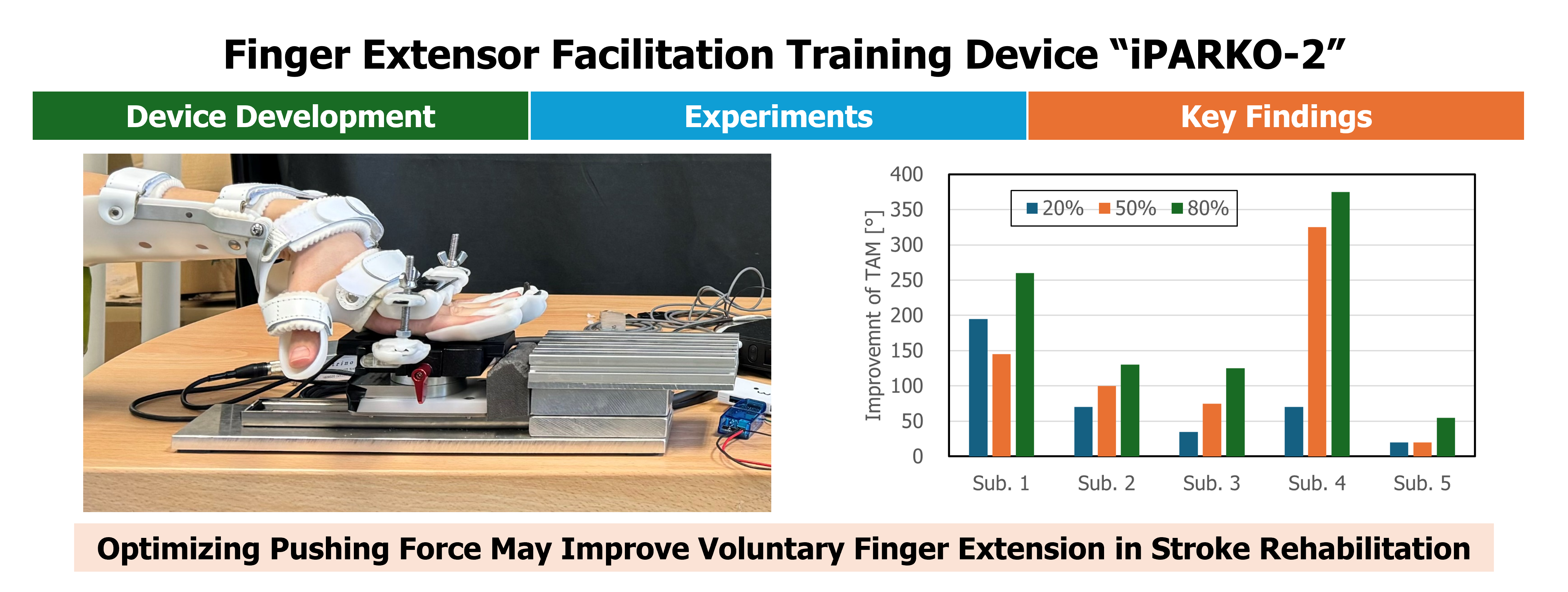

Relationship between Pushing Force and Improvement in Total Active Motion in Training with Finger Extensor Facilitation Training Device “iPARKO-2”

Received: 08 September 2025 Revised: 03 November 2025 Accepted: 30 December 2025 Published: 04 January 2026

© 2026 The authors. This is an open access article under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

1. Introduction

According to the World Health Organization, stroke is a global public health issue and a leading cause of long-term disability [1]. With the aging population, the number of chronic stroke survivors is expected to increase [2]. Motor impairments after stroke are often accompanied by spasticity, a condition in which muscles become excessively tense, leading to abnormal flexion and extension of the limbs [3]. Prolonged spasticity can cause contractures, further restricting movement [3]. Among impaired functions, the recovery of hand motor function is particularly challenging, as the finger has a complex structure and finger joints possess 23 degrees-of-freedom [4]. Nevertheless, restoring hand function is essential for performing daily activities that require fine motor skills and maintaining the quality of life in chronic stroke survivors [5,6]. Therefore, effective hand rehabilitation strategies are crucial.

Several approaches to upper-limb rehabilitation have been studied, including constraint-induced movement therapy [7,8,9], mirror therapy [10,11,12], bilateral arm training [13,14], and repetitive facilitated exercise (RFE) [15,16]. RFE involves providing external stimulation, such as tapping, rubbing, passive stretching, or slight resistance, to facilitate intended movements in the affected limb. Intensive stimulation can elicit spontaneous finger movements and promote functional recovery.

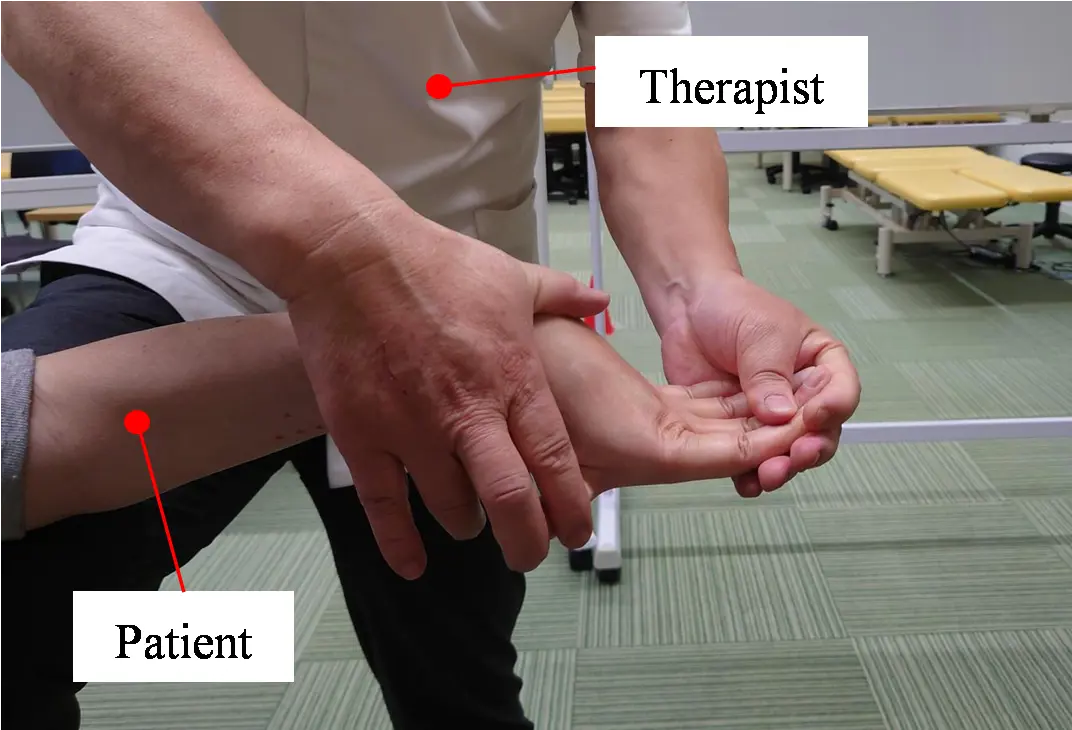

Strengthening the extensor muscles is necessary to restore hand-opening function. However, many chronic stroke survivors cannot voluntarily open their hands, making extensor training difficult. To address this issue, a finger extensor facilitation technique was developed, in which the therapist fixes the patient’s fingers in hyperextension while applying resistance at the metacarpophalangeal (MP) joints. This approach induces extensor activity via stretch reflexes and suppresses flexor overactivity [17,18,19]. Although effective, it requires lengthy, prolonged sessions and imposes a considerable physical burden on therapists. Consequently, there is an urgent need for a device or robotic system that can replicate and expand such interventions. In this study, this approach is referred to as manual therapy.

Recent studies have explored robot-assisted rehabilitation for post-stroke upper-limb and hand functions. Early developments include cable-driven systems such as HandCARE [20], clinical feasibility studies of hand robotic therapy [21], electromyography (EMG)-driven exoskeleton devices that enable task-oriented training [22], and a device that is actively controlled by the user’s own muscle signals HANDEXOS [23]. In Japan, wearable and mechanism-based devices have been introduced, including parallel-link wrist-training systems [24] and stretch reflex-facilitated finger extension devices [25]. Recently, advances in multimodal wearable sensors [26] and force-feedback glove systems [27] have expanded the scope of rehabilitation technologies. Systematic reviews and randomized controlled trials further supported the clinical effectiveness of different robotic approaches [28,29]. Comprehensive reviews highlighted both the current progress and future challenges in robot-assisted upper-limb rehabilitation [30]. However, most of these devices focus on strengthening extensor muscles through repeated flexion and extension exercises, which are unsuitable for patients who are unable to open their hands voluntarily. To our knowledge, no existing device promotes voluntary extensor activation while simultaneously suppressing abnormal flexor tension.

In a previous study, iPARKO, a device that simulates manual therapy, was developed and validated in three healthy participants [31]. Subsequent evaluations of its effectiveness were conducted on a group of six chronic stroke survivors. The results showed that training with iPARKO improved the active range of motion (AROM) for all participants, thereby confirming enhanced voluntary hand movements [32]. However, iPARKO has two major limitations. First, it is difficult to use with chronic stroke survivors with severe fingertip spasticity, as fixation is often difficult to achieve, and the fingers may slip off during training. Second, attaching paretic fingers requires fixing each spastic finger individually, which is inconvenient and time consuming. Moreover, clarifying the relationship between the pushing force and improvements in voluntary hand movement during training is of particular interest to medical professionals and is essential for enhancing the clinical value of iPARKO.

