2.1. The Savannah Paradigm

It is of utmost importance to briefly recapitulate the origin and evolution of the currently dominant paradigms of hominin evolution, to understand how australopithecines came to be considered unquestionably as our closest relatives and direct ancestors. We consider the inclusion of a historical review as essential to understanding not only the origin of the savannah paradigm, which claims that our ancestors became bipedal as an adaptation to increasingly open savannah, but also how this hypothesis was at the basis of the paradigm that the bipedal australopithecines are our ancestors. Moreover, both paradigms reinforce each other.

Ever since we started thinking about the origin of our species from an evolutionary perspective [

37], the same lines of reasoning have been adopted. The savannah paradigm is based on a series of assumptions that once appeared straightforward (parsimonious), and which were already used by Lamarck, Darwin and Wallace.

These lines of reasoning are briefly summarized below:

1. Among extant primates, only our species shows obligate orthograde bipedal locomotion. Therefore, bipedality, considered as a unique trait for our genus, must have evolved after the split between our closest relatives and the genera

Pan and

Gorilla.

2. Both

Pan and

Gorilla knuckle-walk. Therefore, it is most parsimonious to assume that the last common ancestor of

Homo,

Pan and

Gorilla, and consequently the last common ancestor of

Homo and

Pan, was a semi-erect, quadrupedal, knuckle-walking ape with an ape-sized brain.

3. A knuckle-walking ancestor makes sense, since knuckle-walking by apes can be understood as a locomotor behavior that is intermediate between full arboreal quadrupedality, as in monkeys, and fully obligate bipedality, as in humans. This is further corroborated by the observation that

Pan and

Gorilla already live on the forest floor to a certain extent. This conviction is reflected by the numerous versions of the popular and ubiquitous image showing the “progression” from a quadrupedal monkey into fully upright Man via a semi-erect knuckle-walking chimpanzee.

4. For a vertebrate animal, it is most unusual to walk upright on hind legs. Since our species is not arboreal, but terrestrial, this bipedal gait must be an adaptation to living on the ground.

5. Overall, primates are folivorous and fructivorous. It seems rather odd, therefore, that a primate should be ground-dwelling, where leaves and fruit are rare. Consequently, living on the ground was most probably forced upon our ancestors by environmental changes, whereby forests were replaced by open habitats in the regions where our ancestors lived, causing the split of the hominin and panin lineages.

6. All other specifically human characteristics can be best explained as consequences of our upright posture and gait, which freed our forelimbs (hands), which led to increased manual dexterity, which enabled tool (and weapon) production and use, which improved hunting by running over the savannah, which increased the consumption of energy-rich meat, which led to brain size increase, which enabled articulate language.

In summary, the dominant paradigm states that our ancestors were forced to adapt to life on open plains, as caused by climate change, that they did so by walking/running on hind legs and that our obligate bipedalism explains how we became human e.g., [

2,

6].

This story of human evolution, as first envisioned in the absence of relevant fossil evidence or knowledge regarding paleo-climatology, is considered by some to be adequate. For example, Ernst Mayr [

38] found Lamarck’s hypothesis “startlingly modern”. More recently, it was stated that “Lamarck’s view is modern in that it is fairly close to what we believe today to be true.” [

39].

The discovery of australopithecine fossils in southern and eastern Africa, from 1925 onwards, fit perfectly within this scenario. The southern and eastern African landscapes were assumed to have been open savannah at the time of fossilization, and moreover these were locations where no extant ape species live. This lent further weight to the argument that orthograde bipedalism evolved as a means to survive in open habitats, and to the conviction that bipedalism was the hallmark of humanity, which in itself became the major driver for the development of most other typical human characteristics, such as loss of fur, manual dexterity (tool use) and an extremely large brain.

Most importantly, in the context of the present argument, the notion that australopithecines must be our ancestors gained acceptance because it is the most plausible assumption, in view of the above scenario. Still today, it is almost self-evident, and therefore still generally accepted, that the African bipedal and ape-size brained australopithecines, the genera

Australopithecus and

Paranthropus, existing in Africa between 4.2 Ma and 0.7 Ma, must have been intermediate in the evolutionary transition from a knuckle-walking ape ancestor with a small brain to an obligate, orthograde bipedal and large(r)-brained member of the genus

Homo.

2.2. The Dominant Savannah Paradigm Stems from Parsimonious Reasoning Prior to the Discovery of the First Australopithecine Fossil: 1809–1925

Bender et al. [

23] reviewed the history of the origin and evolution of the dominant paradigm. The review was co-authored by Phillip V. Tobias, the direct successor in the chair of Raymond Dart (University Witwatersrand, South-Africa) and the custodian of the world’s largest collection of

A. africanus specimens. As mentioned above, Jean-Baptiste de Lamarck was probably the first (in 1809) to formulate a hypothesis on human bipedalism within an evolutionary context [

37]: “

As a matter of fact, if some race of quadrumanous animals, ..., were to lose, by force of circumstances or some other cause, the habit of climbing trees and grasping the branches with its feet in the same way as with its hands, in order to hold on to them; and if the individuals of this race were forced for a series of generations to use their feet only for walking, and to give up using their hands like feet; there is no doubt … that these quadrumanous animals would at length be transformed into bimanous, and that the thumbs of their feet would cease to be separated from the other digits, when they only used their feet for walking.” (cited by Bender [

23]; underlining is ours).

Another self-evident view, already implicit (see our underlining below) in the writings of Lamarck, concerned the notion that this terrestrial adaptation was one of adaptation to open plains: “

Furthermore, if the individuals of which I speak were impelled by the desire to command a large and distant view, and hence endeavoured to stand upright...” (cited by [

23]).

Charles Darwin (1871) [

40] largely embraced Lamarck’s point of view of a changing environment as the reason to develop orthograde bipedalism (underlining is ours): “

As soon as some ancient member in the great series of the Primates came, owing to a change in its manner of procuring subsistence, or to a change in the conditions of its native country, to live somewhat less on trees and more on the ground, its manner of progression would have been modified; and in this case it would have had to become either more strictly quadrupedal or bipedal.” (cited by [

23]).

Darwin’s assertion that bipedalism conferred selective advantage because it freed the hands and thus enabled tool use was also first stated by Lamarck.

Alfred Russell Wallace (in 1898) [

41] also explicitly mentions open plains as the likely place of human evolution (underlining is ours): “

It has usually been considered that the ancestral form of man originated in the tropics, where vegetation is most abundant and the climate most equable. But there are some important objections to this view. The anthropoid apes, as well as most of the monkey tribe, are essentially arboreal in their structure, whereas the great distinctive character of man is his special adaptation to terrestrial locomotion. We can hardly suppose, therefore, that he originated in a forest region, where fruits to be obtained by climbing are the chief vegetable food. It is more probable that he began his existence on the open plains or high plateaux of the temperate or sub-tropical zone.” (cited by [

23]).

Steinmann (in 1908) [

42] envisaged a pithecoid creature as the last common ancestor of

Homo and

Pan, with a similar quadruped locomotion as today’s apes living in forests. He also hypothesized that climatic changes had gradually thinned the forests and transformed them into savannah regions. The arboreal ancestors of humans were then forced to adapt to the modified conditions by occasionally adopting an upright or semi-upright posture, similar to today’s apes. Few modifications of these intermediate stages, affirmed Steinmann, would be necessary on the road towards permanent bipedalism [

23]. In agreement with Darwin [

40], he already considered other typically human traits, including the evolution of versatile/dexterous hands and increased mental faculties (increased brain size), a consequence of this crucial phase in early human evolution.

Barrell (in 1917) [

43] specified hunting and carnivory as characteristics of such a terrestrial bipedal ape (underlining is ours): “

Did a similar climatic change in the Tertiary period acting on a species of large brained and progressive anthropoid apes isolated from the regions of continued forest compel them to adapt themselves to a terrestrial life or die? Did the gradual dwindling, leading even to the extermination of forests, in a region from which the forest fauna could not escape, produce a rigorous natural selection which transformed an ape, largely arboreal and frugivorous in habits, into a powerful, terrestrial, bipedal primate, largely carnivorous in habit, banding together in the struggle for existence and by that means achieving success in chase and war?” (cited by [

23]).

