Revisiting the Conservation Challenges of Wild Argali (Ovis ammon ammon L.) in the Altai Mountain-Steppe under Climate and Anthropogenic Pressures

Received: 30 October 2025 Revised: 19 November 2025 Accepted: 15 December 2025 Published: 24 December 2025

© 2025 The authors. This is an open access article under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

1. Introduction

The argali, subspecies (Ovis ammon ammon L.), is the largest sheep on the planet. Rams can achieve a body length of 174–180 cm, a height of 114–125 cm, and a weight of up to 200 kg (Figure 1). The species is listed as “critically endangered” in the Red Data Book of the Russian Federation and as “near threatened” in the IUCN Red List [1,2]. In addition to its value as a genome carrier, the argali is an important element in the food chain of another rare species: the snow leopard.

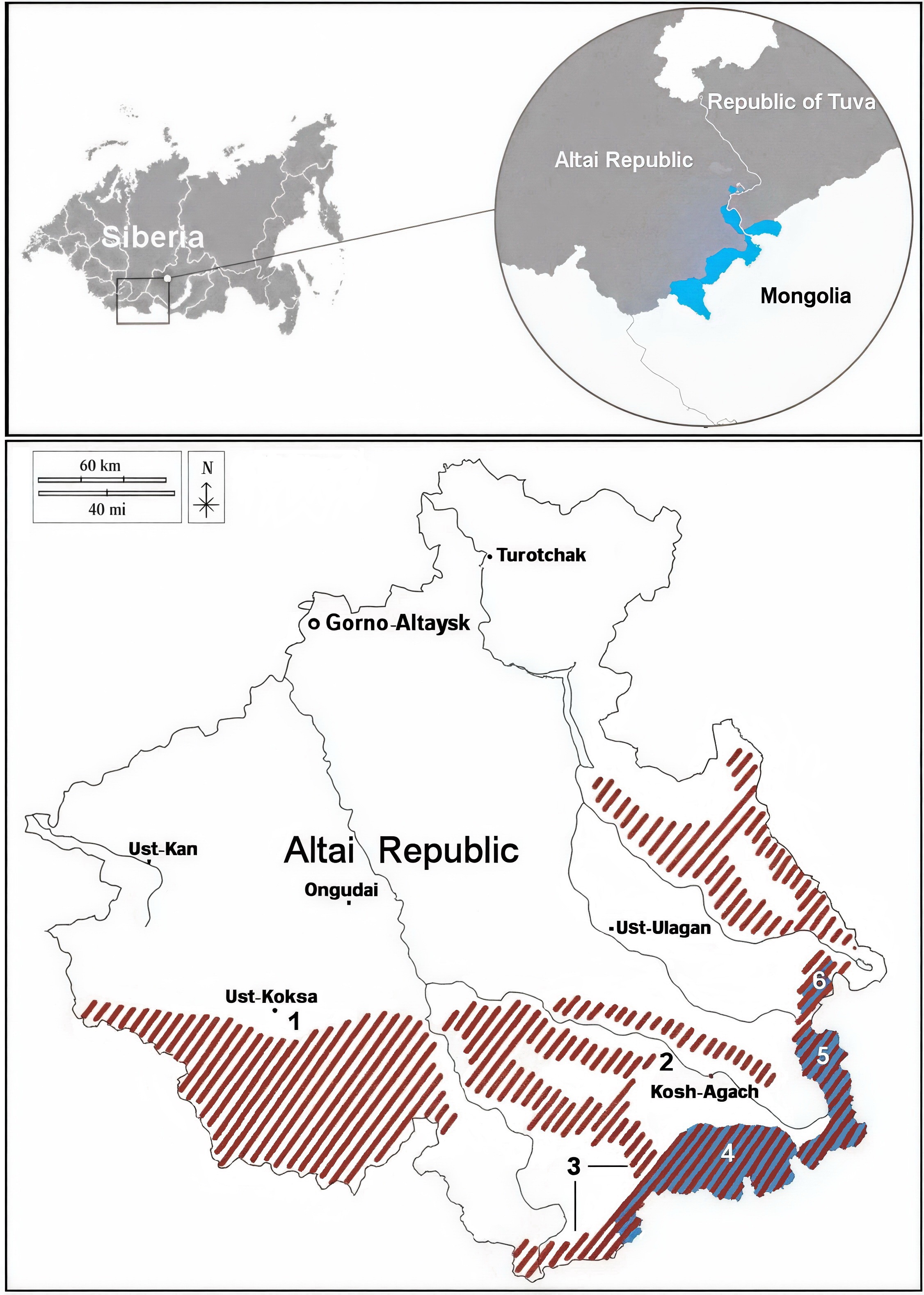

The modern habitat of the argali (Figure 2A) includes the most arid areas of the Altai and Tuva Mountains. However, the historical range of this wild sheep in Russia covered almost the entire territory of the Altai-Sayan mountain country (Southern Siberia), right up to Transbaikalia (Eastern Siberia). At the beginning of the eighteenth century, argali inhabited the humid Altai Mountains, where a distinct belt of dark coniferous mountain taiga and mesomorphic herbaceous plants predominated around the Ust-Koksa area (Figure 2B, point 1,2 [3]). By 1826, argali had disappeared from this area, mostly because of uncontrolled hunting with guns. Therefore, the modern argali range in the mountain steppes is the result of anthropogenic impact.

Figure 2. (A) The modern distribution of argali straddling the two republics of southern Siberia (Russia) and Mongolia. (B) Reconstruction of the argali historical range in the 18th and early 19th centuries in the Altai Republic (red shading) and the modern range (blue). 1, 2—areas in which the traces of argali were found in the early 19th century, 3—areas where argali visits are currently periodically observed, 4—area of argali habitat on the Sailugem Ridge, 5—area of argali habitat on the Chikhachev Ridge, 6—area of argali habitat in the south of the Altai Nature Reserve. Based on [4].

Thus, the reduction of the argali range and the localization of its groups in the arid mountainous territories of Tuva, South-Eastern Altai, and adjacent regions of Mongolia were caused by human activity.

The mountain steppes of Southern Siberia represent an ecologically important biodiversity refuge. Steppe vegetation provides forage for both domesticated and wild sheep. At the same time, the steppe vegetation is experiencing strong anthropogenic and additional new climate pressures.

Developing a conservation strategy for argali in mountain-steppe landscapes requires understanding its current habitats and predicting how these may change under global climate dynamics. At the same time, according to Shelford’s law of tolerance [5], changes in habitat, driven by current global climate dynamics, will occur much faster in the arid regions of Altai than in more humid regions.

