.631 |

|

|

DTL |

Na |

4 |

3 |

6 |

2 |

6 |

6 |

9 |

7 |

4 |

5.3 |

|

He |

0.466 |

0.467 |

0.726 |

0.392 |

0.718 |

0.780 |

0.869 |

0.819 |

0.590 |

0.647 |

|

|

Ho |

0.525 |

0.385 |

0.700 |

0.425 |

0.650 |

0.750 * |

0.872 |

0.825 |

0.250 * |

0.598 |

|

|

PIC |

0.411 |

0.366 |

0.669 |

0.312 |

0.666 |

0.742 |

0.842 |

0.783 |

0.523 |

0.591 |

* represents significant deviation from the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) after Bonferroni correction, p < 0.05.

3.2. Genetic Differentiation and Structure Among Populations

The pairwise Fst values and Nei’s standard genetic distance among seven bighead carp populations were presented in Table 5. No or slight levels of genetic differentiation were observed between pairwise populations with Fst values ranging from 0.0000 (between ZG and WS) to 0.0478 (between SS and DTL). To avoid potential bias from null alleles, we corrected the genetic differentiation analysis using the ENA (excluding null alleles) method in FreeNA [34] and found no significant difference in Fst values before and after correction (Fst values between the DTL population and others changed from 0.0345–0.0478 to 0.0361–0.0524). The corrected Fst values are shown in Supplementary Table S1. The AMOVA analysis showed that genetic variations among groups (upstream and midstream) accounted for only 0.60%, whereas 1.23% was among populations within groups and 98.16% was intro-populations, indicating that genetic variations were mainly from within populations.

