Synthesis, Spectroscopic Characterization Techniques, and Functional Applications of Selenium Heterocycles

Received: 20 October 2025 Revised: 14 November 2025 Accepted: 08 December 2025 Published: 15 December 2025

© 2025 The authors. This is an open access article under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

1. Introduction

1.1. From Synthesis to Application: Research on Selenium-Containing Heterocyclic Compounds

Although the human body contains approximately 105 times more sulfur than selenium, organisms have evolved to use selenium for specialized functions [1,2], and this selective utilization stems from selenium’s unique chemical properties. Despite selenium’s atomic mass being approximately twice that of sulfur, their atomic radii are strikingly similar due to the d-block contraction effect, wherein the shielding effect of d-orbitals on the atomic nucleus is weaker, which increases the effective nuclear charge and causes the electron cloud to be closer to the nucleus [3]. This characteristic is also reflected in the bond lengths of the main-group compounds they form. However, these two elements exhibit significant differences in their chemical behavior.

In reviews, Chem. Heterocycl. Compd. (2019) [4], including synthetic methods [5], catalytic applications, photophysical properties, and self-assembly [6,7,8,9]. Additionally, researchers compared the characteristics of selenium and sulfur heterocyclic compounds [10,11,12] and their analysis revealed three key features of selenium atoms: relatively low electronegativity (2.55 compared to sulfur’s 2.58), stronger polarizability, and unique bond energy parameters, which contribute to selenium’s unique chemical reactivity. Selenium (Se) has an electronegativity of 2.55, while sulfur (S) has an electronegativity of 2.58, indicating that selenium’s electronegativity is slightly lower than sulfur’s, which makes selenium atoms more easily polarized [10]. Specifically, selenium exhibits several notable characteristics. First, the covalent bonds formed by selenium are weaker than those formed by sulfur (the C–Se bond energy is 247 kJ/mol, while the C–S bond energy is 272 kJ/mol) [3,11]. Second, selenium is more prone to oxidation [3,12,13]. Third, selenium alcohols are 3–4 orders of magnitude more acidic than corresponding sulfur alcohols [10]. The high polarizability and adjustable redox properties of selenium modulate intermolecular charge transfer, enhance spin–orbit coupling, and enable selective thioredoxin reductase inhibition. While these differences may seem minor, they amplify in chemical reactions. These unique chemical properties confer a special status to selenium heterocyclic compounds in organic synthesis and functional material design.

The synthetic accessibility of selenium heterocycles directly determines their structural diversity, which in turn governs their optoelectronic and biological functions. These fundamental properties of selenium directly translate into a wide range of tunable material characteristics, rendering selenium heterocycles a versatile platform for designing advanced functional materials. The influence of these molecules on intramolecular charge transfer, participation in noncovalent interactions, and capacity for diverse redox chemistry is being leveraged across various technological domains.

Among the most promising applications, two fields have been identified as being of particular promise: sustainable energy and biomedicine. In the context of sustainable energy, the exploration of high-performance organic electronic materials has led to a significant focus on selenium-containing heterocycles. The integration of these elements into conjugated systems has been demonstrated to effectively narrow bandgaps and enhance charge transport, thereby directly addressing efficiency bottlenecks in devices such as organic photovoltaics (OPVs) [14]. Concurrently, within the domain of biomedicine, selenium’s biological activity, particularly its targeting of enzymes such as thioredoxin reductase (TrxR), provides a foundation for the development of novel anti-cancer and antimicrobial strategies [1]. This dual significance, which lies in the bridging of advanced energy materials and innovative therapies, underscores the interdisciplinary importance of selenium heterocycles.

This review aims to comprehensively outline the journey of selenium heterocycles from fundamental synthesis to cutting-edge applications. Firstly, explore synthetic approaches, emphasising how emerging photoredox and electrochemical strategies adhere to the principles of green chemistry [15,16,17]. The review then explores advanced spectroscopic techniques, which are essential for grasping the structure-property relationships that underpin these applications [3,18]. This paper focuses on functional applications, critically examining their impact in optoelectronics and biomedicine. Finally, the article concludes with a forward-looking perspective on how the convergence of ideas accelerates the development of next-generation selenium-based materials. The core of this article is devoted to functional applications, where we will critically examine their impact in the domains of optoelectronics and biomedicine. Finally, the article discusses how cross-disciplinary integration of ideas accelerates the development of next-generation selenium-based materials, concluding with a forward-looking perspective.

1.2. Evolutionary Trends in the Field of Selenium Heterocycles

Research on selenium-containing heterocycles has undergone a marked transformation over the past two decades, driven by increasing demands for environmentally friendly synthesis, precise structure–property correlation, and application-oriented molecular engineering. Several distinct evolutionary trends have shaped the development of this field. The synthetic methodologies began with foundational work that established the characteristic reactivity and preparative routes to selenophenes and related frameworks [19]. The emergence of ligand-engineered palladium catalysis in the 1990s, exemplified by the Buchwald–Hartwig family of developments, subsequently opened broadly modular strategies for constructing C-heteroatom bonds and greatly expanded the accessible selenium-containing scaffolds [20]. More recently, the synthetic methodologies have shifted from classical nucleophilic and transition-metal-catalyzed approaches toward greener, more modular platforms, including photocatalytic, electrochemical, and metal-free strategies that provide enhanced selectivity and sustainability. Light-driven selenylation and electrochemical methods have revitalized synthetic practice by enabling milder, more sustainable pathways to selenium heterocycles and by facilitating radical and ionic modes of bond formation that were previously difficult to access [21,22]. These methods enable milder reaction conditions, improved substrate compatibility, and expanded structural diversity.

Parallel to these methodological advances, advances in spectroscopic and theoretical tools have significantly deepened molecular-level understanding, and a growing body of application-directed research has clarified the functional value of selenium heterocycles in areas such as organic optoelectronics and redox-active medicinal chemistry. In optoelectronics, selenium-containing π-conjugated systems have been tailored to achieve enhanced charge transport and broadened absorption profiles, enabling organic photovoltaic devices (OPVs) with power conversion efficiencies surpassing 15%. In chemical biology, selenium heterocycles are increasingly explored as redox-active pharmacophores for thioredoxin reductase (TrxR) inhibition, antibacterial activity, and controlled ROS modulation. These researches underscore the dual impact of selenium chemistry on both molecular design and device/biological applications [23].

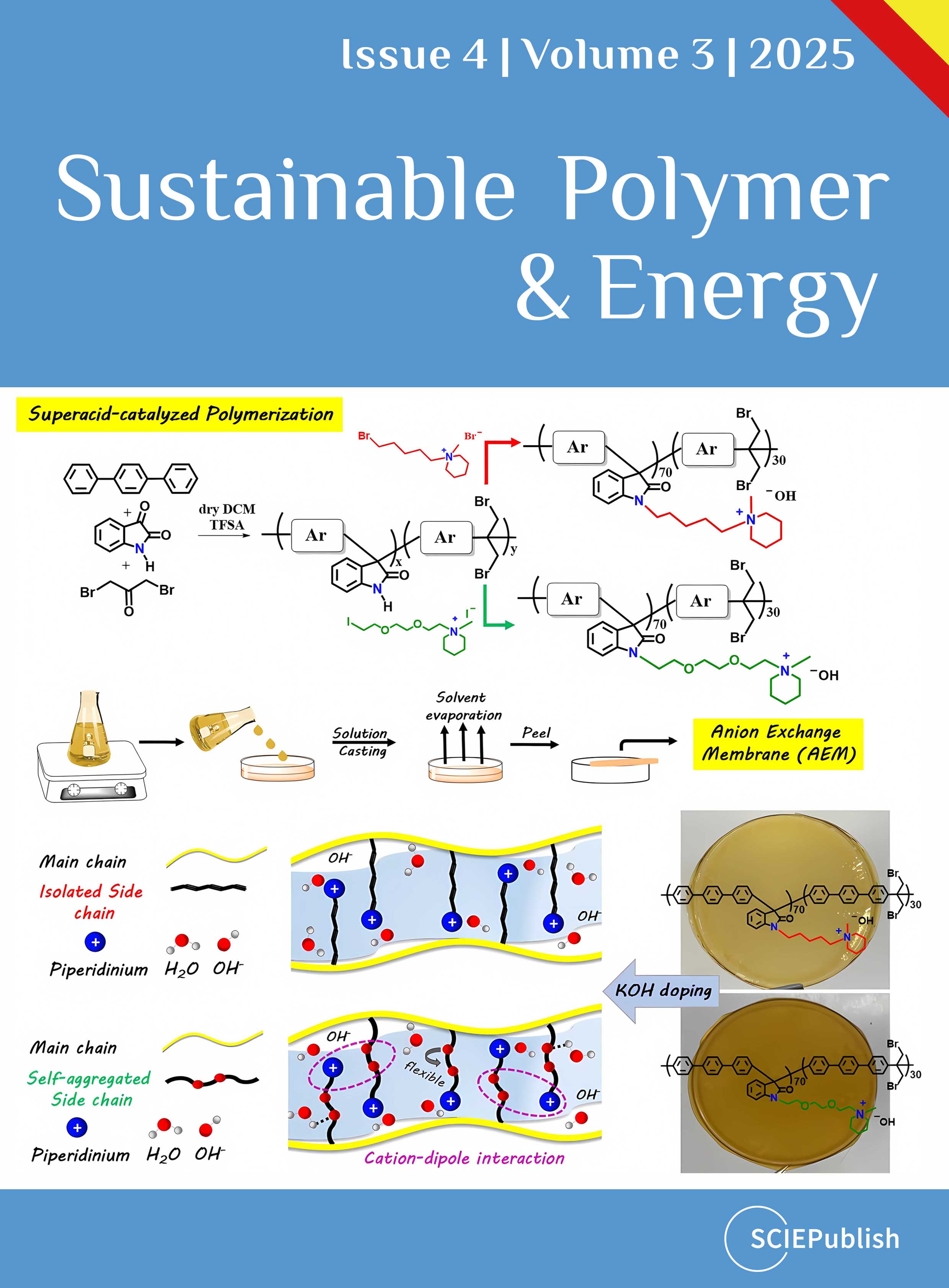

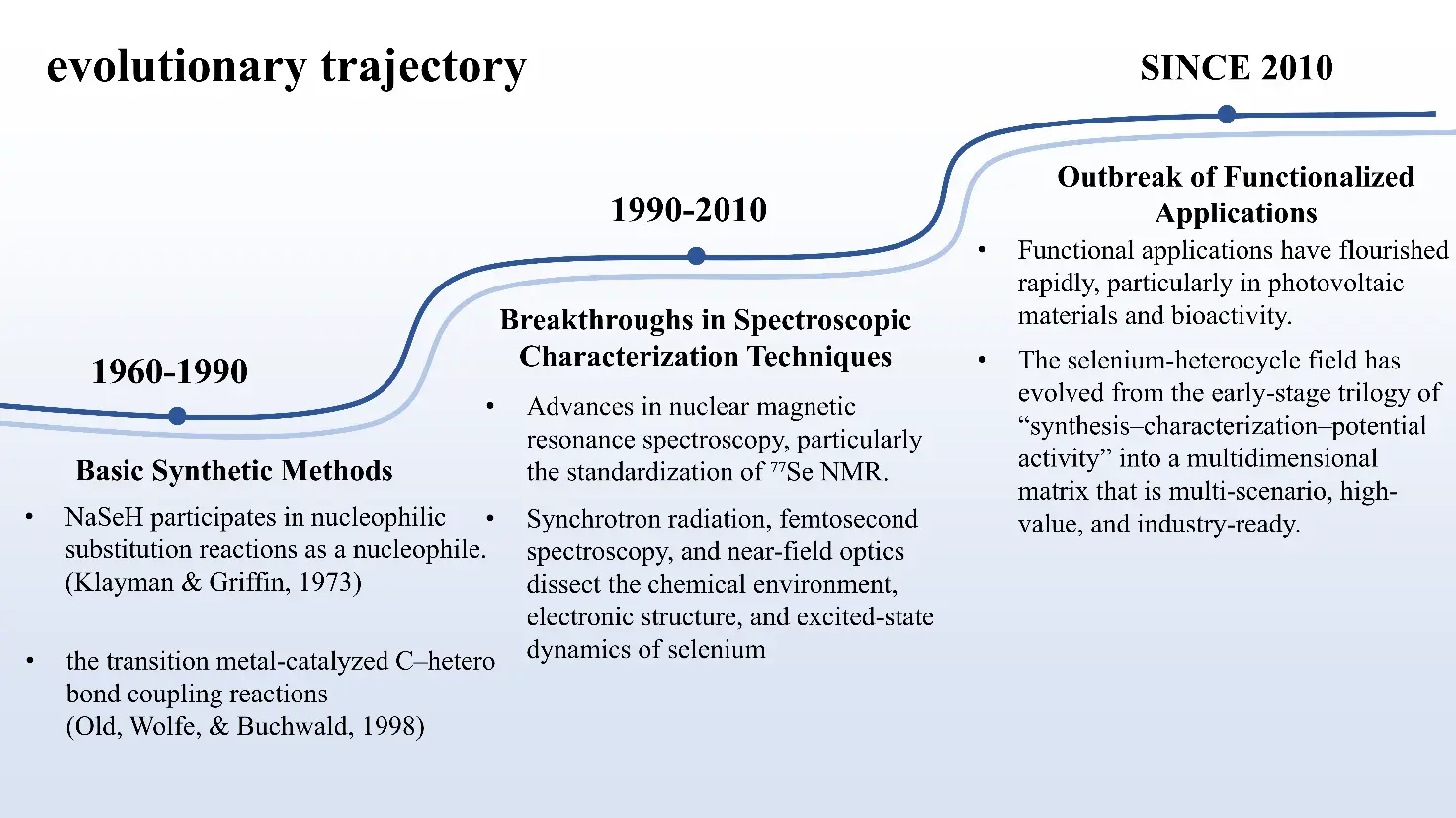

The principal milestones referenced above are summarized chronologically in Figure 1. These evolutionary trends establish the foundation for the organizational structure of this review. Section 2 focuses on synthetic methodologies, Section 3 discusses spectroscopic characterization techniques, and Section 4 highlights functional applications, illustrating how advances across these areas jointly drive progress in selenium heterocycle research.

