Visualization of Latent Fingermark on Metallic Surfaces Based on Displacement Reactions

Received: 22 October 2025 Revised: 10 November 2025 Accepted: 15 December 2025 Published: 19 December 2025

© 2025 The authors. This is an open access article under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

1. Introduction

Objects with non-porous surfaces are commonly encountered in everyday activities, within which a wide variety of metals and their alloys, including stainless steel, brass, and bronze, enable a broad range of applications across numerous fields. Fingermarks left on metal surfaces are important forensic evidence for the identification of victims or suspects. Given the frequent occurrence of latent fingermarks, the development of reliable visualization techniques on metal surfaces would be essential for future crime scene work. Common development techniques on non-porous substrates include powder suspension, cyanoacrylate fuming, and small particle reagents, which are extensively researched, and the visualization by these methods relies on the adherence of reagents to fingermark residues [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9]. Under circumstances when development with conventional methods is not possible, reagents that target the substrate may be considered. Due to the electrochemical behavior of metals, a reversed fingermark, with ridges remaining intact while altering the substrate, could be developed, achieving partial oxidation of the substrate and giving enhanced contrast between ridges and valleys [10]. Gun blue solution is one of the chemicals that results in reversed development on metal surfaces, especially on ballistic cartridges, both fired and unfired [10,11,12]. Thermal oxidation, as well as oxidizing agents such as ammonium sulphide, iodine fumes, and other aqueous electrolytes, can also achieve development by reacting with metal substrates [13,14,15]. The degree of fingermark development depended on the metal type; for example, a wide range of oxidizing agents was suitable for development on copper and brass, whereas fingermark development on stainless steel was difficult due to its protective oxide layer. The initial composition of a fingermark was another factor affecting development on metals, as variation in deposition components may inhibit or enhance reaction, which resulted in differential oxidation [13]. The current oxidation techniques involve high temperatures, strong acids, and bases, which are relatively hazardous and less user-friendly; therefore, it is essential to investigate methods that are safer and more accessible for forensic practitioners.