Bender et al. [

23] point out that the idea of “the trees leaving the apes” became the foundation of the savannah hypotheses. It was based on a very peculiar view of the luxurious forests as a place of evolutionary stagnation in contrast to the demanding open plains as a place of development of mankind. They concluded: “

We argue that the savannah hypotheses reached a high level of consensus in early and modern palaeoanthropology not because they arose through an objective interpretation of empirical evidence, as commonly believed, but mainly because they relied on the straightforwardness implied in the open plains ideas and the lack of alternative hypotheses to contextualize human evolution.”

From this brief recapitulation of the early history of paleoanthropological thinking, it is clear that bipedal locomotion is viewed as the single most important derived hominin trait, ever since Lamarck [

37]. This view is still at the center of the ruling paradigm, as exemplified by the following recent quote: “

The acquisition of terrestrial bipedal locomotion was one of the defining events in hominin evolution.” [

44].

It is most important to stress that the ‘Man the mighty hunter’ narrative (see Section 2.3) had already been explicitly formulated e.g., [

43], even before the first relevant fossil was known. The fossil finds of bipedal australopithecines corroborated their hominin status (see Section 2.3), at least as they were interpreted through the lens of the dominant paradigm.

2.3. Interpretations of Australopithecine Fossils and of Their Paleo-Ecological Context Appeared to Corroborate the Dominant Savannah Paradigm

The first find of an australopithecine by Raymond Dart (in 1925) [

45] consisted only of an infant skull without postcranial remains. Dart [

45] interpreted it as fitting with the reigning paradigm, that our ancestors adapted to a demanding open landscape by evolving habitual terrestrial bipedalism and carnivory.

According to his interpretation, the Taung child (2.3 Ma),

Australopithecus africanus, found in a cave on the grassland savannah in Bechuanaland, South-Africa, was an early hominin because it combined an ape-sized brain with at least two characteristics that were considered to be derived in our genus: bipedality, on the basis of the more ventral position of the foramen magnum, and human-like dentition, because of the parabolic shape of the mandibular tooth row instead of the ape-like U-shape. Below (see Section 3.4), we address how these assumptions should be treated with caution.

Furthermore, he made a few (more) erroneous assumptions, strengthening his belief that he had discovered a missing link between ape and man, while reinforcing his belief in the savannah paradigm. First, he assumed that the present open, dry grassland environment of Bechuanaland had prevailed at the time of the Taung child [

45]: “

It will appear to many a remarkable fact that an ultra-simian and pre-human stock should be discovered, in the first place, at this extreme southern point in Africa,..., for one does not associate with the present climatic conditions obtaining on the eastern fringe of the Kalahari desert an environment favourable to higher primate life. It is generally believed by geologists... that the climate has fluctuated within exceedingly narrow limits in this country since Cretaceous times.”

As such, the location of that first find fitted perfectly with the prevailing view that bipedalism had originated as an adaptation to more open terrain. It has, however, been recognized for almost four decades now that there was no increase in open country at the time the Taung child fossilized (see Section 3.1).

A second flawed assumption by Dart was that the associated broken animal bones, teeth and horns had been used by

A. africanus as weapons [

46]. More precise analysis of the cave contents has since clarified that the cave had been home to hyenas and that the Taung child had probably been their prey, rather than kin of predator apes e.g., [

47,

48,

49].

Finally, Dart [

45] concluded that the Taung child, as an adult, would have been smarter and fiercer than extant African apes: “

We must therefore conclude that it was only the enhanced cerebral powers possessed by this group which made their existence possible in this untoward environment.” And “...—

a more open veldt country where competition was keener between swiftness and stealth, and where adroitness of thinking and movement played a preponderating rôle in the preservation of the species”. This was a rather expeditious conclusion, which does not follow from his analysis of brain size: “

It is therefore reasonable to believe that the adult forms typified by our present specimen possessed brains which... equalled, if they did not actually supersede, that of the gorilla in absolute size.”

Moreover, this expeditious deduction contradicts several straightforward observations, such as the fact that the monkey brain of the (quadrupedal) baboon apparently suffices for a life on the savannah or that the brain size of australopithecines is mostly within the range of that of extant African apes (see Section 3.4.1.8) or that some chimps are savannah-adapted [

50].

As such, based only on an infant skull, and in combination with several erroneous and hastily formulated assumptions, Dart [

45], as many have since, reinforced the savannah paradigm and started a new one, i.e., that australopithecines are hominins, our closest relatives and/or ancestors.

Dart’s view was initially not shared by primatologists e.g., [

22,

51,

52], but was immediately embraced by Robert Broom, who confirmed that the Taung child fitted perfectly within the classical ‘belief’: “

Before Australopithecus was discovered some of us believed that the ancestor of man would be found in an anthropoid ape which had left the forest and taken to living on the plains and among the rocks; and here we have just such a form. ... Personally, I believe that Australopithecus is very near to the human ancestor, ... Certainly it is not at all nearly allied to the chimpanzee.” [

53].

Bender et al. [

23] suggest that we probably owe the currently widespread popular view that we descend from open plain hunters to the American playwright and scientific writer, Robert Ardrey, who wrote: “

We were born risen apes, not fallen angels, and the apes were armed killers besides.” His books, such as

African Genesis and

The Hunting Hypothesis [

54,

55], with detailed accounts of Dart’s paleoanthropological ideas, became worldwide bestsellers, and strongly influenced the popular and scientific discourse of early humans as aggressive primates hunting on African open plains. Ardrey inspired several prominent scientists and science writers, among them Konrad Lorenz, Desmond Morris and Lionel Tiger, and his writings were well reviewed, by, among others, Edward O. Wilson [

56].

To Sherwood Washburn,

A. africanus was “already a hunter” (quote by [

56]). The view that we descend from already murderous apes is also explicitly the theme of more recent work, e.g.,

Demonic Males: Apes and the Origins of Human Violence [

57].

The discovery in 1974 of Lucy (

A. afarensis) [

58,

59], an almost complete skeleton of an upright/vertical/orthograde ape, with the body and brain size of extant African apes (resembling the bonobo quite well, see Section 3.4.2), further perfected the picture of

Australopithecus as the missing link between the knuckle-walking, small-brained

Homo/

Pan last common ancestor and the upright bipedal and large-brained human being. The location, i.e., the Ethiopian badlands, devoid of extant apes, and the timing—in between the

Homo/

Pan split and the appearance of the first genuine

Homo fossils in Africa—added further credibility to the predominant savannah paradigm and to the conviction that australopithecines are our direct ancestors.

The view that our ancestors had to adapt to open landscape was further popularized by Yves Coppens [

60], co-discoverer of

A. afarensis, as the “East Side Story”. In the East Side Story version of the predominant savannah paradigm, ancestors of chimps and gorillas remained in the forests to the west of the African rifts, whereas australopithecines, the putative human ancestors, adapted to the open landscapes to the east of the rifts, in Kenya and Ethiopia and parts of South-Africa.

Soon thereafter, new finds, including, among others, that of

Sahelanthropus in Toumaï (Chad), 2500 km to the west of the Rift Valley [

61], compelled Coppens to abandon the East Side Story, at least with regard to the location in East Africa [

62]. However, and illustrative of the stubbornness of the savannah paradigm, he continues to insist that adaptation to open country is the driving force explaining hominin bipedality: “

East side story: It is rightly abandoned, in the sense that it is no longer East. But it is preserved as far as the story itself is concerned. The story itself, for me is the common ancestors who lived in the forest, ten million years ago and who had descendants who, for a reason of climate change, were found by chance in forest environments and others in a savannah environment. Additionally, those from a forest environment became ancestors of chimpanzees, then chimpanzees themselves. Additionally, those in open (or savannah) environments, in this case let’s say open forest, stood up to adapt to this much more open environment.” [

63]. We note that Coppens weakens the strong grassland savannah paradigm (open country, dry, hot) to ‘open forest’, i.e., much less demanding mosaic savannah than the one imagined by e.g., Dart [

45].

3.1. Savannah-based Narratives to Explain the Bipedalism of Australopithecines Lack Substance: There Was No Increase in Savannah at the Time of the Early Australopithecines

While australopithecine bipedalism has been regarded as an adaptation to open environment, ever since their first description in 1925, it has been realized that ‘grassland savannah’ is no longer a candidate environment to explain australopithecine bipedality [

24,

49,

64,

65,

66,

67,

68].

“

In fact, the immense plains and the immense herds on them are relatively recent aspects of the African environment, much more recent than the origin of the human family.” [

64].