Figure 1. Evolutionary trends in the field of selenium heterocycles. During the period from the 1960s to the 1980s, the nucleophilic cyclization of NaSeH (Klayman & Griffin, 1973) [24] and the transition metal-catalyzed C–hetero bond coupling reactions (Old, Wolfe, & Buchwald, 1998) [25] were developed, forming the basis of the “classic methods”.

2. Synthesis Methodology

The synthesis of selenium-containing heterocycles has transitioned from classical nucleophilic substitutions to highly tunable catalytic and redox-driven methodologies. Early routes established reliable access to C–Se frameworks, but the demand for stereocontrol, site-selectivity, and sustainability has stimulated development of transition-metal catalysis, photocatalysis, and electrochemical strategies. Collectively, these methods enable the generation of reactive selenium species in increasingly mild, programmable reaction environments, providing a scalable toolbox for constructing diverse selenacycles.

2.1. Synthesis Mechanisms of Selenium Heterocycles

The mechanistic landscape of selenium-heterocycle construction has evolved into a multi-pathway system, in which C–Se bond formation can proceed through nucleophilic displacement, electrophilic activation, radical relay, or transition-metal-mediated coupling. These four fundamental reaction modes differ in their electronic control elements: ionic polarity, π-activation, single-electron transfer, or redox cycling, yet collectively constitute the conceptual backbone of selenium synthetic chemistry. Classical nucleophilic substitution provides direct and reliable access to Se-centred scaffolds, electrophilic cyclization enables rapid π-framework reorganization, radical selenylation introduces annulation selectivity beyond polar control, while metal catalysis grants tunable reactivity, high efficiency, and stereochemical precision. Understanding how these mechanistic channels generate, transform, and confine reactive selenium intermediates is essential for directing molecular architecture, unlocking new reactivity space, and designing next-generation selenium heterocycles with enhanced structural complexity.

2.1.1. Divergent Mechanisms for C–Se Bond Formation

Among the various selenylation strategies, different research groups have explored multiple reaction mechanisms. From nucleophilic addition and electrophilic ring-alkylation to radical cyclization, thereby expanding the synthetic methodologies for selenium-containing heterocycles through diverse pathways.

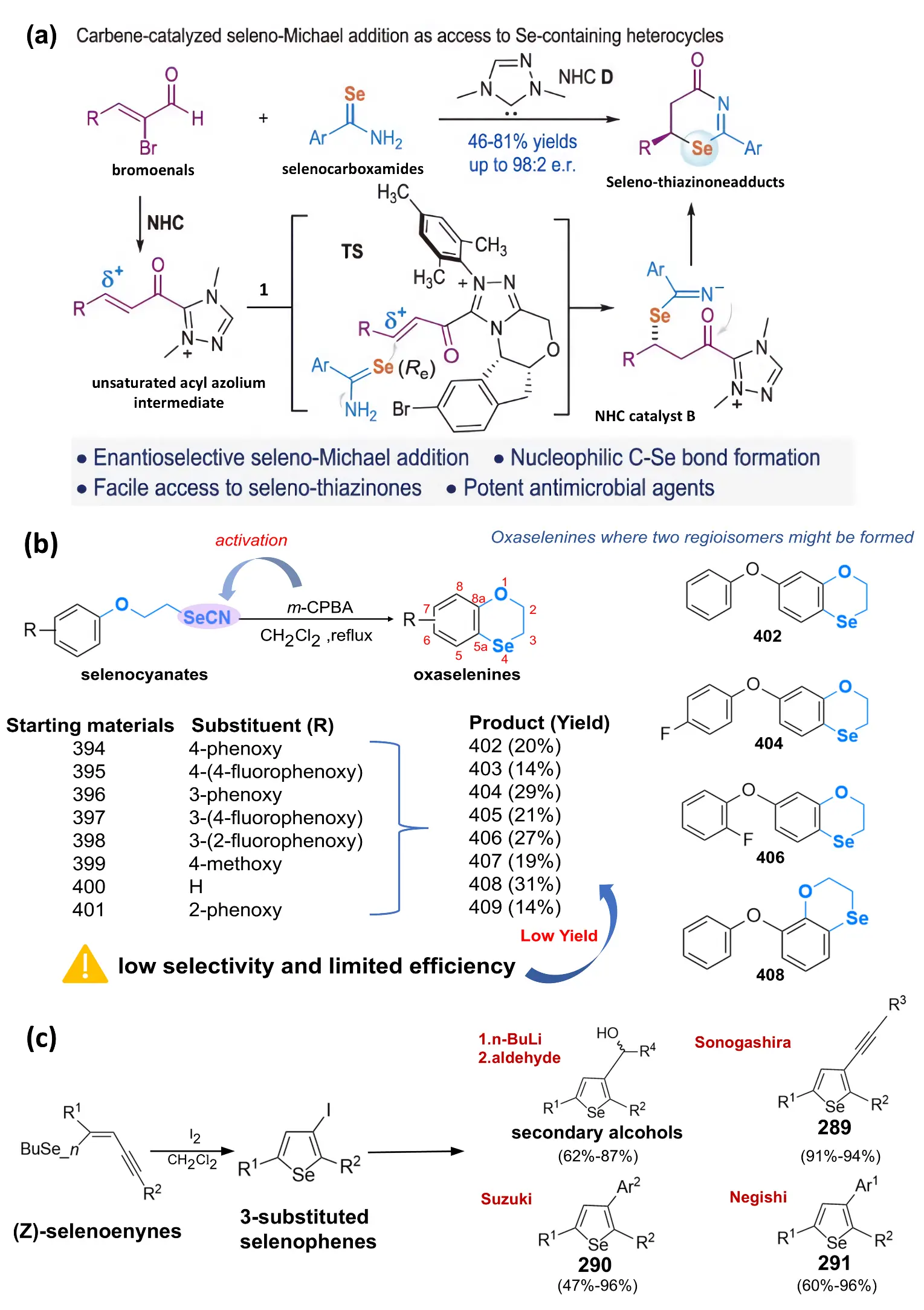

Although classical SN2-type nucleophilic selenylation remains one of the most fundamental strategies for C–Se bond formation, typically involving the direct attack of selenolate anions on alkyl electrophiles, this approach generally lacks stereocontrol. It is often limited to relatively simple linear substrates. The absence of a chiral environment within the substitution pathway means that enantioenriched selenium frameworks are difficult to obtain through such routes, highlighting an urgent need for catalyst-governed stereoselective systems capable of addressing the limitations of traditional nucleophilic substitution. Against this backdrop, organic selenium chemistry has advanced substantially. While many non-enantioselective C–Se bond formation transformations have been developed, significant challenges remain in the catalyst-controlled, stereoselective preparation of chiral organic selenium. Long et al. (2024) [26] reported a method for highly enantioselectively constructing C–Se bonds using N-heterocyclic carbenes (NHC) catalysis, which achieves highly enantioselective selenium-containing Michael addition reactions between selenamide derivatives as nucleophiles and LUMO-activated α,β-unsaturated acyl azide intermediates with good selenothiazine product yields and excellent optical purity. In Figure 2a, an N-heterocyclic carbene (NHC) catalyst enables a formal [3+3] cyclization between bromoenal (substrate 1) and selenoformamide (substrate 2), in which a C–Se bond is constructed via a selenium-Michael addition. This transformation affords selenothiazinone products (3) with good yields, excellent enantioselectivity, and notable antibacterial activity. The unsaturated acylazolium intermediate (A) plays a key role in controlling stereoselectivity. In addition, the reaction performance was optimized by screening catalysts—including NHC B—and weak inorganic bases. Overall, this stereocontrol arises from the conformational rigidity of the NHC-bound unsaturated acylazolium intermediate, which enforces a chiral environment around the Michael acceptor. Such mechanistic features explain the consistently high Enantiomeric Excess (ee) values observed across substrates and highlight an advantage of carbene catalysis over classical SN2-type selenylation, which rarely affords stereochemical control. This method offers a new approach to rapidly preparing chiral, selenium-containing heterocyclic frameworks with high enantioselectivity, and the resulting heterocyclic products exhibit significant antibacterial activity. This work represents a typical “catalytic nucleophilic-addition” selenylation pathway, in which stereoselective construction is achieved by precisely controlling the match between the nucleophilic selenium species and the electrophilic alkene system.

In addition, electrophilic ring-alkylation mechanisms further expand the construction of selenium-containing heterocycles from a third mechanistic dimension. Godoi et al. (2011) [27] pioneered a novel method for synthesizing heterocyclic compounds through the electrophilic cyclization reaction of alkyne, encompassing the synthesis of selenium heterocycles. The introduction of selenium groups into organic substrates can be achieved through the use of nucleophilic and electrophilic reagents. Following introduction into organic substrates, the removal of organic selenium groups can be facilitated through selenium oxide synthesis elimination and [2,3]-trans-rearrangement. Furthermore, subsequent palladium-catalyzed coupling reactions (e.g., the Sonogashira, Suzuki and Negish reaction) can further modify the iodine or other functional groups in selenium heterocycles (Figure 2c), thereby enabling the construction of more complex molecular structures. This approach emphasizes a dual strategy of “framework construction + functionalization”, achieved through electrophilic cyclization followed by late-stage coupling. Unlike nucleophilic and radical modes, electrophilic cyclization allows direct activation of unsaturated motifs and often proceeds under mild conditions, thereby enabling rapid assembly of polycyclic architectures that are challenging to access through classical substitution pathways. It offers clear mechanistic complementarity to the nucleophilic and radical pathways described above.

Figure 2. (a) Carbenium-catalyzed formation of highly enantioselective nucleophilic C–Se bonds via a formal [3+3] cycloaddition between selenamide 2 and bromoethene 1; Number 1 in the diagram refers to selenocarboxamides. Reproduced with permission of Ref. [26], Copyright © 2024, Science China Press. (b) The selenocyclization reaction of selenocyanate substrates is carried out using mesityl perbenzoic acid in refluxing dichloromethane. In the figure, the numbering (1–8, 5a, 8a) serves to precisely describe the structural positions of the heterocycle, facilitating subsequent discussions of substituent modification and reaction sites. (c) Converting 3-substituted selenophenes into Sonogashira (289), Suzuki (290), and Negishi (291) type products.

In contrast, a completely different mechanism—radical-driven selenylation—offers an alternative strategy for constructing selenium-containing heterocycles. The cyclization reaction of selenocyanate derivatives on activated aromatic rings has been studied. Although radical selenylation remains comparatively less explored mechanistically, recent studies indicate that controlled single-electron pathways exhibit unique selectivity patterns distinct from those of polar nucleophilic reactions. Sonego et al. (2023) [23] treated selenocyanate esters 394–401 with dichloroperoxybenzoic acid (a typical oxidising agent) in dichloromethane, yielding 2,3-dihydrobenzo[b][1,4]oxaselenolines 402–409 with excellent regioselectivity (Figure 2b) [28,29]. The regioselectivity is largely governed by intramolecular radical capture at electronically biased positions of the aromatic ring, highlighting the potential for predictable radical-induced heterocycle formation. This cyclization mechanism involves free radical species, which begins with a one-electron transfer process between the model compound selenocyanate 399 and p-chlorobenzoic acid, generating free radical ion A. Next, the Se–CN bond is cleaved, and cyclization occurs synergistically. Finally, oxaselenine 399 forms through proton extraction by an accompanying base. Such reactions rely on a radical chain process to accomplish both selenium incorporation and ring closure, representing a selenylation mode governed by electron-transfer control rather than nucleophilic/electrophilic control, in clear contrast to nucleophilic catalytic systems.

