Gendered Mismatches in the Business Support System in Rural Sweden

Received: 02 September 2025 Revised: 09 October 2025 Accepted: 04 November 2025 Published: 10 November 2025

© 2025 The authors. This is an open access article under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

1. Introduction

Governments worldwide recognise the need to address rural decline caused by ongoing rural-to-urban migration, and the concomitant aging and shrinking of rural populations. Thus, as in other parts of the world, rural areas in Sweden are facing economic decline. Consequently, measures that support rural viability are essential [1]. Rural entrepreneurship has been increasingly recognised as a vital component of regional development and economic resilience in Sweden [2]. Public and private business support systems have been established to foster innovation, sustainability, and growth in rural enterprises. Such support may include funding, advisory services, competence development, technical support, or networking. However, the funds that are dispersed for rural development in Sweden primarily benefit agriculture [3], and whilst businesses in rural areas are seen as eligible for support from the general business support system, the Swedish general business support system primarily targets manufacturing industries in the STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) sector, which is male dominated [1].

In recognition of the fact that women are underrepresented as business owners, the Swedish government had a programme designed to support women’s entrepreneurship between 2011 and 2015, although it lacked any specific provisions for rural businesses [4]. As in the UK, the USA, and the other Nordic countries [5,6,7], the program for women’s entrepreneurship was motivated by the potential of women-owned businesses to contribute to economic growth, rather than by gender equality arguments [7,8,9]. Following the 2015 agenda, the government shifted its focus towards gender mainstreaming across all its support programs, ensuring equal access to support systems for both men and women [10].

Nevertheless, persistent gender disparities continue to inform and shape the experiences and outcomes of women entrepreneurs with regard to funding [11] and access to knowledge [12]. Furthermore, while the political discourse on women’s entrepreneurship is the same in Sweden as elsewhere: ‘women are seen as an under-utilised resource for economic growth’, the business support system continues to fail in its provision of support to this untapped resource.

Gender inequality in entrepreneurship has been widely studied. The commonly held assumption that entrepreneurship is a male-dominated field consistently places women entrepreneurs in a secondary and subordinated position [6,13,14,15,16,17]. Gender stereotypes may influence the type of business she starts [18] or even deter women from starting a business in the first place [19]. Women are often found in ‘gendered niches’ of the economy, such as in the service, care, or retail sectors, which are labour-intensive and have low earnings potential [14]. Stereotypical assumptions of gender limit women’s ability to raise money from loan officers, angel investors, and venture capitalists [20,21]. Additionally, the traditional division of unpaid labour at home presents further obstacles for women entrepreneurs [22,23]. Rural women entrepreneurs may face additional obstacles due to the conservative values in rural areas [24,25].

Studies on women’s entrepreneurship policy find that such systems prioritize economic growth before gender equality [8,9,26]. Recent policy has been found to be informed by a contemporary postfeminist discourse that holds that all structural obstacles are removed [7]. This discourse informs individual solutions, such as training or confidence raising programs, and neglects structural change. The effect is that individual women are blamed for not measuring up to economic goals while structural barriers are left unaddressed [7].

We contribute to this research by examining how gender inequality in entrepreneurship is manifested in rural contexts within the context of formal business support systems [27]. In this paper, we critically examine gendered mismatches in the business support system in rural Sweden. To this aim, we investigate whether the availability and design of current business support systems actually promote the goal of rural sustainability through women-owned businesses. We also address questions of adequacy in the design and accessibility of business support systems as perceived by rural women entrepreneurs. More specifically, we ask: Do existing business support measures meet the needs of rural women entrepreneurs? If not, what can be improved?

We begin with an overview of the research literature on women’s rural entrepreneurship policy. We then provide background information on women entrepreneurs in rural Sweden, as well as an overview of existing support systems in Sweden. After presenting our method, we report on our findings from interviews with twenty rural women entrepreneurs. The paper closes with a discussion and a conclusion section.

2. Gender Bias in Rural Entrepreneurship Policy

Studies of women’s rural entrepreneurship policy are found in the domains of economic, political, and cultural geography, rural sociology, entrepreneurship studies, political science, and feminist research. Academic studies typically involve national or regional case studies or comparisons of policies across different countries. Consequently, the research field is dispersed across several disciplines and contexts. However, for European Union (EU) member states, such as Sweden, examining feminist studies on the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) is a valuable starting point to gain an overview of the research domain. This is because CAP directs and finances national rural policy in the EU member states, so CAP priorities become national priorities.

Overall, the studies we examined find that despite including the Rural Development Program (RDP) (the purpose of which was to extend support beyond farming activities), CAP still basically and almost exclusively benefits farmers [28]. Since CAP support is based on land ownership rather than occupation, and since men own most farms, CAP tends to recreate gender inequalities. Women’s unpaid farm work continues to be invisible in terms of its contribution to the economic system [29], and women’s non-agricultural businesses are not supported [30].

Several studies have focused on gender mainstreaming in CAP. Since CAP is framed within a neoliberal ideology of market-led development [31], programmes for women primarily focus on encouraging more women to start businesses; that is, these programs target women, not gender inequality [32,33,34]. Studies of local implementations of RDP through private-public partnerships have found that women are often sidelined in masculinised settings, where large-scale operations and economic goals are prioritised over the pursuit of social or civil goals, thus perpetuating rural patriarchal structures and traditional gender roles [35,36,37,38]. Similarly, a Swedish study of a regional rural development plan found that it focuses on farmers and ICT, which are typically male-dominated domains in Sweden. Gender inequality is not addressed, and gender mainstreaming is treated as an ‘information issue’ that could easily be solved if women were only informed of available programmes since the plan was (supposedly) gender mainstreamed at its inception [3]. Research from Poland indicates that a female majority in rural governance is necessary for the rural development agenda to incorporate social issues and for women to be respected as equals [39]. In the same vein, Swedish research shows that when women ‘took over’ a network designed to support women and began to craft their own agenda, it was only then that the network became truly useful in supporting rural development [40]. In short, CAP and RDP tend to (i) bypass women in farming as well as women engaged in non-farming businesses, (ii) neglect small-scale rural development initiatives in the form of social or non-profit entrepreneurship, and (iii) recreate rural patriarchal hierarchies.

However, most EU countries also have general entrepreneurship support programmes that are not explicitly earmarked for rural areas but can be accessed by entrepreneurs regardless of their location. We also note that some programmes specifically target women. As for CAP, the rationale behind the programme is economic. Programmes for women entrepreneurs are usually based on the premise that women, who constitute half of the population but only a third of business owners, represent an untapped resource for economic growth [41,42]. Since women’s businesses are often smaller than those of men, women are often positioned as “under-performing” [6,43]. Their assumed shortcomings are then addressed through programmes offering business advice and other training activities, mentorship, microfinance, role models, access to networks, and so on [42]. Special programmes for women also run the risk of being sidelined, however. A study of a Swedish programme that provided female business advisors for women entrepreneurs in rural areas found that the existing (general) advisory system undervalued the women’s program [44]. It was subsequently marginalised and eventually discontinued. Similarly, women’s networks designed to empower and encourage women to start businesses in rural Northern Ireland were found to recreate women’s marginalisation in gender niches [14], while leaving the masculinist ecosystem unchallenged [45].