Tobias, who held the chair of Raymond Dart, was understandably initially sympathetic to the savannah model. Nevertheless, in 1995, he exclaimed: “

We were all profoundly and unutterably wrong!”; “

Open the window and throw out the savannah hypothesis; it’s dead and we need a new paradigm.” and “

All the former savannah supporters (including myself) must now swallow our earlier words in the light of the new results from the early hominid* deposits.” [

66]. (*: Here, Tobias uses ‘hominid’ in the sense of ‘hominin’.)

Reed [

49] concluded that the Pliocene gracile australopithecines “

existed in fairly wooded, well-watered regions”, whereas the Pleistocene robust australopithecines existed “

in similar environs and in more open regions, but always in habitats that include wetlands”.

The evidence for wetland habitats of fossil apes and australopithecines has been extensively reviewed [

9,

10,

11,

12].

In summary, it should have been clear since at least the 1990s, e.g., [

49,

64,

65,

66], from the correct interpretation of the paleo-ecological context in which the early australopithecines fossilized, that adaptation to open plains could not have been the instigating factor to explain their bipedalism. Still, only recently, White [

68] described authors advocating what he considered “

the obsolete mind-set of a savanna-based origin of humanity...” as ‘savannaphils’. He concluded: “...,

despite valiant efforts at its resurrection, the hypothesis that opening grasslands led to hominid emergence and bipedality now stands effectively falsified.”

A further nail to the coffin of the savannah-based narratives that attempt to explain how australopithecines achieved bipedality as an adaptation to running over open plains, was provided by more and better-preserved australopithecine fossils. It is now clear that australopithecines had several ape-like climbing adaptations, indicative for living in forested areas instead of on open, tree-poor terrains. We review this anatomical evidence below (see Section 3.4).

3.2. The Homo/Pan Ancestor Was Not Quadrupedal, Semi-erect, Chimpanzee-like, but Already Occasional/Habitual Orthograde

On the basis of more recent fossils, discovered in the 1990s and at the turn of the millennium, it seems that another parsimonious assumption, at the basis of the dominant paradigm, is most probably erroneous: the

Homo/

Pan last common ancestor was not chimpanzee-like, i.e., knuckle-walking and semi-erect, as has been generally accepted for almost two centuries. Indeed, several pre-australopithecine orthograde apes, indicative of possible occasional or habitual bipedalism, are now known:

Sahelanthropus tchadensis (Toumaï, Sahel) [

69], between 7.0 and 6.0 Ma, with a brain volume of 320–380 cc, is considered by the authors as a possible hominin, although a more recent analysis classifies this species consistently as a stem hominid [

70]. The well-preserved skull showed small teeth and canines, and a rather flat face. The authors suggest that

S. tchadensis was bipedal, although this has been disputed [

71].

Orrorin tugenensis (Tugen Hills, Kenya) [

32], between 6.15 and 5.80 Ma, with an unknown brain volume, is considered by its authors as one of the oldest hominins. It has human-like teeth with thick (3 mm) enamel, smaller than those of australopithecines, although we argue that enamel thickness as a phylogenetic indicator should be interpreted with caution (see Section 3.4.1.1). Three fragments of femur reveal that

O. tugenensis was habitually bipedal [

32], with the femur closer morphologically to that of humans than to australopithecines.

Ardipithecus ramidus (Afar, Ethiopia) [

4,

72,

73], between 4.51 and 4.32 Ma, with a brain volume of 300–330 cc, shows a mosaic of ‘derived’ and ‘primitive’ features that suggest it was a facultative biped [

73].

Ardipithecus and

Orrorin were possibly “better bipeds” than the later australopithecines [

4,

8,

73].

Even before the discoveries of the abovementioned fossils, it had been suggested that the African ape ancestors were already partially orthograde and/or bipedal [

22,

28,

29,

74]. Moreover, orthogrady was present in numerous still older hominoids. The Eurasian and eastern African Miocene fossil apes (23–5 Ma) reveal that the early “crown” hominoids, such as

Morotopithecus bishopi (22–18 Ma), stood and/or moved with an orthograde posture [

5].

Keith [

75] recognized “

the antiquity of orthograde posture”, pointing to hylobatids and to late-Oligocene/early-Miocene dryopithecines. Morton [

22] had also realized that the bipedalism of early hominoids is not in disagreement with the orthograde posture of extant hylobatids: “

The gibbon’s primitive position in the anthropoid group has added value in that it strongly suggests the linking of our modern bipedalism with an early stage of erect arboreal habits in the ancestral anthropomorphous stem.” and that: “

Tree life is the only form of environment, and brachiation the only locomotive habit whereby the structures about the hip-joints would be given the opportunity to become gradually modified for an erect posture.”

A study of the frequency of bipedalism in almost 500 zoo-housed hominoids and cercopithecines found that all could move bipedally, with hylobatids engaging most frequently in bipedal locomotion [

13].

All of these data support an orthograde and, at least partially, arboreal last common ancestor of the hominoids (apes and humans).

3.3. Knuckle-Walking May Not Be an Ancestral Characteristic of the Homo/Pan/Gorilla Ancestor but May Have Evolved in Parallel in Both Pan and Gorilla

The almost complete lack of evidence of knuckle-walking in australopithecine fossils may be an important reason why paleoanthropologists conclude that there are no African ape fossils, and that australopithecines cannot be the ancestors of extant African apes.

However, in addition to the notion that no fossil apes knuckle-walked (see Section 3.2), convincing arguments have been put forward that knuckle-walking evolved independently in the African great apes (

Pan and

Gorilla). Both support their weight while standing and walking on the middle phalanx (knuckle) of their fingers (mainly III and IV), i.e., they knuckle-walk. It is important to note that the term “knuckle-walking” implies a mode of locomotion (gait), although extant African apes also stand motionless on their knuckles. Morton [

22] uses perhaps the more appropriate term ‘semi-erect posture’.

Knuckle-walking is a most unusual mode of posture/locomotion, present in only these two genera among primates. Such an unusual form of locomotion in two closely related taxa, one of which shares a common ancestor with hominins, leads to the straightforward assumption that knuckle-walking represents an intermediate stage between the supposed quadrupedality of ancestral apes and human upright bipedality. In other words, it seems more parsimonious to assume that the

Homo/

Pan/

Gorilla last common ancestor was knuckle-walking, and that

Pan and

Gorilla retained the ancestral knuckle-walking posture/gait while hominins evolved obligate orthograde bipedality.

Some authors have argued in support of proto-knuckle-walking in the

Homo/

Pan/

Gorilla ancestor. For example,

Homo,

Pan, and

Gorilla share several derived wrist characters, including—uniquely among catarrhines—the lack of a distinct

os centrale. This absence has been interpreted as offering increased stability in the wrist [

76], possibly indicative of a common ancestry of proto-knuckle-walking, from which the living African apes have diverged minimally, according to Begun [

77]. Ancestral knuckle-walking has been supported by the claim that

A. anamensis and

A. afarensis retained specialized wrist morphology, assumed to be associated with knuckle-walking [

78]. A study based on ‘morphological integration’ methods supports the common origin of knuckle-walking in gorillas and chimpanzees [

79].

Nevertheless, almost a century ago, Morton [

22] argued extensively and convincingly that knuckle-walking did not represent an intermediate stage preceding bipedalism, but that it was rather a reversion from bipedalism towards quadrupedalism: “

The semierect posture of the great apes is not an advance toward human bipedism, but it is direct evidence of the manner in which exaggerated brachiating adaptations have impaired earlier mechanical advantages for bipedism. The great apes have actually reverted to quadrupedism...”

The parallel evolution of the semi-erect posture of the great African apes was also recognized by Morton [

22]: “

The idea is quite commonly held that the terrestrial semierect posture of the great apes represents an approach toward the upright posture of man. Although the close relationship between the two groups seems to support this idea,... there is nothing homologous in their respective terrestrial postures.”

Several recent studies corroborate his century-old and largely overlooked view. Based on an analysis of morphological, behavioral and ecological data, it was concluded that knuckle-walking evolved in parallel in

Pan and

Gorilla [

14,

15]. Others [

17], comparing monkeys and apes, concluded that the variation evident in African ape wrist morphology can only be explained if the independent evolution of two fundamentally different biomechanical modes of knuckle-walking is recognized: an extended wrist posture in an arboreal environment (

Pan) versus a neutral, columnar hand posture in a terrestrial environment (

Gorilla). These authors concluded that humans did not evolve from a knuckle-walking ancestor.