This paper is a continuation of our previous work [4] in which we outline challenges to conserve the critically endangered keystone argali (Ovis ammon ammon). Since its publication, new data have emerged with limited distribution on argali population dynamics [6] and vegetation degradation [7]. For example, in argali areas, some cases of irreversible degradation of the steppes have been found. Soil cover destruction has led to the formation of specific floristic and phytocenological complexes, which we call “rocky steppes” [7]. The new data allow us to redefine the role of vegetation in the argali conservation strategy in the Mountains of Southern Siberia.

2. Materials and Methods

During 2022–2025, we conducted research on the steppe vegetation of the Sailugem Ridge to understand its importance as a resource for the argali population and for the mountain ecosystem’s functioning in general.

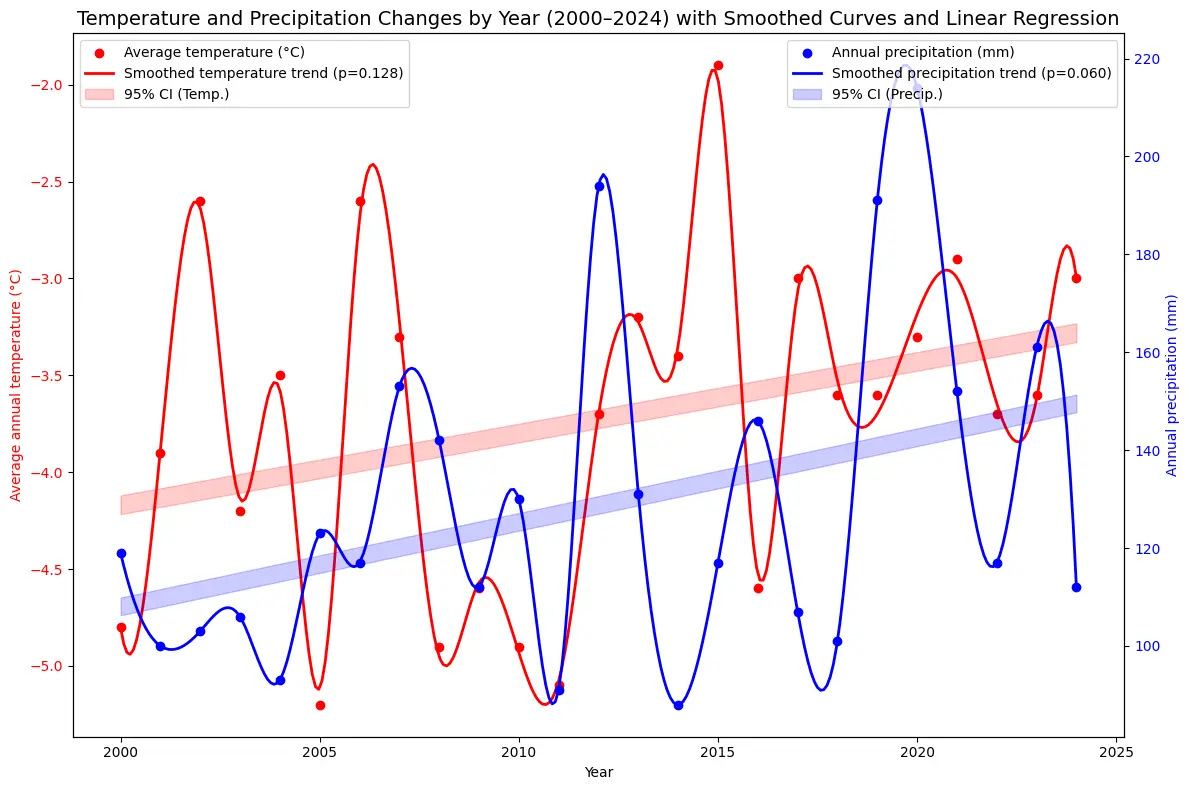

The climate of the study area is temperate and is influenced by a powerful Asian anticyclone with partly cloudy, frosty weather in winter and cool summers with an average summer temperature of about 14 °C [8,9]. The mountainous areas affect local air movement: there are glacial, mountain-slope valley winds, and foehn winds. These winds have local impacts on the depth and amount of snow cover, soil moisture, and air temperature. Climate is changing: the most significant changes in temperature and precipitation are occurring in the Chuya Depression. Mean annual temperature and summer precipitation have increased throughout the region, while winter precipitation has decreased [8,10]. Despite the increase in summer precipitation, the recent changes indicate some trend toward increased aridization, as the observed increase in air temperatures is not accompanied by a corresponding increase in precipitation (Figure 3).

Standard geobotanical descriptions were performed at 9 key sites. The criterion for identifying key sites identification was relatively uniform coverage of the Sailugem Ridge. The average size of a key site varied about 1000 m2 and reflected the diversity of plant communities within an altitudinal zone of a given slope aspect. Each plant community was studied over 100 m2 within each key site. Within each 100 m2 area, four 50 × 50 cm grids were subdivided into 10 × 10 cm squares to make a description. Geobotanical descriptions with a grid were made 4 times per season for each key site with high vegetation homogeneity and up to 10 times per season for each key site with little vegetation homogeneity, to study the seasonal dynamics of phytocenosis. The total projective cover—an indicator that determines the relative phytocenosis’s protection on the soil surface was also assessed. Four 1 m2 samples of aboveground phytomass of herbaceous plants were taken from each key site, dried in a thermostat to constant weight, and weighed on a laboratory scale. The dry mass of grass in a 1 m2 square was converted to a per hectare basis.