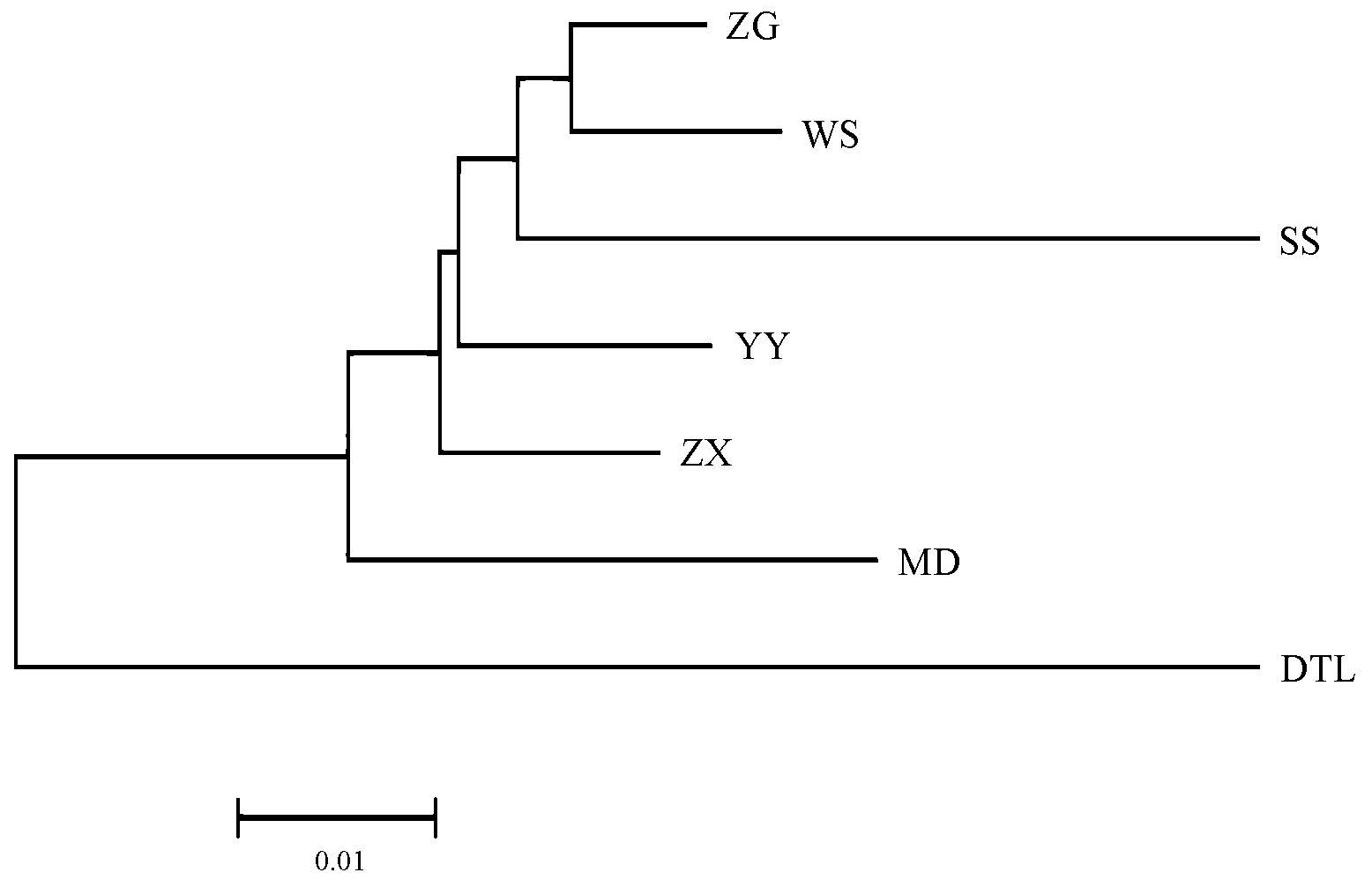

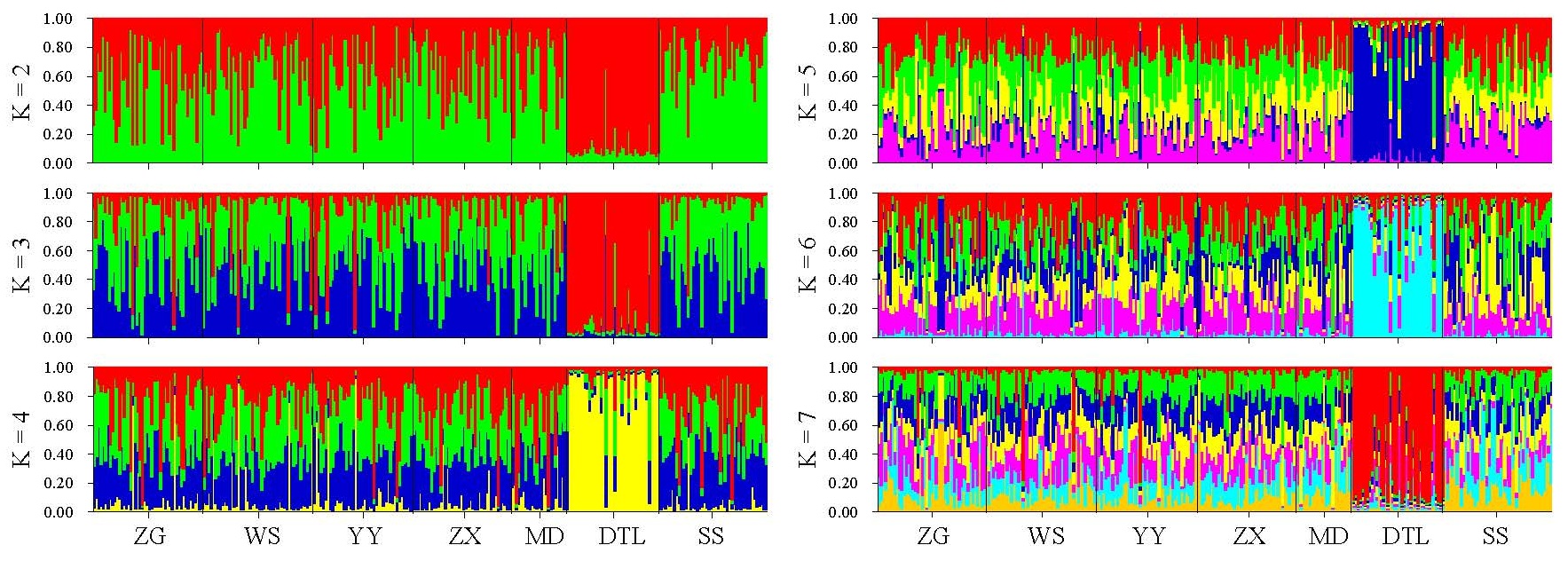

The genetic distances among seven bighead carp populations ranged from 0.0174 (between ZG and WS) to 0.1305 (between SS and DTL) (Table 5), and the clustering relationships revealed by a neighbor joining (NJ) tree (Figure 2) were basically consistent with the geographic distances among populations. The NJ tree showed that the DTL population formed one branch independently, and the others clustered into another branch. Results of genetic structure obtained by STRUCTURE are shown in Figure 3. In this study, the K values were selected as 1–7, and the calculations were repeated 20 times. According to the formula ΔK = m([L″K])/s[L(K)] [35], it was clear that the seven bighead carp populations belonged to two taxonomic groups (ΔK = 2). As shown in Figure 3, when K = 2 to K = 7, the DTL strain was distinctly different from the other populations, forming a separate subgroup, while the rest formed another group.

Table 5. Pairwise Fst values (below diagonal) and genetic distance (above diagonal) among seven bighead carp populations.

|

MD |

ZX |

YY |

WS |

ZG |

SS |

DTL |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

MD |

0.0419 |

0.0472 |

0.0569 |

0.0427 |

0.0641 |

0.1063 |

|

|

ZX |

0.0036 |

0.0239 |

0.0246 |

0.0258 |

0.0530 |

0.0958 |

|

|

YY |

0.0067 |

0.0008 |

0.0246 |

0.0270 |

0.0545 |

0.0975 |

|

|

WS |

0.0107 |

0.0029 |

0.0011 |

0.0174 |

0.0512 |

0.0992 |

|

|

ZG |

0.0045 |

0.0019 |

0.0027 |

0.0000 |

0.0465 |

0.0944 |

|

|

SS |

0.0110 |

0.0134 |

0.0156 |

0.0127 |

0.0110 |

0.1305 |

|

|

DTL |

0.0345 |

0.0356 |

0.0371 |

0.0371 |

0.0354 |

0.0478 |

Figure 2. Neighbor-Joining tree among seven bighead carp populations based on Nei’s genetic distance.

