Sustainable Recycling Mechanisms for Waste Cooking Oil in China’s Third-Tier Cities: Evidence from Restaurant Practices

Received: 03 July 2025 Revised: 18 September 2025 Accepted: 27 October 2025 Published: 06 November 2025

© 2025 The authors. This is an open access article under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

1. Background

As China pursues its ambitious carbon peaking by 2030 and carbon neutrality by 2060 goals [1], green development has become a cornerstone of its national strategy. Within this context, Waste Cooking Oil (WCO) stands at the intersection of environmental sustainability, food safety, and renewable energy. Improper disposal of WCO not only contaminates soil and water but can also re-enter the food chain as hazardous “gutter oil”. However, when properly recycled, WCO represents a valuable resource for biodiesel production, contributing to circular economy development and reducing reliance on fossil fuels [2,3]. Despite its strategic significance, China’s WCO management remains fragmented and uneven, with significant policy and infrastructural gaps, particularly in second- and third-tier cities. Bridging this disconnect is crucial to achieving national sustainability goals, highlighting the urgent need for targeted research into the drivers, barriers, and policy frameworks that shape WCO recycling behaviors in underdeveloped urban contexts [4,5].

In 1980, the total amount of municipal solid waste in Chinese cities was approximately 31.3 million tons [6], but by 2011, this figure had surged to 179.36 million tons [7], and is projected to reach 480 million tons by 2030 [8]. A significant proportion of this waste is food-related, a concern that has become critical for environmental management. Globally, around 130 million tons of food are wasted annually, with kitchen waste accounting for 50% to 60% of this total [9]. As the world’s largest producer and consumer of food, China generates an immense volume of food waste each year. This not only creates substantial pressure on waste management systems but also exacerbates resource inefficiency, energy consumption, and environmental degradation [10,11]. In China, food waste is particularly critical and calls for innovative solutions to reduce waste generation while promoting resource recovery. The recycling of WCO represents a potential solution to address food waste challenges, alleviate environmental pressure, and contribute to sustainable energy systems [12,13].

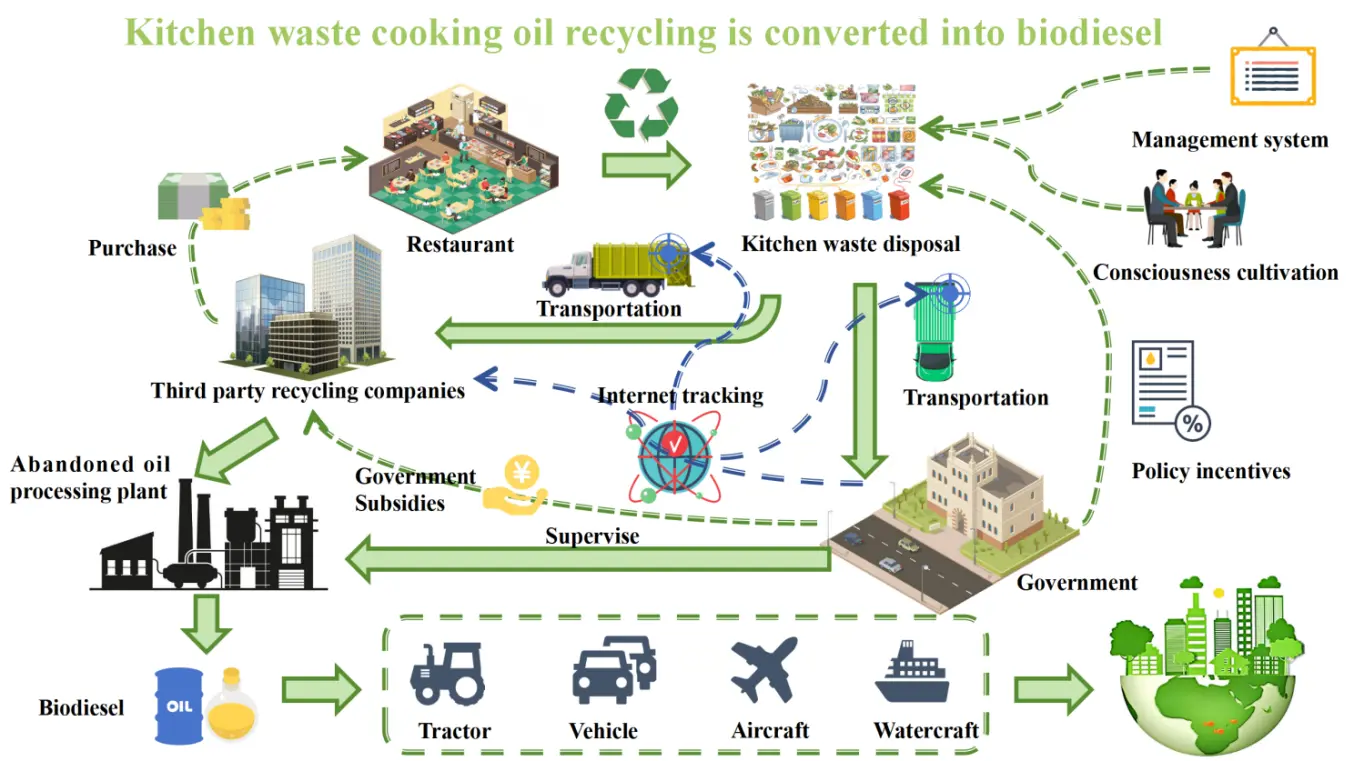

WCO is a key component of urban food waste, and its recycling plays a pivotal role in mitigating environmental pollution and promoting the circular economy. WCO is a significant environmental pollutant, containing harmful substances that can contaminate water sources, soil, and ecosystems if not properly treated [13]. However, recycling WCO provides an excellent opportunity to address these environmental issues while also producing biodiesel, a clean, renewable alternative to fossil fuels. Biodiesel derived from waste oils is increasingly recognized as a sustainable solution for reducing greenhouse gas emissions and lowering dependence on traditional petroleum-based fuels [14,15]. The efficient recycling of WCO not only reduces waste but also contributes to the energy transition by providing a renewable energy source that helps meet growing energy demands while simultaneously lowering carbon emissions. The use of WCO for biodiesel production has the potential to mitigate fossil fuel dependency, promote energy diversification, and create new economic opportunities [5,16]. Moreover, this recycling process aligns with China’s green development strategy by reducing waste generation, improving resource efficiency, and promoting sustainable energy production. As WCO recycling technology continues to advance and as policy frameworks strengthen, the full potential of this resource will be increasingly realized, contributing significantly to both environmental sustainability and economic development.