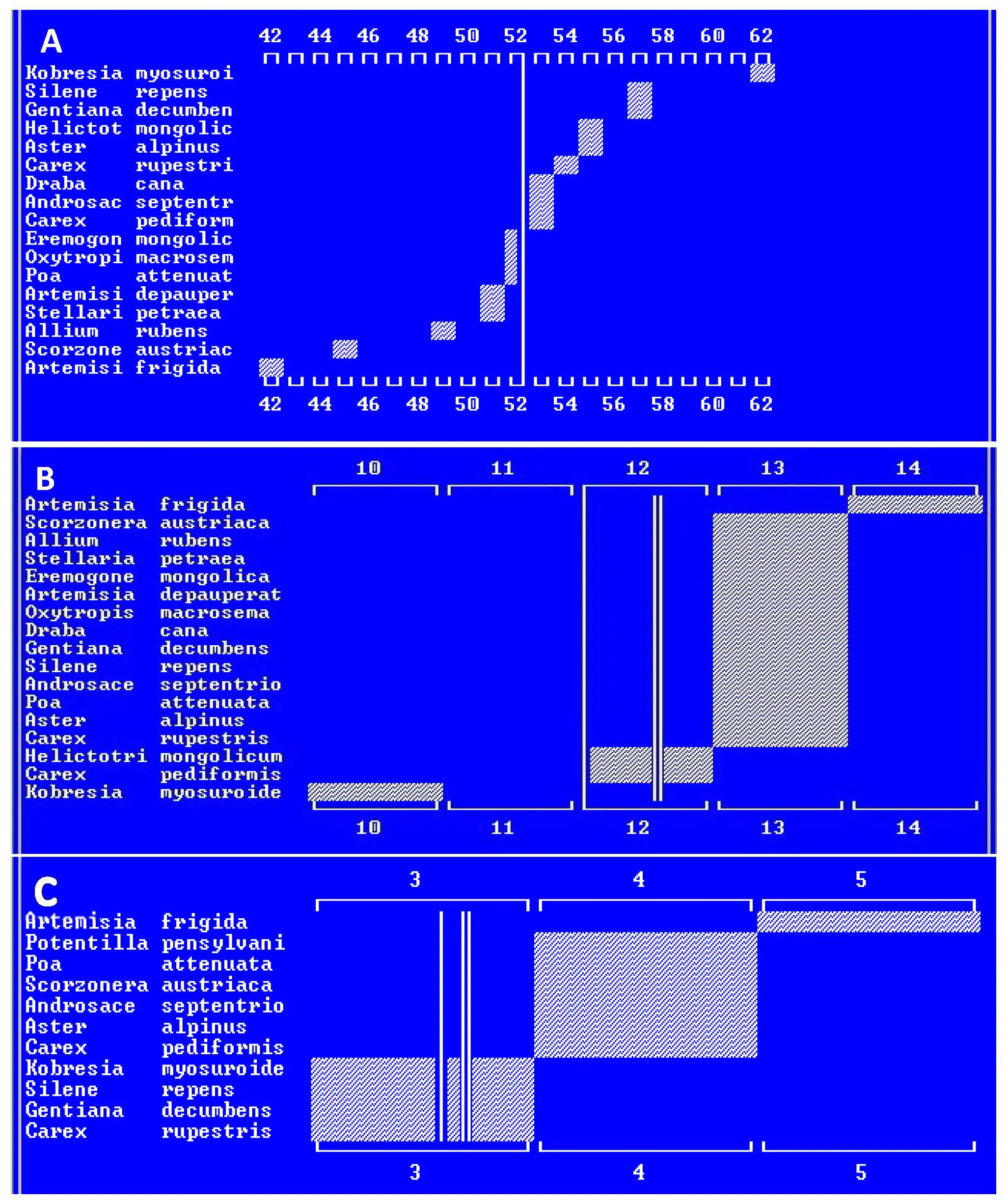

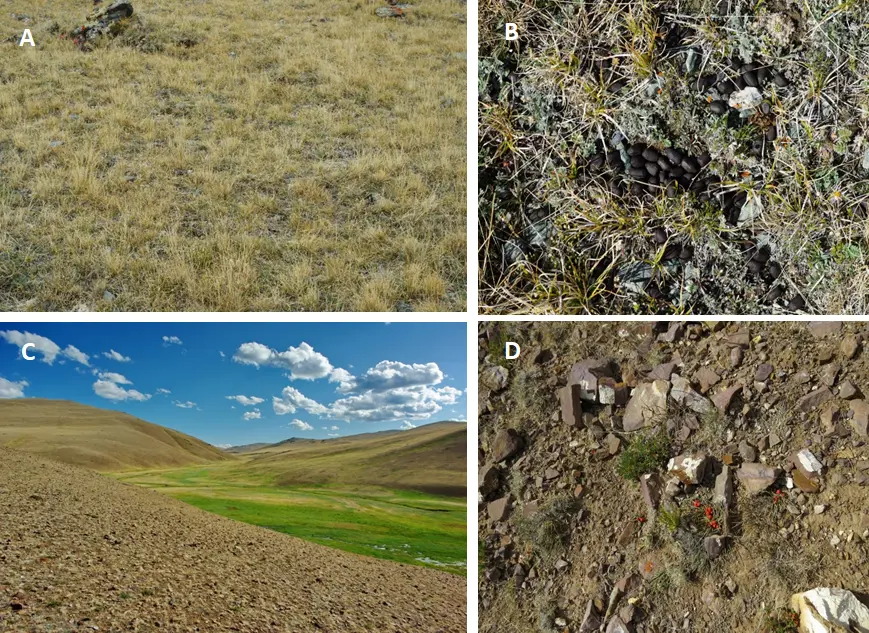

For individual species, projective cover was assessed as a percentage, which was converted to a point scale developed by the Braun-Blanquet school [11]: r—single specimen; +—projective cover less than 1%; 1—from 1 to 5%; 2a—from 6 to 12%; 2b—from 13 to 25%; 3—from 26 to 50%; 4—from 51 to 75%; 5—from 76 to 100%. We used the method of standard ecological scales of Ramensky [12] in the steppes dominated by Poa attenuata (Figure 4A,B) to analyze the phytocenosis environment for such specific factors as moisture, soil richness and salinity and pasture degradation Poa attenuata occupies approximately two-thirds of the plateau part of the Sailugem Ridge at altitudes of 2300 to 2600 m above sea level (sometimes such communities rise to 2700 m above sea level). This vegetation is the main available food for the largest argali population in Russia and livestock.

Figure 4. Vegetation of the Sailugem Ridge. Photos by I. V. Volkov and I. I. Volkova, 2024, 2025. (A) Steppes dominated by Poa attenuata. (B) Argali dung in a steppe dominated by Poa botryoides and Poa attenuata (a grass with narrower leaves). (C) Vegetation dominated by sedges in the Ulandryk River valley (eastern part of the Sailugem Ridge). In the foreground are rocky steppes with degraded vegetation. (D) Vegetation of rocky steppes.

The basis for Ramensky’s ecological scales [12] is the ecological optimum of a species in relation to various environmental factors, based on the distribution of a plant species in natural conditions. The scale level is a relative indicator that can be used both as a measure of the intensity of an environmental factor and as a measure of the ecological amplitude of a plant species.

The moisture conditions and soil characteristics of the steppes dominated by Poa attenuata, in the western, more humid part of the Sailugem Ridge, were assessed from bioindication characteristics. These were obtained by processing geobotanical descriptions in the IBIS 7.1 program [13] using the ecological scales of moisture, soil richness/salinity [14], and pasture degradation scale [15] (Figure 5).

The level of each listed factor is accounted for in scale steps that together form a standard factor scale. Average values, taking into account the projective cover of species, were calculated in the program and are shown as a line of minimum conflict. This represents the average value (habitat status), which can be considered a complex indicator-value characteristic of this description, obtained by averaging the ranges of ecological optimums of plants. The minimum conflict line has been used to determine the anthropogenic transformation coefficient (ATC). ATC is calculated (Equation (1)) as the number of synanthropic species as a percentage of the total set of species in the phytocenosis, taking into account the projective cover of species [13].