Moreover, programmes aimed at women entrepreneurs have been criticised for building on false premises. It is not the case that men outperform women. Studies show that profitability and size are related to specific industries, not gender [46,47,48]. Enterprise policy is built on a masculine work norm that overlooks the gendered division of unpaid work and assumes that women have the same amount of time to devote to business as men do. The result of these misconceptions is that many programmes inadvertently position women as ‘inadequate’ and ‘weak’ [7,8]. Meanwhile, the majority of general entrepreneurship support is directed (and is thus awarded) to male-owned companies. In Sweden, one government agency, Vinnova, has an annual budget of approximately 300 million euros, much of which is aimed at companies in the STEM sector. It is thus quite apparent that entrepreneurship policy, whether it be rural or urban, is informed by male-centric norms and largely overlooks (and thus excludes) women. Women-owned businesses are often undervalued or overlooked. Nevertheless, there remains a good reason to rectify this state of affairs, both from a gender equality perspective and from a rural development perspective.

The provision of support for women entrepreneurs is particularly relevant to rural business development. In most Western states, agriculture is fully rationalised and marginally employed, and business development must come from other sectors. In Sweden, for example, agriculture, fishing, and forestry employed only 2.7 per cent of the labour force in 2023, and only a third of farmers are full-time farmers [49]. The agriculture sector accounts for only 1 percent of the gross domestic product (GDP) [50], and employment in agriculture has declined steadily over the last 150 years and continues to decline as the industrialisation of agriculture progresses. It is self-evident that rural economic development will depend on industries and economic activities beyond agriculture, notably service industries such as tourism, that are frequently women-owned and managed. Studies from Sweden show that women’s businesses are essential for service provision in rural areas, making rural life possible in the first place [1]. Women-owned businesses are thus crucial for rural viability, and there is good reason for any policymaker who is interested in rural development to adequately support these entrepreneurs.

Research shows that there is room for improvement, however. A significant hurdle for improvement is access to finance. In the EU, the well-documented gender gap in access to credit has raised concerns [51], not least in rural areas [29,52]. Previous studies have argued that women have been significantly underfunded, with only 2–3 per cent of available capital targeted towards women’s start-ups. More worryingly, it has been shown that between 2019 and 2020, this proportion decreased even further [53]. Likewise, women lack access to adequate training [53]. However, note that since the European Investment Bank has also indicated that companies led by women in the EU demonstrate a greater willingness to introduce innovative products [54], overlooking women entrepreneurs implies a significant loss of opportunity from a policy perspective.

3. The Swedish Context

As in many other industrialised countries, women comprise 30 percent of Swedish business owners [55], in both rural and urban areas. While women in urban areas are primarily engaged in providing personal and professional services, care, and education, the situation in rural areas is somewhat different. A comprehensive study based on Swedish register data showed that business ownership among both men and women was 1.5 times more common in rural areas than in urban areas. Unlike the pattern in urban areas, however, rural women were active in an extensive range of industries, whereas men were concentrated in typically male-gendered sectors, such as forestry, agriculture, construction, and transportation [48]. The ten most common industries for women—accounting for 37.4 per cent of all rural women-owned businesses—were, in descending order: forestry, hairdressing, mixed farming, restaurant, accounting, physical well-being activities, business consulting, physiotherapy, literary and artistic creation, and other personal services. However, rural women were represented in no fewer than 572 different industries, thereby contributing to a diversified business landscape in rural areas.

For women in rural areas, business ownership is typically a means to earn a living rather than a means to accumulate wealth. The study cited above mapped the mean annual disposable income across three opposing categories: men versus women, employees versus business owners, and urban versus rural. Women had a lower mean disposable income than men, irrespective of their location or work status. Women in rural business ownership had the lowest disposable income of all categories [48]. But gender did not explain the differences in business performance. The authors performed a regression analysis on business and demographic variables for businesses and their owners across the five most common industries for women in rural Sweden. They discovered that business and industry variables, rather than gender or other demographic variables, explained the economic performance of men- and women-owned businesses. Large businesses and limited companies provided their owners with a higher disposable income than small firms and sole proprietorships. Having children at home correlated positively with economic performance for both men and women. However, a ‘marriage penalty’ was identified. Marriage was an advantage for men in terms of increased disposable income, but a drawback for women [48]. Interestingly, no corresponding ‘child penalty’ was identified, which is most likely a result of the provision of shared, paid parental leave and good quality and affordable daycare for all children after their first year [23]. Consequently, Swedish women are not compelled to start a business if they wish to combine work and family, but when women in rural areas do start a business, they still devote more time to childcare and household work than their partners [48]. Furthermore, we note that they typically start businesses in sectors characterised by limited earnings and scaling potential [48].

4. Existing Business Support in Sweden

The majority of Swedish business support is aimed at manufacturing industries in the STEM sector, and consequently, it largely bypasses women business owners. Between 1996 and 2015, some support programmes specifically for women entrepreneurs were offered. However, after this period, all support programmes were gender mainstreamed, which entailed that these support systems were equally available to men and women [1]. In the following discussion, we briefly describe existing support organisations and forms of support available to women entrepreneurs in rural areas. Note that our interviewees may or may not have known about these initiatives, and consequently, they may or may not have used them.

Government authorities providing support include:

-

-

The Swedish Board of Agriculture administers the EU Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) and associated support for farmers.

-

-

The Swedish Forest Agency administers support for economically and ecologically sustainable forestry activities, including competence development for forest owners.

-

-

Vinnova, Sweden’s innovation agency, regularly issues calls for funding for innovative projects. In this regard, STEM and digital solutions dominate.

-

-

The Swedish Agency for Economic and Regional Growth (SAERG) offers knowledge, access to networks, and financing. This agency administers the EU Regional Development Program (RDP).

Public or semi-public organisations that support entrepreneurship and development projects include:

-

-

Almi, a corporation that is co-owned by the state and the regions. It offers loans to entrepreneurs, business development counselling, business training, networking, and venture capital. Almi is a vital resource for start-ups and small to medium-sized businesses.

-

-

Jobs and Society is co-financed by approximately 30 businesses, labour unions, and state authorities and is present in over 200 Swedish municipalities. It provides free start-up counselling. Ten per cent of new firms receive help from this organisation.

-

-

LEADER Sweden provides EU financing for rural development. Sweden has forty LEADER Areas and builds on voluntary engagement from the public, private, and civil society sectors. For LEADER Sweden, promoting the public good is its primary aim and takes precedence over promoting business.

-

-

Coompanion, which is financed by SAERG, assists individuals who want to start a cooperative business. It initiates local and regional development projects with a focus on cooperation and entrepreneurship and seeks third-party financing for such projects. Companion maintains twenty-five offices and provides its services at no cost.

-

-

Winnet, a non-profit association with twelve local associations unevenly distributed throughout Sweden. Winnet has participated in the development of Regional Development Plans.

-

-

Business incubators are available in locations where there is a higher education institution, usually in a Science Park which is a cooperation between the universities and regional public and private actors.

Moreover, membership-financed industry organisations play a crucial role in lobbying for and providing essential services to their members. The largest of these organisations are the The Swedish Forest Owners’ Associations, the Federation of Swedish Farmers (LRF), the Chambers of Commerce, the Entrepreneurs, and the Confederation of Swedish Enterprise. In addition, there are hundreds of specialised trade associations of varying sizes.