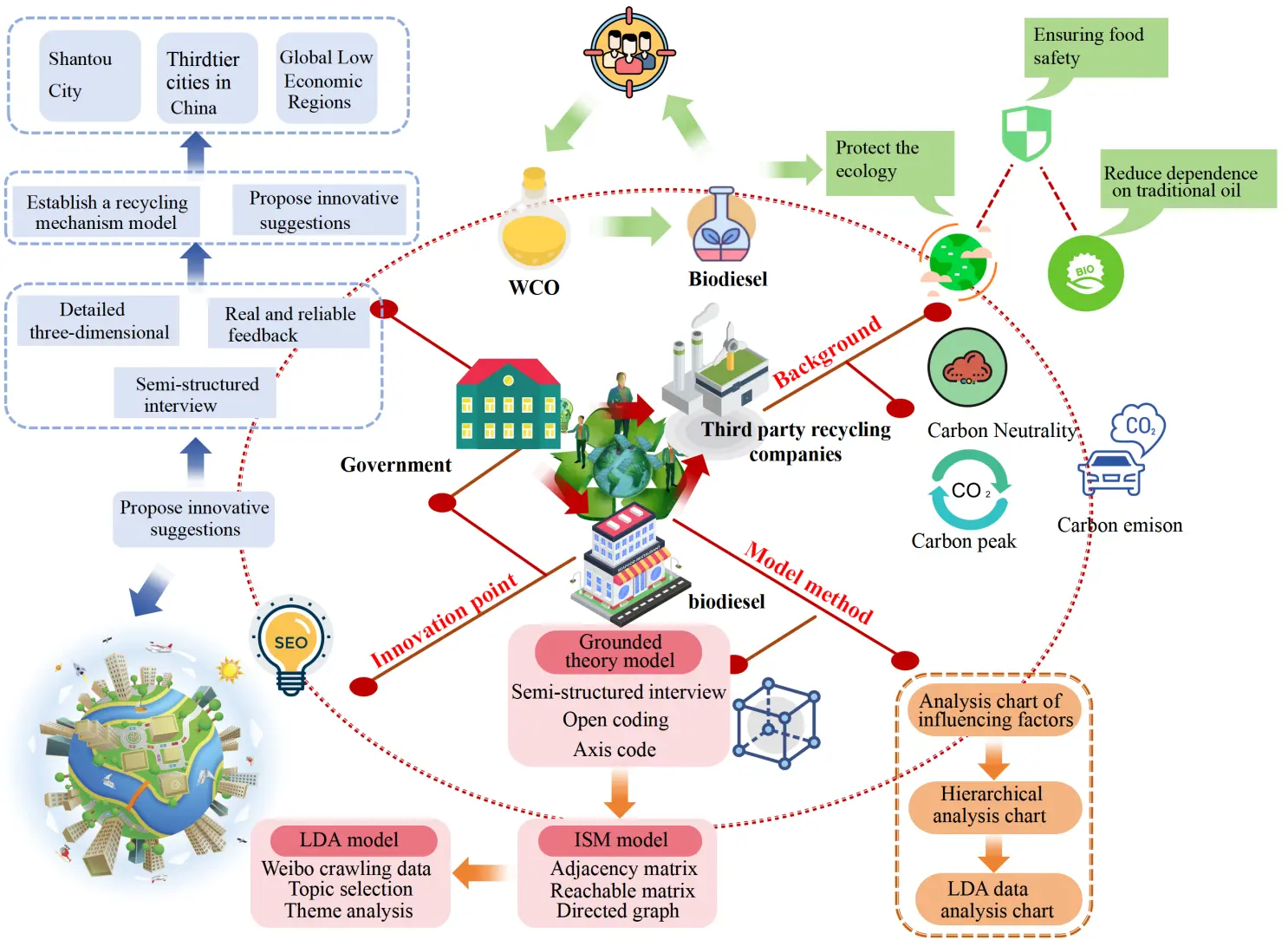

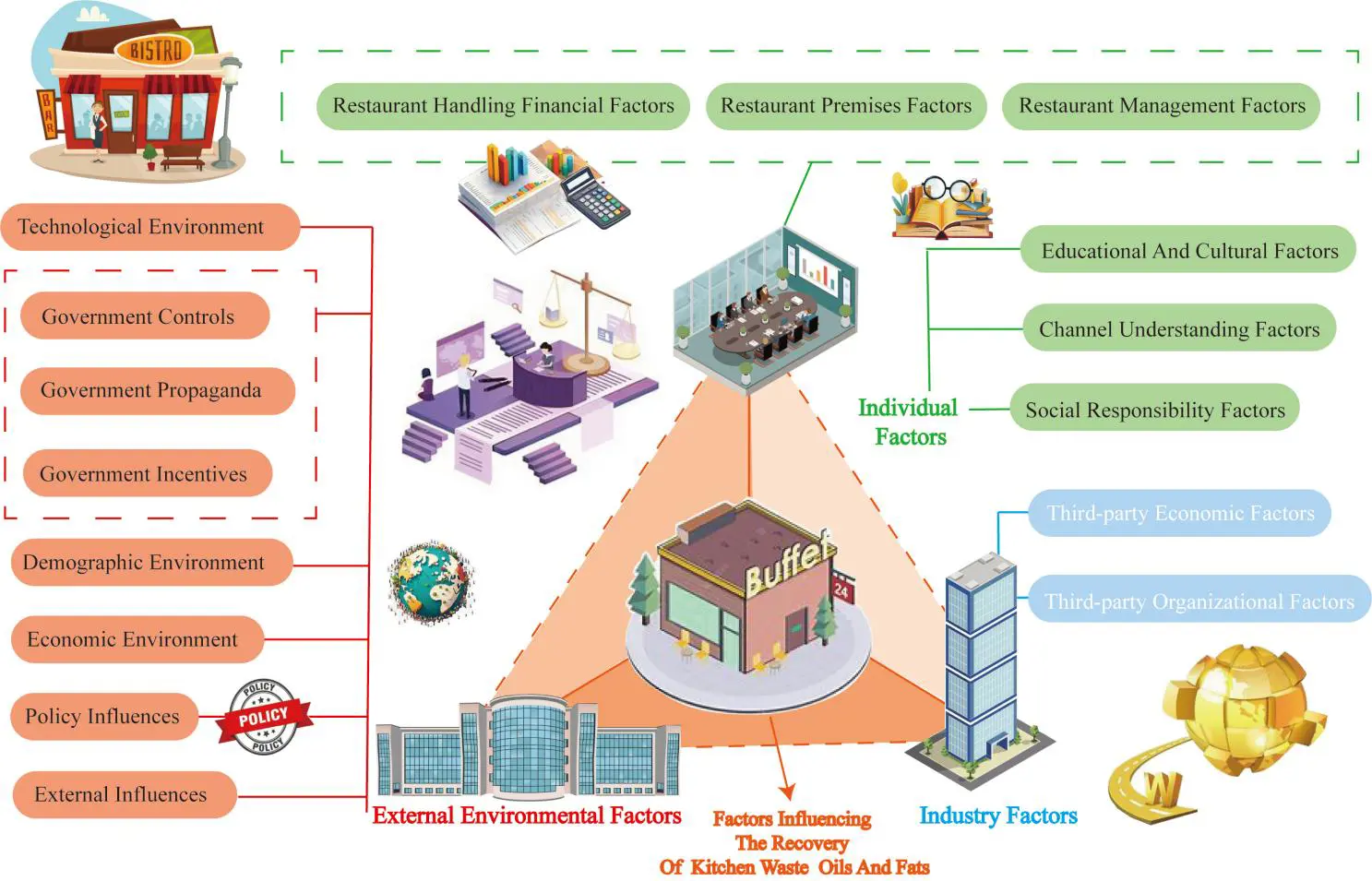

Despite the substantial potential of WCO recycling, significant challenges remain in China’s current WCO management system. While some first-tier cities, such as Shanghai and Beijing, have implemented relevant policies and established WCO recycling frameworks with some success, the recycling infrastructure in second- and third-tier cities remains underdeveloped. In many regions, illegal WCO recycling and improper usage continue to be prevalent, posing serious risks to food safety and environmental health. For example, incidents such as the 2023 hotpot oil recycling case in Mianzhu and the 2024 smuggling case in Danyang involving 40 kg of WCO highlight critical gaps in the management and regulation of WCO [17,18]. These issues underscore the need for a more robust, standardized WCO recycling framework across the country, particularly in less developed urban areas. Inadequate regulatory enforcement, insufficient public awareness, and limited technological innovation in WCO recycling hinder the effectiveness of current waste management systems. To address these challenges, there is an urgent need for comprehensive policies that not only strengthen local regulations and advance recycling technologies but also reduce the costs of WCO collection and processing. Public education and awareness campaigns are equally crucial in fostering greater participation from the restaurant industry and local communities. By strengthening government regulations, advancing recycling technologies, and raising awareness, China can establish a more effective WCO recycling system, contributing to its broader goals of environmental sustainability and low-carbon development [13,19]. The following is the research idea for this paper (Figure 1).

The root of these issues lies in ineffective policy transfer from first-tier to third-tier cities, compounded by insufficient regulatory enforcement, a lack of technological innovation in recycling, and public ignorance regarding the importance of Waste Cooking Oil (WCO) recycling. As a result, the existing waste management systems fail to meet the unique structural demands of third-tier cities. This research gap constitutes the core problem that this study seeks to address. While progress has been made in larger cities, there is a significant lack of focus on the specific barriers faced by smaller cities, such as cultural, economic, and infrastructural differences. These factors hinder the successful implementation of WCO recycling systems and obstruct the broader achievement of China’s environmental protection and low-carbon development goals.

This study aims to fill the research gap by focusing on the micro-, meso-, and macro-level factors influencing restaurant operators’ decisions to participate in Waste Cooking Oil (WCO) recycling in third-tier cities. The research will use grounded theory to identify and categorize the key behavioral drivers of WCO recycling willingness at different levels. Furthermore, Interpretive Structural Modeling (ISM) will be employed to model the hierarchical relationships and interdependencies among these factors, revealing both foundational drivers and surface-level outcomes. By applying Latent Dirichlet Allocation [20], the study will also analyze textual data to uncover patterns in restaurant operators’ decision-making processes. Additionally, this research aims to develop a multi-stakeholder collaborative framework that provides actionable, context-specific policy recommendations for improving WCO management in third-tier cities and other developing regions. Through efficient WCO recovery, primarily via biodiesel conversion, the study aims to reduce resource waste, minimize environmental pollution, and promote the sustainable use of natural resources. This process is critical for environmental protection, food safety, public health, and reducing dependence on fossil fuels, thereby supporting China’s broader sustainable development goals.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Current Status of Waste Cooking Oil (WCO) Recycling Research: International and Domestic Perspectives

Most research on the recycling of kitchen WCO and grease has focused on countries and regions outside of China [21,22,23,24,25,26]. Despite the numerous potential uses of WCO, public awareness of its recycling possibilities remains limited. In some foreign cities, this low level of awareness suggests a need for enhanced education and public outreach efforts [23]. In China, research on WCO recycling has primarily focused on household waste, especially in first- and second-tier cities, including Lanzhou in Gansu Province [27], Hong Kong [28,29,30], Shanghai [31,32,33], Beijing [34,35], Shandong [36], and Suzhou [37,38,39]. In Lanzhou, Lang et al. (2020) used an awareness assessment model to examine whether restaurant owners’ attitudes and behaviors were influenced by their awareness of food waste recycling. In contrast, Mak et al. (2018)[28] conducted a quantitative analysis in Hong Kong, examining interactions among significant variables affecting food waste recycling behaviors within relevant industries and determining the importance of these variables. Similarly, Jin (2017)[32] analyzed both domestic and international practices related to the recycling and utilization of food waste, WCO, and grease in Shanghai, and proposed institutional designs and policy measures. Liu et al. (2018) [34] conducted an in-depth analysis of the kitchen waste recycling management system in Beijing, systematically exploring the underlying issues and proposing innovative strategies to address them. In Shandong Province, Zheng et al. (2020) examined the role of third-party recycling companies and proposed two management models based on a global biodiesel recovery framework [36]. In Jiangsu Province, Zhang et al. (2017) explored the reasons behind performance disparities among waste cooking oil-to-energy companies in China, finding that government interventions—such as information disclosure, fees, and penalty mechanisms—significantly influence company performance. Based on a comparison of two pilot companies in Changzhou and Suzhou, they recommended strengthening R&D support and optimizing policy structures to enhance overall industry efficiency [38]. While these studies offer valuable insights into WCO recycling in first-tier cities, they often assume well-established policies and infrastructure, overlooking the unique challenges third-tier cities face in resource allocation, policy enforcement, and infrastructure development. Therefore, this study seeks to address this gap by investigating WCO recycling pathways tailored to the specific conditions of resource-constrained and infrastructure-deficient third-tier cities, and by providing actionable policy recommendations.

2.2. Research Progress on Digital Technologies in Waste Cooking Oil (WCO) Management

With the accelerating evolution of information technologies, digital tools are becoming deeply embedded in waste cooking oil (WCO) management systems—transforming technical infrastructure and governance models through real-time sensing, traceability, and resource recovery. A growing body of international evidence highlights the diversity of digital applications. For example, Gong et al. (2024) applied the Technology-Organization-Environment (TOE) framework to evaluate Z Company’s Southern Europe project in the UK, identifying seven distinct WCO recycling models and demonstrating blockchain’s role in enhancing regulatory transparency and alignment [40]. In Portugal, the SWAN system developed by Gomes et al. (2024) utilized IoT-enabled bins and edge computing to significantly improve household-level collection efficiency [41]. Similarly, Nigeria has piloted a hybrid governance model integrating IoT, AI-based classification, and blockchain logistics to facilitate multi-stakeholder coordination [42]. Digital tools are also increasingly embedded in waste-to-resource initiatives—such as biofuel conversion, pyrolysis, and e-waste metal recovery [43]. In plastics recycling, blockchain combined with smart contracts and decentralized applications (DApps) has enabled the creation of low-carbon, transparent global circulation systems [44], while also improving traceability, system reliability, and institutional interoperability [45,46].