Figure 3. Bar plot assumed in different K values for individuals of seven bighead carp populations. Different colors represent different clusters inferred by various K.

3.3. Analysis of Mutation-Drift Equilibrium

The detailed results of the analysis of mutation-drift equilibrium for bighead carp populations were shown in Table 6. The DTL population exhibited significant heterozygosity excess under both the IAM and TPM models (IAM: p = 0.001; TPM: p = 0.002), but the signal was not significant under the conservative SMM model (p = 0.285). For the remaining populations, except ZG, significant heterozygosity excess was observed only under the IAM model (p < 0.05), with no significance under either the TPM or SMM models (p > 0.05), indicating that the inferred bottleneck effect is highly sensitive to the choice of mutation model. Since the IAM model tends to overestimate heterozygosity excess in microsatellite data, directly interpreting these patterns as evidence of a recent bottleneck is insufficient. However, the significant signal under the TPM model in the DTL population warrants high attention, suggesting it might have experienced a bottleneck effect in recent years.

Table 6. Analysis of mutation-drift equilibrium for bighead carp populations using the Wilcoxon rank test.

|

Populations |

p-Value under Different Models |

||

|---|---|---|---|

|

IAM |

TPM |

SMM |

|

|

MD |

0.005 * |

0.125 |

0.820 |

|

ZX |

0.024 * |

0.285 |

0.850 |

|

YY |

0.014 * |

0.326 |

0.787 |

|

WS |

0.005 * |

0.213 |

0.787 |

|

ZG |

0.102 |

0.455 |

0.820 |

|

SS |

0.002 * |

0.064 |

0.715 |

|

DTL |

0.001 * |

0.002 * |

0.285 |

* represents deviating from mutation-drift equilibrium at the level of p < 0.05; IAM, infinite allele model; TPM, two phase model; SMM, stepwise mutation model.

4. Discussion

Microsatellites, as co-dominant molecular markers, are the preferred choice for analyses of genetic variation due to their informative characteristics. In this study, we studied the genetic diversity of seven wild bighead carp populations from the upper and midstream of the Yangtze River by using nine polymorphic microsatellite markers. A total of 101 alleles, ranging from 4 to 26 per locus, were detected in 295 fish individuals (Table 3). The He and Ho of each locus were 0.463–0.934 and 0.443–0.903, respectively (Table 3), revealing significant allelic diversity in bighead carp sampled from up and down the TGD of the Yangtze River. PIC is an ideal index to measure the allele polymorphism of each locus, and any locus with PIC > 0.5 is classified as high polymorphism, followed by moderate polymorphism (0.25 < PIC < 0.5) and low polymorphism (PIC < 0.25) [36]. In the present study, Hysd849-1, Hysd18-1 and Hysd1148-1 showed moderate polymorphism when compared with the other loci, which were all high polymorphisms. In comparison to markers of bighead carp described in previous reports [22,37], ours seem to be more polymorphic in terms of allele number due to high variability of the loci and superior genotyping method.

Moderate levels of genetic diversity were found in all seven bighead carp populations in this study, five of which were collected from the TGR (upstream Yangtze River). Few studies [12,13,22,37] on the genetic diversity of bighead carp from Yangtze River have been conducted by various molecular markers, especially from the upstream Yangtze River [24]. Geng et al. (2006) [24] analyzed the genetic diversity of two bighead carp populations from Jiangxi (mid-and-lower stream) and Sichuan (upstream) provinces of China by 17 microsatellites, with the average Na, He and Ho values of each population being 3.3–3.9, 0.422–0.452 and 0.360–0.385, respectively. It is evident that the genetic diversity of bighead carp from the upper and midstream Yangtze River in this study (Table 4) is higher than that of previous reports [12,13,24]. Several factors may cause this difference. First, the limited sample size in each population may cause biased estimation of genetic variations, and we used a large sample size of more than 40, except for the MD population. Second, the microsatellite markers used in this study have greater allelic diversity than those used in previous studies. Third, the resolution of microsatellite genotyping using the LI-COR 4300 DNA analyzer was much higher than the traditional genotyping method [38].

Detecting moderate genetic diversity among bighead carp populations across collection sites supports the biology of this species, which maintains large effective populations and high fecundity. The presence of such biological traits contributes to the conservation of allelic richness, as also described by Li et al. [39], who reported moderate diversity in 14 Yangtze populations based on RAD-seq analysis. Furthermore, Zhu et al. [40]. observed He values ranging between 0.706 and 0.734 in the middle and lower Yangtze River, reflecting stable genetic diversity despite environmental changes. Fish habitats are significantly altered by dam construction, by fragmenting populations, ultimately reducing gene flow, causing inbreeding, and increasing genetic drift [18]. While biological traits, including wide dispersal ability and human-assisted stocking, may help maintain connectivity and reduce the dam’s isolating effects.

