Prosecution of Cases Involving Sexual Crimes without Physical Evidence

Received: 21 June 2025 Revised: 31 July 2025 Accepted: 21 October 2025 Published: 28 October 2025

© 2025 The authors. This is an open access article under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

1. Introduction

Sexual crimes comprise a profound violation of human rights, leaving victims with emotional, physical, and psychological damage that can take a lifetime to recover. These crimes range from harassment and assault to rape and child abuse [1]. Worldwide, such crimes remain alarmingly dominant, as the World Health Organization (WHO) reports that one in three women has experienced some form of physical or sexual abuse in her lifetime [2]. In America, an individual is sexually assaulted every 68 s, and only 2.5% of the offenders end up in prison [1].

Such felonies are prosecuted under criminal law, which holds criminals accountable while ensuring that the rights of both victims and defendants are maintained. To establish culpability beyond a reasonable doubt, the prosecution’s case strategy generally stands on a combination of physical, forensic, and testimonial evidence [3,4]. The challenges turned out to be even more pronounced during the trial. Prosecutors have the responsibility of presenting a case that meets the standard of proof beyond a reasonable doubt. In contrast, the defense often emphasizes discrediting the testimony of the victim or taking advantage of inconsistencies in narratives [5,6].

Forensic evidence holds a crucial role in establishing the facts of a case. Biological evidence, such as blood, hair, saliva, or semen, can corroborate the testimony of the victim, link the accused to the crime scene, and prove physical contact [7,8]. In the majority of cases, victims avoid talking about sexual abuse due to shame or psychological trauma, leading to the degradation and complete loss of forensic material [9]. In underprivileged areas with inadequate healthcare infrastructure, victims may lack access to proper medical and forensic examinations, which leads to the absence of physical evidence [10]. Sexual crimes lack witness due to their private and isolated nature [11]. In these scenarios, Jurors are often reluctant to rely solely on the victim’s account without additional evidence [12]. This dependence creates a justice gap, as many credible cases are dismissed or result in exonerations due to the absence of external witnesses [13].

The media portrays DNA as the conclusive factor in sexual assault prosecutions. However, less than 1% of criminal prosecutions rely on DNA evidence [14]. In many adult sexual assault cases, prosecutors build a case on behavioral, circumstantial, and testimonial evidence supported by trauma-informed investigative methods [15].

Beyond the need for evidence, bias in society often impedes the prosecution of sexual abuse cases. Victims usually face stereotypes about their appearance, behavior, or past relationships, which may be used to cast doubt on their integrity [16,17,18]. In these circumstances and challenges, it is necessary to explore how cases of sexual crimes can be successfully prosecuted without the availability of direct forensic evidence.

2. Literature Review

The research on sexual offenses indicates a large discrepancy between the presence of forensic evidence and the effective prosecution of criminals [19]. Although most studies point to the requirement of physical and biological traces, new research indicates that behavior, psychology, and digital evidence can also prove to be crucial [20]. Nevertheless, despite a widening base of knowledge, academic consensus is still divided and somewhat descriptive in nature [21]. This section critically reviews existing literature within four thematic areas—legal impediments, forensic limitations, psychological factors, and digital options—to highlight existing gaps and justify the current review [22].

2.1. Global Trends and Legal Barriers in Sexual Crime Prosecution

Internationally, sexual offenses continue to be the least effectively prosecuted crimes [23]. Conviction rates remain very low in most jurisdictions, largely because of the lack of concrete evidence. Victim-centered approaches and policy changes notwithstanding, prosecutorial results continue to rely considerably on the availability of concrete evidence [24].

Cross-country comparisons between developed and developing countries reveal differentiated procedural expectations. While others utilize trauma-informed practices to enhance testimony credibility, others still use medico-legal evidence as the main predictor of guilt [25]. Such a reliance creates a forensic gap that ignores the evidentiary value of behavioral, testimonial, or digital evidence [26]. In general, international legal systems are still bound by conventional evidentiary hierarchies, which emphasize the imperative to search for adaptive prosecutorial models that can maintain convictions even without physical evidence [27].

2.2. Function of Forensic Evidence and Its Restrictions

Forensic science has revolutionized contemporary criminal justice by offering objective means of connecting suspects to crime [28]. Physical and biological evidence, like DNA, hair, and body fluids, have long made prosecutors’ cases more powerful [29]. However, few, if any, sexual assault cases depend exclusively on DNA evidence [30]. This excessive dependence on physical evidence has also generated unrealistic hope among juries, resulting in what is so-called the “CSI effect”, where scientific evidence is overestimated and testimonial evidence is devalued [31].

High-tech forensic methods such as trace DNA and contact-based recovery techniques have enhanced detection sensitivity, but their use is still variable from one jurisdiction to another [32]. In addition, the lack of trained medical and forensic staff remains a hindrance to collecting and preserving evidence on time [33]. It is on this basis that these findings show a paradox: technological advancement increases the value of forensic evidence, but institutional constraints continue to limit its influence [34]. Thus, there is an increasing necessity for unifying evidentiary models that weigh scientific and circumstantial evidence without favoring one type of evidence over the other [35].

2.3. Psychological and Behavioral Evidence

A convergent body of evidence from psychology and neuroscience points to the impact of trauma and memory on witness credibility in sexual offense cases [36]. Psychological evidence indicates that trauma impacts recall, leading to delayed or dissociated disclosure that can be taken as dishonesty [37]. Some contend that stress-related distortion in memory complicates the consistency of testimony, rendering judicial interpretation challenging [38]. The convergence of these views signifies the challenge in translating psychological effects into the legal process.