In this study, we developed iPARKO-2, a device designed to address the aforementioned limitations and investigated the relationship between pushing force and improvements in voluntary hand movement during training. This study is a pilot study aimed at technical validation and feasibility. Training was conducted with five chronic stroke survivors, each exhibiting different levels of pushing force. As a pilot study, the sample size was intentionally limited to the minimum required for exploratory analysis. The experimental design involved measuring changes in the AROM of four fingers before and after training to determine whether participants could perform voluntary movements. The AROM is defined as the range of motion achieved solely through the participants’ own muscle strength, without external assistance. In addition, extensor muscle activity was recorded during training and analyzed in relation to changes in the AROM.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Development of “iPARKO-2”

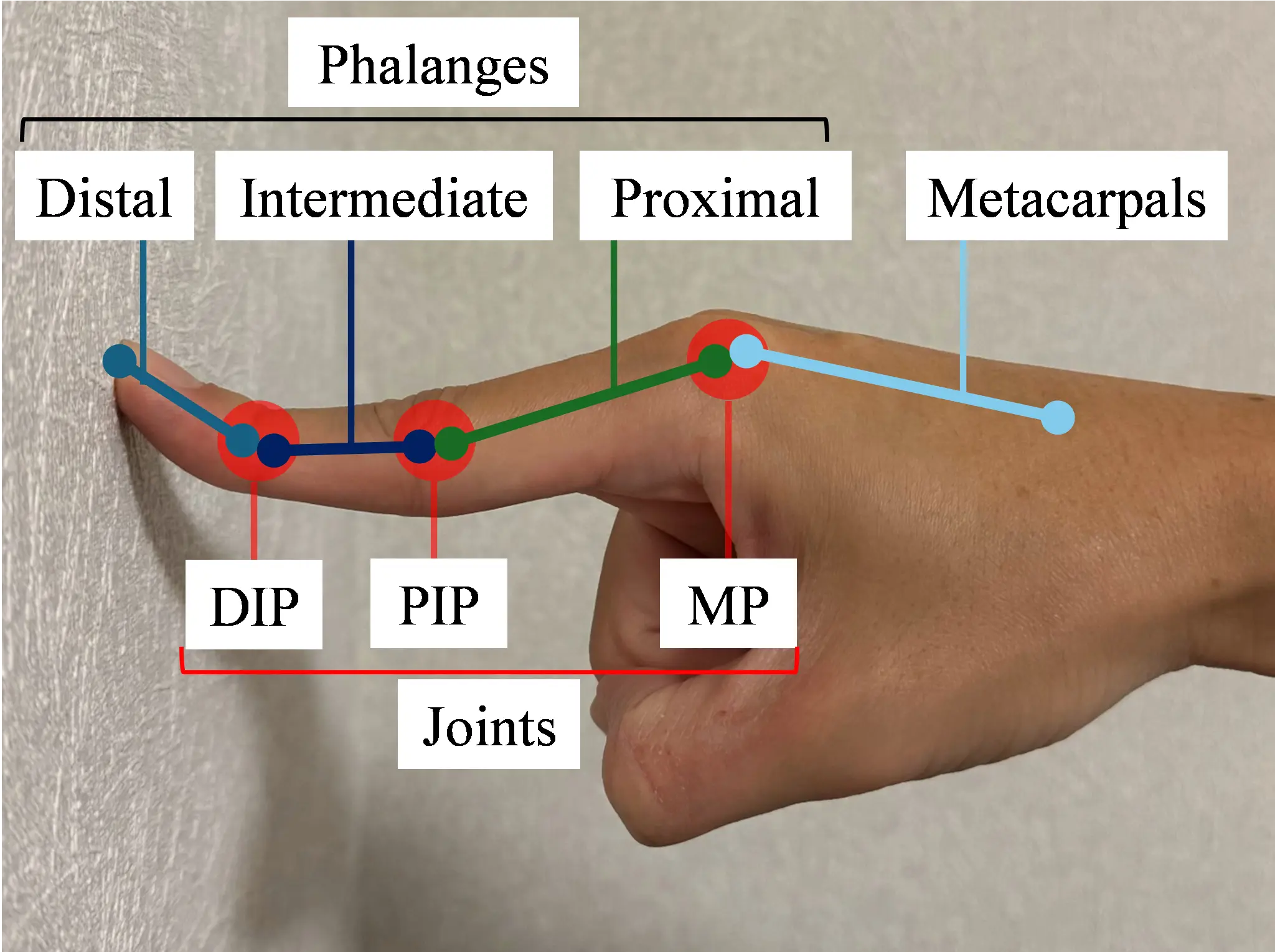

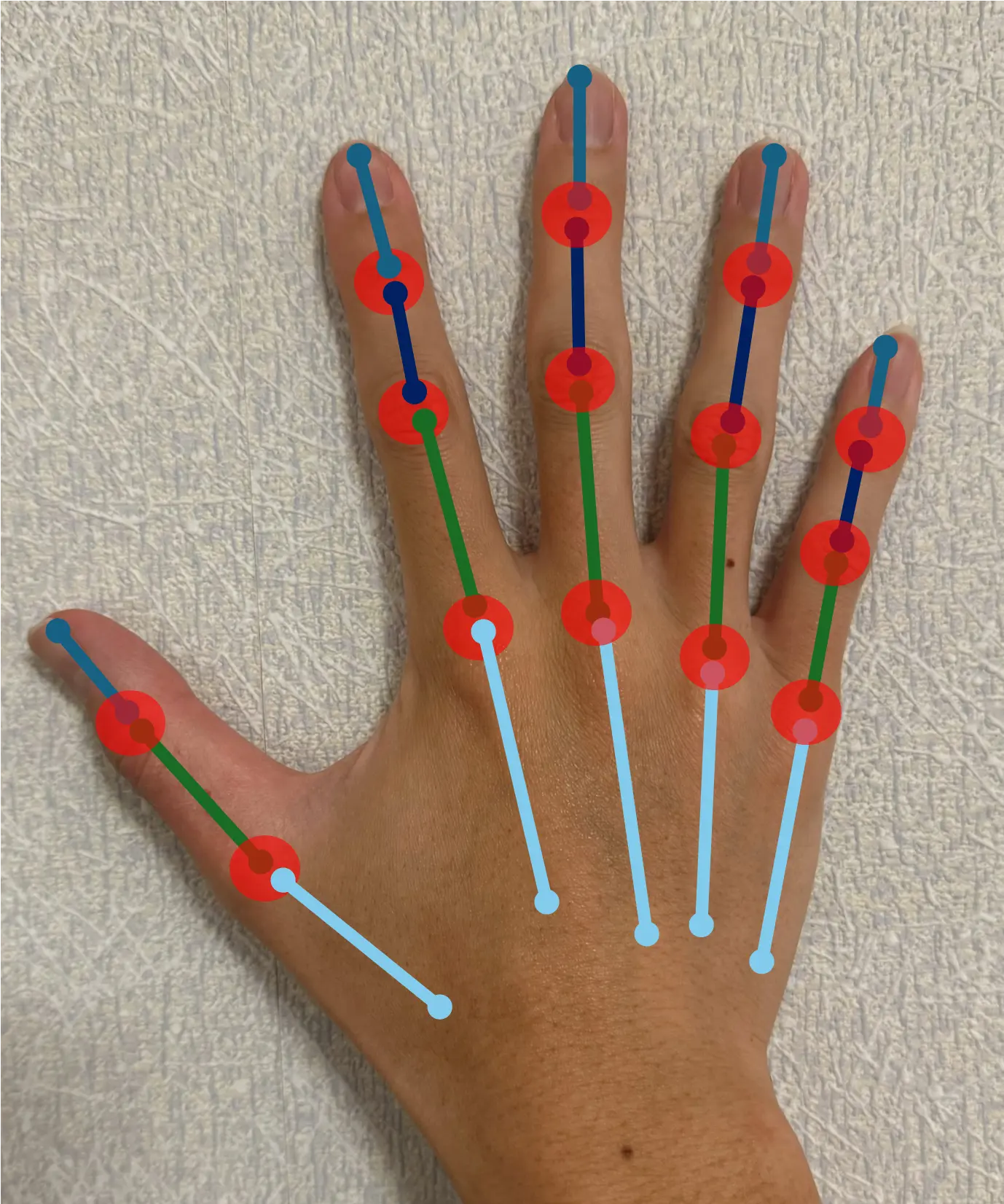

Manual therapy is first explained. Figure 1a shows the application of manual therapy to a patient. Figure 1b,c shows the hand bones and joints. This manual therapy facilitates the enhancement of voluntary hand movements in chronic stroke survivors who do not exhibit active hand opening. The therapist uses one hand to hold the proximal, intermediate, and distal phalanges of the patient’s paralyzed finger to maintain the distal interphalangeal (DIP) and proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joints in maximum extension and the MP joint in hyperextension. The therapist also supports the affected upper limb with the other hand. As the patient voluntarily moves their paralyzed hand forward, the therapist applies resistance to the MP joints from the fingertips. This resistance elicits a stretch reflex in the extensor muscles, causing them to contract and increase muscle activity. The four fingers are held in hyperextension, which facilitates extensor muscle contraction by relaxing them, while concurrently stretching the flexor muscles and inhibiting their contraction. Applying force to the MP joints from the fingertips under these conditions enhances the extensor muscle activity while suppressing the flexor muscle activity [19]. In a previous study, iPARKO was used to simulate manual therapy.

Two issues were identified with the original iPARKO. First, the application was challenging for chronic stroke survivors with strong fingertip spasticity because of the force applied from the fingertips to the MP joints in the hyperextended position of the phalanges of each finger. Second, there is a need to manually fix each finger to the iPARKO, which places a considerable burden on medical personnel.

