Public Participation in Ecological Civilization Construction in Urumqi: A Case Study of a Rapidly Expanding Arid Metropolis in Northwestern China

Received: 20 September 2025 Revised: 20 October 2025 Accepted: 02 December 2025 Published: 08 December 2025

© 2025 The authors. This is an open access article under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

1. Introduction

Ecological civilization represents a new stage in human societal development [1,2]. To address increasingly severe environmental challenges, the Chinese government upgraded its national policy framework from environmental protection to ecological civilization [3,4]. In 2018, ecological civilization was incorporated into China’s Constitution as a guiding principle for ecological legislation, regulation, and environmental education [4,5,6]. This development has had profound implications for society, citizens, and international policies in China [7]. Ecological civilization is a moral and ideological framework that embodies the principles of harmonious coexistence and sustainable development across the dimensions of human-to-human, human-to-nature, and human-to-society relationships [8]. It is currently regarded as a major Chinese state-initiated vision for the global environmental future [7]. China’s concept of ecological civilization provides a distinctive pathway for implementing the United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development [9]. Ecological civilization construction refers to the measures and actions that translate this concept into practice [10]. Incorporating public participation into ecological civilization construction is crucial for advancing environmental governance [11,12,13].

The literature on citizen science in environmental governance has expanded rapidly. Previous studies have demonstrated that public participation in environmental governance is valuable for collecting environmental data [14,15], helping people understand and focus on environmental issues [16], increasing scientific knowledge [17], enhancing ecological awareness [18,19], and optimizing environmental policies [20]. However, empirical research on public participation in ecological civilization construction remains limited. One study investigated the behavior and cognition of ecological civilization among Chinese university students, noting that the success or failure of ecological civilization construction in China largely depends on whether citizens effectively engage in such behaviors [13]. The institutionalization of ecological civilization construction is a process of embedding this concept into people’s values and actions [21]. Based on the “attitude-behavior” theory, citizens’ behaviors are closely linked to their cognition, awareness, and attention [22,23]. Furthermore, public satisfaction indices were incorporated into the “Assessment Target System of Ecological Civilization Construction” in 2016. Therefore, assessing the public’s subjective perceptions and satisfaction with ecological civilization construction remains an urgent issue.

Urumqi is a key city in the implementation of the Belt and Road Initiative, acting as a hub connecting mainland China with Central and Western Asia and Europe [24,25]. Located in China’s arid northwest, far from the oceans, Urumqi has low precipitation and high evaporation rates [26]. Water scarcity and the vulnerability of its environment have hindered the city’s sustainable urban development [27,28]. To promote ecological civilization construction, the local government has adopted multiple policies and programs, including “barren mountain greening”, the “blue sky project”, “coal-to-gas conversion”, and “ecological landscaping construction” (Xinjiang Environmental Protection Bureau, 2019). Currently, few studies have investigated public participation in ecological civilization construction in northwestern China. Therefore, it is critical to identify the factors that influence residents’ participation in ecological civilization construction in this region to encourage public engagement and advance the goal of building a “Beautiful China”.

In this study, we investigated residents’ participation in the construction of ecological civilization in Urumqi, China. The objectives of this research were: (1) to evaluate citizens’ perceptions, satisfaction levels, and participation in ecological civilization construction; (2) to identify the factors that influence public participation in ecological civilization construction; and (3) to propose measures for promoting public participation in ecological civilization construction.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

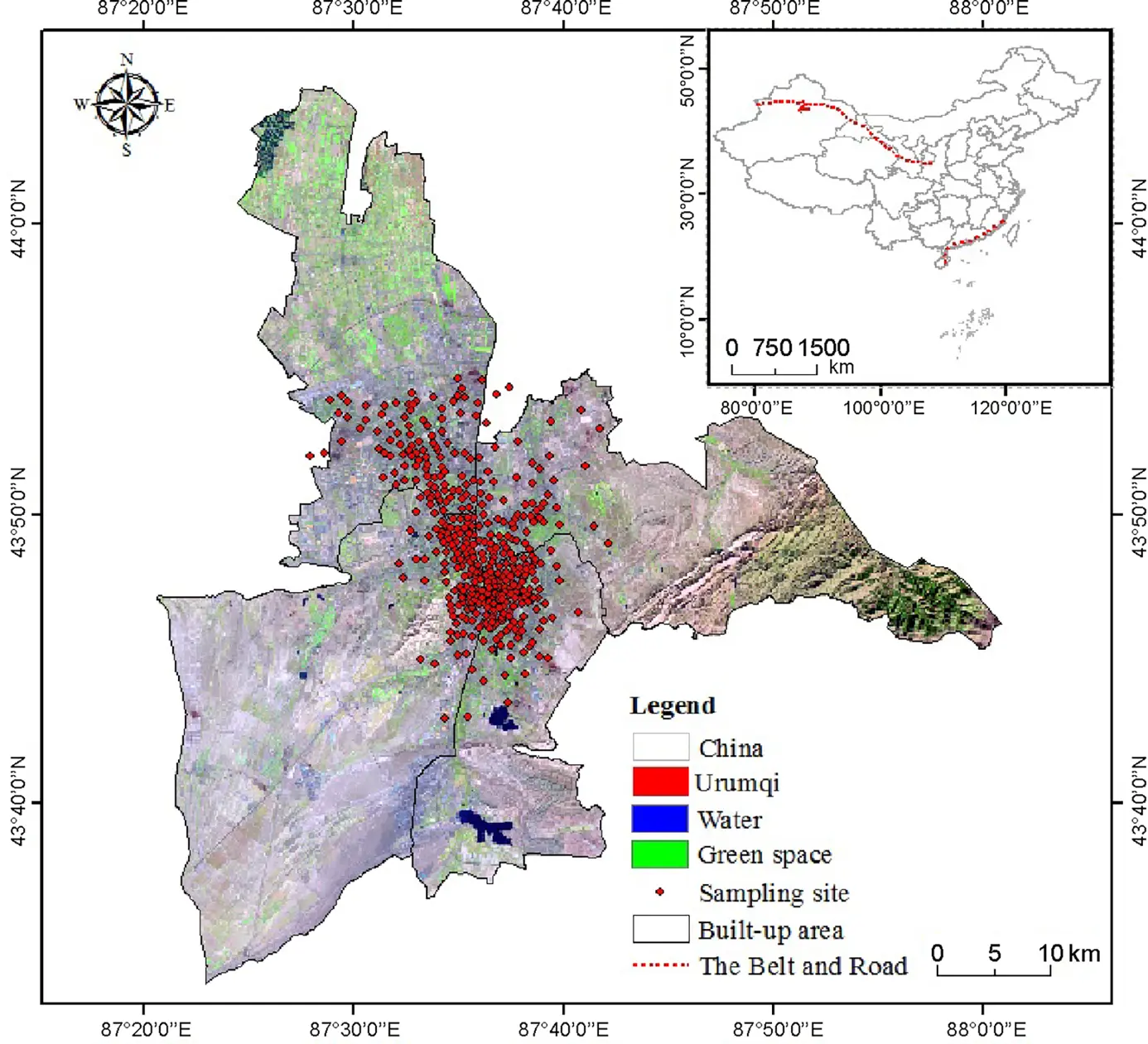

This study focused on Urumqi, the central city of the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region in northwestern China (Figure 1). Of all cities worldwide, Urumqi is the farthest from the oceans, resulting in low precipitation and large annual temperature variations [27]. The city comprises seven districts and one county, covering a total area of 1.42 × 104 km2 [28]. Four districts—Saybagh, Shuimogou, Tianshan, and the High-Tech District—are in the urban center. The permanent population is 4.09 million [28]. Urumqi is currently undergoing modernization, internationalization, and ecological development [27]. Therefore, it is crucial to advance ecological civilization construction and to harmonize cultural development with environmental protection to support the sustainable development of the Green Silk Road.