Within the Chinese context, research has begun to examine the multifaceted impacts of digitalization on environmental governance. At the firm level, studies reveal a U-shaped relationship between digital investment and environmental performance, with technological innovation acting as a key mediating mechanism and executive hometown identity serving as a positive moderator [47]. Institutionally, the 2015 Environmental Protection Law (NEL) has been shown to exert a gradual “short-term negative—long-term positive” effect on the financial performance of heavily polluting firms, particularly through financing and R&D pathways—and with pronounced effects on small enterprises [48]. At the macro level, quasi-natural experiments based on the “Broadband China” initiative indicate that digital economy development significantly improves air quality, primarily via mechanisms such as green innovation, industrial upgrading, and green finance [49]. However, despite the significant potential demonstrated by digital tools across various sectors, the widespread adoption and effective implementation of these technologies still face numerous challenges, particularly in resource-constrained regions. Existing studies primarily focus on successful cases of technology application, but often lack a comprehensive discussion of the obstacles encountered during implementation, such as funding shortages, weak infrastructure, and the digital divide between regions. This study aims to establish a sustainable pathway for Waste Cooking Oil (WCO) recycling in third-tier cities, addressing key challenges such as resource limitations, inadequate infrastructure, and weak policy enforcement, while fostering innovative practices in WCO recycling in these cities.

2.3. Urban Hierarchies and the Challenges Faced by Third-Tier Cities

Compared with first- and second-tier cities, third-tier cities in China face a unique set of structural and institutional challenges in managing waste cooking oil (WCO) recycling. Restaurant operators in these regions often lack formal education and professional training, relying primarily on experiential knowledge. This gap in technical understanding diminishes their ability to adopt standardized recycling practices and weakens their motivation to engage with formalized recycling systems. Additionally, restaurants in third-tier cities are typically small-scale operations that generate limited volumes of WCO and grease. These establishments often have minimal infrastructure—such as basic storage containers and rudimentary filtration equipment—which significantly reduces collection efficiency and raises unit costs [50]. On the institutional side, fragmented governance creates an additional barrier to effective regulation. While existing laws clearly delineate departmental responsibilities, overlapping mandates and poor coordination among agencies frequently result in weak enforcement, particularly at the subnational level [51,52]. Goh et al. [53] identify inadequate government oversight, high treatment costs, and insufficient subsidies as key factors contributing to the persistent mismanagement of WCO across various sectors [54]. At the household level, the situation is equally problematic. Recovery rates remain alarmingly low—typically below 6%—due to limited public awareness and participation. Moreover, the small-scale, dispersed nature of WCO generation among households creates logistical inefficiencies, wherein the resource input often outweighs the value of the oil recovered, leading to low overall system yields [54,55]. However, existing research predominantly focuses on the experiences and lessons learned from first- and second-tier cities, neglecting to explore the unique challenges and implementation difficulties faced by third-tier cities within their specific socio-economic contexts. While these cities encounter numerous obstacles in building recycling systems, current policy frameworks and technological support often assume that these issues can be easily resolved in third-tier cities, overlooking the realities of weak infrastructure and fragmented resources. Such research and policy recommendations, disconnected from the practical realities, limit the accurate assessment and improvement of WCO recycling systems in third-tier cities.

2.4. Integrative and Emerging Methodologies in WCO Recycling Research

Although research on the environmental and economic significance of WCO recycling has been growing, studies on recycling willingness have predominantly employed quantitative methods [27,28], while significant gaps remain in the application of qualitative approaches. At the forefront of contemporary academic research, grounded theory has been effectively applied across various fields, including healthcare [56,57], tourism [58], and learning experiences [59]. Its distinct advantage lies in constructing theoretical frameworks from empirical data in a bottom-up manner, making it particularly suitable for this analysis. In studies examining the factors influencing product purchases [60], the oil and gas industry [61], and issues within the food industry [62], scholars have utilized ISM as an explanatory framework. Despite the increasing emphasis on the environmental and economic significance of food waste, grease recycling, and reuse, a noteworthy observation is that grounded theory and ISM models have rarely been applied to this critical issue. Furthermore, a thorough examination of current academic frontiers reveals a high degree of compatibility between ISM models and grounded theory [63,64]. The integration of these two approaches can establish a comprehensive analytical framework for WCO and grease recovery, thereby enhancing the theoretical depth and breadth of the research and improving the capacity to analyze and resolve practical issues. The potential application of Dirichlet allocation in thematic modeling [36], which has gained traction in the field of topic modeling, can also infer implicit topic structures within document collections through statistical means [65].