Researchers have further revealed how implicit gender bias and myths influence juror judgments, frequently precipitating victim-blaming [39]. These biases exist in the face of common advocacy for trauma-informed interview practices aimed at assisting victims throughout the investigation and testimony [40]. There is consensus in the literature that without expert psychological testimony, jurors commonly misinterpret inconsistencies as fabrication instead of trauma-based responses [41]. Therefore, forensic psychology provides not only contextual insight but also evidentiary power, bridging interpretive gaps in the absence of physical evidence. Fewer empirical studies, however, are available to quantify how such testimony contributes to conviction rates—a central gap confronted by the current review [42].

2.4. Digital and Circumstantial Evidence as Emerging Alternatives

The increasing digitalization of communications has created new opportunities for collecting evidence in the prosecution of sexual crime [43]. Metadata, GPS data, and social-media activity can establish timelines, verify presence, and rebut assertions of consent [44]. Such digital trace evidence transcends the older forensic paradigms and has become critical to modern legal cases.

There are still issues with admissibility, chain of custody, and the technical proficiency of law enforcement officers [45]. In most instances, digital evidence’s potential is lost due to inappropriate handling or procedural ignorance. As much as its value is appreciated, there are a few systems that combine digital data with psychological or behavioral signs to create holistic prosecutorial strategies [45]. This underscores the pressing need for standard protocols and interdisciplinary training to make digital evidence more credible and acceptable in court.

In general, the study suggests that the successful prosecution of sexual offenses without physical evidence is contingent upon integrating forensic, psychological, and digital methods into a seamless legal framework [46]. Earlier research is likely to explore these components in a vertical fashion, without illustrating how they can coordinate to enhance prosecutorial evidence [47]. This review seeks to bridge that conceptual gap by integrating current findings, unearthing procedural and perceptual deficits, and suggesting integrative methods that promote conviction reliability despite the absence of physical evidence [48].

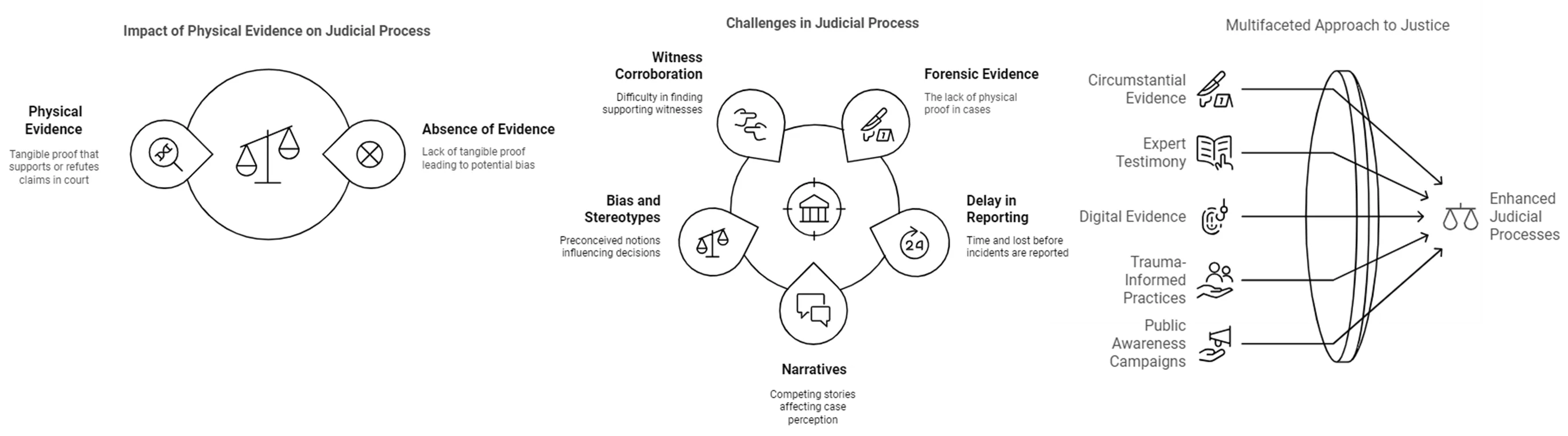

3. Challenges for the Prosecutor

3.1. Deficiency of Forensic Evidence

Physical evidence is the foundation of crime investigations, and the absence of such evidence weakens the prosecution’s argument. Physical evidence tends to explain how a crime occurred and identify and link a victim or a suspect to the scene of the crime [49]. It is also helpful in exonerating an innocent [50]. Physical injuries such as anal trauma, genital trauma, and traumatic lesions on the body, DNA evidence, and other identifiable markers are undeniable proof that a crime happened and ultimately provide a strong narrative for the jury to follow [51,52]. Popular media has shaped a perception that forensic evidence is a standard and essential component of criminal trials, so that an indirect approach may fall short of jury expectations [53,54,55].

The absence of physical evidence allows the defense to introduce reasonable doubt, which may be used to influence the jury. The defense might try to prove that the act was consensual or did not occur at all by arguing that there are no DNA or visible injuries [56]. This weakens the credibility of the prosecution’s case, highlighting the importance of other forms of evidence to fill this void.

Developments in forensic science are progressively addressing these challenges through innovative techniques to detect previously elusive forms of evidence. Investigators can now recover and analyze trace amounts of DNA left by mere contact with a surface due to the development of Touch DNA technology [56,57,58]. However, advancements in investigative tools, techniques, and methods offer hope. Detailed interpretation by experts and proactive education of jury members, ensuring that they understand the importance and limitations of such evidence, is needed to use innovative methods effectively.

3.2. Delay in Reporting of the Incident

Delayed reporting is a widespread issue in sexual crimes, deep-rooted in the profound emotional, psychological, and social challenges victims face [59]. Due to fear of judgment, potential revenge from their assailant, or societal humiliation, victims often delay coming forward to report. This hesitancy is intensified by the overwhelming trauma linked with the incident, leaving victims struggling with feelings of confusion, mistrust, and shame [60]. These delays result in the loss of important forensic evidence like bodily fluids, injuries, etc., which reduces the prosecution’s ability to establish a convincing timeline of events [61].