Environmental and biological factors have been demonstrated to influence fish genetic diversity substantially, with warmer and more stable environments promoting higher diversity by maintaining population sizes and accelerating mutation rates [5,41]. In the Yangtze River, recent research on sediments and fish communities shows that fish biodiversity responds to habitat changes in complex and time-dependent ways, indicating that genetic diversity is influenced by both spatial and temporal environmental variation [41]. The genetic structure of the Dongting Lake (DTL) population differs from that of the homogeneous groups upstream and downstream of the TGD, supporting the concept that ecosystem isolation and historical demographic events affect genetic structure [42].

With respect to genetic divergence, slight genetic differentiations [43] (Fst = 0.0000–0.0478, Table 5) were observed among bighead carp populations, and the genetic variations were mainly from intro-populations (98.16%). The weak genetic differentiation observed among bighead carp populations upstream and midstream is consistent with previous research on this species. As reported by Li et al. [39], RAD sequencing in the Yangtze River Basin revealed low pairwise Fst values across 14 H. nobilis populations, suggesting high gene flow and weak divergence. Similarly, Zhu et al. [40] detected moderate genetic diversity and weak genetic differentiation (Fst = 0.02) among eight populations of H. nobilis in the middle and lower Yangtze River using microsatellite DNA markers. Polymorphic microsatellite studies on wild bighead carp found limited differentiation, Wang et al. [44] reporting (Fst < 0.05) among populations of the middle Yangtze, which indicates genetic homogeneity between most groups. Zhao and Li (1996) [13] used isozyme markers to analyze genetic differentiation among silver carp, bighead carp, black carp and grass carp populations in the middle and downstream Yangtze River, and found that each of the four major Chinese farmed carp could be viewed as a single group. However, significant differentiation among populations of silver carp, bighead carp, and black carp from the middle and downstream Yangtze River was observed according to Li & Lu’s study (1998) [22] by SSR. Geng et al. (2006) [24] also found significant differentiation between two bighead carp populations from Jiangxi (mid-and-downstream) and Sichuan (upstream) provinces using seventeen microsatellites. While no significant differentiation had been detected between two bighead carp populations from Hubei (midstream) and Jiangsu (downstream) provinces in the Yangtze River using AFLP markers by Yan et al. (2011) [12]. The results of studies performed by previous researchers were different due to various markers and genotyping methods used. In the present investigation, we adopted higher polymorphic microsatellite markers and superior genotyping methods that made the results credible. Although weak differentiation was observed in the studied populations, this suggests continued gene flow and connectivity across the dam [18,45]. Overall, these findings indicate that bighead carp populations across the Yangtze River maintain connectivity regardless of barriers such as dams, stocking practices, or environmental change. Although it is difficult to compare with previous studies, our results support that the seven bighead carp populations from the upper and midstream Yangtze River can be regarded as one population [46].

The construction of huge hydroelectric dams has affected biodiversity at all scales by changing communities, species and even genetic levels [47]. Clear changes in lotic and lentic species, elimination of some fish species and reduction of fishery productivity have been reported by many authors [47,48,49]. Among the five sampling sites of TGR, more bighead carp fish appeared in ZG, where the lacustrine zone formed near the dam, as this fish is a lentic species, and only 25 individuals were caught from MD where dominated by lotic fish species. In this investigation, the presented genetic diversity of bighead carp populations coming from TGR and SS (close to TGD) is much higher than DTL population, which is located far downstream of the TGD, suggesting that the population resources of bighead carp upstream are more abundant than the midstream Yangtze River. To our surprise, SS (downstream of the TGD) also showed moderate genetic variation, and no genetic differentiation was detected between SS and the five populations from TGR. These results may reveal that the little genetic differentiations among DTL and the others were mainly influenced by the relatively long geographical distance, rather than by the barrier formed by TGD so far.

Even though little genetic differentiations were detected among populations, clustering analysis (Figure 2) and structure analysis (Figure 3) consistently supported that the seven bighead carp populations were divided into two sub-groups, of which the DTL strain was distinctly independent alone and the rest grouped as another. Geographical isolation [50] and artificial breeding [51] tend to accelerate genetic differentiation among populations. Spatial separation of DTL from other populations contributes to its distinctiveness, and localized environmental conditions may further restrict gene flow and encourage subtle differentiation at the population level. Although no strong geographical barrier exists between the lake and the Yangtze mainstream, the presence of distinct natural spawning grounds along the river basin supports the maintenance of relatively independent genetic backgrounds. In addition, large-scale stocking activities in the middle reaches of the Yangtze River may have introduced hatchery-reared fingerlings with genetic profiles differing from those of wild mainstream populations, potentially reinforcing divergence. Collectively, these elements—stocking history, partial spatial isolation, and environmental effects—provide plausible explanations for the slight but consistent genetic independence observed in the DTL population. Nevertheless, it is worth noting that DTL populations showed an excessive heterozygosity phenomenon (p < 0.05) under both IAM and TPM models, indicating that this population might have experienced a bottleneck effect in recent years, causing the population to be reduced [52,53]. Under the operation of the TGR, attention to such man-made factors as overfishing should be seriously paid to avoid the irreversible damage to germplasm resources of bighead carp. Stock enhancement is a practical choice, but it should be properly guided.