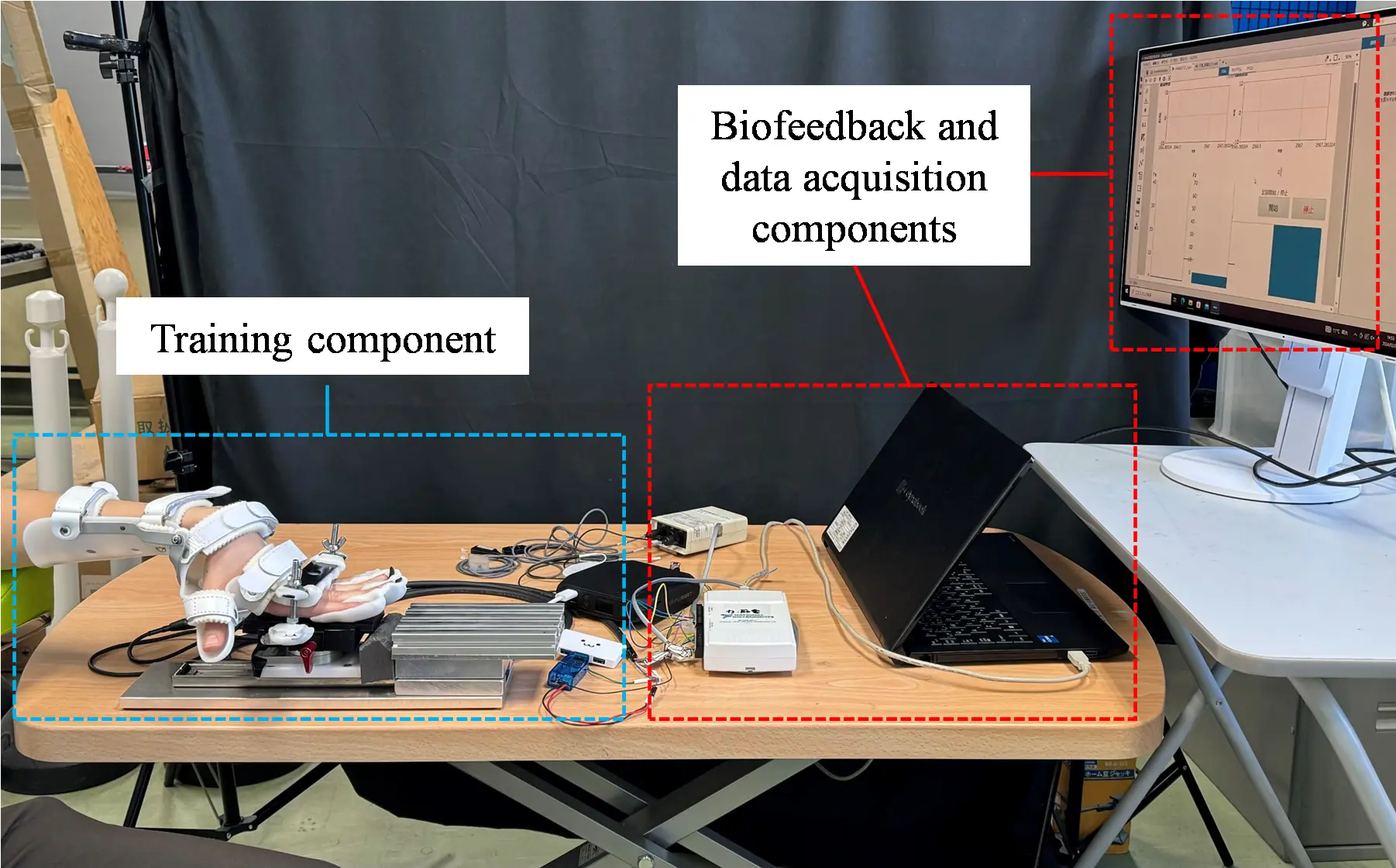

To address these limitations, the iPARKO-2 device was developed as an improved version of the original iPARKO. The design was modified to apply resistance from the proximal phalanges rather than the fingertips, ensuring effective force transmission from the proximal bone to the MP joint. Additionally, the device was redesigned to allow for the simultaneous fixation of the four fingers, reducing setup time and effort. As shown in Figure 2, iPARKO-2 includes training, biofeedback, and data acquisition components aligned with iPARKO [31]. In this study, the term “fingers” refers to the four fingers, excluding the thumb.

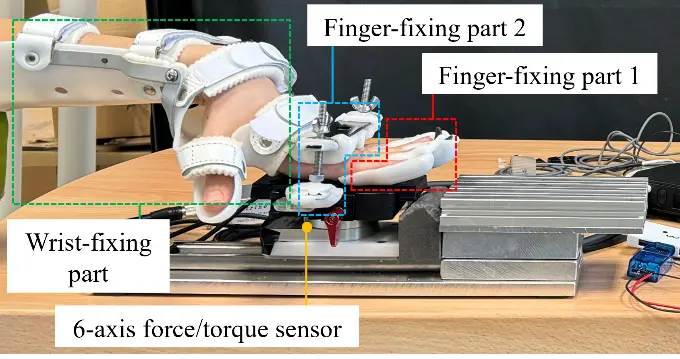

Figure 2 and Figure 3 illustrate the overall device and its individual components, respectively. Figure 2 shows the complete iPARKO-2 device, whereas Figure 3 details the individual training components, including finger-fixing parts 1 and 2 and the wrist-fixing part, as well as their arrangement.

iPARKO-2 incorporates two major engineering improvements over the original device:

-

Force Application from Proximal Phalanges: Unlike iPARKO, which applied resistance from the fingertips, iPARKO-2 applies resistance from the proximal phalanges to the MP joints. This design reduces finger slippage and enables training for patients with severe spasticity.

-

Simultaneous Finger Fixation: iPARKO-2 can fix all four fingers simultaneously using thermoplastic resin components (finger-fixing parts 1 and 2). In contrast, the original iPARKO required individual fixation of each finger, which was time-consuming and cumbersome.

By fixing the PIP and DIP joints while applying resistance from the proximal phalanges, iPARKO-2 more closely replicates manual finger extensor facilitation. This configuration enhances extensor muscle activation, allowing for effective training even in patients with severe spasticity.

|

|

|

|

(a) |

(b) |

(c) |

Figure 1. Application of finger extensor facilitation techniques to a patient and the structure of the bones and joints of the hand. (a) Finger extensor facilitation technique; (b) Index finger in hyperextended position; (c) Bones and joints of the hand.

2.2. Training Component

The training components consist of a finger-fixing part 1, finger-fixing part 2, and wrist-fixing part, as shown in Figure 3.

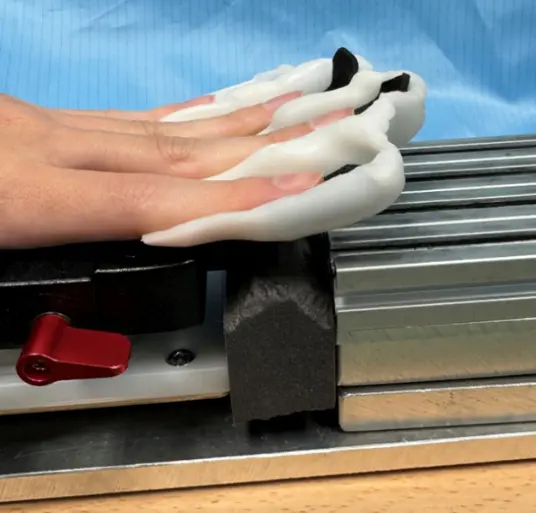

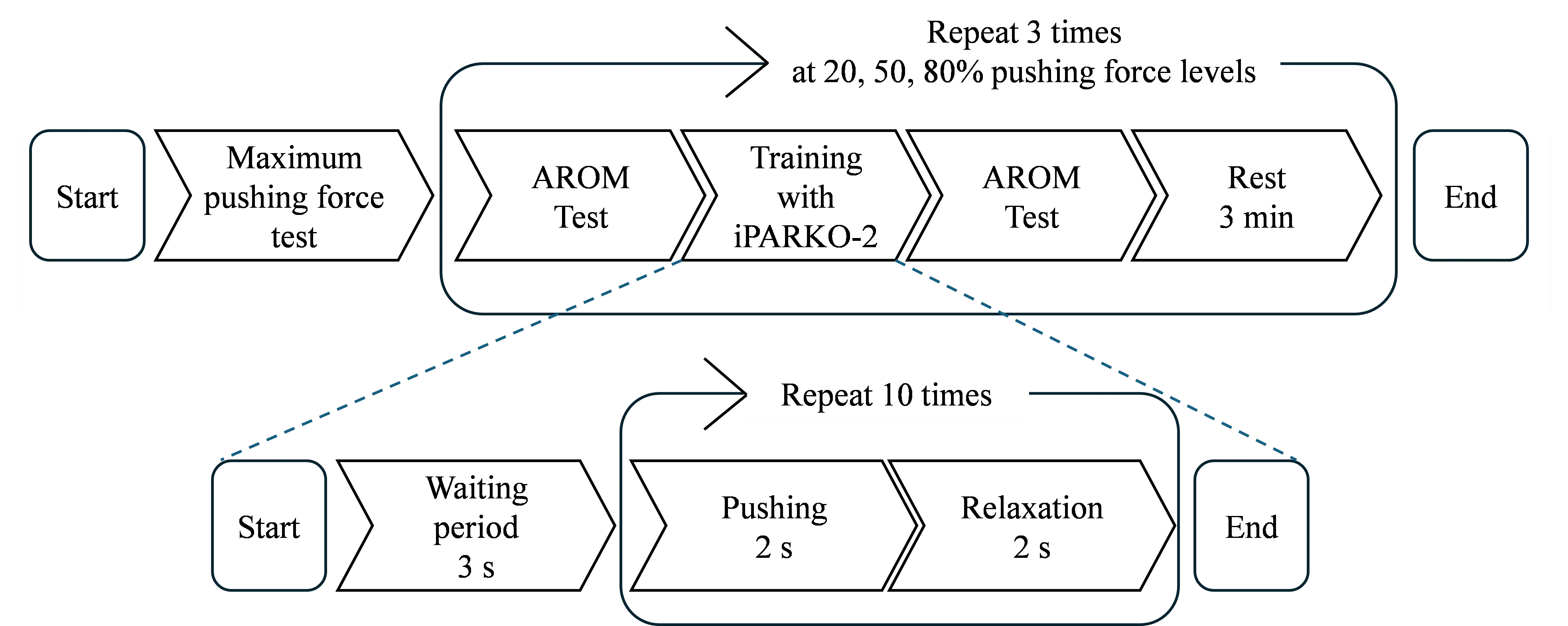

Figure 4 shows finger-fixing part 1 used for the distal phalanges and DIP joints, with the rest of the training components removed. The finger-fixing part 1 is made of thermoplastic resin and attached from the PIP joint to the fingertip. Unlike iPARKO, which requires the fixation of one fingertip at a time on a rubber band, iPARKO-2 simultaneously fixes the fingertips of four fingers at the DIP joints. In addition, because the finger-fixing part 1 is bent in the direction of hand extension, it plays the same role as the finger sack of iPARKO. This allows the PIP and DIP joints to be maintained in maximum extension, which is the same condition as in manual therapy.

Figure 5 shows finger-fixing part 2 used to fix the proximal phalanges and PIP joints, with the rest of the training components removed. The finger-fixing part 2 is also made of thermoplastic resin and consists of two plates. As shown in Figure 5, the PIP joints of the four fingers were pinched from above and below. This method simultaneously fixes the PIP joints of the four fingers, rather than fixing them individually. In this state, resistance was applied to the MP joint by pushing the hand forward. Unlike iPARKO, which applies force from the fingertips of the four fingers, this device applies force from the proximal phalanges, making it possible to apply force to chronic stroke survivors with strong fingertip spasticity. As described above, finger-fixing parts 1 and 2 can fix four fingers simultaneously. Therefore, the burden on chronic stroke survivors caused by fixing one finger at a time could be reduced.

The wrist-fixing part is attached to the chronic stroke survivor’s wrist to maintain the MP joint in a hyperextended position. A six-axis force/torque sensor (FFS055F251M8R0A6S; Leptrino Co., Ltd., Nagano, Japan) was attached to the lower part of finger-fixing part 2 to measure the force applied to the PIP and MP joints directly connected to it. Finger-fixing parts 1 and 2, and a six-axis force/torque sensor were fixed on a slide rail (FBW3590XRUU + 300 L; THK Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan), allowing the patient to smoothly move his or her hand forward. A sponge was attached to the tip of the slide rail to absorb the shock when the patient pushed forward, as shown in Figure 4. The firmness of the sponge was adjusted such that finger-fixing part 1, finger-fixing part 2, and the six-axis force/torque sensor moved approximately 5 mm on the slide rail when the patient pushed forward. Because of individual differences in the joint angles of the fingers in the hyperextended position, the height of the training component must be adjusted to enable the reproduction of manual therapy. To this end, a height-adjustable table was utilized.