The psychological outcomes of trauma impact the reporting of a crime. Victims may internally self-blame or fear being ignored by authorities, which leads to silence [62]. This silence and delay in reporting are often misinterpreted by judges and jury members, who may wrongly associate the absence of timely disclosure with lying or fabrication. Such delusions can result in an unjust bias against victims, further complicating their search for justice.

3.3. Narratives

The absence of physical evidence often leads to the outcome that a court trial hinges on the perceived integrity of the victim’s testimony against that of the accused. Situations like “she-said or he-said” present a challenge as jury members assess contradictory narratives without corroborative evidence [63]. This dependence on subjective evaluations can result in acquittal if the defense effectively establishes reasonable doubt.

3.4. Bias and Stereotypes

Biases and stereotypes significantly influence judicial outcomes in sex crime cases, often to the detriment of fairness [64,65,66,67]. Jurors frequently hold preconceived notions about how a real victim should act, expecting behaviors such as visible emotional distress, immediate reporting of the crime, or consistent accounts of the incident [68]. When victims deviate from these expectations, perhaps due to trauma, fear, or other personal reasons, their credibility is unfairly called into question, diminishing the strength of their testimony [69].

Similarly, stereotypes about offenders can shape case outcomes. Defendants who do not conform to the perceived image of a typical sex offender, whether due to their demeanor, appearance, or social standing, often benefit from implicit biases. These biases can make jurors less inclined to believe the accusations against them, creating an uneven playing field [70,71]. For example, individuals perceived as respected community members, professionals, or those with no prior criminal history may be viewed as less likely to commit such crimes, regardless of the evidence presented.

3.5. Absence of Witness Corroboration

In the majority of cases involving sexual crimes, the sole witness is the victim, which makes corroboration of their account nearly impossible [72]. The prosecution’s case rests on the narrative of the victim in the absence of supporting testimony and physical evidence [73]. This creates vulnerabilities as a defense strategy targeting to undermine the credibility of the victim by highlighting discrepancies in their account or aggressively conducting cross-examination [74].

The lack of corroborative evidence puts significant pressure on victims to recount events with absolute accuracy, even during the intense stress of courtroom proceedings [75,76]. However, the conditions through which the victim suffered can affect the recall of memories, which leads to inconsistent or fragmented details [77,78,79]. Instead of understanding these inconsistencies as a result of trauma, they are often used to discredit the victim. This weakens the case and creates more emotional discomfort for the victim.

4. Strategies to Address Challenges

4.1. Behavioral and Circumstantial Evidence

The behavior of the victim after the incident, digital communication, or social media activity often holds a pivotal role in sexual crime incidents where physical evidence is not present [80,81]. This kind of evidence can provide vital context in assisting the jury members to understand the dynamics of criminal activity and the relationship between the perpetrator and the victim. For instance, behavioral evidence such as patterns of coercion, intimidation, grooming, or manipulation can demonstrate the power imbalance at play and provide a clear image of the events leading up to and following the incident.

Prosecutors may utilize circumstantial evidence in their strategies to strengthen cases. Emails, text messages, or social media communications exchanged before and after the crime can disclose the offender’s intent, the victim’s lack of consent, and efforts to control or threaten the victim [82]. Behavioral experts can offer expertise to describe why victims may show reactions that the jury might find counterintuitive, like the absence of visible distress, delay in reporting, or continued communication with the offender [83]. These insights help fill the gap between the psychological realities of trauma and jury expectations.

Dejong and Rose [84] reviewed 115 cases of child sexual assault with convictions. Only 23% of all cases have physical evidence. Among 85 cases without physical evidence, in 67 cases the criminals were convicted. The successful prosecution in these cases results from the quality of verbal evidence and the effectiveness of the victim’s testimony.

4.2. Forensic Psychology

Forensic psychology has significantly developed the understanding of trauma and its profound effects on victims of sexual crime and violence [85]. Investigators and legal professionals can create a safe environment that reduces retraumatization by using trauma-informed interviewing techniques. These methods are intended to aid victims in recalling details of the incident more effectively. This results in testimonies that are both consistent and coherent, thus consolidating the case of prosecution.

Psychologists play an important role as expert witnesses in court trials by providing insights into trauma responses like dissociation, memory fragmentation, or the freeze reaction during or after a sexual assault [86]. The psychological assessments of the accused or suspect can reveal behavioral patterns consistent with profiles of known sexual offenders.

4.3. Digital Evidence

In today’s digital age, electronic evidence has become a key factor in prosecuting sex crimes, offering critical information that can validate victim accounts and provide a comprehensive timeline of events [87]. Different forms of digital communications, such as text messages, emails, and social media interactions, often disclose patterns that can establish the intent of the perpetrator and directly counter claims of consensual activity, such as threatening messages sent before or after the incident, which can determine a calculated effort to intimidate and silence the victim [88].

Besides direct communication, digital evidence consists of metadata such as device usage logs, geolocation data, and timestamps [89]. This kind of evidence can confirm the presence of both the victim and offender at specific locations, providing a form of corroboration that strengthens the prosecution’s case in the absence of physical evidence.

The effective usage of digital evidence in court trials depends on rigorous adherence to legal protocols for its collection, preservation, and presentation. Any mismanagement or apparent tampering can pave the way for defense challenges, leading to a decline in admissibility [90]. Therefore, law enforcement personnel and legal experts require specialized training to guarantee the legitimacy and integrity of digital evidence. This consists of understanding chain-of-custody protocols, using forensic tools to excerpt data, and presenting findings in a way that is acceptable and understandable by the jury.