5. Conclusion Remarks

In this study, we detected moderate genetic diversities in all seven bighead carp populations, including five from the upper and two (SS and DTL) from the middle reaches of the Yangtze River. Relatively higher genetic variations of bighead carp populations come from the upstream Yangtze River and SS (close to TGD) than DTL (far downstream the TGD) population were observed, revealing that the genetic diversity of bighead carp in the upstream was more abundant than the midstream Yangtze River. Weak differentiation among seven populations from upstream and midstream Yangtze River suggests that these populations can be viewed as one group, which could provide some reference for evaluating the influence of TGD on the genetic structure of bighead carp populations. This study provides insights and positive significance to the conservation and sustainable utilization of bighead carp germplasm resources in the Yangtze River.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be found at: https://www.sciepublish.com/article/pii/819, Table S1: Pairwise Fst values among seven bighead carp populations after correction using FreeNA.

Acknowledgments

Authors thank Zhongjie Li, Yuxi Nian, and Deqing Tan for their technical assistance for fish sampling during field trips. Xiu Feng and Haiyang Liu are also acknowledged for their generous assistance in data analysis.

Author Contribution

J.T. conceived and designed the experiments, authored or reviewed drafts of the paper, approved the final draft. L.T. and M.P. conceived and designed the experiments, performed the experiments, analyzed the data, prepared figures and/or tables, authored or reviewed drafts of the paper, approved the final draft. X.W. and Y.Z. prepared figures and/or tables, authored or reviewed drafts of the paper. X.Y. authored or reviewed drafts of the paper, approved the final draft.

Ethics Statement

The Committee for Animal Experiments of the Institute of Hydrobiology, the Chinese Academy of Sciences, China, approved all the experimental procedures and field study of the fish in the study (FI25-B3, 16 July 2012). The methods used in this study were carried out in accordance with the Laboratory Animal Management Principles of China.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data are available upon request.

Funding

This study was supported by research grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31272647), State Key Laboratory of Freshwater Ecology and Biotechnology (2016FBZ05) and Scientific Research Project of China Three Gorges Corporation (CT12-08-01).

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

-

Tautz D, Renz M. Simple sequences are ubiquitous repetitive components of eukaryotic genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 1984, 12, 4127–4138. doi:10.1093/nar/12.10.4127. [Google Scholar]

-

Gastier J, Pulido J, Sunden S, Brody T, Buetow K, Murray J, et al. Survey of trinucleotide repeats in the human genome: Assessment of their utility as genetic markers. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1995, 4, 1829–1836. doi:10.1093/hmg/4.10.1829. [Google Scholar]

-

Kijas J, Thomas M, Fowler J, Roose M. Integration of trinucleotide microsatellites into a linkage map of Citrus. Theor. Appl. Genet. 1997, 94, 701–706. doi:10.1007/s001220050468. [Google Scholar]

-

Liu Z, Cordes J. DNA marker technologies and their applications in aquaculture genetics. Aquaculture 2004, 238, 1–37. doi:10.1016/J.AQUACULTURE.2004.05.027. [Google Scholar]

-

Manel S, Guerin P, Mouillot D, Blanchet S, Velez L, Albouy C, et al. Global determinants of freshwater and marine fish genetic diversity. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 692. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-14409-7. [Google Scholar]

-

Sanz N, Nebot A, Araguas RM. Microsatellites as a good approach for detecting triploidy in brown trout hatchery stocks. Aquaculture 2020, 523, 735218. doi:10.1016/j.aquaculture.2020.735218. [Google Scholar]

-

Lu C, Sun Z, Xu P, Na R, Lv W, Cao D, et al. Novel microsatellites reveal wild populations genetic variance in pike-perch (Sander lucioperca) in China. Aquac. Rep. 2022, 23, 101031. doi:10.1016/j.aqrep.2022.101031. [Google Scholar]

-

Tang H, Zhang W, Tao C, Zhang C, Gui L, Xie N, et al. Estimation of genetic parameters for upper thermal tolerance and growth traits in grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella). Aquaculture 2025, 598, 742073. doi:10.1016/j.aquaculture.2024.742073. [Google Scholar]

-

Wang X, Yu X, Feng J, Zhang Q, Qu C, Liu Q, et al. Estimation of the heritabilities for body Shape and body weight in Yellow River carp (Cyprinus carpio haematopterus) based on a molecular pedigree. J. Appl. Ichthyol. 2023, 2023, 1–8. doi:10.1155/2023/9326728. [Google Scholar]