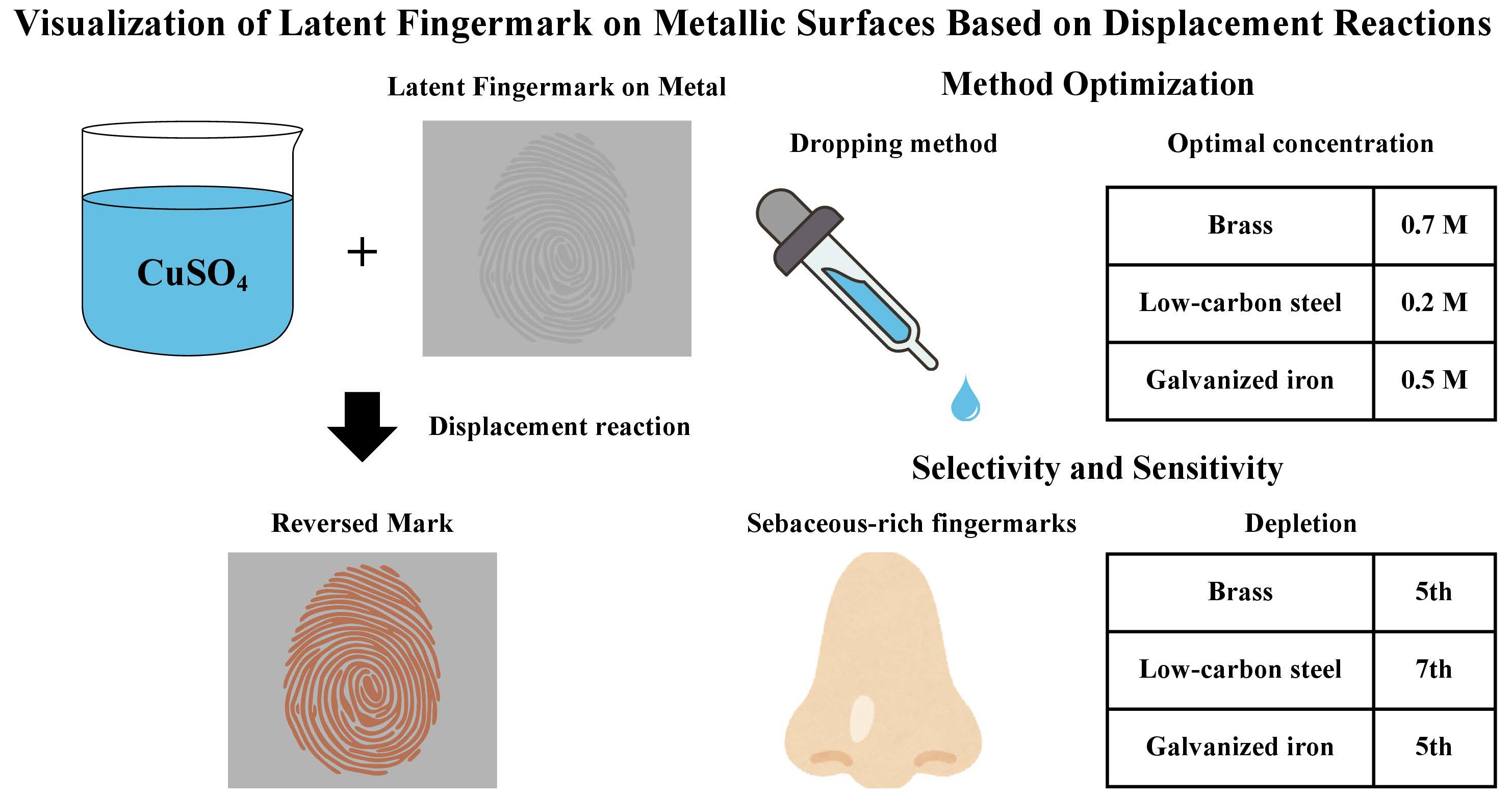

Displacement reaction is a process in which metal ions in aqueous solution are reduced to the solid state in the presence of a more electronegative metal. The metal ions deposit at the cathodic site and form a metal coating [16]. Copper (II) sulphate (CuSO4) solution is an easily accessible solution with relatively fewer hazards, which undergoes rapid displacement reactions with metals such as iron and zinc. It is hypothesized that the development of fingermarks on certain metals and alloys with CuSO4 solution would result in a reversed mark, which could be visualized for further examination. This study aimed to develop a more efficient and safe fingermark development technique on metal substrates. The development of fingermarks on metal alloys (i.e., low-carbon steel, galvanized iron, and brass) with CuSO4 solution was first optimized. Selectivity and sensitivity of the optimized development method were then investigated.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Materials

CuSO4 solution was prepared by dissolving copper sulphate pentahydrate (Unichem, Maharashtra, India) in deionized water. Metal slides measuring 70 mm × 30 mm × 1 mm, made of galvanized iron, low-carbon steel, and brass, were used as substrates, respectively. All surfaces were cleaned by wiping with methanol prior to deposition and were handled only while wearing gloves. This study has also been approved by the Research Ethics Committee (REC), Tung Wah College. Compliance with ethical standards was ensured at each step of the study.

2.2. Fingermark Deposition

Latent fingermarks were obtained from a single female donor to ensure consistency in the sampling procedure, while minimizing the variations in factors that affect the fingermark deposition, such as sweat and oil production, pressure applied, and contact time of the finger. Written informed consent was obtained from the donor prior to the initiation of the study.

Sebaceous split and quartered fingermarks were used in the method optimization study, respectively, for optimizing development conditions such as the application and concentration of CuSO4 solution. Two equal halves or four sections of the same deposited fingermark impression were compared to eliminate intra-donor variability. The donor was asked to thoroughly wash, rinse, and dry her hands to remove any greasy matter. After rubbing the finger on oily regions such as the nose, cheeks, or forehead to increase substantially the sebaceous content in the residues, the finger was placed onto two or four substrates of the same material in a way that the fingermark was divided.