4.4. Expert Witness

Expert witnesses play an important part in presenting complex scientific, psychological, and legal concepts in a way understandable to jurors. Their testimony clarifies misconceptions and increases the credibility of the victim’s claims [91]. In the same way, forensic analysts contribute by interpreting circumstantial evidence, such as digital traces, patterns of communication, or behavioral dynamics, to explain the comprehensive framework of the crime [92]. Such analysis and expert testimony can help shift the focus of the jury from the lack of physical evidence to a wide-ranging view of the case, highlighting intent and patterns over tangible proof.

The influence of expert testimony depends profoundly on how it is presented. Experts must extract complex information into clear, relatable explanations that are understandable to a common audience [93]. Ambiguous interpretations and excessive usage of technical language can decrease the effectiveness. To ensure desired results, experts should directly address the misunderstandings the jury might hold.

5. Discussion

Prosecuting sexual crimes without physical evidence demands a multifaceted approach that links the gap between legal strategy, psychological insight, and juror perception. The neoteric literature underscores that trauma has an acute influence on victim memory and reporting patterns, which can be misinterpreted as inconsistencies in testimony [15,94]. Preparation for courtroom testimony and trauma-informed interviewing can help mitigate these misunderstandings, thus enhancing credibility in the eyes of the jury.

Non-physical evidence can be powerful when presented cohesively. Eyewitness statements, digital communications, timelines, and the defendant’s contradictory statements can serve as corroborative elements. Expert testimony explaining the neurobiology of trauma helps jurors understand victims’ behavior, for example, fragmented recall or delayed reporting that might be taken suspiciously [95].

Bias reduction is a serious component. Research on rape myths and DARVO reveals that justice professionals may instinctively adopt misconceptions that shift blame from the perpetrator to the victim. Specialized training for prosecutors and investigators can counter these biases and encourage evidence-driven decision-making. Employing trauma-informed practices in judicial processes and law enforcement organizations is important to addressing the exceptional requirements of sexual crime victims and guaranteeing a more unbiased justice system [25]. These practices are grounded in an understanding of the psychological effects of trauma, which can greatly influence how victims communicate, recall, and respond to their experiences. By doing so, trauma-informed methods aim to reduce traumatic influence and improve the accuracy and reliability of victim participation.

Officers trained in these practices understand how trauma affects memory and behavior, allowing them to establish safe and supportive surroundings for victims. They may ask open-ended questions, allow more time for responses, and avoid leading or harsh, accusatory language and words. This approach makes victims feel heard and respected and enables the collection of detailed and accurate accounts necessary for building a strong case [96].

In judicial settings, measures like allowing the victim to give testimony via video link, using protective screens, or limiting face-to-face confrontation with the accused can reduce the stress and anxiety related to court appearances. This recognizes the emotional toll of reliving traumatic experiences in an adversarial and public setting, helping victims provide consistent and clearer testimony.

Beyond adaptations in procedures, trauma-informed practices also signal institutional empathy and foster trust in the justice system. Victims whose experiences are taken seriously and handled sensitively are likelier to come forward, cooperate with investigations, and remain involved throughout the legal process.

Special training for judges, both prosecutors and defense attorneys, is crucial to guarantee that sexual crime incidents are dealt with fairness, sensitivity, and with a complete understanding of their complexities. Such training should address critical areas such as dismantling common biases and myths about sexual violence and victims, considering trauma-related behaviors, and recognizing the evidentiary value of non-physical proof and evidence. This way, courtrooms can provide a more equitable dynamic, ensuring that victims are treated with respect while giving the jury precise, science-based information to guide their decisions.

Interdisciplinary collaboration between forensic scientists, legal experts, and psychologists can improve case preparation and the presentation of evidence. Forensic scientists can analyze and provide information from digital or circumstantial evidence, whereas psychologists can clarify trauma responses and behavioral patterns during trials.

Extensive societal change is important to eradicate the stigma around sexual violence and create an environment where victims can be supported in seeking justice. An important aspect of this change lies in public awareness campaigns intended to educate communities about the realities of sexual violence, the impacts of trauma, and the importance of victim testimony. These campaigns should address misconceptions that undermine a victim’s credibility, thereby reducing the prevalence of victim-blaming during investigations and trials.

Along with public education, integration of consent education and spectator intervention training into school curricula can nurture a culture of respect and accountability from a young age. Teaching students about affirmative consent, healthy relationships, and the dynamics of power and coercion helps them identify and challenge harmful behaviors. Spectator intervention training empowers individuals to step in and handle potentially dangerous circumstances, creating safer communities.

International and domestic multidisciplinary models demonstrate that collaborative efforts among forensic scientists, law enforcement, prosecutors, and victim advocates can greatly enhance investigative thoroughness and increase conviction rates [96,97]. These models show that coordinated case management, even in the absence of physical evidence, increases the chances of a successful prosecution.

These efforts can normalize conversations about sexual mishaps, encouraging individuals to report incidents and seek out help without any fear of judgment. When combined with trauma-informed legal and judicial practices, societal change driven by education and awareness can establish a healthy support system for victims and survivors while promoting prevention and accountability.

6. Conclusions

Prosecuting sex crimes without physical evidence is certainly challenging, but it is far from impossible. Through innovative approaches and systemic improvements, the judicial system can address these complications and improve consequences for survivors. Leveraging circumstantial and behavioral evidence allows prosecutors to present a complete picture of the crime. Expert witnesses, including forensic psychologists and analysts, play a crucial role in contextualizing and explaining trauma responses, interpreting non-physical evidence for the jury, and victim behavior. Using trauma-informed practices ensures that victims are treated with dignity and that they are heard in a supportive and fair environment. Legal reforms and public awareness initiatives challenge societal biases, reduce stigma, and encourage victims to report crimes. Balancing the pursuit of justice for victims with the protection of the rights of the accused requires an evidence-based approach rooted in empathy and education. Further progress in legal practices, forensic science, and societal attitudes can help alleviate the barriers posed by the absence of physical evidence. Hence, the judicial system can ensure that survivors of sexual abuse and violence receive the justice and support they deserve while upholding equity and fairness for both the victim and the accused.