-

Pang M, Yu X, Tong J. The microsatellite analysis of genetic diversity of five silver carp populations in the Three Gorges Reservoir of the Yangtze River. Acta Hydrobiol. Sin. 2015, 39, 869–876. doi:10.7541/2015.115. [Google Scholar]

-

Li S, Fang F. On the geographical distribution of the four kinds of pond-cultured carps in China. Acta Zool. Sin. 1990, 36, 244–249. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=1UNTTfPTmO_4HtmQ3GA9E4okryKWlXHXjfjlu

HlQ1FRyEBysix5iX_3o_vKgFiz6U6ekW0pKx74T7d5kQ47upnQj11ILUjAnLdXYIR9vl-beTkQ9DHzFRSSYMjQeE2kfMSoK06uvAUqpwhL6FOZKeOrZm3TPS1wyMddrHqY6QYxIfQGqMHRqlA==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 28 November 2025). [Google Scholar] -

Yan J, Zhao J, Li S, Zheng D, Yang C. Genetic variation of bighead carp Aristichthys nobilis from Chinese native populations and introduced populations by AFLP. J. Fish. Sci. China 2013, 18, 283–289. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=1UNTTfPTmO_vDfCj7tX7nLWfOIA5in69nZXLm6fpYfFqKBCa5sKGh8GCykxvB8jT8UGzPoEMxC1R9_UAeSss5UbJgaOQsFriPGMJNtDga0E0fnWQduOhSLR6gvdUCWS0uum2AoGbl7T1dHHUDXa2rQuURqEzqOZLjeh8wJbm4b7JduxzCliunA==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 28 November 2025). [Google Scholar]

-

Zhao J, Li S. Isoenzyme analysis of population divergence of silver carp, bighead carp, grass carp and black carp in the middle and lower stream of Changjiang River. J. Fish. China 1996, 20, 104–110. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=1UNTTfPTmO8mYI0sgTjS5bx3XuJG6i7JTCVr6xTjJLbzx9MaSDwWtb1CdP4hlqsFswk5BWAKcObNkAseiNcscXG_LKHemq6FWLsXIdrgqvfvUEHjUzk5YLUUX2UqV1W-CtEzSVZk7gQmqU8Fj2m72GNqbWXsjoHG97O6waZA414=&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 28 November 2025). [Google Scholar]

-

Chen D, Duan X, Liu S, Shi W, Wang B. On the dynamics of fishery resources of the Yangtze River and its management. Acta Hydrobiol. Sin. 2002, 26, 685–690. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=1UNTTfPTmO9on_dT-EtCIddaAwQ87a6WpQy5ph5aJND8mibatj8peWdu9alxJMpcVinbKl0-u8kCCW_M1niWBKHc4NmXjxr5rWGQIk58xg_AD4pSS7M4IV7O9vNPoBoBzpsjUxiPpCATl-OPi7udBNqCGSeG93E4LRflJA8a3ovj735vBNi0lg==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 28 November 2025). [Google Scholar]

-

Perera H, Li Z, De Silva S, Zhang T, Yuan J, Ye S, et al. Effect of the distance from the dam on river fish community structure and compositional trends, with reference to the Three Gorges Dam, Yangtze River, China. Acta Hydrobiol. Sin. 2014, 38, 438–445. doi:10.3724/issn1000-3207-2014-3-438-d. [Google Scholar]

-

Baxter R. Environmental effects of dams and impoundments. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 1977, 8, 255–283. doi:10.1146/annurev.es.08.110177.001351. [Google Scholar]

-

Cooper A, Infante D, Daniel W, Wehrly K, Wang L, Brenden T. Assessment of dam effects on streams and fish assemblages of the conterminous USA. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 586, 879–889. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.02.067. [Google Scholar]

-

Zarri L, Palkovacs E, Post D, Therkildsen N, Flecker A. The evolutionary consequences of dams and other barriers for riverine fishes. BioScience 2022, 72, 431–448. doi:10.1093/biosci/biac004. [Google Scholar]

-

Visser S, Barbarossa V, Keijzer T, Verones F, Dorber M. Characterizing dam fragmentation impacts on freshwater fish within life cycle impact assessment. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2025, 114, 107929. doi:10.1016/j.eiar.2025.107929. [Google Scholar]

-

Li S, Yang Q, Xu J, Wang C, Chapman D, Lu G. Genetic diversity and variation of mitochondrial DNA in native and introduced bighead carp. Trans. Am. Fish. Soc. 2011, 139, 937–946. doi:10.1577/T09-158.1. [Google Scholar]

-

Zhang D, Xi Z, Dai Y, Lai Y, Yao F, Feng D, et al. Studies on genetic diversity of bighead carp (Aristichthys nobilis) in the Yangtze River. Wuhan Univ. J. 1999, 45, 857–860. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=1UNTTfPTmO_lpTrH9PkSyGjlPgjFqEiz2tSifdlEEdooYKzr1w-yJY9IaoFPu8G28k-j3rLGi059RI2ksRVPLO1AvztG_KLab_Lg8OazBYWswHKvl-Ei84atujiYU7q6DsrFwZc2u5bcsLSJ-usw-F1m81GqpGG0pF2QcY4S6UnYN7uhvnNGBg==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 28 November 2025). [Google Scholar]