2.2. Questionnaire Administration and Sample

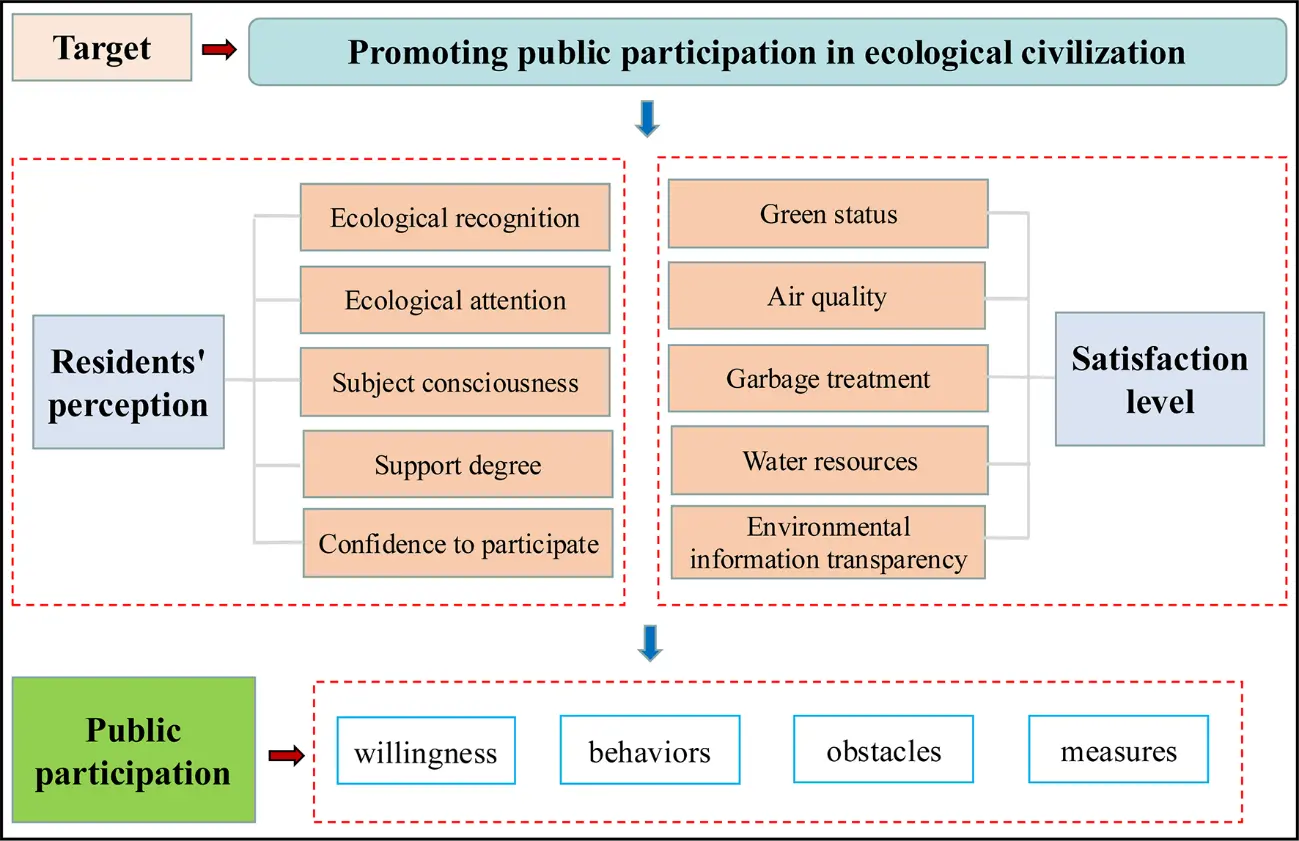

The questionnaire comprised four sections: (i) an introduction to the concept and significance of ecological civilization; (ii) respondents’ perceptions and satisfaction with ecological civilization construction; (iii) public participation in ecological civilization construction; and (iv) respondents’ socio-demographic characteristics. The theoretical model of public participation in ecological civilization construction and the questionnaire framework are presented in Figure 2. The questionnaire was developed based on a comprehensive literature review, field surveys, ten focus group discussions, and the researchers’ professional experience.

Figure 2. Theoretical model of public participation in ecological civilization construction and the questionnaire framework.

To evaluate the effectiveness of the questionnaire, a preliminary field survey was conducted in Urumqi, involving 129 residents through direct interaction. Based on feedback from this field survey, we revised the content of the questionnaire. Afterwards, the finalized electronic version was officially distributed via the online platform (www.sojump.com, accessed on 30 August 2017). A total of 1040 responses were collected, from which 1012 valid responses were identified as originating from Urumqi, based on the respondents’ IP addresses. All participants were informed of the study’s purpose and assured of anonymity and confidentiality. The Cronbach’s α was 0.71, indicating good reliability of the questionnaire. Furthermore, the KMO value was 0.84, and Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant (χ = 4989.69, p < 0.001), demonstrating good validity of the questionnaire.

The sample included residents with different genders, ages, incomes, educational levels, occupations, and academic backgrounds. The proportions of male and female respondents were 46.15% and 53.85%, respectively. Respondents aged 20–30 years accounted for 67% of the total sample. Those with monthly incomes of ¥3001–5000 and below ¥2000 accounted for 29.64% and 37.55% of the total sample, respectively. Most respondents had a bachelor’s degree or higher, with those holding a bachelor’s degree representing the largest group (38.54%). Civil servants accounted for 17% of the sample, while enterprise employees accounted for 19.07%. Students constituted the largest group, at 28.95%. These characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. The main socio-demographic characteristics of respondents.

|

Variables |

Category |

Number of Respondents |

Proportion (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Gender |

Male = 1 |

467 |

46.15 |

|

Female = 2 |

545 |

53.85 |

|

|

Age |

<20 = 1 |

43 |

4.25 |

|

20–30 = 2 |

678 |

67.00 |

|

|

31–40 = 3 |

162 |

16.01 |

|

|

41–50 = 4 |

106 |

10.47 |

|

|

>50 = 5 |

23 |

2.27 |

|

|

Average monthly income (¥) |

<2000 = 1 |

380 |

37.55 |

|

2000–3000 = 2 |

193 |

19.07 |

|

|

3001–5000 = 3 |

300 |

29.64 |

|

|

5001–10,000 = 4 |

117 |

11.56 |

|

|

Over 10,000 = 5 |

22 |

2.17 |

|

|

Education |

Primary school and below = 1 |

39 |

3.85 |

|

Junior middle school = 2 |

90 |

8.89 |

|

|

High school = 3 |

89 |

8.79 |

|

|

Specialty = 4 |

143 |

14.13 |

|

|

Bachelor = 5 |

390 |

38.54 |

|

|

Master = 6 |

222 |

21.94 |

|

|

PhD = 7 |

39 |

3.85 |

|

|

Occupation |

Civil servant = 1 |

172 |

17.00 |

|

Enterprise staff = 2 |

193 |

19.07 |

|

|

Technical personnel = 3 |

45 |

4.45 |

|

|

Teacher = 4 |

60 |

5.93 |

|

|

Student = 5 |

293 |

28.95 |

|

|

Businesses = 6 |

43 |

4.25 |

|

|

Freelance = 7 |

119 |

11.76 |

|

|

Retired personnel = 8 |

7 |

0.69 |

|

|

Others = 9 |

80 |

7.91 |

|

|

Academic background |

Majors related to environmental science = 1 |

352 |

34.78 |

|

Others = 2 |

660 |

65.22 |

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Frequency analysis, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), independent samples t-test, and Pearson’s correlation analysis were conducted to examine differences and relationships among the variables. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 25.

2.4. Variables

(I) Socio-demographic variables

Residents’ socio-demographic characteristics (gender, age, income, education level, occupation, and academic background) were coded as dummy variables for analysis.

(II) Residents’ perception of ecological civilization

Residents’ perception of ecological civilization was classified into five dimensions: ecological cognition, ecological attention, subject consciousness, degree of support, and confidence to participate [13,29,30,31]. Responses were measured using a four- or five-point Likert scale (Table 2). Scores ranged from 1 to 4 or from 1 to 5, depending on the dimension, with higher scores indicating a more positive perception of ecological civilization.

(III) Satisfaction with ecological civilization construction

Satisfaction was assessed across five aspects of ecological civilization construction: green status, air quality, waste management, water resources, and environmental information transparency [32,33]. Scores were assigned according to Likert scales, with higher values indicating greater satisfaction and reflecting a more positive public evaluation of ecological civilization construction.

(IV) Public participation in ecological civilization construction

Public participation was assessed based on residents’ willingness to participate, participation behaviors, obstacles, and proposed measures for ecological civilization construction [13,23,30,31,34].