Author Contributions

H.U.R.: Writing—original draft. A.A.: Writing—review & editing. Z.S.: Literature review, Writing—review & editing, Visualization. H.M.A.M.: Supervision, Critical revision of the manuscript. M.I.: Writing—review & editing, Critical revision of the manuscript. H.F.: Writing—review & editing, Critical revision of the manuscript. R.U.: Literature review, Writing—review & editing. M.S.C.: Supervision, Validation. U.K.: Writing—review & editing. A.B.: Writing—review & editing. M.M.: Writing—review & editing.

Ethics Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

-

About Sexual Assault|RAINN. 2024. Available online: https://rainn.org/about-sexual-assault (accessed on 5 January 2025). [Google Scholar]

-

World Health Organization. Violence Against Women; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/violence-against-women (accessed on 5 January 2025). [Google Scholar]

-

Peterson JL, Hickman MJ, Strom KJ, Johnson DJ. Effect of forensic evidence on criminal justice case processing. J. Forensic Sci. 2013, 58 (Suppl. S1), S78–S90. doi:10.1111/1556-4029.12020. [Google Scholar]

-

Husan S. Role of Forensic Evidence in the Criminal Investigation: A Legal Analysis in Bangladesh Perspective. Tradit. J. Law Soc. Sci. 2022, 1, 181–192. [Google Scholar]

-

Overview of Criminal Justice System (CJS) in Pakistan, Research Society of International Law|RSIL. Available online: https://rsilpak.org/resource-bank-pakistans-criminal-justice-system/overview-of-criminal-justice-system-cjs-in-pakistan/ (accessed on5 January 2025). [Google Scholar]

-

Office on Violence Against Women (OVW)|Framework for Prosecutors to Strengthen Our National Response to Sexual Assault and Domestic Violence Involving Adult Victims. 2024. Available online: https://www.justice.gov/ovw/framework-prosecutors-strengthen-our-national-response-sexual-assault-and-domestic-violence (accessed on 7 January 2025). [Google Scholar]

-

Punjab Forensic Science Agency. Available online: https://pfsa.punjab.gov.pk/faq (accessed on 6 January 2025). [Google Scholar]

-

Dintwe SI. The Significance of Biological Exhibits in Investigation of Rape Cases. 2009. Available online: https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi=598958d86501fddf66154451b161a10f1acae352 (accessed on7 January 2025). [Google Scholar]

-

World Health Organization. Guidelines for Medico-Legal Care for Victims of Sexual Violence; World Health Organization: France 2003. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/42788/924154628X.pdf (accessed on 8 January 2023). [Google Scholar]

-

Cattaneo C, Tambuzzi S, De Vecchi S, Maggioni L, Costantino G. Consequences of the lack of clinical forensic medicine in emergency departments. Int. J. Leg. Med. 2024, 138, 139–150. doi:10.1007/s00414-023-02973-8. [Google Scholar]

-

Tidmarsh P, Hamilton G. Trends & Issues in Crime and Criminal Justice Misconceptions of Sexual Crimes Against Adult Victims: Barriers to Justice. 2020. Available online: https://www.aic.gov.au/sites/default/files/2020-11/ti611_misconceptions_of_sexual_crimes_against_adult_victims.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2025). [Google Scholar]

-

Trafficking in Persons & Smuggling of Migrants Module 9 Key Issues: Challenges to an Effective Criminal Justice Response. 2019. Available online: https://www.unodc.org/e4j/en/tip-and-som/module-9/key-issues/challenges-to-an-effective-criminal-justice-response.html (accessed on 16 January 2025). [Google Scholar]

-

Willmott D, Boduszek D, Debowska A, Hudspith L. Jury Decision-making in Rape Trials. Forensic Psychol. Edition 3 2021, 94–119. doi:10.1002/9781394260669.ch5. [Google Scholar]

-

Saks MJ, Koehler JJ. The Coming Paradigm Shift in Forensic Identification Science. Science 2005, 309, 892–895. doi:10.1126/science.1111565. [Google Scholar]

-

Haskell L, Randall M. The Impact of Trauma on Adult Sexual Assault Victims; Department of Justice Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2019. Available online: https://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/rp-pr/jr/trauma/trauma_eng.pdf (accessed on 13 January 2025). [Google Scholar]

-

Shahali S, Mohammadi E, Lamyian M, Kashanian M, Eslami M, Montazeri A. Barriers to Healthcare Provision for Victims of Sexual Assault: A Grounded Theory Study. Iran. Red Crescent Med. J. 2016, 18, e21938. doi:10.5812/ircmj.21938. [Google Scholar]

-

Krahé B. Social Psychological Issues in the Study of Rape. Eur. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 1991, 2, 279–309. doi:10.1080/14792779143000097. [Google Scholar]

-

Strom K, Scott T, Feeney H, Young A, Couzens L, Berzofsky M. How much justice is denied? An estimate of unsubmitted sexual assault kits in the United States. J. Crim. Justice 2021, 73, 101746. doi:10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2020.101746. [Google Scholar]

-

Almutairi HA, Almesawa IH, Alhazmy TI, Alrehaili AA, Alsharif MM, Alharbi AA. The Role of Laboratory-Based Theories in Enhancing Forensic Evidence Interpretation. J. Int. Crisis Risk Commun. Res. 2024, 7 (Suppl. S7), 784. [Google Scholar]

-

Borysenko IV, Bululukov OY, Pcholkin VD, Baranchuk VV, Prykhodko VO. The modern development of new promising fields in forensic examinations. J. Forensic Sci. Med. 2021, 7, 137–144. [Google Scholar]

-

Higgs S, Cooper A, Lee J. Biological Psychology; SAGE: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