To mimic real casework scenarios, natural fingermarks (i.e., fingermarks with secretions naturally found on the donor’s fingers) and eccrine fingermarks were evaluated in selectivity and sensitivity studies. For natural fingermark deposition, the donor was asked to wash her hands and then pursue her normal routine activities for 20 min so as to mimic a real-life scenario. She was asked to rub her hands together to get an even coating of natural secretions and/or contaminants across the fingers before depositing fingermarks, allowing adequate residues to collect naturally on her fingers. The fingers were then placed onto each substrate with moderate force for 3 s. For eccrine fingermark deposition, after thoroughly washing, rinsing, and drying the hands, the hands were sealed in clean nitryl gloves for 20 min to allow them to sweat. After which, the donor was asked to place the fingers onto each substrate with moderate force for 3 s.

Reduced residue transfer due to repeated touch was simulated by a fingermark depletion series. Sebaceous split fingermarks in a depletion series were deposited to assess the sensitivity of the method. The donor was asked to thoroughly wash, rinse, and dry her hands and rub the finger on the greasy regions to ensure sufficient sebaceous content. The finger was alternately pressed on two substrates of the same type for odd-number marks (1, 3, 5, and 7) and another substrate for even-number marks (2, 4, and 6) without re-rubbing. Substrates carrying split fingermarks in odd-number depletion were used in the experiment.

A total of 258 fingermarks were developed and evaluated to investigate a rapid fingermark development method based on displacement reactions between copper (II) sulphate and various types of metal substrates. Figure 1 demonstrates sebaceous fingermarks on the three types of metals before development.

|

|

|

| (a) | (b) | (c) |

Figure 1. Sebaceous fingermarks on (a) galvanized iron, (b) brass, and (c) low-carbon steel before development.

2.3. Method Optimization

To optimize reagent application, the dropping and immersion methods were compared on split fingermarks. For the dropping method, CuSO4 solution with a concentration of 0.2 M was applied to one half of the mark with a disposable dropper until the solution covered the entire fingermark. For the immersion method, the metal bearing another half of the same mark was entirely immersed in the solution for development. All metal slides were rinsed with deionized water immediately after removal of CuSO4 solution to inhibit further reaction. The split mark was combined and recorded photographically for comparison.

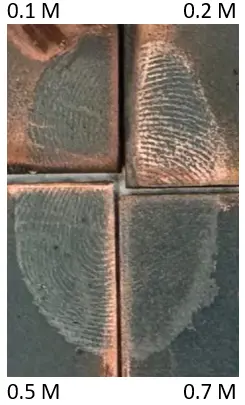

The optimal concentration was determined from 0.1 M, 0.2 M, 0.5 M, and 0.7 M CuSO4 solutions for each type of metal. Each fraction of the quartered fingermarks was immersed in one of the concentrations, respectively. Developed fingermarks were combined and photographed to determine the concentration that achieved the best visualization on each type of metal.

2.4. Selectivity

Eccrine, natural, and sebaceous fingermarks on each metal type were developed with the optimized displacement method and fluorescent powder, respectively. The fingermarks were photographed and graded according to the modified CAST (Centre for Applied Science & Technology) grading scale (Table 1) recommended by the International Fingerprint Research Group (IFRG) [17].

Table 1. A modified CAST fingermark grading scale.

|

Grade |

Detail Visualized |

|---|---|

|

0 |

No development |

|

1 |

Signs of contact but <1/3 of mark with continuous ridges |

|

2 |

1/3–2/3 of mark with continuous ridges |

|

3 |

>2/3 of mark with continuous ridges, but not quite a perfect mark |

|

4 |

Full development—whole mark clear with continuous ridges |

2.5. Sensitivity

Sebaceous split fingermarks were deposited in a depletion series within which consecutive odd-number marks (1, 3, 5, and 7) were deposited without re-rubbing. One-half of the depletion was developed with the optimized method, and the other half of the same mark was developed with fluorescent powder. The fingermarks were combined for photo-recording and were graded with the modified CAST grading scale (Table 1) and compared according to the UC (University of Canberra) comparative scale (Table 2), also recommended by the IFRG [17].