Table 2. Public participation in ecological civilization construction.

|

Variables |

Interview Questions |

Options Score |

Proportion (%) |

Mean |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Ecological cognition |

Are you familiar with the concept of ecological civilization in China? |

4 |

18.77 |

2.75 |

|

3 |

43.08 |

|||

|

2 |

33.00 |

|||

|

1 |

5.14 |

|||

|

Ecological attention |

Do you pay attention to the phenomenon of ecological destruction around you? |

4 |

17.29 |

2.95 |

|

3 |

64.33 |

|||

|

2 |

14.33 |

|||

|

1 |

4.05 |

|||

|

Subjective consciousness |

Do you think public participation is important for the construction of ecological civilization? |

5 |

72.92 |

4.66 |

|

4 |

22.83 |

|||

|

3 |

2.87 |

|||

|

2 |

0.49 |

|||

|

1 |

0.89 |

|||

|

Support degree |

Do you support your city in creating an ecological civilization city? |

4 |

72.04 |

3.67 |

|

3 |

25.00 |

|||

|

2 |

1.28 |

|||

|

1 |

1.68 |

|||

|

Confidence to participate |

Do you have confidence in the development of ecological civilization construction in your city over the next five years? |

4 |

25.00 |

2.97 |

|

3 |

55.14 |

|||

|

2 |

12.06 |

|||

|

1 |

7.81 |

|||

|

Willingness to participate |

Would you like to participate in environmental protection activities? |

4 |

45.55 |

3.67 |

|

3 |

41.60 |

|||

|

2 |

6.72 |

|||

|

1 |

6.13 |

|||

|

Green status |

How satisfied are you with the greening situation in your city? |

4 |

14.92 |

2.51 |

|

3 |

31.42 |

|||

|

2 |

43.58 |

|||

|

1 |

10.08 |

|||

|

Air quality |

How satisfied are you with the air quality in your city? |

4 |

14.33 |

2.35 |

|

3 |

24.11 |

|||

|

2 |

44.27 |

|||

|

1 |

17.29 |

|||

|

Waste management |

How satisfied are you with the waste management in your city? |

4 |

9.78 |

1.99 |

|

3 |

13.64 |

|||

|

2 |

42.49 |

|||

|

1 |

34.09 |

|||

|

Water resources |

How satisfied are you with the water resources in your city? |

5 |

8.99 |

1.81 |

|

4 |

17.39 |

|||

|

3 |

38.74 |

|||

|

2 |

15.51 |

|||

|

1 |

19.37 |

|||

|

Environmental information transparency |

How satisfied are you with the environmental information disclosure by the local government? |

4 |

9.98 |

2.41 |

|

3 |

42.79 |

|||

|

2 |

25.30 |

|||

|

1 |

21.94 |

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Residents’ Perception, Satisfaction, and Willingness to Participate in Ecological Civilization Construction

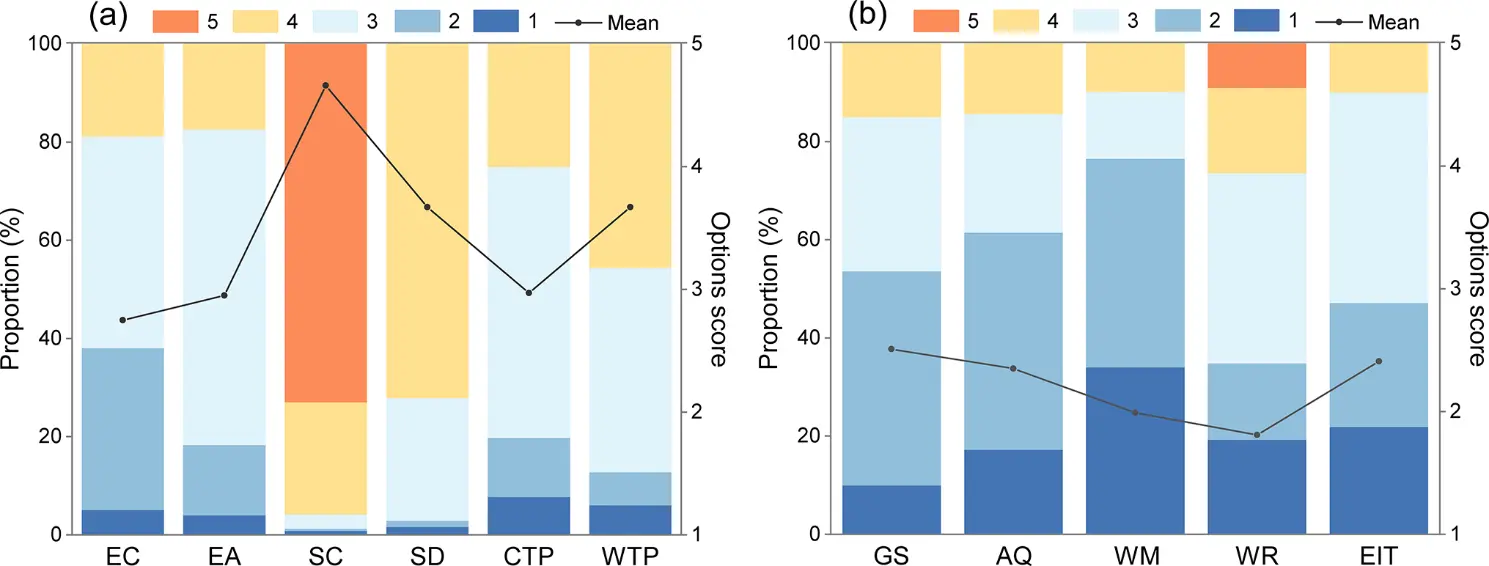

Numerous studies have shown that environmental awareness influences individuals’ willingness and behaviors related to environmental protection [29,34]. The distribution of responses on residents’ perceptions and willingness to participate in ecological civilization construction is presented in Figure 3a. Subject consciousness received the highest mean score (4.66), indicating strong recognition of the importance of public participation. By contrast, ecological cognition (2.75) and confidence to participate (2.97) were relatively low, revealing gaps in awareness and confidence. These findings suggest that residents’ understanding of ecological civilization construction requires further improvement. Both degrees of support (3.67) and willingness to participate (3.67) were relatively high, reflecting positive public attitudes toward the construction of ecological civilization.

Residents’ satisfaction is an important component of subjective well-being evaluation [32], as it enables citizens to observe and understand the status of ecological civilization construction. Figure 3b presents residents’ satisfaction levels regarding ecological civilization construction. The average satisfaction scores for different indicators were as follows: green status (2.51) > environmental information transparency (2.41) > air quality (2.35) > waste management and treatment (1.99) > water resources (1.81). Guo et al. (2014) also noted that residents in Urumqi had a relatively weak awareness of waste classification [35]. By contrast, satisfaction with green status and environmental information transparency was relatively higher, although overall satisfaction levels remained modest. With rapid urbanization, the fragmentation of urban green spaces in Urumqi has increased [36]. Satisfaction with water resources was the lowest, possibly due to urbanization accelerating water scarcity and pollution [37], which has gradually increased the human-river distance in the last decades [38].

Figure 3. Public participation in ecological civilization construction. (a) Residents’ perceptions and willingness to participate in ecological civilization construction. EC—ecological cognition; EA—ecological attention; SC—subjective consciousness; SD—support degree; CTP—confidence to participate; WTP—willingness to participate. (b) Residents’ satisfaction with ecological civilization construction. GS—green status; AQ—air quality; WM—waste management; WR—water resources; EIT—environmental information transparency. The color scale (1–5) represents the option scores.