-

van Zandwijk JP, Boztas A. Digital traces and physical activities: Opportunities, challenges and pitfalls. Sci. Justice 2023, 63, 369–375. [Google Scholar]

-

Khan AS, Bibi A, Khan A, Ahmad I. Responsibility of Sexual Violence Under International Law. J. Soc. Sci. Rev. 2023, 3, 29–41. [Google Scholar]

-

Quénivet N. Sexual Offenses in Armed Conflict and International Law; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2021; Volume 19. [Google Scholar]

-

Spohn C. Sexual assault case processing: The more things change, the more they stay the same. Int. J. Crime Justice Soc. Democr. 2020, 9, 86–94. [Google Scholar]

-

Cullen O, Ernst KZ, Dawes N, Binford W, Dimitropoulos G. “Our laws have not caught up with the technology”: Understanding challenges and facilitators in investigating and prosecuting child sexual abuse materials in the United States. Laws 2020, 9, 28. [Google Scholar]

-

Cashmore J, Taylor A, Parkinson P. Fourteen-year trends in the criminal justice response to child sexual abuse reports in New South Wales. Child Maltreat. 2020, 25, 85–95. [Google Scholar]

-

Stolzenberg L, D’Alessio SJ. Crime Science: Modern Technologies to Combat Crime; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2025. [Google Scholar]

-

Rajput H. Biological evidence for crime investigation. J. Digit. Secur. Forensics 2024, 1, 34–52. [Google Scholar]

-

Sijen T, Harbison S. On the identification of body fluids and tissues: a crucial link in the investigation and solution of crime. Genes 2021, 12, 1728. [Google Scholar]

-

Alderden M, Cross TP, Vlajnic M, Siller L. Prosecutors’ perspectives on biological evidence and injury evidence in sexual assault cases. J. Interpers. Violence 2021, 36, 3880–3902. [Google Scholar]

-

Thurow K, Junginger S. Devices and Systems for Laboratory Automation; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

-

Noor A, Raza A, Rehman FU. Recent advances in forensic science for evidence collection and preservation: Innovations in sample handling techniques to enhance analytical accuracy and case-specific investigations. Forensic Insights Health Sci. Bull. 2024, 2, 60–66. [Google Scholar]

-

De Oliveira Musse J, Santos VS, da Silva Santos D, Dos Santos FP, de Melo CM. Preservation of forensic traces by health professionals in a hospital in Northeast Brazil. Forensic Sci. Int. 2020, 306, 110057. [Google Scholar]

-

Ali Shah SA, Hussain B. Challenges faced by police officers in forensic criminal investigation a case study of district Peshawar, Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa. Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa 2020, 13, 51-65. [Google Scholar]

-

Paulson T, Perrin B, Maunder RG, Muller RT. Toward a trauma-informed approach to evidence law: Witness credibility and reliability. Can. B. Rev. 2023, 101, 496. [Google Scholar]

-

Ward CV. Trauma and Memory in the Prosecution of Sexual Assault. Law Psychol. Rev. 2020, 45, 87. [Google Scholar]

-

Reddy KJ. Witness Testimony and Memory. In Foundations of Criminal Forensic Neuropsychology: Bridging Mind, Law, and Criminal Justice; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 379–428. [Google Scholar]

-

Kan CH. The examination of neuroscientific evidence in the criminal trial process: The importance of collaboration between criminal law and neuroscience. Int. J. Eurasia Soc. Sci./Uluslar. Avrasya Sos. Bilim. Derg. 2025, 16, 511. [Google Scholar]

-

Pozzulo J, Pica E, Sheahan C. Memory and Sexual Misconduct: Psychological Research for Criminal Justice; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

-

Dodier O, Barzykowski K, Souchay C. Recovered memories of trauma as a special (or not so special) form of involuntary autobiographical memories. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1268757. [Google Scholar]

-

Salerno JM. The impact of experienced and expressed emotion on legal factfinding. Annu. Rev. Law Soc. Sci. 2021, 17, 181–203. [Google Scholar]

-

Rumney P, McPhee D. The evidential value of electronic communications data in rape and sexual offence cases. Crim. Law Rev. 2020, 1, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

-

Hellwig K. The potential and the challenges of digital evidence in international criminal proceedings. Int. Crim. Law Rev. 2021, 22, 965–988. [Google Scholar]

-

D’Alessandra F, Sutherland K. The promise and challenges of new actors and new technologies in international justice. J. Int. Crim. Justice 2021, 19, 9–34. [Google Scholar]

-

George AS. Virtual violence: Legal and psychological ramifications of sexual assault in virtual reality environments. Partn. Univers. Int. Innov. J. 2024, 2, 96–114. [Google Scholar]

-

Cinelli R. Paradigms of Evidence. Reframing Forensic Images through Extended Reality Media. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Milan, Milan, Italy, 2025. [Google Scholar]

-

Jetten K. A Contextual Inquiry Approach to Improving DNA Service Delivery in Sexual Assault Investigations. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Portsmouth, Portsmouth, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

-

Kanatbekuly Z, Seitzhanov O, Darmenov A. Physical Evidence in the Pre-Trial Investigation of Murders Involving Rape or Violent Acts of a Sexual Nature. Med. Law 2022, 41, 351–368. [Google Scholar]

-

Kuppuswamy R. Physical Evidence—Its Use in the Investigation of Crime. Aust. Police J. 1981, 35, 181–184. [Google Scholar]

-

Goodman-Delahunty J, Hewson L. Technical and Background Paper Improving Jury Understanding and Use of Expert DNA Evidence. 2010. Available online: https://www.aic.gov.au/sites/default/files/2020-05/tbp037.pdf (accessed on 12 October, 2025). [Google Scholar]

-

Manzoor I, Hashmi NR, Mukhtar F. Medico-legal Aspects of Alleged Rape Victims in Lahore. J. Coll. Physicians Surg. Pak. 2010, 20, 785–789. [Google Scholar]