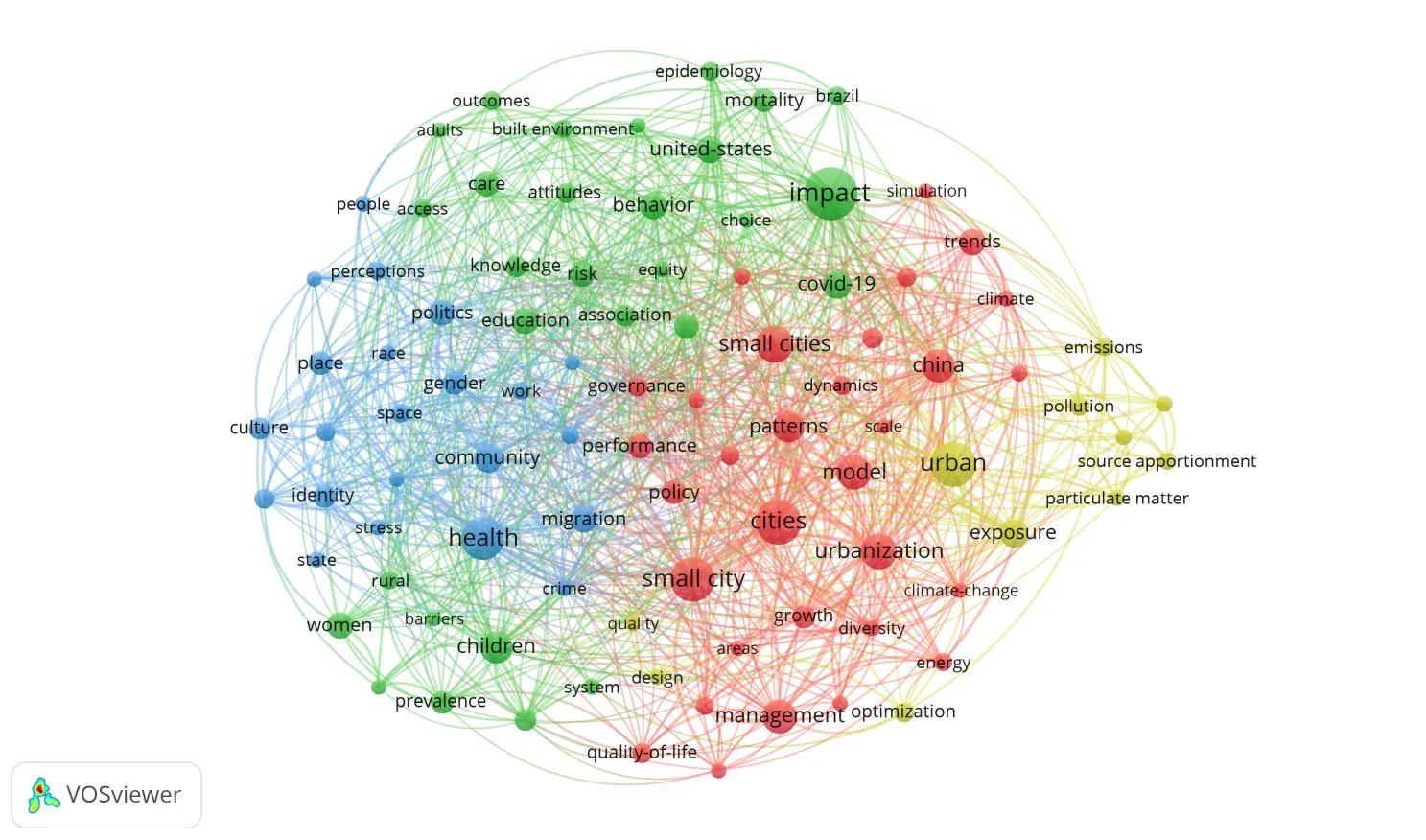

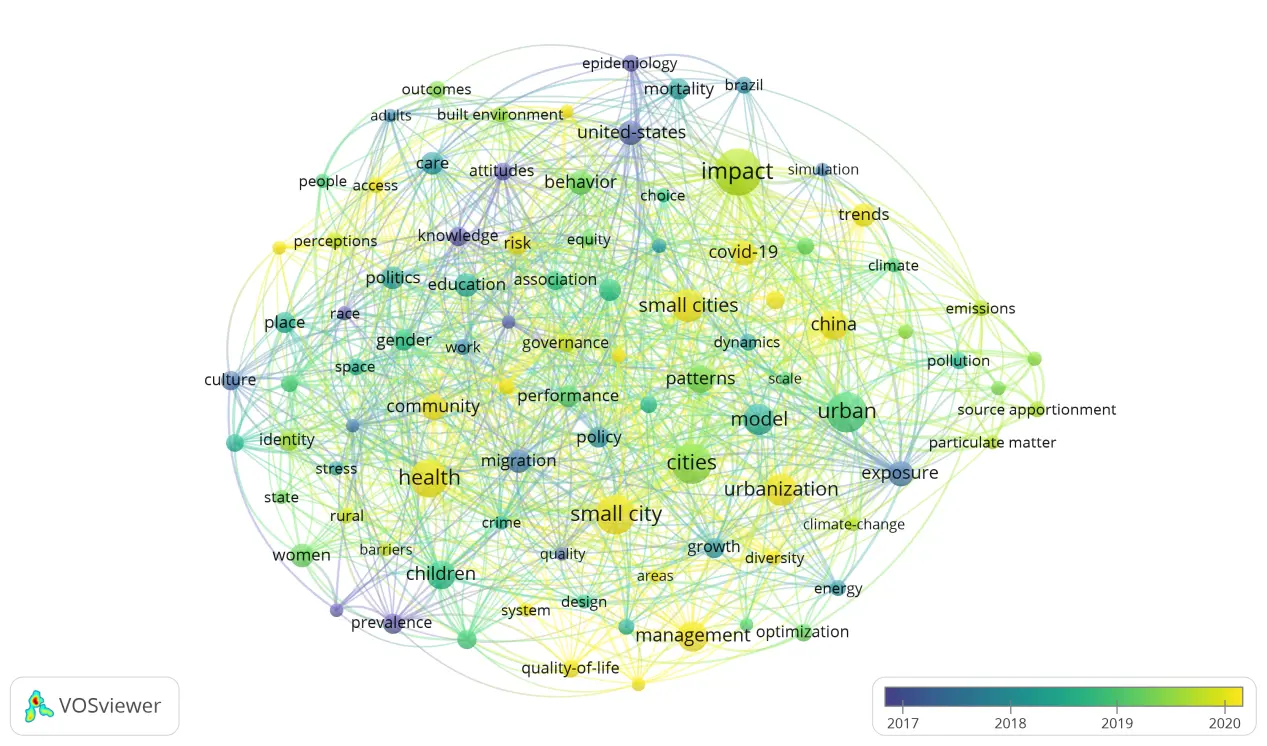

2.5. Bibliometric Co-Occurrence and Evolution Analysis Based on VOSviewer

To enhance the systematicity and objectivity of the literature review, this study employs VOSviewer [66], a bibliometric visualization tool (version 1.6.20) developed by the Centre for Science and Technology Studies at Leiden University, the Netherlands (https://www.vosviewer.com, accessed on 26 May 2025). VOSviewer allows for the visualization of complex data by analyzing keyword co-occurrence, author collaboration, and citation patterns, thereby revealing the structural relationships and evolution of research themes [67]. Using the Web of Science Core Collection as the data source, a total of 1027 relevant articles were retrieved. For the keyword co-occurrence analysis, the minimum occurrence threshold was set at 10, yielding 96 high-frequency keywords and identifying 44 countries. The search focused on core themes such as “waste cooking oil”, “recycling behavior”, “small city”, and “qualitative research”, and was expanded using relevant synonyms to ensure comprehensive and representative coverage. In these studies, qualitative methods, particularly grounded theory used to understand behavioral mechanisms in small cities, remain marginal and represent a critical methodological gap that urgently needs to be addressed. To bridge this gap, this paper first reviews the existing literature and fills this methodological void by introducing an integrated framework that combines semi-structured interviews, grounded theory, and ISM.

The co-occurrence clustering map (Figure 2) reveals three major thematic clusters emerging in the current literature: small-city governance, public behavioral mechanisms, and systems optimization. The colors in the network represent different thematic groups: blue for health-related topics, red for urbanization and city themes, green for environmental impact and policy, and yellow for pollution and climate-related topics. High-frequency keywords such as “small city”, “urbanization”, “governance”, “community”, and “behavior” suggest a growing academic interest in the intersection of resource recovery and institutional implementation in non-metropolitan and underdeveloped areas. In particular, terms like “recycling willingness” and “environmental behavior” highlight the increasing importance of public attitudes, intentions, and cognitive factors in waste management research. In contrast, keywords related to qualitative methods—such as “semi-structured interview”, “grounded theory”, and “case study”—remain peripheral, indicating that such approaches have yet to gain widespread adoption in this field and represent an important gap to be addressed. To respond to this methodological gap, the present study adopts a semi-structured interview approach combined with grounded theory and ISM. This integrative framework enables a more nuanced identification of the key factors influencing waste cooking oil recycling behavior among restaurant operators. In doing so, the study not only introduces methodological innovation but also contributes conceptually by addressing theoretical shortcomings in the domain of resource governance in small-city contexts.

The temporal evolution map (Figure 3) further indicates that keywords such as “small city”, “health”, “management”, and “COVID-19” have gained significant prominence since 2020. This shift reflects a growing research emphasis on public health and environmental governance in smaller urban centers, particularly in the context of the pandemic. Simultaneously, practice-oriented terms such as “waste separation behavior” and “grease recycling” have moved closer to the research core, suggesting that the field of resource recovery is gradually transitioning from macro-level governance to micro-level behavioral mechanisms. Against this backdrop, the present study focuses on the recycling behavior of restaurant operators in China’s third-tier cities. Investigating their willingness to recycle WCO is not only crucial for advancing renewable energy development and contributing to carbon reduction goals, but also essential for safeguarding urban public health by preventing the reentry of illicit “gutter oil” into the food chain. By exploring behavioral motivations and institutional barriers, this research aims to offer targeted policy recommendations to enhance resource utilization efficiency and strengthen grassroots environmental governance.

Research on WCO and grease recovery carries substantial theoretical and policy significance. In China, most existing studies remain focused on technological pathways for waste oil treatment, while limited attention has been given to the public’s willingness to recycle, particularly among restaurant operators. At the same time, the growing academic focus on keywords such as “small cities”, “health”, and “environmental governance” reflects a rising awareness of the critical role that non-core urban areas play in the intersection of resource recovery and institutional implementation. Within the broader context of public health and sustainable governance, research on small cities is gaining increasing relevance. In response to this shift, the present study investigates the recycling behavior of restaurant operators in China’s third-tier cities. It is the first to apply grounded theory to this topic, filling an important theoretical gap concerning micro-level behavioral mechanisms. Moreover, the study introduces a novel methodological framework that integrates ISM and Latent Dirichlet Allocation [20] to combine qualitative insight, structural analysis, and text mining. This approach offers a more systematic understanding of the drivers and institutional constraints shaping recycling practices in low-tier urban contexts and provides both methodological innovation and practical policy implications.

In summary, the existing literature reveals a fragmented research field focused on Waste Cooking Oil (WCO) recycling, primarily concentrating on first- and second-tier cities. However, these studies often emphasize the recycling mechanisms of mature urban systems, neglecting the application and challenges of digital governance and urban hierarchies in developing countries, particularly in third-tier cities. While digital technologies have shown promise across various sectors, there is a lack of in-depth research on how these technologies can be effectively leveraged to promote WCO recycling in third-tier cities, where resources are constrained and infrastructure is underdeveloped. Furthermore, studies on WCO behavior in third-tier cities predominantly rely on quantitative methods, with limited qualitative analysis on the micro-level factors, particularly those influencing practitioner decision-making. Therefore, this study fills a gap in existing research by combining qualitative behavioral studies and structural analysis within the context of third-tier cities, linking the findings from digital governance and urban hierarchy studies. It proposes an innovative WCO recycling pathway and offers practical policy recommendations for third-tier cities facing resource limitations and weak infrastructure.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Collection

Third-tier cities in China are classified based on development level, economic strength, population size, and geographic location. While these cities have an industrial base, they differ significantly from first-tier cities like Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou in terms of their industrial structure, economic growth rate, and quality [68,69]. Although third-tier cities are widely distributed across various provinces and regions and often have larger populations, their economic development lags behind that of first-tier cities.

Third-tier cities in China generally possess a strong culinary culture and a solid demographic foundation, which are accompanied by a significant amount of catering waste, particularly WCO. These cities face considerable challenges in solid waste management, especially concerning the WCO generated by the food service industry. The recycling and utilization of WCO not only addresses environmental concerns but also involves energy recovery and the circular economy, making it a critical area of research.

In this context, Shantou City exemplifies a typical third-tier city. It is located in eastern Guangdong Province, China, and spans geographic coordinates from 116°14′ to 117°19′ east longitude and 23°02′ to 23°38′ north latitude. As of late 2023, the city’s resident population had reached 5,557,500. Recognized as a special economic zone, Shantou City is distinguished by its unique geographical position, rich historical and cultural heritage, and vibrant culinary culture, all of which foster tourism development. Its advantageous coastline and harbor have resulted in a long-standing history of trade and commerce, with a robust commercial and cultural atmosphere. The city has grown from its status as a “century-old trading port” by enhancing its role in international trade through high-quality development strategies and strengthening economic ties with Southeast Asia to earn the title “Hometown of Overseas Chinese” [70]. The recent emergence of large-scale commercial complexes has contributed to the creation of a modern business district and offers significant opportunities for local economic growth, particularly in the catering sector. Since 2003, Shantou City has established itself as “the hometown of Chaozhou cuisine in China”, gaining recognition as a “National Gourmet Landmark City” by the China Culinary Association [71]. Its diverse gastronomic culture, featuring various unique snacks and traditional dishes, attracts many food enthusiasts. According to the Shantou City Statistics Bureau’s economic report for the first quarter of 2024, contact consumption has surged, particularly in the contexts of accommodation and catering, with industry turnover increasing by 20.8% year-on-year.

Given Shantou City’s large population and thriving catering market, the city produces significant amounts of catering waste, particularly KC and grease. This phenomenon is closely linked to the city’s size and its well-established gastronomic industry. For these reasons, Shantou City, Guangdong, is selected as the focal third-tier city for this article.

This study conducted interviews with 20 restaurant operators to assess their awareness of WCO recycling processes. To ensure the representativeness and diversity of the sample, participants were required to meet four criteria. First, all participants had to be actively engaged in the restaurant industry. Second, the sample included restaurants of various sizes: mobile street vendors, small-sized establishments (under 150 m2), medium-sized (150–500 m2), large (500–3000 m2), and extra-large (over 3000 m2), thereby capturing the operational differences in waste generation and management. Third, the restaurants were distributed across all six administrative districts of Shantou—Jinping, Longhu, Chenghai, Haojiang, Chaoyang, and Chaonan—ensuring broad geographic coverage. Fourth, the sample encompassed a diverse range of high oil-yielding restaurant types, including hot pot, fried chicken, and fast food outlets.

Although the total number of interviewees was limited to 20, this sample size meets the methodological requirements of grounded theory. Traditional qualitative research practices typically recommend a sample size of 5 to 30 participants per group, whereas more recent evidence-based approaches advocate flexible, context-sensitive determination of sample size [72]. Grounded theory, in particular, emphasizes the principle of theoretical saturation—where data collection continues until no new concepts or themes emerge—rather than statistical representativeness. To verify theoretical saturation, this study conducted an additional 10 in-depth interviews for recoding and engaged a second researcher to recode the original 20 interviews for cross-validation independently. The analysis revealed no emergence of new core categories or influencing factors, indicating that theoretical saturation had been achieved. Therefore, the sample size is deemed sufficient to support subsequent inductive analysis and theory building.

3.2. Research Methods

3.2.1. Grounded Theory Model: Three Levels of Coding

Social Situational Interviews (SSIs) are widely used by scholars as a key tool for exploring individual attitudes and intentions [73,74,75]. While SSIs are highly effective as standalone instruments in qualitative research, they also play a crucial role in mixed-methods studies by enhancing both the depth and scope of data collection and analysis, thereby enriching the overall research outcomes. Grounded theory, as a qualitative research methodology, has been effectively applied across diverse fields. For instance, constructivist grounded theory has been employed to examine the deeper connections between individual psychological well-being and external factors, revealing a more nuanced dynamic between the two [76]. Through researcher-participant collaboration, participants’ narrative experiences are transformed into meaningful elements, which are then integrated to develop grounded theoretical models based on thorough data analysis.