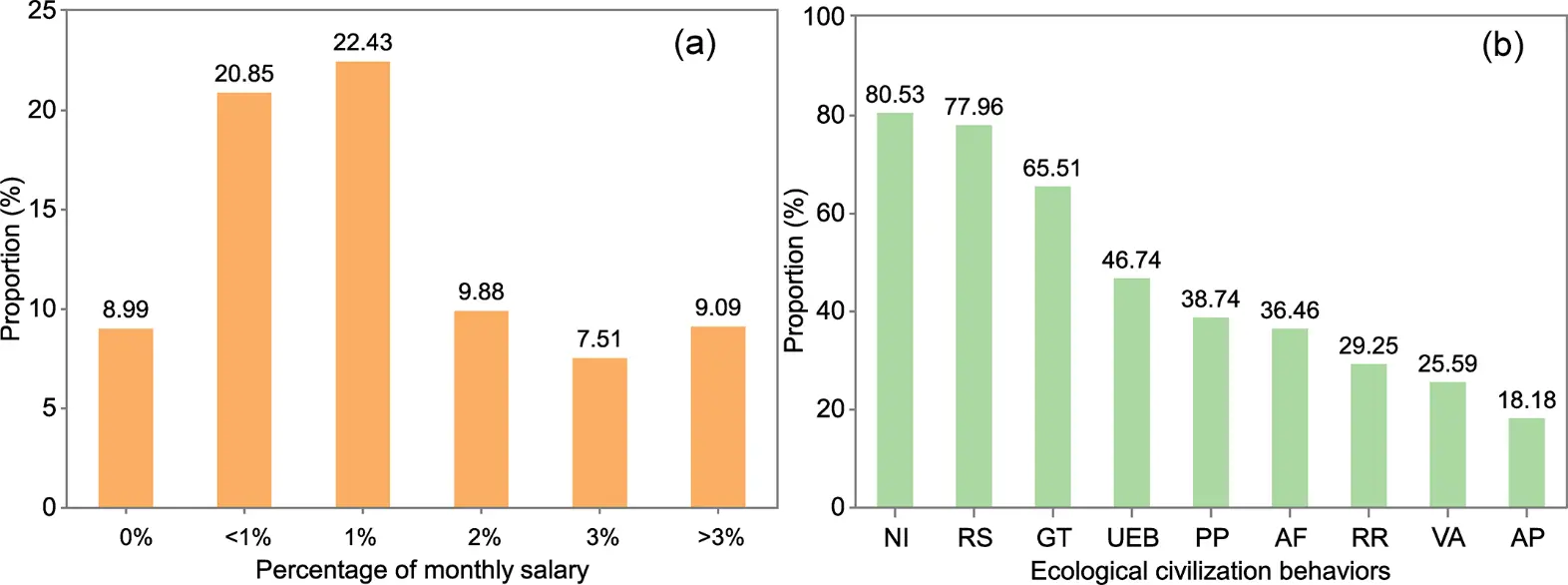

Behaviors and lifestyles play a crucial role in advancing sustainable development [39]. This study examined residents’ behaviors related to the construction of ecological civilization (Figure 4). Figure 4a illustrates residents’ willingness to allocate a portion of their monthly income to ecological civilization initiatives. Many respondents were willing to contribute less than 1% (20.85%) or exactly 1% (22.43%) of their monthly income, whereas relatively few residents were willing to contribute more than 3% (9.09%). Figure 4b depicts the frequency of residents’ ecological civilization behaviors. The most common practices were no littering (80.53%), resource conservation (77.96%), and green travel (65.51%), followed by using ecological bags (46.74%), plant protection (38.74%), and afforestation (36.46%). Less prevalent behaviors included resource recycling (29.25%), volunteer activities (25.59%), and animal protection (18.18%). Overall, the results indicate that although residents express a moderate willingness to contribute financially, their behavioral engagement is primarily concentrated on low-cost and habitual practices, with relatively limited participation in more demanding or collective ecological activities. Kathleen Segerson (2013) pointed out that reducing barriers and making it easier to participate may help translate this willingness into voluntary approaches and real action [40].

Figure 4. Residents’ ecological civilization behaviors. (a) Residents’ willingness to allocate monthly income to ecological civilization (percentage of monthly salary). (b) Residents’ ecological civilization behaviors. NI—no littering; RS—resource saving; GT—green travel; UEB—use of ecological bags; PP—plant protection; AF—afforestation; RR—resource recycling; VA—volunteer activities; AP—animal protection.

3.2. The Influence of Socio-Demographic Characteristics on Public Participation in Ecological Civilization Construction

Table 3 presents the influence of socio-demographic characteristics on public participation in ecological civilization construction. Most groups scored between 2.5 and 3.5, indicating that overall public perception and satisfaction with ecological civilization construction were moderately positive. Specifically, males scored significantly higher than females in most perception indicators (ecological cognition, ecological attention, and confidence to participate) and satisfaction indicators (green status, air quality, waste management, water resources, and environmental information transparency) (p < 0.05), whereas females exhibited a significantly higher willingness to participate (p < 0.05). This pattern indicates that while men may show higher perception and satisfaction, women’s higher willingness to participate underscores their potential as key drivers of community-based ecological initiatives [30]. Older respondents (>50 years) exhibited significantly higher scores in ecological cognition and ecological attention than younger groups (p < 0.05), while respondents <20 years reported the highest satisfaction with environmental information transparency. This finding implies that younger participants may be more sensitive to the accessibility and openness of environmental information, highlighting the role of transparency in fostering future-oriented ecological participation [41].

Income level was positively associated with several indicators (confidence to participate, and satisfaction with green status, water resources, and environmental information transparency), with high-income groups scoring significantly better than middle- and low-income groups (p < 0.05). By contrast, higher educational attainment (bachelor’s, master’s, and doctoral degrees) was associated with lower environmental satisfaction, whereas lower-educated groups (primary school and below, junior middle school, and high school) reported higher satisfaction with green status, waste management, water resources, and transparency of environmental information. Respondents with a high school education showed the highest willingness to participate. These findings suggest that economic capacity enhances both confidence and satisfaction in ecological participation, while the inverse relationship between education and environmental satisfaction may reflect higher expectations among the well-educated. Individuals with higher socioeconomic status may exhibit more positive attitudes and greater satisfaction with environmental conditions, whereas those with higher education tend to demonstrate stronger critical thinking and social responsibility, leading to higher expectations for environmental quality and consequently lower satisfaction [33].

Occupational differences were mainly reflected in environmental satisfaction: retired respondents reported significantly lower satisfaction with waste management (p < 0.05), while freelancers reported significantly higher satisfaction with water resources (p < 0.05). However, no significant occupational differences were observed for ecological cognition, subjective consciousness, support degree, and willingness to participate. Respondents with environment-related educational backgrounds scored significantly higher in ecological cognition and support degree than those from other fields (p < 0.05), while differences in other indicators (ecological cognition, subjective consciousness, confidence to participate, willingness to participate, and satisfaction with green status, air quality, water resources, and environmental information transparency) were not significant between the two groups. These results indicate that occupational status has only a limited effect on participation, whereas an environment-related educational background enhances cognitive and supportive dimensions, underscoring the importance of environmental literacy in shaping public engagement [42].

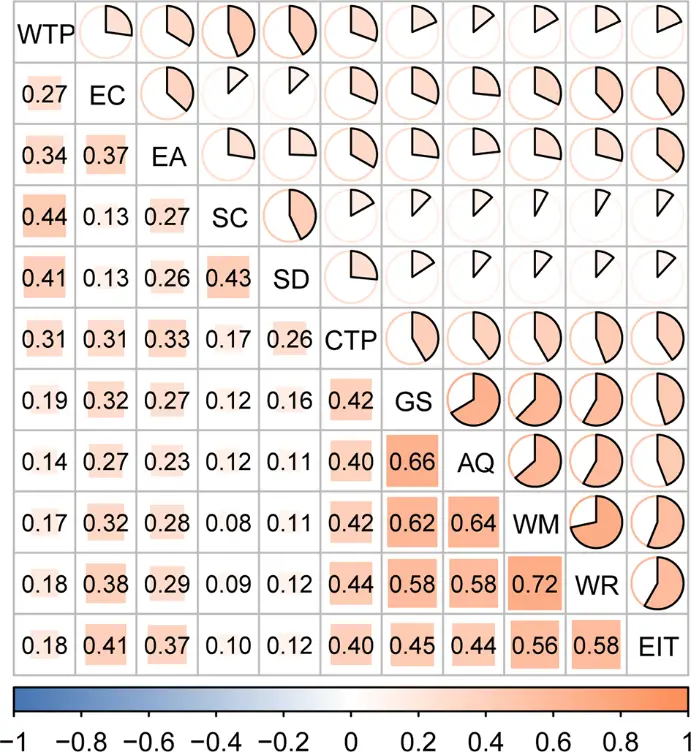

Pearson’s correlation analysis was conducted to examine relationships among residents’ perception, satisfaction level, and willingness to participate (Figure 5). The results show that most variables are significantly and positively correlated. Specifically, willingness to participate is significantly associated with ecological cognition (r = 0.27, p < 0.01), ecological attention (r = 0.34, p < 0.01), subjective consciousness (r = 0.44, p < 0.01), support degree (r = 0.41, p < 0.01), and confidence to participate (r = 0.31, p < 0.01), suggesting that stronger pro-environmental awareness and attitudes are linked to higher willingness to participate [31]. Satisfaction indicators also exhibit strong interrelationships, particularly between residents’ satisfaction with waste management and water resources (r = 0.72, p < 0.01), green status and air quality (r = 0.66, p < 0.01), air quality and waste management (r = 0.64, p < 0.01), and water resources and environmental information transparency (r = 0.58, p < 0.01). These results indicate that residents’ satisfaction with ecological civilization construction tends to be consistent across different domains. Additionally, confidence to participate shows moderate positive correlations with several satisfaction indicators (r = 0.40–0.44, p < 0.01), implying that higher satisfaction levels foster stronger confidence to participate [43]. These findings indicate that residents’ perception and satisfaction jointly shape their willingness to participate, underscoring the critical role of integrated environmental perception in promoting public participation in ecological civilization construction.