2.3. Biofeedback and Data Acquisition Components

iPARKO-2, similar to iPARKO, measures the extensor and flexor muscle activity during training using a portable EMG sensor (OPE-2; Unique Medical Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). The EMG sensor consists of a surface electrode and preamplifier. The six-axis force/torque sensor was used to measure the pushing force.

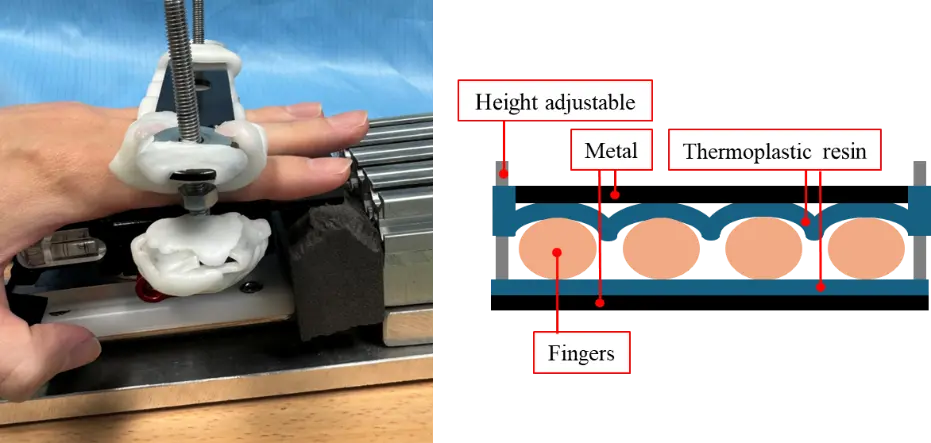

The data acquisition component consisted of a data acquisition system (USB6211; National Instruments Corp., Austin, TX, USA) that obtained data from the EMG and six-axis force/torque sensor, a personal computer, and a monitor. The sampling frequency of the measurements was 1000 Hz. The measurement data collected by the data acquisition system were displayed on the monitor, as shown in Figure 6. The EMG signals of the extensor and flexor muscles, as well as the pushing force and its desired value, could be monitored.

3. Experiments

3.1. Purpose

This study aims to compare improvements in hand voluntariness in five chronic stroke survivors before and after training with iPARKO-2 at different pushing forces. The AROM was used to evaluate hand voluntariness, and the amount of change in the AROM before and after training was used to improve hand voluntariness. Information on the participants is listed in Table 1. The passive range of motion (PROM) refers to the range of motion of a joint obtained by moving the joint with an external force or the hands of another person. The PROM was measured in advance by the therapist using a goniometer. All participants were paralyzed in their left hand. All participants provided informed consent prior to participating in the study. The study was conducted in accordance with the protocol approved by the Ethics Committee of the Nagoya Institute of Technology (Approval number 2020-001).

Table 1. Information on the five participants.

|

No. |

Sex |

Age |

Dominant Hand |

Paralyzed Hand |

PROM [°] |

Maximum Pushing Force [N] |

Period of Onset [Years] |

Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1 |

F |

59 |

R |

L |

15 |

40 |

10 |

Lacunar infarction |

|

2 |

M |

69 |

R |

L |

20 |

80 |

8 |

Lacunar infarction |

|

3 |

M |

56 |

R |

L |

65 |

60 |

13 |

Cerebral hemorrhage |

|

4 |

F |

69 |

R |

L |

40 |

28 |

13 |

Cerebral hemorrhage |

|

5 |

M |

66 |

R |

L |

53 |

40 |

17 |

Cerebral infarction |

|

Mean ± SD |

M:3, F:1 |

63.8 ± 5.3 |

R:5, L:0 |

R:0, L:5 |

38.6 ± 19.0 |

49.6 ± 18.3 |

12.2 ± 3.1 |

- |

3.2. Methods

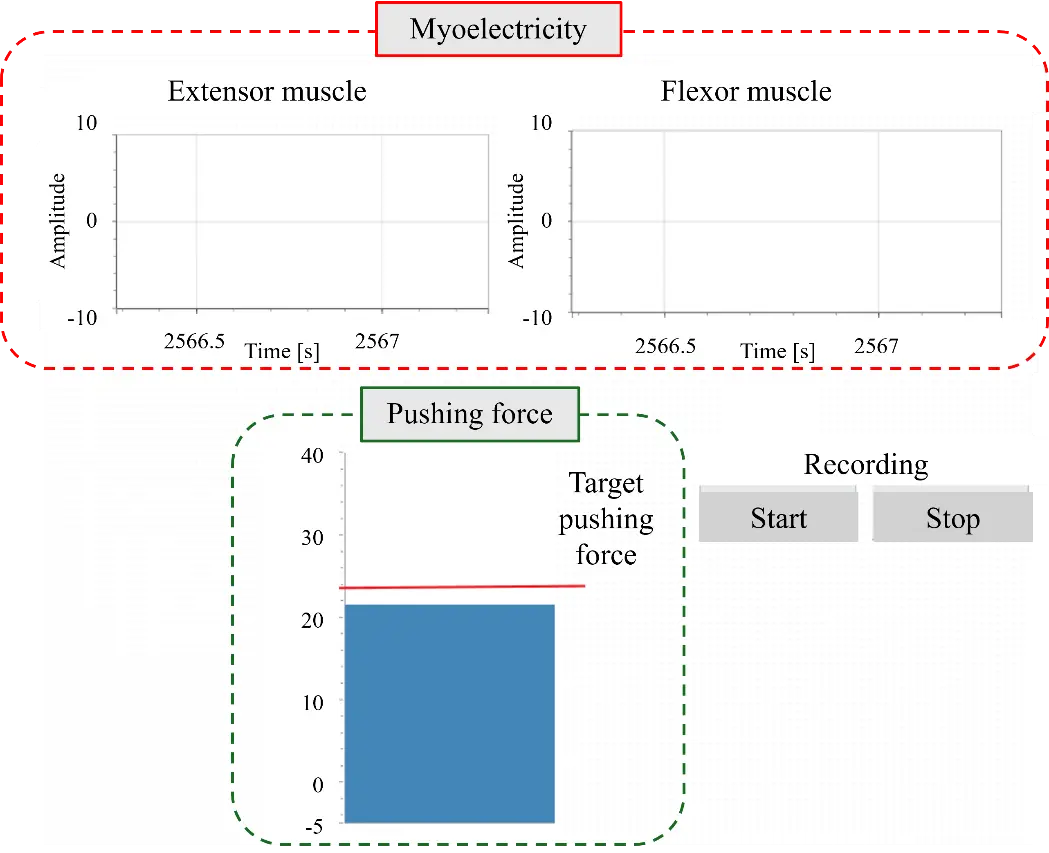

The experimental procedure is illustrated in Figure 7. The participants initially underwent a maximum pushing force test as a preliminary step, followed by training with iPARKO-2 at three different target force levels. The AROM test was performed before and after each training session.

The maximum pushing force test was performed in the same posture as the iPARKO-2 training, which is described below. In this posture, participants were instructed to slowly push their hands forward with maximal pain-free effort for 3 s upon the supervisor’s cue. The highest value recorded during this 3 s period was defined as the maximum pushing force.

For iPARKO-2 training, surface EMG electrodes were attached to the participant’s left arm to measure extensor muscle activity. To ensure consistency, the electrodes remained in place throughout all three training sessions, each with a different target pushing force level. This approach prevented variability from repositioning. The wrist-fixing component was secured to maintain the wrist angle, followed by fixing the left hand’s PIP joint in the finger-fixing part 2 and the fingertips in the finger-fixing part 1.

The training protocol consisted of pushing exercises at three target force levels: 20%, 50%, and 80% of the maximum pushing force of each participant. To account for individual differences in muscle strength, the pain-free training intensity was determined based on the maximum pushing force of each participant. To offset order effects, participants 1–3 were trained in the sequence of 80%, 50%, and 20%, while participants 4 and 5 followed the reverse sequence (20%, 50%, and 80%). Previous studies have distinguished these three levels when evaluating the reliability of surface EMG variables at varying contraction intensities. These findings support the validity of these levels in characterizing neuromuscular function [33].

As illustrated in Figure 7, a single training session comprised an initial 3 s waiting period and 10 sets of pushing and relaxation. Each set consisted of 2 s of pushing and 2 s of relaxation, for a total of 4 s per set. A metronome indicated the initiation of pushing and relaxation. The sampling time was set to 0.001 s. The pushing forces were 20%, 50%, and 80% of the maximum pushing force. During training, participants were instructed to push their hands forward to achieve the indicated pushing force while observing their actions on the monitor. Intervals of 3 min were allotted for rest between the three training sessions. During the rest period, the participant’s hand was removed from iPARKO-2.