This study was conducted in Shantou City, Guangdong Province, where restaurant operators were selected through random sampling to ensure the reliability and rigor of the findings. Initially, participants completed a questionnaire assessing their awareness of WCO recycling practices, after which they were invited to participate in in-depth interviews. Furthermore, comprehensive interviews were conducted with waste segregation management personnel in the Shantou community, providing valuable insights into the practical challenges of WCO recycling in the region.

By integrating the grounded theory framework with data gathered from in-depth interviews, the study offers a comprehensive analysis of restaurant operators’ attitudes and behaviors regarding WCO and grease recycling. The goal was to develop a novel model of waste grease recycling awareness and behavior that is contextually relevant to the unique geographical and cultural characteristics of Shantou City. The validity and reliability of the study were further strengthened through the use of a triangulation strategy, which ensured data complementarity and robustness by integrating and cross-validating information from multiple sources. This approach formed a robust evidence base, gathering both primary and secondary data from diverse sources, enabling mutual corroboration and enhancing the consistency of the conclusions drawn.

3.2.2. Explanatory Structural Models—ISM Models

ISM has been widely applied in academia, industry, and research to identify barriers, challenges, and critical drivers across various disciplines [77,78,79]. Its usefulness has been demonstrated in multiple research domains, highlighting its versatility in addressing complex problems [80]. ISM use is widespread in business research [81]. The ISM model uses an intuitive “node-directed edge” framework to construct a “directed network graph”, aiming to effectively map and translate the structure of a complex system into a computer-aided format. This is achieved by breaking down the system into multiple subsystems (or constituent elements) through matrix operations. By decomposing the complex system, the architecture can be transformed, with the assistance of computational aids, into a multilevel hierarchical structural model. Concurrently, the ISM model exhibits high compatibility with the grounded theory model. In this paper, the ISM model was applied to analyze the intricate structure and dynamic interrelationships among the factors influencing the recycling of WCO and grease. This method not only assessed the appropriateness of system component selection but also investigated the cumulative impacts of the elements and their interactions on the overall system performance.

3.2.3. Latent Dirichlet Allocation Model

The LDA model has emerged as a powerful tool for text mining and topic modeling. It has been widely adopted in a growing body of literature for extracting latent thematic structures from large-scale textual datasets [82,83,84]. Utilizing this model [85], identified and forecasted trends in research topics pertaining to China’s energy. Building on this foundation, the Latent Dirichlet Allocation model [86] was selected as the primary analytical framework for this article to explore public concern and interest regarding the recycling of WCO and grease in China. Integration of the topic evolution analysis model with the LDA algorithm enabled us to capture and examine dynamic shifts in the topic content and its impact over time, using actual blog data to provide a robust quantitative method for identifying the underlying structure of textual data.

The LDA model identified key terms and thematic trends related to food waste grease recycling, revealing shifts in public concerns and the motivations driving these changes. Furthermore, it helped to uncover public attitudes and behavioral trends regarding food waste grease recycling over various periods. This insight provided policymakers with valuable support in formulating more effective management strategies and regulatory interventions.

3.3. Research Hypotheses and Theoretical Reasoning

In line with the overall research objectives of this study, the hypotheses have been reformulated to better align with the macro-level framework established through grounded theory and ISM modeling. These hypotheses are not standalone but are presented as integral components of the research design, which aims to build a comprehensive model of factors influencing WCO recycling in third-tier cities. The specific hypotheses for this study are as follows:

Hypothesis 1 (H1). Government financial incentives significantly increase restaurant operators’ willingness to participate in WCO recycling.

Hypothesis 2 (H2). Higher educational attainment among restaurant operators is positively associated with the adoption of standardized WCO recycling practices.

Hypothesis 3 (H3). Greater trust in third-party recycling organizations increases the likelihood of actual engagement in WCO recycling activities.

These hypotheses will be examined using the grounded theory framework to identify the behavioral drivers, and ISM to model the hierarchical relationships among these drivers. The ultimate aim is to construct a unified model of WCO recycling that not only integrates these specific hypotheses but also provides actionable insights into how these factors interact within the broader socio-economic and operational context of third-tier cities.

4. Research Results

This section presents the results in three parts. First, we utilized grounded theory to develop a data-driven model of influencing factors, identifying multiple core categories through open and axial coding. This model forms a multi-level theoretical framework explaining the determinants of restaurant operators’ willingness to recycle waste cooking oil (WCO). Second, we applied the Interpretive Structural Modeling (ISM) approach to analyze and visualize the relationships among these factors, revealing the key layers and dependencies influencing WCO recycling. Finally, we tested three key hypotheses to validate specific causal pathways within this integrated model, aiming to provide a theoretical foundation for practical applications and policy formulation.

The findings show that only a minority of respondents were familiar with existing recycling practices. Specifically, only 3 participants reported being aware of WCO recycling mechanisms, and another 3 recognized food waste recycling initiatives. In terms of recycling attitudes, 2 respondents expressed clear reluctance to participate, 2 were neutral or conditionally supportive, while the remaining 16 displayed a generally positive or supportive stance (Table 1). These results highlight a considerable opportunity to raise awareness and promote greater participation in WCO recycling by emphasizing both its necessity and practical feasibility.

Table 1. Statistics of basic information of interview subjects.

|

Statistical Term |

Categorization |

Quorum |

Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

|

sex |

male |

12 |

60% |

|

women |

8 |

40% |

|

|

age |

21–30 |

6 |

30% |

|

31–40 |

6 |

30% |

|

|

41–50 |

6 |

30% |

|

|

51–60 |

2 |

10% |

|

|

establishment |

shopkeeper |

14 |

70% |

|

shop assistant |

6 |

30% |

|

|

Restaurant size |

Mobile restaurants |

2 |

10% |

|

small restaurants |

13 |

65% |

|

|

medium-sized restaurants |

3 |

15% |

|

|

large-scale restaurant |

1 |

5% |

|

|

supersized restaurants |

1 |

5% |

|

|

educational attainment |

elementary school |

5 |

25% |

|

junior high school |

4 |

20% |

|

|

secondary schools |

3 |

15% |

|

|

universities |

8 |

40% |

|

|

usual |

2 |

10% |

|

|

unwilling |

2 |

10% |

4.1. Grounded Theory Modeling Results

In this section, we present the core findings from the interviews with restaurant operators. The following table (Table 2) presents the key results regarding restaurant operators’ awareness of Waste Cooking Oil (WCO) recycling and their willingness to participate in recycling efforts.

Table 2. Key findings on WCO awareness and recycling willingness.

|

Have you ever heard of recycling WCO? |

yes |

3 |

15% |

|

no |

17 |

85% |

|

|

Are you working on WCO now? |

yes |

2 |

10% |

|

no |

18 |

90% |

|

|

Willingness to carry out WCO recycling |

willing |

16 |

80% |

|

usual |

2 |

10% |

|

|

unwilling |

2 |

10% |

After presenting these key findings, we then explore the factors that influence restaurant operators’ recycling behavior in more detail. The following sections discuss the social, economic, and technical factors identified through the grounded theory approach.

Open coding is a qualitative research analysis method that involves the initial meticulous parsing and labeling of each utterance and a key fragment of raw data [87]. This step is followed by aggregating and integrating these labels for data categorization and generalization. In this research, we extracted significant information from the interview transcripts by word-by-word reading and defining and labeling each utterance. We identified 77 valid concepts through in-depth theoretical analysis, which were then synthesized into 16 broader categories (Table 3). Each “A” item (e.g., A1, A2, A3, etc.) represents a specific concept identified from interview transcripts or raw data through the process of open coding. Each “B” item (e.g., B1, B2, B3, etc.) denotes a higher-level category or theme, generated by aggregating, comparing, and synthesizing multiple related “A” concepts. This reflects the process of conceptual aggregation in grounded theory, known as the axial coding phase.

Table 3. Open coding process.

|

Area |

Conceptual |

|

|---|---|---|

|

B1 |

Policy Impact Factors |

A1 Rural Revitalisation |

|

B2 |

Government control factors |

A2 Prohibition of pig feeding A3 Cooperation with shopping centres A4 Restaurant electrical appliances A5 Restaurant shop hygiene A6 Food safety issues |

|

B3 |

Government Advocacy Factor |

A7 little publicity A8 no WCO and grease involved |

|

B4 |

Government incentives |

A9 Compensation A10 Small role A11 No system in place A12 Equipment taking up space A13 Providing equipment easier to handle |

|

B5 |

Economic factors |

A14 small places A15 underdeveloped |

|

B6 |

Demographic factors |

A16 Mostly residential population, no foreigners A17 More elderly people |

|

B7 |

Technical factors |

A18 Cannot pump the oil A19 Did not make a point of collecting it A20 Trouble A21 It is good to utilize it A22 Too difficult to implement A23 Rubbish site A24 Very confusing |

|

B8 |

External influences |

A25 Few people do nowadays A26 Different qualities A27 Sensitive topics |

|

B9 |

Third-party economic factors |

A28 Charge by the month A29 Charge by the pound |

|

B10 |

Third-party organizational factors |

A30 Half-monthly A31 Once a week A32 Fixed time every night A33 No contract A34 Specialised recycling A35 Door-to-door recycling A36 Contracted A37 Sanitation worker recycling A38 No contract |

|

B11 |

Restaurants to deal with financial factors |

A39 Freight costs A40 Cleaning costs A41 Equipment costs A42 Willingness to sell |

|

B12 |

Restaurant Venue Factors |

A43 Mosquitoes and flies are very common A44 Strict requirements for the shop A45 Hygiene has to be good A46 Uncleanness affects the shop A47 No place to install equipment A48 Taking up space |

|

B13 |

Restaurant Management Factors |

A49 Once a day A50 Once in the morning, once in the evening A51 No regular rota A52 Bale together and throw away A53 Separate wet and dry A54 Empty down the drain A55 Separate the waste A56 Feed the pigs A57 Empty down the gutter A58 Install a filter A59 Empty the bin A60 Prepare the oil drums |

|

B14 |

Educational and cultural factors |

A61 Never read a book A62 Uneducated A63 Did not pay much attention A64 Did not understand, not sure |

|

B15 |

Social responsibility factor |

A65 Distrust A66 Black-centred oil, gutter oil (illegally processed waste cooking oil) A67 Need for company to show relevant proof A68 Responsible A69 Psychological burden A70 Would rather dump than sell A71 Comfort and peace of mind in eating A72 Health issues |

|

B16 |

Channel Understanding Factors |

A73 does not know A74 does not want to care A75 motor oil A76 soap A77 feeds pigs |

Axial coding is a crucial step in qualitative data analysis to construct a network of intrinsic connections among the coded items [88]. This process involves exploring and clarifying the essential relationships between identified categories and refining the interpretive framework by outlining the hierarchical structure, causal relationships, and temporal order among categories and subcategories [89]. In this research, the concepts identified during the open coding phase were reconnected, summarized, and integrated (Table 4). The main categories were further synthesized in preparation for selective coding. Three core categories emerged: macro-factors, meso-factors, and micro-factors, which together provided a comprehensive explanation of the determinants influencing willingness to recycle WCO in Shantou City (Table 5). In the table, “C” denotes the main categories (e.g., C1, C2, C3), which represent the core theoretical concepts. These were derived through further abstraction and integration based on open coding (A codes) and axial coding (B codes).