Simpson et al. [

19] agree that forelimb ontogeny and anatomy indicate that knuckle-walking was independently acquired by

Pan and

Gorilla lineages. Rosen et al. [

13] also concluded that knuckle-walking evolved in parallel in

Pan and

Gorilla. In other words, knuckle-walking in both

Pan and

Gorilla is an example of homoplasy rather than a consequence of homology.

The absence of knuckle-walking from the human evolutionary pathway is also apparent when human infants are on all fours. They invariably place the palms flat on the ground with the fingers completely extended [

22,

80]. With the exception of

Pongo (fist-walkers), and

Pan and

Gorilla (knuckle-walkers), all primates, including human infants, are digiti-palmigrade [

27].

Different reasons for the evolution towards knuckle-walking have been suggested.

Morton [

22] suggested that knuckle-walking was a consequence of the very heavy upper body of extant African apes, relative to the pelvis and hindlimbs, which resulted in the necessity to support their forebody with their forelimbs, and that knuckle-walking was more practical for gorillas and chimpanzees due to their proportionally longer arms relative to legs: “

The great apes have actually reverted to quadrupedism, and the semierect position of their bodies is merely the physical result of their long arms and short legs.” [

22]. A comparable conclusion was reached independently by Simpson et al. [

19]: “...

we argue that it was adopted by African apes as a means of ameliorating the consequences of repetitive impact loadings on the soft and hard tissues of the forelimb by employing isometric and/or eccentric contraction of antebrachial musculature during terrestrial locomotion.”

Edelstein [

27] suggested that certain features of

Pan, e.g., the larger pelvis, the slightly smaller cranial capacity, smaller postcanine teeth, and somewhat larger canines, often interpreted as primitive compared to

A. afarensis, “

could have accompanied the evolutionary reversal associated with the habitats involved in the selection of knuckle-walking”, whereby he assumed that knuckle-walking was an adaptation to more stooped locomotion in dense forests.

Ward et al. [

20] analysed the pelvis of

Rudapithecus hungaricus (10 Ma), an orthograde ape with a more flexible lower back and a shorter pelvis than extant apes. Modern African apes have long, high iliac blades (pelvis) and a short, stiff lower back, whereas humans have longer, more flexible lower backs. They note that, if humans evolved from an African ape-like body, substantial changes to lengthen the lower back and shorten the pelvis would have been required to acquire orthograde bipedalism, but if humans evolved from an ancestor more like

Rudapithecus, this transition would have been much more straightforward. When

Rudapithecus came down to the ground, it might have had the ability to stand upright more like humans do. Ward et al. [

20] conclude that the longer lower pelvis in great apes must have evolved independently in each of the lineages

Pan and

Gorilla and that the last common ancestor of

Pan and

Homo “may have been unlike extant great apes in pelvic length and lower back morphology.” By implication, gorillas and chimpanzees would have evolved from a long-backed ancestor that was already able to stand and possibly walk on two legs, as such not excluding australopithecines as their ancestors. This also would mean that at some later point during their own evolution, they each dropped to their knuckles and independently created their own modes of walking.

McCollum et al. [

81] compared the type and number of vertebrae (axial morphology) in hominoids. They established 3 to 5 lumbar vertebrae and 5 to 8 sacral vertebrae in

P. paniscus, compared to 5 (exceptionally 6) lumbar vertebrae and 5 to 6 sacral vertebrae in

H. sapiens. From their findings, along with the six-segmented lumbar column of early

Australopithecus and early

Homo, they suggest that the last common ancestor of the hominoids possessed a long axial column and long lumbar spine and that reduction in the lumbar column occurred independently in humans and in each ape clade, and continued after separation of the two species of

Pan as well.

Thorpe et al. [

3] concluded that there is now a broad consensus that there is a clear lack of any convincing fossil evidence for knuckle-walking in crown hominoids or early hominins and that “the long reign of the knuckle-walking paradigm must be declared over”.

3.4. Indications that Australopithecines Are Not Hominins, but rather Panins and/or Gorillins: Similarities and Differences between Australopithecines, Extant African Apes and Homo

It is intriguing that any doubts that have been put forward with regard to the hominin status of australopithecines are largely ignored by the wider paleoanthropological community, even though the original savannah hypothesis has been largely abandoned (see Section 3.1) and that it is becoming clear that most earlier hominoids were already orthograde to at least some degree (see Section 3.2) and that knuckle-walking is very probably a derived trait in

Pan and

Gorilla (see Section 3.3).

Ever since they were first described, it has been clear that australopithecines have more in common with African apes than with humans. This is also the case for several late australopithecines, some of which are contemporary with early

Homo, e.g., [

29,

82,

83]. It has even been suggested that the late australopithecines are the most ape-like: “

The evolution of the australopithecine crania was the antithesis of the Homo line. Instead of becoming less apelike, as in Homo, they became more ‘apelike’.” [

84].

After some initial reluctance by several primatologists (see Section 2.3), australopithecines became generally accepted as hominins. Despite this general acceptance, there has been ongoing uncertainty and Tobias himself [

1] questioned whether

A. africanus was indeed a hominin.

The principal australopithecine traits that have been considered as hallmarks of humanity are orthograde bipedality and facial morphology (including reduced prognathism and small dentition). The former happens to be plesiomorphic, while the latter is too prone to evolutionary change to be useful as phylogenetic markers.

Below, we briefly readdress the suite of anatomical traits shared by australopithecines and extant African apes, and we indicate how strongly these australopithecine traits differ from those of extant and extinct

Homo. In addition, many of the differences between australopithecines and extant African apes could be seen as derived in apes, and several of the similarities between australopithecines and

Homo, considered to be indicative for the hominin status of australopithecines, could instead be primitive traits of stem hominoids, and therefore shared by most hominoids.

A number of more elaborate reviews were provided previously [

1,

28,

29,

30].

3.4.1. The Skull and Facial Features

While Dart’s claim that the

A. africanus infant was a hominin received some support from the start (see Section 2.3), it was initially mostly strongly opposed.

Keith [

51] stated: “

The skull is that of a young anthropoid ape ... showing so many points of affinity with the two living African anthropoids, the gorilla and chimpanzee, that there cannot be a moment’s hesitation in placing the fossil form in this living group. At most it represents a genus in the gorilla-chimpanzee group.”

Hrdlička, founder of

American Journal of Physical Anthropology, the first after Dart to examine the Taung skull, concluded: “

The skull itself is that of an anthropoid ape approaching rather closely in size and form the chimpanzee” [

85].

Woodward [

52] could “

see nothing in the eye-sockets, nasal bones and canine teeth which was nearer to the human condition than those parts of the skull of a modern young chimpanzee.” (cited by [

1]).

Overall, the Taung child skull looks very much like that of a bonobo infant ().

Comparing infants/juvenile skulls to make assertions about phylogeny may be problematic because young individuals may resemble each other more than adult representatives of the same species. On the other hand, derived features are more apparent in adult representatives on top of sexual dimorphism differences, and therefore juvenile characters might be more relevant with regard to phylogenetic considerations.