Table 3. The influence of socio-demographic characteristics on public participation in ecological civilization construction.

|

Variables |

EC |

EA |

SC |

SD |

CTP |

WTP |

GS |

AQ |

WM |

WR |

EIT |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Gender |

Male |

2.86 ± 0.87a |

3.04 ± 0.68a |

4.64 ± 0.73a |

3.66 ± 0.61a |

3.03 ± 0.79a |

3.35 ± 0.66b |

2.60 ± 0.90a |

2.46 ± 0.94a |

2.12 ± 0.94a |

2.00 ± 1.18a |

2.52 ± 0.93a |

|

Female |

2.66 ± 0.76b |

2.87 ± 0.69b |

4.69 ± 0.57a |

3.69 ± 0.57a |

2.92 ± 0.85b |

3.43 ± 0.59a |

2.44 ± 0.83b |

2.26 ± 0.91b |

1.88 ± 0.91b |

1.65 ± 1.19b |

2.31 ± 0.93b |

|

|

Age |

<20 |

3.00 ± 0.93a |

3.19 ± 0.66ab |

4.86 ± 0.35a |

3.77 ± 0.43a |

3.30 ± 0.80a |

3.58 ± 0.63a |

2.81 ± 0.96a |

2.79 ± 1.01a |

2.42 ± 1.01a |

2.09 ± 1.34ab |

2.86 ± 0.97a |

|

20–30 |

2.70 ± 0.78b |

2.88 ± 0.67c |

4.67 ± 0.63b |

3.69 ± 0.56a |

2.93 ± 0.79a |

3.37 ± 0.61a |

2.45 ± 0.83a |

2.25 ± 0.88b |

1.92 ± 0.87b |

1.73 ± 1.14b |

2.37 ± 0.91b |

|

|

31–40 |

2.78 ± 0.89ab |

3.01 ± 0.78b |

4.59 ± 0.78b |

3.65 ± 0.65a |

2.99 ± 0.92a |

3.43 ± 0.69a |

2.59 ± 0.97a |

2.48 ± 1.02ab |

2.09 ± 1.07ab |

1.82 ± 1.36ab |

2.41 ± 1.03ab |

|

|

41–50 |

2.92 ± 0.84a |

3.09 ± 0.64ab |

4.60 ± 0.64b |

3.55 ± 0.66a |

3.08 ± 0.85a |

3.41 ± 0.64a |

2.70 ± 0.90a |

2.67 ± 0.95a |

2.19 ± 1.02ab |

2.23 ± 1.17a |

2.45 ± 0.95ab |

|

|

>50 |

3.04 ± 0.77a |

3.35 ± 0.57a |

4.83 ± 0.49ab |

3.61 ± 0.72a |

2.91 ± 1.00a |

3.52 ± 0.59a |

2.48 ± 0.67a |

2.67 ± 0.96ab |

1.74 ± 0.69b |

1.70 ± 0.88ab |

2.30 ± 0.70ab |

|

|

Average monthly income (¥) |

<2000 |

2.76 ± 0.77a |

2.91 ± 0.70a |

4.71 ± 0.55a |

3.68 ± 0.58a |

2.89 ± 0.89ab |

3.43 ± 0.60a |

2.47 ± 0.85b |

2.32 ± 0.93ab |

1.97 ± 0.93a |

1.72 ± 1.25ab |

2.39 ± 0.97a |

|

2000–3000 |

2.83 ± 0.80a |

2.94 ± 0.76a |

4.67 ± 0.55a |

3.66 ± 0.54a |

3.14 ± 0.76a |

3.40 ± 0.59a |

2.69 ± 0.86a |

2.59 ± 0.95a |

2.20 ± 0.98a |

2.08 ± 1.20a |

2.52 ± 0.97a |

|

|

3001–5000 |

2.68 ± 0.82a |

2.98 ± 0.65a |

4.65 ± 0.66a |

3.66 ± 0.60a |

3.03 ± 0.72a |

3.36 ± 0.62a |

2.46 ± 0.86b |

2.34 ± 0.89ab |

1.96 ± 0.89a |

1.80 ± 1.10a |

2.40 ± 0.89a |

|

|

5001–10,000 |

2.74 ± 0.88a |

2.96 ± 0.65a |

4.59 ± 0.85a |

3.71 ± 0.63a |

2.75 ± 0.89b |

3.32 ± 0.75a |

2.40 ± 0.85b |

2.07 ± 0.86b |

1.76 ± 0.86ab |

1.62 ± 1.12ab |

2.21 ± 0.86ab |

|

|

>10,000 |

3.00 ± 1.23a |

3.23 ± 0.61a |

4.45 ± 1.22a |

3.68 ± 0.72a |

3.36 ± 0.85a |

3.64 ± 0.73a |

2.95 ± 1.00a |

2.64 ± 1.09a |

2.27 ± 1.20a |

2.32 ± 1.46a |

2.86 ± 1.04a |

|

|

Education level |

Primary school and below |

2.59 ± 0.88a |

2.74 ± 1.04a |

4.36 ± 0.87a |

3.41 ± 0.88a |

3.18 ± 1.02ab |

3.33 ± 0.77ab |

2.97 ± 0.99a |

2.97 ± 1.06a |

2.51 ± 1.23a |

2.26 ± 1.50a |

2.41 ± 1.07ab |

|

Junior middle school |

2.74 ± 1.05a |

3.04 ± 0.78a |

4.59 ± 0.60a |

3.56 ± 0.67a |

2.97 ± 0.99ab |

3.37 ± 0.59ab |

2.70 ± 0.92a |

2.64 ± 0.92a |

2.24 ± 1.02ab |

2.03 ± 1.36a |

2.52 ± 1.05ab |

|

|

High school |

2.96 ± 0.89a |

3.06 ± 0.80a |

4.65 ± 0.55a |

3.74 ± 0.44a |

3.25 ± 0.77a |

3.58 ± 0.58a |

2.84 ± 0.95a |

2.80 ± 1.02a |

2.48 ± 1.15a |

2.27 ± 1.39a |

2.70 ± 1.07a |

|

|

Specialty |

2.85 ± 0.77a |

2.90 ± 0.74a |

4.63 ± 0.68a |

3.64 ± 0.55a |

3.04 ± 0.86ab |

3.33 ± 0.67b |

2.68 ± 0.84a |

2.55 ± 0.89a |

2.15 ± 0.92ab |

2.17 ± 1.08a |

2.49 ± 0.93ab |

|

|

Bachelor |

2.69 ± 0.78a |

2.94 ± 0.62a |

4.68 ± 0.63a |

3.69 ± 0.58a |

2.95 ± 0.74b |

3.38 ± 0.60ab |

2.43 ± 0.84b |

2.27 ± 0.87b |

1.90 ± 0.83ab |

1.75 ± 1.07b |

2.41 ± 0.88ab |

|

|

Master |

2.76 ± 0.71a |

2.92 ± 0.60a |

4.78 ± 0.47a |

3.72 ± 0.56a |

2.84 ± 0.81b |

3.41 ± 0.58ab |

2.27 ± 0.72b |

2.02 ± 0.79b |

1.68 ± 0.73b |

1.36 ± 1.06c |

2.20 ± 0.88b |

|

|

PhD |

2.77 ± 0.96a |

3.13 ± 0.70a |

4.44 ± 1.23a |

3.79 ± 0.62a |

2.90 ± 0.91ab |

3.41 ± 0.88ab |

2.44 ± 1.00ab |

2.03 ± 1.06b |

1.85 ± 1.04b |

1.62 ± 1.37ab |

2.33 ± 0.98ab |

|

|

Occupation |

Civil servant |

2.80 ± 0.83a |

3.05 ± 0.64ab |

4.68 ± 0.69a |

3.72 ± 0.52a |

2.99 ± 0.82a |

3.35 ± 0.59a |

2.48 ± 0.88b |

2.41 ± 0.95a |

1.98 ± 0.88b |

1.80 ± 1.14a |

2.49 ± 0.90a |

|

Enterprise staff |

2.75 ± 0.88a |

2.98 ± 0.68ab |

4.59 ± 0.76a |

3.67 ± 0.60a |

3.11 ± 0.77a |

3.39 ± 0.69a |

2.64 ± 0.92a |

2.47 ± 0.97a |

2.09 ± 1.02a |

2.07 ± 1.21a |

2.45 ± 0.94a |

|

|

Technical personnel |

2.98 ± 0.89a |

3.18 ± 0.54a |

4.64 ± 0.71a |

3.67 ± 0.52a |

3.11 ± 0.75a |

3.24 ± 0.80a |

2.62 ± 0.91a |

2.53 ± 0.97a |

2.07 ± 1.03a |

2.11 ± 1.13a |

2.62 ± 0.94a |

|

|

Teacher |

2.77 ± 0.81a |

2.95 ± 0.79ab |

4.70 ± 0.56a |

3.62 ± 0.59a |

2.83 ± 0.81b |

3.42 ± 0.56a |

2.40 ± 0.79b |

2.15 ± 0.92b |

1.98 ± 0.89b |

1.77 ± 1.08b |

2.30 ± 0.96b |

|

|

Student |

2.71 ± 0.69a |

2.88 ± 0.62b |

4.76 ± 0.49a |

3.73 ± 0.53a |

2.88 ± 0.81b |

3.40 ± 0.59a |

2.38 ± 0.80b |

2.16 ± 0.85b |

1.85 ± 0.81b |

1.58 ± 1.13b |

2.34 ± 0.93b |

|

|

Businesses |

2.88 ± 0.88a |

3.12 ± 0.63ab |

4.65 ± 0.53a |

3.72 ± 0.59a |

3.16 ± 0.72a |

3.44 ± 0.50a |

2.60 ± 0.88a |

2.40 ± 0.93a |

2.12 ± 1.03a |

1.95 ± 1.15a |

2.51 ± 0.88a |

|

|

Freelance |

2.70 ± 0.89a |

2.87 ± 0.82ab |

4.55 ± 0.70a |

3.58 ± 0.64a |

3.02 ± 0.97a |

3.50 ± 0.58a |

2.71 ± 0.87a |

2.62 ± 0.93a |

2.25 ± 1.03a |

2.04 ± 1.32a |

2.50 ± 1.02a |

|

|

Retired personnel |

2.86 ± 1.07a |

2.86 ± 1.07ab |

4.14 ± 1.46a |

3.43 ± 1.13a |

3.29 ± 0.76a |

3.14 ± 1.07a |

2.29 ± 0.95b |

2.57 ± 1.13a |

1.57 ± 0.79b |

1.71 ± 1.38b |

2.71 ± 0.76a |

|

|

Others |

2.71 ± 0.85a |

2.81 ± 0.80ab |

4.65 ± 0.62a |

3.56 ± 0.74a |

2.78 ± 0.86b |

3.40 ± 0.67a |

2.45 ± 0.91a |

2.30 ± 0.85a |

1.83 ± 0.93b |

1.51 ± 1.24b |

2.13 ± 0.92b |

|

|

Academic background |

Majors related to environmental science |

2.86 ± 0.71a |

2.98 ± 0.65a |

4.71 ± 0.61a |

3.72 ± 0.56a |

2.99 ± 0.78a |

3.41 ± 0.61a |

2.45 ± 0.83a |

2.22 ± 0.90b |

1.91 ± 0.86b |

1.71 ± 1.18a |

2.41 ± 0.91a |

|

Others |

2.70 ± 0.86b |

2.93 ± 0.71a |

4.64 ± 0.67a |

3.65 ± 0.60b |

2.96 ± 0.85a |

3.39 ± 0.63a |

2.55 ± 0.89a |

2.42 ± 0.94a |

2.03 ± 0.97a |

1.86 ± 1.20a |

2.41 ± 0.95a |

|

Notes: EC—ecological cognition; EA—ecological attention; SC—subjective consciousness; SD—support degree; CTP—confidence to participate; WTP—willingness to participate. GS—green status; AQ—air quality; WM—waste management; WR—water resources; EIT—environmental information transparency; Different letters (a, b, c) indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) among socio-demographic variables (gender, age, income, education, occupation, academic background) for each variable (EC, EA, SC, SD, CTP, WTP, GS, AQ, WM, WR, EIT), based on one-way ANOVA and t-test.