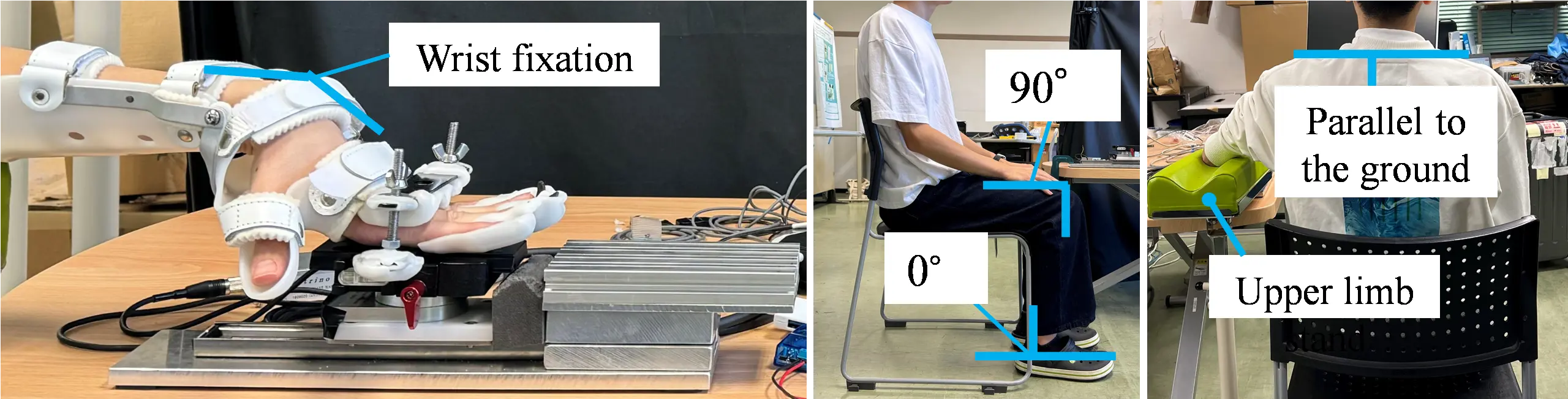

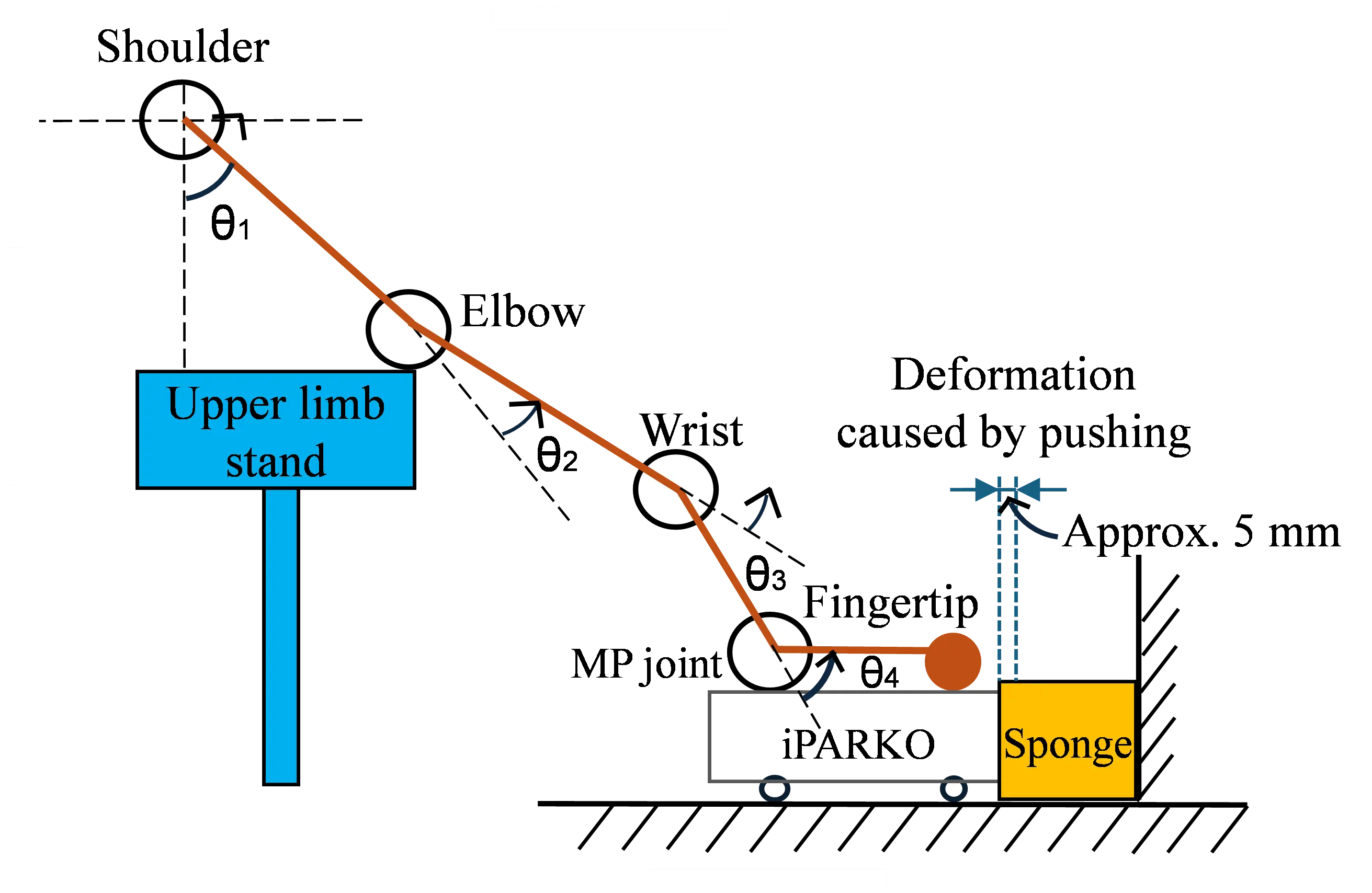

3.3. Experimental Posture

The posture during the experiment is shown in Figure 8. Participants sat in a chair adjusted so that the ankle joint was at 0° and the knee joint was at 90° flexion. Their legs were shoulder-width apart, and the soles of their feet were flat on the floor. The shoulder joint was held in a position without elevation. The training component of iPARKO-2 was placed next to the participant’s body. Participants were also instructed to place their elbows on the upper-limb stand, maintain a straight posture, and avoid twisting their trunk. The monitor was placed in front of the participant, and the height was adjusted so that the participant could easily see the screen.

In addition, the upper limb is represented by the four-joint link model, as shown in Figure 9. Let the flexion angle of the shoulder joint be $${\theta }_{1}$$, the flexion angle of the elbow joint be $${\theta }_{2}$$, the extension angle of the wrist joint be $${\theta }_{3}$$, and the extension angle of the MP joint be $${\theta }_{4}$$. In addition, for all joint angles, the counterclockwise direction is positive. The following relationship exists between these angles.

We assumed $${\theta }_{1}=80°$$, $${\theta }_{2}=0°$$, and $${\theta }_{4}$$ is the PROM of each participant. $${\theta }_{4}$$ is uniquely determined from Equation (1). Throughout the experiment, participants moved their hands forward and were placed on the training component. The distance traveled was approximately 5 mm. As the forearm moves, the angles of the shoulder, elbow, and wrist change. The change in angle of the shoulder was the largest, extending approximately 5°. In comparison, the elongation of the elbow and wrist was small.

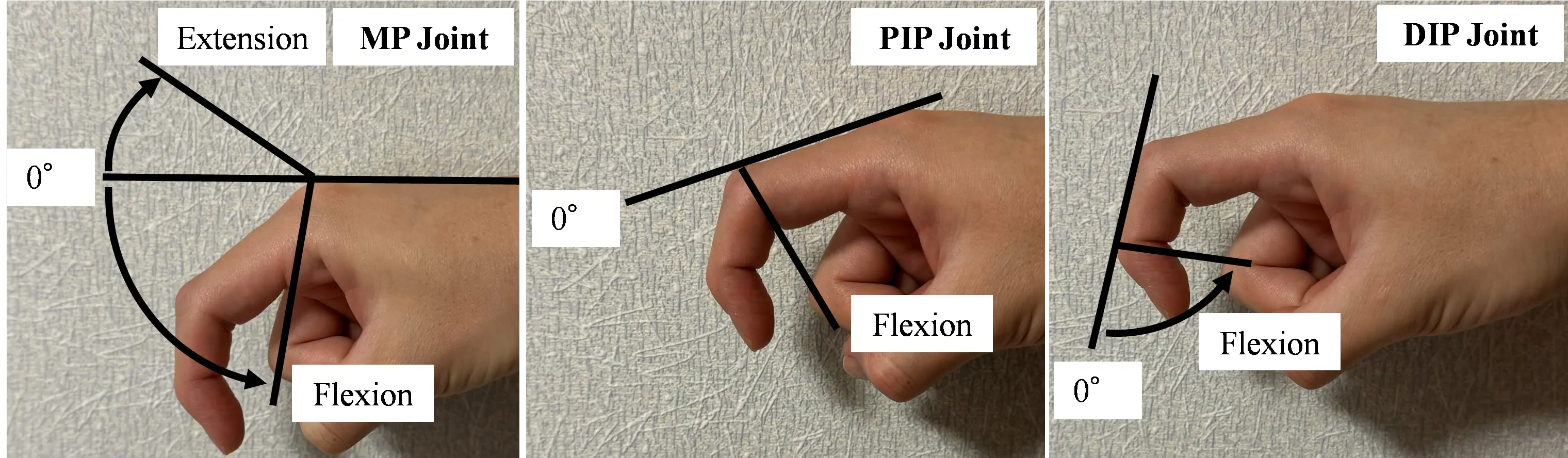

3.4. Evaluation Method

To clarify the relationship between the pushing force and improvements in voluntary hand movement during training, the AROM was measured before and after the intervention. Twelve measurement points were obtained at the MP, PIP, and DIP joints of the four fingers of the participant’s paralyzed hand, excluding the thumb. Measurements were performed by the therapist using a goniometer. The angles are shown in Figure 10, where the fully extended position was 0°, the angle in the extension direction was positive, and the angle in the flexion direction was negative with respect to the fully extended position. To evaluate whether the patient could voluntarily perform movements, the total active motion (TAM) was used, defined as the sum of the active ranges of motion of the MP, PIP, and DIP joints of each digit. This definition follows the standards of the American Society for Surgery of the Hand [34]. The methodology is grounded in the foundational work by Hume et al. (1990), who quantified the functional ranges of motion required for activities of daily living in these joints [35]. The change in TAM before and after training was defined as the improvement in TAM; in other words, the greater the increase in TAM, the greater the improvement in volitional control.

The extensor muscle activity during the training period was measured using a surface EMG sensor. Due to the variability in paralysis severity, the absolute magnitude of EMG signals in the affected hand muscles varied among participants and could not be directly compared with those of healthy individuals. Therefore, we focused on within-subject changes and correlations rather than absolute values. To account for the inconsistent timing of voluntary movements in participants with paralysis, the first and last 0.5 s of each 2-s pushing interval were excluded when calculating the average EMG for each set. The quantification of muscle activity was determined by the arithmetic mean of 10 sets, with the absolute average value of 1 s. This approach reduced the influence of inconsistent onset and offset timing, allowing for a more reliable quantification of relative muscle activity during the task. It is important to note that the level of muscle activity varies significantly among individuals. Although normalization by the maximum voluntary contraction (MVC) is typically used to account for such variations, quantifying MVC in chronic stroke survivors posed a significant challenge due to restricted wrist range of motion and variability in the extent of paralysis. Consequently, normalization was not performed in this study.