5. Material and Method

This paper is based on an analysis of qualitative interviews conducted within the European Horizon 2020 project, FLIARA, Female Led Innovation in Agriculture and Rural Areas (fliara.eu). FLIARA has mapped the innovation journeys of 200 women innovators in rural Europe and analysed factors that either helped or hindered them in their entrepreneurial efforts. In this paper, we focus on the twenty Swedish interviews included in the overarching study and examine what the participants had to say about policy support. It should be noted that the study’s participants were not selected based on whether they were recipients of support or whether they had participated in a specific policy programme. Given this, we refrain from evaluating the effectiveness of any one particular policy. Instead, we aimed to report on their views on policy support in general.

5.1. Selection of Participants

FLIARA aimed for a good representation in terms of rural location and sector. Type of rural location (close to a city, in a rural village, or in a remote area), and whether the innovation focused on economic, environmental, social, or cultural sustainability were therefore selection criteria in the FLIARA project. Each participating country sampled 20 women innovators across these dimensions. Moreover, half of the sample was to be based on a farm, and the other was not. The sample was to fit the matrix in Table 1.

Table 1. Selection criteria.

|

Sustainability Dimension |

Farm Based |

Rural Area Based |

|---|---|---|

|

Economic |

1 close to a city 1 in remote area 1 in rural village |

1 close to a city 1 in remote area 1 in rural village |

|

Environmental |

1 close to a city 1 in remote area 1 in rural village |

1 close to a city 1 in remote area 1 in rural village |

|

Social |

1 close to a city 1 in remote area 1 in rural village |

1 close to a city 1 in remote area 1 in rural village |

|

Cultural |

1 in any rural location |

1 in any rural location |

We used our networks and contacts, as well as records of business awards, sector-specific magazines, local newspapers, and national radio shows, to identify and select our sample. It should be noted that for the purpose of the present analysis, the various selection criteria did not correlate with any differences in the findings and will therefore not be further commented. The selection criteria did, however, ensure a wide variation of enterprises and organisations, which we believe makes the findings of greater interest than if focusing on a specific sector. Table 2 presents the participants. All but two participants were born in Sweden. The two immigrants came from Denmark and France and moved to Sweden in their twenties. Since the study was carried out in southern Sweden, no Sami women were included. The participants’ organisations have been given fictional names.

Table 2. Participants.

|

Organisation |

Org. Form |

Year Started |

Owner/Mgr |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Education |

Age |

|||

|

BerryBliss Orchards The operations include a berry farm, a farm shop, a chocolate factory, and an ice-cream parlour. The farm shop partners with over forty-five artisan food producers. They provide employment opportunities for the local village youth and have over 8000 Instagram followers. |

Ltd. |

2019 |

Univ. |

33 |

|

EcoHarvest Academy A public, upper-secondary boarding school, offering programmes and courses in animal care, organic agriculture, and gardening. Innovative farming testbeds for new technologies are used to advance agriculture, such as a biogas plant, a biorefinery plant, a bio coal plant, solar panels, simulation vehicles, a biogas tractor, and an electric smart grid. |

Public School |

2017 |

Univ. |

51 |

|

EcoMoo Farm A high-tech, eco-certified, and environmentally sustainable dairy farm that uses milking robots that the cows visit when they want to, automatic fodder dispensers, and an app for measuring and monitoring the cows’ activities and health. The 180 cows feed from ecological grass grown on the farm’s pastures. The farm’s biogas facility produces energy and natural fertilisers. |

SP |

2014 |

Vocational |

40 |

|

Eco Centre A rural knowledge centre that serves as a model for sustainable living. They run several eco-friendly, sustainable guest houses, a vegan café, an ecological garden of seven hectares, and offer accommodation and courses in anything sustainable, such as building techniques, eco-farming, yoga, alternative medicine, sustainable energy, sustainable animal husbandry, linseed oil painting, water management, and tai chi. |

SP |

2006 |

Univ. |

72 |

|

Equine Excellence Invented, produces, and sells a heat isolator for water buckets for horses. The heat isolator prevents the horse’s water from freezing during the winter. Equine Excellence started as a Young Enterprise Business (UF), a high school course offered to students in Sweden. |

SP |

2018 |

Upper sec. |

24 |

|

Evergreen Addresses gender disparities and encourages women to embrace active roles as foresters. Offers chainsaw training courses exclusively for women. These courses equip women with the necessary skills and knowledge to pass the examination for obtaining a chainsaw license. |

SP |

1991 |

Univ. |

57 |

|

Green Meadow Rents out part of their farm to the municipality through a so-called ‘green care agreement’. People with disabilities visit the farm with their caregivers and care for the animals. The 365 hectares family farm has 100 beef cattle and some sheep. The wife oversees the animals and the care business, while her husband is employed outside the farm. |

SP |

1987 |

Secondary |

71 |

|

The Hat-maker Started by a master hatmaker and her husband, a jewellery designer. She creates upscale felt hats from rabbit and beaver fur. The couple exhibits their work at a Paris convention twice a year, through a flagship store, and through an online shop. |

Ltd. |

2008 |

Vocational |

43 |

|

Horse-Power Uses horses to transport timber and firewood from the forest and to perform carriage work, such as transporting tree branches, manure, and fence materials. The horses are also used for ploughing, covering potatoes in the field, sowing grain, mowing hay, and harvesting. |

SP |

2010 |

Secondary |

54 |

|

Innovation Advisor Operates as an intermediary between innovation support systems and rural entrepreneurs by helping entrepreneurs obtain access to innovation support systems. The Innovation Advisor provides business counselling, training, and networking events. They also network with national and regional actors in several innovation support systems. The centre is hosted by a rural municipality and employs two people. |

Muni-cipal project |

2016 |

Univ. |

61 |

|

MedTex Has developed advanced, research-based medical compression products in co-operation with a textile engineering research institute. The company currently employs three people, including the founder. |

Ltd. |

2011 |

Univ. |

42 |

|

Nordic Meadow Seeds Produces and sells Swedish meadow seed mixtures and seedlings. They cultivate about 100 different species of meadow plants, while some seeds are collected from the wild. Additionally, they conduct business with approximately ten contract growers located in various parts of Sweden. These contract growers grow local different species of meadow flowers. |

Ltd. |

2015 |

Univ. |

34 |

|

The Art Gallery Opened in an abandoned furniture factory and now houses art exhibitions on various themes, including wood art, textile art, the invisible work in the household, sustainable architecture, and sustainable consumption. The gallery features a vegan café, organizes cultural events, and collaborates with other arts and cultural institutions, both nationally and internationally. |

Non- profit |

1998 |

Univ. |

34 |

|

The Crop Alliance An organisation that produces sustainable food based on local relationships as an alternative to the globalised food production and distribution model. The organisation operates as a produce cooperative, uniting farmers who grow crops and vegetables. Units are sold to customers who receive a weekly delivery of fresh produce. |

Econ-omic coop. |

2014 |

Univ. |

44 |

|

The Driving School Started by a woman who changed the gender norms in the industry by, at first, employing only women driving instructors. This became a competitive advantage, as many students of either sex prefer female instructors, and it paved the way for women to become employed as driving instructors at other driving schools. The school employs twelve instructors across three communities and is growing. |

Ltd. |

2014 |

Vocational |

39 |

|

The Horsecloth Company Has invented a sustainable horsecloth (a blanket) with interchangeable parts for sports horses. The cloth is also equipped with a sensor that measures the horse’s temperature, thereby making it easier for the horse’s owner to regulate the amount of cover the horse needs. The company has recently started to sell its horsecloths and is currently expanding internationally. |