Table 2. A UC comparative scale, method A represents the displacement method, and method B represents the fluorescent powder.

|

Grade |

Definition |

|---|---|

|

+2 |

Half-mark developed by method A exhibits far greater ridge detail and/or contrast than method B |

|

+1 |

Half-mark developed by method A exhibits slightly greater ridge detail and/or contrast than method B |

|

0 |

No significant difference between half-impressions |

|

−1 |

Half-mark developed by method B exhibits slightly greater ridge detail and/or contrast than method A |

|

−2 |

Half-mark developed by method B exhibits far greater ridge detail and/or contrast than method A |

3. Results

3.1. Method Optimization

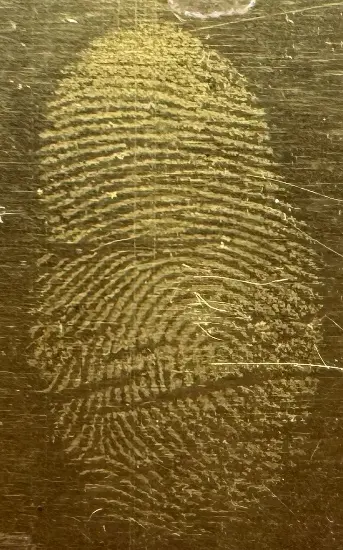

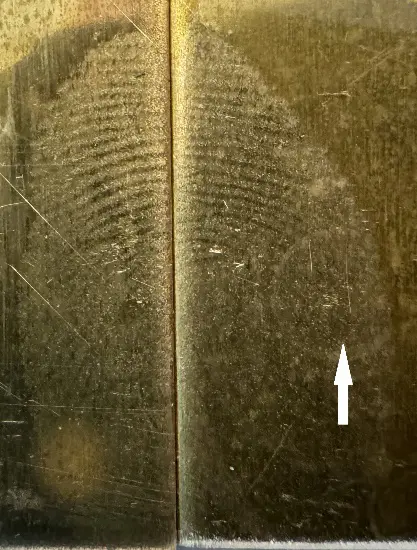

Our experimental results showed that immersion was a more suitable application method than dropping. The immersion method resulted in a more uniform development across the fingermarks, while application with a dropper (i.e., the dropping method) sometimes led to partial development. As observed in Figure 2a, the immersed mark achieved relatively full development, whereas partial and discontinuous ridges were observed on the marks developed by dropping. The use of a dropper left droplet marks on the fingermarks, which obscured part of the ridge details, as pointed out in Figure 2b. Due to the mobility of the solution, some fingermarks developed by dropping were not entirely covered in the solution, leading to incomplete development. Moreover, applying the solution with a dropper resulted in inconsistencies in the fingermark-solution interaction. Differential development of fingermarks was attributable to the area exposed to the first drop developing faster than subsequently exposed regions. Metals with immediate displacement reaction after exposure, e.g., galvanized iron, were affected the most, resulting in more uneven development of the mark. As immersion achieved more uniform development and was less prone to operational error and bias, it was determined as the optimal application technique.

|

|

| (a) | (b) |

Figure 2. (a) Split sebaceous fingermark deposited on galvanized iron developed by immersion (left) and dropping (right); (b) Split sebaceous fingermark deposited on brass developed by immersion (left) and dropping (right). A droplet mark was observed (white arrow).

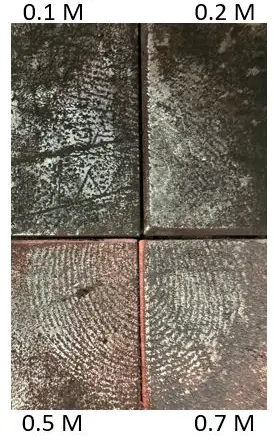

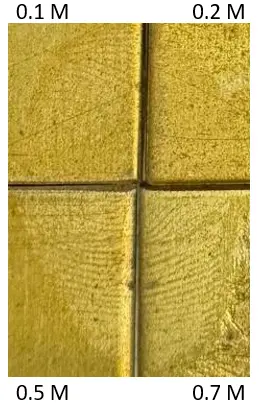

The optimum concentrations for three types of metals were determined separately. For galvanized iron, development of fingermarks was observed in all concentrations, within which 0.5 M resulted in the clearest ridge details and the most uniform development (Figure 3a) on the majority of fingermarks. On brass, fingermark development was scarce in 0.1 M and 0.2 M, while the development for 0.5 M and 0.7 M was similar, with 0.7 M providing slightly better contrast (Figure 3b). As for low-carbon steel, no development was observed for 0.1 M, 0.5 M, and 0.7 M, while coppery deposits were observed on the valleys of the fingermarks developed with 0.2 M CuSO4 solution (Figure 3c). Therefore, the optimum concentrations of CuSO4 solution for galvanized iron, brass, and low-carbon steel were 0.5 M, 0.7 M, and 0.2 M, respectively.

|

|

|

| (a) | (b) | (c) |

Figure 3. Quartered sebaceous fingermark on (a) galvanized iron, (b) brass, and (c) low-carbon steel developed with different concentrations of CuSO4 solutions.