Table 4. Illustrative quotes supporting core categories.

|

Category |

Subcode |

Illustrative Quote |

Respondent ID |

|---|---|---|---|

|

B1: Policy Impact Factors |

A1: Rural Revitalisation |

“The policy to revitalize rural areas has not reached us yet; we are still waiting for concrete action.” |

Respondent 3 |

|

B2: Government Control Factors |

A2: Prohibition of Pig Feeding |

“We were told not to feed pigs with food waste anymore, but no one really enforces this rule in our area.” |

Respondent 7 |

|

A3: Cooperation with Shopping Centres |

“We’ve cooperated with shopping centres in the past, but they don’t provide much in terms of actual support.” |

Respondent 10 |

|

|

B3: Government Advocacy Factor |

A7: Little Publicity |

“I have never heard of any government initiative on waste cooking oil recycling; there is just no publicity.” |

Respondent 5 |

|

B4: Government Incentives |

A9: Compensation |

“If the government provided compensation for recycling, I’d be more likely to participate. But there is no such system here.” |

Respondent 2 |

|

A13: Providing Equipment Easier to Handle |

“It would be much easier if they just provided us with the right equipment. But we have to buy everything ourselves.” |

Respondent 8 |

|

|

B5: Economic Factors |

A14: Small Places |

“My restaurant is so small that we just don’t have the space to store separate oil containers.” |

Respondent 12 |

|

B6: Demographic Factors |

A16: Mostly Residential Population, No Foreigners |

“Our area has mostly locals, so there is little awareness of recycling, especially among older generations.” |

Respondent 4 |

|

B7: Technical Factors |

A18: Cannot Pump the Oil |

“We do not have the equipment to pump the oil out. It is too much trouble.” |

Respondent 9 |

|

B15: Social Responsibility Factor |

A65: Distrust |

“I am not sure where the oil goes once it leaves my restaurant, so I am reluctant to cooperate with anyone.” |

Respondent 6 |

|

A66: Black-centred Oil (Gutter Oil) |

“We have heard that the waste oil sometimes gets reused in black markets. I am afraid that is happening to ours as well.” |

Respondent 15 |

|

|

A69: Psychological Burden |

“I feel guilty about not recycling properly, but it seems like too much of a hassle.” |

Respondent 13 |

Table 5. Axial coding process.

|

Main Category |

Area |

Account for |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

C1 |

External environmental factors |

B1 Policy influences B2 Government controls B3 Government propaganda B4 Government incentives B5 Economic environment B6 Demographic environment B7 Technological environment B8 External influences |

Policy influencing factors include government control, promotional and incentive measures, as well as changes in the economic, demographic, technological, and external environments. |

|

C2 |

Industry factors |

B9 Third-party economic factors B10 Third-party organizational factors |

Third parties are mainly third-party (other than governments and individuals) specialized recycling companies |

|

C3 |

Individual Factors |

B11 Restaurant handling financial factors B12 Restaurant premises factors B13 Restaurant management factors B14 Educational and cultural factors B15 Social responsibility factors B16 Channel understanding factors |

It refers to a combination of personal factors (level of education, knowledge of waste grease) and environmental factors (the environment of the restaurant) |

Selective coding is an advanced stage of qualitative data analysis that aims to identify and emphasize the core categories that structure the interpretive framework. At this stage, comparisons between data, concepts, and categories become more focused and refined. In this research, we ensured that the core concepts and categories accurately reflected the overall data content and the central issues under investigation.

During the systematic parsing process conducted through a grounded theory model, we observed the following key findings:

In the external environmental factors, urban and rural environmental protection disparities exist in policies, rights, investment, and public awareness [90]. Third-tier cities face significant challenges due to an aging population, underdeveloped economies, lagging technology, and uneven educational resources, all of which hinder environmental progress. These economic constraints limit the adoption of efficient oil and grease filtration technologies, while a large elderly population and low foreign participation reduce acceptance of new practices. Moreover, the slow pace of technological advancement and the lack of educational resources complicate environmental initiatives. Nonetheless, the study showed that residents in third-tier cities respond positively to government incentives, suggesting that measures like financial subsidies and recycling incentives could boost participation in WCO and grease recycling. This could expand recycling efforts and provide valuable raw materials for green energy production, such as biodiesel.

In the industrial factor, waste grease management in third-tier cities is challenged by the diversity and lack of standardization among third-party service providers. Service frequency varies daily to every other day, and charging models differ: some providers use prepayment methods, while others purchase waste grease. This situation reflects the nascent stage of market mechanisms in the sector. Feedback from the catering industry indicates widespread non standardized practices, including the absence of formal contracts and inconsistent service quality, underscoring the urgent need for industry standardization.

An in-depth analysis of individual factors indicates that cost-effectiveness considerations significantly influence waste oil treatment decisions. High treatment costs often lead some operators to improperly discharge waste. The challenge of source management is further compounded by the limited space available in small catering businesses, which hampers the installation of necessary filtration equipment. Despite these obstacles, the catering industry generally exhibits a degree of social responsibility and environmental awareness. Concerns about third-party treatment reflect their recognition of the “gutter oil” problem [51]. Furthermore, their commitment to maintaining hygiene and ensuring food safety demonstrates an understanding of the importance of environmental protection.

In the micro-practice context of community management, while environmental regulations cover aspects like hygiene, waste separation, and food safety, the levels of other aspects, such as publicity and education on WCO and grease recycling, remain insufficient. As a result, many practitioners lack adequate knowledge of recycling practices. Limited channels for disseminating environmental information also reduce the motivation of households and businesses to install recycling facilities, thereby hindering the effective collection of WCO and grease.

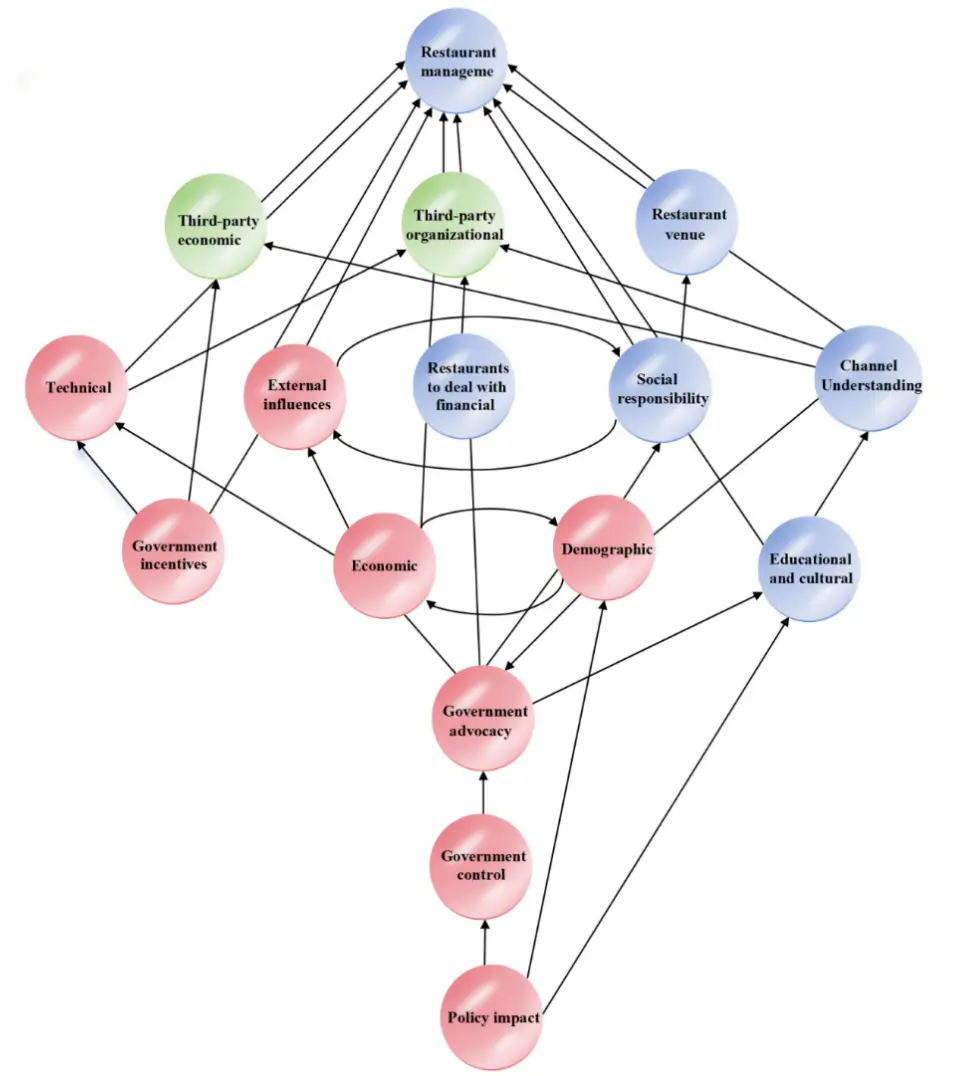

4.2. ISM Explanatory Structural Modeling Results

Interpretive Structural Modeling (ISM) is a method for analyzing and understanding the relationships and hierarchies among factors within a complex system. In this study, ISM was employed to identify the key drivers influencing restaurant operators’ willingness to participate in Waste Cooking Oil (WCO) recycling. The process involves identifying the relevant factors, constructing a reachability matrix to determine direct and indirect relationships, and deriving a hierarchical structure to uncover the most significant drivers. This model helps interpret the relative importance and interdependencies of the factors, providing insights into the critical points for policy development and practical applications. By focusing on the key steps and outcomes, we aim to present a clear and concise understanding of the ISM process while maintaining methodological rigor.