Ltd. |

2021 |

Univ. |

44 |

|

The Library Faced with the closure of the village library, a group of engaged readers suggested establishing a Civil Society Public Partnership (CSPP) between the municipality and fourteen local associations. A facility was provided, plus financing for expenses and new books. It is staffed by ten volunteers, all of whom are older women. The library has also become a ‘local living-room’ used by other associations. |

CSPP |

2019 |

Secondary |

78 |

|

The Revival Company When the local village store closed, a local woman formed a non-profit organisation owned by ten local associations, which, in turn, now owns the company that took over the store. Step by step, they also added a café, a library corner, an activity centre, RV parking, and a senior citizens’ home. Separate companies run these facilities. |

Ltd. + non-profit |

2018 |

Univ. |

60 |

|

Upcyclers Consists of a group of retired female volunteers, some with a background as tailors or public-school sewing teachers. They offer weekly workshops at the local library, where people can bring their old clothes and learn how to mend and upcycle them. They arrange upcycled fashion shows, ‘up-scale’ flea markets, and have participated in artisan exhibitions. |

Informal group |

2019 |

Univ. |

71 |

|

Verdant Haven Farm Turned a decommissioned state penitentiary into a fishing and activity farm with access to nature and several accommodations of very high quality. They strive to be ‘climate positive’ and want to contribute to a stable climate. They have set up innovative green projects on the farm, including a biochar system, green roofs, and an aquaponics system. |

SP |

2000 |

Vocational |

53 |

Apart from the Driving School, located in a community north of the geographic centre of Sweden, all participants are located in rural areas south of the geographic centre. The southernmost regions of Småland, Öland, and Skåne are overrepresented, with 16 participants. With the exception of the remote mountain areas in the north, this area does well in representing rural Sweden as a whole—it includes forests, agricultural land, lakes, a long coastline, a large, inhabited island, and even an archipelago. Forests cover 68 per cent of Sweden, and forestry is also the most common business activity in rural areas. This also holds true in the south. Approximately 20 per cent of the Swedish population resides in rural areas. However, most rural residents work in areas unrelated to agriculture, since agriculture employs only about 1.5 percent of the country’s total population [56].

5.2. Data Collection

Semi-structured interviews were conducted during the spring of 2024 at the business owners’ premises or, in five cases, online. The interview guide included questions about the women’s innovation pathways, their surrounding ecosystems, and their mainstreaming actions [57,58]. Questions of particular relevance for the present paper concerned the women’s perspectives of and interactions with policy. We asked (i) whether they had received any support from national or local policies or existing support systems and (ii) their opinions on such support. We also inquired how legislation had impacted their operations. The interviews consisted of guided conversations lasting one to two hours, and were audio recorded and subsequently transcribed. All interviews were conducted in accordance with the ethical guidelines established by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority, under approval Dnr 2023-02575-01. These guidelines allowed participants to withdraw from the study at any time without needing to provide a reason. Each participant signed a consent form regarding the audio recording of the participant’s responses, the anonymisation of data, the use of visuals and images, data storage, and data use.

5.3. Analysis

In the first step of the analysis, we coded the participants’ responses using the questions in the interview guide as a guideline [59]. We then transferred the coded information in a condensed form into a separate Excel file, covering the topics outlined in the interview guide. The Excel file also accommodated relevant information that was not specifically elicited during the interviews but was volunteered by the participants. We also noted references to illustrative quotes in the same file. The results of the first step of this analysis are reported in the FLIARA project [57] and are used as background material for the present paper. Table 3 provides an overview of the support that the participants have used. It may appear impressive, but it is worth noting that the typical contribution is temporary and relatively small.

Table 3. Support used.

|

Organization |

Forms of Public Support Used |

Bank Loans |

Help from an Industry Organization |

|---|---|---|---|

|

BerryBliss Orchards |

Project financing from LEADER. Skill building course from public school for artisan foods. |

||

|

EcoHarvest Academy |

Owned by the regional public administration. Project financing from public funds such as EU funds and Vinnova. |

yes |

|

|

EcoMoo Farm |

CAP annual farm subsidies. Project financing from the Swedish Environmental Protection Agency, the EU, and the Swedish Board of Agriculture. |

yes |

|

|

Eco Centre |

None. |

||

|

Equine Excellence |

Skill building through a public school, counselling through Almi. |

||

|

Evergreen |

Project financing from the Swedish Agency for Economic and Regional Growth. |

yes |

|

|

Green Meadow |

CAP annual farm subsidies. |

yes |

|

|

The Hatmaker |

Mentor from a science park, “consultancy checks” from the Region. |

||

|

HorsePower |

None. |

||

|

Innovation Advisor |

Project financing from LEADER, municipalities, and the Region. |

||

|

MedTex |

Product development funds from Vinnova and the Region. Technical and financial help from an incubator. |

yes |

|

|

Nordic Meadow Seeds |

Funds from The Swedish Board of Agriculture and Jobs and Society. Project funds from Almi and the Swedish Board of Agriculture. |

yes |

|

|

The Art Gallery |

State and regional grants for operating costs. |

||

|

The Crop Alliance |

Counselling from Coompanion. Project financing from LEADER. |

||

|

The Driving School |

None. |

yes |

|

|

The Horsecloth Co. |

Joined a business incubator, an innovation loan from Almi. |

yes |

|

|

The Library |

Annual small municipal grant for operating costs. |

||

|

The Revival Company |

Project money from Vinnova, the EU, the Rural Development Program, the Swedish Agency for Economic and Regional Growth. |

||

|

Upcyclers |

Free weekly use of the facility at the municipal library. |

||

|

Verdant Haven Farm |

Project financing from LEADER. Public skill building course. Took part in a network at Winnet, “consultancy checks” from the region |

For the purpose of the present paper, we conducted a second analytical step, specifically focusing on how the women experienced business support. We returned to the transcripts and marked every instance where the women mentioned something related to business support. We added all such mentions, verbatim, into a Word file. We then applied the structured thematic analysis method [60]. The analysis process involved repeated engagement with the interview material, where we coded new themes, combined codes, and reorganised them into the evolving aggregated themes [61,62]. The analysis resulted in twenty-three codes, eight first-order themes, and three aggregated themes (see Table 4).