3.2. Selecivity

The grades of fingermarks developed by CuSO4 solution and fluorescent powder are shown in Table 3 and Table 4, respectively. Comparing the three types of fingermarks shown in Table 3, CuSO4 solution was the most effective in developing sebaceous marks on all tested metals. Natural and eccrine marks were not developed, with the exception of two eccrine marks on galvanized iron that showed slight enhancement. Among the three metals, the best fingermark development in CuSO4 solution was observed on brass, on which sebum-rich marks showed development of more than two-thirds of continuous ridges, and two marks achieved full development (Figure 4). All sebaceous marks on low-carbon steel showed more than one-third, and some more than two-thirds, of continuous ridges after enhancement with CuSO4 solution. Fingermarks on galvanized iron resulted in relatively poor development, with one-third of the marks achieving grade 1 after CuSO4 enhancement, while other marks were graded 2 and 3. In contrast, all sebaceous marks were developed with fluorescent powder, their grades ranged from grade 1 to 3. The development of natural marks on low-carbon steel and eccrine marks on brass and galvanized iron was achieved by the powder method. The enhancement of the remaining marks was unsuccessful. To conclude, the quality of sebaceous marks developed with CuSO4 solution was better than that developed with fluorescent powder for low-carbon steel and brass; however, fluorescent powder was more reliable for visualizing natural and eccrine fingermarks.

Table 3. Fingermarks developed with CuSO4 displacement.

|

Metal Type |

Fingermark Type |

Number of Developed Fingermarks |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Grade 0 |

Grade 1 |

Grade 2 |

Grade 3 |

Grade 4 |

||

|

Galvanized iron |

Sebaceous |

0 |

3 |

2 |

4 |

0 |

|

Natural |

9 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

|

Eccrine |

7 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

|

Low-carbon steel |

Sebaceous |

0 |

0 |

4 |

4 |

1 |

|

Natural |

9 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

|

Eccrine |

9 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

|

Brass |

Sebaceous |

0 |

0 |

1 |

6 |

2 |

|

Natural |

9 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

|

Eccrine |

9 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Table 4. Fingermarks developed with fluorescent powder.

|

Metal Type |

Fingermark Type |

Number of Developed Fingermarks |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Grade 0 |

Grade 1 |

Grade 2 |

Grade 3 |

Grade 4 |

||

|

Galvanized iron |

Sebaceous |

0 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

0 |

|

Natural |

9 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

|

Eccrine |

4 |

4 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

|

|

Low-carbons steel |

Sebaceous |

0 |

3 |

6 |

0 |

0 |

|

Natural |

3 |

6 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

|

Eccrine |

9 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

|

Brass |

Sebaceous |

0 |

0 |

4 |

5 |

0 |

|

Natural |

9 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

|

Eccrine |

6 |

3 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

3.3. Sensitivity

The quality of fingermarks developed with CuSO4 solution generally decreased with increasing depletion (Table 5). Fingermarks on galvanized iron and brass were identifiable until the 5th depletion, while only signs of contact were observed on the 7th depletion. The fingermark quality on low-carbon steel initially increased, peaked at the 3rd depletion, and subsequently decreased at the 5th and 7th mark. Identifiable marks with more than one-third continuous ridges were still visible at the 7th depletion. When comparing CuSO4 solution and fluorescent powder development, the powder method outperformed CuSO4 solution on galvanized iron and brass, while similar performance was observed on low-carbon steel (Table 6).