Finally, in the area of classical nucleophilic selenide reactions, the work by Penteado et al. (2020) [17] provides an important example of greener and more generalizable strategies. They investigated a nucleophilic selenylation approach in which diselenides are converted in situ into selenolates under NaBH4/PEG-400 conditions. Through systematic evaluation of the reactivity of these selenolates, they found that this green system efficiently promotes SN2 nucleophilic substitution of alkyl halides and can further construct various selenium-containing heterocycles and chiral selenoethers. This method not only features mild conditions, environmental friendliness, and broad substrate compatibility but also demonstrates the potential of nucleophilic selenylation in stereoselective synthesis. Unlike the catalytic nucleophilic addition developed by Long et al., Penteado’s system does not rely on a catalyst; instead, it utilizes the strong in situ–generated nucleophile Se− to accomplish simple and efficient SN2-type selenylation, highlighting another important advancement toward “atom economy and green chemistry” in selenylation reactions. Meanwhile, Wirth and other researchers, focusing on the reactivity of isoselenocyanates, developed selenylation strategies utilizing nucleophilic selenium sources such as NaHSe, NaSeH, and NaBH4/Ph2Se2 [30]. They discovered that the C=N=C=Se fragment of isoselenocyanates is highly electrophilic and can undergo sequential addition, selenium migration, and intramolecular cyclization with selenide anions, thereby efficiently constructing structurally diverse selenium heterocycles such as selenazines, selenazolidines, and selenazoles. This system represents a typical nucleophilic selenylation mode driven by a “highly electrophilic C=N=C=Se fragment”. Compared with classicall SN2-type selenylation, its reaction pathway relies more heavily on the intrinsic electronic properties of the substrates and internal migration processes, emphasizing structure-induced multistep addition and cyclization, and thus enabling the construction of more complex heterocyclic frameworks. The PEG-400 medium not only enables safer handling of selenium reagents but also enhances nucleophile solvation, providing a mechanistic explanation for its broad substrate compatibility. Compared with catalyst-controlled asymmetric systems, this protocol emphasizes operational simplicity and sustainability, thereby complementing the more structurally complex catalytic nucleophilic additions.

These studies, grounded in four fundamentally distinct reaction mechanisms—catalytic nucleophilic addition, electrophilic ring-alkylation, radical cyclization, and SN2 reactions driven by strongly nucleophilic Se−. They have promoted progress in stereoselective construction, structural diversification, heterocycle formation, and green synthesis, thereby laying a solid foundation for the future design and application of selenium-containing functional molecules.

2.1.2. Transition Metal Catalysis

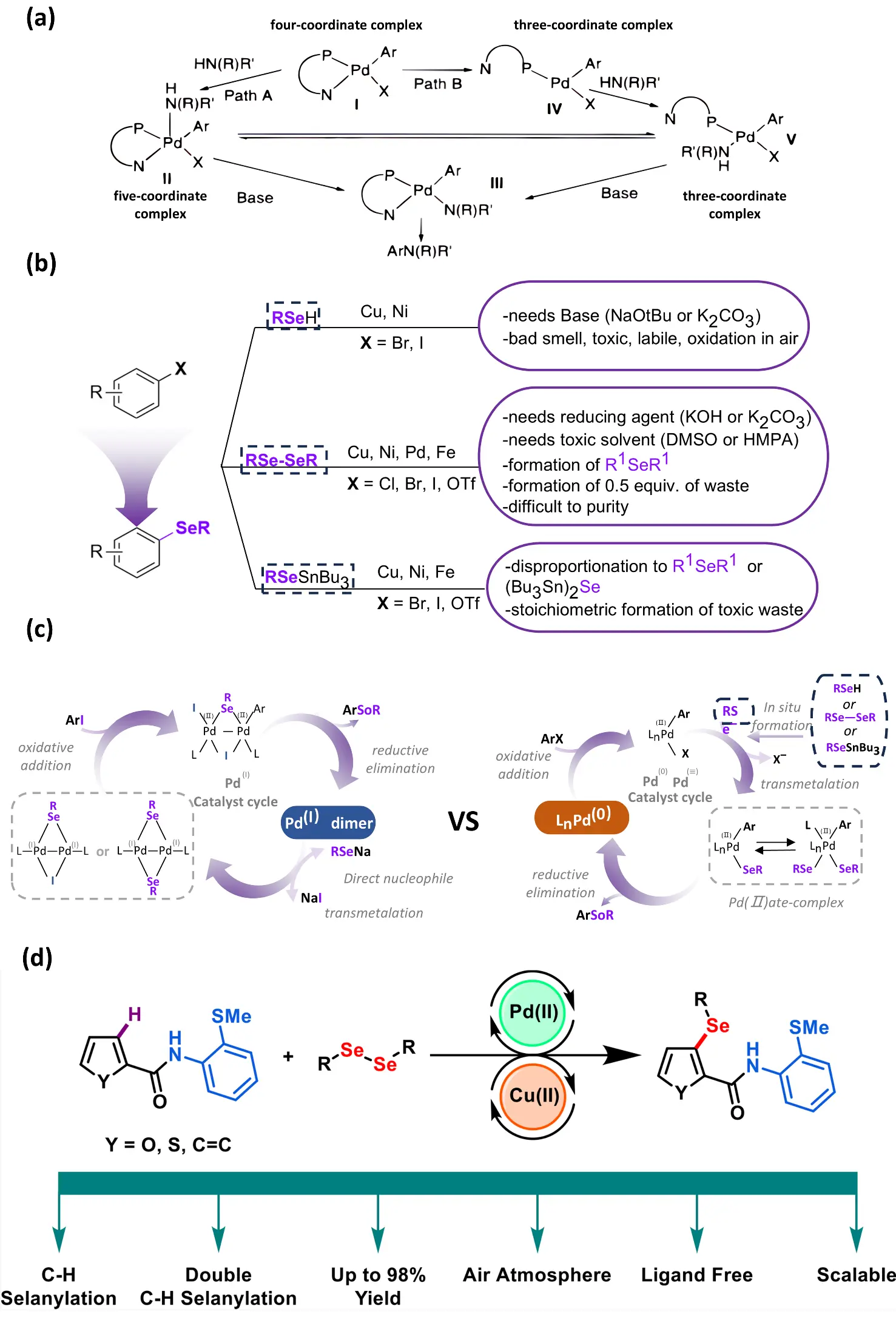

Transition-metal catalysis, as a versatile catalytic strategy, can participate in nucleophilic addition reactions and can also mediate electrophilic cycloalkylation or radical cyclization processes. In the domain of transition metal-catalyzed synthesis of selenium-containing heterocycles, the ligand systems developed by the Buchwald team in 1998 have provided significant theoretical underpinnings and practical applications (Figure 3a), thereby facilitating research in this field [25]. The remarkable features of these ligand systems lie in their high electron density, tunable steric properties, and strong ability to stabilize low-valent metal centers. Notably, the Buchwald group’s dialkylphosphine ligands XPhos and di-tert-butyl-XPhos have demonstrated outstanding performance in C–N, C–C, C–O, C–F, and C–S coupling reactions [31,32], significantly accelerating reaction rates and suppressing metal deactivation. The strong σ-donating ability and steric tunability of Buchwald-type ligands effectively promote oxidative addition to aryl halides and stabilize key Pd(II) intermediates, providing a mechanistic rationale for their success in facilitating C–Se bond formation. However, compared with the construction of other heteroatom-containing bonds, methods for forming C(sp2)–Se bonds remain relatively limited. In particular, routes to non-symmetric selenoethers (e.g., Ar1SeR, where R = Ar2 or alkyl and R ≠ Ar1) are even more scarce. Against this backdrop, transition-metal catalysis—especially Pd-catalyzed cross-coupling—has emerged as one of the most promising and rapidly developing strategies for constructing C–Se bonds (Figure 3b). Christmann et al. (2024) [33] proposed that iodine-bridged Pd(I) dimers could catalyze C(sp2)–Se bond formation more efficiently (Figure 3c). This strategy relies on the oxidation of the more easily oxidized Pd(I) species to Pd(II). The Pd(I) dimers exhibit enhanced reactivity due to their lower oxidation potential and their propensity for rapid disproportionation, enabling faster coupling rates with fewer side reactions. As a result, this approach allows for more controlled construction of C–Se bonds. Pd catalysis can not only directly participate in C–Se bond formation but can also enable further post-functionalization after the construction of selenium heterocycles. In the previously mentioned work by Godoi [27], the selenium-containing heterocycles formed through electrophilic cyclization can undergo Pd-catalyzed Sonogashira, Suzuki, and other coupling reactions to achieve arylation or alkynylation, thereby significantly expanding the molecular diversity of selenium heterocycles. In addition, Badshah et al. (2023) [34] employed 2-methylthioacetamide as a directing group to achieve an efficient Pd(II)/Pd(IV)-catalyzed C–H direct selenylation, enabling selective Se incorporation at either the C3 position of chalcogen-containing heterocycles or the ortho-position of arenes (Figure 3d). This system not only overcomes the inherent C2/C5 regioselectivity of chalcogen heterocycles but also enables diselenylation in selected substrates. Mechanistic studies indicate that reversible C–H activation and Pd(IV) intermediates play key roles in the catalytic cycle. The participation of the Pd(IV) species introduces an oxidative manifold that enables reductive elimination to form C–Se bonds that would otherwise be inaccessible under classical Pd(II) catalysis, thereby expanding the reaction scope. Meanwhile, the presence of Cu(II) facilitates the chelation of by-products and regeneration of active Pd(II).

Despite the advantages of Pd-catalyzed selenium heterocycle construction in terms of selectivity and mechanistic design, its broader application is still constrained by several inherent limitations. First, Pd is a precious metal with high cost and limited availability. In addition, the strong coordination of selenium and sulfur atoms to Pd often leads to catalyst poisoning, requiring high ligand loading or excess oxidants to maintain catalytic activity. Moreover, when oxidation-sensitive functional groups are present, the oxidative environment and elevated temperatures commonly used in Pd-catalyzed systems may cause side reactions or reduced yields. Therefore, to overcome these bottlenecks, researchers have increasingly shifted their attention to other transition metals that are more economical, more resistant to coordination poisoning, milder in reactivity, or operate through fundamentally different mechanisms.

Among these alternative metals, copper has attracted considerable attention due to its low cost and favorable reactivity with selenium sources. Mandal et al. (2016) [35] developed a Cu-catalyzed ortho C–H direct selenylation of arenes using a removable 8-aminoquinoline directing group, enabling the efficient synthesis of aryl selenides from inexpensive diselenides in high yields. This system exhibits broad functional-group tolerance, accommodating halogens, alkoxy groups, and various heteroarenes such as pyridines and thiophenes. In addition, it is amenable to gram-scale synthesis, providing a practical and economical approach for the large-scale preparation of organoselenium compounds.

Nickel (Ni), owing to its reversible multivalent states (Ni(0)/Ni(I)/Ni(II)), offers distinct advantages in reductive coupling and C–Se bond construction involving unactivated substrates. Fang et al. (2018) [36] reported a Ni-catalyzed reductive selenylation of unactivated alkyl bromides using selenosulfonates as the selenium source, enabling the formation of various unsymmetrical selenides under mild conditions. The method is scalable to gram quantities and supports subsequent structural transformations. Owing to the inherently reductive nature of Ni-catalyzed pathways, these reactions typically avoid the need for external strong oxidants and more effectively mitigate the deactivating effect of selenium on the metal center.

In contrast, silver (Ag) catalysis exhibits unique selectivity with specific substrates. Rios et al. (2013) [37] reported an Ag(I)-catalyzed system in which diselenides undergo efficient selenylation with indoles in the absence of any ligands or additives. The catalytic cycle and regeneration of the selenium source proceed under ambient air, using O2 to produce 3-selenylindoles; if the C3 position is sterically hindered, a Plancher-type rearrangement occurs to afford 2-selenylindoles instead. Mechanistically, the reaction follows a classical electrophilic aromatic substitution pathway. Its operational simplicity and high atom economy make it superior to Cu-, Fe-, or metal-free systems.