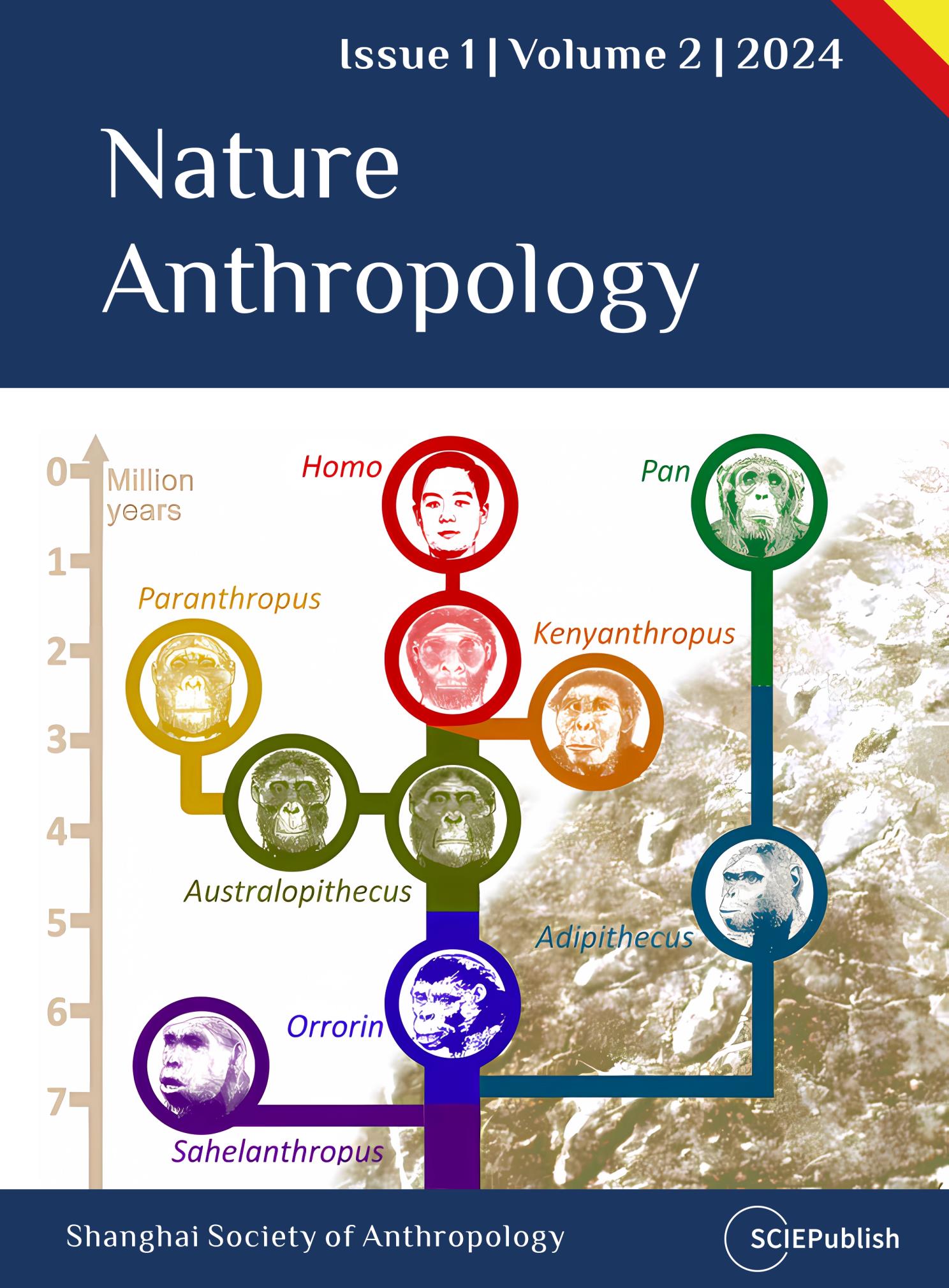

Figure 1. (a). Front views of skulls of human child, Taung child, bonobo child. (b). Oblique front views of infant skulls of Pan, Gorilla, Homo (top, from left to right), and Australopithecus africanus child (Taung child) (bottom).

Following the above authors [

51,

52,

85], many others have emphasized the striking similarity of australopithecine fossil skulls with those of extant African apes. Johanson and Edey [

59] considered the composite skull, reconstructed mostly from A.L.333 specimens (

A. afarensis), to look very much like a small female gorilla. An extensive and detailed review of the literature concerning comparative skull morphology was provided by Verhaegen [

29,

30], supporting the morphological similarities between australopithecines and the African apes.

3.4.1.1. Diet, Dentition and Dental Development

The microwear of early australopithecines strongly indicates frugivory [

9,

86], again in agreement with the faunal assemblages, which suggest a mosaic habitat that is better described as open-forest or woodland rather than savannah or bushland (see Section 3.1), in opposition to the ‘running and hunting on the open grassland savannah’ scenarios, addressed above (see Section 2.3).

While dentition is clearly indicative of the diets of a certain species, we think that, in general, one should refrain from over-relying on dentition and skull morphology to decide on its taxonomic position, exactly because skull morphology very much depends on dentition, which in turn is very adaptable to the type of diet. Indeed, McCollum [

87] concluded that the overall skull morphology of the robust australopithecines can be considered to be the developmental consequence of a unique combination of very large, especially broad molars and premolars with small incisors and canines. This is not in disagreement with the previous suggestion that the genus

Paranthropus, which lumps together the southern African and eastern African robust australopithecines, is paraphyletic [

28,

29] (see Section 4.3).

The molar and premolar enamel of australopithecines is thicker than that of extant apes and this has been a major argument to argue for their hominin status, but in fact it is the thinner enamel of extant African apes that is derived. The conclusion of Martin [

88] is unambiguous: “

Thin fast-formed (pattern 3) enamel represents the ancestral condition in hominoids; it increased developmentally to thick pattern 3 enamel in the great ape and human clade and that condition is primitively retained in Homo and in the fossil hominoid Sivapithecus (including ‘Ramapithecus’). Enamel thickness has been secondarily reduced in the African apes and also, although at a different rate and extent, in the orang-utan. Thick enamel, previously the most important characteristic in arguments about the earliest hominid∗,

does not therefore identify a hominid∗.” and “

Of the living members of the great ape and human clade, only Homo sapiens retains the condition of enamel thickness and development from the common ancestor of the clade and can therefore be regarded as the most dentally primitive member of it”.

∗: Here, the author uses ‘hominid’ meaning ‘hominin’.

In summary, all hominoids had initially thin enamel, the hominids (including the australopithecines) developed thicker enamel, and this was reduced secondarily in all extant great apes but not in our lineage, giving the false impression that australopithecines are our closest relatives.

In conclusion, dentition, enamel thickness and tooth microwear are strongly related to diet, but may have limited phylogenetic value, given their malleability and evolvability. Several skull features, in fact, may be the result of homoplasy rather than being useful indicators of homology.

Also, the dental development of australopithecines links them more closely to African apes than to the genus

Homo. Initially, comparisons of the pattern of tooth formation and eruption in

A. africanus with that of humans and apes, was interpreted as indicating a human-like rather than ape-like maturation process, because the Taung child was thought to have died at about 6 years of age [

89]. Bromage and Dean [

90], however, estimated the age at death for several young specimens of

A. africanus,

A. afarensis and

P. robustus by counting incremental growth lines on the teeth, and could not come up with any ages greater than about 3 years. This finding places

Australopithecus on an ape-like schedule of development. Bromage [

91] concluded that, in addition to similarities in facial remodelling,

Australopithecus in general, had maturation periods similar to those of the extant chimpanzee. Ape-like dental eruption of australopithecines has been confirmed by Smith [

92] as well as Conroy and Vannier [

93,

94]. The robust South African australopithecines display a unique pattern of dental development that is only superficially similar to that of humans, while in

A. africanus the overall pattern of dental development is similar to that in chimpanzees [

1,

95,

96]. Smith [

97] confirmed that the patterns of dental development of gracile australopithecines and

H. habilis remain classified with the African apes.

A clear difference between robust australopithecines and the extant African apes are the small canines in the former. This has been interpreted as a similarity with our genus, but may instead be a primitive characteristic, also present, for example, in

S. tchadensis [

69,

71] between 7.0 and 6.0 Ma. It is possible, in fact, that the larger canines in

Pan and

Gorilla are related to increased aggressive male behaviour and that they are a relatively late development. Indeed, the (less aggressive) bonobos “have relatively small and only slightly dimorphic canine teeth” [

98]. Edelstein [

27], as mentioned above, argued that the larger pelvis, the slightly smaller cranial capacity, the smaller postcanine teeth and the somewhat larger canines of

Pan could have accompanied the evolutionary processes of adaptation to the forest habitats involved in the selection of knuckle-walking.

3.4.1.2. Skull Thickness and Skull Crests

Australopithecine skull bone thickness is comparable to that of most mammals including apes, but totally different from the pachyosteosclerosis seen in early-Pleistocene

Homo erectus [

99] and in several semi-aquatic and aquatic species [

100].

Sagittal crests are related to diet, as they predominantly exist for the attachment of powerful jaw muscles needed to chew tough food such as nuts, sedges and bamboo. Skull crests are present in the robust australopithecines, but may have more to do with diet [

87], than having phylogenetic value. Still, crests are also present in

Gorilla, but not in

Homo.

3.4.1.3. Mandibular Jaws and Prognathy

Extant African apes have prognathic faces that project forward of the anterior cranial fossa, whereas humans have orthognathic faces, that lie almost entirely beneath the anterior cranial fossa. Australopithecine facial prognathy is variable.