Table 5. Fingermark grades for half-marks developed with CuSO4.

|

Metal Type |

Trial |

Depletion |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1 |

3 |

5 |

7 |

||

|

Galvanized iron |

1 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

|

2 |

2 |

3 |

2 |

1 |

|

|

3 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

|

Low-carbons steel |

1 |

2 |

3 |

2 |

2 |

|

2 |

2 |

3 |

2 |

1 |

|

|

3 |

2 |

3 |

2 |

2 |

|

|

Brass |

1 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

1 |

|

2 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

|

|

3 |

4 |

3 |

1 |

2 |

|

Table 6. Comparison between development by CuSO4 solution and fluorescent powder using UC comparative scale.

|

Metal Type |

Trial |

Depletion |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1 |

3 |

5 |

7 |

||

|

Galvanized iron |

1 |

+1 |

+2 |

−1 |

−2 |

|

2 |

−2 |

0 |

+1 |

−2 |

|

|

3 |

0 |

−2 |

−2 |

−1 |

|

|

Low-carbons steel |

1 |

−1 |

+1 |

0 |

0 |

|

2 |

−1 |

+1 |

0 |

−1 |

|

|

3 |

0 |

+1 |

0 |

−1 |

|

|

Brass |

1 |

−2 |

−2 |

+1 |

−1 |

|

2 |

−2 |

−2 |

−2 |

−2 |

|

|

3 |

0 |

−1 |

−2 |

−2 |

|

Note. + indicates CuSO4 solution performed better than fluorescent powder, − indicates the reverse.

4. Discussion

The development of fingermarks was based on a displacement reaction, an electrochemical process between CuSO4 solution and the metal substrates. The copper (II) ions (Cu2+) would be reduced and deposited on the metal substrates and form a layer of coating, whereas the metal substrates would be oxidized and dissolved in the solution [18]. The prerequisite of this reaction is that the metal substrates must be more reactive than the metal ions in the solution [16]. Galvanized iron, brass, and low-carbon steel are zinc-coated iron, copper-zinc alloy, and iron-carbon alloy, respectively. Zinc and iron are more electronegative than copper; therefore, displacement reaction on the metal substrates is expected, and the equations are listed below.