Figure 3. (a) Buchwald-Hartwig coupling mechanism. Reproduced with permission of Ref. [25], Copyright © 1998 American Chemical Society. (b) Transition metal-catalyzed C(Sp2)–Se bond formation methods can be broadly categorized into three classes based on the selenium source employed and the accompanying reaction mechanism (upper section), alongside key challenges associated with the selenol anion nucleophiles used (lower section). (c) Dinuclear Pd(l) catalysis versus mononuclear Pd(0)/Pd(ll) catalysis and key challenges in C–Se bond formation. Adapted from Ref. [33], Copyright 2004 Chemical Communications. (d) Direct C–H Selenation at the C3 Position of Chalcogen Heterocycles or the Ortho Position of Aromatics. Reproduced with permission of Ref. [34], Copyright © 2023 American Chemical Society.

By introducing catalytic systems based on Cu, Ni, Ag, and other metals with distinct oxidation states and mechanistic characteristics, researchers have been able to overcome limitations associated with Pd-catalyzed C–Se bond construction, such as high cost, catalyst poisoning, and stringent oxidative conditions. These metals exhibit fundamentally different catalytic cycles: Pd systems typically rely on oxidative addition, reductive elimination, and C–H activation; Ni systems often proceed through single-electron or reductive pathways, thereby avoiding deactivation caused by strong Se coordination; Cu systems generally follow electrophilic or copper-oxide-mediated pathways and cooperate with directing groups to achieve ortho activation; Ag catalysts enhance electrophilic activation of the Se–Se bond via Lewis acidity and operate through a classical electrophilic aromatic substitution mechanism. Together, these mechanistic distinctions ensure that different metal catalysts offer complementary reactivity patterns in C–Se bond formation and selenacycle synthesis, providing a broader and more feasible strategic foundation for advancing organoselenium chemistry.

Transition-metal catalysis, as an effective synthetic strategy, enhances both the efficiency and selectivity of selenium-containing heterocycle formation while broadening the accessible substrate scope. By coordinating and activating selenium species and reaction substrates, it lowers the reaction energy barrier and enables cyclization pathways that are difficult to achieve using classical methods. Moreover, it allows precise control over regio- and stereoselectivity, making it an indispensable component in the synthesis of selenium heterocycles.

2.2. Modern Redox-Driven Approaches

Although transition-metal catalysis remains a central approach for C−Se bond construction, issues such as metal cost, catalyst deactivation, and oxidative conditions have motivated the search for milder and more sustainable alternatives. Recent advances in visible-light photocatalysis and electrochemical activation now enable the controlled generation of selenium radicals or high-valent species without strong oxidants, opening new routes to selenium-heterocycle assembly. The following sections summarise these redox-driven strategies and highlight how they complement and extend classical catalytic methods.

2.2.1. Photocatalytic Selenization

Photocatalytic selenation reactions have garnered significant attention in recent years, particularly in the context of visible light-induced radical cascade reactions. In 2013, Chemical Reviews [38] published a study on the application of transition metal complexes in visible light redox catalysis, which demonstrated the enormous potential of radicals generated by visible light redox catalysis in combining with other functional groups to construct molecular complexity in chemical reactions. In a typical photocatalytic selenylation process, visible light serves as the energy input to excite the photocatalyst, initiating single-electron transfer (SET) to generate Se-centered radicals from diselenides or selenium precursors. These reactive species undergo regioselective addition to alkenes, alkynes, or heteroarenes, followed by cyclization or radical–polar crossover steps to afford the final product. Owing to the high polarizability of selenium, the resultant radicals display enhanced stability and rapid recombination kinetics, providing a mechanistic basis for the high efficiency of light-driven C–Se bond formation [21,39].

Building on the concept of radical-based selenylation, Jiang et al. (2024) [40] developed a visible-light-induced regioselective selenohydroxylation of enamides. In this methodology, diaryl diselenides undergo homolytic cleavage under light irradiation to generate selenium radicals, which add to the enamide. Subsequent oxidation and selective C=C bond cleavage in the presence of oxygen furnish α-hydroxy-β-selenamidated products with high selectivity (Figure 4c). In contrast, Dalberto et al. (2020) [41] developed a metal-free UVA-induced α-selenylation of ketones, in which diselenides undergo direct photolysis to yield selenium radicals that react with in situ-formed enamines under aerobic conditions. This protocol operates under mild, eco-friendly conditions and considerably expands metal-free photochemical selenylation.

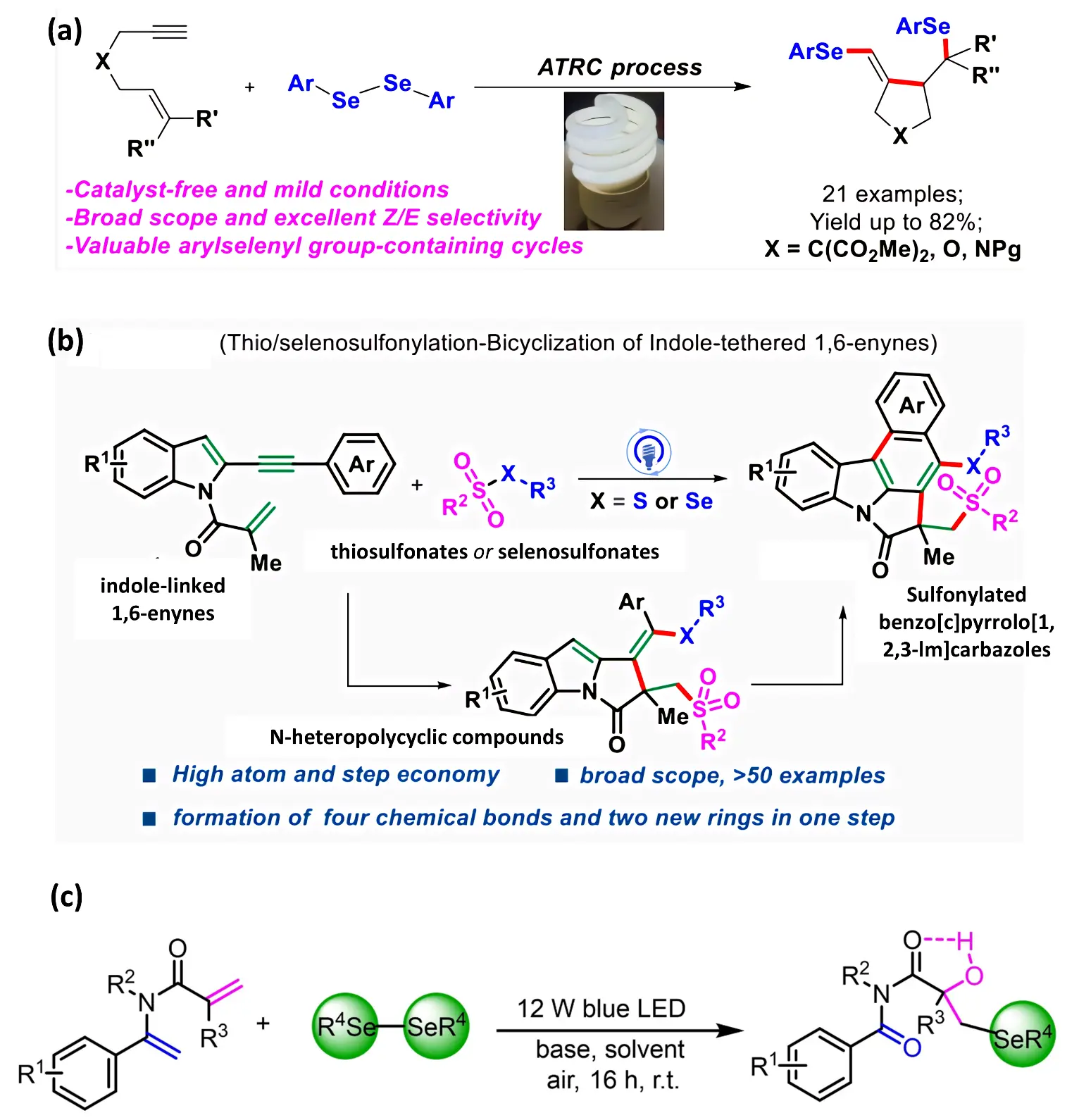

Driven by these fundamental studies, photocatalytic selenylation reactions have gradually expanded into the field of heterocycle construction. Hou et al. (2020) [42] validated this synthetic approach by testing terminal and internal alkynes derived from 1,6-alkynes in a visible light-mediated diaryl selenide cyclization reaction, yielding various selenium-containing rings in moderate to good yields (Figure 4a). More recently, Zuo et al. (2024) [43] established for the first time a photocatalytically initiated radical-mediated thio/seleno sulfonylation-bicyclization reaction [44,45,46] of indole-based 1,6-alkynyls, achieving the first photocatalytically driven radical cascade reaction. This approach enabled efficient assembly of benzo[c]pyrrolo[1,2,3-lm]carbazole scaffolds (Figure 4b), which are widely found in bioactive natural products and drug molecules.

The photocatalytic selenylation reaction is a highly efficient synthetic method, which is beneficial for the construction of complex organic molecules. This synthetic method has several advantages, such as being relatively easy to operate, having a high yield, and being applicable to a wide range of substrates. As research in this field continues to advance, the unique application values of photocatalytic selenification reactions in an increasing number of fields will gradually emerge.

Figure 4. (a) Visible-Light-Mediated Cyclization of 1,6-Alkyne to Diaryl Selenides. Reproduced with permission of Ref. [42], Copyright © 2020 American Chemical Society; (b) Photocatalytic Study of Indole-Derived 1,6-Alkenyl Thiazoles/Selenosulfonyl-Bicyclization Leading to Substituted Benzo[c]pyrrolo[1,2,3-lm] carbazole derivatives. Reproduced with permission of Ref. [43], Copyright © 2024 American Chemical Society; (c) Visible light (12 W blue LED) induces homolysis of diaryl diselenides to generate selenium radicals, enabling the regioselective construction of α-hydroxy-β-seleno amide compounds. Reproduced with permission of Ref. [40], Copyright © 2024 © 2024 Wiley-VCH GmbH.

2.2.2. Electrochemical Synthesis

Electrochemical synthesis has emerged as an efficient and sustainable platform for constructing C–C and C–heteroatom bonds, offering precise redox control without the need for external oxidants or transition metals. Compared with traditional reagent-driven oxidation, electrochemical selenation proceeds under mild conditions, enabling the clean generation of radical or anionic intermediates with minimal waste output. Mechanistically, anodic oxidation directly generates Se-centered radical cations from diselenides or selenides, whereas cathodic reduction furnishes nucleophilic Se− species, allowing bidirectional redox modulation that is difficult to achieve through purely chemical oxidation [47,48,49,50]. This tunability accounts for the superior selectivity, functional-group tolerance, and intrinsic safety of selenium radical pathways [51,52].

Building on these mechanistic advantages, Guan et al. (2019) [53] developed a novel electrochemical oxidation cyclization reaction of alkenyl carbonyls and diselenium ethers for the synthesis of selenodihydrofuran and oxazoline. This work established a representative radical-mediated selenocyclization mode and marked an essential step in electrochemical selenacycle construction. Subsequently, Cheng et al. (2023) [54] reported an electrochemical oxidation-promoted selenocyanation/intramolecular cyclization reaction between aromatic amides and NH4SCN or KseCN (Figure 5a) and successfully synthesized C3-functionalized benzoseen and benzothiophene derivatives, achieving direct C3–H functionalization without halogen preinstallation. The site selectivity is attributed to proximity-induced Se capture followed by oxidative annulation, highlighting the compatibility of electrochemistry with C(sp2)–H activation logic.