-

Kaplan J, Ling S, Cuellar M. Public Beliefs about the Accuracy and Importance of Forensic Evidence in the United States. Sci. Justice 2020, 60, 263–272. doi:10.1016/j.scijus.2020.01.001. [Google Scholar]

-

Peterson J, Sommers I, Baskin D, Johnson D. The Role and Impact of Forensic Evidence in the Criminal Justice Process. Natl. Inst. Justice 2010, 1, 1–151. [Google Scholar]

-

Green E. The Importance of Forensic Evidence in Criminal Investigations and Trials, Starleaf Blog. 2024. Available online: https://www.starleaf.com/blog/the-importance-of-forensic-evidence-in-criminal-investigations-and-trials/ (accessed on 14 October 2025). [Google Scholar]

-

Lawson TF. Before the Verdict and beyond the Verdict: The CSI Infection within Modern Criminal Jury Trials. Loy. U. Chi. LJ. 2009, 41, 119. [Google Scholar]

-

Aditya S, Sharma AK, Bhattacharyya CN, Chaudhuri K. Generating STR profile from “Touch DNA”. J. Forensic Leg. Med. 2011, 18, 295–298. doi:10.1016/j.jflm.2011.05.007. [Google Scholar]

-

Sessa F, Salerno M, Bertozzi G, Messina G, Ricci P, Ledda C, et al. Touch DNA: Impact of handling time on touch deposit and evaluation of different recovery techniques: An experimental study. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 9542. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-46051-9. [Google Scholar]

-

Jessica. Why do Women Wait to Report Sexual Assault & Rape? Aspire Counseling. (n.d.). Available online: https://aspirecounselingmo.com/blog/women-wait-report-sexual-assault-rape (accessed on 14 June 2025). [Google Scholar]

-

Shame, Stigma Integral to Logic of Sexual Violence as War Tactic, Special Adviser Tells Security Council, as Speakers Demand Recognition for Survivors|UN Press. 2017. Available online: https://press.un.org/en/2017/sc12819.doc.htm (accessed on 19 May 2024). [Google Scholar]

-

Zia M, David SO, Randhawa S. Gap Analysis on Investigation and Prosecution of Rape and Sodomy Cases, Legal Aid Society. 2021. Available online: https://www.las.org.pk/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Gap-Analysis-on-Investigation-and-Prosecution-of-Rape-and-Sodomy-Cases-R.pdf (accessed on 12 May 2025). [Google Scholar]

-

Miller AK, Handley IM, Markman KD, Miller JH. Deconstructing Self-Blame Following Sexual Assault: The Critical Roles of Cognitive Content and Process. Violence Against Women 2010, 16, 1120–1137. doi:10.1177/1077801210382874. [Google Scholar]

-

Connolly DA, Gordon HM. He-said-she-said: Contrast effects in credibility assessments and possible threats to fundamental principles of criminal law. Leg. Criminol. Psychol. 2011, 16, 227–241. doi:10.1348/135532510x498185. [Google Scholar]

-

Cusack S. Eliminating Judicial Stereotyping. Equal Access to Justice for Women in Gender-Based Violence Cases. 2014. Available online: https://rm.coe.int/1680597b20 (accessed on 15 January 2025). [Google Scholar]

-

Tyagi K. Gender Bias in the Criminal Justice System: Analyzing the Treatment of Female Offenders in India. Int. J. Multidiscip. Res. 2024, 6. doi:10.36948/ijfmr.2024.v06i06.31306. [Google Scholar]

-

Huhtanen H. Gender Bias in Sexual Assault Response and Investigation. Part 1: Implicit Gender Bias. End Violence against Women International. 2022. Available online: https://evawintl.org/wp-content/uploads/TB-Gender-Bias-1-4-Combined-1.pdf (accessed on 15 April 2025). [Google Scholar]

-

Sorby M, Kehn A. Juror perceptions of the stereotypical violent crime defendant. Psychiatry Psychol. Law 2020, 28, 645–664. doi:10.1080/13218719.2020.1821827. [Google Scholar]

-

Leverick F. What do we know about rape myths and juror decision making? Int. J. Evid. Proof 2020, 24, 136571272092315. doi:10.1177/1365712720923157. [Google Scholar]

-

Grubb A, Turner E. Attribution of Blame in Rape cases: A Review of the Impact of Rape Myth acceptance, Gender Role Conformity and Substance Use on Victim Blaming. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2012, 17, 443–452. doi:10.1016/j.avb.2012.06.002. [Google Scholar]

-

Cooke LN. Boy v. man: The role of perception and the attribution of blame in court proceedings. Heliyon 2023, 9, e18116. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e18116. [Google Scholar]

-

Yang Q, Zhu B, Zhang Q, Wang Y, Hu R, Liu S, et al. Effects of Male Defendants’ Attractiveness and Trustworthiness on Simulated Judicial Decisions in Two Different Swindles. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 2160. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02160. [Google Scholar]

-

Huda T. “No signs of rape”: Corroboration, resistance and the science of disbelief in the medico-legal jurisprudence of Bangladesh. Sex. Reprod. Health Matters 2022, 29, 2096186. doi:10.1080/26410397.2022.2096186. [Google Scholar]

-

Conviction in Rape Cases: The Significance of Victims Statements recorded under Section 164 CrPC. 2024. Available online: https://articles.manupatra.com/article-details/Conviction-in-Rape-Cases-The-Significance-of-Victims-Statements-recorded-under-Section-164-CrPC (accessed on 16 April 2025). [Google Scholar]

-

Wolf K. Cross-Examination Mastery: Strategies for Challenging Witness Credibility and Exposing Inconsistencies, Filevine. 2024. Available online: https://www.filevine.com/blog/cross-examination-mastery-strategies-for-challenging-witness-credibility-and-exposing-inconsistencies/ (accessed on 6 April 2025). [Google Scholar]