Creating a hierarchy diagram: After identifying the hierarchy of elements, the first-level elements are positioned at the lowest tier, with second-level elements directly above them, and so on, until all elements are arranged in their appropriate hierarchical levels. This process culminates in a graphic that depicts the prioritization of the results. The visual architecture illustrates the hierarchical and dependency relationships among the elements, enhancing our understanding of the overall organizational structure of the system. By visually representing these priorities, this approach clarifies the flow of influence and interactions between elements, providing a comprehensive view of the system’s operational framework.

In Figure 4, we present the key factors influencing waste cooking oil (WCO) recovery, categorized into external environmental factors, industry factors, and individual factors. This framework provides a clear and structured overview of these influencing factors. Figure 5, on the other hand, uses a network diagram to illustrate the relationships among these factors further, showing how they interact and collectively influence the WCO recovery system. For instance, restaurant management is closely linked to third-party organizational factors, financial management, and social responsibility, while government incentives and policy impacts affect recovery behaviors through various pathways. This dynamic network diagram not only helps us understand how these factors interact in practice but also emphasizes the interdependence between policy and industry factors. The transition from the categorized framework in Figure 4 to the relationship network in Figure 5 allows for a more comprehensive understanding of the multidimensional factors influencing WCO recovery and their interplay, highlighting the complexity and synergies within the WCO recovery system.

The factors outlined below were extracted from the interview data using grounded theory. Grounded theory emphasizes the inductive identification of core categories and themes directly from the data, rather than from pre-existing hypotheses. In this study, through in-depth interviews with restaurant operators, multiple hierarchical factors influencing the recycling of waste cooking oil (WCO) were identified. The seven hierarchical layers presented here reflect the diverse influences at play, covering policy, social, economic, and technological dimensions. The present research systematically analyzed factors using the ISM model and identified seven hierarchical layers influencing WCO recovery. The first tier comprised the most direct and immediate factors, while the seventh layer included more superficial influences. The intermediate layers were classified as indirect factors, each contributing to the overall recycling system. In Figure 5, red represents macro-level factors, green denotes meso-level factors, and blue indicates micro-level factors, reflecting the different layers of influence on restaurant operators' behaviors and decisions.

Micro-level Factors: At the foundation, policy factors emerged as the most fundamental influence on waste grease recycling, significantly impacting government control, individual behavior, and third-party involvement. Since much of WCO recycling in China is driven by government policies, these factors were seen as the most profound drivers of recycling behavior.

Meso-level factors could be divided into five levels: government, individual, and third-party influencing factors. The second level was the government control factor, which covers the government’s regulatory measures on WCO recycling. The third level was government publicity factors, which refer to the government’s publicity and guidance on recycling behavior. The fourth layer included government incentive factors, economic environment factors, demographic environment factors, and education and culture factors, which cover the influence of government policies, economic environment, and social culture on recycling behavior. The fifth layer included the technical link factors, external environment factors, restaurant treatment funding factors, social responsibility factors, and channel understanding factors, which refer to the technical, environmental, economic, social, and information aspects related to WCO recycling. The last layer consisted of the third-party organization factor, third-party economic factor, and restaurant premises factor, which deal with the influence of third-party organizations and restaurant premises on recycling behavior.

Macro-level Factor: The restaurant management factor was at the apex of the hierarchy and directly affected waste grease recycling practices among operators. This encompassed internal management systems, staff attitudes and knowledge regarding environmental protection, a corporate culture that promotes recycling, and the availability of necessary facilities and training. Effective management was critical for implementing successful recycling processes at the operational level.

5. Discussion

5.1. Revisiting the Hypotheses: Theoretical and Empirical Integration

To bridge the gap between grounded empirical findings and theoretical generalization, this study proposed three hypotheses derived from grounded theory coding and ISM structural modeling. These hypotheses served not merely as theoretical constructs but as explanatory anchors linking institutional, individual, and behavioral dimensions. In this section, we critically assess each hypothesis against the empirical data to evaluate its explanatory robustness.

Hypothesis 1 (H1). Government financial incentives are closely associated with restaurant operators’ willingness to participate in WCO recycling.

The findings provide strong qualitative support for H1. Government subsidies and material assistance (e.g., provision of storage equipment) repeatedly emerged in interviews as important factors shaping behavioral change. Notably, the ISM model positioned this variable at the foundational layer, suggesting its potential catalytic role in initiating voluntary compliance. Respondent A15’s statement—“If the government provides equipment and subsidies, I am willing to do it”—illustrates a recurring theme across cases. Financial incentives not only reduce the perceived economic burden but also signal institutional endorsement, which appears particularly significant in low-trust regulatory environments.

Hypothesis 2 (H2). Higher educational attainment may be associated with more standardized WCO recycling practices.

The results suggest that higher levels of education enhance awareness and the capacity to interpret environmental regulations; however, the behavioral translation of this awareness is often moderated by structural constraints. Several well-educated respondents expressed positive attitudes but were hindered by spatial limitations, lack of training, and unclear operational guidelines. Thus, education appears to function as a necessary but not sufficient condition for sustained behavioral commitment. This finding is consistent with behavioral theory, which emphasizes that knowledge must be embedded within an enabling context to translate into consistent action.

Hypothesis 3 (H3). Greater trust in third-party recycling organizations may contribute to higher levels of engagement in WCO recycling.

Contrary to expectations, H3 received only limited qualitative support. Trust in third-party recyclers was weakened by recurring service inconsistencies, opaque pricing schemes, and the lack of legal enforceability in contracts. The ISM model placed this factor in the mid-lower tier of influence, indicating that it may play a secondary role relative to governmental intervention or internal motivation. Although trust-building remains crucial in the long term, its current influence in third-tier cities appears to be constrained by systemic fragmentation and weak institutional accountability.

In sum, the evaluation of these hypotheses reveals a multi-level dynamic: structural conditions (such as policy incentives) exert a dominant influence, while individual-level variables (e.g., education) and intermediary actors (third-party firms) function within and are constrained by broader systemic contexts. These findings underscore the need for integrated policy frameworks that address behavioral, informational, and institutional deficits simultaneously.

Drawing on the grounded theory model and ISM, this study reveals that Shantou, Guangdong Province, faces multiple challenges in managing WCO and used oil. These challenges stem primarily from structural factors such as an aging population, underdeveloped economic conditions, outdated technological infrastructure, and the uneven distribution of educational resources. Prior research indicates that older adults, due to age-related changes and reduced social connectivity, are more likely to be excluded from educational opportunities and digital services [91]. A lack of relevant knowledge has also been shown to hinder individuals’ willingness to engage in pro-environmental behaviors [92]. Consistent with the present findings, Vicente et al. (2021) reported that individuals with a university education are more willing to pay for environmental quality and are more likely to participate in environmental activism [93]. Additionally, Majumdar and Sinha (2018) observed that small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) globally tend to lag behind large enterprises in the adoption of green practices [94]. In the context of Shantou, financial constraints limit the introduction and widespread use of efficient oil-water separation technologies. Many small and medium-sized food establishments struggle to upgrade their equipment due to high costs. This issue is further exacerbated by low participation rates among migrant populations and limited digital literacy among local residents, both of which impede the adoption of new technologies in WCO treatment processes. These interrelated barriers have contributed to a cognitive gap and behavioral disconnect in the implementation of environmental policies at the local level. From an institutional perspective, Shantou’s third-party service providers are relatively homogeneous, with unstandardized operational procedures and significant inconsistencies in service frequency and quality. This aligns with the findings of Sun et al. (2021), who highlighted the fragmented nature of waste management markets in smaller cities. Furthermore, due to spatial limitations, many small-scale food businesses are unable to install standardized grease separation units, intensifying challenges in source-level control. These findings further support the arguments of Baldi et al. (2022), who emphasize that technological acceptance is critical in the development of citizen-centered smart cities. However, in smaller cities characterized by aging populations, weak infrastructure, and pronounced digital divides, promoting the adoption of technology presents even greater challenges [95].

5.2. Public Attention Insights Revealed by the LDA Model

The introduction of the Latent Dirichlet Allocation [20] model in this study serves as a critical complement to the grounded theory approach, addressing several inherent limitations of qualitative data analysis. While grounded theory effectively uncovers macro-level socio-economic issues, such as an aging population, underdeveloped technological infrastructure, and insufficient public awareness regarding WCO management, it falls short of tracking dynamic shifts in public sentiment, discourse trends, and policy impact over time. In contrast, the LDA model enables a comprehensive, data-driven analysis of large-scale textual data from social media platforms, capturing subtle patterns in public attention and emotional responses to specific issues, such as “gutter oil” and its recycling. By extracting and categorizing thematic trends from vast datasets, the LDA model provides empirical insights into the complexities of WCO recycling that grounded theory alone may not reveal. Furthermore, the LDA’s ability to quantify the salience of particular topics over time enhances the precision of policy recommendations and strategic interventions, facilitating more targeted approaches to environmental sustainability. Thus, by integrating the inductive insights of grounded theory with the quantitative robustness of LDA, this study achieves a more nuanced, multidimensional analysis that bridges the gap between macro-level trends and micro-level behavioral patterns, thereby enriching the overall understanding of WCO management challenges in Shantou City.