Table 4. Thematization of the material. The degree of grey background color corresponds to Figure 1.

|

Codes |

First-Order Themes |

Aggregated Themes |

|---|---|---|

|

Technical bias |

Bias in funding opportunities |

|

|

Material bias |

||

|

Large business bias |

||

|

Motivation |

Unwillingness to apply |

|

|

Reluctant to scaling |

||

|

Evaluation criteria |

||

|

Bank loans |

Funding sources used |

|

|

Self-sufficiency |

||

|

Local funds |

||

|

Project money |

Ticking boxes |

|

|

Tweaking |

||

|

‘Woman box’ |

||

|

Business skills |

Networks and skill-building |

|

|

Expertise |

||

|

Commonalities |

||

|

Bottom-up |

||

|

Expanding economically |

Funds beyond a growth paradigm |

|

|

Imitating |

||

|

Public funders |

||

|

Business skills |

Business-related needs |

|

|

Beyond the start-up phase |

||

|

Small businesses |

Variation of organisation forms |

|

|

Organisational form |

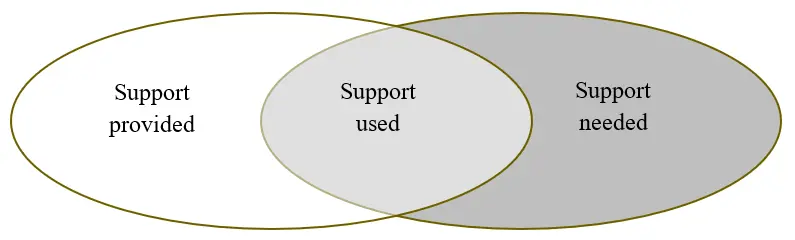

Three distinct ways of viewing the material emerged during our analysis. The first aggregated theme concerned how the entrepreneurs perceived the support provided. This may or may not coincide with the actual provision of support. Instead, this theme reflects the participants’ perception of support provision or lack thereof. The second aggregated theme concerned the participants’ perception of the support they actually used. The third aggregated theme concerned the kinds of support they said they needed. We present our findings accordingly: three sections discuss each aggregated theme, and in each of these sections, we discuss the associated first-order themes.

6. Findings

6.1. Perceptions of Support Provision

All interviewees had been in contact with different business support agencies in search of funding, courses, or other forms of assistance. As shown in Table 3, all but two did in fact receive some form of public assistance, but they still maintained that the system has little to offer them. A shared sentiment is that their businesses are often ineligible for continued funding or knowledge support due to their sector, size, business model, or the owner’s aspirations regarding the direction in which they wanted their business to develop. The feeling is one of being sidestepped in the system.

6.1.1. Theme: Bias in Support Opportunities

Generally, women entrepreneurs are critical of the prevailing business support system, as they find it biased towards businesses engaged in economic activities with growth potential. They also found that the existing support system overlooks small businesses as well as social, cultural, and environmental innovations that do not prioritise economic growth. This conclusion applies to the entrepreneurs’ perspectives on innovation funding, business incubators, and rural development funding, which they have either applied for or dismissed, based on an initial assessment.

Since support systems focus on material measures, some interviewees have learnt to work around the system, for example, by engaging in construction projects, even when such projects are not central to their primary business activity, in order to be eligible for rural development support. Alternatively, they may abstain from applying for support. The owner of Green Meadow, for instance, was unable to find support for her small-scale environmental initiative. She needed help with administration, not with employing people or building a stable.

The interviewees also saw support systems as having a technical bias. Entrepreneurs who had invested in and utilised technology found assistance and funding for product development quite easily from various sources, including Vinnova, business incubators, regional development funds, industry organisations, and research institutes. This was the case for five of the participants (EcoHarvest Academy, Verdant Haven Farm, EcoMoo Farm, MedTex, and the Horsecloth Company). MedTex financed seven years of product development through public investments from different sources:

[…] When we ran it as a research and development project, we received 100 percent financing. […] We received a large grant from Vinnova, which lasted several years.

However, when the business’s product development phase was complete, finding public financing for the production and marketing phase, these entrepreneurs felt abandoned by the support system. The owner of MedTex, for example, wished that funding for scaling an existing business was more readily available without the need for co-financing.

At the other end of the tech-driven business spectrum, we find HorsePower, a company that has made a conscious effort to ‘de-technify’ the forestry industry by offering horse-powered timber transportation. Finding funding for her business is difficult, and the owner feels she is expected to provide her services for free or very cheaply:

As soon as there is a horse in the picture, the attitude is: ‘Yes, but it is so cozy, and it is so idyllic’. [...] If you have a machine or a tractor, then everyone understands that it costs [to run this equipment].

Some of our interviewees explicitly reported that their farms and businesses were classified as too small to be eligible for funds from the national support systems. The owner of the Crop Alliance says:

Even though we contribute a lot to food production for our customers, we are too small to be able to apply for any support from the Swedish Board of Agriculture.

The support system is experienced as bureaucratic and geared towards large businesses. A large company can hire legal and economic experts to help them navigate the government’s requirements, but a start-up has neither the necessary skills nor the resources to do so. Problems with an overly bureaucratic system were also identified as an obstacle for companies that submitted yearly applications with the Common Agricultural Policy. Despite many years of discussions about simplifying the application process for farms, nothing has changed, reports the owner of Green Meadow.

6.1.2. Theme: Unwillingness to Apply for Support

As a result of the obstacles discussed in the previous section, we observed that half of the women entrepreneurs gave up on applying for continued support (both financial and knowledge), even when they desperately needed it. There exists a mismatch between the motivation of entrepreneurs and the issues that support systems focus on. Women entrepreneurs are confronted by a business support system that focuses on economic growth and scaling and is primarily interested in the start-up phase of a business. However, economic growth as the initial motivation for entrepreneurs to start a business did not appear in our interview material. Instead, the most common motivation behind the business, project, or idea was the individual woman entrepreneurs’ desire to improve rural lives or farming practices and to realise an idea, whether it be a new product, service, or organisational form.

Moreover, half of our interviewees were reluctant to commit to scaling their business. They wanted to maintain a manageable size for their business, illustrated by how the owner of Equine Excellence finds it too financially risky to expand her business:

The way I have it now, it’s manageable, and I can have this on Mom and Dad’s farm. But if I were to scale it up, I would have to find a warehouse, and then there would be a lot of extra costs that I don’t have right now. And then you need to make sure that you get coverage for it, and then the question is whether the demand is the same considering everything that is happening in the world, people have less money, and things are more expensive, and so on … it’s a pretty big gamble.

Others, such as the owners of Green Meadow and the Crop Alliance, choose not to pursue expansion, as growth could compromise core values such as social sustainability and independence from large-scale food producers. Since the interviewees are reluctant to commit to economic scaling, they find it challenging to find actors in the various business support systems who understand their needs. The evaluation criteria used by the support systems do not align with the entrepreneurs’ ideas behind their endeavours, and consequently, they do not apply for support.

The evaluation criteria referred to above frequently focus on ‘success’ in terms of economic growth. For EcoHarvest Academy, whose mission is ‘to spread knowledge’, success is difficult to quantify. People are interested in their testbeds, but it is unknown what this interest actually leads to. When a biogas plant is installed somewhere in Sweden, EcoHarvest Academy may have had something to do with it, but one can never be certain, says the project manager. Since success is difficult to quantify, the company that applies for support must modify its application proposal to comply with the evaluation criteria, or its application will be rejected. Alternatively, the business may choose not to apply for support. For the Eco Centre, modification to their application proposal is not an option:

What happens [then] is that you suddenly become dependent on the system because you have to shape your activity based on the requirements that are set for you to receive support.

This entrepreneur chooses not to engage with existing business support systems to stay independent, as their requirements conflict with her vision of a society not driven by constant economic growth.

6.2. Perceptions of the Support Used

Whilst all of the interviewees have been in touch with at least one actor in the business support system, their experience is that they are all rather specialised. Consequently, finding a suitable form of support for a particular need can be challenging. The entrepreneurs also reported encountering support designed for one stage of business development, which proved inapplicable to other stages of their business development. Some women have been able to navigate the complex support system, while others have felt excluded and have stepped away from it.