Figure 5. Pearson’s correlation analysis of residents’ perception, satisfaction, and willingness to participate in ecological civilization construction. WTP—willingness to participate; EC—ecological cognition; EA—ecological attention; SC—subjective consciousness; SD—support degree; CTP—confidence to participate; GS—green status; AQ—air quality; WM—waste management; WR—water resources; EIT—environmental information transparency.

3.3. Public Participation in Ecological Civilization Construction

To identify factors hindering ecological civilization construction, this study further examined the main obstacles, which were categorized as uncivil behaviors, human factors, natural factors, political factors, and economic factors (Table 4). Uncivil behaviors were the most frequently cited. Among them, littering of household waste was the most prevalent issue, reported by 80.63% of respondents. Other major concerns included noise pollution (47.43%), vehicle exhaust emissions (46.05%), sewage discharge (43.08%), and vegetation destruction (36.26%).

Human factors primarily reflected limited public awareness and participation. Notably, 41.6% of respondents reported having no time to participate, 41.4% did not know how to participate, 39.23% were unfamiliar with relevant laws and regulations, and 25.2% expressed little interest in ecological civilization.

Natural factors also posed significant challenges. The most critical issues included air pollution (51.88%), freshwater shortages (50%), worsening water pollution (40.71%), sandstorms (40.81%), and vegetation degradation (38.04%). Li et al. (2008) identified the mixing of local anthropogenic aerosols with transported soil dust and low wind speed as the major factors of air pollution in Urumqi [44]. It should be noted that Urumqi experienced severe dust pollution during snowfall in 2018. The black snow, popularly referred to as “Tiramisu”, aroused widespread public concern. Additionally, Urumqi is the farthest city from the sea in the world. Due to its geographical location and the effects of climate change, Urumqi has experienced drought nearly every year since 2000 [27].

Political factors were comparatively less emphasized: 60.18% of respondents reported a lack of environmental protection organizations and participation platforms, whereas only 3.56% mentioned the absence of relevant laws and regulations. This pattern suggests that the availability of institutions and organizations may exert a stronger influence on public participation than formal regulatory frameworks. Active social organizations can enhance the public’s willingness to participate in environmental supervision [45].

Economic factors reflected the tension between development and protection. In total, 78.36% of respondents agreed that ecological civilization and economic development should be complementary, whereas 20.75% perceived conflicts between ecological protection and economic growth. This suggests that many residents endorse the view that “green hills and clear waters are as valuable as mountains of gold and silver”, and hope that economic development and ecological protection can advance in harmony. Balancing ecological protection with economic development is particularly important for achieving the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals [45].

Overall, the findings suggest that uncivil behaviors and natural pressures are the most visible obstacles, whereas institutional deficiencies and economic contradictions represent underlying structural challenges. These results highlight the need to strengthen public awareness, refine regulatory frameworks, and enhance ecological-economic coordination to overcome these barriers.

Table 4. Obstacles to ecological civilization construction.

|

Category |

Main Reasons |

Number of Respondents |

Proportion (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Uncivil behaviors |

Littering of household waste |

816 |

80.63 |

|

Sewage discharge |

436 |

43.08 |

|

|

Vegetation destruction |

367 |

36.26 |

|

|

Vehicle exhaust emissions |

466 |

46.05 |

|

|

Noise pollution |

480 |

47.43 |

|

|

Others |

58 |

5.73 |

|

|

Human factors |

The public has no time to participate |

421 |

41.60 |

|

Environmental protection is seen as the responsibility of the government |

68 |

6.72 |

|

|

Residents are not interested in ecological civilization |

62 |

6.13 |

|

|

Residents are not familiar with relevant laws and regulations |

255 |

25.20 |

|

|

The public did not know how to participate |

397 |

39.23 |

|

|

The awareness of public participation is weak |

419 |

41.40 |

|

|

Natural factors |

Freshwater shortages |

506 |

50.00 |

|

Soil degradation |

349 |

34.49 |

|

|

Sandstorms are becoming more serious |

413 |

40.81 |

|

|

Vegetation is seriously damaged |

385 |

38.04 |

|

|

Air pollution is becoming more serious |

525 |

51.88 |

|

|

Worsening water pollution |

412 |

40.71 |

|

|

Intensifying the greenhouse effect |

271 |

26.78 |

|

|

Nonrenewable energy consumption is increasing |

275 |

27.17 |

|

|

Political factors |

Lack of relevant laws and regulations |

36 |

3.56 |

|

Lack of environmental protection organizations and participation platforms |

609 |

60.18 |

|

|

Economic factors |

Contradiction between ecological protection and economic development |

210 |

20.75 |

|

Complementarity between ecological civilization and economic construction |

793 |

78.36 |

3.4. Recommendations and Limitations

In the final section, this study investigated the measures identified by respondents as important for promoting ecological civilization construction (Table 5). The results indicate that government policy support (83.60%) was considered the most critical measure, highlighting the dominant role of governmental intervention in advancing ecological civilization. This was followed by improving civic literacy (67.49%) and media publicity (61.76%), emphasizing the importance of enhancing public awareness and fostering ecological values through education and information dissemination. Prior research showed that after the implementation of the ecological civilization development policy, the overall progress rate of ecological civilization increased by 14.94% between 2012 and 2017 [46]. Moreover, integrating the concept of ecological civilization into education plays a key role in addressing environmental problems [47].