KAT—anthropogenic transformation coefficient;

ai—projective cover of synanthropic species;

bi—projective cover of hemerophobic species (those that cannot tolerate anthropogenic transformation);

Na—number of synanthropic species;

Nb—number of hemerophobic species.

To validate the calculated KAT results, a visual assessment of pasture degradation (plant cover) was made using a four-point scale recommended by the All-Russian Research Institute of Agriculture and Soil Protection from Erosion: 1—not degraded, 2—slightly degraded, 3—moderately degraded, 4—very heavily degraded pastures [16].

To up-date previous research results, the 2025 field season’s data were used. The new data is from the eastern part of the Sailugem Ridge. And made it possible to refine the scenario of vegetation change caused by climate change [4].

Based on: (a) an analysis of retrospective and future climate change data [17,18] (Figure 3), and associated inferred vegetation transformations, and (b) an analysis of the historical range of argali in the Altai Republic and the reasons for its decline, we propose a comprehensive conservation strategy by introducing argali into protected areas where this species is currently absent, but lived until the early 19th century.

3. Results

The biomass of argali forage varied by almost threefold between key sites, reaching up to 3100 kg/ha. The composite ecological gradient profiles of the steppes dominated by Poa attenuata in the Sailugem Ridge show that, for the moisture scale [KR_UV], there are 120 gradations with 18 original taxa of which 17 are included in the profile (Figure 5A). The line of minimal conflict for the moisture scale is 52.5. The number of gradations for the soil richness and salinity scale [KR_BZ] is 30, with 18 original taxa of which 17 are included in the profile. The average description status (Figure 5B) is 12.5, and the line of minimal conflict is 12.0. The pasture degradation scale [YA_PD] has 10 gradations for 18 original taxa, of which 11 are included in the profile. Sorting: By minimum, by optimum, by maximum. The average description status (Figure 5C) is 3.7, and the line of minimum conflict is 3.6. The stage of pasture degradation according to Cherosov’s gradient was 2.8 (closer to the moderately overgrazed). Our visual assessment yielded a close value of 2.5 (Figure 6).

Vertical lines are the lines of minimum conflict. There can be more than one line of minimum conflict depending on the landscape type. Horizontal lines denote the scale steps. Boxes denote the ecological optimum of a particular species.

Figure 6. The vertical structure of the steppe is dominated by Poa attenuata and its transformation as a result of increased grazing pressure. (A) Community under low grazing pressure; (B) Community transformed as a result of increased grazing pressure (2.5 degradation stage on a four-point scale). 1—Poa attenuata, 2—Carex rupestris, 3—Aster alpinus, 4—Helictotrichon mongolicum, 5—Oxytropis macrosema, 6—Allium rubens, 7—Artemisia frigida, 8—Silene repens, 9—Festuca tschujensis.

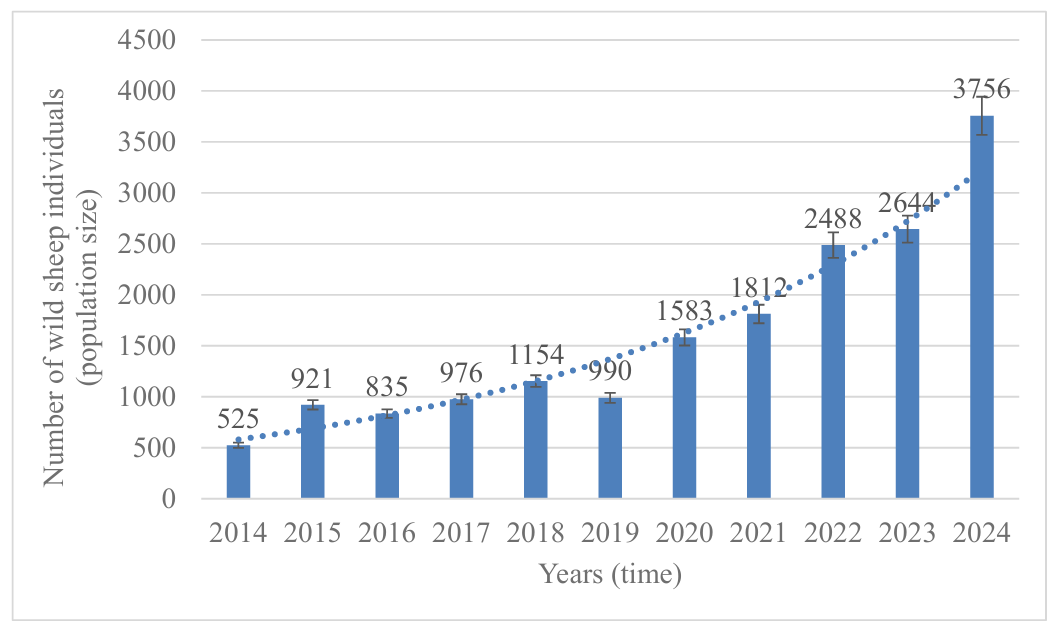

Data on the numbers of argali on the Sailugem Ridge (Figure 7), updated in this study, show a statistically significant exponential increase. The population increased from 525 individuals in 2014 to 3756 individuals in 2024. The argali population on the Russian part of the Sailugem Ridge is the most numerous group in Altai (3756 individuals in 2024) compared with 318 in neighboring Tuva, 2240 in the Mongolian part of the Sailugem Ridge, and 1664 in Uvs Aimag (Mongolia) [19]. Moreover, for the first time in a 10-year period of monitoring, the number of argali in the Russian part of Sailugem exceeded the number of argali in its Mongolian part [20]. If this exponential trend continues, far higher population figures can be expected in the coming years.

4. Discussion

4.1. Characteristics of the Pasture Vegetation—The Argali’s Food Source

In the composite ecological gradient profiles (Figure 5), moisture scale levels 1–17 correspond to desert-type moisture, while levels 110–120 correspond to aquatic vegetation habitats. The soil moisture index under the Poa attenuata-dominated phytocoenosis, at level 52.5, characterizes habitats intermediate between wet steppe (levels 47–52) and dry and fresh meadow (levels 53–63) (Figure 5A).

The term “active soil richness” refers to the degree to which plant nutrients are available in a mobile and plant-available form (soluble salts, bases adsorbed by colloids, easily mineralized nitrogen compounds, etc.). On the soil richness/salinity scale, steps 1–3 indicate particularly poor soils, while steps 29–30 indicate severely alkaline soils. Step 12 (the line of minimal conflict) (Figure 5B) characterizes soils of the Poa attenuata-dominated community in the western, plateau-like part of Sailugem Ridge, with steps (11–13) indicating relatively rich soils with a pH of 6.0–7.5 [14].