-

Howe ML, Knott LM. The fallibility of memory in judicial processes: Lessons from the past and their modern consequences. Memory 2015, 23, 633–656. doi:10.1080/09658211.2015.1010709. [Google Scholar]

-

Lacy JW, Stark CEL. The neuroscience of memory: Implications for the courtroom. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2013, 14, 649–658. doi:10.1038/nrn3563. [Google Scholar]

-

Bedard-Gilligan M, Zoellner LA. Dissociation and memory fragmentation in post-traumatic stress disorder: An evaluation of the dissociative encoding hypothesis. Memory 2012, 20, 277–299. doi:10.1080/09658211.2012.655747. [Google Scholar]

-

Strange D, Takarangi MKT. Memory Distortion for Traumatic Events: The Role of Mental Imagery. Front. Psychiatry 2015, 6, 27. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2015.00027. [Google Scholar]

-

Brewin CR. Memory and Forgetting. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2018, 20, 87. doi:10.1007/s11920-018-0950-7. [Google Scholar]

-

Klasén L, Fock N, Forchheimer R. The invisible evidence: Digital forensics as key to solving crimes in the digital age. Forensic Sci. Int. 2024, 362, 112133. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2024.112133. [Google Scholar]

-

The Role of Digital Forensics in Sex Crime Cases. Law Offices of John D. Rogers. 2024. Available online: https://johndrogerslaw.com/the-role-of-digital-forensics-in-sex-crime-cases/ (accessed on 20 April 2025). [Google Scholar]

-

O’Malley RL, Holt KM. Cyber Sextortion: An Exploratory Analysis of Different Perpetrators Engaging in a Similar Crime. J. Interpers. Violence 2020, 37, 088626052090918. doi:10.1177/0886260520909186. [Google Scholar]

-

Singh A, Morrison BW, Morrison NMV. Psychologist attitudes towards disclosure and believability of childhood sexual abuse: Can biases affect perception, judgement, and action? Child Abus. Negl. 2023, 146, 106506. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2023.106506. [Google Scholar]

-

De Jong AR, Rose M. Legal proof of child sexual abuse in the absence of physical evidence. Pediatrics 1991, 88, 506–511. [Google Scholar]

-

Patisina, Kian AML, See BR. The Contribution of Forensic Psychology to Improve the Protection of Rape Victims in Trials. Formosa J. Multidiscip. Res. 2024, 3, 15–34. doi:10.55927/fjmr.v3i4.8983. [Google Scholar]

-

Dalenberg CJ, Straus E, Ardill M. Forensic psychology in the context of trauma. In APA Handbook of Trauma Psychology: Trauma Practice; Gold SN, Ed.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2017; pp. 543–563. doi:10.1037/0000020-026. [Google Scholar]

-

Dodge A. The digital witness: The role of digital evidence in criminal justice responses to sexual violence. Fem. Theory 2017, 19, 303–321. doi:10.1177/1464700117743049. [Google Scholar]

-

Dragiewicz M, Burgess J, Matamoros-Fernández A, Salter M, Suzor NP, Woodlock D, et al. Technology facilitated coercive control: domestic violence and the competing roles of digital media platforms. Fem. Media Stud. 2018, 18, 609–625. doi:10.1080/14680777.2018.1447341. [Google Scholar]

-

Nishchal S. Forensic Analysis of WhatsApp: A Review of Techniques, Challenges, and Future Directions. J. Forensic Sci. Res. 2024, 8, 9–24. doi:10.29328/journal.jfsr.1001059. [Google Scholar]

-

Granja FM, Rafael GDR. The preservation of digital evidence and its admissibility in the court. Int. J. Electron. Secur. Digit. Forensics 2017, 9, 1–18. doi:10.1504/ijesdf.2017.081749. [Google Scholar]

-

Long JG. Introducing Expert Testimony to Explain Victim Behavior in Sexual and Domestic Violence Prosecutions; National District Attorneys Association: Arlington, Virginia, 2007. Available online: https://www.forensichealth.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/pub_introducing_expert_testimony.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2025). [Google Scholar]

-

Horan J, Goodman-Delahunty J. Expert Evidence to Counteract Jury Misconceptions About Consent in Sexual Assault Cases: Failures and Lessons Learned. 2020. Available online: https://www.austlii.edu.au/cgi-bin/viewdoc/au/journals/UNSWLawJl/2020/24.html (accessed on 15 July 2025). [Google Scholar]

-

Schuller RA, Terry D, McKimmie B. The Impact of Expert Testimony on Jurors’ Decisions: Gender of the Expert and Testimony Complexity. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2005, 35, 1266–1280. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.2005.tb02170.x. [Google Scholar]

-

Tiry E, Zweig J, Walsh K, Farrell L, Yu L. Beyond forensic evidence: Examining sexual assault medical forensic exam mechanisms that influence sexual assault case outcomes. J. Interpers. Violence 2020, 37, 088626052096187. doi:10.1177/0886260520961870. [Google Scholar]

-

National Institute of Justice. “Untested Evidence in Sexual Assault Cases”. 17 March 2016. Available online: https://nij.ojp.gov/topics/articles/untested-evidence-sexual-assault-cases (accessed on 9 May 2025). [Google Scholar]

-

Haworth K. Police interviews in the judicial process. In The Routledge Handbook of Forensic Linguistics, 2nd ed.; Coulthard M, May A, Sousa-Silva R, Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2020. doi:10.4324/9780429030581. [Google Scholar]

-

Campbell R, Fehler-Cabral G, Pierce S, Sharma D, Bybee D, Shaw J, et al. The Detroit Sexual Assault Kit (SAK) Action Research Project (ARP), Final Report; National Institute of Justice: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. Available online: https://www.ojp.gov/pdffiles1/nij/grants/248680.pdf (accessed on 22 May 2025). [Google Scholar]