It has been shown that prognathy (among several other skull characteristics) is comparable between

P. paniscus and the almost complete skull of

A. africanus Sts.5 [

98]. According to Ferguson [

84],

A. africanus Sts.5 falls well within the range of

P. troglodytes and is markedly prognathous or hyperprognathous. The mandibular ramus morphology of an

A. afarensis specimen was described to closely match that of gorillas, with the clear ape-like U-shape [

101].

Not only dentition, but also jaw muscles and overall skull morphology (prognathy, skull crests) seem to evolve readily, with dentition and jaw muscles adapting to diet, and prognathy and skull crests in turn adapting to dentition and jaw muscles [

87]. Therefore, overall skull morphology may tell us much about the diet of a taxon, but may be too evolvable to have primarily phylogenetic importance.

3.4.1.4. Nasal Region

The nasal region of australopithecines is characterized by a flat, non-protruding nasal skeleton which does not differ qualitatively from the extant non-human hominoid pattern, but which is in marked contrast to the protruding nasal skeleton, characteristic and exclusively found in

Homo skulls [

102].

Dart [

45] had claimed that Taung differs from all living apes by the unfused nasal bones, but Schultz [

103] pointed out that this claim could not be maintained in view of the very considerable number of cases of separate nasal bones among orang-utans and chimpanzees of ages corresponding to that of the Taung child.

Eckhardt [

104] showed that the nasal bone arrangement, suggested as a derived key diagnostic of

P. robustus, is found in an appreciable number of greater apes, particularly clearly in some chimpanzees, and McCollum [

105] noticed the overall similarity of the non-robust

Australopithecus subnasal morphological pattern with that of the chimpanzee.

Also, the pattern of pneumatization of

A. afarensis is found only in the extant apes among other hominoids [

106]. Accordingly, Conroy and Vannier [

93] were intrigued that in Taung the pneumatization extends into the zygoma and hard palate, because an intrapalatal extension of the maxillary sinus has only been reported in chimpanzees and robust australopithecines among higher primates.

3.4.1.5. Air Sacs

The human hyoid (lingual bone or tongue bone) lacks the large and distinctive bulla of the chimpanzee hyoid, into which the air sacs extend [

107]. The morphology of the chimpanzee hyoid is typical of that found in great apes.

The bulla-shaped body of the hyoid in

A. afarensis DIK-1-1,

Pan and

Gorilla has been interpreted to represent the primitive condition, rather than the more shallow, bar-like hyoid body of modern humans and

Pongo [

108]. It can be assumed that the bulla-shaped body of

A. afarensis DIK-1-1 almost certainly reflects the presence of laryngeal air sacs, which are characteristic of African apes, but absent in humans. It has been suggested that air sacs have been lost during the presumed transition from

Australopithecus to

Homo, as a preadaptation to speech [

107,

109], an excellent illustration of what Phillip V. Tobias [

1] named ‘australopithecine anthropocentrism’ (see 4.3). We consider the putative presence of air sacs in

A. afarensis as another striking similarity with extant apes.

3.4.1.6. Position and Orientation of the Foramen Magnum

Dart [

45] interpreted the relatively ventral position of the foramen magnum in the infant skull of Taung as conclusive evidence for bipedal locomotion in

A. africanus. However, Taung was perhaps 3.5 years of age at death [

90], and the foramen magnum may not have yet achieved its adult position. As such its position is not a solid indicator of bipedality in

A. africanus [

110]. Indeed, young gorillas and chimpanzees have foramina magna more ventral than adults and well within the range of

A. africanus Sts.5 e.g., [

80,

111].

Second, even in adults, the position of the foramen in gracile (Sts.5) and robust (KNM-ER 406) australopithecines has the same index as in bonobos [

106]. In Lucy, the foramen magnum is at the same ventral position as

Homo, which was considered as a clear indication for upright bipedal locomotion, but Kimbel and Rak [

112] stated: “...,

in contrast to the data on foramen magnum position, which align A. afarensis and other australopiths with modern humans, the data on orientation of the foramen situate the australopiths in an intermediate position between modern apes and humans, but closer to the former (chimpanzees, specifically)”.

The position of the foramen magnum and the midfacial angle in AL 822-1, a female

A. afarensis (3.1 Ma), are even more ape-like than in the extant gorilla [

112].

The difficulties in linking foramen magnum indices to the degree of orthogrady have been outlined in detail recently [

113]. Locomotor adaptations, for example, may not be the sole factors responsible for the anteroposterior position of the foramen magnum in primates. Although the more anterior positioning of the foramen magnum in

Homo compared to most other primates may be linked to reduced locomotor versatility of the head and reduced head balancing as a consequence of obligate orthograde bipedalism, it is also possible that this position could be (partially) explained by mandibular and cranial vault shape modifications of the skull, due to changes in diet, mastication, and encephalization [

114,

115].

It is also of interest to note that the completely arboreal gibbons and the quadrupedal South American monkey,

Saimiri, have the most centrally placed foramen magnum of all primates [

116], suggesting that this feature has more to do with differences in how the head is carried and with facial length, or may be primitive in apes.

In conclusion, the position of the foramen magnum in australopithecines is not particularly human-like as initially claimed, and in general, its value as a defining characteristic of orthograde bipedalism may be limited.

3.4.1.7. Semicircular Canals of the Vestibular Labyrinth

Cross-sectional images of the bony labyrinth, obtained by high-resolution computed tomography, showed that the earliest species to demonstrate the modern human morphology, in which an almost 90° rotation of the labyrinth has occurred, is

H. erectus/

H. ergaster [

117]. In contrast, the semicircular canal dimensions in crania attributed to

Australopithecus and

Paranthropus resemble those of the extant great apes [

117]. This has been interpreted as indicating that

H. ergaster was fully bipedal for running [

118], but this is only one of a number of possible explanations [

119]. The orientation of the labyrinth not only represents another similarity between australopithecines and extant apes, but—if orientation of the labyrinth is taken as indicative for upright running [

118]—it is also a further indication that australopithecines were not well adapted for orthograde bipedal running.

3.4.1.8. Brain Size (and Growth)

The published values for brain sizes of australopithecines and extant African apes diverge substantially but are overall in the same range.

It has been claimed that there is actually no major transition between

Australopithecus and

Homo [

120] and that early hominins were substantially more encephalized than previously thought, on the basis of a novel 3/5 scaling exponent for primate brain-body evolutionary allometry [

121].

According to Gunz et al. [

122], comparison of infant to adult endocranial volumes indicates protracted brain growth in

A. afarensis, likely critical for the evolution of a long period of childhood learning in hominins. However, recent detailed analysis assessed that “

adult (and subsequently estimated neonatal) brain size in australopiths is absolutely intermediate between chimpanzees and gorillas” and that “

average annual rates (ARs) of brain growth and proportional size change from birth (PSC) ... for A. afarensis are significantly lower than those of chimpanzees and gorillas. Both ARs and PSCs for A. africanus are similar to chimpanzee and gorilla values. These results indicate that ... high rates of brain growth did not appear until later in human evolution.” [

123]. This is in agreement with dental development in australopithecine infants (see Section 3.4.1.1), which indicates maturation periods similar to those of the extant chimpanzee [

90,

92,

93,

94,

97].

Gunz et al. [

122] scanned eight fossil crania of

A. afarensis using conventional and synchrotron computed tomography and inferred key features of brain organization from endocranial imprints and explored the pattern of brain growth by combining new endocranial volume estimates with narrow age at death estimates for two infants. Contrary to the statement of Cofran [

123], e.g., that early hominins were derived in some aspects of brain anatomy, Gunz et al. [

122] concluded that sulcal imprints revealed an ape-like brain organization and no features were derived towards humans. The latter is in agreement with the conclusions of Falk et al. [

124] that the skull endocast, dentition, facial growth and possibly foramen magnum position of the Taung child strikingly resemble those of apes. Simons [

89] stated: “Dart’s enthusiasm for

A. africanus as a human ancestor was occasioned by his misidentification of the lamboid structure as the lunate sulcus and thus reading a human-like sulcal pattern in the natural endocast of the brain of the Taung child”.