Due to the small sample size and the exploratory nature of this pilot study, descriptive statistics and correlation analyses were primarily used. Effect sizes (Cohen’s d) were also calculated to supplement these analyses and to provide an estimate of the magnitude of change under different pushing force levels.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Relationship between Pushing Force and AROM

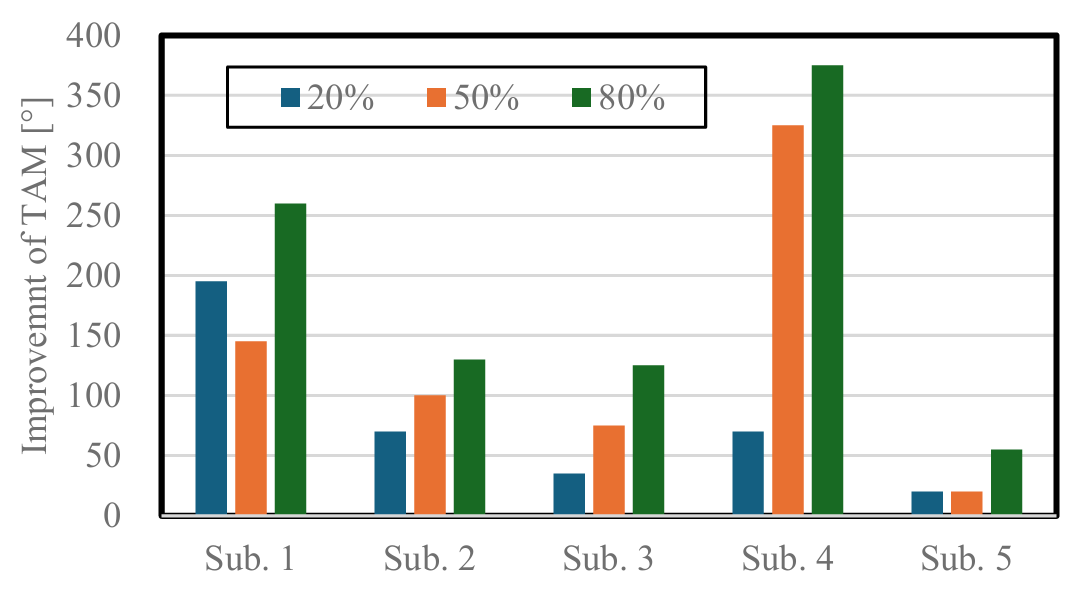

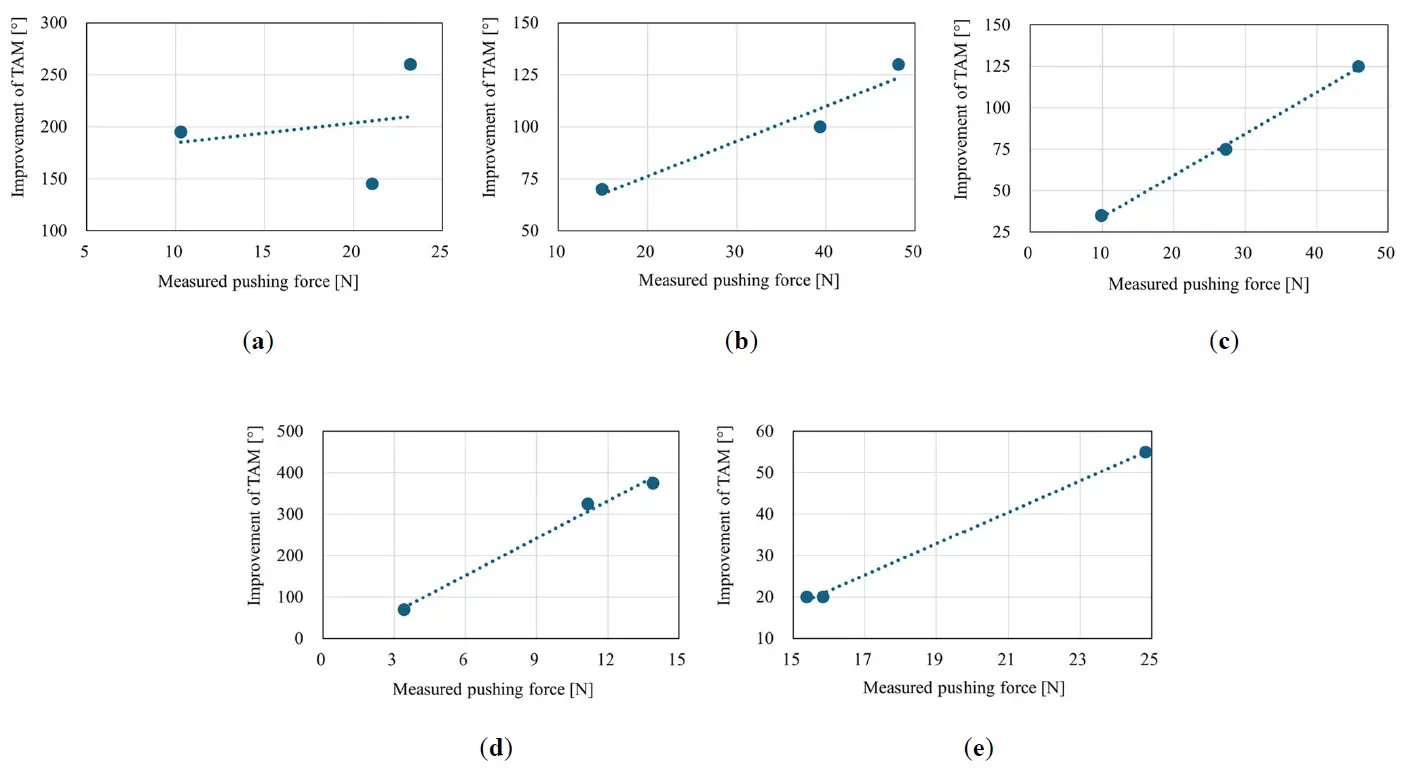

The TAM before and after training at the three target pushing force levels for each of the five participants, as well as the improvement in the TAM, are shown in Table 2 and Figure 11, respectively. The mean TAM improvements for the five participants during training at the three target pushing force levels were 78.0 ± 69.0°, 133.0 ± 116.4°, and 189.0 ± 127.6°. The improvement in the TAM showed an increasing trend with increasing pushing force. This indicates the potential effectiveness of training with pushing forces close to the maximum pushing force. At 50% of the maximum pushing force, the improvement in the TAM was greater than 20% for all four participants, except Participant 1. At 80% of the maximum pushing force, the improvement in the TAM was greater than that at 20% and 50% for all participants. Although the observed improvements in TAM suggest enhanced voluntary hand motion, the clinical significance of these changes should be interpreted cautiously. Hume et al. (1990) [35] reported functional ranges of motion for daily hand activities, indicating that certain thresholds of TAM improvement are necessary to achieve meaningful functional gains. Our pilot data provide preliminary indications, but further studies are required to establish clinically meaningful changes in chronic stroke survivors.

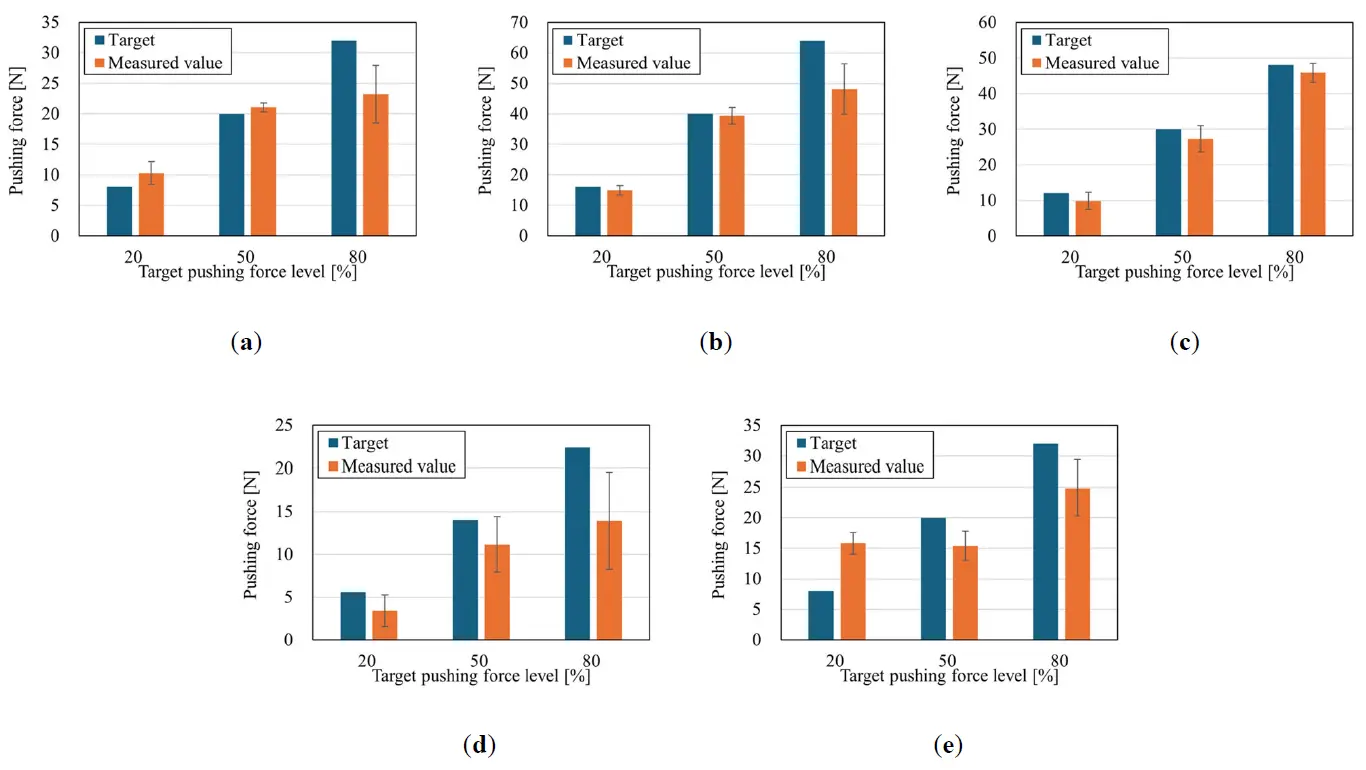

During training, participants adjusted their pushing force to match the target value. This may result in individual differences in the actual pushing force. In other words, there were differences in control performance due to the disability level of participants. The target and measured pushing forces for the three training sessions at the three target pushing force levels for each participant are shown in Figure 12. The bar on the measured pushing force indicates the standard deviation. As with the quantitative evaluation method of muscle activity, each measured pushing force is the average of 10 sets of absolute average values for 1 s, excluding the first and last 0.5 s of the 2 s period; one set of pushing force is defined as the average of the 10 sets of pushing force. As shown in Figure 12, the ability to adjust the pushing force to the target value varies among individuals. Participant 3 has a high adjustment capability because their pushing force is close to the target value. On the other hand, Participants 1, 2, 4, and 5 tended to have higher actual pushing forces as the target values increased. However, when the target value is large, the error and variation increase. This indicated that their ability to adjust to large forces was inferior. In particular, Participant 5 had an inferior adjustment capability for both small and large pushing forces.