Our previous studies [4] have shown that steppes dominated by Poa attenuata, in the more humid western part of the Sailugem Ridge, have conditions of moisture that are optimal for this species, but with the some deficiency of nutrients available in the soil, which might prevent other potential competitors from succeeding (Figure 5B,C).

However, rainfall on the Sailugem Ridge can be unstable, and the moisture regime can fluctuate significantly (Figure 3). Our personal observations of shoot development of Poa attenuata, in the summer of 2022, revealed two distinct generations of young shoots. The first sub-layer of grass tufts, 20 cm tall, consisted of dried shoots, the growth of which was associated with the use of moisture reserves in the soil by plants remaining after the melting of the winter snow cover and was interrupted by an extremely dry spring. As a result of rainfall in early summer, a second generation of shoots emerged, reaching a height of 17 cm by August. The two periods of growth within a season of Poa attenuate suggest that these steppes in the mountains of Southern Siberia may be highly dependent on the rhythm of precipitation. In more humid, low-lying areas where snow accumulates, steppe productivity can increase by almost threefold (up to 3100 kg/ha). In such habitats, the ecologically vicarious species Poa botryoides (Figure 4B) usually co-dominates with Poa attenuata and even predominates. Such habitats are found in the western part of the Sailugem Ridge, where they occupy relatively small areas. This is due to the transport of snow by westerly winds, which reduces the soil moisture deficit for vegetation and likely, to some extent, offsets the periodic soil moisture deficits caused by thin air, strong solar radiation, and frequent winds typical of high mountains.

An important factor influencing steppe productivity is the level of pasture degradation. Pasture degradation is a gradual change in plant communities through excessive grazing pressure (although increasing aridization can also cause pasture degradation). Although steppes are communities that develop under the influence of herbivores, they degrade under excessive grazing pressure. The level of pasture degradation assessed using the IBIS 7.1 programme [13] and shown on Figure 5C as closer to moderately overgrazed according to [16].

Although Cherosov’s gradient scale was not developed for steppe ecosystems, there was a close agreement with the visual assessment according to the four-point scale for determining the stage of pasture degradation [16].

Overall, areas of relatively well-preserved steppe grassland typically alternate with more degraded areas. With further increases in grazing pressure, the importance of grasses may decline, and the community may transform into Artemisia frigida-dominated steppes (with isolated grass tussocks)—less valuable pastures that indicate the third stage of pasture degradation (Figure 6).

In general, the steppe vegetation, which occupies the largest area on the Sailugem Ridge, is in relatively good condition [4]. The best-preserved pastures are found in the western part of the Sailugem Ridge. Here, steppes dominated by Poa attenuata and Poa botryoides are predominantly in the first stage of pasture degradation, and no more than 20% of the steppe area is in the second stage of pasture degradation according to expert assessment. Good moisture is confirmed by fragments of meadow vegetation that develop among the steppes in more humid habitats.

More severe pasture degradation is observed in the Ulandryk River basin in the eastern part of the Sailugem Range. Here, we estimate that approximately half of the steppe area is in the second stage of pasture degradation, and approximately 7–10% is in the third stage. The steppes of the plateaus between the central parts of the Sailugem Range are in a similar state.

During our research in 2025 in the upper Ulandryk River valley (eastern part of the Sailugem Ridge), we found degraded rocky steppes on the river valley slopes (Figure 4C,D). Long-term overgrazing in the steppes not only degrades vegetation but also destroys the fertile humus horizon. The mechanism behind this transformation is linked to livestock grazing on grasses, which not only form but also, through their fibrous root systems, maintain the soil’s humus horizon. As a result of grazing, plants with taproot systems become dominant in communities with sparse vegetation. These taproots, while to some extent resistant to slope processes, do not protect the humus horizon, which is subject to mechanical destruction by animal hooves, blown away by winds, and washed away by rain, exposing the underlying rock (Figure 4D).

The presence of rocky steppes, as a stage of irreversible transformation of steppe vegetation under overgrazing conditions, downgrades the overall pasture condition in the south-eastern Sailugem Ridge from good to satisfactory. Unfortunately, if current grazing pressure continues under current temperature increases (Figure 3) [8,17] and future climate aridization [18], a significant part of mountain-steppe pastures will transform into rocky steppes, a process of desertification.

4.2. Argali Population Trends

Recently, the steppes’ forage resources (quality and amount) ensured the growth of the argali group on the Russian part of the Sailugem Ridge from 525 individuals in 2014 to 3756 individuals in 2024 (Figure 6).

Thus, food supply for argali is not the reason for the decline in its numbers in the Russian Federation in the 1990s and the beginning of the 21st century: the cause was illegal hunting [4].

The establishment of the Sailugem National Park in 2013 was an adequate and timely measure for the conservation of argali in the Russian Federation. Moreover, the argali population on the Russian part of the Sailugem Ridge is key to the conservation of this species in Russia, as it is the most numerous group in Altai.

This is particularly noticeable against the backdrop of a decline in the argali population on the Chikhachev Ridge, located northeast of Sailugem, which numbered 360 individuals in 2017 but has now dropped to 60 [6,24]. The argali in the Sailugem region is unable to establish a foothold in areas adjacent to Sailugem. For example, argali groups have been repeatedly observed on the South Chuya Ridge and on the Ukok Plateau (Figure 2B 2,3), as well as in other areas that were previously part of its habitat, but stable territorial groups have not yet been observed.

4.3. Current Argali Conservation Measures

The main factor for argali conservation is effective species protection. Argali protection should be strengthened on the Ukok Plateau and South Chuya Ridge [4]. However, a more important solution in the argali conservation strategy will be the creation of a new cluster (group of conserved areas) within the Sailugemsky National Park on the Chikhachev Ridge. The Sailugemsky National Park is a framework that could host this cluster and serve as a link between the argali populations on the Sailugem Ridge, the Altai Nature Reserve, and the Tuvan part of this species’ range. The National Park’s conservation regime does not interfere with the indigenous peoples’ traditional method of nature management—transhumance—but effectively limits illegal argali hunting. Furthermore, the inclusion of new territories within the National Park ensures their protection from seizure for other economic uses, such as mining, which could undermine not only the conservation of argali but also the traditional subsistence of local people.

On the other hand, as the distribution of argali in the historical period shows (Figure 2B, point 1), the potential range of this species covered not only the dry highlands of Altai (Sailugem Ridge), but also the more humid mountains of the western macroslope of the Katunsky Range. The Katunsky Nature Reserve provides the most effective protection of argali due to the strong ban on visiting this protected area for all categories of citizens, except for security guards and scientific staff.