6.2.1. Theme: Funding Sources Used

Our interviewees started their businesses with very little money. They used bootstrapping, personal savings, or funds from family and friends to gradually develop their business ventures. In cases where external funding was used, it was typically local, sourced from various local funding organisations, or from organisations such as LEADER, the Swedish Agricultural Agency, the region, or other state-owned and regional initiatives. However, for those entrepreneurs who had sought external funding, we observed ‘grant-seeking fatigue’. The owner of Nordic Meadow Seeds said, “I feel a bit done with seeking support”.

Consider the owner of Evergreen, who built her business entirely through projects. “I jumped on different projects when I got the chance”. However, this approach is not sustainable, she says. Her next step is to create a sustainable business model that does not exclusively rely on project money:

I’ve been thinking a lot about this with projects, and I love projects, but [...] when the project is over, it is over. I know. Then there is no more money. And that day, yikes, it’s up to you. And it’s a bit dangerous to live just on projects. You need something more.

Four of the 20 women entrepreneurs used bank loans for large business investments, such as purchasing property (Green Meadow), stocking their vehicle inventory (the Driving School), or acquiring an existing business (Nordic Meadow Seeds). Bank loans require collateral, a reasonable return on investment, and, in some cases, good personal contact with the bank. Some businesses, like EcoMoo Farm, satisfy these criteria, whilst others do not. The owner of HorsePower, for example, claimed that limited profitability was a barrier to her securing a bank loan. Even those with collateral may encounter obstacles—the owner of Green Meadow reported that securing a bank loan has become increasingly difficult due to rising farm prices.

Those who cannot, or will not, rely on bank loans or project money, such as the Hatmaker and Eco Centre, use their business profits to develop their businesses, or one part of the business finances another one:

All the money we earned in the farm shop, we invested in the cultivation [side of the business] because I don’t generate that much money there. It’s in the farm shop where the money is found and in the ice cream and chocolate [we sell]. But if I hadn’t been developing all the time, I could have made a big profit every year. (Owner, BerryBliss Orchards)

6.2.2. Theme: Ticking Boxes to Fulfil Application Criteria

To meet the evaluation criteria and become eligible for support from the business support system, the women often adjust their business, project, or idea, or downplay certain aspects of their business mission. Non-profit organisations, in particular, depend heavily on project money. For example, the Revival Company uses whatever project money is available. One might say that they vacuum the market for project money. The founder of this business claims she could never have achieved what she has without this form of support:

I have mainly applied for investment support through the Rural Development Programme, but also EU money, the Swedish Agency for Economic and Regional Growth, and Vinnova. So, we are probably up to 30–32 million [Swedish crowns, SEK] that we have received for buildings.

To address the material bias in support evaluation systems, women innovators are often compelled to make adjustments to their business ideas. For example, consider the Revival Company, which engaged in construction projects solely to ensure the company was eligible for rural development support. At the same time, this business owner had to downplay other areas of her business mission. Consequently, ticking the right boxes in the application form sometimes entailed satisfying obligations that she had not foreseen.

Expertise and ingenuity are essential for successfully navigating the complexities of the current business support system. Notwithstanding that, the system sometimes shapes entrepreneurial practices in ways that the entrepreneur did not intend. In some cases, for the better. For example, BerryBliss Orchards had to demonstrate its collaboration with other businesses to be eligible for support from LEADER. Consequently, the woman entrepreneur asked local producers if they wished to sell their products in her farm shop. Seven local producers responded positively, and at the time of the interview, the farm shop sold products from forty-five local producers, enjoying a very close business collaboration with each of them.

Five women entrepreneurs say they have been able to leverage their identity as women to secure funding and knowledge. The owner of the Horsecloth Company informed us that she had received significant assistance from support organisations because she is a woman. These organisations were keen to report that they have provided support to a woman entrepreneur in their performance reports and other statistics. The owner of Equine Excellence stated that being a young woman has also helped her secure funding. The entrepreneur from the Revival Company claims that she ‘stands out’ and receives a great deal of attention as a female construction project leader. She plans to exploit this attention in future applications.

However, the women entrepreneurs did not use support systems specifically designed for women entrepreneurs. The owner of Green Meadow considered applying for women-specific funding but did not meet the eligibility criteria. Moreover, at the time of the interviews, most women-only programmes in Sweden had been discontinued.

6.2.3. Theme: Networks and Skill Building

Some policy initiatives include support for networks or courses created by support actors for various target groups, for example, young entrepreneurs, women, specific industries, or specific localities. Those entrepreneurs who are part of a business network reported that their network membership has inspired them in their business endeavours and enabled their cooperation with other businesses. For Evergreen, joining a forestry network served as the owner’s starting point for her engagement with chainsaw licensing courses.

The networks to which entrepreneurs belong are typically specialised rather than general. They are limited to including individuals and organisations that are deemed necessary for the promotion of the specific business innovation. The women entrepreneurs reported that they network with participants, suppliers, resource providers, trade organisations, clients, and so on, but they do not frequently network with broader or more general networks.

Female-only networks were previously used by Verdant Haven Farm and HorsePower, but these networks have since been discontinued. Some businesses, like Horsecloth Company and MedTex, benefited from incubators—gaining funding, knowledge, and networks. Equine Excellence began as a Junior Achievement project in school, providing early experience in running a business and inspiring further development.

Learning new skills and engaging in personal development were essential for the women we interviewed. Most of them sought out associations they could learn from by attending seminars, courses, or events. The content of these skill-building activities was linked to specific business-related activities, such as bookkeeping and marketing, but it was also related to the particular innovations of their businesses, for example, permaculture.

When courses do not suffice, the entrepreneurs bring in external expertise to their businesses, including business advisors or technical experts. At least two entrepreneurs have paid for these services with ‘consultancy checks’ offered by the county councils. For the owner of BerryBliss Orchards, her accountant has become a crucial business mentor. He has assisted her from the start of her business, helping with her taxes, employment contracts, and other business-related matters. The owner of Nordic Meadow Seeds hired someone to help with a business takeover. The two tech companies represented in our data sample have received valuable help from university-based technical experts.

6.3. Support Needed

To meet the needs of women entrepreneurs, we argue that a bottom-up perspective or an end-user perspective is necessary. The women whom we interviewed wish that the support system could deliver financial support that views growth as something that transcends economic parameters. They call for a system that (i) focuses more on the provision of knowledge and skills that women need and (ii) includes a variety of organisational and business forms.

6.3.1. Theme: The Need for Financial Support Not Conditional on Growth

Only a few of the women’s businesses align with the standard economic model that business advisors or public funding typically look for:

There are different types of innovation systems, different networks. But I think that they may not help much if you follow a vision that is not economic growth. (Owner, Eco Centre)

Locating funds that fit their needs is not a simple task, and instead, most women entrepreneurs rely on their earnings, which may slow down or hamper their business development. In some cases, the entrepreneurs are just able to keep their businesses afloat. The owner of Crop Alliance even stepped back from running the association, but says that if the cooperative were to become financially viable and less risky, she would consider running it again. The owner of HorsePower would like to see someone in the business support system who actually understands her business idea, “You have to be able to show ‘development potential’, if you know what I mean?”