The scatter plot of the measured pushing force versus the improvement in the TAM for the three training sessions with different pushing force levels is shown in Figure 13. A linear approximation curve is also presented. The correlation coefficients between the measured pushing force and improvement in the TAM for the five participants were 0.23, 0.96, 1.00, 0.99, and 1.00. Figure 13 shows that the improvement in the TAM increased as the pushing force increased, except for Participant 1. The relationship between the measured pushing force and the improvement in TAM, as shown in Figure 13, was examined using Cohen’s d. When comparing the highest and lowest pushing force levels among the small, medium, and large conditions, Cohen’s d was approximately 1.01, indicating a large effect (d > 0.8). A d value greater than 1 suggests that the change from pre- to post-intervention (mean difference) exceeds individual variability (standard deviation), indicating that the intervention effect is very strong and surpasses individual differences. These analyses are intended to inform the design of future larger-scale studies.

Table 2. Relationship between target pushing-force levels and TAM before and after training for each participant (Diff: difference between before and after training).

|

Pushing Force [%] |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

20 |

50 |

80 |

|||||||

|

Sub No. |

Pre [°] |

Post [°] |

Diff [°] |

Pre [°] |

Post [°] |

Diff [°] |

Pre [°] |

Post [°] |

Diff [°] |

|

1 |

795 |

990 |

195 |

850 |

995 |

145 |

750 |

1010 |

260 |

|

2 |

820 |

890 |

70 |

795 |

895 |

100 |

780 |

910 |

130 |

|

3 |

940 |

975 |

35 |

900 |

975 |

75 |

875 |

1000 |

125 |

|

4 |

540 |

610 |

70 |

570 |

895 |

325 |

645 |

1020 |

375 |

|

5 |

970 |

990 |

20 |

970 |

990 |

20 |

970 |

1025 |

55 |

Figure 11. Relationship between target pushing force levels and improvement in the TAM for each participant.

Figure 12. Relationship between target pushing force levels and measured pushing force for each participant. (a) Participant 1; (b) Participant 2; (c) Participant 3; (d) Participant 4; (e) Participant 5.

Figure 13. Scatterplot of the relationship between the measured pushing force and improvement in the TAM. (a) Participant 1; (b) Participant 2; (c) Participant 3; (d) Participant 4; (e) Participant 5.

4.2. Relationship between Pushing Force and Muscle Activity

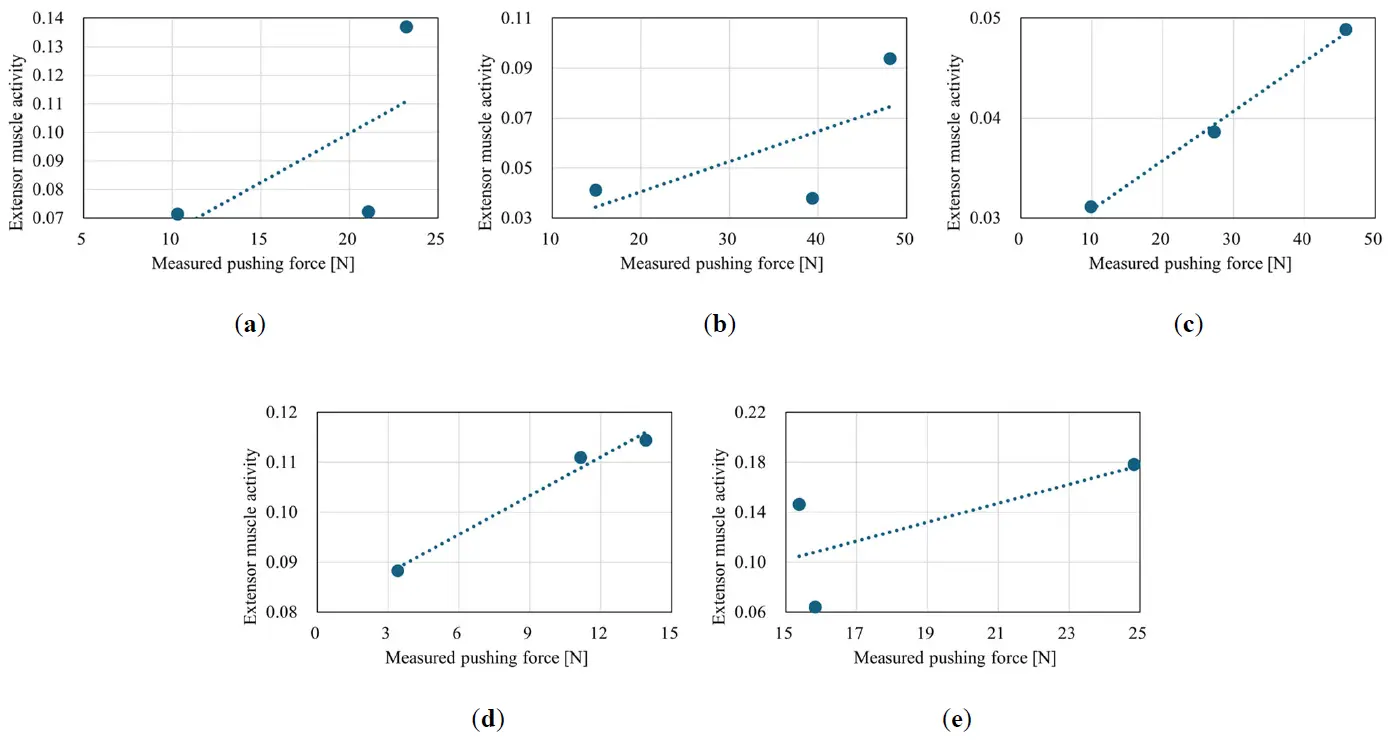

The relationship between the measured pushing force and extensor muscle activity was examined. Figure 14 shows a scatterplot of this relationship during training for the five participants, along with a linear approximation curve. The correlation coefficients between the measured pushing force and extensor muscle activity for the five participants were 0.58, 0.84, 0.91, 0.95, and −0.07. As shown in Figure 14, the extensor muscle activity increased as the measured pushing force increased, except for Participants 1 and 5.

These results suggest that muscle activity increased as the pushing force increased, and that the amount of muscle activity affected the improvement in the TAM.

The observed increase in TAM under higher pushing force may be partly explained by involuntary reflex mechanisms rather than voluntary motor control alone. When the fingers are held in extension, and axial pressure is applied to the fingertips, the finger extensors can be activated through the stretch reflex. The axial load produces a subtle and unexpected stretch around the MP and IP joints, which is detected by muscle spindles and transmitted via Ia afferents to the spinal cord, resulting in excitation of the extensor α-motor neurons [36,37]. Reflex activation of finger muscles in force-related tasks has also been demonstrated in humans [38]. In addition, axial fingertip loading may trigger automatic postural reflexes that stabilize the limb against external forces, involving the coordinated activation of multiple upper-limb muscles, including the finger extensors [39]. Such reflex pathways are known to remain relatively preserved after stroke and may support or augment voluntary motor performance [40]. These mechanisms offer a plausible explanation for the increased TAM observed in this study and indicate that reflex-driven motor responses may contribute to movement outcomes during the task.

Figure 14. Scatterplot of the relationship between the measured pushing force and extensor muscle activity. (a) Participant 1; (b) Participant 2; (c) Participant 3; (d) Participant 4; (e) Participant 5.

4.3. Usability and Fixation Efficiency of iPARKO-2

In this study, we employed the newly developed iPARKO-2. During training, participants’ fingertips remained securely attached to the device throughout the sessions. The fixation time was reduced by approximately 60%, from an average of 5 min to 2 min, indicating that iPARKO-2 effectively addresses the limitations of the original iPARKO device. Furthermore, all participants reported no pain or discomfort, and no adverse events were observed. Feedback from therapists indicated that iPARKO-2 reduced setup and fixation time, improved stability during training, and was easier to operate compared with the original device, suggesting enhanced clinical usability.

4.4. Limitations

This study included only five participants, which limits the generalizability of the findings. Therefore, the results should be interpreted as preliminary evidence from a pilot study focused on technical validation and feasibility. Future studies with larger sample sizes are necessary to confirm the observed relationships between pushing force and improvements in TAM. A control group was not included in this pilot study. Therefore, the relative efficacy of iPARKO-2 compared with conventional manual therapy or standard rehabilitation cannot be determined. Future studies should include appropriate control conditions to assess comparative effectiveness. This study assessed only the immediate effects of iPARKO-2 training. Whether the observed improvements in TAM persist beyond single-session training remains unclear and warrants investigation in future longitudinal studies.

The rest interval between the three target-force training sessions was 3 min. While we aimed to minimize carryover effects, we cannot exclude the possibility that residual effects from previous sessions, such as neural excitation or fatigue, may have influenced performance in subsequent sessions. Future studies should examine the optimal rest period to reduce potential carryover effects and allow for independent assessment of each target force level. Furthermore, iPARKO-2 is currently a prototype and can be further refined. Potential improvements include: (1) adjustable force calibration to enable individualized therapy, and (2) miniaturization of the device to enhance portability and usability. These enhancements are planned for future iterations.

5. Conclusions

In this study, we developed a novel finger extensor facilitation training device, iPARKO-2, designed for use in chronic stroke survivors exhibiting strong spasticity. The present study investigated the relationship between the pushing force during training and improvements in the TAM in five participants with chronic stroke. The findings indicated that an augmented pushing force was associated with elevated muscle activity, and the extent of muscle activity influenced the degree of improvement in the TAM. In addition, iPARKO-2 exhibited enhanced usability and fixation efficiency compared with the original iPARKO.

Future studies will examine the effects of various manual therapy conditions on voluntary hand control. The objective of these studies is to identify training methods that could further enhance hand function in chronic stroke survivors. While the immediate effects of training were confirmed in this study, further investigation is warranted to ascertain the long-term effects and to explore more effective training protocols that would improve overall treatment efficacy.

Statement of the Use of Generative AI and AI-Assisted Technologies in the Writing Process

During the preparation of this manuscript, the author(s) used ChatGPT (OpenAI) in order to improve the clarity, grammar, and readability of the text through language polishing and stylistic refinement. After using this tool/service, the author(s) reviewed and edited the content as needed and take(s) full responsibility for the content of the published article.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank all participants for their valuable contributions to this study.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.M. and H.T.; Methodology, S.I. and R.Y.; Software, S.I.; Validation, Y.M. and H.T.; Formal Analysis, S.I. and R.Y.; Investigation, S.I., R.Y. and H.T.; Resources, Y.M.; Data Curation, Y.M.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, Y.M.; Writing—Review & Editing, S.I., R.Y. and H.T.; Visualization, S.I.; Supervision, Y.M.; Project Administration, Y.M.; Funding Acquisition, Y.M.