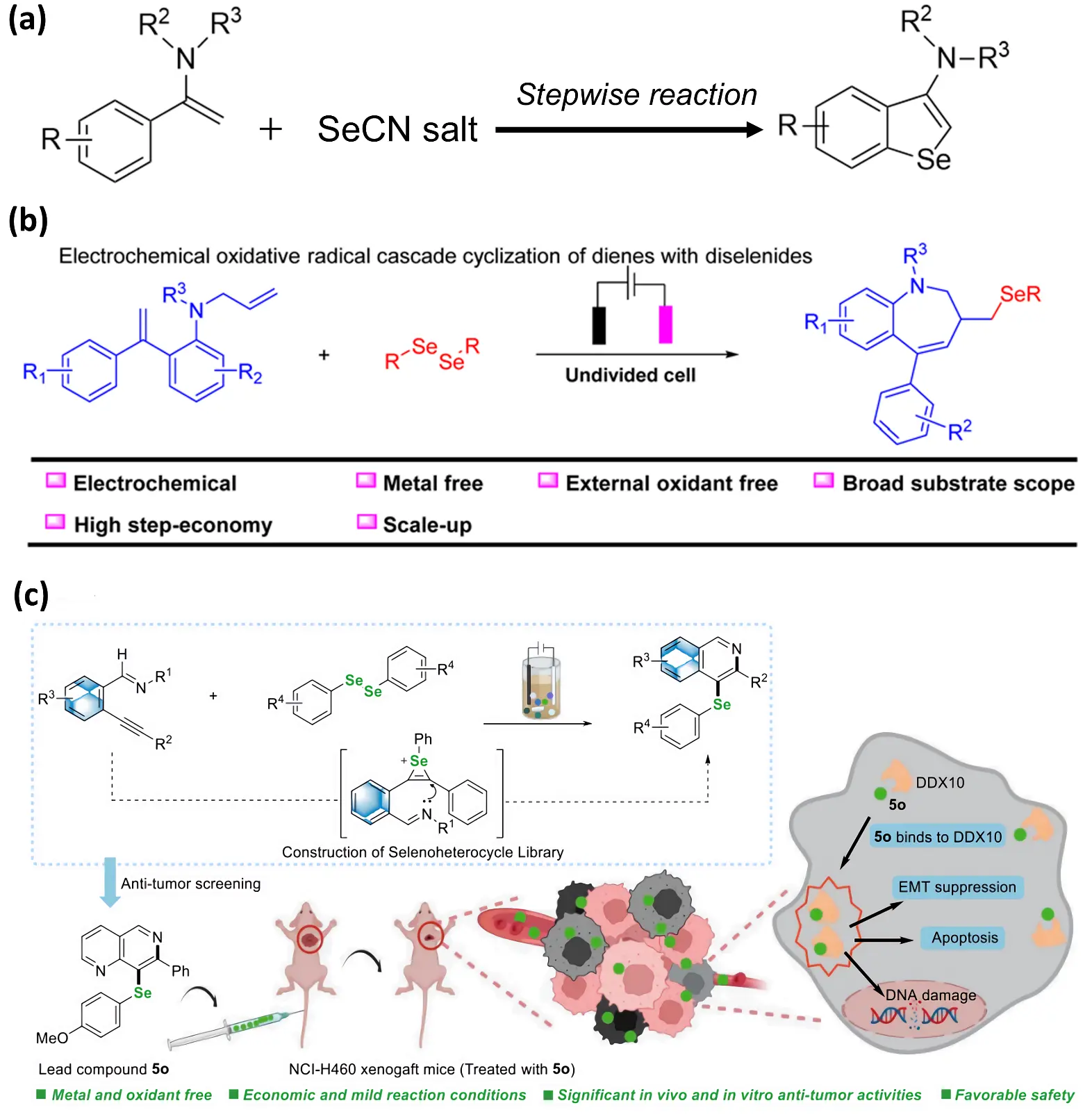

On this basis, Hu et al. (2024) [55] further advanced the application of electrochemical systems to the synthesis of seven-membered selenacycles. They reported an electrochemical oxidative radical cascade between dienes and diselenides, enabling the construction of seleno-benzotetralin frameworks under metal-free, oxidant-free, and base-free conditions (Figure 5b). Due to the unfavorable entropic effects and ring distortion, the construction of seven-membered selenacycles remains highly challenging in synthesis. Electrochemical initiation can overcome these obstacles by promoting rapid radical cyclization, allowing ring closure to occur before β-scission or over-oxidation takes place. Meanwhile, Yang et al. (2023) [56] developed an electrochemically driven tandem cyclization using unsaturated sulfonylimines as substrates. This tandem radical relay complements Guan/Cheng-type annulations by extending electrochemistry toward N-bearing precursors, demonstrating that substrate electronics—not only diselenide architecture—govern cascade efficiency and broadening the precursor scope beyond carbonyl derivatives.

Most recently, Xu et al. (2025) [57] proposed the modular electro-synthesis of selenium-containing heterocyclic compounds under standard reaction conditions and in accordance with the findings of preceding research [15], developing a modular electro-selenation platform based on diselenated chalcones, providing divergent access to 3-selenochromones and alkyl aryl ketones (Figure 5c). This modular reactivity enables mechanistic divergence across SET, SRN1, or radical-chain pathways, supporting late-stage derivatization, which is a capability rarely achievable in thermal cyclizations.

Overall, electrochemical methods enable the efficient formation of selenacycles under green and sustainable conditions by controlling the generation of high-valent selenium species or selenium radicals at the electrode. These approaches not only significantly enhance the reaction diversity for constructing selenium-containing heterocycles but also provide powerful tools for the modular, highly selective synthesis of complex selenated frameworks.

Figure 5. (a) Electrochemical Oxidation of Selenocyanid with Cyclization for the Synthesis of Benzoselenophene and Benzothiophene. (b) Electrochemical Oxidation Cyclization of Diene with Diselenomethane. Reproduced with permission of Ref. [55], Copyright 2024 RSC Advances. (c) Modular electrochemical synthesis of selenium-containing heterocyclic compounds exhibiting potent antitumor activity in vitro and in vivo. Reproduced with permission of Ref. [57], Copyright © 2025 American Chemical Society.

2.3. Challenges and Unknowns

Challenges remain in controlling regioselectivity and stereoselectivity during C–Se bond formation, particularly when multiple reaction sites or chiral centers are present. Current methods also exhibit limitations in functional-group compatibility, particularly with acid-sensitive, nucleophilic, or heteroatom-rich motifs, thereby restricting late-stage modification of bioactive molecules. From a sustainability perspective, the use of greener solvents, enhancement of atom economy, and reduction of waste remain far from optimal. Mechanistically, radical and ionic pathways in photocatalytic and electrochemical systems are still not fully elucidated, reducing structure–reactivity predictability and complicating substrate design. Biological applicability constitutes an additional barrier: the metabolic stability, toxicity, and ADME behavior of selenium heterocycles remain insufficiently characterized. Finally, industrial-scale implementation faces hurdles in catalyst recovery.

To provide a clearer comparison of the practical performance of representative selenium-heterocycle construction strategies, including transition-metal catalysis, photocatalysis, and electrochemical methods, Table 1 summarizes key metrics such as typical yields, functional-group tolerance, and environmental factors (E-factors), highlighting both their complementary advantages and present shortcomings.

Table 1. Comparative summary of major synthetic strategies for selenium heterocycles.

|

Strategy |

Mechanism/Key Reagents |

Yield |

FG Tolerance |

Environmental/Operational Factor |

Notes/Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Nucleophilic displacement (SN2/Michael-type) |

Se⁻ attack on electrophile; reagents: NaHSe/KSeCN, diselenides + NaBH₄ or PEG-400; NHC-catalysed asymmetric variants |

60–95% |

Good for halides, activated alkenes; limited for strongly hindered or highly acidic groups |

Generally low E-factor (simple workup); scalable; few specialised equipments |

Simple ring construction, modular alkyl/aryl selenides; asymmetric control requires catalysts |

|

Electrophilic activation |

Electrophilic Se (PhSeCl, SeO₂, in situ Se⁺) activates π-bonds → cyclization |

50–90% |

High for π-rich systems; can oxidize acid-sensitive groups |

Often stoichiometric electrophiles → higher E-factor; generates salts/waste; mild conditions typical |

Rapid annulation to benzofused and heteroaromatic motifs; beware over-oxidation |

|

Radical relay/transition-metal-mediated coupling |

SET to form Se· or TM-mediated oxidative addition/reductive elimination; catalysts: Pd/Cu/Ni, peroxides, SRN1 conditions |

40–88% |

Broad for complex scaffolds; tolerant to many heteroatoms but TM poisoning by Se possible |

TM catalysis often leaves trace metals (biomedical concerns); ligand optimization required; medium E-factor |

Late-stage diversification, dense π-systems, complex molecule derivatization |

|

Photocatalytic strategies |

Visible-light induced SET → Se·/Se⁺ (Ir/Ru dyes or organic photocatalysts); LEDs |

45–85% |

Good for sensitive groups (mild conditions) but substrate window can be narrow |

Green photon source; low chemical oxidant load → lower E-factor; quantum efficiency varies |

Late-stage functionalization, radical annulations; metal-free options available |

|

Electrochemical synthesis |

Anodic oxidation → Se·/Se⁺; cathodic reduction → Se⁻; electricity replaces stoichiometric oxidant |

50–90% |

Good functional-group tolerance with careful potential control |

Very green in principle (oxidant-free); tuneable; requires electrochemical setup; electrode passivation possible |

Scalable (flow electrolysis), sustainable synthesis platform; ideal for modular divergent routes |

While classic transition metal catalysis demonstrates high efficiency, the presence of residual metal can impose limitations on its biological applications. It is therefore possible to control the issue at the source by replacing metals with organic catalysts that mimic metal-catalyzed mechanisms [15,58,59], or by developing bioinspired metal-targeted enzyme delivery systems that encapsulate metal catalysts within the hydrophobic pockets of human albumin [60,61], thereby enabling them to catalyze reactions specifically within living organisms. Alternatively, post-synthetic metal removal strategies can be achieved by developing biodegradable ligands, such as peptide-Pd complexes [62].

Photocatalysis offers high sustainability but suffers from narrow substrate generality and limited control over regio- and redox selectivity due to undesired H-abstraction or over-reduction of Se intermediates. The low quantum yields in many systems indicate inefficient photonic utilization [63]. Advancing substrate-adaptive photocatalysis, creating dynamic light-responsive interfaces [64,65], tunable binding sites, or deformable surfaces [66,67] may shift the paradigm from substrate adapts to catalyst toward catalyst adapts to substrate. Future directions include activation of unreactive C–H bonds [68], enhancing quantum efficiency, and hybridizing photocatalysis with electrochemical/flow-driven systems to enable continuous radical generation and scalable process integration [69].

Despite its green and efficient nature, electrochemical selenylation still faces several challenges [15,70], particularly in systems containing multiple unsaturated motifs, where improvements in current efficiency, mitigation of electrode passivation [71,72], and control of regioselectivity remain crucial. Compared with photocatalysis, electrochemistry offers broader redox tunability, yet requires more stringent hardware precision. The development of flow electrolysis [73], redox-switchable catalysts, and paired electrolysis techniques [74] is expected to enable programmable selectivity toward asymmetric C–Se bond construction in the future.

Electrochemical selenylation, though inherently green, faces challenges such as controlling selectivity in polyunsaturated frameworks, electrode passivation, and current efficiency. Compared with photocatalysis, electrochemistry provides broader redox tunability but requires greater instrumental precision. Progress in flow electrolysis, switchable redox catalysts, and paired-electrolysis schemes is expected to unlock programmable asymmetric C–Se bond formation. Importantly, the convergence of electrochemical and photochemical radical control may represent the most powerful future platform for scalable selenacycle synthesis.

3. Spectral Characterization Techniques

After mastering the synthesis methods for selenium heterocycles, the next challenge is elucidating their detailed structures and electronic properties. Spectroscopic and structural characterization techniques are key to understanding the subtle differences between these compounds and guiding their application development. Precise characterization of the Se–C bond length and electronic environment via these techniques provides the foundational knowledge to rationally design molecules with desired optoelectronic properties, such as optimal bandgaps for OPVs.

3.1. Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR)

The synthesis of selenium-containing heterocycles often accompanies sensitive substituents, and conventional elemental analysis and infrared spectroscopy cannot unambiguously determine the precise chemical environment of selenium (Se). Owing to selenium’s relatively large nuclear charge, moderate quadrupole moment, and highly variable electronic environment, its NMR-active isotopes—particularly 77Se (spin-½)—exhibit distinctive spectroscopic responses that are not accessible for lighter chalcogens such as sulfur or oxygen. This makes NMR not only applicable but essential for elucidating the structures of selenoheterocycles.

In their review, Silva et al. (2021) [75] highlighted that 77Se NMR spectroscopy features an exceptionally broad chemical-shift range and exhibits high sensitivity to the oxidation state, substituent patterns, and steric–electronic environment of selenium centers. These attributes make it a powerful tool for elucidating reaction mechanisms in organoselenium chemistry. By employing techniques such as 1H–77Se HMBC, 1H-coupled 77Se NMR, and the analysis of one-bond coupling constants, researchers can accurately identify reactive intermediates, quantify complex mixtures, and map the precise electronic environment around selenium atoms. In addition to chemical shifts, scalar coupling constants such as 1J(77Se–13C) and 2J(77Se–1H) enable differentiation between Se–C(sp2) and Se–C(sp3) environments, while pronounced downfield shifts are typically observed in oxidized or π-extended frameworks. Thus, 77Se NMR not only pinpoints the precise position of selenium within heterocyclic scaffolds but is also particularly valuable for monitoring changes in oxidation state and assessing how solvent or coordination environments modulate the electronic density around selenium. Collectively, these capabilities provide essential evidence that underpins both synthetic methodology development and mechanistic investigations. Shankar et al. (2022) [76], along with subsequent applications in inorganic cluster chemistry, demonstrated that combining one-dimensional 1H, 13C, and 77Se NMR with infrared (IR) spectroscopy and high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) can greatly enhance the structural elucidation of selenoheterocycles. Such multimodal integration compensates for limitations inherent to NMR, particularly signal broadening in paramagnetic or fluxional systems, making spectral assignment more robust when selenium atoms occupy magnetically similar sites. Moreover, by comparing experimental 77Se chemical shifts with density functional theory (DFT) calculations, researchers can establish empirical or quantitative correlations between chemical shifts and local electron density. This approach effectively “translates” spectroscopic data into electronic-structure information, enabling in situ characterization of the electronic environment in selenium-containing heterocycles—for example, determining whether selenium occupies a vertex or linkage position within clusters or ring systems.