Other frequently mentioned measures included green economic transformation (45.36%) and green transportation (37.25%). In contrast, advanced technical support (32.81%), incentive and accountability mechanisms (29.15%), and enterprise support (19.76%) were cited less frequently. Strengthening green innovation is fundamental to building China’s new era of ecological civilization construction and to participating in the global green industrial revolution [48].

According to our findings, we recommend the following actions to advance ecological civilization: (1) strengthen governmental policy support to guarantee the public’s right to participate; (2) improve civic literacy to mobilize participation; (3) increase publicity for ecological civilization construction through diverse media channels, particularly digital and social platforms; (4) accelerate the transition to a green economy by prioritizing renewable energy (e.g., solar and wind), circular economy, and ecotourism; and (5) enhance sustainable transport systems by increasing investment in mass transit (e.g., metros and buses) and encouraging low-carbon mobility options.

Table 5. Measures for promoting ecological civilization construction.

|

Answers |

Proportion (%) |

|---|---|

|

Government policy support |

83.60 |

|

Improving civic literacy |

67.49 |

|

Media publicity |

61.76 |

|

Green economic transformation |

45.36 |

|

Green transportation |

37.25 |

|

Advanced technical support |

32.81 |

|

Incentive and accountability mechanisms |

29.15 |

|

Enterprise support |

19.76 |

|

Others |

1.68 |

Despite these interesting results, this study has some limitations. The contents of the questionnaire were intended to design several easy questions to answer for improving the citizens’ response rate, therefore, our online survey cannot be regarded as a comprehensive analysis of citizens’ participation in ecological civilization construction. Moreover, the sample covers only Urumqi, which limits the generalizability of the findings to other regions. Additionally, the questionnaire design lacked consistency, making it difficult to integrate all variables into a comprehensive modeling analysis. Future studies may broaden the geographic scope, consider additional factors, and investigate the participation of stakeholders across various fields in ecological civilization construction.

4. Conclusions

Residents exhibited a strong subjective awareness of public participation in ecological civilization construction (mean score = 4.66). However, ecological cognition (2.75) and participation confidence (2.97) were relatively weak. Satisfaction levels were relatively higher for green status (2.51) and information transparency (2.41), yet overall satisfaction was moderate, with water resources (1.81) and waste management (1.99) identified as key concerns. Residents showed a moderate willingness to contribute financially and primarily engaged in low-cost, habitual ecological practices, whereas participation in more demanding or collective activities remained limited. Significant differences were observed across socio-demographic variables (p < 0.05). Uncivilized behaviors and natural pressures emerged as the most visible obstacles. Strong government leadership, active public engagement, and effective media communication play a vital role in advancing ecological civilization construction. Future studies should consider a wider regional coverage and analyze stakeholders’ participation in ecological civilization construction.

Statement of the Use of Generative AI and AI-Assisted Technologies in the Writing Process

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT to improve the readability and language. After using this tool, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the published article.

Acknowledgments

We thank all those who provided us with suggestions during the questionnaire design process.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Ü.H. and T.A.; Methodology: W.W.; Software, W.W.; Validation, W.W.; Formal Analysis, Ü.H. and L.S.; Investigation, W.W. and G.L.; Data Curation, W.W.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, W.W.; Writing—Review & Editing, L.S. and E.A.; Visualization, L.S.; Supervision, Ü.H., T.A. and E.A.; Project Administration, Ü.H.; Funding Acquisition, Ü.H. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

All respondents in this study were informed about its purpose and assured of the privacy and confidentiality of their participation.

Data Availability Statement

Data is available upon request from the author.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 32560284), the Regional Collaborative Innovation Program–Shanghai Cooperation Organization Science and Technology Partnership and International Cooperation Project of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region (No. 2023E01026), the Russian Scientific Foundation (Agreement No. 23–16–20003, dated 20 April 2023), the Saint-Petersburg Scientific Foundation (Agreement No. 23–16–20003, dated 5 May 2023), and China Scholarship Council (201907010003).

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

-

He J. A Theoretical Thinking About Ecological Civilization Construction. In Proceedings of the 2017 6th International Conference on Energy and Environmental Protection (ICEEP 2017), Zhuhai, China, 29–30 June 2017; Atlantis Press: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2017; Volume 143, pp. 665–668. doi:10.2991/iceep-17.2017.118. [Google Scholar]

-

Xue B, Han B, Li H, Gou X, Yang H, Thomas H, et al. Understanding ecological civilization in China: From political context to science. Ambio 2023, 52, 1895–1909. doi:10.1007/s13280-023-01897-2. [Google Scholar]

-

Zhang X, Wang Y, Qi Y, Wu J, Liao W, Shui W, et al. Evaluating the trends of China’s ecological civilization construction using a novel indicator system. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 133, 910–923. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.06.034. [Google Scholar]

-

Zhang M, Liu Y, Wu J, Wang T. Index system of urban resource and environment carrying capacity based on ecological civilization. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2018, 68, 90–97. doi:10.1016/j.eiar.2017.11.002. [Google Scholar]

-

Zhang L, Yang J, Li D, Liu H, Xie Y, Song T, et al. Evaluation of the ecological civilization index of China based on the double benchmark progressive method. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 222, 511–519. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.02.173. [Google Scholar]

-

Gu Y, Wu Y, Liu J, Xu M, Zuo T. Ecological civilization and government administrative system reform in China. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 155, 104654. doi:10.1016/j.resconrec.2019.104654. [Google Scholar]

-

Hansen MH, Li H, Svarverud R. Ecological civilization: Interpreting the Chinese past, projecting the global future. Glob. Environ. Change 2018, 53, 195–203. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2018.09.014. [Google Scholar]

-

Zhang W, Li H, An X. Ecological Civilization Construction is the Fundamental Way to Develop Low-carbon Economy. Energy Procedia 2011, 5, 839–843. doi:10.1016/j.egypro.2011.03.148. [Google Scholar]

-

Dong L, Chen H. China’s path to a global ecological civilization: Concepts and practices for sustainable development. Chin. J. Popul. Resour. Environ. 2025, 23, 295–300. doi:10.1016/j.cjpre.2025.07.001. [Google Scholar]

-

Weins NW, Zhu AL, Qian J, Barbi Seleguim F, da Costa Ferreira L. Ecological Civilization in the making: The ‘construction’ of China’s climate-forestry nexus. Environ. Sociol. 2022, 9, 6–19. doi:10.1080/23251042.2022.2124623. [Google Scholar]

-

Chen S, Liu N. Research on Citizen Participation in Government Ecological Environment Governance Based on the Research Perspective of “Dual Carbon Target”. J. Environ. Public Health 2022, 2022, 5062620. doi:10.1155/2022/5062620. [Google Scholar]

-

Dong L, Wang Z, Zhou Y. Public Participation and the Effect of Environmental Governance in China: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4442. doi:10.3390/su15054442. [Google Scholar]

-

Wang R, Qi R, Cheng J, Zhu Y, Lu P. The behavior and cognition of ecological civilization among Chinese university students. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 243, 118464. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.118464. [Google Scholar]

-

Jarvis RM, Bollard Breen B, Krägeloh CU, Billington DR. Citizen science and the power of public participation in marine spatial planning. Mar. Policy 2015, 57, 21–26. doi:10.1016/j.marpol.2015.03.011. [Google Scholar]

-

Isaac NJB, van Strien AJ, August TA, de Zeeuw MP, Roy DB, Anderson B. Statistics for citizen science: extracting signals of change from noisy ecological data. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2014, 5, 1052–1060. doi:10.1111/2041-210x.12254. [Google Scholar]