4.4. Potential Impacts of Climate Change on Argali Conservation

Protection from people is not the only protection needed for argali conservation. Establishing the new protected clusters and/or reoccupying historical areas are especially relevant given the forecast for climate change-induced impacts on vegetation in the arid mountains where argali currently live. The productivity and food supply in sensory ecosystems such as the steppes are particularly sensitive to climate change [25]. Even a decrease of one degree of humidity in the western part of the Sailugem Ridge would remove the main dominant plant, Poa attenuata, from the zone of its ecological optimum (Figure 5A). We assume that in the drier eastern part of the Sailugem Ridge, this species is already nearing the limit of its ecological tolerance for moisture. With further climate aridization [18], this could lead to the replacement of species with less valuable forage.

These communities, under increased pressure from argali and livestock, will rapidly degrade, turning into unproductive rocky steppes. Moreover, such consequences will be more noticeable in the eastern, less humid part of the Ridge [4]. Some areas will soon experience irreversible desertification of pastures.

Retrospective analysis of vegetation changes and forecast of its future changes as a result of global warming show that climatic changes may strongly negatively affect the argali inhabited areas in the Sailugem Ridge by decreasing the state of their forage [4]. We assume that, according to the southern aspect of the Mongolian macroslope of the Sailugem Ridge, the area in Mongolia will likely experience more extensive changes in the next 10–15 years than the northern, Russian part. This will probably increase the pressure on argali’s pastures on the Russian (northern) macroslope of the Sailugem Ridge as they relocate. At the same time, climate-change induced impacts on steppe vegetation will lead to the expansion of the unproductive rocky steppes that will inevitably occur on the Russian part of the Sailugem Ridge. This scenario is amplified in the absence of livestock regulation and an increase in the argali population on the Sailugem Ridge at the same time. Thus, there are three processes here: an increase in the argali population due to protection from hunting and migration from the Mongolian side, increased competition with local herding, and a potential decrease in the habitat’s carrying capacity associated with climate aridization. Therefore, optimizing the pasture load by regulating the number of livestock will help to maintain the productivity of pastures and the economic feasibility of their use. Alternatively, it may lead to a decrease in livestock numbers. Argali’s impact on pasture degradation can possibly be reduced by improving the protection of this species in other areas of the South-Eastern Altai. For example, a new cluster of the Sailugemsky National Park on the Chikhachev Ridge can be created, and argali protection in the Ukok Plateau and South Chuya Ridge can be improved, including through the implementation of the planned South Chuya Nature Reserve. Due to local migration of this highly mobile wild sheep, their density will decrease as the population widens its distribution in the South-Eastern Altai. Moderation of global climate change impacts is not possible locally, so controlling local livestock numbers, hunting, and argali grazing areas are keys to conservation strategies.

4.5. Proposed New Argali Conservation Areas

We suggest that some areas in the southern part of the Altai Republic could be optimal for the reintroduction of argali. Reintroductions have been successfully and increasingly used over the past decades [26,27].

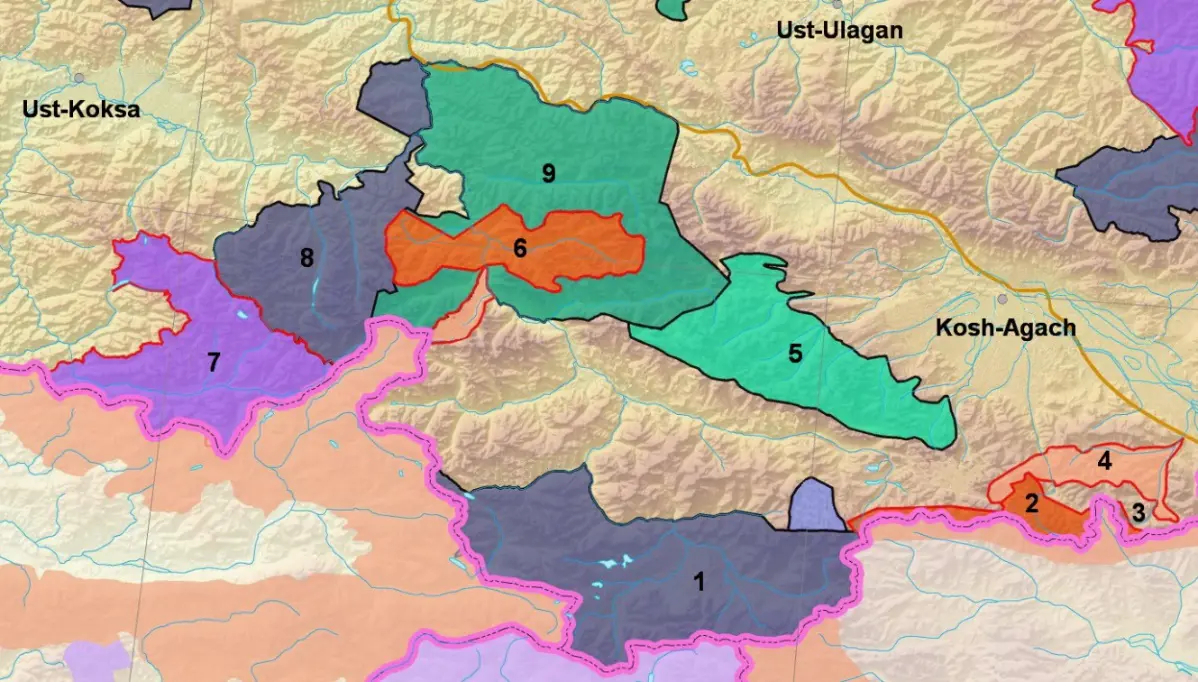

A map of Specially Protected Natural Areas (SPNA) of the Sailugem Ridge region (Figure 8) shows that almost all the area of the Ukok Plateau is designated as a regional protected area. The level of protection here is softer than on the federally protected areas (“national reserve”, “national park”) and is fundamentally determined by funding. The cluster of federally administered Sailugemsky National Park is located east of the Ukok Plateau. It has a stricter level of protection, but it covers less than a third of the Sailugem Ridge. However, as noted above, this is sufficient for a local increase in argali populations that exceeds more than six times over ten years. In comparison, as also noted above, on the Ukok Plateau (a regionally administered protected area), argali are unable to form a stable population. The planned South-Chuisky Nature Reserve (highlighted in light green on the map, Figure 8) could be an appropriate reserve, but due to anthropogenic impact, it is currently an impassible barrier to argali migration. Really effective protection for reintroduced argali populations can only be ensured within the Argut cluster of the Sailugemsky National Park and the Katunsky Nature Reserve, which maintain a permanent and sufficiently large security staff to ensure effective protection. Furthermore, the absolute prohibition of human access to the Katunsky Nature Reserve makes this area preferable for argali reintroduction.