In more specialized cluster and selenoheterocyclic systems, a lot of studies [77,78] systematically compared experimental 77Se chemical shifts with values obtained from various computational methods (including B3LYP, mPW1PW91, and MP2/GIAO). They found that low-cost DFT methods exhibit excellent linear correlations with higher-level approaches in predicting δ(77Se), with regression coefficients (R2) often reaching ~0.98 or higher. This strong correlation allows computed shifts to assist in assigning the resonances of individual selenium atoms in multi-selenium systems and in confirming their positions within the molecular framework. The authors also emphasized that in large polyselenium clusters, the chemical-shift differences between distinct selenium sites typically exceed the intrinsic computational error, thereby increasing confidence in spectral assignments. Furthermore, Bould et al. highlighted that 77Se chemical shifts are extremely sensitive to the local electronic environment, spanning very wide ppm ranges across different systems; as a result, preliminary computations combined with experimental measurements provide a significantly faster and more reliable strategy for identifying selenium sites.

In summary, 77Se NMR stands as a uniquely powerful tool for resolving selenium-containing heterocycles due to its broad chemical-shift window, tunable coupling behavior, and strong correlation with electronic structure. When coupled with DFT shift prediction [77,79], J-constant profiling [80], and orthogonal spectroscopies such as IR/HRMS, selenium sites within complex or multinuclear frameworks [81] can be assigned with quantitative confidence. These capabilities surpass those of conventional elemental analysis or FT-IR, positioning 77Se NMR as the analytical backbone for modern Se-heterocycle research—particularly when characterizing reactive intermediates or validating mechanistic hypotheses in situ.

3.2. Single Crystal Diffraction

As a definitive method for elucidating spatial structure, single-crystal X-ray diffraction (SC-XRD) is particularly valuable for selenacycles and remains the only experimental technique capable of directly and quantitatively determining Se–C bond lengths. Due to the strong scattering power of selenium, SC-XRD offers markedly higher electron-density resolution than structures containing lighter chalcogens. This enables direct and quantitative determination of Se–C bond lengths, ring puckering, intermolecular stacking, and chalcogen-bonding interactions—structural details that cannot be reliably inferred from spectroscopy alone. Silva et al. (2021) [75] noted in their review that many selenoheterocycles and related selenium complexes rely on single-crystal X-ray diffraction (XRD) as a key method for structural confirmation—particularly when the compounds are thermodynamically or kinetically unstable or cannot be fully characterized by NMR or other spectroscopic techniques. They also reported a number of XRD-determined bond lengths and configurations that support spectroscopic assignments and theoretical calculations. Meanwhile, Silva et al. (2024) [82] mentioned that as the size of the substituents continuously increases, the chemical bonds between carbons gradually weaken, while those between silicones gradually strengthen. By the same token, the size of the substituent and its electronic properties also have a very significant impact on the length of the Se–C bond. Kravchenko & Buslaev (2010) [83] demonstrated that alkyl substituents, compared with phenyl substituents, can more effectively weaken tin-halogen bonds. This indicates that the electronic properties and steric hindrance of substituents have a very significant impact on bond lengths. In addition, X-ray/EXAFS techniques can determine average bond lengths with an accuracy of approximately ±0.02. However, these methods have limited resolution when it comes to distinguishing very similar bond lengths of the same type. Therefore, single-crystal XRD provides an irreplaceable and directly quantitative advantage in differentiating subtle bond-length variations (for example, differences on the order of 0.01–0.05 Å arising from different substituents) [84]. Beyond static structure determination, SC-XRD also functions as a powerful mechanistic diagnostic tool. Typical Se–C bond distances fall within 1.92–1.98 Å for sp2 frameworks, whereas sp3 centers extend to 1.97–2.03 Å due to reduced π-antibonding interactions [19]. Deviations greater than ~0.05 Å generally indicate intermolecular chalcogen bonding or an oxidation-state increase toward Se(IV) [85]. These studies have conducted a detailed analysis of the Se–C bond length from the perspectives of bond energy trends and substituent comparisons. Notably, shortening of Se–C bonds correlates with increased HOMO–LUMO overlap [86,87] and enhanced charge transport, whereas extended bonds indicate weakened conjugation and reduced orbital interactions [88]. In supramolecular systems, Se···O or Se···π contacts identified crystallographically directly translate into measurable shifts in photoluminescence or redox potential [89], offering a structure–property correlation framework unavailable via routine NMR or UV–Vis analysis. Such an analysis provides a theoretical basis for analogizing the bonding behaviors of other main group elements, allowing people to analogize the bonding behaviors of other main group elements based on this basis. This is the same as the difference in the bond length of Se–C observed during the single crystal diffraction process, and the two show consistency.

3.3. Raman Spectroscopy

Raman spectroscopy provides a vibrationally resolved fingerprint of selenium-containing heterocycles, where inelastic scattering directly reflects the bond-order distribution and electronic polarization around selenium centers. The technique is particularly effective in distinguishing Se–C, Se–Se, and Se–O motifs, offering a fast, non-destructive method for mechanistic assignment that complements NMR and SC-XRD. Se–C stretching typically appears at 230–290 cm−1, while Se–Se symmetric stretching bands are observed at 250–350 cm−1, red-shifting with increased conjugation or oxidation [90,91]. Se–O modes emerge at higher frequency windows (510–620 cm−1), reflecting stronger dipole character [92]. These well-defined Raman domains enable rapid assignment of selenium coordination environments even when NMR broadening or crystal growth proves challenging.

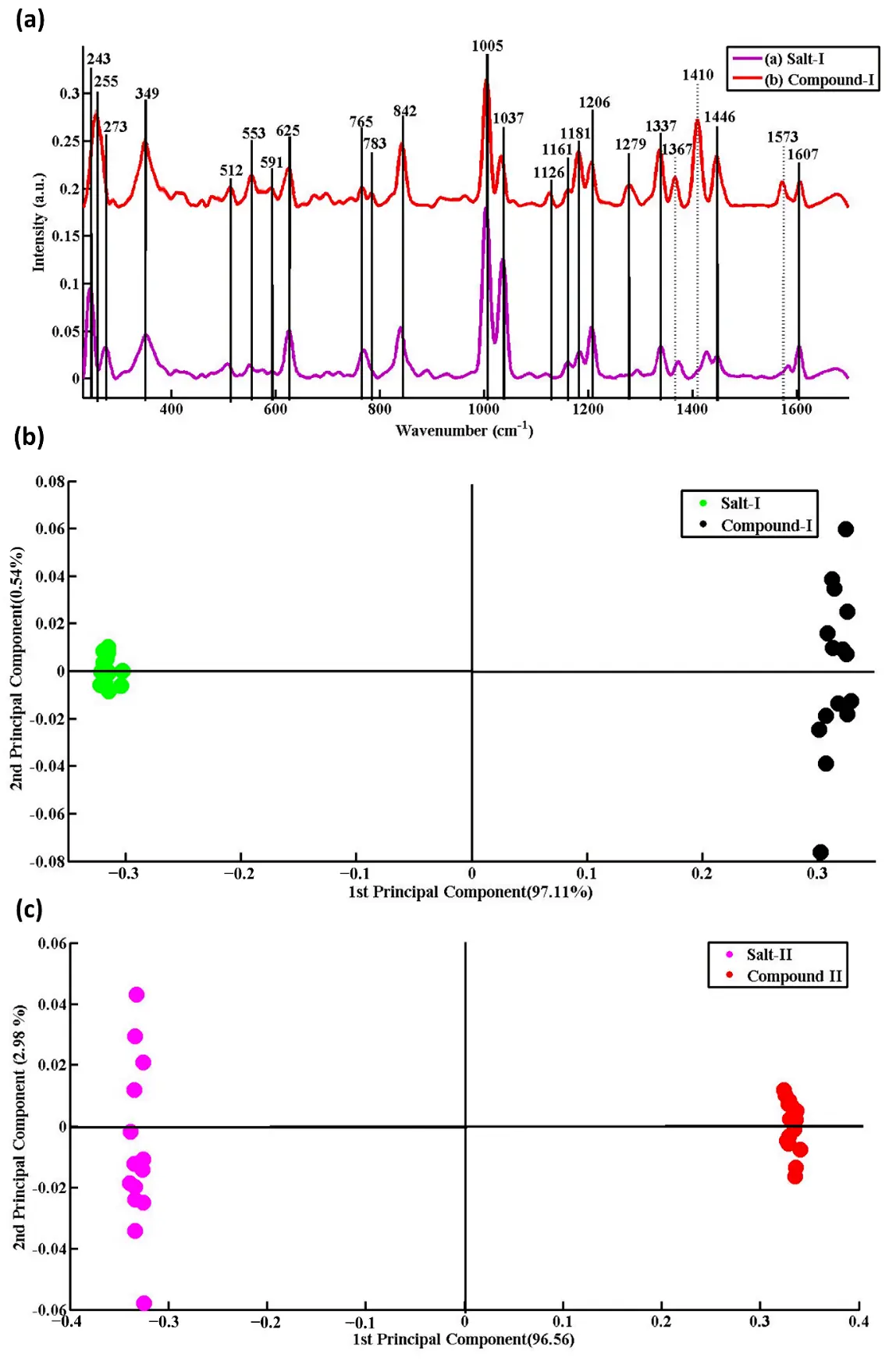

Ashraf et al. (2022) [93] used Raman spectroscopy to analyze and characterize imidazole Salt-I, imidazole Salt-I (NHC), and their corresponding selenium NHC compounds (Figure 6a). Combined with principal component analysis (PCA), the different salts and their Se complexes could be clearly distinguished (Figure 6b), which highlights the advantages of Raman spectroscopy in elucidating the structures of organoselenium compounds. The technique overcomes the limitations of traditional methods such as X-ray crystallography, FT-IR, and NMR—which often require complex sample preparation, are costly, and time-consuming—and offers notable benefits including rapid analysis, non-destructive measurement, and minimal sample requirements. Furthermore, in the study by Younas et al. (2023) [94], Raman spectroscopy combined with density functional theory (DFT) was employed to systematically analyze the vibrational spectral features of three different benzimidazolium salts and their corresponding Se–NHC complexes. The authors found that the Se–C bond in the complexes exhibits a distinct characteristic Raman band at approximately 1410–1416 cm−1, accompanied by an enhanced polarizability of the benzimidazole ring and a significant increase in Raman signal intensity. These observations provide strong evidence for the successful formation of the Se–NHC complexes. Meanwhile, Huda et al. (2023) [95] utilized surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS) to investigate the antifungal mechanism of Se–NHC complexes against Aspergillus flavus. Their results revealed several Se–NHC–induced biochemical effects, including protein conformational alterations, membrane disruption, and changes in nucleic acid structures. In addition, chemometric approaches such as PCA and PLS-DA enabled high-accuracy classification of Raman spectra from different treatment groups. Furthermore, Raman spectroscopy has been shown to be highly effective in characterizing various organometallic compounds, including dimethyl selenone, selenourea, organoselenol, organohalogenated selenium adducts, and transition metal organoselenium compounds [96,97,98]. Surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS) further amplifies Se-based signals by orders of magnitude [99], enabling trace detection in biological medi [95] and real-time monitoring of reaction intermediates [100]. In situ Raman coupled with electrochemical or photochemical modulation has been successfully applied to track Se-centered radical formation, oxidation-state interconversion [11], and catalyst-bound transient species—processes often invisible to NMR. In summary, Raman spectroscopy and its enhanced variants have emerged as powerful tools for elucidating the structures of selenium-based heterocycles, confirming synthetic pathways, and uncovering their biological mechanisms of action. These techniques demonstrate broad potential in the research and development of organometallic and metal-based therapeutic agents.