Ethics Statement

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Nagoya Institute of Technology on 21 July 2020 (Approval No.: 2020-001).

Informed Consent Statement

All participants provided written informed consent before the measurements.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Funding

This research was funded by the JSPS Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (19K12878).

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- World Health Organization. Global Status Report on Noncommunicable Diseases 2014; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Katan M, Luft A. Global burden of stroke. Semin. Neurol. 2018, 38, 208–211. DOI:10.1055/s-0038-1649503 [Google Scholar]

- Feldman RG, Young RR, Koella WP. Spasticity, Disordered Motor Control; Year Book Medical Publishers, Inc.: Chicago, IL, USA, 1980; pp. 485–494. [Google Scholar]

- Gustus A, Stillfried G, Visser J, Jorntell H, van der Smagt P. Human hand modelling: Kinematics, dynamics, applications. Biol. Cybern. 2012, 106, 741–755. DOI:10.1007/s00422-012-0532-4 [Google Scholar]

- Kim D. The effects of hand strength on upper extremity function and activities of daily living in stroke patients, with a focus on right hemiplegia. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2016, 28, 2565–2567. DOI:10.1589/jpts.28.2565 [Google Scholar]

- Vandana Y, Charu G, Ravinder Y. Evolution in hemiplegic management: A review. Int. J. Health Sci. Res. 2018, 8, 360–369. [Google Scholar]

- Chuang HC, Ada L. Constraint-induced movement therapy improves upper limb activity and participation in hemiplegic cerebral palsy: A systematic review. J. Physiother. 2016, 62, 130–137. DOI:10.1016/j.jphys.2016.05.013 [Google Scholar]

- Taub E, Miller NE, Novack TA, Cook EW, Fleming WC, Nepomuceno CS, et al. Technique to improve chronic motor deficit after stroke. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 1993, 74, 347–354. [Google Scholar]

- Kwakkel G, Veerbeek JM, van Wegen EEH, Wolf SL. Constraint-induced movement therapy after stroke. Lancet Neurol. 2015, 14, 224–234. DOI:10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70160-7 [Google Scholar]

- Shafqatullah J, Aatik A, Haider D, Shehla G. A randomized control trial comparing the effects of motor relearning programme and mirror therapy for improving upper limb motor functions in stroke patients. J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 2019, 69, 1242–1245. [Google Scholar]

- Arya KN. Underlying neural mechanisms of mirror therapy: Implications for motor rehabilitation in stroke. Neurol. India. 2016, 64, 38–44. DOI:10.4103/0028-3886.173622 [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Cruzado D, Merchan-Baeza JA, Gonzalez-Sanchez M, Cuesta-Vargas AI. Systematic review of mirror therapy compared with conventional rehabilitation in upper extremity function in stroke survivors. Aust. Occup. Ther. J. 2017, 64, 91–112. DOI:10.1111/1440-1630.12342 [Google Scholar]

- Lee MJ, Lee JH, Kim HM, Lee SM. Effectiveness of bilateral arm training for improving extremity function and activities of daily living performance in hemiplegic patients. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2017, 26, 1020–1025. DOI:10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2016.12.008 [Google Scholar]

- McCombe Waller S, Whitall J. Bilateral arm training: Why and who benefits? NeuroRehabilitation 2008, 23, 29–41. DOI:10.3233/NRE-2008-23104 [Google Scholar]

- Kawahira K, Shimodozono M, Etoh S, Kamada K, Noma T, Tanaka N. Effects of intensive repetition of a new facilitation technique on motor functional recovery of the hemiplegic upper limb and hand. Brain Inj. 2010, 24, 1202–1213. DOI:10.3109/02699052.2010.506855 [Google Scholar]

- Wada Y, Ikegami S, Ishikawa S, Furiya Y, Kawahira K. Anti-spastic effects of repetitive facilitative exercise on hemiplegic limbs of patients with chronic stroke. Rigakuryoho Kagaku. 2019, 34, 569–574. DOI:10.1589/rika.34.569 [Google Scholar]

- Tanabe H. The Approach of Reorganization of the Human Central Nervous System; Human Press: Tokyo, Japan, 2016; pp. 88–94. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Tanabe H, Ikuta M, Morita Y. Validation of the efficiency of a robotic rehabilitation training system for recovery of severe plegie hand motor function after a stroke. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Rehabilitation Robotics, London, UK, 17–20 July 2017; pp. 579–584. DOI:10.1109/ICORR.2017.8009310 [Google Scholar]

- Tanabe H, Ikuta M, Mikawa T, Kondo A, Morita Y. Application of a robotic rehabilitation training system for recovery of severe plegie hand motor function after a stroke. Med. Robot. New Achiev. 2018, 1, 1–12. DOI:10.5772/intechopen.82189 [Google Scholar]

- Dovat L, Lambercy O, Gassert R, Maeder T, Milner T, Leong TC, et al. HandCARE: A cable-actuated rehabilitation system to train hand function after stroke. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2008, 16, 582–591. DOI:10.1109/TNSRE.2008.2010347 [Google Scholar]

- Sale P, Lombardi V, Franceschini M. Hand robotics rehabilitation: Feasibility and preliminary results of a robotic treatment in patients with hemiparesis. Stroke Res. Treat. 2012, 2012, 820931. DOI:10.1155/2012/820931 [Google Scholar]

- Ho NSK, Tong KY, Hu XL, Fung KL, Wei XJ, Rong W, et al. An EMG-driven exoskeleton hand robotic training device on chronic stroke subjects: Task training system for stroke rehabilitation. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Rehabilitation Robotics, Zurich, Switzerland, 29 June–1 July 2011; p. 5975340. DOI:10.1109/ICORR.2011.5975340 [Google Scholar]

- Chiri A, Vitiello N, Giovacchini F, Roccella S, Vecchi F, Carrozza MC. Mechatronic design and characterization of the index finger module of a hand exoskeleton for post-stroke rehabilitation. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2012, 17, 884–894. DOI:10.1109/TMECH.2011.2144614 [Google Scholar]

- Kitano Y, Tanzawa T, Yokota K. Development of wearable rehabilitation device using parallel link mechanism: Rehabilitation of compound motion combining palmar/dorsi flexion and radial/ulnar deviation. Robomech J. 2018, 5, 18. DOI:10.1186/s40648-018-0109-7 [Google Scholar]

- Yu Y, Iwashita H, Kawahira K, Hayashi R. Development of functional recovery training device for hemiplegic fingers with finger-expansion facilitation exercise by stretch reflex. Trans. Soc. Instrum. Control Eng. 2012, 48, 413–422. DOI:10.9746/sicetr.48.413 [Google Scholar]

- Yang G, Deng J, Pang G, Zhang H, Li J, Deng B, et al. An IoT-enabled stroke rehabilitation system based on smart wearable armband and machine learning. IEEE J. Transl. Eng. Health Med. 2018, 6, 2800110. DOI:10.1109/JTEHM.2018.2822681 [Google Scholar]

- Polygerinos P, Wang Z, Overvelde JT, Galloway KC, Wood RJ, Bertoldi K, et al. Modeling of soft fiber-reinforced bending actuators. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2015, 31, 778–789. DOI:10.1109/TRO.2015.2428504 [Google Scholar]

- Mehrholz J, Pohl M, Platz T, Kugler J, Elsner B. Electromechanical and robot-assisted arm training for improving activities of daily living after stroke. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 2018, CD006876. DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD006876.pub5 [Google Scholar]

- Lee SH, Park G, Cho DY, Kim HY, Lee JY, Kim S, et al. Comparisons between end-effector and exoskeleton rehabilitation robots regarding upper extremity function among chronic stroke patients. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 58630. DOI:10.1038/s41598-020-58630-2 [Google Scholar]

- Langbroek-Amersfoort AC, Veerbeek JM, van Wegen EE, Meskers CG, Kwakkel G. Effects of robot-assisted therapy for the upper limb after stroke. Neurorehabilit. Neural Repair 2017, 31, 107–121. DOI:10.1177/1545968316666957 [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura A, Peichen Z, Morita Y, Tanabe H. New “iPARKO” finger extensor facilitation training device for chronic hemiplegic hand after stroke: Development and verification of its effectiveness in healthy individuals. Robomech J. 2023, 10, 9. DOI:10.1186/s40648-023-00248-w [Google Scholar]

- Yokoyama R, Nakamura A, Morita Y, Tanabe H. Verification of immediate effect of finger extension using a finger extensor facilitation training device “iPARKO”. IEEJ Trans. Electron. Inf. Syst. 2023, 143, 1099–1105. DOI:10.1541/ieejeiss.143.1099. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, Jung MY, Kim SH. Reliability of spike and turn variables of surface EMG during isometric voluntary contractions of the biceps brachii muscle. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 2011, 21, 119–127. DOI:10.1016/j.jelekin.2010.08.008 [Google Scholar]

- Rayan G, Akelman E. The Hand: Anatomy, Examination, and Diagnosis, 4th ed.; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2012; pp. 1–160. [Google Scholar]

- Hume MC, Gellman H, McKellop H, Brumfield RH, Jr. Functional range of motion of the joints of the hand. J. Hand Surg. Am. 1990, 15, 240–243. DOI:10.1016/0363-5023(90)90102-w [Google Scholar]

- Proske U, Gandevia SC. The proprioceptive senses: Their roles in signaling body shape, body position and movement, and muscle force. Physiol. Rev. 2012, 92, 1651–1697. DOI:10.1152/physrev.00048.2011 [Google Scholar]

- Pierrot-Deseilligny E, Burke D. The Circuitry of the Human Spinal Cord: Spinal and Corticospinal Mechanisms of Movement; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2005. ISBN 978-0521543401. [Google Scholar]

- Collins DF, Cameron T, Gillard DM, Prochazka A. Muscular sense is attenuated when humans move. J. Physiol. 1998, 508 Pt 2, 635–643. DOI:10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.00635.x [Google Scholar]

- Massion J. Movement, posture and equilibrium: Interaction and coordination. Prog. Neurobiol. 1992, 38, 35–56. DOI:10.1016/0301-0082(92)90034-C [Google Scholar]

- Li S, Francisco GE. New insights into the pathophysiology of post-stroke spasticity. Front Hum Neurosci. 2015, 9, 192. DOI:10.3389/fnhum.2015.00192 [Google Scholar]