Figure 8. Map of some existing and planned protected areas in the south of the Altai Republic: 1—Ukok Plateau Quiet Zone, 2—Sailugemsky National Park (Sailugem Cluster), 3—Sailugemsky National Park (Ulandryk Cluster), 4—Suggested Ulandryk Protected Zone, 5—Suggested South Chuysky Nature Reserve, 6—Sailugemsky National Park (Argut Cluster), 7—Katunsky Nature Reserve, 8—Belukha Nature Park, 9—Shavlinsky Nature Reserve. Pink lines denote international borders. Different terms (“Quiet zone”, “National Park”, “Protected Zone”, “National Reserve”) reflect the different protection regimes on these territories.

If a reintroduction is successful, these territories could serve as a nucleus for the creation of new argali populations in Altai, while surrounding areas with regional protected status, both existing and planned, could serve as a buffer zone. A natural prerequisite for the species’ survival even within the protected areas during winter is the presence of extensive surfaces from which snow cover is blown away, allowing argali to overwinter. The Sailugemsky National Park and the Katunsky Nature Reserve have such natural conditions. In the event of heavy snowfall during winter, additional feeding may be necessary for the argali’s survival. The Sailugemsky National Park and the Katunsky Nature Reserve have well-qualified staff and appropriate equipment. In the future, it will probably be relevant to reintroduce the argali to the territory of the Sayano-Shushensky Nature Reserve, the territory of which was included in the argali’s historical range according to petroglyphs depicting this species [28].

The reintroduction we are considering is similar to the conservation problem of other species with different habitats around the world. For example, Alpine ibex (Capra ibex ibex L.) suffered over-exploitation and poaching that led to a steady decline of ibex numbers in the European Alps. Today Alpine ibex management faces two challenges: (1) habitat destruction in areas of high population densities, and (2) low genetic variability, possibly a result of inbreeding during a succession of four potential population bottleneck situations [29]. Other examples are Eurasian lynx (Lynx lynx L.)[30] and Red kites (Milvus milvus L.) [31,32]. To protect and reintroduce these species, many efforts by various actors were necessary to overcome habitat destruction and biased, negative public opinion. We consider the positive results of these randomly chosen cases as support for our suggestions for argali species protection. Resettlement of argali in South-Eastern Altai, as well as reintroduction into their historical ranges, could mitigate potential survival problems of argali and will not cause obvious damage in the short-term to the ecosystems into which they will spread. The implementation of these ideas will probably become the most ambitious task in the strategy for the conservation of this species in Russia.

Acknowledgments

This study has partly carried out using research equipment of the Unique Research Installation “System of experimental bases located along the latitudinal gradient” TSU. The study is a contribution to the Siberian Environmental Change Network (SECNet) and the authors are grateful to SECNet partners for their cooperation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: T.V.C. and I.V.V.; methodology: I.V.V., I.I.V.; software: I.V.V., I.I.V.; validation, T.V.C., I.V.V.; formal analysis: T.V.C., I.V.V., O.M.S.; investigation: T.V.C., I.V.V., I.I.V., M.V.O. and O.M.S.; resources: I.V.V., O.M.S.; data curation: I.V.V., T.V.C.; writing—original draft preparation: I.V.V., I.I.V., M.V.O. and O.M.S.; writing—review and editing, T.V.C., I.V.V. and O.M.S.; visualization: I.V.V., I.I.V.; supervision: T.V.C.; project administration: I.V.V. and O.M.S.; funding acquisition: O.M.S. All the authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Ethics Statement

Ethics approval was not required for this study, as it used publicly available official statistical data and did not involve any clinical study or animal study.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Funding

This study did not get external financial support, it was supported by the Tomsk State University Program (“Priority-2030”), project No. RD 2.2.1.24 RG.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article and there is no conflict of interest between the academic funding organization and other interests.

References

-

Karnaukhov AS. Altai mountain sheep (argal) Ovis ammon ammon Linnaeus, 1776. In Red Book of the Russian Federation, 2nd ed.; Pavlov DS, Amirkhanov AM, Rozhnov VV, Ananieva NB, Belousova AV, Britaev TA, Eds.; Volume “Animals”; VNII Ecology: Moscow, Russia, 2021; 1128p, pp. 1039–1041. Available online: https://www.mnr.gov.ru/activity/red_book/krasnaya-kniga-rossiyskoy-federatsii/ (accesed on 25 June 2025). (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

-

Reading R, Michel S, Amgalanbaatar S. Ovis ammon. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2020: e.T15733A22146397. Available online: https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/15733/22146397 (accessed on 18 September 2025). [Google Scholar]

-

Ledebour CF. Reise Durch das Altai-Gebirge und die soongorische Kirgisen-Steppe: Auf Kosten der Kaiserlichen Universität Dorpat Unternommen im Jahre 1826 in Begleitung der Herren Carl Anton Meyer und Alexander von Bunge; Zweiter Theil; G Reimer: Berlin, Germany, 1830; pp. 1–228. [Google Scholar]

-

Callaghan TV, Volkova II, Volkov IV, Kuzhlekov AO, Gulyaev DI, Shaduyko OM. Changing Asian Mountain Steppes Require Better Conservation for Endangered Argali Sheep. Diversity 2024, 16, 570. doi:10.3390/d16090570. [Google Scholar]

-

Shelford VE. Basic principles on the classification of communities and habitats and the use of terms. Ecology 1932, 13, 105–120. doi:10.2307/1931062. [Google Scholar]

-

Spitsyn SV, Kuzhlekov AO, Gulyaev DI. Assessment of the quality and completeness of the autumn accounting of Altai mountain ram (argali) in the cross-border zone of Russia and Mongolia in 2024. Field Res. Altaisky Biosph. Reserve 2025, 7, 79—95. (In Russian, English Abstract) [Google Scholar]

-

Volkov IV, Volkova II. Scientific Report “Assessment of the Pasture Resources Potential in the Habitats of the Altai Mountain Sheep (Argali) in the Russian Part of the Sailugem Ridge (Russia, Altai Republic, Kosh-Agach District), Including on the Territory of the Sailugemsky National Park”; Tomsk State University: Tomsk, Russia, 2023; 105p. Available online: http://portal.tsu.ru/#/accaount/projects/all (accessed on 25 June 2025). [Google Scholar]

-

Sukhova MG, Zhuravleva OV. Dynamics of changes in air temperature and precipitation in the Chuya basin. News High. Educ. Institutions. North Cauc. Region. Nat. Sci. 2017, 1, 124–129. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

-

Volkova II, Callaghan TV, Volkov IV, Chernova NA, Volkova AI. South-Siberian mountain mires: Perspectives on a potentially vulnerable remote source of biodiversity. Ambio 2021, 50, 1975–1990. doi:10.1007/s13280-021-01596-w. [Google Scholar]