-

Toomey AH, Strehlau-Howay L, Manzolillo B, Thomas C. The place-making potential of citizen science: Creating social-ecological connections in an urbanized world. Landsc. Urban Plann. 2020, 200, 103824. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2020.103824. [Google Scholar]

-

Tsouni A, Sigourou S, Pagana V, Tsoutsos M-C, Dimitriadis P, Sargentis GF, et al. Multiparameter Flood Risk Assessment and Management Planning at High Spatial Resolution in the Region of Attica, Greece. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2025, 18, 25966–25979. doi:10.1109/jstars.2025.3613569. [Google Scholar]

-

Dickinson JL, Shirk J, Bonter D, Bonney R, Crain RL, Martin J, et al. The current state of citizen science as a tool for ecological research and public engagement. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2012, 10, 291–297. doi:10.1890/110236. [Google Scholar]

-

Lewandowski EJ, Oberhauser KS. Butterfly citizen scientists in the United States increase their engagement in conservation. Biol. Conserv. 2017, 208, 106–112. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2015.07.029. [Google Scholar]

-

Fu H, Fu L, Dávid LD, Zhong Q, Zhu K. Bridging Gaps towards the 2030 Agenda: A Data-Driven Comparative Analysis of Government and Public Engagement in China towards Achieving Sustainable Development Goals. Land 2024, 13, 818. doi:10.3390/land13060818. [Google Scholar]

-

Xiao Y, Chen J, Yin P. Institutionalization of Ecological Civilization Construction in China: Measurements and Influencing Factors. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1719. doi:10.3390/su17041719. [Google Scholar]

-

Thøgersen J, Ölander F. Spillover of environment-friendly consumer behaviour. J. Environ. Psychol. 2003, 23, 225–236. doi:10.1016/s0272-4944(03)00018-5. [Google Scholar]

-

Morren M, Grinstein A. Explaining environmental behavior across borders: A meta-analysis. J. Environ. Psychol. 2016, 47, 91–106. doi:10.1016/j.jenvp.2016.05.003. [Google Scholar]

-

Shi L, Halik U, Mamat Z, Aishan T, Welp M. Identifying mismatches of ecosystem services supply and demand under semi-arid conditions: The case of the Oasis City Urumqi, China. Integr. Environ. Assess. Manag. 2021, 17, 1293–1304. doi:10.1002/ieam.4471. [Google Scholar]

-

Shi L, Halik Ü, Abliz A, Mamat Z, Welp M. Urban Green Space Accessibility and Distribution Equity in an Arid Oasis City: Urumqi, China. Forests 2020, 11, 690. doi:10.3390/f11060690. [Google Scholar]

-

Zhang S, Lei J, Zhang X, Tong Y, Lu D, Fan L, et al. Assessment and optimization of urban spatial resilience from the perspective of life circle: A case study of Urumqi, NW China. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2024, 109, 105527. doi:10.1016/j.scs.2024.105527. [Google Scholar]

-

Li Q, Wang W, Jiang X, Lu D, Zhang Y, Li J. Optimizing the reuse of reclaimed water in arid urban regions: A case study in Urumqi, Northwest China. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2019, 51, 101702. doi:10.1016/j.scs.2019.101702. [Google Scholar]

-

Chen S, Halik Ü, Shi L, Fu W, Gan L, Welp M. Habitat Quality Dynamics in Urumqi over the Last Two Decades: Evidence of Land Use and Land Cover Changes. Land 2025, 14, 84. doi:10.3390/land14010084. [Google Scholar]

-

Vicente-Molina MA, Fernández-Sáinz A, Izagirre-Olaizola J. Environmental knowledge and other variables affecting pro-environmental behaviour: Comparison of university students from emerging and advanced countries. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 61, 130–138. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2013.05.015. [Google Scholar]

-

Liu S, Luo L. A Study on the Impact of Ideological and Political Education of Ecological Civilization on College Students’ Willingness to Act Pro-Environment: Evidence from China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2023, 20, 2608. doi:10.3390/ijerph20032608. [Google Scholar]

-

Zhang L, Yue M, Qu L, Ren B, Zhu T, Zheng R. The influence of public awareness on public participation in environmental governance: Empirical evidence in China. Environ. Res. Commun. 2024, 6, 095024. doi:10.1088/2515-7620/ad792a. [Google Scholar]

-

Liao P-S, Shaw D, Lin Y-M. Environmental Quality and Life Satisfaction: Subjective Versus Objective Measures of Air Quality. Soc. Indic. Res. 2014, 124, 599–616. doi:10.1007/s11205-014-0799-z. [Google Scholar]

-

Tang B, Tang Y, Zhou F. Determinants of public environmental satisfaction: an analysis based on socio-ecological system theory. Front. Psychol. 2025, 16, 1631240. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1631240. [Google Scholar]

-

Asilsoy B, Oktay D. Exploring environmental behaviour as the major determinant of ecological citizenship. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2018, 39, 765–771. doi:10.1016/j.scs.2018.02.036. [Google Scholar]

-

Guo B, Liu YX. Towards Integrated Municipal Solid Waste Management: A Case of Urumqi, China. Adv. Mater. Res. 2014, 878, 3–14. doi:10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMR.878.3. [Google Scholar]

-

Shi L, Zhang X, Halik Ü. The Driving Mechanism and Spatio-Temporal Nonstationarity of Oasis Urban Green Landscape Pattern Changes in Urumqi. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3123. doi:10.3390/rs17173123. [Google Scholar]

-

Wang B, Liu L, Huang G. Retrospective and prospective analysis of water use and point source pollution from an economic perspective-a case study of Urumqi, China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2017, 24, 26016–26028. doi:10.1007/s11356-017-0199-4. [Google Scholar]

-

Wang N, Sun F, Koutsoyiannis D, Iliopoulou T, Wang T, Wang H, et al. How can Changes in the Human-Flood Distance Mitigate Flood Fatalities and Displacements? Geophys. Res. Lett. 2023, 50, e2023GL105064. doi:10.1029/2023gl105064. [Google Scholar]

-

Guo B, Geng Y, Sterr T, Zhu Q, Liu Y. Investigating public awareness on circular economy in western China: A case of Urumqi Midong. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 142, 2177–2186. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.11.063. [Google Scholar]

-

Segerson K. Voluntary Approaches to Environmental Protection and Resource Management. Annu. Rev. Resour. Econ. 2013, 5, 161–180. doi:10.1146/annurev-resource-091912-151945. [Google Scholar]

-

Riedmann-Streitz C, Streitz N, Antona M, Marcus A, Margetis G, Ntoa S, et al. How to Create and Foster Sustainable Smart Cities? Insights on Ethics, Trust, Privacy, Transparency, Incentives, and Success. Int. J. Hum.–Comput. Interact. 2024, 41, 2491–2522. doi:10.1080/10447318.2024.2325175. [Google Scholar]

-

Reddy D. Scientific literacy, public engagement and responsibility in science. Cult. Sci. 2021, 4, 6–16. doi:10.1177/20966083211009646. [Google Scholar]

-

Jia H, Lin B. Does public satisfaction with government environmental performance promote their participation in environmental protection? Socioecon. Plann. Sci. 2025, 98, 102161. doi:10.1016/j.seps.2025.102161. [Google Scholar]

-

Li J, Zhuang G, Huang K, Lin Y, Xu C, Yu S. Characteristics and sources of air-borne particulate in Urumqi, China, the upstream area of Asia dust. Atmos. Environ. 2008, 42, 776–787. doi:10.1016/j.atmosenv.2007.09.062. [Google Scholar]

-

Li C, Guo Y, Wang L. Can social organizations help the public actively carry out ecological environment supervision? Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2023, 26, 12061–12107. doi:10.1007/s10668-023-03656-5. [Google Scholar]

-

Wu M, Liu Y, Xu Z, Yan G, Ma M, Zhou S, et al. Spatio-temporal dynamics of China’s ecological civilization progress after implementing national conservation strategy. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 285, 124886. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.124886. [Google Scholar]

-

Zhang B, Dong Y, Li D, Zhu J. Ecological Civilization Education: an Indispensable Part of China’s Ecological Civilization Construction Road. Int. J. Environ. Sustain. Soc. Sci. 2024, 5, 957–972. [Google Scholar]

-

Hou J, Zhou R, Ding F, Guo H. Does the construction of ecological civilization institution system promote the green innovation of enterprises? A quasi-natural experiment based on China’s national ecological civilization pilot zones. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2022, 29, 67362–67379. doi:10.1007/s11356-022-20523-4. [Google Scholar]