Another aspect of not fitting in with the standard growth model expected by current support systems is represented by the interviewees who encourage others to imitate their business ideas. For example, the owners of EcoHarvest Academy, Evergreen, the Crop Alliance, the Innovation Advisor, the Revival Company, the Hatmaker, and Eco Centre all wish to see their business idea spread, and they are happy if other people “copy” their work. Imitation by others is even built into their business models:

We will show [other entrepreneurs] different small possibilities on how to do it, where you can get inspiration on what reality can look like. (Owner, Eco Centre)

The owner of EcoHarvest Academy claimed that: “Things spread like ripples on the water, and I still think that this biogas plant is somehow the heart”. Even though other businesses might be seen as competitors, such collaborative arrangements are seen as a way to attract new customers to already established businesses.

However, since the women entrepreneurs often experience difficulties in finding funding for such collaborative business models, imitation (as described above) is limited and frequently based on goodwill. The Innovation Advisor, for example, wants to spread her business model to other locations but not her own operation per se. She wants to ‘train the trainers’. For this to happen, other municipalities and support organisations must appreciate the value of her business model and finance a local advisor. Non-profit organisations, such as Upcyclers, would like their model to be adopted by other municipalities. They have made efforts in this direction, but with limited success. Upcyclers have abandoned their search for public support as they saw no way that any existing support organisation could help them, given the sector’s primary focus on economic development.

Nevertheless, public funding or support that is open to evaluate a business’s performance in terms other than its economic performance still constitutes a cornerstone for the non-profit organisations or the social enterprises included in our data sample. These could not survive without public funding. The Revival Company is a prime example. The Library and Upcyclers enjoy access to municipal facilities that are crucial for their operations, and the Art Gallery balances public funds and private sponsorships to continue its business development. For-profit organisations with business goals that transcend economic performance also rely on public support. BerryBliss Orchards has received funds from LEADER, for example.

However, it is worth noting that businesses that follow the standard economic business development model have also encountered difficulties in securing public funding. The Horsecloth Company, for instance, reported that its product is too niche to be eligible for general public funding and has thus, unsuccessfully, tried to attract a private investor. MedTex and the Driving School have also turned to the private market in search of funding. MedTex was subsequently acquired by a larger company, while the Driving School continues to experience difficulties in raising the capital necessary to franchise its business model.

6.3.2. Theme: The Need for Specific Business-Related Support

A majority of the interviewees are quite self-sufficient in terms of their relevant business knowledge. Some of the women entrepreneurs come from a professional background and have acquired the necessary business skills on their own initiative. Others have a family background in entrepreneurship, for example, the owner of the Driving School, for whom business ownership comes naturally:

My father is also self-employed. It’s probably in the genes maybe. Yeah, actually, my father’s entire family. We have had the carpentry shop for several generations.

Some entrepreneurs reported that they lack specific business-related skills and that more could be done to support them in their quest for new knowledge. For instance, the owner of HorsePower expressed interest in attending training programmes for marketing, and the owner of Equine Excellence, the youngest female entrepreneur in our dataset, remarked that she needs to further develop her business skills.

The interviewees also argued that public support should recognise different phases of business development. Start-up funding and assistance were generally more readily available than funding or assistance for sustaining, running, maintaining, and scaling a business. The Revival Company, for example, manages several projects, all of which are in different phases of development. In certain cases, this company has found itself funding older projects with money reserved for newer projects:

For projects, you sometimes must spend money from your own pocket for a very long time, and this can be a great strain on our operations. An activity that does not go well can actually jeopardise a project, even if funds are reserved for the project. If you have an electricity bill of SEK 46,000 to pay, you pay it with whatever money is available. So, it has been challenging.

Upcyclers and the Library, two organisations founded by senior women entrepreneurs, required minimal support in the initial stages of the business. These women possessed all the necessary knowledge and skills for their operations. However, they had to negotiate with their municipalities for the facilities they needed—skills they had to learn or outsource, as reported by the Library’s founder: “Then this guy [...] at Coompanion [...]. He came into this as well and was tasked to negotiate and write the agreement.”

6.3.3. Theme: The Need for Support for a Variety of Organisational Forms

As discussed earlier, the interviewees found the small size of their businesses to be a liability when applying for support. Our interviewees wished that small and large companies could operate in separate leagues, with fewer, more straightforward rules and lower fees imposed on small businesses. HorsePower reached out to the municipality’s business advisor to assist with her business’s development, but was rejected:

Then my turnover was not big enough. So, I’m too small. […] I’m not very good at marketing my vision and what it can generate in terms of money, employees, and such.

Consider also BerryBliss Orchards, where the government tax office initially rejected the business owner’s application to establish a sole proprietorship business, arguing that there was no market for her products in the rural area. Meanwhile, the demand for her products was so large that her bank refused to allow her to continue to receive customer payments into her personal bank account. She could not issue invoices without a proper business being registered, even though other businesses were interested in buying her products. She felt trapped by a Catch-22.

In contrast, we can provide a positive example where consideration was given to a small business, as seen in the case of the Crop Alliance. The authorities’ regulations for commercial production kitchens were simplified after the Crop Alliance started. ‘Micro-producers’ no longer needed a full-fledged and approved kitchen for their operations but could use their home kitchen, within certain limits. This change is viewed as a positive development by entrepreneurs, enabling smaller organisations to develop new products.

In addition to the business’s size, its organisational form is also relevant to support systems. Different needs drive the entrepreneurial activities that take place in civil society organisations than those of traditional companies. Whilst companies may enjoy a future income stream from their operations, civil society organisations depend on donations, various funds, and operational and voluntary support. In addition to problems related to securing funding, the interviewees also mentioned issues with the succession of volunteers, operational support, volunteer fatigue, and difficulties in mastering digital systems. The Library would not have been established without a municipal public actor who is very engaged in the project and helped them devise a Civil Society Public Partnership. Furthermore, they would not have been able to begin their operations without help from the IT department at the municipal library.

7. Discussion

In short, a common sentiment that is present in our data is that rural women’s businesses are often ineligible for funding or knowledge support due to the business sector, the business model, or the owner’s aspirations for the business. Whilst all of the interviewees have been in touch with at least one actor in the business support system, the shared experience the entrepreneurs have is that these actors are all rather specialised. Consequently, finding a suitable fit for a particular business need is challenging for these entrepreneurs. Gender disparities remain evident in funding and knowledge transfer [11,12]. We also find that business support is designed for a specific stage in a business’s development (usually the start-up stage) and does not apply to other stages. As such, the available support is often considered overly specific and requires ticking too many boxes. This is an activity that some of the women entrepreneurs in our study were unable or reluctant to engage in. Nevertheless, as any entrepreneur, every woman entrepreneur needs knowledge, facilities, money, networks, and skills when they start their business and continue to run it. However, the nature and scope of these needs varied widely. We discuss the findings of this study in terms of the model presented in Figure 1, which illustrates how the forms of public support provided, as perceived by the interviewees, intersect only slightly with the forms of support needed by women innovators in rural areas.

Figure 1 reveals that there exists a significant mismatch between what policymakers think might benefit rural business development versus the forms of support that our interviewees (according to them) need to develop and sustain their ventures. The support that has been provided, and continues to be provided, simply misses the mark. The reasons behind this mismatch are discussed in the following sections.

First, support systems are primarily built on the premise of economic performance and economic growth and the assumption that women constitute an untapped resource for economic growth [41,42]. However, our interviewees were reluctant to commit to scaling their businesses. They wanted to maintain a manageable size for their business, or they operated non-profit, cultural, or social enterprises. Innovation funding, business incubators, and rural development funding sources often overlook social, cultural, and environmental innovations that do not prioritise economic growth [8,9]. This is the case, even though small businesses and businesses in these sectors are essential to rural viability and development [48]. Moreover, we find that business scaling by imitation, i.e., support that grows the total economy but not necessarily the individual recipient of support, is also ignored.