-

Moore GA, Sukhova MG. Climatic features of the territory of the “Sailugemsky” National park. In Nature Management and Sustainable Development of Russian Regions: Collection of Articles of the IV All-Russian Scientific and Practical Conference; Bayrakov IA, Lukshin IA, Eds.; Penza State Agrarian University: Penza, Russia, 2022; pp. 42–47, 105. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

-

Braun-Blanquet J. Pflanzensoziologie; Springer: Vienna, Austria, 1964. [Google Scholar]

-

Ramensky LG, Tsatsenkin IA, Chizhikova ON, Antipov NA. Ecological Assessment of Forage Lands Based on Vegetation Cover; Selkhozgiz Publ.: Moscow, Russia, 1956; p. 471. Available online: https://sinref.ru/000_uchebniki/04800selskoe/039_ekologicheskaia_ocenka_kormovih_ugodii_ramenski_1956/001.htm (accesed on 11 November 2025). (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

-

Zverev AA. Methodological Aspects of Using Indicator Values in Biodiversity Analysis. Contemp. Probl. Ecol. 2020, 13, 321–332. doi:10.1134/S1995425520040125. [Google Scholar]

-

Korolyuk AY. Ecological optimums of plants in southern Siberia. Bot. Stud. Sib. Kazakhstan 2006, 12, 3–28. (In Russian). Available online: https://www.elibrary.ru/download/elibrary_28113040_81979348.pdf (accessed on 21 August 2025) [Google Scholar]

-

Cherosov MM. Synanthropic Vegetation of Yakutia; Yakut Scientific Center of the Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences: Yakutsk, Russia, 2005; p. 156. (In Russian) Available online: https://www.elibrary.ru/item.asp?id=19495025 (accessed on accessed on 21 August 2025). [Google Scholar]

-

Robertus YV, Baylagasov LV, Tolbina ZB, Lyubimov RV, Ledyaeva NV, Manysheva TV. Status and Ways to Optimize Pasture Use on the Russian Territory of the Sailyugem Ridge (Altai Republic). Methodological Manual; Entrepreneur A. Orekhov: Gorno-Altaisk, Russia, 2011, p. 70. Available online: https://elibrary.ru/item.asp?id=19575728 (accesed on 23 October 2025). (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

-

Lipka ON. Climate Change Analysis and Projections for the Russian Part of the Altai-Sayan Ecoregion and Kazakhstan and Mongolia Frontiers; WWF-Russia: Moscow, Russia, 2018; p. 286. [Google Scholar]

-

Callaghan TV, Shaduyko O, Kirpotin SN, Gordov E. Siberian Environmental Change: Synthesis of Recent Studies and Opportunities for Networking. Ambio 2021, 50, 2104–2127. doi:10.1007/s13280-021-01626-7. [Google Scholar]

-

Media Service of the Federal State Budgetary Institution “Sailugemsky” National Park. Rare Altai Mountain Sheep Will Be Counted on the Russian-Mongolia Border. Available online: https://sailugem.ru/index.php/1389-na-granitse-rossii-i-mongolii-poschitayut-redkikh-altajskikh-gornykh-baranov (accessed on 14 October 2025). (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

-

Media Service of the Federal State Budgetary Institution “Sailugemsky” National Park. The Argali Population in Russia Has Outnumbered That of Neighboring Mongolia, Reaching over 4000 Individuals. Available online: https://sailugem.ru/index.php/1314-vpervye-za-istoriyu-10-letnego-monitoringa-argali-chislennost-vida-v-rossii-prevysila-chislennost-gruppirovki-v-sosednej-mongolii-i-sostavila-bolee-4-tysyach-osobej (accessed on 16 September 2025). (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

-

Spitsyn SV, Kuksin AN, Kuzhlekov AO, Gulyaev DI, Munkhtogtokh O, Sergelen E. The results of the autumn Altai argali census in the transboundary zone of Russia and Mongolia in 2021. Problems and prospects of population conservation. Field Res. Altaisky Biosph. Reserve 2022, 4, 77–97. (In Russian, English Abstract) [Google Scholar]

-

Spitsyn SV. Scientific Report “Results of the Autumn Census of the Altai Mountain Sheep in 2023 in the Transboundary Zone of Russia and Mongolia”; Altai State Biosphere Reserve: Gorno-Altaisk, Russia, 2023; p. 29. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

-

Malikov DG, Spitsin SV. To the study of distribution, abundance and age and gender composition of the altai mountain sheep Ovis ammon ammon (L.) in Sailugemsky National Park and adjacent areas. Proc. Tigirek Nat. Reserve 2015, 7, 280–281 (In Russian, English Abstract) [Google Scholar]

-

Spitsyn SV, Kuzhlekov AO, Gulyaev DI. Results of the autumn accounting of the Altai mountain sheep (argali) in the cross-border zone of Russia and Mongolia in 2023. Field Res. Altaisky Biosph. Reserve 2024, 6, 108–123. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

-

Lisetskii FN. Interannual variation in productivity of steppe pastures as related to climatic changes. Russ. J. Ecol. 2007, 38, 311–316. doi:10.1134/S1067413607050037. [Google Scholar]

-

Thévenin C, Morin A, Kerbiriou C, Sarrazin F, Robert A. Heterogeneity in the allocation of reintroduction efforts among terrestrial mammals in Europe. Biol. Conserv. 2020, 241, 108346. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2019.108346. [Google Scholar]

-

Forbes E, Alagona PS, Adams AJ, Anderson SE, Brown KC, Colby J, et al. Analogies for a No-Analog World: Tackling Uncertainties in Reintroduction Planning. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2020, 35, 551–554. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2020.04.005. [Google Scholar]

-

Miklashevich EA. New Rock Art Site at the Riverside Cliff s in the Oglakhty Mountains (Khakasia). Theory Pract. Archaeol. Res. 2022, 34, 39–53. doi:10.14258/tpai(2022)34(3).-03. [Google Scholar]

-

Stüwe M, Nievergelt B. Recovery of alpine ibex from near extinction: The result of effective protection, captive breeding, and reintroductions. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1991, 29, 379–387. doi:10.1016/0168-1591(91)90262-V. [Google Scholar]

-

Pearson M, Carpenter AI. Perceptions and Opinions Regarding the Reintroduction of Eurasian Lynx to England: A Preliminary Study. Conservation 2025, 5, 23. doi.10.3390/conservation5020023. [Google Scholar]

-

Murn C, Hunt S. An assessment of two methods used to release Red Kites (Milvus milvus). Avian Biol. Res. 2008, 1, 53–57. doi:10.3184/175815508X360452. [Google Scholar]

-

Carter I, Grice P. The Red Kite Reintroduction Programme in England; English Nature Research Reports 2002; Natural England: London, UK, 2002; pp. 4–63. [Google Scholar]