-

Li S, Lv G, Bernatchez L. Diversity of mitochondrial DNA in the populations of silver carp, bighead carp, grass carp and black carp in the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze River. Acta Zool. Sin. 1998, 44, 82–93. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=1UNTTfPTmO-RFqZyCQW8EV5WQv0jlF3EFosJrbFmkE43LkXYod3DIgP2G0-tlUVF9bDrjVjbLSn3uOx_t6YiKQc-dk2i1BTkHAZyDUzxh4cPQork2GsnHjydev2G6Oz1681WKHWj2ABU7wtC5Ao2rKN_j5SD5n2cV_g-jpbj7ms=&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 28 November 2025). [Google Scholar]

-

Xia D, Yang H, Wu T, Dong Z, Jian J, Cao Y. Study on the population genetic structures of black carp, grass carp, silver carp and bighead fish in tian-e-zhou open old course of the Yangtze River. J. Fish. China 1996, 3, 11–18. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=1UNTTfPTmO87VJH4v6fS_HtD9XwVnTLkpbhVWdsFPE3Yxzwbv0XJw8Tg8GoAU7D4KF5OHTTRrhG34UM0w6et9v0GCB6zom1cpX2eokwJyj6olIX4tkfvgguNSkomI6WpSJ3ZwBPVErXRFSZotXL8YqFTDThONLNlZdAKfuF6Bz8=&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 28 November 2025). [Google Scholar]

-

Geng B, Sun X, Liang L, Ouyang H, Tong J. Microsatellite analysis of genetic diversity of Aristichthys nobilis in China. Hereditas 2006, 28, 683–688. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=1UNTTfPTmO-4TrQ4Br8lSP2hAIbus0H-FML1ldTqzn4bmGn43wtEerS8xHaSo4JNmko8dmj9ZoEagA2gHNLQ9XO97OrDAGQbYpF2lzzvZEAa3IsfhSXGYC8CJ6eQZogrtVl3fvP81v_CJuHAv16e7I21jAbnixIi0Uqkp7dRkiD8SKRwzQdTUQ==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 28 November 2025). [Google Scholar]

-

Sambrook J, Fritsch E, Maniatis T. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual; Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory: Laurel Hollow, NY, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

-

Zhang J, Wei C. Establishment a SSR-PCR system of tea plant [Camellia sinensis (L.) O. Kuntze] based on the 4300 DNA analysis system. J. Tea Sci. 2014, 34, 481–488. doi:10.13305/j.cnki.jts.2014.05.009. [Google Scholar]

-

Yeh F, Yang R, Boyle T, Ye Z, Xiyan J. Popgene32, Microsoft Windows-Based Freeware for Population Genetic Analysis, Version 1.32; Molecular Biology and Biotechnology Centre, University of Alberta: Edmonton, AB, Canada, 2000. [Google Scholar]

-

Park S. Trypanotolerance in West African Cattle and the Population Genetic Effects of Selection. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Dublin, Dublin, Ireland, 2001. [Google Scholar]

-

Excoffier L, Lava G, Schneider S. Arlequin (version 3.0): An integrated software package for population genetics data analysis. Evol. Bioinform. Online 2005, 1, 47–50. doi:10.1177/117693430500100003. [Google Scholar]

-

Excoffier L, Smouse P, Quattro J. Analysis of molecular variance inferred from metric distances among DNA haplotypes: Application to human mitochondrial DNA restriction data. Genetics 1992, 131, 479–491. doi:10.1093/genetics/131.2.479. [Google Scholar]

-

Pritchard J, Stephens M, Donnelly P. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data. Genetics 2000, 155, 945–959. doi:10.1093/genetics/155.2.945. [Google Scholar]

-

Falush D, Stephens M, Pritchard J. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data: Linked loci and correlated allele frequencies. Genetics 2003, 164, 1567–1587. doi:10.1093/genetics/164.4.1567. [Google Scholar]

-

Maruyama T, Fuerst P. Population bottlenecks and nonequilibrium models in popuation genetics II. number of alleles in a small population that was formed by a recent bottleneck. Genetics 1985, 111, 675–689. doi:10.1093/genetics/111.3.675. [Google Scholar]

-

Chapuis M, Estoup A. Microsatellite null alleles and estimation of population differentiation. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2007, 24, 621–631. doi:10.1093/molbev/msl191. [Google Scholar]

-

Evanno G, Regnaut S, Goudet J. Detecting the number of clusters of individuals using the software structure: A simulation study. Mol. Ecol. 2005, 14, 2611–2620. doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2005.02553.x. [Google Scholar]

-

Nei M. Genetic distance between populations. In Molecular Evolutionary Genetics; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1987; pp. 180–211. [Google Scholar]