3.4.2. Body Size, Body Proportions and Strength

The estimated adult height (cm) of

A. afarensis (females: 110; males: 135) and the adult weight (kg) (females: 30; males: 45) is completely in line with that of the bonobo. According to Zihlman et al. [

98],

P. paniscus provides a suitable comparison for

Australopithecus Sts.5, with comparable body size, postcranial dimensions and cranial and facial features. Kano [

125] concluded that bonobos have body proportions comparable to those of australopithecines, including a spine that enters the skull lower than in chimpanzees, differing from

A. afarensis only by the degree of adaptation to bipedalism. The drawing by Zihlman [

126] in the

New Scientist illustrates how “

remarkably well” Lucy’s fossil remains match up with the bones of the bonobo.

According to Green et al. [

127], however, the upper:lower limb-size proportions in

A. afarensis are similar to those of humans and significantly different from all great ape proportions, while

A. africanus is more similar to the apes, and significantly different from humans. The claim of Green et al. [

127], however, is contradicted by the statement that long legs relative to body mass are first unequivocally present in

H. erectus 1.8 Ma, whose relative leg length (assessed from the femur) is possibly up to 50% greater than in

A. afarensis [

118].

Reno et al. [

128] claim that sexual dimorphism in

A. afarensis is comparable to that of

Homo, but the sexual dimorphism of australopithecines is generally accepted to be much more pronounced than in

Homo, in between

Pan and

Gorilla e.g., [

129,

130]. Unlike in the extant African apes, it is not accompanied with large canines (in males) and therefore possibly not due to male aggression or male/male competition. Lee [

129] found that the sexual dimorphism of

A. afarensis differs not only from that of humans, but also from that of chimpanzees. Still, some intriguing sexual dimorphic traits of australopithecines might be explained through comparison with chimpanzees. Dominant chimps (males and large female individuals) monopolize the terrestrial feeding places, where the low-hanging fruits can be gathered with the help of postural bipedality, whereas the smaller females are forced to be more arboreal [

35]. This may coincide with suggested feeding pattern differences, whereby male australopithecines could have traits more associated with terrestriality, and females more with arboreality [

131].

Comparison of trabecular bone density between different taxa is difficult, with different degrees of similarity depending on limb position [

132], but bone thickness is very different when australopithecines are compared to

H. erectus, which is typically characterized by very heavy bones (pachyosteosclerosis), especially in the skull (see Section 3.4.1.2), as reviewed by Munro and Verhaegen [

99].

3.4.3. Forelimbs and Tool Production/Use

Long and curved manual phalanges were present in, e.g.,

A. afarensis DIK-1. The manual digits of

A. afarensis are just as curved as in apes, and the bar/glenoid angle is not significantly different from apes [

108,

131,

133], indicative of regular vertical climbing and arm-hanging, as in apes [

35]. According to Lewin [

133], Lucy’s

Pan-like tree-climbing tendencies can be inferred from her elongated curved feet and hand finger bones.

Australopithecines are believed to express

Homo-like traits in hand structure (long thumbs and short fingers), and this has been interpreted as enabling delicate motor skills needed for stone tool-making [

134]. However, thorough analysis assessed that

A. afarensis had shorter thumbs than previously thought, with proportions more closely resembling those of gorillas and not enabling the precision grip of hominins [

135].

Some fossil stone artefacts have been assigned to australopithecines [

136], and this has been interpreted as confirmation that australopithecines were on the road to humanity. However, besides the fact that chimps and bonobos are known to display various types of tool use e.g., [

137], the bonobos Kanzi and Pan-Banisha exhibit basic Oldowan flake production abilities [

134]. Chimp stone artefacts resemble those of the earliest East African sites assigned to australopithecines [

138]. Even capuchin monkeys (genera

Cebus and

Sapajus) use stone tools to crack shellfish and/or nuts [

139,

140].

A recent analysis [

141] concludes that “

two pre-requisites for the emergence of early lithic technologies—lithic percussion and the recognition of sharp-edged stones as cutting tools—might be deeply rooted in our evolutionary past (as old as 13 Ma).”

These findings raise questions about the value of stone artefacts as markers of humanity and their validity as proof that australopithecines were closer to humans than to African apes.

3.4.4. Thorax and Shoulders and Back Muscles

The thorax, shoulders and back muscles of australopithecines are indicative of climbing and arboreality [

142]. Alemseged et al. [

108] noticed a

Gorilla-like scapula in

A. afarensis DIK-1. Moreover, the similar cone-shape of the ribcages of

A. afarensis (Lucy, A.L.288) and the chimpanzee is apparent [

134], and very different from the barrel-shape of the human ribcage (see in Hunt [

35]).

3.4.5. Pelvis, Bipedalism and Orthograde Posture

The australopithecine pelvis morphology—together with the position of the foramen magnum in the skull (see Section 3.4.1) and the hindlimb anatomy (see Section 3.4.6)—has been considered as indicative of their clear terrestrial bipedality and therefore as evidence for their hominin status [

1,

59]. Also the short iliac bones of

A. africanus are considered as indications of their hominin status.

According to Hunt [

35], however, Lucy’s very wide hips made her unsuited to bipedal locomotion and she was most likely a postural biped. Interestingly, bipedality in chimpanzees is mostly postural [

35]. Others concluded that Lucy’s pelvis is as distinct from the human’s as it is from the chimpanzee’s e.g., [

131].

In fact, the low pelvises of monkeys and humans, and of australopithecines, are probably the ancestral hominoid condition, a conclusion already reached by the primatologist Straus [

143], almost a century ago: “

The human ilium would seem most easily derived from some primitive member of a preanthropoid group, a form which was lacking many of the specializations, such as reduction of the iliac tuberosity and anteacetabular spine and modification of the articular surface, exhibited by the modern apes. I wish to emphasize here that the anthropoid-ape type of ilium is in no sense intermediate between the human and lower mammalian forms. Its peculiar specializations are quite as definite as those exhibited by man, so that it appears very unlikely that a true anthropoid ape form of ilium could have been ancestral to the human type”.

Rosen et al. [

13], who concluded that knuckle-walking evolved in parallel in

Pan and

Gorilla, considered the human body form, particularly the long lower back and orthograde posture, as primitive, although the latter view is not shared by Lovejoy [

144].

These observations further support knuckle-walking as a derived trait in both

Pan and

Gorilla e.g., [

14,

15,

22] (see Section 3.3).

Hunt [

34,

35] carried out one of the few detailed studies on the bipedalism of chimpanzees. He observed 97 instances of bipedality among 21 wild chimpanzees for a total time of over 700 h, and noticed that 96% of bipedalism was postural (facultative). In 42.3% of the terrestrial instances, and 93.0% of the instances in terminal branches of trees, a forelimb oriented in an arm-hanging position stabilized the bipedal posture. Bipedal locomotion made up less than 4% of the instances, and larger chimpanzees were the most bipedal.

Bipedalism among chimpanzees was much less likely to occur in open habitats and was observed to occur mainly in forested environments, contradicting once more the dominant open plain paradigm. Hunt [

35] hypothesized that: “bipedal postural feeding may have been a preadaptation to the fully realized locomotor bipedalism in

Homo erectus.”, but, in agreement with Stern, Jr. and Susman [

131], we suggest that australopithecine bipedalism was predominantly postural (facultative) as well. The australopithecines certainly were not built for endurance running ( in [

118]). Finally, according to the detailed analysis by Steudel [

145], human bipedal locomotion is not more energy efficient than e.g., chimpanzee locomotion.

3.4.6. Hindlimbs, Feet and Bipedalism

It is generally accepted that australopithecines were more bipedal than extant African apes, not only because of the more ventral foramen magnum (see Section 3.4.1) and the orthograde posture (see Section 3.4.5.), but also because of the more human-like orientations (although with a rather ape-like anatomy) of the distal femoral (knee) and tibial (ankle) articulations of

A. afarensis [

131] and the broader calcaneus.

Still, the more human-like features of the australopithecine hindlimbs have been assessed to be less abundant than the more ape-like features [

25,

28,

29,

30]. Moreover, the long femoral neck and the valgus knee could be plesiomorphic, i.e., correlated with bipedalism, orthogrady and/or lateral movement of the hindlimbs, already present in the ancestral hominoids and possibly in relation to aquarborealism [

12,

146].

Several studies found that

Homo, when compared to both

Pan and

Australopithecus, has substantially larger articular surface areas relative to body mass in most joints of the lower body e.g., [

118].

Harcourt-Smith [

147] reviewed the huge diversity of foot morphology among australopithecines. Interestingly, none of the features that are suggested to enable the endurance running of

Homo are present in australopithecines. All 26 anatomical characteristics that improve endurance walking, or running, or both, are only apparent in

Homo ( in [

118]), and most improve only running. Consequently, if australopithecines were our ancestors, and if running over open plains was the evolutionary force that shaped our genus, it appears that we started to run over long distances without first learning how to walk.