Second, systems often have a technical or material bias. As such, existing support measures from national actors, including the Swedish Board of Agriculture and Vinnova, focus on businesses with growth potential, often in the agricultural or technical domains and in typically male-dominated fields that are irrelevant for most of our interviewees [3]. This bias is made manifest at different stages of an application process: either women entrepreneurs are not aware of the available forms of support, or they refrain from applying for the support because of how it is framed, or their application for support is rejected when the application is assessed based on evaluation criteria and gender bias.

Third, support systems are perceived to be onerously bureaucratic and informed by a silo mentality, i.e., one system does not communicate with another. This makes it challenging for entrepreneurs to overview the support systems and their potential benefits, resulting in missed opportunities. A reliance on short-term projects makes long-term sustainability unfeasible. In this context, projects are also viewed as inflexible, overly specific, requiring the ticking of too many boxes, and sometimes necessitating radical adjustments to the entrepreneur’s business proposal or business mission.

Given that women-owned enterprises constitute an essential sector of the rural economy by providing employment for themselves and their staff, and offering a range of services [63], there is good reason to improve the provision of support to these entrepreneurs. Women often own businesses in the service sector, for example, in the area of the provision of care, retail activities, tourism, and events, or they provide social or cultural services, without which, rural life would be untenable [48].

7.1 Recommendations

Our recommendations for improvement would ideally be a business support system that (i) is not primarily structured around the premises of economic performance and economic growth, (ii) does not have a technical or material bias, and (iii) is neither bureaucratic nor informed by a silo mentality. Some concrete recommendations that would move a business support system towards this ideal are presented below.

First, support system actors should consider that imitation by others constitutes a common and well-intentioned approach to scaling a business. While such an approach might not benefit the original entrepreneur financially, they receive other benefits and rewards that they value just as much. Furthermore, a business that scales in this way still benefits the total economy [2]. Consequently, we propose that business advisors and financiers broaden their perspectives regarding scaling beyond an individual’s economic growth. Possessing this knowledge would benefit women in both rural and urban areas, as well as many small business owners who are men.

Second, more money should be allocated to announcing support initiatives that extend beyond large high-tech firms (particularly those located in urban areas). This includes, but is not limited to, support aimed at non-profit, cultural, or social enterprises. These operations are crucial for the viability and development of rural areas. More general announcements of support would counteract the prevailing silo mentality and enable more ventures to demonstrate their eligibility for funding. A very simple way to draw interest to an announcement of support is to make it less bureaucratic, i.e., easier to apply for. We do not call for less rigour in the eligibility assessment process, but instead, more innovation in how announcements and applications are designed.

Third, since the provision of public funds is instrumental to the funding schemes of the women entrepreneurs we interviewed, we consider it crucial that this provision be continued. Public funds are essential because they offer opportunities in terms of value expansion, societal benefit, and sustainability in ways that differ from those provided by commercial funders. However, a shift in how taxpayer money is distributed for business development should occur along the lines of our second recommendation (see above). To further rural sustainability, we recommend moving away from short-term project funding towards a model of long-term operating grants.

Fourth, politicians should increase their efforts regarding gender mainstreaming. Every Swedish policy is supposed to be gender mainstreamed [64]. However, for the most part, policy agencies assume they have satisfied this requirement if they can show that no direct gender discrimination exists in their policy. Their attitude is that if women do not apply for support, it is their own fault. However, this perspective overlooks the structural obstacles discussed in this study. To begin with, agencies should report gender-disaggregated statistics, as well as urban/rural breakdowns for the number of applications and approved applications. If inequalities are identified, the reasons behind such inequalities should be addressed and rectified.

7.2 Limitations

The study is highly context specific as it focuses on a particular country’s business support system, namely Sweden, a country characterised by a historically strong welfare state [23]. While neoliberal ideas have privileged market solutions and spread during the last decades, there is a persistent view that the state can and should initiate change and development [26]. The findings may be applicable to the other Nordic countries that have similar welfare states [9], but may not be directly transferable to other countries. Moreover, the study is a bottom-up examination of women’s views on the support system, rather than a program evaluation. It can therefore not be used to assess the effectiveness of any program. It is also worth noting that the study did not include ethnic minorities or the indigenous Sami population in northern Sweden. These groups may face additional obstacles and should be included in future research.

7.3 Future Research Directions

Almost all our interviewees utilized some form of public support for funding, advisory services, competence development, technical support, or networking, yet were nevertheless critical of the support system. This implies that future program evaluations may need to broaden their focus. Program evaluations tend to measure effectiveness in terms of uptake, delivery, or results, given the aim of the program, which typically includes economic performance. However, our study showed that while rural women entrepreneurs engaged in enterprises designed for rural sustainability, they did not prioritize economic growth. On the contrary, some individuals have explicitly worked towards a sustainable, degrowth society that prioritizes environmental and social goals. We think they may be onto something very important, which studies with a narrow economic focus tend to overlook. This invites not only studies on how programs can be more meaningfully assessed but also studies on the role of rural women’s entrepreneurship in creating a sustainable future for the planet. Particularly intriguing is our finding that women encourage others to imitate their ideas without any necessary economic benefit for themselves. This runs counter to any standard theory of how entrepreneurs operate and, in fact, questions a host of theories about entrepreneurial motivation or economic growth. We invite future research to explore further and theorize this phenomenon.

8. Conclusions

This study has highlighted the presence of persistent gendered mismatches within the Swedish rural business support system. We have revealed a disconnect between policy intentions and the lived realities of rural women entrepreneurs. Whilst these women play a vital role in sustaining and enriching rural economies, current support structures frequently fail to recognise or accommodate their diverse needs and aspirations.

Our findings underscore that prevailing business support initiatives are too narrowly framed, focusing primarily on aspirations for economic growth, technical innovation, and individual economic scalability. We note that these criteria often exclude rural women-led operations, which often prioritise social, cultural, or environmental values. Moreover, the bureaucratic and fragmented nature of the current support system, coupled with a lack of communication between actors and a reliance on short-term projects, further marginalises these women entrepreneurs.

To foster a more inclusive and effective support landscape, we advocate for a paradigm shift, one that values alternative growth models (such as imitation), broadens eligibility criteria to include the non-profit sector, and simplifies access to funding. Public funding, in particular, should be restructured to support long-term sustainability rather than short-term outputs. By embracing these changes, the business support system can better align itself with the realities of rural entrepreneurship and contribute more meaningfully to rural development and gender equity.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the help from the interviewing team: Mathias Karlsson, Viktorija Kalonaityte, Malin Tillmar, and Annie Roos, all at Linnaeus University who conducted the interviews. Roos and Ahl are solely responsible for the analysis in the current paper.

Author Contributions

Both authors were involved in the idea stage, draft stage, analysis and final writing of the text. As disclosed in the acknowledgement Annie Roos was involved in the data gathering stage together with a team of four researchers.

Ethics Statement

This study was approved by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority (approval no. 2023-02575-01) on 22 August 2023. All participants provided written informed consent prior to participating.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Research data are not shared due to ethical reasons laid out by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority.

Funding

This work was funded by the European Union—grant number 101084234.

Declaration of Competing Interest