3.4. Challenges and Unknowns

NMR chemical shifts are very useful for tracking changes in selenium coordination. However, their accuracy becomes lower when strong spin–orbit effects, hyperconjugation, or mixed electron states dominate the system [101,102]. In these cases, we often need relativistic corrections, ZORA-based methods, or SOC-included hybrid models to get a reliable shielding value [103]. A key future direction is to develop machine-learning prediction tools built from large DFT–NMR datasets [104,105]. Such models may allow non-linear prediction of shielding behavior beyond the limits of standard functionals.

SC-XRD offers very high structural accuracy, but it depends on crystals of good quality. This limits its use when we study fast-changing, short-lived, or highly redox-active intermediates [106]. Dynamic chalcogen bonding can also weaken or disappear during low-temperature refinement [107]. In addition, fitting disorder in complex structures may bring model-based errors [108]. Future solutions may include serial femtosecond crystallography, time-resolved 4D diffraction, new refinement algorithms, and even light-triggered crystal studies. These tools may allow real-time snapshots of reactive selenium species under catalytic turnover or photo-excitation [109,110].

Raman spectroscopy is fast and requires little sample, but it performs less well when the system has weak polarizability or many overlapping peaks. Low scattering efficiency in non-polar selenium frameworks and peak crowding in highly substituted or polymeric samples can make band assignment harder [111]. Future progress may come from machine-learning peak separation [112], time-resolved Raman [113], and TERS-level enhancement. Together [114], these approaches may offer very high-resolution vibrational mapping and real-time tracking of selenium bond changes.

Overall, 77Se NMR is very strong in showing how electrons are distributed. SC-XRD gives a direct atomic-level structure. Raman spectroscopy captures bond-vibration signals and responds well to changes in bond order. However, each method alone still struggles to describe short-lived selenium species. A more complete workflow may work better. We can first use NMR to map the electron environment. Then, Raman can monitor vibration changes in real time. Finally, SC-XRD or MicroED helps fix the exact geometry. This step-by-step approach may build a full structure-to-function analysis system. If these tools are further combined with AI-based spectrum processing and time-resolved crystallography, the method may reach sub-picosecond resolution for catalytic intermediates. This could eventually allow reconstruction of the full reaction pathway in selenium heterocycles and clarify how their reactivity evolves over time.

Figure 6. (a) Raman spectroscopy is employed to analyze and characterize two NHC salts and their respective selenium NHC compounds. The average Raman spectrum of imidazole salt-I (A) is shown in red, and the corresponding average Raman spectrum of selenium NHC compound-I (B) is shown in purple. The dashed lines are used to align the common peaks of the salt and the compound, indicating the changes in the same vibrational modes between the two spectra. (b,c) The principal component analysis scatter plot of the Raman spectral data for imidazolium salt-I(II) is represented by green dots (purple dots), while the corresponding Raman spectral data for selenium NHC compound-I is indicated by black dots (red dots). Reproduced with permission of Ref. [93], Copyright 2021 Elsevier B.V.

4. Functional Applications

Building upon the spectral and structural insights discussed in Section 3, particularly the correlations revealed by 77Se NMR, SC-XRD, and Raman vibrational mapping, selenium heterocycles can now be rationally connected to their functional performance in both materials and biological systems. The ability to tune HOMO–LUMO distribution, enhance intermolecular Se···Se/Se···π interactions, and extend light-harvesting windows underpins their use in organic optoelectronic devices such as OPVs. At the same time, the high polarizability and redox activity of selenium enable controlled ROS modulation, disruption of thiol-dependent metabolic pathways, and targeted interactions with protein active sites, providing a mechanistic basis for their emerging anticancer and antibacterial applications.

4.1. Optoelectronic Technology

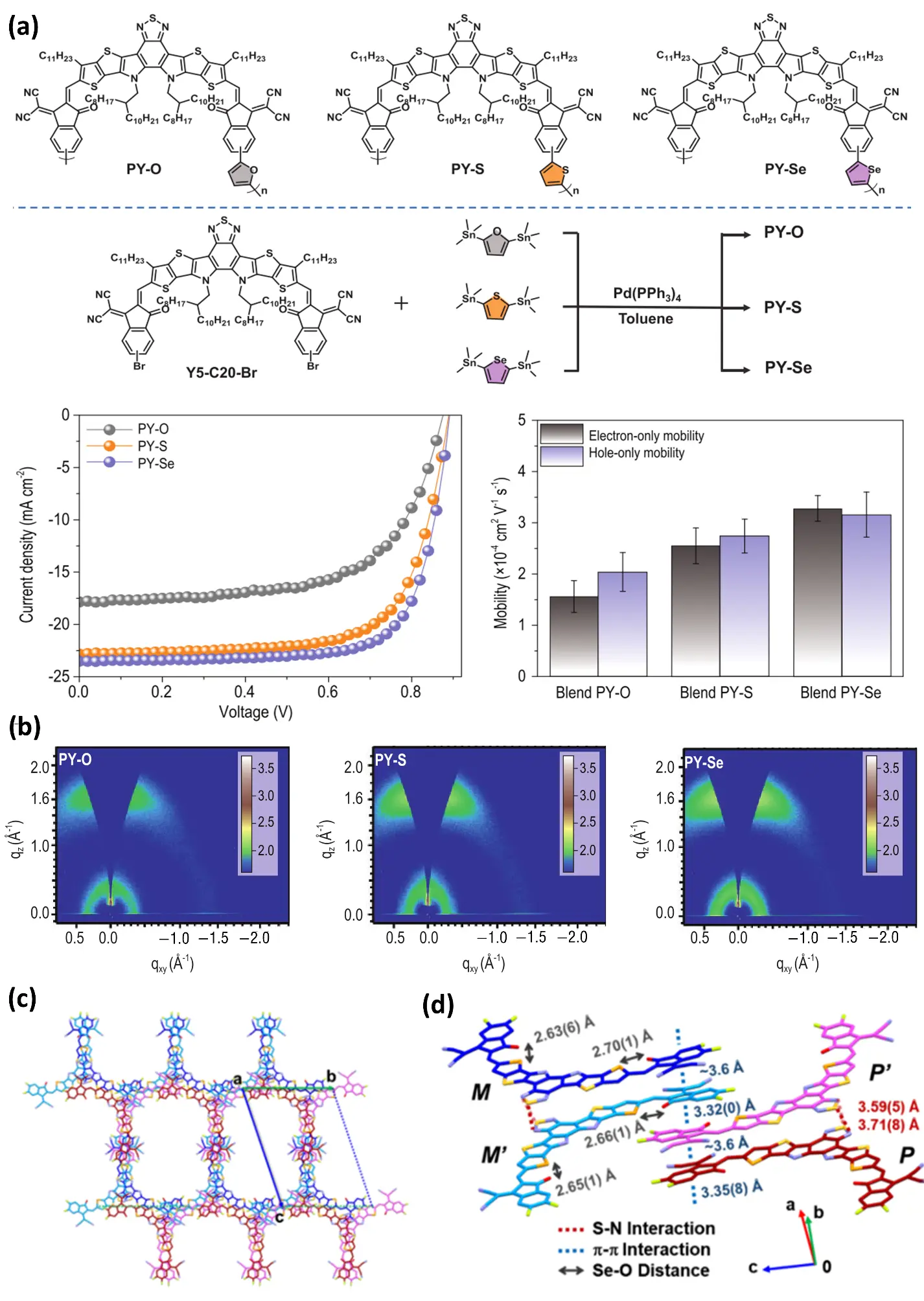

In the field of OPVs, selenium-thiophene copolymers have become a popular area of research in recent years thanks to their distinctive electronic structure and photophysical properties. The introduction of selenium units significantly broadens the material’s light absorption range and enhances its charge transport capabilities. This also improves the performance of devices [115,116,117,118]. During the initial exploratory phase, Intemann et al. (2013) [116] examined methods of selenium substitution in ladder-type indole diselenide polymers (PIDSe-DFBT). This resulted in the first synthesis of selenium-containing ladder polymers, revealing correlations between molecular weight and mobility. The novel indole diselenyl polymer (PIDSe-DFBT) exhibits superior absorption properties and higher charge mobility than its sulphur analogue (hole mobility: 0.15 cm2/(V·s); electron mobility: 0.002 and 0.008 cm2/(V·s)). This resulted in a 6.8% increase in the power conversion efficiency of photovoltaic cells, representing a 13% improvement on devices based on PIDT-DFBT. The study also confirmed a positive correlation between molecular weight and absorption coefficient. Wu et al. (2021) [119] designed and synthesized three polycyclic conductive polymer receptors: PY-O, PY-S, and PY-Se. These receptors use furan, thiophene, and selenium ether as electronic linkers [120], Meanwhile, the optimal performance of the All-PSC devices based on different power amplifiers was investigated, and the corresponding current density–voltage (J–V) curves were obtained. In addition, by analyzing the J–V characteristics of single-carrier devices, the hole and electron mobilities of the three systems were examined, among which the PY-Se blend exhibited more balanced hole and electron mobilities in the devices (Figure 7a). By replacing the electron-linking units in the polymer backbone from furan (O) and thiophene (S) to selenophene (Se), the electron mobility of the polymers increases significantly with the rising atomic number of the linker, demonstrating that the seleno-heterocycle effectively promotes charge transport. The 2D GIWAXS patterns of the pristine PY-O, PY-S, and PY-Se films indicate that PY-Se exhibits stronger crystallinity and phase stability in the solid state than PY-O and PY-S, and the atoms are arranged in a more ordered manner (Figure 7b). It demonstrates the highest performance and achieves a PCE of up to 15.48%, which is significantly higher than that of PY-O and PY-S. This study broadens the application of selenium, extending it from the polymer backbone to the electron-connecting units of polymer receptors. This allows for precise control over polymer molecules by transitioning from the single substitution of selenium groups. To validate the practical application of selenium in polymer photovoltaic materials, Fan et al. (2021) [121] used the selenophene macrocyclic skeleton and the selenophene π bridge as spacer units to construct the polyseleophene polymer small molecule receptor PFY-3Se. Compared with PFY-0Se without a selenium-containing ring, PFY-3Se exhibited a slightly higher electron mobility. And even stronger intermolecular interactions. All-polymer solar cell (PSC) devices based on PFY-3Se demonstrate superior performance, including PCE (15.1%), high short-circuit current density (23.6), high fill factor (FF) (0.737), and low energy loss. Furthermore, PFY-3Se-based all-PSCs exhibit minimal dependence of PCE on device area (0.045–1.0) and active layer thickness (110–250 nm), suggesting significant practical application potential. Together, these reports reveal a consistent structure–property–performance relationship in selenium-containing photovoltaic materials, wherein selenium incorporation enhances molecular polarizability and π-conjugation, promotes denser π-π stacking and balanced ambipolar charge transport, and ultimately translates into improved device performance, including elevated PCE and stability.

While ladder-type polymers highlight the backbone-level role of selenium, non-fullerene acceptors (NFAs) further demonstrate that atomic substitution can fine-tune frontier orbitals and thin-film nanomorphology. Thus, the narrative expands from polymer main chains to acceptor engineering, offering a complementary pathway for PCE enhancement. NFAs exhibit highly tunable chemical properties and play a crucial role in enhancing short-circuit current density (JSC) through the efficient absorption of near-infrared (NIR) sunlight. As acceptor materials, NFAs improve compatibility with polymers by modifying their molecular structure. The introduction of highly polar selenium atoms into the backbone of organic conjugated materials has been shown to reduce their optical bandgap effectively. In 2019, Lin et al. (2019) [122] focused on region-specific selenium substitution modification of NFAs. They successfully synthesised two isomeric ladder-type NFAs: SRID-4F and TRID-4F. The team demonstrated that the position of selenium substitution can regulate the material’s photoelectrical properties and thin-film morphology. SRID-4F in particular achieved a photovoltaic conversion efficiency of over 13% when paired with a polymer donor, providing key insights into the design of materials for high-efficiency organic solar cells. However, NFA molecules with an a-d-a (receptor-donor-receptor) structure have restricted interactions between the π systems due to the isolation of the central π nucleus, which significantly reduces charge transport capabilities. Based on this, Lin et al. (2020) [123] conducted a comparative study in 2020 between Y6 and its selenium-substituted analogue, CH1007. Crystallographic analysis of CH1007 revealed a triclinic crystal system with a $$P\bar{1}$$space group (Figure 7c). Its single-crystal structure shows that the molecules form dimers through terminal π–π stacking and face-to-face S/Se–N interactions between the BT/BS cores, resulting in a unit cell containing four enantiomers (Figure 7d). In the Figure 7c,d, a, b, and c denote the three crystallographic axes. M and P represent the two helical conformations (enantiomeric forms) of the molecule, while M′ and P′ correspond to the second pair of helical enantiomers observed in the unit cell. A comparison of the single-crystal parameters of Y6 and CH1007 indicates that the Se–O distance in CH1007 is slightly longer than the S–O distance in Y6. In addition, CH1007 exhibits smaller π-core torsion angles and D–A dihedral angles, as well as a shorter π–π distance between the two planes constructed on the indole rings of adjacent NFAs (Table 2). Mechanistically, selenium substitution lowers the bandgap through strengthened intramolecular charge transfer and reduces π–π stacking distance via enhanced chalcogen polarizability. Shortened π-core torsion angles and enlarged orbital overlap, as observed in CH1007 crystal packing, accelerate exciton dissociation and electron extraction, directly translating to high JSC and elevated PCE. The CH1007-based ternary device achieved a photovoltaic conversion efficiency of 17.08%, providing valuable insights into the design of highly efficient NFAs.