With regard to foot morphology, there is huge variation in australopithecine foot structures. What appears to be the case is that most australopithecines were capable of different modes and different degrees of bipedal locomotion, while some maintained—or developed—a more arboreal climbing foot.

Bramble and Lieberman [

118] indicated numerous profound differences between the feet of

Australopithecus and

Homo. For example, the transverse groove into which the Achilles tendon inserts on the posterior surface of the heelbone is chimpanzee-like in size in three early australopithecine Hadar specimens and contrasts with the substantially wider and taller attachment area characteristic of

H. sapiens. The Hadar and Sterkfontein specimens, meanwhile, had a partial arch only, as indicated by the enlarged medial tuberosity of the navicular, which is also enlarged in chimpanzees, but diminutive and not weight-bearing in

Homo.

Modern humans have a large heelbone relative to body size and display a uniquely convex cuboid facet, resulting in a more rigid midfoot, generally assumed to facilitate bipedalism. In general, the more arboreal great apes display relatively deeper cuboid facet pivot regions for increased midfoot mobility.

The juvenile Dikika apparently had a grasping foot, and so too did ‘Little Foot’ (Stw 573). Tobias [

1]:

“

The talus is human-like, though not perfectly so; the navicular shows both human-like and apish traits; while the medial cuneiform and first metatarsal bones have revealed to Clarke and myself (1995) that the great toe diverged from the lateral four toes, as in apes...”

Even ‘Lucy’ had a slightly abducted hallux [

148].

The famous footprints of Laetoli (3.7–3.5 Ma) [

149], indicating bipedal gait, are still the subject of profound dispute. The numerous problems associated with the interpretation of the Laetoli footprints, and with ichnotaxonomy in general, were addressed in detail by Meldrum et al. [

150] and Harcourt-Smith [

151]. Meldrum et al. [

150] could not conclude that an arch was present, found that the hallux was

Gorilla-like, established midtarsal flexibility (an adaptation to arboreality) and saw no definite proof of human-like footprints.

Comparison—admittedly superficial—of the Laetoli footprints with those of a human and

Gorilla beringei () suggests more similarity of the Laetoli footprints to that of

Gorilla. The fragmentary hominin skeletal fossils from the Upper Laetoli Beds are all attributed to Australopithecus. This suggests that the footprints were made by

A. afarensis, which is not in contradiction with the previous suggestion that

A. afarensis is possibly ancestral/more closely related to

Gorilla [

28,

29,

30]. Moreover, Harper et al. [

152] found that

A. afarensis demonstrates the most human-like heelbone and concluded that this was consistent with obligate bipedalism. But, if

A. afarensis was ancestral to

Gorilla, its bipedalism may not necessarily be indicative of human bipedalism, as

G. beringei beringei is terrestrial for 95% of the time [

152].

Anaya et al. [

153] suggest that the possession of a rigid foot could represent a conserved trait, whereas the specialized pedal grasping mechanics of extant apes may be more derived. Interpreted this way, extant great apes would no longer possess a rigid foot because they reverted to a more arboreal lifestyle after each genus diverged from a common, already orthograde, ancestor.

Furthermore, it’s worth noting that certain morphological features considered indications of habitual or even obligate bipedalism appear early in the fossil record and then seem to disappear. For instance,

A. anamensis (4.2 Ma) possessed a modification of the talar trochlea that permitted the leg to pass directly forwards during mid-stance, whereas later australopithecines did not possess this more ‘human-like’ condition. In addition, some late australopithecines, such as

A. sediba (1.98 Ma), display more arboreal post-cranial characters than earlier australopithecines.

A. sediba had a more arboreal foot with an opposable big toe [

152,

154,

155]. This appears to show that australopithecines may have been becoming less bipedal and more arboreal over time.

According to Verhaegen [

29], the later australopithecines were probably more knuckle-walking than the earlier australopithecines: “

The boisei ulnae O.H.36 and L.40-19 and humerus KNM-ER 739 were of Gorilla robusticity and length (McHenry, 1991, 1992; Howell & Wood, 1974; Senut, 1980; Leakey, 1971; Aiello & Dean, 1990, pp. 367–369), and the curvature and the cross-section of L.40–19 are reminiscent of knuckle-walkers (Howell & Wood, 1974).”

Leakey et al. [

82], addressing the late australopithecine

Paranthropus boisei, suggested: “

the Rudolf australopithecines, in fact, may have been close to the ‘knuckle-walker’ condition, not unlike the extant African apes.”

Moreover, it has been suggested that

Ardipithecus and

Orrorin were possibly better bipeds than the later australopithecines [

8,

32,

73], which is not in contradiction with the possibility that these species were intermediate between a more orthograde ancestor and the knuckle-walking extant African apes. In fact, knuckle-walking may have developed in the late australopithecines instead of being initially present in the early australopithecines.

Figure 2. Footprints of (from left to right) Homo sapiens, Gorilla beringei (Eastern gorilla), and of extinct African hominid, possibly Australopithecus afarensis, at Laetoli 3.5–3.7 Ma [

149]. Not to relative scale.

In fact, the analysis of Bramble and Lieberman [

118] reveals the profound differences between australopithecines and

Homo, especially with regard to bipedal locomotion, exactly the trait for which australopithecines have been regarded as hominin. It was the bipedality of

A. africanus that led Tobias [

1] to conclude that it was a hominin after all, despite its numerous “

apish... evolutionary stigmata” (see Section 4.3).

Recently, Wiseman [

156] compared a total of 36 muscles of the pelvis and lower limb of

A. afarensis specimen AL 288-1 with those of

H. sapiens. These were reconstructed using three-dimensional polygonal modelling, guided by imaging scan data and muscle scarring. Since the author assumed that

A. afarensis is a hominin, the data were compared only with

H. sapiens (but not

Pan). Nevertheless, the author concluded that overall the thigh of AL 288-1 was probably more muscular and less fatty than the human thigh. The author stated that this is similar to the bonobo, an active, arboreal species. It would be of interest to learn about the results of a direct comparison with

P. paniscus.

It is worthwhile to conclude this section with a long quote from Phillip V. Tobias [

1] (whereby his use of “hominid” corresponds to the use of “hominin” in the present publication): “

After decades in which Dart, Broom, Sollas, Clark, Robinson, Schepers and others strove to show how human Australopithecus was, and ultimately were so successful that virtually everyone came to accept Australopithecus as a hominid, it may seem strange that in the final decade of the century we are bringing to light more and more apish features of this extraordinary species.... Falk (1989) and Tobias (1981) revealed how strikingly ape-like the brain of A. africanus was: both in quantity and in quality. Dean and Wood (1981) and Tobias (1967) showed how apish the base of the cranium was, with its ape-like petrous pyramids. Conroy and Kuykendall (1995) and Moggi-Cecchi (1997) laid bare the ape-like pattern of tooth formation—and so did Beynon and Dean (1988) for the rate of tooth formation. Benade (1990) demonstrated some curious ape-like features of the spinal column. Berger (1994) produced the same from the shoulder and from the knee joint (Berger and Tobias 1996); while Brauer et al. (n.d.) inferred the ape-like great toe of “Little Foot”. McHenry and Berger (n.d.) found apish bodily proportions in A. africanus. Everybody, everything, was crying Ape! After long years of australopithecine anthropocentrism, we have entered upon a period of rampant australopithecine apishness! So much so that the custodian∗ of the largest collection of A. africanus specimens could stand before the Royal Anthropological Institute and feel justified in asking: Was A. africanus a hominid? We should not be surprised to find many ape-like traits in the australopithecines. From the beginning Dart saw apish features: he called the species Australopithecus—the southern ape, not Australanthropus—the southern man.”

∗ Here, Phillip V. Tobias is referring to himself.

Conceptualization, M.V. (Mario Vaneechoutte), M.V. (Marc Verhaegen); Investigation, F.M., M.V. (Mario Vaneechoutte), M.V. (Marc Verhaegen), S.M.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, M.V. (Mario Vaneechoutte); Writing—Review & Editing, F.M., M.V. (Mario Vaneechoutte), M.V. (Marc Verhaegen), S.M.; Visualization, F.M., M.V. (Marc Verhaegen).

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.