|

```latex\mathrm{Zn + Cu^{2+}\rightarrow Cu + Zn^{2+}}``` |

|

| ```latex\mathrm{Fe + Cu^{2+}\rightarrow Cu + Fe^{2+}}``` |

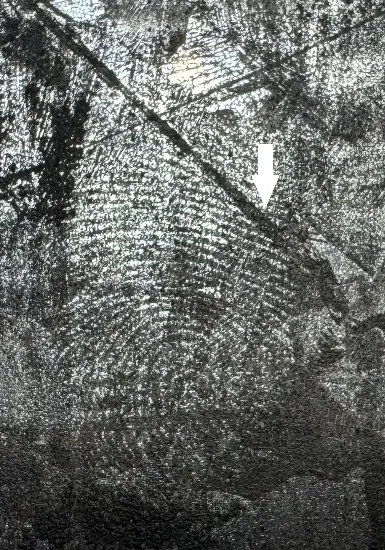

The hypothesized principle of this method was that fingermark residues inhibited copper deposition, which allowed the reaction to occur only on the bare metal substrate, creating a reversed image. Development on all three metal substrates agreed with this hypothesis, with color changes observed only at the valleys of the fingermarks. The metal deposits on galvanized iron were brownish black, which provided good contrast with the silver ridges. However, the development was not permanent, and the deposits could be wiped off after enhancement. In view of this, the developed marks should be handled carefully to prevent smearing of ridge details. Ridges on low-carbon steel remained dark grey, with coppery deposits observed on the valleys. The development was permanent and could not be removed by wiping (Figure 5). The ridges on brass retained the light golden color, while the uncovered part darkened and tarnished permanently. A similar phenomenon, showing reversed enhancement, was also observed in fingermarks deposited on metal substrates developed with oxidation and aqueous electrolytes [13,14].

Figure 5. Sebaceous fingermark deposited on low-carbon steel developed with CuSO4 solution showing grey ridges and coppery valleys.

The selectivity results indicated that sebum provided greater protection to the metal substrate, whereas eccrine and natural fingermark residue were unable to inhibit the displacement reaction. Sebum mainly consists of fatty acids, squalene, wax esters, and triglycerides, which are water-insoluble [19]. The presence of these materials in the fingermark residues prevented the CuSO4 solution from reaching the metal, resulting in a color contrast between the ridges and the substrates. Besides the displacement reaction, inhibition of metal oxidation by the sebaceous contents in fingermarks, due to their hydrophobic effect, was also reported [13]. As this development method relies on the sebaceous component in fingermarks, decreasing fingermark quality down the depletion series could be attributed to the reduction of sebaceous content with sequential deposition [20]. The depletion of sebum in fingermarks reduced the inhibition of metal substrate from the CuSO4 solution, resulting in increasingly unclear ridges in each successive mark.

When comparing the displacement and fluorescent powdering methods, the quality of marks treated with the former was generally greater than that with the latter in the selectivity experiment, while the inverse was observed in the sensitivity experiment. This inconsistency could be attributed to the use of split fingermarks in the sensitivity test, which were deposited across the edge of the metal substrates. As observed in the experiments, displacement reaction on the metal slides began from the edge and gradually proceeded to the center of the metal slides, which resulted in differential enhancement. Split fingermarks deposited on the edge of the metal slides experienced a higher degree of development, resulting in lower quality when compared to the powdering method.

A limitation of this method was that the quality of the developed marks depended on the metal surface; the presence of scratches or the removal of coatings might lead to different rates of development, obscuring certain ridge details as observed in Figure 6. In view of the inconsistent rate of fingermark development, a more controlled reagent should be developed with reference to results from the current and other metal substrates studies [13,14,15,20]. Moreover, this method requires immersing the entire object in the solution, which might destroy other trace evidence on the evidence item, so the sequence of its application should be considered carefully to prevent loss of essential information. To tackle this, future studies could investigate targeted area development using aqueous CuSO4 in gel form, which enabled the development of fingermarks in designated areas, with minor impact on surrounding surfaces and facilitated fingermark development on immovable or vertical objects [21].

5. Conclusions

An optimum condition for developing latent fingermarks by the displacement reaction of CuSO4 solution on metal substrates was investigated in this study. Immersion was a more effective application method, and the optimal concentrations were 0.2 M, 0.5 M, and 0.7 M for low-carbon steel, galvanized iron, and brass, respectively. Fingermark residues, sebaceous components in particular, protected the metal from displacement reaction, leaving a reversed impression on the metal slides; no development was visualized for eccrine and natural fingermarks. Within a depletion series, identifiable marks were developed until the 5th depletion for brass and galvanized iron and until the 7th depletion for low-carbon steel. Comparison with conventional fluorescent powdering revealed a slight disadvantage of CuSO4 solution due to the differential development rate. As immersion of the entire metal slide was required, other trace evidence may be obscured, therefore, its application to evidence items should be carefully considered in real crime cases. Improvements could be considered in two directions, which are to develop a reagent with a more controlled deposition rate and to change the solution into gel form for remote area development. To ensure the robustness of this method, a systematic validation should be conducted before implementing its application to real crime evidence.