Collectively, OPV efficiencies have improved from 8% to over 15% due to selenium-induced bandgap narrowing, frontier orbital reorganization, and strengthened intermolecular stacking. These advances establish selenium heterocycles not merely as substitutional variants, but as active electronic modulators capable of re-engineering charge transport pathways at the molecular and device levels.

Table 2. Summary of Single-Crystal Parameters of Y6 and CH1007. Reproduced with permission of Ref. [123], Copyright © 2020 American Chemical Society.

|

Chirality |

Color |

$$\bm{\pi }$$-Core Torsion a |

D-A Dihedral Angle b |

S-O or Se-O Distance c |

$$\bm{\pi }$$-$$\bm{\pi }$$ Distance d |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Y6 |

M |

Blue |

9.9(1)° |

4.3(8)°/11.9(7)° |

2.64(0) Å/ 2.62(0) Å |

3.64(7) Å |

|

P |

Brick Red |

|||||

|

CH1006 |

M |

Blue |

7.3(9)° |

1.9(0)°/11.4(1)° |

2.63(6) Å/ 2.70(1) Å |

3.35(8) Å |

|

P |

Brick Red |

|||||

|

M' |

Azure |

2.2(6)° |

1.8(7)°/11.9(2)° |

2.65(1) Å/ 2.66(1) Å |

3.32(0) Å |

|

|

P' |

Pink |

a The torsion of the π-core was calculated on two planes established by the outward-oriented thiophenyl/selenophenyl rings located on opposite sides of the π-core. b The Dπ dihedral angles of −A were measured from each plane, which were constructed by the thiophene/selenophene substituents on both sides of the adjacent NFA and the five-membered indole ring. c The S-O or Se-O distances between the lateral chalcogen atoms of the −core and the carbonyl oxygen atom on the indole unit were measured. d the π–π distance between two planes formed by the indole rings of adjacent NFAs was determined.

Figure 7. (a) The molecular structures and synthetic routes of PY-O, PY-S, and PY-Se are presented. In addition, the J–V characteristics of the optimized PSCs under AM 1.5G illumination at 100 mW·cm−2, as well as the electron and hole mobilities of the devices based on the corresponding blends, are also provided. Reproduced with permission of Ref. [119], Copyright © 2021 National Science Review. (b) The 2D GIWAXS patterns of the pristine PY-O, PY-S, and PY-Se films. Reproduced with permission of Ref. [119], Copyright © 2021 National Science Review. (c) CH1007 belongs to the triclinic crystal system with a $$P\bar{1}$$ space group and exhibits molecular packing along the unit-cell axis. Reproduced with permission of Ref. [123], Copyright © 2020 American Chemical Society. (d) The single crystal of CH1007 contains two pairs of enantiomeric molecules within the unit cell. Reproduced with permission of Ref. [123], Copyright © 2020 American Chemical Society.

4.2. Biological Activity

Selenium-containing heterocycles have also gained wide attention in biomedical research, especially in anticancer and antibacterial therapy. Owing to the high polarizability and redox activity of selenium, these compounds can regulate cellular oxidative balance, disrupt thiol-dependent metabolic networks, and damage microbial membrane integrity. Increasing evidence now shows that the rational incorporation of selenium can alter electrophilicity, reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation pathways, and biomolecular binding affinity, thereby enhancing cytotoxicity toward cancer cells and improving antibacterial efficacy [124,125,126].

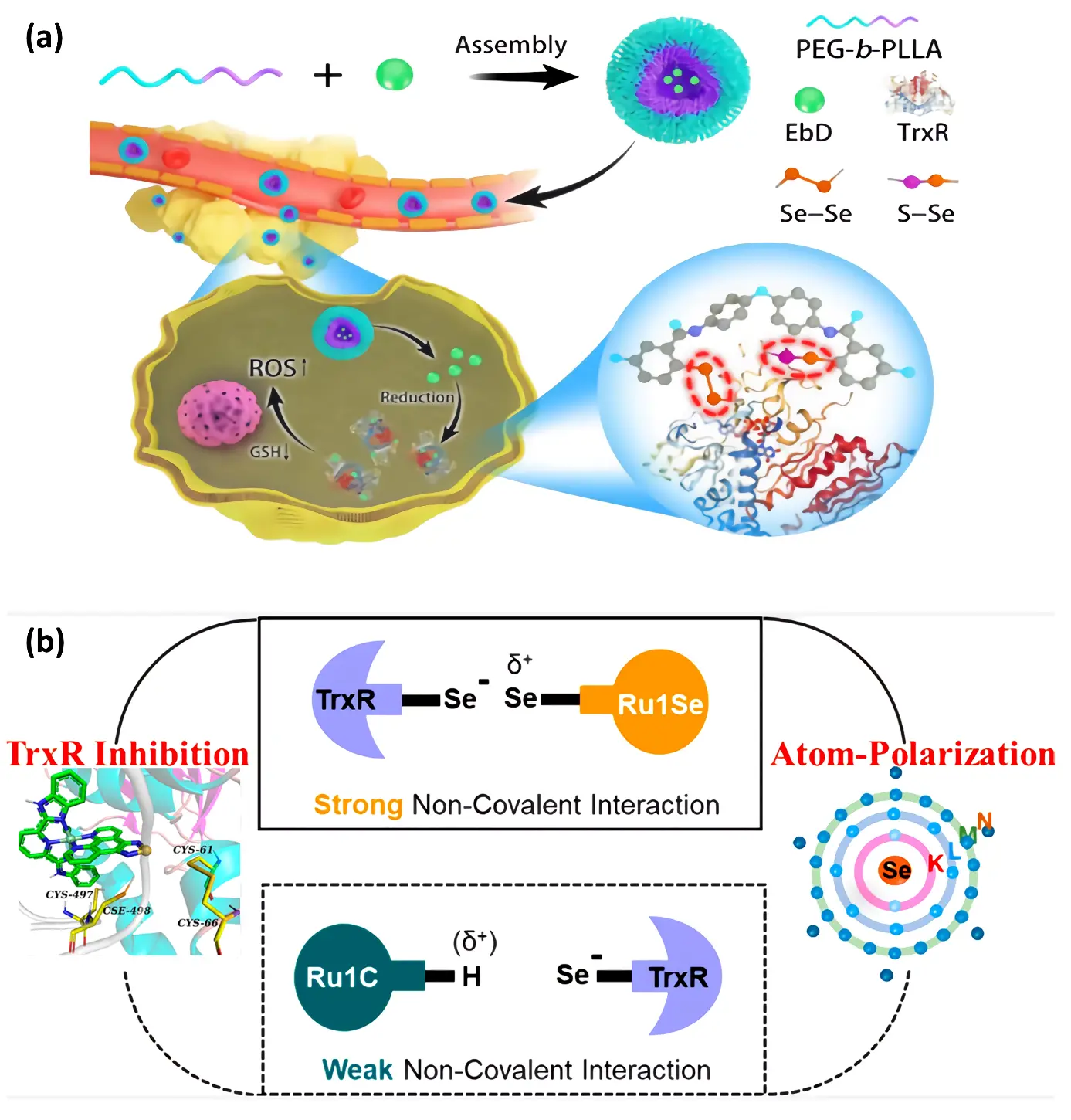

Selenazole nucleoside analogues provide a novel approach to cancer treatment by targeting and inhibiting thioredoxin reductase (TrxR) activity. The inhibitory effect relies primarily on the unique chemical properties of selenium atoms, particularly their polarizing effects and their ability to interact specifically with TrxR’s active sites. Previous studies [127,128,129] have shown that TrxR inhibitors primarily inhibit TrxR by covalently binding to the strong electrophilic center of the selenol group in the active motif (Figure 8a). However, achieving a good balance between inhibition efficiency and selectivity was difficult due to the strong interaction of covalent bonds. Therefore, Chen et al. (2022) [130] investigated a new strategy utilizing the polarization effect of selenium atoms to selectively inhibit TrxR (Figure 8b). They constructed a suitable electrophilic center, N−Se(δ+)−N−, to avoid interference from abundant Cys residues in human tissues. The researchers designed a drug that acts through strong noncovalent interactions to selectively inhibit intracellular TrxR activity. Research has shown that it can form relatively stable non-covalent interactions with the active sites of trxr, thus achieving selective inhibition of TrxR. This research provides a new method, which is to design selective chemotherapy by using TRXR-specific inhibitors. However, recent studies evaluating the toxicology of selenium-based therapeutics have emphasized the importance of assessing Se-induced redox imbalance and metabolic transformation pathways during drug development [131]. Therefore, despite the availability of strategies to improve drug selectivity, in vivo toxicity and metabolic evaluations remain essential.

Beyond antitumor applications, selenium frameworks extend their bioactive profile into antimicrobial domains, reflecting the versatility of chalcogen-mediated biochemical interaction. Benzoselenadiazole has shown significant potential in antimicrobial research in recent years as a selenium-containing heterocyclic compound. Luan et al. (2022) [132] designed and synthesized a benzoseazobenzene ligand to construct a UiO-68 topological framework (Se-MOF), which exhibits regular crystallinity and high porosity. Compared with metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) without benzene-selenium-diazole, the Se-MOF has a higher singlet oxygen generation efficiency and can also effectively kill Staphylococcus aureus under visible light irradiation. In vitro biofilm experiments confirmed that Se-MOF inhibits bacterial biofilm formation under visible light. These results suggest a promising strategy for subsequent research and development of MOF-based photodynamic therapy (PDT) drugs, promoting their conversion into clinical antibacterial photodynamic therapy drugs. Boualia et al. (2024) [133] reported on the synthesis and antibacterial activity evaluation of novel Se-NHC adducts (3a–e) and their corresponding benzimidazole salts (2a–e). The benzimidazole salts exhibited significantly enhanced antibacterial activity compared with reference antibacterial agents, particularly against Candida and Staphylococcus aureus. These studies have confirmed the effectiveness and potential of benzoseodazole as an antibacterial agent. Future research will optimize its structure to enhance antibacterial activity and selectivity, providing new solutions to address bacterial resistance.

The integration of selenium-containing materials with MOFs demonstrates multifaceted applications in the biomedical field. Beyond innovative explorations in antimicrobial applications, significant breakthroughs have also been achieved in the development of tumor-targeted drug delivery systems (DDS). Zhou et al. (2016) [134] developed a selenium-based polymer @MOFs nanocomposite, P@ZIF-8, offering a novel approach for multi-responsive drug delivery systems. This composite features a selenium-containing block copolymer (PEG-PUSeSe-PEG) micelle as its core and ZIF-8 (a type of MOF) as its shell, forming a core-shell nanostructure encapsulating the chemotherapy drug doxorubicin (DOX). Its core design ingeniously leverages the redox responsiveness of selenium-containing polymers and the pH responsiveness of ZIF-8: High concentrations of glutathione (GSH) or hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) within tumor cells can break the Se–Se bonds in the polymer, causing the micelles to disintegrate and release the drug. Meanwhile, under the acidic conditions of the tumor microenvironment (pH = 4.0–6.8), the ZIF-8 shell collapses, further accelerating drug release.

The aforementioned studies collectively advance the translation of selenium-containing biomaterials from fundamental research to clinical applications, while also providing valuable insights for subsequent material design targeting other diseases such as inflammation and metabolic disorders.

Figure 8. (a) Schematic representation of polyethylene glycol-β-polylactic acid/EBD micelles for tumor therapy based on selenium-containing dynamic covalent bonds targeting thioredoxin reductase. Reproduced with permission of Ref. [128], Copyright 2020 Chinese Chemical Society. (b) Utilizing the polarization effect of selenium atoms to construct an electrophilic center (−N−Se(δ+)−N−) for selectively inhibiting TrxR. Reproduced with permission of Ref. [130], Copyright 2022 American Chemical Society.

4.3. Challenges and Unknowns