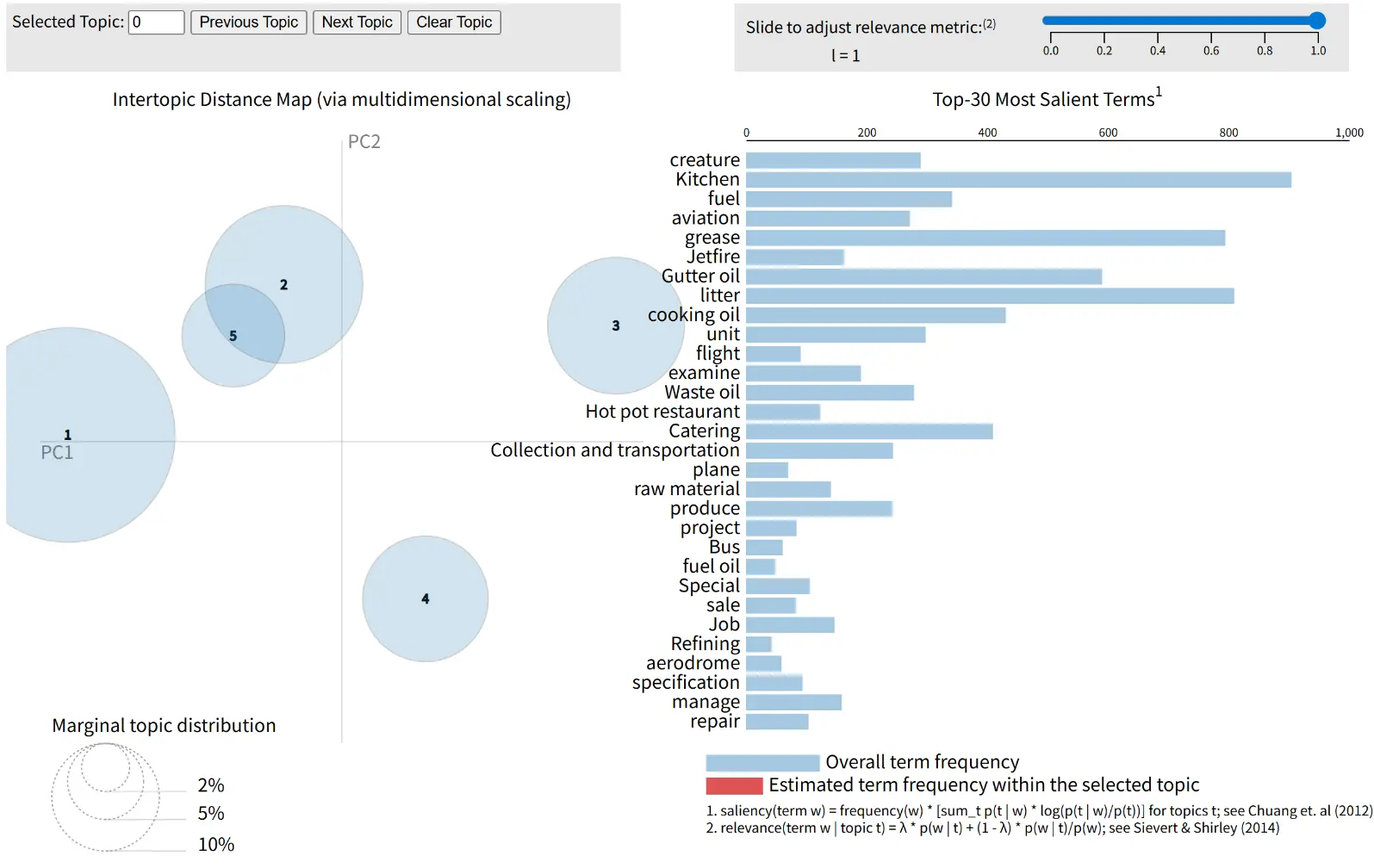

A significant challenge in addressing the recycling of WCO and grease is public concern that gutter oil may re-enter the food supply as legitimate WCO. Driven by economic interests, some illegal enterprises have established cross-provincial supply chains to process and sell gutter oil as WCO [96]. This practice has placed Chinese biodiesel producers at a competitive disadvantage when sourcing feedstock, thereby jeopardizing their viability. Using state-of-the-art Latent Dirichlet Allocation [20] methodology, we analyzed the thematic modeling of Chinese WCO-related texts sourced from Weibo. By systematically crawling the data and focusing on core terms such as “kitchen waste oil and grease”, “catering waste oil”, and “waste oil”, we ensured that the selected samples were highly relevant and representative. The data spanned the period from 2015 to 2024, yielding 4000 high-quality text records. Before applying the LDA model, we conducted essential preprocessing steps, including removing stop words, punctuation, and numbers, and stemming, to enhance the model’s accuracy. We then determined the optimal number of topics through cross-validation and used the LDA model to infer topic distributions across the text collection (Figure 6).

When the number of topics was set to five, the model achieved its highest topic consistency, and the visualization results from pyLDAvis indicated the best classification between topics at this point. Therefore, five topics were selected as the optimal number. Themes related to WCO recycling were extracted using the LDA model, and the five identified themes were manually condensed into a theme-phrase probability distribution table (Table 6). The keywords from these themes are closely related to food waste management, WCO source pathways, resource utilization, WCO production, and third-party treatment.

Table 6. Probability distribution of word items.

|

Serial No. |

Thematic |

Keyword Phrases (Top 10 Keywords in Terms of Weight) |

|---|---|---|

|

1 |

Food waste management |

kitchen, waste, grease, unit, catering, collection, inspection, waste, management, work |

|

2 |

Waste oil source pathways |

Gutter oil, grease, kitchen, hotpot restaurant, cooking oil, production, sales, bus, processing, food |

|

3 |

capitalize on resources |

Bio, fuel, aviation, jet fuel, waste oil, gutter oil, catering, flights, feedstock, production |

|

4 |

Waste oil production |

Cooking oil, waste, fuel, aviation, gutter oil, production, generation, enterprise, airport, waste oil |

|

5 |

Third-party processing |

kitchen, grease, gutter oil, project, waste, utilization, enterprise, pilot, resourcing, work |

According to the analysis of the collected data, the issue of WCO and fats gained significant attention in 2022, with WCO and fats from kitchen sources becoming the core focus of public attention. In particular, the “gutter oil” discussion remains strong, suggesting that the public has significant, general misgivings about it.

China’s current policies on WCO recycling and its conversion into biodiesel primarily focus on regulation, planning, and target setting. Most studies suggest that enhancing enforcement, education, infrastructure optimization, and financial incentives are crucial for raising restaurant operators’ awareness of proper waste management [27,34,99,100]. The strategies proposed in this study are in line with prior research on the determinants of WCO recycling behavior in China. Notably, Yang and Shan (2021) emphasize that enhancing government regulation and subsidy mechanisms for restaurants, increasing demand and purchase prices offered by biofuel companies, and promoting consumer social responsibility can significantly improve restaurants’ compliance with legal WCO disposal [101]. Similarly, Liu et al. (2019) identify restaurants as the most effective leverage point in the WCO supply chain. They demonstrate that financial incentives—such as a subsidy of ¥4000 per ton—can increase recoverable WCO volumes by up to 47%, outperforming incentives targeting collectors or producers. Moreover, a combined policy approach that integrates regulatory enforcement with economic incentives proves more effective than standalone measures, particularly when restaurant price sensitivity exceeds a threshold of 17.98 [35]. These studies commonly highlight that integrating public education, digital management tools, and multi-stakeholder collaboration into policy design can enhance the efficiency of resource recovery and public participation—an approach particularly critical in the context of third-tier cities. Given the specific challenges faced by third-tier cities regarding WCO management, this research proposes three integrated strategies that combine technological, policy, and market-driven solutions to promote sustainable recycling and utilization of WCO.

5.3. Comparison and Implications of Waste Grease Recycling Governance Models in First-, Second-, and Third-Tier Cities

Community management links the macro, meso, and micro levels. Community management helps coordinate policy and resource allocation at the macro level [102], ensuring that environmental policies are effectively implemented at the meso-level. By regulating the behavior of third-party service providers [103], it can improve service quality and promote the healthy development of the industry. At the micro level, community management can directly interact with caterers to enhance their environmental awareness and encourage participation in the proper disposal of WCO and grease [104]. In this manner, community management becomes an essential link between the macro, meso, and micro levels and helps solve various waste grease management problems.

Given the significant influence of community management on restaurant waste grease recycling behavior [105], an in-depth exploration of the operational mechanisms of the waste grease recycling system is essential for achieving centralized management. This approach can help address the challenges of decentralized recycling in restaurants, reduce illegal supply chains, enhance biodiesel availability, and ultimately promote environmental sustainability. To achieve this, an in-depth interview methodology was employed, involving interviews with 20 restaurant operators in Shantou City and examining the city’s community waste segregation management department. These interviews provided valuable insights into the functioning of the WCO and grease recycling system from various perspectives, offering empirical evidence for constructing a more effective management framework.

In Shantou City, community management has identified that waste separation publicity remains in its early stages. The community has adopted a multi-dimensional strategy that cultivates awareness early, influences families through school education, tailors communication for various age and social groups, and establishes agreements with catering operators to strengthen compliance. However, challenges persist, including low resident awareness, inadequate resource allocation, and uneven capabilities among third-party recycling organizations [106]. The lack of government subsidies and unified planning exacerbates these issues. Additionally, a scarcity of third-party WCO and grease recycling organizations, along with high technological thresholds and poor market integration, undermines the recycling system [36]. Although a market-based sanitation system has been implemented, other issues remain, including inconsistent fees charged by third-party agencies and supervisory difficulties. Insufficient funding and fluctuating grease production from restaurant waste further complicate recycling efforts [107]. Experts recommend that the government enhance investment, provide financial and infrastructural support, optimize resource allocation, and promote technological innovation to establish a more efficient waste separation and grease recycling system [36]. Continuous monitoring of publicity effectiveness and flexible strategy adjustments are essential for narrowing the gap with first-tier cities and achieving comprehensive waste separation and effective resource utilization of WCO.

Among Chinese cities, only three first-tier cities—Beijing, Shenzhen, and Dongguan—have achieved an average sustainability performance score above 0.5. Shenzhen demonstrates the strongest performance, with all dimensions—comprehensive, economic, social, and environmental sustainability—scoring above 0.5. Dongguan also performs relatively well, with its overall, social, and environmental sustainability indicators exceeding the 0.5 threshold [108]. In this context, Shenzhen and Dongguan, located in the same province as Shantou City, were selected for field research. Their success stories offer valuable insights for Shantou in terms of promoting waste separation and resource utilization of WCO. Shenzhen has implemented a stringent management system, including a restaurant registration process, QR code tracking, regular monitoring, and the installation of grease segregation devices, along with free recycling services and an open bidding process for third-party treatment companies. These initiatives illustrate the potential for transitioning from disorderly to orderly management [109]. Shenzhen has also increased the collection of recyclables through a comprehensive strategy that combines enforcement, education, and incentives to raise public awareness and promote environmental sustainability [110]. The findings of the present study indicate that infrastructure development, government publicity, and incentives positively influence residents’ willingness and actual behavior in waste separation. By contrast, residents’ attitudes and perceptions of behavioral control significantly impact waste separation practices [111]. Meanwhile, Dongguan has focused on enhancing education and publicity in the early stages of its waste classification system and has achieved notable results.