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and methodology, D.S.-y.M. and K.-w.F.L.; Data acquisition and analysis, K.-w.F.L. and P.-w.M.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, K.-w.F.L.; Writing—Review & Editing and supervision, D.S.-y.M. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The research data is available on reasonable request.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Pitera M, Sears VG, Bleay SM, Park S. Fingermark visualization on metal surfaces: An initial investigation of the influence of surface condition on process effectiveness. Sci. Justice 2018, 58, 372–383. doi:10.1016/j.scijus.2018.05.005. [Google Scholar]

- Barros RM, Oliveira Neto OS, Barbosa RRM, Tonietto A, Jacintho CVM, Del Sarto RP, et al. Using a large-scale cyanoacrylate fuming chamber for latent fingermark detection in vehicles. Aust. J. Forensic Sci. 2022, 55, 645–655. doi:10.1080/00450618.2022.2057590. [Google Scholar]

- Bleay SM, Kelly PF, King RS, Thorngate SG. A comparative evaluation of the disulfur dinitride process for the visualization of fingermarks on metal surfaces. Sci. Justice 2019, 59, 606–621. doi:10.1016/j.scijus.2019.06.011. [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Zhang Z, Zhang L, Zhai Y. The effectiveness of strong afterglow phosphor powder in the detection of fingermarks. Forensic Sci. Int. 2009, 183, 45–49. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2008.10.008. [Google Scholar]

- Masterson A, Bleay S. The effect of corrosive substances on fingermark recovery: A pilot study. Sci. Justice 2021, 61, 617–626. doi:10.1016/j.scijus.2021.07.004. [Google Scholar]

- Girelli CM, Lobo BJ, Cunha AG, Freitas JC, Emmerich FG. Comparison of practical techniques to develop latent fingermarks on fired and unfired cartridge cases. Forensic Sci. Int. 2015, 250, 17–26. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2015.02.012. [Google Scholar]

- Kaur K, Sharma T, Kaur R. Development of submerged latent fingerprints on non-porous substrates with activated charcoal based small particle reagent. Indian J. Forensic Med. Toxicol. 2020, 14, 388–394. [Google Scholar]

- Trapecar M. Finger marks on glass and metal surfaces recovered from stagnant water. Egypt. J. Forensic Sci. 2012, 2, 48–53. doi:10.1016/j.ejfs.2012.04.002. [Google Scholar]

- Rohatgi R, Sodhi G, Kapoor A. Small particle reagent based on crystal violet dye for developing latent fingerprints on non-porous wet surfaces. Egypt. J. Forensic Sci. 2015, 5, 162–165. doi:10.1016/j.ejfs.2014.08.005. [Google Scholar]

- Migron Y, Hocherman G, Springer E, Almog J, Mandler D. Visualization of sebaceous fingerprints on fired cartridge cases: A laboratory study. J. Forensic Sci. 1998, 43, 543–548. doi:10.1520/JFS16180J. [Google Scholar]

- Christofidis G, Morrissey J, Birkett JW. Using gun blue to enhance fingermark ridge detail on ballistic brass. J. Forensic Identif. 2019, 69, 431. [Google Scholar]

- Morrissey J, Larrosa J, Birkett JW. A preliminary evaluation of the use of gun bluing to enhance friction ridge detail on cartridge casings. J. Forensic Identif. 2017, 67, 313–322. [Google Scholar]

- Wightman G, Emery F, Austin C, Andersson I, Harcus L, Arju G, et al. The interaction of fingermark deposits on metal surfaces and potential ways for visualization. Forensic Sci. Int. 2015, 249, 241–254. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2015.01.035. [Google Scholar]

- Jasuja OP, Singh G, Almog J. Development of latent fingermarks by aqueous electrolytes. Forensic Sci. Int. 2011, 207, 215–222. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2010.10.011. [Google Scholar]

- Wightman G, O’connor D. The thermal visualization of latent fingermarks on metallic surfaces. Forensic Sci. Int. 2011, 204, 88–96. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2010.05.007. [Google Scholar]

- Power GP, Ritchie IM. A contribution to the theory of cementation (metal displacement) reactions. Aust. J. Chem. 1976, 29, 699–709. doi:10.1071/CH9760699. [Google Scholar]

- Almog J, Cantu AA, Champod C, Kent T, Lennard C. Guidelines for the assessment of fingermark detection techniques, International Fingerprint Research Group (IFRG). J. Forensic Identif. 2014, 64, 174–200. [Google Scholar]

- Ling BYY, Lee YH, Mohammad S, Tan CS. Corrosion of galvanized and ungalvanized cold-formed steel in chloride and sulphate solutions. ASEAN Eng. J. 2023, 13, 145–161. doi:10.11113/aej.v13.18564. [Google Scholar]

- Girod A, Ramotowski R, Weyermann C. Composition of fingermark residue: a qualitative and quantitative review. Forensic Sci. Int. 2012, 223, 10–24. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2012.05.018. [Google Scholar]

- Chadwick S, Moret S, Jayashanka N, Lennard C, Spindler X, Roux C. Investigation of some of the factors influencing fingermark detection. Forensic Sci. Int. 2018, 289, 381–389. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2018.06.014. [Google Scholar]

- Jasuja OP, Singh K. Visualizing latent fingermarks by aqueous electrolyte gel on fixed aluminum and steel surfaces. Can. Soc. Forensic Sci. J. 2017, 50, 181–196. doi:10.1080/00085030.2017.1371435. [Google Scholar]