-

Zhang M, Liu K, Xu D, Duan J, Zhou Y, Fang D, et al. Analysis of genetic diversity in populations released for stock enhancement and population caught in natural water of bighead carp in the lower reaches of the Yangtze River using microsatellite markers. Acta Agric. Univ. Jiangxiensis 2013, 35, 579–586. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=1UNTTfPTmO-XVX8YOndUx0lrHY_ffLKkXAFioaeSDNDn6eJAWvPmCdlZLvBLptSw9hAVjQtq4HoOdhBbX6qnN9OGVuLctfSOXuYoBVNeLpOfcvt6Fu8lWcMjCIp0ctb_Xwk2ZiuE2dwKMMz-tpYOqSwtd4mtHvW8lFG35r_TBpQyMQQ3vijvqQ==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 28 November 2025). [Google Scholar]

-

Chen C, Yu Q, Hou S, Li Y, Eustice M, Skelton R, et al. Construction of a sequence-tagged high-density genetic map of papaya for comparative structural and evolutionary genomics in brassicales. Genetics 2007, 177, 2481–2491. doi:10.1534/genetics.107.081463. [Google Scholar]

-

Li W, Yu J, Que Y, Hu X, Wang E, Liao X, et al. Population genetic investigation of Hypophthalmichthys nobilis in the Yangtze River basin based on RAD sequencing data. Biology 2024, 13, 837. doi:10.3390/biology13100837. [Google Scholar]

-

Zhu W, Fu J, Luo M, Wang L, Wang P, Liu Q, et al. Genetic diversity and population structure of bighead carp (Hypophthalmichthys nobilis) from the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze River revealed using microsatellite markers. Aquac. Rep. 2022, 27, 101377. doi:10.1016/j.aqrep.2022.101377. [Google Scholar]

-

Dong F, Cheng P, Sha H, Yue H, Wan C, Zhang Y, et al. Genetic diversity and population structure analysis of blunt snout bream (Megalobrama amblycephala) in the Yangtze River Basin: Implications for conservation and utilization. Aquac. Rep. 2024, 35, 101925. doi:10.1016/j.aqrep.2024.101925. [Google Scholar]

-

Kim K, Kwak Y, Sung M, Cho S, Bang I. Population structure and genetic diversity of the endangered fish black shinner Pseudopungtungia nigra (Cyprinidae) in Korea: A wild and restoration population. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 9692. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-36569-4. [Google Scholar]

-

Weight S. Evolution and the Genetics of Population Variability within and Among Natural Population; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

-

Wang J, Lei Q, Jiang H, Liu J, Yu X, Guo X, et al. Genetic diversity among wild and cultured bighead carp (Hypophthalmichthys nobilis) in the middle Yangtze River by microsatellite markers. Genes 2025, 16, 586. doi:10.3390/genes16050586. [Google Scholar]

-

Luo T, Fang A, Zhou F, Xu P, Peng X, Zhang Y, et al. Genetic diversity, habitat relevance and conservation strategies of the silver carp in the Yangtze River by simple sequence repeat. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2022, 10, 850183. doi:10.3389/fevo.2022.850183. [Google Scholar]

-

Balloux F, Lugon-Moulin N. The estimation of population differentiation with microsatellite markers. Mol. Ecol. 2002, 11, 155–165. doi:10.1046/j.0962-1083.2001.01436.x. [Google Scholar]

-

Rosenberg D, Berkes F, Bodaly R, Hecky R, Kelly C, Rudd J. Large scale impacts of hydroelectric development. Environ. Rev. 1997, 5, 27–54. doi:10.1139/er-5-1-27. [Google Scholar]

-

Agostinho A, Pelicice F, Gomes L. Dams and the fish fauna of the neotropical region: Impacts and management related to diversity and fisheries. Braz. J. Biol. 2008, 68, 1119–1132. doi:10.1590/S1519-69842008000500019. [Google Scholar]

-

Gao X, Zeng Y, Wang J, Liu H. Immediate impacts of the second impoundment on fish communities in the Three Gorges Reservoir. Environ. Biol. Fishes 2010, 87, 163–173. doi:10.1007/s10641-009-9577-1. [Google Scholar]

-

Xiao M, Bao F, Cui F. Pattern of genetic variation of yellow catfish Pelteobagrus fulvidraco Richardso in Huaihe River and the Yangtze River revealed using mitochondrial DNA control region sequences. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2014, 41, 5593–5606. doi:10.1007/s11033-014-3251-1. [Google Scholar]

-

Jiang B, Fu J, Dong Z, Fang M, Zhu W, Wang L. Maternal ancestry analyses of red tilapia strains based on D-loop sequences of seven tilapia populations. PeerJ 2019, 7, e7007. doi:10.7717/peerj.7007. [Google Scholar]

-

Nei M, Maruyama T, Chakraborty R. The bottleneck effect and genetic variability in populations. Evolution 1975, 29, 1–10. doi:10.2307/2407137. [Google Scholar]

-

Cornuet J, Luikart G. Description and power analysis of two tests for detecting recent population bottlenecks from allele frequency data. Genetics 1996, 144, 2001–2014. doi:10.1093/genetics/144.4.2001. [Google Scholar]